1. Introduction

The shift in recent years from monolithic to microservice architectures has deeply affected software development and deployment, leading to many benefits in scalability, maintainability, and fault tolerance. As more organizations adopt cloud-native approaches, establishing real-time monitoring and anomaly detection to maintain system reliability is becoming critical. Traditional anomaly detection methods mainly depend on manually set thresholds or predefined rules, which fail to scale with the dynamic nature of microservices. Moreover, as microservices grow increasingly complex, detecting anomalies across different services and system components presents new challenges.

To address these issues, AI-driven monitoring has been implemented, relying on machine learning and deep learning models to automatically detect deviations from normal behavior. This paradigm shift has paved the way for innovative methods that enhance the robustness and sustainability of microservices architectures. However, despite the growing body of research, the integration of AI into microservice architectures for anomaly detection remains in its early stages, with gaps in handling temporal coherence and processing multi-source data.

While the existing literature extensively discusses the benefits of transitioning to microservice architectures, especially in terms of scalability and development efficiency, there is limited research on how AI techniques can be effectively integrated into these architectures for anomaly detection. Specifically, most studies focus on single-source data, such as logs or system metrics, overlooking the potential of combining diverse data sources for more accurate anomaly detection. Additionally, the temporal structure of the data, crucial for time-series anomaly detection, is often inadequately addressed, leading to reduced accuracy in identifying system faults in complex environments. This study seeks to fill these gaps by proposing and evaluating the Night’s Watch algorithm, which integrates temporal features and multi-source data to enhance anomaly detection in microservices.

The purpose of this research is to design and evaluate the performance of the Night’s Watch algorithm, a novel approach to AI-driven anomaly detection in microservice architectures. The study will focus on the following objectives:

To evaluate the impact of training set size on the algorithm’s precision and recall in detecting anomalies.

To explore how disruptions in temporal coherence affect the performance of time-series anomaly detection models.

To investigate the efficacy of combining multiple data sources, such as system logs, performance metrics, and alarms—in improving the algorithm’s ability to detect anomalies.

The significance of this study lies in its potential to improve real-time monitoring in cloud-based microservices environments. By integrating AI-driven techniques with temporal modeling and multi-source data, this research aims to provide a more comprehensive and scalable solution for anomaly detection. The findings could have broad implications for both academic and industrial sectors, particularly in enhancing the sustainability of microservices by reducing false alarms and optimizing system uptime. Additionally, this research contributes to the growing discourse on the intersection of AI and modern software architectures, offering new insights into how these technologies can collaborate to improve operational efficiency.

Related Works

Although the algorithmic foundations of anomaly detection have been widely studied, the operational landscape in which these models are deployed has undergone a significant transformation with the rise of DevOps-driven engineering practices. Modern microservice platforms rely heavily on continuous integration, automated deployment pipelines, infrastructure-as-code, and centralized observability stacks to ensure that services remain stable while evolving rapidly [

1,

2]. These workflows introduce new requirements for data collection, model retraining, versioning, and rollout strategies that are fundamentally different from traditional monolithic environments [

3]. As a result, the deployment of learning-based monitoring systems increasingly depends on how effectively these DevOps practices can support automated telemetry ingestion, reproducible feature pipelines, seamless model updates, and safe rollback mechanisms [

4]. Integrating such capabilities has become a prerequisite for sustaining reliability and operational agility in large-scale microservice ecosystems.

The transition from monolithic systems to microservices has been well documented, with prior studies demonstrating improvements in scalability, flexibility, and fault isolation enabled by decentralized architectures [

5]. As systems become more distributed and dynamic, maintaining reliability increasingly depends on automated monitoring mechanisms supported by advanced analytical and intelligent decision-support techniques [

6]. Machine-learning approaches have been applied across various operational domains relevant to microservices, including early-warning systems [

7], predictive maintenance pipelines [

8], and reinforcement-learning-based resource optimization [

9]. Yet, as noted by [

10], many of these implementations remain tied to traditional or semi-distributed settings, leaving open methodological and operational questions regarding how AI models can be deployed, orchestrated, and continuously updated in fully decentralized microservice ecosystems.

A core challenge highlighted in the literature concerns data movement and model lifecycle management in distributed environments. Microservices generate large volumes of heterogeneous telemetry that demand robust, real-time data pipelines [

11,

12], while their decentralized structure complicates versioning, dependency management, and runtime consistency for AI models [

13,

14]. Best practices therefore emphasize DevOps automation [

15], containerization and orchestration technologies [

16], and centralized logging and monitoring infrastructures [

17] to enable reliable integration of AI-driven monitoring.

Building on this foundation, a growing line of research positions variational autoencoder (VAE)-based architectures as a strong methodological basis for unsupervised anomaly detection in microservice ecosystems. Li et al. (2025) [

18] demonstrate that VAEs can learn compact latent representations of distributed traces, enabling the detection of subtle deviations in multi-service execution flows. Hierarchical and dual-autoencoder extensions further capture temporal, structural, and multi-level dependencies in service interactions [

19,

20]. VAE-based models have additionally proven effective for modeling seasonal fluctuations, nonlinear patterns, and complex temporal dynamics in service-level KPIs [

20]. These findings are reinforced by broader deep learning research showing that neural architectures can extract hierarchical and discriminative representations from high-dimensional operational data far more effectively than traditional statistical methods [

21,

22,

23]. Within microservices—where distributed execution paths, heterogeneous resource use, and rapidly evolving topologies create intricate behavioral patterns—representation-learning approaches trained on distributed tracing data have uncovered abnormal service interactions, latent error propagation, and structural anomalies by learning statistical regularities of end-to-end execution flows [

24,

25,

26]. Complementing these trace-centric generative approaches, metric-based anomaly detection using feedforward neural networks, such as multilayer perceptrons, has also shown competitive performance [

27].

Despite this progress, a noticeable gap remains in understanding how microservice architectures specifically support the deployment, scaling, and operational management of AI-driven monitoring systems. Existing studies provide valuable algorithms and architectural insights, yet they often abstract away the practical considerations of real-world integration. This study contributes to narrowing this gap by examining the application of AI-based anomaly detection within an operational microservices environment, offering both theoretical grounding and practical insights derived from the HangiKredi case. Through this lens, the work provides an updated perspective on how modern software architectures can more effectively leverage AI techniques to improve reliability, performance, and system uptime.

2. Materials and Methods

Night’s Watch is an algorithm designed to provide users with uninterrupted and stable service by detecting and alerting anomalous situations in real-time. In this section, we describe the dataset used in our algorithm, the methodology applied, and the steps taken to improve the method.

2.1. Dataset

The Night’s Watch algorithm utilizes data from HangiKredi servers. All metrics are collected in 15-min intervals from New Relic and consist of CPU core usage, memory usage, web throughput, .NET Web Service Objects (WSO), Postgres WSO, Redis WSO, and Web External WSO values.

The dataset encompasses data from December 2023 to April 2024. Due to software issues in the logging infrastructure, data collection was discontinued for approximately 30 days, specifically between 15 January and 15 February. The continuous period from 15 February to 15 April is deemed suitable for use. The test set has been allocated from 15 March to 15 April, and performance measurements were conducted with this test data kept constant. Experiments were performed with the remaining data. In these experiments, training and validation sets were prepared using 10-day, 20-day, and 30-day windows from 15 February to 15 March. Finally, to utilize the entire dataset, data from January to March was prepared for training and validation. Of this prepared dataset, 10% was used for validation, and the remaining portion was used for training.

The ground truth data has been generated using three different methods. Firstly, alarm data provided by HangiKredi’s DevOps team was used. These alarms were derived from errors reported by pods, the number of errors occurring within a specified time frame, and resource consumption. These alarms represent the best-case scenario. Performance results based on these alarms will indicate the strength of the Night’s Watch algorithm in comparison to the current situation. This case is referred to as the application ground truth.

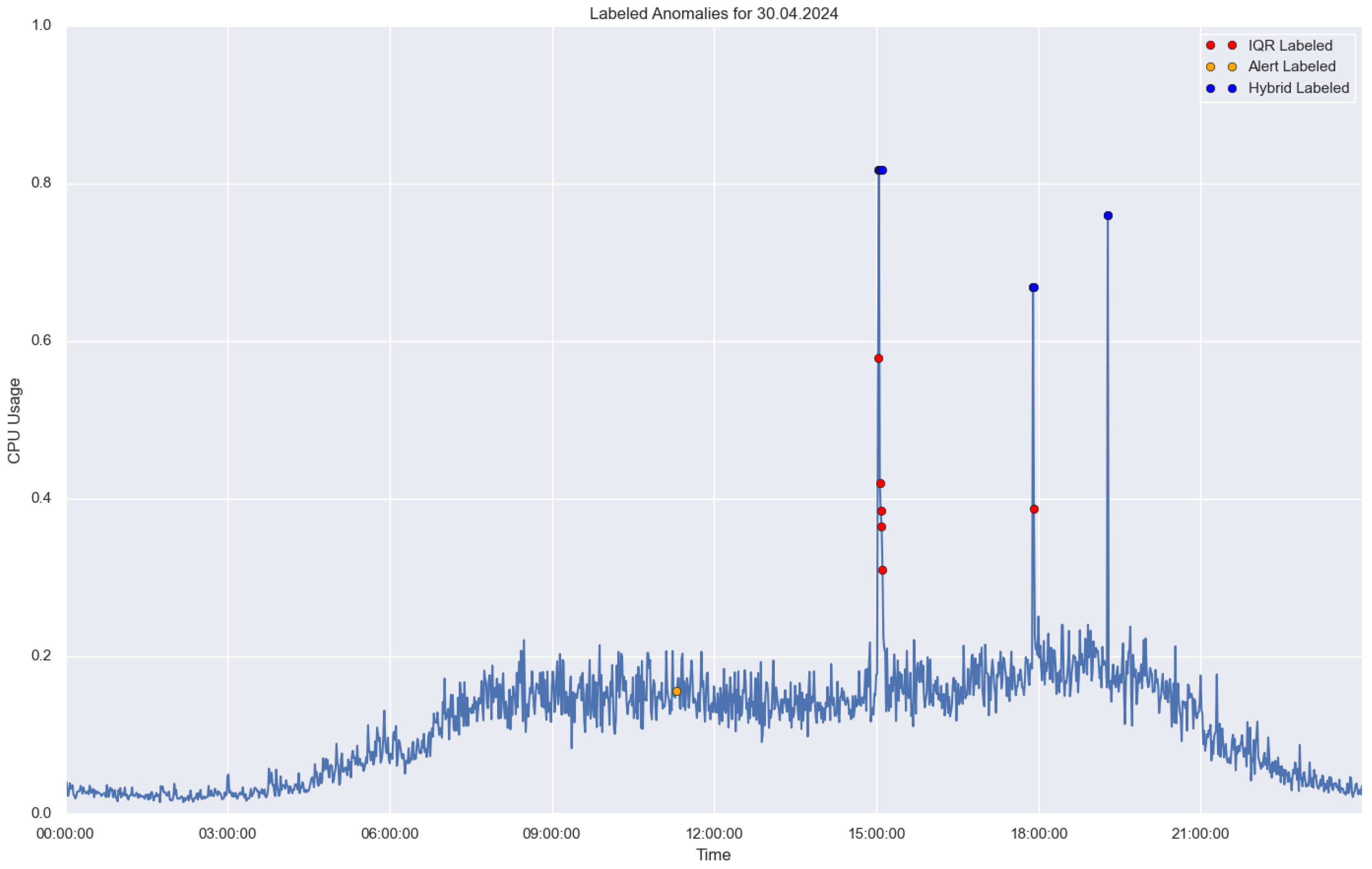

In

Figure 1, the combined ground truth is represented by the blue points. This ground truth is obtained by combining IQR-detected points with alarm data. Anomalies are considered to be true anomalies if there is an alarm within the previous 9 h of an IQR-detected point. This allows for simultaneous measurement of the algorithm’s performance against both theoretical and application-based anomalies. This is the most realistic ground truth. This case is referred to as the combined ground truth.

Table 1 provides the counts of ground-truth instances across different scenarios in the training dataset. Three continuous windows were used. To include a larger dataset (the “90-day” window, labeled as Not Fully in

Table 1), non-continuous data segments from January through March were concatenated, producing a total of 59,200 data points. No imputation methods were applied to fill the 30-day gap. This setup was designed to examine how sensitive the VAE/Time2Vec architecture is to substantial breaks in temporal continuity. In the test dataset, representing the period from 15 March to 15 April, there are 244 application ground truths, 1382 theoretical ground truths, and 519 combined ground truths. This results in a total of 44,452 data points used for testing.

After generating individual ground truths, labels for each data point marked as an anomaly within one hour following time t were created based on the status at time t, and performance measurements were conducted accordingly. Ground truth filtering was performed on the training data. In the test data, the number of labels based on application ground truth is 2219, the number of labels based on theoretical ground truth is 10,196, and the number of labels based on combined ground truth is 5169.

2.2. Anomaly Detection

Night’s Watch is an algorithm designed to detect anomalies in the microservices of the HangiKredi application. The algorithm does not aim to detect anomalies that occur far in the future but instead focuses on identifying the onset of anomalies. This approach reduces complexity and provides a more efficient and practical solution. The core of the algorithm utilizes a Variational Autoencoder (VAE) [

28] developed to encode the distribution of the data.

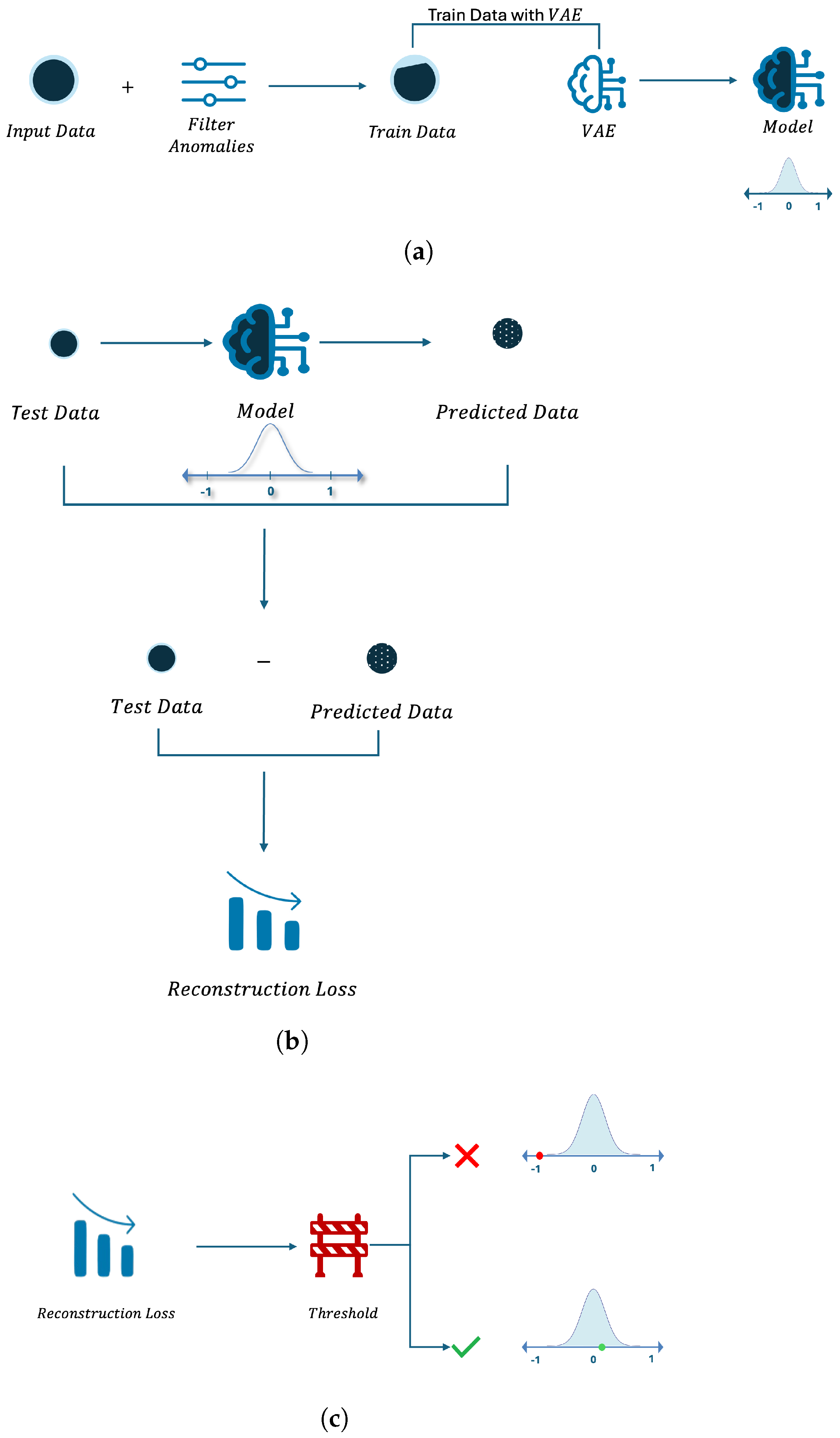

As shown in

Figure 2a and Listing 1, the VAE model is initially trained using data that contains only normal instances. The purpose of this training is to enable the model to learn the expected data distribution using only normal instances. During the anomaly detection phase, the data points are passed through the trained VAE model to obtain the reconstructed data. As illustrated in

Figure 2b, the reconstruction loss is calculated using the Mean Squared Error (MSE) between the reconstructed data and the original data. If the resulting loss exceeds a predefined threshold, the data point is classified as an anomaly, as shown in

Figure 2c.

The threshold is a crucial parameter in the final step of anomaly detection. In this study, the threshold value is determined based on training data. Specifically, the training data are reconstructed using the trained VAE model, and the reconstruction loss is calculated for each instance. The 95th percentile of these loss values is used as the threshold. Since the threshold is employed to distinguish anomalous instances, only normal instances are used during VAE training, whereas both normal and anomalous instances are considered in the threshold determination process.

Anomalies in the operation of microservices (combined ground truth) can vary over time. Traffic may be considered normal during certain hours or days but can be deemed abnormal at other times. To enhance the robustness of our algorithm against such variations, Time2Vec was utilized at the input stage. Subsequently, the encoder and decoder were constructed using Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks. Since our features are extracted on a minute-by-minute basis and to avoid increasing the complexity of the algorithm, a window size of 1 was used without incorporating historical data. This approach helps prevent potential false alarms. Although the window size of 1 implies that no explicit temporal context is provided, the inclusion of LSTM layers remains beneficial. The gating mechanisms within LSTMs introduce nonlinear transformations that enrich feature representation and stabilize training, effectively acting as gated nonlinear encoders and decoders rather than traditional sequence models. Additionally, depending on state-handling configurations, limited contextual information may still be retained across samples, providing a weak form of temporal continuity.

The algorithm (Listing 1) was developed using the Python 3.12.2 programming language and the TensorFlow framework [

29]. Development was carried out on a MacBook Pro with an Apple M3 Pro chip, equipped with 36 GB of memory and 11 cores, running macOS Sonoma 14.1.

| Listing 1. Representation of the Night’s Watch algorithm’s logic. It aims to assume if anomaly situation is starting. |

| const |

| MaxMonths = 3; |

| Threshold = 3; |

| var |

| Train : 1 . . MaxMonths Data; |

| Test : Will check data; |

| begin |

| Train := Filter anomalies from Train; |

| VAE := Create VAE Model using Train; |

| ReconstructedTest := VAE(Test); |

| Loss := MSE(Test, ReconstructedTest); |

|

| IF Loss > Threshold: |

| Warning ’Anomaly is starting’ |

| end. |

Variational Auto Encoder

The Variational Autoencoder (VAE) is fundamentally a generative model composed of encoder and decoder components [

28]. The encoder maps the input to a lower-dimensional latent space. The latent space represents the mean and variance values. The model performs encoding by learning the probability distribution based on these mean and variance values.

In a VAE network, both reconstruction loss and Kullback–Leibler (KL) Divergence are used to compute the loss. KL Divergence measures the difference between the learned distribution in the latent space and the standard distribution, thereby contributing to the learning of the data distribution. Reconstruction loss examines the difference between the input data and the decoded data, with the goal of minimizing this difference. In the Night’s Watch algorithm, Mean Squared Error (MSE) is used as the reconstruction loss. In the equation,

N represents the number of samples,

denotes the original data point, and

denotes the output of the decoder.

The Night’s Watch algorithm is based on the assumption that a VAE (Variational Autoencoder) model, trained with normal data, learns the distribution of the normal data. Consequently, the distribution of the generated data will conform to the model’s learned distribution. When abnormal data are encountered, it will exhibit characteristics different from the normal distribution, causing the generated data to significantly differ from the original. This difference can be detected by measuring the reconstruction loss, which in turn allows for anomaly detection.

The Night’s Watch algorithm relies on the assumption that the VAE model learns the data distribution. In this scenario, the distribution of the generated data is expected to align with the normal distribution. To detect anomalies, reconstruction loss is employed. According to the assumption, if the situation is normal, the reconstruction loss should be low, as the distribution of the reconstructed data will resemble that of the normal data. Conversely, for abnormal data, the distribution will differ, leading to a higher reconstruction loss. Data points with a high reconstruction loss can therefore be classified as anomalies.

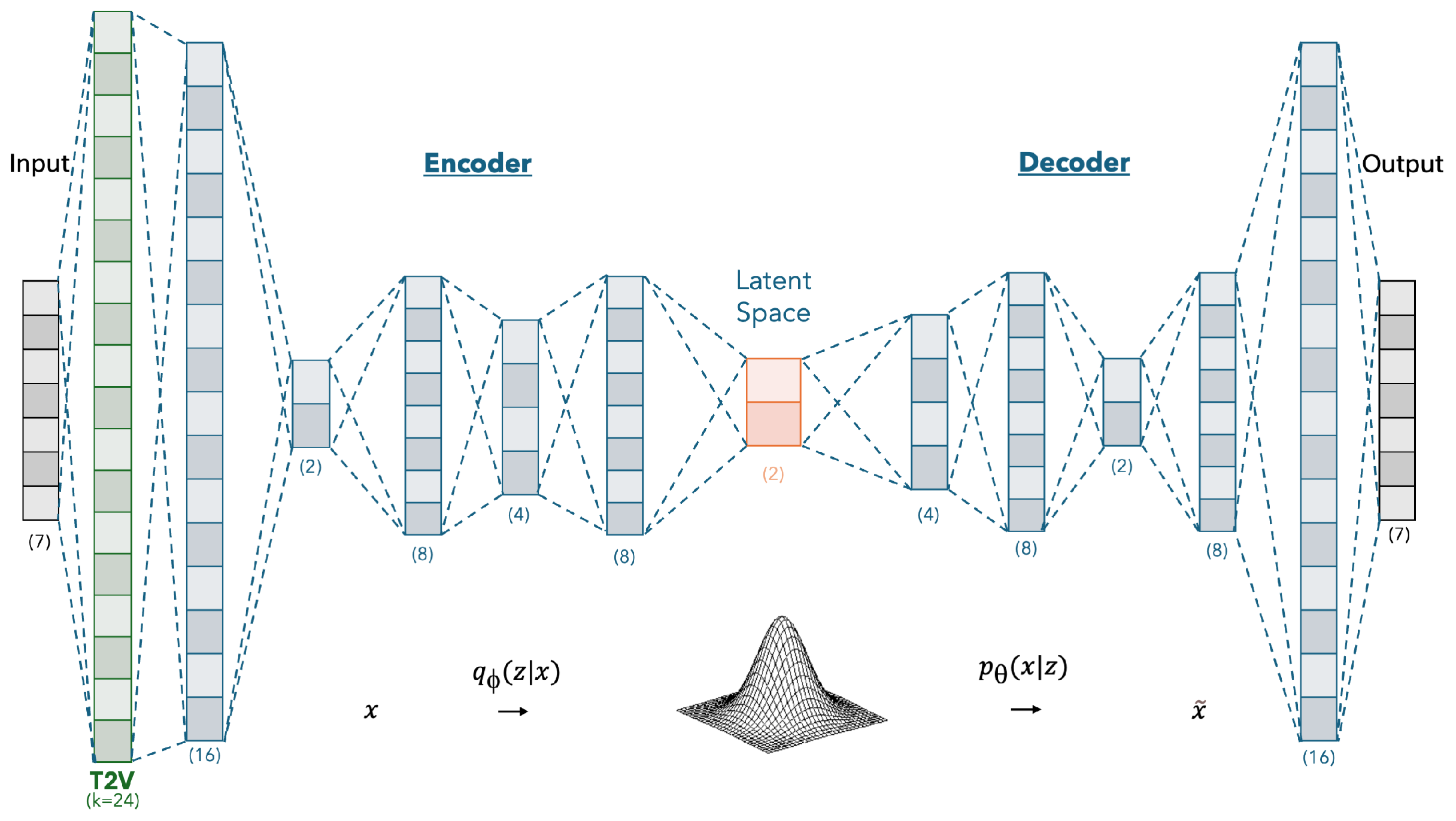

The VAE network architecture used for the Night’s Watch algorithm is illustrated in

Figure 3. The network consists of 5 encoder and 5 decoder layers. The latent dimension is set to 2, and the kernel size for the Time2Vec layer is 24. The number of units in the LSTM layers of the encoder are 16, 2, 8, 4, and 8, respectively. In the decoder, the LSTM layers contain 4, 8, 2, 8, and 16 units, respectively. A dropout rate of 0.2 is applied throughout the network to mitigate overfitting. The model is trained using a batch size of 16 and the Adam optimizer. The mean squared error (MSE) is employed as the validation loss function. The validation loss is continuously monitored, and early stopping is applied if no improvement is observed for five consecutive epochs. The model corresponding to the lowest validation loss is selected for final use.

2.3. Time2Vec Layer

The Night’s Watch algorithm was developed with the consideration that resource usage may vary throughout the day or according to periodic events. To incorporate temporal aspects, the algorithm utilizes Time2Vec [

30], which has been shown to improve performance across various datasets by generating learnable vectors.

Time2Vec is designed to be integrated into any architecture. The sine activation function, shown in the equation, is used to ensure periodicity. Here, t represents the scalar expression of time. The parameters and are learned and represent the frequency and phase-shift in the sine function, respectively. The variable k denotes the vector dimension. In the Night’s Watch algorithm, k (kernel size) is set to 24.

3. Results

The Night’s Watch algorithm operates in an unsupervised manner, relying on multiple methods to generate ground truth labels, as detailed in

Section 2.1. To evaluate the performance of the algorithm, precision and recall scores were calculated using these labels. In this context, True Positive (TP) refers to instances correctly identified as anomalies, False Negative (FN) to anomalies incorrectly identified as normal, True Negative (TN) to normal instances correctly identified as normal, and False Positive (FP) to normal instances incorrectly identified as anomalies.

Precision, defined as the ratio of

TP predictions to the total positive predictions (TP + FP), is used to optimize the algorithm’s false alarm rate. Recall, defined as the ratio of TP predictions to the actual positive instances (TP + FN), measures the algorithm’s effectiveness in detecting anomalies.

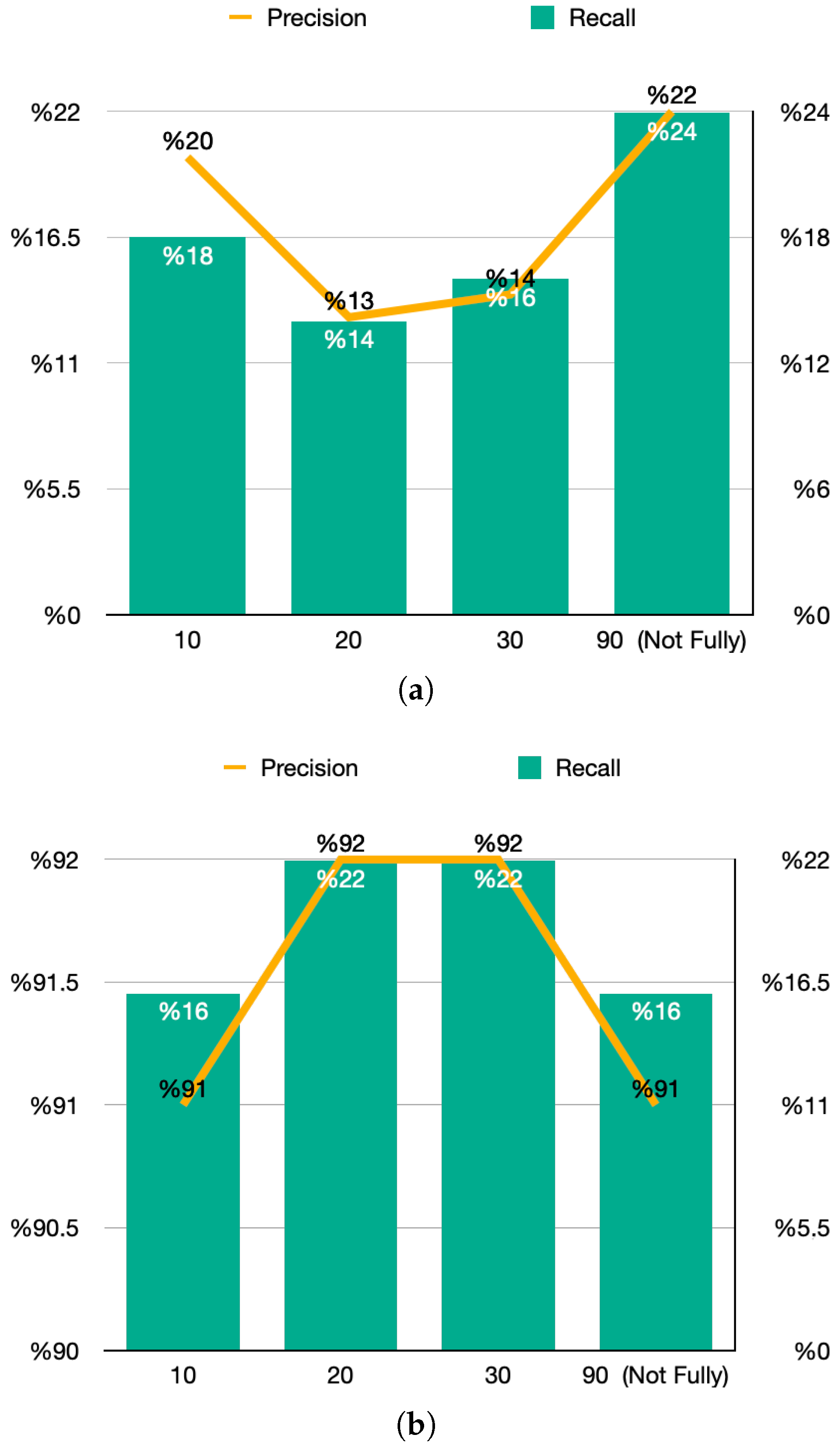

3.1. Performance with Application Ground Truth

Experiments using training sets of varying duration (10, 20, 30, and 90 days) were conducted to assess the algorithm’s performance with ground truth labels generated from actual application data. The results are presented in

Figure 4a. The highest recall value of 24% was achieved with the 90-day training set, while the corresponding precision reached 22%. Although this 90-day set contained a known 30-day gap and utilized concatenated non-continuous data, the sheer volume of additional application-labeled anomalies contributed to the improved recall in this specific scenario.

This observation aligns with findings from recent studies, such as the work by [

27], which highlights the importance of service-level data in improving anomaly detection accuracy in microservices. Their study employed a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) model and demonstrated that larger datasets can improve detection precision and recall by providing a richer temporal context.

3.2. Performance with Theoretical Ground Truth

A similar set of experiments was conducted using theoretical ground truth labels, with results depicted in

Figure 4b. Here, the best recall of 22% and a precision of 92% was observed with the 30-day and 20-day training sets, while the 10-day and 90-day sets showed slightly lower performance. This highlights how important it is for the model to learn the temporal structure in the data. The drop in performance with the 90-day set shows that the 30-day break and the way it was stitched together (as explained in

Section 3.1) disrupted the time continuity, which ended up hurting the Time2Vec and LSTM layers.

The theoretical ground truth experiment also achieved a high precision of 92% and recall of 22% with the 30-day and 20-day training sets, indicating that while recall was lower, the algorithm was highly effective at minimizing false positives. The significant drop in recall for the 90-day set, despite the tripling of time window size, suggests that data quality and continuity are just as important as quantity when training the algorithm. This result supports the idea that using non-continuous data segments—even when fully labeled—reduces the ability of Time2Vec to capture long-range periodic patterns. This aligns with findings from [

31], who emphasized the importance of maintaining temporal coherence for effective anomaly detection in large-scale systems using LSTM models.

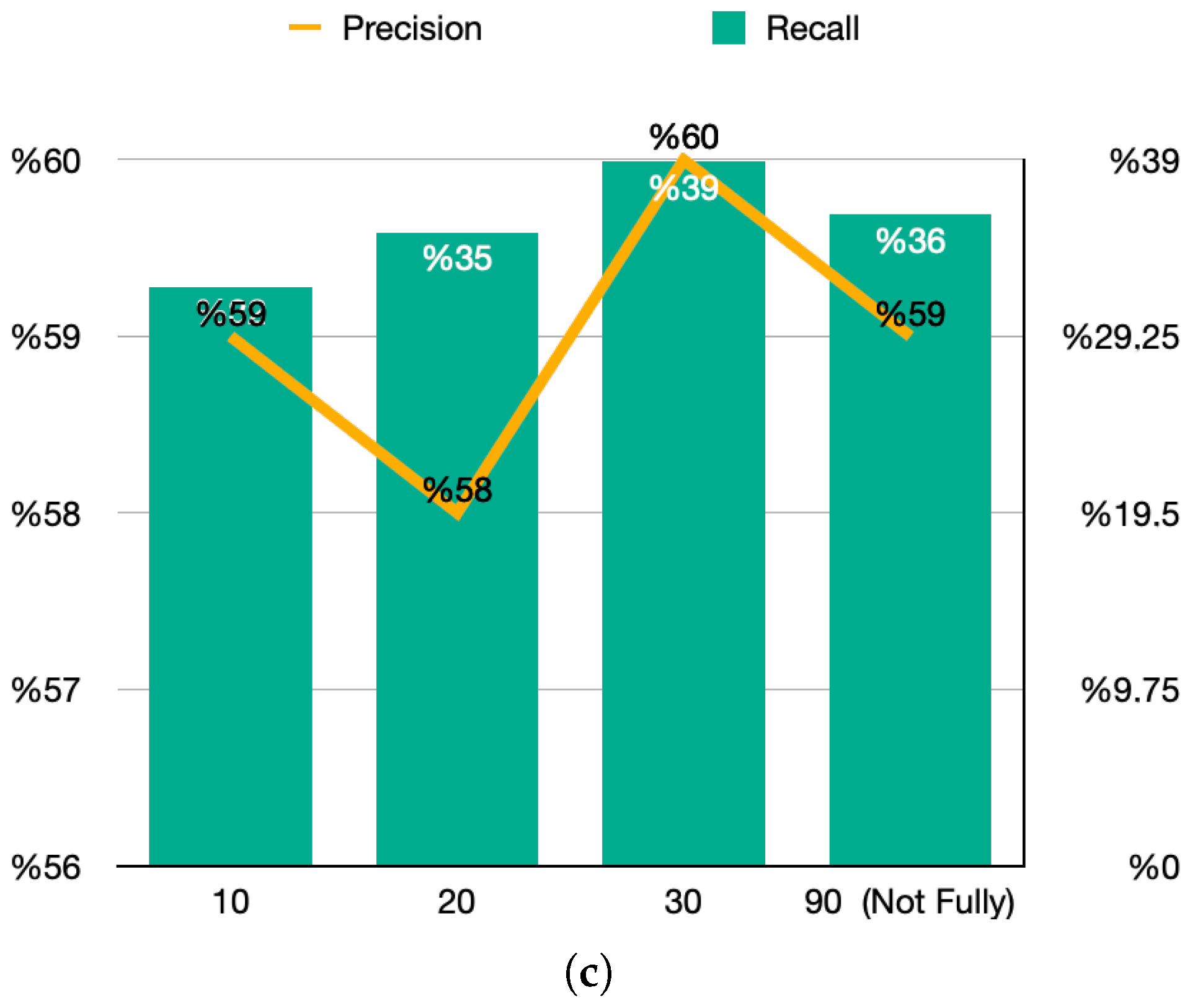

3.3. Performance with Combined Ground Truth

Finally, experiments using combined ground truth labels—considered the most realistic due to their incorporation of both peak points and alarm data—were conducted. The results, shown in

Figure 4c. indicate that the 30-day training set yielded the highest performance, with 60% precision and 39% recall. Although the 90-day set performed better than the 10-day set, it still fell short of the 30-day set. This reinforces that deliberately stitching together non-continuous data segments in the 90-day window weakened the algorithm’s ability to preserve temporal coherence.

This outcome is consistent with the research conducted in [

32], who explored anomaly detection in container-based microservices using performance monitoring data. Their findings demonstrated that while larger datasets improve overall performance, disruptions in data continuity can significantly affect the accuracy of anomaly detection models.

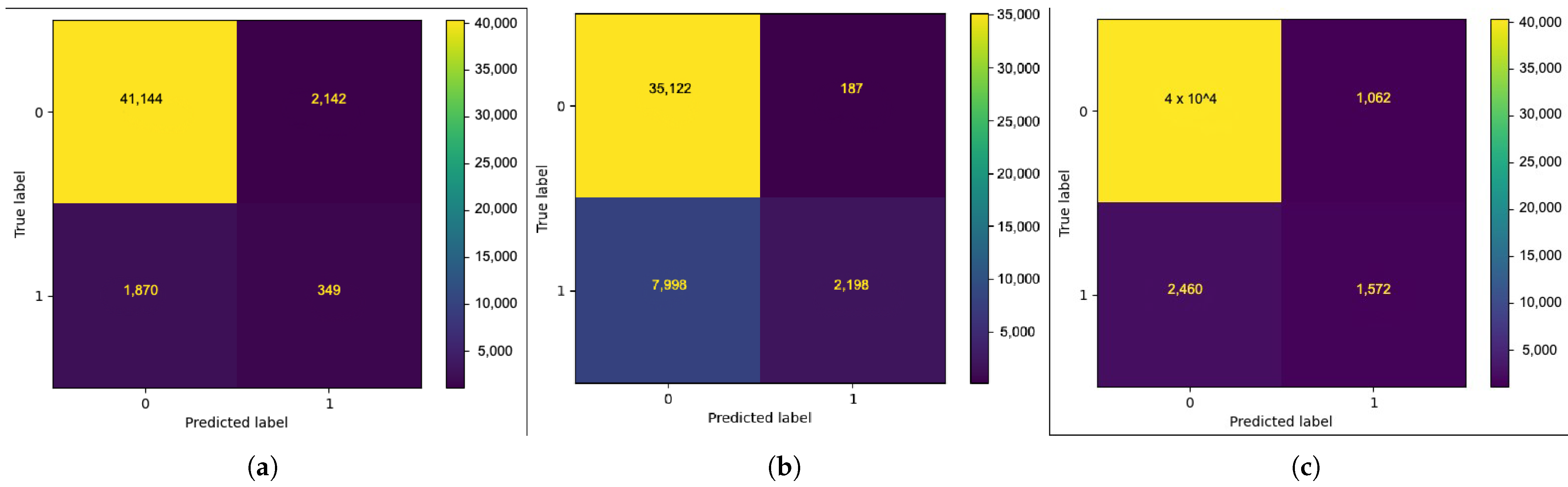

The confusion matrices for all ground truth experiments in

Figure 5 reveals that the Night’s Watch algorithm maintains robust performance across different scenarios, particularly in normal conditions, which enhances its usability in practical applications. The consistent precision across different training set sizes suggests that the algorithm is reliable in avoiding false positives, which is crucial for maintaining service sustainability during microservices monitoring [

33].

3.4. Comparative Evaluation and Analysis

We assessed the generalizability of the

Night’s Watch algorithm using three diverse time-series from the Numenta Anomaly Benchmark (NAB):

Twitter Volume Amazon,

Twitter Volume Apple, and

Speed 7578. The algorithm was benchmarked against four widely used anomaly detection methods: Prophet, K-Means clustering, One-Class SVM, and a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN)—

Table 2.

On both Twitter datasets, Night’s Watch achieved the highest F1 scores (≈0.20 versus ≤0.06 for all others), reflecting a more pragmatic balance between precision and recall. While Prophet and One-Class SVM achieved near-perfect recall (≈1.0), their precision was substantially low (often <0.03), leading to a high rate of false positives. In contrast, Night’s Watch maintained a precision of approximately , significantly reducing false alarms—a critical factor in production environments, where excessive alerts can cause fatigue and desensitization.

On the Speed 7578 dataset, which exhibits different temporal dynamics, Night’s Watch again led with an F1 score of , outperforming the RNN (), K-Means (), and Prophet (). Most notably, it achieved the highest precision (), showcasing its robustness in detecting meaningful anomalies while suppressing noise. From a data science perspective, this emphasis on precision is preferable in domains such as transportation, where false alarms can lead to costly manual investigations.

The RNN model failed to detect any anomalies for the Twitter datasets, resulting in 0.00 scores across metrics, and accordingly these results were excluded from the final comparison and marked N/A in

Table 2.

3.5. Runtime Complexity and Scalability

Floating-point operations (FLOPs) associated with both forward and backward passes of the Night’s Watch algorithm were calculated to assess computational overhead. The forward pass consists of approximately 41,872 FLOPs, accounting for operations across the Time2Vec layer, LSTM-based encoder and decoder networks, and loss computations including Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence. The backward pass, which includes gradient computations, typically requires 2–3× the operations of the forward pass, resulting in an estimated 146,552 FLOPs per training batch. Based on convergence behavior observed during empirical tests, a 6-epoch training window was adopted, yielding a total training cost of approximately 879,312 FLOPs. During training, the algorithm recorded a peak memory usage of 44.65% of the available 36 GB RAM (approximately 14 GB) and a single-core CPU utilization of roughly 32%.

4. Discussion

Comparing the Night’s Watch algorithm’s performance with existing methods in the literature, its ability to achieve high precision, particularly with the theoretical ground truth, is noteworthy. However, the trade-off with lower recall in some cases indicates that further tuning and perhaps hybrid approaches could be beneficial. For instance, the study by [

34] introduced an anomaly transformer model that combines multiple data sources to enhance detection accuracy, suggesting a potential direction for future improvements in the Night’s Watch algorithm. Moreover, the practical implications of these results are significant. The algorithm’s capability to enhance service sustainability by reducing false alarms without sacrificing detection accuracy suggests that it is well-suited for deployment in environments where maintaining system uptime is critical, such as in cloud-based microservices architectures.

Beyond its predictive performance, an equally important aspect of the Night’s Watch algorithm is its computational efficiency, which determines its practicality for large-scale deployment. This level of computational demand suggests that the model can be trained and deployed efficiently on standard hardware setups, including commodity cloud infrastructure or on-premise servers. In a production setting, the model may be encapsulated within a containerized microservice and orchestrated using platforms such as Kubernetes, enabling horizontal scaling in response to variable data loads. The relatively low FLOPs footprint also supports feasibility for near real-time anomaly detection, particularly when using batch inference or streaming mini-batches. The algorithm’s compact architecture further contributes to reduced latency and resource usage, making it suitable for continuous monitoring in microservice-based environments without compromising detection accuracy.

Moreover, the results also demonstrate that efficiency is complemented by strong generalization across different domains. The findings emphasize Night’s Watch’s strong generalization capabilities beyond its original domain of cloud-native microservices. Unlike Prophet and One-Class SVM, which heavily favor recall, or RNNs that require extensive data and fine-tuning, Night’s Watch achieves a balanced trade-off through its hybrid architecture. Specifically, it combines a Time2Vec temporal encoder with a Variational Autoencoder to capture both seasonal and structural patterns across domains.

Building on this balance between precision and recall, the algorithm further proves adaptable to different operational contexts. This approach not only adapts well to varying data rhythms but also scales efficiently, making it suitable for deployment in finance, social media, and transportation. In our view, its domain-agnostic design, combined with its effective control over both false positives and false negatives, renders Night’s Watch a practical and production-ready solution for real-world anomaly detection challenges. Nevertheless, as a limitation, formal ablation testing could not be conducted due to production-level deployment constraints, which will be addressed in future experimental replications.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we have developed and evaluated the Night’s Watch algorithm, a real-time anomaly detection system specifically designed for HangiKredi’s microservice architecture. The algorithm leverages advanced machine learning techniques, including Variational Autoencoders (VAE) and Time2Vec, to effectively monitor and predict system anomalies, ensuring high system reliability and minimal downtime.

Moreover, the algorithm’s architecture, built on the robust foundation of VAEs combined with the temporal modeling capabilities of Time2Vec, has proven effective in handling the intricate and dynamic nature of microservices. The use of synthetic, application-based, and combined ground truths in performance evaluation provided a comprehensive understanding of the algorithm’s strengths and areas for improvement. Notably, the combined ground truth experiments, which combine peak detection with real-world alarm data, highlight the practical applicability of the Night’s Watch algorithm in real-time environments.

Overall, while the 30-day period appears to be the most effective for training, the insights gained from these experiments will guide future iterations of the algorithm with a wider time window such as 90 days, particularly in addressing the challenges of disrupted temporal coherence and optimizing the balance between precision and recall. Future studies may focus on further improving the algorithm’s performance across different datasets and environments.

While the individual components of the proposed model—VAE and Time2Vec—are well-established in prior research, their integration within a real-time, cloud-native microservice setting offers meaningful practical value. In our view, such domain-specific adaptation, particularly within fintech systems, represents an important form of novelty by application, bridging methodological insight with real-world impact.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.D., B.C. (Baris Can), O.S. and B.C. (Bekir Cetintav); methodology, G.D. and B.C. (Baris Can); software, G.D., B.C. (Baris Can), C.B.E. and F.B.; validation, G.D., B.C. (Baris Can), C.B.E. and F.B.; formal analysis, G.D. and B.C. (Baris Can); investigation, G.D. and B.C. (Baris Can); resources, C.B.E. and F.B.; data curation, C.B.E. and F.B.; writing—original draft preparation, G.D. and B.C. (Baris Can); writing—review and editing, G.D., B.C. (Baris Can), O.S. and B.C. (Bekir Cetintav); visualization, C.B.E. and F.B.; supervision, O.S. and B.C. (Bekir Cetintav); project administration, G.D., B.C. (Baris Can), O.S. and B.C. (Bekir Cetintav). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author, due to restrictions related to the confidentiality of the company’s commercial information.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- O’Connor, R.V.; Elger, P.; Clarke, P.M. Continuous Software Engineering—A Microservices Architecture Perspective. J. Softw. Evol. Process 2017, 29, e1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrusto, A.; Engström, E.; Runeson, P. Optimization of Anomaly Detection in a Microservice System through Continuous Feedback from Development. In Proceedings of the 10th IEEE/ACM International Workshop on Software Engineering for Systems-of-Systems and Software Ecosystems, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 16 May 2022; pp. 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kaloudis, M. Evolving Software Architectures from Monolithic Systems to Resilient Microservices: Best Practices, Challenges and Future Trends. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolawole, I.; Fakokunde, A. Machine Learning Algorithms in DevOps: Optimizing Software Development and Deployment Workflows with Precision. Int. J. Comput. Appl. Technol. Res. 2025, 6, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidi, P.; Pahl, C.; Mendonça, N.; Lewis, J.; Tilkov, S. Microservices: The Journey So Far and Challenges Ahead. IEEE Softw. 2018, 35, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalapathy, R.; Chawla, S. Deep Learning for Anomaly Detection: A Survey. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1901.03407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, D.; Fang, J. The design and application of landslide monitoring and early warning system based on microservice architecture. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2020, 11, 928–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yan, M.; Yang, D.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z. Deep Attentive Anomaly Detection for Microservice Systems with Multimodal Time-Series Data. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference On Web Services (ICWS), Barcelona, Spain, 10–16 July 2022; pp. 373–378. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Nguyen, P.; Jin, H.; Nahrstedt, K. MIRAS: Model-based Reinforcement Learning for Microservice Resource Allocation over Scientific Workflows. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 39th International Conference On Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS), Dallas, TX, USA, 7–9 July 2019; pp. 122–132. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Doghman, F.; Moustafa, N.; Khalil, I.; Sohrabi, N.; Tari, Z.; Zomaya, A. AI-Enabled Secure Microservices in Edge Computing: Opportunities and Challenges. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2023, 16, 1485–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erich, F.; Amrit, C.; Daneva, M. A qualitative study of DevOps usage in practice. J. Softw. Evol. Process 2017, 29, e1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, W.; Xu, J.; Gu, Z. Workflow-Aware Automatic Fault Diagnosis for Microservice-Based Applications with Statistics. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2020, 17, 2350–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taibi, D.; Lenarduzzi, V.; Pahl, C. Processes, Motivations, and Issues for Migrating to Microservices Architectures: An Empirical Investigation. IEEE Cloud Comput. 2017, 4, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvaresi, D.; Marinoni, M.; Sturm, A.; Schumacher, M.; Buttazzo, G. The challenge of real-time multi-agent systems for enabling IoT and CPS. In Proceedings of the WI’17: International Conference On Web Intelligence, Leipzig, Germany, 23–27 August 2017; pp. 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, L.; Weber, I.; Zhu, L. DevOps: A Software Architect’s Perspective; Addison-Wesley Professional: Boston, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Merkel, D. Docker: Lightweight Linux containers for consistent development and deployment. Linux J. 2014, 2014, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Bandari, V. A comprehensive review of AI applications in Automated Container Orchestration, Predictive maintenance, security and compliance, resource optimization, and continuous Deployment and Testing. Int. J. Intell. Autom. Comput. 2021, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Ying, S.; Li, T.; Tian, X. TraceDAE: Trace-Based Anomaly Detection in Micro-Service Systems via Dual Autoencoder. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2025, 22, 4884–4897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Liu, Y. VAE-based Fault Diagnosis for Microservice System. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Ubiquitous Computing and Communications (IUCC), Chengdu, China, 20–22 December 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 78–85. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Chen, W.; Zhao, N.; Li, Z.; Bu, J.; Li, Z.; Qiao, H. Unsupervised Anomaly Detection via Variational Auto-Encoder for Seasonal KPIs in Web Applications. In Proceedings of the 2018 World Wide Web Conference, Lyon, France, 23–27 April 2018; pp. 187–196. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Feedforward Networks. Deep Learn. 2016, 1, 161–217. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep Learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidhuber, J. Deep Learning in Neural Networks: An Overview. Neural Netw. 2015, 61, 85–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogatinovski, J.; Nedelkoski, S.; Cardoso, J.; Kao, O. Self-supervised Anomaly Detection from Distributed Traces. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/ACM 13th International Conference on Utility and Cloud Computing (UCC), Leicester, UK, 7–10 December 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 342–347. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Xu, H.; Ouyang, Q.; Jiao, R.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, S.; Pei, D. Unsupervised Detection of Microservice Trace Anomalies through Service-Level Deep Bayesian Networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 31st International Symposium on Software Reliability Engineering (ISSRE), Coimbra, Portugal, 12–15 October 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 48–58. [Google Scholar]

- Nedelkoski, S.; Cardoso, J.; Kao, O. Anomaly Detection and Classification Using Distributed Tracing and Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 19th IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Cluster, Cloud and Grid Computing (CCGRID), Larnaca, Cyprus, 14–17 May 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 241–250. [Google Scholar]

- Nobre, J.; Pires, E.S.; Reis, A. Anomaly Detection in Microservice-Based Systems. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.; Welling, M. Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes. arXiv 2022, arXiv:1312.6114. [Google Scholar]

- Abadi, M.; Agarwal, A.; Barham, P.; Brevdo, E.; Chen, Z.; Citro, C.; Corrado, G.; Davis, A.; Dean, J.; Devin, M.; et al. TensorFlow: Large-Scale Machine Learning on Heterogeneous Systems. 2015. Available online: https://www.tensorflow.org/ (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- Kazemi, S.; Goel, R.; Eghbali, S.; Ramanan, J.; Sahota, J.; Thakur, S.; Wu, S.; Smyth, C.; Poupart, P.; Brubaker, M. Time2Vec: Learning a Vector Representation of Time. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.05321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhang, X.; Cao, Z.; Chen, Z. MADMM: Microservice system anomaly detection via multi-modal data and multi-feature extraction. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 15739–15757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Xie, T.; He, Y. Anomaly Detection and Diagnosis for Container-Based Microservices with Performance Monitoring. In Algorithms And Architectures for Parallel Processing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 560–572. [Google Scholar]

- Rusek, M.; Dwornicki, G.; Orłowski, A. A Decentralized System for Load Balancing of Containerized Microservices in the Cloud. Adv. Syst. Sci. 2017, 539, 142–152. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Wu, H.; Wang, J.; Long, M. Anomaly Transformer: Time Series Anomaly Detection with Association Discrepancy. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.02642. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).