Exploring the Effects of Barrier Thickness and Channel Length on Performance of AlGaN/GaN HEMT Sensors Using Off-the-Shelf AlGaN/GaN Wafers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

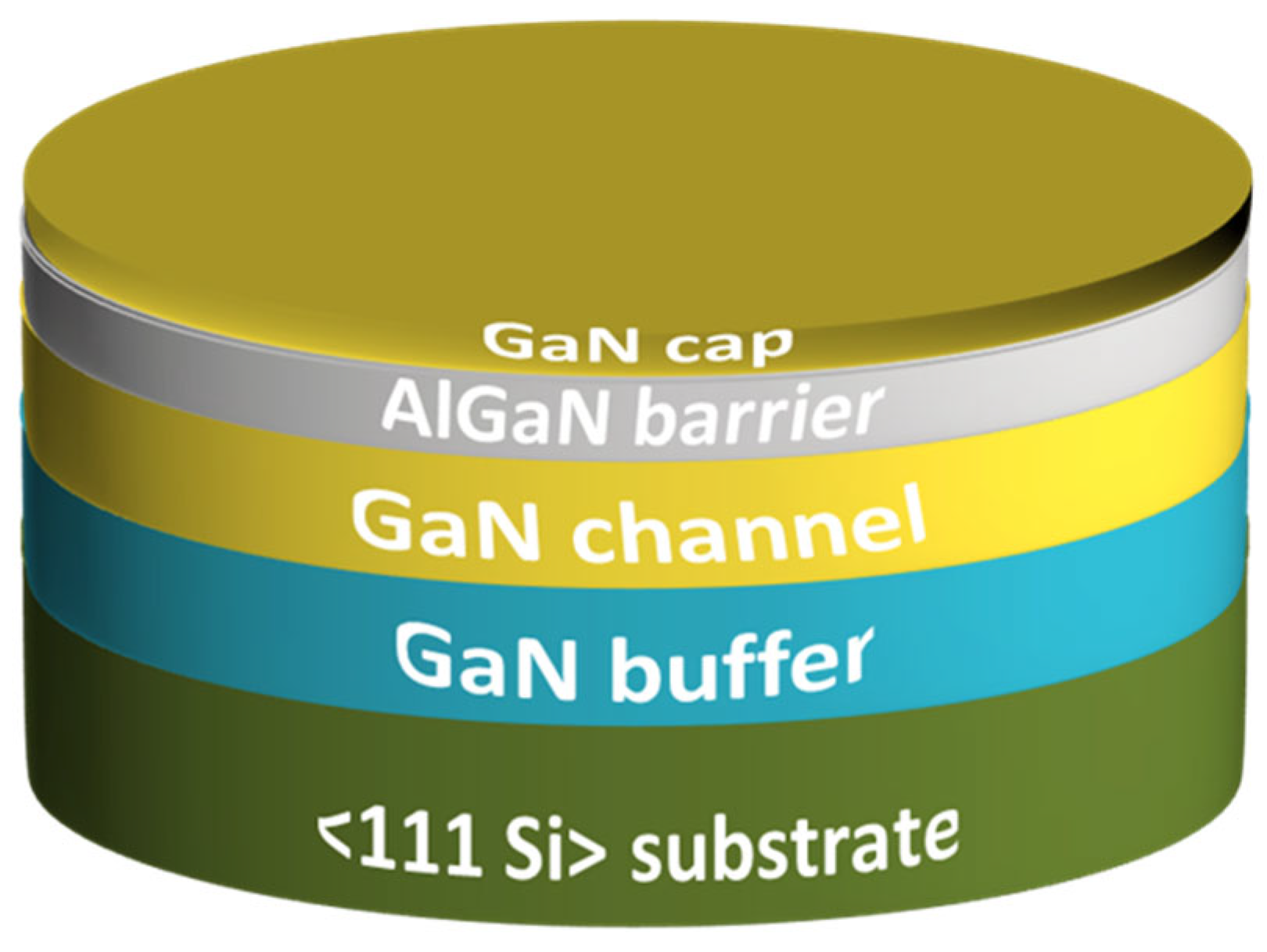

2.1. Materials

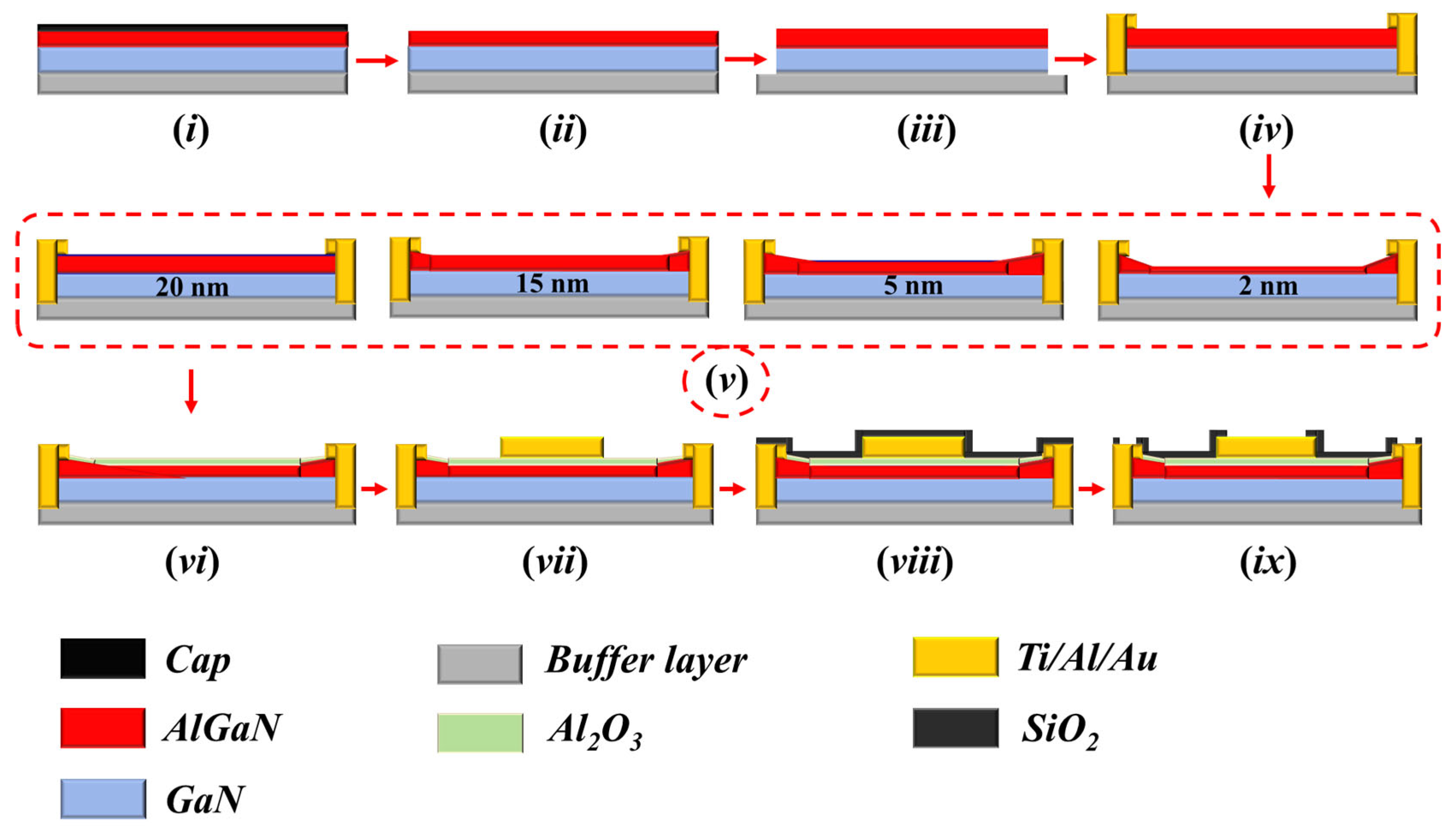

2.2. AlGaN/GaN FETs Fabrication and Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

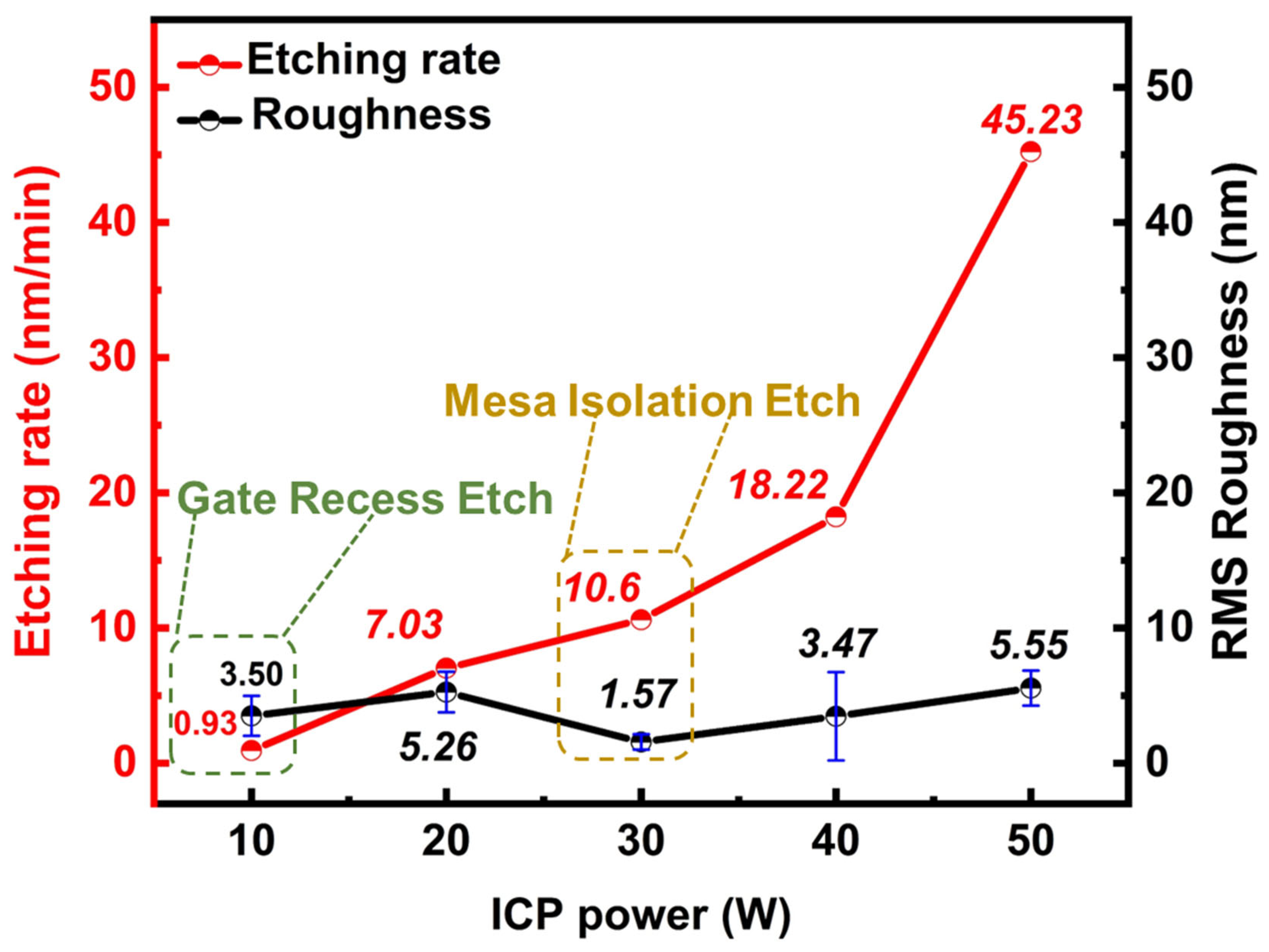

3.1. Etching Rate Optimization of AlGaN/GaN

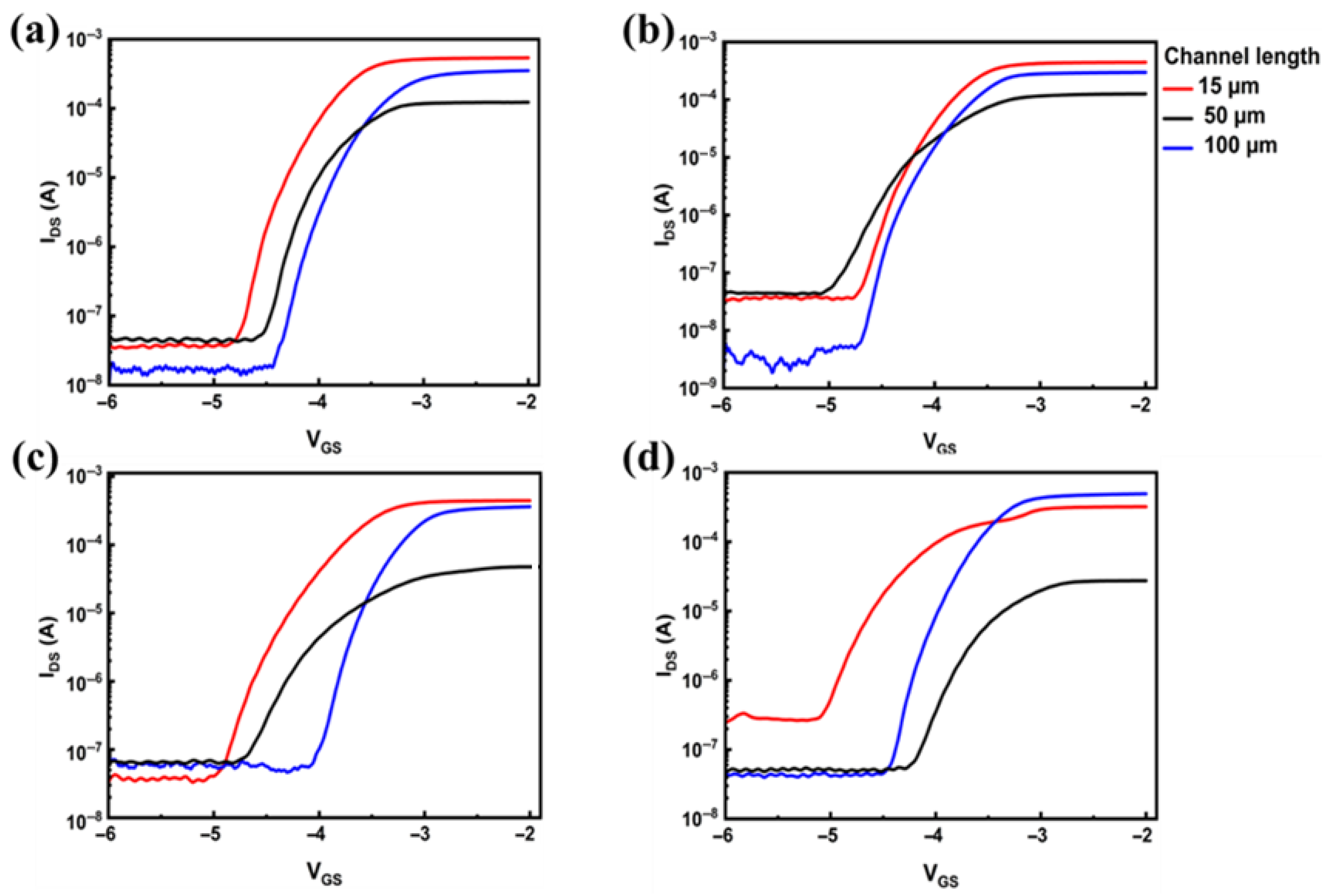

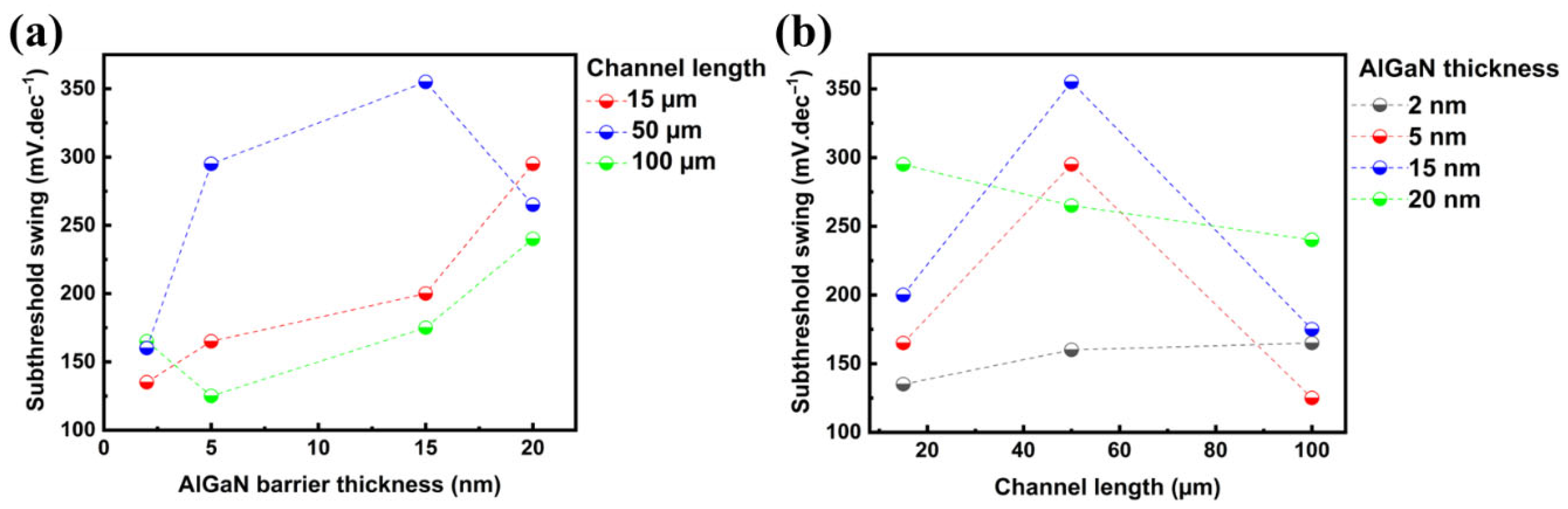

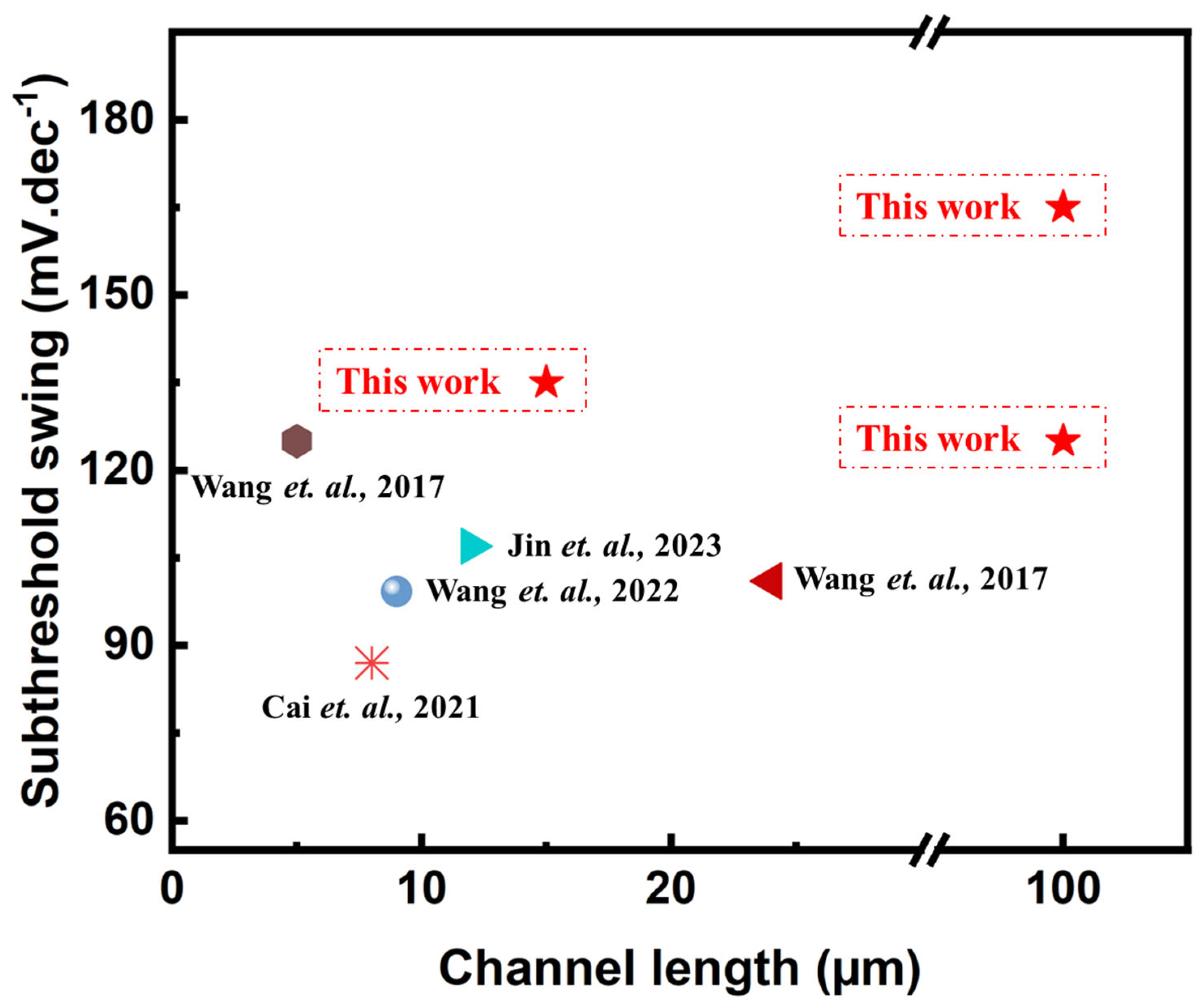

3.2. AlGaN/GaN FETs: AlGaN Barrier Thickness and Channel Length Effects

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bhat, A.M.; Poonia, R.; Varghese, A.; Shafi, N.; Periasamy, C. AlGaN/GaN high electron mobility transistor for various sensing applications: A review. Micro Nanostruct. 2023, 176, 207528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, T.-A.; Cha, H.-Y.; Kim, H. Response enhancement of pt–algan/gan hemt gas sensors by thin algan barrier with the source-connected gate configuration at high temperature. Micromachines 2021, 12, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, A.; Lingaparthi, R.; Dharmarasu, N. Investigation of thin-barrier AlGaN/GaN HEMT heterostructures for enhanced gas-sensing performance. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 18306–18312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, A.; Sehra, K.; Chanchal; Reeta; Narang, R.; Rawal, D.S.; Mishra, M.; Saxena, M.; Gupta, M. Impact of barrier layer thickness on DC and RF performance of AlGaN/GaN high electron mobility transistors. Appl. Phys. A 2023, 129, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristoloveanu, S.; Wan, J.; Zaslavsky, A. A review of sharp-switching devices for ultra-low power applications. IEEE J. Electron Devices Soc. 2016, 4, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, S.; Di Carlo, A.; Ruythooren, W.; Derluyn, J.; Germain, M. Scaling effects in AlGaN/GaN HEMTs: Comparison between Monte Carlo simulations and experimental data. J. Comput. Electron. 2006, 5, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Myeong, G.; Shin, W.; Lim, H.; Kim, B.; Jin, T.; Chalng, S.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Cho, S. Thickness-controlled black phosphorus tunnel field-effect transistor for low-power switches. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020, 15, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Sun, M.-Y.; Wang, Z.-H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, K.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Ren, T.-L.; Liu, H.; et al. Performance limits and advancements in single 2d transition metal dichalcogenide transistor. Nano-Micro Lett. 2024, 16, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-J.; Park, Y.-R.; Jang, H.-G.; Na, J.-H.; Lee, H.-S.; Ko, S.-C.; Jung, D.-Y.; Lee, H.-S.; Mun, J.-K.; Lim, J.-H.; et al. Al2O3 surface passivation and MOS-gate fabrication on AlGaN/GaN high-electron-mobility transistors without Al2O3 etching process. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2015, 54, 038003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, K.; Kikuta, D.; Ao, J.-P.; Ogiya, H.; Hiramoto, M.; Kawai, H.; Ohno, Y. Inductively coupled plasma reactive ion etching with SiCl4 gas for recessed gate AlGaN/GaN heterostructure field effect transistor. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2007, 46, 2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Miyashita, T.; Motoyama, S.-I.; Li, L.; Wang, D.; Ohno, Y.; Ao, J.-P. Process dependency on threshold voltage of GaN MOSFET on AlGaN/GaN heterostructure. Solid·State Electron. 2014, 99, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhirnov, E.; Stepanov, S.; Wang, W.N.; Shreter, Y.G.; Takhin, D.V.; Bochkareva, N.I. Influence of cathode material and SiCl4 gas on inductively coupled plasma etching of AlGaN layers with Cl2/Ar plasma. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2004, 22, 2336–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, J.; Cai, Y.; Liu, J.; Yang, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, M.; Yang, Z.; Xie, B.; Yu, M.; et al. 300 °C operation of normally-off AlGaN/GaN MOSFET with low leakage current and high on/off current ratio. Electron. Lett. 2014, 50, 315–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dub, M.; Sai, P.; Sakowicz, M.; Janicki, L.; But, D.B.; Prystawko, P.; Cywiński, G.; Knap, W.; Rumyantsev, S. Double-Quantum-Well AlGaN/GaN Field Effect Transistors with Top and Back Gates: Electrical and Noise Characteristics. Micromachines 2021, 12, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillbanks, J.; Umana-Membreno, G.; Myers, M.; Nener, B.D.; Parish, G. Prediction of Anomalous Variation in GaN-based Chemical Sensors. In Proceedings of the 2022 11th International Conference on Control, Automation and Information Sciences (ICCAIS), Hanoi, Vietnam, 21–24 November 2022; pp. 397–405. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, J.; Wu, G.; Guo, Y.; Liu, B.; Wei, X.; Chen, Q. The intrinsic origin of hysteresis in MoS2 field effect transistors. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 3049–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, S.; Shiozaki, N.; Negoro, N.; Tsurumi, N.; Anda, Y.; Ishida, M.; Ueda, T. Improved hysteresis in a normally-off AlGaN/GaN MOS heterojunction field-effect transistor with a recessed gate structure formed by selective regrowth. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2017, 56, 091003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.-Y.; Hsu, W.-C.; Chen, W.-F.; Lin, C.-W.; Li, Y.-Y.; Lee, C.-S.; Sun, W.-C.; Wei, S.-Y.; Yu, S.-M. Investigation of AlGaN/GaN ion-sensitive heterostructure field-effect transistors-based pH sensors with Al2O3 surface passivation and sensing membrane. IEEE Sens. J. 2016, 16, 3514–3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.-Y.; Hsu, W.-C.; Lee, C.-S.; Chou, B.-Y.; Chen, W.-F. Enhanced performances of AlGaN/GaN ion-sensitive field-effect transistors using H2O2-grown Al2O3 for sensing membrane and surface passivation applications. IEEE Sens. J. 2015, 15, 3359–3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.-W.; Chen, S.-C.; Wu, T.-L. Analysis of the subthreshold characteristics in AlGaN/GaN HEMTs with a p-GaN gate. Microelectron. Reliab. 2021, 126, 114302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradeep, D.; Rawal, D.; Karmalkar, S. Comparison of two DC extraction methods for mobility and parasitic resistances in a HEMT. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2017, 64, 1528–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.T.T.; Tran, D.P.; Thierry, B. High performance indium oxide nanoribbon FETs: Mitigating devices signal variation from batch fabrication. Nanoscale Adv. 2019, 1, 4870–4877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Zhu, M.; Hu, Z.; Qi, M.; Yan, X.; Cao, Y.; Kohn, E.; Jena, D.; Xing, H. AlGaN/GaN MIS-HEMT on silicon with steep sub-threshold swing < 60 mV/dec over 6 orders of drain current swing and relation to traps. In Proceedings of the 2014 Silicon Nanoelectronics Workshop (SNW), Honolulu, HI, USA, 8–9 June 2014; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, H.; Huang, S.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Fan, J.; Yin, H.; Wang, X.; Wei, K.; Liu, J.; Zhong, Y.; et al. High-performance enhancement-mode GaN-based p-FETs fabricated with O3-Al2O3/HfO2-stacked gate dielectric. J. Semicond. 2023, 44, 102801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-C.; Liu, C.-H.; Huang, C.-R.; Shih, M.-H.; Chiu, H.-C.; Kao, H.-L.; Liu, X. Improved Ion/Ioff Current Ratio and Dynamic Resistance of a p-GaN High-Electron-Mobility Transistor Using an Al0.5GaN Etch-Stop Layer. Materials 2022, 15, 3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Mitrovic, I.Z.; Wen, H.; Liu, W.; Zhao, C. Low ON-State Resistance Normally-OFF AlGaN/GaN MIS-HEMTs With Partially Recessed Gate and ZrOₓ Charge Trapping Layer. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2021, 68, 4310–4316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, H.; Fang, Y.; Feng, Z.; Cai, S.; Lv, Y.; Zhou, X.; Yin, J.; Han, T.; Gu, G.; et al. High-uniformity and high drain current density enhancement-mode AlGaN/GaN gates-seperating groove HFET. IEEE J. Electron Devices Soc. 2017, 6, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMelo, C.; Hall, D.C.; Snider, G.L.; Xu, D.; Kramer, G.; El-Zein, N. High electron mobility InGaAs-GaAs field effect transistor with thermally oxidised AlAs gate insulator. Electron. Lett. 2000, 36, 84–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Joshi, D.; Chaturvedi, N. Influence of Source-Gate and Gate lengths variations on GaN HEMTs based biosensor. Phys. Semicond. Devices 2014, 2014, 229–230. [Google Scholar]

- Chahdi, H.; Helli, O.; Bourzgui, N.; Breuil, L.; Danovitch, D.; Voss, P.; Sundaram, S.; Aubry, V.; Halfaya, Y.; Ougazzaden, A.; et al. Sensors based on AlGaN/GaN HEMT for fast H2 and O2 detection and measurement at high temperature. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE SENSORS, Montreal, QC, Canada, 27–30 October 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnet, S. Conquering the ‘Kink’in Sub-Threshold Power MOSFET Behavior: A Simple Compact Modeling Approach. EDN Network 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jarndal, A.; Jarndal, A.; Arivazhagan, L.; Almajali, E.; Majzoub, S.; Bonny, T.; Mahmoud, S. Impact of AlGaN Barrier Thickness and Substrate Material on the Noise Characteristics of GaN HEMT. IEEE J. Electron Devices Soc. 2022, 10, 696–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahyazadeh, R. Effect of AlGaN Barrier Thickness on the Transconductance of AlGaN/GaN High Electron Mobility Transistors. ECS Trans. 2014, 60, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A.M.; Shafi, N.; Sahu, C.; Periasamy, C. AlGaN/GaN HEMT pH sensor simulation model and its maximum transconductance considerations for improved sensitivity. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 19753–19761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, S.K.; Satapathy, S.C.; Biswal, B.; Bansal, R. (Eds.) Microelectronics, Electromagnetics and Telecommunications: Proceedings of the Fourth ICMEET; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 803–809. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amen, M.T.; Tran, D.P.; Feroze, A.; Cheah, E.; Thierry, B. Exploring the Effects of Barrier Thickness and Channel Length on Performance of AlGaN/GaN HEMT Sensors Using Off-the-Shelf AlGaN/GaN Wafers. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12751. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312751

Amen MT, Tran DP, Feroze A, Cheah E, Thierry B. Exploring the Effects of Barrier Thickness and Channel Length on Performance of AlGaN/GaN HEMT Sensors Using Off-the-Shelf AlGaN/GaN Wafers. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12751. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312751

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmen, Mohamed Taha, Duy Phu Tran, Asad Feroze, Edward Cheah, and Benjamin Thierry. 2025. "Exploring the Effects of Barrier Thickness and Channel Length on Performance of AlGaN/GaN HEMT Sensors Using Off-the-Shelf AlGaN/GaN Wafers" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12751. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312751

APA StyleAmen, M. T., Tran, D. P., Feroze, A., Cheah, E., & Thierry, B. (2025). Exploring the Effects of Barrier Thickness and Channel Length on Performance of AlGaN/GaN HEMT Sensors Using Off-the-Shelf AlGaN/GaN Wafers. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12751. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312751