Neural Key Agreement Protocol with Extended Security

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Post-quantum key agreement protocols,

- Quantum key agreement protocols,

- Neural key agreement protocols.

1.1. Related Work

1.2. Our Contribution

- We introduce a novel probabilistic algorithm that allows two parties engaged in a neural key agreement protocol to privately compute the proportion of synchronized weights at intermediate stages, without revealing the actual weight values.

- Leveraging this algorithm, we develop a new key agreement protocol based on the non-binary TPM model proposed by [16].

- We perform a comprehensive security analysis of our protocol, evaluating its resilience against both naive and geometric attacks, and benchmark its robustness against the protocol presented in [16].

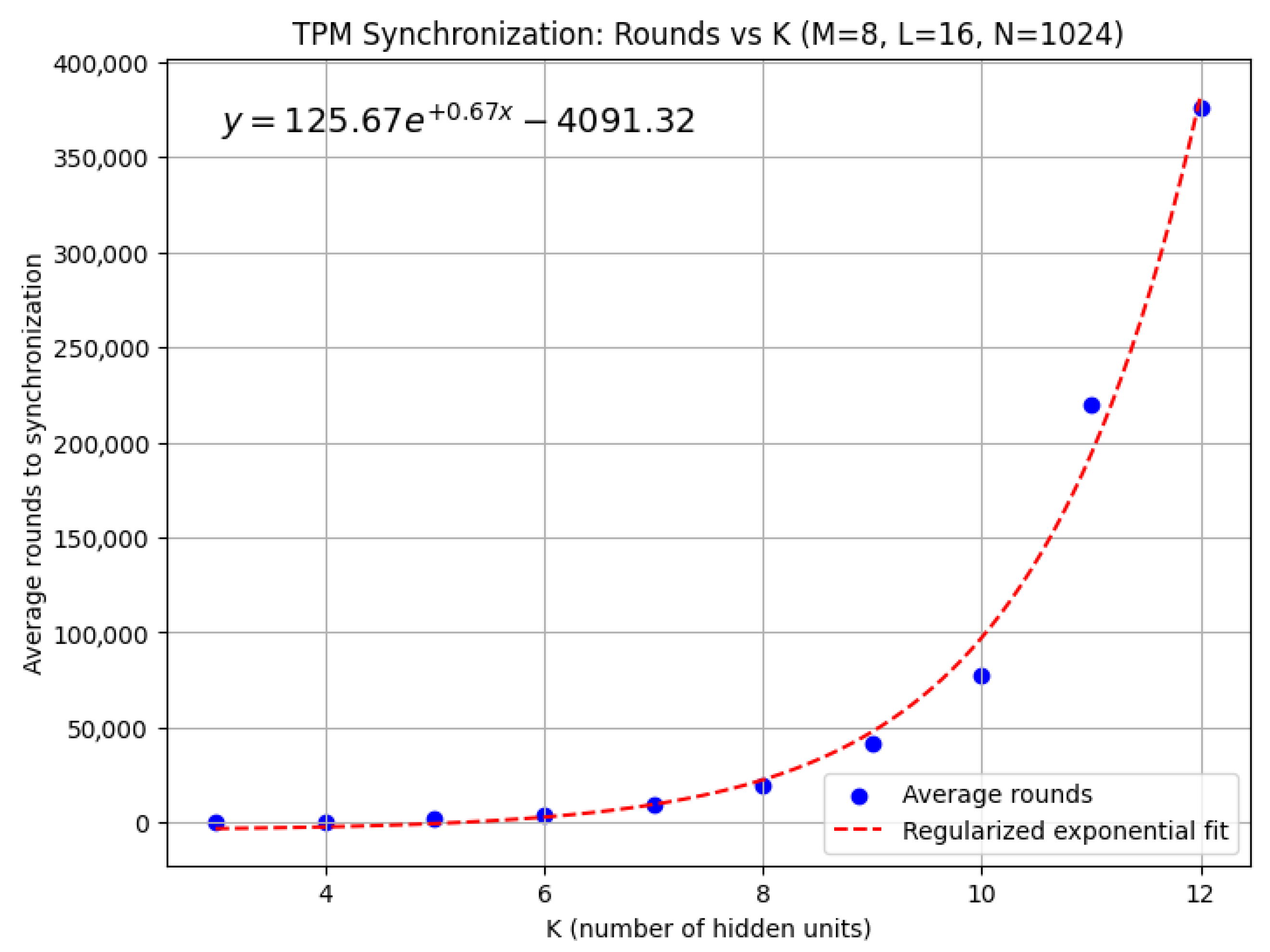

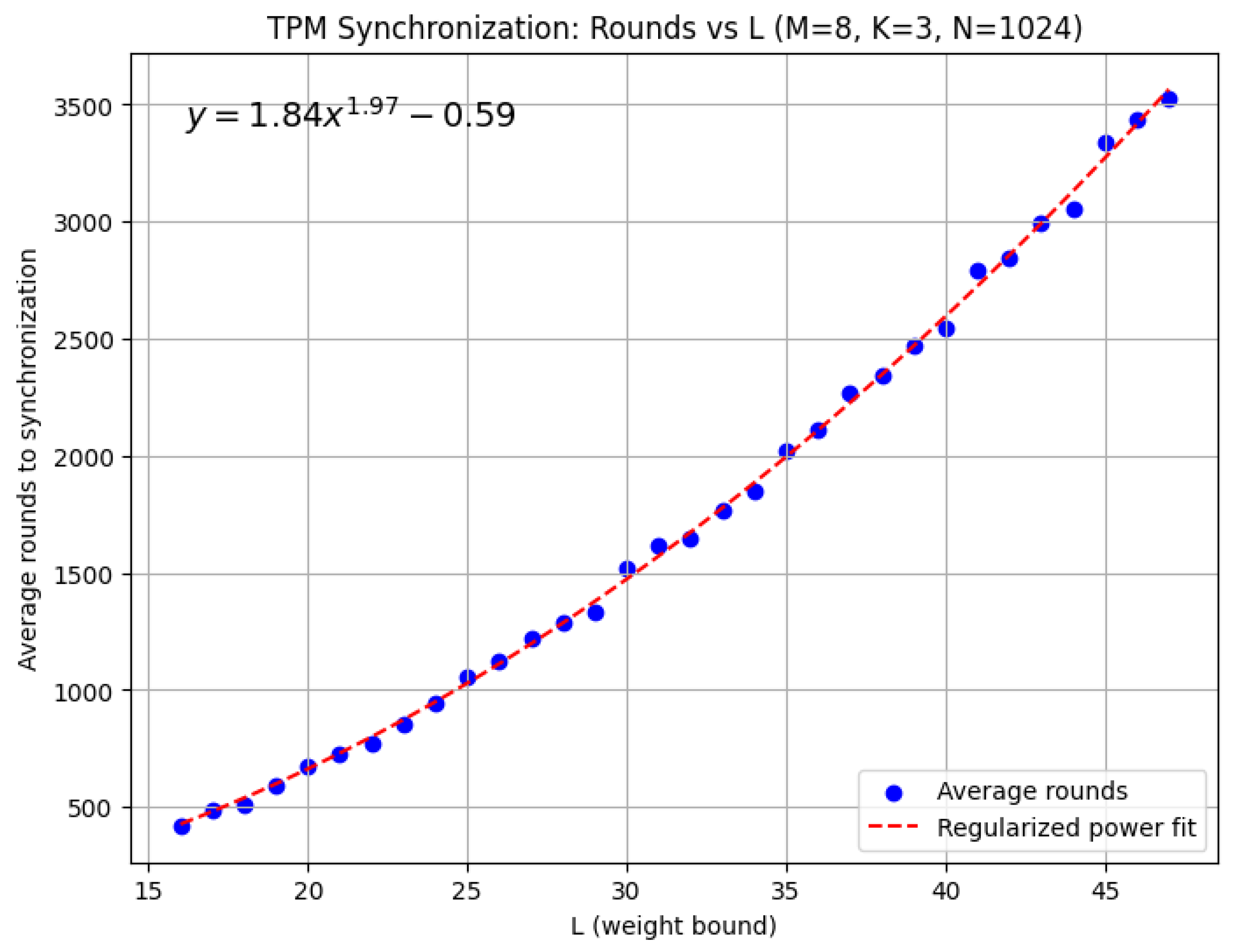

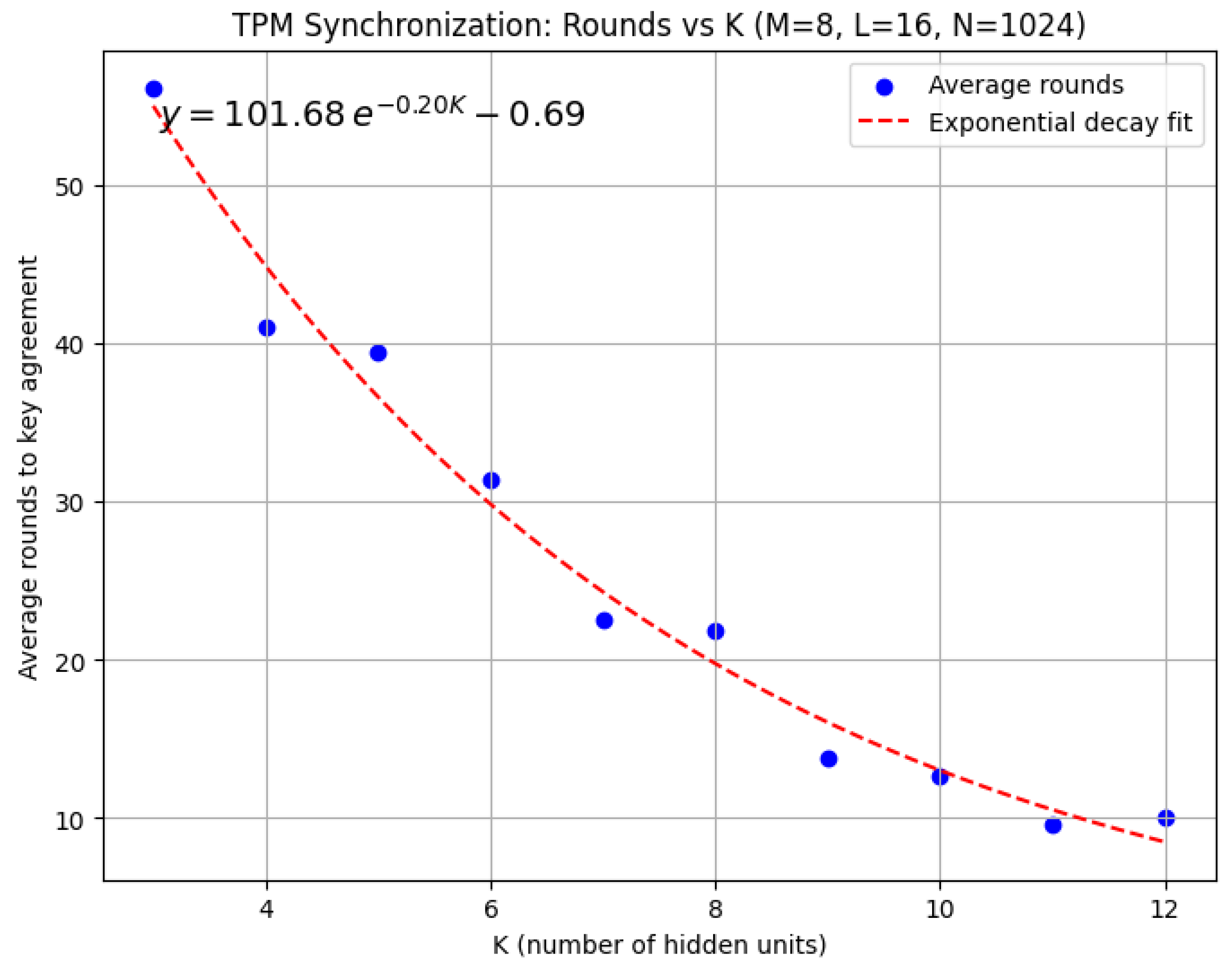

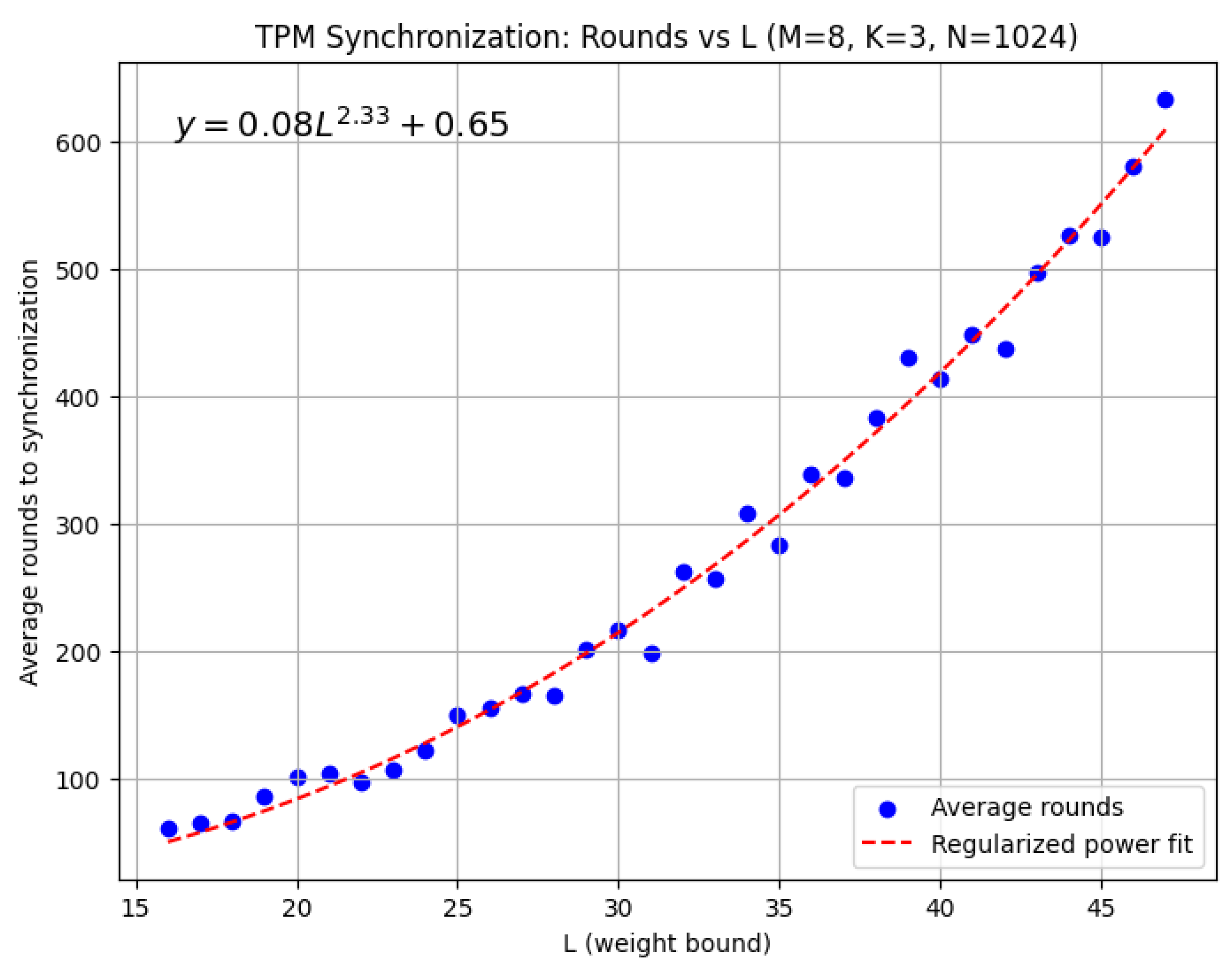

- We empirically demonstrate the efficiency of our protocol by analyzing its complexity in terms of the number of rounds required for synchronization, as a function of the number of hidden units in the TPM and the weight range, and compare these results with those of [16].

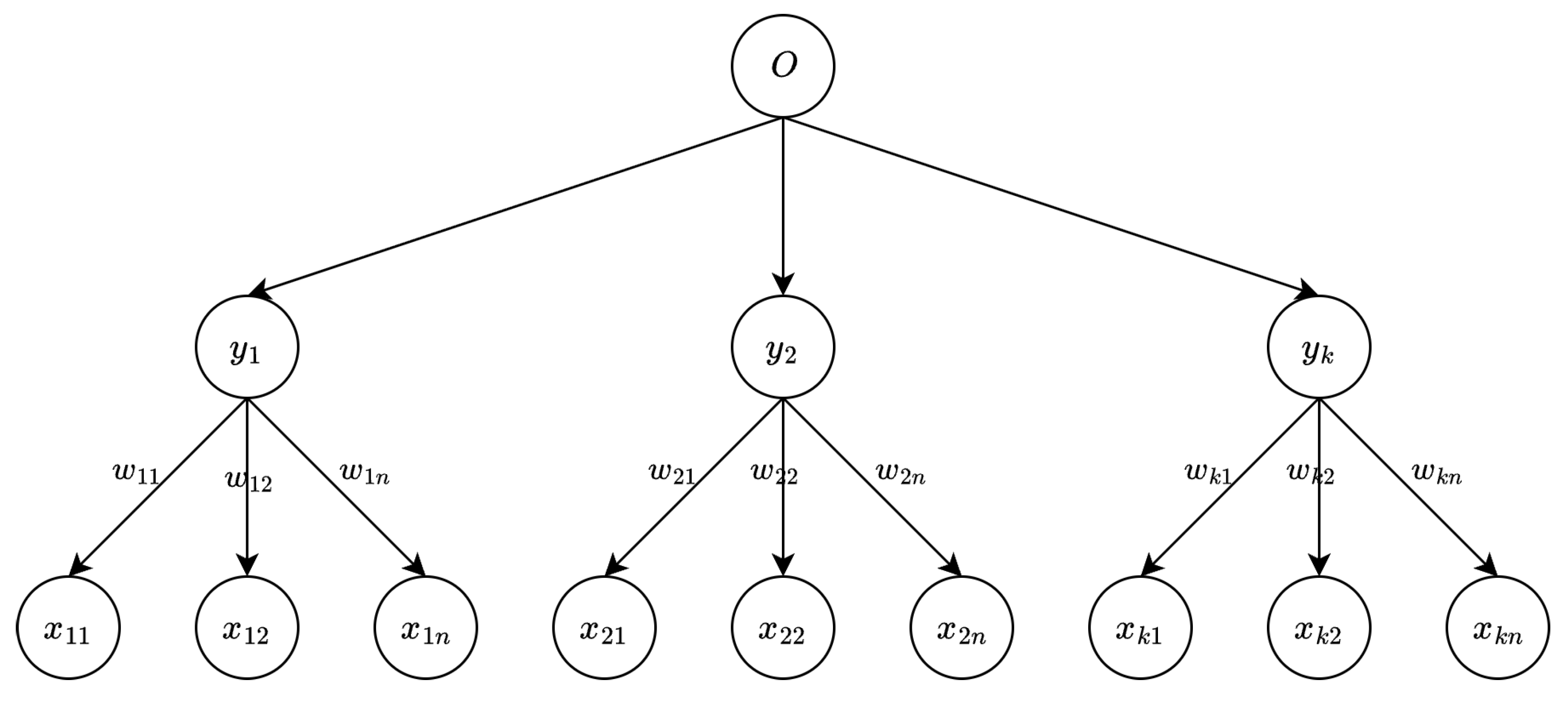

2. Tree Parity Machine

- is the weight of the i-th input to the j-th hidden neuron,

- is the corresponding input value,

- is the output of the j-th hidden neuron,

- O is the global output of the TPM,

- is the indicator function:

3. Weights Comparison Algorithm

- If , the probability that (i.e., a false positive) is at most .

- If , then with probability 1 (i.e., a true positive).

- With probability , .

- With probability , .

- Before is sent, the eavesdropper must consider all possible swap configurations to recover the real weights of .

- After is sent, the eavesdropper must consider at least possible swap configurations.

- Decoy Generation: initializes with its actual weights and generates a decoy vector , where each entry is sampled uniformly from the weight range:

- Random Swapping and Transmission: generates a random binary vector , where each entry is sampled uniformly from . For each index i, if , the entries and are swapped. Both vectors are then sent to :

- Comparison: compares each of its weights with and , constructing the mask vector:

- Threshold Verification and Response: computes . If , returns the mask vector to :

- Output: If , both parties output the set of synchronized weights:Otherwise, both parties output ⊥.

4. Neural Key Agreement Protocol

- Parameter Setup and Initialization: The parties and agree on the protocol parameters , and independently initialize their TPM weights uniformly at random:

- Input Generation: Both parties agree on a common random input vector x, either by exchanging the vector directly or by sharing a common random seed:

- Computation and Output Exchange: Each party computes the activations of the hidden neurons and the TPM output, then exchanges the output value with the other party:

- Weight Update: If the outputs coincide, each party updates its weights according to the Hebbian learning rule, but only for those hidden neurons whose activation matches the global output:

- Synchronization Check and Output: Both parties execute the protocol to privately estimate the number of synchronized weights. If the result is ⊥, indicating insufficient synchronization, the protocol returns to Step 2. Otherwise, both parties output the set of synchronized weights as the shared secret key.

- Attacker Initialization: The adversary independently initializes the weights of its own TPM:

- Local Computation: The attacker observes the public input vector x used by the legitimate parties and computes the activations of its hidden neurons and the output of its TPM:

- Synchronization Attempt: The attacker monitors the outputs and exchanged between the legitimate parties. Whenever , the attacker updates its weights according to the same Hebbian learning rule:

- Output: The attacker continues this process for as long as and execute the protocol. Upon termination, outputs its current weight vector as its estimate of the shared secret.

- Attacker Initialization: The adversary independently initializes the weights of its TPM:

- Local Computation: The attacker observes the public input vector x and, for each hidden unit j, computes:

- Geometric Update: The attacker observes the outputs and exchanged by the legitimate parties and proceeds as follows:

- Output: The attacker repeats the above steps for as long as and are executing the protocol. When the protocol terminates, outputs its current weight vector .

5. Experiments

6. Conclusions and Further Directions of Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cohn-Gordon, K.; Cremers, C.; Dowling, B.; Garratt, L.; Stebila, D. A formal security analysis of the signal messaging protocol. J. Cryptol. 2020, 33, 1914–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldreich, O. Foundations of Cryptography: Volume 2, Basic Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Shor, P.W. Polynomial-time algorithms for prime factorization and discrete logarithms on a quantum computer. SIAM Rev. 1999, 41, 303–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Wang, B.; Hu, F.; Wang, Y.; Fang, X.; Chen, X.; Wang, C. Factoring larger integers with fewer qubits via quantum annealing with optimized parameters. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 2019, 62, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagic, G.; Alagic, G.; Alperin-Sheriff, J.; Apon, D.; Cooper, D.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.K.; Miller, C.; Moody, D.; Peralta, R.; et al. Status Report on the First Round of the NIST Post-Quantum Cryptography Standardization Process; Technical Report; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2019.

- Paquin, C.; Stebila, D.; Tamvada, G. Benchmarking post-quantum cryptography in TLS. In Post-Quantum Cryptography, Proceedings of the 11th International Conference, PQCrypto 2020, Paris, France, 15–17 April 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 72–91. [Google Scholar]

- Pirandola, S.; Andersen, U.L.; Banchi, L.; Berta, M.; Bunandar, D.; Colbeck, R.; Englund, D.; Gehring, T.; Lupo, C.; Ottaviani, C.; et al. Advances in quantum cryptography. Adv. Opt. Photonics 2020, 12, 1012–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, I.; Kinzel, W.; Kanter, E. Secure exchange of information by synchronization of neural networks. EPL Europhys. Lett. 2002, 57, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimov, A.; Mityagin, A.; Shamir, A. Analysis of neural cryptography. In Proceedings of the International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security, Queenstown, New Zealand, 1–5 December 2002; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 288–298. [Google Scholar]

- Mislovaty, R.; Perchenok, Y.; Kanter, I.; Kinzel, W. Secure key-exchange protocol with an absence of injective functions. Phys. Rev. E 2002, 66, 066102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shacham, L.N.; Klein, E.; Mislovaty, R.; Kanter, I.; Kinzel, W. Cooperating attackers in neural cryptography. Phys. Rev. E 2004, 69, 066137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, E.; Mislovaty, R.; Kanter, I.; Ruttor, A.; Kinzel, W. Synchronization of neural networks by mutual learning and its application to cryptography. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004; Volume 17. [Google Scholar]

- Ruttor, A.; Kinzel, W.; Kanter, I. Neural cryptography with queries. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2005, 2005, P01009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, A.M.; Abbas, H.M. Improved security of neural cryptography using don’t-trust-my-partner and error prediction. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks, Atlanta, GA, USA, 14–19 June 2009; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Allam, A.M.; Abbas, H.M. On the improvement of neural cryptography using erroneous transmitted information with error prediction. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2010, 21, 1915–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stypiński, M.; Niemiec, M. Synchronization of Tree Parity Machines Using Nonbinary Input Vectors. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 35, 1423–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, S.; Park, C.; Hong, D.; Seo, C.; Jho, N. Neural cryptography based on generalized tree parity machine for real-life systems. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2021, 2021, 680782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, T.; Huang, T. Neural cryptography based on complex-valued neural network. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2019, 31, 4999–5004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stypiński, M.; Niemiec, M. Impact of Nonbinary Input Vectors on Security of Tree Parity Machine. In Multimedia Communications, Services and Security, Proceedings of the 11th International Conference, MCSS 2022, Kraków, Poland, 3–4 November 2022; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 94–103. [Google Scholar]

- Salguero Dorokhin, É.; Fuertes, W.; Lascano, E. On the development of an optimal structure of tree parity machine for the establishment of a cryptographic key. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2019, 2019, 214681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Sarkar, M. Tree parity machine guided patients’ privileged based secure sharing of electronic medical record: Cybersecurity for telehealth during COVID-19. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 21899–21923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, A. Secure exchange of information using artificial intelligence and chaotic system guided neural synchronization. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 18211–18241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Gupta, M.; Deshmukh, M. Single secret image sharing scheme using neural cryptography. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2020, 79, 12183–12204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plesa, M.I.; Gheoghe, M.; Ipate, F.; Zhang, G. A key agreement protocol based on spiking neural P systems with anti-spikes. J. Membr. Comput. 2022, 4, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.R.; Dean, M.E.; Plank, J.S.; Rose, G.S. A review of spiking neuromorphic hardware communication systems. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 135606–135620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruttor, A.; Kinzel, W.; Kanter, I. Dynamics of neural cryptography. Phys. Rev. E 2007, 75, 056104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Protocol | Core Idea/Modification | Advantages | Limitations/Comparison to Our Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kanter et al. [8] | Original TPM synchronization protocol over public channel | Simple, does not rely on trapdoor functions | Vulnerable to geometric attacks; no early termination mechanism |

| Mislovaty et al. [10] | Increased weight range to improve security | Reduces success rate of some attacks | Still vulnerable to advanced attacks; no protocol-level fix |

| Ruttor et al. [13] | Dynamic input generation based on internal state | Increases unpredictability, improves security | Increases synchronization time; more complex implementation |

| Allam et al. [14,15] | Output perturbation to confuse adversaries | Harder for attacker to reconstruct weights | Slower synchronization; more rounds required |

| Stypiński et al. [16] | Nonbinary input vectors for TPMs | Faster synchronization, improved efficiency | Security depends on parameters; geometric attacks still possible |

| Jeong et al. [17] | Vector-valued inputs for TPMs | Improves efficiency and security | Implementation complexity; not immune to all attacks |

| Dong et al. [18] | Complex-valued TPMs | Novel input representation; potential for higher security | Security analysis limited; practical deployment unclear |

| Salguero et al. [20] | Parameter optimization for TPMs | Systematic study of security vs. efficiency trade-offs | Does not address protocol-level vulnerabilities |

| Plesa et al. [24] | Spiking neural network TPMs | Improved efficiency on neuromorphic hardware | Security against geometric attacks not fully resolved |

| Our Protocol | Privacy-preserving synchronization check with early termination | Significantly reduces rounds; effectively mitigates geometric attacks | Readily integrates with existing TPM frameworks; offers promising potential for practical deployment |

| K | Protocol of [16] | Our Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | 0.03 | 0.22 |

| 4 | 0.05 | 0.22 |

| 5 | 0.13 | 0.24 |

| 6 | 0.37 | 0.20 |

| 7 | 0.83 | 0.20 |

| 8 | 1.69 | 0.18 |

| 9 | 3.81 | 0.16 |

| Protocol | Average (%) | Maximum (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Protocol of [16] | 9.75 | 28.32 |

| Our Protocol | 6.90 | 27.27 |

| Protocol | Average (%) | Maximum (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Protocol of [16] | 65.02 | 100.00 |

| Our Protocol | 6.90 | 27.27 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pleşa, M.-I.; Gheorghe, M.; Ipate, F. Neural Key Agreement Protocol with Extended Security. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12746. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312746

Pleşa M-I, Gheorghe M, Ipate F. Neural Key Agreement Protocol with Extended Security. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12746. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312746

Chicago/Turabian StylePleşa, Mihail-Iulian, Marian Gheorghe, and Florentin Ipate. 2025. "Neural Key Agreement Protocol with Extended Security" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12746. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312746

APA StylePleşa, M.-I., Gheorghe, M., & Ipate, F. (2025). Neural Key Agreement Protocol with Extended Security. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12746. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312746