1. Introduction

It has been known that there are three primary objectives in the area of suspension control: ride comfort, road holding, and suspension travel management [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

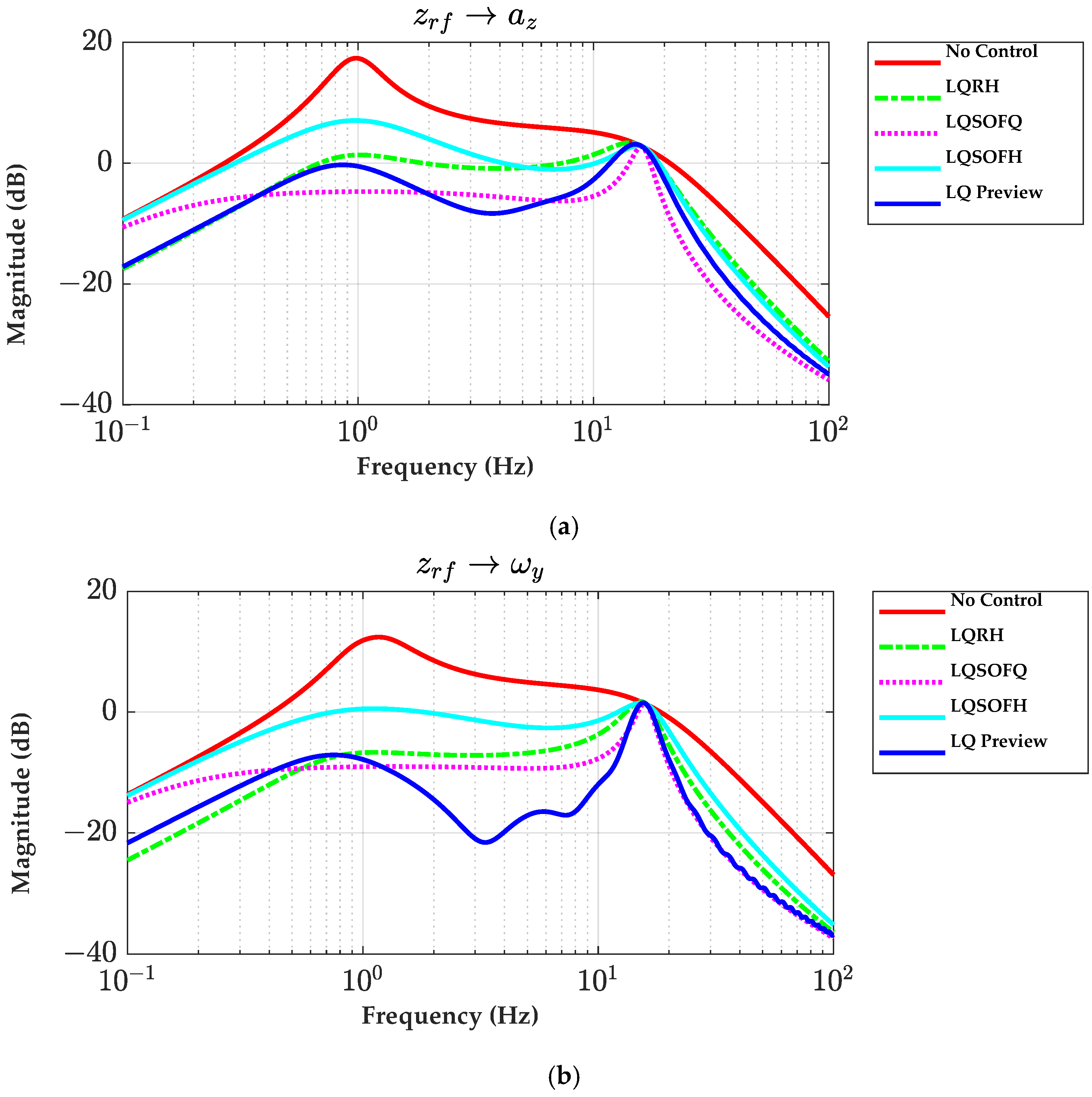

6]. Ride comfort is achieved by attenuating the vertical acceleration of sprung mass (SPM),

az, transmitted to occupants across a 0.5–20 Hz band, specified in ISO2631-1:1997, where human sensitivity is highest [

7]. Road holding is achieved by maintaining a sufficiently high tire-road normal force so that steering, braking, and traction remain predictable [

8]. Suspension travel management, or rattle-space protection, is achieved by preventing mechanical end-stops, limiting structural loads, and preserving component durability [

2]. Among those objectives, ride comfort and road holding are known to conflict with each other [

1,

2,

3,

4]. When designing a suspension controller for a real vehicle, those goals should be balanced. However, ride comfort is the primary consideration in routine straight-line driving. For this reason, most of the studies on suspension control have tried to improve ride comfort by reducing

az with an active or semi-active actuator [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

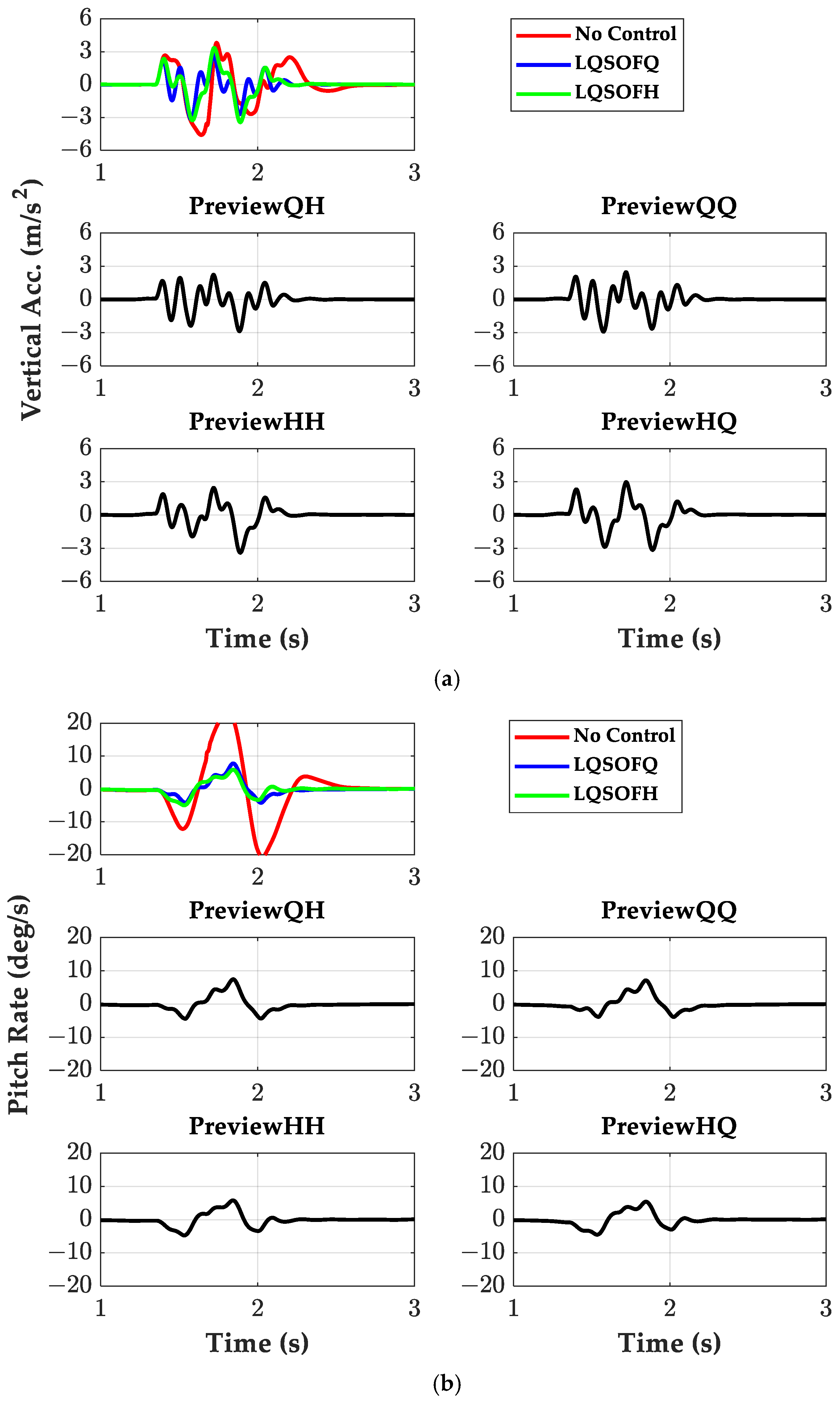

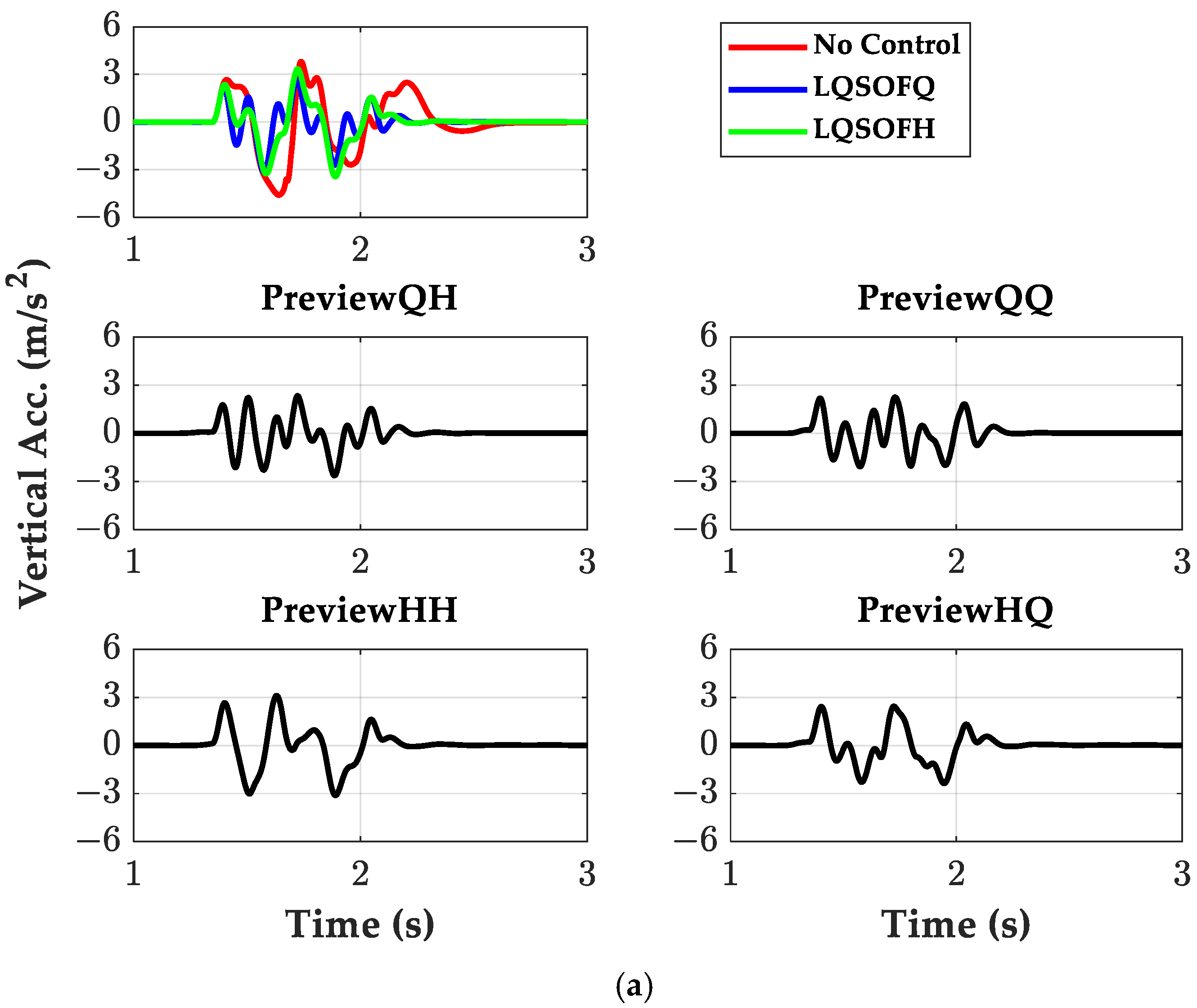

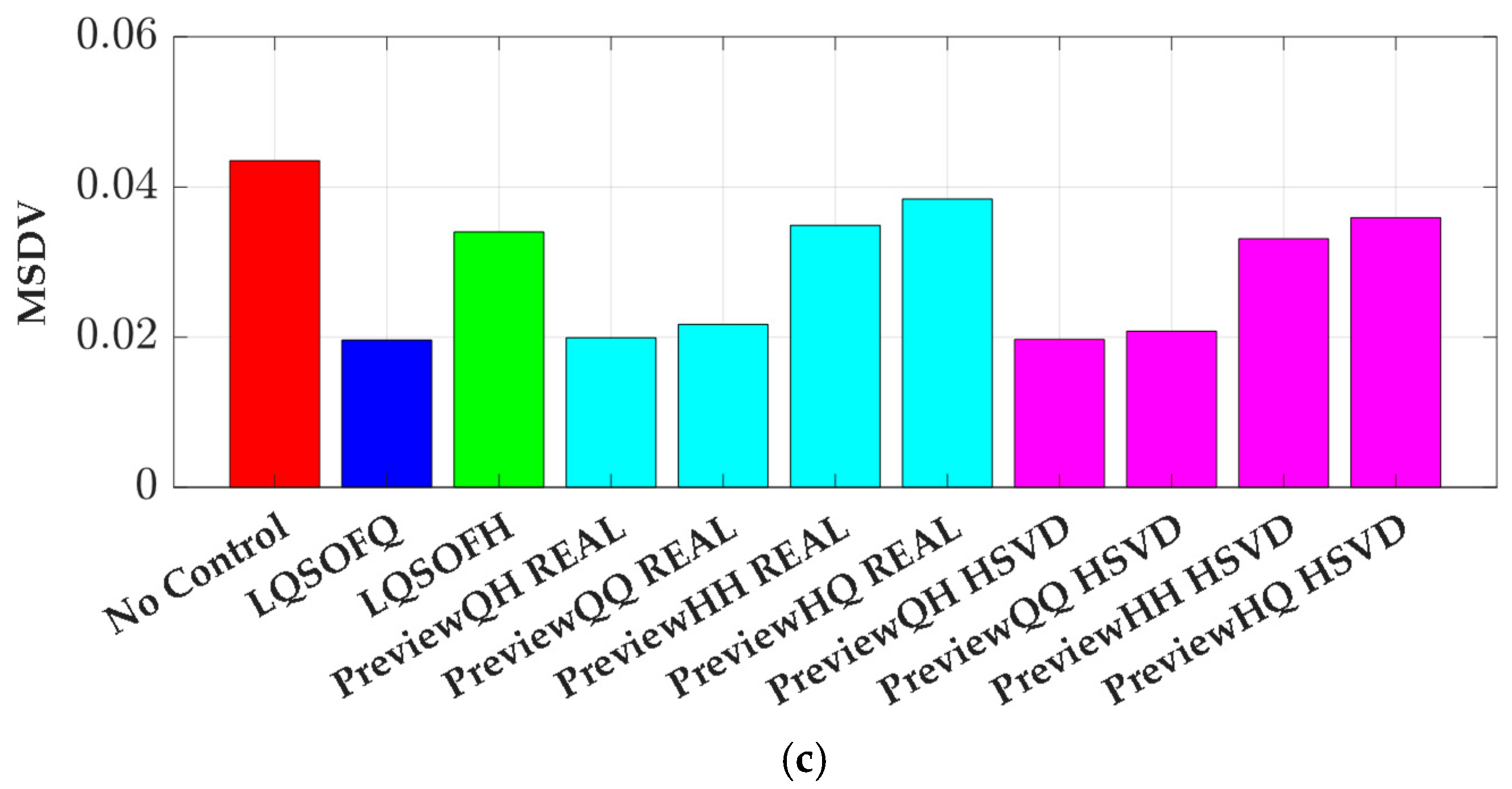

Three primary objectives in suspension control are evaluated with time- and frequency-domain metrics tailored to each goal. Generally, ride comfort is assessed via RMS or frequency-weighted RMS of

az, absorbed-power indices, and motion-sickness dose value (MSDV) for longer exposures [

7,

9,

10]. According to a recent study, motion sickness is attributable to the combined effects of

az and pitch rate of the SPM,

ωy [

11]. Accordingly, reducing

az and

ωy is necessary for ride-comfort enhancement and motion-sickness mitigation. Road holding is evaluated by dynamic tire load measures, RMS tire deflection, and contact patch force variation [

12]. Suspension travel management is evaluated with peak and RMS suspension deflection, end-stop hit counts, and probabilistic exceedance of bump/rebound limits [

2].

A wide spectrum of suspension control strategies has been proposed to improve ride comfort while respecting road holding and travel limits. Those strategies can be classified into active and semi-active approaches. Semi-active approaches such as skyhook, groundhook, hybrid sky/ground, and acceleration-driven damper modulate damping to emulate desirable force laws with low energy cost [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Recent reviews on semi-active suspension control report that, compared with passive suspensions, several semi-active control approaches, such as skyhook, robust, MPC, and rule-based ones, can deliver clear gains in ride comfort and road holding and can approach active-suspension performance in various road scenarios [

4]. Because those approaches require smaller actuators and modest electrical power, semi-active systems are cheaper, easier to package, and more reliable for production, which explains their wide commercial adoption (especially MR/CDC dampers) over the last decade [

13,

14]. However, since semi-active actuators cannot inject net energy into the suspension, their achievable control authority is fundamentally bounded, so performance deteriorates in severe disturbances or when severely aggressive body control is required [

4].

As fully active strategies, linear quadratic regulator (LQR) and linear quadratic Gaussian (LQG), H

∞/

μ-synthesis, sliding-mode, model predictive control (MPC), and disturbance-observer-based control have been applied to date [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. A recent study integrates multi-actuator coordination (heave/roll/pitch) and explicit constraint handling via MPC to respect travel, tire force, and actuator limits [

5]. Data-driven and adaptive extensions refine parameters online to accommodate speed/load variability and changing road roughness [

15,

16]. Road-preview layers such as wheelbase, LiDAR/camera, and map-based augment these feedback cores by turning upcoming road inputs into anticipatory control actions [

17,

18,

19]. In this paper, an active suspension is selected as an actuator because the goal of this paper is to propose a new method for preview controller design.

Among those control strategies for suspension control, LQR with active suspension provides a systematic tuning framework through the LQ performance index (LQPI) and yields stabilizing feedback for controllable systems [

1,

2,

4,

20]. LQG extends LQR with Kalman filtering, enabling output-feedback designs while preserving the separation principle [

21]. In suspension applications, LQ-based designs have historically delivered strong baselines and insight into achievable comfort/handling trade-offs [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Advantages of LQ-based design include smooth control actions, analytic performance interpretation, and low online computational demand once gains are computed offline [

21]. However, classic LQR/LQG does not natively enforce hard constraints on travel, actuator stroke/force, or tire loads, which motivates MPC or constrained extensions [

22].

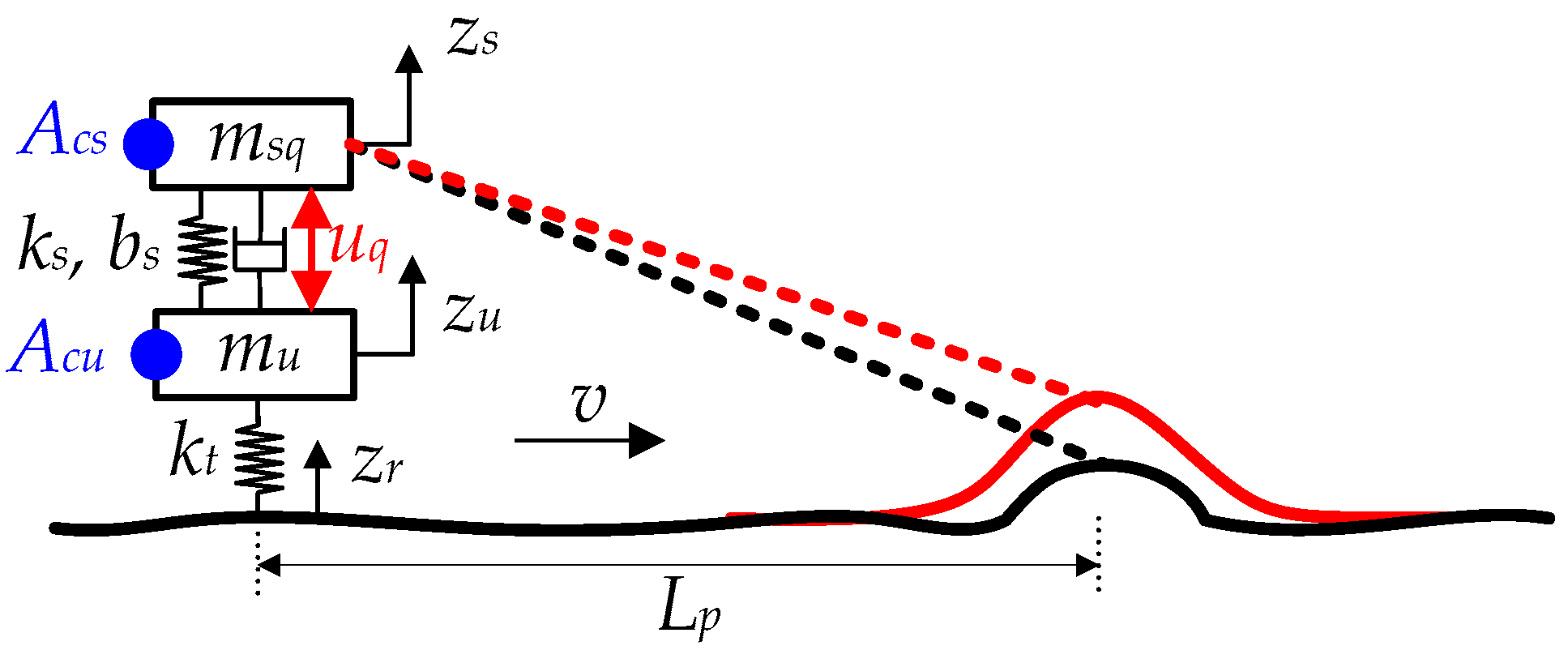

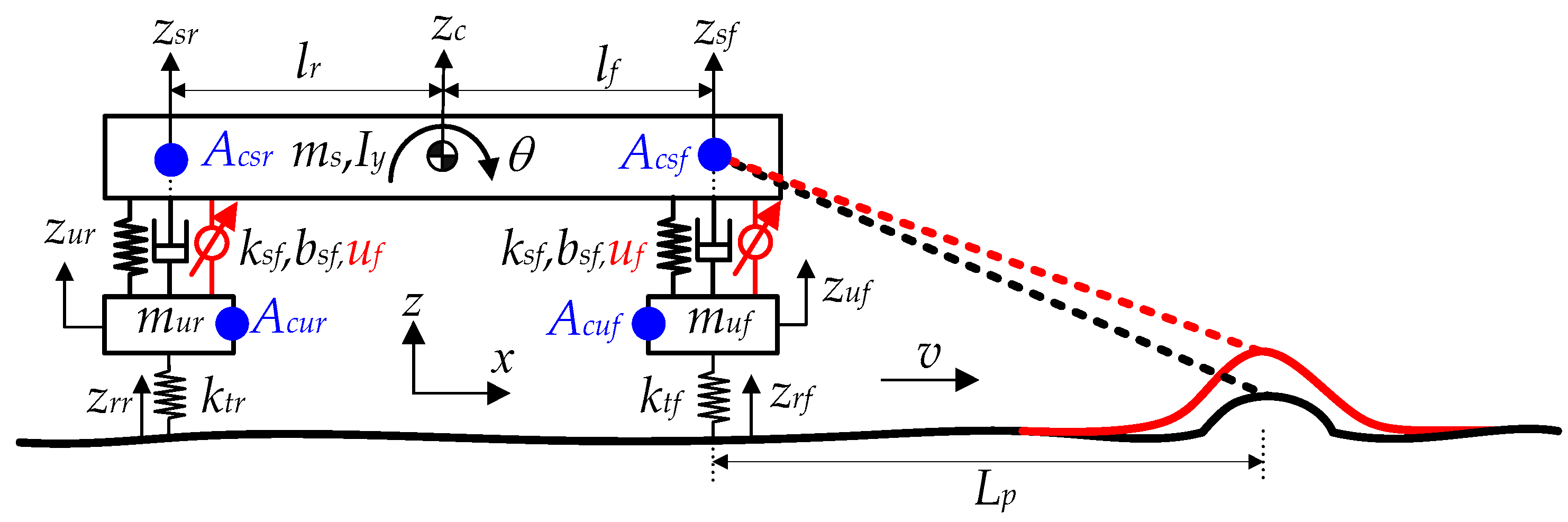

To apply LQ methods to suspension control, a state-space representation of a vehicle model is required. Prior studies have primarily employed three canonical formulations for active-suspension control synthesis: the 2-DOF quarter-car, the 4-DOF half-car, and the 7-DOF full-car models [

23,

24,

25,

26]. Among these, the quarter-car model is the most widely used owing to its simplicity and analytical tractability. In this paper, an active-suspension controller is designed using a half-car model, which explicitly captures the SPM heave (vertical) and pitch motions. Because the half-car model can be viewed as two coupled quarter-car ones, controllers designed with the quarter-car model can often be embedded within the half-car or full-car model with minor modifications [

23,

24,

25]. For example, in 2024, the quarter-car-based controller was designed and validated with the semi-active suspension or on a real vehicle [

25]. In this study, an active suspension is adopted as the actuator for control force generation, as it can be represented in the vehicle model with a relatively simple structure, and its control bandwidth can be modeled in a straightforward manner.

From a structural standpoint, LQR implements full-state feedback (FSF) and therefore requires all state variables to be either measured or estimated via a state observer or estimator. In a real vehicle, however, direct measurement of the half-car state vector is impractical. To circumvent this requirement in this paper, a static output-feedback (SOF) architecture is adopted instead of observer-based FSF control [

4]. Specifically, the SPM vertical velocity and the suspension stroke rate are selected as sensor outputs for the SOF control in this paper; these outputs arise naturally from both quarter-car and half-car models, which enables an SOF controller synthesized on the quarter-car model to be ported to the half-car or full-car one with minimal modification [

23,

24,

25]. The LQ SOF controller is obtained by minimizing an LQPI subject to the selected output structure. In this paper, two LQ SOF controllers are proposed as feedback controllers: (i) one designed with the quarter-car model and deployed on the half-car model, and (ii) one designed directly with the half-car model. Within the preview-control framework, each SOF controller is augmented by a feedforward path to use measured/previewed road inputs. To date, only a few studies have investigated preview control that employs LQ SOF control as the feedback controller [

17,

18]. This is the main contribution of this study.

Feedforward control acts with known or measured disturbances before these enter the plant, thereby reducing the burden on feedback and lowering tracking or regulation error [

27,

28]. Because it bypasses plant phase lags, properly timed feedforward control can attenuate incoming disturbances at the input and improve transient response without requiring higher feedback gains. In combination, feedback control cleans up model errors and unmeasured disturbances, while feedforward control cancels the predictable component, increasing effective bandwidth and robustness margins.

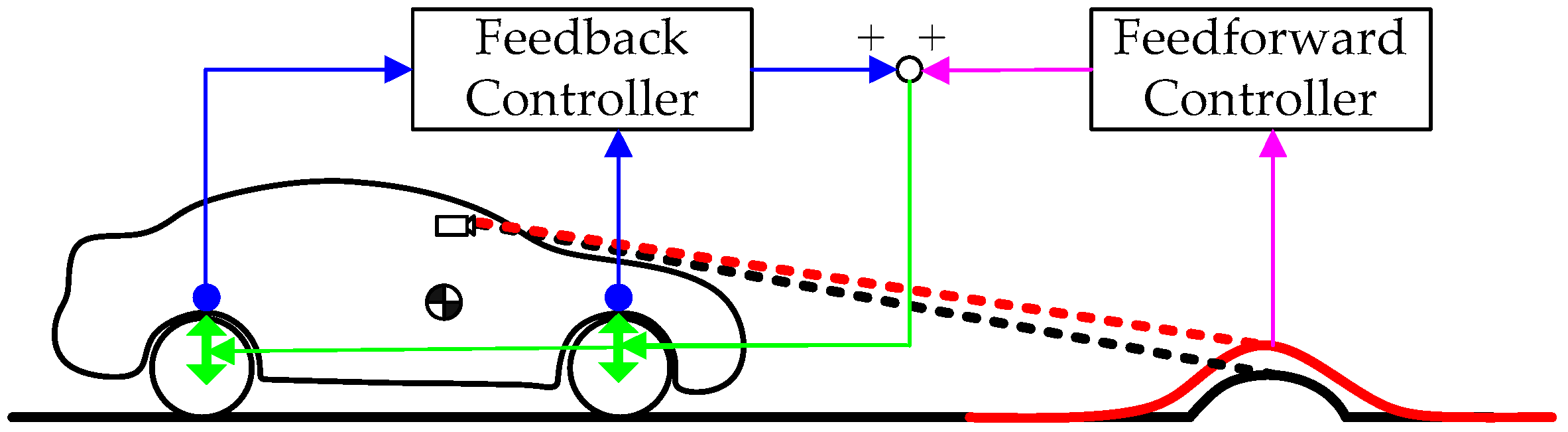

In the area of suspension control, preview control is the sum of feedback and feedforward controls [

17,

18,

19]. Previewed signals can come from wheelbase preview (front-to-rear delay), perception sensors such as LiDAR or stereo cameras, or map/V2X sources aligned to vehicle speed [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. Optimal preview control augments the plant with future disturbance samples and computes anticipatory actions—often within LQG or

H2/

H∞ frameworks—to reduce body acceleration and suspension travel [

16,

17]. MPC variants use predicted road inputs over a finite horizon to enforce travel, tire-load, and actuator constraints explicitly [

36]. Practical implementations must address speed-dependent preview time, sensor latency/noise, and alignment/registration between sensed profile and wheel contact points [

17,

18,

19].

Preview control performance depends critically on accurate and timely road-profile estimation; sensor noise, latency, and calibration misalignment can substantially degrade effectiveness, particularly in vision-based approaches. In practice, robust reconstruction of bump profiles from onboard cameras remains challenging across diverse operating conditions, and discrepancies between the reconstructed and true profiles have been reported [

37]. To address these limitations in this paper, instead of measuring a real bump, a parameterized virtual disturbance is adopted and embedded in the preview path [

38,

39]. The resulting architecture—illustrated in

Figure 1 (highlighted with a red solid line)—eliminates the need for real-time bump measurement while enabling deliberate shaping of the feedforward signal to enhance closed-loop performance [

39]. The virtual-disturbance parameters are optimized via a simulation-based optimization method (SBOM) for better control performance. The complete preview-control system is realized in a MATLAB2019a/Simulink–CarSim8.0 co-simulation environment in this paper.

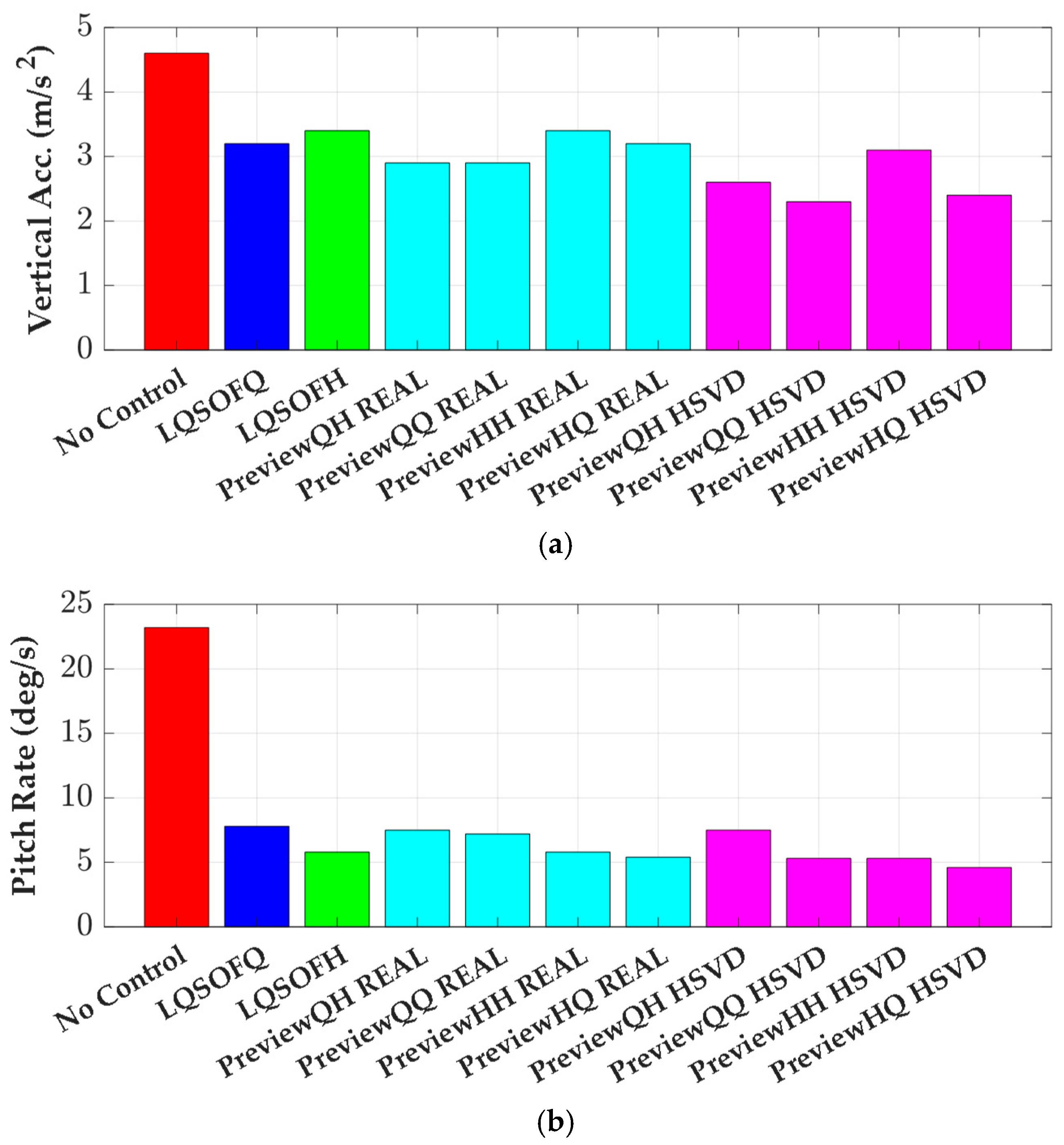

The objective of this paper is to design a preview controller augmented with a virtual disturbance to enhance ride comfort and to mitigate motion sickness. The main contributions are as follows:

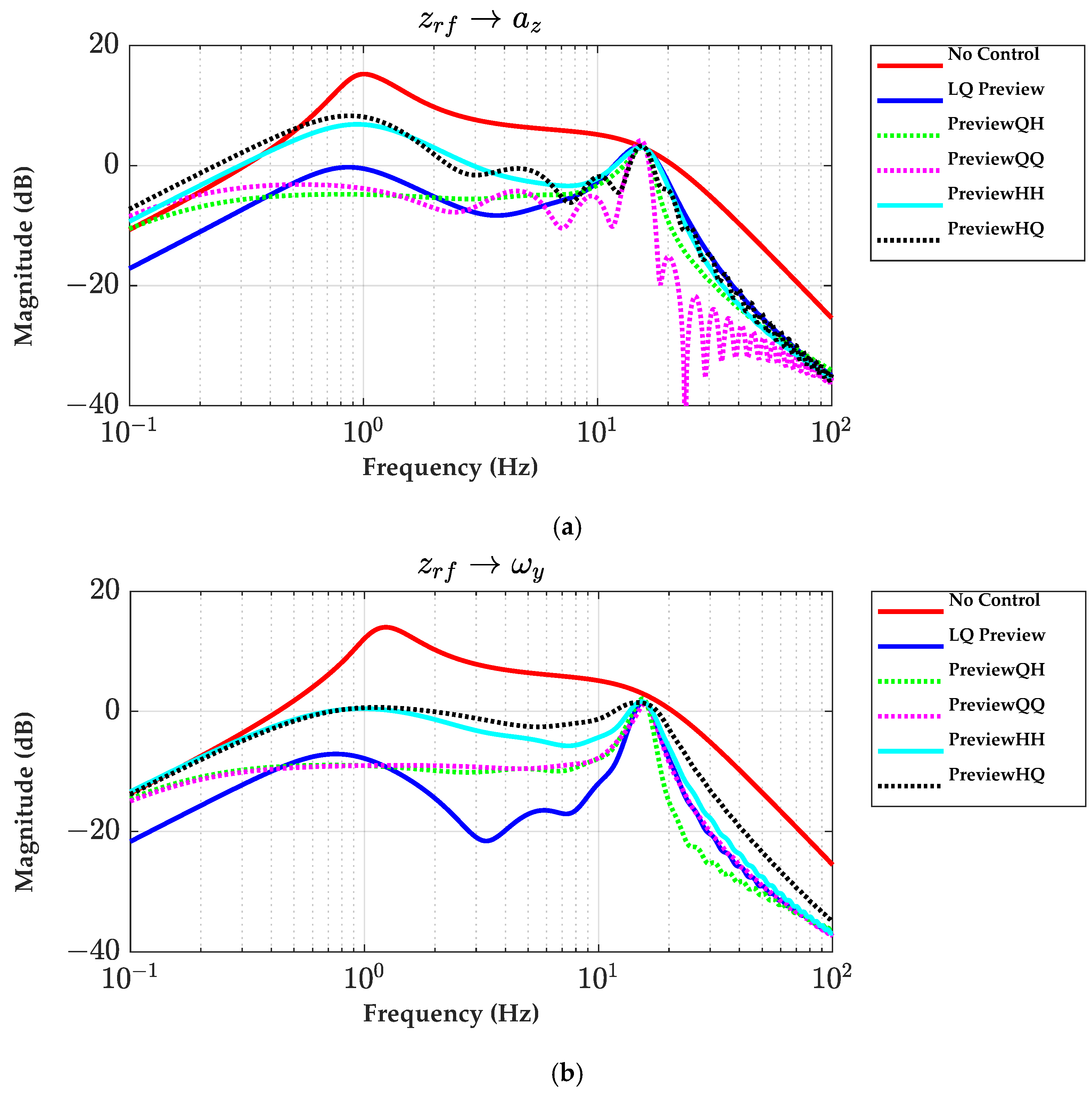

Feedback and preview synthesis. As a feedback part of the preview controller, two LQ SOF controllers are designed using the quarter-car and half-car models in the discrete-time domain, respectively. In parallel, two feedforward schemes are derived from the same models. Pairwise combination of feedback and preview designs yields four discrete-time preview controllers. Existing literature on preview control with an LQ SOF controller is scarce [

17,

18]. For this reason, this is the key contribution of this paper.

Virtual disturbance and optimization. The feedforward path employs a virtual disturbance instead of a real bump, eliminating explicit road-profile sensing. For better control performance, the virtual disturbance is optimized via SBOM on a MATLAB2019a/Simulink–CarSim8.0 co-simulation environment. The optimized virtual disturbance can enhance the performance of the preview controller and reduce sensitivity to mismatch between assumed and actual bump profiles.

Simulation-based validation. Performance is assessed in CarSim8.0 by evaluating the two LQ SOF controllers and the four preview controllers augmented with their optimized virtual disturbances.

This paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 formulates the quarter-car and half-car models and derives their state-space equations. Building on these models, active-suspension controllers are synthesized using LQ SOF and LQ optimal preview control. In

Section 3, the virtual disturbance is introduced and employed in the feedforward path, and its parameters are optimized.

Section 4 presents the simulation setup and evaluates the closed-loop performance of the designed preview controllers.

Section 5 concludes the paper.

3. Design of Virtual Disturbance with SBOM

In the prior works, a normal-distribution–shaped virtual reference (NDVR) was introduced to emulate road bumps for feedforward control [

38,

39]. Following the idea of the prior works, this paper adopts the same principle that eliminates direct measurement or estimation of a physical bump profile. In this paper, this concept is extended to preview control by replacing a real bump signal with a virtual disturbance.

The NDVR proposed in the previous work is given in Equation (38) [

39]. In Equation (38), there are three parameters in NDVR: the height

h, width

σ, and the center position

μ. However, it is not easy to tune those parameters due to the nonlinear term,

h/

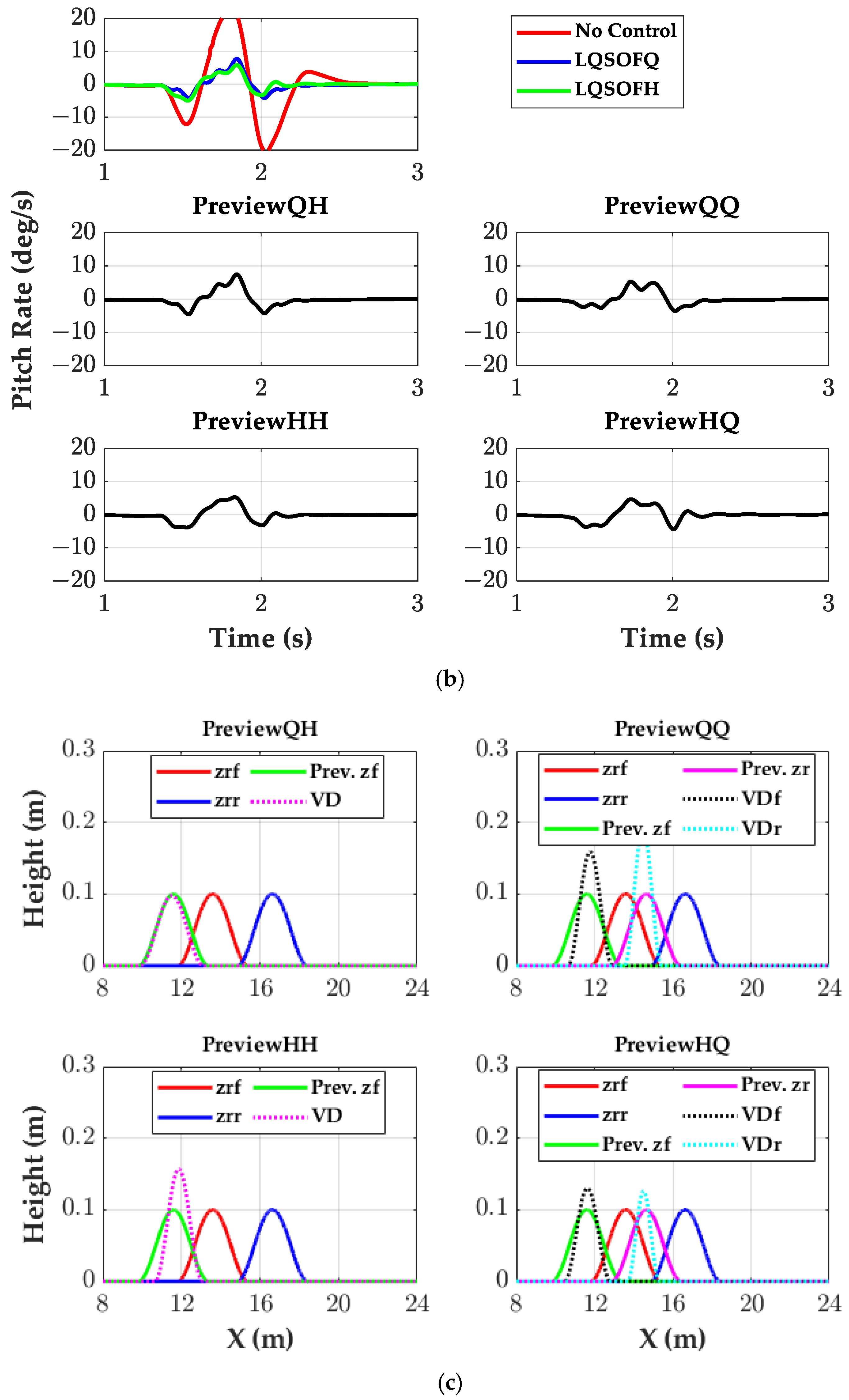

σ. In other words, it is not intuitive to shape NDVR with those parameters. Moreover, due to the nonlinear term, increasing the temporal width unavoidably distorts the peak magnitude, making it difficult, for example, to generate a wider reference with a smaller height. To cope with the problem, a half-sine virtual disturbance (HSVD), defined in Equation (39), is adopted as the previewed one in this paper. This choice preserves key temporal and amplitude characteristics of typical bump excitations while enabling a compact parametric description compatible with the preview horizon.

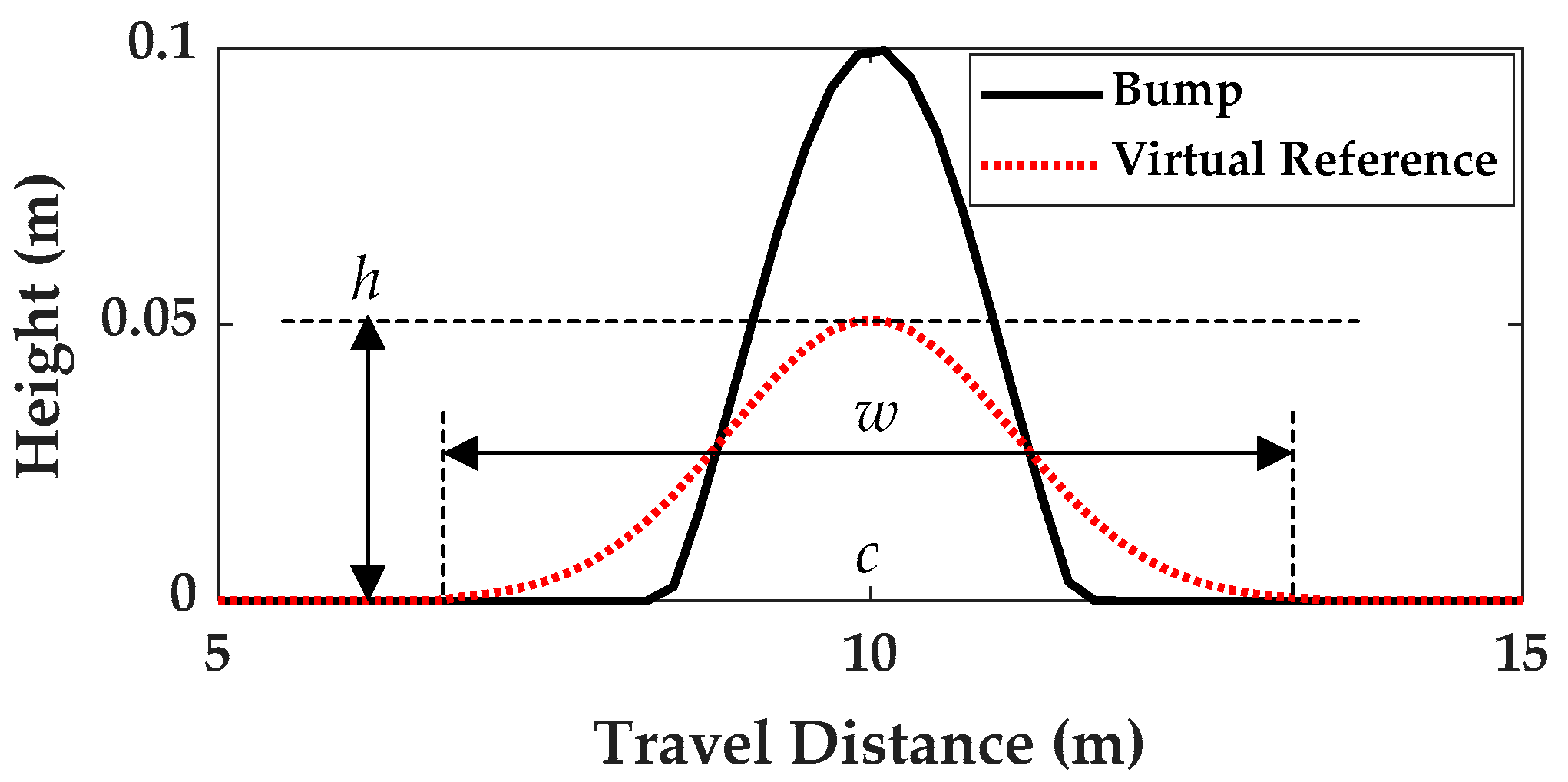

Figure 5 depicts the HSVD adopted in this paper. The HSVD is parameterized by three scalars—

h,

w, and

c—representing the height (amplitude), width (effective duration), and center position, respectively. The center position,

c, is anchored to the midpoint of the corresponding physical bump; consequently, if

c is included in the decision vector, it quantifies the phase offset from a true bump center. To maximize the performance of the preview controller, the HSVD parameters (

h,

w,

c) are optimized with respect to a particular performance criterion.

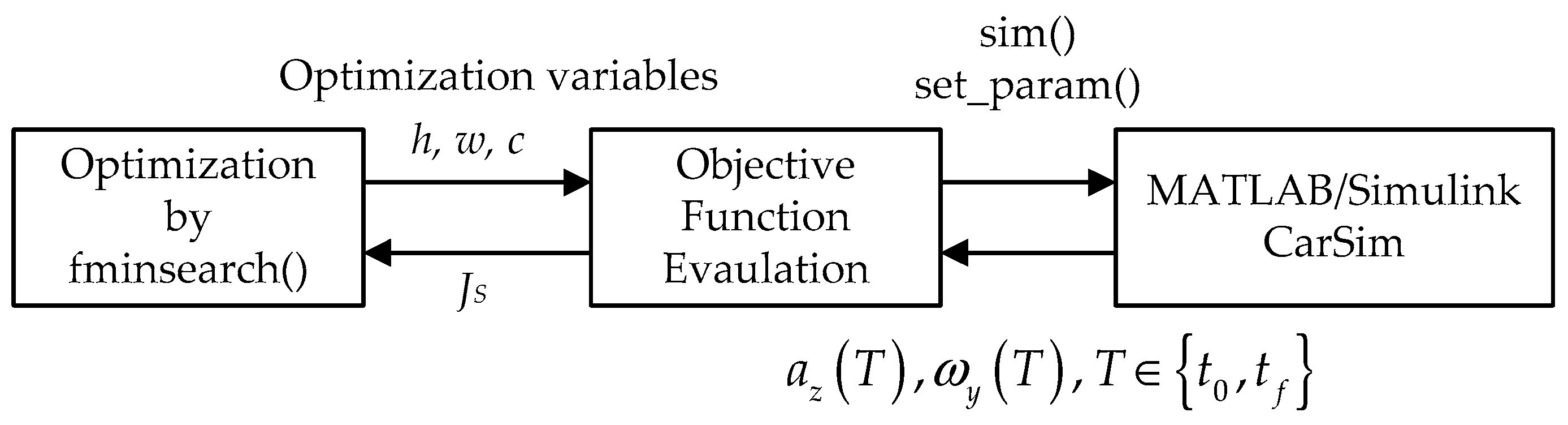

In this paper, a simulation-based optimization method (SBOM) is adopted to optimize the HSVD parameters [

26,

39]. To jointly address ride-comfort improvement and motion-sickness mitigation, the objective function of SBOM is defined in Equation (40) as a composite of

az and

ωy responses, evaluated over the simulation horizon

T on a co-simulation environment of MATLAB2019a/Simulink and CarSim8.0 [

26,

42]. In Equation (40), R2D denotes the radians-to-degrees conversion factor, and

α is a parameter used to tune the relative importance of

az to

ωy; in this paper,

α = 0.3. The derivative-free Nelder–Mead simplex algorithm, fminsearch(), provided in MATLAB, is selected as an optimizer for SBOM in this paper. The SBOM workflow is illustrated in

Figure 6. Once the HSVD parameters are optimized via SBOM, the resulting virtual disturbance replaces the physical bump signal in all subsequent simulations.

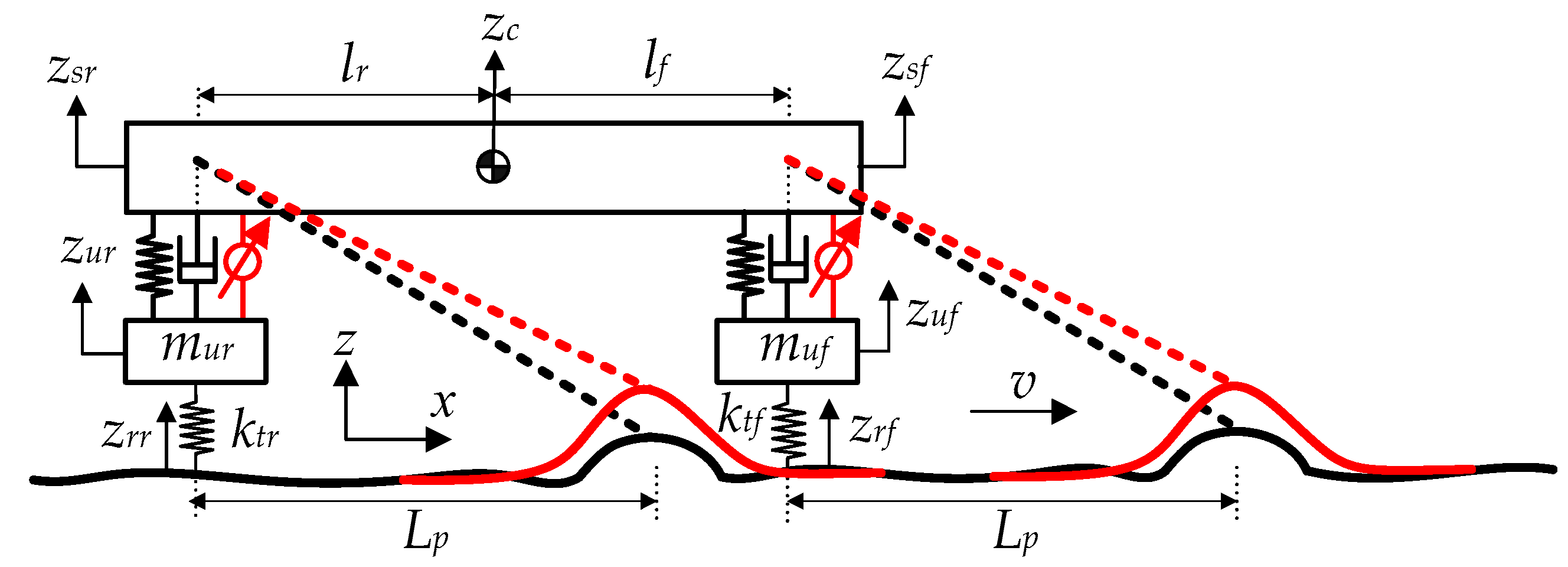

As summarized in

Table 1 and

Figure 3, preview controllers employing HPreview (i.e.,

KFFh) utilize a single set of previewed signals associated with one bump; consequently, a single HSVD, as shown with a red line in

Figure 3, is required, and its three parameters (

h,

w,

c) are optimized by SBOM. By contrast, as illustrated in

Figure 4, preview controllers employing QPreview (i.e.,

KFFQ) require two distinct preview signal sets for a single bump, since the rear suspension encounters a phase-shifted disturbance relative to the front. Accordingly, two—front/rear—HSVD profiles, as shown with red lines in

Figure 4, are introduced, yielding six decision variables (

hf,

wf,

cf,

hr,

wr,

cr) where subscripts,

f and

r, denote the front and rear axles, respectively. Noting that the wheelbase specifies the spatial offset between axles,

cr represents the deviation of the rear HSVD center from the wheelbase-aligned position.