Fabrication and Evaluation of Large Alumina Crucibles by Vat Photopolymerization Additive Manufacturing for High-Temperature Actinide Chemistry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

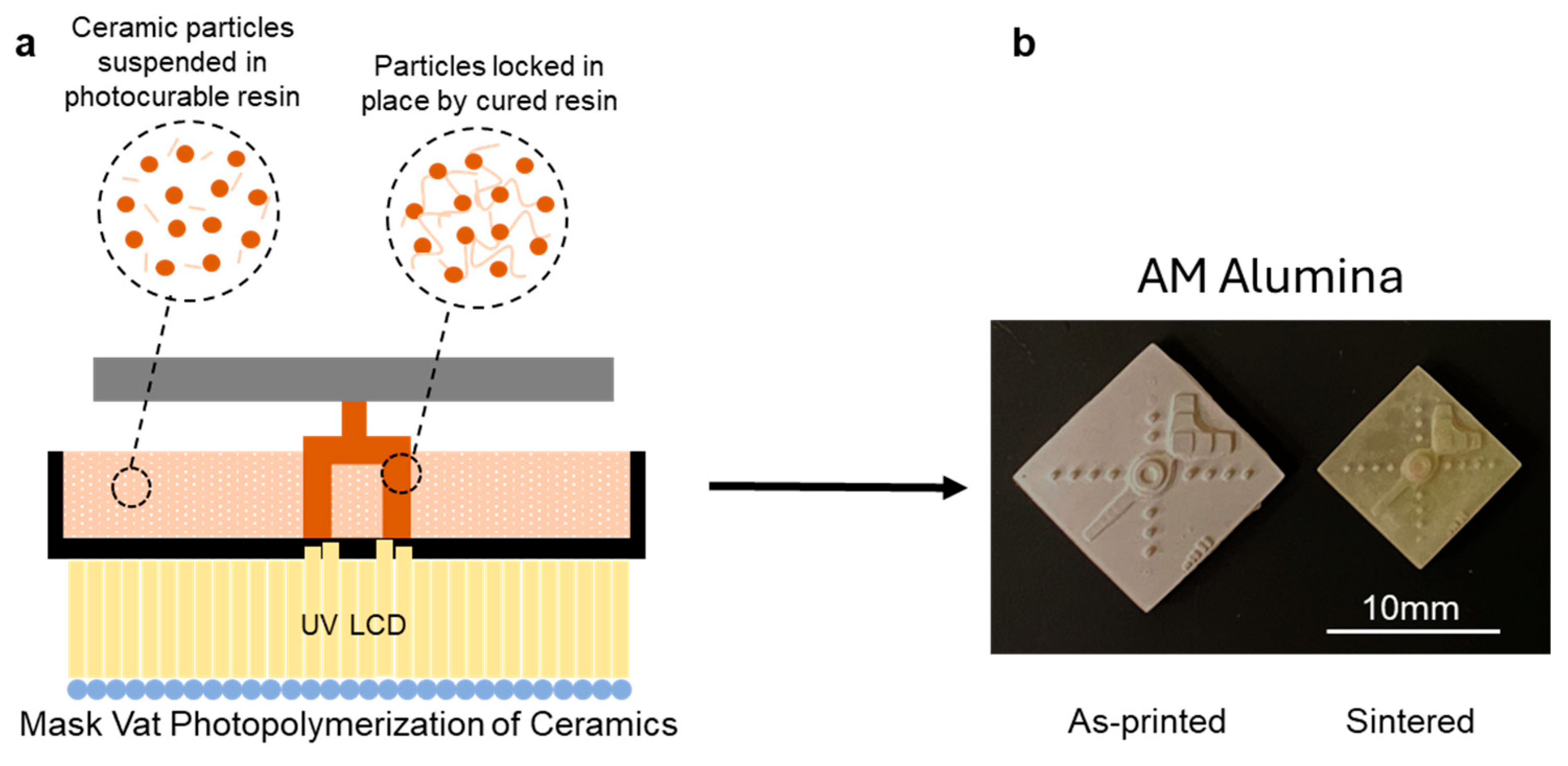

2.1. Ceramic Vat Photopolymerization

2.2. Characterization

3. Results

3.1. Additive Manufacturing Observations

3.2. Structure

3.3. Properties

3.4. Performance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- -

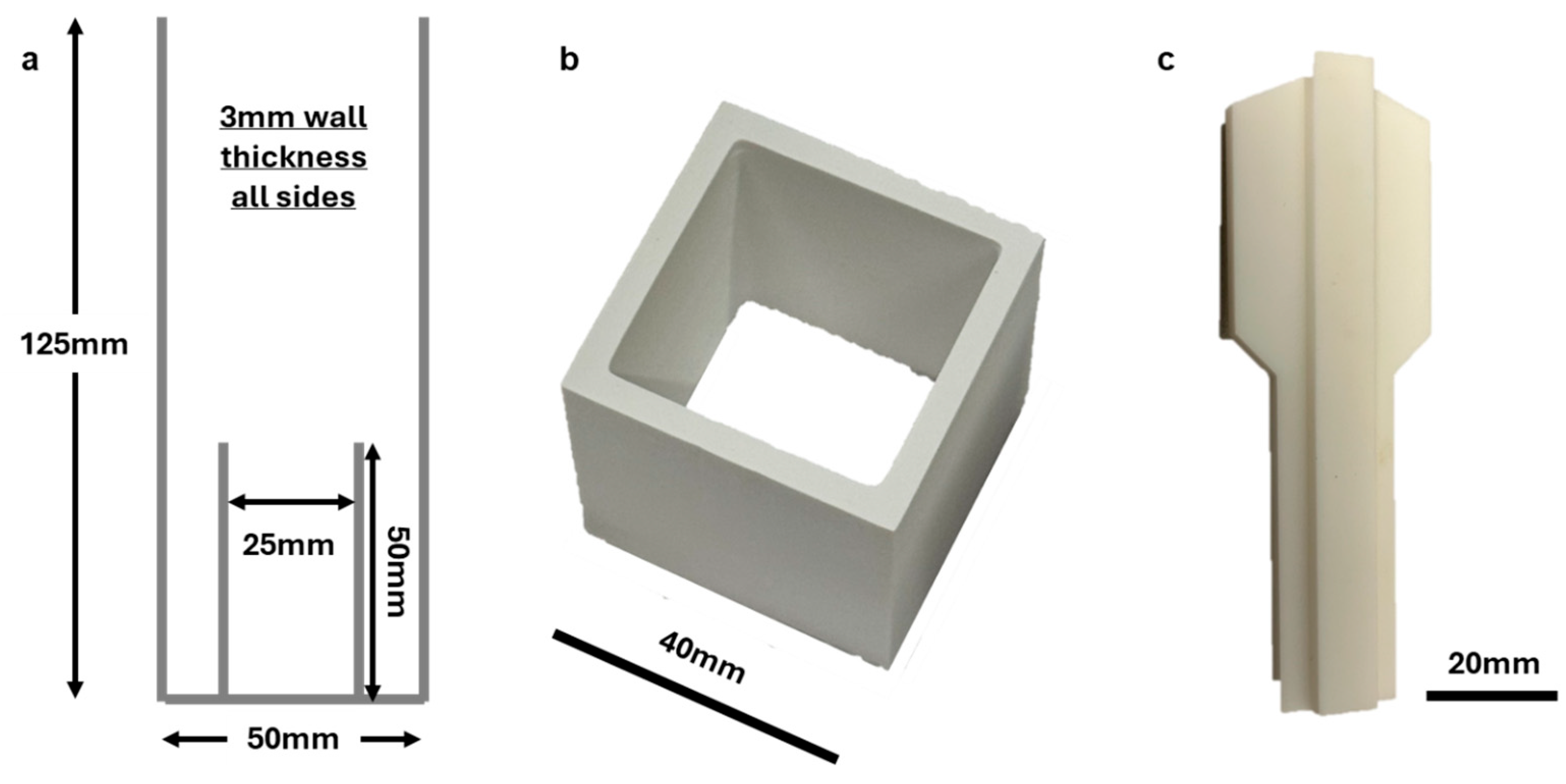

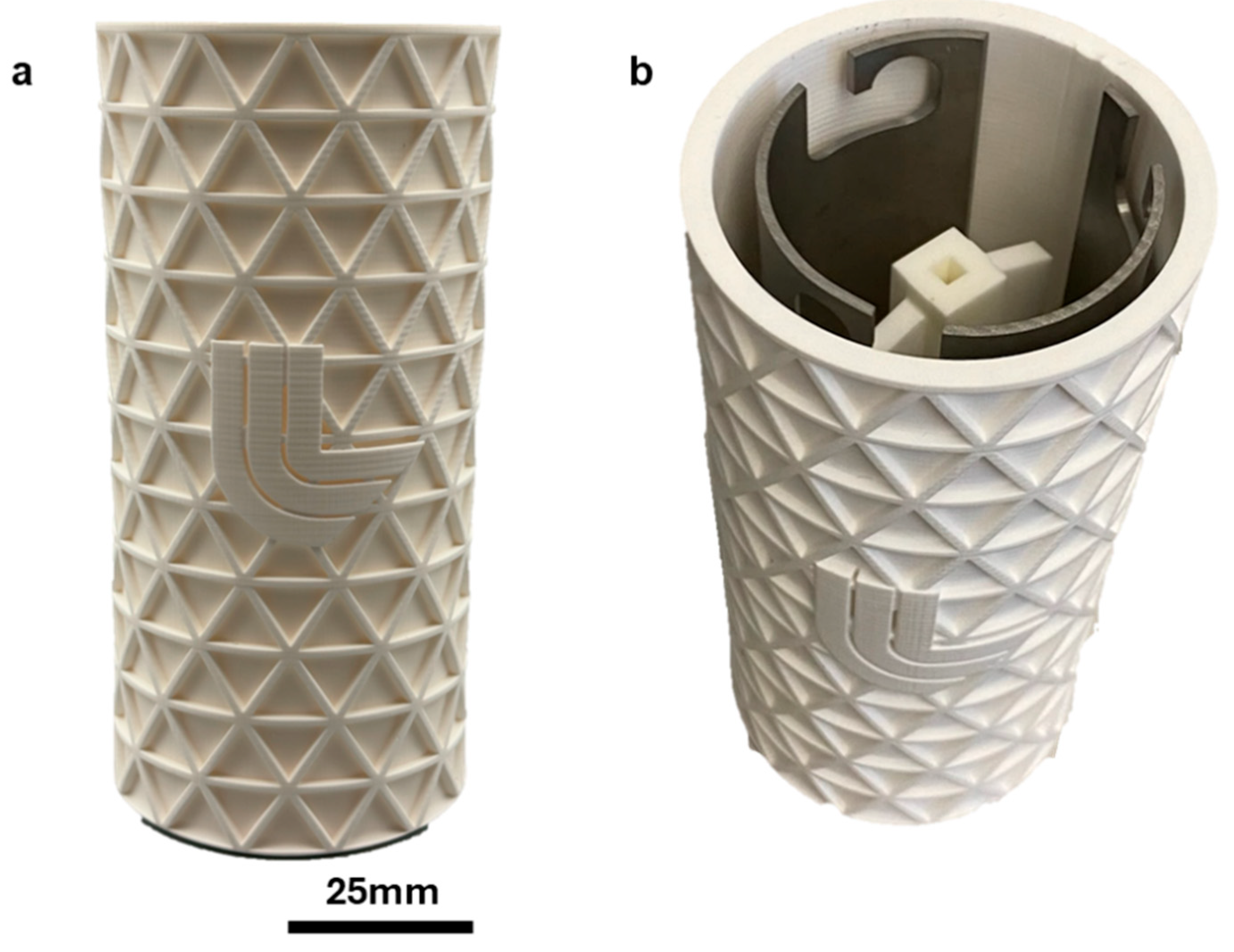

- New generations of photocurable resins were found to be compatible with consumer grade vat photopolymerization hardware, and produced functioning alumina ceramics at scales up to 125 mm in height.

- -

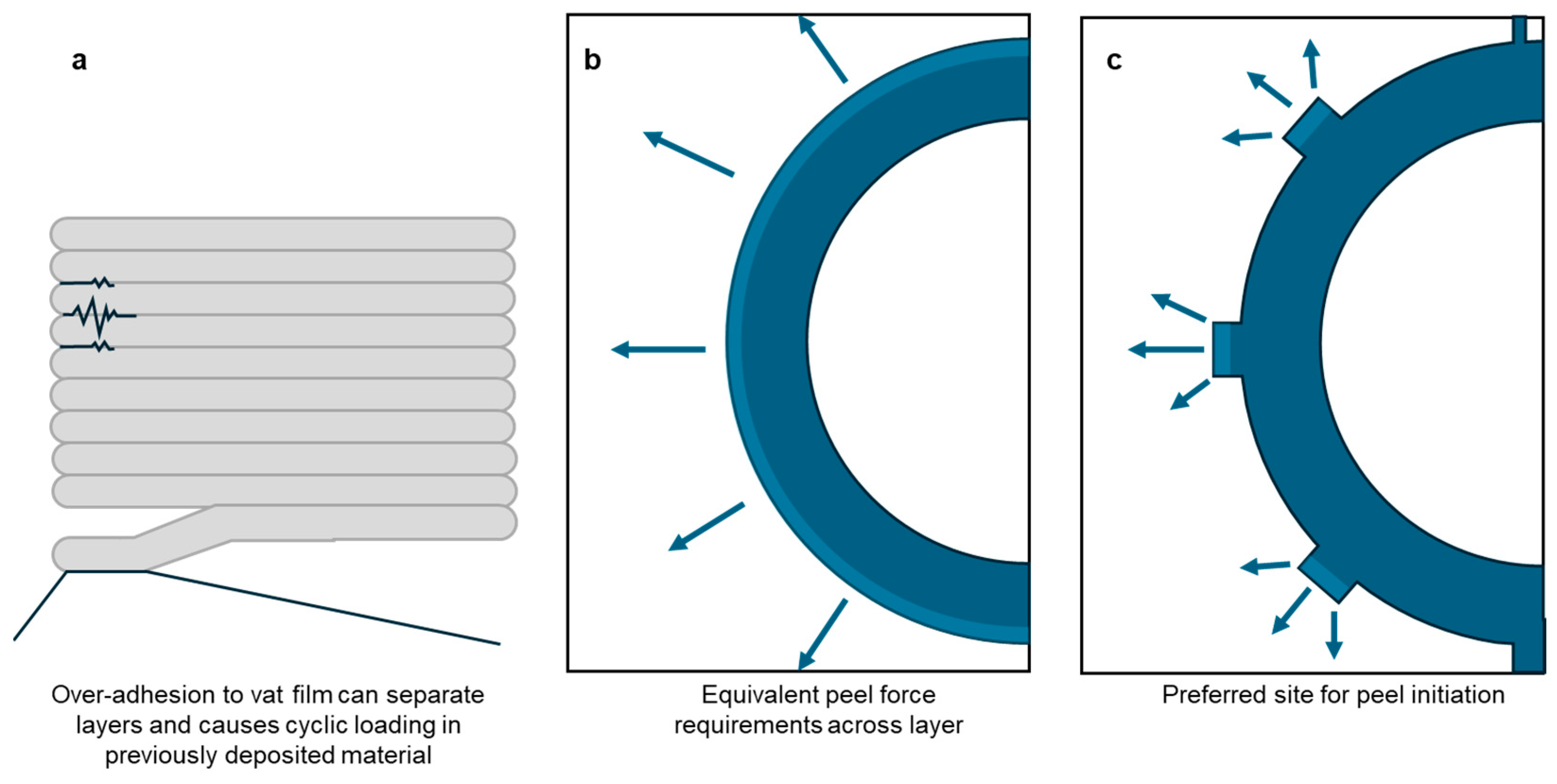

- These parts achieved high bulk densities (>95%), but had a high density of surface cavities and surface undulations attributed to poor interlayer bonding and artifacts of the vat photopolymerization process.

- -

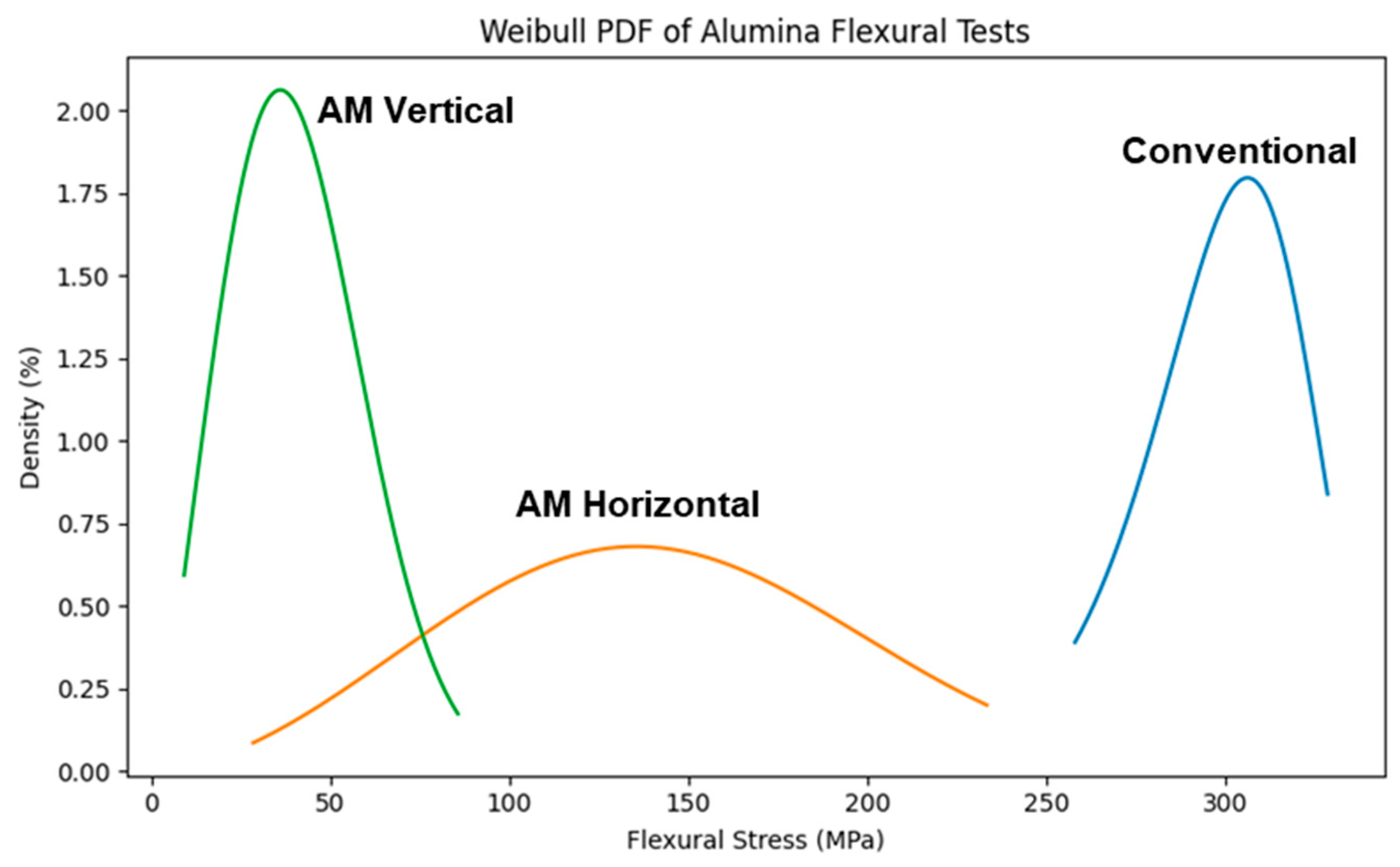

- The bending strength of these ceramics was low, ~50% of conventional alumina in-plane, and ~12% of conventional out-of-plane with the build direction. This low strength and anisotropy are attributed to artifacts of the additive manufacturing process.

- -

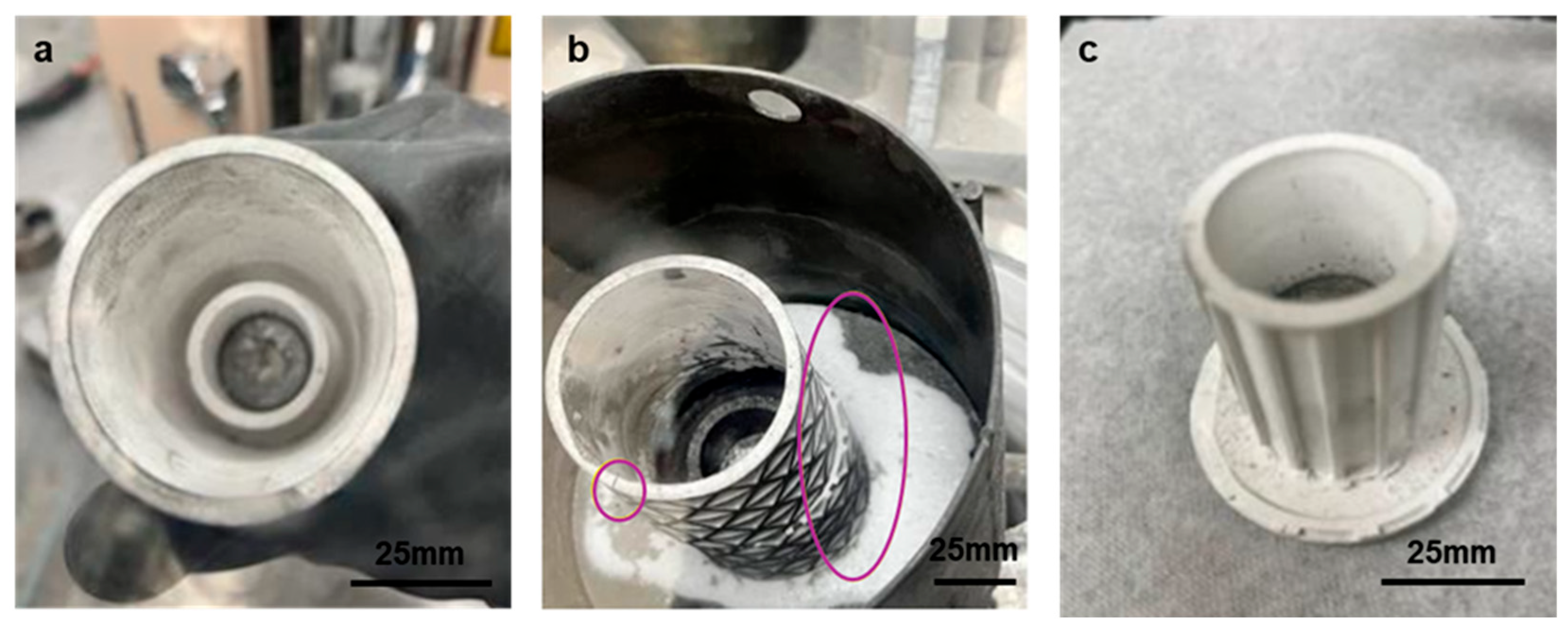

- Some crucibles were able to be used in electrorefining experiments, though others failed either during testing or due to thermal stresses. This is attributed to the lower strength or manufacturing defects, and can be improved with technique optimization.

- -

- There is significant opportunity for study of process and post-process optimization of ceramics produced using these consumer-grade tools, in particular due to their low upfront cost.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morrell, J.S.; Jackson, M.J. (Eds.) Uranium Processing and Properties; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morss, L.R.; Edelstein, N.M.; Fuger, J. The Chemistry of the Actinide and Transactinide Elements, 3rd ed.; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; Volumes 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Willit, J.L.; Miller, W.E.; Battles, J.E. Electrorefining of uranium and plutonium—A literature review. J. Nucl. Mater. 1992, 195, 229–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappleye, D.; McNeese, J.; Torres, R.; Holliday, K.; Jeffries, J.R. Development of small-scale plutonium electrorefining in molten CaCl2. J. Nucl. Mater. 2021, 552, 152968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibilaro, M.; Cassayre, L.; Lemoine, O.; Massot, L.; Dugne, O.; Malmbeck, R.; Chamelot, P. Direct electrochemical reduction of solid uranium oxide in molten fluoride salts. J. Nucl. Mater. 2011, 414, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, G.L.; Cao, G.; Gakhar, R.; Yoo, T.-S. Molten Salt Reactor Salt Processing—Technology Status; INL/EXT--18-51033-Rev000; Idaho National Laboratory (INL): Idaho Falls, ID, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serp, J.; Allibert, M.; Beneš, O.; Delpech, S.; Feynberg, O.; Ghetta, V.; Heuer, D.; Holcomb, D.; Ignatiev, V.; Kloosterman, J.L.; et al. The molten salt reactor (MSR) in generation IV: Overview and perspectives. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2014, 77, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphal, B.R.; Marsden, K.C.; Price, J.C. Development of a Ceramic-Lined Crucible for the Separation of Salt from Uranium. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2009, 40, 2861–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ch, J.R.; Vetrivendan, E.; Madhura, B.; Ningshen, S. A review of ceramic coatings for high temperature uranium melting applications. J. Nucl. Mater. 2020, 540, 152354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananthapadmanabhan, P.V.; Sreekumar, K.; Thiyagarajan, T.; Satpute, R.; Krishnan, K.; Kulkarni, N.; Kutty, T. Plasma spheroidization and high temperature stability of lanthanum phosphate and its compatibility with molten uranium. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2009, 113, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Cho, C.H.; Lee, Y.S.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, J.-G. Chemical reactivity of oxide materials with uranium and uranium trichloride. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2010, 27, 1786–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, D.; Luo, L.; Shen, S.; Niu, S.; Cai, S. Characterization of Mg–Y co-doped ZrO2/MgAl2O4 composite ceramic and the corrosion reaction in molten uranium. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2016, 310, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K.; Saify, M.T.; Majumdar, S.; Mollick, P.K. Interaction study of molten uranium with multilayer SiC/Y2O3 and Mo/Y2O3 coated graphite. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2023, 55, 1855–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.; Lee, H.-S.; Lee, S. Stability of plasma-sprayed TiN and ZrN coatings on graphite for application to uranium-melting crucibles for pyroprocessing. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2016, 310, 1173–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, E.D.; Brewer, L.; Bromley, L.A.; Gilles, P.W.; Lofgren, N.L. The Melting and Casting of Uranium in Sulfide Crucibles. Other Information: Decl. Mar. 6, 1957. Orig. Receipt Date: 31-DEC-58. Available online: https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc1020559/ (accessed on 21 December 2023).

- Rauch, H.A.; Cui, H.; Knight, K.P.; Griffiths, R.J.; Yoder, J.K.; Zheng, X.; Yu, H.Z. Additive manufacturing of yttrium-stabilized tetragonal zirconia: Progressive wall collapse, martensitic transformation, and energy dissipation in micro-honeycombs. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 52, 102692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayode Otitoju, T.; Ugochukwu Okoye, P.; Chen, G.; Li, Y.; Okoye, M.; Li, S. Advanced ceramic components: Materials, fabrication, and applications. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2020, 85, 34–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelz, J.S.; Ku, N.; Meyers, M.A.; Vargas-Gonzalez, L.R. Additive manufacturing of structural ceramics: A historical perspective. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 15, 670–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Miyanaji, H. Ceramic Additive Manufacturing: A Review of Current Status and Challenges. 2017. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2152/89871 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Travitzky, N.; Bonet, A.; Dermeik, B.; Fey, T.; Filbert-Demut, I.; Schlier, L.; Schlordt, T.; Greil, P. Additive Manufacturing of Ceramic-Based Materials. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2014, 16, 729–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakeri, S.; Vippola, M.; Levänen, E. A comprehensive review of the photopolymerization of ceramic resins used in stereolithography. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 35, 101177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halloran, J.W.; Griffith, M.L. Ultraviolet Curing of Highly Loaded Ceramic Suspensions for Stereolithography of Ceramics. 1994. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2152/68676 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Schwentenwein, M.; Homa, J. Additive Manufacturing of Dense Alumina Ceramics. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2015, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer-Fischer, E.; Abel, J.; Sieder-Katzmann, J.; Propst, M.; Bach, C.; Scheithauer, U.; Michaelis, A. Study on CerAMfacturing of Novel Alumina Aerospike Nozzles by Lithography-Based Ceramic Vat Photopolymerization (CerAM VPP). Materials 2022, 15, 3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “15” LCM-Printed Gas Distribution Ring for the Semiconductor Industry. Lithoz GmbH, Apr. 2025. Available online: https://www.lithoz.com/en/resources-lithoz/ (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Ghazanfari, A.; Li, W.; Leu, M.C.; Hilmas, G.E. A novel freeform extrusion fabrication process for producing solid ceramic components with uniform layered radiation drying. Addit. Manuf. 2017, 15, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Ren, X.; Ma, C.; Pei, Z. Binder Jetting Additive Manufacturing of Ceramics: A Literature Review. Presented at the ASME 2017 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition, Tampa, FL, USA, 3–9 November 2017; American Society of Mechanical Engineers Digital Collection: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C1161-18; Standard Test Method for Flexural Strength of Advanced Ceramics at Ambient Temperature. ASTM International: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Pagac, M.; Hajnys, J.; Ma, Q.-P.; Jancar, L.; Jansa, J.; Stefek, P.; Mesicek, J. A Review of Vat Photopolymerization Technology: Materials, Applications, Challenges, and Future Trends of 3D Printing. Polymers 2021, 13, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Zhu, L.; Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Shi, J.; Tang, W.; Li, N.; Yang, J. The recent development of vat photopolymerization: A review. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 48, 102423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stumpf, A.S.G.; Bergmann, C.P.; Vicenzi, J.; Fetter, R.; Mundstock, K.S. Mechanical behavior of alumina and alumina-feldspar based ceramics in an acetic acid (4%) environment. Mater. Des. 2009, 30, 4348–4359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staudacher, M.; Lube, T.; Glettler, J.; Scheithauer, U.; Schwentenwein, M. A novel test specimen for strength testing of ceramics for additive manufacturing. Open Ceram. 2023, 15, 100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuchukwu, O.A.; Salihi, A.; Ibrahim, A.; Audu, A.A.; Makoyo, M.; Mohammed, S.A.; Lawal, M.Y.; Etinosa, P.O.; Isaac, I.O.; Oni, P.G.; et al. Weibull analysis of ceramics and related materials: A review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Teng, J.; Ji, X.; Xu, C.; Ma, D.; Sui, S.; Zhang, Z. Research progress of the defects and innovations of ceramic vat photopolymerization. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 65, 103441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Wei, Y.; Lu, Z.; Wan, L.; Li, P. Design of a Shaping System for Stereolithography with High Solid Loading Ceramic Suspensions. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 5, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paral, S.K.; Lin, D.-Z.; Cheng, Y.-L.; Lin, S.-C.; Jeng, J.-Y. A Review of Critical Issues in High-Speed Vat Photopolymerization. Polymers 2023, 15, 2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitteramskogler, G.; Gmeiner, R.; Felzmann, R.; Gruber, S.; Hofstetter, C.; Stampfl, J.; Ebert, J.; Wachter, W.; Laubersheimer, J. Light curing strategies for lithography-based additive manufacturing of customized ceramics. Addit. Manuf. 2014, 1–4, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; He, R.; Ding, G.; Bai, X.; Fang, D. Effects of fine grains and sintering additives on stereolithography additive manufactured Al2O3 ceramic. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 2303–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirihara, S. Systematic Compounding of Ceramic Pastes in Stereolithographic Additive Manufacturing. Materials 2021, 14, 7090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Hu, B.; Li, R.; Sun, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, P.; Cai, P.; Bai, J. Enhancing mechanical integrity of vat photopolymerization 3D printed hydroxyapatite scaffolds through overcoming peeling defects. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 44, 116642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-H.; Jeyaprakash, N.; Yang, C.-H. Material characterization and defect detection of additively manufactured ceramic teeth using non-destructive techniques. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 7017–7031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z. Review of non-destructive testing methods for defect detection of ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 4389–4397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, Q.; Moghadasi, M.; Pei, Z.; Ma, C. Dense and strong ceramic composites via binder jetting and spontaneous infiltration. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49 Pt A, 17363–17370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsutsumi, C.; Okano, K.; Suto, T. High quality machining of ceramics. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 1993, 37, 639–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharathi, V.; Anilchandra, A.R.; Sangam, S.S.; Shreyas, S.; Shankar, S.B. A review on the challenges in machining of ceramics. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 46, 1451–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Width | Height | Support Length | Load Span | Loading Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 mm | 1.5 mm | 20 mm | 10 mm | 0.2 mm/min |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Griffiths, R.J.; Santoyo, C.; Forien, J.-B.; Childs, B.; Swift, A.J.; Cho, A.; Wilson-Heid, A.; Ankrah, G.; Rappleye, D.; Martin, A.A.; et al. Fabrication and Evaluation of Large Alumina Crucibles by Vat Photopolymerization Additive Manufacturing for High-Temperature Actinide Chemistry. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12742. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312742

Griffiths RJ, Santoyo C, Forien J-B, Childs B, Swift AJ, Cho A, Wilson-Heid A, Ankrah G, Rappleye D, Martin AA, et al. Fabrication and Evaluation of Large Alumina Crucibles by Vat Photopolymerization Additive Manufacturing for High-Temperature Actinide Chemistry. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12742. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312742

Chicago/Turabian StyleGriffiths, R. Joey, Christy Santoyo, Jean-Baptiste Forien, Bradley Childs, Andrew J. Swift, Andrew Cho, Alexander Wilson-Heid, George Ankrah, Devin Rappleye, Aiden A. Martin, and et al. 2025. "Fabrication and Evaluation of Large Alumina Crucibles by Vat Photopolymerization Additive Manufacturing for High-Temperature Actinide Chemistry" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12742. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312742

APA StyleGriffiths, R. J., Santoyo, C., Forien, J.-B., Childs, B., Swift, A. J., Cho, A., Wilson-Heid, A., Ankrah, G., Rappleye, D., Martin, A. A., Jeffries, J., & Holliday, K. (2025). Fabrication and Evaluation of Large Alumina Crucibles by Vat Photopolymerization Additive Manufacturing for High-Temperature Actinide Chemistry. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12742. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312742