Heat Treatment of Tomato Increases cis-Lycopene Conversion and Enhances Antioxidant Activity in HepG2 Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Preparation of Heat-Treated Tomato Homogenates

Hexane Extract

2.3. Lycopene Content

2.4. DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

2.5. ABTS Radical Scavenging Activity

2.6. Cell Culture

2.7. Cytoprotective Effect

2.8. Intracellular Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Measurement

2.9. Glutathione Reductase (GR) and Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx) Activity

2.10. Total Glutathione and Reduced Glutathione/Oxidized Glutathione (GSH/GSSG) Ratio

2.11. Western Blot Analysis

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

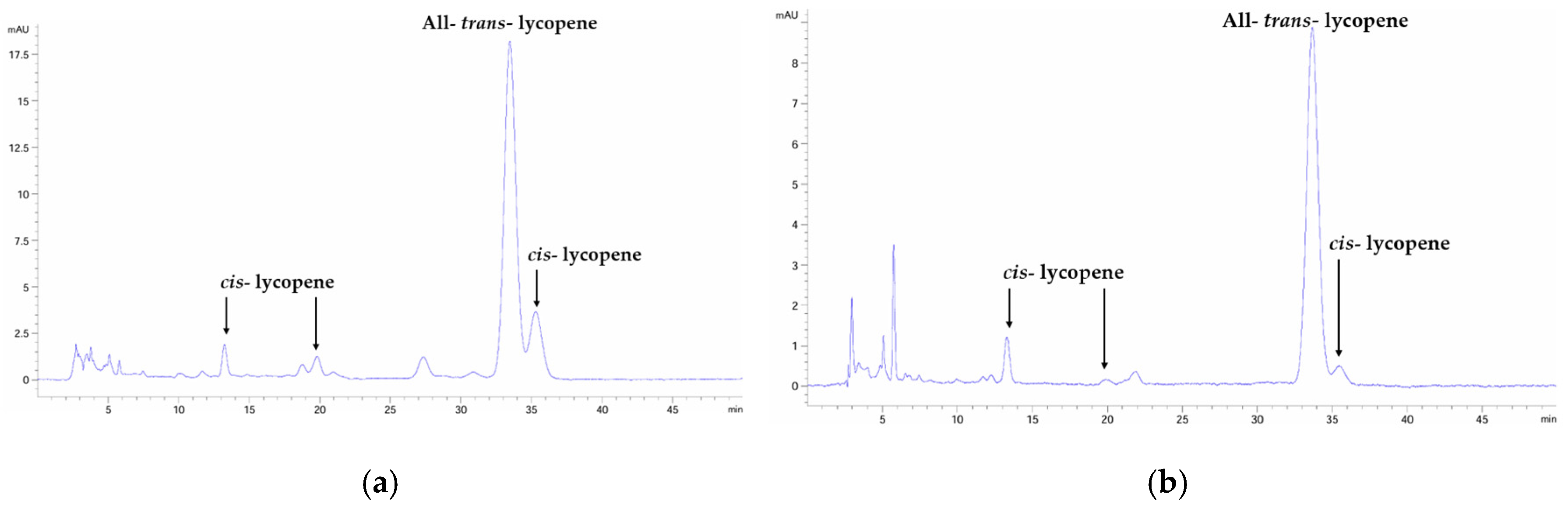

3.1. Heat Processing Increased cis-Isomer Lycopene Content in Tomato Hexane Extracts

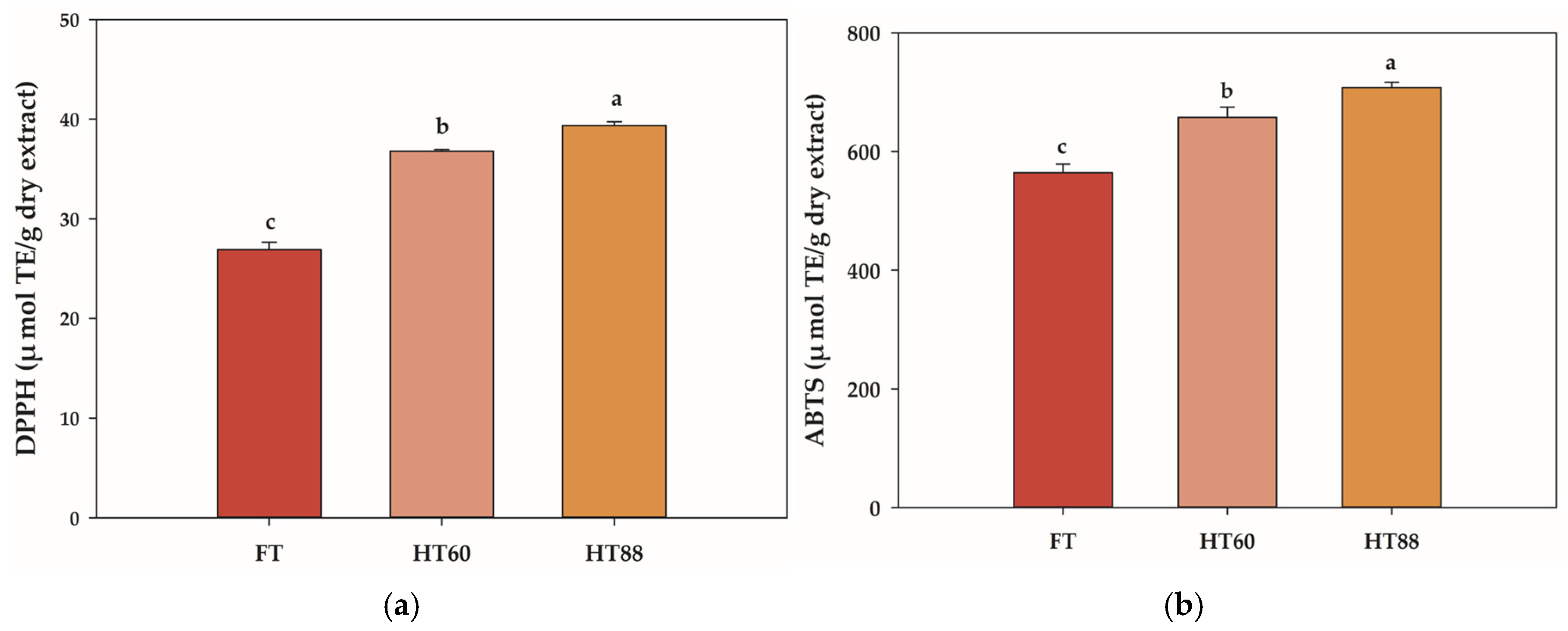

3.2. Heat Processing Increased Chemical Antioxidant Activity

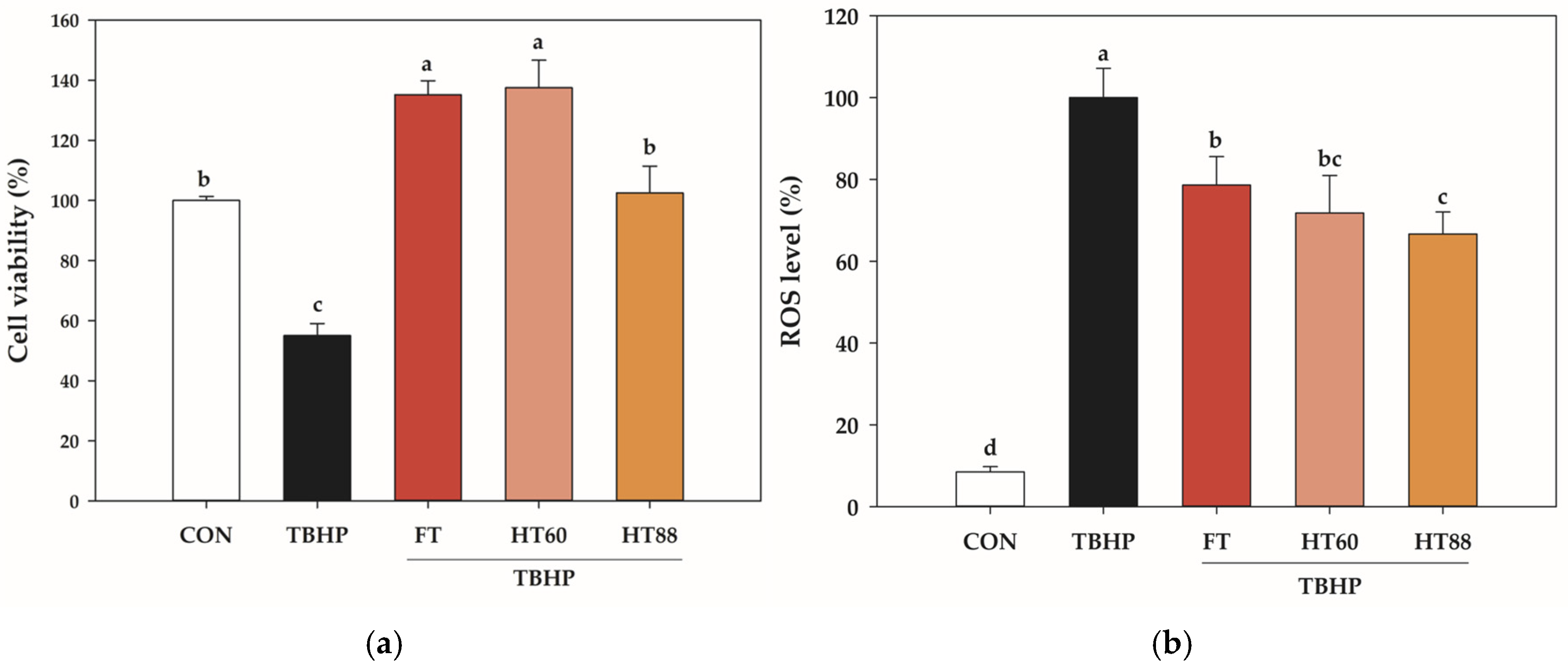

3.3. Heated Tomato Hexane Extracts Improve Cell Viability and Attenuate Intracellular ROS

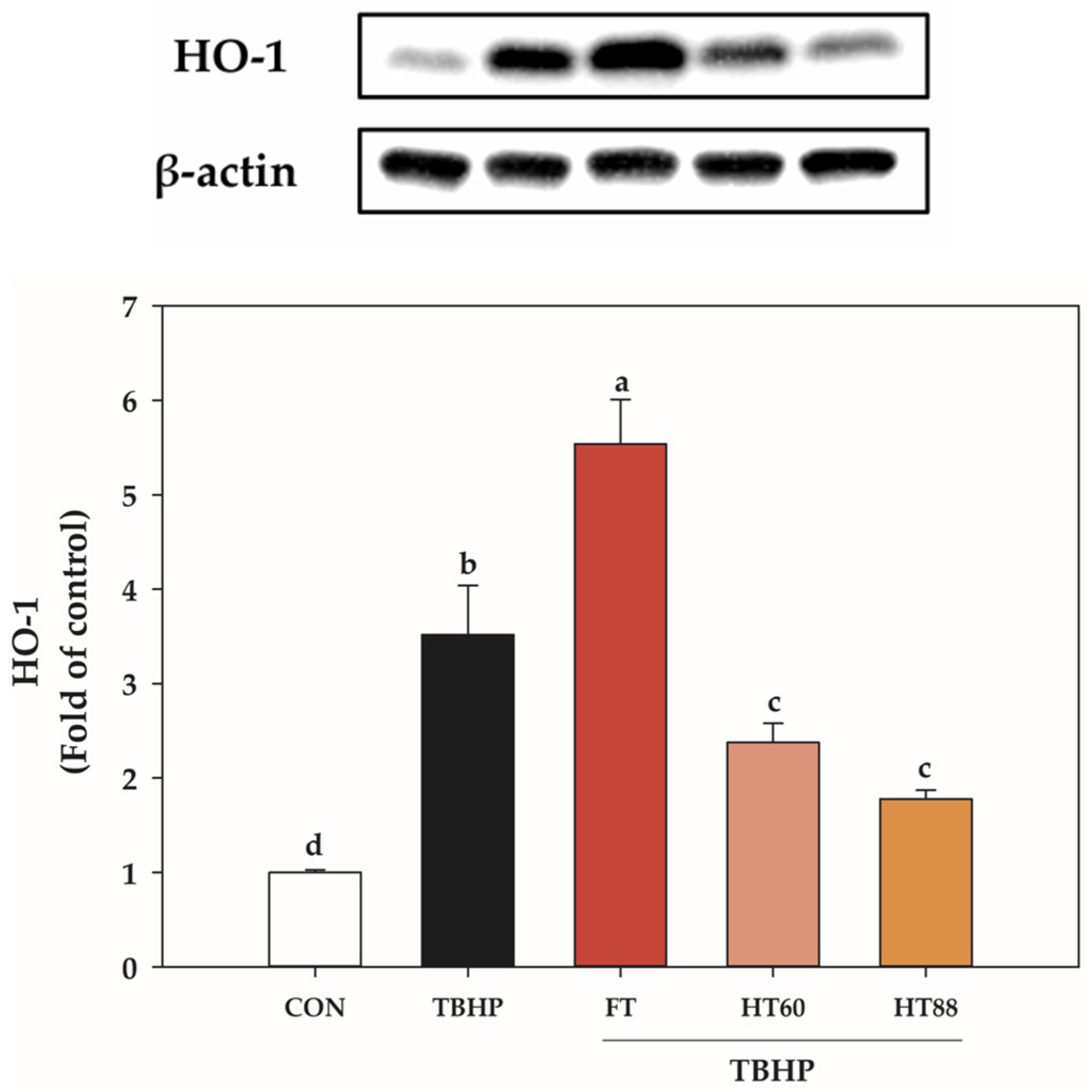

3.4. Heat-Processed Tomato Hexane Extracts Attenuate HO-1 Induction

3.5. Heated Tomato Hexane Extracts Alter Glutathione Redox Status

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agarwal, S.; Rao, A.V. Tomato lycopene and its role in human health and chronic diseases. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2000, 163, 739–744. [Google Scholar]

- Story, E.N.; Kopec, R.E.; Schwager, S.J.; Harrison, G.K. An update on the health effects of tomato lycopene. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 1, 189–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin-Jumah, M.; Nadeem, M.; Gilani, S.; Mubeen, B.; Ullah, I.; Alzarea, S.I.; Ghoneim, M.; Alshehri, S.; Al-Abbasi, F.; Kazmi, I. Lycopene: A natural arsenal in the war against oxidative stress and cardiovascular diseases. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulawik, A.; Cielecka-Piontek, J.; Zalewski, P. The importance of antioxidant activity for the health-promoting effect of lycopene. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mascio, P.; Kaiser, S.; Sies, H. Lycopene as the most efficient biological carotenoid singlet oxygen quencher. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1989, 274, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Ghorat, F.; Ul-Haq, I.; Ur-Rehman, H.; Gondal, T.A.; Suleria, H.A.R.; Imran, A. Lycopene as a natural antioxidant used to prevent human health disorders. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honest, K.N.; Zhang, H.W.; Zhang, L. Lycopene: Isomerization effects on bioavailability and bioactivity properties. Food Rev. Int. 2011, 27, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boileau, A.C.; Merchen, N.R.; Wasson, K.; Atkinson, C.A.; Erdman, J.W., Jr. Cis-lycopene is more bioavailable than trans-lycopene in vitro and in vivo in lymph-cannulated ferrets. J. Nutr. 1999, 129, 1176–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boileau, T.W.; Boileau, A.C.; Erdman, J.W., Jr. Bioavailability of all-trans and cis-isomers of lycopene. Exp. Biol. Med. 2002, 227, 914–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, V.; Puspitasari-Nienaber, N.L.; Ferruzzi, M.G.; Schwartz, S.J. Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity of different geometrical isomers of α-carotene, β-carotene, lycopene, and zeaxanthin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmens, L.; Colle, I.; Van Buggenhout, S.; Palmero, P.; Van Loey, A.; Hendrickx, M. Carotenoid bioaccessibility in fruit- and vegetable-based food products as affected by product (micro)structural characteristics and the presence of lipids: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 38, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svelander, C.A.; Tibäck, E.A.; Ahrné, L.M.; Langton, M.I.; Svanberg, U.S.; Alminger, M.A. Processing of tomato: Impact on in vitro bioaccessibility of lycopene and textural properties. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010, 90, 1665–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Yu, L.; Pehrsson, P.R. Are processed tomato products as nutritious as fresh tomatoes? Scoping review on the effects of industrial processing on nutrients and bioactive compounds in tomatoes. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, M. Application of E/Z-isomerization technology for enhancing processing efficiency, health-promoting effects, and usability of carotenoids: A review and future perspectives. J. Oleo Sci. 2022, 71, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, R.K.; Bekhit, A.E.-D.A.; Roohinejad, S.; Rengasamy, K.R.R.; Keum, Y.-S. Chemical stability of lycopene in processed products: A review of the effects of processing methods and modern preservation strategies. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 712–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelebek, H.; Selli, S.; Kadiroğlu Kelebek, P.; Çetiner, B. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant potential in tomato pastes as affected by hot and cold break process. Food Chem. 2017, 220, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Lin, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, A.; Bian, H.; Zhang, W.; Wu, Z. Antioxidant, anticancer activity and molecular docking study of lycopene with different ratios of Z-isomers. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 6, 100455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Dor, A.; Steiner, M.; Gheber, L.; Danilenko, M.; Dubi, N.; Linnewiel, K.; Zick, A.; Sharoni, Y.; Levy, J. Carotenoids activate the antioxidant response element transcription system. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2005, 4, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, W.; Sies, H. Antioxidant activity of carotenoids. Mol. Asp. Med. 2003, 24, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lim, J.W.; Kim, H. Lycopene inhibits IL-6 expression by upregulating NQO1 and HO-1 via activation of Nrf2 in ethanol/lipopolysaccharide-stimulated pancreatic acinar cells. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Maguer, M.L.; Kakuda, Y.; Liptay, A.; Niekamp, F. Effect of heating and exposure to light on the stability of lycopene in tomato purée. Food Control 2008, 19, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Joseph, J.A. Quantifying cellular oxidative stress by dichlorofluorescein assay using microplate reader. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 27, 612–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.-K.; Jang, H.-D. Nrf2-mediated HO-1 induction coupled with the ERK signaling pathway contributes to indirect antioxidant capacity of caffeic acid phenethyl ester in HepG2 cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 12149–12165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobwala, S.; Khayyat, A.; Fan, W.; Ercal, N. Comparative evaluation of N-acetylcysteine and N-acetylcysteineamide in acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in human hepatoma HepaRG cells. Exp. Biol. Med. 2015, 240, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.K.; Krohn, R.I.; Hermanson, G.T.; Mallia, A.K.; Gartner, F.H.; Provenzano, M.D.; Fujimoto, E.K.; Goeke, N.M.; Olson, B.J.; Klenk, D.C. Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal. Biochem. 1985, 150, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, K.; Hruškar, M.; Vahčić, N. Lycopene content of tomato products and their contribution to the lycopene intake of Croatians. Nutr. Res. 2006, 26, 556–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colle, I.J.P.; Lemmens, L.; Van Buggenhout, S.; Van Loey, A.M.; Hendrickx, M.E. Effect of thermal processing on the degradation, isomerization and bioaccessibility of lycopene in tomato pulp. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, C753–C759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arballo, J.; Amengual, J.; Erdman, J.W., Jr. Lycopene: A critical review of digestion, absorption, metabolism, and excretion. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooperstone, J.L.; Ralston, R.A.; Riedl, K.M.; Haufe, T.C.; Schweiggert, R.M.; King, S.A.; Timmers, C.D.; Francis, D.M.; Lesinski, G.B.; Schwartz, S.J. Enhanced bioavailability of lycopene when consumed as cis-isomers from tangerine compared to red tomato juice, a randomized, cross-over clinical trial. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2015, 59, 658–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unlu, N.Z.; Bohn, T.; Clinton, S.K.; Schwartz, S.J. Carotenoid absorption from salad and salsa by humans is enhanced by the addition of avocado or avocado oil. J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phan-Thi, H.; Waché, Y. Isomerization and increase in the antioxidant properties of lycopene from Momordica cochinchinensis (Gac) by moderate heat treatment with UV–Vis spectra as a marker. Food Chem. 2014, 156, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narra, F.; Brigante, F.I.; Piragine, E.; Solovyev, P.; Benedetti, G.; Araniti, F.; Bontempo, L.; Ceccanti, C.; Martelli, A.; Guidi, L. The effect of thermal processes on the organoleptic and nutraceutical quality of tomato fruit (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Foods 2024, 13, 3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, K.; Honda, M.; Takemura, R.; Fukaya, T.; Kubota, M.; Kanda, H.; Goto, M. The thermal Z-isomerization-induced change in solubility and physical properties of (all-E)-lycopene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 491, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alía, M.; Ramos, S.; Mateos, R.; Bravo, L.; Goya, L. Response of the antioxidant defense system to tert-butyl hydroperoxide and hydrogen peroxide in a human hepatoma cell line (HepG2). J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2005, 19, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, C.; Lyden, E.; Furtado, J.; Van Ormer, M.; White, K.; Overby, N.; Anderson-Berry, A. Serum lycopene concentrations and associations with clinical outcomes in a cohort of maternal–infant dyads. Nutrients 2018, 10, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayne, S.T.; Cartmel, B.; Silva, F.; Kim, C.S.; Fallon, B.G.; Briskin, K.; Goodwin, W.J., Jr. Plasma lycopene concentrations in humans are determined by lycopene intake, plasma cholesterol concentrations, and selected demographic factors. J. Nutr. 1999, 129, 849–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, L.; Ryan, L.; O’Brien, N. Comparison of the uptake and secretion of carotene and xanthophyll carotenoids by Caco-2 intestinal cells. Br. J. Nutr. 2007, 98, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Failla, M.L.; Chitchumroonchokchai, C.; Ishida, B.K. In vitro micellarization and intestinal cell uptake of cis isomers of lycopene exceed those of all-trans lycopene. J. Nutr. 2008, 138, 482–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannat, S.; Ali, M.Y.; Kim, H.-R.; Jung, H.A.; Choi, J.S. Protective effects of sweet orange, unshiu mikan, and mini tomato juice powders on t-BHP-induced oxidative stress in HepG2 cells. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2016, 21, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reshmitha, T.; Nisha, P. Lycopene mitigates acrylamide- and glycidamide-induced cellular toxicity via oxidative stress modulation in HepG2 cells. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 80, 104390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abushita, A.A.; Hebshi, E.A.; Daood, H.G.; Biacs, P.A. Determination of antioxidant vitamins in tomatoes. Food Chem. 1997, 71, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raiola, A.; Rigano, M.M.; Calafiore, R.; Frusciante, L.; Barone, A. Enhancing the health-promoting effects of tomato fruit for biofortified food. Mediat. Inflamm. 2014, 2014, 139873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soupas, L.; Huikko, L.; Lampi, A.M.; Piironen, V. Oxidative stability of phytosterols in some food applications. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2006, 222, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koschutnig, K.; Heikkinen, S.; Kemmo, S.; Lampi, A.-M.; Piironen, V.; Wagner, K.-H. Cytotoxic and apoptotic effects of single and mixed oxides of β-sitosterol on HepG2 cells. Toxicol. Vitr. 2009, 23, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryter, S.W.; Alam, J.; Choi, A.M.K. Heme oxygenase-1/carbon monoxide: From basic science to therapeutic applications. Physiol. Rev. 2006, 86, 583–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, J.; Stewart, D.; Touchard, C.; Boinapally, S.; Choi, A.M.K.; Cook, J.L. Nrf2, a Cap‘n’collar transcription factor, regulates induction of the heme oxygenase-1 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 26071–26078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-M.; Huang, S.-M.; Liu, C.-L.; Hu, M.-L. Apo-8′-lycopenal induces expression of HO-1 and NQO-1 via the ERK/p38–Nrf2–ARE pathway in human HepG2 cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 1576–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.H.; Hazell, A.S. N-acetylcysteine attenuates early induction of heme oxygenase-1 following traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 2005, 1033, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, L.; Sevanian, A. OxLDL induces macrophage γ-GCS-HS protein expression: A role for OxLDL-associated lipid hydroperoxide in GSH Synthesis. J. Lipid Res. 2001, 42, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Lupton, J.R.; Turner, N.D.; Fang, Y.-Z.; Yang, S. Glutathione metabolism and its implications for health. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 489–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J.D.; Flanagan, J.U.; Jowsey, I.R. Glutathione transferases. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2005, 45, 51–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirrlinger, J.; König, J.; Keppler, D.; Lindenau, J.; Schulz, J.B.; Dringen, R. The multidrug resistance protein MRP1 mediates the release of glutathione disulfide from rat astrocytes during oxidative stress. J. Neurochem. 2001, 76, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.P.C.; Deeley, R.G. Transport of glutathione and glutathione conjugates by MRP1. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2006, 27, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, H.J.; Zhang, H.; Rinna, A. Glutathione: Overview of its protective roles, measurement, and biosynthesis. Mol. Asp. Med. 2009, 30, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| FT | HT60 | HT88 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All-trans lycopene (mg/100 g) | 6.37 ± 0.54 b | 11.88 ± 0.93 a | 9.52 ± 2.46 ab |

| cis-lycopene (mg/100 g) | 3.72 ± 0.19 c | 4.41 ± 0.13 b | 4.91 ± 0.21 a |

| Total lycopene (mg/100 g) | 10.09 ± 0.72 b | 16.29 ± 1.06 a | 14.43 ± 2.67 a |

| CON | t-BHP | FT | HT60 | HT88 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSH (μM) | 8.85 ± 1.96 ab | 10.32 ± 1.68 a | 9.23 ± 0.89 ab | 7.35 ± 0.55 bc | 5.55 ± 0.69 c |

| Total glutathione (μM) | 9.67 ± 2.04 ab | 11.64 ± 2.04 a | 10.12 ± 0.74 ab | 8.30 ± 0.53 bc | 5.96 ± 0.61 c |

| GSH/GSSG | 21.49 ± 2.85 a | 16.59 ± 4.63 a | 21.44 ± 6.16 a | 15.43 ± 1.47 a | 28.57 ± 9.73 a |

| CON | t-BHP | FT | HT60 | HT88 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPx activity (nmol/min/mL) | 12.76 ± 1.12 a | 12.76 ± 0.51 a | 12.31 ± 1.40 a | 12.88 ± 0.42 a | 13.19 ± 0.98 a |

| GR activity (nmol/min/mL) | 57.48 ± 2.18 b | 56.61 ± 2.27 b | 62.47 ± 3.37 ab | 60.31 ± 4.86 ab | 66.64 ± 4.72 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, M.; Imm, J.-Y. Heat Treatment of Tomato Increases cis-Lycopene Conversion and Enhances Antioxidant Activity in HepG2 Cells. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12693. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312693

Kim M, Imm J-Y. Heat Treatment of Tomato Increases cis-Lycopene Conversion and Enhances Antioxidant Activity in HepG2 Cells. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12693. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312693

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Miseong, and Jee-Young Imm. 2025. "Heat Treatment of Tomato Increases cis-Lycopene Conversion and Enhances Antioxidant Activity in HepG2 Cells" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12693. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312693

APA StyleKim, M., & Imm, J.-Y. (2025). Heat Treatment of Tomato Increases cis-Lycopene Conversion and Enhances Antioxidant Activity in HepG2 Cells. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12693. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312693