1. Introduction

The use of new technologies to improve quality of life is becoming increasingly important, especially with the advent of the Internet of Things (IoT) and the sixth generation (6G) and beyond communication networks [

1,

2]. These networks can be used in domains such as intelligent transportation systems (ITSs), agriculture, aquaponics, hydroponics, smart health, and many more. In this regard, we focus on the smart health applications in this article. Smart health applications are context-aware healthcare systems that aim to improve the healthcare of users using new technologies related to IoT and 6G networks [

3,

4]. Cloud computing (CC) was previously considered as a backup solution to improve the performance of such applications; unfortunately, it has been stated in the literature that the use of CC presents many challenges such as end-to-end delays, latency, and bandwidth management problems [

5]. To address these problems with CC, mobile edge computing (MEC) has been proposed. MEC is an extension of cloud computing that brings computing, storage, and networking capabilities to the edge of the network closer to end users [

6]. The technology was developed to meet the growing need for real-time data processing, particularly in mobile communications. MEC is considered a key enabler technology for 6G. It allows telecommunication operators to offer innovative services such as augmented reality, autonomous vehicles, healthcare, and smart cities [

6].

MEC is a natural evolution of cloud computing, designed to meet the needs of mobile users because cloud computing is based on a centralized model in which data and applications are stored in remote data centers, which can lead to latency and bandwidth issues for mobile users who require fast access to data and applications. Therefore, the MEC architecture must prevent malware from disrupting communications in the network and provide fault tolerance [

1,

7]. Edge servers may be subject to hardware failures, network interruptions, or software errors that can cause service interruption. In addition, the proximity of edge servers to end users increases the risk of attacks to which edge servers may be subject, which may significantly compromise network activities. Thus, MEC architectures must be able to cope with both MEC servers’ fault tolerance and security issues.

Integrating Software-Defined Networking (SDN) into a MEC architecture enhances the security and efficiency of the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) systems by providing a centralized view of the network and dynamic updating of security policies, crucial for protecting connected medical devices. SDN enables rapid detection and response to attacks, such as DDoS or intrusions, by intelligently redirecting traffic and enabling the application of adaptive security policies to guarantee the confidentiality and integrity of sensitive medical data. It also optimizes resources by prioritizing critical traffic, such as patient monitoring data, and integrates third-party security systems (Intrusion Detection System/Intrusion Prevention System, firewalls) for real-time analysis. In addition, SDN improves fault tolerance by reconfiguring the network in the event of an MEC server failure, ensuring high availability and low latency, essential for IoMT applications where continuity of care and responsiveness are vital.

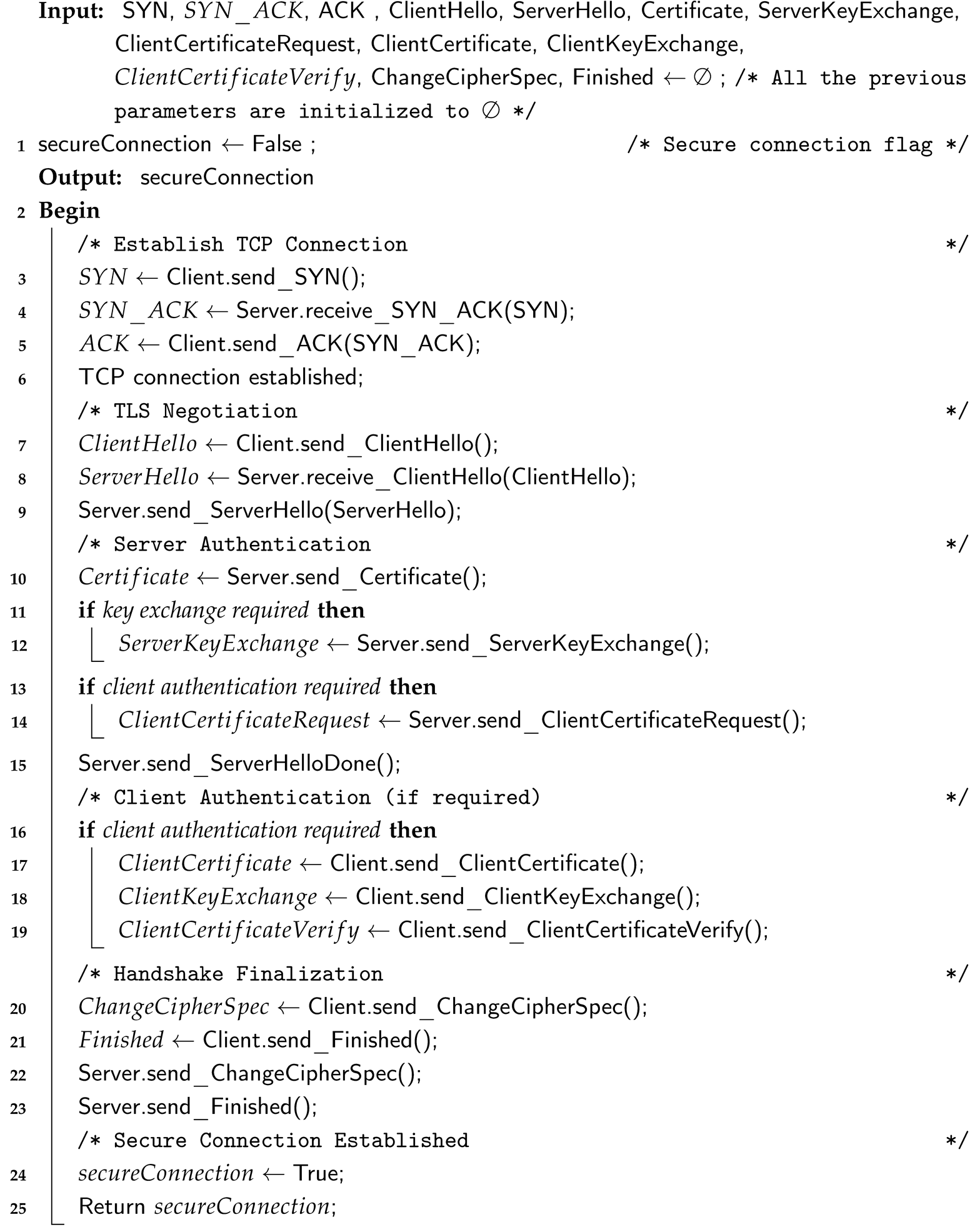

In IoMT, connected devices collect and deliver user data such as body temperature, blood pressure, weight, stress, and transplant patients. That is, fault tolerance and security aspects are challenges that need to be managed to avoid data loss and compromise the safety of end users, who are patients in our scenarios. As stated by Raihan et al. [

8], IoMT devices are resource-constrained, making them vulnerable to security and privacy issues that threaten the healthcare system and put human lives in danger. From the presentation of the security and privacy requirements for IoMT that they present (

Figure 1), Raihan et al. [

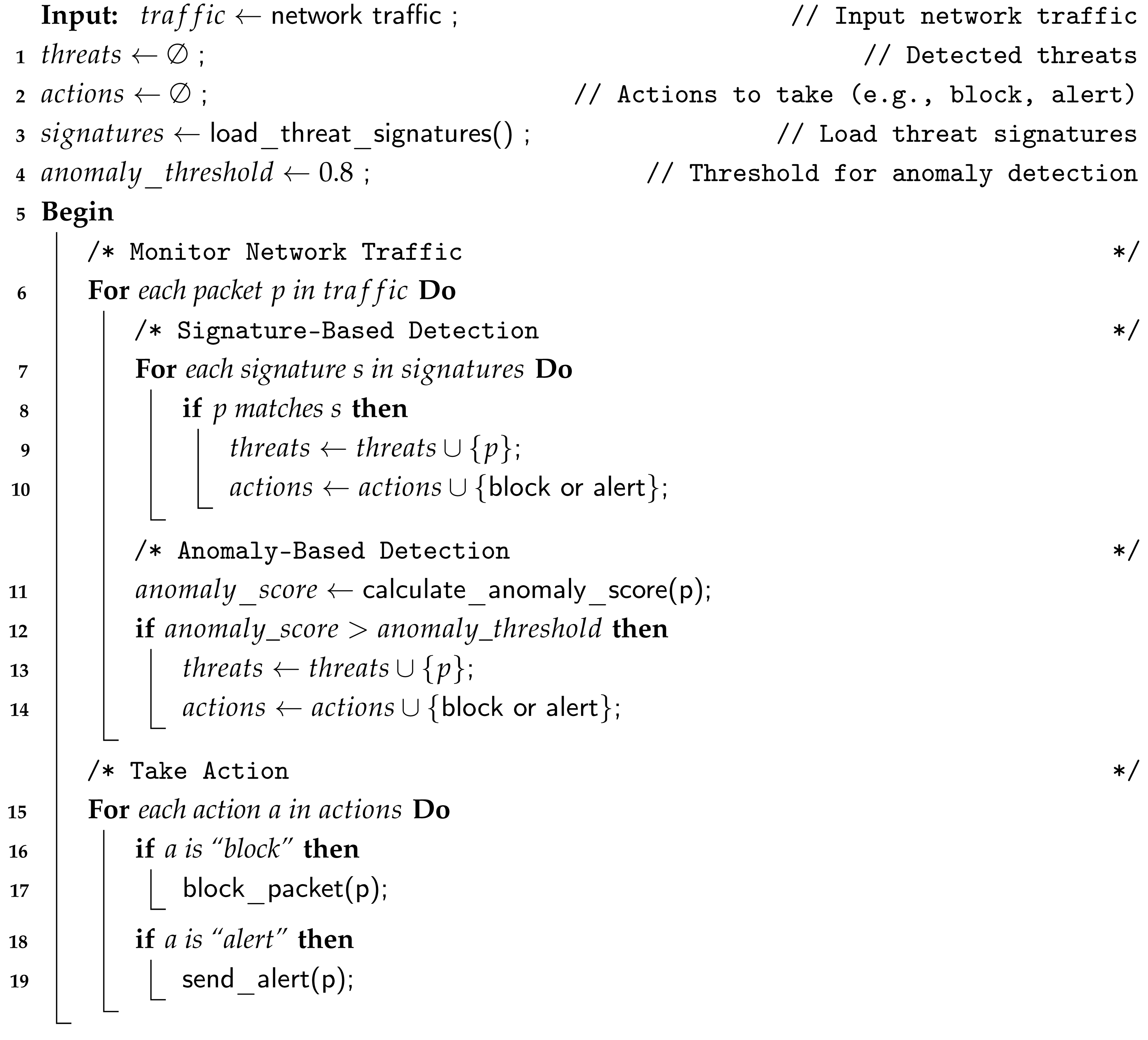

8] deduced the security and privacy vulnerabilities of IoMT. Our research focuses on the vulnerability of communication devices as described in

Figure 2. Our scientific contribution is divided into three main parts. Firstly, we propose an MEC architecture deployed in an SDN, designed for IoMT [

9]. Secondly, we propose a security algorithm to protect our proposed architecture, and finally, we incorporate a fault-tolerant mechanism into our secured MEC architecture to make it robust for healthcare application scenarios. The idea behind our methodology is threefold: (1) simplicity in the deployment and implementation of the network, (2) efficiency in data acquisition and processing operations, and (3) robustness in the event of attack and failure of the operating servers. That is why we make use of well-known tools and techniques for our proposal to deal with attacks and fault tolerance in communication devices.

Compared to other existing MEC-SDN-IoMT security frameworks like the ones presented in [

10,

11], PERSEUS introduces a unified and adaptive approach that jointly addresses cybersecurity and fault tolerance in medical environments. Its main innovation lies in the integration of a four-phase defensive pipeline with a Kubernetes-based fault-tolerant MEC infrastructure. This design ensures continuous service delivery and low-latency threat mitigation, even in the event of DDoS attacks or MEC server failures. In addition, the use of SDN programmability enables centralized orchestration of network security and resilience policies, while the dynamic rule update mechanism allows the system to evolve in response to emerging threats.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows, in

Section 2, we present the review of the literature on MEC, IoT, and IoMT. In

Section 3, we present our scheme designed to address the fault tolerance and security aspects in an IoMT network based on an MEC architecture. We present the simulation results in

Section 4 and conclude the paper in

Section 5.

2. State of the Art

MEC was first proposed by the European Telecommunications Standards Institute group in 2014 and was defined as a new platform that provides IT and cloud computing capabilities within the radio access network (RAN) close to mobile subscribers [

9]. Precisely, in MEC architectures, the end-user equipment’s (UE’s) tasks that require intense computation and are subject to critical latency can be offloaded and processed at the edge of the network on servers known as MEC servers, not far from the wireless access points (APs), with the aim to free the UEs that are limited with the seek to avoid heavy computing workloads, and consequently to extend the battery lifetime of these UEs. Typically, MEC servers are small data centers that are deployed by the cloud computing or telecommunication operators, which can be at the same location with the wireless APs (public WIFI routers and base stations, etc.). In that context, MEC allows APs to have processing power and storage, thus, guarantees that the UEs can directly be connected to the edge cloud. Compared with mobile cloud computing (MCC), MEC possesses four main advantages, which are latency reduction, energy savings, context awareness, and privacy/security enhancement, mainly due to its proximity to end users. Moreover, information-centric networks (ICNs) [

12] provide an alternative end-to-end service recognition paradigm for MEC, shifting from a host-centric to an information-centric architecture for the implementation of context-aware computing, such as computing tasks related to image or video processing.

The IoT refers to the network of physical objects, devices, sensors, and other “things” embedded with connectivity, software, and sensors that enable them to collect and exchange data. That network is used in all domains. It enables the efficient management of utilities, transportation systems, waste management, and public services [

13]. In industrial applications, IoT monitors assets and is used for predictive maintenance, supply chain optimization, and process automation [

14]. In applications of smart homes and buildings, IoT devices are used for home automation, energy management, security systems, and environmental monitoring [

15]. Technologies such as Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, Zigbee, and cellular networks facilitate communication between IoT devices and IoT platforms [

16]. Standardized protocols such as message queueing telemetry transport, the restricted application protocol, and the hypertext transfer protocol are used for efficient and lightweight data exchange in IoT deployments. In medical applications, IoT devices are used to monitor patients in real-time scenarios. In this case, a combination of IoT devices with an MEC architecture can help to improve the quality of service to efficiently monitor the health situations of end users [

1].

The mobile healthcare system (M-health) is a system that is intended to maintain patient health records remotely, allowing physicians to access them from anywhere and provide medical advice according to a given need. This arrangement improves accessibility and efficiency because both patients and physicians do not have to meet face-to-face [

17]. Therefore, patients from their residences can receive medical prognoses and prescriptions from doctors through IoMT. Radio frequency identification technology plays a vital role in the identification of patient personal information and access to medical records [

18,

19]. The IoMT refers to the interconnected network of medical devices, sensors, wearables, and healthcare systems that collect, exchange, and analyze health-related data to improve patient care and outcomes. It can also be used for remote patient monitoring for chronic disease management. In this regard, IoT devices enable the continuous monitoring of vital signs, medication adherence, and symptom tracking, leading to early intervention and improved patient management [

20]. The integration of sensors and wearables into healthcare systems allows real-time data collection, analysis, and personalized interventions. IoMT enables remote consultations, virtual visits, and remote diagnostics, allowing wider access to healthcare services.

Table 1 presents a summary of the works on MEC, IoT and IoMT as well as the issues that must be considered when defining solutions for these technologies.

In this paper, we propose a secure and fault-tolerant architecture for the IoMT that is based on an MEC architecture deployed in an SDN. Our proposal is designed to deal with vulnerabilities on communication devices, particularly to address the DDoS attacks and to provide fault tolerance of MEC servers.

3. The Proposed Scheme

In this section, we present the MEC architecture for the IoMT scenario in

Section 3.1, then in

Section 3.2, we present the secure scheme to counter the security attacks within the proposed architecture. Lastly, in

Section 3.3, we present the fault tolerance mechanism that is considered in our architecture.

3.1. The Proposed Architecture

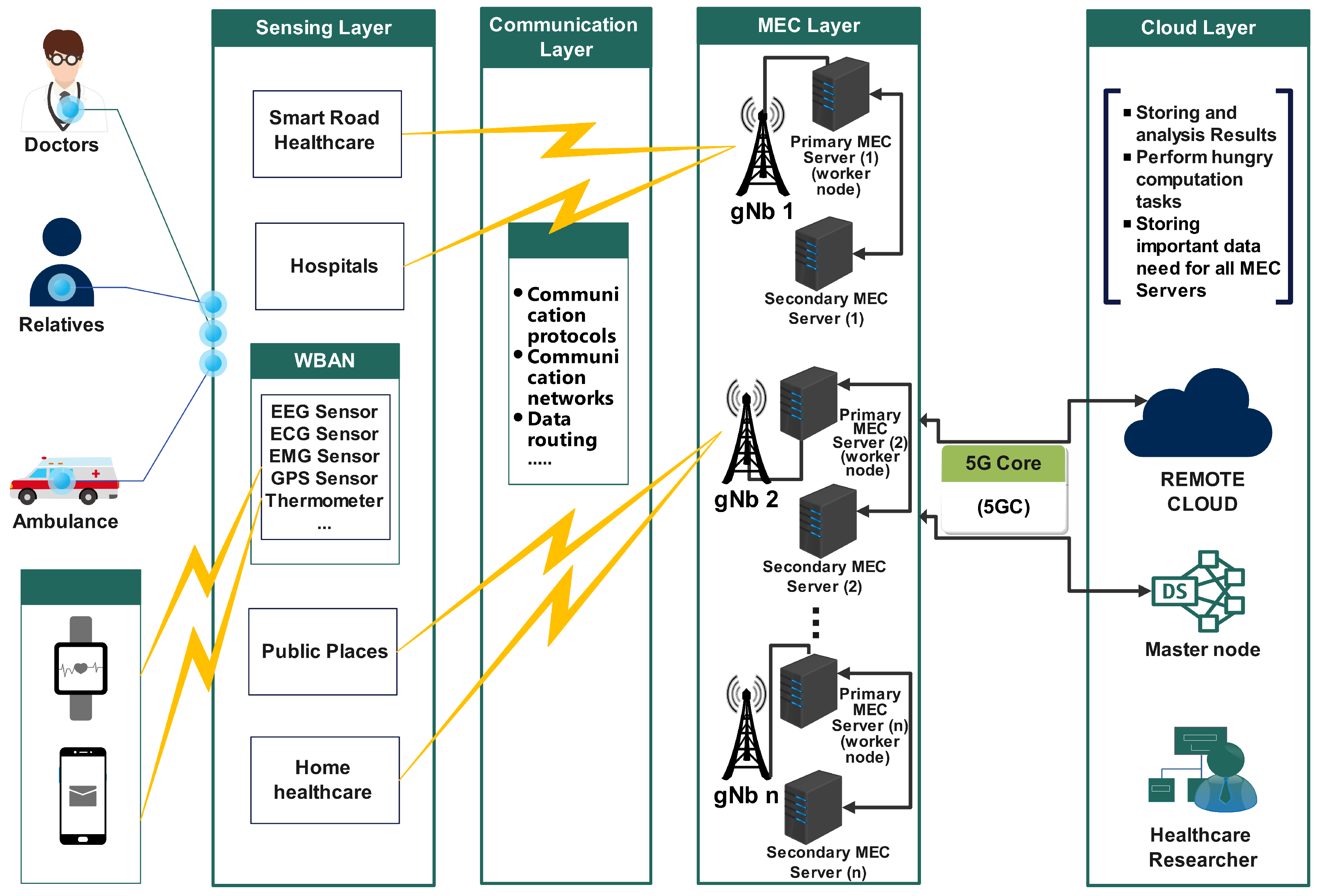

The proposed architecture is shown in

Figure 3. The architecture shows the 6G IoMT-enabled smart healthcare system that employs MEC servers as the middleware layer. The architecture has four different layers: The sensing layer is used to acquire data, the communication layer for tasks computational offloading, the MEC layer for task processing at the edge, and the cloud layer for remote processing and storage. Data are collected using different types of medical sensors also known as IoMT devices. Since IoMT devices have limited storage and processing capabilities, data that require intensive data processing are transferred to a device that has more powerful computing characteristics. The device chosen for further processing could be a MEC server, a cloud computing server, or the IoMT device (in the case of tasks that do not require impressive computing characteristics). The multi-interface base station or the next generation node base station is employed by the MEC server to collect data generated by the IoMT devices of the 6G infrastructure. Lastly, healthcare data can be analytically processed and used to make appropriate decisions. Edge Cloud Computing is the monitoring of the environment and management of system resources. The gNB function is to receive the tasks, schedule them, and manage resources to process the most significant amount of the offloaded tasks, or transfer data to the adjacent Edge Computing and direct the tasks to the available resources.

In the Sensing Layer, physical objects (home appliances, actuators, sensors, etc.) are interconnected and can communicate intelligently using the Internet. For example, in healthcare applications, the IoT is used to achieve an inventive future known as IoMT. The IoMT is compound of devices that provide healthcare solutions at any time and anywhere. There exist many types of IoMT devices.

Table 2 shows a nonexhaustive list of some medical sensors that can be used to collect data from the human body [

28].

The Communication Layer is an essential layer of the proposed architecture that facilitates communication and data exchange between different components of the system, such as sensors, devices, servers, processing platforms, and end-users. This layer plays a key role in connectivity and data transmission in the context of MEC.

The Mobile Edge Computing Layer is a key layer responsible for delivering computing, storage, and processing capabilities as close as possible to end users in the wireless access network. This layer leverages computing and storage resources available at the network edge, such as base stations, Wi-Fi access points, and proximity servers, to deliver low-latency, high-capacity computing and processing services.

The Cloud Layer provides large-scale computing, storage, and processing services like those of the cloud. This layer offers advanced data analysis, long-term storage, and processing capabilities, taking advantage of centralized cloud resources.

3.2. The Security Algorithm

To achieve our objectives, we proposed a security algorithm which uses Virtual Private Network (VPN), SDN, and Intrusion Detection System/Intrusion Prevention System (IDS/IPS) technologies that consist of a phase to select and secure the transmission channel, a phase to detect intrusions, and updating the security rules and threat signatures accordingly. The algorithm is executed by the MEC servers in the MEC layer in

Figure 3. The Threat Security Algorithm presented in the flow chart in

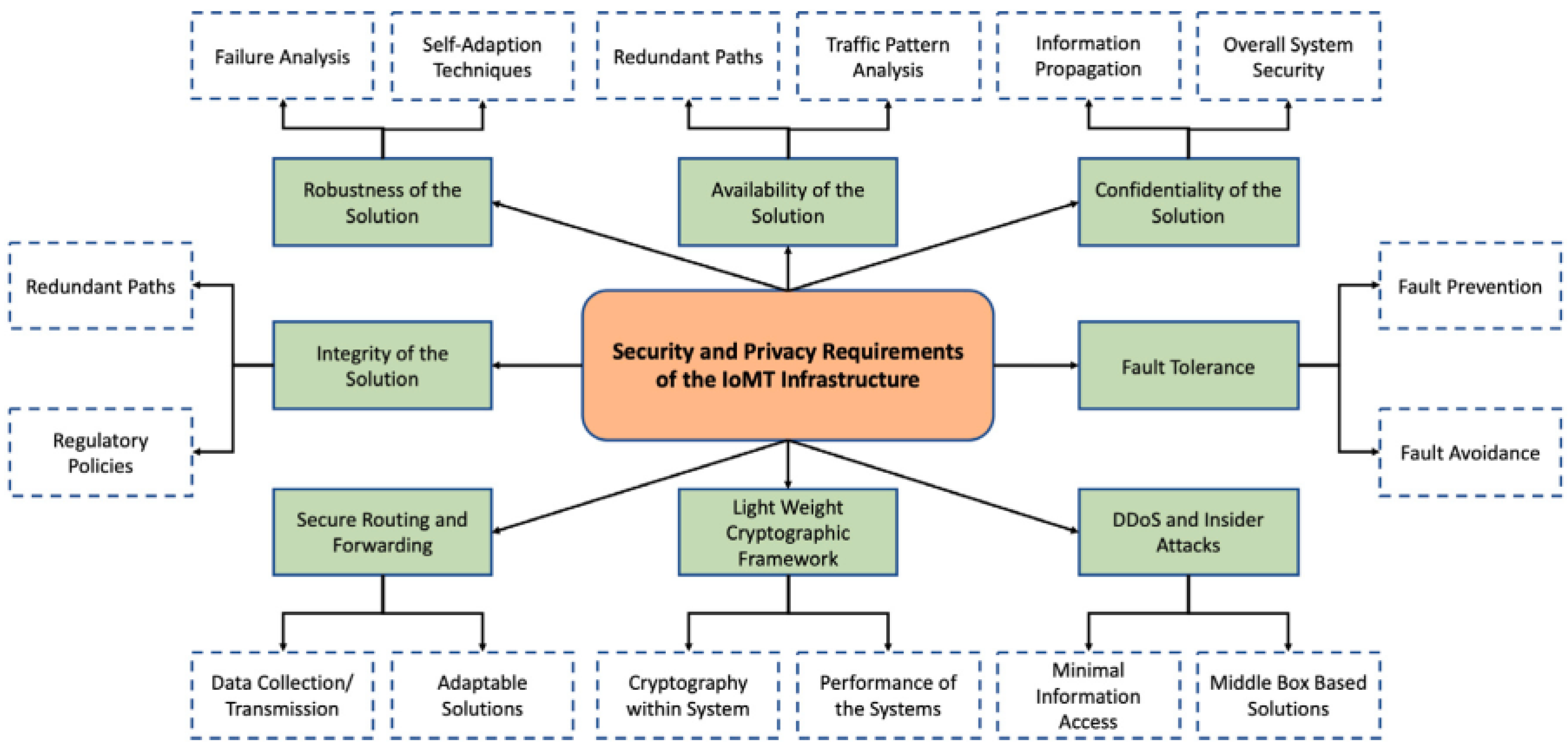

Figure 4 describes a multistep process to protect a network from malicious activity. Firstly, it establishes a secure VPN connection by checking the availability of service, authenticating the user, and establishing a connection with the VPN server (First step). This is done in Algorithm 1.

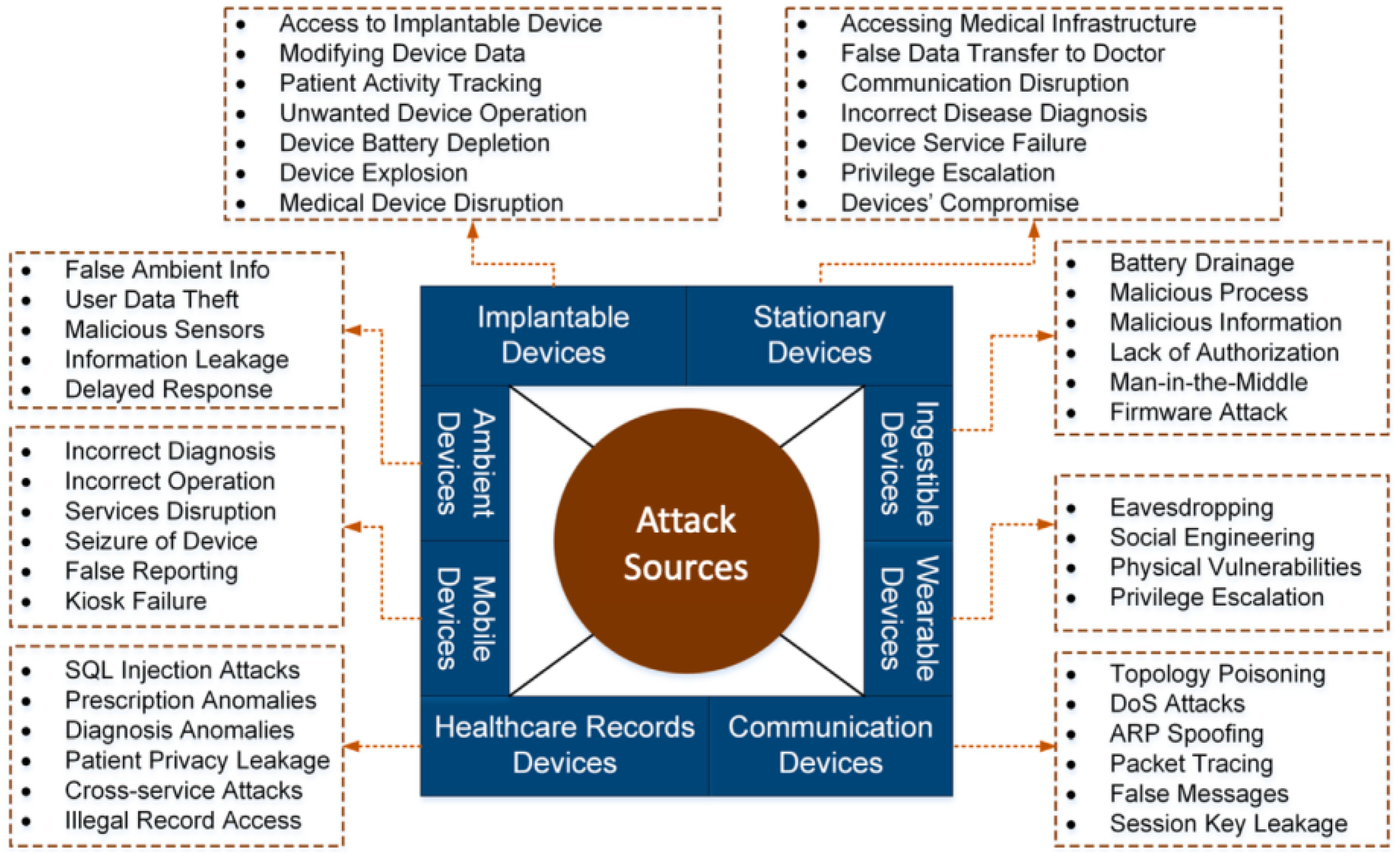

Secondly, it monitors network traffic by capturing and analyzing data packets for anomalies or signatures of known threats and comparing the results with those in a database. That second step is described in Algorithm 2.

Thirdly, as shown in Algorithm 3, if a threat is detected, the algorithm applies intrusion prevention measures, such as blocking or filtering packets associated with the threat, notifying the system administrator, and logging incident details (third step). If a packet matches a known signature and exceeds the anomaly threshold, two actions can be triggered: “block“ and “alert“. The algorithm then prioritizes immediate blocking preventing potential threats while logging an alert for traceability purposes. This ensures rapid response, consistent decision-making, and clear incident tracking. During this step, the IDS/IPS Algorithm integrates two fundamental network security mechanisms: signature detection and anomaly detection, while managing automated actions (blocking and/or alerting). The anomaly score is computed using Algorithm 4. This calculation can be performed statically or dynamically [

29]. In the context of this work, we opted for the static method. Thus, the anomaly score (f(p)) is calculated by comparing the feature vector (

) of each packet (e.g., size, duration, ports, protocol) to a reference profile of normal network behavior characterized by its mean

and standard deviation

. The squared deviation

measures the deviation of the packet from typical traffic patterns. This distance is normalized using (

) to account for natural fluctuations in normal traffic. The result is then transformed using an inverse exponential function

, which produces a score between 0 and 1.

Finally, in Algorithm 5, the security algorithm regularly updates security rules by analyzing new threats and vulnerabilities to improve intrusion detection and prevention capabilities against future security attacks (Fourth step). In this step, the distinction between the two functions

and

lies in their respective roles and levels of contextual awareness within the rule update process. The function

is used when a detected threat

corresponds to a known vulnerability

. In contrast,

is invoked when a vulnerability

is known but has not yet been exploited or covered by existing rules; it generates a generic and preventive rule to reduce exposure before an active threat occurs. Repetition of these steps ensures proactive monitoring and enhanced threat protection to maintain a secure network environment. The introduction of Network Function Virtualization (NFV) contributes to increasing the level of security in the network by offering several advantages. NFV enables virtualized security functions such as firewalls, IDS, IPS, and security gateways to be deployed and managed flexibly and dynamically. This reduces dependence on specific hardware and improves the scalability and flexibility of security functions. Importantly, the security algorithm uses a fixed threshold of 0.8 for anomaly detection. The value represents a compromise between sensitivity and specificity, reducing false positives while maintaining effective detection. It is typically calibrated on reference datasets where it shows a balanced precision/recall ratio. Moreover, a threshold of 0.8 offers a conservative margin above the uncertainty threshold (generally around 0.5–0.6) [

30], while dynamic adaptation may introduce significant overhead. A fixed threshold facilitates investigation and correlation of alerts. In terms of security, the system could gradually adapt to low-intensity malicious traffic, and an adversary could manipulate the threshold by injecting specific traffic should the threshold is dynamic.

| Algorithm 1: TLS Protocol. |

![Applsci 15 12692 i001 Applsci 15 12692 i001]() |

| Algorithm 2: Network Traffic Monitoring. |

![Applsci 15 12692 i002 Applsci 15 12692 i002]() |

| Algorithm 3: IDS/IPS Algorithm. |

![Applsci 15 12692 i003 Applsci 15 12692 i003]() |

| Algorithm 4: Calculate_anomaly_score (p). |

![Applsci 15 12692 i004 Applsci 15 12692 i004]() |

| Algorithm 5: Update Security Rules. |

![Applsci 15 12692 i005 Applsci 15 12692 i005]() |

3.3. The Fault Tolerance Mechanism

Fault tolerance is the ability of a system to continue to function in the presence of failures [

31]. In other words, fault tolerance helps minimize the impact of failures on general network tasks [

27]. Failure is a state in which the system stops functioning as it should in normal circumstances. According to Ravi et al. [

31], cloud computing failures are encountered at the server level or the network level. In server components, hard disks are the most failure-prone components and the reason for server failures. Applications in cloud computing must reduce the hard disk utilization of hard disks that have already experienced failure to meet the high availability and reliability requirements of cloud services. For the network level, a failure occurs when there is a link break between network devices or when the devices do not route or forward packets.

There are three main methods to prevent Byzantine and crash faults in a cloud environment [

31]: (1) Checking and Monitoring (CaM), which regularly monitors the system at runtime to verify, validate and ensure that the correct system specifications are met. (2) Check and restart (CaR) in which the system state is captured regularly basis according to predefined parameters, allowing its restoration at the previously saved state when a fault is detected at any moment, and finally (3) Replication in which the system components are regularly duplicated. In the latter approach, when the main system fails, the backup system is automatically invoked to continue the service. With CaM and CaR methods, system restoration after a system fault is encountered can consume more time and cause more data loss than the replication method. Considering the nature of IoMT networks where there is sensitive data that can threaten the life of the end user, we then adopt the replication methods for the fault tolerance approach in our architecture.

The proposed fault tolerance management is based on Kubernetes, which is a leading container orchestration platform that extends its reach to the edge, offering sophisticated tools to manage containerized applications in a decentralized environment [

32,

33]. In an IoMT environment where service availability and reliability are critical, Kubernetes is a robust solution to manage fault tolerance in an MEC cluster. Unlike traditional redundancy approaches based on manual replication or static failover mechanisms, Kubernetes offers dynamic orchestration of workloads thanks to its failure detection and automatic pod reallocation system. In the event of failure of a primary MEC server, Kubernetes can immediately redeploy services to a secondary server without human intervention, guaranteeing high availability. In addition, with its StatefulSets and Persistent Volumes mechanism, Kubernetes ensures efficient synchronization of critical data between MEC servers, avoiding information loss and inconsistencies. Traditional solutions such as hardware load balancing are often inflexible, require specific configuration, and do not effectively manage the scale and variability of loads in a dynamic environment such as the IoMT. By integrating advanced auto-scaling, monitoring, and failure management strategies, Kubernetes is the ideal alternative to guarantee service continuity in the IoMT, while reducing human intervention and optimizing the use of network and computational resources. For this purpose, all MEC servers on the network form the Kubernetes cluster where each MEC server constitutes a worker node for Kubernetes, and the master node is installed in the cloud layer of the architecture we have proposed in

Figure 3. Thanks to the real-time information exchanged between the Kubelet and Kubeproxy components of the worker nodes and the Application Programming Interface server of the master node, the master node is aware of the worker nodes’ (MEC Server) status in real-time at any moment. Each worker node (MEC Server) also known as Primary Mec Server (PMS) has a backup server known as Secondary MEC Server (SMS). By default, each data stored in the PMS is duplicated into the SMS (operation performed by the PMS). The SMS is dormant and only acts as PMS when the current PMS is faulty, avoiding lost of data while the fault on the PMS is being solved.

We opt for the replication method to solve the fault tolerance in our architecture. Each MEC server called the primary MEC server or PMS is connected to a backup server called the secondary MEC server or SMS that has the same physical characteristics as the principal one. All data received by the PMS are automatically duplicated in the SMS. Moreover, no direct communication is established between end-user devices and SMS, that is, data duplication does not impact the communication layer between end-user devices and the PMS. In addition, the master node stores two configuration files in its memory: the first, named is used to configure a server as a PMS with an IP address and a network gateway, and the second, named is used to configure a server as an SMS. When the PMS is faulty, the master node installed in the cloud layer is aware because of the regular information it exchanges with the PMS as previously described. In such a situation, the master node uses the file to launch the auto-configuration of the SMS, which allows the latter to act as the new PMS while the problem of the faulty PMS is solved. The configuration done at this stage aims to provide the SMS with the same configuration including the IP address, the applications, etc. that was previously held by the PMS. Using the Kubeadm tool, the newly configured PMS is easily connected and added to the cluster, and all applications are replicated on it given the horizontal pod autoscaling (HPA) of Kubernetes. By doing so, the end-user devices are not included in the fault tolerance management process and their communication is also not disturbed. At the same time, with the auto-configuration of the SMS, the faulty PMS is disconnected from the network and repaired. Once the faulty PMS is restored, it sends a message to the master, and the new PMS announces its availability. After receiving the notification, the master node launches the auto-configuration of the previously faulty PMS with the file. Finally, the newly configured server now acts as the SMS for the server that was previously configured as PMS when the current server was faulty. From this moment on, to ensure a possible fault of the working PMS, the database of the latter is copied to the current SMS and the network continues its functionality as if it has never had a faulty server.

4. Simulations and Analysis

This section presents the simulation environment (

Section 4.1) and the simulation results with the analysis in

Section 4.2.

4.1. Simulation Environment

The implementation was done in a Mininet simulator running on a Dell Latitude E5570 computer with a 2.53 GHz core i7 processor (4 CPUs), 8 GB RAM, and a Radeon R7 M260/M265 graphics card (2Gb dedicated). The system runs on a 64-bit Linux distribution (22.10). Some of the parameters used in mininet were set as follows: controller-controller bandwidth = 100 Mbps, controller-IoT device = 50 Mbps with a custom tree topology. These parameters influence the observed measurements. Bandwidth and queues affect throughput and packet loss, while delay affects end-to-end latency. For the simulation, we developed a topology consisting of 18 hosts and 15 switches. We used the Floodlight SDN controller with the OpenFlow 1.4 protocol version.

A key feature of Mininet is its support for SDN programming. It can be integrated with popular SDN controllers, such as OpenDaylight or Ryu, enabling the creation of programmable networks and the testing of SDN applications. This facilitates the creation and testing of new network architectures as well as the development of innovative network applications. Mininet also offers advanced features such as packet capture, network traffic monitoring, real-time debugging, and network behavior customization. It is widely used in academic research to evaluate the performance of communication protocols, to study network security issues, and to simulate complex network scenarios.

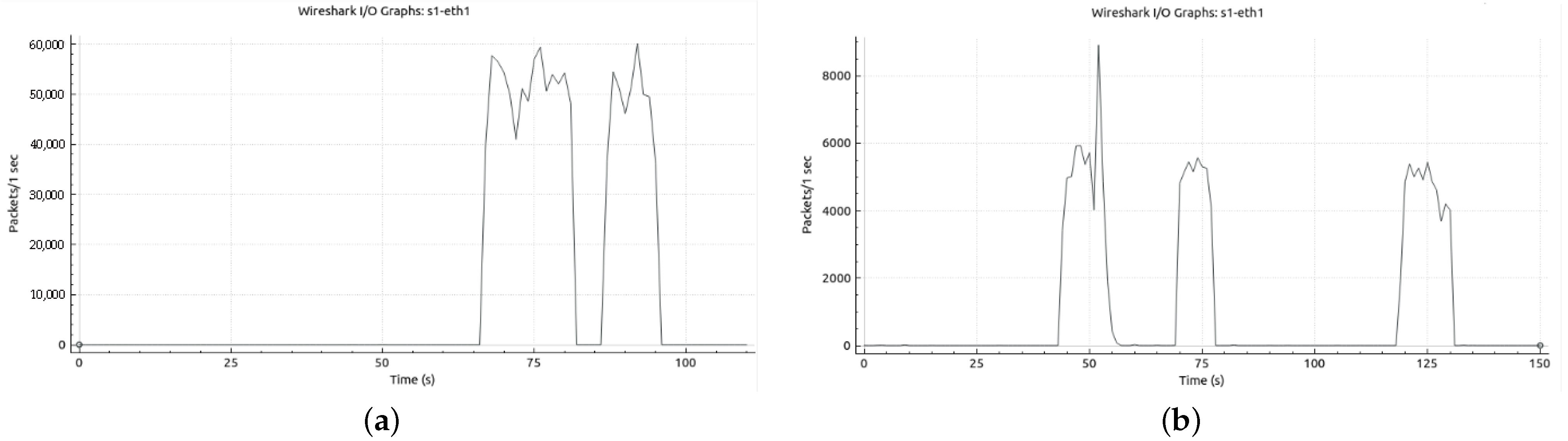

Hping3 is a network tool that can send TCP/IP packets and display the target response the same way as the ping program does with ICMP responses. Hping3 handles fragmentation, packet contents, and arbitrary sizes, and can be used to transfer files encapsulated in supported protocols. As shown in

Figure 5, we have many packets arbitrarily sent per time unit ranging from 40,000/s to 60,000/s for 128 s.

Table 3 shows the specifications recommended to implement our proposed solution.

Concerning fault tolerance evaluation, we have a Kubernetes cluster with one master node and two worker nodes, one acting as the primary MEC server and the other as the secondary MEC server. The Kubernetes version is microk8s v1.0.

4.2. The Simulation Results

To simulate the DDoS attack, we generated a large volume of traffic that targets a specific host in the network. The simulated attack aims to overwhelm the target’s resources and disrupt its normal functioning. In MiniNet, we can utilize various tools and techniques to generate the desired traffic and simulate the DDoS attack. One common approach is to use traffic generation tools such as hping3 iperf to generate a large number of packets and send them to the target. By configuring the traffic generation tool with appropriate parameters, such as packet size, rate, and destination IP address, we can simulate the characteristics of a real DDoS attack. The generated traffic floods the target’s network interface, overwhelming its processing capabilities, and potentially causing service disruptions. During the simulation, we monitored the behavior of the target and the overall network. We observed the impact of the DDoS attack on the target’s performance using metrics such as latency, packet loss, and throughput. Additionally, we analyze the network’s response to the attack, which includes the ability to detect malicious traffic and mitigate attacks.

Figure 5a shows the monitoring of the system before the DDoS attack (before HPING3) and

Figure 5b shows the monitoring of the system after the DDoS attack (after HPING3). It can be seen that the number of normal packets transmitted drastically decreases after the DDoS attack is launched. The impact on network performance is a crucial aspect when evaluating a security algorithm.

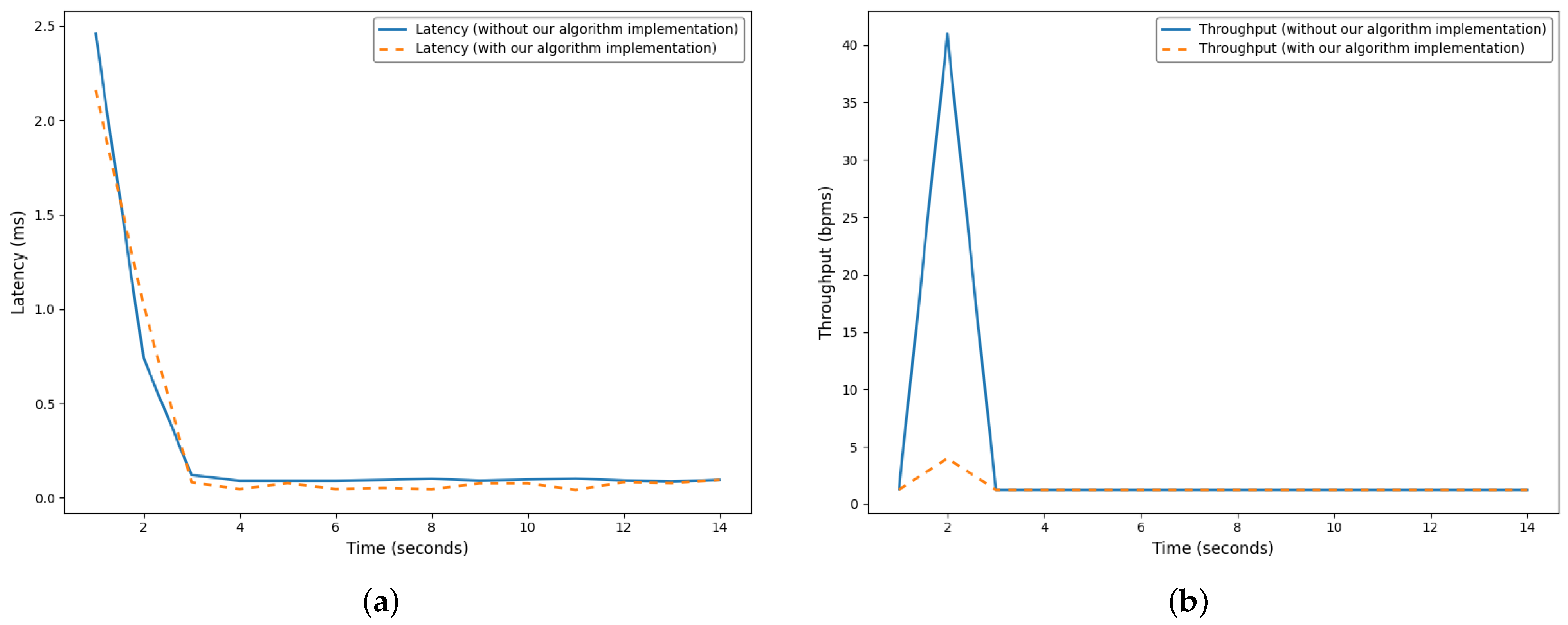

4.2.1. Latency

When the security algorithm analyzes and processes network packets to detect attacks, it can introduce latency in data processing. This can lead to a slight delay in the delivery of the packets, as can be seen in

Figure 6a. It is essential to measure this latency and ensure that it remains within acceptable limits for real-time or latency-sensitive applications such as IoMT. High latency can adversely affect network performance by delaying data transmission. In our case, the latency when our algorithm is implemented is the same as when our algorithm is not implemented, meaning that our algorithm does not affect the parameter that much.

4.2.2. Throughput

The security algorithm may consume network and computing resources to analyze packets in depth and detect threats. This can potentially reduce the achievable overall network throughput by limiting the amount of data that can be transmitted per unit of time. It is important to measure the impact on performance and ensure that it remains high enough to meet the needs of users and applications. Optimizations of the algorithm may be necessary to minimize resource consumption and maintain satisfactory performance. As shown in

Figure 6b, the throughput remains almost constant before and after the implementation of our algorithm.

4.2.3. Security Evaluation

The Transport Layer Security (TLS) protocol is used in the communication channel to ensure the integrity and authenticity of the transmitted data. Securing the communication channel, especially in the context of Man-in-the-Middle attacks, is crucial. When communication is conducted without encryption, a potential attacker can intercept the data in transit and read, modify, or inject malicious data. Using the TLS protocol, data is encrypted before being sent over the network. This ensures that only legitimate users can decrypt and access the transmitted data. Additionally, TLS provides mechanisms for authenticating and verifying the identities of servers and clients. As shown in

Figure 7, our communication channels are secured by the TLSv1.2 protocol. The choice of TLSv1.2 in the security algorithm, despite the efficiency and adoption of TLSv1.3, is driven by compatibility with legacy IoMT devices, regulatory compliance, and the need for a stable, proven protocol in critical healthcare settings. TLSv1.2 ensures seamless integration with older systems, meets current regulatory standards, and provides a balance between security and performance for resource-constrained medical devices, while organizations gradually transition to TLSv1.3 in a controlled manner to minimize risks in life-critical applications.

Furthermore, in

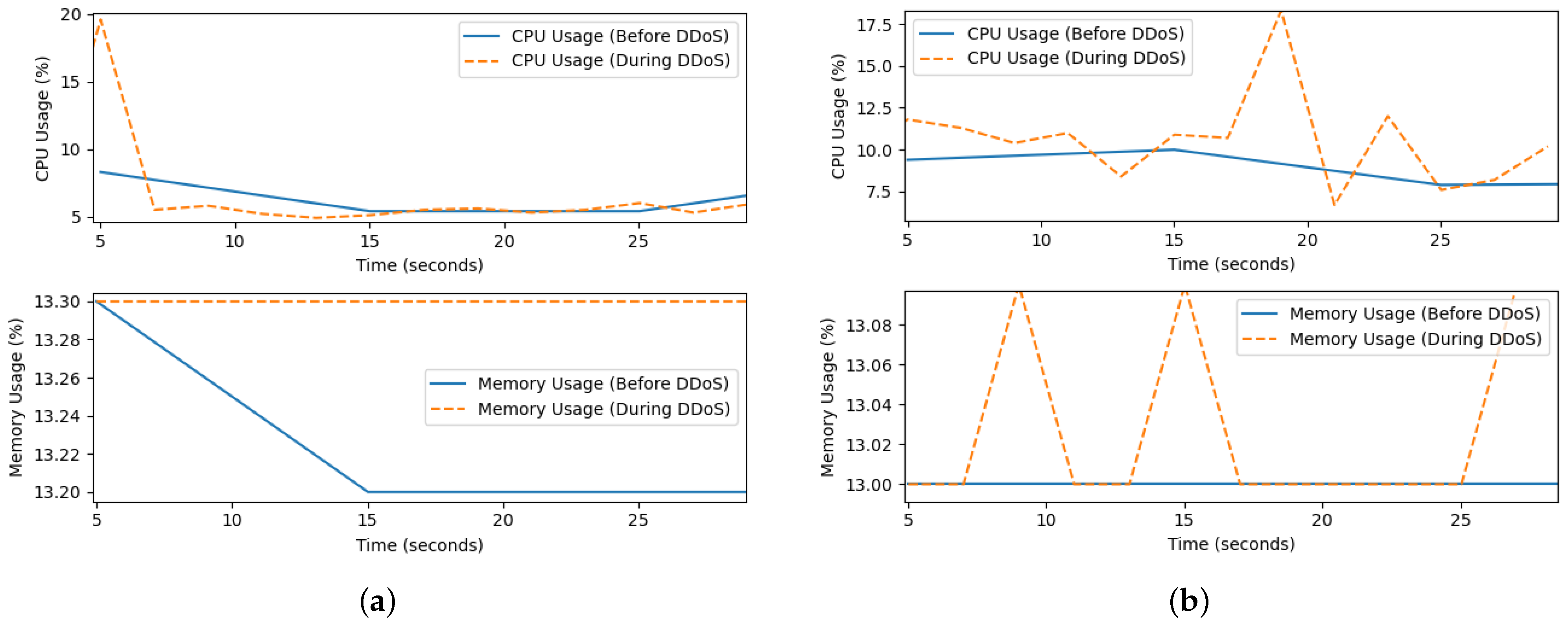

Figure 8, the impact of security operations is shown. While

Figure 8a presents the CPU and memory usage of the system in the presence of the DDoS attack without implementing our secure algorithm,

Figure 8b presents the same metrics used during the DDoS attack when our algorithm was executed. It is observed that during the attack, the CPU is most used when our algorithm is executed, while at the same time, the memory usage is lower. This in addition to the observations made in

Figure 7 simply shows that our secure scheme is effective in the presence of DDoS attacks. The previous assertion is confirmed in

Figure 9 where it is observed that the application response time during the DDoS attack when our algorithm is not executed (

Figure 9a) is lower than the application response time during the same attack when our algorithm is executed (

Figure 9b), which is quite normal due to security operations. It is important to note that in the presence of DDoS attacks on a network, memory and CPU usage, as well as application response time and throughput, are most affected. We therefore focus on these metrics in evaluating the effectiveness of our secure approach against DDoS attacks in our designed IoMT architecture.

From the previous observations on the security analysis, we conclude that our proposed security algorithm is able to counter DDoS attacks, which is part of the security and privacy requirements for IoMT infrastructure as we presented in

Table 1. Moreover, we can also conclude that our algorithm solves the communication device problem (DDoS as presented in

Figure 2).

4.2.4. Fault Tolerance Evaluation

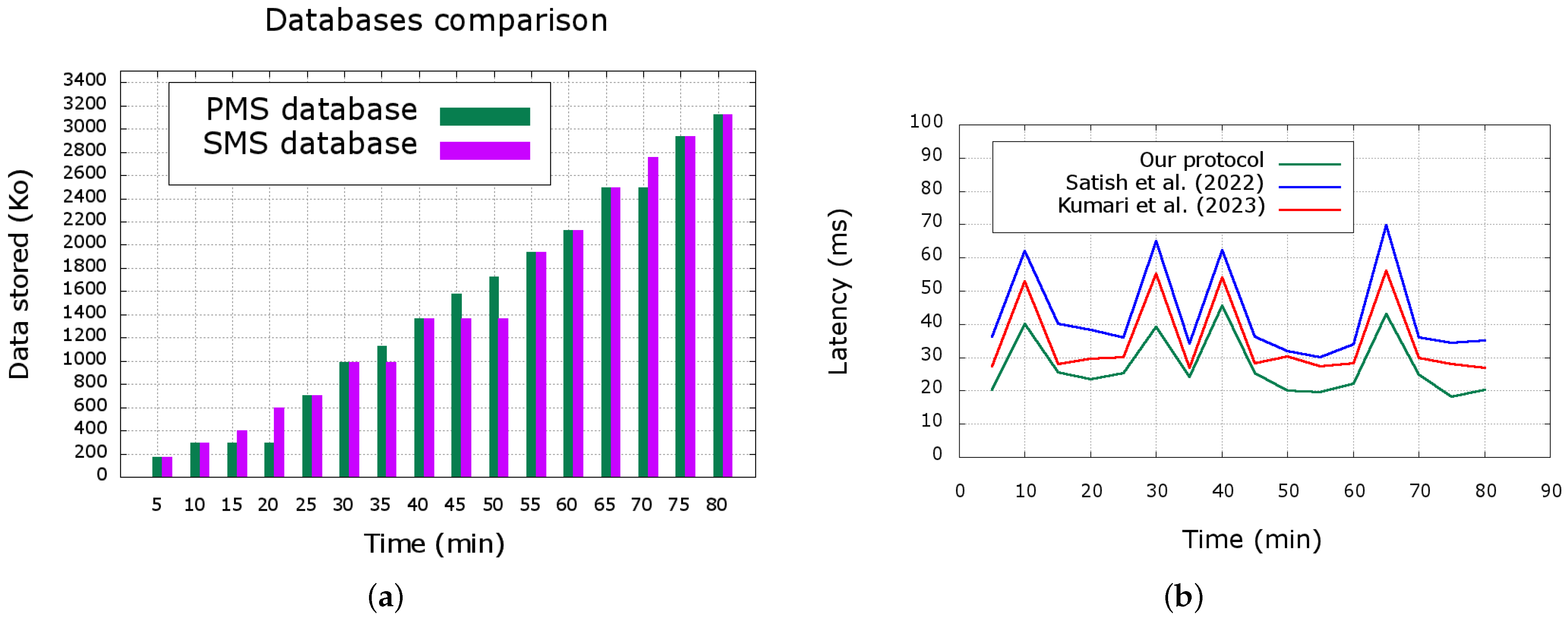

To evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed fault tolerance scheme, we randomly deployed a network with 100 devices that can send 1Ko data items each. Firstly, we evaluate the database status of the primary MEC servers (PMSs) and the secondary MEC servers (SMSs) in situations where the PMS is faulty. Secondly, the latency of the communication is evaluated to emphasize the impact of fault tolerance management in the data transfer. Third, the average packet lost when there is a faulty server is evaluated in comparison with other existing works in the literature. Fourth, recovery time is evaluated after a fault has been detected in an MEC server. Finally, the replication overhead corresponds to the resource cost (bandwidth, RAM, etc.) necessary to ensure data synchronization between the PMS and an SMS after a fault has been resolved. The results are presented in

Figure 10a,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12.

In

Figure 10a, the PMS and SMS databases are evaluated when faults are detected in the system. The PMS becomes faulty after the 10th minute simulation time, from that time, the SMS is considered as the new PMS until the 25th minute simulation time when the faulty server of the initial PMS is solved and the databases are synchronized. After that, the SMS, which was acting as the PMS since the first became faulty on the PMS, also becomes faulty in the 30th minute simulation time until the 40th minute simulation time when it is fixed. During this time, the initial PMS begins to act as the running main PMS. From the 40th to the 55th minute simulation time, there is another fault on the initial SMS which is solved. In the 65-min simulation time, the PMS becomes faulty, leaving the SMS acting as the main PMS until the 75-min simulation time, when the faulty server is fixed and the databases are synchronized. The observation we can make according to the simulation is that each time the server acting as the primary MEC server is faulty, the one acting as the secondary MEC server becomes the primary MEC server. When the faulty server is fixed, both databases are synchronized. This observation enables us to conclude that our fault-tolerant approach is effective when it comes to ensuring the continuity of service.

Figure 10b shows the comparative latency results of our proposed scheme and those of Kumari et al. [

35] and Satish et al. [

36] that use the data replication method and the checkpoint and restart method, respectively, for their fault-tolerance approaches, while we use the data replication method in our approach. The replication method can process user requests efficiently and quickly and manage the load balance between cluster nodes, mainly using Kupe-proxy and Horizontal Pod Autoscaling (HPA) that we introduced in our proposed architecture in

Figure 3. Our proposed fault-tolerant scheme has better latency compared to the schemes in Refs. [

35,

36], thanks to the use of the Kubernetes orchestrator that allows real-time failure detection and PMS reconfiguration. Furthermore, the data replication method we used is an appropriate method to be used in a scenario like IoMT due to the sensibility of managed data. That is, in

Figure 10b, we observed that the latency of our proposed scheme varies from 18.205 ms (the lowest) to 45.65 ms (the highest), while those of Refs. [

35,

36] vary from 27.01 ms to 55.32 ms and 30.12 ms to 69.87 ms, respectively. Interestingly, the latency of our proposed scheme is never more than that of the schemes proposed in Refs. [

35,

36] at a given time.

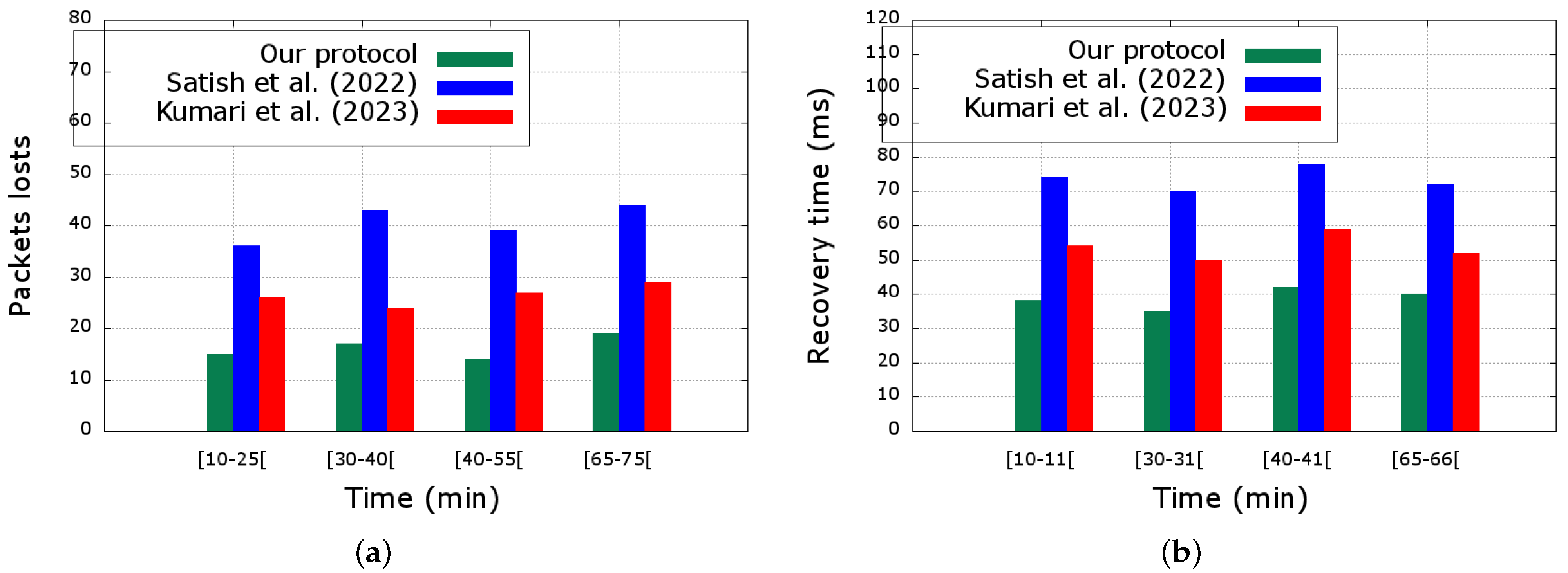

Lastly, we compared the average packet loss per failure of our proposed scheme with those of Kumari et al. [

35] and Satish et al. [

36] in

Figure 11a. Evaluations were performed each time a fault occurred during simulation times (10th minute, 30th minute, 40th minute, and 65th minute) until the faults were solved. We then observed that during all the intervals in which the acting PMS was faulty, the average loss of packets was minimized in our approach compared to those of Refs. [

35,

36]. The number of packets lost varies from 9 to 14 in our approach, while it varies from 19 to 24 and from 31 to 39 for the works in Refs. [

35,

36], respectively. Our approach incurs the least number of packet loss than the other approaches. It can be observed that packet loss cannot be avoided during fault-tolerance management because there are always periods for internal server reconfiguration when faults occur and during that time, items that were in transit in the network can be lost.

Furthermore,

Figure 11b shows that the recovery time of a faulty PMS is shorter in our scheme compared to those of Kumari et al. [

35] and Satish et al. [

36]. The recovery time helps confirm the result presented in

Figure 11a. In

Figure 11, the x-axis corresponds to the time interval during which the data were captured. Finally, since the protocol by Kumari et al. [

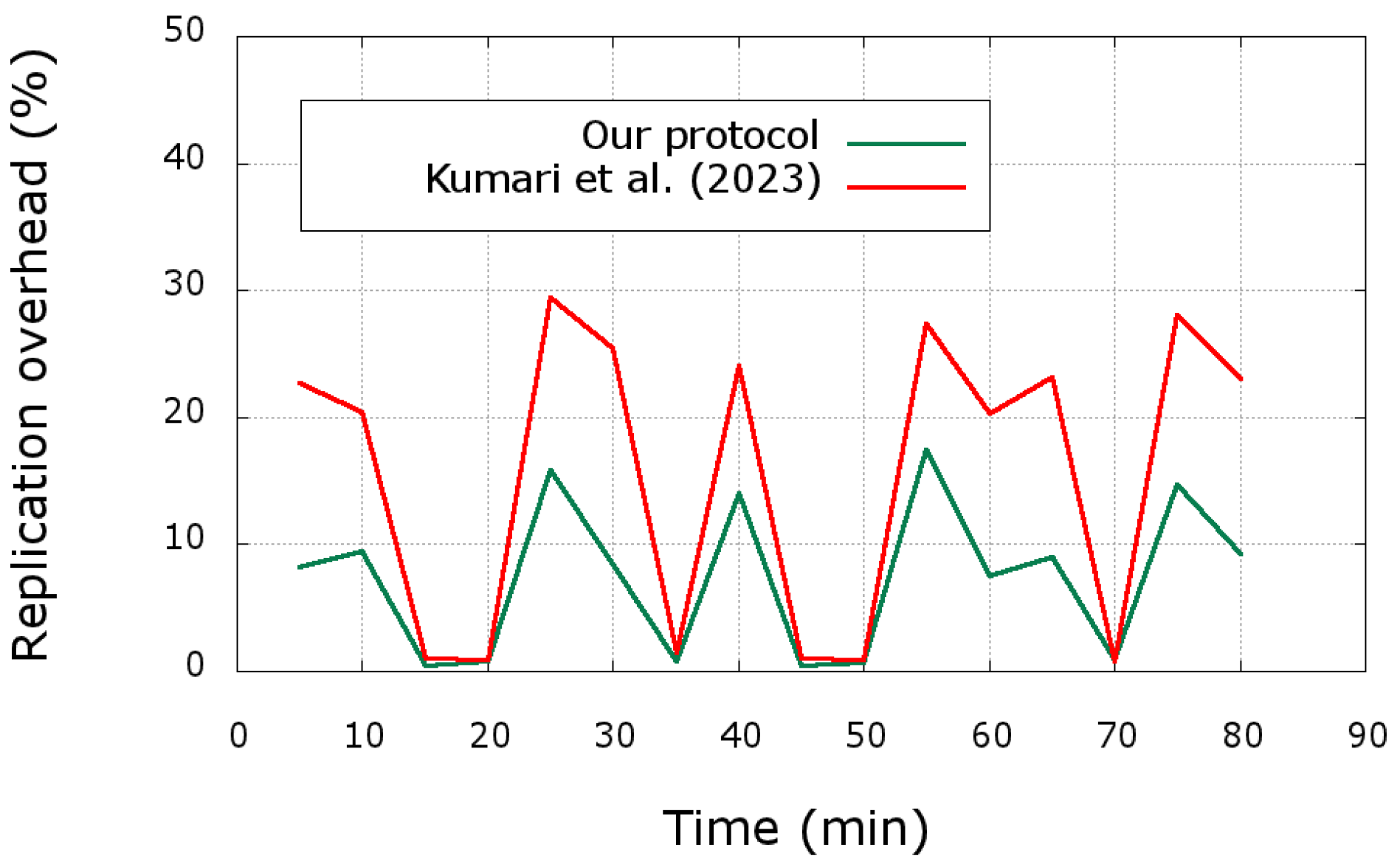

35] also uses the replication mechanism to manage fault tolerance, we compare its replication overhead with ours in

Figure 12. The observation in this case is that the maximum replication overhead in our scenario is around 18%, which is less than the 30% of the work presented by Kumari et al. [

35] Note that in both cases, the replication overhead is 0% each time the PMS is faulty. Moreover, each time a PMS is restored from a fault, the replication overhead significantly increases, which is normal, since the PMS and the SMS need to synchronize to have the same data stored on both servers.

4.3. Discussion

The main challenge of implementing the architecture that we have proposed was to find a way to combine suited tools to make it works at different level of the architecture. The proposed fault-tolerant and secured system, based on an MEC architecture and integrating technologies such as SDN, demonstrates great adaptability to handle simultaneous and diverse threats thanks to a combination of multilayer detection, signatures and anomalies, and dynamic update of security rules. It is capable of mitigating DDoS attacks by redirecting malicious traffic, blocking malware and ransomware through predefined signatures, and detecting zero-day attacks or insider threats through behavioral analysis. The system then adapts to new threats by integrating third-party security systems (IDSs/IPSs) and updating rules in real-time, while guaranteeing high availability thanks to dynamic network reconfiguration and isolation of compromised segments. This approach ensures robust security and business continuity in critical environments such as IoMT systems, where the protection of sensitive data and responsiveness are essential. Furthermore, fault-tolerant management ensures that the system continues to provide high-quality service, even in the presence of faults in some MEC servers. However, we believe that the use of blockchain technologies or artificial intelligence approaches can help to strengthen the security and privacy of our proposed scheme.