A Block-Coupled Finite Volume Method for Incompressible Hyperelastic Solids

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Block-coupled solution procedure: Instead of using a segregated solution procedure, in which displacement increment components and the pressure increment are solved separately, a block-coupled system of linear algebraic equations (representing the discretised momentum and pressure increment equations) is solved for displacement and pressure increments simultaneously. This leads to a more robust and efficient solution process, as there is no need to apply user-defined under-relaxation to the displacement and pressure increments. The proposed block-coupled solution procedure is based on the procedure proposed by Professor M. Darwish and collaborators [9,10] for the solution of laminar incompressible flow problems on collocated unstructured FV grids. Later, a similar algorithm was implemented [11,12] in the OpenFOAM framework [13], which serves as the starting point for the implementation of an algorithm for solving incompressible elastic/hyperelastic solid deformations in this work.

- Temporal discretisation: Emphasis is placed on the temporal accuracy of the model, as the ultimate objective is its application to fluid–structure interaction simulations in vascular flows. Four commonly used temporal discretisation schemes are implemented and tested, each incorporating a temporally consistent Rhie–Chow interpolation [14].

- Improved treatment of traction boundaries—Along the portions of the discretised spatial domain boundary where traction is specified, the displacement increment is calculated using the cell-face normal component obtained from the solution of the continuity (pressure increment) equation, while the remaining components are reconstructed using the selected constitutive equation. This approach provides substantially higher accuracy at the traction boundaries compared with the second-order extrapolation used in [4].

- Extended material applicability: The proposed FV solver is applicable to both linear elastic bodies and nonlinear hyperelastic materials described by arbitrary constitutive equations, with emphasis on constitutive relations used for modelling arterial walls and heart tissue (for example, Holzapfel-Gasser-Ogden (HGO) model [15] and Guccione model [16]).

2. Mathematical Model

2.1. Constitutive Equations

2.2. Resulting Set of Equations for Incompressible Solid

2.3. Initial and Boundary Conditions

3. Numerical Model

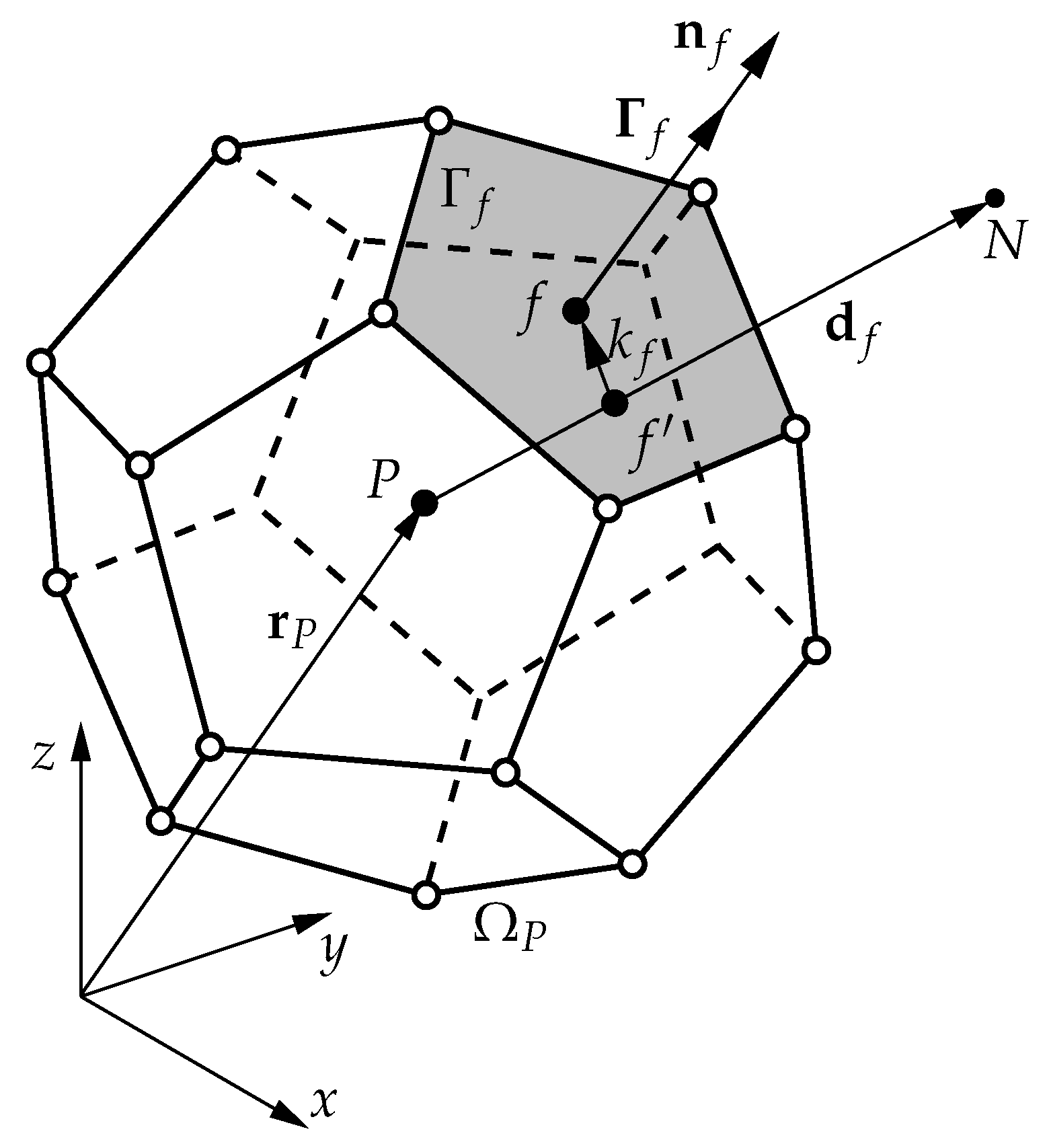

3.1. Solution Domain Discretisation

3.2. Governing Equations Discretisation

3.2.1. Momentum Equation Discretisation

- Euler scheme

- Crank-Nicolson scheme

- backward scheme

- composite scheme [25]: a simplified version is implemented here, where the Crank-Nicolson and backward schemes are applied alternately.

3.2.2. Discretised Pressure Equation

3.2.3. Calculation of Gradients

3.2.4. Mesh Vertices Displacement

3.2.5. Initial and Boundary Conditions

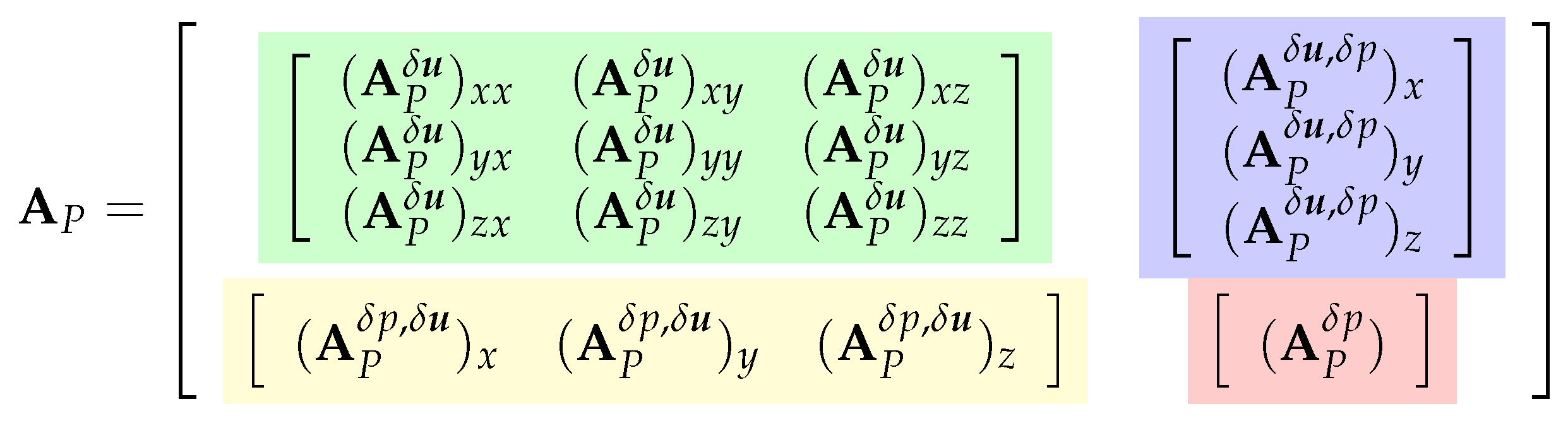

3.2.6. Final Block-Coupled System of Linear Algebraic Equations

3.3. Solution Procedure

| Algorithm 1 Block-coupled solution procedure |

|

4. Results

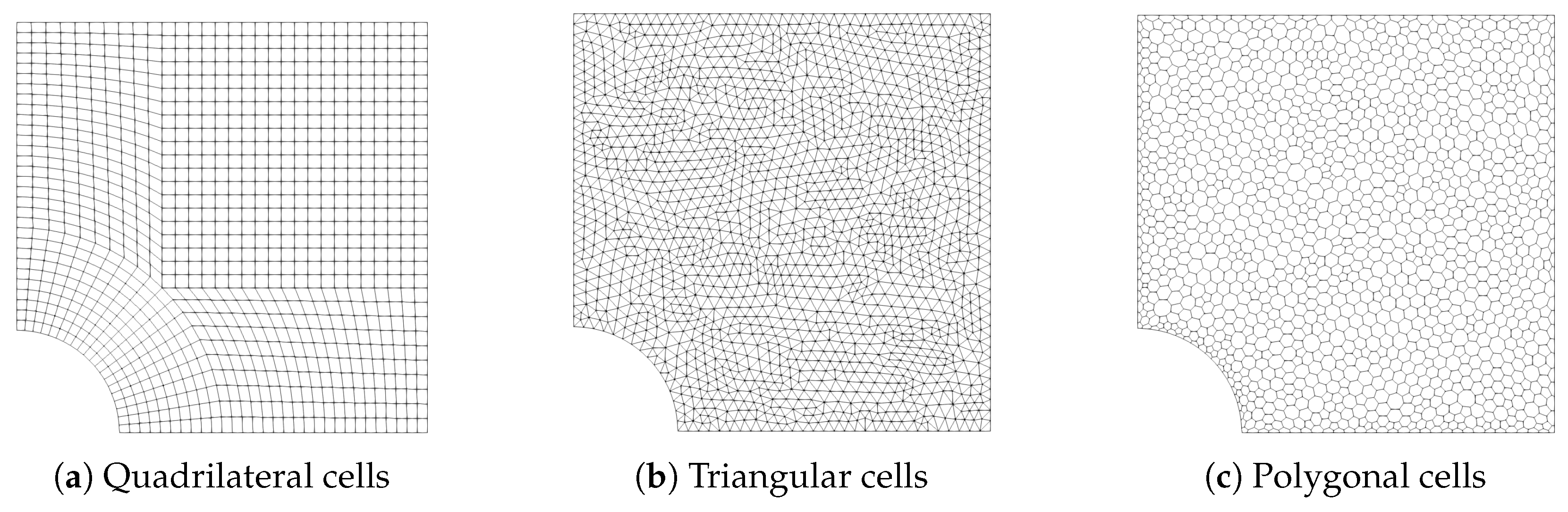

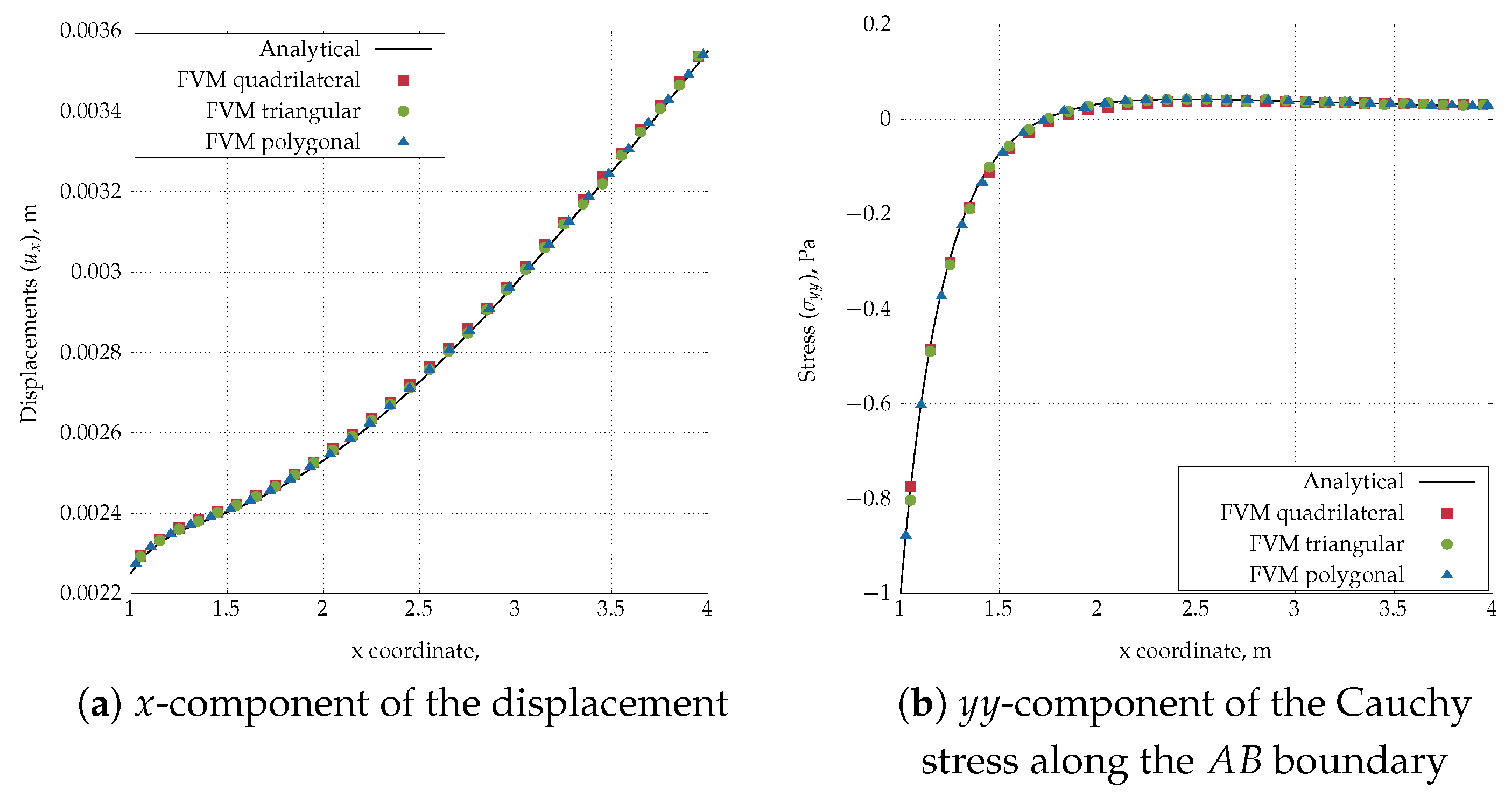

4.1. Infinite Plate with a Circular Hole Subjected to Uniform Tension

4.2. Uniaxial Extension and Simple Shear Tests

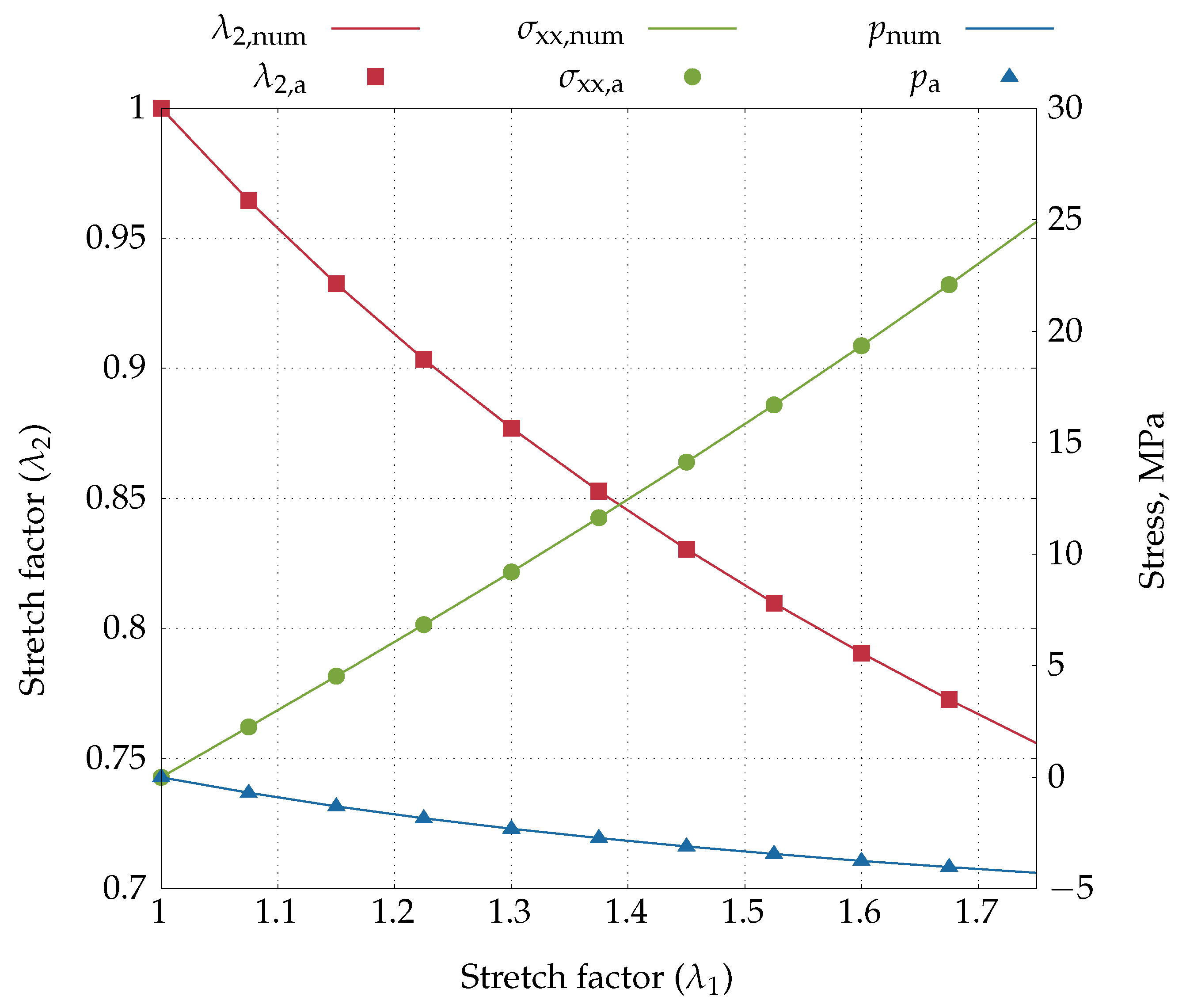

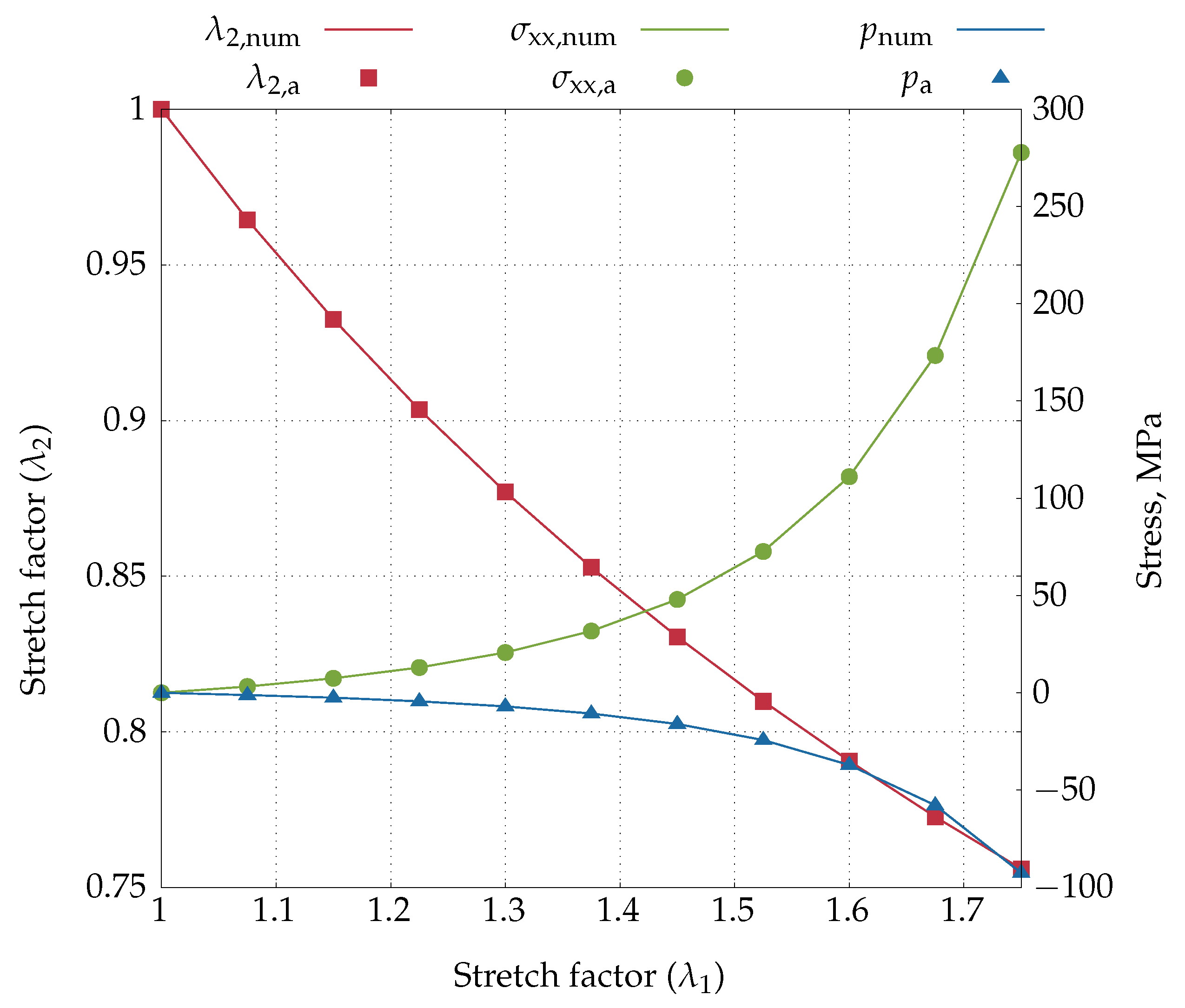

4.2.1. Uniaxial Extension Test

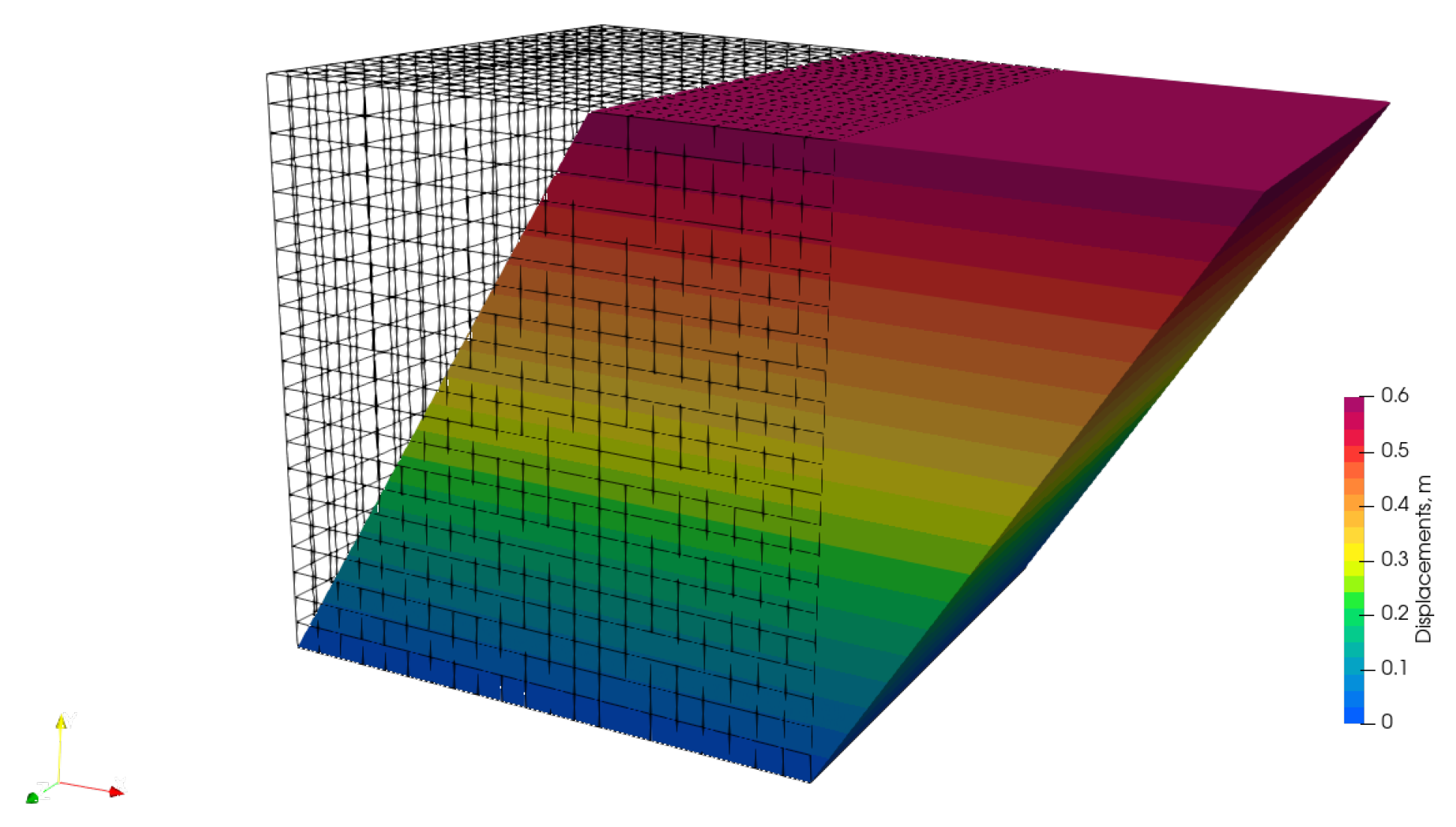

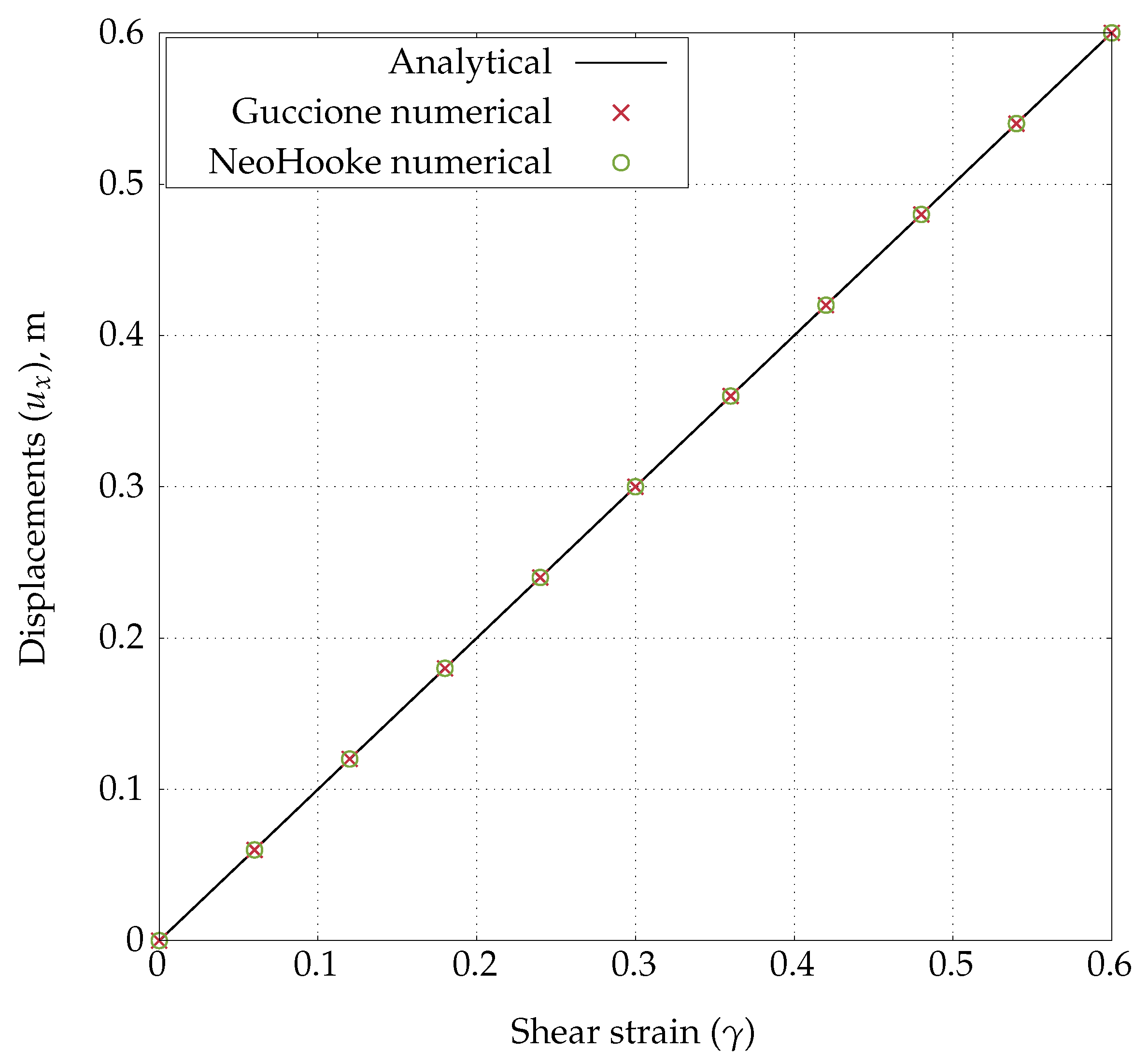

4.2.2. Simple Shear Test

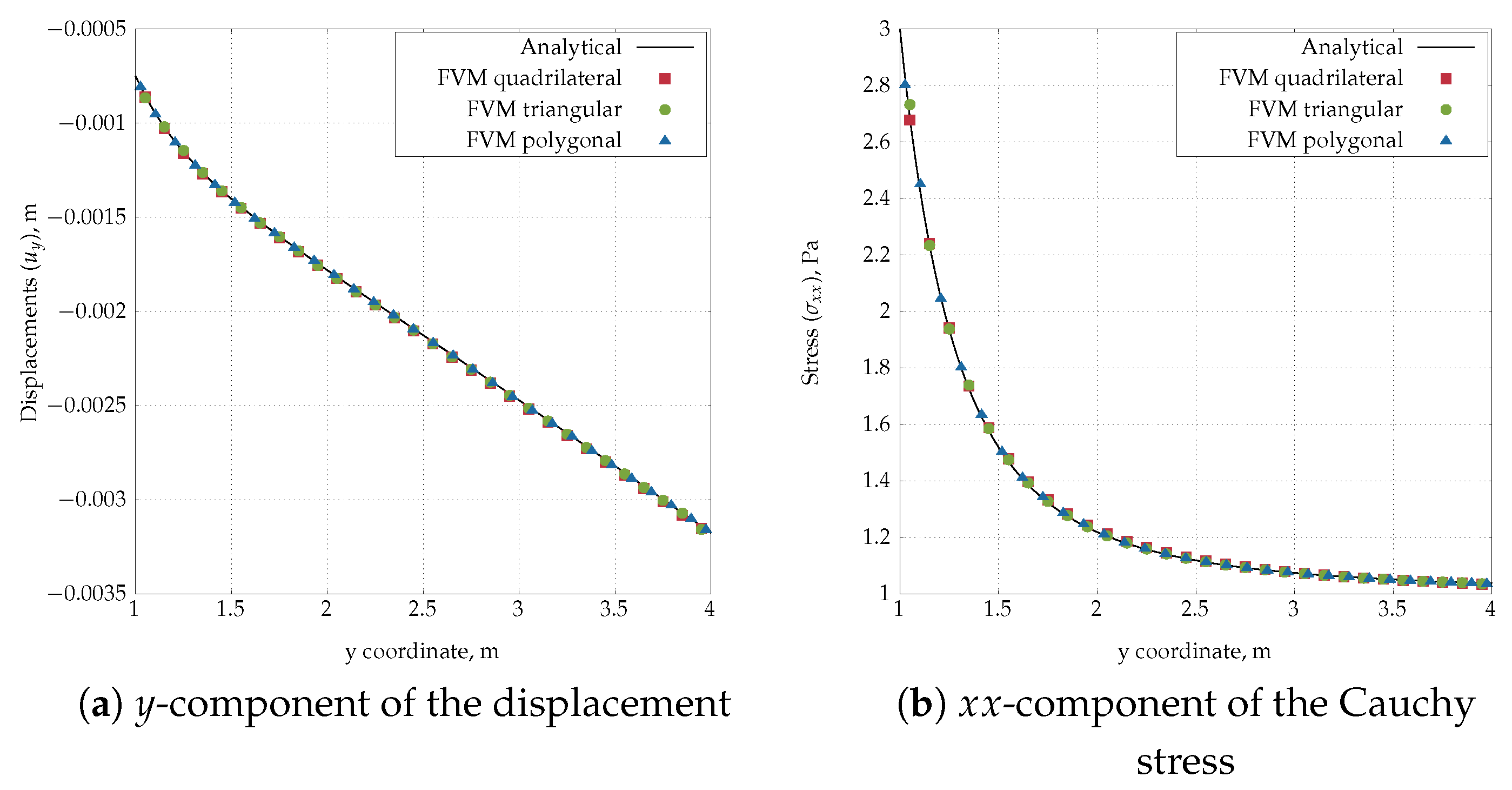

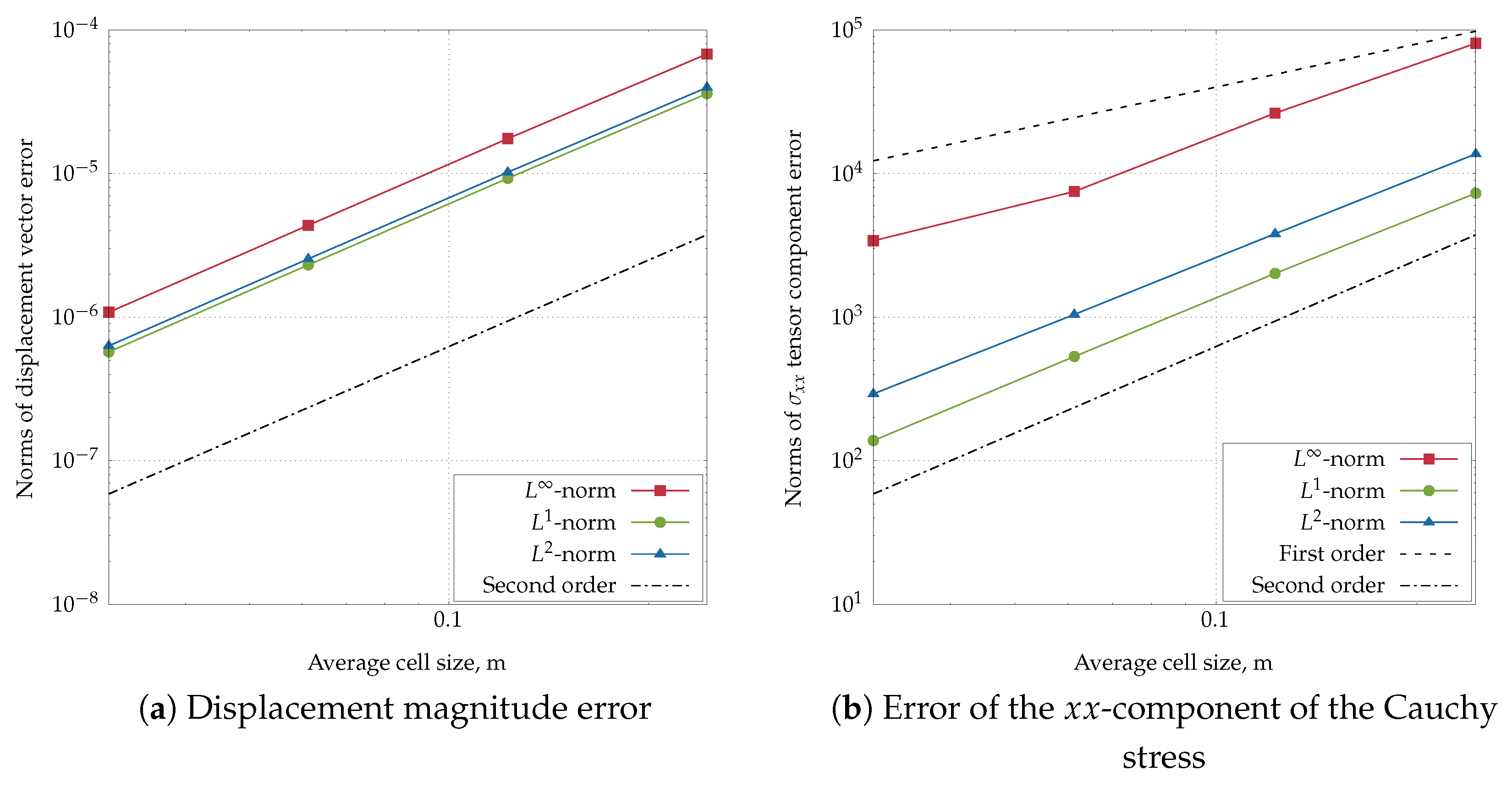

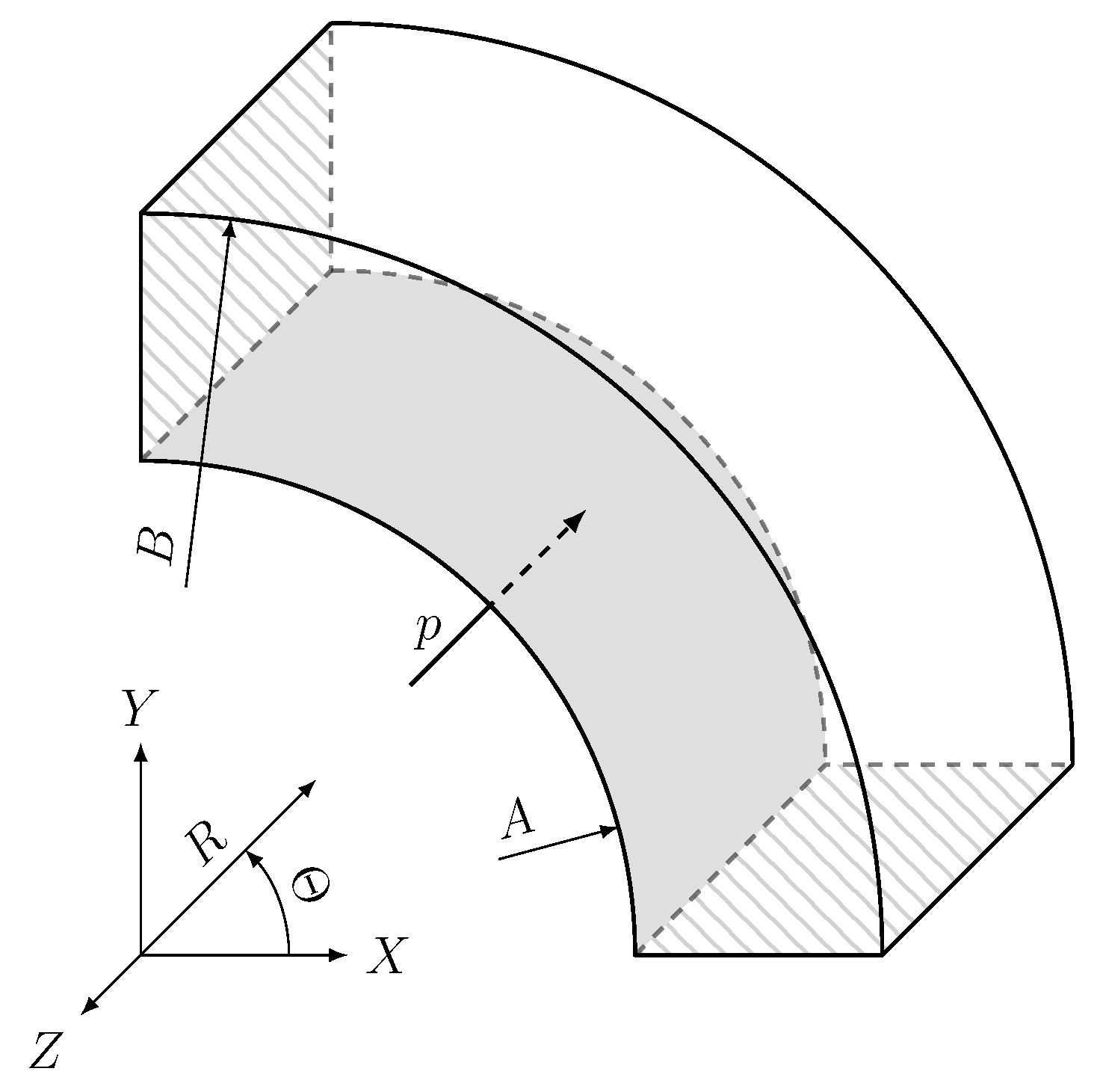

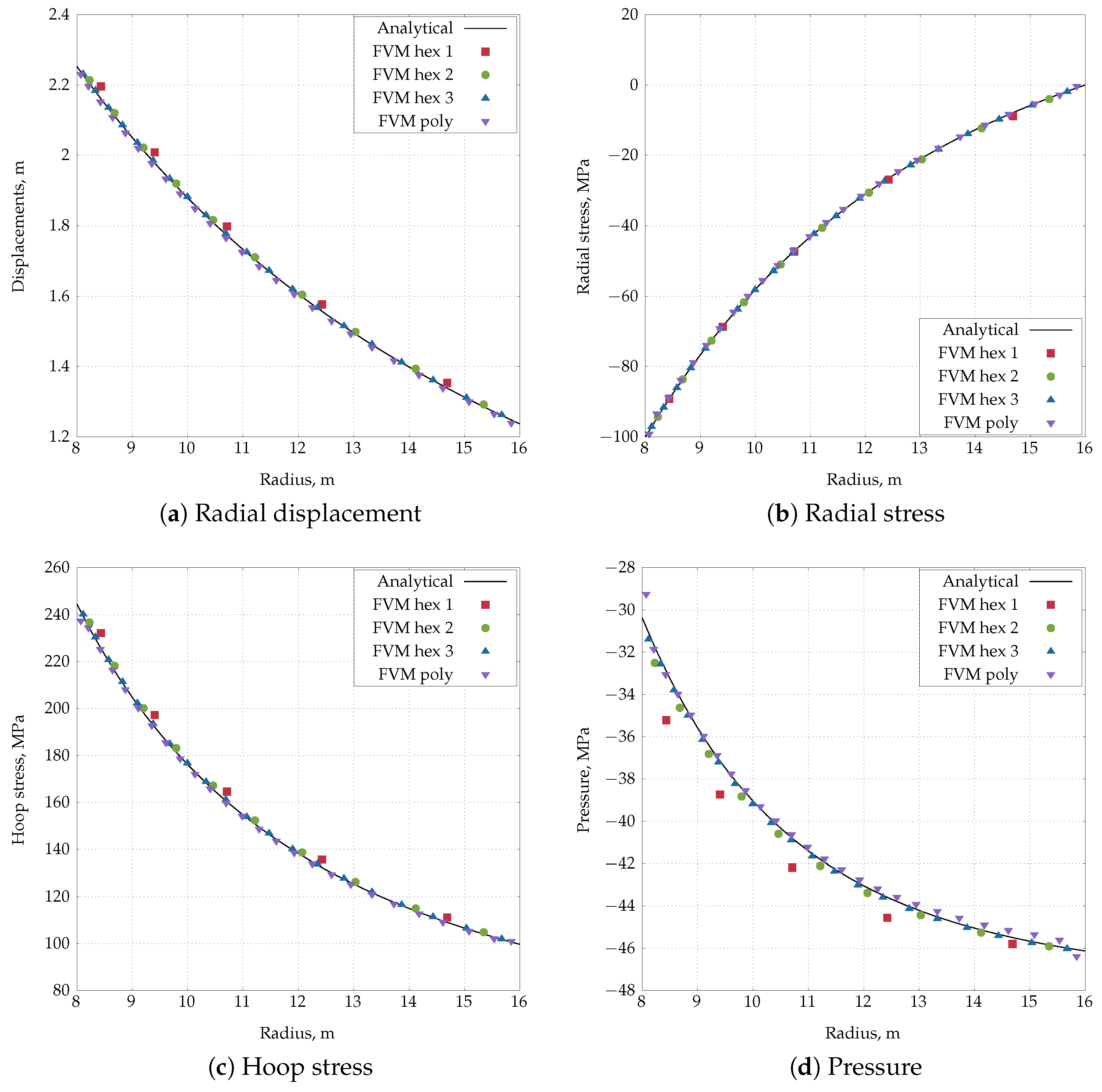

4.3. Inflation of a Thick-Wall Cylinder

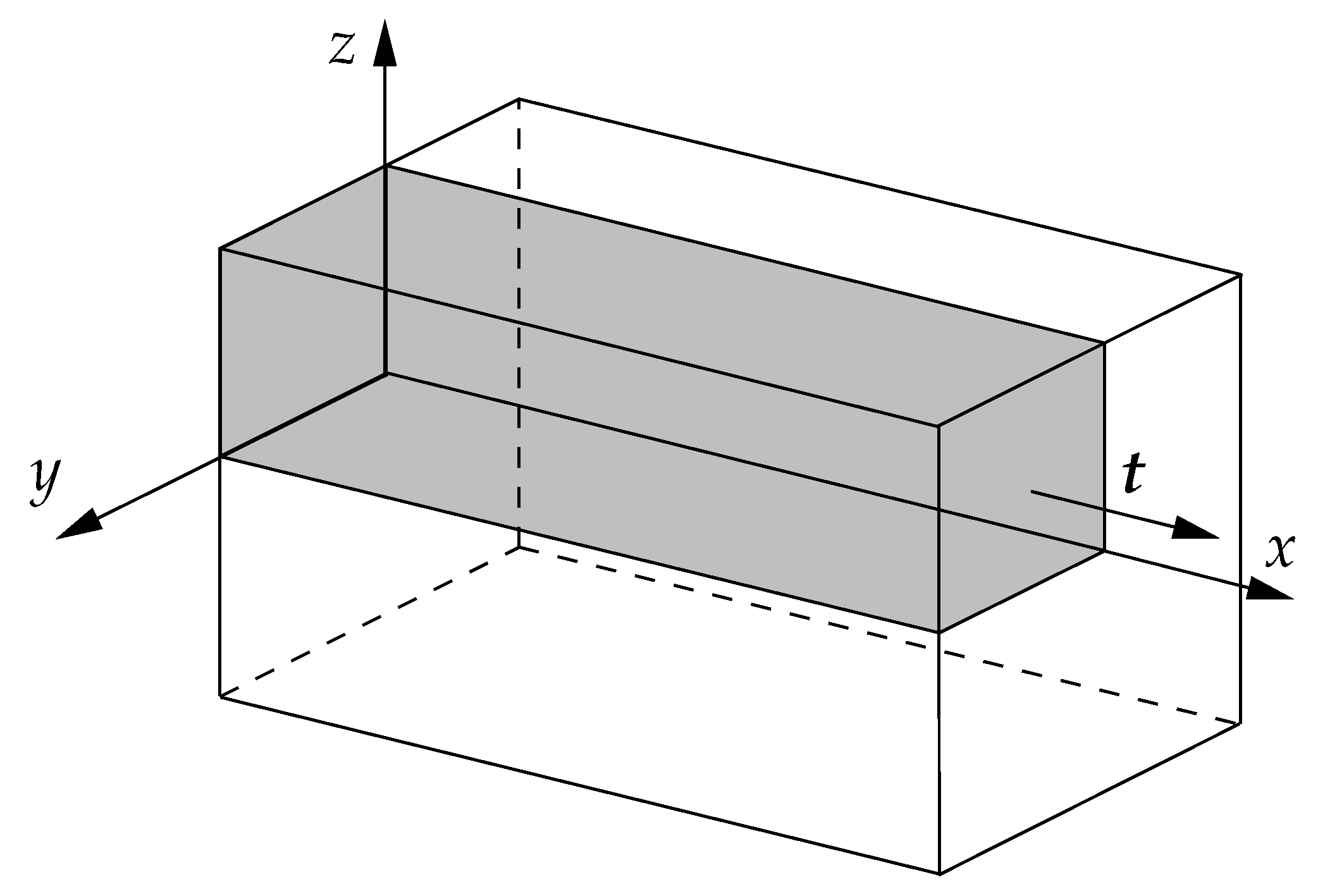

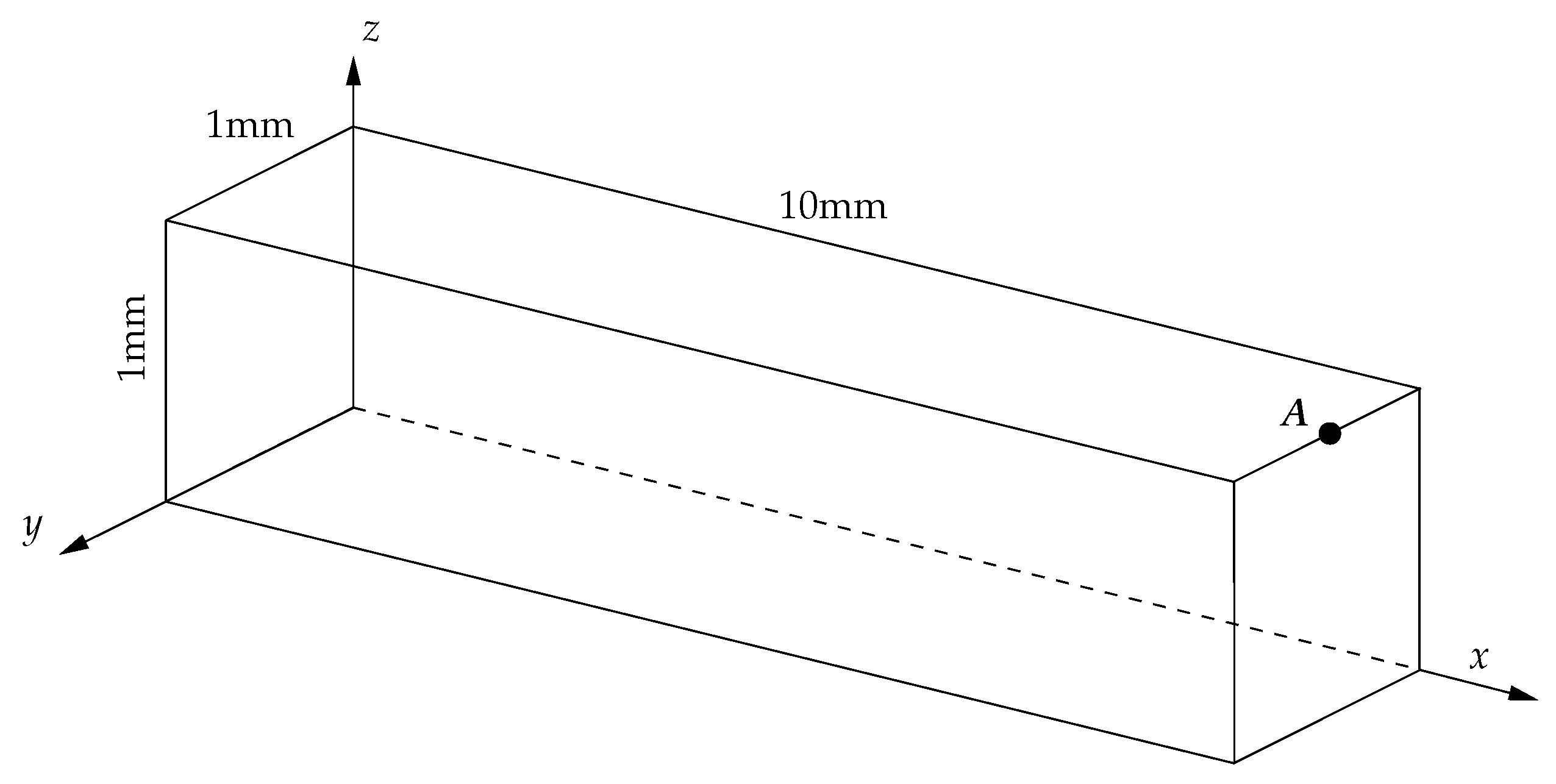

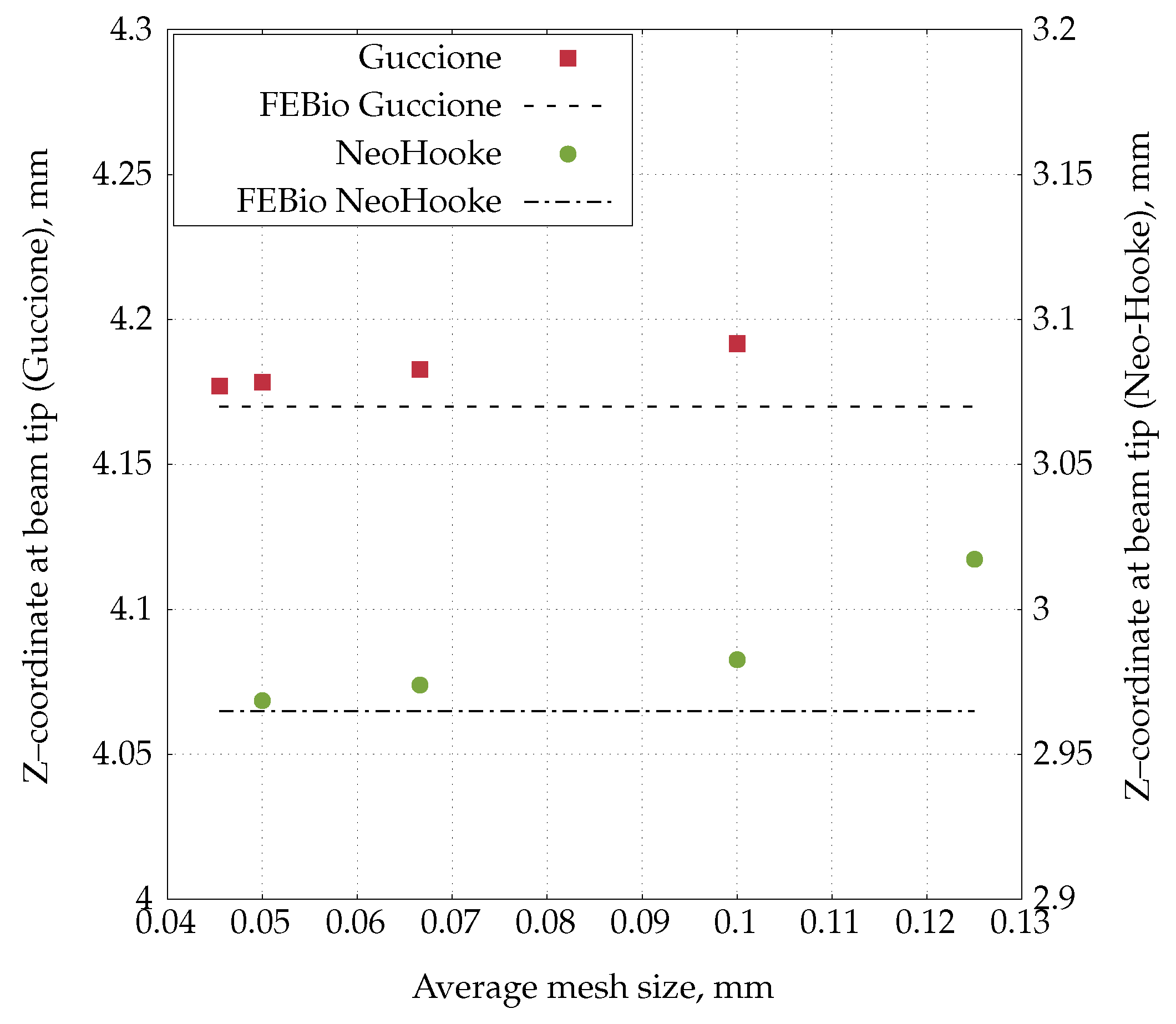

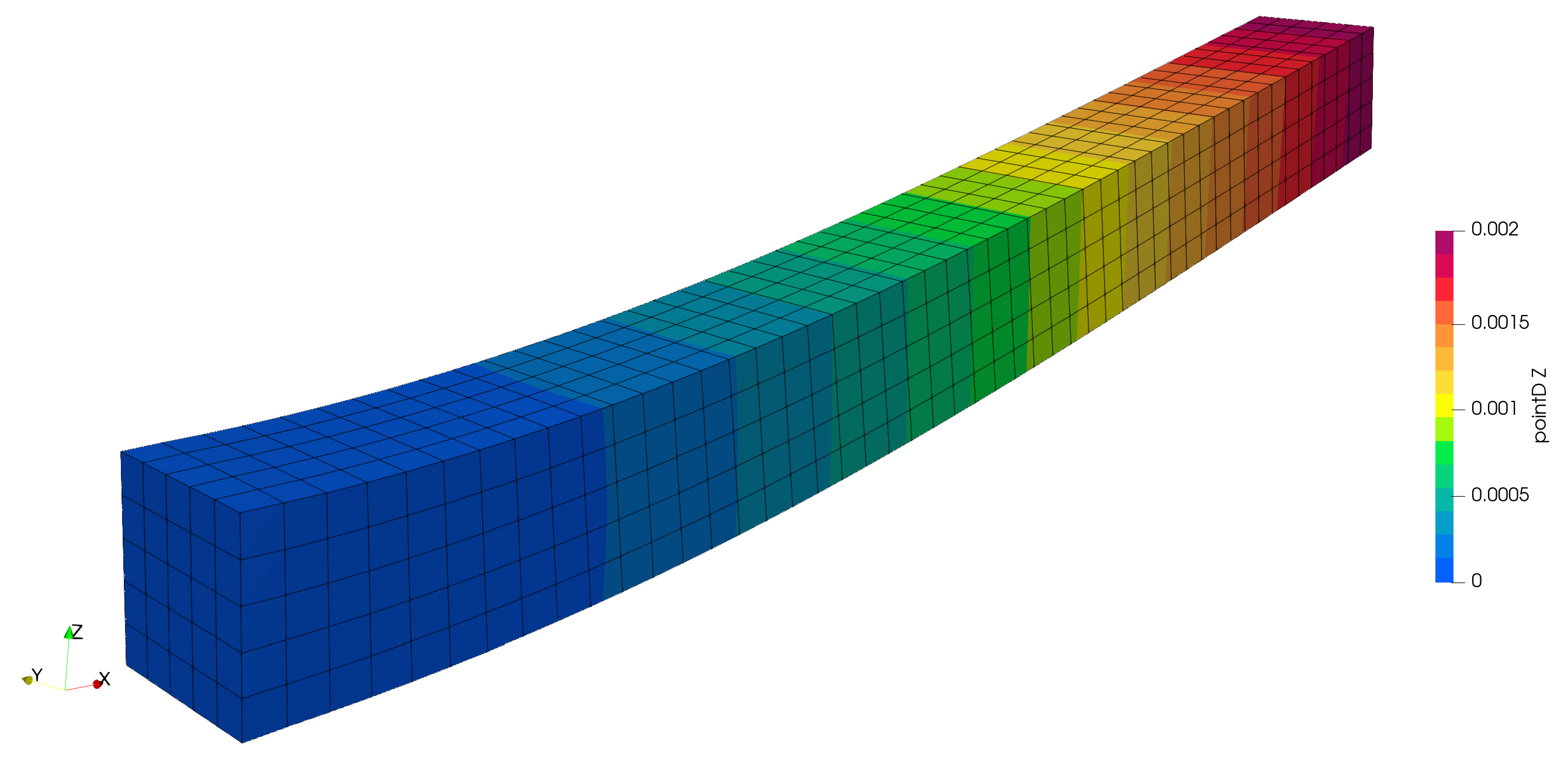

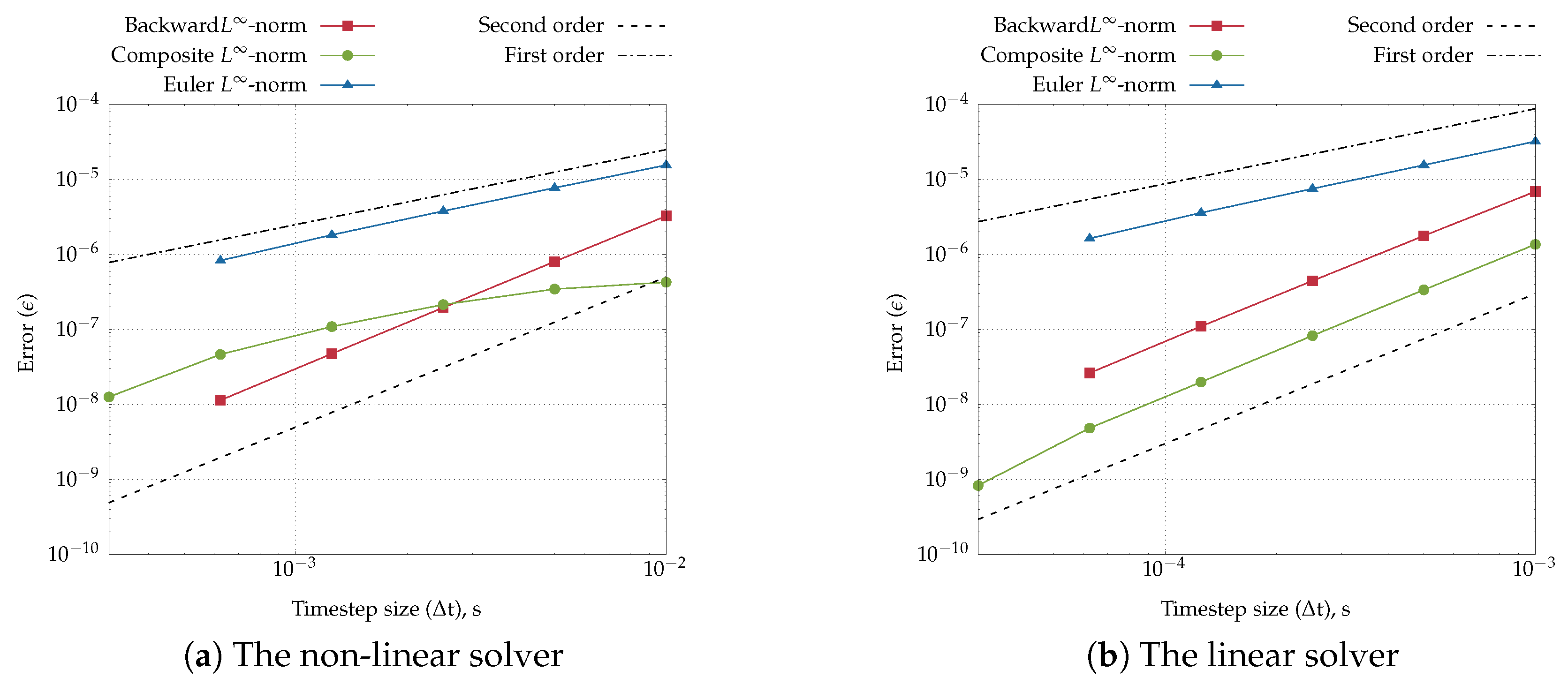

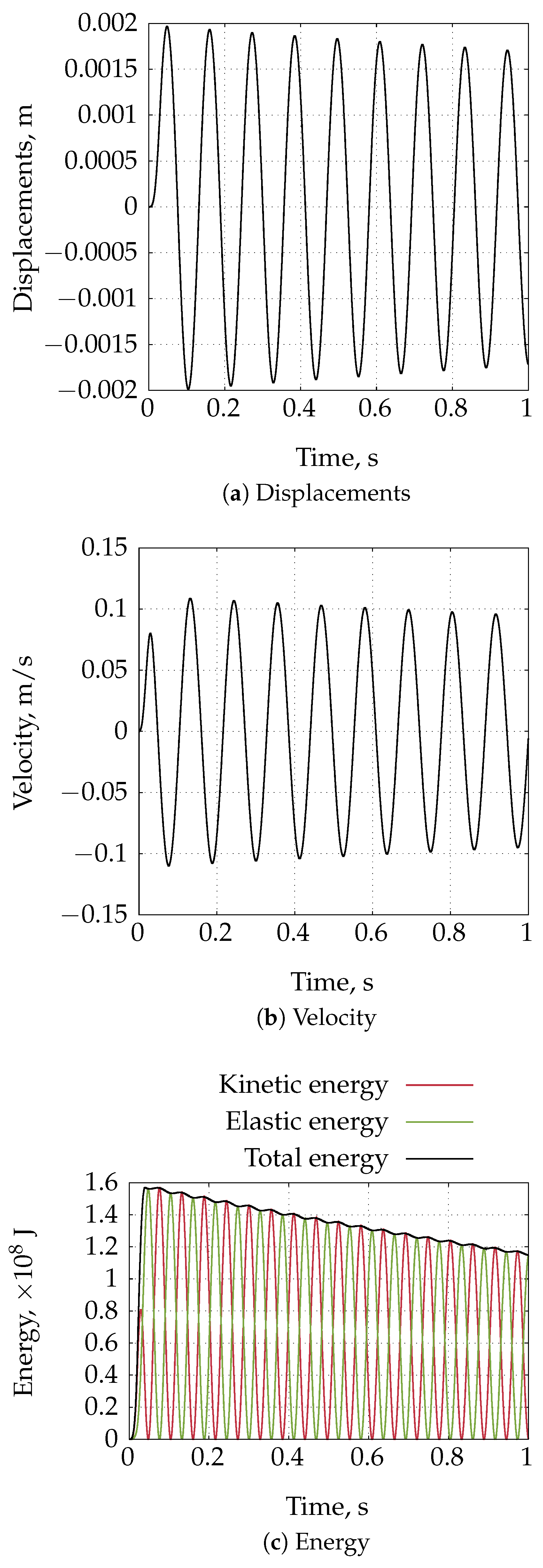

4.4. Heart Tissue Beam

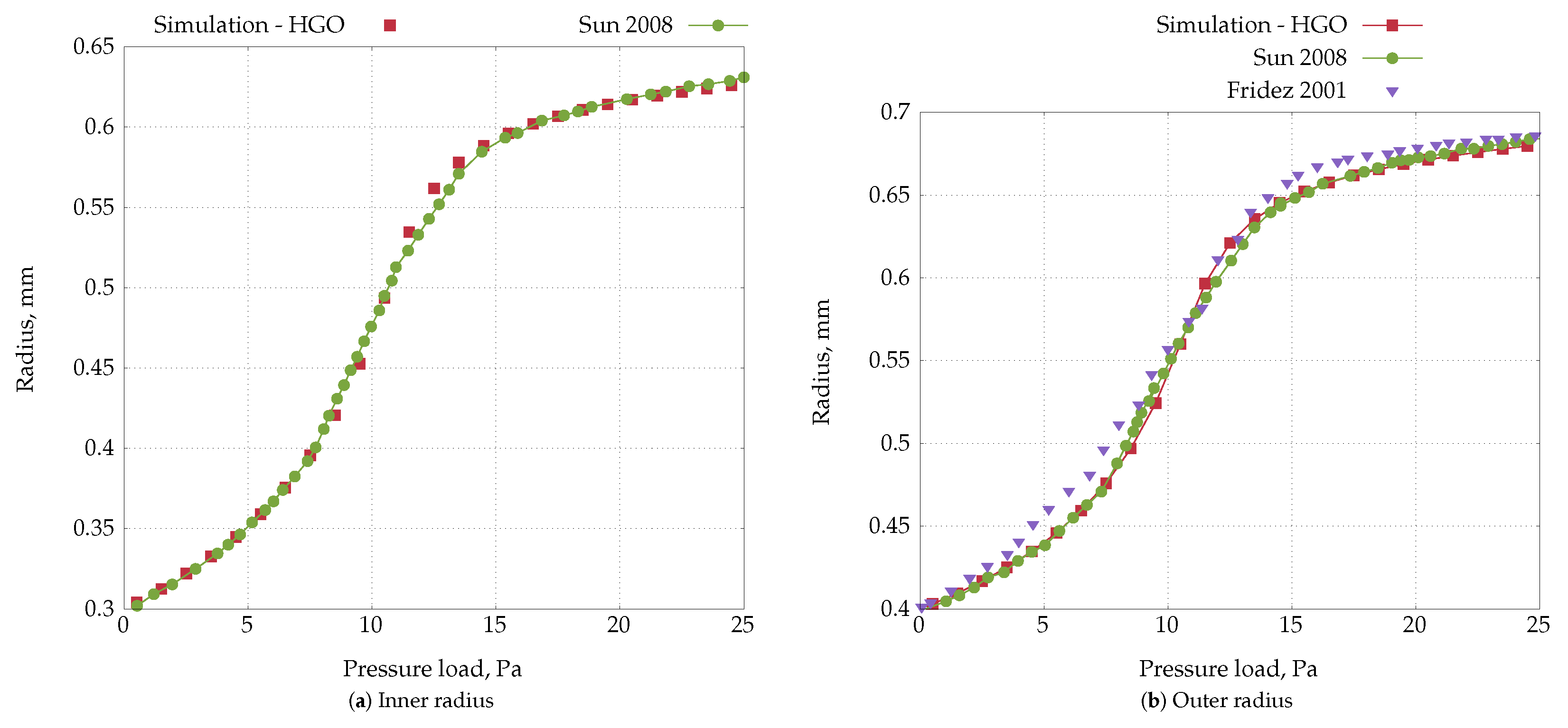

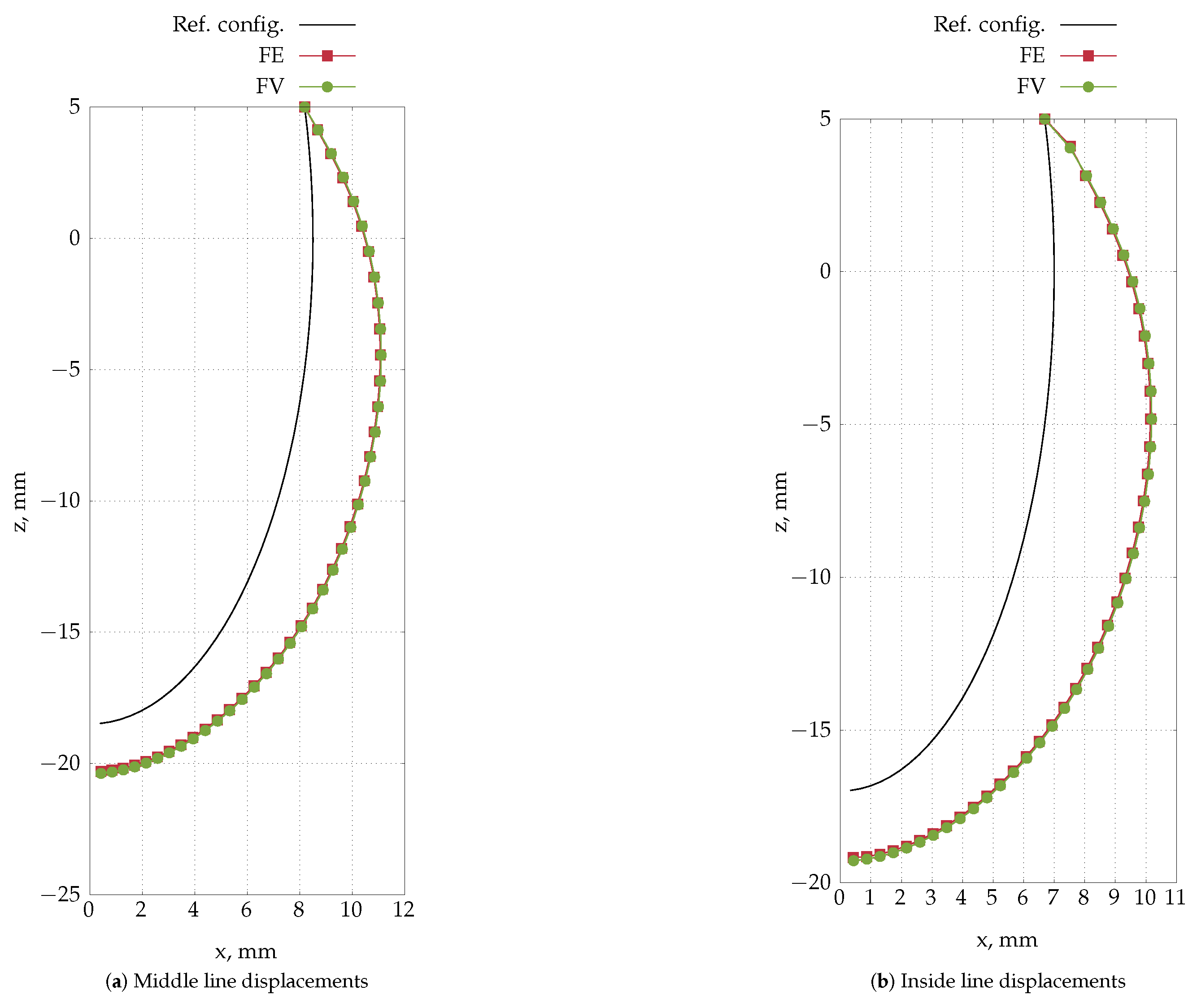

4.5. Inflation of a Rat Carotid Artery

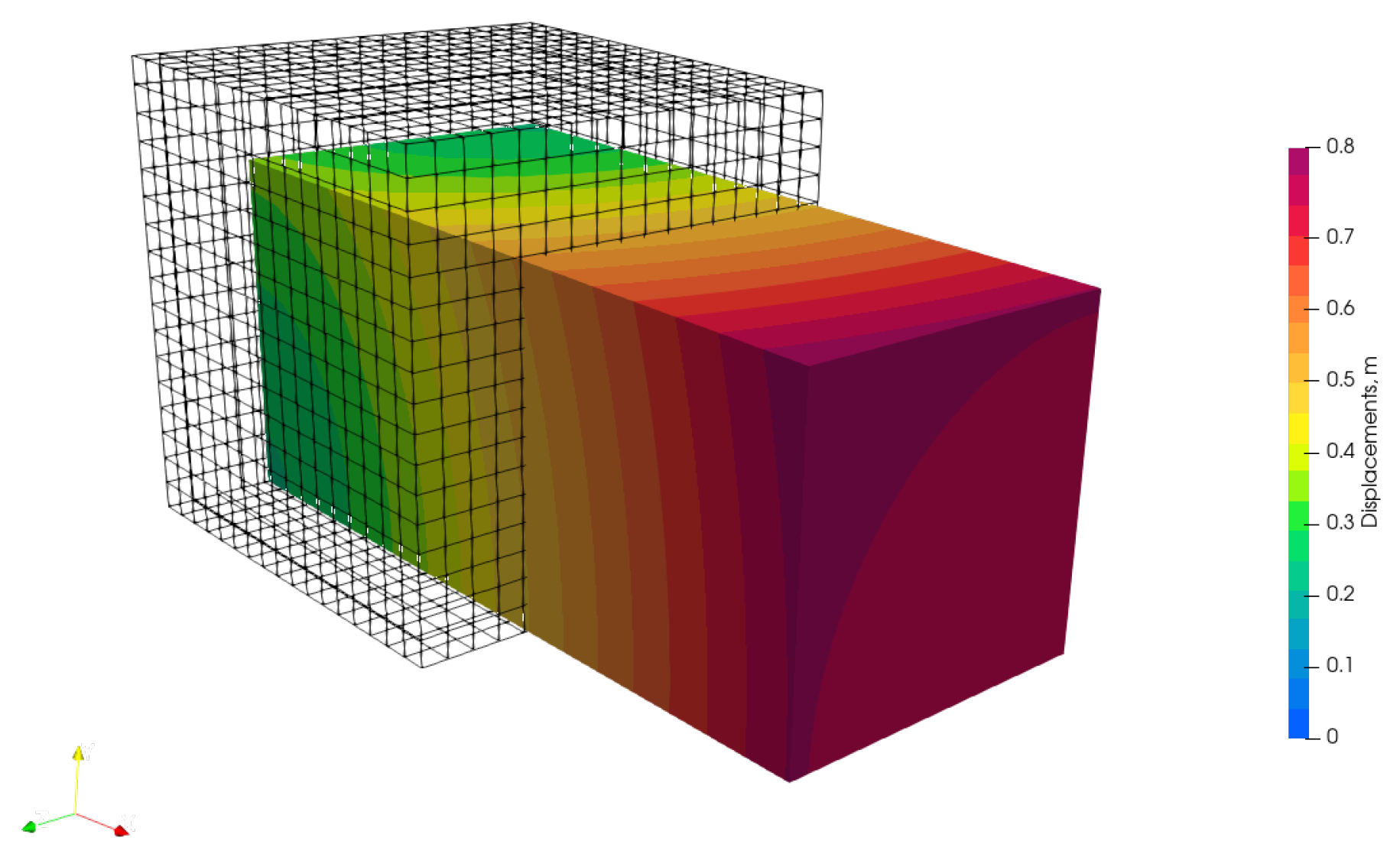

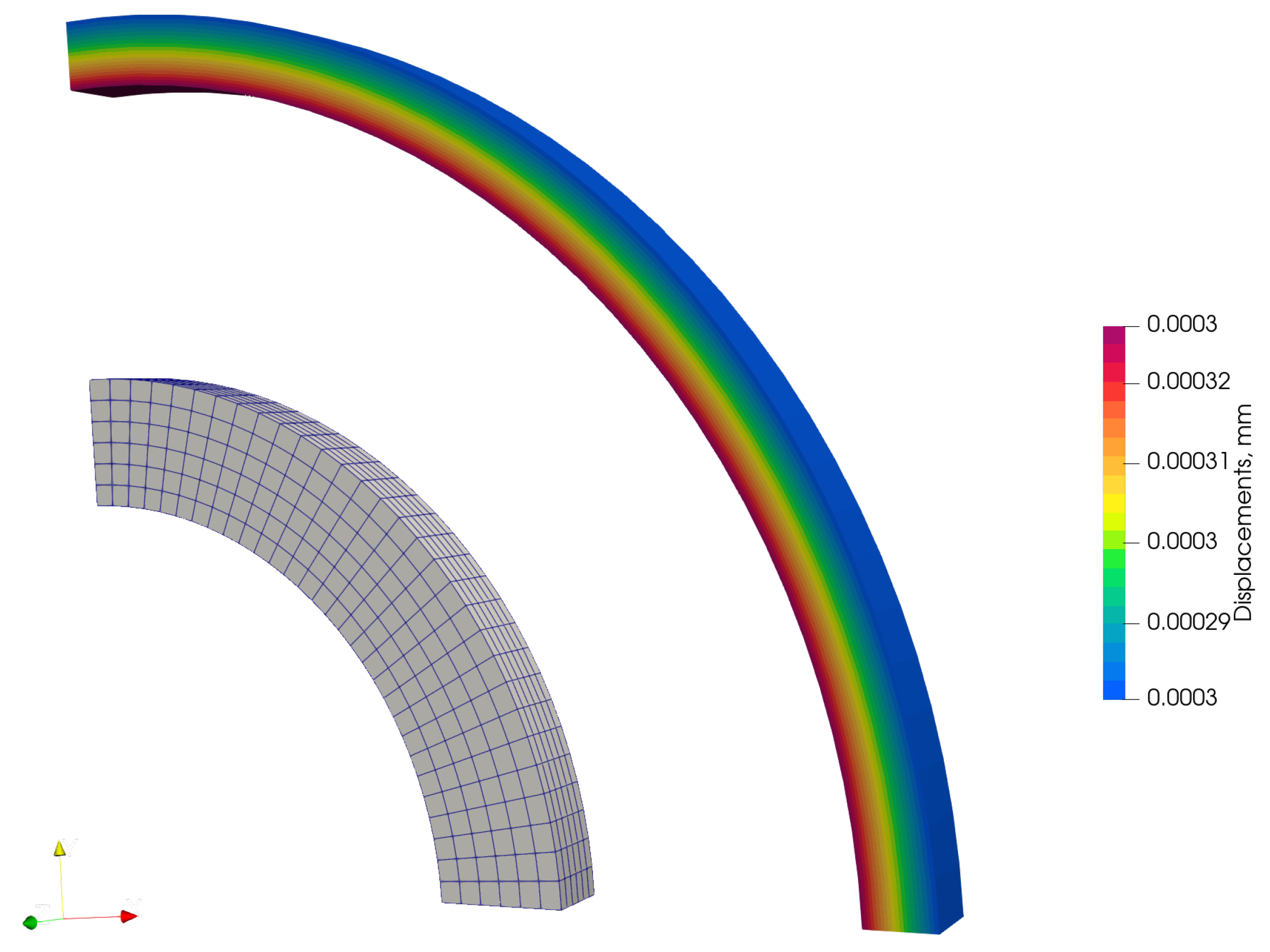

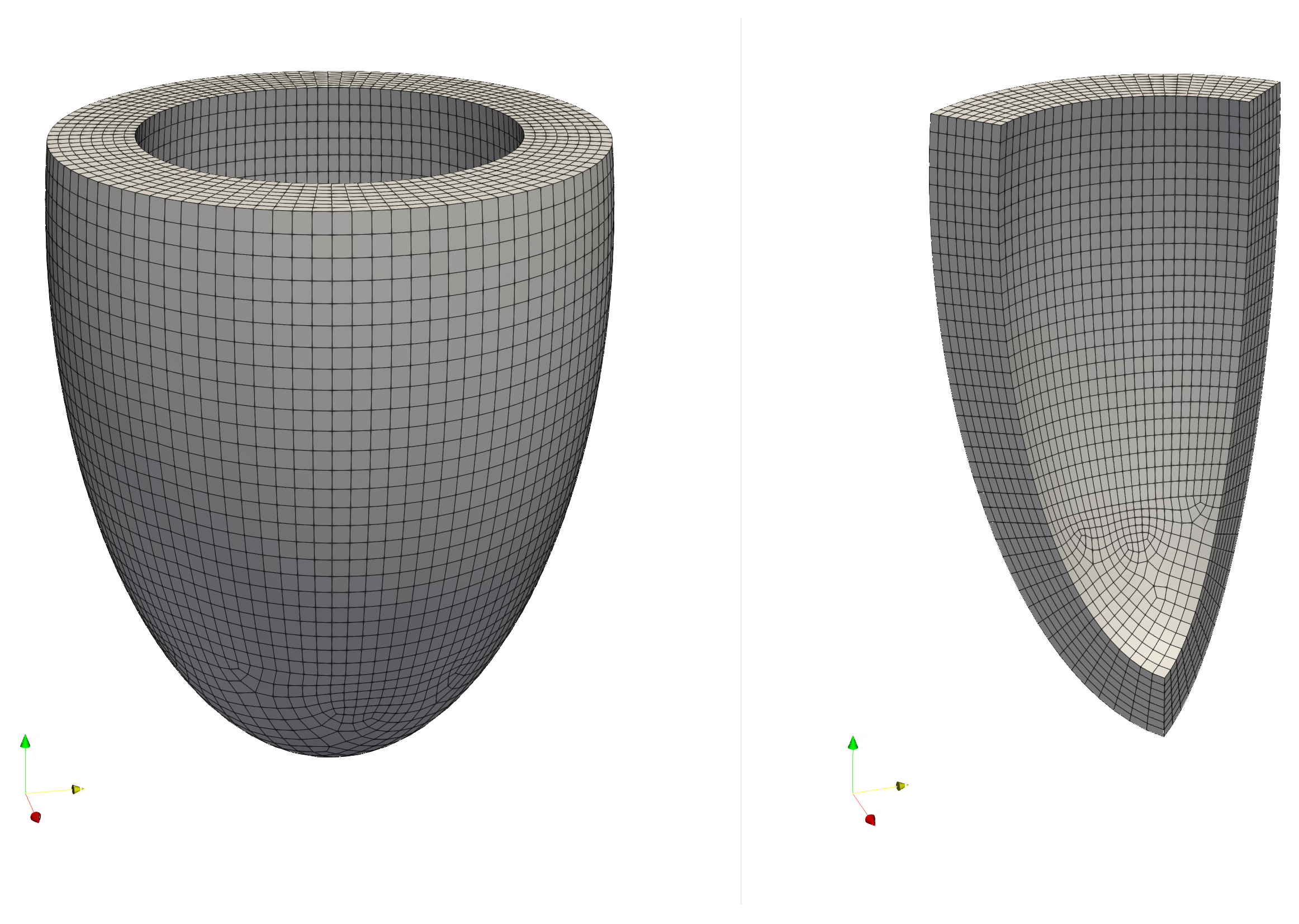

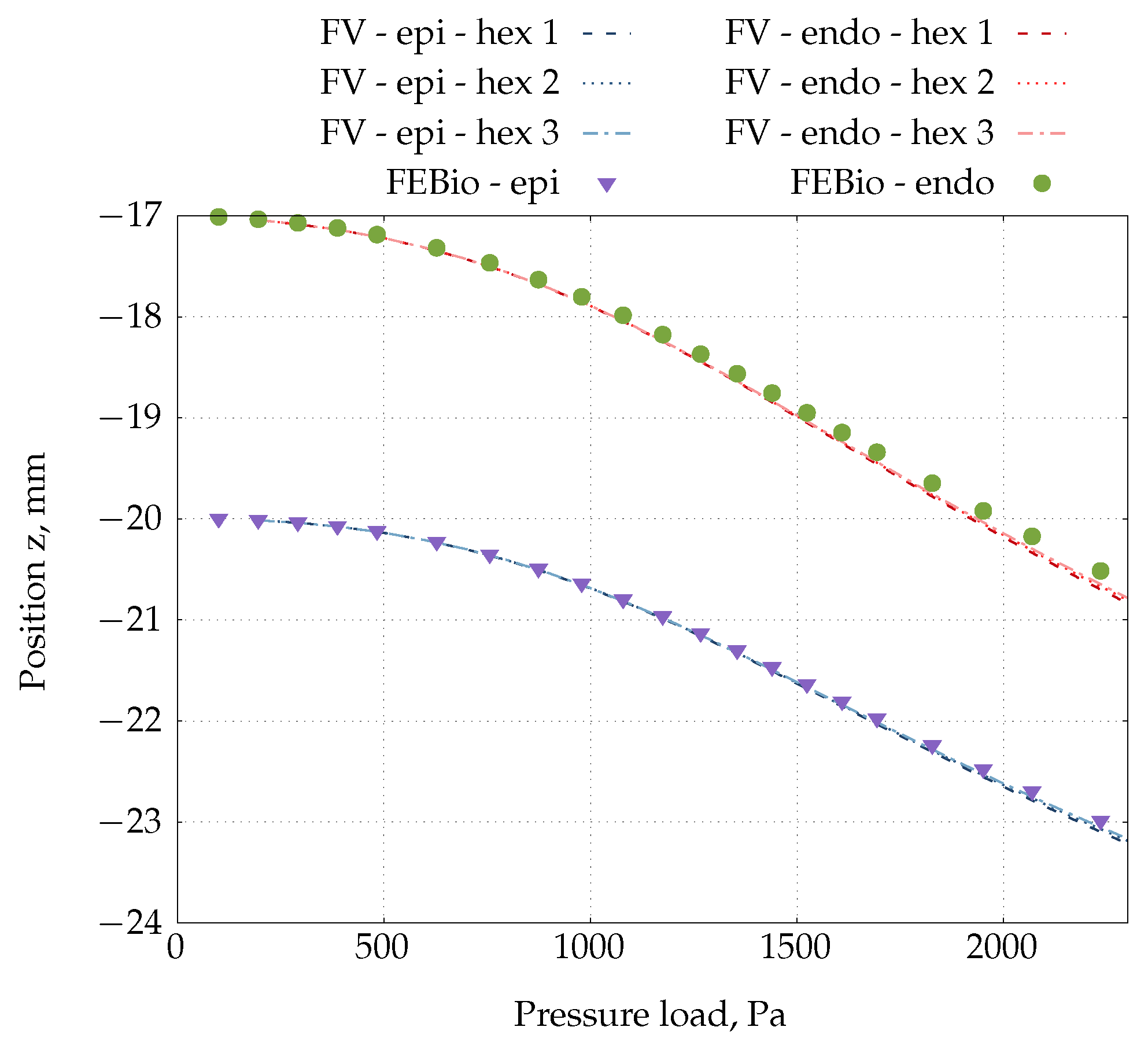

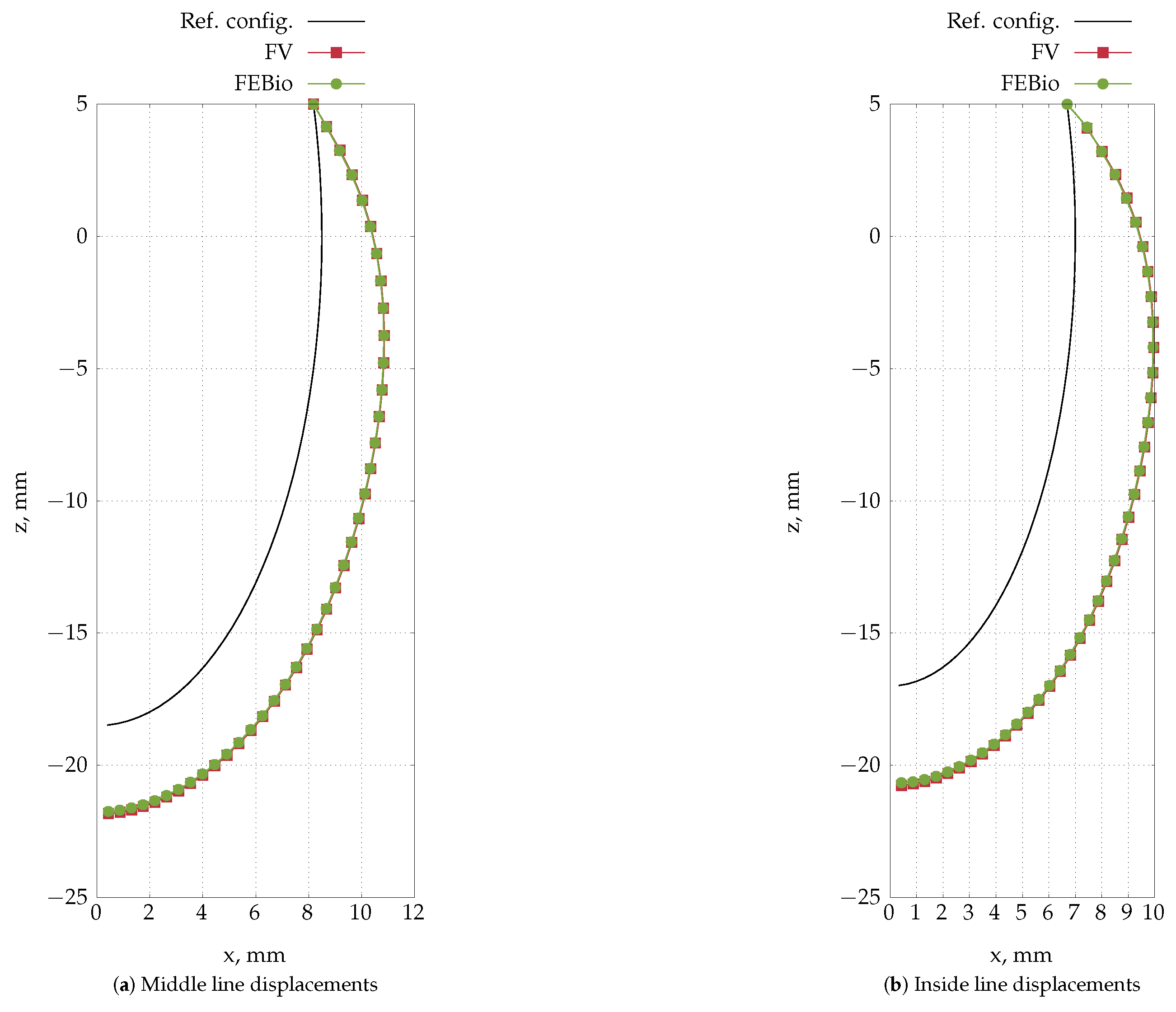

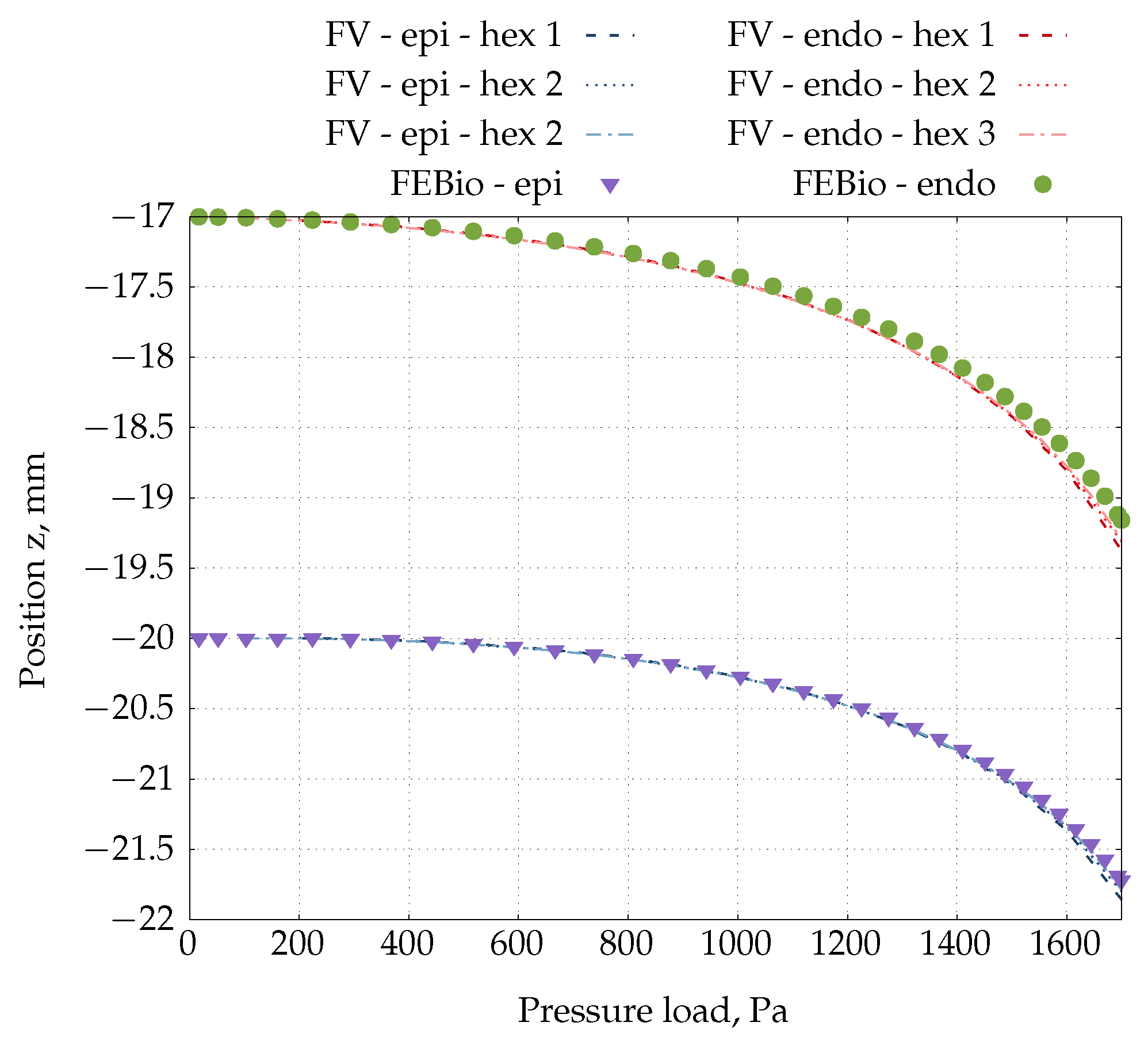

4.6. Inflation of an Idealised Ventricle

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FE | Finite Element |

| CSM | Computational Solid Mechanics |

| FV | Finite Volume |

| SIMPLE | Semi-Implicit Method for Pressure Linked Equations |

| FSI | Fluid–Structure Interaction |

| CV | Control Volume |

| HGO | Holzapfel–Gasser–Ogden |

| CRC | Consistent Rhie–Chow |

Appendix A. Instantaneous Shear Modulus Approximation

Appendix B. Linear System Coefficients

Appendix C. Consistent Rhie–Chow Interpolation

Appendix D. Material Laws

Appendix D.1. HGO Model

Appendix D.2. Guccione Model

Appendix E. Pressurised Cylinder Equations

References

- Sussman, T.; Bathe, K.J. A finite element formulation for nonlinear incompressible elastic and inelastic analysis. Comput. Struct. 1987, 26, 357–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardiff, P.; Demirdžić, I. Thirty Years of the Finite Volume Method for Solid Mechanics. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2021, 28, 3721–3780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheel, M.A. A mixed finite volume formulation for determining the small strain deformation of incompressible materials. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 1999, 44, 1843–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijelonja, I.; Demirdžić, I.; Muzaferija, S. A finite volume method for large strain analysis of incompressible hyperelastic materials. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 2005, 64, 1594–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijelonja, I.; Demirdžić, I.; Muzaferija, S. A finite volume method for incompressible linear elasticity. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2006, 195, 6378–6390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijelonja, I.; Demirdžić, I.; Muzaferija, S. Mixed finite volume method for linear thermoelasticity at all Poisson’s ratios. Numer. Heat Transf. Part A Appl. 2017, 72, 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patankar, S.; Spalding, D. A calculation procedure for heat, mass and momentum transfer in three-dimensional parabolic flows. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1972, 15, 1787–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhie, C.M.; Chow, W.L. Numerical study of the turbulent flow past an airfoil with trailing edge separation. AIAA J. 1983, 21, 1525–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwish, M.; Sraj, I.; Moukalled, F. A coupled finite volume solver for the solution of incompressible flows on unstructured grids. J. Comput. Phys. 2009, 228, 180–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangani, L.; Alloush, M.M.; Lindegger, R.; Hanimann, L.; Darwish, M. A Pressure-Based Fully-Coupled Flow Algorithm for the Control Volume Finite Element Method. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uroić, T.; Jasak, H. Block-selective algebraic multigrid for implicitly coupled pressure-velocity system. Comput. Fluids 2018, 167, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C.; Vukčević, V.; Uroić, T.; Simoes, R.; Carneiro, O.; Jasak, H.; Nóbrega, J. A coupled finite volume flow solver for the solution of incompressible viscoelastic flows. J. Non-Newton. Fluid Mech. 2019, 265, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, H.G.; Tabor, G.; Jasak, H.; Fureby, C. A tensorial approach to computational continuum mechanics using object-oriented techniques. Comput. Phys. 1998, 12, 620–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, P.; Denner, F.; Abdol-Azis, M.H.; Marquis, A.; van Wachem, B.G. Unified formulation of the momentum-weighted interpolation for collocated variable arrangements. J. Comput. Phys. 2018, 375, 177–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzapfel, G.A.; Gasser, T.C.; Ogden, R.W. A new constitutive framework for arterial wall mechanics and a comparative study of material models. J. Elast. 2000, 61, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guccione, J.M.; McCulloch, A.D.; Waldman, L.K. Passive material properties of intact ventricular myocardium determined from a cylindrical model. J. Biomech. Eng. 1991, 113, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardiff, P.; Karač, A.; De Jaeger, P.; Jasak, H.; Nagy, J.; Ivanković, A.; Tuković, Ž. An open-source finite volume toolbox for solid mechanics and fluid-solid interaction simulations. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1808.10736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardiff, P.; Batistić, I.; Tuković, Ž. solids4foam: A toolbox for performing solid mechanics and fluid-solid interaction simulations in OpenFOAM. J. Open Source Softw. 2025, 10, 7407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirdžić, I.; Cardiff, P. Symmetry plane boundary conditions for cell-centred finite-volume continuum mechanics. Numer. Heat Transf. Part B Fundam. 2022, 83, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, M.; Peixoto, D.H.N. Comparative assessments of strain measures for nonlinear analysis of truss structures at large deformations. Eng. Comput. 2021, 39, 1621–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, D.H.N.; Greco, M.; Vasconcellos, D.B. A new family of strain tensors based on the hyperbolic sine function. Lat. Am. J. Solids Struct. 2024, 21, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcellos, D.B.; Greco, M. Reconciling the strain-stretching curve with the stress-strain diagram of a Hooke-like isotropic hyperelastic material using the Biot’s hyperbolic sine strain tensor. Lat. Am. J. Solids Struct. 2025, 22, 8362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuković, Ž.; Karač, A.; Cardiff, P.; Jasak, H.; Ivanković, A. OpenFOAM Finite Volume Solver for Fluid-Solid Interaction. Trans. FAMENA 2018, 42, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathe, K.J.; Baig, M.M.I. On a composite implicit time integration procedure for nonlinear dynamics. Comput. Struct. 2005, 83, 2513–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathe, K.J.; Noh, G.C. Insight into an implicit time integration scheme for structural dynamics. Comput. Struct. 2012, 98–99, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuković, Ž.; Perić, M.; Jasak, H. Consistent second-order time-accurate non-iterative PISO-algorithm. Comput. Fluids 2018, 166, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirdžić, I.; Muzaferija, S. Numerical method for coupled fluid flow, heat transfer and stress analysis using unstructured moving meshes with cells of arbitrary topology. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 1995, 125, 235–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, S.A.; Ellis, B.J.; Ateshian, G.A.; Weiss, J.A. FEBio: Finite Elements for Biomechanics. J. Biomech. Eng. 2012, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, S.A.; Ateshian, G.A.; Weiss, J.A. FEBio: History and Advances. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 19, 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timoshenko, S.; Goodier, J. Theory of Elasticity; McGraw-Hill Book Company: Columbus, OH, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Land, S.; Gurev, V.; Arens, S.; Augustin, C.M.; Baron, L.; Blake, R.; Bradley, C.; Castro, S.; Crozier, A.; Favino, M.; et al. Verification of cardiac mechanics software: Benchmark problems and solutions for testing active and passive material behaviour. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2015, 471, 20150641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridez, P.; Makino, A.; Miyazaki, H.; Meister, J.; Hayashi, K.; Stergiopulos, N. Short-Term biomechanical adaptation of the rat carotid to acute hypertension: Contribution of smooth muscle. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2001, 29, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zulliger, M.A.; Fridez, P.; Hayashi, K.; Stergiopulos, N. A strain energy function for arteries accounting for wall composition and structure. J. Biomech. 2004, 37, 989–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Chaikof, E.L.; Levenston, M.E. Numerical Approximation of Tangent Moduli for Finite Element Implementations of Nonlinear Hyperelastic Material Models. J. Biomech. Eng. 2008, 130, 061003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Horvat, A.; Milović, P.; Karšaj, I.; Tuković, Ž. A Block-Coupled Finite Volume Method for Incompressible Hyperelastic Solids. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12660. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312660

Horvat A, Milović P, Karšaj I, Tuković Ž. A Block-Coupled Finite Volume Method for Incompressible Hyperelastic Solids. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12660. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312660

Chicago/Turabian StyleHorvat, Anja, Philipp Milović, Igor Karšaj, and Željko Tuković. 2025. "A Block-Coupled Finite Volume Method for Incompressible Hyperelastic Solids" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12660. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312660

APA StyleHorvat, A., Milović, P., Karšaj, I., & Tuković, Ž. (2025). A Block-Coupled Finite Volume Method for Incompressible Hyperelastic Solids. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12660. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312660