1. Introduction

Human Activity Recognition (HAR) plays a crucial role in enabling intelligent systems to understand, interpret, and respond to human behaviors in real time. HAR is particularly crucial for healthcare monitoring [

1], elderly fall detection [

2], fitness tracking [

3], smart homes, rehabilitation [

4], and human–computer interaction [

5], among others. As populations age and digital health solutions expand, the ability to accurately and efficiently detect complex human activities becomes essential for improving safety, autonomy, and quality of life. State-of-the-art activity recognition systems are developed using external and wearable sensing [

6]. In external sensing, sensors are placed outside the person doing the activities. These sensors are placed in objects of interest, such as furniture or kitchen appliances. However, in wearable sensing, sensors are attached to the user directly or at least carried around by the user. This classification can be further broken down into vision-based, radio-based, and sensor-based approaches [

6,

7,

8]. In the sensor-based approach, sensors are often incorporated in the environment, objects, or in wearable devices, and these sensors often capture time-series data. Recently, HAR based on wearable sensors has emerged as a research hotspot over the past few years since wearable sensors are generally easy to deploy and relatively affordable to capture human activities.

The application of sensors like magnetometers, accelerometers, and gyroscopes that can be embedded in everyday wearables has made it the preferred data collection method for HAR researchers [

9]. However, before human activity signals captured using wearable sensors can be used to infer human activities, segmenting the signals into windows and extracting quality features is crucial. Traditional machine learning algorithms, such as support vector machines (SVMs), Bayesian networks, and random forests, among others, have been widely used for HAR tasks [

10]. Before such traditional models can be used, it is important to manually extract wearable sensor features, and this method can be tedious and time-consuming. However, the advent of deep learning has seen the issues of manually extracting features addressed [

9]. Deep learning models such as convolutional neural networks and recurrent neural networks are capable of extracting features automatically, and they have been used to achieve impressive results in wearable sensor HAR. Recently, several researchers have leveraged 1D-CNN in wearable sensor HAR, and some have incorporated modules, which are basically plug-and-play networks that aim to improve feature learning in wearable sensor data. However, these often come with increased computational overhead. Since the deployment of HAR systems is often in fitness monitoring, fall detection, gait analysis, and general health monitoring, it is important to develop state-of-the-art models with minimal computational cost.

A general limitation of traditional 1D-CNNs is that they often struggle to capture long-range dependencies due to their limited receptive field. Also, they focus on local patterns and cannot effectively aggregate global information across the entire sequence without stacking many layers, which increases computational cost. Similarly, in standard CNN architectures, positional information can degrade as features pass through successive convolutional and pooling layers. MaxPooling layers are used after convolutional operations to reduce dimensionality and computational load. While this approach is effective in image-based tasks, it is less suitable for the sensor signals used in HAR. MaxPooling introduces a form of temporal downsampling that can discard subtle yet crucial temporal information. This loss often become problematic in tasks that require both local and sequential information retention, such as human activity recognition from wearable sensors. To address this, our research proposes Retentive-HAR, which is designed to enhance feature learning by preserving cross-sequence dependencies from multiple convolutional layers in 1D CNN architectures. The proposed model intentionally omits the MaxPooling layer, thereby preserving the full temporal resolution throughout the network. The module takes feature outputs from four convolutional layers, combines them along the feature dimension, and transposes the sequence to enable comprehensive analysis across both sequence and feature spaces. To the best of our knowledge, our work is the first to propose such an architecture for feature learning in HAR. Specifically, our contributions can be summarized as follows:

First, we propose a novel feature extraction strategy using four parallel, single-layer dilated 1D-CNNs to learn multi-scale temporal representations, which are subsequently concatenated along the feature dimension;

Second, we transpose the sequence to enable comprehensive analysis across both sequence and feature spaces;

One-dimansional convolutional layers are used on the transposed feature maps to refine temporal dependencies across concatenated features further while preserving the full sequence resolution, before using Bidirectional LSTMs to capture long-range temporal dependencies in both forward and backward directions;

Lastly, extensive experiments and ablation studies show that the proposed Retentive-HAR model outperforms the state-of-the-art models with minimal computational overhead.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews the existing literature in wearable sensor HAR,

Section 3 discusses the methodology of the proposed model,

Section 4 presents the results of experiments on three publicly available datasets and ablations studies, and

Section 5 concludes.

2. Related Works

Research on the use of deep learning for human activity recognition has seen notable improvements since the work of Zeng et al. [

11], where a single-channel CNN layer with partial weight sharing was used to learn discriminative features from accelerometer data. Generally, deep learning models automatically extract features [

12]; however, the design, depth, or configuration of these models directly impacts the quality of features learned from human activity data. For instance, the authors in Qi et al. [

8] proposed a deep CNN model for HAR. To increase accuracy and the richness of the raw data derived from the accelerometer, gyroscope, and magnetometer data, the model employed signal processing techniques and a signal selection module. A classification accuracy of 95.27 percent was attained through experiments on the gathered dataset. Gomathi et al. [

13] developed a deep CNN architecture to classify human activities and employed the lambda max technique to initialize weight and achieve quick convergence. However, the model’s architecture did not consider the temporal properties contained in the signals, which limited the performance of the model.

To learn modality-specific temporal properties, Ha and Choi [

14] introduced a CNN structure with unique 1D CNNs for each kind of modality. Evaluation on the MHealth dataset showed that the model achieved a recognition accuracy of 91.94%. Essa et al. [

15] proposed a temporal-channel convolution with a self-attention network. Two novel architectures were proposed, with the first designed using convolution with self-attention network (CSNet) and the other designed using temporal-channel convolution with self-attention network (TCCSNet). The CSNet leverages both convolution and self-attention to capture both local and global dependencies in the input data while TCCSNet exploits both temporal and interchannel dependencies through two branches of convolutions and self-attentions for extracting time-wise and channel-wise information. Experiments on seven benchmark datasets showed an improvement in the quality of learned features. However, this improvement came at an additional overhead cost. Wang et al. [

16] proposed an adaptive solution called Dynamic Gaussian Convolution (DgConv), which adaptively learned optimal kernel size on sensor data for each convolutional layer. Experiments on six datasets demonstrated that the model achieved improved performance without sacrificing memory and computational cost, showing a notable accuracy gain compared to static convolution. However, despite its adaptability, DgConv focuses solely on local feature extraction and does not account for the temporal dynamics inherent in human activity signals. As a result, the model may perform poorly when dealing with activities that span longer temporal contexts or involve transitions.

Mekruksavanich et al. [

17] investigated the applicability of deep learning techniques for position-dependent and position-independent recognition of human activity (HAR). The study introduced a bidirectional residual attention-based GRU architecture, referred to as Att-ResBiGRU, which demonstrated a strong capability to handle position-dependent HAR while also maintaining high accuracy for position-independent scenarios. The model was evaluated across multiple benchmark datasets, including PAMAP2, REALWORLD16, and Opportunity, achieving competitive results. However, the complexity of the model and the reliance on deep recurrent layers result in increased computational overhead and training time, which may limit its deployment in real-time or edge-based environments. Dua et al. [

18] introduced a multi-input hybrid architecture that integrates CNNs and GRUs, combining three separate CNN-GRU branches to enhance feature learning. The model demonstrated strong performance, achieving classification accuracies of 95.27%, 96.20%, and 97.21% on the PAMAP2, UCI-HAR, and WISDM datasets, respectively. However, the size of the model was relatively large, and with a long training time.

Ige and Noor [

19] proposed a deep local temporal architecture based on pipeline concatenation. The model learned local features using a pipeline designed with Conv1D layers and temporal features using a pipeline designed with Bi-LSTM layers, before concatenating along the channel axis. Experiments on PAMAP2 and WISDM datasets showed improved recognition accuracy of 98.52% and 97.90% respectively. Also, Lalwani and Ramasamy [

20] introduced a hybrid architecture that integrates CNNs with both Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) and Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Units (BiGRUs) to effectively capture diverse temporal dependencies in sequential data. By combining these components, the model leverages the strengths of CNNs for extracting local patterns and the bidirectional recurrent units for modeling both short- and long-term temporal relationships. Additionally, the use of multiple convolutional filter sizes enhances the model’s ability to extract multi-scale temporal features. However, the integration of multiple deep learning components increases the model’s complexity and computational overhead, which may limit its deployment in resource-constrained environments such as wearable or edge devices.

Similarly, Liang et al. [

21] proposed a three-dimensional Weight Attention Module (WAM) designed to enhance feature learning by jointly considering spatial and channel-wise information. The module employs an energy-based optimization function to evaluate the importance of each neuron, enabling the computation of 3D attention weights across feature maps without introducing additional parameters. Unlike traditional attention mechanisms that focus solely on either spatial or channel dimensions, WAM captures more comprehensive contextual dependencies, thereby improving feature representation quality. Experimental results on benchmark datasets demonstrated that the integration of WAM led to improved model performance while maintaining computational efficiency. However, the approach primarily enhances feature reweighting within individual layers and does not explicitly model long-range temporal dependencies, which is important in human activity signals. As a result, while WAM improves local attention, it may be insufficient to capture temporal dynamics in some activities. Khan et al. [

22] proposed an ensemble model that combines one-dimensional convolutional neural networks (1D-CNNs) and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks to recognize postural transitions. Their method effectively captured both spatial and temporal dependencies, achieving an accuracy of 97.84% on the HAPT dataset. However, the model suffered from a very large parameter size, which increases computational cost and limits its suitability for deployment in real-time or resource-constrained environments.

Many existing deep learning models for human activity recognition (HAR) incorporate MaxPooling layers after convolutional operations to reduce dimensionality and computational load. While this approach is effective in image-based tasks, it is less suitable for time-series data such as sensor signals used in HAR. MaxPooling introduces a form of temporal downsampling that can discard subtle yet crucial temporal information. This can lead to misclassification of activities that differ only in fine-grained temporal patterns. Moreover, MaxPooling disrupts the alignment between time steps and predicted labels, which is essential for frame-wise or sequence-level recognition. To address this, the proposed Retentive-HAR model intentionally omits the MaxPooling layer, preserving the full temporal resolution throughout the network. This allows the model to capture fine-grained activity and maintain precise temporal dependencies. Compared to existing systems, our proposed Retentive-HAR model aims to achieve similar or better accuracy while maintaining a lightweight architecture, leveraging multi-branch convolutional and recurrent components that preserve temporal dependency without incurring substantial computational cost.

3. Materials and Methods

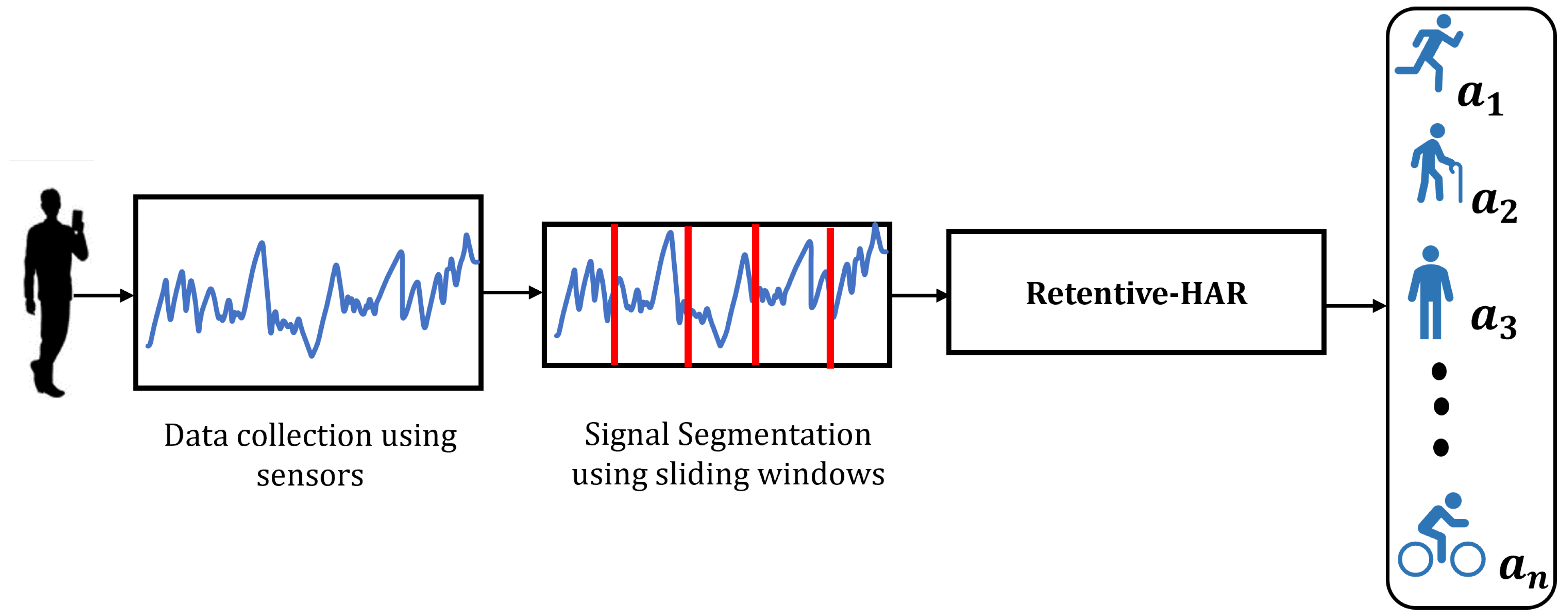

The proposed

Retentive-HAR model aims to capture both local and temporal dependencies through dilated convolutions, feature concatenation, transposition, and Bi-LSTM layers. The workflow of the model is presented in

Figure 1.

As shown, the workflow begins by leveraging motion signals collected using wearable inertial sensors, specifically accelerometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometers. These sensors, commonly embedded in smartphones or wearable devices, capture tri-axial data reflecting the user’s acceleration, angular velocity, and magnetic orientation as various activities are performed.

The sensor data are then segmented using the sliding window segmentation. A fixed-size window with a degree of overlap is used to segment the continuous signal stream into smaller, temporally consistent fragments. This segmentation is essential for preserving the sequential nature of the data while facilitating uniform input dimensions for subsequent model processing. Thereafter, the segmented signals are then passed into the proposed Retentive-HAR model. This model is designed to effectively capture both local dependencies and long-range temporal patterns, enabling robust classification of human activities. The final output of the model is a predicted activity label , which corresponds to a specific class such as walking, running, standing, sitting, or cycling.

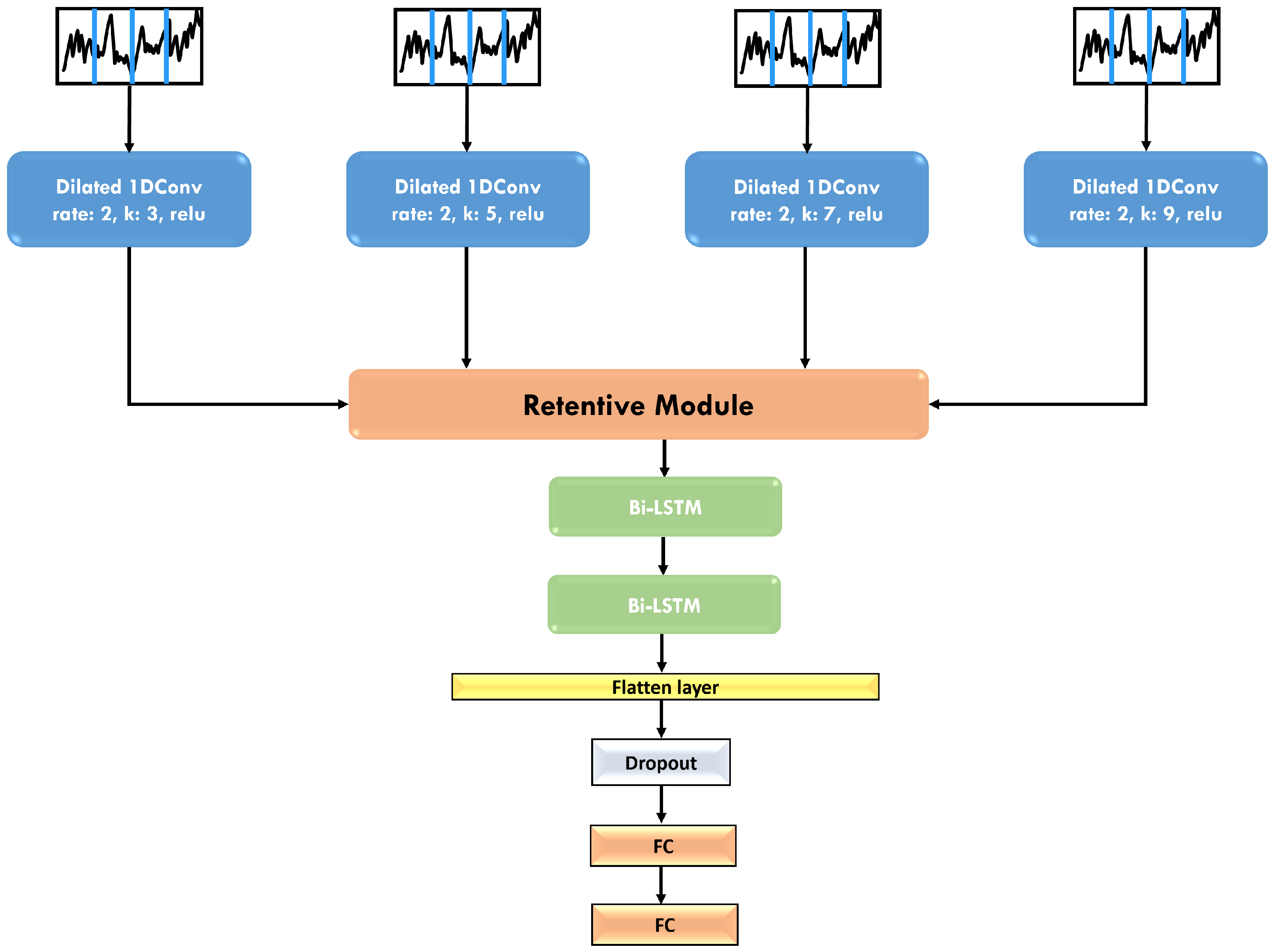

The architecture of the proposed Retentive-HAR model is presented in

Figure 2.

As shown in

Figure 2, four parallel input sequences are defined as

where

L is the sliding window size and

D is the feature dimension.

Each input sequence

(for

) is passed through a 1D dilated convolutional layer with

F filters, kernel size

k, and a dilation rate of

d, such that

where

represents the feature maps output of the dilated convolution for input

.

This transformation applies a 1D convolution [

23] with dilation rate

d, which expands the receptive field and allows each convolutional layer to capture temporal patterns over larger parts of the input sequence. By using dilated convolutions, we expand receptive field without reducing the resolution. Each dilated convolution captures broader temporal dependencies across the sequence without skipping any steps. For this reason, MaxPooling layers were not included after each dilated convolutions as this would have resulted in discarded time steps.

Thus, retains the sequential structure of the input, but with enhanced feature representations that capture longer-term dependencies. Each dilated convolutional layer is then passed to the Retentive module.

A 1D dilated convolution at time step

t with dilation rate

d and kernel size

k is mathematically expressed as

This formulation allows the network to capture long-range dependencies over time while preserving the complete temporal structure of the input signal, unlike MaxPooling which reduces sequence length and may eliminate subtle temporal cues essential for accurate activity classification.

3.1. Retentive Module

The architecture of the Retentive module is presented in

Figure 3.

In the retentive module, we start by concatenating the feature maps from all four inputs along the feature dimension, creating a single, combined feature map

that aggregates information across all inputs:

where

To capture dependencies across the combined feature dimensions, we transpose by swapping the sequence and feature axes. This transposition shifts the focus to inter-feature relationships and enables the model to learn dependencies across different feature representations.

In the Retentive module, two additional Conv1D layers are applied on the transposed feature maps to refine and enhance feature representations. These layers operate on the new feature orientation. By doing this, we apply Conv1D along the time dimension while using the full feature richness. For an input sequence

x and a kernel

w, the convolution operation is defined as

where

is the convolution of

x and

w at position

t,

k is the kernel size,

is the element of the input sequence at position

, and

is the kernel value at position

i.

To capture dependencies across feature maps, the ELU (Exponential Linear Unit) activation function is used with both Conv1D layers in the Retentive module. This process enables the model to capture short to mid-range temporal dependencies across time steps by convolving over the transposed time dimension.

3.2. Bi-LSTM Layers

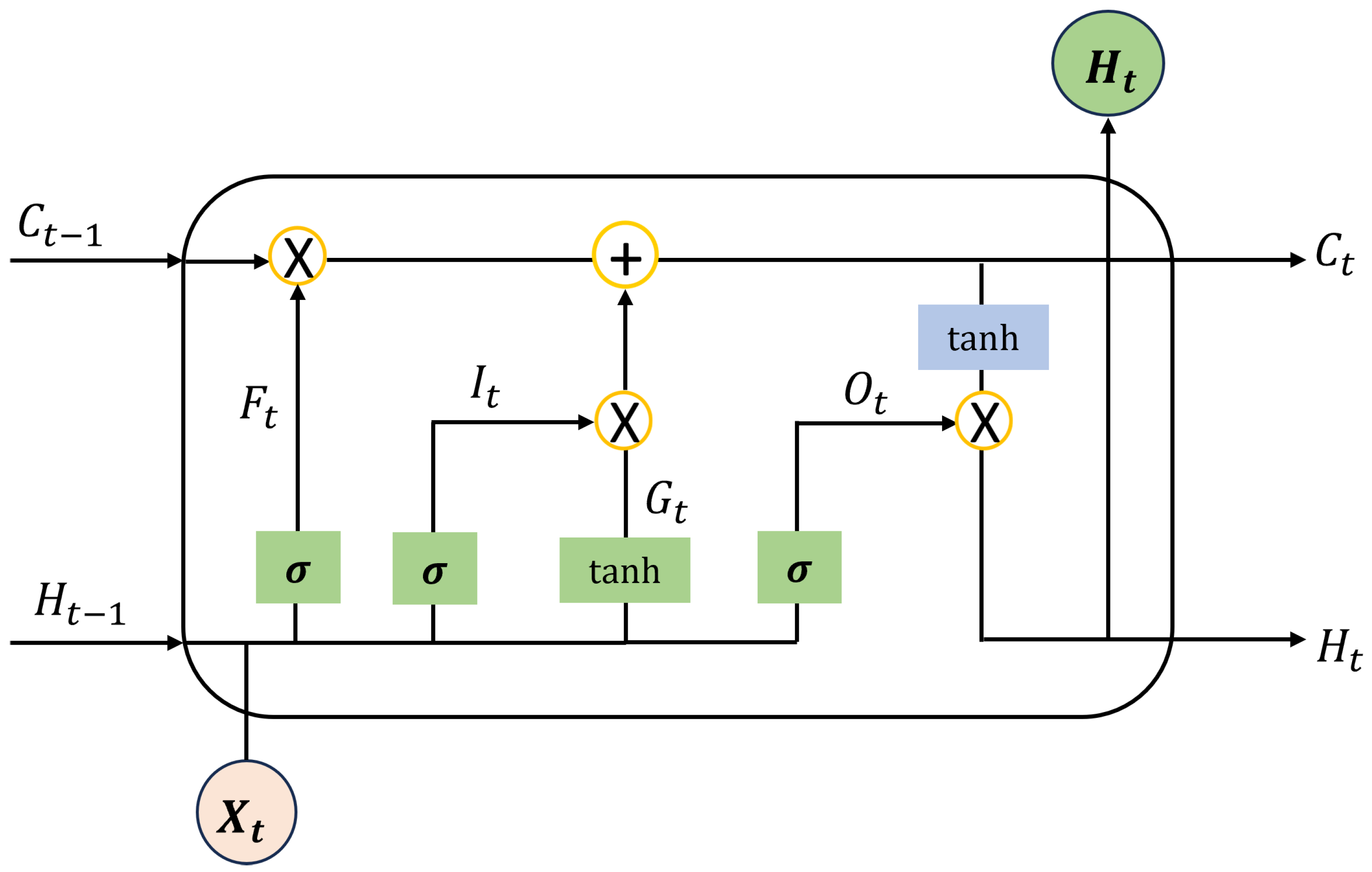

The convolutional operations in the retentive module effectively learn local temporal patterns, but they operate within a fixed receptive field, which limits their ability to capture long-range dependencies and temporal context beyond local neighborhoods. For this reason, two Bi-directional LSTM layers with 128 units each are stacked after the Retentive module. The architecture of an LSTM cell is presented in

Figure 4.

As illustrated in

Figure 4,

,

,

, and

represent the hidden state, forget gate, cell state, and output at time step

t, respectively. The input at this time step is denoted as

. The LSTM cell incorporates both sigmoid and tanh activation functions. The first step in the LSTM computation involves the forget gate, which determines the extent to which information from the previous hidden state should be retained. This process is defined by the following equation:

In this equation, , , , and denote the weight matrices and bias terms of the forget gate. A forget gate output of implies complete retention of the previous hidden state, whereas indicates that all previously stored information is entirely discarded.

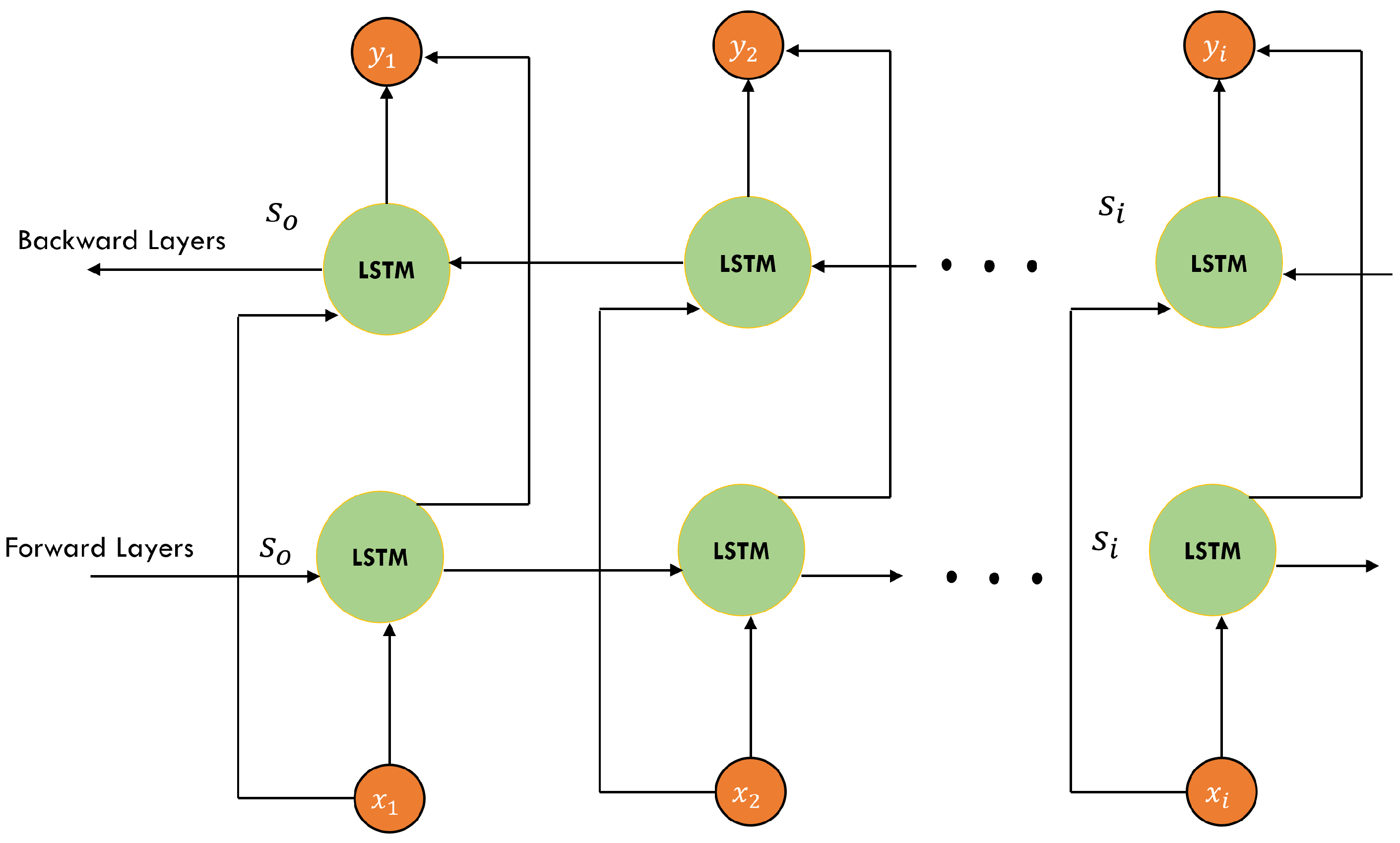

In our model, the first Bi-LSTM layer returns the full sequence, which is then passed to the second Bi-LSTM layer that outputs the final hidden state only. The Bi-LSTM processes the sequence along the original time dimension, using the temporally refined feature map output by the retentive module as input, hence capturing order-sensitive dependencies by maintaining memory across the entire sequence in both forward and backward directions. This bidirectional structure enables the model to leverage past and future context simultaneously and model long-range temporal structures. The structure of the Bi-LSTM is shown in

Figure 5.

The model is trained to minimize the cross-entropy loss, defined as

where

is the true label,

is the predicted activity, and

is the number of segments. The training procedure for the Retentive-HAR model is presented in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: Training Procedure for the Retentive-HAR Model. |

Input: Segmented sensor data Output: Trained Retentive-HAR model 1. Multi-Branch Dilated Convolution: For kernel sizes : 2. Feature Concatenation: 3. Transpose Feature Map: 4. Convolution Across Features: 5. Transpose Back and Flatten: 6. Bi-LSTM Layers: 7. Classification: 8. Model Training: Use Adam optimizer, cross-entropy loss Apply learning rate decay (patience = 10) Apply early stopping (patience = 50) |

4. Results

4.1. Implementation Details

The proposed model was built using TensorFlow 2.7.0 with Python 3.9 and trained on a workstation equipped with RTX 3050Ti 4 GB GPU and 16 GB RAM. The hyperparameters of the proposed Retentive-HAR model are presented in

Table 1.

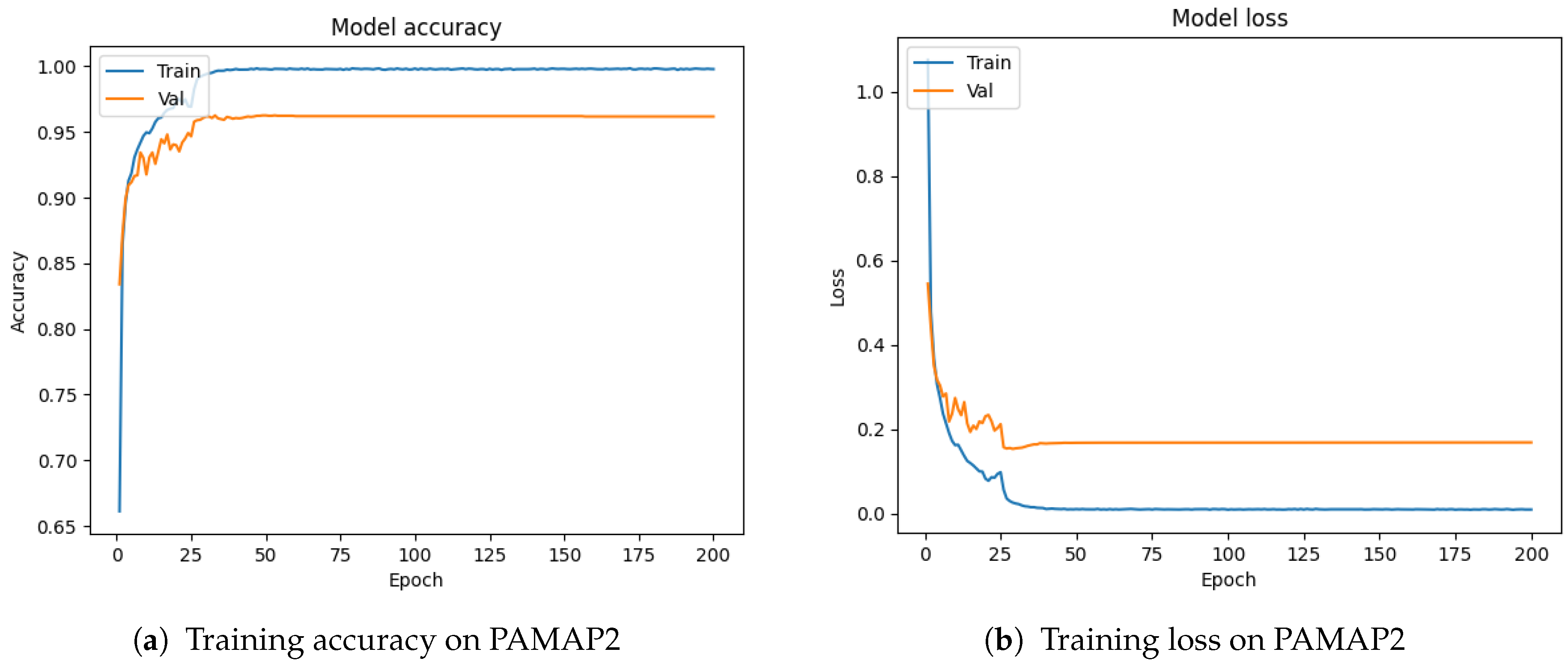

As shown, the model was trained using the

Adam optimizer for a maximum of 200 epochs, with an adaptive learning rate decay strategy. The initial learning rate was set to

and decayed to a minimum of

using a reduction mechanism triggered by a patience parameter of 10. This means the learning rate was reduced when the validation loss did not improve for 10 consecutive epochs (

Figure 6).

To avoid overfitting, we also employed early stopping with a patience of 50 epochs, halting training if no improvement in validation loss was observed over that duration.

Batch sizes were adjusted according to the dataset to balance performance and memory usage: 128 for PAMAP2 and HAPT and 256 for WISDM. Kernel sizes of 3, 5, 7, and 9 were used in the initial convolution layers to capture multi-scale temporal features, while a kernel size of 3 was fixed for the Retentive module. The dilation rate was set to two to expand the receptive field efficiently without increasing the model’s parameter count.

Sliding window segmentation was applied with dataset-specific window sizes: 171 for PAMAP2, 100 for HAPT, and 80 for WISDM, along with a 50% overlap rate for all datasets. These window sizes were selected based on prior literature and reflect common practices in the HAR domain.

4.2. Datasets

This research considered three widely used HAR datasets including PAMAP2 [

24], WISDM [

25], and HAPT [

26] for model training and evaluation. These datasets encompass a broad range of human activities and sensor types, reflecting the diversity found in real-world applications. Overall, they provide a realistic basis for assessing the performance of our HAR approach.

4.2.1. PAMAP2

The Physical Activity Monitoring for Aging People 2 (PAMAP2) dataset [

24] includes eighteen daily physical activities that were documented, including basic and complex activities. Gyroscope, accelerometer, magnetometer, heart rate monitor, and temperature readings were all included in the dataset. A total of 52 attributes altogether make up the dataset, which was recorded at a sample rate of 100 Hz. This research did not consider heart rate and temperature signals, as we focus on the 36 features of accelerometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometer sensors.

4.2.2. HAPT

To acquire the HAPT dataset [

26], experiments were conducted involving a cohort of 30 volunteers. These volunteers engaged in six core activities: three static postures (lying down, sitting, and standing) and three dynamic movements (walking, descending stairs, and ascending stairs). Transitions between static postures were also included, such as standing to sitting, sitting to standing, lying down to sitting, standing to lying down, and lying down to standing. Each participant wore a Samsung Galaxy S II smartphone affixed to their waist during data collection. The smartphone’s built-in accelerometer and gyroscope captured three-axial linear acceleration and three-axial angular velocity consistently at 50 Hz. The collected dataset was randomly split into two subsets: 30% of the volunteers were designated for test data while 70% constituted the training data.

4.2.3. WISDM

The Wireless Sensor Data Mining (WISDM) dataset [

25] was collected using smartphone based inertial sensor. It was collected by the WISDM Lab at Fordham University and contains data from the accelerometers of Android smartphones carried in the user’s front pants pocket. The dataset includes recordings from 36 subjects performing six distinct activities: Walking, Jogging, Sitting, Standing, Upstairs, and Downstairs, with each activity sampled at a frequency of 20 Hz.

4.3. Experiments on PAMAP2

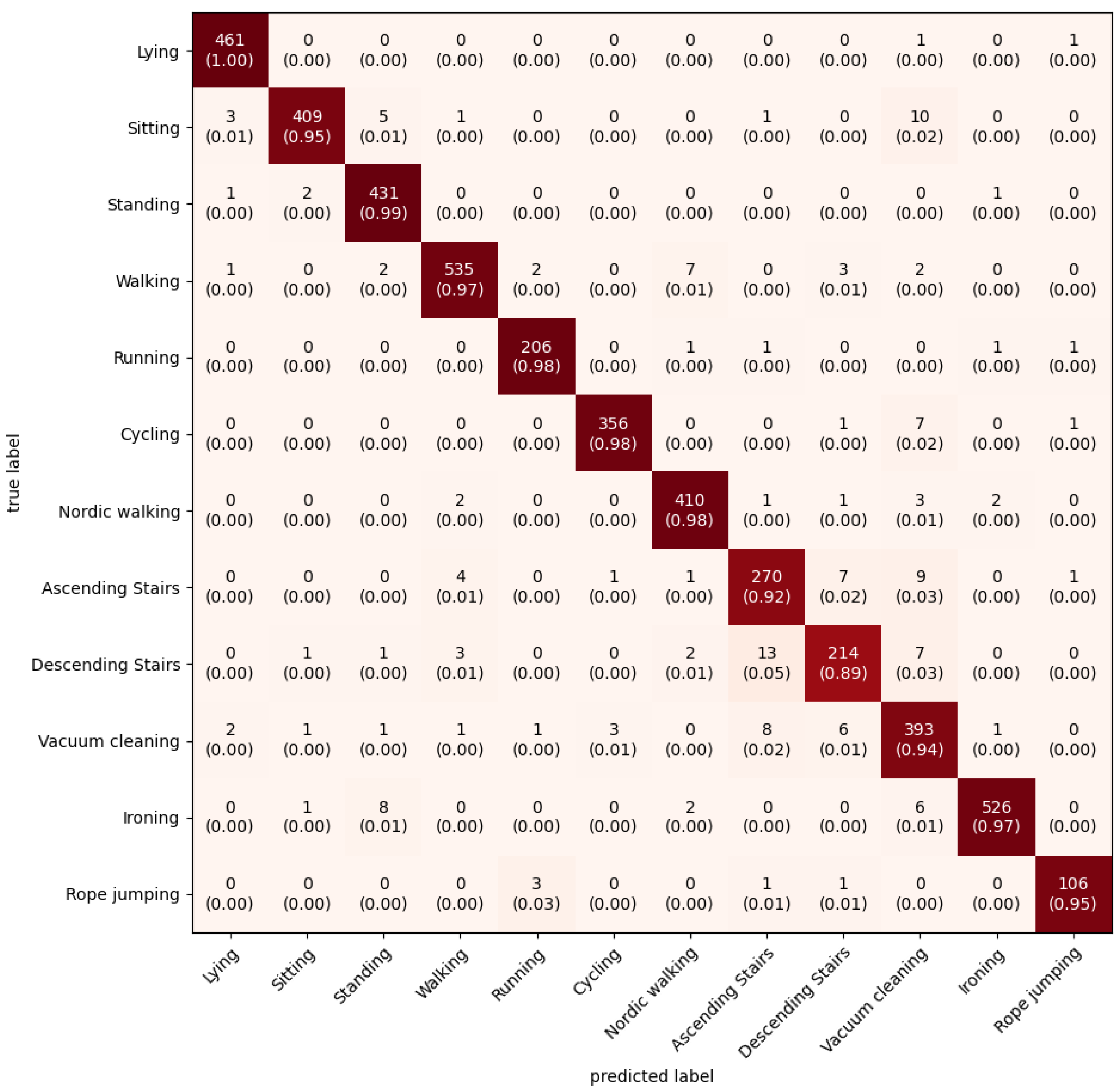

On the PAMAP2 dataset, the model returns 96.40%. The confusion matrix is presented in

Figure 7.

The performance of the proposed Retentive-HAR model was further analyzed using the confusion matrix shown in

Figure 7, which presents class-wise prediction outcomes on the PAMAP2 dataset. Each cell indicates the number of instances predicted for a class (columns) against the actual class labels (rows), with per-class accuracy presented in parentheses. Overall, the Retentive-HAR model demonstrates strong discriminative power, achieving near-perfect classification for most activities. Notably, the model achieves 100% accuracy for Lying, and greater than 97% accuracy for Standing, Walking, Running, Cycling, Nordic Walking, Ironing, and Rope Jumping. This indicates that the model effectively captures the unique temporal patterns associated with both stationary and repetitive dynamic activities. The Retentive Module, by preserving full temporal resolution and applying transposed convolutional refinement, helps maintain fine-grained temporal cues, which are crucial for such accurate classification. The strong diagonal dominance in the confusion matrix demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed Retentive-HAR model, particularly in learning multi-scale temporal dependencies while preserving sequential fidelity.

To further investigate the performance of the proposed model on the PAMAP2 dataset, the classification report is also presented in

Table 2.

As shown in the classification report above, the Retentive-HAR model achieves consistently high performance across all metrics. Lying, Standing, Walking, Running, Cycling, and Ironing achieve F1-scores above 0.97, with Lying achieving perfect recall (1.00), indicating the model’s exceptional ability to identify and distinguish stationary postures. Similarly, dynamic activities such as running, cycling, and rope jumping are detected with high accuracy, supported by precision and recall values of 0.96 to 0.99, demonstrating the model’s strength in recognizing repetitive motion patterns with temporal consistency. The strong precision–recall balance across most classes indicates that the model not only predicts correct labels reliably but also recovers the majority of true instances, resulting in F1-scores above 0.95 for the majority of activities.

However, a few challenging classes, such as Ascending Stairs (F1 = 0.92) and Descending Stairs (F1 = 0.90), show relatively lower scores, reflecting the difficulty in capturing subtle transitions that often resemble walking or running. This is consistent with the confusion matrix, which showed overlapping predictions for these transitional activities. Similarly, Vacuum Cleaning recorded the lowest precision (0.90), though its recall remained high (0.94), suggesting that while the model frequently detects the activity, it occasionally misclassifies other similar activities as vacuum cleaning.

The result on the PAMAP2 dataset highlights the proposed model’s robustness in recognizing both static and dynamic activities and its ability to generalize across complex activity.

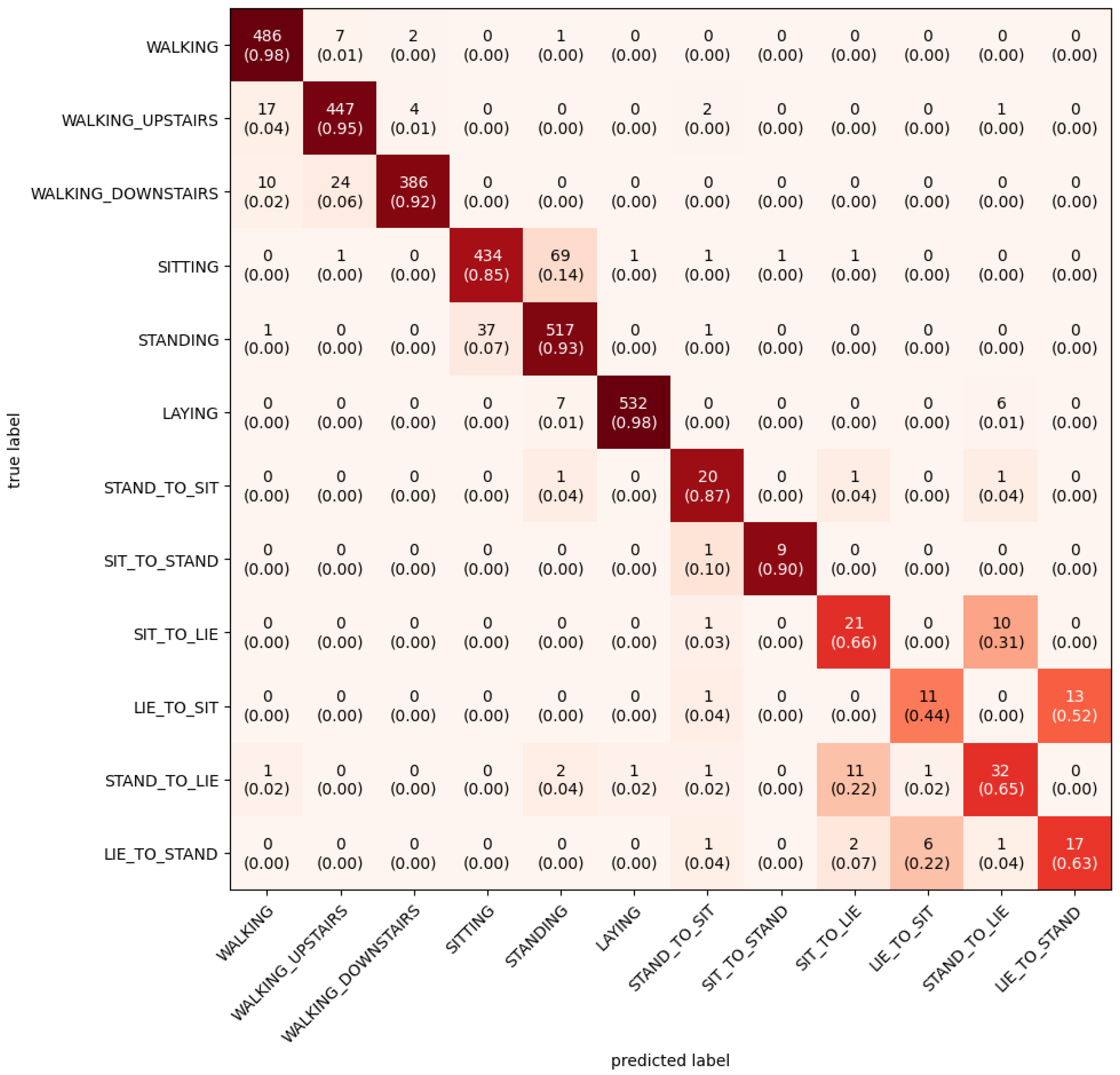

4.4. Experiments on HAPT

On the HAPT dataset, the model achieved a recognition accuracy of 94.70%. The model training and loss are presented in

Figure 8 and the confusion matrix in

Figure 9.

As shown in the confusion matrix, the model achieved precision rates above 0.90 for Walking (98%), Walking Upstairs (95%), Walking Downstairs (92%), Standing (93%), and Laying (98%). These results highlight the model’s ability to accurately recognize distinct movement patterns that exhibit consistent and repetitive temporal signals. In particular, the model effectively distinguishes between walking variants, showing minimal confusion among Walking, Walking Upstairs, and Walking Downstairs, which are often difficult to separate due to their shared gait structure. For static postures, the model also performs well. Laying is correctly classified in 98% of cases, while Sitting and Standing achieve 85% and 93% accuracy, respectively. Misclassifications between Sitting and Laying are relatively low, suggesting that the model can effectively distinguish between subtle differences in sensor signals that arise from torso orientation and movement levels. However, the most notable performance challenge lies in the classification of transitional activities. For instance, Sit-to-Lie is frequently misclassified as Lie-to-Sit and Lie-to-Stand, and Stand-to-Lie is misidentified as Sit-to-Lie or Lie-to-Sit.

Table 3 presents the classification report of the Retentive-HAR model on the HAPT dataset in terms of precision, recall, and F1-score for each activity class. The model performs exceptionally well on basic activities, achieving F1-scores of 0.96 for Walking, 0.95 for Walking Downstairs, and 0.99 for Laying, demonstrating its strength in recognizing consistent movement patterns. Sitting and Standing also achieve solid performance with F1-scores of 0.89 and 0.90, respectively. In contrast, transitional activities such as Lie to Sit, Sit to Lie, Stand to Lie, and Lie to Stand yield significantly lower F1-scores (ranging from 0.51 to 0.64), indicating challenges in detecting these brief, subtle transitions.

4.5. Experiments on WISDM Dataset

Comparison with State-of-the-Art

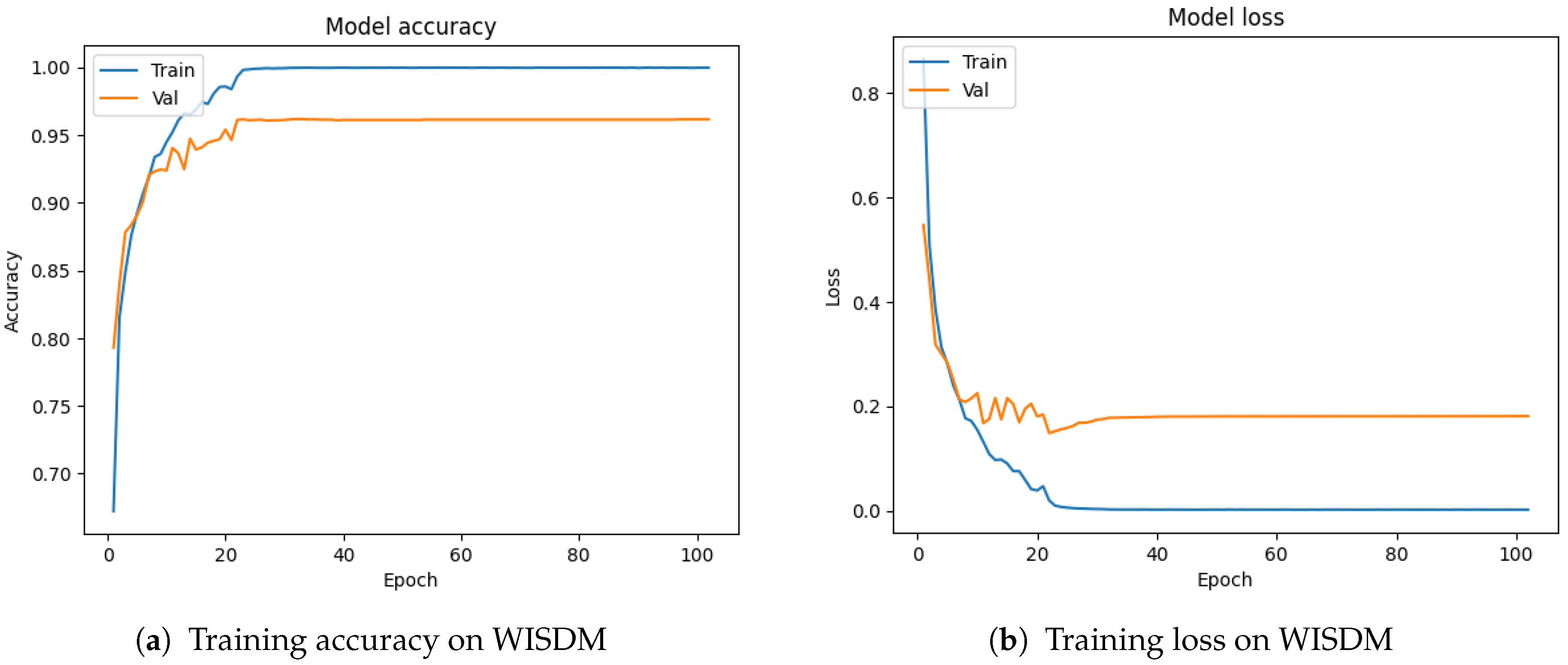

The proposed Retentive-HAR model achieved a recognition accuracy of 96.16% on the WISDM dataset. The model training and loss plot is presented in

Figure 10.

The confusion matrix of the proposed Retentive-HAR model on WISDM is presented in

Figure 11. As shown, the confusion matrix showcases strong classification performance across all six activity classes. The model demonstrates excellent predictive accuracy for Walking (99%), Sitting (99%), and Jogging (98%), highlighting its ability to learn both static and dynamic motion patterns effectively. Standing and Upstairs are also recognized with high accuracy (96% and 85%, respectively), although minor confusion exists between Upstairs and Downstairs, which is expected given their similar movement dynamics. The most notable misclassification occurs within the Downstairs activity, where some samples are incorrectly predicted as Upstairs (9%) and Walking (6%). Nonetheless, the model retains a high degree of class separability, reflecting the effectiveness of the Retentive Module in capturing temporal dependencies.

Table 4 presents the precision, recall, and F1-score for each activity class as predicted by the Retentive-HAR model on the WISDM dataset. The model achieved outstanding performance on most activities, with F1-scores of 0.98 or higher for Jogging, Sitting, Standing, and Walking, demonstrating its ability to accurately recognize both dynamic and static activities. Particularly, Sitting and Standing achieved near-perfect precision and recall, confirming the model’s strength in distinguishing stationary postures. Downstairs and Upstairs activities showed slightly lower F1-scores of 0.86, primarily due to the inherent similarity in movement patterns during stair-related actions, as also reflected in the confusion matrix. Nonetheless, the overall results prove the model’s robustness in capturing fine-grained temporal features and maintaining high classification consistency across diverse activity types.

4.6. Ablation Studies

To better understand the contribution of different components of the proposed Retentive-HAR model, we conducted a series of ablation studies. These experiments were designed to evaluate the individual and combined effects of architectural and training choices on the model’s overall performance. In particular, we investigated the impact of using different batch sizes on training stability and generalization. Additionally, we examined the effect of the Retentive Module by conducting experiments where the dilated Conv1D branches and transposed feature learning components were removed. This allowed us to isolate and quantify the contribution of the Retentive Module to the model’s effectiveness.

Figure 12 provides a detailed assessment of the contributions of the key architectural components;

dilated convolutions and the

Retentive module (RM) to the overall performance of the Retentive-HAR model. The configuration labeled

Dilation with RM, which represents the full model, achieved the highest accuracy across all three datasets, with 96.40% on PAMAP2, 96.16% on WISDM, and 94.70% on HAPT. This confirms the effectiveness of combining both dilated convolutions and the Retentive module in learning rich temporal and cross-feature representations.

When the Retentive module was removed (Dilation no RM), there was a noticeable drop in accuracy on all datasets, especially on HAPT, where performance declined to 93.48%. This indicates that while dilated convolutions capture long-range temporal dependencies, the absence of the Retentive module limits the model’s ability to exploit cross-feature interactions, which are essential for complex activity classification.

Similarly, the No Dilation with RM configuration still achieved competitive performance (96.01% on PAMAP2, 95.98% on WISDM, and 93.79% on HAPT), demonstrating that the Retentive module alone significantly contributes to learning discriminative representations. However, the performance is marginally lower than the full model, highlighting the complementary roles of dilated convolutions and the Retentive module. The lowest performance was observed in the No Dilation, No RM configuration, where both components were removed. Accuracy dropped to 92.58% on HAPT, 94.45% on PAMAP2, and 95.20% on WISDM, reinforcing the importance of both dilation and the Retentive module in achieving optimal model performance.

Overall, the ablation results validate that both dilated convolutions and the Retentive module are essential to the success of the proposed architecture, with their integration leading to consistently superior results across multiple datasets.

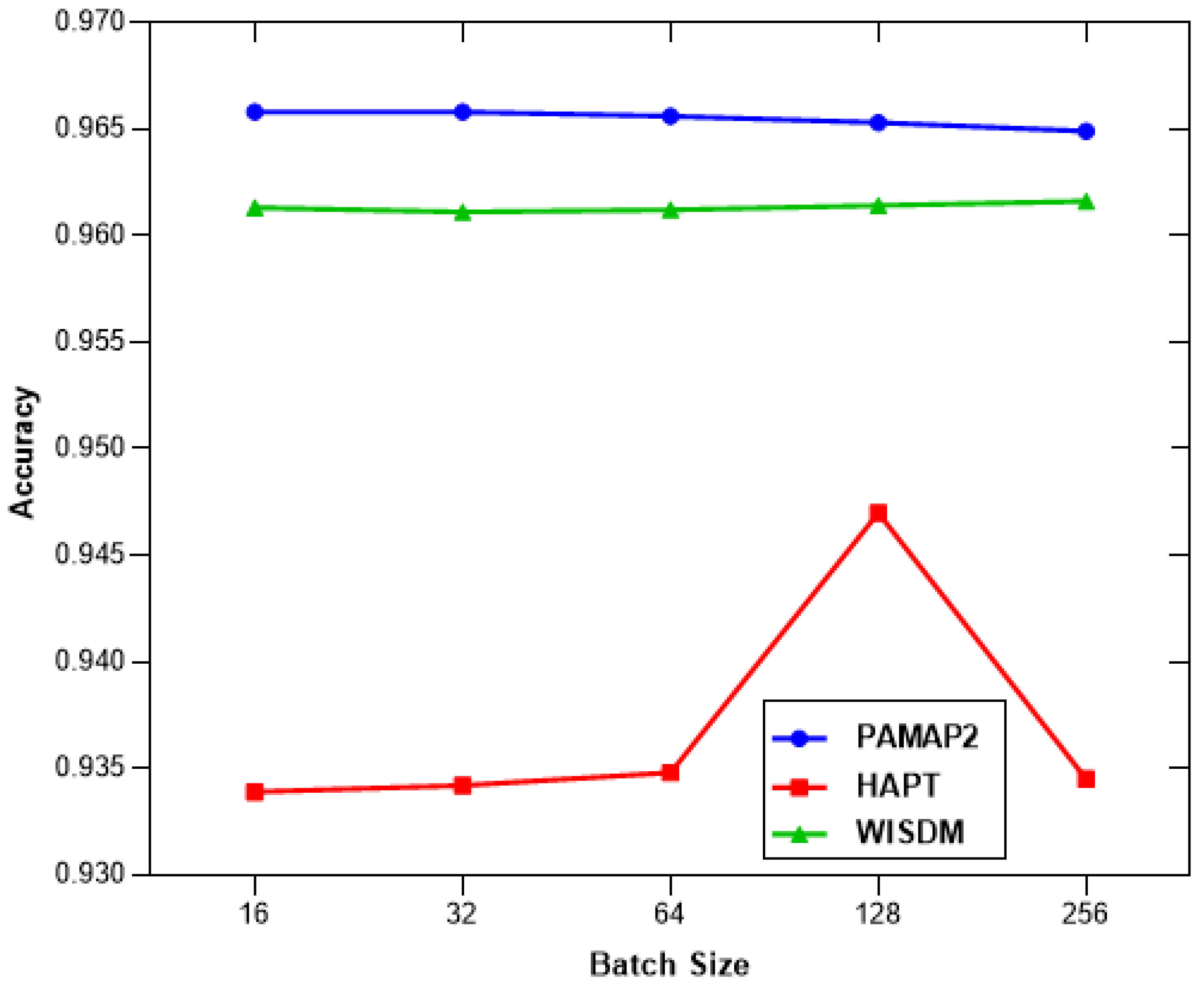

Also, experiments were conducted to investigate the effect of batch sizes, and the result is presented in

Figure 13.

4.7. Comparison with State-of-the-Art

As shown in

Table 5, the performance of the proposed Retentive-HAR is compared against existing state-of-the-art models.

Table 5 presents a comparison of the proposed Retentive-HAR model with existing state-of-the-art approaches in terms of classification accuracy and model size on the PAMAP2 dataset. The proposed model achieves the highest accuracy of 96.40%, outperforming the compared systems, including the multi-input hybrid approach by Mim et al. [

32] (95.61%), the CNN-GRU model by Dua et al. [

18] (95.27%), and the deep residual network used by Lu et al. [

33] (96.25%). Importantly, the Retentive-HAR model achieves this improvement with a compact model size of only 0.925 M parameters, demonstrating a favorable trade-off between performance and computational efficiency. Compared to larger models such as Gao et al. [

29] (3.51 M) and Han et al. [

28] (1.37 M), the proposed method offers a more lightweight solution suitable for real-time or resource-constrained applications. This balance of accuracy and model compactness highlights the effectiveness of the Retentive module and the model’s overall architecture in capturing discriminative temporal features for human activity recognition.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we propose Retentive-HAR, a lightweight and effective deep learning architecture designed for human activity recognition using wearable sensor data. The model introduces a Retentive module that captures multi-scale temporal features through concatenated dilated convolutions, transposition, and sequential Conv1D layers, followed by a Bi-LSTM layer to learn long-range bidirectional dependencies. Extensive experiments on three benchmark datasets, PAMAP2, HAPT, and WISDM, demonstrate that Retentive-HAR consistently outperforms existing state-of-the-art models in terms of classification accuracy. Notably, it achieves these results with a relatively small number of model parameters, making it well-suited for deployment in real-time and resource-constrained environments. While the model demonstrates excellent generalization and recognition capabilities, some challenges remain in the accurate detection of transitional activities, which often exhibit subtle temporal variations and shorter durations. These characteristics make it difficult for the model to learn sufficiently discriminative features using fixed window segmentation. Also, the Retentive-HAR model’s architecture struggles with fine-grained separation of highly overlapping activities (inter-class similarity).

For future work, we aim to explore more multimodal datasets and the integration of adaptive temporal weighting to further enhance the model’s sensitivity to transitional patterns. Also, we plan to explore adaptive sliding window techniques, which dynamically adjust the window size based on changes in the signal distribution. This can help preserve more meaningful temporal context and improve classification performance on transitional activities. Additionally, we plan to investigate personalized and cross-subject adaptation techniques to improve robustness in real-world scenarios. Also, we will explore the integration of attention mechanisms into the Retentive module. This hybrid approach is expected to improve the model’s robustness against inter-class similarity issues and increase overall classification accuracy in challenging HAR scenarios.