4.1. Model Building

The model is based on triaxial tests. The Binary-Medium Model assumes that, during the loading process, the soil is supported by two parts: bonded blocks and weakened bands. Initially, the load is primarily supported by the bonded blocks and the stress–strain relationship satisfies Hooke’s law. As loading continues, weakened bands gradually form and plastic deformation occurs within the soil. Even after complete destruction, the soil sample retains a certain bearing capacity, i.e., residual stress.

It is known from the principle of strain equivalence [

53] (as shown in Equation (2)),

denotes effective stress,

denotes effective strain, which can be determined from the stress–strain curve. D denotes the total damage factor, which may be calculated according to the following Equation (3):

where

is the effective stress;

is the modulus of elasticity of the bonded blocks;

is the effective strain; and

is the damage factor.

The damage of the soil body consists of two parts: initial damage and load loading, so the damage factor

is selected by using a coupled damage evolution, i.e.,:

where

is the initial damage;

is the damage caused by load action;

is the damage caused by coupling action.

Since the damage of bonded blocks satisfies the elastic theory, the change in elastic modulus is used as the damage factor. Since water content causes soil strength reduction and freeze–thaw cycles also cause strength reduction, the coupled damage

of freeze–thaw cycles and water content is defined in terms of elastic modulus, respectively. In order to facilitate the subsequent writing,

is defined as the freeze–thaw degradation factor.

is defined as the ratio of the elastic modulus after a freeze–thaw cycle to the reference modulus (without freeze–thaw);

is defined as the water content degradation factor.

β denotes the ratio of the elastic modulus of a specimen at a certain water content to its elastic modulus at the initial water content.; and

is defined as the dry density degradation factor.

denotes the ratio of the elastic modulus of a specimen at a given dry density to the elastic modulus at the maximum dry density of experimental setup, as follows:

Then the coupled damage of freeze–thaw and water content can be expressed as:

where

is the resilient modulus of soil after

freeze–thaw cycles;

is the resilient modulus of soil without freeze–thaw cycles;

is the resilient modulus of soil corresponding to the water content at which the test was carried out; and

is the resilient modulus of soil corresponding to the initial value of water content at which the test was set.

Since the reduction in dry density also reduces the strength of the soil, the modulus of elasticity is still used to define the strength degradation caused by the reduction in dry density:

where

is the modulus of elasticity corresponding to the dry density at which the test was conducted;

is the modulus of elasticity corresponding to the dry density at which the test was set to maximum.

At this point, from the aforementioned Equations (7) and (8), the initial damage under three factors is derived through the coupling damage process. As shown in Equation (9):

When there is only one dry density and water content, the equation degenerates to:

Damage under loading consists of damaged particles and undamaged particles. Therefore, the damage factor of loess under loading can be expressed as the ratio of the number of damaged microelements to the total number of microelements:

where

is the number of damaged microelements inside the soil;

is the total number of soil microelements.

The introduction of randomly distributed composite functions [

54] quantitatively describes the intensity of microelements:

where

is the strain of the soil;

and

are the parameters of the distribution of the composite function related to the mechanical properties of the soil.

Then the number of microelements damaged in the soil as a whole is:

where

is a constant. The damage factor of loess under loading is obtained by bringing in Equation (11):

When the soil is not damaged,

,

, which gives

, which can be obtained by combining the above Equations (2), (3), (9) and (14):

where

are the deviatoric stresses of the loess microelement;

is the axial effective strain of the loess.

When there is only one water content and dry density degree, the total damage equation degenerates to:

when the soil is completely destroyed (

), the soil still has a certain bearing capacity and this part is the residual shear strength. Therefore, the deviatoric stress of loess is borne by two parts, which can be expressed as:

where

is the deviatoric stress borne by the microelement of the damaged part of the soil;

is the residual deviatoric stress; and

is the deviatoric stress borne by the undamaged part of the soil. Equation (15) is brought into Equations (19) and (20). From the principle of strain equivalence, the effective variable of loess is equal to the apparent strain [

55,

56], i.e.,

. In summary, the damage statistical model of loess is:

i.e.,

The constitutive model degenerates when there is only one dry density and dry density:

The model contains seven parameters, . Among them, can be obtained from the freeze–thaw cycles test, and the parameters and need to be further calculated.

When the axial stress of loess reaches the peak deviatoric stress, the derivative value is 0. Therefore, in Equation (22), if we make

then we have:

organised:

substituting

into the damage model (21) yields:

i.e.,

The above Equation (25) is carried over to Equation (27) obtain:

i.e.,

where

is the peak deviatoric stress;

is the axial strain corresponding to the peak deviatoric stress.

The parameters and can be deleted according to the test conditions. and can be deleted when only freeze–thaw cycles are variables; can be deleted when freeze–thaw cycles and water content are variables; and can be deleted when freeze–thaw cycles and dry density are variables.

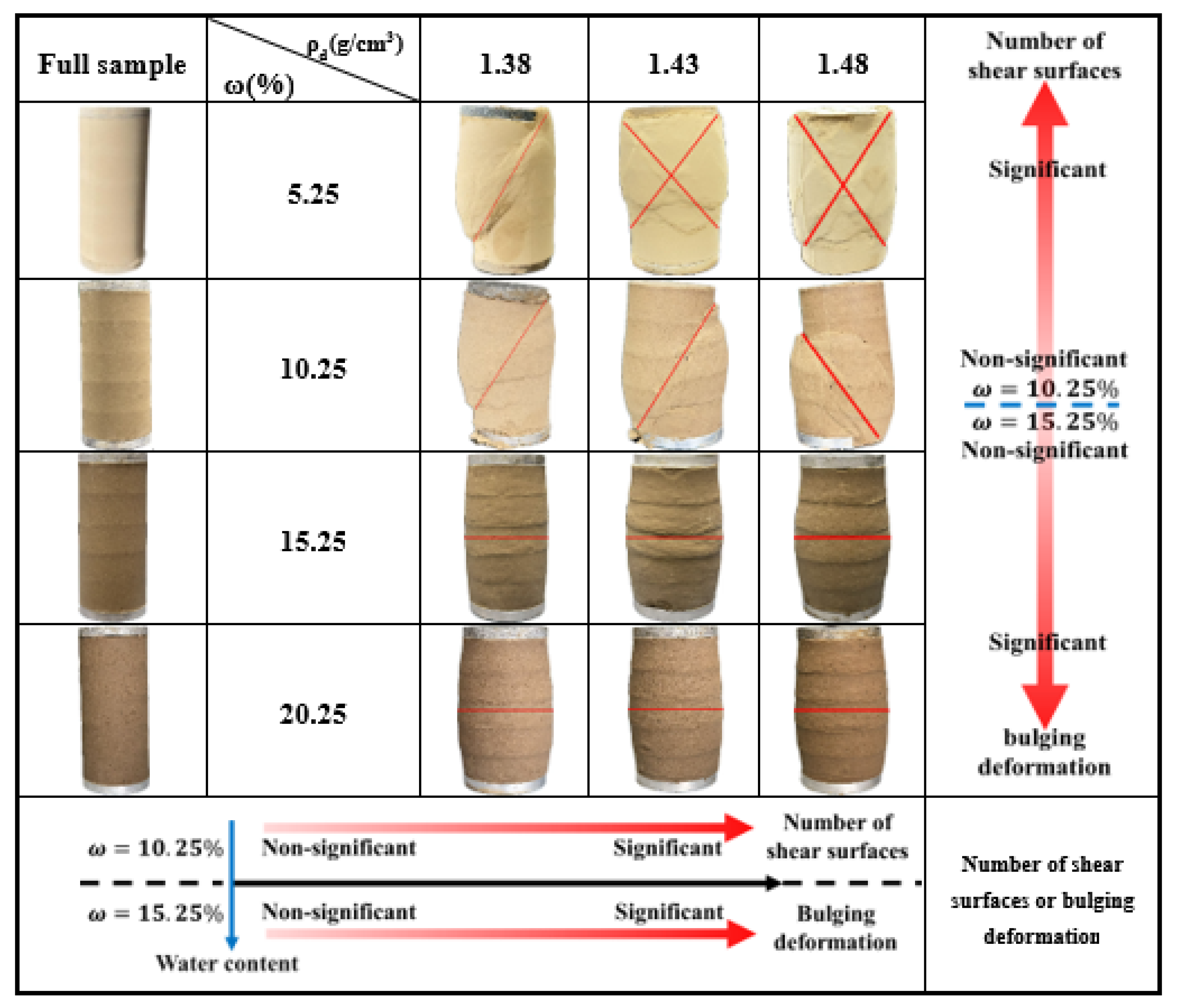

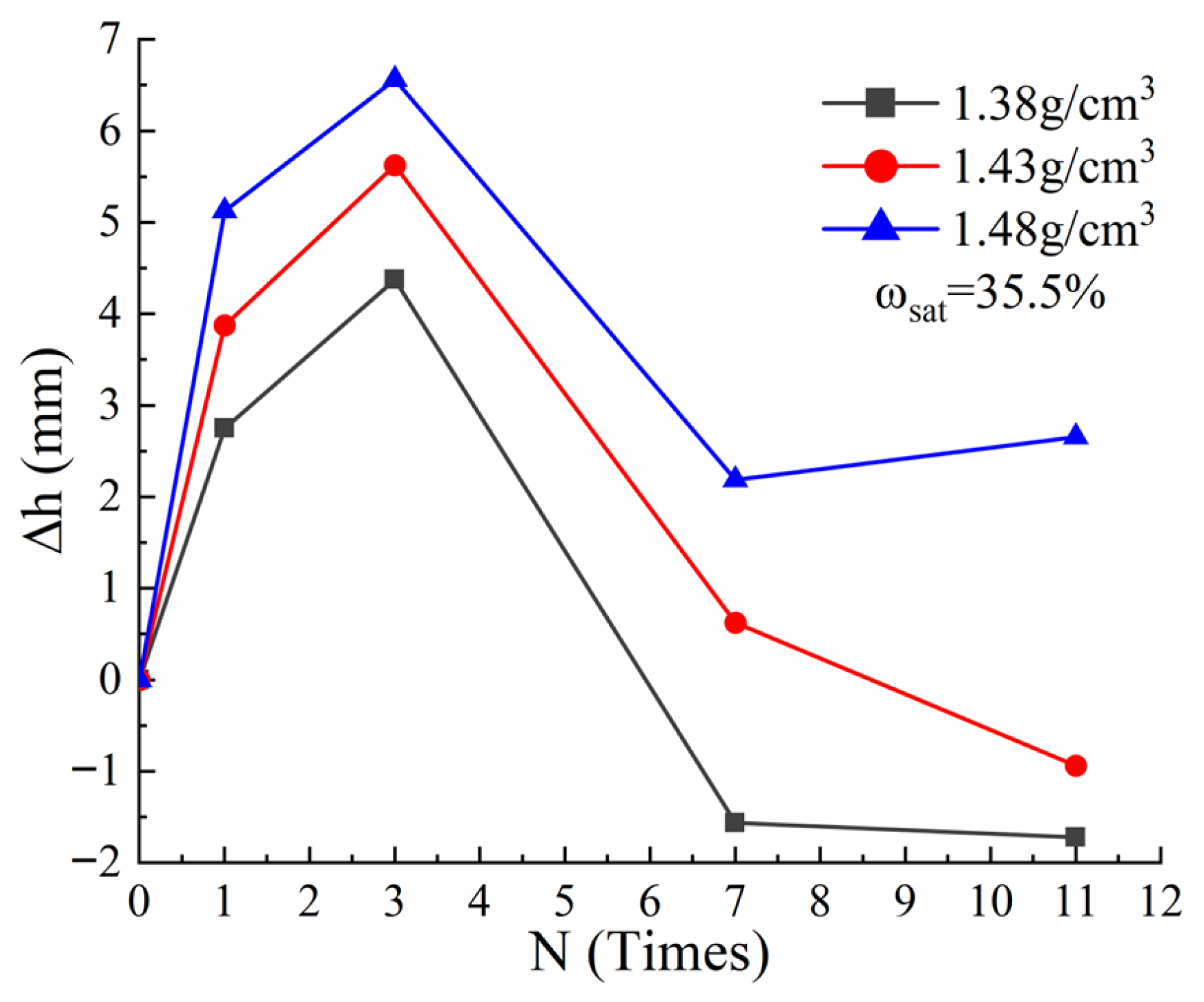

When the soil’s water content is high and its dry density is low, the strength curve is of the hardening type. The soil cannot reach its peak strength at this point, so the stress corresponding to an axial strain of 15% is taken as the peak strength instead. The residual stress cannot be obtained directly at this point. Based on the above test results, the ratio of residual strength to peak strength is used as an empirical value,

, for the residual strength of the hardening curve.

Based on the experimental results, the average of was determined to be 0.8.

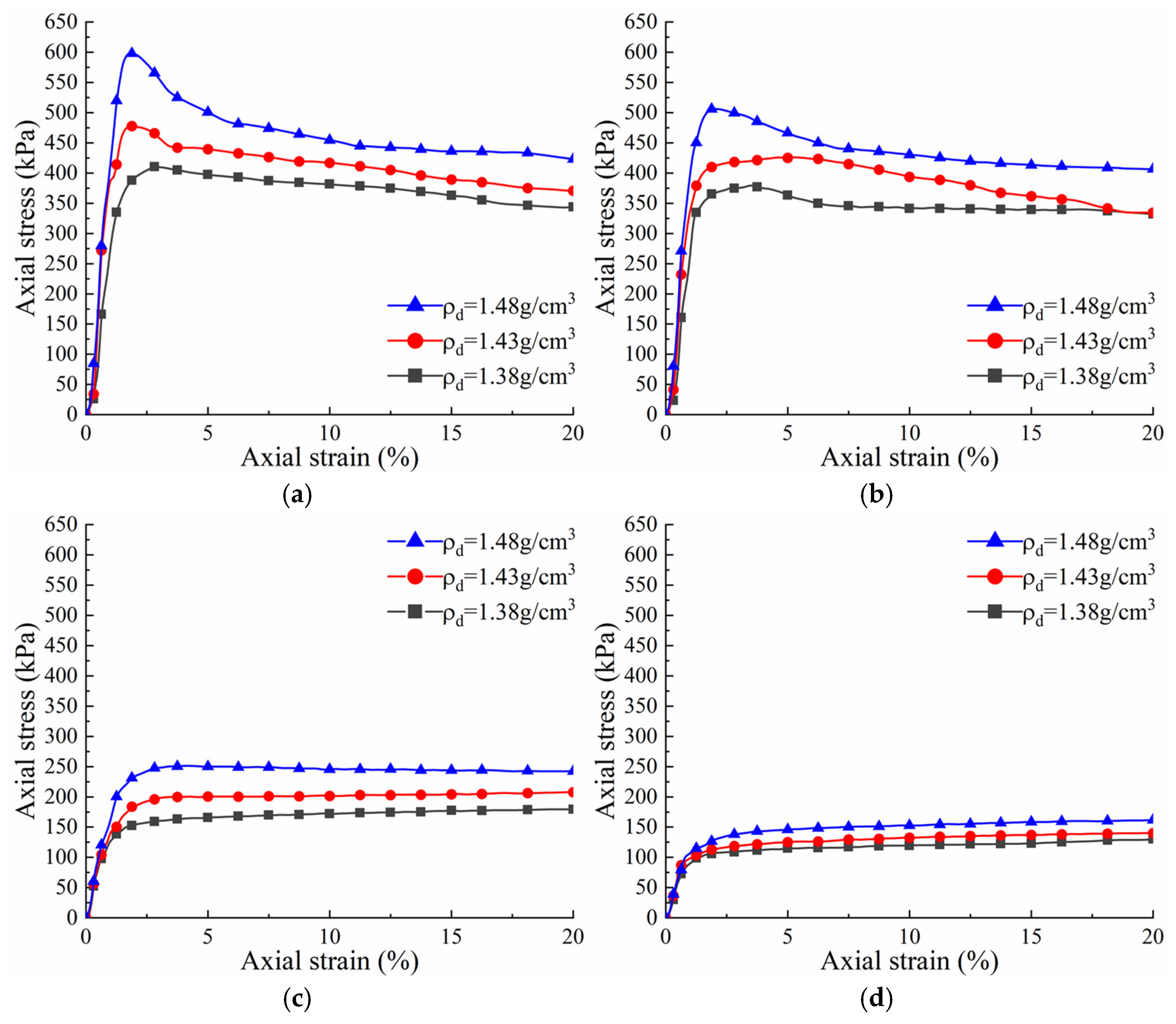

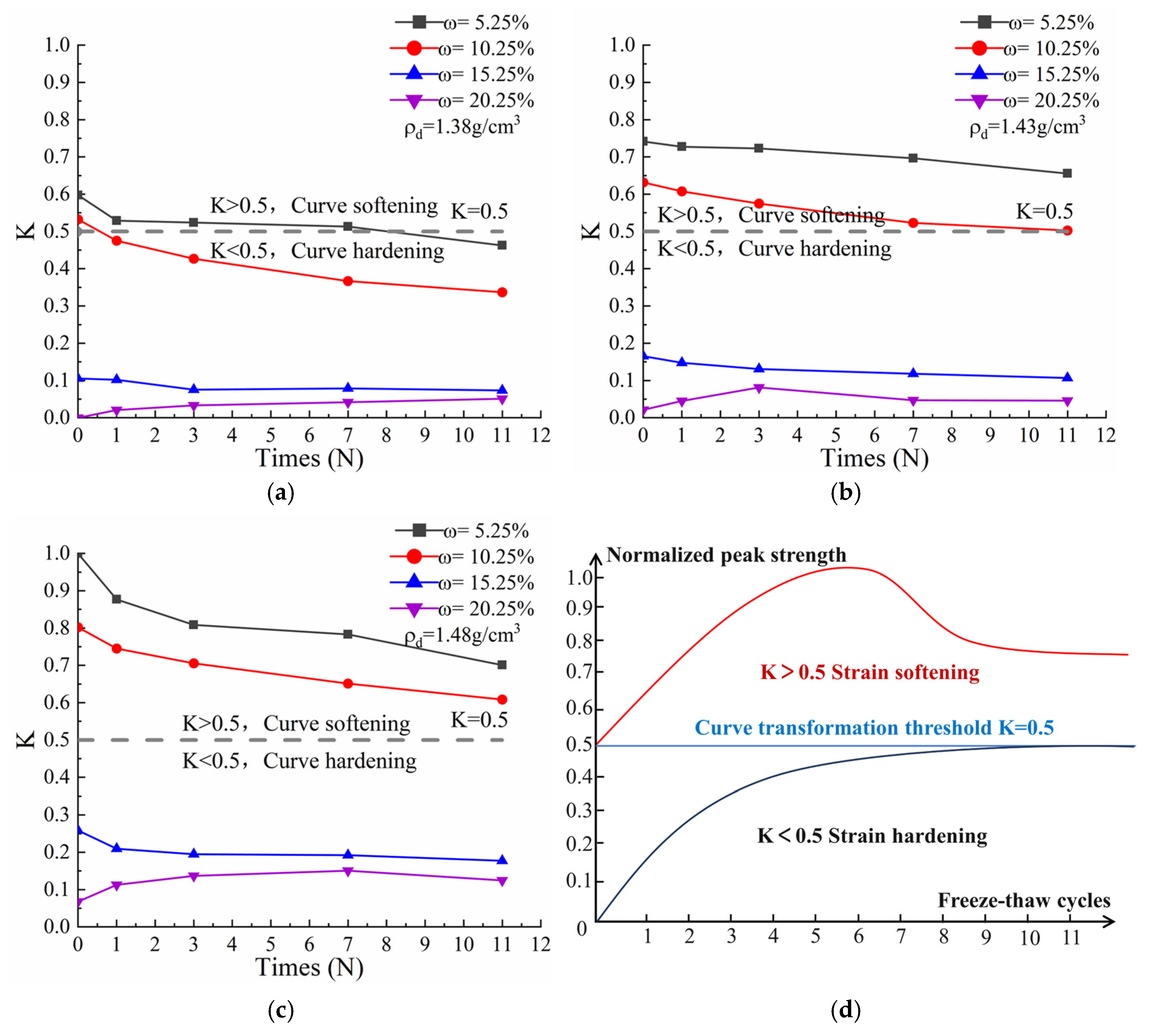

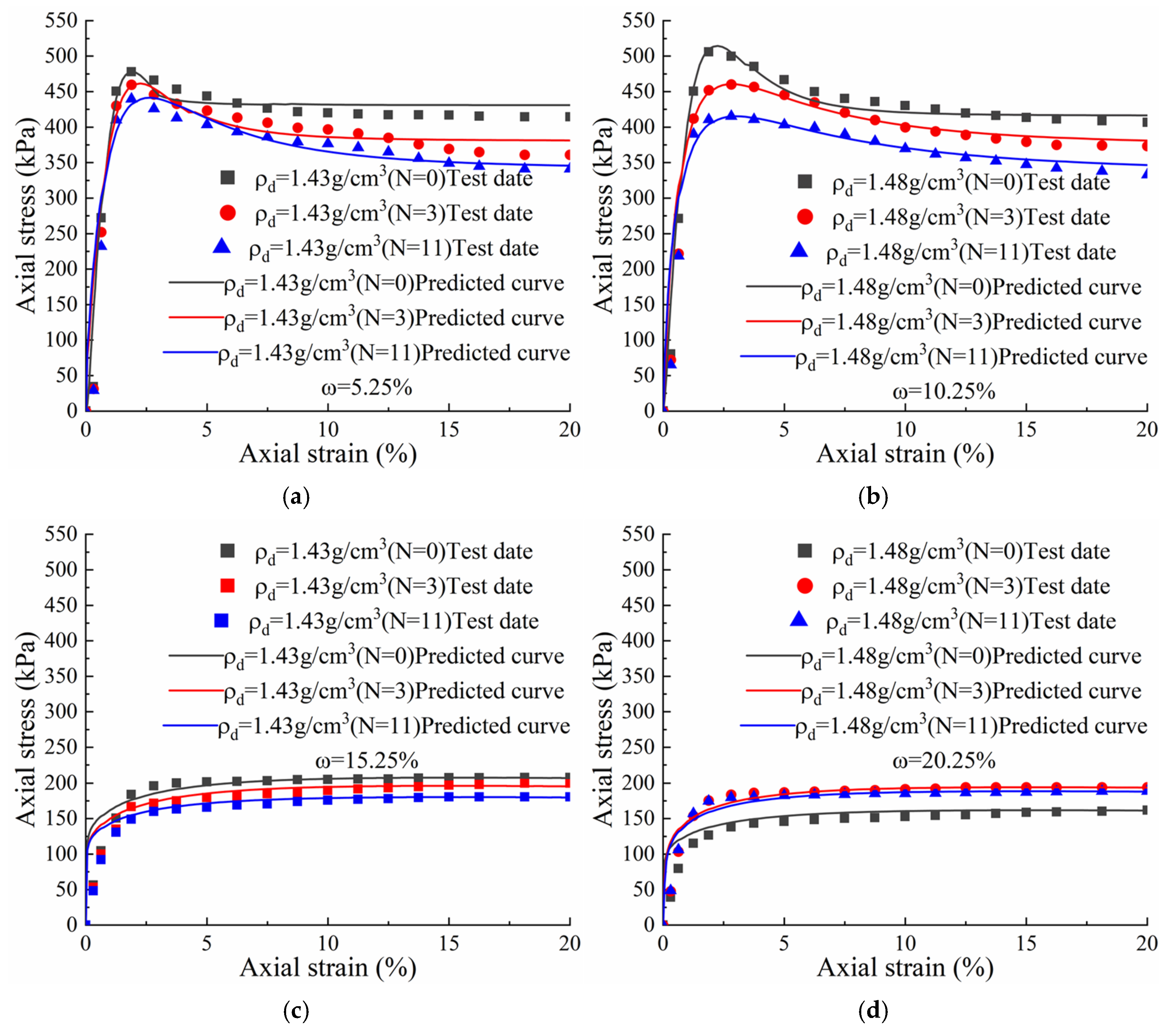

4.2. Model Validation

The statistical constitutive model of loess damage established in this paper was verified using unconsolidated undrained triaxial test data. Examples with water contents of 5.25% and 15.25% and dry densities of 1.43 g/cm

3, as well as examples with water contents of 10.25% and 20.25% and dry densities of 1.48 g/cm

3 were used for this verification. When K > 0.5, the residual strength can be obtained directly from the stress–strain diagram. When K < 0.5, the residual strength is estimated using the empirical value of

. The parameters required for the model can be obtained from

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7, which show the experimental data. The model curve is shown in

Figure 15. As

Figure 15 shows, under unfrozen–thawed conditions of shallow Ili loess, the theoretical curve of the unconsolidated undrained triaxial test generally agrees well with the experimental values.

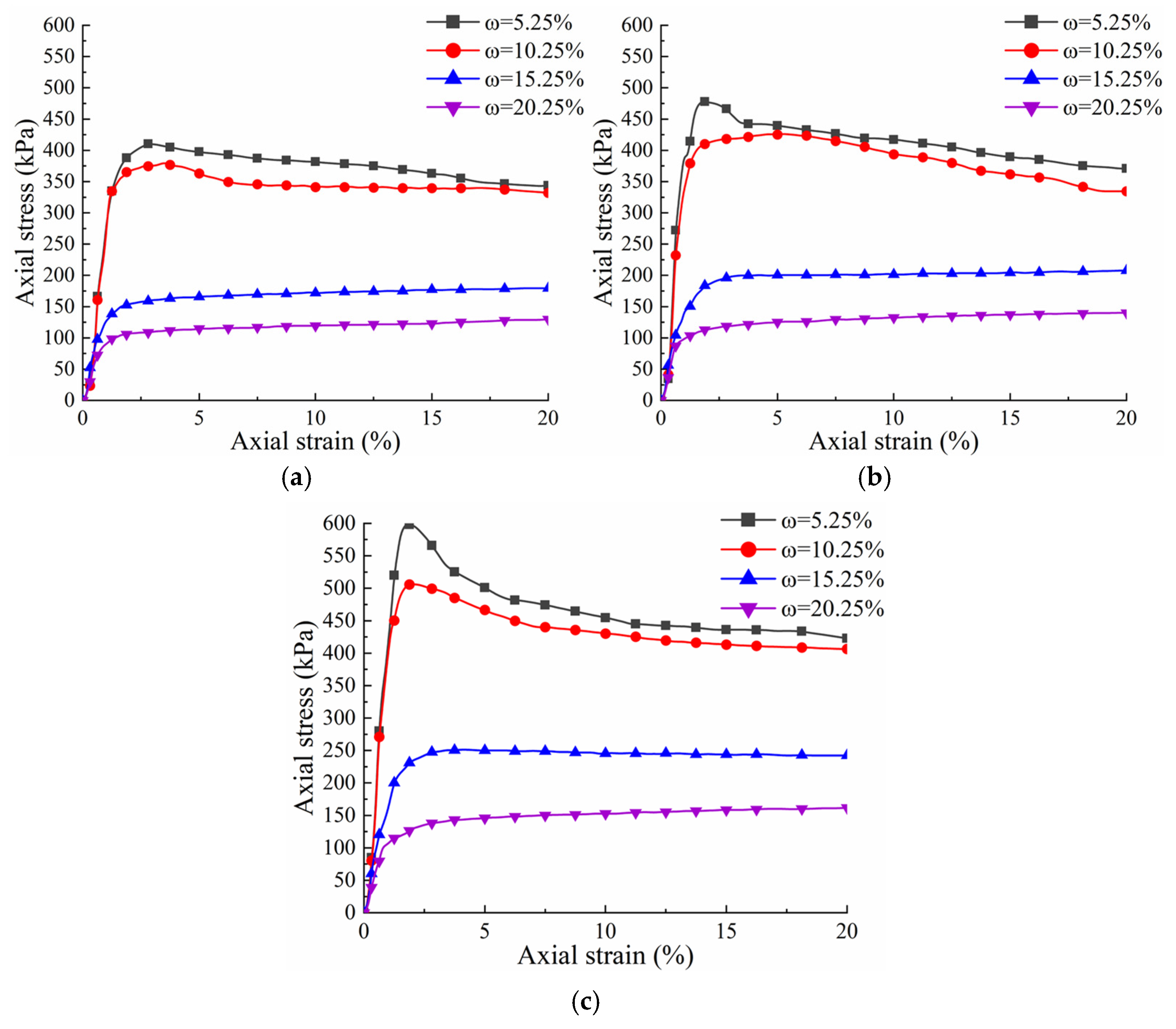

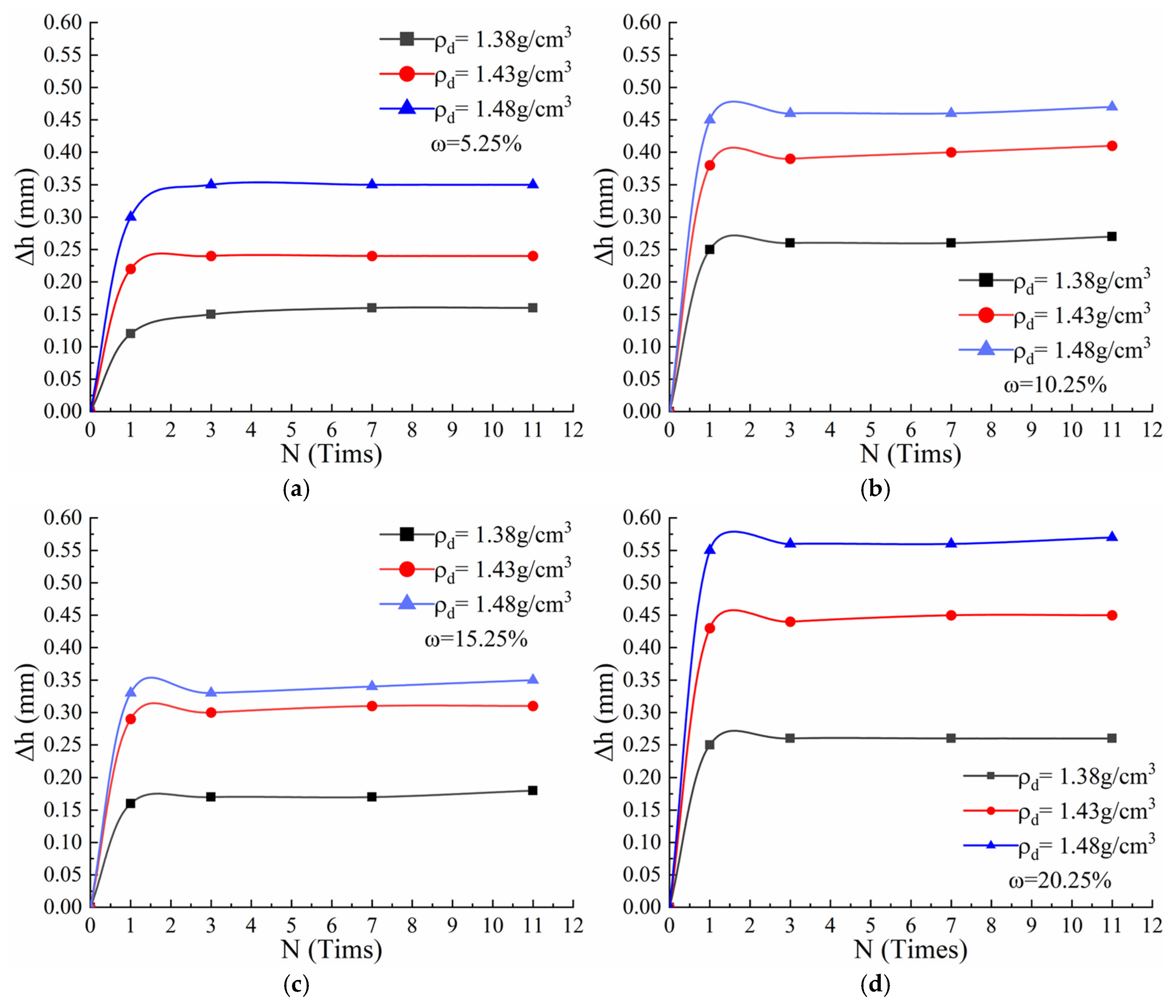

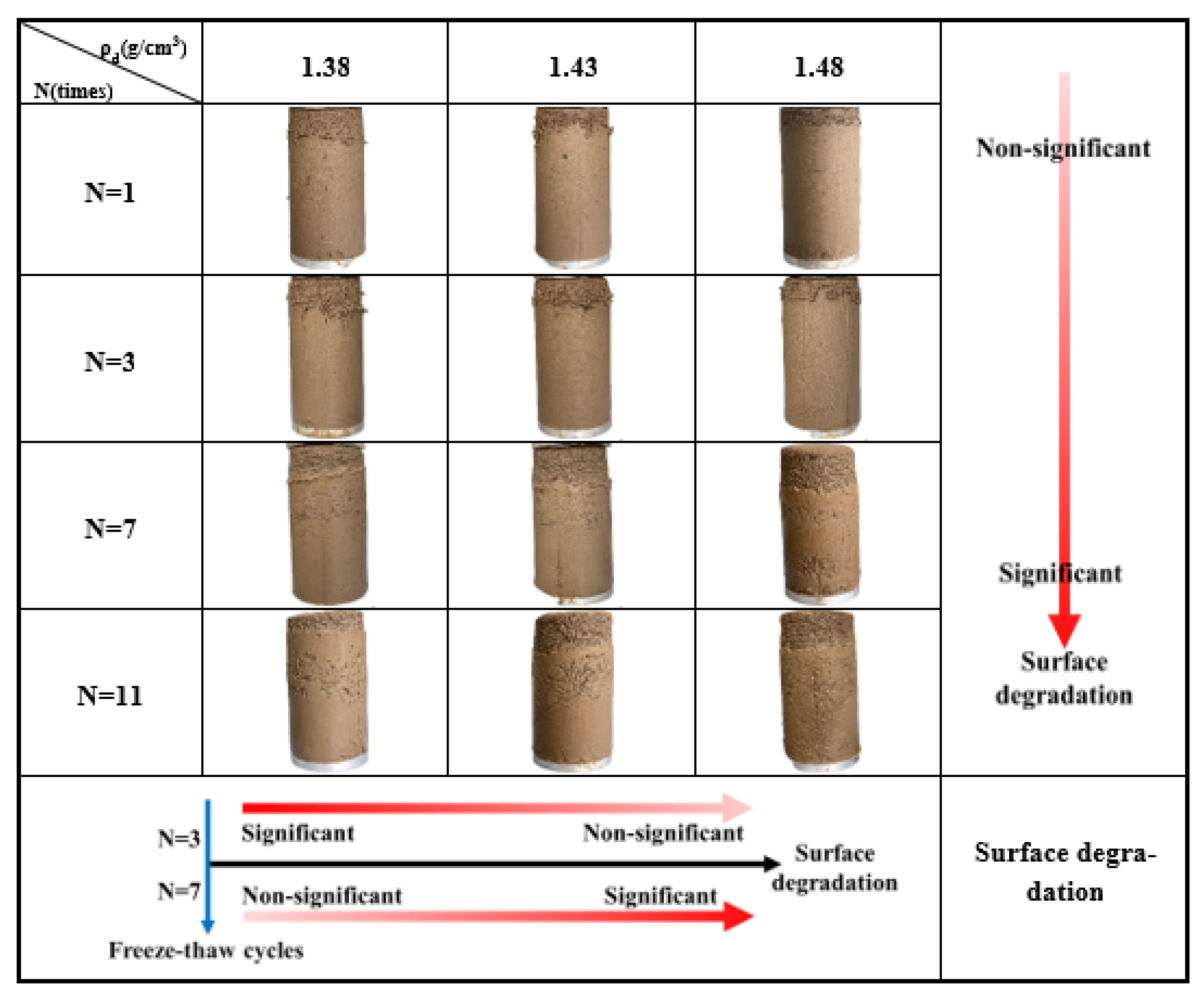

As can be seen in

Figure 15, the peak strength of the theoretical curve decreases as the number of freeze–thaw cycles increases. The peak strength also decreases as the water content increases and the curve changes from strain softening to strain hardening. The peak strength of the theoretical curve increases as dry density increases. At a low water content, the curve exhibits strain softening, whereby stress initially increases rapidly before decreasing gradually. Conversely, at a high water content, the curve exhibits strain hardening, whereby the stress initially increases rapidly before slowly rising. The theoretical and test curves exhibit a similar trend. To predict the stress-strain curve under different water contents and freeze–thaw cycles. A relationship be established between the elastic modulus, peak strength and residual strength, corresponding to dry densities of 1.38, 1.43 and 1.48 g/cm

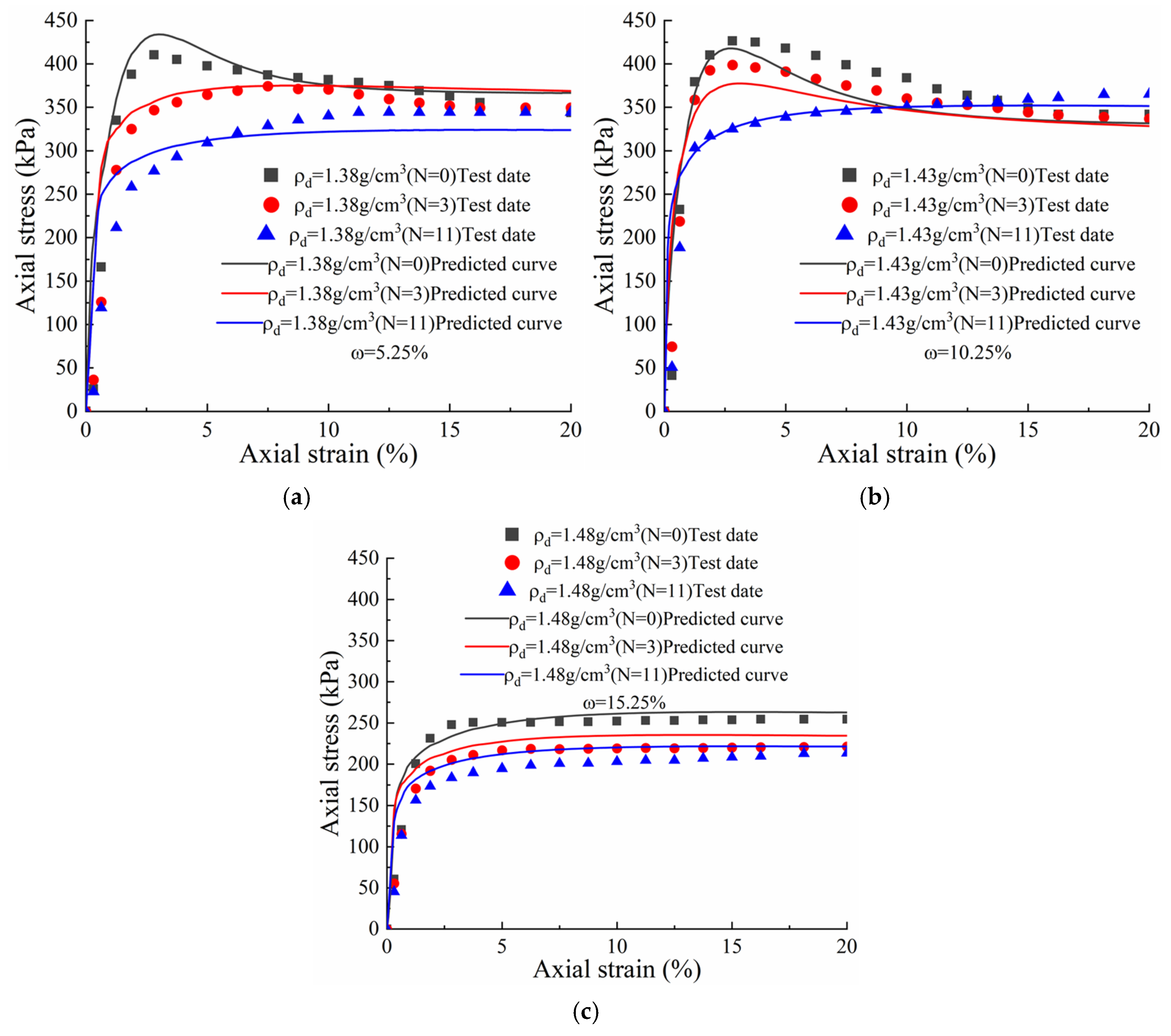

3, and freeze–thaw cy-cles and water content. As follows (31):

In the formula: is the water content; is the number of freeze–thaw cycles; is the elastic modulus; is the peak strength; is the residual strength. and are material parameters related to freeze–thaw testing.

Their calculated values are shown in

Table 8,

Table 9 and

Table 10. The strength parameters are calculated using the above equation and then substituted into the constitutive model to obtain the predicted curve. This curve is then plotted and compared with the experimental data, as shown in

Figure 16.

The inaccuracies between the experimental values and theoretical values of the elastic modulus, peak deviation stress, and residual deviation stress is obtained by comparing the predicted curve with the experimental curve. The inaccuracies between the experimental values and the predicted theoretical values is calculated using the following Equation (32):

In the equation:

is the experimental test value,

is the empirical predicted value, and

represents the elastic modulus, peak strength, or residual strength. It can accurately predict within 20%, referencing

Figure 17. It is evident that Equation (31) provides relatively accurate predictions for soil strength, elastic modulus, and residual strength, thereby offering theoretical support for engineering projects in the Ili region.

In summary, the constitutive model established in this paper effectively predicts the mechanical characteristics of Ili loess under wet–dense-freeze–thaw cycles. The overall trend is consistent with the experimental results and reflects the changes in damage to the stress–strain relationship of Ili loess under cyclic conditions. Consequently, the proposed damage statistical constitutive equation can relatively accurately describe the strength and damage characteristics of Ili loess in the Xinjiang region.