1. Introduction

Aerospace-grade AA2060 aluminium alloys are highly regarded for their remarkable mechanical properties, characterised by a high strength-to-weight ratio and exceptional corrosion resistance. This renders them highly desirable for integration into critical structural components in the aviation and space industries, where weight optimisation is of utmost importance. However, their application is impeded by notable challenges in welding, particularly when employing welding techniques. One such technique that has gained increasing significance in the industrial sector is powder-based additive manufacturing, in which structural components are produced layer by layer, allowing geometries that would otherwise be impossible [

1]. The main disadvantages of powder-based methods are the size of the printable parts and the low deposition rate, which increase the production time [

2,

3]. As a result, arc-DED (directed energy deposition) using wire as the raw material has become popular for printing large structures [

4,

5]. In comparison to other arc-DED processes [

6,

7], plasma metal deposition (PMD) offers higher depth-to-width ratios, better temperature control, and higher deposition rates among the available heat sources [

8,

9]. These are particularly important for Al alloys, which are difficult to deposit [

10,

11,

12].

DED processes have gained traction in industrial manufacturing. However, despite their promise, the integration of Al-Cu alloys into these processes has encountered significant hurdles [

13,

14,

15]. Reducing the defects in AA2060 components that are WAAM-fabricated has been crucial [

16]. One of the main challenges in AM of Al alloys is the thin layer of alumina that forms on the surface of the feedstock wire. This oxide layer has a remarkably higher melting temperature (2037 °C) compared to Al (660 °C), which hinders proper fusion. Additionally, porosity attributed to hydrogen entrapment during solidification and the presence of oxide films on the wire surface can compromise the integrity of the built parts [

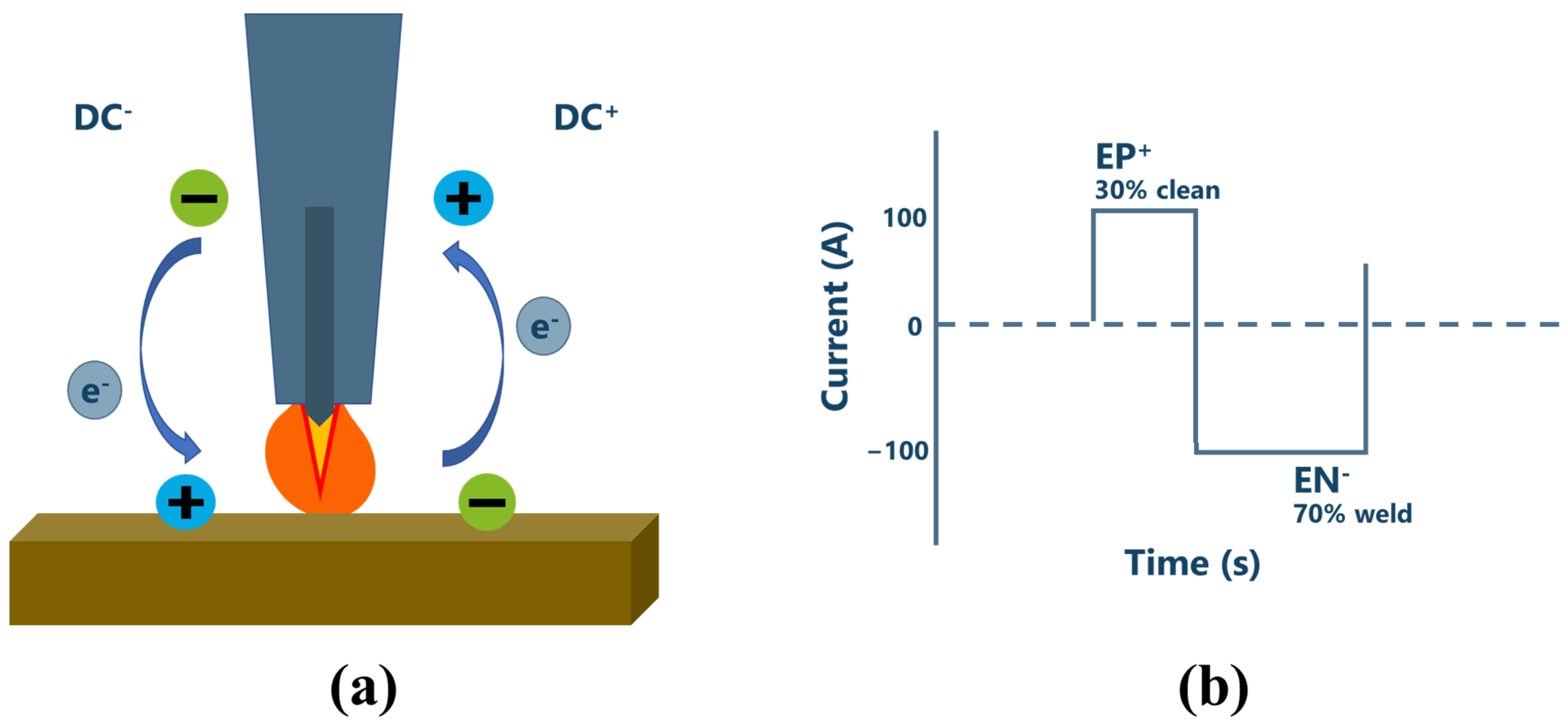

17]. However, because the plasma metal deposition (PMD) technique works with alternating current (AC), it is possible to circumvent these issues (

Figure 1a). The waveshape controls in AC mode are frequency and balance; the standard values used are 75% EN and 85 Hz. The reverse polarity part of the AC cycle removes the alumina layer via an electrode positive (EP) current, while the straight polarity part, responsible for melting and depositing the Al alloy, is performed using an electrode negative (EN) current (

Figure 1b) [

18]. For aluminium alloys, the AC mode is particularly interesting since it enables the single track to be heated and the oxide layer to be cleaned.

Despite their promise, commercially available wires suitable for WAAM are currently lacking. A powder metallurgy (PM) route was selected for the development of metallic wires because of its favourable characteristics. PM routes utilise powders as feedstock, allowing chemical compositions to be tailored through simple adjustments in element percentages and enabling a wide range of alloy design possibilities. Furthermore, industrial forming processes based on PM extrusion techniques can produce fully dense or porous metallic alloys with enhanced performance [

19,

20]. For copper and aluminium rod feedstocks, certain extrusion methods—such as the Conform™ process—allow continuous wire fabrication without prior powder compaction [

21]. However, when applying PM-derived Al–Cu–Li alloys (such as AA2060) in WAAM, additional challenges arise. During deposition, these alloys may experience significant elemental losses, particularly in lithium and magnesium, which are critical for strengthening mechanisms and overall mechanical performance. Therefore, understanding and mitigating such losses is essential to preserve the designed composition and achieve consistent properties in the fabricated components. Addressing these challenges is key to unlocking the full potential of AA2060 alloys for aerospace and other high-performance applications.

In this work, an Al-Cu-Li wire was designed and employed using the PMD technique to control solidification during welding. In this process, loose starting powders were consolidated to produce cold-drawn wire with a diameter of less than 5 mm, ultimately producing 1.2 mm-diameter AA2060 wires. The aim of this study was to develop powder metallurgy wires with the AA2060 alloy as an alternative feedstock and to investigate their deposition behaviour, microstructure evolution, and mechanical properties using plasma metal deposition (PMD).

2. Materials and Methods

The starting powders comprised elemental particles of Al, Cu, Mn, and Zn, along with Mg and Li added as master alloys (92.1%wt. Al/7.9%wt. Mg and 80%wt. Al/20%wt. Li) (

Table 1). The density obtained by the helium pycnometer (AccuPyc 1330; Micromeritics Instrument Corp., Norcross, GA, USA) for the 2060 alloy was 2.7022 g/cm

3. The powders were homogenised by dry blending for 1 h in a multidirectional mixer (Turbula

®; Willy A. Bachofen AG (WAB-GROUP), Muttenz, Switzerland).

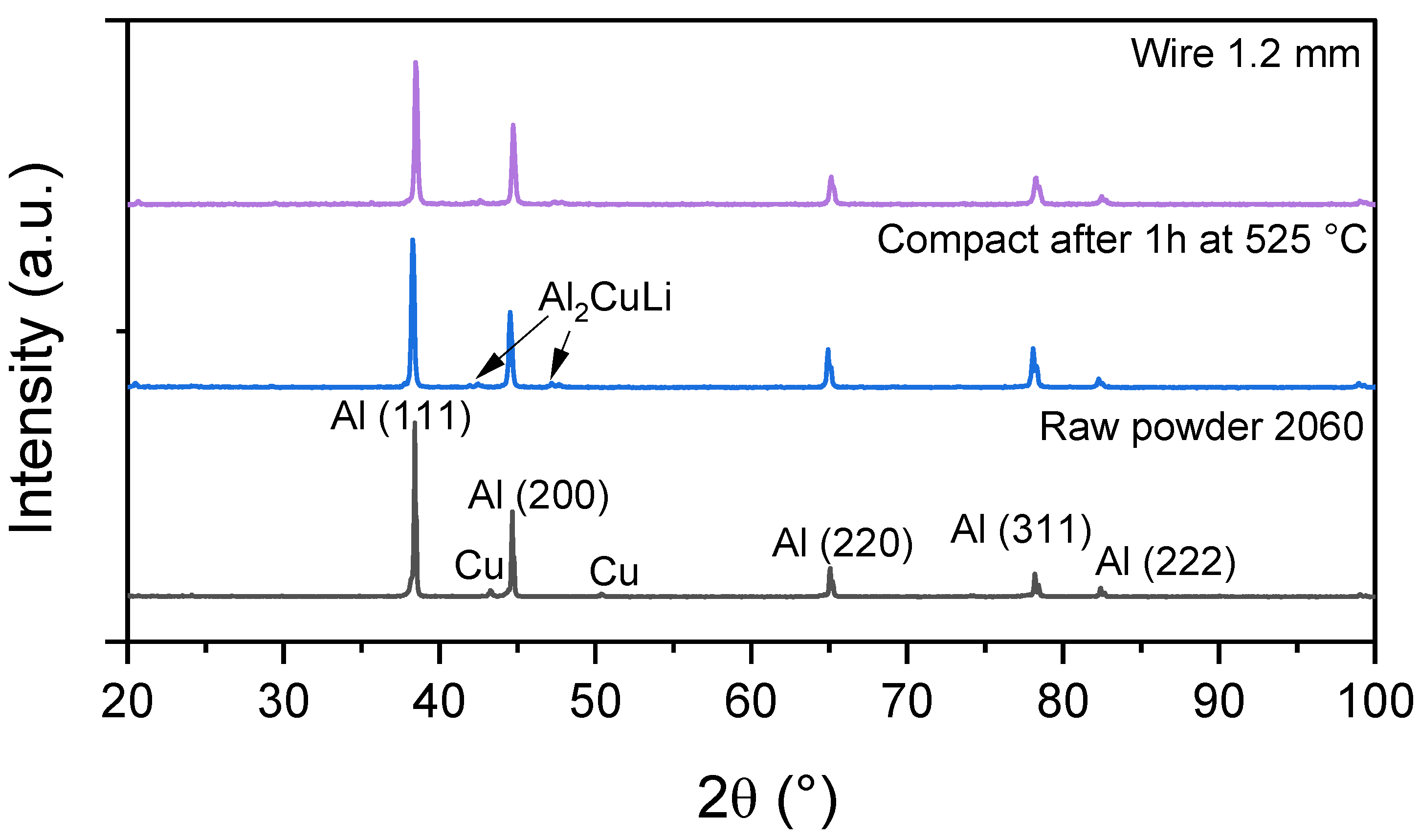

The wires were then manufactured through the PM route. Before the compaction stage, compressibility curves were obtained for the 2060 alloy, which aided in selecting the compaction pressure for subsequent stages. Subsequently, the powder was pressed in a cold isostatic press (EPSI Systems, Cold Isostatic Press (CIP), Temse, Belgium) at 400 MPa to achieve a high compact density and minimise porosity. The dimensions of the CIP compacts were 9 cm for the length and 5 cm for the diameter. The compacts were heat-treated at 525 °C in a N

2 atmosphere for 1 h, following previous studies on this alloy [

22,

23]. These studies have shown that the presence of precipitates clearly indicates the proper dissolution of elemental Cu particles into the Al matrix after 1 h at 525 °C. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed using a Philips (Philips, MA, USA) diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å), operating at 40 kV and 40 mA. Data were collected over a 2θ range of 20–100° with a step size of 0.05° and a counting time of 3 s per step. The Al

2CuLi phase was identified in samples heat-treated at this temperature by XRD (

Figure 2), which was considered an optimised treatment for a homogenous microstructure according to the literature [

24].

Finally, the company LKR produced the wires in two stages: preheating of the billet (<500 °C) in an Ar atmosphere, followed by T-supported pressing until wires with a diameter of 1.6 mm were obtained. The resulting wires had a final diameter of 1.2 mm, all ranging in length between 4 and 6 metres. A LECO oxygen analyser was used to verify the oxygen content in the wire, which was found to be around 0.2 ± 0.1% O2.

The additive manufacturing (AM) equipment employed was developed by SBI additive manufacturing systems and operates based on plasma metal deposition (PMD) technology. During the welding process, a current of 120 A, a travel speed of 0.9 m/min, and a plasma gas flow rate of 0.3 m/min were applied, based on previous results obtained for optimising process parameters in the same welding device using a commercial 2319 alloy, which has a similar chemical composition [

25]. The molten pool was shielded by a protective atmosphere composed of Ar/He15/N0.015, with a shielding gas flow of 10 L/min and a plasma gas flow of 0.8 L/min. A potential of 20 V was used to inject the gas between the electrode and the copper flask, thereby generating a stable plasma. A detailed characterisation of the commercial AA2319 alloy was conducted, leading to the selection of the process configurations and conditions, which have been extensively described in previous work [

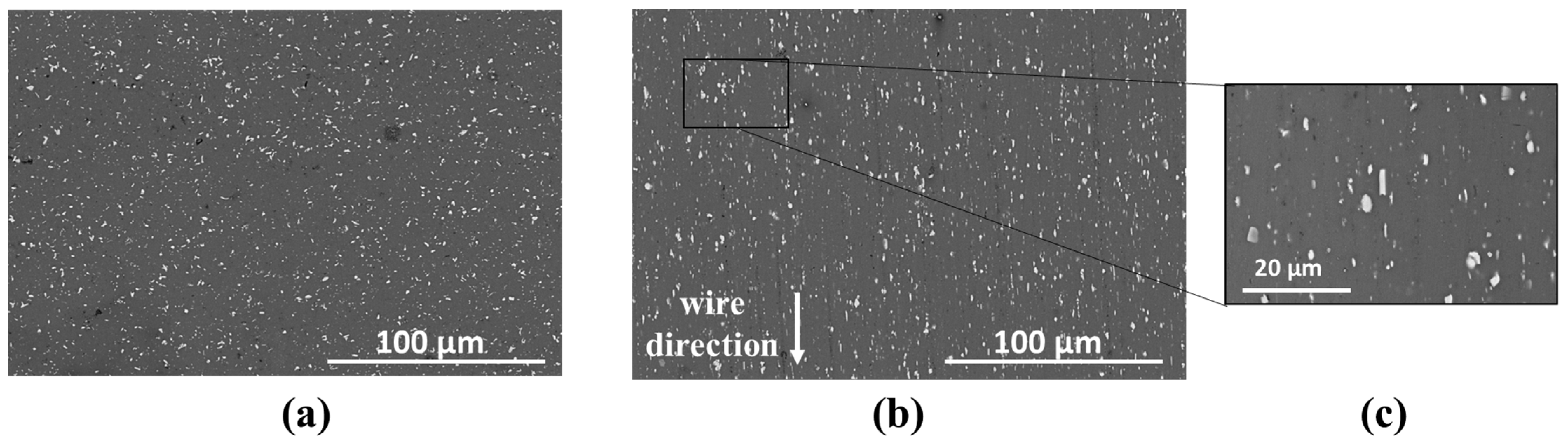

25]. The wires derived from the rods were welded and deposited onto two aluminium alloy substrates, 5083 and 7075, each with dimensions of 10 mm × 20 mm × 100 mm. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) revealed a uniform microstructure, as illustrated in

Figure 3. The bright particles corresponded to 28.5 wt.% Al and 71.5 wt.% Cu, consistent with the expected composition for 2xxx series alloys.

Table 2 displays the chemical composition of the substrates. The use of two different substrates, 5083 and 7075, provides a comprehensive evaluation of the welding and deposition process due to their differences in thermal conductivity. Although differences in mechanical properties and corrosion resistance are not directly related to deposition behaviour, thermal conductivity is directly related to the process. Alloy 5083 offers excellent corrosion resistance and ductility but moderate strength, while alloy 7075 provides high strength but lower corrosion resistance. More commonly used substrates, such as 2024 or 6061, have a high Cu content and a strong tendency toward brittle solidification and crack formation during welding, which could complicate the study of PM Al-Cu-Li wire welding behaviour. In contrast, 5083 (Al-Mg) and 7075 (Al-Zn-Cu) allow the investigation of substrate effects on weldability, microstructure, and porosity in alloys with different strengthening mechanisms: solid-solution versus precipitation hardening.

The first deposition is crucial; since a multi-layered piece forms from the stacking of many layers, it is important to understand the potentially decisive influence of the initial substrate. The substrate’s working area was preheated by repeatedly passing the plasma torch over it without depositing material and by employing a ceramic pad heater placed beneath the substrate until the temperature had reached 180 °C. This preheating step aimed to reduce sharp thermal gradients, improve layer adhesion, and allow for more controlled solidification, thus enhancing the quality of the deposit and reducing internal residual stresses. Single-track deposits were performed from left to right over a length of 70 mm.

The microstructures of the single tracks were examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Conventional metallographic procedures were employed in the preparation of the samples. Samples were cut on the side and the middle of the single layer. The alloying elements were identified by energy dispersive X-ray analyser (EDS) spectroscopy. The chemical analysis was conducted using the SPECTRO Arcos model, Perkin Elmer Optima 3300DV, and inductively coupled plasma–optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES). The specimens were treated using the digestion process, which involved dissolving them in an aqueous nitric acid solution and heating them in the oven to 100 °C for two days. To verify if the method was effective, measurements were performed in duplicate in an aqueous solution of 10% nitric acid. Finally, Vickers micro-hardness tests (0.5 HV) were also performed by a Zwick Roell micro-hardness instrument (Zwick Roell, DE), and the data analysis was performed using the hardness testing software ZHμ.HD (Zwick/Roell,

https://www.zwickroell.com; accessed 1 May 2022).

3. Results

The comparison between the 7075 substrate and the 5083 substrate showed that the material deposited on the 7075 substrate presented a higher density of pores. This difference in behaviour can be attributed to the different thermal conductivities of the substrates. Alloy 5083 exhibits a thermal conductivity of 120 W/(m·K) [

26], whereas alloy 7075 exhibits a higher conductivity of 134 W/(m·K) [

27]. The higher thermal conductivity caused the melt pool to solidify more rapidly due to faster heat dissipation. Consequently, the deposited material on the 7075 substrate was narrower than that on the 5083 substrate.

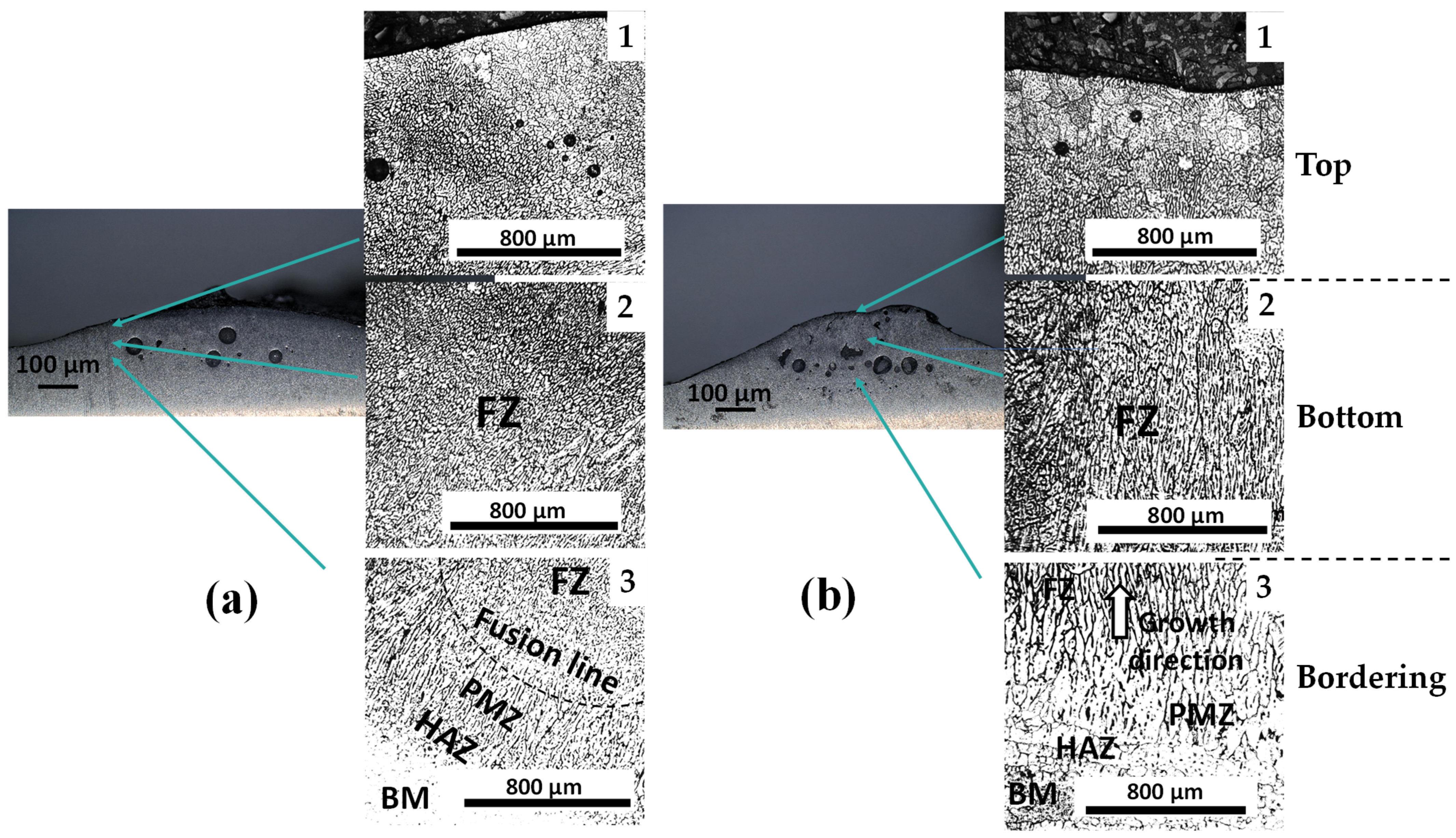

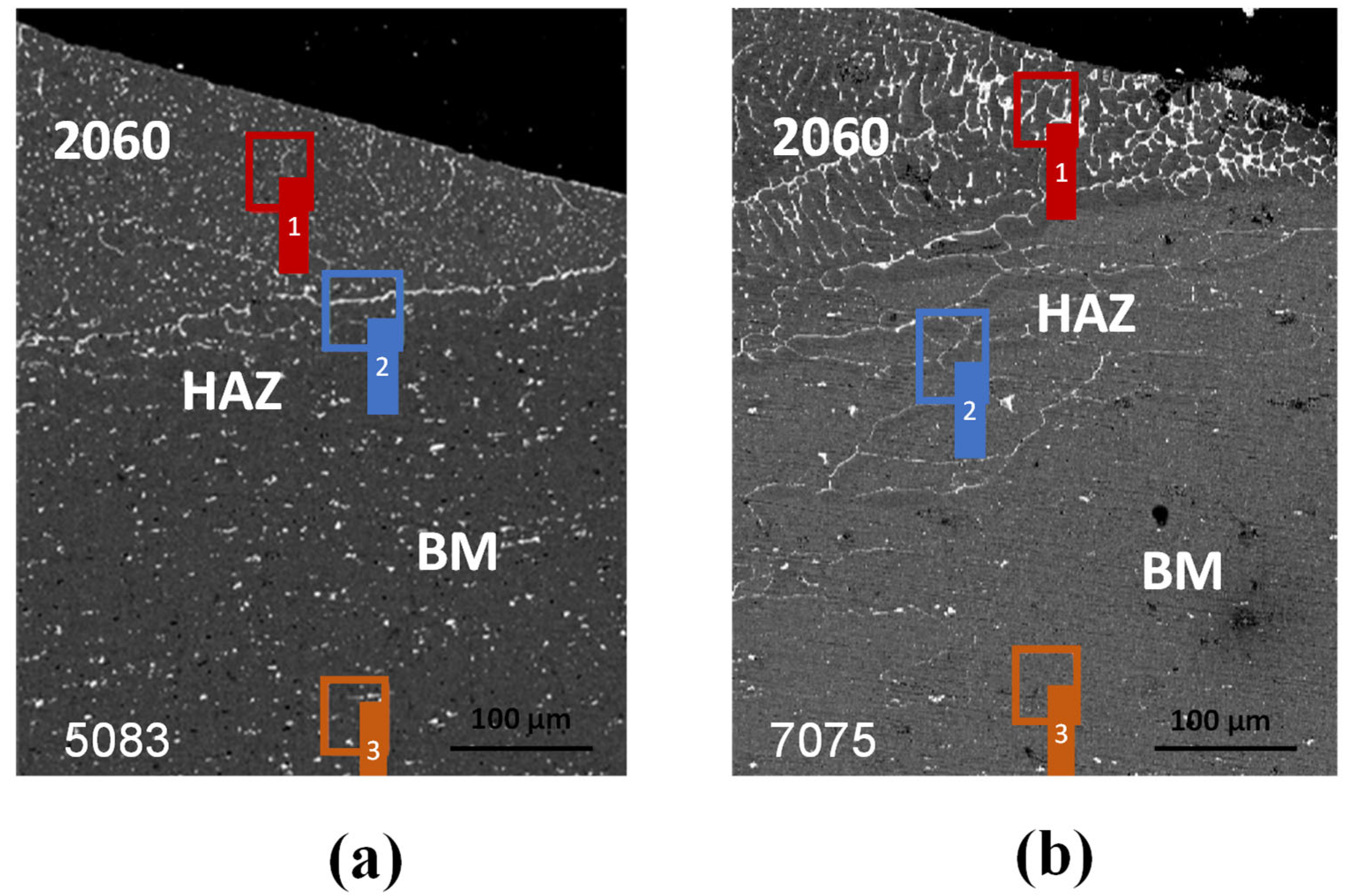

Microstructural analysis of the weld bead cross-sections (

Figure 4) was performed using optical microscopy (OM). Spherical pores were observed within the material formed during the welding process. Such porosity is a common defect caused by gas entrapment during solidification, when poor shielding gas or the substrate’s reactivity with hydrogen or oxygen allows atmospheric gases to infiltrate the molten pool. The careful optimisation of processing parameters may help mitigate porosity, since the parameters employed here were based on prior optimisation studies using commercial wires. Further systematic investigation is required to establish the quantitative relationship between parameter selection—such as the values of alternating currents used for this alloy—and porosity reduction.

Figure 4a,b show OM images of the cross-sections of single tracks after welding, revealing four distinct regions: the heat-affected zone (HAZ), transition zone (TZ), fusion zone (FZ), and base material (BM). The fusion zone and deposited material are highlighted in

Figure 4a,b, region 1. At the top of the deposits, the microstructure consists of equiaxed grains, while adjacent regions display different morphologies: the 5083 substrate shows equiaxed grains near the fusion boundary (

Figure 4a, region 2), whereas the 7075 substrate exhibits columnar grains (

Figure 4b, region 2). The weld interface extending into the TZ is visible in

Figure 4a,b, region 3. The HAZ presents characteristics of both the BM and TZ. In

Figure 4a, region 2, the fusion line is well defined, and the TZ includes a partially melted zone (PMZ) along with the HAZ. This structure results from grains growing along the direction of the steepest thermal gradient, while the central part of the deposited material forms equiaxed grains due to local cooling conditions. In the 7075 substrate, columnar grains from the BM served as nucleation sites for the deposited tracks, with the solidified structure extending above the fusion line. Columnar grains were also observed within the deposited material (

Figure 4b, region 3). SEM images from one side of the single tracks are shown in

Figure 5, identifying the deposition zone, HAZ, and BM. First, the deposition on the 5083 substrate exhibited a uniform composition with evenly distributed alloying elements, and the fusion line was sharply defined (

Figure 5a). In contrast, the 7075 substrate showed more segregation of alloying elements near the bead edge, as seen in the upper-right area of

Figure 5b. Additionally, the HAZ showed deeper penetration, and the fusion line appeared more diffused compared to that of the 5083 substrate.

EDS analyses of the three sections were carried out to confirm the elemental composition of these regions (

Figure 5). The findings are summarised in

Table 3.

Areas 1 and 2 displayed reduced Cu levels compared to the deposited alloy, with some Cu apparently having diffused into the BM region during deposition on the 5083 substrate. Moreover, as can be seen in

Figure 5a, Cu segregated at the grain boundaries, mainly along the fusion line. Previous studies have observed Cu-rich phases in both welded interfaces and the deposited materials of Al-Cu-Li alloys fabricated via additive manufacturing [

28,

29]. According to Zhong et al. [

29], XRD analysis revealed that Al

2Cu, in addition to Al

3Li, was present as a secondary phase in WAAM components. Segregation of the main alloying elements was found at the grain boundaries, thereby promoting the formation of different phases during the solidification process. This phenomenon also appeared to take place in our deposited materials, with the bright regions potentially indicating the presence of Cu-rich precipitates. This interpretation is supported by the EDS analysis in

Table 3, which indicates an increased Cu concentration in these regions.

Furthermore, a high concentration of Mg was found in this region, likely originating from the substrate; this Mg also promotes the development of new phases in the grain boundaries. In Area 2, the fusion line was composed of Al-Cu, Al-Cu-Mg, and other phases rich in Zn. As a result, alloying elements from the 2060 wire and the 5053 substrate base material contributed to phase formation in this area. Finally, a low Cu level of 0.4 wt.% was found, consistent with the base material (BM) in Area 3. This region was also enriched with Mg due to the high Mg content of 5.7 wt.% in the 5083 substrate.

In Area 1 of the 7075 substrate, EDS revealed Cu-, Zn-, and Mg-rich phases formed from the alloying elements of the 2060 wires and substrate. Area 2, representing the HAZ, exhibited a composition nearly identical to the BM, indicating that the microstructural changes were driven by heat rather than compositional variations.

The formation of a columnar grain structure in this area can be attributed to the high thermal conductivity of the substrate, which leads to rapid cooling rates that limit the diffusion of alloying elements during solidification. Finally, the elemental composition measured in Area 3 matched the nominal ranges of the 7075 substrate for Zn, Mg, and Cu (Zn: 8.2–5.7 wt.%, Mg: 4.3–3.2 wt.%, and Cu: 1.15–1.22 wt.%).

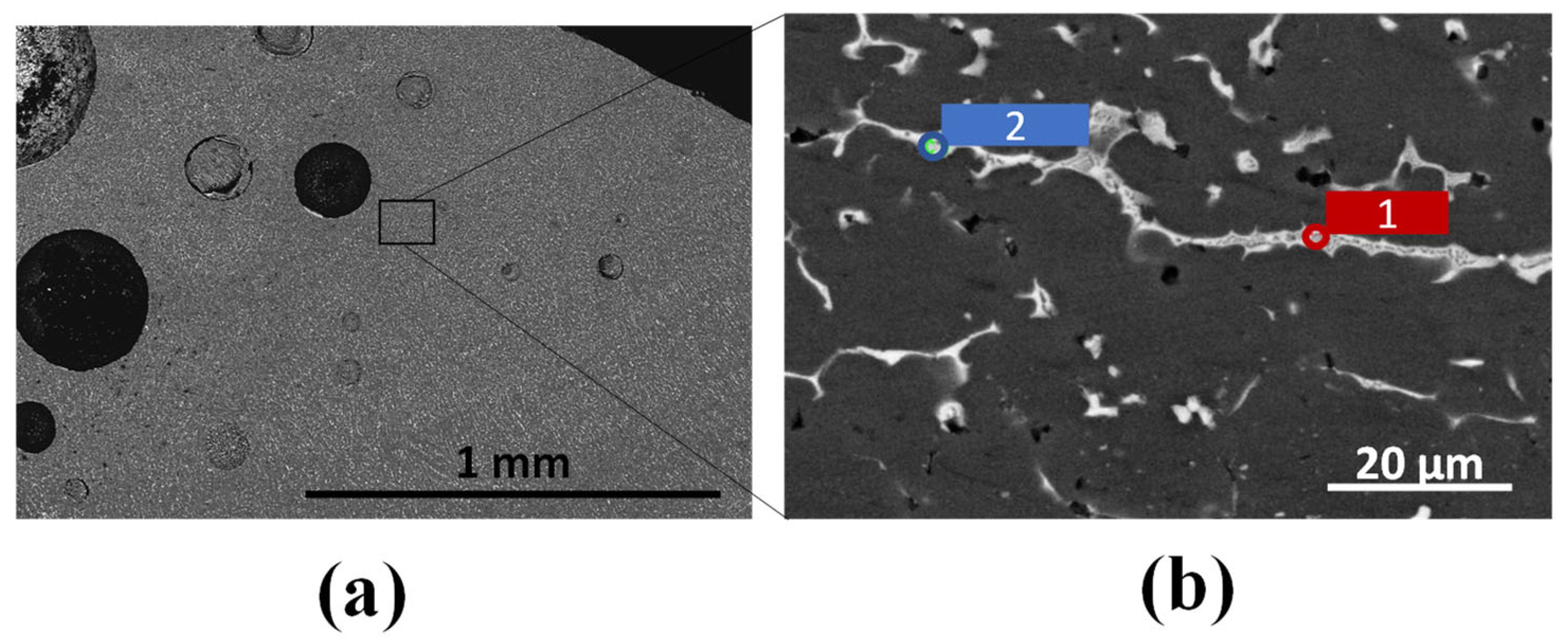

Figure 6 shows the 2060 wire deposited on a 5083 substrate, with SEM images at low magnification (

Figure 6a) and high magnification (

Figure 6b). Micrographs revealed round pores, and EDS analyses showed compositions of 80 at.% Al, 22 at.% Mg, and 8 at.% Cu for spot 1, and 86 at.% Al, 6 at.% Mg, 5 at.% Mn, and 3 at.% Cu for spot 2. These data confirm the presence of Al

2Cu and Al

2CuMg phases after welding, in agreement with previous observations.

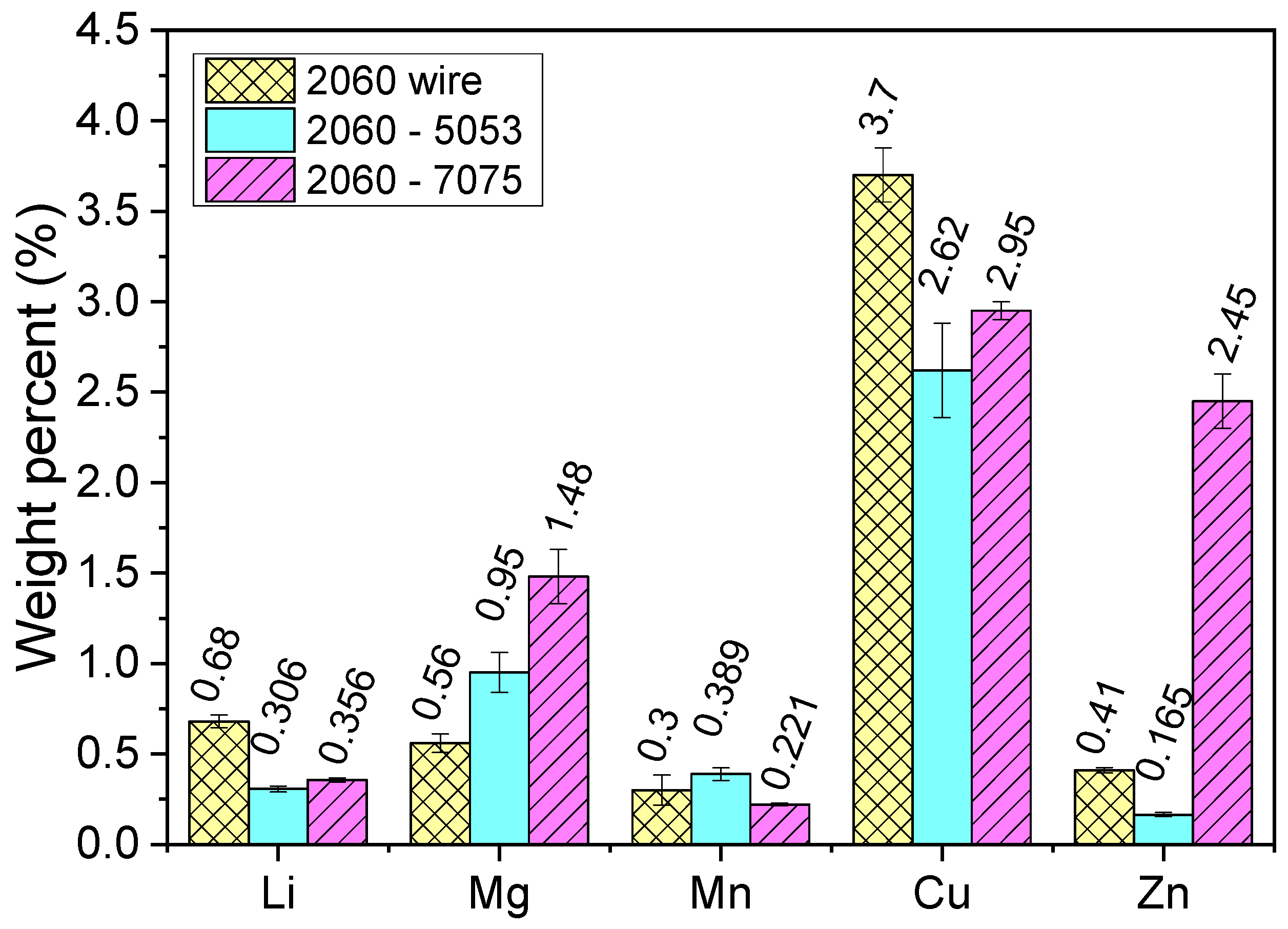

ICP-OES quantitative analysis was also used to assess the chemical composition of the deposits to control the changes in the alloying elements during the welding process (

Figure 7).

Following post-PMD welding on both substrates, the Li concentration in the welds was about 55 wt.% lower than in the wires. Since Li is the smallest and most volatile alloying element, the high-temperature deposition process facilitates its evaporation. The diffusion of Mg and Zn from the substrate into the molten pool during welding accounts for the increased weight values of these elements. This effect was observed to be significantly higher in the case of the 7075 substrate, which had higher initial concentrations of Zn and Mg compared to the 5083 substrate. The Mn content in 5083 deposits remained virtually constant, consistent with the high Mn content and excellent thermal stability of this alloy. On the other hand, a loss in Mn weight was observed in the 7075 deposits. Cu showed a decrease of about 25 wt.% compared to the original wire composition for both substrates, probably due to evaporation during the thermal cycle.

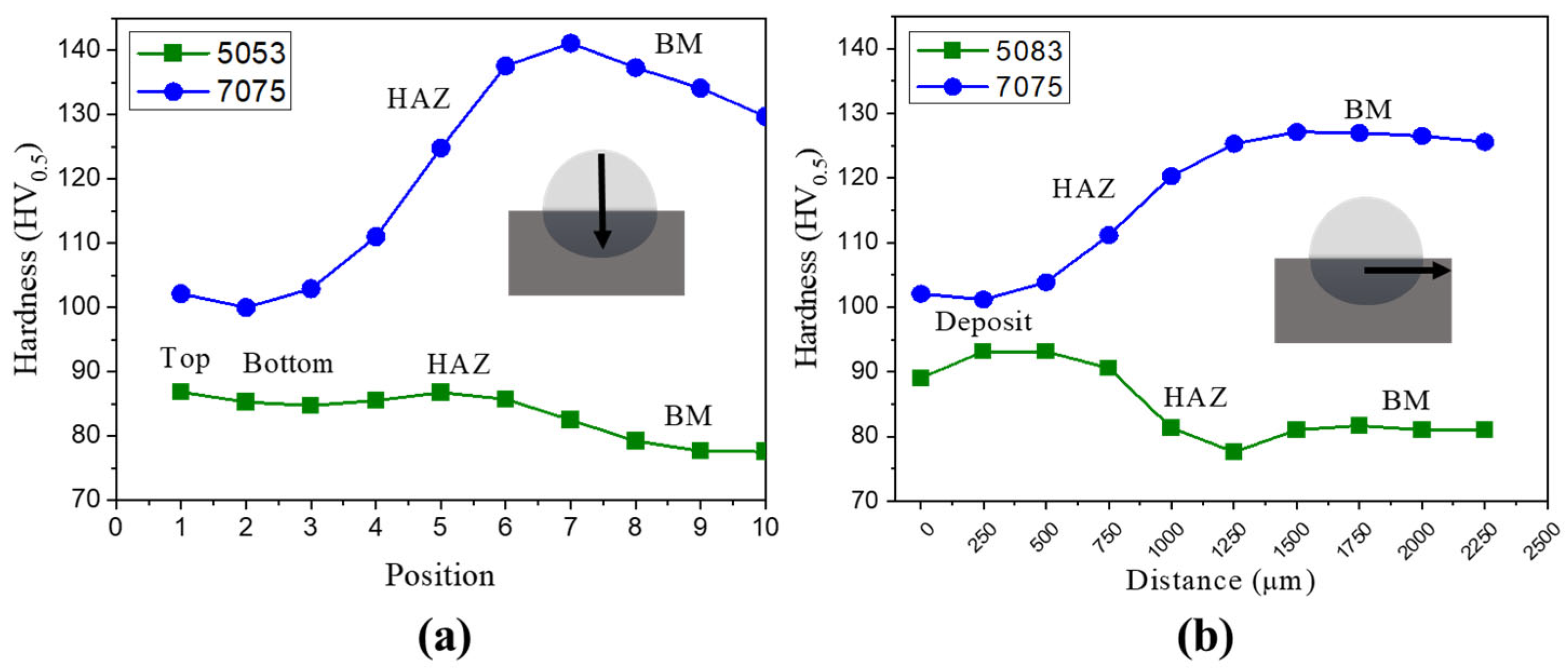

The hardness measurements were combined with the measured compositional data to assess correlations between alloying element concentrations and mechanical behaviour. Hardness measurements were taken along two directions: through the deposited material from top to bottom, and parallel to the base metal surface, from the centre of the deposited track into the base material.

Figure 8a shows that a higher overall hardness was achieved in the single-track deposited on the 7075 substrate. At the bottom, the 2060 weld track was substantially enriched with alloying elements, such as Mg and Zn, in the solid solution provided by the 7075 base material. Since Mg and Zn contribute to solid-solution strengthening and promote the formation of hard intermetallic precipitates, such as MgZn

2 in 7xxx alloys [

30], this enrichment correlates with the higher hardness observed, which increased from 105 HV to 140 HV.

On the other hand, the hardness profile of the weld track on the 5083 substrate shows that the hardness increased slightly towards the bottom of the deposited material, reaching around 78 HV, and then remained nearly constant in the baseplate. ICP-OES analysis revealed a higher Mn content for the single tracks on the 5083 substrate, which acts as a grain refiner and provides thermal stability [

31]. This effect explains the tendency for the hardness to remain relatively constant despite the thermal history. The high Mn content contributes to a more uniform mechanical response and consistent properties in 2060 alloy deposition.

Figure 8b shows the formation of a heat-affected zone (HAZ) adjacent to the fusion line, as indicated by the hardness profiles measured parallel to the base material surface. The 5083 substrate exhibited a decrease in hardness in this region, whereas the 7075 substrate showed an increase. These differences occur because the HAZ, which is a part of the metal that has not melted, has been exposed to heat, changing its characteristics. For the 5083 substrate, the average hardness of the deposited material was 93 HV; this dropped to about 78 HV in the HAZ and 81 HV in the unaffected base material.

In contrast, the material deposited on the 7075 substrate exhibited an average hardness of 101 HV, rising to about 120 HV in the HAZ and 130 HV in the unaffected base material. These tendencies observed from the track centre to the edges are mainly influenced by the thermal gradient generated during solidification.

Notably, extensive research has been conducted on the toughness of welds in 2xxx series aluminium alloys. According to Jin et al. [

32], hardness values for welded joints of the 2319 series alloys ranged from 80 to 120 HV

0.1, emphasising the need for the careful control of the welding process to achieve the desired mechanical performance.

4. Conclusions

This study presents an innovative powder metallurgy approach for manufacturing wires suitable for additive manufacturing with the 2060 alloy. These wires demonstrate compatibility with plasma welding techniques, thereby opening up potential applications in welding high-strength aluminium alloys. The research expands the possibilities for using the 2060 alloy and creates new avenues in high-strength aluminium alloy welding.

Overall, the results indicate that the deposition of PM wires onto two different substrates, AA7075 and AA5083, is feasible using the PMD welding process since the wires were well deposited on both substrates. While porosity remains a concern, no cracking was observed. To further enhance the quality of the deposited material, process parameters should be specifically optimised for Al-Cu-Li alloys, since, due to the limited availability of these alloys, the parameters employed here were those previously optimised for Al-Cu commercial wires. Such optimisation could help mitigate porosity and improve the overall microstructural and mechanical integrity of the deposits.

AA2060 welds with the 5083 substrate appear to exhibit a more uniform microstructure, as confirmed by SEM analysis. However, for the 7075 substrate, the deposited material penetrates further due to higher thermal conductivity. EDX analysis confirms the presence of Al-Cu and Al-Cu-Mg compounds after the welding process.

While few studies have reported on chemical element losses during welding, which are highly relevant for alloys susceptible to elemental evaporation, this work presents quantitative composition measurements. Through ICP-OES analysis, significant losses of 55% in Li and 25% in Cu were identified, consistent with expectations post-welding. Finally, hardness measurements revealed that the 7075 substrate exhibited a higher hardness than the 5083 alloy. Furthermore, SEM images revealed notable variations in the heat-affected zone (HAZ), which was higher for the 7075 substrate. The enhanced hardness in this region is influenced by two factors: both the 2060 and 7075 alloys are heat-treatable, and this region is enriched with alloying elements such as Mg and Zn, as indicated by ICP-OES analysis. In contrast, the mechanical properties of the 5083 substrate exhibit more stability.

Despite these promising initial findings, the study revealed the presence of porosity and areas with a lack of fusion in both substrates, with more pronounced defects observed in the 7075 substrate. Future research should focus on improving wire production, for instance, by optimising the chemical composition through the addition of small amounts of Ti, Zr, or Sc [

33] to enhance grain refinement and promote finer microstructures during solidification. Furthermore, adapting the flexibility of the PM wire manufacturing route to the specific requirements of the PMD could contribute to improved deposition quality and overall performance.