Extruded Food Pellets with the Addition of Lucerne Sprouts: Selected Physical and Chemical Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Mixtures and Extrusion-Cooking Process

2.3. Efficiency of the Extrusion-Cooking Process

2.4. Energy Consumption of the Extrusion-Cooking Process

2.5. Bulk Density of Snack Pellets

2.6. Durability of Extrudates

2.7. Water Absorption Index of Snack Pellets

2.8. The Water Solubility Index of Snack Pellets

2.9. Preparation of Extracts

2.10. Free Radical Scavenging Activity—DPPH Assay

2.11. Determination of Total Polyphenolic Content (TPC)—Folin–Ciocalteu Method

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Results of Extrusion-Cooking Efficiency and Energy Consumption

3.2. Impact of Ingredients and Processing Conditions on Selected Physical Properties

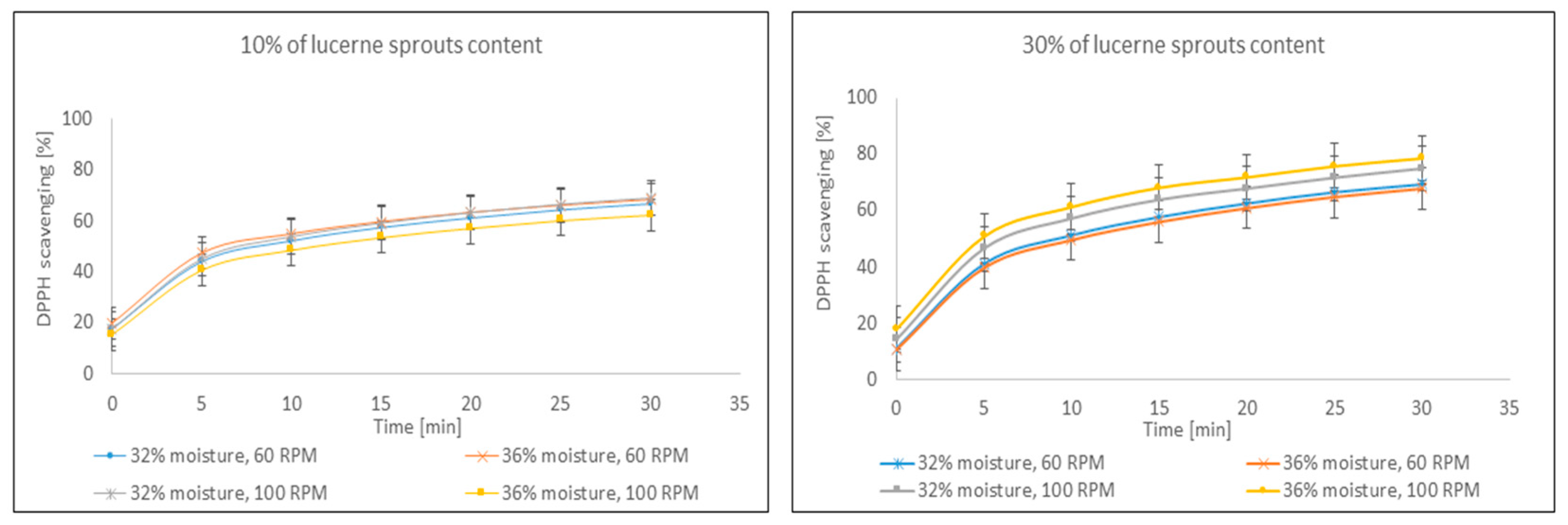

3.3. DPPH Scavenging and Total Phenolic Content (TPC)-Folin–Ciocalteu Method

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baker, M.T.; Lu, P.; Parrella, J.A.; Leggette, H.R. Consumer Acceptance toward Functional Foods: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigliardi, B.; Galati, F. Innovation trends in the food industry: The case of functional foods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 31, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidinejad, A. The road ahead for functional foods: Promising opportunities amidst industry challenges. Future Postharv. Food 2024, 1, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalwan, T.A. Consumer Psychology in Functional Beverages: From Nutritional Awareness to Habit Formation. Beverages 2025, 11, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurek, M.; Benaida-Debbache, N.; Elez Garofulić, I.; Galić, K.; Avallone, S.; Voilley, A.; Waché, Y. Antioxidants and Bioactive Compounds in Food: Critical Review of Issues and Prospects. Antioxidant 2022, 11, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekete, M.; Lehoczki, A.; Kryczyk-Poprawa, A.; Zábó, V.; Varga, J.T.; Bálint, M.; Fazekas-Pongor, V.; Csípő, T.; Rząsa-Duran, E.; Varga, P. Functional Foods in Modern Nutrition Science: Mechanisms, Evidence, and Public Health Implications. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puri, S.; Shaheen, M.; Grover, B. Nutrition and cognitive health: A life course approach. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1023907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazzaro, C.; Uliano, A.; Lerro, M.; Stanco, M. From Claims to Choices: How Health Information Shapes Consumer Decisions in the Functional Food Market. Foods 2025, 14, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, P.; Teixeira, M. Healthy eating as a trend: Consumers’ perceptions towards products with nutrition and health claims. Rev. Bras. Gest. Neg. 2021, 23, 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Zhong, M.; Huang, X.; Hussain, Z.; Ren, M.; Xie, X. Industrial Production of Functional Foods for Human Health and Sustainability. Foods 2024, 13, 3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Jia, F.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, J.; Zheng, T.; Zheng, H.; Yang, Y. The Impact of Extrusion Cooking on the Physical Properties, Functional Components, and Pharmacological Activities of Natural Medicinal and Edible Plants: A Review. Foods 2025, 14, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mironeasa, S.; Coţovanu, I.; Mironeasa, C.; Ungureanu-Iuga, M. A Review of the Changes Produced by Extrusion Cooking on the Bioactive Compounds from Vegetal Sources. Antioxidant 2023, 12, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sule, S.; Okafor, G.I.; Momoh, O.C.; Gbaa, S.T.; Amonyeze, A.O. Applications of food extrusion technology. MOJ Food Process Technols. 2024, 12, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pismag, R.Y.; Polo, M.P.; Hoyos, J.L.; Bravo, J.E.; Roa, D.F. Effect of extrusion cooking on the chemical and nutritional properties of instant flours: A review. F1000Research 2024, 12, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N.; Suvedi, D.; Sharma, A.; Khanal, S.; Verma, R.; Kumar, D.; Khan, Z.; Peter, L. Extrusion technology in food processing: Principles, innovations and applications in sustainable product development. Food Humanit. 2025, 5, 100672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Gamlath, S.; Wakeling, L. Nutritional aspects of food extrusion: A review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 42, 916–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisiecka, K.; Wójtowicz, A. Possibility to Save Water and Energy by Application of Fresh Vegetables to Produce Supplemented Potato-Based Snack Pellets. Processes 2020, 8, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esen, B.O.; Bozdogan, N.; Kutlar, L.M.; Kumcuoglu, S. Development of Gluten-Free Extruded Snack Containing Lentil Flour and Evaluation of Extrusion Process Conditions on Quality Properties. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tas, A.A.; Shah, A.U. The replacement of cereals by legumes in extruded snack foods: Science, technology and challenges. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 116, 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqualone, A.; Costantini, M.; Coldea, T.E.; Summo, C. Use of Legumes in Extrusion Cooking: A Review. Foods 2020, 9, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faliarizao, N.; Berrios, J.D.J.; Dolan, K.D. Value-Added Processing of Food Legumes Using Extrusion Technology: A Review. Legume Sci. 2024, 6, e231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waliat, S.; Arshad, M.S.; Hanif, H.; Ejaz, A.; Khalid, W.; Kauser, S.; Al-Farga, A. A review on bioactive compounds in sprouts: Extraction techniques, food application and health functionality. Int. J. Food Prop. 2023, 26, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloo, S.O.; Ofosu, F.K.; Kilonzi, S.M.; Shabbir, U.; Oh, D.H. Edible Plant Sprouts: Health Benefits, Trends, and Opportunities for Novel Exploration. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motrescu, I.; Lungoci, C.; Calistru, A.E.; Luchian, C.E.; Gocan, T.M.; Rimbu, C.M.; Bulgariu, E.; Ciolan, M.A.; Jitareanu, G. Non-Thermal Plasma (NTP) Treatment of Alfalfa Seeds in Different Voltage Conditions Leads to Both Positive and Inhibitory Outcomes Related to Sprout Growth and Nutraceutical Properties. Plants 2024, 13, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Peng, Y.; Wang, M.; Li, W.; Li, Y.; Chen, J. Effect of Red and Blue Light on the Growth and Antioxidant Activity of Alfalfa Sprouts. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igual, M.; Chiş, M.S.; Socaci, S.A.; Vodnar, D.C.; Ranga, F.; Martínez-Monzó, J.; García-Segovia, P. Effect of Medicago sativa Addition on Physicochemical, Nutritional and Functional Characteristics of Corn Extrudates. Foods 2021, 10, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soja, J.; Combrzyński, M.; Oniszczuk, T.; Gancarz, M.; Oniszczuk, A. Extrusion-Cooking Aspects and Physical Characteristics of Snack Pellets with Addition of Selected Plant Pomace. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrus, M.; Combrzyński, M.; Biernacka, B.; Wójtowicz, A.; Milanowski, M.; Kupryaniuk, K.; Gancarz, M.; Soja, J.; Różyło, R. Fresh Broccoli in Fortified Snack Pellets: Extrusion-Cooking Aspects and Physical Characteristics. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójtowicz, A.; Combrzyński, M.; Biernacka, B.; Oniszczuk, T.; Mitrus, M.; Różyło, R.; Gancarz, M.; Oniszczuk, A. Application of Edible Insect Flour as a Novel Ingredient in Fortified Snack Pellets: Processing Aspects and Physical Characteristics. Processes 2023, 11, 2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisiecka, K.; Wójtowicz, A.; Mitrus, M.; Oniszczuk, T.; Combrzyński, M. New type of potato-based snack-pellets supplemented with fresh vegetables from the Allium genus and its selected properties. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 145, 111233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burda, S.; Oleszek, W. Antioxidant and antiradical activities of flavonoids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 2774–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combrzyński, M.; Soja, J.; Oniszczuk, T.; Wojtunik-Kulesza, K.; Kręcisz, M.; Mołdoch, J.; Biernacka, B. The Impact of Fresh Blueberry Addition on the Extrusion-Cooking Process, Physical Properties and Antioxidant Potential of Potato-Based Snack Pellets. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantrong, H.; Charunuch, C.; Limsangouan, N.; Pengpinit, W. Influence of process parameters on physical properties and specific mechanical energy of healthy mushroom-rice snacks and optimization of extrusion process parameters using response surface methodology. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 3462–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Guerrero, M.; Nickerson, M.T.; Koksel, F. Effects of extrusion screw speed, feed moisture content, and barrel temperature on the physical, techno-functional, and microstructural quality of texturized lentil protein. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 2040–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisiecka, K.; Wójtowicz, A. Effect of fresh beetroot application and processing conditions on some quality features of a new type of potato-based snacks. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 141, 110919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dushkova, M.; Simitchiev, A.; Petrova, T.; Menkov, N.; Desseva, I.; Mihaylova, D. Physical and Functional Characteristics of Extrudates Prepared from Quinoa Enriched with Goji Berry. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drożdż, W.; Boruczkowska, H.; Boruczkowski, T.; Tomaszewska-Ciosk, E.; Zdybel, E. Use of blackcurrant and chokeberry press residue in snack products. Pol. J. Chem. Technol. 2019, 21, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, C.; Wang, L.; Li, D.; Özkan, N.; Chen, X.D.; Mao, Z. Influence of Alfalfa Powder Concentration and Granularity on Rheological Properties of Alfalfa–Wheat Dough. J. Food Eng. 2008, 86, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellebois, T.; Soukoulis, C.; Van der Meeren, P.; Deriemaeker, L.; Delcour, J.A.; Courtin, C.M.; Van Craeyveld, V. Structure, Conformational and Rheological Characterisation of Alfalfa Seed (Medicago sativa L.) Galactomannan. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 253, 117394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellebois, T.; Soukoulis, C.; Van der Meeren, P.; Deriemaeker, L.; Delcour, J.A.; Courtin, C.M.; Van Craeyveld, V. Impact of Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) Galactomannan on the Microstructural and Physicochemical Changes of Milk Proteins under Static In-Vitro Digestion Conditions. Food Chem. X 2022, 14, 100330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumilaar, S.G.; Hardianto, A.; Dohi, H.; Kurnia, D. A Comprehensive Review of Free Radicals, Oxidative Stress, and Antioxidants: Overview, Clinical Applications, Global Perspectives, Future Directions, and Mechanisms of Antioxidant Activity of Flavonoid Compounds. J. Chem. 2024, 5594386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.H.; Wang, J.; Guo, R.; Wang, C.Z.; Yan, X.B.; Xu, B.; Zhang, D.Q. Effects of alfalfa saponin extract on growth performance and some antioxidant indices of weaned piglets. Livest. Sci. 2014, 167, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Thayer, D.W.; Sokorai, K.J. Changes in growth and antioxidant status of alfalfa sprouts during sprouting as affected by gamma irradiation of seeds. J. Food Prot. 2004, 67, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zujko, M.E.; Terlikowska, K.M.; Zujko, K.; Paruk, A.; Witkowska, A.M. Sprouts as potential sources of dietary antioxidants in human nutrition. Prog. Health Sci. 2016, 6, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.R.; Pereira, M.J.; Azevedo, J.; Gonçalves, R.F.; Valentão, P.; Guedes de Pinho, P.; Andrade, P.B. Glycine max (L.) Merr., Vigna radiata L. and Medicago sativa L. sprouts: A natural source of bioactive compounds. Food Res. Int. 2013, 50, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Păușan, D.-E.; Man, S.; Chiş, S.-M.; Pop, A.; Muste, S.; Păucean, A. Alfalfa Seeds and Sprouts–Review of the Health Benefits and Their Influence on Bakery Products. Hop. Med. Plants 2022, 30, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloo, S.O.; Kaliyan Barathikannan, K.; Ofosu, F.K.; Oh, D.-H. Fermentation of ascorbic acid-elicited alfalfa sprouts further enhances their metabolite profile, antioxidant, and anti-obesity effects. Food Biosci. 2023, 54, 102871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamovich, T.; Olkova, A. The content of biologically active substances in seeds and sprouts of beans of the papilionoideae subfamily. Sib. J. Life Sci. Agric. 2024, 16, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lucerne Sprouts Addition [%] | Screw Rotation [rpm] | Moisture [%] | Q [kg/h] | SME [kWh/kg] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flat forming die | 0 | 60 | 32 | 19.66 ± 0.63 b | 0.044 ± 0.010 ab |

| 36 | 14.97 ± 0.80 a | 0.097 ± 0.021 bcde | |||

| 100 | 32 | 32.30 ± 3.62 d | 0.044 ± 0.005 ab | ||

| 36 | 25.39 ± 1.93 c | 0.066 ± 0.019 abcd | |||

| 10 | 60 | 32 | 19.76 ± 0.14 b | 0.038 ± 0.003 a | |

| 36 | 11.04 ± 0.42 a | 0.228 ± 0.033 f | |||

| 100 | 32 | 32.00 ± 0.55 d | 0.032 ± 0.003 a | ||

| 36 | 20.96 ± 1.32 b | 0.078 ± 0.014 abcde | |||

| 30 | 60 | 32 | 14.32 ± 0.14 a | 0.103 ± 0.025 cde | |

| 36 | 11.76 ± 0.24 a | 0.134 ± 0.028 e | |||

| 100 | 32 | 23.52 ± 1.27 bc | 0.064 ± 0.012 abc | ||

| 36 | 12.80 ± 0.73 a | 0.121 ± 0.027 de | |||

| Ring shape die | 0 | 60 | 32 | 18.80 ± 0.60 de | 0.045 ± 0.010 a |

| 36 | 14.32 ± 0.77 bc | 0.098 ± 0.021 abc | |||

| 100 | 32 | 30.88 ± 3.48 i | 0.045 ± 0.005 a | ||

| 36 | 24.32 ± 1.74 gh | 0.066 ± 0.019 abc | |||

| 10 | 60 | 32 | 16.08 ± 0.72 cd | 0.085 ± 0.022 abc | |

| 36 | 14.64 ± 0.63 bc | 0.103 ± 0.017 bcd | |||

| 100 | 32 | 28.08 ± 2.20 hi | 0.047 ± 0.007 ab | ||

| 36 | 20.16 ± 0.48 ef | 0.078 ± 0.024 abc | |||

| 30 | 60 | 32 | 11.04 ± 0.24 ab | 0.159 ± 0.035 d | |

| 36 | 9.68 ± 0.14 a | 0.222 ± 0.028 e | |||

| 100 | 32 | 23.44 ± 0.28 fg | 0.061 ± 0.012 abc | ||

| 36 | 18.80 ± 0.50 de | 0.111 ± 0.009 cd |

| Lucerne Sprouts Addition [%] | Screw Rotation [rpm] | Moisture [%] | WAI [g/g] | WSI [%] | BD [kg/m3] | D [%] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flat forming die | 0 | 60 | 32 | 3.65 ± 0.15 cd | 6.26 ± 0.259 a | 351.65 ± 8.48 de | 97.50 ± 0.30 c |

| 36 | 4.37 ± 0.17 ef | 15.14 ± 0.143 g | 340.55 ± 10.07 cd | 97.43 ± 0.42 c | |||

| 100 | 32 | 3.98 ± 0.18 de | 7.27 ± 0.165 b | 399.03 ± 11.82 f | 97.67 ± 0.31 c | ||

| 36 | 4.45 ± 0.15 f | 18.21 ± 0.208 h | 372.11 ± 11.69 ef | 97.53 ± 0.47 c | |||

| 10 | 60 | 32 | 2.71 ± 0.11 a | 9.61 ± 0.205 c | 365.02 ± 8.41 de | 94.93 ± 0.31 b | |

| 36 | 3.87 ± 0.17 d | 9.84 ± 0.143 c | 359.55 ± 8.91 de | 95.33 ± 0.45 b | |||

| 100 | 32 | 2.86 ± 0.16 ab | 11.56 ± 0.155 e | 361.67 ± 11.11 de | 95.10 ± 0.40 b | ||

| 36 | 3.78 ± 0.18 d | 10.43 ± 0.229 d | 342.20 ± 3.39 cde | 94.90 ± 0.46 b | |||

| 30 | 60 | 32 | 3.14 ± 0.14 ab | 9.83 ± 0.129 c | 314.95 ± 16.48 bc | 88.97 ± 0.25 a | |

| 36 | 3.82 ± 0.17 d | 13.90 ± 0.201 f | 296.44 ± 14.47 ab | 88.93 ± 0.45 a | |||

| 100 | 32 | 3.25 ± 0.15 bc | 10.84 ± 0.142 d | 337.02 ± 9.51 cd | 89.07 ± 0.25 a | ||

| 36 | 3.65 ± 0.15 cd | 9.40 ± 0.152 c | 272.54 ± 0.92 a | 88.83 ± 0.21 a | |||

| Ring shape die | 0 | 60 | 32 | 2.20 ± 0.15 a | 6.27 ± 0.168 c | 247.46 ± 3.56 a | 97.30 ± 0.30 c |

| 36 | 2.39 ± 0.14 a | 7.40 ± 0.197 d | 249.23 ± 5.27 a | 97.23 ± 0.42 c | |||

| 100 | 32 | 2.38 ± 0.18 a | 8.53 ± 0.235 e | 253.71 ± 3.21 a | 97.47 ± 0.31 c | ||

| 36 | 2.29 ± 0.19 a | 9.27 ± 0.172 f | 261.47 ± 1.77 a | 97.33 ± 0.47 c | |||

| 10 | 60 | 32 | 2.60 ± 0.15 ab | 9.54 ± 0.144 f | 394.67 ± 3.21 b | 94.63 ± 0.31 b | |

| 36 | 3.32 ± 0.17 cd | 10.40 ± 0.199 g | 454.00 ± 7.21 d | 95.03 ± 0.45 b | |||

| 100 | 32 | 3.06 ± 0.16 bc | 10.13 ± 0.178 g | 418.67 ± 3.21 c | 94.80 ± 0.40 b | ||

| 36 | 3.59 ± 0.14 de | 7.13 ± 0.183 d | 484.00 ± 7.00 ef | 94.60 ± 0.46 b | |||

| 30 | 60 | 32 | 3.74 ± 0.14 de | 4.69 ± 0.144 b | 475.67 ± 3.06 e | 88.57 ± 0.25 a | |

| 36 | 3.97 ± 0.17 e | 4.83 ± 0.130 b | 540.33 ± 1.15 g | 88.53 ± 0.45 a | |||

| 100 | 32 | 3.46 ± 0.16 cd | 4.82 ± 0.143 b | 495.00 ± 8.89 f | 88.67 ± 0.25 a | ||

| 36 | 3.64 ± 0.14 de | 3.67 ± 0.172 a | 567.00 ± 5.57 h | 88.43 ± 0.21 a |

| Lucerne Sprouts Content | Production Parameters | Total Phenolic Content [μg GAE/g Dry Weight] |

|---|---|---|

| 10% | 32% moisture, 60 RPM | 72.7 ± 2.14 d |

| 10% | 36% moisture, 60 RPM | 75.4 ± 0.47 d |

| 10% | 32% moisture, 100 RPM | 83.6 ± 0.56 e |

| 10% | 36% moisture, 100 RPM | 98.4 ± 3.33 f |

| 30% | 32% moisture, 60 RPM | 131.9 ± 1.76 g |

| 30% | 36% moisture, 60 RPM | 66.0 ± 1.50 c |

| 30% | 32% moisture, 100 RPM | 75.5 ± 1.50 d |

| 30% | 36% moisture, 100 RPM | 102.5 ± 2.67 f |

| 0% | 32% moisture, 60 RPM | 58.0 ± 0.98 b |

| 0% | 36% moisture, 60 RPM | 59.3 ± 1.00 b |

| 0% | 32% moisture, 100 RPM | 60.6 ± 0.65 bc |

| 0% | 36% moisture, 100 RPM | 50.0 ± 0.97 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Biernacka, B.; Soja, J.; Wojtunik-Kulesza, K.; Gancarz, M.; Stasiak, M.; Kręcisz, M.; Combrzyński, M. Extruded Food Pellets with the Addition of Lucerne Sprouts: Selected Physical and Chemical Properties. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12390. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312390

Biernacka B, Soja J, Wojtunik-Kulesza K, Gancarz M, Stasiak M, Kręcisz M, Combrzyński M. Extruded Food Pellets with the Addition of Lucerne Sprouts: Selected Physical and Chemical Properties. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12390. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312390

Chicago/Turabian StyleBiernacka, Beata, Jakub Soja, Karolina Wojtunik-Kulesza, Marek Gancarz, Mateusz Stasiak, Magdalena Kręcisz, and Maciej Combrzyński. 2025. "Extruded Food Pellets with the Addition of Lucerne Sprouts: Selected Physical and Chemical Properties" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12390. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312390

APA StyleBiernacka, B., Soja, J., Wojtunik-Kulesza, K., Gancarz, M., Stasiak, M., Kręcisz, M., & Combrzyński, M. (2025). Extruded Food Pellets with the Addition of Lucerne Sprouts: Selected Physical and Chemical Properties. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12390. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312390