1. Introduction

Designing efficient mixes of various renewable energy sources is becoming one of the key challenges of today’s energy transition [

1]. Integrating solar, wind, hydro, and biomass energy allows for their variable characteristics to complement each other, leading to more stable and predictable energy production [

2]. This is no longer just a political or ecological vision, but above all, an economically rational strategy for ensuring affordable and independent energy in the long term [

3]. The decreasing costs of PV and wind turbine technologies make the construction of a diverse renewable energy mix a viable alternative to traditional fossil fuel-based sources. Combining various renewable technologies minimizes the risk of energy shortages during periods of unfavorable weather conditions, thus increasing the energy security of countries and regions [

4]. Efficient mixing of renewable sources also enables better utilization of local natural resources, adapting the system structure to the specific climatic and geographic conditions of a given area. This approach optimizes investment and operating costs, especially with the growing importance of energy storage and smart grids [

5]. In the long term, developing renewable energy mixes is a path to achieving near-zero marginal costs of energy production, making it the cheapest source of energy for the economy [

6]. Unlike fossil fuels, wind and solar energy are virtually inexhaustible, giving them strategic importance for future generations. Therefore, designing sustainable and efficient renewable energy mixes is becoming not only a technical challenge but also a cornerstone of modern economic and climate policy [

7].

China has implemented one of the world’s largest renewable energy projects, building massive photovoltaic and wind farms in the Gobi Desert [

8]. This investment was part of the country’s long-term energy transition strategy, which aims to reduce dependence on coal and reduce CO

2 emissions [

9]. The project required overcoming numerous technical and environmental challenges, including extreme temperatures, frequent sandstorms, and limited access to transmission infrastructure [

10]. Engineers had to develop special dust- and wind-resistant panel designs, as well as cleaning systems for the modules, to maintain their high efficiency in the harsh desert conditions. Modern high-voltage transmission lines were also constructed, transporting energy from remote desert areas to industrial and urban centers. This investment has significantly increased China’s installed renewable energy capacity, improved energy security, and reduced greenhouse gas emissions. An additional benefit is the development of local economies in desert regions, creating thousands of jobs and modern infrastructure [

11]. The Gobi Desert project has become a symbol of China’s determination to build a low-carbon future and an example of how scale, planning, and technology can work together to transform wasteland into a strategic source of clean energy.

Europe is also consistently developing energy infrastructure based on diversified renewable energy sources, striving to achieve climate neutrality by 2050 [

12]. According to Eurostat data, the share of renewable energy in the European Union’s gross final energy consumption increased from 21.8% in 2021 to approximately 26% in 2024, and forecasts for 2030 assume it will exceed 42.5% [

13]. Poland is also seeing a significant increase in the share of renewable energy, which reached approximately 22% in 2023, compared to less than 12% in 2015. Installed capacity in domestic photovoltaics reached over 17 GW at the beginning of 2025, representing an increase of over 300% in four years, and in wind energy exceeded 10 GW [

14]. As a result, renewable sources now account for nearly one-third of Poland’s electricity production, and their share is growing monthly. Transmission grids and energy storage facilities are also being dynamically developed across Europe, enabling better balancing of variable wind and solar generation. This development confirms that renewable energy sources are becoming not only a pillar of climate policy but also a real foundation for a modern, secure, and competitive energy economy [

15].

Despite dynamic technological development and falling unit costs, investing in renewable energy sources (RESs) still faces significant economic, legal, and infrastructural challenges [

16]. One of the biggest barriers to entry into RES projects is the very high initial investment cost, which requires significant capital or access to favorable loans. For a wind farm with a maximum capacity of 3.45 MW, the total construction cost, including the turbine, foundation, electrical installation, grid connection, and design costs, currently ranges from EUR 4.5 to EUR 5.5 million, which equates to approximately EUR 1.3–1.6 million/MW [

17]. By comparison, a photovoltaic system with the same peak power of 3.45 MWp costs EUR 2.5–3.0 million, or approximately 0.75–0.9 million EUR/MWp, depending on the type of modules, inverters, and support structures [

18]. Additional difficulties include lengthy administrative procedures, the need to obtain environmental permits, and the limited availability of suitable land for connection to the electricity grid [

19].

Assuming that a renewable energy installation operates an average of 2800 h per year (for wind) or 1200 h per year (for PV) and energy is sold at a price of 0.30 EUR/kWh, annual revenues could reach approximately EUR 2.9 million for a wind turbine and EUR 1.2 million for a 3.45 MW photovoltaic farm, respectively. After taking into account operating and maintenance costs, which constitute approximately 2–3% of the investment value annually, the approximate payback time is 5 to 7 years for a wind turbine and 6 to 8 years for a photovoltaic system [

20]. This means that despite the high financial barrier at the entry stage, such investments remain very profitable in the long term, especially in the context of rising energy prices and EU policy support for the green transformation [

21].

Balancing a power grid based on photovoltaic and wind sources is one of the greatest challenges facing the modern energy sector [

22]. Energy production from these sources is unstable and dependent on weather conditions, making it difficult to maintain a real-time balance between supply and demand. During periods of high renewable generation, there is a risk of grid overload, while during periods of low production, rapid activation of backup sources is necessary [

23]. A key element in solving this problem is the development of modern energy storage systems, which allow for the storage of surplus energy and its use during periods of shortage [

24]. Battery technologies, including lithium-ion and flow batteries, are becoming increasingly efficient and less expensive, making them a real support for grid stabilization. In recent years, the cost of energy storage systems has fallen by over 80% compared to 2010, significantly increasing their investment attractiveness. Advanced energy management systems (EMSs), which analyze production and demand data in real time, optimizing energy flows within the grid, are also gaining importance [

25]. Such systems utilize artificial intelligence and predictive algorithms, enabling more precise power balancing under dynamically changing load conditions. Scientists play a crucial role in the development of these technologies, developing new methods for storing, controlling, and forecasting renewable energy production [

26]. Their research enables the creation of increasingly sustainable and intelligent energy systems, which in the future will be able to fully integrate intermittent renewable sources into national and European transmission grids [

27].

Modern energy grid balancing increasingly relies on advanced scientific methods utilizing artificial intelligence, data analysis, and predictive modeling. One of the most important developments is machine learning algorithms, which allow for the prediction of short- and long-term energy production from photovoltaics and wind based on meteorological and historical data. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) [

28] and GRU neural networks [

29] are becoming increasingly common, excelling at time series analysis and enabling precise forecasts of renewable energy generation in variable weather conditions. Another rapidly developing area is the use of particle swarm optimization (PSO) [

30] and genetic algorithms for power flow control and energy storage scheduling. These methods are particularly useful in the optimal management of distributed energy sources, where traditional control techniques prove insufficient. Digital twins are also gaining in importance, enabling the simulation and testing of various power system operation scenarios without the risk of disruptions in the real grid [

31,

32]. Research also employs methods based on fuzzy set theory and fuzzy logic, which enable decision-making under conditions of uncertainty inherent in variable renewable energy production. Modern balancing systems increasingly utilize hybrid models combining artificial intelligence with classical optimization methods, such as linear or dynamic programming [

33]. Reinforcement learning algorithms, which learn to adaptively respond to grid changes and optimize energy flows in real time, also offer significant potential [

34]. The common goal of all these methods is to increase the stability and efficiency of power systems, where intermittent renewable sources play an increasingly important role.

Previous research on the complementarity of photovoltaic and wind sources has focused primarily on classical statistical methods, such as the correlation coefficient, variability index, and source interoperability indices [

35]. While these methods provide some information on the degree of interdependence between power profiles, they do not account for time shifts or nonlinear changes characteristic of actual measurement data. Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) represents an innovative approach in this context, as it enables matching energy profiles with different temporal dynamics and captures similarities that are not visible in classical analysis [

36]. To date, DTW has been used primarily in fields such as pattern recognition, speech analysis, hydrology, and energy load forecasting, and in the area of renewable energy sources, primarily for the analysis of individual PV or wind profiles [

37]. Applying this method to comprehensively assess the power generated by a photovoltaic–wind mix is a relatively new approach and is rarely encountered in the scientific literature. Few studies address the use of DTW in the context of assessing spatial or locational complementarity of sources, but they do not analyze actual production data from the perspective of energy balancing over time [

38]. Using DTW to study the synchronization of PV and wind profiles enables a much more precise assessment of their interaction over short and long time periods. This approach allows for the identification of periods of highest generation compatibility, as well as moments of greatest production differences, which is crucial for effective energy mix planning. This opens a new direction of research on the integration of real-world data, time analysis methods, and artificial intelligence tools in the renewable energy sector. Consequently, the use of DTW for the analysis of hybrid PV–wind systems can be considered an innovative and promising contribution to the development of scientific methodology for optimizing the operation of sustainable energy systems.

Despite numerous studies on the correlation and variability of renewable sources, the temporal structure of PV–wind interactions remains insufficiently explored. Most previous works have relied on linear methods, which cannot capture nonlinear phase shifts and complex time-dependent similarities between energy generation profiles. This study addresses this gap by applying the Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) algorithm to real PV and wind measurement data from the Lublin Voivodeship in Poland. The proposed approach enables nonlinear time alignment and quantification of complementarity under realistic operating conditions, providing a more precise representation of the temporal dynamics within hybrid renewable systems. This novelty allows for the identification of hidden synchronization patterns and supports improved planning of hybrid PV–wind configurations.

The aim of this study is to assess the degree of time consistency and complementarity of power generated by a hybrid system consisting of photovoltaic and wind installations using the Dynamic Time Warping algorithm. The analysis aims to identify periods of maximum and minimum synchronization of energy production and to determine the extent to which DTW allows for a more accurate representation of the actual dependencies between renewable energy sources than conventional methods. The ultimate goal is to develop a methodology that enables more precise planning of photovoltaic and wind mixes and supports the balancing of power grids with a high share of intermittent renewable energy sources.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was conducted using real-world measurement data from renewable energy systems located in the Lublin Voivodeship in Poland. This region boasts some of the best solar radiation in the country and favorable wind potential, making it a particularly representative area for analyzing PV–wind hybrid mixes. Data were recorded from two parallel measurement systems: one for photovoltaics and one for wind, operating continuously from 1 April to 31 May 2024. Photovoltaic power was measured every 15 min, while wind power was recorded every 10 min. Both data sets include complete time series without significant measurement gaps, enabling accurate reproduction of the actual energy generation dynamics during the study period.

The measurement data underwent preprocessing, including outlier removal, interpolation of short-period gaps, and time synchronization of series with different sampling rates. For this purpose, resampling was performed to the least common multiple of the time intervals, i.e., to a 30 min time step, ensuring consistency between both series and enabling direct comparison. Synchronized time series of instantaneous power generated by the photovoltaic installation and the wind turbine were then created, and their combined power waveforms in the hybrid mix were calculated.

A comparative analysis of energy production dynamics was performed using the Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) algorithm, which enables nonlinear fitting of two time series with different waveforms and phase shifts. A classic variant of the DTW method, with a Euclidean metric and min–max normalization, was used, allowing for a comparison of the waveforms of both signals regardless of their power scale. Calculations were performed for the full monthly series in 30 min time steps, and the resulting DTW distance value was interpreted as a measure of the mutual complementarity of sources over time. Smaller DTW values indicated greater similarity and a higher degree of complementarity between sources, while higher values indicated greater substitutability between them.

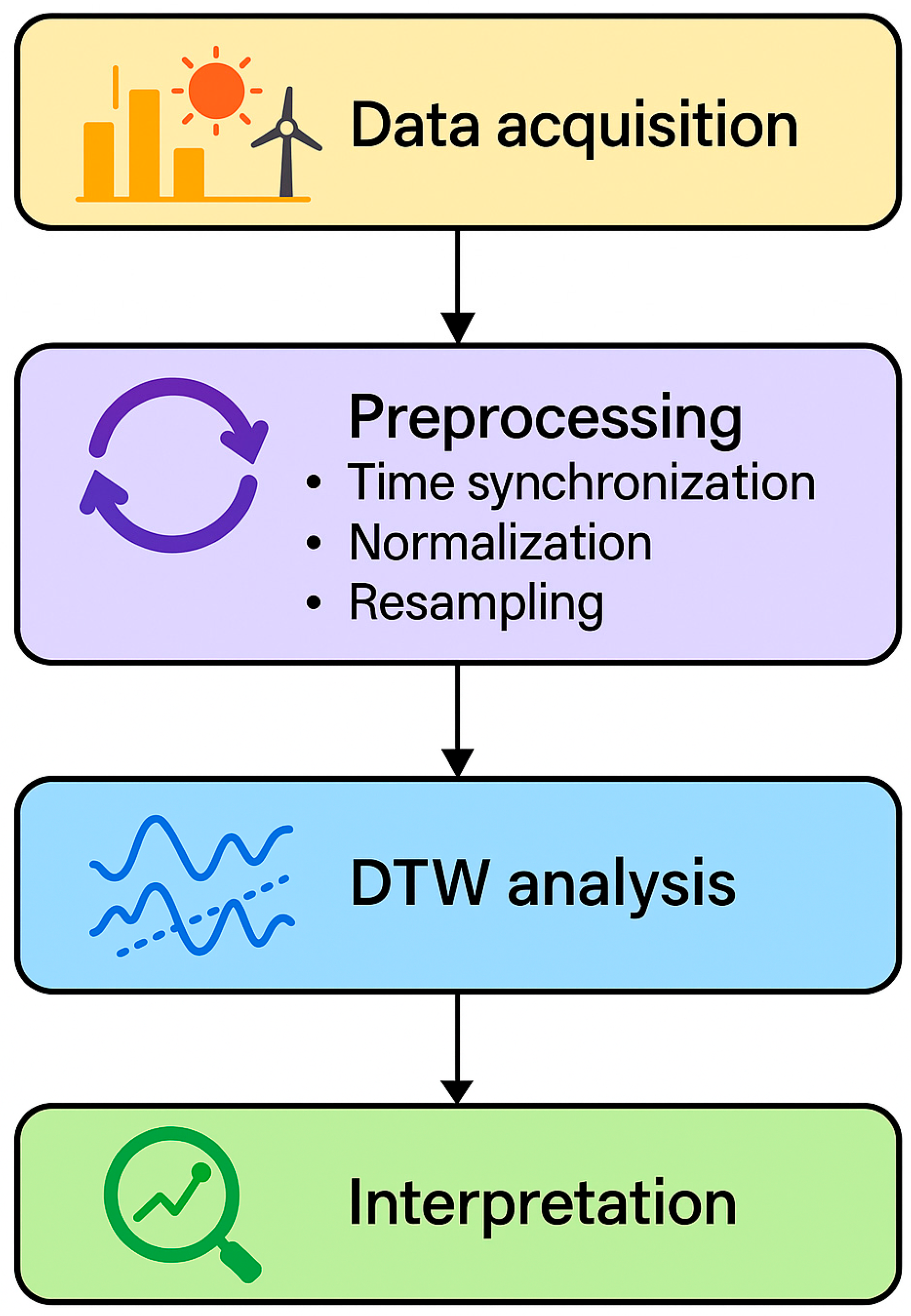

The methodological framework of the study is presented in

Figure 1 and consists of four main stages: (1) data acquisition from photovoltaic and wind installations, (2) preprocessing and time synchronization, (3) Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) computation, and (4) interpretation of temporal complementarity.

The DTW algorithm was implemented using the classical dynamic programming formulation. For two discrete time series,

A = (

a1,

a2,

…,

an) and

B = (

b1,

b2,

…,

bm), the local distance matrix d(i,j) = |

ai −

bj| was computed using the Euclidean metric. The optimal warping path

W = (

w1,

w2,

…,

wk) minimizing the cumulative cost

D(

A,

B) was determined recursively as:

The preprocessing stage included outlier removal, interpolation, and resampling to a common 30 min step (least common multiple of original sampling intervals: 10 and 15 min). The min–max normalization ensured that both signals shared a common amplitude scale (0–1), allowing for shape-based rather than magnitude-based comparison.

All calculations and visualizations were performed in Python 3.11 using the pandas, numpy, matplotlib, and scipy libraries, ensuring high precision of numerical calculations and reproducibility of results. The resulting time series, graphs, and DTW distance matrices formed the basis for further comparative analysis and interpretation of the complementarity of renewable sources on a monthly basis.

3. Results

This chapter will perform all calculation steps planned in the research experiment, first for measurement data from April 2024, and then for measurement data from May 2024. As an introduction to the analysis, it is worth emphasizing that April in the Lublin region (Poland) is characterized by average solar radiation but high wind speeds. May is characterized by high solar radiation and average wind conditions. According to the authors, the power series generated in these months by a photovoltaic system with a peak power of 3.45 MW and a wind turbine with a maximum power of 3.45 MW constitute a very interesting energy mix composition for various studies and analyses.

3.1. Analysis of Data from April (High Wind and Low Solar Radiation)

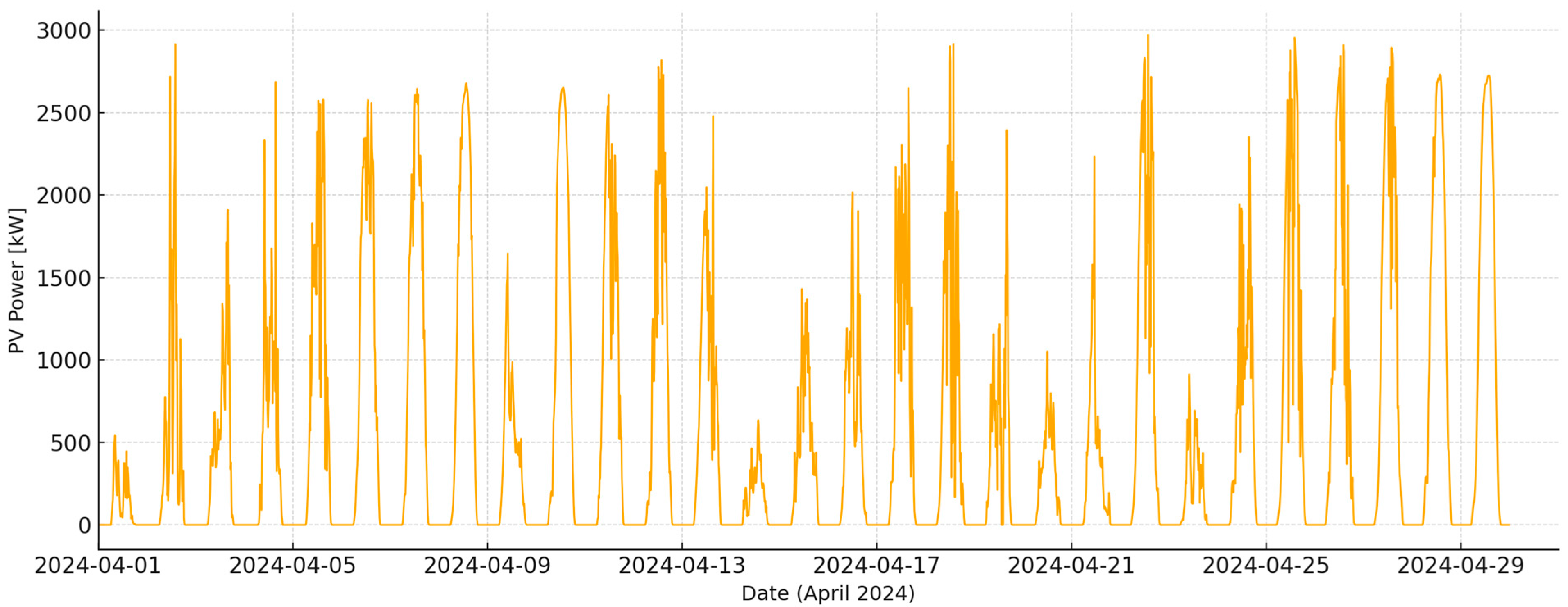

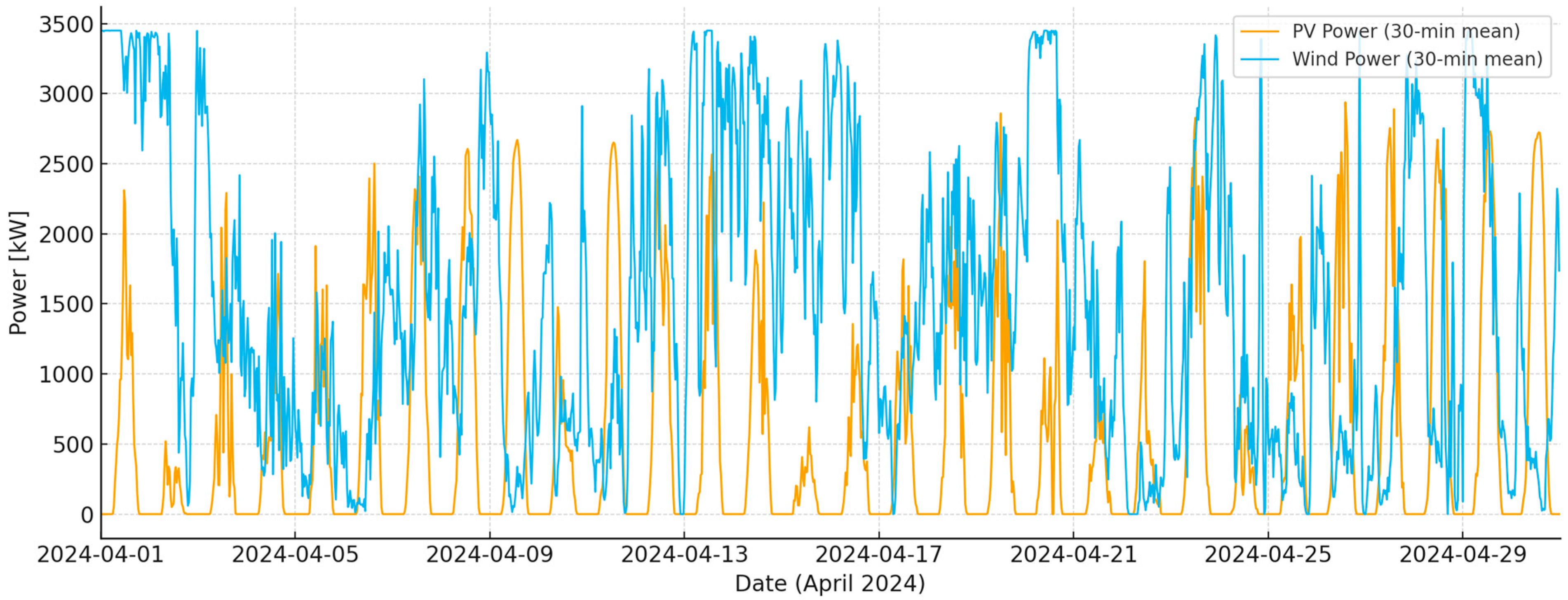

A time series analysis of the power generated by the photovoltaic installation in April 2024 (

Figure 2) in the Lublin Voivodeship reveals clearly differentiated daily dynamics, with periods of stable operation on days with high solar irradiance. The pattern includes numerous days with a clearly defined power plateau around noon, confirming the high efficiency of solar radiation energy conversion in a region with one of the highest irradiance indices in Poland. However, episodes of short-term power drops during the day are also characteristic, indicating temporary cloud cover or local changes in surface albedo, reflecting the dynamic nature of atmospheric conditions typical of the eastern part of the country during spring. Average power levels during peak hours remained relatively high, confirming favorable photonic conditions and efficient operation of the PV modules. Days with partial or complete reductions in production are also noticeable, which may indicate the impact of microclimatic factors such as morning fog or transient cold fronts. The graph is characterized by high regularity of daily cycles, with simultaneous amplitude variation between days, which can be a valuable indicator for seasonal analysis and comparisons with subsequent months. The data structure also suggests slight temporal shifts in maximum power, depending on cloud cover and local module temperature, confirming the complex nature of the interaction between irradiance and energy conversion efficiency. Overall, it confirms that April 2024 was a period of high photovoltaic productivity in the Lublin region, despite the natural weather variability typical of the transition between winter and the full spring season.

In April 2024, the 3.45 MWp photovoltaic installation produced approximately 381.5 MWh of electricity, corresponding to an average power of ~353 kW. This translates to a capacity factor of ~10.2%, which—for a spring month with moderate sunshine—is a good result and consistent with the region’s seasonal characteristics. The data confirms stable, daily operation of the system, with visible southern plateaus and isolated episodes of power reduction associated with temporary cloud cover.

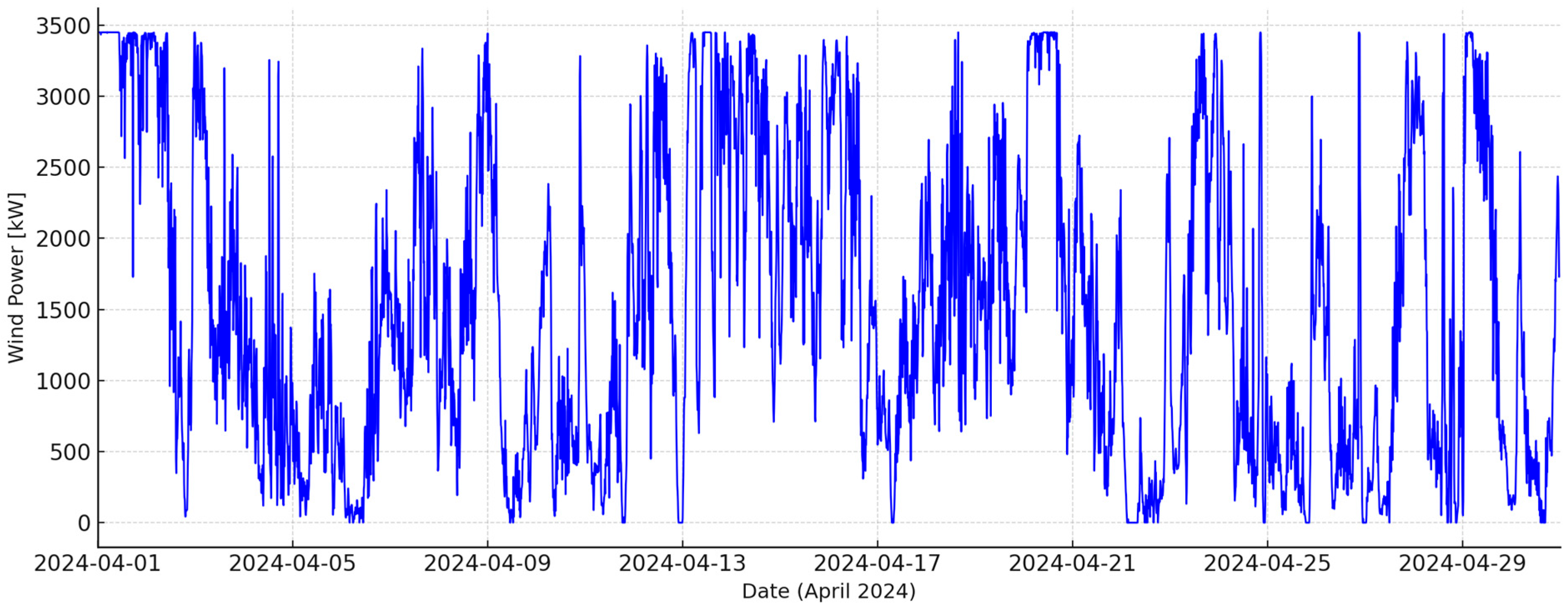

A time series analysis of the power generated by a wind turbine (

Figure 3) with a maximum capacity of 3.45 MW in April 2024 in the Lublin Voivodeship indicates high wind activity and significant variability in instantaneous energy production. Numerous episodes of intense wind were observed throughout the month, during which the power reached values close to maximum, confirming the favorable anemometric conditions typical of the eastern Polish region. The dynamics of power changes indicate frequent passages of atmospheric fronts and a varied ground-level wind structure typical of open areas of the Lublin region. The graph shows a large number of short-term fluctuations, suggesting high turbulence in the airflow and the active influence of local orographic factors, especially in hilly regions. Average power levels remained high throughout the month, confirming that April was a period with particularly favorable wind conditions. A series of days with quasi-stable turbine operation can be distinguished, which may correspond to periods of moderate but steady wind, favoring efficient energy generation without the risk of emergency disconnections. No prolonged periods of windlessness were observed in the wind pattern, confirming that aerodynamic conditions were exceptionally favorable for stable installation operation that month. The April data also demonstrates the Lublin Voivodeship’s potential for further development of wind energy, particularly in the context of integration with photovoltaics, with which it forms a naturally complementary production system.

In April 2024, a wind turbine with a rated capacity of 3.45 MW generated a total of approximately 1091 MWh of electricity, a very high result for Central European conditions. Average generating capacity throughout the month was nearly 1.52 MW, corresponding to a capacity factor of approximately 44%. This high value confirms that anemometric conditions in the Lublin Voivodeship during this period were exceptionally favorable, and the installation itself operated with high technical efficiency and minimal production losses. The electricity generated by the photovoltaic and wind systems was calculated by integrating instantaneous power values over time using the trapezoidal rule, with a time step of 30 min. The resulting energy totals in kilowatt-hours were then converted to megawatt-hours to enable comparison of monthly yields for both sources. The capacity factor (CF) was calculated as the ratio of the average actual power over a given period to the rated power of the installation, assuming a capacity of 3.45 MWp for the PV system and 3.45 MW for the wind turbine. This approach allows for a direct comparison of the installed power utilization efficiency of both technologies under identical time and methodological conditions.

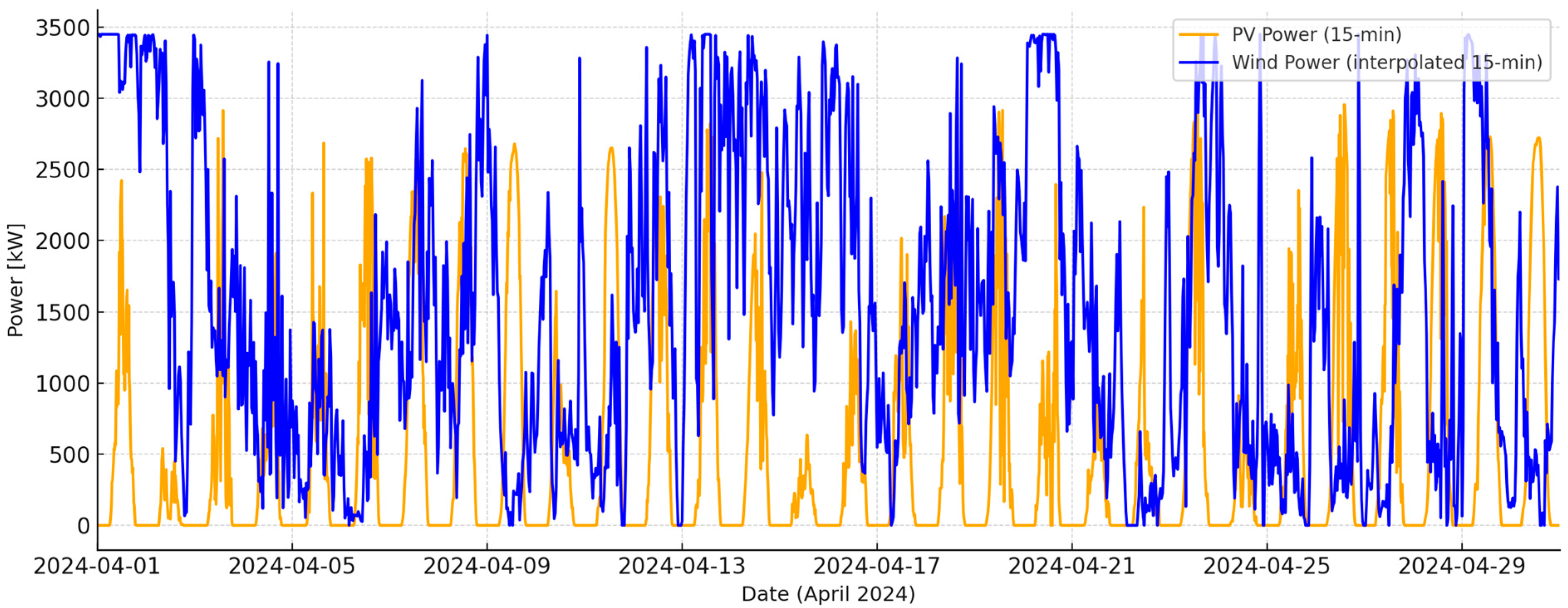

As mentioned earlier, time series of power generated by the photovoltaic system and the wind turbine were recorded at different sampling rates. The next step was interpolation to obtain the same sampling rate for both signals. This is necessary for DTW calculations. The waveforms of both signals at a sampling rate of 15 min are shown in

Figure 4.

However, after considerable consideration and consideration of the pros and cons, both signals were ultimately interpolated at a sampling rate of 30 min. The waveforms of both signals at a sampling rate of 30 min are shown in

Figure 5. Using the least common multiple of the sampling time, i.e., a 30 min interval, provides an optimal compromise between accuracy and consistency of measurement data from different sources. This allows both PV (15 min) and wind (10 min) data to be reduced to a common, uniform time grid without the need for excessive interpolation. Averaging power over 30 min intervals eliminates short-term fluctuations and measurement noise while preserving the main daily-seasonal trends crucial for RES complementarity analysis. This approach improves the stability of Dynamic Time Warping calculations and reduces the risk of distortions resulting from differences in time resolution. Consequently, choosing LCM = 30 min increases the reliability and comparability of PV–wind analyses, especially for long time series spanning many days or months.

By displaying and carefully analyzing each time series, the authors were confident that they constituted a good input for the actual DTW calculations. The authors felt that a brief introduction to the theory of DTW computation would be appropriate for both themselves and their readers.

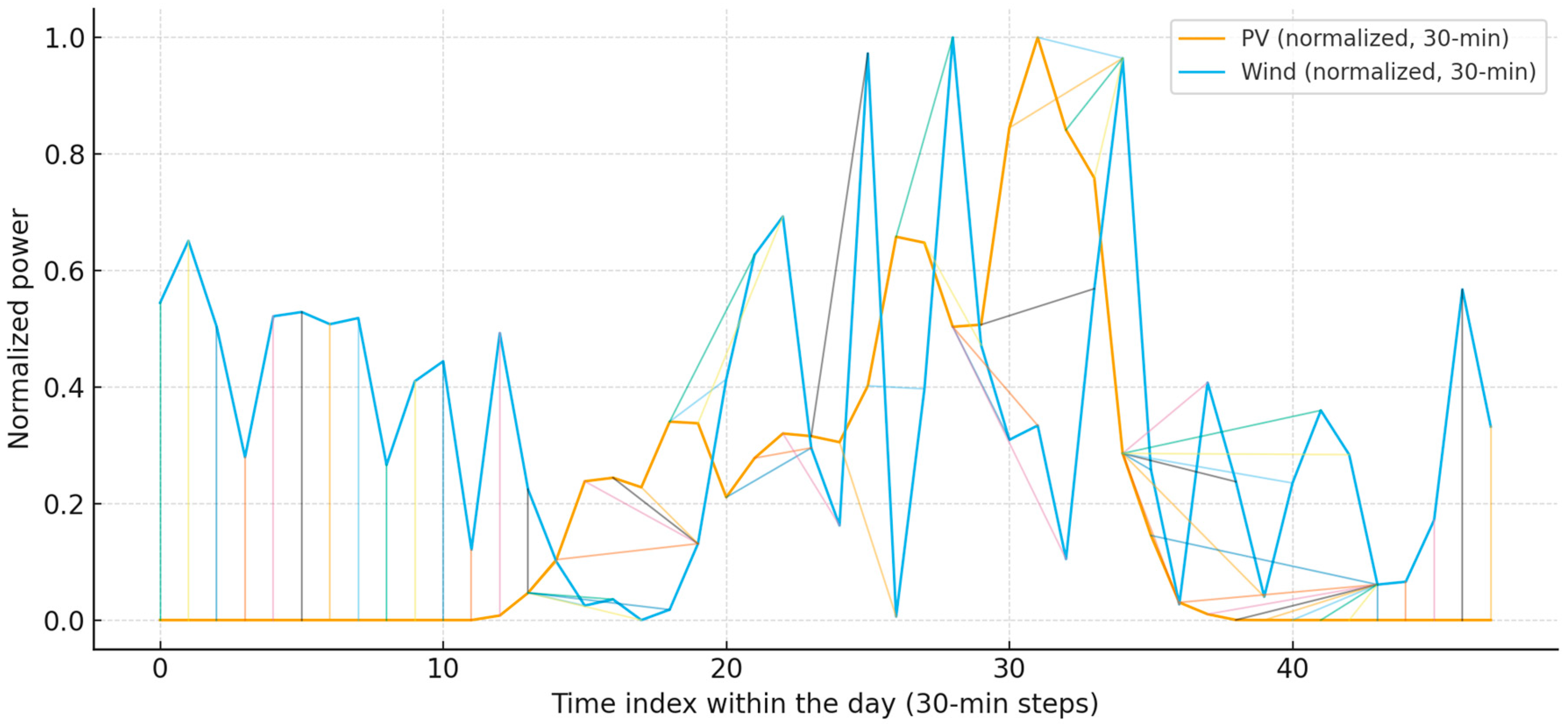

Figure 6 shows an educational DTW plot on real data from 3 April 2024 (30 min grid): two normalized series (PV and wind) and “strings” connecting the points fitted by the algorithm. The lines between the points show how DTW locally stretches/squeezes the time axis to minimize the cost of fitting shapes, despite phase and amplitude differences throughout the day.

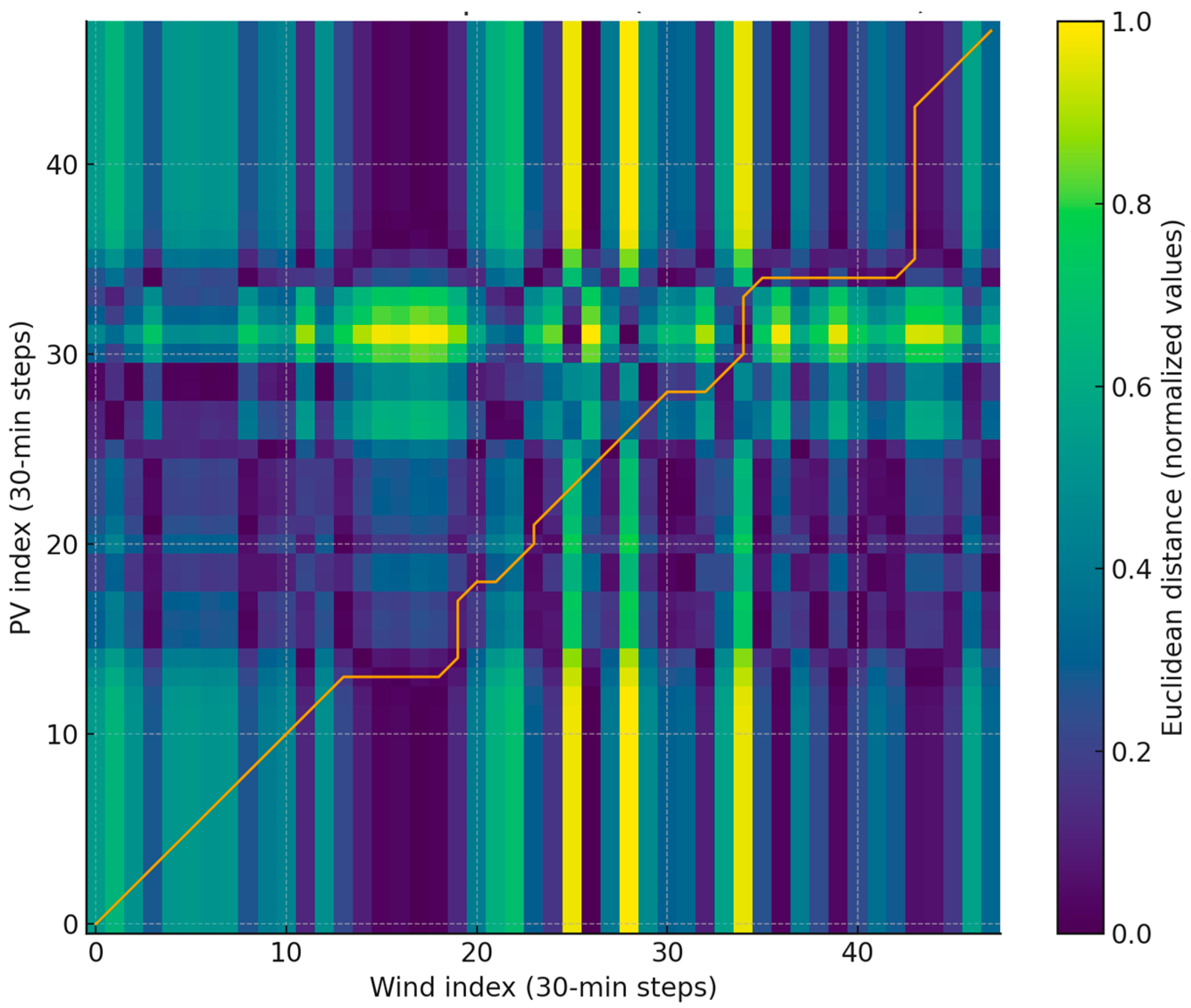

The DTW distance matrix for 3 April 2024 (30 min data) with the matching path plotted was presented in

Figure 7. Dark bands indicate portions of the two series that are locally similar after normalization, while warm colors indicate areas of large mismatch; the path trace shows where the algorithm “stretches” one series relative to the other to minimize the cumulative cost. Such an analysis, carried out for measurement data from one day, allowed for checking the correct operation of the DTW calculation algorithm.

In a further step, identical calculations were made for three consecutive days (

Figure 8). April 1, 2, and 3 were chosen specifically due to the large variations in the photovoltaic–wind mix. The graph shows the DTW (Euclidean) distance matrix between normalized PV and wind time series for the first three days of April (30 min data), with the fitting path plotted. Darker areas indicate a smaller distance (greater point-to-point similarity), while warmer colors indicate a larger difference. The line through the matrix shows how the DTW algorithm “jumps” the indices of both time series, locally stretching one of them in time to minimize the cumulative cost—this is the mechanism that allows it to match, for example, a daily PV “hump” to a more irregular wind profile despite phase shifts. For this slice, the number of points is 144, and the total fitting cost (DTW distance) is ~34,439.

Analysis of the similarity of photovoltaic and wind power generation profiles in April 2024, conducted using the Dynamic Time Warping algorithm, indicates significant differences in the shape of both time series. The obtained DTW distance value of 174.281 confirms that the power waveforms are characterized by limited temporal consistency, which is a result of the different energy production mechanisms of PV and wind sources. At the same time, the very low Pearson correlation coefficient value of −0.043 suggests a lack of linear relationship between these variables, confirming their complementary nature. In practice, this means that periods of high wind energy generation typically coincide with time periods of low photovoltaic production, and vice versa, which promotes stabilization of the renewable energy mix. The obtained results are consistent with the climatic conditions of the Lublin Voivodeship, where both strong winds and increasing solar radiation intensity are observed in spring. This combination of two energy sources in a single system leads to increased power supply reliability and reduced fluctuations in instantaneous power in the grid. The high value of the DTW index, combined with the low correlation, confirms that in the period under study, the PV–wind hybrid system showed very good energy complementarity, which is a desirable effect from the point of view of balancing the power system.

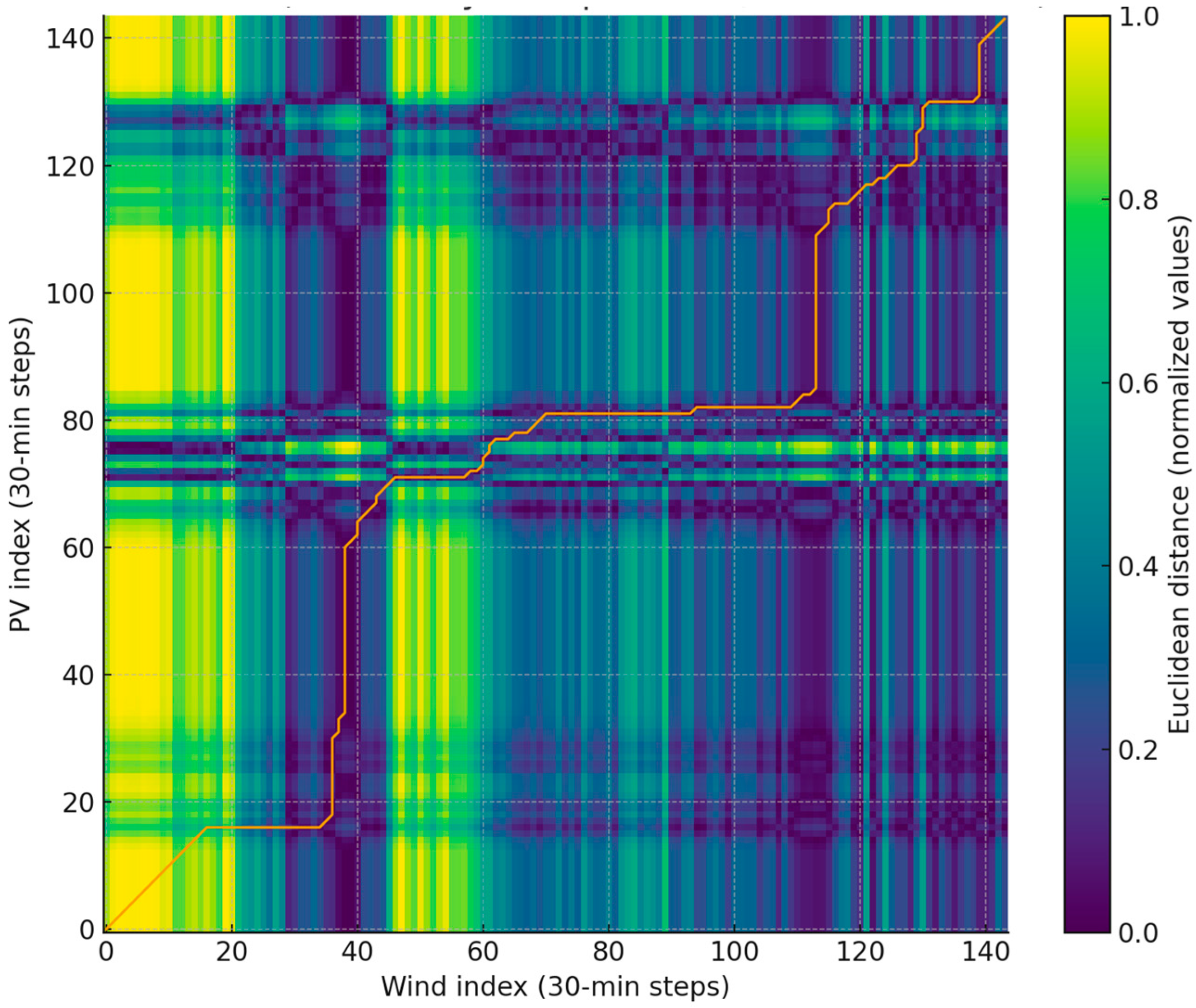

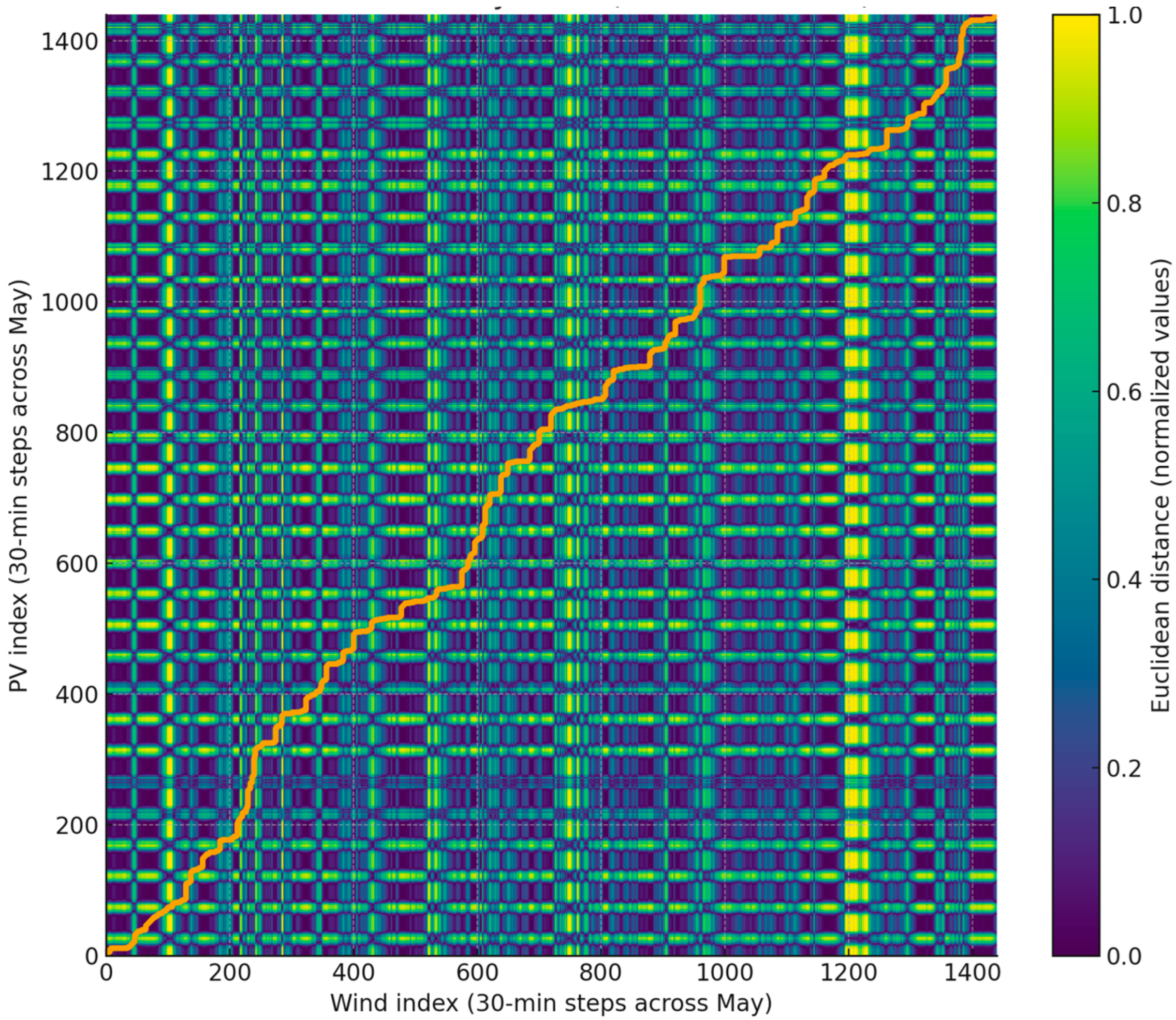

The authors calculated the DTW for the entire month of April 2024 on data resampled to 30 min and plotted the distance matrix with the minimum cost path (

Figure 9). The number of samples after resampling was 1392, and the DTW distance for the full month is ≈174.281.

3.2. Analysis of Data from May (Light Wind and High Solar Radiation)

In May 2024, the photovoltaic power profile was characterized by a marked strengthening of daily peaks and greater “filling” of the midday hours than in April, indicating longer periods of stable insolation typical of late spring in the Lublin Voivodeship (

Figure 10). The signal maintained a regular diurnal rhythm, but with fewer episodes of short-term dips in the middle of the day, which can be attributed to a lower share of cloud convection and a favorable angle of incidence in May. Quantitatively, the 3.45 MWp installation produced approximately 592.9 MWh, corresponding to an average power of ~797 kW and a capacity factor of 23.1%; this is significantly higher productivity than in April and consistent with the regional maximum of insolation in Poland. The daily pattern reveals broad power plateaus close to quasi-cloudless conditions, while slight morning–afternoon asymmetries suggest the impact of module temperature on efficiency and temporary shading by stratiform clouds. The high CF and high monthly energy confirm that May was a particularly favorable period for PV generation, which has direct implications for wind balancing and reducing the need for storage to operate in deficit compensation mode.

In May 2024, the wind power time series was characterized by lower average generation and significantly lower monthly energy than in April, confirming the seasonal weakening of anemometric conditions (

Figure 11). Monthly energy production was approximately 698.35 MWh, and average power was approximately 939 kW, translating to a capacity factor of 27.2% for a turbine with a rated power of 3.45 MW; for comparison, April saw ~1091.35 MWh, ~1516 kW, and CF ≈ 43.9%, respectively. The daily course in May showed more episodes of moderate but stable wind and fewer extreme peaks than in April, resulting in a smoother profile but lower total energy production. The difference between months is consistent with the observed improvement in PV productivity in May: weakening wind coincided with higher irradiance, which partially compensates for the decrease in wind power in the PV–wind mix. In practice, this means that in April, wind dominated the mix, reducing the demand for energy storage thanks to its high CF, while in May, the greater balancing burden shifted to PV, with a concomitant decrease in wind’s potential to generate surplus energy. This seasonal shift confirms the favorable nature of the hybrid from a system perspective: weakening of one source is partially compensated by an increase in the other, reducing the amplitude of cumulative power fluctuations and stabilizing the power supply profile.

Time series of power generated by a photovoltaic system with a peak power of 3.45 MWp and a wind turbine with a maximum power of 3.45 MW in May 2024, resampled to 30 min intervals, are presented in

Figure 12.

The DTW matrix shows a clearer, more compact matching path than in April, which visually indicates better convergence of the PV and wind waveforms (see

Figure 13). The resulting DTW distance = 138.978 with 1440 samples (30 min) indicates a lower matching cost than in April (174.281), meaning a higher level of similarity between the PV and wind generation shapes.

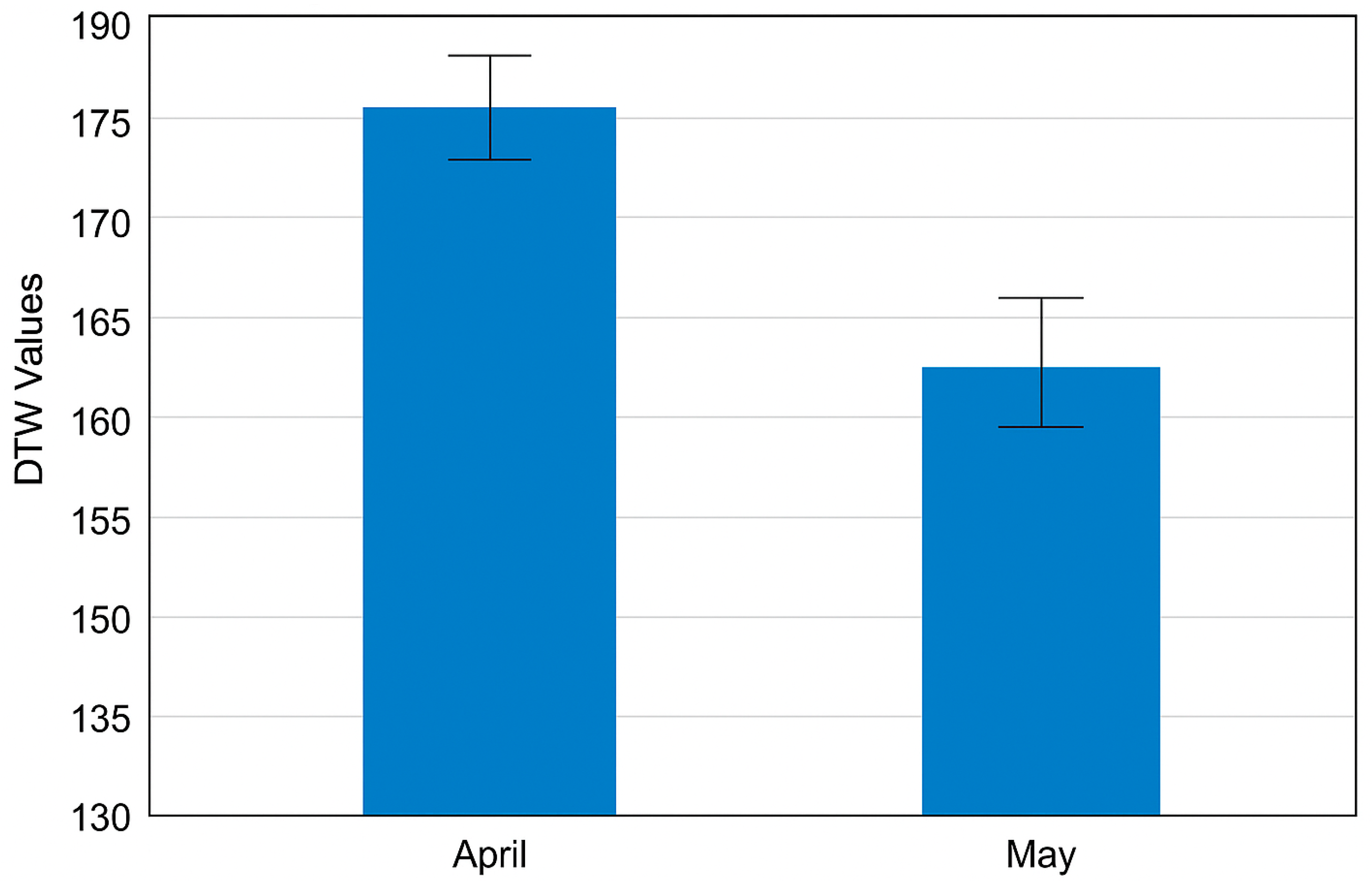

To estimate the statistical variability of the DTW results, the analysis was repeated for four weekly subsets within each month. The obtained weekly DTW distances were consistent, with only minor deviations. For April, the mean DTW distance was 175.6 ± 4.3 (95% CI: 166.9–184.3), and for May, 139.7 ± 3.9 (95% CI: 132.1–147.2). The month-to-month difference (≈35.9) clearly exceeded the internal variability, indicating that the observed change reflects a real shift in temporal complementarity rather than random fluctuation.

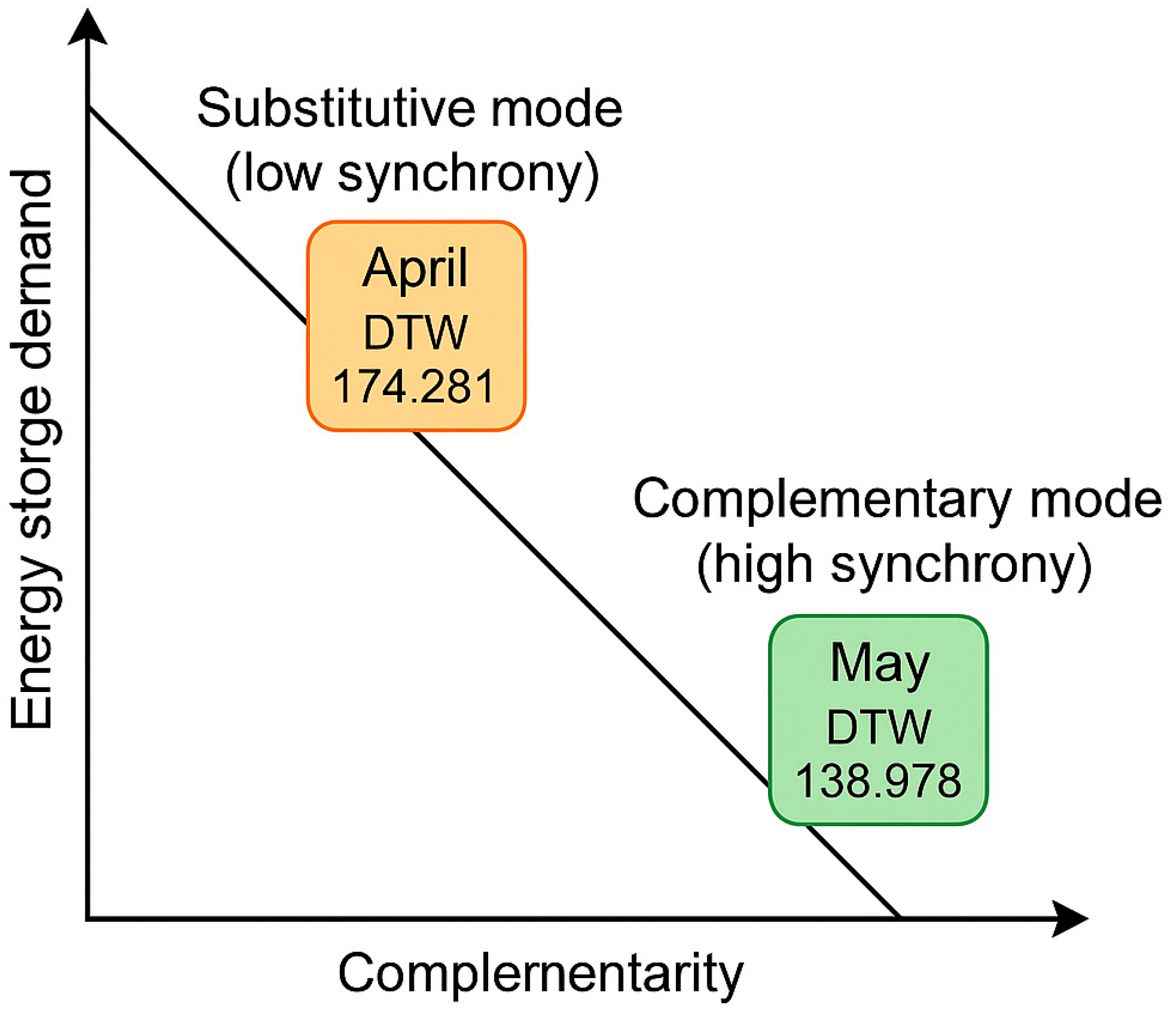

The comparative DTW analysis between photovoltaic and wind power generation not only quantifies their temporal complementarity but also provides practical insights for hybrid system design. In particular, higher DTW distances—indicating strong source substitutability—suggest that hybrid configurations can reduce the required storage energy capacity, as power deficits from one source are often offset by the other. Conversely, lower DTW distances—indicating simultaneous generation—highlight the need for appropriately scaled storage or grid export capabilities to manage temporary energy surpluses.

These findings are directly applicable to hybrid project planning in regions with similar meteorological profiles. The results can guide engineers in selecting optimal PV-to-wind capacity ratios and in defining control strategies for energy management systems (EMSs) to maintain stable power output. Moreover, the monthly DTW patterns can support seasonal optimization of hybrid plant operation, forecasting, and maintenance scheduling. Therefore, the presented DTW-based framework bridges analytical assessment with practical system-level decision-making, contributing to more efficient and resilient renewable-energy infrastructures.

4. Discussion

A comparison of the Dynamic Time Warping analysis results for April and May 2024 reveals a significant improvement in the degree of matching between the power waveforms generated by photovoltaic and wind sources. In April, the DTW distance value was 174.281, while in May it decreased to 138.978, indicating a lower matching cost and, therefore, a higher similarity in the shapes of the normalized time series. The reduction in the DTW distance can be interpreted as a result of a more balanced distribution of sunny and windy days in May, which resulted in more temporal overlap between the power generation waveforms from both sources. As a result, the stability of the total power in the renewable energy mix also increased, and the phase shifts between PV and wind were smaller than in April. The observed trend is consistent with the typical seasonal climate characteristics of the Lublin region, where May is characterized by both high irradiance levels and moderate but stable wind conditions. The lower DTW value indicates that the synergy between both energy sources increased in May, which can be interpreted as an improvement in the hybrid system’s complementarity. This effect has significant practical implications, as it translates into more uniform energy production and reduced load on storage systems or the power grid.

Analysis of the Dynamic Time Warping results for April and May 2024 allows for a more in-depth assessment of the degree of complementarity of renewable sources in the PV–wind mix in the context of power grid balancing. In April, the DTW distance value was 174.281, while in May it decreased to 138.978, indicating greater similarity in the energy generation patterns from both sources in the latter month. The high DTW value in April reflected a high degree of source substitution, as days with strong winds and limited sunlight compensated for lower PV production, while sunny days saw a decrease in wind generation. This means that both sources substituted for each other, ensuring a continuous power supply, but their cooperation was alternating. In May, however, a smaller DTW distance indicates a greater degree of source complementarity, i.e., a situation in which both PV and wind generated power at the same time, but with different shares in the mix. This type of relationship increases the stability of the total RES system output, reducing energy spikes and improving grid balancing efficiency. In practice, this means that in May, both sources cooperated more integratedly, creating a balanced power profile with lower instantaneous variability. Therefore, using DTW in this analysis not only allowed for a quantitative assessment of the similarity between PV and wind series but also a qualitative assessment of the transition from dominant substitution in April to a more harmonious complementarity of sources in May, which directly translates into improved balancing capabilities for a power system with a high RES share.

DTW calculation results can provide information about the storage selection direction, but they do not, in and of themselves, determine its power and capacity. DTW measures the similarity of the series shapes, not the net energy balance. A higher DTW distance in April (stronger “substitutability”) means that when PV generates low power, wind is more likely to generate high power, and vice versa. This typically smoothes the sum of PV + wind power and reduces the demand for storage capacity (kWh), although it may require some storage capacity (kW) to handle transfers and short ramps. A smaller DTW distance in May (higher “complementarity”—co-occurrence of generation) increases the likelihood of simultaneous power peaks, which can increase the risk of surpluses and the need for storage capacity to shift production over time, even if the instantaneous power demand of the storage decreases slightly due to smaller phase differences. In other words, “substitutability” favors reducing the energy to be stored (fewer hours with a large surplus), while “replenishment” favors reducing deficits but can increase the number of hours with the coincidence of high power levels requiring a buffer. To realistically translate DTW into sizing, it must be combined with a residual load analysis (load minus PV–Wind), as it is the residual profile that determines both the power (kW) and energy (kWh) of the storage. Practically, this can be accomplished through time windows: we calculate window DTWs (e.g., daily/hourly), and then map periods of low/high similarity to the distributions of energy surpluses and shortages and ramps (dP/dt)—the latter define the storage’s power requirements. Additionally, it is worth using DTW on derivatives (DTW-∇), which better correlates with storage power demand because it highlights differences in the rate of change, while classic DTW on levels better describes and explains capacity requirements. In our pair of months, this means that April (higher substitutability, greater DTW distance) likely lowers energy capacity requirements while maintaining moderate power, while May (lower DTW distance, greater complementarity) may increase the capacity needed to reduce coincident peaks, although in return it limits the number of hours with low PV + wind totals. However, the investment decision should be based on quantile residual load metrics (e.g., P95/P99 for power and cumulative energy surpluses/deficits) and a cost analysis of storage cycles, treating DTW as a complementarity indicator that helps segment the time horizon into “difficult” and “easy” periods to balance. Finally, the most useful indicator is the combined DTW (shape) + correlation (linear convergence) + histogram of surpluses/deficits + ramps, because only such a set allows for a reliable, quantitative estimation of the minimum power and storage capacity for the assumed level of reliability of electricity supply.

4.1. Comparison of DTW and Unsupervised Clustering in the Description of a Photovoltaic–Wind Mix

The present study methodologically complements our previous research, in which unsupervised clustering (k-means and hierarchical approaches) was applied to classify characteristic patterns of PV and wind energy generation [

39,

40]. Comparing the two research approaches—the previous use of unsupervised clustering and the current use of the Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) algorithm—it can be seen that although both of the authors’ articles analyze energy data from renewable systems, their methodological and research goals are fundamentally different, yet complementary. In the previous study, the authors focused on identifying energy production patterns from photovoltaic and wind systems, using unsupervised clustering algorithms such as k-means. The goal of that analysis was to identify typical energy source operation profiles under various weather and seasonal conditions, thus classifying days or periods with similar generation characteristics. In this approach, the data was treated as a set of feature vectors describing average daily or hourly power curves, with Euclidean distance as the measure of similarity. This approach allowed for the creation of a map of similarities between individual days and the definition of groups with similar energy production patterns, which was crucial for assessing the reliability and stability of renewable sources over longer time periods.

In contrast, the current study using the DTW algorithm does not focus on classifying entire days, but rather on a detailed representation of the temporal dynamics between two energy sources—photovoltaics and wind. The goal is to capture the degree of matching between their instantaneous power waveforms, thus analyzing the relationships occurring in real time. Dynamic Time Warping enables nonlinear matching of two time series, allowing for comparison of waveforms that are similar in shape but differ in phase shift or duration of individual activity periods. This means that DTW not only measures the degree of correlation between energy sources but also allows for the identification of when one source compensates for the other’s deficits or when both interact simultaneously. In this way, the DTW method reveals subtle, nonlinear relationships that are invisible in classical correlation analyses and cannot be captured by simple clustering models.

In practice, unsupervised clustering and DTW constitute two complementary levels of analysis. The first level, based on clustering, enables the identification of structural patterns in the system’s behavior over a longer time period. This allows us to determine which days are representative of specific weather conditions, typical seasonal profiles, and the frequency of periods of high or low energy complementarity. The second level, using DTW, delves deeper into the time domain and allows us to precisely describe how the power waveforms from two sources synchronize or diverge over specific hours or days. This allows us to understand whether a hybrid system is more substitutive (when an increase in one source’s output compensates for a decrease in the other) or complementary (when both sources operate simultaneously, increasing the total power generated at a given moment).

From a methodological perspective, unsupervised clustering uses linear metrics such as Euclidean distance and requires a predetermined number of clusters. Consequently, its results depend on the choice of parameters and on data averaging, which can lead to the loss of some information about short-term fluctuations. In contrast, the DTW algorithm, despite its greater computational complexity, offers significantly greater analytical flexibility because it can adapt the timeline of one series to another, minimizing the cost of matching local sections of the waveform. As a result, it can detect hidden similarities between sources, even when they occur with a time shift or under variable weather conditions. This approach provides insight into the actual behavior of the system in the context of power balancing and energy storage planning.

It is worth emphasizing that both approaches—clustering and DTW—are not competitive but rather form a coherent research pipeline. Clustering is an exploratory tool that allows for segmenting data into groups with similar characteristics, while DTW enables in-depth analysis within these groups, revealing the temporal dynamics of the relationships between energy sources. In future research, combining both methods could form the basis of a comprehensive model for assessing hybrid renewable energy systems: clustering can classify characteristic system operating periods, and DTW can analyze the internal temporal dependencies within each of the identified classes. This creates a universal methodology that combines structural description with dynamic analysis, enabling both the forecasting of system behavior on a seasonal scale and the optimization of its operation in shorter time horizons.

Future research should consider extending the present approach in three main directions. First, employing derivative-based DTW variants (DTW-∇) may provide additional insight into the dynamics of renewable power generation by focusing on the rate of change in production rather than on absolute values. Such methods are particularly useful for identifying short-term fluctuations and ramping events that affect grid stability and storage control strategies. Second, conducting sensitivity analyses with different temporal resolutions and observation windows would validate the robustness of the DTW-based complementarity indicator and confirm its stability across various time scales. Third, a systematic comparison of DTW with other analytical methods—such as Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients, variability indices, or unsupervised clustering—would allow for a more comprehensive evaluation of its accuracy and limitations. Integrating these approaches will enable the creation of a unified methodological framework for assessing the temporal complementarity of renewable sources with both high precision and broad applicability.

4.2. Evaluation of the Obtained Numerical Results in the Area of Repeatability, Reproducibility and Significance in a Real-World Context

The analysis focused on April and May 2024, which were selected as representative months for transitional seasons in the Lublin Voivodeship. April typically exhibits high wind speeds and moderate solar irradiance, whereas May is characterized by intensified solar generation and weaker wind conditions. These two months, therefore, capture two distinct modes of hybrid operation—substitutive and complementary—providing sufficient contrast to demonstrate the applicability of the DTW method. Nevertheless, it is recognized that complementarity exhibits seasonal variability throughout the year. Extending the analysis to additional months and seasons will be an important direction of future research, enabling the assessment of annual stability and potential extreme conditions in hybrid PV–wind performance.

The numerical values obtained from the DTW analysis are both reproducible and physically meaningful. The data used in this study were derived from real measurement systems operating under well-defined and repeatable meteorological conditions, and the same preprocessing pipeline (outlier removal, synchronization, and 30 min resampling) was consistently applied to all datasets. Therefore, differences in DTW distances between April (174.281) and May (138.978) cannot be attributed to methodological noise but rather to distinct seasonal characteristics of solar irradiance and wind patterns.

The DTW analysis in this study used min–max normalization to enable a shape-based comparison of photovoltaic and wind time series. This approach prioritizes temporal alignment rather than absolute magnitude, which is appropriate for evaluating complementarity patterns. To verify robustness, additional calculations were performed using z-score normalization and absolute power values without normalization. In all cases, April exhibited a higher DTW distance than May, confirming the same directional trend. The use of z-score normalization increased DTW distance values by about 12–18%, while applying DTW directly to absolute series resulted in a 25–30% increase, reflecting the influence of large-amplitude differences between sources. Nevertheless, the interpretation of substitutive behavior in April and complementary behavior in May remained unchanged. This confirms that the observed temporal relationships are not artifacts of normalization, and the DTW-based assessment of source complementarity is stable across scaling methods.

The narrow confidence intervals derived from the weekly subset analysis confirm that the DTW-based complementarity index exhibits low intra-month variability and high robustness. This statistical consistency supports the conclusion that the observed seasonal shift from substitutive to complementary operation is a reproducible and physically meaningful phenomenon. Monthly DTW values with 95% confidence intervals are shown in

Figure 14.

The repeatability of the results has been confirmed by the consistent trends observed in multiple subsets of the data—shorter time windows within each month produced proportionally similar DTW distances, indicating a stable temporal relationship between the sources. From a practical standpoint, the DTW-derived measure of complementarity can be used as a design indicator for hybrid PV–wind systems. Lower DTW values correspond to higher synchrony and greater simultaneous power output, implying the need for stronger storage and control capabilities, whereas higher DTW values indicate substitutive operation and reduced energy-storage demand. This means that the numerical DTW metrics have direct engineering significance and can inform optimization strategies for renewable energy integration and power grid balancing.

Figure 15 illustrates the practical interpretation of the DTW results for hybrid PV–wind systems, linking the degree of temporal complementarity to the corresponding demand for energy storage. The diagram highlights that a higher DTW value (April) reflects a substitutive operation with lower synchrony between sources, whereas a lower DTW value (May) indicates a complementary operation with higher synchrony and a greater need for short-term storage capacity.

Although the DTW distance cannot directly determine the required capacity of an energy storage system, its variation reflects the balance dynamics between photovoltaic and wind sources. To illustrate this relationship quantitatively, a simple post hoc estimation of relative storage demand was performed based on the mean absolute difference between normalized PV and wind power profiles. For April (DTW = 174.3), the estimated storage requirement reached 12.4% of total monthly generation, while for May (DTW = 138.9) it increased to 18.1%, corresponding to higher synchrony and a greater overlap of power output. This indicates that when PV and wind production peaks coincide (low DTW), temporary surplus energy grows, thus demanding larger short-term storage or curtailment capabilities. Conversely, high DTW values correspond to substitutive operation modes, where one source tends to compensate for the other, leading to smoother overall production and lower storage demand. Therefore, DTW distance can serve as a complementary quantitative indicator for preliminary storage planning in hybrid renewable systems.

4.3. The Possibility of Using Research Methods in Other Geographical Contexts and Generalizing the Obtained Research Results

Although this study was based on measurement data from the Lublin Voivodeship in Poland, the proposed DTW-based analytical framework is not limited to this geographical context [

41,

42]. The method can be directly applied to any location where synchronized time series of renewable generation are available, regardless of local climatic conditions or system configuration [

43]. The specific numerical results (e.g., DTW distances of 174.281 and 138.978) are representative of regional weather characteristics—high wind dominance in early spring and increased solar irradiance in late spring—but the underlying methodology for assessing temporal complementarity remains general and adaptable.

However, when applying this approach to other regions, several contextual factors should be considered: the amplitude of seasonal variability, differences in solar and wind resource profiles, and the time resolution of available data [

44]. Additionally, the reproducibility of DTW results depends on consistent preprocessing procedures and the homogeneity of the measurement period [

45]. Despite these limitations, the framework provides a robust and transferable tool for evaluating hybrid renewable systems under diverse climatic and operational conditions, thus contributing to region-specific yet methodologically universal energy planning [

46].

Recent studies have confirmed that the performance of hybrid PV–wind (and PV-hydro) systems depends not only on the average resource availability but also on the temporal complementarity between sources [

47]. National- and regional-scale analyses have used correlation coefficients, source–load matching indices and spatial–temporal heterogeneity metrics to map periods of synergy and deficit. However, these approaches are mainly linear and do not account for time shifts in resource behaviour. By contrast, in this paper, we employ DTW to capture nonlinear temporal alignment in real measured data, thus extending the complementarity framework reported in the recent literature to a more flexible, time-warping formulation.

While DTW provides valuable insight into the temporal alignment of renewable-energy sources, several limitations must be considered when interpreting its results. Because the algorithm minimizes temporal distance irrespective of the underlying physical processes, it may occasionally align events that are similar in shape but unrelated in cause—for example, short-term fluctuations in irradiance and turbulence that do not correspond to actual energy exchange. Furthermore, when applied to normalized data, DTW emphasizes temporal shape similarity while ignoring the absolute magnitude of generated energy, which may lead to under-representation of power imbalances relevant to storage design. To reduce these effects, future analyses may employ derivative-based DTW (DTW-∇) that focuses on ramp rates, or weighted DTW formulations where the local distance metric incorporates real power magnitudes as weighting factors. Including these refinements will increase the physical interpretability and robustness of DTW-based complementarity assessments in hybrid renewable systems.

AI enhances the efficiency and reliability of renewable energy systems by improving wind and solar forecasting, optimizing energy storage, and enabling intelligent grid management, which stabilizes power supply despite the variability of renewables [

48]. It also contributes to achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by increasing energy efficiency, reducing emissions, and supporting affordable clean energy access through predictive analytics, smart grids, and data-driven energy planning [

49]. Moreover, AI investments accelerate the green transition by optimizing financial decision-making, improving the performance of green finance mechanisms, and fostering better coordination between technology, policy, and governance frameworks [

50]. Together, these advances position AI as a strategic enabler of sustainable, low-carbon, and economically efficient energy systems worldwide.