1. Introduction

Slate is a typical layered rock mass, usually involving dense plate cleavage, and belongs to the class of regional metamorphic rocks. It generally contains extensive layered structures and often displays different mechanical properties under different inclination angles. With the continuous growth of the national economy, the underground engineering construction industry has developed rapidly, and there are often situations during the construction process where it is necessary to cross slate formations. The special mechanical properties of slate have caused many adverse effects on the construction of related projects [

1]. It is therefore necessary to carry out research on the deformation characteristics of layered slate foundation pits with different inclination angles.

Under conditions of varying inclination angles, the physical and mechanical properties of slate often have a significant impact on the deformation of foundation pits. Gholami et al. [

2] conducted research on the elasticity and strength characteristics of slate from the Sardasht Dam site in Iran. They evaluated dry and wet samples with different bedding orientations under uniaxial compression, triaxial compression, and Brazilian splitting tests, and found that there was a significant correlation between the strength and inclination angle in uniaxial and triaxial compression tests for dry samples. However, in the Brazilian splitting tests, there was no obvious relationship between inclination angle and tensile strength. The results of uniaxial and triaxial tests by Hao et al. [

3] showed that the deformation modulus of slate reached a maximum when the bedding inclination was 75–90° and was minimal when the inclination was 45–60°. Li et al. [

4] carried out Brazilian splitting tests on carbonaceous slate samples and reported that with an increase in the dip angle, the failure mode of the dried samples changed from symmetrical tensile failure along the loading axis to tensile shear and pure tensile failure modes. Static weathering specimens were more significantly affected by bedding, with failure modes including tensile-shear failure and combined tensile-shear failure between the matrix and bedding surface. Zhao et al. [

5] found based on uniaxial compression tests of slate that the peak load exhibited a U-shaped distribution with increasing inclination, and the failure modes under different bedding inclinations varied, including splitting tensile failure, shear slip failure, and composite tensile-shear failure. Hu Taotao et al. [

6] conducted Brazilian splitting tests and discovered that the tensile strength of carbonaceous slate also followed a U-shaped pattern with increasing inclination of the rock layer. Bao Weixing et al. [

7] conducted freeze–thaw cycle tests, and reported that the bedding inclination of slate had a significant impact on the location of freeze–thaw damage and the resistance to freeze–thaw. The magnitude relationship of the inclination angle of each bedding resisting freeze–thaw action was 0° > 90° > 45°. The studies described above mainly explored the macroscopic mechanical properties of slate under different inclinations and described the related physical and mechanical characteristics.

The various physical and mechanical properties of slate can affect underground engineering, especially deep foundation pit operations, while the surrounding environment can also significantly impact the bearing capacity of slate. Ma et al. [

8] utilized non-destructive and non-invasive testing methods involving micro-CT and ultrasonic wave velocity testing to examine the internal microstructure of rocks under wetting-drying cycles. Sun et al. [

9] explored the precursors of failure in layered slate, analyzed the failure modes, acoustic emission parameters, and multifractal characteristics of slate with different bedding angles, and identified the ultimate failure precursors and early warning events based on multifractal analysis. Zhang et al. [

10] conducted uniaxial compression, acoustic emission detection, and scanning electron microscopy tests on carbonaceous slate from the Jinman Mine in the Lancang River Gorge and found that the failure modes and fracture characteristics were closely related to the layered structure of the slate. Under vertical and parallel loading conditions, slate primarily undergoes shear failure and tensile failure, respectively. Li et al. [

11] studied carbonaceous slate samples from the Muzhailing Tunnel in Shaanxi, and conducted a series of Brazilian split tests and numerical simulations considering different angles of layering using the cohesive zone model (CZM), in which failure can be categorized into approximately pure tensile, shear, and mixed tensile-shear failure. Wen Tao et al. [

12] investigated the variation in the reaction energy and conducted a damage analysis under different confining pressures, based on the results of triaxial tests on slate under various confining pressures. These authors concluded that low confining pressure conditions corresponded to lower dissipated energy and higher damage values, while high confining pressure conditions corresponded to higher dissipated energy and lower damage values. Li Bo [

13] studied the influence of the deterioration mechanism of the surrounding rock properties on slate tunnels based on an engineering background involving blasting and the occurrence of a negative water environment. The studies described above show that the final bearing capacity and physical and mechanical properties of slate with different bedding dip angles vary under the influence of the surrounding environment.

Most existing studies have focused on the macroscopic mechanical properties of slate with different bedding inclinations, lacking a systematic analysis that links experimental results with the deformation responses observed in actual engineering projects—particularly insufficient attention has been paid to the foundation pit deformation laws under the combined action of bedding dip angles and surrounding rock environments. In this study, laboratory uniaxial and triaxial compression tests, numerical simulations, and engineering case analyses were integrated to systematically investigate the deformation characteristics of foundation pits in layered slate strata with varying inclinations. By introducing smooth joint and parallel bond models into the particle flow framework, the mesoscopic parameters were calibrated and the macroscopic responses were verified, revealing the asymmetric deformation patterns of foundation pits induced by bedding inclination. This study provides a scientific basis for the support design, deformation control, and stability evaluation of slate foundation pits with different bedding inclinations and offers valuable references and guidance for the design and construction of metro and tunnel projects in layered slate regions.

3. Verification of a Numerical Model of Slate

3.1. Physical Model

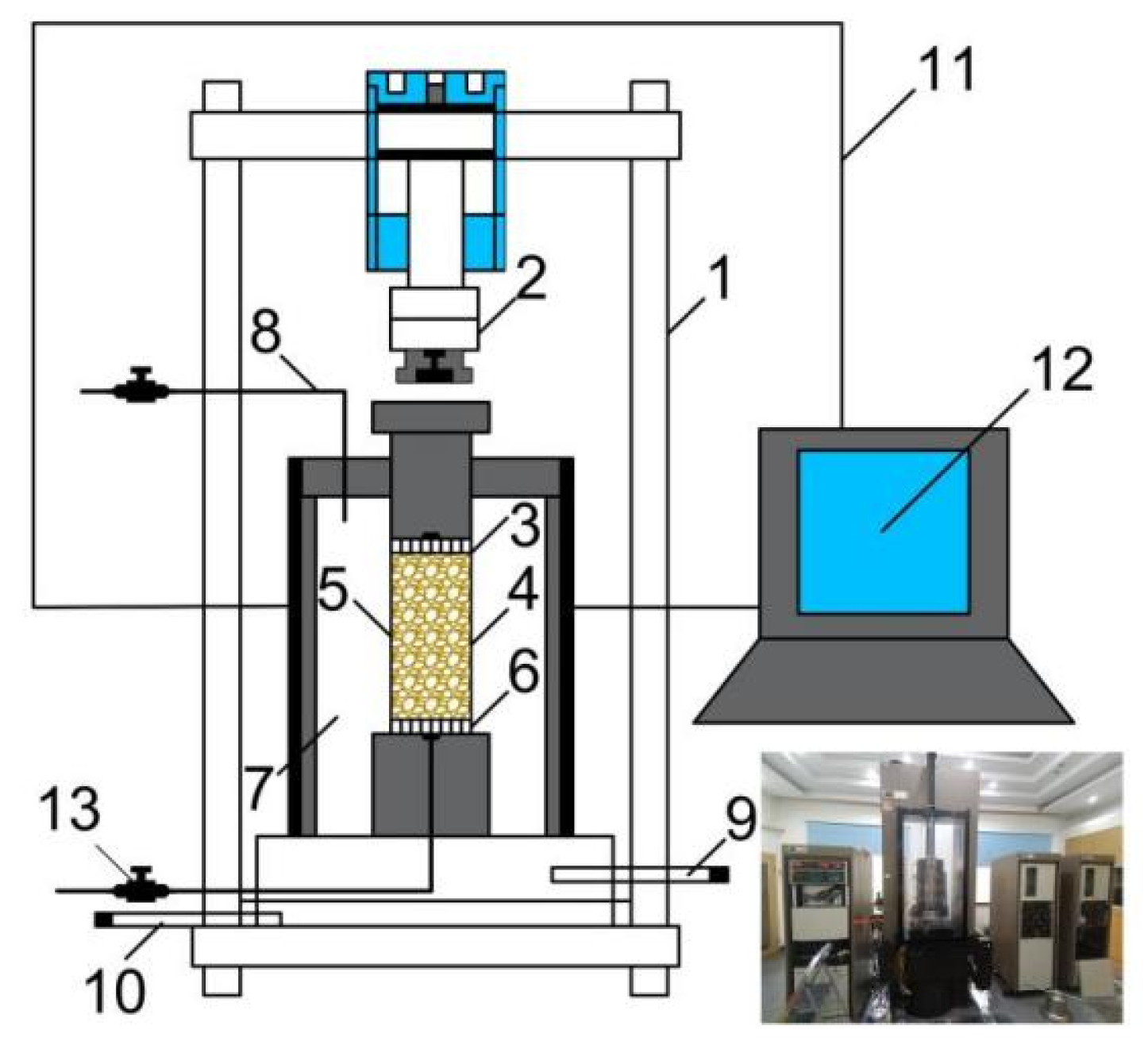

As shown in

Figure 5, a numerical simulation sample with the same dimensions as the indoor test was generated, with a diameter of 50 mm and a height of 100 mm. The contact between particles in the rock matrix was set to a parallel bond model, to impart the characteristics of rock to the sample. Subsequently, using the discrete fracture network (DFN), 12 mm bedding planes were established at equal intervals, and the contact between particles within these bedding planes was set to a smooth joint model, to impart the characteristics of bedding to the sample. The entire sample contained a total of 15,136 particles with uniformly distributed particle sizes. The minimum radius of the particles in the sample was 0.5 mm, the ratio between the maximum and minimum particle sizes was 1.66, and the particle density was 2700 kg·m

−3.

It is worth noting that the bedding spacing between the numerical simulation samples and the actual samples differed, as the actual sample spacing was only 0.7–4 mm. This difference arose mainly from consideration of the particle size effects and the fact that too many embedded smooth joint models can significantly reduce the calculation speed, meaning that the numerical simulation model needed to be simplified.

3.2. Parameter Calibration

To accurately simulate the mechanical behavior of slate with different bedding inclinations, the mesoscopic parameters of the discrete element model were calibrated based on the results of laboratory tests. The bedding inclination was achieved by adjusting the orientation of the smooth joint models distributed within the specimen. Therefore, the mesoscopic contact parameters were calibrated according to the uniaxial and triaxial compression test results, providing the basis for subsequent numerical simulations. The asterisk (*) denotes a parameter calibrated via laboratory tests.

Initially, it was necessary to calibrate the mesoscopic parameters (elastic modulus, stiffness ratio, tensile strength, cohesion, internal friction angle) of the parallel bond model. The elastic modulus of the slate specimen with a bedding inclination of 90° was selected as the reference, and the elastic modulus and stiffness ratio of the parallel bond model were determined using a trial-and-error method [

15,

16]. Subsequently, the compressive strength of the specimen with a 0° bedding inclination was used as the reference to calibrate the tensile strength, cohesion, and internal friction angle. The calibrated mesoscopic parameters of the parallel bond model are listed in

Table 1.

The mesoscopic parameters (horizontal stiffness, tangential stiffness, tensile strength, cohesion, internal friction angle) of the smooth joint model were then calibrated to accurately simulate the mechanical properties of the rock bedding planes. The values for the elastic modulus of slate samples with bedding angles of 30° and 60° were selected as benchmarks to calibrate the horizontal stiffness and tangential stiffness of the smooth joint model, respectively. This is because the elastic modulus for sample models with bedding angles of 30° and 60° is significantly influenced by the horizontal and tangential stiffness [

17]. Finally, the compressive strength curves obtained from tests at bedding angles ranging from 0° to 90° were considered. Initially, the internal friction angle was set to zero, and the cohesion and normal strength were adjusted to match the minimum compressive strength. Following this, the joint internal friction angle and friction coefficient were further adjusted to better fit the compressive strength curve. The calibrated mesoscopic parameters of the smooth joint model are presented in

Table 2.

3.3. Verification of Simulation Results

To verify the rationality of the mesoscopic parameter selection, numerical models were established using the parameters from

Table 1 and

Table 2. These models simulated triaxial compression tests on samples with different bedding angles (0°, 30°, 45°, 60°, 90°) under various confining pressures (0, 5, 10, 15 MPa). The results were then compared and validated against the laboratory test results.

Figure 6 compares the results for the peak compressive strength obtained from numerical simulation and experiment. The maximum difference between the results is 22.29 MPa (at a confining pressure of 15 MPa and a bedding inclination of 30°), with a relative error of 15.57%. In terms of the pattern of variation in the peak compressive strength with bedding, both the numerical simulations and experiments show that the peak compressive strength follows a U-shape as the bedding inclination increases. More specifically, the peak compressive strength first decreases and then increases with an increase in bedding inclination, reaching its lowest value at 60°.

Figure 7 compares the results for the elastic modulus obtained from numerical simulation and indoor experiments. In terms of elastic modulus values, the maximum difference between the experimental and indoor simulation results is 1.93 × 10

3 MPa (with confining pressure of 60 MPa and bedding inclination of 0°), with a relative error of 11.69%. Regarding the changes in the elastic modulus with bedding inclination, both indoor experiments and numerical simulation follow a U-shaped trend as the bedding inclination increases. The indoor experimental results reach a minimum at a bedding inclination of 45°, while the numerical simulation results are minimal at 30°.

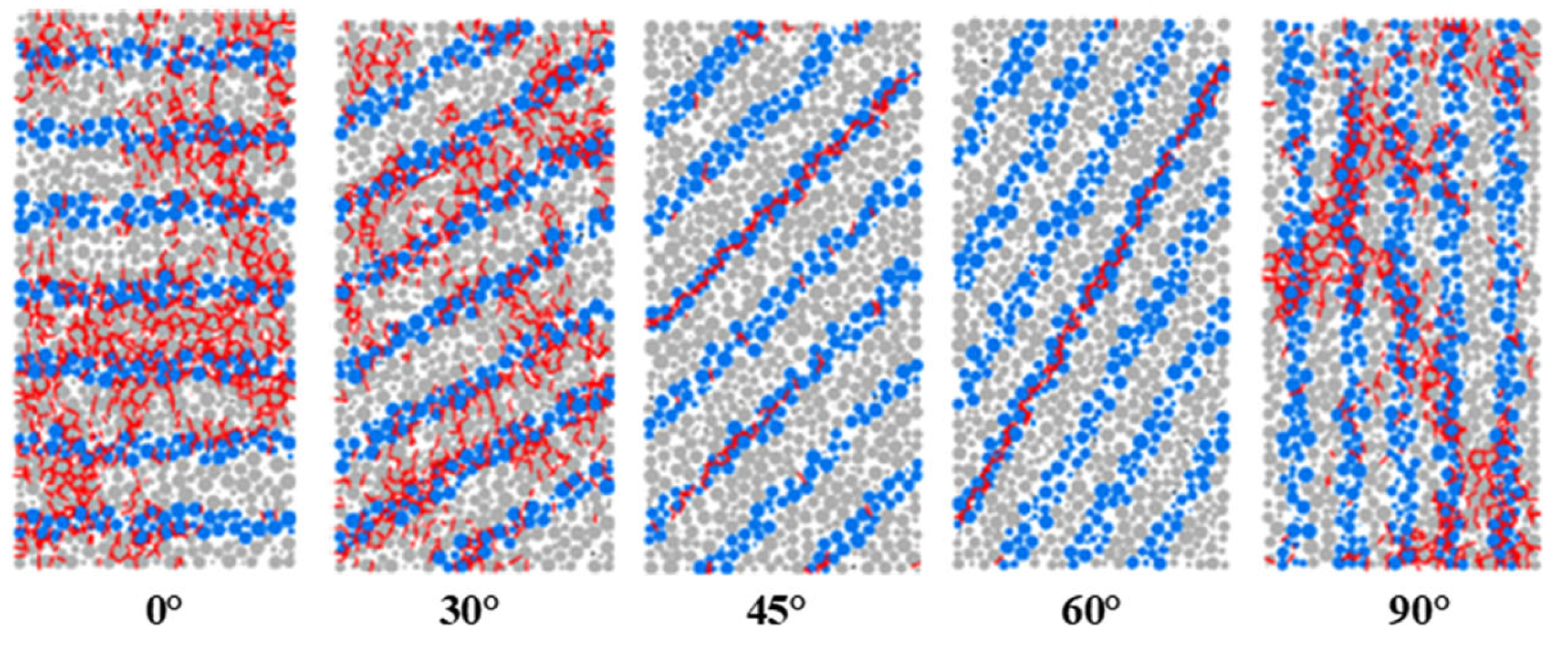

To verify the numerical model for the failure mode of slate, five sets of laboratory test samples with confining pressures of 10 MPa and bedding angles of 0°, 30°, 45°, 60°, and 90° were selected for comparison with the results of the numerical simulation.

Figure 8 depicts the failure patterns in the specimens used for indoor tests. When the bedding inclination is 0°, the specimens exhibit continuous longitudinal cracks penetrating the bedding plane, accompanied by cracking or sliding phenomena along the bedding plane in the lower part. At a bedding inclination of 30°, the specimens show longitudinal cracks penetrating the bedding plane, without obvious cracks inclined along the bedding plane. For a bedding inclination of 45°, the specimens mainly contain cracks inclined along the bedding plane, accompanied by a small number of longitudinal cracks penetrating the bedding plane. When the bedding inclination is 60°, the specimens mainly exhibit cracks inclined along the bedding plane, without obvious longitudinal cracks penetrating the bedding plane. At a bedding inclination of 90°, the specimens have cracks along the longitudinal layers, accompanied by longitudinal cracks penetrating the bedding plane in the lower part.

Figure 9 shows a central longitudinal cross-sectional view of the numerically simulated sample, where the gray portion represents the rock matrix, the blue portion represents the bedding plane, and the red portion represents the microcracks generated during failure of the parallel bond model and smooth joint model. At values for the bedding inclination of the sample of 0° and 30°, the microcracks are mainly concentrated in the rock matrix, with only a small proportion in the bedding part, and they gather to form a failure zone that penetrates the bedding plane. This indicates that failure mainly occurs in the rock matrix, and that the failure mode is shear that penetrates the bedding plane. For values of the bedding inclination of 45° and 60°, the microcracks are almost entirely concentrated in the bedding part, indicating that failure mainly occurs in the rock bedding plane, and the failure mode for the rock is shear failure along the bedding. When the bedding inclination of the sample is at 90°, the microcracks are concentrated in the bedding plane, but there are also many cracks in the rock matrix. This is because the direction of loading is parallel to the direction of the bedding plane, and the bedding plane first undergoes tensile failure to form a fracture zone. Continued loading then leads to the gradual generation of microcracks in the rock matrix, thus creating splitting failure.

When the results of indoor experiments are compared with numerical simulations, it can be seen that the modes of failure are basically consistent. It is only in the indoor experiment with a bedding inclination of 0° that cracking and slippage occur along the bedding plane below the specimen, a finding that does not match the numerical simulation results. It can be inferred that this is due to the presence of uneven micro-cracks within the test specimen itself.

4. Numerical Analysis of Deformation in Slate Foundation Pits

4.1. Constitutive Model

The ubiquitous joint model introduced here is based on the Mohr-Coulomb model, in which joint planes are embedded to reflect the anisotropy of the material. The orientation and stress state of the joint surfaces can be represented by a local coordinate system, as illustrated in

Figure 10. The stress transformation relationship between generalized coordinates and local coordinates can be expressed by Equation (1), while the elastic stress and strain increments in local coordinates can be represented by Equation (2).

where

θ represents the inclination angle of the joint surface.

where

K represents the bulk modulus, and

G represents the shear modulus.

The joint surfaces in the model also adhere to the Mohr-Coulomb yield criterion. As illustrated in

Figure 11, the failure of joint surfaces includes both shear failure and tensile failure. Specifically, the envelope line AB representing shear failure is denoted as

fs = 0:

The tensile failure envelope BC is represented as

ft = 0:

where

,

,

and

represent the internal friction angle, cohesion, tensile strength, and normal stress applied to the joint surface, respectively, and τ denotes the shear stress.

4.2. Simulation of the Excavation Process for the Foundation Pit

Numerical modeling and support system design referenced relevant Chinese standards [

18,

19,

20], and these standards provide a basis for foundation pit excavation procedures, support arrangement, and monitoring plans.

The steps in the excavation process should be practical, and the simulated working conditions should be determined based on the actual situation. Solid elements were therefore used to simulate the construction of diaphragm walls, beam elements to simulate the erected reinforced concrete supports and steel supports, pile elements to simulate the construction of columns, and empty models to simulate the excavation of soil grid elements. The plane dimensions of the foundation pit are 18 m deep and 15 m wide. In accordance with the zoning of the influence on foundation pit engineering specified in China’s

Technical Code for Monitoring in Urban Rail Transit Engineering [

18], and considering factors such as the plane dimensions of the foundation pit, its spatial location, the impact of surrounding buildings on foundation pit excavation, and the influence range of ground settlement caused by foundation pit excavation, the influence area is determined as three times the excavation depth of the foundation pit. The boundary conditions of the foundation pit model were defined such that all five faces, except for the top surface, were constrained. Horizontal constraints were applied to the left and right sides, while the bottom surface was fixed.

Since the overall span of the foundation pit is large and the support system is uniformly composed of piles and internal bracing, Sections 86-16, 95-07, and 96-06 were selected for simulation analysis. The models were created using Midas GTS NX and imported into FLAC3D during the preprocessing stage, generating a hybrid mesh primarily consisting of hexahedral elements, supplemented by pentahedral and tetrahedral elements, to improve both computational accuracy and efficiency.

The project was divided into multiple steps based on the excavation conditions, with the excavation of each stratum and erection of support as a separate process. We consider Profile 86-16 as an example, with the excavation steps for other profiles being consistent with this profile.

Figure 12 illustrates the specific simulation process of excavation in the foundation pit model.

Step 1: Define the constitutive model of the soil layer, assign corresponding parameters, and perform initial geostress equilibrium under the effect of self-weight.

Step 2: Reset the displacement and velocity to zero, construct the diaphragm wall, and calculate the equilibrium.

Step 3: Reset the displacement and velocity to zero, install the column, and calculate the balance.

Step 4: Set up monitoring points for surface settlement and uplift within the foundation pit. Then, excavate the pit to the predetermined depth and apply the first layer of reinforced concrete support.

Step 5: Excavate the second layer of soil and apply the first steel support; continue in this manner until the excavation of the foundation pit is complete.

The mechanical properties and section parameters of the concrete and steel support components were determined according to Chinese standards [

21,

22].

The specific physico-mechanical parameters of each rock–soil layer in the foundation pit are shown in

Table 3.

The internal bracing structure, diaphragm wall, and columns adopt the linear elastic model, and the specific parameters are shown in

Table 4.

4.3. Analysis of Ground Subsidence

Figure 13,

Figure 14, and

Figure 15, respectively, show the displacement contour maps of surface settlement around the foundation pit under the inclination angle conditions of 30°, 45°, and 60°. On the right side of the contour maps are vertical displacement legends corresponding to each excavation stage, in units of meters. Ground surface uplift is defined as positive, while the ground surface settlement is negative. Surface settlement monitoring and deformation control standards refer to Chinese standards [

18].

During excavation of the foundation pit, unloading of the soil within the pit leads to settlement of the soil outside the pit. The maximum amount of settlement occurs near the diaphragm wall. As excavation progresses, the range of soil settlement extends outward continuously. When the excavation reaches the bottom of the pit, the overall surface soil exhibits a groove-like distribution pattern. By comparing the depth of vertical displacement of the strata and its deformation range in Sections 86-16, 95-07, and 96-06, it can be seen that as the depth and width of excavation of the foundation pit increase, the maximum displacement values of the bottom heave and the settlement around the pit continuously increase, and the range and depth of deformation are also constantly expanding. When the strata within the slate are inclined, significant asymmetric deformation occurs on both sides of the excavated foundation pit. The amount of settlement deformation and the range of deformation on the dip side are significantly greater than on the anti-dip side, and the uplift deformation range of the deep soil layer is noticeably shifted towards the dip side.

Using the results of

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15,

Figure 16 shows the surface settlement curves of the foundation pits in sections 86-16, 95-07, and 96-06 under different inclination conditions. The left figure shows the updip side (at monitoring points 16/07/06), while the right figure shows the downdip side (at monitoring points 86/95/96). Note that some settlement monitoring data for points 95 and 96 are missing. From these curves, it is evident that the surface settlement curve of the foundation pit is significantly influenced by the inclination of the rock stratum, as there is a notable difference in the ground settlement between the updip and downdip sides. Under different slate stratum inclination conditions, the maximum ground settlement on the downdip side occurs at a stratum inclination of 60°, with a maximum settlement of approximately 28.5–33.67 mm, occurring at a distance of about 14 m from the surface. The maximum settlements on the downdip side at inclinations of 30° and 45° are approximately 17.45–23.32 mm and 22.32–27.35 mm, respectively, occurring at distances of about 8–10 m and 10–12 m from the surface. By comparing the deformation of the foundation pit under the three inclinations, it can be observed that the maximum settlement at a slate inclination of 60° is significantly higher than for inclinations of 30° and 45°. Within the range 30–60°, the surface settlement on the downdip side is greater than on the updip side. In addition, as the slate inclination increases, the maximum values of the surface settlement on both sides of the foundation pit increase, and the settlement range gradually extends outward with an increase in inclination, indicating that the slate inclination has a certain degree of influence on the range of ground deformation caused by excavation of the foundation pit.

Through comparison, it was found that most of the monitored settlement values fell within the range of calculated settlement values for inclination angles of between 45° and 60°, a finding that is consistent with the actual working conditions. Except for the significant discrepancy between the calculated and measured data at the DBC-95 measurement point, the calculation errors for the measurement points were all within 3%. It is speculated that the reason for the large error at the DBC-95 measurement point is that the location of maximum settlement was not at the monitoring point, or that the influence of additional loads on the exterior of the foundation pit led to changes in settlement. Overall, the numerical simulation results for this foundation pit excavation closely reflect the settlement pattern of the surrounding ground surface, and some of the calculated data also accurately reflect the actual deformation situation. The calculation results are credible.

4.4. Analysis of Pile Displacement

To better compare the monitoring results with the calculation results under different inclination angles, data on both were taken after the completion of the last support, as shown in

Figure 17. The figure to the left represents the reverse inclination side, while that to the right represents the normal inclination side. According to

Figure 16, the variation in the displacement curves for the piles in the three profiles are relatively similar. The displacement of the retaining piles basically follows a bow-shaped distribution pattern, meaning that a large horizontal displacement occurs near the middle of the retaining piles. However, there are also certain differences in the displacement curves for the retaining piles under different conditions, which are related to the differences in the excavation depth of the foundation pit and the inclination of the rock strata.

The greater the excavation depth, the greater the amount of unloading of soil mass, and the more obvious the movement of the soil outside the pit towards the free face. Hence, the horizontal displacement of the pile increases accordingly. By comparing the curves in the figure, it can be seen that at the same inclination angle, the deformation of the piles on both the dipping and anti-dipping sides increases with excavation depth. Displacement towards the outside of the pit occurs near the top of the retaining piles on the anti-dipping side of Profile 86-16, with a displacement of about 0–5 mm. Meanwhile, a large horizontal displacement towards the inside of the pit occurs at the top of the retaining piles on the dipping side of this profile. The displacement of the pile ends on both sides of the foundation pit in Profiles 95-07 and 96-06 is larger than for Profile 86-16, indicating that the excavation depth has a certain degree of influence on the deformation of the pile ends.

At different inclinations, the deformation of the piles on both sides of Sections 86-16, 95-07, and 96-06 exhibits an asymmetric distribution. As the inclination of the slate strata increases, the overall horizontal displacement of the pile shafts on both the dip and anti-dip sides significantly increases. Based on the significant differences in the displacement vectors of the piles on both sides of the foundation pit at the various strata inclinations in the figure, it can be deduced that when the strata are inclined, the large deformation of the slope rock mass on the dip side causes an increase in the horizontal displacement of the retaining piles on that side, thus leading to an increase in the axial force on the first layer of the concrete internal support. This increased axial force effectively restricts the displacement of the piles on the anti-dip side of the foundation pit, resulting in significant differences in the deformation curves of the piles on both sides of the pit under inclined strata. As the inclination of the slate strata increases from 30° to 60°, the sliding trend towards the free face on the dip side increases, leading to an increase in the axial force transmitted from the pile to the internal support. At the same time, the axial force applied to the internal support has a greater impact on the horizontal displacement of the piles on the anti-dip side than the earth pressure of the soil outside the foundation pit on the piles. Hence, the end of the piles on the anti-dip side causes a horizontal displacement towards the outside of the pit, while the end of the piles on the dip side is displaced towards the inside of the foundation pit, and this displacement increases with the inclination over the range 30–60°.

As can be seen from the actual measurement results in

Figure 17, the deformation of the pile body on the updip side is greater than on the downdip side only for only Section 95-07. This may be due to the increased earth pressure on the outer soil of the retaining structure, caused by the surcharge and dynamic loads around the updip side of the foundation pit, leading to a larger lateral displacement of the retaining structure. Consequently, the supporting axial force increases, and the supporting force applied on the downdip side inhibits the deformation of the pile body. The deformation on the updip side is therefore larger compared to the updip sides of Sections 86-16 and 96-06, while the displacement value on the downdip side is smaller compared to the downdip sides of the other two profiles.

The simulated horizontal displacement patterns of the pile under various working conditions are largely consistent with the actual measured results, and the measured values for the pile displacement are generally within the range of the calculated values at 45–60°, a finding that is aligned with the actual situation. In terms of the change trend, as the excavation depth of the foundation pit increases, both the measured and simulated pile displacements increase, and the change for the pile in the vertical direction is also similar, confirming that the numerical simulations can reflect the actual deformation of the pile to a certain extent.

Numerical simulation results based on the experimental data indicate that the strength and elastic modulus of layered slate exhibit a distinct “U-shaped” variation with increasing bedding inclination. The mechanical properties are weakest at bedding angles of 45–60°, where both the foundation pit settlement and pile horizontal displacement reach their maximum values, suggesting that bedding inclinations of 45–60° represent the most unfavorable conditions for foundation pit stability.

4.5. Engineering Guidance and Applications

Numerical simulations based on experimental results indicate that the bedding inclination has a significant influence on both the mechanical anisotropy of slate and the deformation behavior of foundation pits. Therefore, in engineering design, the allowable deformation thresholds and support systems should be hierarchically controlled according to the bedding inclination to ensure construction safety.

When the bedding inclination ranges between 45° and 60°, sliding failure along the bedding planes becomes dominant, leading to a reduction in bottom resistance and a lower safety factor. Consequently, the dip side should be treated as the key control area, where measures such as denser support arrangements, increased pile stiffness, or enhanced axial forces in the internal bracing should be adopted. In contrast, for strata with nearly horizontal or vertical bedding, the deformation tends to be symmetric, and conventional support parameters are generally sufficient to meet safety requirements.

Regarding the scale effect, the bedding spacing in the numerical model was set to 12 mm, which is larger than the actual spacing of 0.7–4 mm. This simplification improves computational efficiency but may overlook local stress concentrations and microcrack initiation near the bedding planes, resulting in minor deviations from experimental observations. Nevertheless, the model successfully reproduces the “U-shaped” variation in strength and modulus, as well as the overall deformation trend. Future studies could employ multi-scale coupled modeling to refine the discrete representation of bedding planes and further enhance the accuracy of field deformation predictions.

5. Conclusions

This article has reported the results of uniaxial and triaxial compression experiments on weathered slate from the Proterozoic Banxi Group in Changsha City. The stress–strain curves, deformation failure modes, and anisotropic characteristics of mechanical parameters of the slate were analyzed for different water content states, bedding inclination angles, and confining pressures. The following conclusions can be drawn:

(1) Under uniaxial compression conditions, the compaction stage of microcracks in slate is not evident, and the subsequent stage of stable development of micro-elastic cracks is relatively short. After reaching the peak strength, the stress drops sharply, exhibiting the typical characteristics of brittle deformation. When confining pressure is applied, the compactness of the slate increases with increasing confining pressure, and the development of cracks under loading is restrained, resulting in a slower failure process. Macroscopically, the brittle characteristics are weakened while the plastic characteristics are enhanced.

(2) The failure mode of slate is closely related to the inclination of bedding. Samples at 0° are mostly subject to splitting shear failure across the bedding plane, whereas samples at 30° are mostly subject to shear failure across the matrix. Samples at 45° exhibit both failure along the bedding plane and local shear failure along the bedding plane, while samples at 60° are all subject to shear failure along the bedding plane. Samples at 90° are mostly subject to splitting tensile failure. The failure mode of slate often has a significant impact on its compressive strength.

(3) The values for the peak compressive strength and elastic modulus obtained from the numerical simulations both follow a U-shaped trend, which is consistent with experimental results. In terms of numerical values, the relative error between the simulated and measured peak compressive strength values is 15.57%, and the relative error between the simulated and measured elastic modulus values is 11.69%.

(4) The numerical simulation results for the failure modes are basically consistent with the experimental results, except for the specimen at an inclination angle of 0°, where there is a discrepancy between the experimental and numerical simulation results. It is speculated that this discrepancy is caused by the presence of uneven micro-cracks within the specimen itself.

(5) From the surface settlement curves for the three profiles of the foundation pit, it can be observed that the surface deformation is significantly influenced by the inclination angle of the slate strata, with notable differences in settlement between the dip and anti-dip sides. As the inclination angle increases, the settlement on both sides of the foundation pit also increases. Most of the monitored settlement values fall within the calculated range of settlement values under inclination angles ranging from 45° to 60°, a finding that is consistent with the actual working conditions.

(6) The simulated changes in the horizontal displacement of the pile body are basically consistent with the actual monitoring results. As the excavation depth of the foundation pit and the inclination angle of the rock stratum increase, both the measured and simulated displacements of the pile body show an increasing trend. Except for the measured deformation of the pile body on the reverse inclination side of Section 95-07, which is greater than that on the forward inclination side, the measured displacement of the pile body is greater on the forward inclination side than on the reverse inclination side, thus proving that the inclined slate stratum also has a significant impact on the deformation of the pile body.