1. Introduction

The rapid expansion of reinforced concrete structures in infrastructure necessitates the efficient evaluation of concrete quality using non-destructive testing (NDT) methods. These techniques, including the most classical known ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV) and rebound hardness (RH) tests, offer valuable insights into the structural integrity and mechanical properties of concrete without causing damage. However, the accuracy and reliability of these methods can be significantly influenced by environmental factors, particularly water saturation [

1,

2]. Although several studies have examined the influence of moisture on UPV or RH measurements, the combined and comparative effects of moisture on multiple NDT methods—and especially their interaction across different strength classes of concrete—remain insufficiently explored. This gap exists mainly because moisture in concrete is dynamic and unevenly distributed, making it difficult to quantify its impact through surface-only or single-parameter testing methods. Such variations can lead to misinterpretations regarding the actual compressive strength and durability of concrete.

In recent decades, extensive research by Carino and co-authors has laid the foundation for practical NDT applications in concrete assessment [

3]. Carino introduced the CAPO-TEST method for estimating in situ compressive strength of bridge concrete cores, providing a reliable mechanical index for strength correlation under field conditions and emphasized the importance of operator expertise and calibration consistency in achieving reliable results from NDT methods, an issue particularly relevant when interpreting moisture-affected data [

4]. The UPV method is widely used to assess concrete quality and detect internal defects [

5]. The presence of water in concrete pores influences ultrasonic wave propagation, often increasing wave velocity due to the higher density and lower compressibility of water compared to air. Studies suggest that wave velocity variations can reach significant levels, leading to misestimations of material strength and homogeneity [

6]. The RH method is related to the surface hardness and estimates compressive strength based on the rebound number of a hammer impact. However, moisture presence reduces surface hardness by increasing internal porosity and softening cement paste, leading to underestimated strength values [

7]. This phenomenon highlights the need for moisture corrections in RH-based assessments.

Popovics and Sajid have also advanced the understanding of ultrasonic-based testing. Air-coupled and non-contact ultrasonic systems capable of detecting internal flaws and microcracking in concrete without direct coupling have been developed [

8]. These innovations minimize surface preparation errors and enhance the detection of moisture-related anomalies [

8,

9].

To overcome these limitations and broaden the scope of NDT applications, recent research has focused on developing and adapting advanced testing techniques capable of evaluating both concrete and steel structures under varying environmental conditions. Recent developments also demonstrate the successful application of ultrasonic testing, acoustic emission, and piezoelectric dynamic strain monitoring methods for the evaluation of steel and composite structures. For instance, acoustic emission has been used to monitor the steel–concrete bond degradation during loading [

10], while piezoelectric dynamic strain responses have been effectively employed to assess damage extent in fractured steel beams [

11]. Among emerging approaches for concrete, the drilling resistance (DR) method shows particular promise due to its ability to provide localized, depth-resolved mechanical information. Recent advances in composite and hybrid concrete technologies further increase the demand for accurate non-destructive evaluation tools. For instance, hybrid steel–polypropylene fibre-reinforced concretes have been shown to improve strength, ductility, and crack resistance of structural elements [

12]. The combination of experimental testing and numerical simulation for such materials highlights the importance of correlating mechanical improvements with corresponding NDT indicators to ensure reliable performance assessment.

The drilling resistance (DR) measurement system is a non-destructive or minimally invasive testing technique that has gained prominence in assessing the mechanical properties of various materials. The DR measures the force required to drill into a material, which provides insights into its density, hardness, and degradation level [

13]. The DR method has been widely applied to the evaluation of timber and stone. The measured parameters are drilling speed, applied load, drill bit type, penetration depth and drill bit wear [

14,

15,

16]. Drilling allows for inspecting the degradation depth caused by insects in structural solid wood elements, particularly in heritage structures where invasive techniques are not suitable [

17]. DR provides a reliable estimate of mechanical resistance and internal defects, while it is sensitive to moisture content, which affects wood density. DR measurements can help determine weathering effects, porosity, and mechanical strength of different stone types [

18]. The resistance varies significantly between igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic rocks. Igneous rocks like granite exhibit high drilling resistance, whereas sedimentary stones like limestone and sandstone show greater variability due to porosity and grain size. The DR method allows differentiation between surface coatings and underlying stone; however, the drill-induced heat can affect the results in certain stone types [

16]. For the evaluation of plasters, DR is an essential method for evaluating their cohesion and durability. Drilling tests on plaster have been used to analyze layer adhesion, voids, and degradation caused by environmental exposure. However, due to plaster’s low hardness, drill penetration must be carefully controlled to avoid excessive damage [

19].

Recently, DR testing has also been introduced to the concrete industry as an emerging NDT method. However, only a limited number of studies have explored its adaptation for concrete testing, leaving its response to environmental factors such as moisture largely unquantified. Felicetti [

20] has evaluated the DR test for the assessment of fire-damaged concrete and concluded that the drilling resistance test is proven to be a rapid and practical method, even for in situ applications. The drilling resistance offers a fast drill rate (5–10 mm/s with a 6 to 10 mm diameter drill bit) applied with impact energy of 1.5 J. The electrical signals detected the motor rate and acceleration, the instantaneous total power consumption and the net drilling work per unit depth.

Unlike UPV and RH, DR offers in-depth profiling of the concrete structure, making it particularly useful for evaluating internal conditions unaffected by surface moisture variations [

1]. The method’s ability to provide more reliable insights into water-affected regions makes it a promising tool for structural assessment. Gunes et al. proposed the DR methodology as a means to predict the compressive strength of in situ concrete and concluded that, in combination with other NDT methods, DR gives the best accuracy of the results [

21]. Complementary studies by Carino and co-authors have further demonstrated that the precision of ultrasonic and rebound-based strength correlations depends strongly on calibration and operator training, with reported uncertainties of ±10–15% in predicted compressive strength when field calibration is inadequate [

4,

8]. Moreover, Carino and Popovics emphasized the need for multi-method validation to reduce this uncertainty, highlighting that no single NDT technique provides complete reliability without cross-verification using secondary approaches. Recent work on impulse response and resonance frequency methods supports this view, showing that these stiffness-based indices correlate well with structural damage extent (R

2 ≈ 0.80–0.90) but remain highly sensitive to boundary and moisture conditions [

8]. Together, these studies underline the importance of integrating complementary NDT techniques—such as UPV, RH, and DR—to obtain a more holistic and moisture-resilient evaluation of concrete performance [

4,

8].

This work provides the first systematic quantification of how moisture content simultaneously affects surface-based (UPV and RH) and depth-sensitive (DR) responses in concrete specimens of varying compressive strengths (C25/30 and C40/50 MPa). This comprehensive analysis provides a new understanding of how moisture influences the outcomes of both traditional and emerging NDT methods, thereby contributing to improved reliability in evaluating the condition of concrete structures exposed to moisture, such as marine and underground constructions.

2. Materials and Methods

The experimental concrete mixtures consisted of Portland cement (CEM I 42.5 N, Cemex Ltd., Riga, Latvia), water, quartz sand, and dolomite aggregate with a particle size range of 4–11.2 mm. Two different compositions were tested, as detailed in

Table 1. The primary difference between the mixtures lies in the water-to-cement (W/C) ratio, with mixture C1 including an additional 1.2 wt.% water-reducing admixture DYNAMON NRG 700 (Mapei Ltd., Riga, Latvia). Mixture C2 had a higher W/C ratio compared to C1 (0.67 and 0.80). These mixtures were used to prepare concrete specimens for mechanical testing, including RH tests and UPV measurements, ensuring a consistent material base for comparative analysis. The selected W/C ratios were chosen to represent two typical performance conditions in structural concrete: C1 as a dense, low-permeability mix typical of important structural applications, and C2 as a higher-porosity mix that is more sensitive to moisture ingress for traditional concrete applications.

In this study, cubic concrete specimens with dimensions of 150 × 150 × 150 mm3 were tested to evaluate the effects of moisture on concrete properties. To ensure reliable comparison between moisture conditions, three distinct states were established: dry, air-dry and water-saturated. For the saturated condition, the specimens were fully immersed in water until mass stabilization was achieved, defined as a change of less than 0.1% of total specimen mass over 24 h. This procedure ensured complete saturation of the open pore structure. For the dry condition, the same specimens were oven-dried at 80 °C until constant mass was reached, representing a moisture state typical of in-service dry concrete. After the tests, the concrete compressive strength was determined for cubical specimens. The testing age of concrete was 265 days.

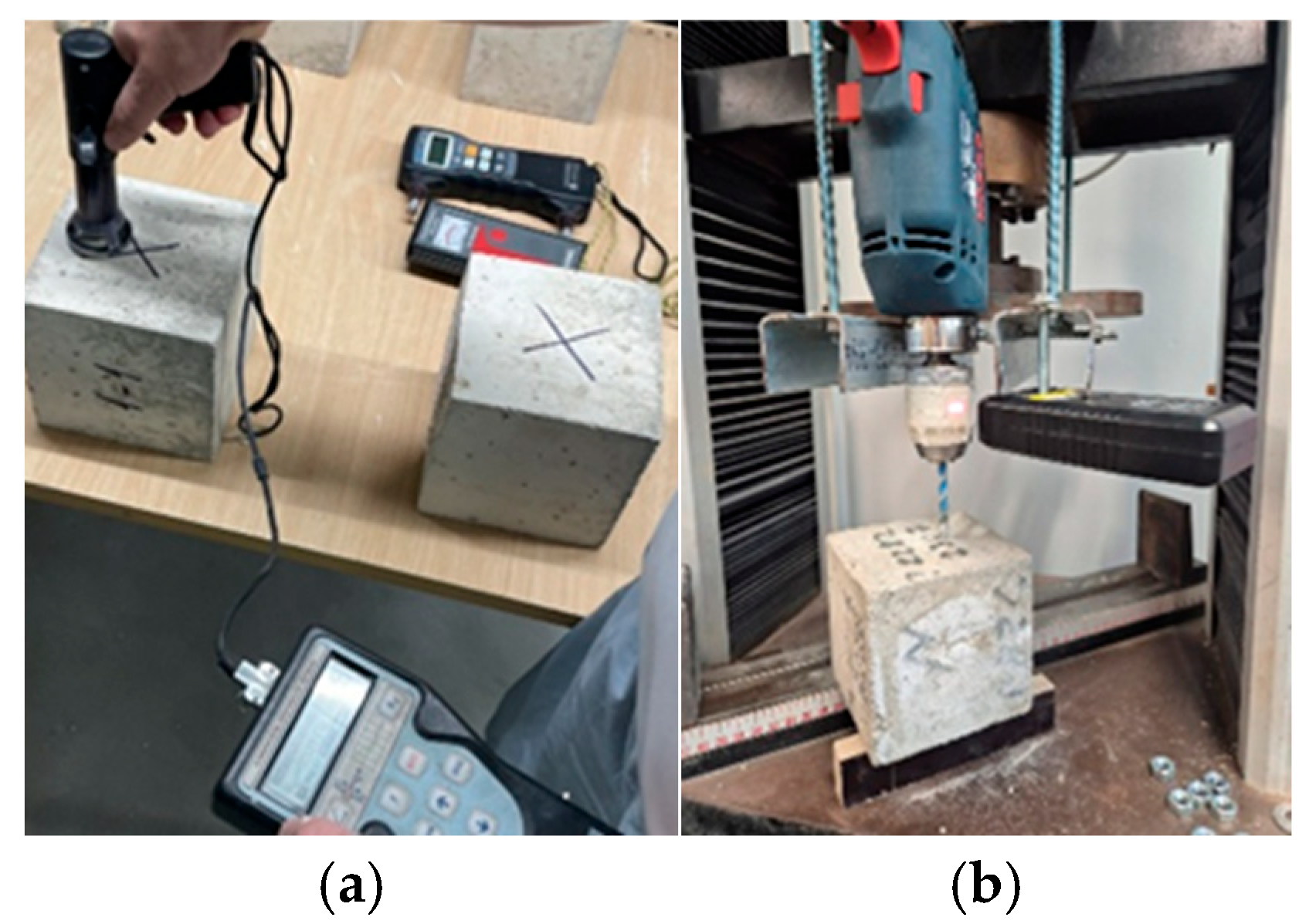

Concrete specimens for the experiments were selected considering the specifications of both the IPS MG4.03 rebound hammer (Stroypribor Ltd., Chelyabinsk, Russia) and the “UK-1401” ultrasonic tester (Stroypribor, Chelyabinsk, Russia) (

Figure 1a). To facilitate the interpretation of experimental results, the measurement locations were systematically arranged. For the “UK-1401” ultrasonic tester, the diagonal dimensions of the specimens were adequate to guarantee accurate UPV determination. All non-destructive tests were carried out in accordance with the relevant European standards. The UPV measurements were performed following EN 12504-4:2021 [

22]. The RH test was conducted according to EN 12504-2:2012 [

23]. Each test point was positioned at least 25 mm from specimen edges and previous impacts, and all measurements were performed on clean, smooth surfaces under controlled laboratory conditions (22 ± 2 °C, 60 ± 5% RH). Before each test, the surface and near-surface moisture (W,%) contents were quantified using “Tramex Concrete Moisture Encounter” device (manufacturer Global Test Supply, Wilmington, North Carolina, Wilmington), which operates on a non-destructive impedance principle and provides relative readings expressed as percentage moisture content (MC). To validate surface readings, gravimetric moisture content (wt.%) was calculated using the saturated and oven-dried masses, respectively.

A drilling device setup was created to determine the DR of the concrete (

Figure 1b). A “Bosch GSB 13 RE” drilling machine (Bosch Ltd., Gerlingen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany) was fixed in a universal testing machine (Zwick 100, ULM, Germany). Additionally, a metal frame with threaded rods and clamps was used to stabilize the drill, ensuring precise alignment and vertical penetration into the concrete surface. The starting drilling speed was 1800 RPM. A 6 mm-diameter tungsten carbide concrete drill bit “Bosch CYL-9” was used. The drill movement speed was constant—20 mm/min. The rotational speed was measured with an “Extech RPM250W Laser Tachometer” (manufacturer Extech, China, Nashua, New Hampshire) with data recording capabilities. The “PZEM-016 Energy Tester” (Ningbo Peacefair Electronic Technology Co., Ltd, Zhejiang, China) with “Modbus” communication protocol (version 8.2.2) was used to monitor and record power consumption during drilling. em7545 ac/dc communication box V.1.6.0.0 software was used. The initial power consumption of the drilling machine was 80 W. Not more than six drills were made for each drill bit. At least three drills were performed in each concrete specimen, and two parallel concrete specimens were tested.

3. Results and Discussion

- A.

Concrete properties

The physical and mechanical properties of the tested concrete compositions are presented in

Table 2. Results demonstrate the influence of different water-to-cement ratios (W/C) on the physical and mechanical properties of the concrete mixtures. Density and compressive strength for the concrete mix with a lower W/C ratio (C1) exhibited a higher density of 2241 kg/m

3, whereas the higher W/C ratio in C2 resulted in a lower density of 2163 kg/m

3. This reduction in density suggests a higher porosity in C2 due to the increased water content. A higher W/C ratio promotes the formation of larger and more connected capillary pores during cement hydration, which weakens the overall microstructure and facilitates moisture ingress. As the excess mixing water evaporates, voids remain within the hardened matrix, increasing permeability and reducing mechanical strength [

24,

25].

Previous microstructural investigations using mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) have demonstrated that concretes with W/C > 0.6 exhibit a significant increase in total pore volume and average pore diameter, which directly correlates with reduced compressive strength and durability [

26]. These effects explain the higher water absorption and lower density observed in C2 concrete in this study. Similarly, the compressive strength followed a decreasing trend with an increasing W/C ratio, with C1 achieving 53.2 MPa, which is 44.6% higher than the 36.8 MPa of C2. This significant reduction in strength is attributed to increased capillary porosity in C2, which weakens the overall microstructure.

C1 exhibited a slightly higher surface MC of 4.1%, compared to 3.9% in C2. However, the water absorption capacity was substantially different. C1 absorbed 5.72 wt.% of water, whereas C2 absorbed 7.28 wt.%, indicating higher permeability in the high W/C mixture. The increased water absorption in C2 is consistent with its lower density and higher porosity, making it more susceptible to moisture ingress. The air-dry weight percentage also varied slightly, with C1 at 2.08 wt.% and C2 at 2.25 wt.%.

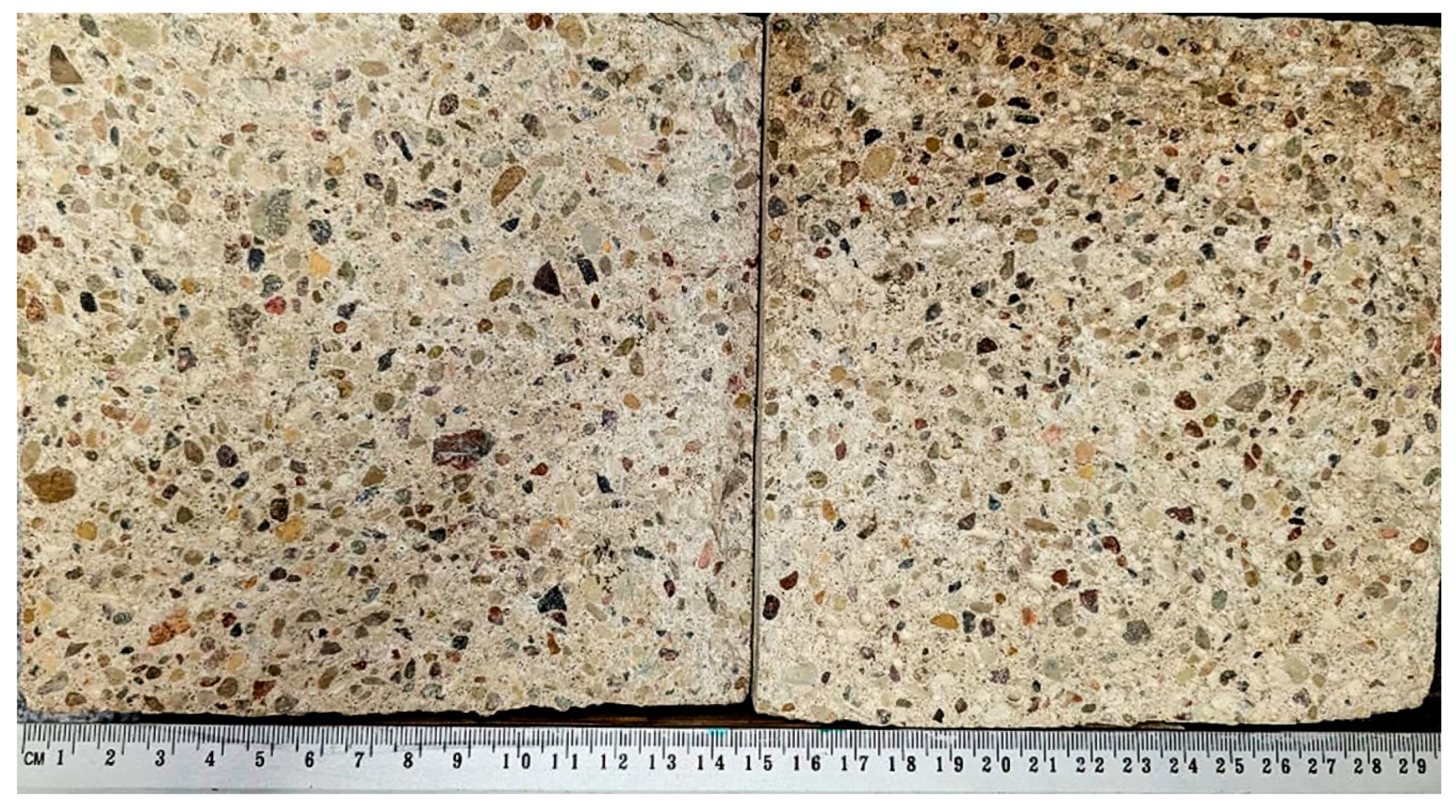

The visual comparison of the two concrete specimens reveals significant structural differences influenced by their respective W/C ratios (

Figure 2). C1 (left), with a lower W/C ratio, exhibits a denser and more compact surface with fewer visible pores and better aggregate bonding, aligning with its higher compressive strength (53.2 MPa) and lower water absorption (5.75 wt.%). In contrast, C2 (right), with a higher W/C ratio (0.80) and no superplasticizer, has a more porous and rougher texture, with small visible voids, signifying increased capillary porosity and weaker cement bonding. This structure correlates with lower compressive strength (36.8 MPa) and higher water absorption (7.28 wt.%), suggesting lower density and greater permeability.

- B.

Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity

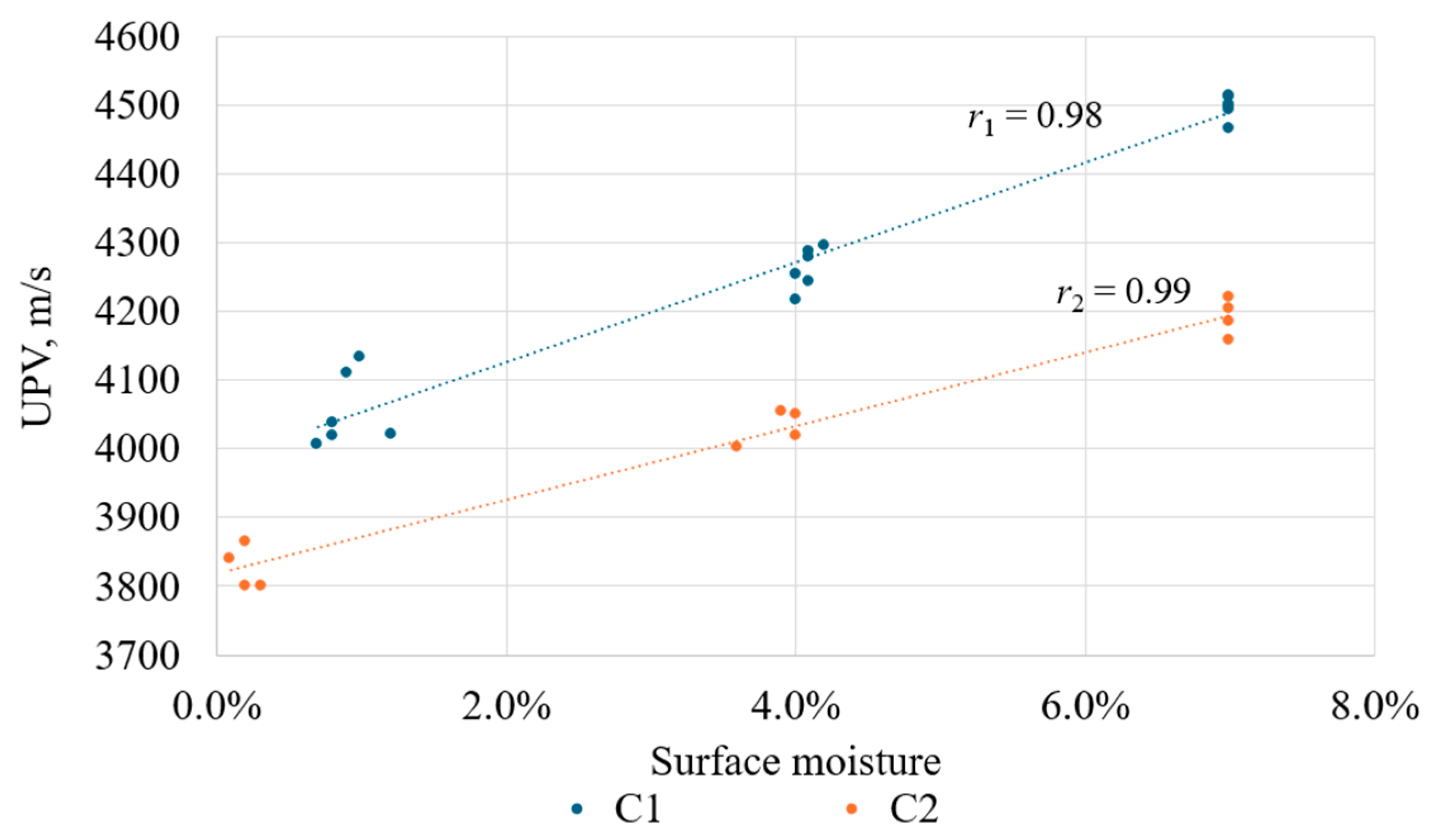

The Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity (UPV) test was carried out to evaluate the internal structure and compactness of the concrete compositions with different W/C ratios and moisture conditions. The results given in

Figure 3 indicate a strong correlation between surface MC and UPV values, with an observed correlation coefficient

r1 = 0.98 and

r2 = 0.99 for C1 and C2, respectively, signifying a high degree of linear dependence. The UPV measurements reveal two distinct trends: (i) C1 exhibits higher UPV values, reaching up to 4400 m/s at 6.0% surface moisture. (ii) C2 demonstrates consistently lower UPV values, with maximum values around 4150 m/s under the same moisture conditions. These findings indicate that C1 has a denser microstructure, likely due to its lower interfacial transition zone (ITZ) porosity and reduced capillary voids, resulting from the optimized water-cement ratio and the use of a superplasticizer in comparison to mixture C2.

A notable increase in UPV with rising surface MC was observed for both compositions. This trend is expected, as moisture within the pores enhances wave propagation velocity, leading to higher UPV readings. However, despite this increase, the relative difference between the two compositions remains consistent. At the highest surface moisture level (~7%), the observed divergence in UPV between the two mixtures warrants specific comment. First, the MC reading reflects near-surface moisture, whereas UPV averages conditions along the full acoustic path; thus, a similar surface moisture (≈7%) can coexist with different internal saturation states between C1 and C2 due to their distinct pore structures and connectivity. Wet surfaces are more prone to coupling variability (thin water films, gel squeeze-out, and contact pressure), which can alter the effective travel time by microseconds, translating into noticeable velocity differences over short path lengths.

The strong correlation (r1 = 0.98) suggests that surface moisture plays a significant role in UPV measurements and should be considered when interpreting results. The lower UPV in C2 aligns with its higher water absorption and lower compressive strength, indicating a weaker and more permeable matrix. In contrast, C1, with its lower absorption and higher strength, exhibits superior compactness, leading to higher UPV values. The results highlight that UPV is sensitive not only to moisture content but also to the underlying pore architecture and ITZ quality shaped by the W/C ratio. Therefore, the higher UPV in C1 provides a non-destructive indicator of its superior mechanical performance and microstructural integrity, supporting the strength trends obtained from destructive testing.

- C.

Rebound hardness test

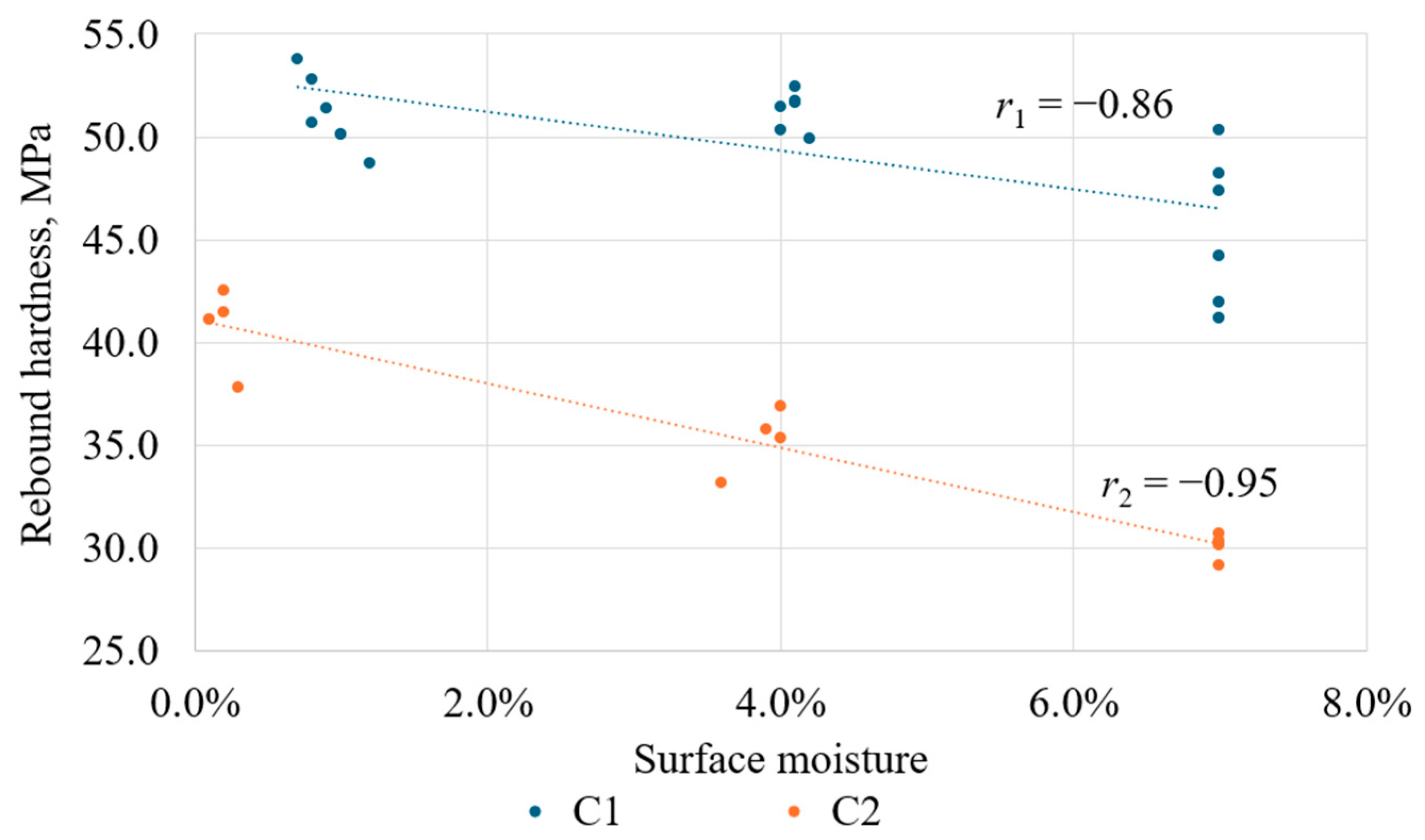

The rebound hardness (RH) test was carried out to assess the surface hardness and estimated compressive strength of the concrete specimens with different W/C ratios. The results, shown in

Figure 4, indicate a negative correlation between surface MC and RH values, with a correlation coefficient of

r1 = −0.86, demonstrating a high inverse relationship. The effect of W/C ratio on RH results exhibits two distinct trends: (i) C1 consistently shows higher rebound values, reaching up to 50 MPa under dry conditions and gradually decreasing with increasing MC. C2 shows a lower RH, with initial values around 40 MPa, which further declines with increasing MC. This reduction in rebound values aligns with the previous findings: C1, having a lower W/C ratio, higher density, and lower porosity, achieves higher surface hardness and compressive strength. Conversely, C2, with higher W/C and increased porosity, results in a weaker matrix, leading to lower rebound values.

A clear decreasing trend in RH values with increasing surface moisture is observed for both compositions. This effect is quantified by the coefficient of correlation (

r2 = −0.95) for C2, indicating a strong statistical relationship. The decrease in RH values with moisture increase is expected, as higher MC reduces surface stiffness, leading to lower rebound readings. Moisture affects RH primarily by softening the surface layer of concrete. When pores are filled with water, the cement paste becomes less rigid because adsorbed water molecules weaken the van der Waals bonds between calcium–silicate–hydrate (C–S–H) gel layers and increase their interlayer spacing. This local plasticization lowers the surface modulus and allows greater indentation under impact. Additionally, the presence of moisture facilitates energy dissipation through viscous damping and micro-slip at the aggregate–paste interface, which decreases the amount of elastic energy returned to the rebound hammer plunger. Consequently, the impact energy is more effectively absorbed rather than reflected, resulting in smaller rebound distances and, therefore, lower RH readings [

27,

28,

29]. At 0% surface moisture, C1 exhibits higher rebound hardness values (~52.5 MPa), while C2 shows ~40 MPa. As surface MC increases to 7.0%, both compositions show a significant decline, with C1 dropping to ~45 MPa and C2 to ~30 MPa. This suggests that wet surface conditions can lead to underestimated compressive strength values when using the RH test, reinforcing the need to consider moisture correction factors in field applications.

- D.

Drilling resistance

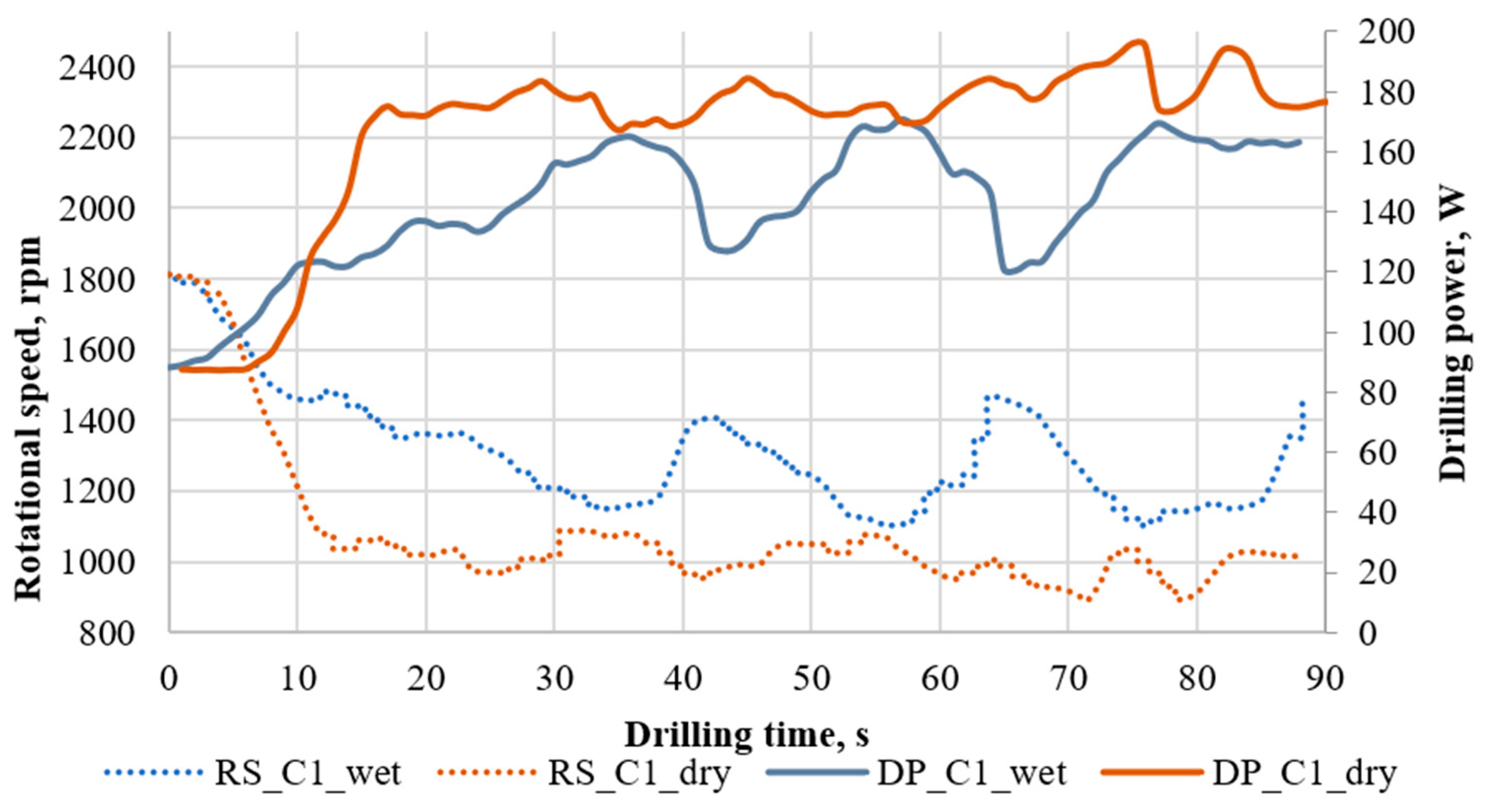

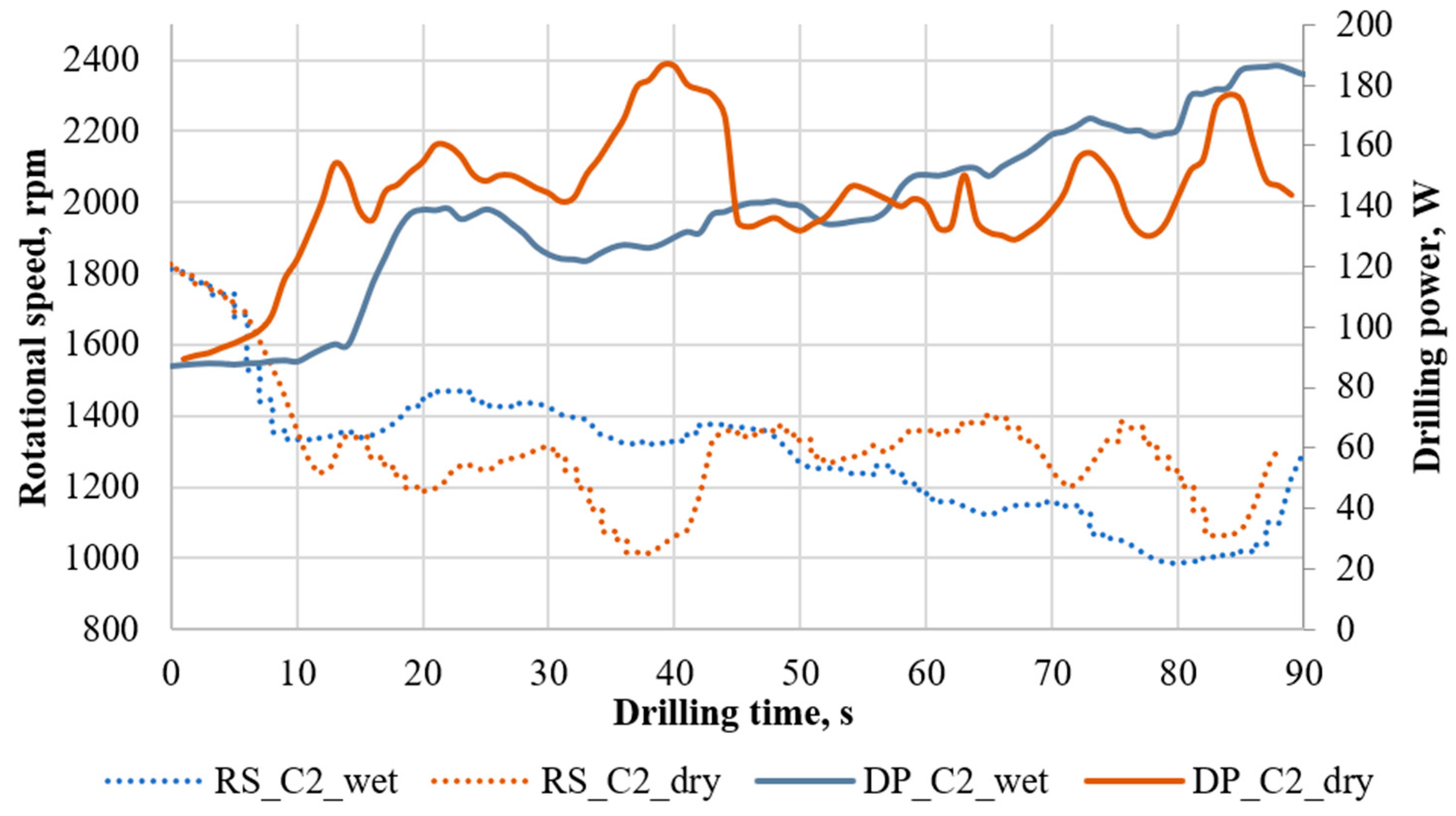

Comparing the drilling performance between the stronger C1 concrete and the weaker C2 concrete, distinct differences in resistance and drilling behavior are evident (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). In the C2 concrete, both wet and dry conditions exhibit lower drilling power compared to C1, indicating a reduced resistance to penetration. The drilling power for dry C2 concrete fluctuates similarly to that of C1 but remains at a lower magnitude, suggesting that the material is less dense and offers less resistance to drilling forces. Additionally, the rotational speed in C2 concrete remains relatively higher than in C1, especially in dry conditions, implying that the drill encounters less mechanical resistance.

These distinctions are directly related to the intrinsic mechanical properties of the two concretes. The lower W/C ratio in C1 produces a denser cement matrix with fewer interconnected pores and a stronger ITZ between the paste and aggregates. This compact microstructure increases local hardness and compressive strength, which in turn elevates DR and lowers the rotational speed of the drill due to higher opposing torque. Conversely, the higher W/C ratio in C2 results in greater capillary porosity and weaker aggregate bonding, allowing the drill to penetrate more easily and maintain higher rotational velocity with reduced power demand. These findings confirm that the measured drilling parameters (power, torque, and speed) effectively capture variations in material stiffness and cohesion between the two concrete grades.

The fluctuations in drilling power and rotational speed in C2 also appear to be more pronounced, particularly in the wet condition, which may be attributed to the lower compressive strength and weaker aggregate bonding of C2 concrete. This suggests that the drill transitions between different material phases more abruptly due to a less cohesive internal structure. MC has a pronounced effect on the DR response of concrete, as it alters both the material’s microstructural stiffness and the frictional interaction between the drill bit and the concrete matrix. When concrete is saturated, the presence of free water within capillary pores and microcracks reduces interparticle friction and weakens the cement paste–aggregate interface. This results in a lubricating effect at the cutting zone, lowering the drilling power and torque required for penetration.

Aggregates play a crucial role in concrete’s DR. In the presented results, the variations in rotational speed and drilling power suggest that aggregate distribution, size, and hardness significantly influence drilling performance. In dry concrete, the consistently high drilling power and relatively stable rotational speed indicate a more uniform and dense material structure, which is characteristic of well-distributed, rigid aggregates. The resistance remains steady, implying that the drill encounters a homogeneous mixture of cement paste and aggregates, which provides consistent opposition to penetration. Conversely, in wet concrete, the observed fluctuations in drilling power and a gradual decrease in rotational speed suggest that aggregates might be less bonded due to moisture presence. This could lead to localized variations in resistance as the drill transitions between cement paste and aggregate particles.

- E.

Statistical analysis of the results

The statistical analysis of drilling rotational speed provides insights into the variability and consistency of drilling performance across different concrete strength classes and moisture conditions (

Table 3). In both air-dry and wet conditions, the weaker C25/30 concrete exhibits a higher average rotational speed compared to the stronger C40/50 concrete, indicating reduced drilling resistance in the lower-strength material. The minimum rotational speeds show a noticeable difference, with C40/50 concrete having lower minimum values (929 rpm in air-dry and 1065 rpm in wet conditions) compared to C25/30 (1091 rpm and 1145 rpm, respectively). This indicates that the stronger concrete develops short intervals of increased torsional resistance, causing the drill to decelerate more markedly than in weaker concrete. The standard deviation is higher in C40/50 concrete (183 rpm in air-dry and 181 rpm in wet) compared to C25/30 (146 rpm and 139 rpm), indicating greater fluctuations in rotational speed, likely due to the heterogeneous structure. The coefficient of variation follows a similar trend, where C40/50 has a higher variability (15% air-dry, 14% wet) compared to C25/30 (11% air-dry, 10% wet), suggesting that drilling in stronger concrete results in more inconsistent resistance, possibly due to harder and more resistant aggregate inclusions. These statistical results highlight that the variability in rotational speed is directly linked to the heterogeneity of the concrete microstructure. In the denser C40/50 concrete, the drill alternately encounters aggregates, dense paste regions, and the interfacial transition zones (ITZ), each having different stiffness and resistance to penetration. This microstructural diversity causes intermittent fluctuations in torque and speed as the drill bit transitions between hard and soft phases. In contrast, the higher porosity and weaker bonding in C25/30 produce a more uniform response with smaller deviations in rotational speed. Therefore, the observed standard deviation and coefficient of variation can be interpreted as indirect indicators of material heterogeneity—higher variability corresponds to more complex internal structure and stronger aggregate–paste interactions. Moisture further influences this variability: under wet conditions, the presence of water partially homogenizes the material by softening the cement paste and reducing the friction contrast between aggregates and matrix, thereby slightly lowering the variation in rotational speed. These statistical trends confirm that weaker concrete allows for smoother and faster drilling, while higher-strength concrete presents more resistance and variability in drilling speed, likely due to its denser composition and stronger aggregate bonding.

The average drilling power is consistently higher in C1 concrete compared to C2, confirming that higher-strength concrete requires more energy for penetration (

Table 4). In air-dry conditions, the average power is 154 W for C1 and 139 W for C2, while in wet conditions, it decreases to 142 W and 130 W, respectively. This suggests that moisture reduces drilling resistance in both concrete types but has a more pronounced effect on the stronger concrete. The maximum power values follow a similar trend, with the highest recorded power in air-dry C1 concrete (208 W), indicating peak resistance, whereas the maximum power in wet C1 drops to 173 W, reinforcing the role of moisture in reducing strength. The minimum power values, however, remain nearly identical across all conditions, around 87 W, suggesting that during moments of least resistance, the effect of concrete strength is negligible. The standard deviation is slightly higher in C1 concrete, reflecting greater fluctuations in drilling power, likely due to its denser and more heterogeneous structure. Notably, the coefficient of variation remains at 16% for most conditions but increases to 21% in wet C2, indicating that the weakest, wettest concrete exhibits the highest inconsistency in power consumption, possibly due to variations in material composition and moisture distribution. The variability in drilling power further supports the interpretation of heterogeneity effects observed in rotational speed. In C40/50 concrete, power fluctuations are influenced by the uneven distribution and hardness of coarse aggregates, which locally increase the cutting resistance and energy demand. The relatively stable power pattern in C25/30 reflects a softer, more homogeneous matrix with less aggregate interlock. Under wet conditions, the reduction in standard deviation and coefficient of variation demonstrates that moisture partially evens out these mechanical contrasts, as the lubricating effect of water lowers friction and minimizes the energy spikes associated with hard inclusions. Therefore, statistical analysis of both rotational speed and power provides not only a measure of drilling stability but also an indirect assessment of the internal uniformity and compactness of the concrete.

The comparative analysis of drilling rotational speed and power consumption highlights the impact of concrete strength and moisture conditions on drilling performance (

Table 5). The rotational speed in wet concrete decreases within a range of −3% to −7%. By comparing rotational speed between C1 and C2 in both air-dry and wet conditions, the most significant difference (−13%) has been obtained in air-dry conditions, however, in wet concrete this difference drops to −9%, reinforcing the effect of moisture in lowering DR. Conversely, drilling power consumption increases in all comparisons, ranging from +7% to +9%, confirming that greater resistance requires more energy for penetration. The power increase for C1 and C2 concrete is 6% to 7%. This indicates that stronger concrete demands significantly more power than in dry conditions, and it is very close to the amount of change in rotational speed. Similarly, stronger C1 concrete requires more energy than C2 in a range of 8% to 9%.

4. Conclusions

The study confirms that a lower water-to-cement (W/C) ratio enhances the mechanical strength, density, and moisture resistance of concrete. The UPV results verified that lower W/C concrete exhibits higher wave velocity and structural integrity, while RH tests showed a strong inverse trend between moisture content and rebound values, emphasizing the need for moisture correction in strength estimation.

C25/30 concrete demonstrated lower and less stable drilling resistance than the denser C40/50 concrete. The stronger mix (C40/50) required higher drilling power and showed reduced rotational speed, indicating greater mechanical stiffness and internal cohesion. However, the effect of moisture on drilling resistance was comparatively minor, confirming that the DR method is less sensitive to water saturation and primarily reflects intrinsic mechanical compactness rather than transient moisture conditions.

These findings underline that moisture substantially affects UPV and RH responses but only relatively influences DR behavior. Therefore, combining these techniques provides a more reliable evaluation framework: UPV and RH are effective for detecting surface and near-surface changes related to moisture, while DR offers depth-sensitive insights into internal density and aggregate bonding.

Findings highlight the significant influence of moisture on concrete properties, affecting its hardness, resistance, and drillability. The higher power demand and more stable resistance in dry concrete suggest stronger internal bonding and denser material structure, whereas the variations in wet concrete reflect the impact of moisture in altering its mechanical response. The role of aggregates in DR is evident in the measured parameters, where their distribution and bonding within the concrete matrix significantly impact the ease or difficulty of penetration.

The presented NDT methods are effective for a non-destructive evaluation of material properties, making it particularly useful for assessing structural integrity and material uniformity, while testing conditions can lead to a misleading evaluation.