1. Introduction

Robotic manipulators are increasingly deployed in constrained industrial environments such as assembly lines and warehouses, where efficient multi-target operation is critical. Research on layout optimization, motion planning, surrogate-assisted motion planning, and posture optimization techniques for manipulator robots in industrial settings has emerged as a critical area due to increasing demands for automation, precision, and efficiency in manufacturing processes [

1,

2]. Over the past decade, advancements in evolutionary computation, genetic algorithms, and multi-objective optimization have significantly enhanced the capabilities of industrial manipulators, enabling improved trajectory planning, workspace layout, and task execution [

3,

4]. Early research demonstrated the effective application of metaheuristics like genetic algorithms and Particle Swarm Optimization for energy-efficient robot configuration and motion planning, establishing a foundation for subsequent work in this domain [

5]. The practical significance of these developments is increasing by the growing adoption of robotic systems in diverse sectors, where optimized manipulator configurations can reduce cycle times, energy consumption, and operational costs, thereby contributing to sustainable manufacturing [

6,

7]. For instance, energy savings of up to 20% have been reported through optimized robot placement and motion planning [

7,

8].

Despite these advances, the problem of simultaneously optimizing manipulator layout, motion trajectories, and posture remains complex due to the high dimensionality of configuration spaces, nonlinear constraints, and the needs to balance multiple conflicting objectives such as manipulability, stiffness, and collision avoidance [

9,

10,

11]. Existing literature reveals a knowledge gap in integrated approaches that address layout design and motion planning concurrently while incorporating surrogate models to reduce computational costs [

3,

12,

13]. Moreover, some studies favoring evolutionary algorithms and others using hybrid algorithms or surrogate-assisted methods have been addressed [

1,

14]. The limited real-world validations hinder the deployment of robust, generalizable solutions, potentially leading to suboptimal robot performance and increased downtime [

15,

16].

Conceptually, layout optimization involves determining the spatial arrangement of robots and workpieces to maximize accessibility and minimize operation time [

17,

18]. Motion planning focuses on generating collision-free, time-efficient trajectories within the robot’s workspace [

10,

19], while posture optimization aims to enhance robot stiffness and accuracy by selecting favorable joint configurations [

20,

21]. These concepts are interrelated as layout influences feasible motion paths, and posture affects both manipulability and task precision. The integration of these elements forms the foundation for developing comprehensive optimization frameworks tailored to industrial manipulators [

4,

22].

Co-optimizing workspace layout, motion planning, and robot posture presents several challenges. The interdependencies between robot placement, motion planning, and posture optimization result in a high-dimensional design space, complicating the optimization process. Simultaneously considering multiple objectives and constraints increases the computational complexity, necessitating efficient algorithms to achieve real-time performance. Robots often operate in dynamic settings with varying obstacles and task requirements, requiring adaptive planning strategies that can handle uncertainties and changes in the environment [

23]. Integrating diverse optimization techniques, such as genetic algorithms for robot placement and posture optimization, and surrogate-assisted RRT for motion planning, poses challenges in ensuring consistency and convergence across the optimization stages.

Recent studies have attempted to address these challenges. For instance, Lu et al. [

24] introduced a distributed co-design framework for motor and motion optimization in robotic manipulators, aiming to reduce computational load while enhancing scalability. Additionally, surrogate-assisted motion planning techniques have been explored to alleviate the computational burden in complex environments [

25]. However, a comprehensive approach that integrates layout, motion, and posture optimization remains underexplored.

This paper introduces a holistic optimization framework that concurrently addresses the robotic cell layout, motion planning, and manipulator posture where each problem traditionally has been solved individually. The principal contribution is a novel hierarchical methodology where the output of each stage defines the constraints and objectives for the next, all governed by a unified objective function minimizing total task completion time. In contrast to conventional methods that optimize these elements separately, the proposed method can obtain global optimal solutions. The key contributions are

Developing a genetic algorithm to optimize the placement of robot and two workpiece holders within a workspace, considering obstacle avoidance, reachability to targets, and task efficiency.

Employing a surrogate-assisted rapidly-exploring random tree (SA-RRT) algorithm that integrates a trained surrogate model to guide the sampling and tree expansion process, enabling the generation of collision-free paths between pick-and-place targets with significantly reduced computational effort compared to conventional RRT-based planners.

Utilizing a secondary genetic algorithm to determine an optimal robot posture that ensures quick access to multiple targets.

The efficacy of the proposed approach is validated through direct comparison with conventional decoupled methods such as RRT, TNN-RRT, and state-of-the-art sampling-based planners like SA-RRT, demonstrating significant improvements in overall system performance.

The novelty of this research lies in the development of a unified hierarchical optimization framework that concurrently addresses workspace layout, motion planning, and posture optimization problems typically solved in isolation for robotic manipulators. By incorporating surrogate-assisted optimization into the motion planning stage, the proposed framework significantly reduces the computational burden in the optimization process. This approach reduces the total cycle time for multi-target tasks by approximately and decreases computational planning time by over compared to TNN-RRT and established sampling-based planners like SA-RRT. This work advances the field by providing a systematic methodology that enhances task efficiency, reduces cycle times, and ensures safe human–robot interactions.

The remaining part of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews related works.

Section 3 provides the problem description and mathematical formulation.

Section 4 details the proposed framework and algorithms,

Section 5 presents the experimental results,

Section 6 discusses industrial implications with future works, and

Section 7 concludes this paper.

4. Methodology

4.1. Hierarchical Optimization Overview

The proposed optimization framework is structured as a three-stage hierarchical pipeline, as illustrated in

Figure 2. Unlike a purely sequential approach, which executes optimization stages in order without interdependence, a hierarchical structure establishes logical dependencies between higher and lower levels. In addition,

Figure 2 implicitly summarizes the distribution of computational load across the three stages since each block corresponds to a distinct optimization or planning process. Each stage solves a sub-problem with distinct objectives and constraints, and its feasible solution becomes the input to the next stage. Specifically, (i) the layout optimization stage determines feasible and collision-free placements of the robot and workpiece holders, (ii) the motion planning stage computes collision-free trajectories based on that feasible layout, and (iii) the posture optimization stage refines the robot configuration to minimize cycle time while respecting joint and reachability constraints. Through this hierarchical dependency, the feasibility of lower-level stages is inherently ensured as their inputs are derived from already validated and reachable configurations obtained from the preceding stages.

A hierarchical strategy is particularly essential because solving layout, motion, and posture optimization simultaneously would create a high-dimensional, non-convex search space that is computationally intractable. A combined formulation would need to optimize robot base positions, workpiece holder placements, thousands of candidate joint trajectories, and redundant postures within a single optimization space, making convergence slow and often infeasible. By decomposing the problem hierarchically, each stage effectively reduces the dimensionality of the search, filters out infeasible solutions early, and enforces feasibility constraints for the subsequent stages. This structured decomposition improves computational efficiency and ensures that the final solution remains both kinematically feasible and operationally optimal.

At the first stage of the layout optimization, the objective is to determine the collision-free placements of the robot and two workpiece holders in the discretized workspace, and compliance with the robot’s maximum reach of . These positions serve as input for determining the target positions in the workspace and subsequent motion planning.

The second stage, motion planning, generates collision-free paths between the pick-and-place targets using a sampling-based rapidly-exploring random tree (RRT) planner. The RRT incrementally expands the search space by adding only collision-free nodes, and once a target is reached, the corresponding robot posture is recorded. If RRT fails to find a feasible path due to consecutive collisions with the obstacles present in the environment, resampling is performed by doubling the step size of the planning algorithm. This stage ensures that the robot arm can move safely and feasibly between all task-relevant positions.

Finally, in the third stage, posture optimization, the pick and place postures obtained from the RRT planner are refined using a secondary genetic algorithm (GA). The aim is to optimize a single joint configuration such that the robot minimizes its total execution time by reducing joint travel distance and ensuring smooth transitions between targets. Additionally, candidate postures are constrained to remain collision-free, within joint limits, and away from kinematic singularities, guaranteeing both safety and efficiency during task execution.

4.2. Search Space Modeling for Placement Planning

The search space for the robot and workpiece holders consists of

cells along the

X and

Z axes, with cell size

s and origin

. The center position of a cell is indexed by Equation (

11).

Each cell is assigned to one of three categories as follows:

where

and

represent the union of all obstacle regions such as racks, walls, or other machinery equipment and conveyor regions in the environment, respectively. Thus the total set of workspace cell is defined by Equation (

13), where

,

, and

represent the set of free cells, conveyor cells, and obstacle cells, respectively.

However, only the set of free cells is considered as candidates for layout optimization of the robot and workpiece holders.

4.3. Layout Optimization

The genetic algorithm with adaptive termination for layout optimization is provided in Algorithm 1. Here the term

adaptive refers specifically to a termination mechanism, rather than an adaptive variation of GA operators. In particular, neither mutation or crossover rates nor population size are adapted during execution. Instead, the GA terminates early when the global best cost does not improve for a predefined number of consecutive generations (stall limit

). This adaptive stall-based stopping criterion prevents unnecessary evaluations once convergence behavior is detected, thereby reducing computational cost without modifying any genetic operator parameters. The population sampling, fitness evaluation, and GA operators are described in detail in the following subsections.

| Algorithm 1: Genetic algorithm with adaptive termination |

![Applsci 15 11941 i001 Applsci 15 11941 i001]() |

4.3.1. Population Sampling

In the layout optimization problem, each individual or candidate solution

represents the positions of the robot and the two workpiece holders. The initialization step generates a set of such candidate layouts to form the first generation of the genetic algorithm. The sampling rule is defined by Equation (

14), where

denotes the placement position of entity

e, and

E is the set of all entities to be placed.

This means that for each entity (robot or workpiece holders), a cell is randomly selected with equal probability from the set of free cells

. Formally, it can be represented by Equation (

15). Thus, every free cell has the same chance of being assigned as the initial position of a robot or workpiece holder.

To ensure physical feasibility, the sampled positions must satisfy the non-overlapping constraint provided in Equation (

16). That is, no two entities can occupy the same cell. If a sampled position conflicts with an already assigned one, resampling is performed until a valid position is obtained.

4.3.2. Cost Function

The cost of the candidate solutions is computed by Equation (

17), where

are distances, and

is the sum of the total penalty. Lower values of

indicate better layouts, and the genetic algorithm is configured to minimize

over successive generations.

The three euclidean distances

are calculated using Equation (

18), where

is the distance between the robot and the first workpiece holder,

is the distance between the robot and the second workpiece holder, and

is the distance between the robot and the conveyor belt.

The total penalty

in (

17) is the sum of the two penalties. If two objects are too close

, a fixed overlap penalty is added. If a workpiece holder is beyond the robot’s reach, an additional penalty is applied. The total penalty

is calculated using Equation (

19).

Here

is the collision threshold distance,

are the large positive constants, and

is the binary indicator function.

4.3.3. Selection, Elitism and Replacement

In each generation, all P individuals are evaluated and sorted according to their cost function in descending order.

Truncation selection: The top half of the population is retained as parents for generating the next population.

Elitism: The single best individual in the current generation is preserved and directly carried over to the next generation. This guarantees that the best solution found so far is never lost.

Replacement: Offspring are generated from the selected parents until the population size is restored to .

This strategy balances exploitation (retaining the fittest solutions) with exploration (creating diversity through offspring).

4.3.4. Crossover and Mutation

The crossover operator combines two parent layouts to form a new child layout. Let

and

represent two parents. The child layout

is constructed gene by gene using uniform crossover. This can be represented by Equation (

20), where

a is the crossover rate.

The mutation operator introduces diversity by perturbing the placement of the robot or containers. With probability

b, the robot is reassigned to a new feasible location using Equation (

21), sampled uniformly from the set of conveyor-adjacent free cells. After selecting a new robot position, the neighborhood of feasible workpiece holder positions are recomputed by Equation (

22).

Independently, with probability

b each of the two workpiece holder positions are resampled from the neighborhood of

as follows:

The final optimized solution is obtained using Equation (

1). This is how layout optimization is performed using GA.

4.3.5. Computation of Targets

Once the robot and the two workpiece holder placements are determined through the layout optimization process, the next step is to compute the task-specific target positions required for motion planning. This research defines the pick position as the acquisition point where the robotic system retrieves objects from the conveyor belt, and the place positions as the target locations where these objects are deposited into specified workpiece containers. The computation of these target positions is carried out by evaluating the geometric relationships between the robot and the surrounding environment.

The nearest conveyor cell within the robot’s reachable workspace is identified using a Euclidean distance metric. If the robot base position is denoted by

, and the position of each conveyor cell by

, then the closest conveyor cell is determined by Equation (

24).

To ensure feasible grasping, a small vertical offset

m) is added, yielding the final pick position as follows:

The two workpiece holders act as deposition targets. If the positions of the holders are

, then the corresponding place positions are computed by Equation (

26), where

.

This computation ensures that the robot always selects a feasible picking location on the conveyor and well-defined placing locations above the holders. These target poses, derived directly from the optimized layout, serve as input for the subsequent motion planning stage.

4.4. Motion Planning

The motion planning stage ensures that the robot transitions safely between the pick-and-place targets. In this work, motion planning is performed using a target-biased nearest-neighbor rapidly exploring random trees (TNN-RRT) algorithm, which extends the classical RRT framework. Instead of relying on uniform random sampling alone, the proposed algorithm introduces a target-biased nearest-neighbor metric that combines configuration-space distance with a bias toward the goal. While RRT* is capable of asymptotically optimal path generation, it requires significantly more computation to rewire the tree in high-dimensional joint spaces, which may become prohibitive for real-time pick-and-place tasks. In contrast, TNN-RRT prioritizes rapid exploration with goal-directed growth, achieving faster convergence while still producing feasible collision-free paths suitable for the hierarchical optimization framework. This modification improves the trade-off between exploration and exploitation, allowing the tree to expand while maintaining directed progress toward the desired end-effector posture. By directly employing TNN-RRT rather than the baseline RRT or RRT*, the planner balances computational efficiency and path quality in high-dimensional joint space subject to joint limits. The pseudocode of TNN-RRT is summarized in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2: Target-biased nearest neighbor (TNN-RRT) algorithm |

![Applsci 15 11941 i002 Applsci 15 11941 i002]() |

Random samples are drawn uniformly from the feasible configuration space

C. For each sampled configuration, the nearest node in the tree is selected using a blended distance provided by Equation (

27).

where

is the Euclidean distance in joint space.

is the task-space distance of configuration q to the target , computed through forward kinematics .

is the blending factor that balances exploration and goal biasing .

A new candidate configuration is generated by steering from

to

using Equation (

28), where

is the infinity-norm saturation operator provided by Equation (

29). This ensures that each step respects the maximum incremental joint displacement

s.

The tree

is updated when

is collision-free. The node

is added to the tree with parent

. The distance to the goal is updated by Equation (

30), and the best configuration so far is tracked by (

31).

The path is extracted when the termination condition (

) is satisfied. The extracted path is formulated using Equation (

5), and the target posture is recorded using Equation (

6). After the motion planner obtains all three target postures, these are transferred to the posture optimization stage to obtain a single optimal posture.

4.5. Surrogate Modeling

Despite the efficiency gains of the target-biased nearest-neighbor RRT (TNN-RRT), a fundamental bottleneck remains in the repetitive evaluation of candidate configurations through forward kinematics, collision checking, and steering operations. These computations accumulate substantial overhead, particularly when the planner is invoked repeatedly within the hierarchical optimization framework. To further reduce this computational burden, a surrogate-assisted strategy is adopted, where a data-driven model approximates the performance of candidate paths without requiring full TNN-RRT evaluations at every iteration.

As illustrated in

Figure 3, the process begins with generating reference trajectories using the TNN-RRT planner. These data samples are then used to train the surrogate model, which acts as a computationally inexpensive proxy for path evaluation. This integration of surrogate modeling with TNN-RRT enables efficient exploration of the search space while maintaining accuracy and feasibility of the motion planning stage.

4.5.1. Training Data and Preprocessing

The surrogate model was constructed from trajectory datasets recorded during robot motion planning episodes. Each record contained the robot’s current base position

, target position

, robot end-effector position

, and joint angles

. The associated ground-truth output variable was the task-space Euclidean distance

between the end-effector and the target computed by Equation (

32).

The dataset was filtered to retain only collision-free configurations (penalty,

) with distances (

m) within the robot’s reachable workspace. This ensures that the surrogate learns only feasible mappings. Formally, the training dataset is represented by Equation (

33), where the input feature vector

is defined by Equation (

34).

4.5.2. Surrogate Model Formulation and Integration

The surrogate models are formulated as a regression function

that approximates the mapping from configuration features

to the distance-to-target

d as follows, where

denotes the learned model parameters.

In this study, several surrogate models were generated using the trained dataset, and the performance of these surrogate models is discussed in detail in

Section 5.3. The best surrogate model was integrated into the RRT expansion step to guide sampling and steering. Specifically, when sampling new candidate configurations

, the surrogate provides a rapid estimate

. Configurations with lower predicted distance obtained by Equation (

36) are preferentially selected for tree expansion.

In cases where the planner approaches but cannot directly reach the target (due to narrow passages or workspace limits), the surrogate provides near-optimal configurations retrieved from the trained dataset (minimum-distance candidates). These act as surrogate-goals that the tree biases toward, improving success rates in cluttered environments. Algorithmically, this reduces redundant sampling in infeasible regions and accelerates convergence toward valid solutions. The SA-RRT algorithm is provided in Algorithm 3.

| Algorithm 3: Surrogate-Assisted RRT (SA-RRT) Algorithm |

![Applsci 15 11941 i003 Applsci 15 11941 i003]() |

4.6. Posture Optimization

The objective of posture optimization is to determine the robot’s optimal joint configurations

that minimize overall task execution cost while satisfying joint limits and ensuring collision-free motion. The algorithm used for posture optimization is provided in Algorithm 4.

| Algorithm 4: Genetic algorithm for posture optimization |

![Applsci 15 11941 i004 Applsci 15 11941 i004]() |

Each candidate posture

q is evaluated using a composite cost function provided in Equation (

37).

Here

represents the collision penalty of candidate configuration

q causes for self-collision or collision with the environment objects. A constant penalty is added using Equation (

38). Cycle time

between initial config

and config

q is calculated using Equation (

39) and reach time

to complete the pick-and-place task sequence computed using Equation (

40).

This is how the layout, motion, and posture optimization are completed using the proposed hierarchical framework.

5. Experimental Results

5.1. Experimental Setup and Conditions

The proposed framework was validated through computational experiments conducted in the Unity simulation environment (Unity 2022.3 LTS) using the built-in physics engine. All simulations were performed on a computer with an Intel Core i7-13650HX (2.60 GHz) processor, 16 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA RTX 4060 GPU. The robotic platform considered in this study is the Niryo NED, a 6-degree-of-freedom (DOF) collaborative manipulator imported into Unity via the URDF importer. The robot consists of six revolute joints with joint limits and velocity constraints summarized in

Table 2.

Although Unity was used as the simulation environment, the optimization components are robot-model-based rather than simulation-dependent. All kinematic limits, forward kinematics computations, and joint feasibility checks are derived directly from the actual URDF of the Niryo NED. Therefore, the target joint configurations produced by the motion planning and posture optimization stages are physically valid and directly executable on the real Niryo NED hardware through its official control interface (e.g., Niryo Studio). In this context, Unity functions only as a visualization and physics execution platform, while the generated joint configurations remain transferable to a real robotic setup without modification to the optimization algorithms.

For layout optimization, a genetic algorithm (GA) was employed with a population size of 30 and 100 generations. Several surrogate models were trained on 8000+ samples with a training–validation split of 80%–20%. Motion planning was performed using the best surrogate-assisted rapidly exploring random trees (SA-RRT) planner. Performance was evaluated in terms of computation time, task completion time, and collision avoidance rate.

5.2. Layout Optimization Analysis

The initial and final robot placements were compared to evaluate the performance of the layout optimization stage.

Figure 4 illustrates the evolution from the initial layout to three representative optimized layouts. Specifically,

Figure 4a shows the initial placement, while

Figure 4b–d present optimized placements obtained after 100 generations. Among these,

Figure 4b corresponds to a layout solution with cost of 1.36, where one target location becomes unreachable.

Figure 4c,d illustrate feasible optimized layouts with costs of 1.02 and 0.90, respectively, where all targets remain reachable. These results confirm that the GA effectively relocates the robot and workpiece holders within reachable free cells while avoiding obstacle cells, thus reducing the probability of collisions and improving the feasibility of the subsequent motion planning stage.

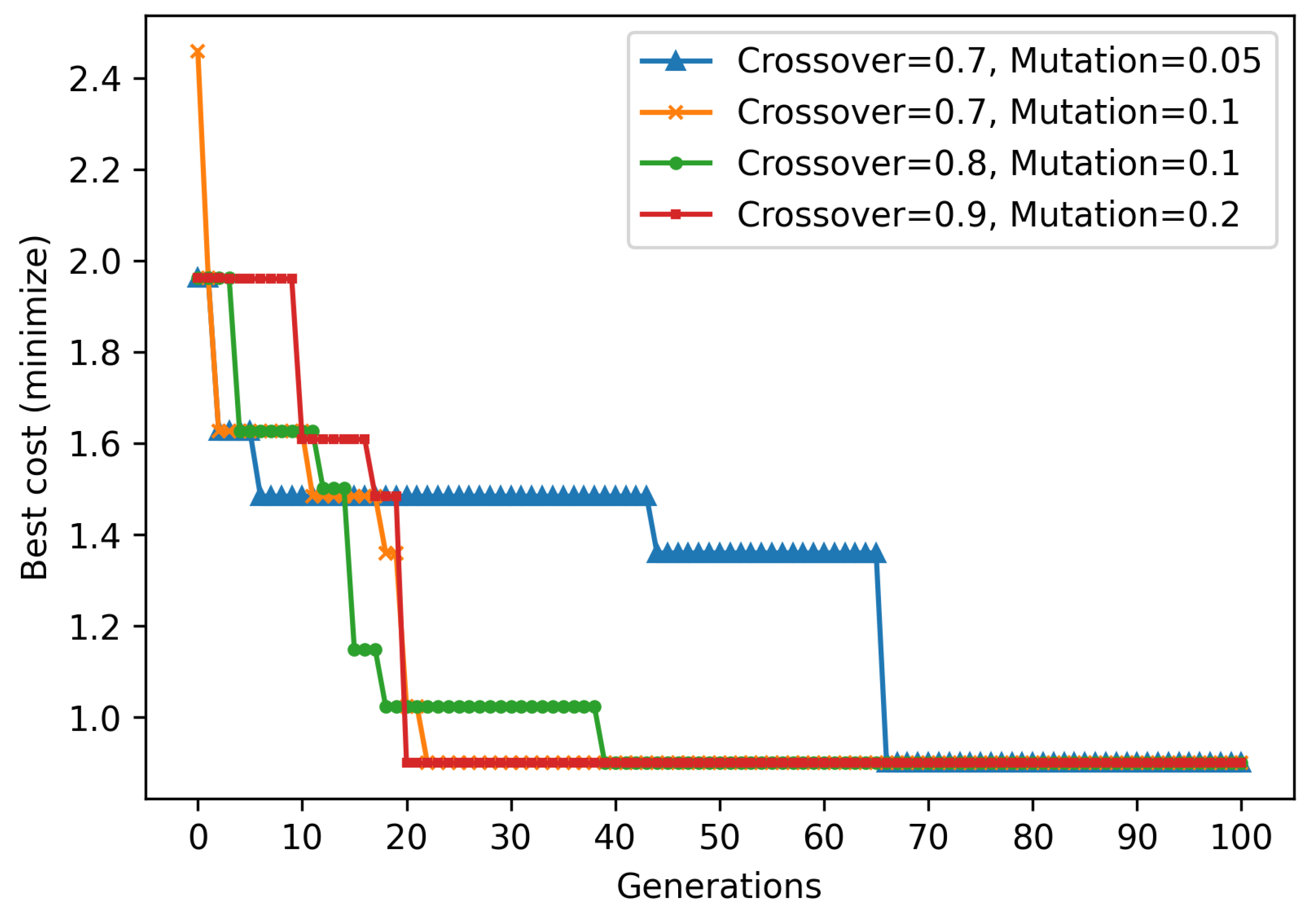

The convergence behavior of the GA is shown in

Figure 5. It can be observed that for different crossover and mutation rates, the optimization progressively minimizes the cost function value and reaches a stable solution after approximately 20∼40 generations. The minimum theoretical value of the layout optimization cost function is

, which corresponds to the ideal arrangement where all penalty terms are zero and the distances between the robot and the two workpiece holders are minimized to their lowest possible values. Specifically, when no infeasibility penalties are applied, the total cost is determined solely by the sum of the three distances

. In the optimal configuration, each workpiece holder is placed in an adjacent cell relative to the robot’s base, resulting in each distance

, which exactly equals the distance between the centers of two neighboring cells in the discretized workspace. Therefore, the minimum achievable cost is

. This value is confirmed by

Figure 4d, which shows the final optimized layout with a cost of

, and by

Figure 5, where the convergence curve stabilizes at this theoretical minimum. Although GAs are generally stochastic in nature, the search space in this layout optimization is discrete and finite, and the theoretical minimum cost (

) is analytically known. Since the GA consistently converged to this value across multiple runs and no lower-cost configuration exists in the discretized workspace, the obtained solution can be identified as the global optimum for this problem instance. This demonstrates the ability of the GA to balance exploration and exploitation of the search space.

To further examine the robustness of the GA, a sensitivity analysis was performed by varying crossover and mutation probabilities. The average cost function values obtained across different generations with a fixed population size of 30 are shown in

Figure 6. The results indicate that although the optimization performance is somewhat affected by parameter choices, the GA consistently converges to high-quality solutions. This confirms the reliability of the approach for layout determination.

5.3. Performance of Surrogate Modeling for Motion Planning

To evaluate the effectiveness of surrogate modeling, an experimental dataset of more than 8000 samples was generated. The dataset was split into 80% for training and 20% for testing, and multiple regression models were benchmarked using the scikit-learn library. The comparison was carried out in terms of the coefficient of determination (

), root mean squared error (RMSE), mean squared error (MSE), mean absolute error (MAE), cross-validation

mean (

), and training time.

Table 3 summarizes the performance of the tested models.

The results indicate that the

Extra Trees model achieved the best overall performance, with the highest

score of 0.9250 and the lowest error metrics (RMSE = 0.033, MAE = 0.018). Despite a slightly higher training time than Gradient Boosting, it significantly outperformed all other models in terms of accuracy and generalization. Cross-validation results confirm that

Extra Trees maintained reasonable generalization across different data splits, though its mean CV score (0.584) was lower than the single test set performance (0.925), indicating some sensitivity to data partitioning. These findings support the use of Extra Trees as the surrogate model for integration into the motion planning algorithm. The predictive performance of the surrogate models was evaluated using the coefficient of determination

and the corresponding training time.

Figure 7 presents the

scores obtained for each model, while

Figure 8 illustrates the associated training time.

Figure 9 shows the predictive performance of the Extra Trees surrogate model by comparing actual and predicted minimum distances for all robot–target position pairs in the test dataset. The x-axis represents the sample index, while the y-axis shows the distance in meters. Blue circles denote actual minimum distances from simulations, and green crosses indicate surrogate predictions. Their overlapping nature with few errors, mostly within ±0.06 m (red line), highlights the model’s accuracy in capturing the nonlinear mapping between robot and target configurations. When the surrogate model is integrated into the RRT framework for motion planning, the SA-RRT algorithm first checks whether the current robot–target position pair matches a surrogate position pair. If a match is found, the SA-RRT algorithm retrieves the joint angle configuration from the surrogate samples associated with the minimum distance. This enables the robot arm to move to the desired posture efficiently, avoiding redundant evaluations and demonstrating the surrogate’s effectiveness for integration into sampling-based motion planners.

5.4. Motion Planning Performance and Path Efficiency

This subsection evaluates the performance of the Surrogate-Assisted RRT (SA-RRT) in comparison to the standard target-biased nearest neighbor RRT (TNN-RRT). The assessment considers both qualitative and quantitative measures, including the efficiency of generated paths, the number of iterations required to reach the target, collision occurrences, computation time, and total task completion time.

Figure 10 provides a comparative visual analysis of the representative paths generated by the TNN-RRT in

Figure 10a–c and SA-RRT in

Figure 10d–f algorithms for the pick, first placement, and second placement tasks, respectively. Although neither TNN-RRT nor SA-RRT provides theoretically guaranteed global optimality for the obtained trajectories, the SA-RRT variant used in this work offers an improved trajectory quality compared to TNN-RRT. In SA-RRT, when a surrogate match exists for a robot-target position pair, it directly retrieves joint configurations that the surrogate predicts to be near-optimal (minimal end-effector distance) and expands the tree from those near-optimal states first while still preserving random exploration when no match is found. This bias systematically reduces the expected number of expansions required to reach the target and therefore converges toward shorter and smoother feasible trajectories in fewer iterations compared to the baseline TNN-RRT. The TNN-RRT trajectories exhibit longer deviations and more irregular motion patterns as shown in

Figure 10a–c, whereas the SA-RRT trajectories demonstrate smoother joint transitions with reduced path deviations as shown in

Figure 10d–f, respectively. This qualitative difference aligns with the quantitative performance improvements reported in

Table 4 and reinforces that SA-RRT consistently generates more efficient motion paths.

Table 4 quantitatively compares the two planners across multiple metrics. SA-RRT consistently requires fewer iterations to converge to the target, generates non-collided nodes, and achieves zero collision rates. Furthermore, the computation time and task completion time are significantly reduced due to the surrogate model guidance, which retrieves precomputed joint configurations for matched robot–target position pairs, avoiding excessive evaluations.

Figure 11 illustrates the evolution of the end-effector’s distance to the goal across successive nodes for both planners. For each task, both TNN-RRT and SA-RRT start from the same initial distance and converge to the same final target distance. However, the SA-RRT trajectories reach the goal in substantially fewer nodes, indicating more direct convergence and reduced exploration overhead. By contrast, TNN-RRT requires a larger number of intermediate nodes to achieve the same final distance. These results highlight that the surrogate-assisted approach enhances the efficiency of the RRT search process, enabling faster convergence toward feasible paths while preserving path quality.

5.5. Posture Optimization Analysis

In this subsection, we analyze the performance of GA-based posture optimization for the 6-DOF manipulator. The goal of the optimization is to minimize the composite cost function calculated using Equation (

35), which includes collision penalties, cycle time (time to move from initial to optimized configuration), and reach time (cumulative time to reach the pick, place1, and place2 configurations from the optimized posture). The GA was executed with a population size of 30 over 100 generations, and the best solution was selected based on the lowest fitness value.

Figure 12a,b presents the initial and the optimized configuration representative snapshots of the manipulator obtained by the GA. The optimized posture reduces the required motion to reach all task configurations while remaining collision-free.

Table 5 summarizes the posture optimization performance, including total joint motion, cycle time, and reach time. The last column of this table presents the cost value

for each evaluated posture, which is calculated using the composite cost function in Equation (

35). For collision-free configurations, where the penalty term

, the cost value corresponds to the summation of the cycle time and the total reach time. The cycle time measures the motion duration required to move the robot from its initial home configuration

to the candidate posture

q, while the reach time represents the cumulative time to execute the subsequent pick-and-place sequence from posture

q. The GA achieved a cost reduction of 2.24%, and lowered the cumulative reach time by 8.44% compared to the initial configuration. These results confirm that posture optimization can substantially improve task efficiency by providing a favorable starting posture for the subsequent task execution pipeline.

Posture optimization was performed as the final stage of the hierarchical framework to refine the manipulator’s joint configurations after feasible paths were identified. The main objective was to minimize joint displacement while ensuring collision-free execution of the planned tasks. This step is particularly important for reducing mechanical stress, improving energy efficiency, and enhancing overall task feasibility in narrow workspaces.

6. Discussion

The results presented in

Section 5 provide a comprehensive evaluation of our hierarchical optimization framework for robotic pick-and-place tasks. Three key aspects—layout optimization, motion planning using SA-RRT, and posture optimization—collectively demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed approach.

Layout Optimization: The genetic algorithm-based layout optimization successfully positions the NED robots and the workpiece holders to maximize task feasibility while minimizing interference. The optimized layouts maintain sufficient inter-robot distances and ensure that the robot can access its assigned workspace zones. These findings align with previous studies emphasizing the importance of task-specific workspace arrangement for single-robot systems [

3,

4,

43]. Compared to arbitrary or manually chosen placements, our GA-based approach reduces potential collisions and improves accessibility, thus providing a robust foundation for subsequent motion planning.

Motion Planning with SA-RRT: The surrogate-assisted RRT reduces the number of sampled nodes required to generate collision-free trajectories to each target (pick, place1, and place2) compared to the baseline TNN-RRT. While the total end-effector path distance remains similar, the reduction in nodes results in faster computation and smoother trajectories. Importantly, SA-RRT maintains the same start and end positions as TNN-RRT, demonstrating that the surrogate model effectively guides the planner toward feasible configurations. This highlights the efficiency benefits of integrating surrogate models into RRT-based motion planning, consistent with prior work on data-driven sampling guidance [

23,

44].

Posture Optimization: The GA-based posture optimization identifies an initial configuration that minimizes a combined fitness metric, including collision penalties, cycle time from the initial to optimized configuration, and reach time to all three task positions. The optimized posture reduces reach time by approximately 8.44% and decreases cumulative joint angles compared to the pick and place configurations. These improvements indicate that strategic selection of the robot’s initial posture can enhance overall task efficiency, reduce mechanical strain, and lower cycle time. Previous research supports this observation, showing that optimized robot postures contribute to faster and safer task execution [

20,

21,

45].

To contextualize our computational gains, we compare SA-RRT with three recent optimization planners. Recently, a deep reinforcement learning-based Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) motion planning scheme for industrial manipulators [

46] demonstrated 52.7–75.1% reduction in motion-planning time for UR5 configurations using sensor-based observations. The study in [

47] integrated RRT with Chaotic Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) for 6-DOF manipulators and reported 21% computation time improvement over baseline RRT, while [

48] proposed a PSO-enhanced RRT* with rotation-angle constraints for mobile robots, reporting 5.6–37.2% gains for different scenarios. In contrast, the surrogate-assisted approach adopted in this work achieves a 76.17% computation time reduction in multi-target pick–place tasks. While these studies differ in platforms, environments, and metrics, the comparison indicates that surrogate-guided sampling can yield larger efficiency gains than PSO-based hybrid methods. The larger gain in our work is primarily attributable to (i) using a surrogate to avoid expensive collision checks and (ii) directly reusing previously recorded minimal-distance samples (joint postures) when a surrogate match is found. A summary is provided in

Table 6.

The proposed hierarchical model shows strong potential for scalability and generalization. For larger workspaces with more target points, the front-end layout optimization becomes even more critical to preventing computational bottlenecks in motion planning. The SA-RRT’s efficiency would be a significant advantage in such cluttered environments. While this study utilized a specific NED robot, the framework is agnostic to the robot configuration. The posture optimization module would naturally adapt to different kinematic chains (e.g., SCARA or articulated robots with more DOFs) to find an efficient home configuration. Finally, the method’s adaptability to varying task complexities such as dynamic obstacles or different payloads could be enhanced by integrating real-time re-planning at the motion level, a promising direction for future work.

Together, these results demonstrate that a hierarchical optimization approach—starting from the layout, followed by motion planning and posture optimization—can significantly improve the efficiency and safety of single-robot pick-and-place operations. By reducing unnecessary movements and planning overhead, the framework provides practical guidance for industrial automation scenarios where time-efficient and collision-free operation is critical.