State Evaluation of Wheel–Rail Force in High-Speed Railway Turnouts Based on Multivariate Analysis and Unsupervised Clustering

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Preprocessing

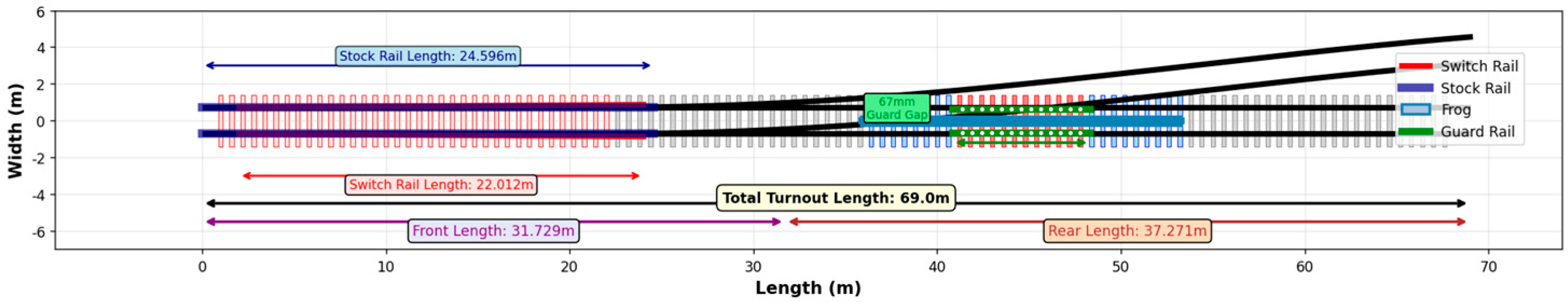

2.1.1. Data Source

2.1.2. Data Preprocessing

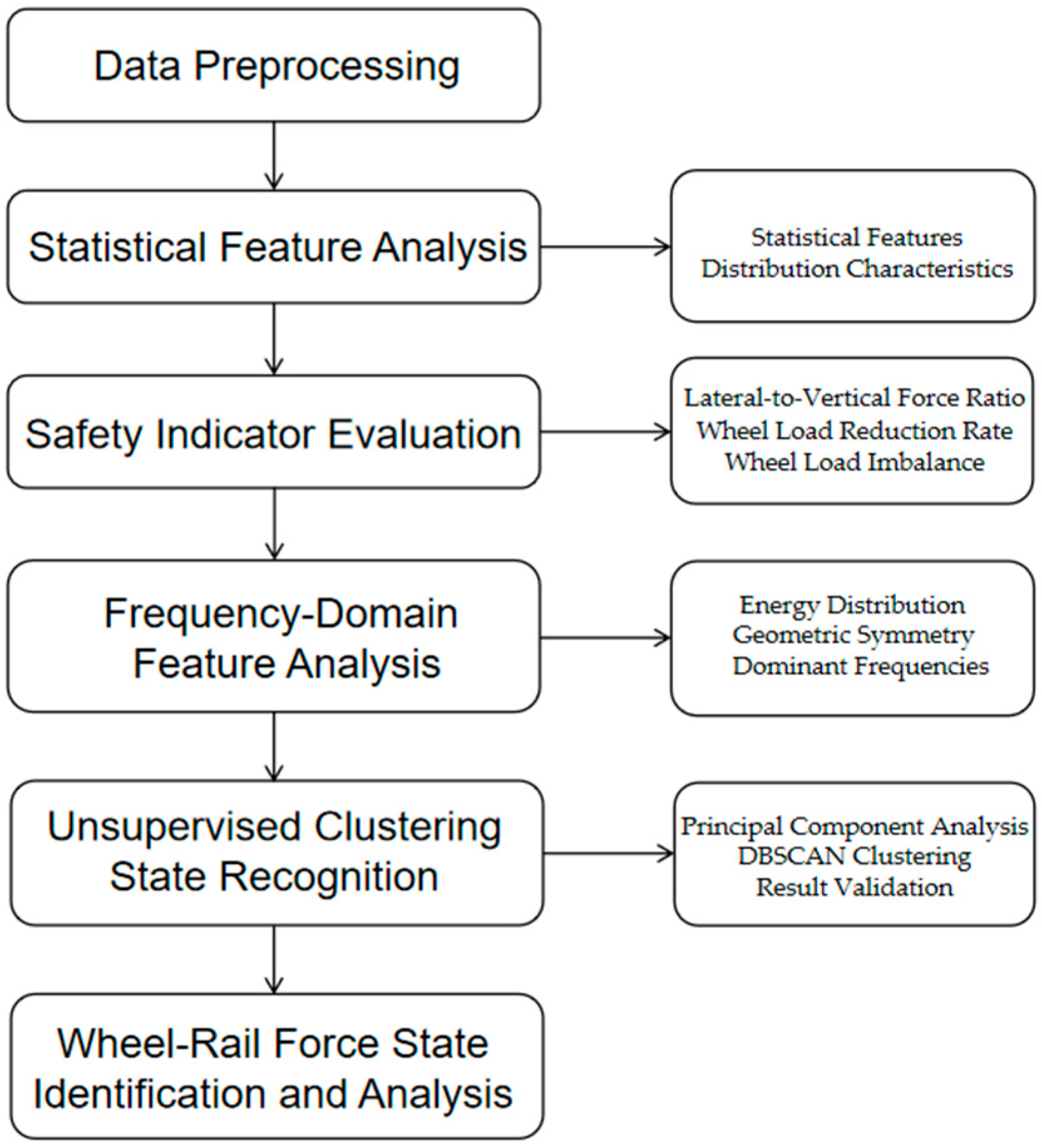

2.2. Multivariate Analysis Framework

2.2.1. Overall Design of the Technical Framework

2.2.2. Statistical Feature Analysis

2.2.3. Safety Indicator Evaluation

2.2.4. Frequency-Domain Feature Analysis

2.2.5. Unsupervised Clustering State Recognition

3. Results

3.1. Experimental Results and Analysis

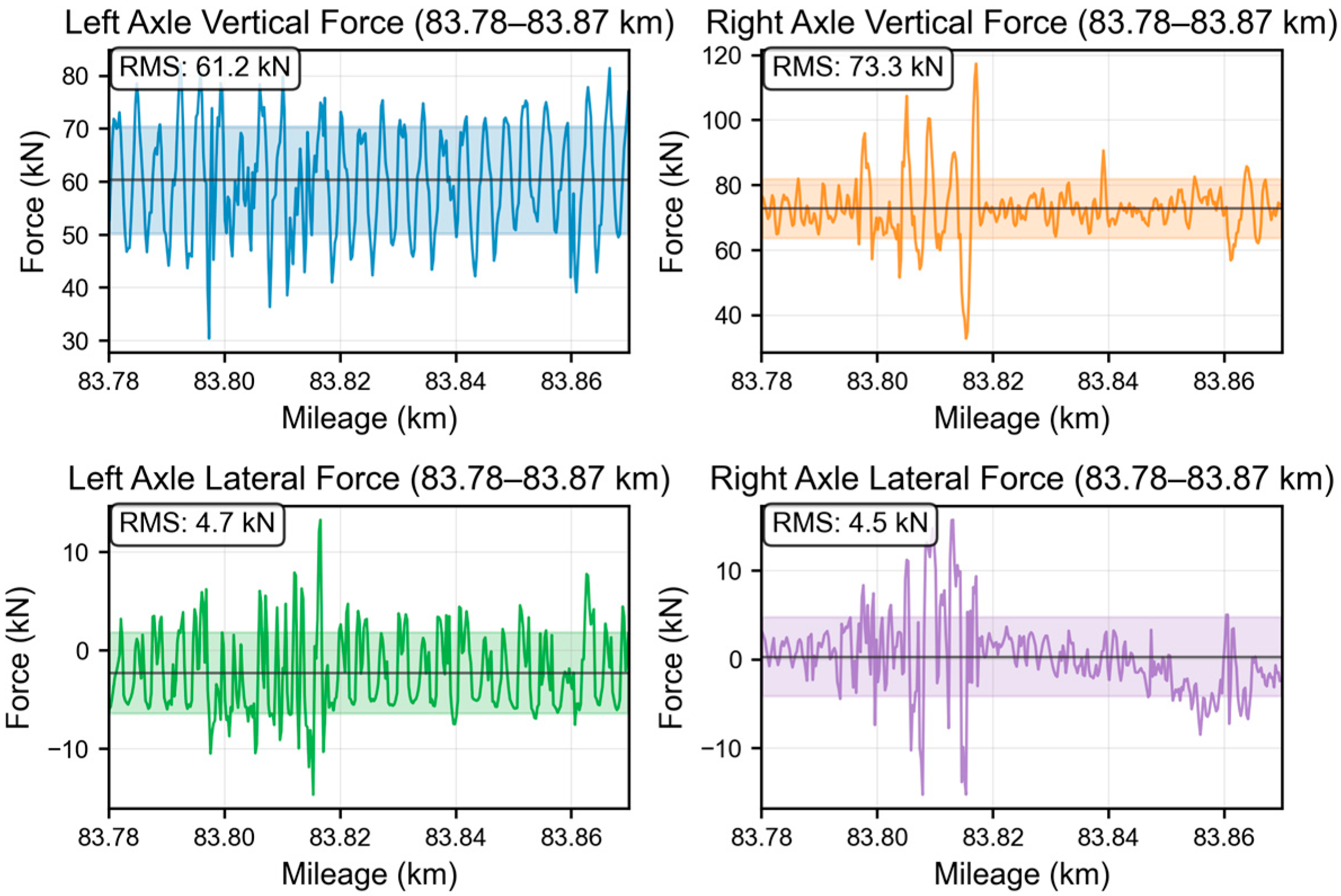

3.1.1. Time-Domain Analysis of Wheel–Rail Forces

3.1.2. Significant Vertical Force Imbalance

3.1.3. Significant Lateral Force Impact Characteristics

3.1.4. Coupling Relationships Among Force Components

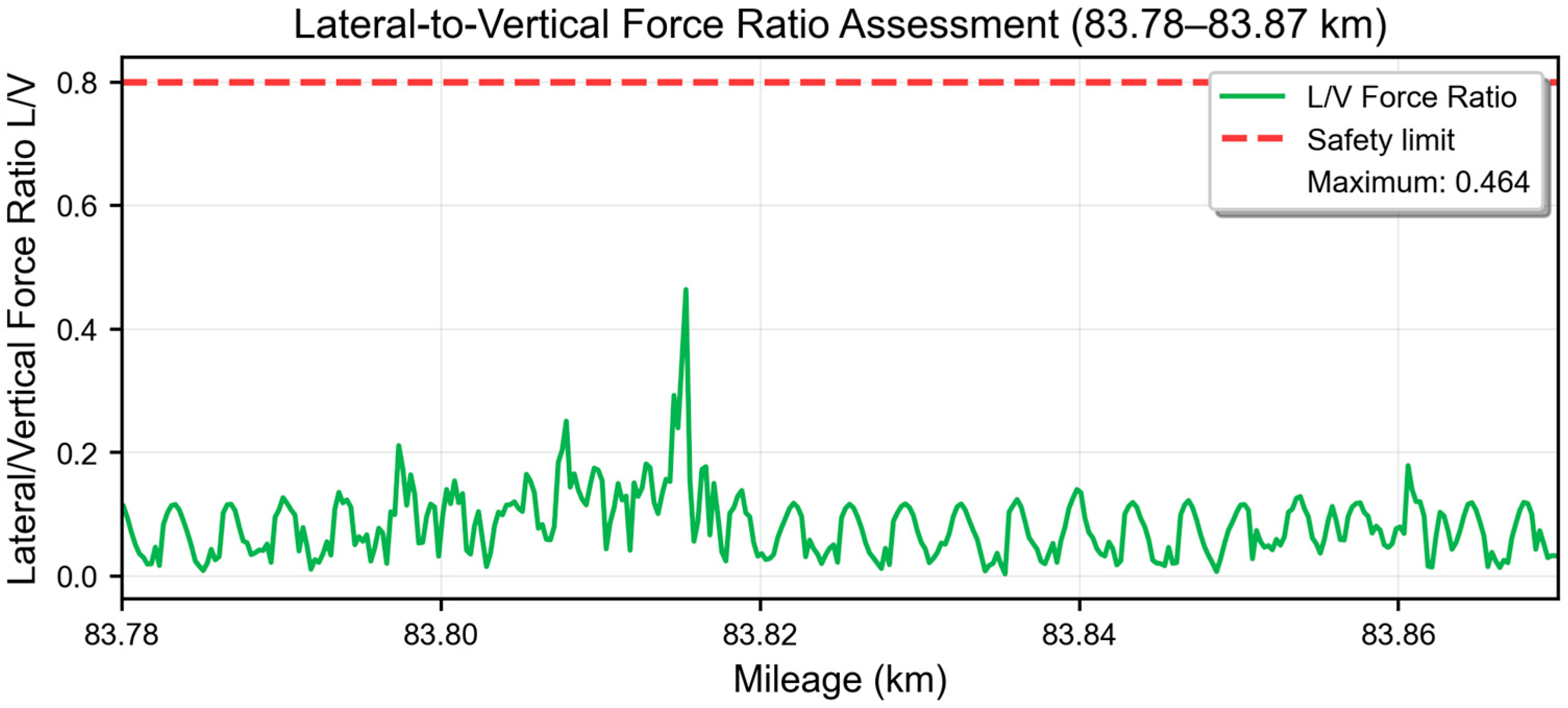

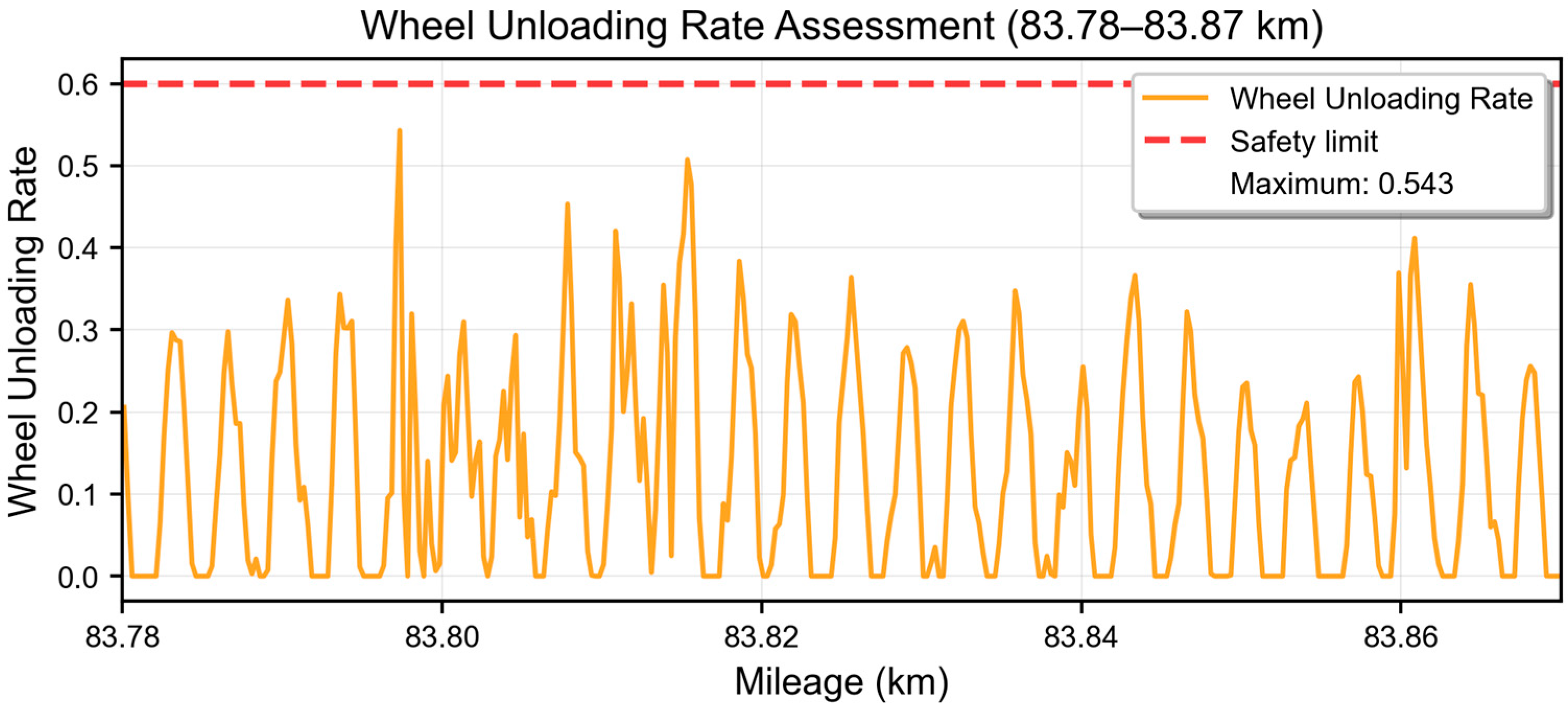

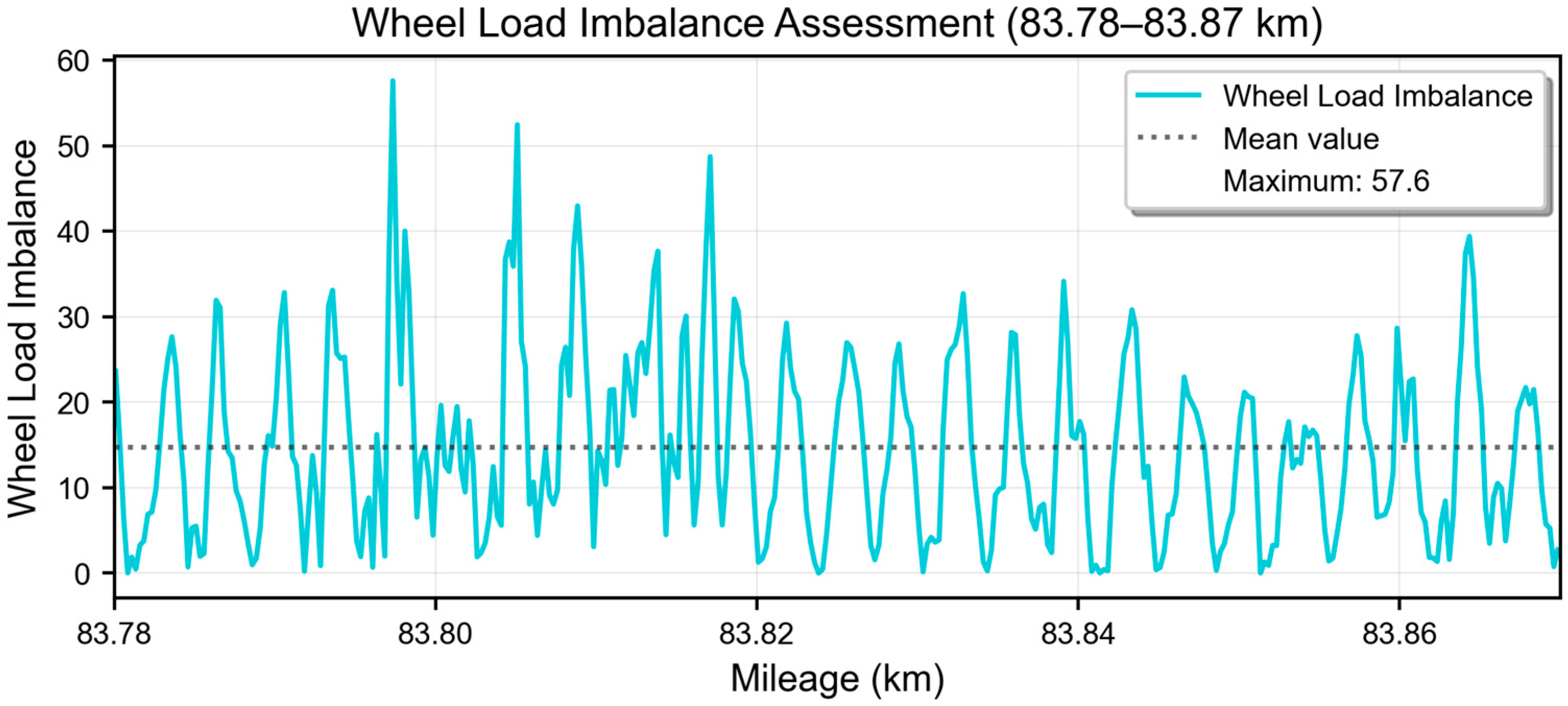

3.2. Evaluation of Wheel–Rail Contact Safety

3.2.1. Assessment of Lateral-to-Vertical Force Ratio

3.2.2. Assessment of Wheel Load Reduction Rate

3.2.3. Assessment of Wheel Load Imbalance

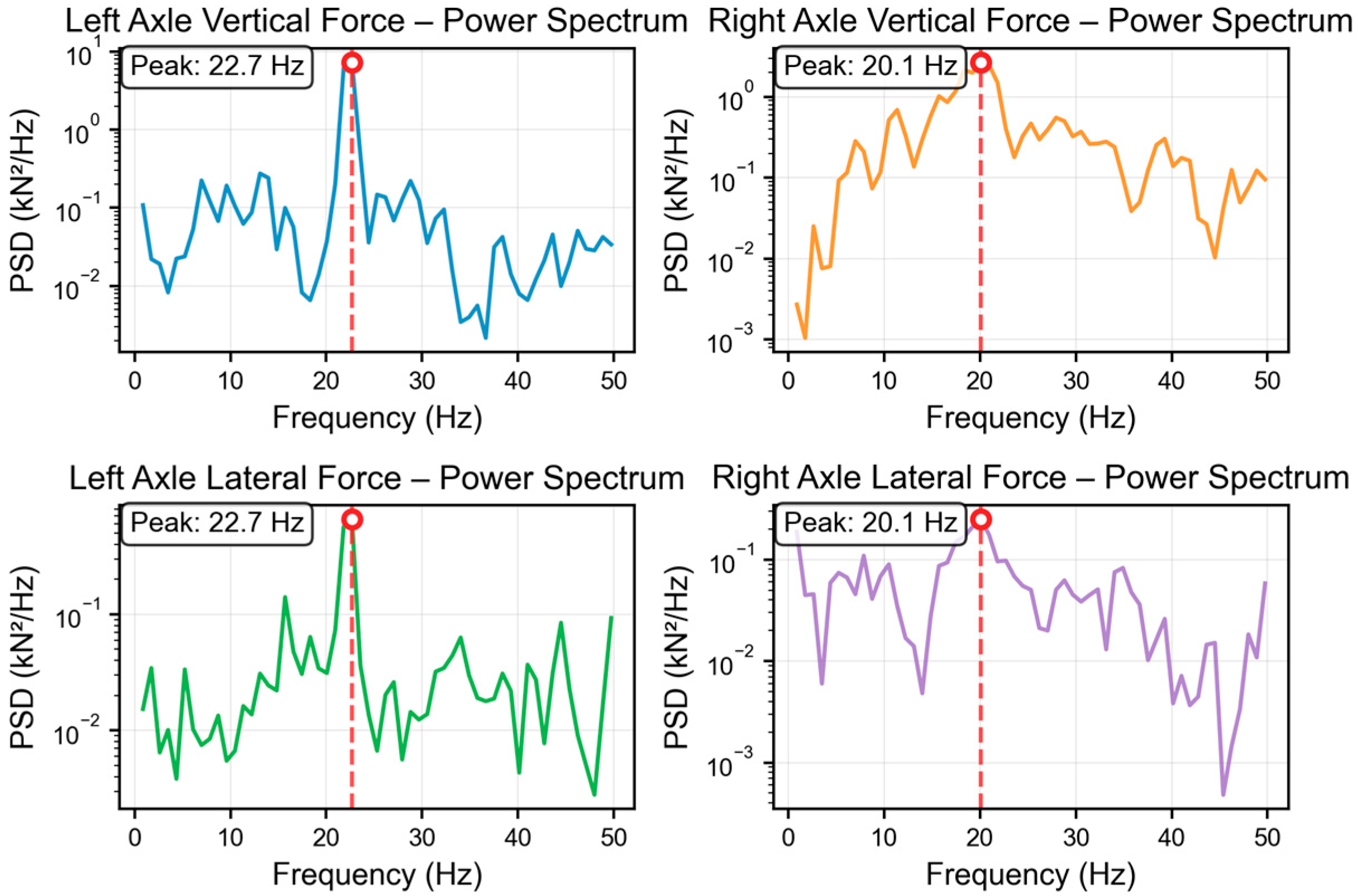

3.3. Frequency Domain Characteristics Analysis of Wheel–Rail Forces

- Geometric asymmetry: The geometric structure of the frog nose and wing rail is asymmetric, resulting in differences in the contact sequence and position between the left and right wheels, thereby affecting the distribution of lateral force amplitude.

- Differences in contact modes: During train passage, the right wheel may experience specific contact modes, such as contact with the wing rail or guidance by the guard rail. Its lateral force response differs in amplitude and energy from that under normal wheel–rail contact conditions.

- Load transfer path: The complex load transfer paths in the turnout section cause differences in the energy distribution of the lateral forces between the left and right wheels. Even if the dominant frequencies are close, imbalance in amplitude and energy may still occur.

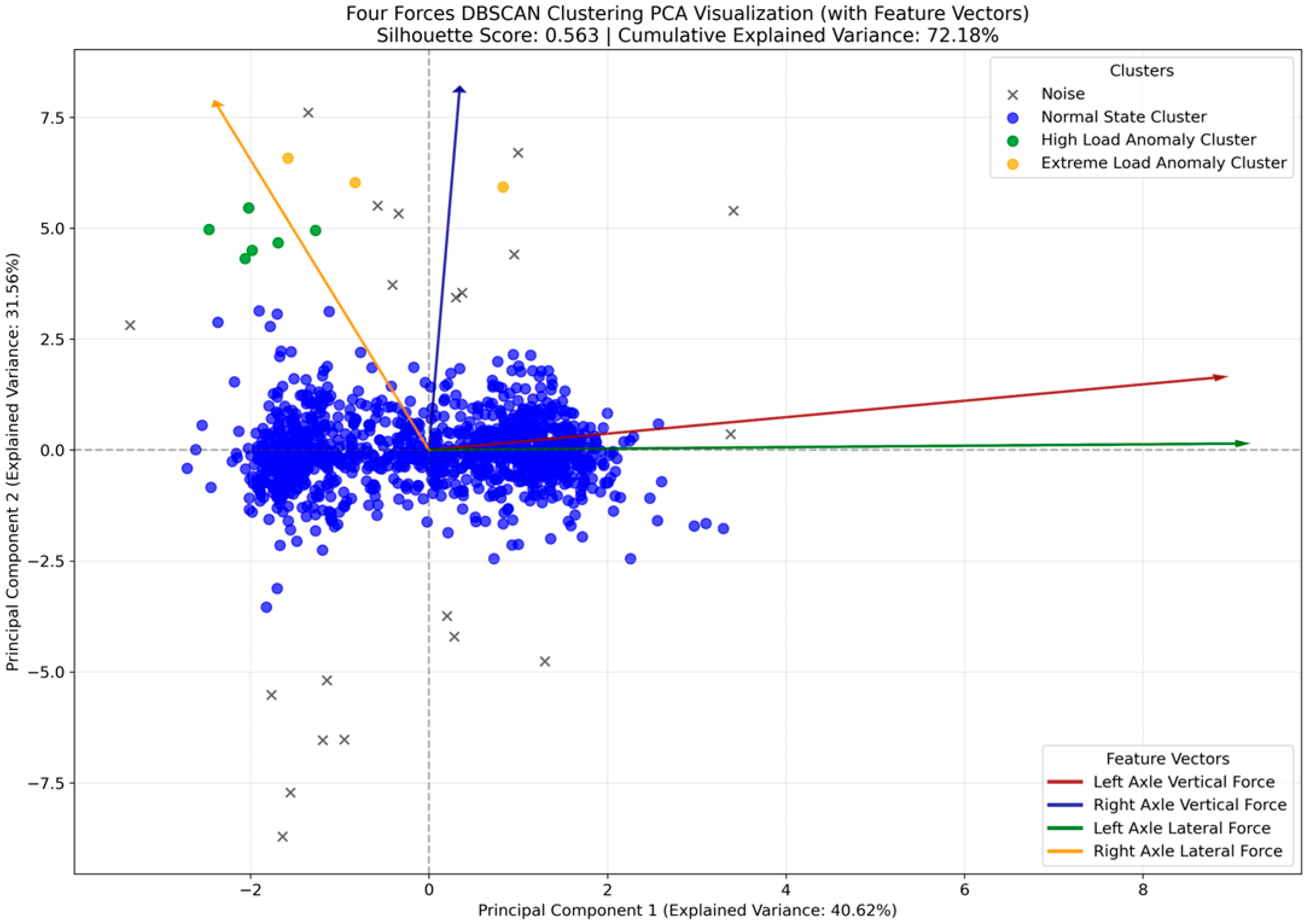

3.4. Principal Component and Cluster Analysis

3.4.1. Analysis of Principal Component Load Contributions

3.4.2. Analysis of Cluster Features and Distributions

3.4.3. Comprehensive Analysis and Engineering Implications

4. Discussion

- Safety evaluation has not applied differentiated threshold treatment for different structural sections, which may underestimate local risks.

- Data are limited to a single turnout on the Beijing–Tianjin intercity line, and the generalization of the method needs to be verified in other turnout or track environments.

- The clustering analysis results are sensitive to parameter selection, and further improvement of parameter adaptability remains necessary.

- The PCA and feature vectors in this study well explain the influence of factors. However, they only include vertical and lateral forces, without incorporating spectral characteristics, L/V indicators, and other information into the comprehensive analysis. This to some extent limits the capability of multidimensional feature representation in state identification and may also affect the comprehensive characterization of turnout performance under complex operating conditions.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ge, X.; Ling, L.; Guo, L.; Shi, Z.; Wang, K. Dynamic derailment simulation of an empty wagon passing a turnout in the through route. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2020, 60, 1148–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisilowski, J.; Kowalik, R. Railroad Turnout Wear Diagnostics. Sensors 2021, 21, 6697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Yang, Y.; Chang, C.; Li, D. Monitoring and Evaluation of High-Speed Railway Turnout Grinding Effect Based on Field Test and Simulation. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Lau, A.; Dai, J.; Frøseth, G.T. Identification of optimal accelerometer placement on trains for railway switch wear monitoring via multibody simulation. Front. Built Environ. 2024, 10, 1396578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, A.; Pålsson, B.; Ekh, M.; Nielsen, J.C.O.; Ander, M.K.A.; Brouzoulis, J.; Kassa, E. Simulation of Wheel–Rail Contact and Damage in Switches & Crossings. Wear 2011, 271, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicklisch, D.; Kassa, E.; Nielsen, J.C.O.; Ekh, M. Geometry and Stiffness Optimization for Switches and Crossings, and Simulation of Material Degradation. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit 2010, 224, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Zhang, F.; Qian, L. Numerical Simulation of Stress and Deformation in a Railway Crossing. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2011, 18, 2296–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, C.; Dahlberg, T. Wheel/Rail Impacts at a Railway Turnout Crossing. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit 1998, 212, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Núñez, A.; Li, Z.; Dollevoet, R. Evaluating Degradation at Railway Crossings Using Axle Box Acceleration Measurements. Sensors 2017, 17, 2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Meddah, A.; Hass, K.; Kalay, S. Relating Track Geometry to Vehicle Performance Using Neural Network Approach. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit 2006, 220, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, F.; García, J.J.; Hernández, A.; Martín, J.C.; Ramos, J. Advanced Monitoring of Rail Breakage in Double-Track Railway Lines by Means of PCA Techniques. Appl. Soft Comput. 2018, 63, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odashima, M.; Azami, S.; Naganuma, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Watanabe, Y. Track Geometry Estimation of a Conventional Railway from Car-Body Acceleration Measurement. Mech. Eng. J. 2017, 4, 16–00498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, B.; Xu, T.; Chen, C.; Wang, F. Deep Forest-Based Fault Diagnosis for Railway Turnout Systems in the Case of Limited Fault Data. In Proceedings of the 2019 Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC), Nanchang, China, 7–9 June 2019; pp. 2636–2641. [Google Scholar]

- Lasisi, A.; Attoh-Okine, N. Principal Components Analysis and Track Quality Index: A Machine Learning Approach. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2018, 91, 230–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, C.; Simões, M.L. Prediction of Railway Track Condition for Preventive Maintenance by Using a Data-Driven Approach. Infrastructures 2022, 7, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Cui, Y.; He, Q.; Hu, W.; Jiang, W. Data-Driven Optimization of Railway Maintenance for Track Geometry. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2018, 90, 34–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadzadeh, S.M.; Galeazzi, R. The Predictive Power of Track Dynamic Response for Monitoring Ballast Degradation in Turnouts. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit 2020, 234, 976–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Márquez, F.P.; García-Pardo, I.P. Principal Component Analysis Applied to Filtered Signals for Maintenance Management. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2010, 26, 523–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, D.; Xue, R.; Cui, K. A Data-Driven Fault Diagnosis Method for Railway Turnouts. Transp. Res. Rec. 2019, 2673, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiem, M.; Borodin, V.; Hnaien, F.; Snoussi, H.; Vaezi, T. An Unsupervised Fault Detection Support System for Railway Turnouts. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Railway Operations Modelling and Analysis RailDresden 2025, Dresden, Germany, 1–4 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Cao, Y.; Li, P.; Su, S. Entropy Feature Fusion-Based Diagnosis for Railway Point Machines Using Vibration Signals Based on Kernel Principal Component Analysis and Support Vector Machine. IEEE Intell. Transp. Syst. Mag. 2023, 15, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.; Cheng, C.; Xie, G.; Hei, X. An Intelligent Fault Diagnosis Method Based on Curve Segmentation and SVM for Rail Transit Turnout. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2021, 41, 4275–4285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Dai, S.; Zheng, Z.; Liang, Y. Fault diagnosis of ZD6 turnout system based on wavelet transform and GAPSO-FCM. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference (ITSC), Indianapolis, IN, USA, 19–22 October 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 2187–2192. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, P.; Su, S. Vibration-based fault diagnosis for railway point machines using multi-domain features, ensemble feature selection and SVM. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 73, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Hei, X.; Ji, W.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, Y. A Fault-Diagnosis Method for Railway Turnout Systems Based on Improved Autoencoder and Data Augmentation. Sensors 2022, 22, 9438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sysyn, M.; Gruen, D.; Gerber, U.; Nabochenko, O.; Kovalchuk, V. Turnout monitoring with vehicle based inertial measurements of operational trains: A machine learning approach. Komunikácie 2019, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, H.; Duan, Z. Railway switch fault diagnosis based on multi-heads channel self attention, residual connection and deep CNN. Transp. Saf. Environ. 2023, 5, tdac045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sysyn, M.; Gerber, U.; Nabochenko, O.; Kovalchuk, V.; Gruen, D. Indicators for common crossing structural health monitoring with track-side inertial measurements. Acta Polytech. 2019, 59, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bałdyga, M.; Barański, K.; Belter, J.; Kalinowski, M.; Weichbroth, P. Anomaly detection in railway sensor data environments: State-of-the-art methods and empirical performance evaluation. Sensors 2024, 24, 2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Zhang, W.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X. RTINet: A Lightweight and High-Performance Railway Turnout Identification Network Based on Semantic Segmentation. Entropy 2024, 26, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, J. An Intelligent Two-Stage Fault Classification Model for Railway Turnout Systems Based on FastDTW. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2024, 2024, 3715605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekjafarian, A.; Sarrabezolles, C.A.; Khan, M.A.; Faiz, J.; Lombaert, G. A Machine-Learning-Based Approach for Railway Track Monitoring Using Acceleration Measured on an In-Service Train. Sensors 2023, 23, 7568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Qian, R.; Li, X.; Wang, Y. An Anomaly Detection Method for Wireless Sensor Networks Based on the Improved Isolation Forest. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Union of Railways (UIC). UIC Code 518: Testing and Approval of Railway Vehicles from the Point of View of Their Dynamic Behaviour—Safety—Track Fatigue—Running Behaviour; UIC: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- EN 14363; Railway Applications—Testing and Simulation for the Acceptance of Running Characteristics of Railway Vehicles—Running Behaviour and Stationary Tests. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2016.

- GB/T 5599-2019; Specification for Dynamic Performance Assessment and Testing Verification of Rolling Stock. Standardization Administration of China (SAC): Beijing, China, 2019.

- Welch, P. The Use of Fast Fourier Transform for the Estimation of Power Spectra: A Method Based on Time Averaging over Short, Modified Periodograms. IEEE Trans. Speech Audio Process. 2003, 15, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, F.J. On the Use of Windows for Harmonic Analysis with the Discrete Fourier Transform. Proc. IEEE 2005, 66, 51–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQueen, J.B. Some Methods of Classification and Analysis of Multivariate Observations. In Proceedings of the 5th Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, Berkeley, CA, USA, 21 June–18 July 1965; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1967; pp. 281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Ester, M.; Kriegel, H.P.; Sander, J.; Xu, X. A Density-Based Algorithm for Discovering Clusters in Large Spatial Databases with Noise. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD), Portland, OR, USA, 2–4 August 1996; AAAI Press: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 1996; pp. 226–231. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, J.H. Hierarchical Grouping to Optimize an Objective Function. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1963, 58, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseeuw, P.J. Silhouettes: A Graphical Aid to the Interpretation and Validation of Cluster Analysis. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 1987, 20, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calinski, T.; Harabasz, J. A Dendrite Method for Cluster Analysis. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 1974, 3, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I.T. Principal Component Analysis: A Review and Recent Developments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2016, 374, 20150202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Shen, T.; Huo, L.; Wang, Y.; Qin, H. State Evaluation of Wheel–Rail Force in High-Speed Railway Turnouts Based on Multivariate Analysis and Unsupervised Clustering. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11934. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211934

Wang J, Shen T, Huo L, Wang Y, Qin H. State Evaluation of Wheel–Rail Force in High-Speed Railway Turnouts Based on Multivariate Analysis and Unsupervised Clustering. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(22):11934. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211934

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jiahui, Tao Shen, Liang Huo, Yaoyao Wang, and Hangyuan Qin. 2025. "State Evaluation of Wheel–Rail Force in High-Speed Railway Turnouts Based on Multivariate Analysis and Unsupervised Clustering" Applied Sciences 15, no. 22: 11934. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211934

APA StyleWang, J., Shen, T., Huo, L., Wang, Y., & Qin, H. (2025). State Evaluation of Wheel–Rail Force in High-Speed Railway Turnouts Based on Multivariate Analysis and Unsupervised Clustering. Applied Sciences, 15(22), 11934. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211934