1. Introduction

Advanced Air Mobility is an overarching term used to describe the use of emerging innovative aircraft technology to transport passengers and cargo with the use of (in the vast majority) electric power for Vertical or Short Take-Off and Landing (eVTOL and STOL) aircraft. Urban Air Mobility is an additional subcomponent of the larger AAM ecosystem, focused on incorporating these aircraft into urban settings. For passenger-oriented services, market analyses have estimated a wide range of possible revenues, ranging from

$3.1 billion up to

$624 billion (adjusted to 2025 U.S. dollars from 2018 baseline values [

1]), depending on key assumptions and constraints. This substantial variability reflects the inherent uncertainty in forecasting demand and lifecycle costs for a novel transportation mode that relies on emerging technologies and requires new infrastructure development. For passenger transportation applications, early-stage operating costs on a per-mile basis are estimated to be similar to existing limousine or helicopter services, and significantly more expensive than other ground transportation modes [

1]. This study focuses on AAM evaluation by developing an Illinois-specific analytical framework that integrates statewide demographic, travel behavior, and infrastructure data to capture the distinct urban–regional dynamics of the state. Unlike general AAM assessments, it combines calibrated multimodal travel modeling with aviation system integration and policy-aligned scenario design, providing evidence-based, jurisdiction-specific insights to inform Illinois’s transportation and aviation planning.

Multiple AAM use cases have emerged, with passenger air taxi services representing one of the most anticipated applications. Shorter travel times due to higher vehicle speeds and path flexibility make such a service competitive with ground transportation for longer distances. However, the need for first/last mile travel and the time required for loading and unloading may render air taxis less attractive for shorter trips, which could be more efficiently handled by ground transportation [

2]. To provide an effective multimodal air taxi service, combining ground modes for access and egress, operators must ensure minimal delays caused by waiting, boarding, and alighting to maintain a high standard of service and achieve significant reductions in travel time [

3].

This study aims to provide a thorough assessment of the potential for UAM and broader AAM services in Illinois, examining both opportunities and challenges related to mobility, economic development, and infrastructure integration, focusing primarily on passenger travel. It includes identifying and evaluating technological advancements, with a detailed analysis of relevant application domains and use cases specific to Illinois, as well as the potential impacts and challenges associated with AAM deployment. The findings intend to inform policy considerations and guide the future development of AAM, while identifying areas where regulatory intervention may be necessary.

The main research questions that this work attempts to address are the following:

How can the State of Illinois identify and quantify the potential for AAM services in terms of passenger transportation, and the opportunities it might provide for mobility and economic development in the state?

What combination of travel demand modeling and aviation analysis methods can be employed to estimate AAM opportunities and challenges?

Which are the initial and main steps towards a regulatory framework that can sufficiently cover AAM operations within the State of Illinois, while integrating emerging federal regulations?

The overarching goal of this study is to conduct a comprehensive feasibility assessment of AAM deployment in Illinois, providing state transportation authorities with evidence-based insights to inform strategic planning and policy development. Rather than advocating for a specific service model or prioritizing particular applications, this research adopts an evaluative approach that systematically examines AAM across multiple dimensions to determine whether, how, and under what conditions AAM could be viably integrated into Illinois’s transportation ecosystem.

The analysis encompasses three interconnected objectives. First, the potential market demand and economic viability of AAM services in Illinois are being assessed, identifying which use cases demonstrate the most promising feasibility given current technological and economic constraints. Second, how AAM integration would affect existing ground transportation systems is being analyzed, via quantifying the potential impacts on traffic patterns, mode choice behavior, and multimodal connectivity to understand both the beneficial and adverse effects on current infrastructure. Third, the broader societal implications, including infrastructure requirements, regulatory frameworks, economic development opportunities, and accessibility considerations, are being studied, with the recognition that successful AAM deployment depends on addressing systemic challenges beyond purely technical or economic factors.

This multi-dimensional approach reflects the reality that AAM represents not merely a new transportation option, but a complex sociotechnical system requiring the coordinated consideration of technological capabilities, market dynamics, infrastructure investments, regulatory frameworks, and societal impacts. The study’s purpose is, therefore, to provide decision-makers with a holistic assessment that identifies the most viable pathways for AAM development while highlighting critical barriers and policy needs that must be addressed for successful implementation. By examining these dimensions comprehensively, this work establishes a foundation for informed policy decisions regarding whether and how to pursue AAM development in the state.

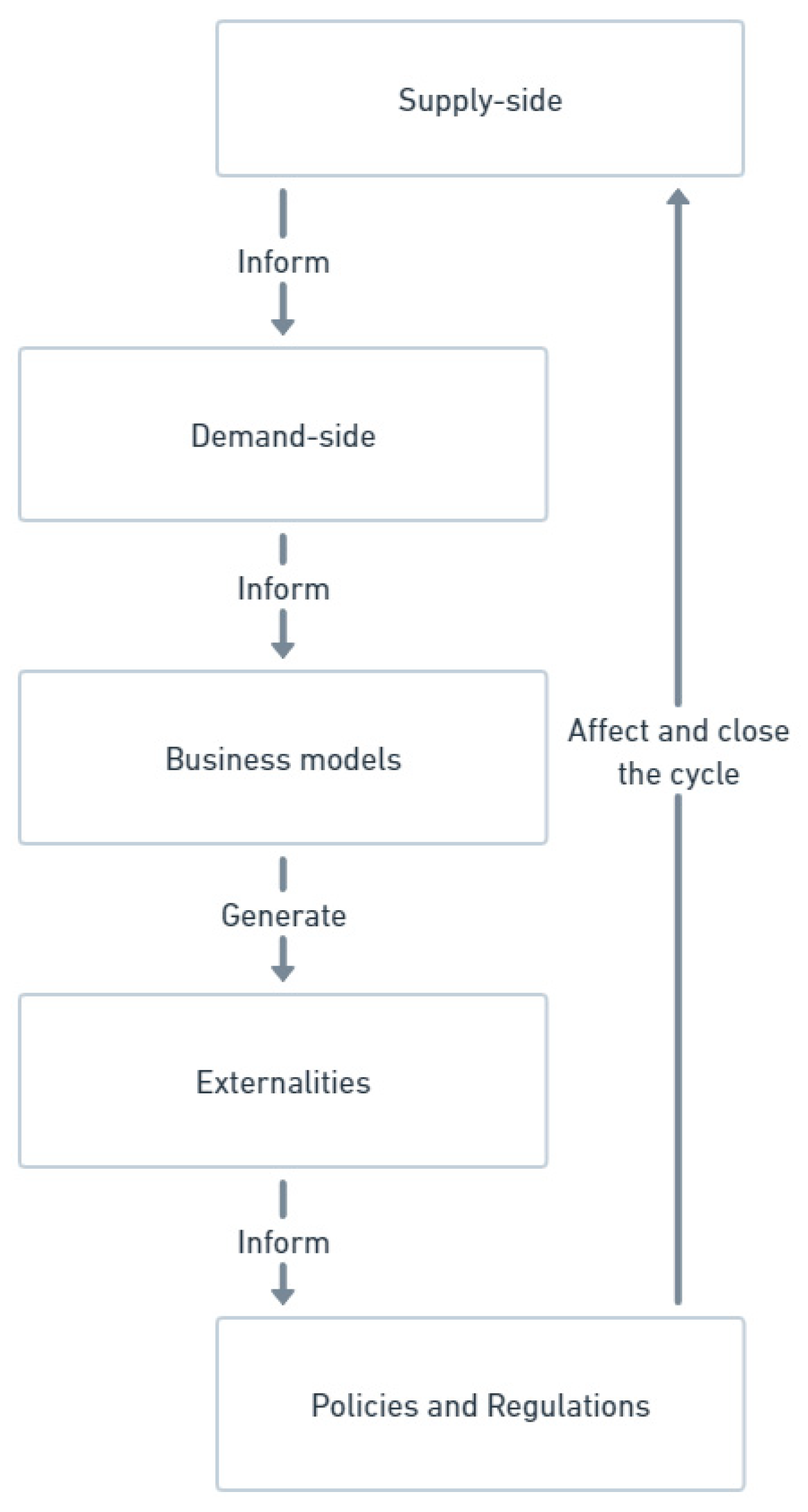

Figure 1 presents the workflow through the considered task areas, while

Figure 2 below summarizes the developed framework that combined qualitative and quantitative analyses to provide a holistic and collective understanding of AAM and UAM in Illinois.

This work builds upon a comprehensive assessment of AAM operations [

4], which was conducted for the Illinois Department of Transportation (IDOT) by members of the author team, among other collaborators. The existing AAM literature was reviewed across multiple dimensions, including demand estimation methodologies, operational concepts, infrastructure requirements, regulatory frameworks, use case applications (passenger transport, cargo delivery, agriculture, and emergency services), and societal and environmental impacts. The present study focuses on specific dimensions, drawing from and extending the demand estimation framework established in that broader assessment.

Studying the demand potential and understanding its implications for AAM are essential to accurately determine the possible scope and scale of AAM operations. With limited existing services resembling AAM, demand estimation is challenging. Common approaches involve either comparing AAM to similar services [

2,

5,

6,

7,

8] or conducting surveys of potential AAM users [

9,

10,

11]. Demand estimates vary, with studies projecting hundreds of daily operations to potentially serving tens of thousands of people within an urban setting [

7,

12].

Interest in potential UAM services has increased substantially in recent years, particularly in terms of personalized passenger air travel applications. This trend is underscored by the involvement of major ride-hailing firms exploring entry into the sector, as highlighted in several studies [

3,

13]. Surveys of prospective users aim to capture preferences, behaviors, and decision-making factors. In the early stages, per-mile air taxi operating costs are expected to be closer to those of a limousine or helicopter, and considerably higher than ground taxis [

1]. The U.S. market was estimated to face a demand of approximately 82,000 passengers daily (55,000 flights), supported by roughly 4000 aircraft. If challenges related to weather, time-of-day, capacity, and infrastructure were addressed in the long term, demand could reach higher volumes of passengers daily, requiring nearly 700,000 aircraft [

14,

15]. Challenges highlighted include noise concerns, airspace restrictions, and competition from telecommuting.

The air ambulance market, already utilizing helicopter technology, also shows potential for AAM. Bulusu and Sengupta [

2] found eVTOL air ambulances to have similar costs (

$11,200) to existing helicopters (

$12,500) per trip. However, a major constraint for eVTOL aircraft is battery recharge time, which is significantly longer than refueling rotary-wing aircraft, reducing aircraft availability. Hybrid vehicles, battery swapping, or faster charging times are suggested as solutions to improve turnaround and efficiency.

2. Methodological Framework

This section examines AAM applications relevant to Illinois across two broad categories: passenger transportation services (air taxis for daily commuting, airport access, and regional travel) and functional applications (agriculture, package delivery, emergency response, and infrastructure inspection). The analysis begins with an overview of functional applications before focusing primarily on passenger air taxi demand estimation, which represents the most commercially significant near-term use case.

2.1. Overview of AAM Applications in Illinois

Multiple AAM applications and use cases have been identified for use in the State of Illinois (

Figure 3). In agricultural contexts, low-altitude UAV operations promise to improve farm management through crop health monitoring, livestock observation, irrigation systems oversight, and more precise pesticide distribution, thereby lowering operational expenses and boosting productivity. UAV-based parcel delivery could optimize logistics operations for packages under 5–10 pounds, though current battery technology limits payload capacity and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulations restrict operations during precipitation, high winds (>25 mph), and low visibility conditions, which are common during Illinois winters. Emergency AAM applications are positioned to improve healthcare access through expedited medical transportation, offering particular advantages during severe weather events and flooding scenarios, with potential expansions encompassing automated patient transport and organ transplant conveyance. UAVs are additionally anticipated for infrastructure inspection applications, offering risk reduction, temporal efficiency, and cost advantages compared to conventional inspection approaches.

2.2. Air Taxi Demand Estimation Framework

Regarding air taxi operations, three principal trip categories require demand estimation: inter-regional air taxi journeys, airport access/egress trips, and daily commuting patterns. Extended daily commutes are expected to represent a larger share of air taxi demand, given their frequency, as time reductions from air taxis can compete effectively against surface transportation. Research indicates that below specific ground transportation travel duration thresholds (typically journeys exceeding 30 min, or more precisely, trips within 50–55 min), air taxi operations would likely prove economically unviable due to comparatively elevated costs and proportionally modest travel time reductions [

16]. Prior research has applied diverse methodologies for estimating air taxi demand from such journeys, generally emphasizing travel time reductions and cost competitiveness [

7,

17,

18].

The methodology builds on Goyal et al.’s [

1] framework, using 2022 National Household Travel Survey (NHTS) data to capture Illinois-specific travel patterns and demographic characteristics. Through the comparison of travel characteristics and assumed air taxi service parameters against existing surface transportation modes, a logistic mode choice framework was applied using variable coefficients obtained from the estimated logistic models of the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP) [

19]. Unconstrained demand projections were first derived and subsequently adjusted through the application of the willingness-to-pay constraint. Supply-side network constraints were subsequently incorporated with unconstrained demand estimates. Critical variables including precise AAM service pricing, average aircraft cruise velocity, vertiport waiting durations, and vertiport access/egress times remain undefined yet directly affect air mobility service levels. Assumed value ranges for these variables were established (

Table 1) and applied throughout the demand estimation methodology.

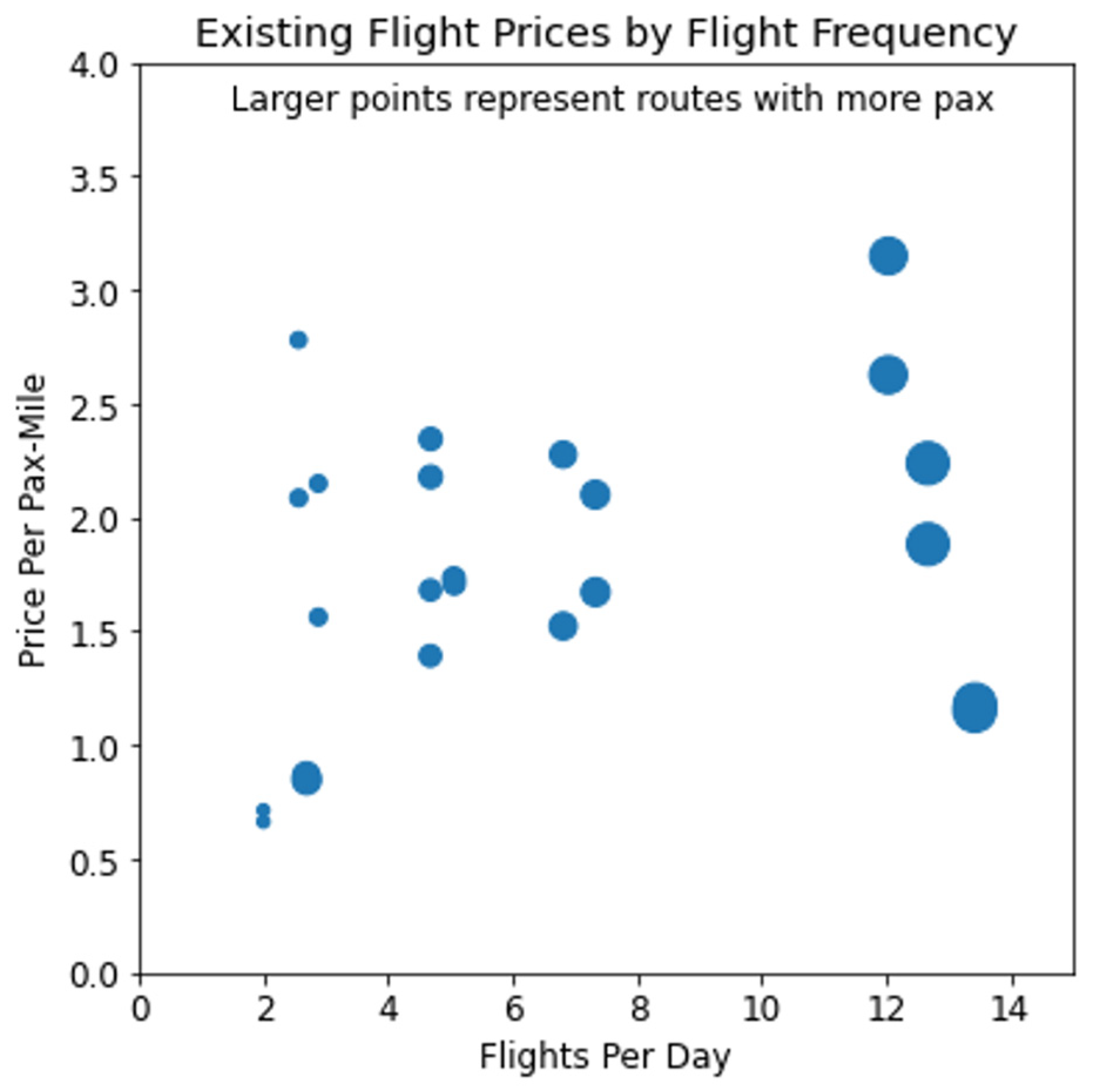

Air taxi pricing was based on estimated per passenger-mile costs. Cost values were inflation-adjusted from Goyal et al. [

1] 2018 baseline to 2025 USD for consistency. Aircraft average cruise velocities determined inter-vertiport travel durations, with the assumed speeds derived from prototype air taxi platforms currently under development [

20], accounting for reduced operational velocities during the departure and arrival phases. Wait times and access/egress times ranged from 5 to 15 min (Al Haddad et al. assumed five-minute average waiting [

21]), with access/egress times doubled to encompass both first and last mile distances.

Figure 4 depicts the travel time reductions for AAM aircraft, calculated by comparing existing surface transportation journeys to projected air taxi operations. Travel time savings were calculated for each individual trip record in the Illinois NHTS subsample, through direct comparison of ground transportation durations against estimated air taxi travel times. For each trip exceeding the 30 min viability threshold, the ground transportation travel time was taken directly from the NHTS-reported trip duration, while the air taxi travel time was calculated using the straight-line distance between the trip origin and destination coordinates, the assumed cruise speed from scenario-specific parameters, vertiport waiting time (5–15 min depending on scenario), and first/last mile ground travel to and from vertiports (i.e., access and egress times). Time savings exhibit geographic clustering due to urban density variations, corridor effects, and distance bands. High-density Chicago metropolitan trips show different patterns than rural, downstate journeys.

The analysis examined ground transportation-based journeys exceeding 30 min, considering that threshold for competitive air taxi viability reasons (based on [

16]). Within this segment, close to 90% of trips demonstrated potential travel time reductions when using air taxis. Median time savings for such journeys reached 25%, translating to 15 min or less for most trips, generally comparable to surface transportation durations. Additionally, a quarter of long-distance trips achieved at least a 50% travel time reduction, identifying a market segment where air taxi operations offer substantial time savings and enhanced user appeal. For time valuation,

$20.60/h was applied (adjusted to 2025 U.S. dollars from the baseline values in [

22,

23]), and it was also used to evaluate potential UAM users’ willingness-to-pay, combined with per-trip time savings.

Five scenarios were constructed by combining operational parameter assumptions with network size variations. Three primary scenarios—pessimistic (low-demand), intermediate, and optimistic (best-case)—represent different combinations of cost, speed, and access time parameters from

Table 1. Additionally, two network-specific scenarios vary vertiport accessibility: the small network assumes limited vertiport coverage (30% of trips accessible), while the large network assumes extensive coverage (70% of trips accessible), with both using intermediate operational parameters. Projected daily demand in the Chicago metropolitan area spans from 2800 trips (0.007% mode share) in the low-demand scenario to 260,000 trips (0.65%) in the best-case scenario. The intermediate case projects 44,000 daily trips (0.11%), while small and large network scenarios estimate 16,500 (0.04%) and 125,000 (0.31%) daily trips, respectively. The number of scenarios was determined based on the combination of key operational variables (cost per passenger mile, aircraft speed, and vertiport accessibility) that strongly influence AAM demand. These three parameters were each assigned representative pessimistic, intermediate, and optimistic values drawn from existing literature and prototype performance data, producing a set of scenarios that captures the realistic operational spectrum between conservative and optimistic system assumptions.

2.3. Infrastructure and Airspace Integration Requirements

Projected unconstrained demand for day-to-day AAM trips, exhibits considerable variation, spanning from several thousand to tens of thousands of daily trips. Notably, the highest demand projections derive from optimistic scenarios assuming brief wait durations, conveniently located vertiports, and competitive pricing structures. Beyond demand estimation, successful air taxi deployment faces operational challenges and will necessitate substantial modifications to existing aviation infrastructure and protocols. Integrating high-frequency, low-altitude AAM operations into airspace currently managed for conventional commercial and private aviation will require extensive air traffic control system adaptations, potentially including automated traffic management platforms specifically engineered for urban air mobility contexts. Furthermore, the on-demand characteristics of air taxi operations will demand novel dispatch protocols fundamentally different from scheduled commercial aviation procedures, merging traditional air traffic management elements with dynamic, real-time routing characteristics of surface-based ride-hailing platforms. These operational complexities introduce additional regulatory and coordination challenges requiring resolution for successful AAM deployment.

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), commonly termed drones, constitute a distinct aircraft system category. While this study primarily emphasizes passenger-focused AAM operations utilizing piloted eVTOL and STOL aircraft, UAVs remain relevant to the broader AAM ecosystem, particularly for small-package delivery, infrastructure inspection, and emergency response applications where onboard human presence proves unnecessary. Regulatory and airspace management considerations for UAV operations, though distinct from crewed aircraft requirements, remain pertinent to comprehensive AAM integration planning.

2.4. Limitations and Key Assumptions

The limitations of this study mostly stem from various uncertainties and areas requiring additional research, along with the absence of existing operational data and well-established regulations. These areas include the demand side, Air Traffic Management (ATM), and potential business models related to AAM operations. There are different unknowns that can directly influence the level of service of AAM operations, including variables such as the cost of the service, average aircraft operating speed, and the access, wait, and egress times at designated AAM infrastructures (e.g., vertiports/skyports [

1]).

On the demand side, understanding user perceptions, adoption patterns, and the factors influencing these behaviors is important, yet these factors are not considered in this work. These include identifying potential barriers to adoption and outlining clear pathways for integrating AAM aircraft and its associated infrastructure into existing urban networks. An additional operational constraint for air taxi services involves luggage and cargo accommodation. Current eVTOL designs typically feature limited passenger capacity (4–6 seats in most configurations) with restricted cargo space. This constraint can have implications for business model viability; if a four-passenger vehicle must operate with only two or three passengers to allow for baggage, the per-passenger cost increases proportionally, potentially pushing prices beyond market acceptance thresholds.

In the ATM realm, it is paramount to examine how airspace congestion evolves under various management and routing strategies. Building on existing work on airspace congestion [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28], a thorough exploration of airspace congestability is essential. Evaluating the scalability and adaptability of ATM strategies as AAM and UAM expand is essential. In this work, air congestion was not considered, along with potential ground congestion, due to the introduction of an UAM service in an urban setting. The notion of induced demand, i.e., the increase in demand due to the introduction of UAM, is also important.

Assumptions stemming from the existing regulatory framework around AAM operations were also made. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is envisioned to be the primary regulatory body responsible for certifying, regulating, and providing air navigation services for AAM operations, as it currently does for commercial aviation, and other existing aviation operations. Various concepts of operation documents have been published by the FAA [

29,

30,

31,

32], and while these are not formal policy statements they are interconnected and provide valuable insights into the evolving perspective on AAM/UAM operations and their assessment. Developed collaboratively by the FAA, NASA, and industry stakeholders, these documents outline conceptual elements such as aircraft, infrastructure, supporting systems, air traffic operations, and their integration into the National Airspace System (NAS).

4. Discussion

The demand estimates in

Section 3 establish baseline market potential, but several factors will critically influence whether and how AAM materializes in Illinois. This section discusses induced demand effects, ground transportation impacts, parameter sensitivities, regulatory alignment needs, and equity considerations that shape AAM’s practical feasibility and societal implications.

4.1. Induced Demand Effects

The introduction of AAM could stimulate changes in existing activity patterns and demand flows. For example, additional travel patterns and trips could be added to the network (i.e., induced demand), and reduced travel times between Chicago’s central business district and distant suburban areas could potentially enable commuters to accept employment opportunities previously considered infeasible. Reduced travel time costs could increase trip frequency for existing origin–destination pairs. For example, business travelers might conduct more frequent in-person meetings with travel times of a full trip declining from 3 to 4 h by car (e.g., Chicago-to-Springfield or Chicago-to-Peoria) to under 90 min via AAM. Illinois’s polycentric structure, with Springfield serving as the state capital and numerous regional employment centers across central Illinois, creates potential for frequency-based induced demand on inter-regional routes.

Quantifying this effect for Illinois requires estimating the potential induced demand from reduced travel times. The transportation economics literature regarding induced demand from highway improvements and speed increases suggests that time savings often generate additional trip-making, with induced demand effects typically ranging from 10% to 50% of the direct capacity benefit, depending on market conditions and network characteristics [

45]. Given AAM’s premium pricing and limited initial accessibility, induced demand effects are likely to fall toward the lower end of this range. Applying moderate assumptions to the 87.6% of AAM demand concentrated in Chicago suggests induced demand could add 10–25% to the mode-shift-based estimates in

Section 3.1.1, translating to approximately 6400–16,000 additional daily trips in intermediate scenarios. However, this represents a preliminary estimate with substantial uncertainty, as empirical evidence specific to air mobility induced demand does not yet exist.

4.2. Ground Transportation Impacts from Vertiport Access

AAM operations generate ground transportation trips for vertiport access and egress that could partially or fully offset congestion benefits from mode shift away from automobile travel. The magnitude of this effect depends critically on vertiport location and access mode distribution. Vertiports located in the central business district of the Chicago Area (the Loop and Near North Side) would concentrate access/egress trips in already-congested downtown areas. If 125,000 daily AAM passengers (large network scenario from

Section 2) generate 250,000 access/egress trips, with a reasonable assumption that 70% of these trips will use ride-hailing or private vehicles, this adds approximately 175,000 vehicle trips to the downtown Chicago road network. These trips would exacerbate peak period congestion on major arterials and streets, potentially offsetting much of the congestion relief from reduced automobile commuting. Vertiports at existing commuter rail stations or near major suburban employment centers would distribute access/egress trips across the regional network, likely producing lower marginal congestion impacts, since suburban roadway networks generally operate below capacity outside immediate freeway interchange areas. However, this strategy compromises door-to-door travel time benefits for downtown-oriented trips, reducing AAM attractiveness and thus limiting mode shift and congestion benefits. Vertiports integrated with major public transit stations could facilitate transit-based access, reducing vehicle trip generation.

The above findings contrast with simplified assumptions that AAM relieves congestion. The net effect depends critically on (i) vertiport location strategy and resulting access mode distribution, (ii) whether AAM primarily substitutes for automobile trips or transit/other modes, (iii) the geographic distribution of vertiport access/egress trips relative to existing congestion hotspots, and (iv) the induced demand magnitude.

4.3. Demand Estimation Parameters Discussion

Demand estimates rely on assumed operational parameters whose values remain uncertain in the absence of existing and mature AAM markets. Three categories of assumed parameters drive demand estimation outcomes: cost parameters (per passenger mile pricing), operational performance parameters (aircraft cruise speed and vertiport throughput capacity), and user experience parameters (waiting times and access/egress times). Cost per passenger mile exhibits the strongest influence on demand across all trip categories, representing the binding constraint on AAM adoption in Illinois. For daily air taxi trips, cost varying produces demand estimates ranging from approximately 260,000 trips daily (0.65% of mode share) to 2800 trips daily (0.01% of mode share), a 95-fold variation. Airport trips demonstrate similar cost elasticity, with mode shares ranging from 1.11% to 10.26% across the cost scenarios. Notably, even optimistic cost assumptions yield moderate modal shares, suggesting substantial cost reductions below current industry projections would be necessary for mass market adoption. The relationship between cost and demand is non-linear. Demand remains relatively stable at lower cost levels before declining sharply as the cost increases, indicating a threshold beyond which AAM becomes prohibitively expensive for most travelers.

Aircraft cruise speed variations produce modest demand effects compared to cost. Increasing speed from 100 to 180 mph improves time savings, but demand increases only approximately 2–3 fold, since ground access/egress times remain constant regardless of cruise speed, diluting the benefit of faster flight times, and many Illinois trips already achieve substantial time savings, even at lower speeds, due to ground traffic congestion. Regional air taxi routes show particularly weak sensitivity to speed variations because most routes are short (under 150 miles), resulting in flight time differences in only 10–20 min across the speed range. This explains why regional air taxi demand remains limited even under optimistic assumptions—the absolute time savings are insufficient to justify premium pricing regardless of aircraft performance.

Waiting and access/egress times demonstrate moderate sensitivity. Reducing combined waiting and access/egress times from 60 min (pessimistic scenario: 15 min wait + 30 min access + 15 min egress) to 20 min (optimistic scenario: 5 min wait + 10 min access + 5 min egress) increases demand approximately 4–7 fold for daily air taxi trips. Supply constraint parameters create additional uncertainty in achievable demand. Vertiport network size (modeled at 30%, 50%, and 70% trip accessibility representing small, medium, and large networks) directly scales achievable demand proportionally—a small network captures only 30% of unconstrained demand regardless of cost or performance assumptions. Vertiport throughput influences peak period operations most critically. Given that most of Illinois’s potential demand for AAM concentrates in Chicago, and peak period demand reaches double off-peak levels, vertiport capacity constraints could create bottlenecks even if demand materializes. A 25 vertiport Chicago network operating at 60 operations per hour per facility could process 4500 passengers hourly, or approximately 18,000 passengers during a four-hour morning peak, which is potentially insufficient for best-case demand scenarios (260,000 daily trips implies approximately 106,500 during combined morning and evening peaks, or 26,500 per four-hour peak period).

4.4. Regulatory Context and Considerations for Illinois

The FAA continues to evolve its AAM operational and regulatory framework, and Illinois policy should incorporate flexibility to align with future federal regulatory developments. Given uncertain AAM and UAM demand trajectories and adoption patterns, Illinois should develop adaptable policy frameworks accommodating variable demand scenarios. Integrating AAM aircraft into existing aviation networks and systems represents a potentially significant strategic approach. Furthermore, the Illinois Aviation System Plan (IASP) should undergo comprehensive updates to fully incorporate such aircraft operations, transitioning from treating these as speculative future possibilities to actively accommodating their operational requirements and supporting infrastructure. While the IASP comprehensively addresses the state’s aviation system, AAM operations receive only limited mention in selected sections. Current treatment includes elements such as AAM vehicle technology, infrastructure needs, and prospective air traffic scenarios requiring thorough evaluation.

Different state-level policy measures could be considered to facilitate AAM and its smooth integration in Illinois. First, the state should establish clear guidelines for vertiport location and zoning requirements, providing municipalities with standardized frameworks that balance local land-use authority with statewide connectivity objectives. This would ensure consistency across jurisdictions while supporting equitable access to AAM services. Second, Illinois could develop targeted incentive programs to attract AAM manufacturers, operators, and supporting industries to the state. Such initiatives may include tax incentives for vertiport development in designated zones, workforce training programs aligned with AAM industry skill needs, and research partnerships between state universities and AAM companies to promote innovation and job creation.

In addition, the state should create protocols for AAM involvement in emergency medical services, disaster response, and public safety operations. These protocols would define operational authorities, liability frameworks, and coordination mechanisms among key agencies such as the Illinois Emergency Management Agency and the Illinois Department of Public Health, ensuring the safe and efficient integration of AAM assets in critical response scenarios. IDOT should also incorporate AAM considerations into regional transportation planning processes to ensure alignment with existing surface transportation investments and public transit operations. Metropolitan planning organizations should be directed to evaluate AAM impacts and opportunities within long-range transportation plans to achieve a cohesive multimodal network.

Expanding the IASP to address system-wide vulnerabilities represents another key priority. Illinois should proactively identify and mitigate infrastructure vulnerabilities such as cybersecurity risks, electrical grid reliability, and natural disaster resilience. This includes establishing cybersecurity standards for AAM operations that exceed federal minimums, developing grid resilience strategies for vertiport networks, and implementing weather contingency protocols tailored to Illinois’s climate conditions.

Finally, Illinois should adopt a phased regulatory approach to AAM deployment. Initial efforts could focus on demonstration projects within controlled environments, such as designated corridors between O’Hare International Airport and downtown Chicago. These pilot projects would then expand to limited commercial operations in high-demand urban markets, with statewide deployment proceeding only after the technology demonstrates consistent safety, reliability, and operational performance.

4.5. Equity and Accessibility Considerations

The projected cost structure of air taxi services, ranging from $5.30 to $11.20 per passenger mile, raises significant equity concerns, at least during the first years of UAM operations. A typical 20-mile trip would cost $106–$224 for an air taxi service compared to $15–$45 for ride-hailing, or negligible marginal cost for personal vehicle users, effectively limiting access to high-income travelers. This premium pricing structure means AAM would function primarily as a luxury service rather than a broad mobility solution, with limited benefits for transportation-disadvantaged populations who face the greatest mobility challenges. Future policy discussions should consider whether public investments in AAM infrastructure can be justified given this limited accessibility, or whether alternative pricing mechanisms (subsidies, shared-ride models) could broaden access.

Environmental implications of AAM deployment require careful consideration. While eVTOL aircraft produce zero direct emissions, offering advantages over helicopter services, their full lifecycle environmental impact depends on electricity grid composition. Noise represents a potentially more immediate concern; although eVTOL aircraft are projected to be significantly quieter than helicopters (60–70 dB versus 80–90 dB at 500 feet [

4]), concentrated vertiport operations could generate community opposition similar to heliport noise complaints. The projected air taxi demand of several thousand to tens of thousands of daily operations represents a significant increase in low-altitude aircraft activity, suggesting noise impacts could become a significant barrier to public acceptance and regulatory approval.

5. Conclusions

This section synthesizes the study’s key findings, discusses their implications for AAM deployment in Illinois, acknowledges analytical limitations, and identifies priority areas for future research.

5.1. Summary of Findings

This study evaluated the potential for Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) and Urban Air Mobility (UAM) services in Illinois through an analytical framework addressing demand estimation, business model viability, transportation system impacts, and regulatory requirements. The findings reveal that AAM faces significant market constraints that limit near-term deployment viability. AAM services in Illinois would serve a narrow market segment, namely business travelers in the Chicago metropolitan area willing to pay premium fares for time savings on longer commutes. The analysis identifies Chicago as capturing 87.6% of projected air taxi demand, driven by substantial trip volumes and congestion-induced delays that create favorable conditions for time-competitive operations. Beyond Chicago, central Illinois represents only 10% of projected demand, with the St. Louis region accounting for 2.4%, indicating its limited viability outside the primary metropolitan area. Within viable trip segments, air taxi services show the strongest potential for work-related trips exceeding 30 min of ground travel time, particularly with regard to the 22% of longer trips achieving at least 50% travel time reduction. Temporal demand patterns concentrate heavily during peak commute hours (6:00–10:00 a.m. and 4:00–6:00 p.m.), with volumes reaching double or more compared to off-peak periods, creating operational challenges for fleet utilization and infrastructure efficiency.

Cost represents the dominant barrier to AAM adoption, exhibiting 3–4 times greater influence on mode choice than access time and 5–6 times greater sensitivity than aircraft speed. Under pessimistic but realistic cost scenarios ($6.00–$9.00 per passenger mile, 2025 USD), UAM captures only 0.76–2.79% of mode share—well below the 5% threshold typically associated with sustainable transportation service viability. Even optimistic cost projections ($3.00 per passenger mile) yield only 10.67% of mode share, indicating that substantial cost reductions beyond current industry projections would be necessary for mass market adoption. The cost–demand relationship exhibits strong non-linearity, with the steepest decline occurring between $3.00 and $4.50 per passenger mile, suggesting a critical threshold beyond which AAM becomes prohibitively expensive for most travelers. These findings indicate that AAM would function primarily as a premium service accessible to high-income travelers (likely top 10–20% of income distribution) and business users with employer reimbursement, raising questions about public investment justification given limited accessibility benefits.

While cost dominates adoption decisions, other operational factors demonstrate secondary but meaningful effects. Out-of-vehicle time (waiting and access/egress) shows moderate sensitivity, with combined times increasing from 20 to 60 min, reducing mode share by approximately 50%. This underscores the critical importance of vertiport network density and convenient locations that minimize ground access times. In contrast, aircraft cruise speed variations (100–180 mph) produce surprisingly weak effects, improving mode share only by 44% in relative terms (4.25% to 6.12% absolute) because ground-based access and egress times constitute significant portions of total trip time regardless of flight speed. These patterns indicate that infrastructure planning and network design prove nearly as important as aircraft technological performance for achieving market viability.

Given the current cost projections and limited market potential, Illinois should adopt a phased, evidence-based approach to AAM rather than pursuing immediate large-scale infrastructure investments. Deployment should proceed only when specific market maturity indicators are demonstrated: (i) eVTOL operational safety records established through at least 1 million flight hours across multiple markets; (ii) FAA regulatory frameworks finalized for routine commercial operations beyond experimental authorizations; (iii) business models proven financially sustainable without requiring excessive public subsidization; and (iv) operational costs declining to the $4.00–$6.00 per passenger mile range where mode share projections suggest potential viability. Until these conditions materialize, Illinois resources would likely yield greater mobility benefits through investments in transit improvements, first/last mile connectivity enhancement, and conventional congestion mitigation strategies that serve broader population segments.

Beyond direct mode shift effects, AAM integration presents complex secondary impacts requiring careful consideration. Induced demand from reduced travel times could add 10–25% to mode-shift-based projections, though substantial uncertainty surrounds these estimates given the absence of empirical air mobility data. Ground transportation impacts from vertiport access and egress trips could partially or fully offset congestion benefits, with effects depending critically on vertiport location strategies and resulting access mode distributions. Environmental considerations (including lifecycle emissions dependent on electricity grid composition and noise impacts from concentrated vertiport operations) require mitigation strategies to maintain community acceptance. Equity implications remain significant, as premium pricing structures would limit AAM primarily to affluent travelers, raising questions about public infrastructure investment priorities when transportation-disadvantaged populations derive minimal benefits.

5.2. Summary of Limitations

This study’s limitations stem primarily from uncertainties inherent to emerging AAM technology and the absence of operational data from mature markets. Key limitations are as follows. Critical operational parameters (including service costs, aircraft speeds, and vertiport access/wait/egress times) remain undefined, requiring assumed value ranges that influence demand projections. User perceptions, adoption patterns, and behavioral factors influencing AAM acceptance were not empirically assessed. A UAM service was modeled as uniformly available across all origin–destination pairs to isolate behavioral responses to service characteristics. This simplification produces upper-bound mode share estimates that overstate near-term achievable adoption, while existing vertiport networks would serve only subsets of OD pairs.

Airspace congestion under various air traffic management strategies was not modeled, despite being critical for evaluating system scalability. Ground congestion effects from vertiport access/egress trips and induced demand from AAM introduction receive limited quantitative treatment, though a qualitative analysis of these phenomena is provided. The framework assumes that the FAA will serve as the primary regulatory body for AAM certification and air navigation services, consistent with current aviation governance. However, actual regulatory frameworks remain under development, with the FAA concept of operation documents providing guidance but not constituting formal policy.

Current eVTOL designs feature limited passenger capacity (4–6 seats) with restricted cargo space due to battery weight constraints. Passenger baggage accommodation directly competes with seating capacity, potentially requiring reduced passenger loads that increase per-passenger costs.

These limitations indicate that demand estimates, particularly optimistic scenarios, should be interpreted as upper bounds rather than as precise forecasts, with actual market penetration dependent on technological maturation, cost reduction, infrastructure deployment, and regulatory framework development.

5.3. Future Steps

In the realm of AAM demand, conducting additional research is important for delving deeper into user perceptions and adoption patterns beyond the current study’s scope. Moreover, it is important to outline a clear path for integrating AAM into existing infrastructure. The identification of optimal vertiport locations balancing different objectives, such as accessibility to high-demand origin–destination pairs, minimization of ground access times, integration with existing transit infrastructure, avoidance of environmentally sensitive areas, and mitigation of noise impacts on residential communities, is another important dimension. Subsequent research will address two key areas not fully explored in this study: the operational impacts of AAM integration on existing airport infrastructure and procedures (the reader is directed to the study by Ahrenhold et al. [

46]), and the application of UAM and AAM services for airport ground access transportation [

47].

On the ATM side, enhancing current understanding of airspace congestion dynamics under various air management and routing strategies is critical. This includes analyzing how different air traffic management approaches affect airspace efficiency and safety, particularly their scalability and adaptability within the evolving urban air mobility ecosystem.

Furthermore, the business models associated with various verticals within the AAM domain require individual examination. Given the range of sectors, such as air taxis, agriculture, emergency services, package delivery, and others, the diversity in the business models needed for large-scale deployment needs to be acknowledged. A comprehensive evaluation of potential public–private arrangements and partnerships that can support the effective implementation and sustainability of these varied business models could also be beneficial.

Survey-based research with Illinois commuters should validate mode choice parameters for AAM services, assess willingness-to-pay distributions across income segments, and identify specific origin–destination corridors demonstrating the highest viability potential. Discrete choice experiments which systematically vary cost, travel time, access requirements, and service reliability to capture behavioral responses to AAM service attributes not observable in revealed preference data can also be insightful.