MiS-PoW: Mirror-Selected Non-Interactive Proof of Ownership for Cloud Storage

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Session bound and non-interactive challenges. We introduce MiS-PoW, which mirrors challenges on the client and the server. The protocol derives a common seed from the TLS exporter, a discretized time value, and a file identifier. The design removes extra round trips, prevents replay, and limits seed manipulation. The approach requires no change to the TLS trust model.

- Stratified sampling with zero knowledge enforcement. We design a stratified and duplicate-free selector that enforces coverage across partitions. The selector resists contiguous knowledge and near duplicate attacks. We provide clear bounds on success probability under partial knowledge and limited grinding. We realize the selector inside a STARK with simple constraints for range, count, and uniqueness.

- Privacy and scalability in practice. We build an implementation that fits existing TLS endpoints and standard ZK libraries. The verifier cost is independent of file size, and proof sizes remain modest. We also offer an analysis method and an evaluation plan that match large-scale cloud settings.

2. Related Work

2.1. Problem Statement and Motivation

2.2. Threat Model

- Soundness. Under PRF security and hash collision resistance, an adversary that does not know all challenged blocks succeeds with probabilityHere is the one shot success of the sampler. For independent knowledge we haveFor stratified sampling with partition sizes and quotas ,The bound is smaller when knowledge is contiguous. Choosing c so that gives bit soundness.

- Zero knowledge. The verifier learns nothing about F beyond and the acceptance bit. The STARK proves that indices come from through the specified PRF and rejection sampling, that indices are within range and pairwise distinct, that quotas hold, and that for each the relation is true without revealing .

- Unpredictability and anti replay. The seed binds the TLS transcript, the discretized time value , and and may include . Challenges are unpredictable before the handshake and are not reusable across connections or time windows.

- Deployability. The verifier work is for proof checks and quota and uniqueness checks. The cost does not depend on . The protocol adds no extra messages beyond standard HTTPS.

- Handshake discipline. By default, we assume TLS 1.3. The exporter is invoked only after a full handshake; 0-RTT is disabled. For session resumption (PSK + ECDHE), we rebind to the fresh transcript so that one session yields one seed (fresh exporter secret). In TLS 1.3, KeyUpdate rotates traffic keys only and does not affect the exporter secret; combined with the binding to the discretized window T, this prevents seed grinding within a window and replay across windows.

- Grinding control. The service enforces per user and per file rate limits to bound Q. The optional adds client entropy and prevents server bias of without extra interaction.

- Storage for ZK. stores or a Poseidon Merkle commitment so the proof can check openings efficiently. Operational dedup can continue to use .

- Blockization. The client and the server share the same deterministic block policy such as size B and alignment. A mismatch leads to rejection and does not leak content.

3. Scheme Design

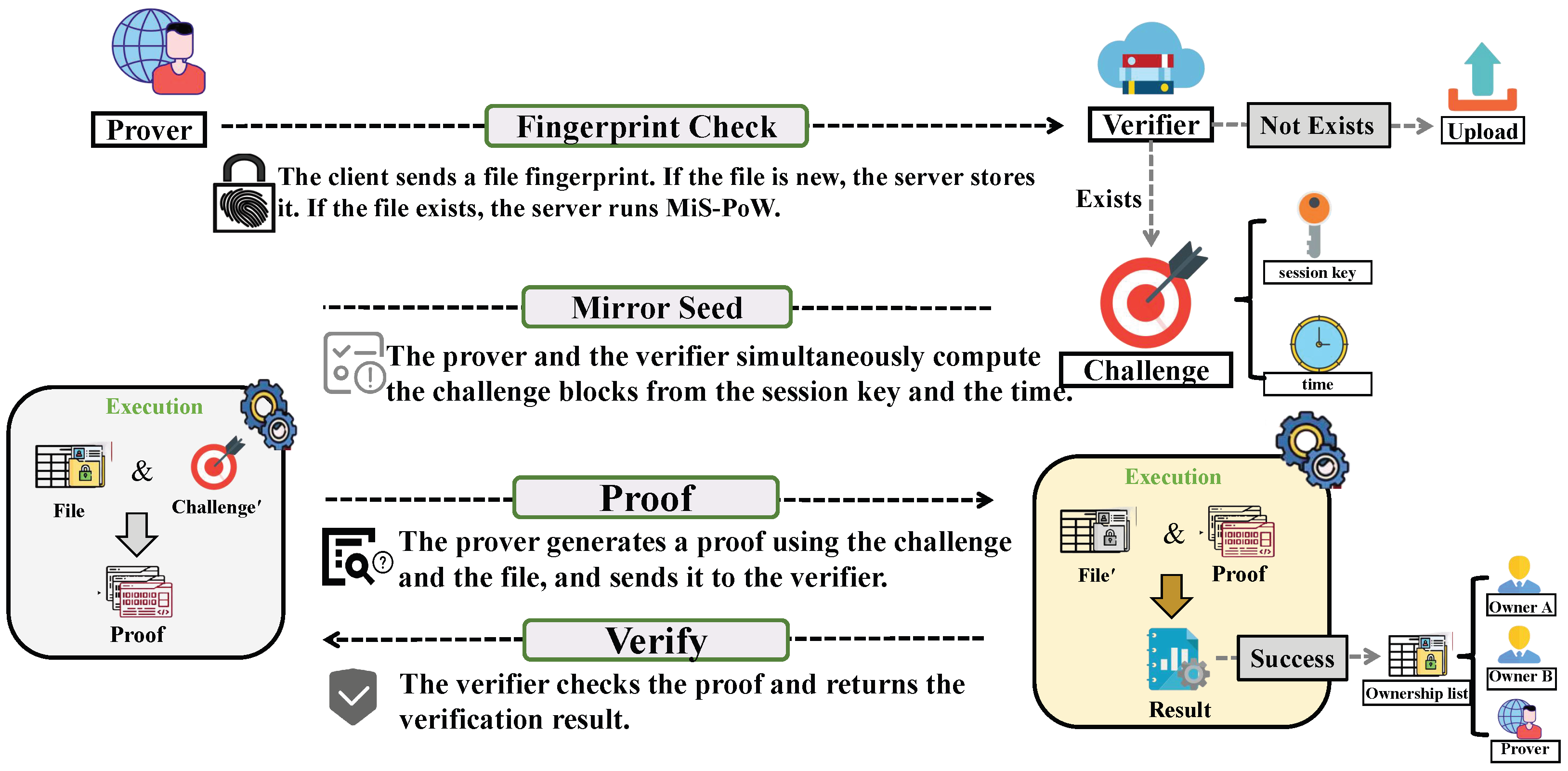

3.1. Workflow of MiS-PoW

- (1)

- Session-bound seed derivation.

- (2)

- Mirror challenge synthesis.

- (3)

- Prover computation (client side).

- (4)

- Verifier computation (server side).

- Public parameters and inputs.

3.2. Mirror-Selected Stratified Challenge Design

3.2.1. Partitioning and Quotas

3.2.2. Domain-Separated PRF Streams with De-Biasing

3.2.3. zk Integration (AIR Outline)

3.2.4. Theoretical Number of Challenges

- Parameter ranges and role of. We take as an upper bound on the adversary’s known fraction of F, as the challenge budget (number of sampled blocks), and as the security parameter in bits. Here is the base-2 logarithm; we use its monotonicity to solve for c, which gives the sizing rule (17). If the adversary has at most independent attempts (e.g., sessions or time windows), the total forging probability is bounded by , yielding ; setting recovers (17).

Refined Bound Under Stratification

Grinding Budget (Optional)

Practical Parameterization

- Small–medium files: (covers ).

- Large files/higher leakage risk: (covers ).

- Very large files/stricter security: (covers ).

- Summary. The mirror seed derived from session keys enforces a one-session/one-challenge policy with unpredictability and anti-replay, while stratified, duplicate-free sampling plus zk enforcement guarantees that verifying only a few dozen to a few hundred blocks achieves ≥80-bit soundness for typical leakage levels, justifying the compact deployment set .

3.3. zk-STARK Protocol Design

3.3.1. Public I/O and Witness

3.3.2. AIR: Simple, Readable Constraints

- (C1)

- Indices come from the seed.

- (C2)

- Quotas and uniqueness.

- (C3)

- Block ownership (know the content).

- (C4)

- A compact public digest.

3.3.3. Prover and Verifier Algorithms

3.3.4. Why This Is Secure and Scalable

3.3.5. Proof Object and Non-Interactive Transcript

4. Security Analysis

4.1. Unpredictability, Freshness, and Anti-Replay

4.2. Computational Integrity (Soundness)

4.3. Partial/Contiguous Knowledge and Grinding

4.4. Zero-Knowledge Privacy

- Summary.

5. Evaluations

5.1. Methodology

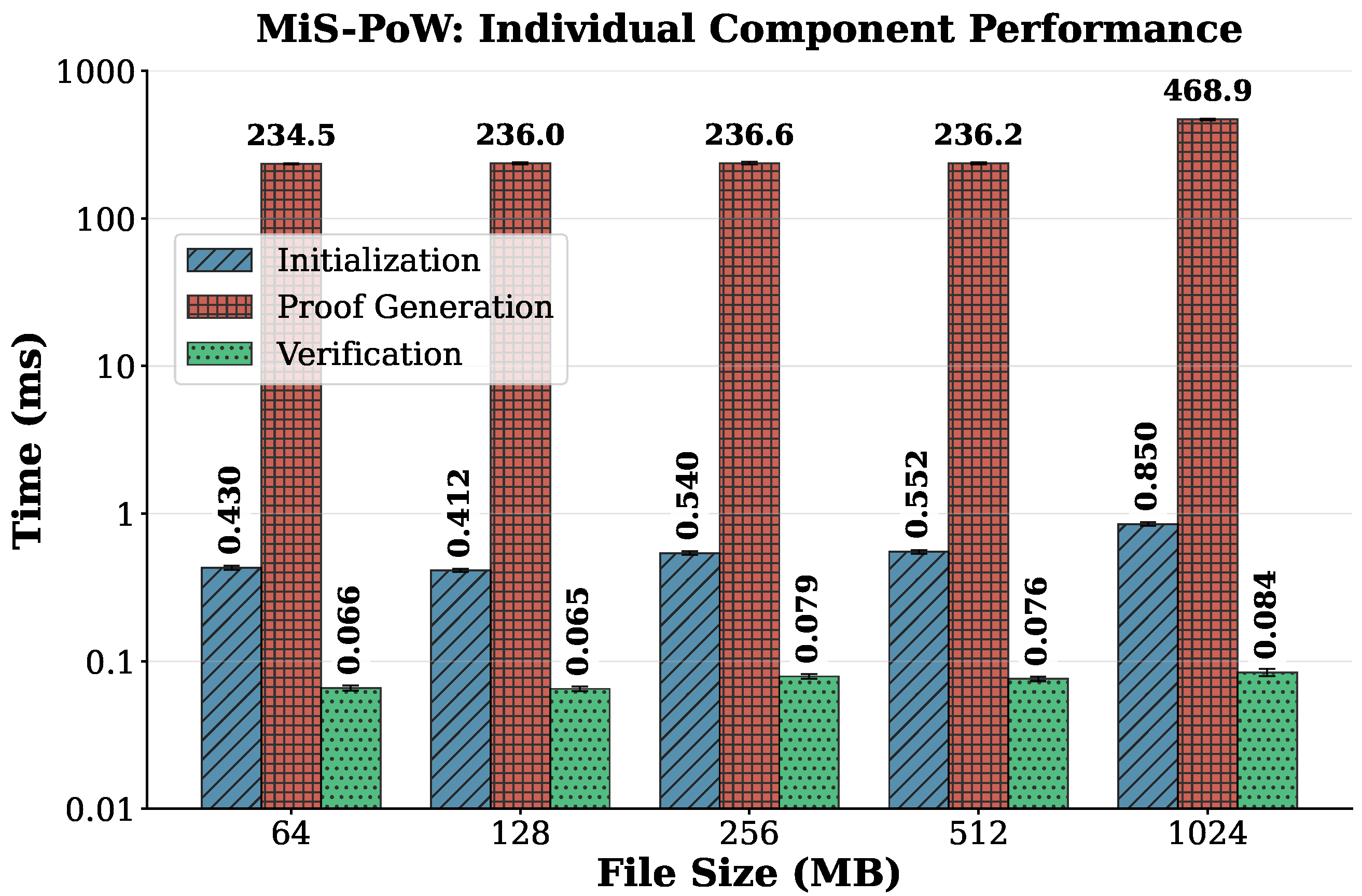

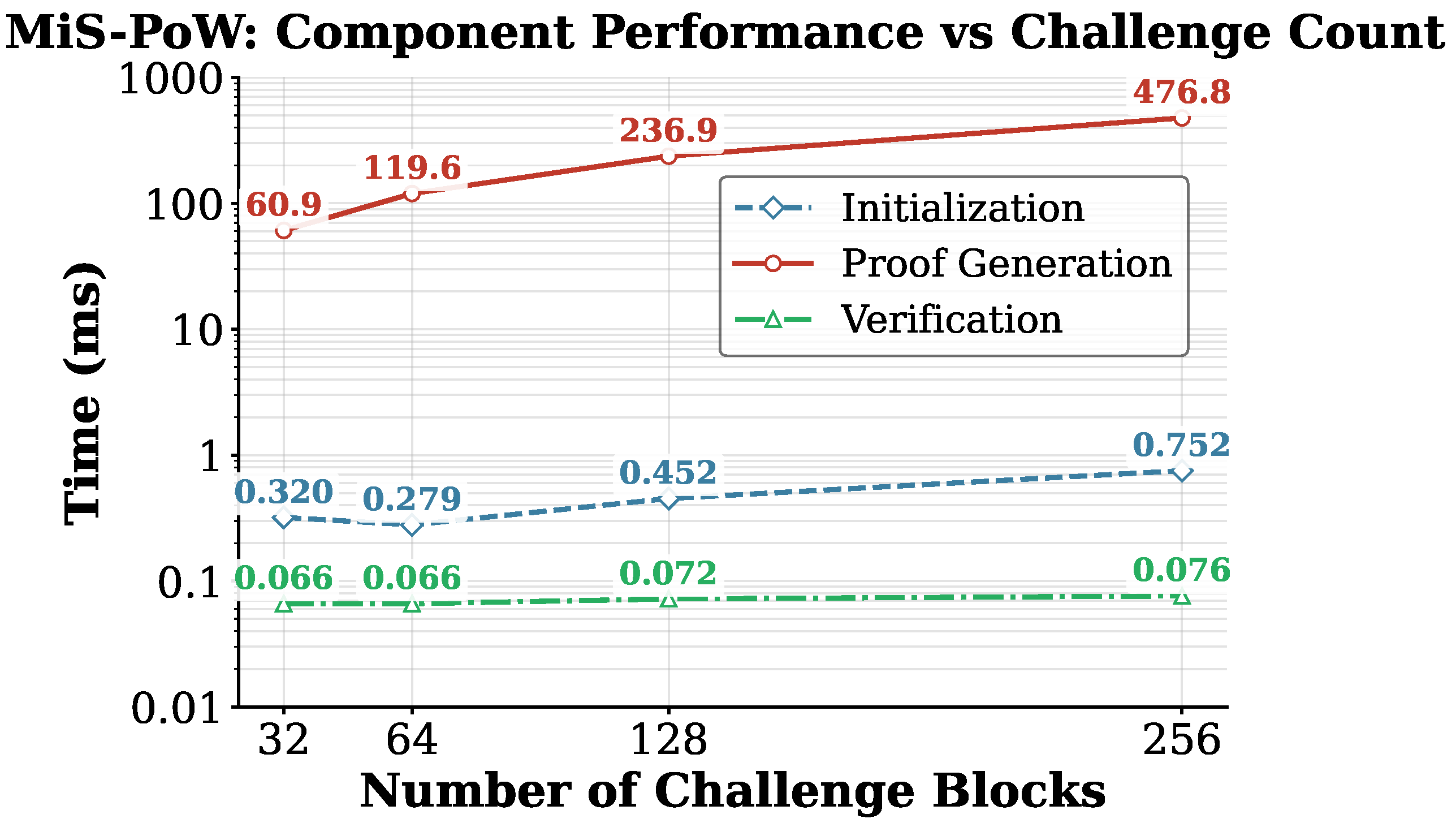

5.2. Computational Overhead Analysis

5.3. Efficiency and Performance Evaluation

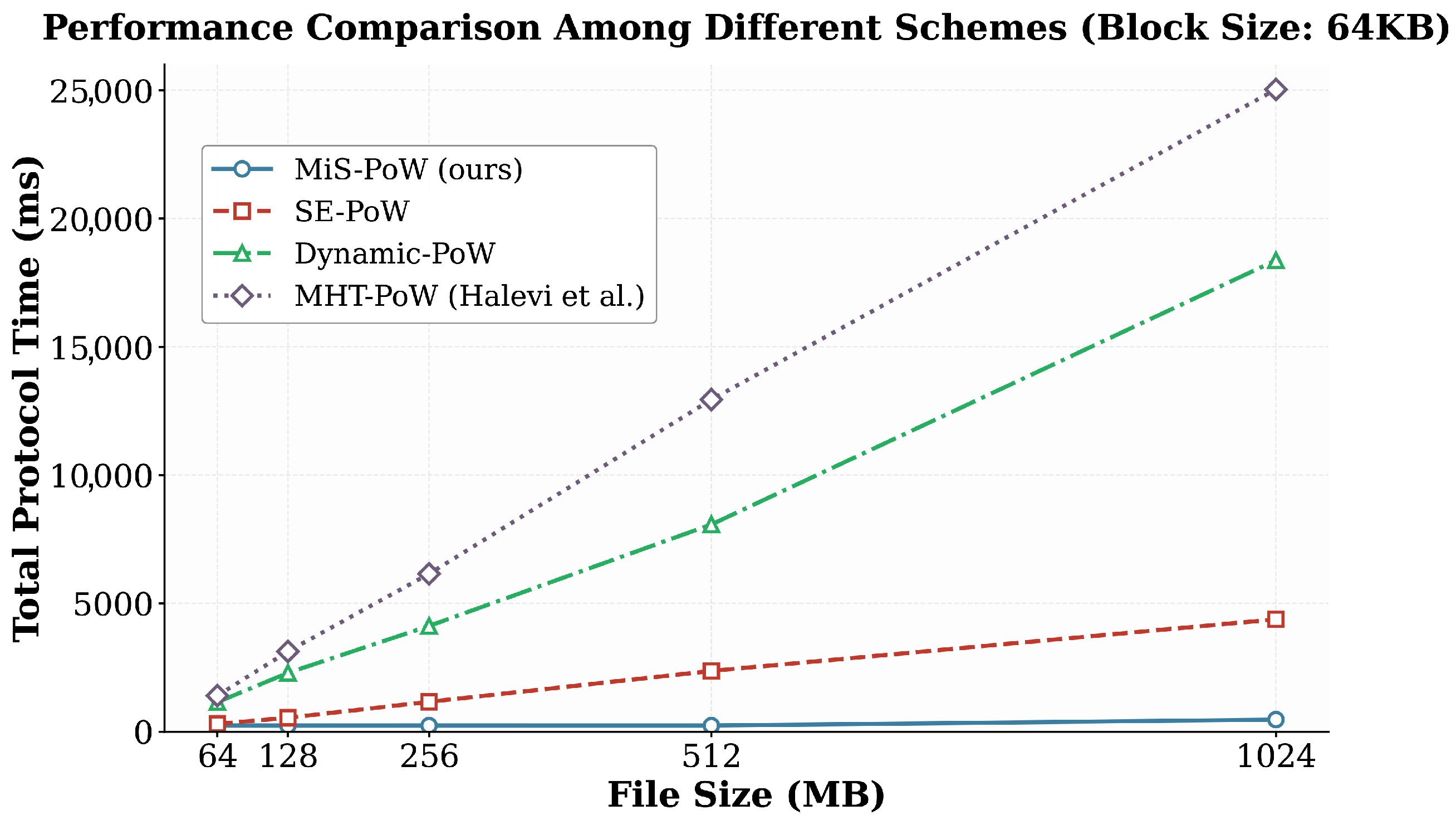

5.4. Comparison with Existing PoW Schemes

5.5. Discussion and Takeaways

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Jiang, X.; Liu, Q.; Steiner, I.M.; Herdrich, A.J.; Shu, K.; Das, R.; Cui, L.; Jiang, L. Libra: Clearing the cloud through dynamic memory bandwidth management. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Symposium on High-Performance Computer Architecture (HPCA), Virtual, 27 February–3 March 2021; pp. 815–826. [Google Scholar]

- Mathew, S.; Varia, J. Overview of amazon web services. In Amazon Whitepapers; AWS: Seattle, WA, USA, 2014; Volume 105, p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Gallaway, T.O.; Starkey, J. Google drive. Charlest. Advis. 2013, 14, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago, I.; Mellia, M.; M. Munafo, M.; Sperotto, A.; Sadre, R.; Pras, A. Inside dropbox: Understanding personal cloud storage services. In Proceedings of the 2012 Internet Measurement Conference, Boston, MA, USA, 14–16 November 2012; pp. 481–494. [Google Scholar]

- Cisco. Cisco Global Cloud Index: Forecast and Methodology; Cisco: California, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, W.; Jiang, H.; Feng, D.; Douglis, F.; Shilane, P.; Hua, Y.; Fu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y. A Comprehensive Study of the Past, Present, and Future of Data Deduplication. Proc. IEEE 2016, 104, 1681–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, A.; Prabha, C. Leveraging Data Deduplication Approaches in the Cloud Storage: A Succinct Review. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2025, 259, 1640–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halevi, S.; Harnik, D.; Pinkas, B.; Shulman-Peleg, A. Proofs of ownership in remote storage systems. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Chicago, IL, USA, 17–21 October 2011; pp. 491–500. [Google Scholar]

- Dropship. Dropbox API Utilities. GitHub Repository Driverdan/Dropship. 2011. Available online: https://github.com/driverdan/dropship (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Ming, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, J.; Zhang, N.; Shi, W. Blockchain-enabled efficient dynamic cross-domain deduplication in edge computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 15639–15656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yu, Z.; Gu, L.; Feng, D. An efficient encrypted deduplication scheme with security-enhanced proof of ownership in edge computing. BenchCouncil Trans. Benchmarks Stand. Eval. 2022, 2, 100062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, J.; Patil, P.; Patil, H.; Borole, S.; Panda, S. Secure and efficient ownership verification for deduplicated cloud computing systems. J. Cloud Comput. 2025, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Tian, W.; Li, R.; Ye, X.; Xu, Z. Who Owns the Cloud Data? Exploring a non-interactive way for secure proof of ownership. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications (TrustCom), Sanya, China, 17–21 December 2024; pp. 1494–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro, R.; Sorniotti, A. Boosting efficiency and security in proof of ownership for deduplication. In Proceedings of the 7th ACM Symposium on Information, Computer and Communications Security, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2–4 May 2012; pp. 81–82. [Google Scholar]

- Di Pietro, R.; Sorniotti, A. Proof of ownership for deduplication systems: A secure, scalable, and efficient solution. Comput. Commun. 2016, 82, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Chang, E.C.; Zhou, J. Weak leakage-resilient client-side deduplication of encrypted data in cloud storage. In Proceedings of the 8th ACM SIGSAC Symposium on Information, Computer and Communications Security, Berlin, Germany, 4–8 November 2013; pp. 195–206. [Google Scholar]

- You, W.; Chen, B. Proofs of ownership on encrypted cloud data via Intel SGX. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Applied Cryptography and Network Security, Rome, Italy, 19–22 October 2022; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 400–416. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Li, J.; Xie, D.; Cai, Z. Secure auditing and deduplicating data in cloud. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2015, 65, 2386–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, J.; Dutta, A.; Faruki, P.; Laxmi, V.; Gaur, M.S. Secure proof of ownership using merkle tree for deduplicated storage. Autom. Control Comput. Sci. 2020, 54, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco, J.; Di Pietro, R.; Orfila, A.; Sorniotti, A. A tunable proof of ownership scheme for deduplication using bloom filters. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Communications and Network Security, San Francisco, CA, USA, 29–31 October 2014; pp. 481–489. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, L.; Shen, J.; Li, X.; Lin, M. ms-PoSW: A multi-server aided proof of shared ownership scheme for secure deduplication in cloud. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2020, 32, e4252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Manzano, L.; de Fuentes, J.M.; Choo, K.K.R. ase-PoW: A proof of ownership mechanism for cloud deduplication in hierarchical environments. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Security and Privacy in Communication Systems, Guangzhou, China, 10–12 October 2016; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 412–428. [Google Scholar]

- González-Manzano, L.; Orfila, A. An efficient confidentiality-preserving proof of ownership for deduplication. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2015, 50, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Sasson, E.; Chiesa, A.; Tromer, E.; Virza, M. Succinct Non-Interactive zero knowledge for a von neumann architecture. In Proceedings of the 23rd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 14), San Diego, CA, USA, 20–22 August 2014; pp. 781–796. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Lu, H.; Kunpittaya, T.; Luo, A. A review of zk-snarks. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.06877. [Google Scholar]

- Su, S.; Yuan, F.; Yuan, Y.; Zeng, L.; Chen, C. VoFSQ: An efficient file-sharing interactive verification protocol. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC), Athens, Greece, 5–8 September 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Sasson, E.; Bentov, I.; Horesh, Y.; Riabzev, M. Scalable, transparent, and post-quantum secure computational integrity. Cryptology ePrint Archive 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, G.; Jia, C.; Chen, Y.; Chen, H.; Li, M. A secure client-side deduplication scheme based on updatable server-aided encryption. IEEE Trans. Cloud Comput. 2023, 11, 3672–3684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Description |

|---|---|

| F | User file, |

| File identifier, | |

| B | Block size (default ) |

| n | Number of blocks, |

| c | Number of challenge blocks |

| s | Number of partitions; is the partition map |

| Quota from partition k with | |

| Security parameter for soundness | |

| Attacker knowledge ratio of F | |

| Q | Maximum seed attempts per window |

| Standard hash such as SHA256 | |

| ZK friendly hash used in proofs | |

| Challenge index set with | |

| zk STARK proof | |

| Public input and private witness to the STARK | |

| Secret material from the TLS exporter | |

| Mirror seed derived from exporter and context | |

| Request time and discretization window | |

| Connection binding such as transcript hash or session id | |

| Optional client salt included with the fingerprint request |

| File Size (MB) | MiS-PoW | SE-PoW | Dynamic-PoW | MHT-PoW |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 64 | 237.6 | 302.3 | 1148.2 | 1404.2 |

| 128 | 235.9 | 541.7 | 2291.6 | 3127.3 |

| 256 | 236.6 | 1163.3 | 4120.6 | 6152.7 |

| 512 | 236.2 | 2367.9 | 8075.2 | 12,943.6 |

| 1024 | 469.7 | 4379.2 | 18,372.0 | 25,031.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, T.; Wang, L.; Liang, M.; Li, M. MiS-PoW: Mirror-Selected Non-Interactive Proof of Ownership for Cloud Storage. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11897. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211897

Zhou T, Wang L, Liang M, Li M. MiS-PoW: Mirror-Selected Non-Interactive Proof of Ownership for Cloud Storage. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(22):11897. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211897

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Tang, Le Wang, Minxian Liang, and Minhao Li. 2025. "MiS-PoW: Mirror-Selected Non-Interactive Proof of Ownership for Cloud Storage" Applied Sciences 15, no. 22: 11897. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211897

APA StyleZhou, T., Wang, L., Liang, M., & Li, M. (2025). MiS-PoW: Mirror-Selected Non-Interactive Proof of Ownership for Cloud Storage. Applied Sciences, 15(22), 11897. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211897