1. Introduction

The importance of information security has increased as the world has become more interconnected [

1]. The main objective of information security is to protect sensitive and confidential data from unauthorized access, use, and disclosure. According to a 2024 study by IBM and the Ponemon Institute, the average cost of a data breach was USD 4.88 million [

2]. It is clear that organizations, industries, and national security depend on a robust information security program to prevent security breaches and protect critical information.

By adopting an Access Control (AC) mechanism, resources and information can be protected from unauthorized entities and malicious activity. The goal of access control is to ensure that only authorized entities are granted access to the resources and information they need to perform their job functions [

3]. AC has become more important due to the development of recent technologies such as cloud computing [

4], the Internet of Things [

5], and Fog Computing [

6].

The process by which an access request is permitted or denied depends on the AC model implemented. There are four traditional AC models: Discretionary Access Control (DAC), Mandatory Access Control (MAC), Role-based Access Control (RBAC), and Attribute-based Access Control (ABAC). The AC model, in addition to the evaluation process, has an AC policy that defines the set of rules and requirements by which the AC mechanism is regulated. When an access request is received, the AC mechanism interacts with the policy to determine whether the subject has the right to access the requested object.

In addition to traditional AC models, other AC models have been developed to improve the AC mechanism or address the limitations of the traditional approaches. For example, the RBAC and ABAC Combining Access Control (RACAC) model [

7] adopts the strengths of both models. Approaches such as the Hierarchical Group and Attribute-Based Access Control (HGABAC) model [

8] and Higher-order Attribute-Based Access Control (HoBAC) model [

9] formally introduce the concept of hierarchy in ABAC. Ciphertext-Policy Attribute-Based Encryption (CP-ABE) [

10] adds a layer of encryption to the data in the ABAC model. The Hierarchical, Extensible, Advanced, and Dynamic Access Control (HEAD) metamodel [

11] is a proposal that confronts most of the challenges of recent technologies.

To address the present application problems and overcome the limitations of DAC, MAC, and RBAC models that make them less suitable for emerging large and dynamic application domains, the ABAC model was developed [

12,

13,

14,

15]. The ABAC model uses attributes to make access control decisions, making it flexible, scalable, and context-sensitive. The attributes are the characteristics of an entity (subject, object, environment) in the AC mechanism. The ABAC policy is the set of authorization rules defined over these attributes. An ABAC rule specifies whether a subject can access a resource in a particular environment. When an access request is received, the ABAC model evaluates the subject (requester)’s attributes, the object’s attributes, and the environmental conditions with a set of rules (policy) for overall attributes.

However, the main problem with implementing an ABAC model is the policy specification. Policy specification is typically performed by expert humans, which can make it costly, time-consuming, subjective, complex, and error-prone. Consequently, organizations prefer to keep traditional models (MAC, DAC, and RBAC) in operation rather than face all the challenges of the migration and implementation process. Policy mining techniques can be used to automate the policy specification process and address these challenges.

Policy mining is a technique that automates the process of AC policy specification based on an existing AC state, such as Access Control Lists (ACLs), natural language, or access logs. Specifically, the access log contains information on all access requests that are either permitted or denied by the AC mechanism. By using the access log as input, a policy mining process can generate an AC policy as an output. In the context of the ABAC model, this process involves identifying a reduced set of AC rules that properly model the request records in the access log.

Several approaches have been developed for policy mining. Xu and Stoller [

16] pioneered this field by creating rules from user-permission logs, progressively refining them for broader coverage. However, their algorithm demonstrates reduced performance with larger access logs. Iyer and Masoumzadeh [

17] introduced an ABAC policy mining approach using the PRISM algorithm [

18]. Despite its effectiveness in generating positive and negative rules, scalability becomes a challenge with larger access logs, leading to an excess of rules. Cotrini et al. [

19] proposed the Rhapsody algorithm based on APRIORI-SD [

20], featuring stages for rule generation, extraction, and length reduction. While introducing a liability metric, the exponential growth of rules in the presence of numerous attributes remains a limitation. Jabal et al. [

21] presented an ABAC policy mining framework integrating data mining, statistics, and machine learning techniques. Despite its effectiveness, the approach faces challenges due to the substantial number of combinations required for policy extraction. Karimi et al. [

22] contributed to the first machine learning-based approach involving phases such as parameter selection, clustering, rule extraction, and clean-up. Recent investigations [

23,

24,

25] have chosen to detect clusters of access requests before the policy mining process; then, the rule generation algorithms are applied to those clusters.

Table 1 summarizes the challenges and techniques of the state-of-the-art ABAC policy mining approaches.

In summary, an AC mechanism is a complex and dynamic system in which a large number of entities (subjects, objects, environmental conditions, attributes, operations) interact with each other. A purely data-driven approach for policy mining is not sufficient to functionally capture the high complexity of the AC mechanism. To overcome these limitations, recent studies have turned to complex network theory, a powerful mathematical framework for analyzing and modeling complex systems. Specifically, an AC system network model is able to detect hidden patterns and implicit relationships between entities that may not be apparent in the original access log.

Briefly, a complex network is a network (graph) with a set of nodes (vertices) joined together in pairs by a set of links (edges). A network has the function of reducing a complex system to an abstract structure. It captures only the fundamental aspects of entities, which serve as nodes, and their connection patterns, which serve as links. This theory has been a powerful tool with which for scientists to model and analyze real-world systems across a wide range of fields such as sociology, neuroscience, biology, and technology [

26,

27]. Specifically, in security information research, some investigations use complex network analysis for anomaly detection in computer networks [

28], vulnerability analysis [

29], or modeling cyber–physical cybersecurity networks [

30]. In the complex network theory, we can find several network properties such as scale-free degree distribution, community structure, density, and centrality that can help to extract hidden knowledge from the complex interaction system. With the above, we can discover a wide range of added information, e.g., how data flows on the Internet, who the most important person in a terrorist group is, the reliability of a power grid, or groups of people on social media apps.

This paper presents a new proposal for ABAC policy mining based on complex networks. Our proposal uses the access log to generate an ABAC policy that best represents the access requests in the access log. The access log reflects the behavior of the system in a real environment; therefore, it can be used to model a complex network. A bipartite network is generated based on user–resource interactions. Then, a weighted projection to the bipartite network is performed to obtain a user network. A community detection algorithm is applied to the user network to group users and attributes based on the network topology. Each detected community is analyzed to extract the patterns that best represent the community. In this way, it is possible to generate policy rules according to user and resource attributes. Finally, an algorithm is applied to refine the mined ABAC policy and increase its quality. The main contributions of this work are as follows:

A new method based on complex network theory for mining ABAC access control policies from access records.

A bipartite network model to represent user–resource interactions (access requests) in an access control system.

A rule extraction algorithm to extract patterns that best represent the users and the resources of the community.

A network model of the mined rules for evaluating access requests.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 defines the ABAC policy mining problem, discusses the challenges and requirements, and presents the evaluation metrics in this problem.

Section 3 presents our proposed ABAC policy mining approach. In

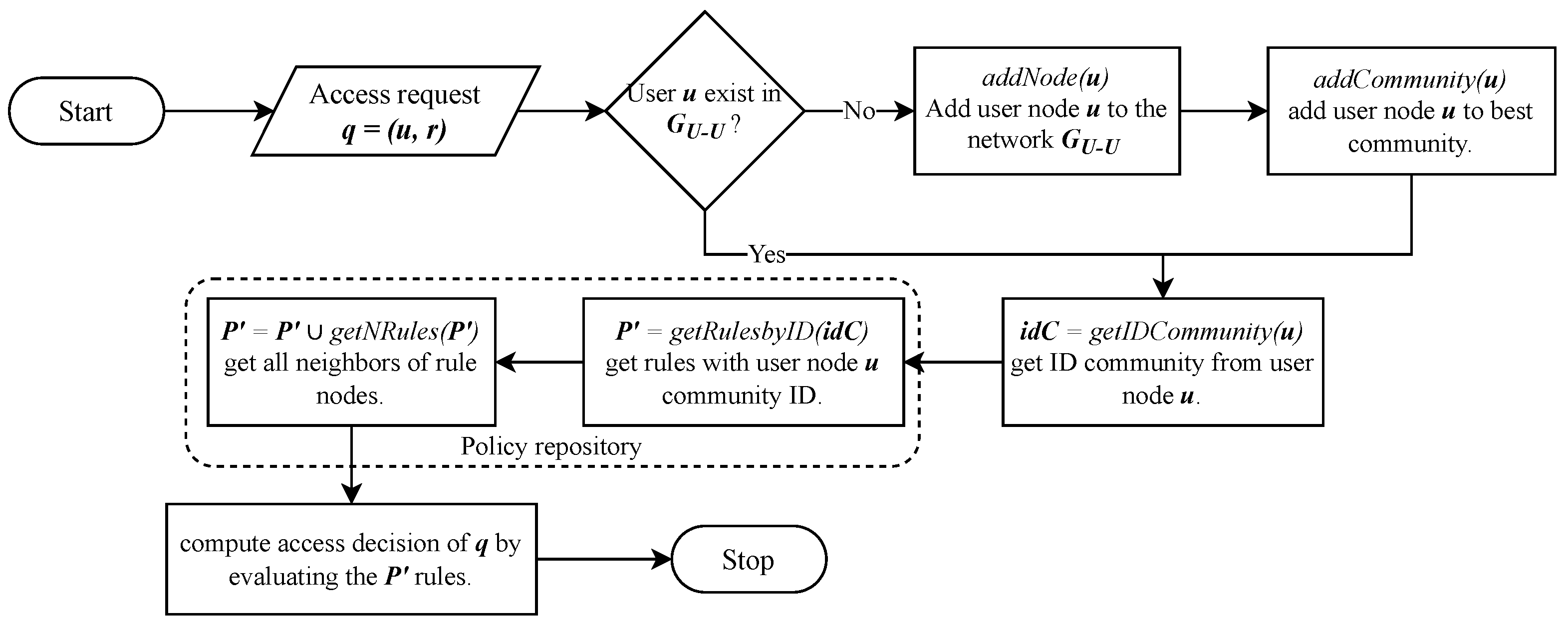

Section 4, we describe the process of access decision in our policy based on the rule network.

Section 5 presents the performance of our approach on two datasets as well as detailed results for every phase of the proposed model. Finally,

Section 6 provides additional discussion and conclusions.

3. Policy Mining Proposed Approach

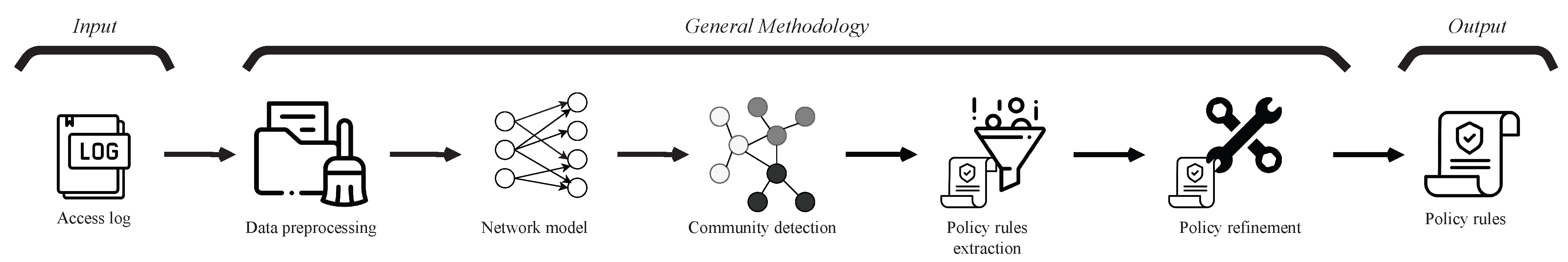

The conceptual methodology of our proposed ABAC policy mining is shown in

Figure 1. Our approach is divided into five phases: (1) data preprocessing, (2) network model, (3) community detection, (4) rule extraction, and (5) rule refinement. The input of the methodology is an access log

, and the output is a set of rules

.

3.1. Data Preprocessing

In this phase, we convert raw data into a cleaner form so that in the next phases of the methodology, it provides more useful information. The input of the phase is the access log , and the output is the new clean access log . We execute four tasks in this phase: (1) handling missing and null values, (2) converting continuous values to categorical values, (3) removing duplicated access requests, and (4) selecting the most used resources.

In the access log, we can find access requests with an error, that present some inconsistency or that are incomplete because there is a misconfiguration in the system or a modification is made by the administrators. This noisy access request and null values can affect the quality of the mined policy. For each attribute in A with a missing or null value, we introduce a unique placeholder value. For example, if there is a null value in a user attribute u.class and a missing value in a resource attribute r.type, we create two new values UNK1 and UKN2, respectively.

In the second task, we convert continuous values to categorical values. Some attributes have continuous values, for instance, the size of a resource r.size; in this case, there are an infinite number of values. To address such an issue, we map the continuous values into categories. In the example above, we can generate groups based on ranges of values.

Our bipartite network model consists of positive unique access requests; therefore, we remove all duplicated access requests, i.e., the same user accessing the same resource. In the last task, we calculate the access frequency of each resource in the access log. There are many resources with few access requests. In other words, just a small number of resources could help to extract more information to build a bipartite network model. We remove all resources under a specified threshold of number of access requests .

3.2. Network Model

The objective of this phase is to build a network model from access log data. The input of the phase is the positive access log , and the output is a complex network that models access interactions of users and resources in the AC mechanism. In this phase, we execute three tasks: (1) bipartite network construction, (2) user network construction, and (3) user network analysis.

3.2.1. Access Request Bipartite Network

The first task is to identify both the entities that will function as the nodes of the network, and the relationship between entities that will represent the links. The basic function of the access control mechanism is to decide whether to grant or reject an access request made by a user toward a resource. Therefore, we identify two disjoint sets of nodes: users and resources. A link exists between a user node and a resource node if a user makes an access request toward a resource. A user cannot make an access request toward another user, and a resource cannot make an access request toward another resource; for this reason, the bipartite network definition condition holds. We define the access request bipartite network formally as follows:

Definition 2 (Access Request Bipartite Network (ARBN)). The access request bipartite network is triplet defined as follows:

- 1.

is the set of nodes that represent users U.

- 2.

is the set of nodes that represent resources R.

- 3.

- 4.

is the set of links that exists between a user node toward a resource node if .

3.2.2. User Network

Bipartite network projection is a method for obtaining two one-mode networks, in our case, a user network (a network with only user nodes) and a resource network (a network with only resource nodes). The one-mode networks are less informative than the bipartite network, but it is possible to apply a weighted projection to minimize the information loss. Our proposed approach only uses the user network. Two user nodes are joined by a link if both users have an access request for the same resource. The weight of the link is equal to the product of the importance of the common resource of each user node. The importance is determined based on the total number of resources each user accesses. We define the user network formally as follows:

Definition 3 (User Network (UN)). Let be an access request bipartite network. The projection generates a user network defined as follows:

- 1.

is the set of nodes that represent users U.

- 2.

is the set of links that exists between two user nodes if they have at least one common neighbor in of the network . The weight of a link is given bywhere is the neighborhood of the node u, i.e., the set of nodes that are linked to node u. is the degree of the node u, i.e., the number of nodes linked to node u.

We analyze the generated user network to evaluate its properties and conclude whether we can use it as a complex network. We use the complex network definition from [

32]:

Definition 4 (Complex Network). A Complex Network is a network consisting of a non-empty set of nodes V and a set of links E. Furthermore, it complies with the following properties:

- 1.

, commonly in the order of thousands or millions.

- 2.

Low average degree .

- 3.

Low density .

- 4.

Scale-free distribution .

- 5.

Low average path length .

- 6.

High average cluster coefficient .

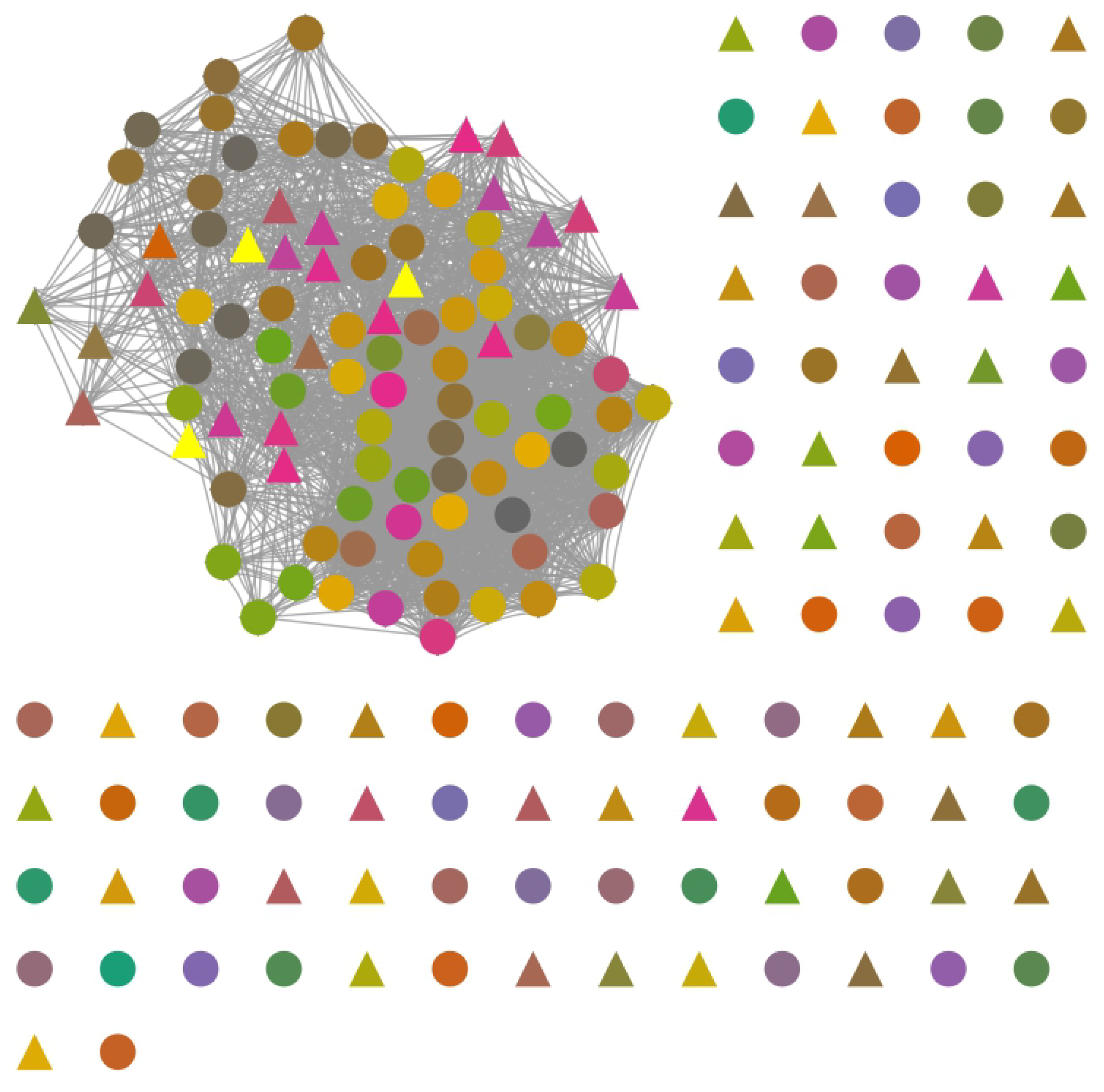

3.3. Community Detection

The main objective of this phase is to group the user nodes in communities or subnetworks. When we identify communities, the nodes within a community may share common properties or play similar roles in the complex network [

33]. A community is a group of nodes where there are a large number of links between nodes within the same community and with the rest of the nodes in other communities. From the communities, it is feasible to extract user characteristics or properties that can help in the generation of ABAC policy rules.

The input data of this phase is the user network obtained in the previous phase. The output data will be a node partition . In the current phase, two tasks are executed: (1) community detection and (2) community classification.

In the first task, a node partition is obtained by a community detection algorithm, and then, they are classified into three groups based on the number of resources accessed by each community.

3.3.1. Community Detection

We use the

Louvain algorithm [

34], which is based on optimizing the modularity quality function. The Louvain algorithm was chosen based on a prior comparative analysis of various methods, where we sought a balance between maximizing modularity and computational efficiency. The Louvain method demonstrated superior performance in this regard. Modularity is one of the most popular quality functions for measuring the quality in obtained community partition [

35]. It compares the link density of each community with the density that could be obtained from the same community, but from a random network, where a community structure is not obtained [

33]. By definition,

; a value close to unity indicates a better partition. The definition of modularity is

where

m is the number of links in the network, and

A is the adjacency matrix. The term

represents the expected number of links given the degree of the two nodes and the total number of links in the network. The function

returns one if the nodes

i and

j belong to the same community; it returns zero in the other case.

Louvain’s algorithm to detect communities iteratively executes two phases. First, each node is a new community. Next, each node joins the community of one of its neighbors which provides a higher modularity value. The above is repeated for all nodes until the modularity value does not improve with new node joins. In the second phase, all the nodes of a community are grouped, and a new network is built where the nodes are the communities of the previous phase. The time complexity of the Louvain algorithm is , where n is the number of nodes in the network. The algorithm is non-deterministic and belongs to the group of agglomerative hierarchical algorithms.

In our approach, the detected communities correspond to groups of users that exhibit similar interaction patterns within the access control system. These communities arise from the projection of the ARBN, where nodes represent users and resources, and edges indicate recorded accesses. Projecting this graph onto the set of users generates a network in which users are connected if they share access to common resources. This structured projection allows the application of community detection techniques, grouping users who access similar sets of resources. Thus, communities reflect functional groupings that can be aligned with organizational roles or access profiles, providing a structural basis for rule inference in the ABAC model. At the end of the algorithm, we will obtain the user communities defined as follows:

Definition 5 (User Communities)

. Let be a user network. A community is a sub-network of the user network , where and . The user communities of the user network is In the community partition , we can find sparse communities, i.e., networks with a low density. Our objective is to obtain dense communities; for this reason, we apply the Louvain algorithm to those sparse communities to obtain dense sub-communities. Ultimately, we expect that all communities and sub-communities have a density value close to a unit; in other words, the groups of users detected are densely connected.

3.3.2. Community Classification

We classify communities based on the number of resources accessed by each community. There are three types of communities: F-type: focused; M-type: medium; and S-type: sparse. Regardless of the size of the community, focused communities access few resources, typically one or two. Sparse communities, on the other hand, have access to a large number of resources, greater than a threshold . Medium communities access between three and .

Each detected community is evaluated based on the number of resources accessed . To begin, we find the maximum number of resources accessed by any community, denoted as . Two thresholds and are set, using a fraction of the number of resources and . S-type communities have greater resources than . M-type communities have resources between and , and F-type communities have resources below . Algorithm 1 shows the process of community classification.

Each detected community

is evaluated based on the number of resources accessed

. To begin, we find the maximum number of resources accessed by any community, denoted as

. Two thresholds

and

are set, using a fraction of the number of resources

and

. S-type communities have greater resources than

. M-type communities have resources between

and

, and F-type communities have resources below

. Algorithm 1 shows the process of community classification.

| Algorithm 1 Community classification algorithm. |

- 1:

procedure

CommunityClassification - Input:

, , - Output:

- 2:

- 3:

- 4:

- 5:

for all

do - 6:

if then - 7:

- 8:

else if then - 9:

- 10:

else - 11:

- 12:

end if - 13:

end for

|

3.4. Policy Rule Extraction

In this phase, we analyze the communities and generate ABAC policy rules. Then, a rule network is generated. The input data are the classified user communities, obtained from the previous phase. The output is a network of ABAC policy rules.

According to Definition 1, a rule is a tuple

. In our proposal, rules are limited to having only the attribute filter

, and the decision value

d. Additionally, we add the unique identifier of the communities from which the rules were inferred. The identifier will help the access decision in the AC. An example of a rule generated in our proposal is shown below:

3.4.1. Rule Inference

There are three ways to extract rules from communities, depending on the type of community. Algorithm 2 outlines the process of inferring rules. The input to the algorithm is the community classification , and the output is the set of rules .

F-type communities: The first step is to extract the resource set that is accessed by all users in the community. If there is more than one resource (), all attribute–value pairs in common, among all resources in , are taken to add to the rule. If there is only one resource that all users in the community access, then all the attribute–value tuples that identify the resource are taken to generate the rule. The next step is to obtain the attribute–value tuples of the users. The tuples with the highest frequency in the community are obtained.

M-type communities: A less frequent resource pruning process is used (Algorithm 2, line 7). In M-type communities, it is possible to identify less frequent resources that are accessed by a small number of users compared with the rest of the resources. The information that less frequent resources can offer us does not have any meaningful impact on the generation of rules; on the contrary, it could add noise to the rule. Less frequent resources do not describe or reflect user access in a community.

| Algorithm 2 Rule inference algorithm. |

- 1:

procedure

RuleInference - Input:

- Output:

- 2:

- 3:

for all

do - 4:

- 5:

▹ only M-type or S-type communities. - 6:

if then - 7:

- 8:

▹ only S-type communities. - 9:

if then - 10:

- 11:

for all do - 12:

- 13:

- 14:

- 15:

- 16:

end for - 17:

- 18:

end if - 19:

end if - 20:

▹ all communities: F-type, M-type, and S-type. - 21:

- 22:

- 23:

- 24:

- 25:

end for

|

To prune less frequent resources, it is necessary to set a threshold based on the number of users accessing a resource . The threshold value can vary, but it is recommended that it be or up to for all users—for example, if there are 20 users in community C, and a threshold of is established; that is, . In this example, the resources that are accessed by two users or fewer are considered less frequent resources; therefore, they are removed from the total of resources in the community. Once the resource pruning is executed, the same process is applied as for F-type communities.

S-type communities: This type of community is characterized by having a large number of users and resources. As there are more resources in the community, it is more difficult to generate rules that characterize it. It is possible to identify a small set of resources that are accessed by the most users in the community. The set of most frequent resources, called significant resources, is useful for characterizing the entire community of users.

As in the M-type communities, less frequent resources are filtered out. Subsequently, the F-type community approach is applied with a slight modification. Rules are generated with the set of significant resources, the common attribute–value tuples are taken from the set, and the rule is completed with the users of the community. Then, with the less significant resources not eliminated, rules are generated with the F-type community approach. S-type communities tend to generate more rules than the rest of the communities.

3.4.2. Rule Network Modeling

The construction of the rule network takes as nodes the rules of the set . A link joins two nodes if the Jaccard index is above a given threshold as given in Definition 6. The threshold serves two key purposes: first, to ensure that the resulting network maintains a low edge density, and second, to optimize the F-score value. Through empirical evaluation, we identify the threshold value that yields the best trade-off between sparsity and classification accuracy. Having a densely connected rule network is not beneficial because it would result in all rules being connected, which is not desirable during evaluation. The goal is to preserve the distinctiveness of individual rules.

Definition 6 (Rule Network). The rule network is a tuple defined as follows:

- 1.

is the set of nodes that represent rules .

- 2.

is the set of links that exists between a node toward a node if the Jaccard index is above a given threshold .where .

3.5. Policy Refinement

The objective of policy refinement is to improve the quality of the mined policy in the previous phase by tackling false negatives and false positives. We create new rules to overcome false negatives and negative rules for false positives. Negative rules restrict access to requests that match their attribute–value tuples. They have the opposite functionality of the rules generated. Because they are specific rules, they tend to contain many attribute–value tuples.

The input of policy refinement is the set of false negatives (FN), false positives (FP), and rule network . At the end, the output is an augmented set of rules and an updated rule network. The phase is composed of three tasks: (1) FN-refinement, (2) FP-refinement, and (3) rule network update.

FN-refinement: The set of FNs is those access requests that are allowed by the original policy but not by the mined policy. The rule inference process is applied but as the input for the access requests in the FN set. At the end of the process, a set of rules based on the FN requests will be obtained.

FP-refinement: For FPs, it is not possible to apply the complete rule inference approach because there are no relationships between users and resources in the access requests. Refinement in FP tracks the rules that produce the requests in FP and, from these rules, generates negative rules. Value attribute tuples of requests in FP are added to the positive rule generated by the FP to generate a specific negative rule.

Rule network update: Once the rules are generated in the two previous stages, the rule network is updated by adding the new rules obtained in the FN-refinement. In the same way, the Jaccard similarity index is used to create new links between the existing and new nodes. For the resolution of the requests, the community identifier obtained in the rule inference phase is considered.

6. Conclusions and Discussions

In this work, a novel approach for ABAC policy mining based on the analysis of complex networks is proposed. Each phase of the proposal is described, and experimental results are presented. Our work receives as input an access control log which contains the records of access requests, both permitted and denied. The output is the ABAC access control policy, modeled as a network, which contains the rules and their relationships that will be evaluated to determine whether an access request is permitted or denied.

Our approach transforms access logs into a bipartite network of users and resources, which is converted into a user network through weighted projection based on shared resources. The Louvain algorithm detects communities in this network, classified into three types by resource access patterns. For each community, rules are inferred from attribute frequencies and adapted to community characteristics, forming a structured rule network.

The initial rule network is refined by addressing uncovered positive requests and incorporating negative rules, resulting in an augmented policy with improved accuracy. This network-based methodology leverages topological properties to identify functional roles and access patterns, proving to be an effective alternative to traditional clustering techniques while maintaining interpretability and scalability in access control management.

Our network-analysis-based approach generates ABAC policies with high accuracy; that is, they replicate with high similarity the access control policy that originated the access log. The set of extracted rules is modeled as a network; the policy obtained is not a list of rules but a structure of rules which helps in the process of rule evaluation. This constitutes a novel approach to modeling access control rules not previously reported in the literature.

The comprehensive evaluation demonstrates the robustness and adaptability of our approach under various challenging conditions. When tested on noisy datasets, generated by randomly reversing access decisions, and sparse datasets, created by randomly selecting subsets of access requests, our method maintained stable policy structures with only moderate decreases in F-score. This resilience to data perturbations confirms that the underlying network structure effectively captures essential access patterns rather than overfitting to specific data points. Furthermore, our investigation of threshold parameters revealed that intermediate values (, generally provide an optimal balance between policy quality and complexity across diverse datasets, though we acknowledge that these parameters may require adjustment for datasets with substantially different characteristics.

Crucially, comparative analysis against randomly structured networks—generated using the configuration model with random edge weights—validates the significance of our structured approach. The substantially higher F-scores achieved by our model across all datasets, with only minimal increases in complexity metrics, demonstrate that the discovered network topology contains meaningful access control information beyond mere connectivity patterns. This superior performance persists even when the random networks occasionally achieve slightly lower complexity, indicating that our method’s quality improvements justify the modest complexity overhead.

While our approach demonstrates strong performance in replicating access control policies and introduces a novel network-based modeling framework, it also presents certain limitations. One notable challenge is the high number of rules generated, which can increase the complexity of the mined policy and potentially affect its manageability. Although we propose viewing complexity through the lens of rule network structure, further work is needed to develop formal metrics that capture structural interpretability and operational efficiency.

Moreover, the current methodology relies on a fixed network modeling strategy, which may not be optimal across all datasets or organizational contexts. To address this, future work will explore more flexible and context-aware modeling approaches, including alternative community detection strategies that better adapt to the structure of user–resource interactions. Additionally, we plan to investigate automated threshold selection methods and expand our evaluation to include more diverse organizational settings and security policies to further validate the generalizability of our approach.