Abstract

The Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) requires all EU Member States to establish Whole Life Carbon (WLC) benchmarks by 2030. While progress is being made across Europe, a comprehensive and standardised national methodology remains absent in Italy, raising broader questions about how to ensure comparability of WLC assessments across diverse territorial contexts. Italy represents a particularly complex case, as its building stock is regulated simultaneously by seismic zoning and climatic zoning, complicating the definition of representative archetypes. This study applies Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) to a prototypical residential building in Tuscany, testing scenarios that vary by seismic risk and exposure conditions. Results show that structural components dominate impacts, accounting for approximately 60% of total Global Warming Potential (GWP), and that outcomes are highly sensitive to both location and data source. These findings underscore the importance of data granularity and context-specific modelling in developing robust benchmarks. The novelty of this work lies in proposing a framework that integrates seismic and climatic factors into archetype selection, while also emphasising the adoption of nationally tailored datasets to improve accuracy and policy relevance. By situating the Italian case within the wider European debate, the paper contributes to the urgent task of establishing robust, comparable, and context-sensitive WLC benchmarks that can guide both national regulation and EU-wide decarbonisation strategies.

1. Introduction

The decarbonization of the building sector has emerged as a strategic priority within European climate policy, given that construction activities account for approximately 40% of total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [1]. In response, the European Union has progressively strengthened its regulatory framework, most notably through the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD)—which now includes provisions for assessing and reducing Whole Life Carbon (WLC) emissions, encompassing both operational and embodied sources. The latest revision of the EPBD [2], aligned with the Fit for 55 climate package, marks a significant step forward by introducing ambitious targets: a 55% reduction in GHG emissions by 2030 and full carbon neutrality by 2050. These objectives underscore the need for comprehensive WLC assessments and reflect a decisive shift toward integrating life cycle thinking into mainstream building design and policy implementation. To meet these goals, Member States must pursue a dual strategy: improving the energy performance of new buildings and accelerating deep renovation of existing stock. A key innovation is the integration of WLC metrics into Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs), starting in 2028 for buildings over 1000 m2 [2]. Achieving meaningful WLC reductions requires the development of national roadmaps, including performance thresholds tailored to climatic zones, building typologies, and design constraints.

Establishing reliable benchmarks requires a detailed mapping of national building stocks to identify representative archetypes and their associated carbon profiles. According to ISO 21678:2020 [3], benchmarking involves the collection and analysis of performance data from comparable buildings, and should include limit, reference, and target values to guide both compliance and innovation.

To support this process, it is essential to develop Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) tools and databases that are widely recognised and validated, enabling transparent and consistent evaluation of environmental impacts across the entire life cycle (WLC) of buildings [4]. In this context, the European Commission entrusted the Joint Research Centre (JRC) in 2014 with the development of the Level(s) framework, which provides a shared methodological basis and a core set of sustainability indicators for assessing the environmental performance of residential and office buildings across Europe throughout their whole life cycle.

Within the Level(s) framework [4], WLC is a cross-cutting principle, reflected in Indicator 1.2, which quantifies GWP across all building life cycle stages [5]. This indicator is adopted in key EU-level applications-from the EPBD to the taxonomy-and in national contexts such as the CAM in Italy [6].

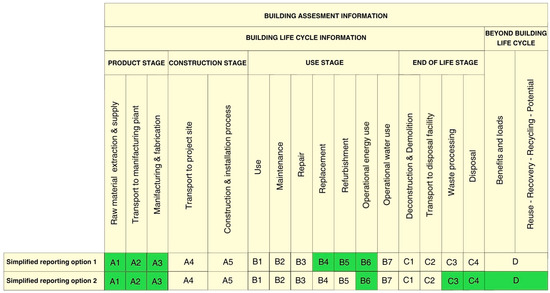

In anticipation of broader availability of validated data, dedicated software tools, and professional training on GWP calculation, Indicator 1.2 within the Level(s) framework proposes two simplified short-term approaches, shown in Figure 1. Option 1 focuses on the trade-off between embodied impacts of construction materials and the achievement of nearly zero-energy building performance, including use-stage modules B2–B4 (maintenance, repair, replacement) based on client-defined service life and scheduled interventions. Option 2 shifts attention to end-of-life benefits (Module D), assessing the potential for reuse and recycling of building materials—referred to as the “material stock”—in accordance with EN 15978 calculation rules [7].

Figure 1.

Overview of simplified GWP calculation options defined by Indicator 1.2. Green cells indicate the stages included in the calculation scope.

Although several countries have already adopted national frameworks, Italy currently lacks a unified methodology for calculating WLC. The most relevant initiative to date is embedded in the Minimum Environmental Criteria (CAM) for public buildings, which includes a simplified LCA approach. However, aligning national practices with EU standards-such as the Level(s) framework-is essential for consistency and comparability.

To this end, the second simplified approach proposed under Indicator 1.2 Life cycle Global Warming Potential of Level(s) has provided a relevant methodological reference for the ongoing revision of the CAM in Italy applied to the road and infrastructure sector [8] which is expected to be followed by the building sector as well [7], marking a key step toward methodological convergence and regulatory alignment.

This methodological choice is further supported by two key considerations. First, as outlined in the framing of the study, the selected approach reflects the most robust national reference available at the time of analysis and is particularly appropriate given that the case study involves a public building subject to CAM requirements. Second, the literature consistently highlights that the majority of embodied emissions occur during the early stages of a building’s life cycle—the so-called “upfront” phase—particularly during material manufacturing and construction activities [9,10]. These factors reinforce the relevance of adopting a simplified yet policy-aligned approach for the purposes of this exploratory study.

Nonetheless, Italy faces a major challenge linked to its territorial conditions, particularly in terms of climate and seismic classifications. While climate zones have already been integrated into previous benchmarking efforts [11,12], seismic factors remain largely unaddressed—despite their significant influence on structural design choices and embodied carbon emissions.

Recent findings from Spain, within the INDICATE framework [13,14], reveal that buildings designed without seismic constraints can exhibit up to 80% lower GWP impacts of the structure compared to those in high-risk zones. These insights underscore the importance of integrating structural resilience into carbon accounting methodologies, especially in regions with complex geophysical profiles. These insights underscore the importance of integrating structural resilience into carbon accounting methodologies.

Against this backdrop, the objective of the present study is twofold. First, it aims to deliver a simplified LCA consistent with the Simplified Reporting Option 2 of the Level(s) framework, focusing exclusively on the stages relevant to the quantification of embodied impacts-namely, stages A1–A3 and C3 and C4-considering that the building under analysis is designed as a Nearly Zero Energy Building (NZEB). This approach is intended to support practitioners in correctly following the procedural steps required to perform the WLC assessment of buildings, as outlined under Indicator 1.2, and to provide a basis for informed material choices aimed at reducing the GWP. Second, the study seeks to investigate the influence of seismic constraints—specifically the transition from low-risk to higher-risk seismic zones—on the overall calculation of GWP.

To this end, the analysis focuses on a building designed for Marina di Massa, in Tuscany (climate zone D3 and seismic classification 3), intended for social and care-related functions, and partially for social housing. After assessing the impacts associated with stages A1–A3, C3–C4, and D, the scope is narrowed to the structural component alone, evaluating how the GWP value changes when shifting from seismic zone 3 (baseline) to zone 2 (more stringent). In order to enable comparative evaluations of environmental impacts across the full life cycle, the ultimate goal is to abstract the case study into a representative archetype of multi-user buildings subject to medium-level seismic constraints and located in climate zone D (one of the most widespread in Italy). This archetype is defined through key parameters such as construction system, climate zone, seismic classification, functional use, number of storeys, year of construction, heating degree days, and type of intervention.

2. Materials and Methods

In order to apply the Level(s) framework—Simplified Reporting Option 2—to a representative case study building, this section provides a detailed description of the asset under investigation, including its functional characteristics, construction materials, and design features. The scope and system boundaries of the assessment are defined in accordance with EN 15978 [7] and the methodological principles of Level(s), ensuring that the selected life cycle stages and processes are consistent with the intended goal of the study. Particular attention is devoted to the quantification of embodied GWP impacts, calculated by combining material inventories with environmental data sourced from verified databases and Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs).

In line with the objective of applying the Level(s) framework—Simplified Reporting Option 2—to a representative case study building, this section begins with a detailed description of the asset under investigation (Section 2.1), including its functional characteristics, construction materials, and design features. It then outlines the methodological approach adopted (Section 2.2) and the operational steps undertaken to quantify the embodied GWP impacts associated with the baseline scenario. To further investigate how seismic factors and material specifications influence design requirements and environmental performance, two comparative scenarios are presented. The first examines the influence of seismic zoning on structural demands, while the second explores how varying concrete exposure classes affect durability-related design choices. Finally, the study focuses on the impact of data granularity on the assessment results, specifically taking into account different sources of data for concrete.

2.1. Case Study Building Description

This study examines a newly constructed residential facility located in Marina di Massa, Tuscany, classified as seismic zone 3 and climate zone D (Table 1, Figure 2).

Table 1.

Key parameters of the analysed building for the identification of the reference model.

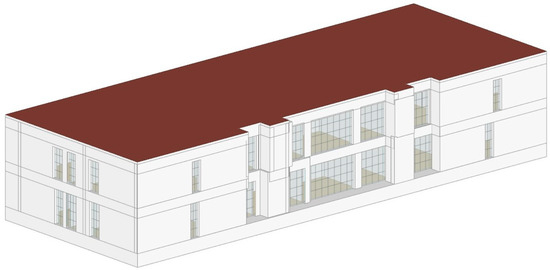

Figure 2.

Three-dimensional model of the building.

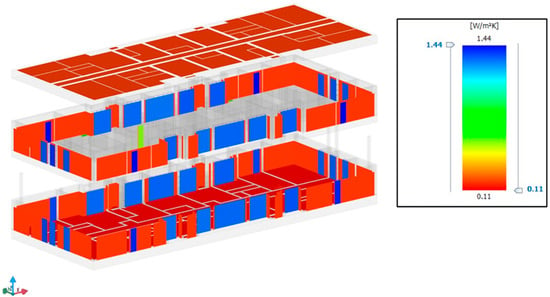

The building was designed to meet the requirements of the NZEB (Nearly Zero Energy Building) target, achieving energy efficiency class A4 (<0.40 kWh/m2·year) according to the Italian classification system [13], as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Building energy performance simulation model.

The new facility is designed to accommodate two distinct residential functions across two above-ground levels. The ground floor hosts a care unit aligned with the national “Dopo di Noi” programme, offering temporary or permanent housing for minors and adults lacking adequate family support, including individuals with physical or cognitive disabilities. The upper floor comprises eight social housing units intended for economically and socially vulnerable populations.

From a structural perspective, the building adopts a braced steel frame system engineered to ensure seismic resistance and overall stability. The primary load-bearing framework consists of continuous HEB260 steel profiles for both vertical columns and horizontal beams, welded at structural nodes to guarantee mechanical continuity. Lateral stability is achieved through triangulated bracing elements made of HEB160 profiles. To further enhance stiffness and load distribution, a secondary vertical reinforcement system in cast-in-place reinforced concrete is integrated into the structural design.

The foundation system employs shallow inverted beams in reinforced concrete. Intermediate floor slabs are constructed using lightweight precast predalles panels with embedded expanded polystyrene inserts. This configuration ensures diaphragm action, facilitating efficient horizontal load transfer and optimising the performance of the braced frame under seismic conditions.

This detailed description of the building’s functional and structural characteristics provides the basis for the subsequent quantification of embodied GWP impacts, as outlined in Section 2.2.

2.2. Quantification of Embodied GWP Impacts

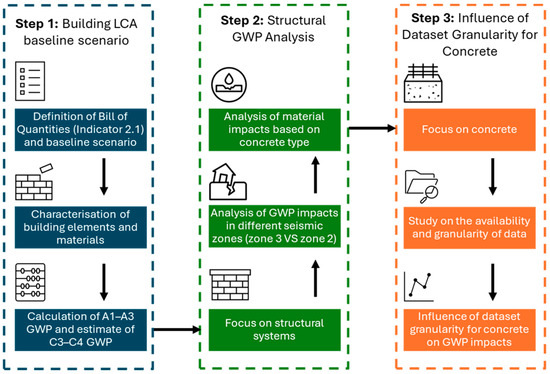

The methodological framework adopted comprises three main phases (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Steps involved in the study.

2.2.1. Step 1: GWP Estimation via Simplified LCA (Baseline Scenario)

The first step of the building-level LCA consists of defining the Functional Unit (FU) and the system boundaries. In accordance with the Level(s) framework, the FU is set as 1 m2 of useful floor area (UFA), evaluated over a reference period of 50 years, as specified by EN 15978. Based on this definition, and in line with the system boundaries established under Simplified Reporting Option 2 of the Level(s) framework, the modelling of the included life cycle stages was carried out using specific data sources and assumptions, as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Overview of data sources and modelling assumptions applied within the defined system boundaries.

The modelling of impacts for Modules A1–A3 (Product stage) was conducted using the One Click LCA software, with a database specific to Italian materials and products. For Modules C3–C4 (End-of-life stage), default data were sourced from a recent study on whole life carbon emissions in European buildings [15], considering the typology of multi-family housing. Assuming that Modules A1–A3 account for approximately 76% of embodied emissions, the contribution of end-of-life stages was estimated at around 1% for C3 and 3% for C4. These values were adopted as reference assumptions for simplified modelling.

Moreover, given the marginal impact of stage C3 and the separate analytical nature of Module D, benefits beyond system boundaries were excluded from the analysis. This choice reflects the study’s focus on embodied impacts associated with material production, which represent the most significant share of total emissions and provide a robust basis for evaluating design strategies.

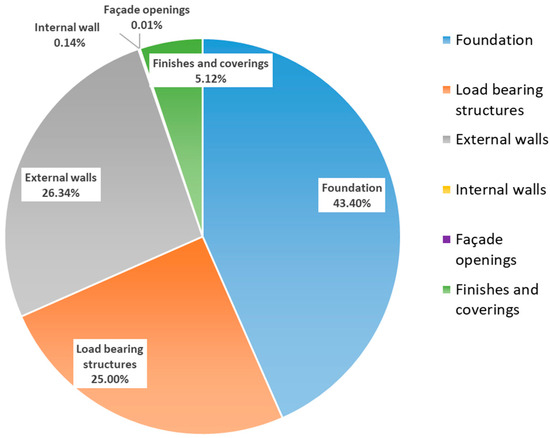

Following the definition of the goal and scope, the analysis focused on quantifying the materials required across building components, in line with Indicator 2.1—Bill of Quantities (BoQ) for Level 2 estimation. The collected data served as the basis for evaluating Indicator 1.2 (Life cycle GWP) and for conducting the life cycle assessment (LCA). In this step, the mass of materials and construction products was classified according to building elements, including structure, foundation, external and internal walls, openings, and finishes. Figure 5 illustrates the mass-based percentage distribution across building elements.

Figure 5.

Mass composition by building element.

Based on these quantities (i.e., the Bill of Materials), GWP impacts were calculated for stages A1–A3 using One Click LCA selected for its documented compatibility with the Level(s) framework and its ability to support Indicator 1.2. Its use was justified by its alignment with key functional and methodological criteria, such as data transparency, sector relevance, and integration with European standards

Based on these quantities derived from the Bill of Quantities (BoQ), GWP impacts were calculated for stages A1–A3 using One Click LCA [16], one of the tools recognised for its compatibility with the Level(s) framework and its ability to support the calculation of Indicator 1.2 [5].

2.2.2. Step 2: GWP of Structural Elements in Seismic Zone 2

Building on the baseline scenario, Step 2 involved a focused assessment of the structural system, with particular attention to the implications of seismic design. The analysis concentrated exclusively on the structural components of the building (Table 3), recalculating the GWP for modules A1–A3 based on the material quantities required for seismic zone 2, which corresponds to moderate seismicity. This refinement allowed for a more context-sensitive evaluation of environmental impacts, reflecting the additional material demands imposed by structural reinforcement in seismic-prone areas.

Table 3.

Bill of Materials classified by building elements (Baseline scenario).

In particular, to evaluate the influence of seismic classification on material demand and associated environmental impacts, two alternative structural configurations were modelled and compared against the reference case.

The Baseline configuration reflects the actual design of the building located in Marina di Massa (seismic zone 3, seawater exposure). Material quantities and typologies were extracted directly from the construction drawings and technical documentation.

The baseline scenario in comparison 1 (Table 4) refers to the conditions of the building reflecting the real location and design strategies used for its construction; in this case, the building is located in an area classified as seismic zone 3 (moderate-low risk) and built with a robust steel structure; the comparison scenario, chosen to reflect a higher seismic risk, sees the building located in an area classified as seismic zone 2 (moderate-high risk), requiring more steel to reinforce the structure to guarantee a higher resistance against the seismic load [17,18,19].

Table 4.

Comparison 1—Seismic scenario change.

Keeping the seismic zone location constant to zone 3, Table 5 shows the comparison between the baseline scenario of the building located in climate zone D, in an area close to the sea and built using concrete which is resistant to seawater splashes (C35/45 XS3), and other scenarios where the same building is moved to a different area within the same climate zone, but with different exposure types. In particular, a scenario with a milder exposure to seawater was considered, resulting in the use of a different type of concrete (C35/45 XS1), and a scenario where the building is located inland, with no exposure to seawater, which is associated with the use of a more generic concrete and moderate humidity exposure class (C30/37 XC3).

Table 5.

Comparison 2—Exposure class change.

2.2.3. Step 3-Granularity of LCA Data Sources for Concrete

The final phase of the study focused on estimating the GWP associated with different types of concrete, given their significant contribution to overall environmental impacts. In addition to the One Click LCA dataset, two further LCA data sources were adopted: values from the national LCA dataset and average Environmental Product Declaration (EPD) data for concrete produced in Italy.

In the first case, impact data were adapted to the Italian construction sector using datasets specifically developed for the concrete supply chain, based on national data intended to populate the Arcadia LCA database [20]. These results were then compared with values derived from generic datasets sourced from international databases [16] and from average sectoral EPDs representative of the Italian market [20,21], highlighting the influence of regional assumptions on GWP outcomes.

This step had a dual objective: on one hand, to understand the influence of data granularity and localization, thereby guiding more accurate modelling of embodied carbon impacts; on the other, to explore the correlation between data sources and design phases—particularly during early-stage planning, when product-specific EPDs are not yet available.

3. Results

3.1. Global Warming Potential of the Building

The assessment was carried out using the software OneClick LCA and following the requirements of the Level(s) framework, focusing on GWP impacts only. The Level(s) life cycle carbon assessment is carried out using the CML method [22] and PEF data [23].

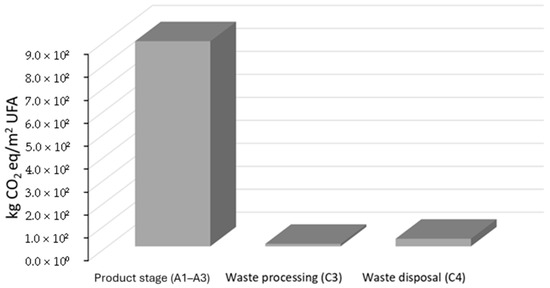

3.1.1. GWP per Life Cycle Stage

Table 6 and Figure 6 present the GWP impacts across the life cycle stages considered. As expected, based on the assumptions made for the end-of-life phase—which accounts for just over 4% of the total—the production stage dominates the overall carbon footprint, contributing 971,992.22 kg of carbon dioxide equivalent. Expressed per unit of usable floor area, this corresponds to 892.74 kg of carbon dioxide equivalent per square metre. Consequently, waste processing (stage C3), estimated to account for 1% of the total impact, corresponds to 12,052.70 kg of carbon dioxide equivalent, while waste disposal (stage C4), representing 3%, contributes 36,158.11 kg of carbon dioxide equivalent. Combined, the end-of-life stage (C3–C4) amounts to 48,210.81 kg of carbon dioxide equivalent, or 44.28 kg per square metre of usable floor area. These results are consistent with the values reported in study [15] for single-family houses, which—among the typologies analysed in the referenced research—is the most comparable to the case study examined.

Table 6.

Distribution of GWP by Life Cycle Stage, expressed per square metre of usable floor area (m2 UFA).

Figure 6.

GWP impact (kgCO2 eq/m2 UFA) reported for each life cycle stage considered in the assessment: product stage (A1−A3), waste processing (C3) and waste disposal (C4).

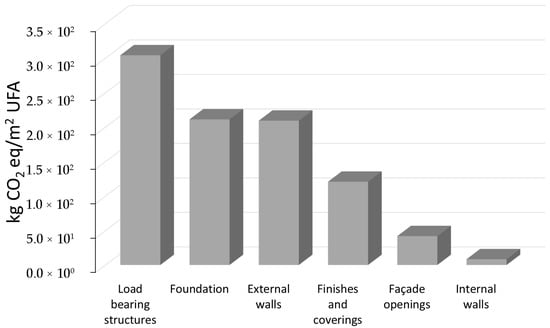

3.1.2. GWP per Building Elements

The GWP contribution across different building elements from the product stage (A1–A3), as shown in Table 7 and Figure 7, reveals that load-bearing structures are the largest contributor, with 331,068.1 kg of carbon dioxide equivalent (304.1 kg per square metre of usable floor area), accounting for 34% of the total.

Table 7.

GWP impacts from the product stage (A1–A3) reported by building element, expressed as total impact (kg CO2 eq), expressed per unit of useful floor area (kg CO2 eq/m2 UFA), and relative contribution (%).

Figure 7.

GWP impact (kgCO2 eq/m2 UFA) reported for each building element considered in the study: load bearing structures, foundation, external and internal walls, finishes and coverings and façade openings.

The foundation and external walls follow closely, contributing 23.6% and 23.4%, respectively. Finishes and coverings add a further 13.5%, while façade openings represent 4.7%. The contribution of internal walls is negligible at less than 1%. The predominance of load-bearing structures and foundations can be explained by their large material volumes (accounting up to nearly 70% of the total building’s mass, Figure 5) and the high embodied carbon intensity of structural materials such as reinforced concrete and steel, which are essential for ensuring stability and safety. Given their overwhelming share of the total impact, the subsequent analysis in this article will concentrate on these structural components, as they represent the most effective leverage points for reducing embodied carbon in the building.

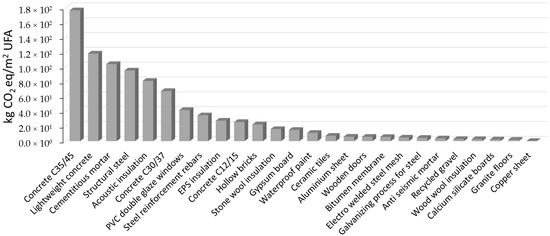

3.1.3. GWP per Building Material

To better understand the contribution to the A1–A3 GWP impacts of the different materials, Figure 8 reports the distribution of GWP impacts across the main materials used in the building. The results show that concrete mixes are the dominant contributors, with C35/45 (191,949 kg CO2 eq), lightweight concrete (128,473 kg CO2 eq), and C30/37 (73,496 kg CO2 eq) together accounting for the largest share of embodied emissions (nearly 60%). This reflects both the large volumes of concrete required for structural and foundational elements and the high carbon intensity of cement production. Among metals, structural steel (103,560 kg CO2 eq) and reinforcement rebars (37,737 kg CO2 eq) represent significant hotspots, further emphasising the impact of structural components. Other relevant contributions include cementitious mortar (113,019 kg CO2 eq) and acoustic insulation (88,421 kg CO2 eq), while finishing materials such as PVC double-glazed windows (45,578 kg CO2 eq) and hollow bricks (24,393 kg CO2 eq) add smaller but non-negligible shares. In contrast, lightweight materials such as cork panels, wood wool insulation, or granite flooring contribute only marginally. Overall, the results confirm that the structural materials (concrete and steel) dominate the embodied carbon profile, which justifies the focus of the subsequent analysis on strategies for reducing impacts in these components.

Figure 8.

GWP impact (kgCO2 eq/m2 UFA) reported for each material used in the building.

3.2. Impact of Structural Scenarios

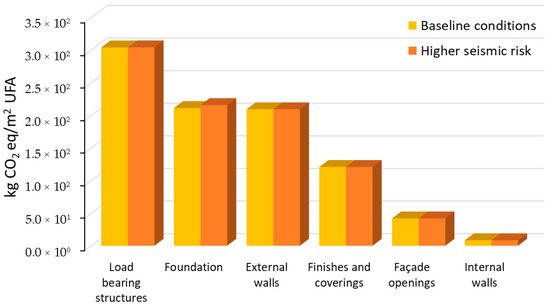

3.2.1. Comparison 1: Seismic Scenario Change

The comparison between the baseline building (Zone 3) and a scenario located in a higher seismic risk zone (Zone 2) is presented in Table 8 and Figure 9, respectively. In this case, the only design change is a 14% increase in steel mass within the load-bearing structure, reflecting the additional reinforcement required under stricter seismic design criteria. The results show that the overall GWP rises only marginally, from 974,948 kg CO2 eq (895.46 kg CO2 eq/m2 UFA) in the baseline to 980,231 kg CO2 eq (900.31 kg CO2 eq/m2 UFA) in the higher seismic risk scenario, corresponding to a 0.5% increase in A1–A3 GWP. This modest variation highlights that, although steel is a carbon-intensive material, its relative share in the total material mix is not sufficient to drive a substantial increase in the building’s embodied carbon. Moreover, as highlighted in [12], the building is already overbuilt for the seismic zone in which it is located, meaning that the additional strengthening required for Zone 2 is applied on top of an exceptionally resilient baseline structure. This further explains why the relative increase in embodied carbon remains limited, while reinforcing the importance of focusing the analysis on structural components as the most sensitive to regulatory and contextual constraints.

Table 8.

Comparison of GWP impacts between the baseline scenario (Zone 3) and the higher seismic risk scenario (Zone 2, +14% steel in load-bearing structures), expressed as total impact (kg CO2 eq), per unit of useful floor area (kg CO2 eq/m2 UFA), and discrepancy from the baseline (%).

Figure 9.

GWP impact (kgCO2 eq/m2 UFA) reported for each building element assessed in the baseline scenario and in the scenario considering the building located in a higher seismic risk zone (zone 2).

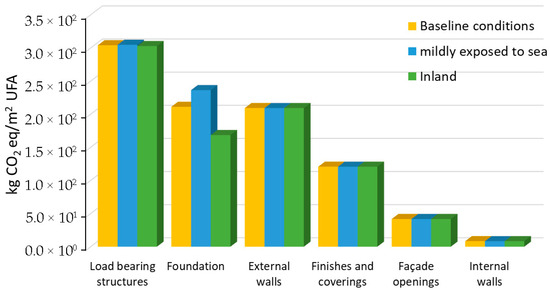

3.2.2. Comparison 2: Exposure Class Change

The comparison between the baseline building, designed with C35/45 concrete in exposure class XS3, against two alternative scenarios is show in Table 9 and Figure 10. The exposure class XS3 is typically specified for structures in tidal, splash, or spray zones directly exposed to seawater, where resistance to chloride ingress under cyclic wetting and drying is critical; in this case, however, the building is already over-specified for its coastal location, reflecting the enhanced structural resilience noted earlier. When the concrete is instead assumed to be C35/45 XS1, a class used in coastal areas exposed to airborne salt but without direct seawater contact, the total GWP rises to 1,003,157 kg CO2 eq (921.37 kg CO2 eq/m2 UFA), a 2.7% increase compared to the baseline. By contrast, relocating the building inland allows the use of C30/37 XC3 concrete, a class suitable for moderate humidity conditions without chloride exposure, which reduces the GWP to 927,275 kg CO2 eq (851.67 kg CO2 eq/m2 UFA), a 4.5% decrease relative to the baseline. The counterintuitive result that XS1 shows higher impacts than XS3 can be explained by differences in data sources and mix design assumptions: the XS3 values are derived from a study on Italian concrete types and impacts [24], which reports industry-average datasets, while the XS1 values are taken from a specific EPD [25] that reflects a CEM I-based mix with high clinker content. As a result, the XS1 dataset carries a higher embodied carbon intensity despite representing a less severe exposure class. This highlights the sensitivity of results to data quality and source selection, underlining the importance of consistent dataset use when comparing scenarios.

Table 9.

GWP comparison for structural concrete across exposure scenarios: baseline seaside (C35/45 XS3), mildly exposed coastal (C35/45 XS1), and inland (C30/37 XC3), reported as total impact (kg CO2 eq), per unit of useful floor area (kg CO2 eq/m2 UFA) and discrepancy from baseline (%).

Figure 10.

GWP impact (kgCO2 eq/m2 UFA) reported for each building element assessed in the baseline scenario, in the scenario considering the building located in an area mildly exposed to seawater sprays and in the scenario where the building is located in an inland area.

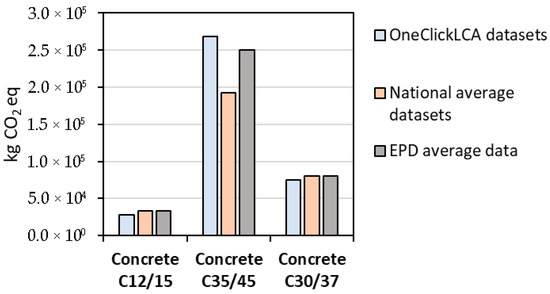

3.3. Impact of Concrete Dataset Choice

To assess the influence of dataset granularity on impact results, a comparative analysis of multiple concrete datasets was conducted. As shown in Table 10 and Figure 11, the reported Global Warming Potential (GWP) intensity of structural concretes varies significantly depending on the source of the data. For C12/15, values range from 154 kg CO2 eq/m3 (OneClick LCA generic dataset) to 196 kg CO2 eq/m3 (Arcadia national dataset) and 186 kg CO2 eq/m3 (EPD averages). For C30/37, the spread is even more pronounced, with the OneClick LCA dataset reporting the highest value (382 kg CO2 eq/m3), compared to 205 kg CO2 eq/m3 in Arcadia and 294 kg CO2 eq/m3 in the EPD averages. For C35/45, the three sources are closer but still divergent, with 277 kg CO2 eq/m3 (OneClick LCA), 274 kg CO2 eq/m3 (Arcadia), and 357 kg CO2 eq/m3 (EPD averages). These discrepancies highlight the sensitivity of embodied carbon results to data source and granularity: generic datasets may over- or under-estimate impacts depending on modelling assumptions, national averages capture broader industry practices, and EPDs reflect specific production choices and clinker contents. The analysis confirms that data selection can substantially influence the magnitude of reported impacts, which is particularly critical when assessing structural concrete, the dominant contributor to the building’s embodied carbon.

Table 10.

GWP intensity of structural concretes expressed per cubic metre (kg CO2 eq/m3), reported using three levels of data granularity: generic OneClick LCA datasets, national average datasets, and average across different EPD datasets.

Figure 11.

Comparison of GWP values for structural concretes (C12/15, C30/37, C35/45) across three data sources: generic datasets from OneClick LCA modelling, national average datasets from [13], and average across different EPDs.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The results of this study clearly demonstrate that structural elements, namely load-bearing structures and foundations, dominate the embodied carbon profile of the building, accounting for approximately 60% of the total GWP impacts (A1–A3). This finding is consistent across both the element-based and material-based breakdowns, where concrete and steel emerge as the most impactful contributors. Such dominance highlights a major opportunity for decarbonisation strategies targeted at structural components, whether through material efficiency, design optimisation, or the adoption of lower-carbon alternatives such as concretes with higher levels of recycled aggregates or innovative binders. Given that structural elements are essential and non-substitutable in terms of building safety and performance, they also represent the most effective leverage points for reducing embodied carbon at scale.

At the same time, the analysis highlights the sensitivity of results to data sources and modelling choices. As shown in the comparison of concrete datasets, reported GWP values vary substantially depending on whether generic software datasets, national averages, or specific EPDs are used. In some cases, less severe exposure classes (e.g., XS1) even appeared to carry higher impacts than more stringent ones (e.g., XS3), a discrepancy that may be explained by differences in composition but also by dataset provenance. This variability highlights the need for greater transparency, harmonisation and uncertainty analysis in embodied carbon assessments, particularly when results are used to inform benchmarks or policies.

From a national perspective, these findings are highly relevant for Italy, where the absence of a comprehensive WLC methodology coincides with the ongoing revision of the CAM and GPP frameworks. The evidence that structural elements dominate embodied carbon suggests that Italian benchmarks should prioritise structural design choices and material specifications as key levers for decarbonisation. At the European level, the study contributes to the broader debate on how to establish robust and comparable WLC benchmarks across Member States. Countries that, like Italy, have not yet adopted a national framework can draw on this research to understand the importance of integrating territorial factors such as seismic and climatic zoning into archetype selection, ensuring that benchmarks reflect the diversity of building practices and regulatory contexts.

In addition, this study suggests that a more systematic evaluation of the national building stock, with particular attention to how structural features required for seismic design influence embodied carbon, would provide a clearer picture of the variability of GWP values across different contexts. Such an approach would not only capture the territorial diversity of Italy but also enable the definition of realistic and achievable decarbonisation targets at national scale. By linking structural safety requirements with carbon performance, policymakers could better balance resilience and sustainability, ensuring that benchmarks reflect both regulatory obligations and climate goals. This line of inquiry could also serve as a model for other EU Member States with heterogeneous building stocks and region-specific design constraints.

It is also important to acknowledge the limitations of this study. The life cycle assessment was conducted with a reduced scope, focusing only on the product stage (A1–A3) and end-of-life processes. Excluding other life cycle stages, such as construction (A4–A5), use (B1–B7), and potential benefits beyond the system boundary (D), means that the results cannot be interpreted as a full whole-life carbon profile. Moreover, the reliance on secondary datasets introduces uncertainty, especially given the high variability observed for structural concrete. A more comprehensive analysis would require systematic uncertainty quantification and sensitivity testing across multiple data sources, and the inclusion of additional life cycle stages. Despite these limitations, the findings provide a strong indication that structural elements are the primary drivers of embodied carbon in residential buildings. This reinforces the importance of focusing decarbonisation efforts on structural design and material choices, while also improving the robustness of LCA studies through better data quality, transparency, and expanded system boundaries.

Future research should extend the proposed framework to other building typologies (e.g., offices, schools, healthcare facilities), explore the integration of social indicators such as worker safety, and test the transferability of the Italian case to other EU Member States with diverse territorial conditions. In doing so, this work contributes not only to the Italian debate but also to the EU-wide effort to establish robust, context-sensitive WLC benchmarks that can guide both national regulation and European decarbonisation strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.P.; methodology, E.P.; software, E.P. and I.M.; validation, E.P. and B.S.-V.; formal analysis, E.P. and I.M.; investigation, E.P. and I.M.; resources, E.P.; data curation, E.P. and I.M.; writing—original draft preparation, E.P.; writing—review and editing, E.P. and I.M.; visualization, E.P. and I.M.; supervision, E.P.; project administration, E.P.; funding acquisition, E.P. and B.S.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This publication is part of the following project: Grant PID2022-137650OB-I00, funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by FEDER, EU.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated and results obtained in this study are fully reported within the article. No additional data are available. For any further information, readers are encouraged to contact the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

E.P. and B.S-V thanks the MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and FEDER, EU for fundings the project: Grant PID2022-137650OB-I00. The authors would like to express their gratitude to Studio INTRE, the civil engineering firm who designed the building analysed in this contribution, for their time, availability and expertise. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Microsoft Copilot to improve language and readability. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BoQ | Bill of Quantities |

| CAM | Criteri Ambientali Minimi (Minimum Environmental Criteria) |

| CML | Centrum voor Milieukunde Leiden (Institute of Environmental Sciences, Leiden University) |

| EN | European Norm (European Standard) |

| EPBD | Energy Performance of Buildings Directive |

| EPC | Energy Performance Certificate |

| EPD | Environmental Product Declaration |

| FU | Functional Unit |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| GPP | Green Public Procurement |

| GWP | Global Warming Potential |

| HDD | Heating Degree Days |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| JRC | Joint Research Centre (European Commission) |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| NZEB | Nearly Zero Energy Building |

| PEF | Product Environmental Footprint |

| UFA | Useful Floor Area |

| WLC | Whole Life Carbon |

References

- United Nations Environment Programme; Global Alliance for Buildings and Construction. Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction 2024/2025; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament. Amendments 14/03/2023 for Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (Recast). 2023. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2023-0068_EN.html#title1 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- ISO 21678:2020; Sustainability in Buildings and Civil Engineering Works—Indicators and Benchmarks—Principles, Requirements and Guidelines. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- De Wolf, C.; Cordella, M.; Dodd, N.; Byers, B.; Donatello, S. Whole life cycle environmental impact assessment of buildings: Developing software tool and database support for the EU framework Level(s). Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 188, 106642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, N.; Donatello, S.; Cordella, M. Level(s) Indicator 1.2: Life Cycle Global Warming Potential (GWP) User Manual: Introductory briefing, Instructions and Guidance (Publication Version 1.1); Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Sicurezza Energetica. Criteri Ambientali Minimi (CAM)—Green Public Procurement (GPP); Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Sicurezza Energetica: Rome, Italy, 2024. Available online: https://gpp.mase.gov.it (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- EN 15978:2011; Sustainability of Construction Works—Assessment of Environmental Performance of Buildings—Calculation Method. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2011.

- Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Sicurezza Energetica. Criteri Ambientali Minimi (CAM) per le Infrastrutture Stradali—Testo Consolidato con Correttivo del 25/09/2025; Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Sicurezza Energetica: Rome, Italy, 2025. Available online: https://www.mase.gov.it/portale/documents/d/guest/cam_strade_testo_consolidato_correttivo_25-09-25-pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Tozan, B.; Hoxha, E.; Birgisdottir, H.; Sørensen, C.G.; Andersen, C.M.E.; Garnow, A.; Kragh, J.; Rose, J.; Olsen, C.O. A novel approach to establishing bottom-up LCA-based limit values for new construction. Build. Environ. 2024, 263, 111891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency—Energy in Buildings and Communities Programme (IEA-EBC). International Survey of Mandatory Whole Life/Embodied Carbon Requirements in Building Codes and Regulations. Working Group on Building Energy Codes. 2025. Available online: https://www.iea-ebc.org/Data/publications/EBC_WG_BECs_Mandatory_Whole_Life_Embodied_Carbon_Report_June_2025.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Lavagna, M.; Baldassarri, C.; Campioli, A.; Giorgi, S.; Valle, A.D.; Castellani, V.; Sala, S. Benchmarks for environmental impact of housing in Europe: Definition of archetypes and LCA of the residential building stock. Build. Environ. 2018, 145, 260–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervasio, H.; Dimova, S.; Pinto, A. Benchmarking the life-cycle environmental performance of buildings. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soust-Verdaguer, B.; García-Martínez, A.; Rey-Álvarez, B.; de Diego, B.; de la Fuente, A.; Röck, M. Data infrastructure for whole-life carbon emissions baselines of buildings in Spain. Energy Build. 2025, 347, 116307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Seville; GBC España. INDICATE Spain. 2025. Available online: https://gbce.es/proyectos/indicate-spain/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Ramboll; BPIE; KU Leuven. Towards an EU Roadmap for Reduction of Whole Life Carbon in Buildings; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; Available online: https://c.ramboll.com/whole-life-carbon-reduction (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- One Click LCA. One Click LCA [Software]. 2023. Available online: https://www.oneclicklca.com (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Palumbo, E.; Mazzei, I.; Pomponi, F. Integration of Seismic and Climate-related Constraints for WLC Benchmark Definition of Italian Residential Buildings. In Proceedings of the Sustainable Built Environment Conference WestMED Seville 2025, Seville, Spain, 22–24 October 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Di Bari, R.; Belleri, A.; Marini, A.; Horn, R.; Gantner, J. Probabilistic Life-Cycle Assessment of Service Life Extension on Renovated Buildings under Seismic Hazard. Buildings 2020, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin, F.S.; Martinez-Vazquez, P.; Baniotopoulos, C. An Integrated Method to Evaluate Sustainability for Vulnerable Buildings Addressing Life Cycle Embodied Impacts and Resource Use. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, L.; Palumbo, E.; Coffetti, D.; Panozzo, C.; Rapelli, S.; Cellurale, M.; Rinaldi, C. Studio LCA Della Filiera del Calcestruzzo e Degli Aggregati Riciclati; ENEA: Rome, Italy, 2025; Available online: https://www.pubblicazioni.enea.it/le-pubblicazioni-enea/edizioni-enea/anno-2025/studio-lca-della-filiera-del-calcestruzzo-e-degli-aggregati-riciclati.html (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- JSC Betono centras. Environmental Product Declaration: Ready-Mixed Concrete C35/45; The International EPD® System: Stockholm, Sweden, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Environmental Sciences (CML), Leiden University. CML-IA Characterisation Factors; Leiden University: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2016; Available online: https://www.universiteitleiden.nl/en/research/research-output/science/cml-ia-characterisation-factors (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- European Commission. Product Environmental Footprint (PEF) Guide; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2013; Available online: https://green-forum.ec.europa.eu/green-business/environmental-footprint-methods/pef-method_en (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- UNI/TS 11300; Energy Performance of Buildings—Parts 1–4: Determination of Thermal, Primary Energy Needs and System Efficiencies for Space Heating and Cooling, Domestic Hot Water Production, Ventilation and Lighting. UNI: Milan, Italy, 2021.

- Norcem, A.S. Ready Mixed Concrete C35/45 SCC CEM I (XD1, XS1, XS2, XF2, XF3, XA2); Environmental Product Declaration NEPD 8794 8456; EPD Norge: Oslo, Norway, 2022; Available online: https://digi.epd-norge.no/getfile.php/13231672-1752478441/EPDer/Byggevarer/Ferdig%20betong/NEPD-8794-8456_Ready-mixed-concrete-C35-45-SCC-CEM-I--XD1--XS1--XS2--XF2--XF3--XA2-.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).