1. Introduction

The Internet of Things (IoT) is expanding rapidly across areas such as smart cities, healthcare, and industrial automation, where billions of small, resource-constrained devices need to communicate over low-power and lossy networks (LLNs) [

1,

2]. To support such communication, the IETF developed the IPv6 Routing Protocol for LLNs (RPL) [

3]. Although RPL is widely adopted for its adaptability and energy efficiency, it was not designed with strong built-in security. This leaves it open to a range of well-documented attacks including the Version Number Attack (VNA), Rank manipulation, Sinkhole, selective forwarding, and Hello Flooding [

4,

5,

6,

7]. These attacks can degrade packet delivery, inflate control overhead, and destabilise routing, with serious consequences for critical IoT applications.

Researchers have responded by proposing a variety of security-enhanced versions of RPL. For example, CDRPL employs cryptographic techniques to defend against Rank attacks [

8], DVN-SRPL validates version number updates to contain VNAs [

9], and SRPL-RP incorporates replay protection mechanisms [

10]. Trust-based routing schemes [

11,

12] and lightweight anomaly detection methods [

13] have also been developed. While each of these approaches adds value, they tend to share three limitations: they are designed to tackle specific attacks rather than providing broad protection, they rely on local detection without global auditability, and in many cases, they increase energy consumption or delay to levels that are unsustainable for constrained devices.

Blockchain has been suggested as a way to improve trust in IoT systems [

14,

15,

16,

17]. It offers tamper-resistant logging, decentralised consensus, and verifiable record-keeping, which could enhance accountability in IoT routing. However, many existing blockchain approaches for IoT rely on public consensus algorithms such as Proof-of-Work or Proof-of-Stake [

18], which are too resource-intensive for LLNs. By contrast, permissioned blockchains using Byzantine Fault Tolerant consensus protocols—such as Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance (PBFT) and its derivative, Istanbul BFT (IBFT) [

19,

20]—are more appropriate, since they achieve faster confirmation times and can tolerate collusion among a minority of validators. Yet so far, only limited attempts have been made to combine blockchain with RPL security.

Our earlier work on IbiboRPLChain [

21] provided a first step towards this goal, showing that blockchain could be used to mitigate VNAs in RPL. However, its reliance on blockchain-only validation introduced additional delay and energy cost. In this paper, we build on that foundation with IbiboRPLChain II. The new model expands the attack coverage to include VNAs, Rank, replay, and Hello Flooding attacks; introduces a dual validation mechanism that combines lightweight Hop-by-Hop checks with smart contract verification; and deploys a permissioned IBFT-2.0 blockchain to strengthen consensus among validators. This design strikes a balance between maintaining low energy and delay at constrained motes while enabling global auditability and forensic traceability through the blockchain.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows.

Section 2 reviews the related literature and situates IbiboRPLChain II in the context of prior work.

Section 3 outlines the design of the proposed solution, including its dual validation mechanisms and blockchain integration, threat model, and security assumptions.

Section 4 presents the experimental setup and reports results on packet delivery, delay, control overhead, and energy consumption, with comparisons to existing approaches.

Section 5 Results and Performance Evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed IbiboRPLChain II framework.

Section 6 concludes the paper and highlights directions for future work.

1.1. Problem Statement

As the IoT ecosystem continues to expand, the underlying communication protocols that support it face increasing scrutiny. Among the most widely adopted is the RPL, which was designed specifically to meet the requirements of resource-constrained and unstable network environments such as WSNs and smart city deployments [

22]. However, while RPL offers scalability and low overhead, it was not originally architected with a strong security posture, particularly in defending against insider threats.

RPL operates using control messages (DIO, DAO, DIS) to construct and maintain a DAG structure, forming the basis for upward and downward routing. These control messages are trust-based and lack cryptographic guarantees, making them susceptible to manipulation by compromised nodes. The protocol assumes that participating nodes behave honestly, which is often not the case in adversarial settings [

23].

1.2. Vulnerabilities in RPL

Several classes of attacks exploit RPL’s inherent trust model:

Version Number Attacks (VNA): Malicious nodes advertise higher version numbers to illegitimately trigger global re-routing, causing energy drain and service disruption [

24].

Hello Flooding Attacks (HFA): Attackers broadcast HELLO messages with high frequency, tricking neighbouring nodes into attempting to establish links, thereby draining their energy resources [

10].

Rank Attacks: By advertising falsified rank values, a malicious node can position itself closer to the root, thereby attracting and dropping or misrouting traffic [

25].

Sinkhole and selective forwarding: These attacks manipulate routing paths to intercept or selectively drop packets, jeopardising the confidentiality and availability of data [

26].

Due to the lack of route authentication and integrity checks, RPL remains vulnerable to these attacks, especially in the context of multi-hop and unattended deployments, such as environmental monitoring and industrial control systems.

1.3. Limitations of Existing Solutions

Numerous mitigation strategies have been proposed in the literature, including the following: (1) watchdog mechanisms to monitor packet forwarding behaviour, (2) reputation systems to rate node trustworthiness, and (3) lightweight encryption and authentication protocols.

However, these approaches suffer from several critical limitations: Resource Overhead—Many solutions assume the availability of computational and memory resources, which are unrealistic for battery-powered IoT devices; Centralised Trust Models—Approaches based on centralised verification or certificate authorities introduce single points of failure and limit scalability [

27], and the Partial Coverage—Many solutions address only specific attack types (e.g., VNA or Rank manipulation), leaving the network exposed to multi-vector attacks.

Furthermore, these mechanisms typically lack auditability and tamper-resistance, which are essential in applications requiring compliance, traceability, and forensic analysis.

1.4. Research Gap

There is a pressing need for a lightweight, decentralised, and tamper-proof security architecture that can perform the following:

Defend against multiple classes of routing attacks,

Operate within the severe constraints of LLNs,

Eliminate reliance on centralised control entities,

Provide an audit trail for routing decisions and security events.

Our previous work on IbiboRPLChain introduced the concept of using blockchain and smart contracts to authenticate routing events in RPL [

21]. While this system demonstrated feasibility, it lacked a layered defence architecture, did not offer node role differentiation, and was not benchmarked under variable topologies and conditions. Hence, there exists a clear need for a next-generation blockchain-based framework such as the proposed IbiboRPLChain II, that integrates multi-role nodes, composite defence layers, and scalable verification mechanisms, all while being compatible with the computational realities of IoT hardware.

3. Proposed Methodology

The proposed IbiboRPLChain II framework introduces a composite, decentralised, and role-based architecture to secure IPv6 RPL-based IoT networks against internal routing threats, particularly Version Number Attacks (VNAs). It extends the original IbiboRPLChain solution by incorporating multiple defence layers, integrating blockchain technology, and supporting lightweight smart contract execution within constrained environments. The overall architectural design of the system is illustrated in

Figure 1, which outlines the interaction between the IoT topology, smart contracts, and the blockchain ledger. Sensor nodes (labelled N1) initiate requests such as DODAG Information Solicitation (DIS) messages, which are routed through parent nodes (P1) and forwarded to the smart contract layer for authentication. The smart contract module handles node registration, authentication, verification, and access control. If the request passes the security policy encoded within the contract, the response is returned to the requesting node, and a permanent log is written to the blockchain for transparency and future reference.

To enhance scalability and security, the framework adopts a multi-layered network architecture comprising three distinct operational layers: the sensor layer, gateway layer, and routing layer. This design is captured in

Figure 2, which presents the proposed IbiboRPLChain II solution in a structured hierarchy. The sensor layer consists of normal IoT nodes responsible for data sensing and basic routing functions. The gateway layer bridges sensor nodes to higher-tier routing infrastructure, while the routing layer interfaces directly with the blockchain platform. Two critical components, smart contracts and node storage, operate within this blockchain platform. These components are responsible for processing authentication logic and managing trusted records of node behaviour. Communication between layers is conducted through secure, radio-based transmission paths, where only selected nodes participate in blockchain interactions to conserve energy and bandwidth.

At the core of the framework is an event-driven smart contract system designed to autonomously manage routing validation tasks. The implementation of this mechanism is shown in

Figure 3, which presents the functional relationship between parent nodes, child nodes, and the blockchain smart contract. A parent node, programmed using C++ and compiled via Emscripten, sends the version number (VN) to the blockchain via a Web3.js interface. The smart contract validates the version number and broadcasts the verified result to downstream child nodes in a read-only manner. This implementation decouples security logic from routing logic, allowing dynamic and autonomous validation without relying on central authorities.

The methodology incorporates three security layers. The first layer, Smart Contract Validation, ensures that all routing updates are subject to predefined logic embedded in smart contracts. The second layer, Blockchain Logging, records network events on an immutable ledger, enabling tamper-proof auditing and retrospective analysis of malicious behaviour. The third layer, Hop-by-Hop Authentication, validates each control message at every hop, ensuring that unauthorised or malicious updates are immediately dropped. These layers are designed to be modular and selectively deployable, offering flexibility in resource-constrained environments. For instance, smaller networks may activate only the smart contract layer, while larger, more vulnerable environments can utilise all three in a composite configuration.

The full operational workflow begins when a new node seeks to join the RPL network. It broadcasts a DIS message, which is captured by neighbouring nodes and passed to the authentication layer. If validated, the parent node responds with a DIO message. This message is forwarded to a smart contract agent that checks version number integrity and parent legitimacy. If the information is consistent with the blockchain records, the smart contract authorises the action and logs it. Throughout the process, authentication agents monitor and validate control packets to prevent on-the-fly manipulation. Validator nodes then maintain consensus across the ledger and monitor for anomalies in routing patterns.

This proposed methodology provides several advantages. It ensures scalability by distributing the security burden across designated roles; improves energy efficiency by limiting blockchain operations to selected nodes; enables real-time attack detection via event-triggered smart contracts; and delivers tamper-proof auditability through immutable blockchain logging. The role-based, decentralised nature of IbiboRPLChain II ensures that even in the event of node compromise, the system retains its ability to detect and isolate malicious routing behaviour without requiring full network reconfiguration. Moreover, the layered defence design provides resilience and adaptability, making the framework well-suited for deployment in a wide range of IoT scenarios, from small-scale environmental monitoring to large smart city infrastructures.

3.1. Threat Model

Adversary Definition: We formally define the adversary, denoted

, as an insider entity capable of joining the RPL network with valid link-layer credentials or by compromising existing nodes. Unlike an outsider adversary, who may only eavesdrop or jam at the physical layer,

is assumed to participate legitimately in routing operations while intentionally deviating from protocol compliance in order to disrupt control-plane stability or degrade data-plane performance. This aligns with the class of attacks described in existing RPL taxonomies, including version number inflation, Hello Flooding, rank falsification, and Sinkhole or selective forwarding behaviours [

8,

9,

10,

24,

26].

Adversarial Capabilities: We assume that

may compromise up to mmm sensor nodes within the low-power and lossy network (with m = 3 m = 3 m = 3 in our experimental setup). Each compromised node may (i) forge or replay RPL control messages (DIO, DIS, DAO) with manipulated fields, (ii) increase transmission frequency to induce congestion and energy exhaustion, (iii) advertise artificially advantageous routing metrics (e.g., lower rank) to attract traffic, and (iv) selectively drop or reroute data packets. The adversary does not possess validator private keys and therefore cannot generate forged blockchain consensus messages, but may collude across its compromised devices to amplify the scope of disruption. Attacks at the physical layer (e.g., jamming, link-quality manipulation) and Root Node compromise are explicitly excluded from this model [

28,

29].

Security Assumptions: We scope the system under a permissioned blockchain model in which

validators operate Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance (PBFT) consensus [

33]. We assume that at most

validators may be Byzantine or colluding, with the standard bound

guaranteeing safety and liveness. Validators are therefore not considered absolutely trustworthy, but may be compromised up to this threshold [

23]. Authentication agents embedded in the RPL topology are assumed to operate correctly unless captured by

; in such cases, cross-validation with neighbouring agents and blockchain verification mitigates unilateral misreporting. Finally, event validation delays

) are assumed to remain below the active Trickle interval or the median convergence time of the network, ensuring that malicious updates cannot propagate globally before being detected and neutralised [

32,

33].

Validator trust, compromise and collusion: The validator set explicitly allows collusion up to the PBFT threshold. Validators are not a priori trustworthy: any subset of size

may deviate arbitrarily (equivocate, censor, or vote inconsistently). Safety and liveness assumptions follow the PBFT condition

. If a validator is compromised, consensus safety is preserved provided the number of faulty validators does not exceed

. Compromise is modelled as key-level control of the validator by the adversary; mitigations include quorum enforcement, auditable misbehaviour logging, and membership reconfiguration [

5,

17,

23,

34,

35]. Consequently, our security claims hold only while the colluding validator count remains

validators collude, the adversary can subvert or stall decisions and the system degrades to best-effort auditing rather than authoritative prevention.

Table 2 summarises the threat model [

21,

22,

23], corresponding detection and mitigation mechanisms, and the measured detection performance of IbiboRPLChain II under various adversarial scenarios. Each threat type represents a common routing-layer vulnerability in RPL-based IoT networks, such as version manipulation, rank falsification, replay of stale messages, or packet dropping attacks. The proposed framework employs a dual-layer approach combining Hop-Auth, a lightweight hop-level authentication mechanism, with blockchain-based validation through smart contracts to ensure data integrity and accountability across the network.

The table reports precision and recall metrics derived from logged detection events benchmarked against known adversarial behaviour. High precision values (92–96%) indicate that benign routing events are rarely misclassified as attacks, thus preventing unnecessary route repairs and maintaining low AE2ED (Average End-to-End Delay). Similarly, recall rates (89–95%) demonstrate strong sensitivity to actual attack events, ensuring that most malicious behaviours are successfully detected, thereby sustaining high packet delivery ratios (PDR). However, slight degradation in detection performance is observed in Sinkhole and Hello Flooding attacks, where intermittent forwarding or high network density can obscure anomalies.

Overall, IbiboRPLChain II exhibits consistent and robust detection performance across multiple attack scenarios, achieving an effective balance between accuracy and efficiency. The integration of blockchain auditing enhances trust and transparency, while Hop-Auth provides lightweight, distributed protection suitable for constrained IoT environments.

3.2. Hop-Level Authentication (Hop-Auth)

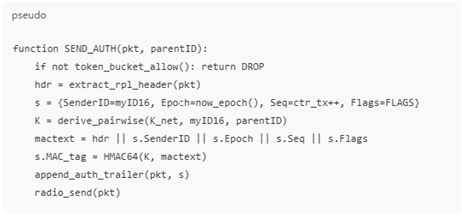

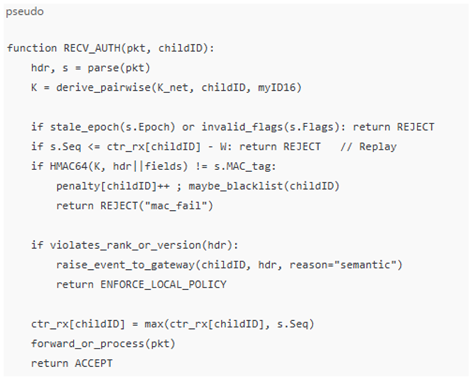

To ensure robust protection against insider manipulation of RPL control traffic, we implement Hop-Auth, a lightweight Hop-by-Hop authentication mechanism. This section specifies its design in terms of per-node state, per-packet overhead, minimal pseudocode, and failure handling.

Each node maintains only O(1) additional state:

K_net: network master key (used for pairwise derivation only).

K_parent: symmetric key with the current parent, derived as

K_children[childID]: pairwise keys with children (small map).

ctr_tx: local monotonic transmit counter (16-bit).

ctr_rx[parentID]: replay window for packets received from a parent (W = 32).

epoch: coarse-grained epoch counter (1 s ticks).

penalty[ID] and rl_tokens: used for rate-limiting and blacklisting misbehaving neighbours.

This state requires less than 500 B RAM on TelosB/Sky-class motes.

Hop-Auth appends a 14-byte trailer to RPL control packets:

| Field | Size (Bytes) | Notes |

| SenderID | 2 | 16-bit short ID (6LoWPAN context) |

| Epoch | 1 | Coarse time value to bound replay window |

| Sequence | 2 | 16-bit monotonic counter |

| Flags | 1 | Key version/type options |

| MAC_tag | 8 | Truncated HMAC-SHA256 tag (64-bit) |

| Total | 14 | Fits within 127-byte IEEE 802.15.4 MTU |

This overhead ensures compatibility with constrained LLNs while maintaining cryptographic integrity.

Sender:

Receiver:

Table 3 outlines the key failure modes and edge cases identified during the evaluation of IbiboRPLChain II, along with the corresponding mitigation or handling strategies. These cases represent potential operational vulnerabilities that may arise under realistic IoT network conditions such as packet reordering, node mobility, or temporary loss of connectivity. The framework integrates both proactive and reactive mechanisms to maintain resilience and system continuity [

10,

22,

23,

24].

For transient issues like replay within a valid window or epoch skew caused by minor clock drift, the system applies controlled tolerance—accepting packets within a defined time or sequence range to prevent unnecessary packet loss. Key desynchronisation during parent switching or rollover is addressed by enabling short dual-key overlap periods to ensure secure transitions without service interruption. To minimise false positives during network churn, multiple consecutive verification failures are required before flagging a node as suspicious.

At the security layer, denial-of-service attempts are mitigated through token bucket rate-limiting, early MAC-layer rejection, and node blacklisting. Cases of compromised neighbours with valid credentials trigger semantic payload checks and generate a signed alert to the blockchain-based smart contract layer for accountability. Even in cases of temporary chain connectivity loss, local Hop-Auth verification continues to operate independently, buffering events until re-synchronisation. Only catastrophic failures such as root compromise or majority validator collusion are deemed out of scope and would require external attestation mechanisms and governance intervention. Overall, the table illustrates IbiboRPLChain II’s layered fault tolerance and adaptive security design.

This explicit design directly informs our measurement framework. The 14-byte trailer contributes to packet energy overhead, HMAC checks define CPU cost in per-event breakdowns, and precision/recall values in

Table 2 and

Figure 4 are computed from ground truth adversarial events vs. logged MAC/semantic failures [

22]. This ensures that Hop-Auth is not only theoretically specified but also empirically evaluated within the reported results.

4. Experimental Setup

To evaluate the performance, robustness, and scalability of the proposed IbiboRPLChain II framework, simulations were conducted using Contiki OS (v2.7) and the Cooja network simulator, both of which are well-suited for evaluating low-power and lossy networks (LLNs) [

36]. The simulation environment was configured to model realistic IoT conditions using Sky Mote devices, which feature 10 KB RAM, 48 KB flash memory, and a 20 MHz MSP430 microcontroller hardware representative of typical constrained IoT deployments. All nodes communicated over IEEE 802.15.4 at the MAC layer, with RPL in storing mode used for routing over 6LoWPAN on top of IPv6. The Unit Disk Graph Medium (UDGM) with distance loss was used to simulate radio propagation. The complete simulation parameters are detailed in

Table 4 and

Table 5.

All blockchain experiments used the IBFT-2.0 implementation configured via Geth 1.13.x, executed in a local private network environment. Validator nodes were deployed on lightweight virtual machines with stable clock synchronisation (NTP) [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29].

The simulation covered an area of 200 × 200 metres, with 30 randomly deployed nodes, including 3 malicious nodes used to simulate Version Number Attacks (VNAs) by broadcasting artificially incremented version numbers to disrupt network convergence. The transmission range was set to 50 m and the interference range to 100 m, ensuring multi-hop communication with potential for routing ambiguity. Each simulation was run for 600 s and repeated with three distinct random seeds 123456, 284731, and 371902 to ensure consistency and robustness across variable topologies. The Objective Function (OF) used in RPL routing was the one configured for the specific scenario being tested (e.g., OF0 or MRHOF), depending on simulation goals.

Five simulation scenarios were evaluated: (1) baseline RPL without attack, (2) RPL under VNA, (3) Smart Contract Only mode, (4) Authentication Only mode, and (5) full Composite IbiboRPLChain II mode. Each configuration was instrumented with PowerTrace, which tracked CPU activity, transmission energy, and duty cycles to calculate energy consumption [

37].

The Blockchain layer: We deployed a permissioned Ethereum-compatible network using IBFT-2.0 (PBFT-style) [

38] consensus as implemented in the GoQuorum/Besu client, rather than mainline Geth. Four validator nodes

were configured, tolerating

Byzantine fault under the PBFT bound

. Smart contracts, written in Solidity, were invoked by authentication agents through Web3 calls, while on-chain events were monitored by listeners that disseminated security verdicts to RPL nodes. The network was configured with a block time of 2 s, round-change timeout of 3 s (with exponential backoff, maximum 5 rounds), a block gas limit of 10 million, and immediate finality on commit. Transaction retries used a 5 s timeout with exponential backoff (up to three attempts). Event delivery was polled at 250 ms intervals [

17].

Performance was evaluated based on five key metrics: Packet Delivery Ratio (PDR), Average End-to-End Delay (AE2ED), Throughput, Energy Consumption, and Control Packet Overhead. Results were averaged over three runs for statistical significance and benchmarked against established blockchain-enhanced RPL models [

39], such as DVN-SRPL and CDRPL.

This experimental setup ensured the simulation of real-world conditions, including dynamic topologies, interference, and attack propagation. Through this rigorous approach, IbiboRPLChain II’s impact on network reliability, latency, energy efficiency, and overhead was accurately assessed, demonstrating its effectiveness as a composite and adaptable RPL security framework.

The detection outcomes reported in this section are grounded in the Hop-Auth design specified in

Section 3.2, where per-node state, per-packet overhead, and failure handling were defined; thus, the precision, recall, and performance results directly reflect the implemented authentication algorithm.

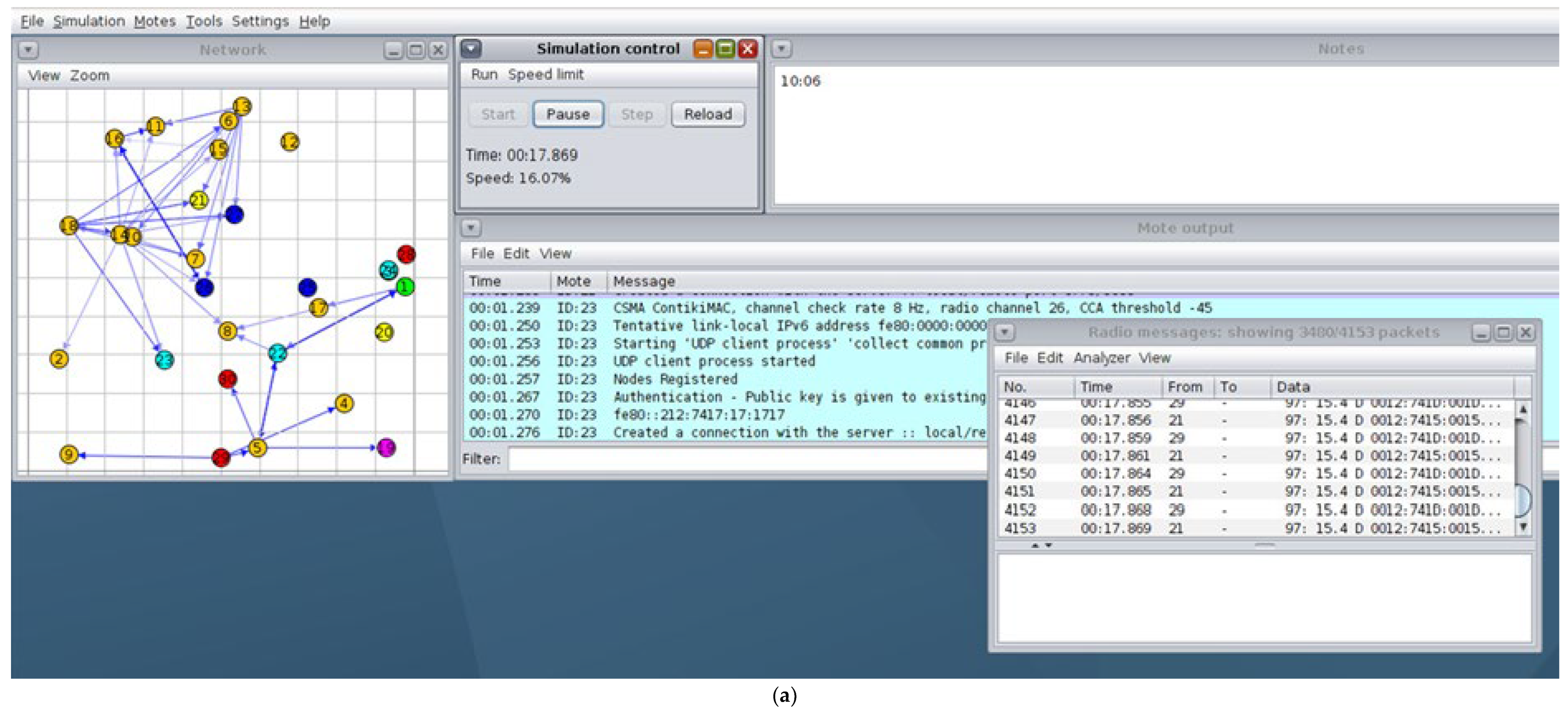

Figure 5a, described as the “Actual Simulation Environment Result,” represents a visual snapshot of the experimental topology within the Cooja/Contiki environment and serves to validate the credibility of the testbed used to evaluate IbiboRPLChain II. In this setup, thirty Sky Mote nodes were randomly distributed across a 200 × 200 m area, each with a 50 m transmission range and a 100 m interference range, thereby ensuring a multi-hop routing structure with realistic contention. Of these nodes, three were designated as malicious actors performing Version Number Attacks (VNAs), deliberately placed to disrupt the Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) by repeatedly broadcasting inflated version numbers and forcing costly re-convergences. The figure is intended to show not only the geographic dispersion of nodes but also the operational stress introduced by attacker placement in relation to the DAG root and legitimate nodes. A back-of-the-envelope analysis supports the realism of this environment: given the deployment density, each node would have on average six neighbours within its transmission range and approximately 24 potential interferers within 100 m, a balance that enables RPL parent churn while also producing credible levels of packet collision and overhead. Thus, the figure underpins the validity of subsequent performance claims by situating results in a setting where both connectivity and interference are realistically exercised. However, in critical depth, the figure remains limited by the lack of explicit annotation—for example, the precise location of the root and attacker nodes, or overlays showing communication and interference radii making it difficult for readers to fully appreciate the severity of the attack scenario or to reproduce the conditions exactly. Furthermore, the reliance on the UDGM radio model simplifies the fading and shadowing effects that are prevalent in real IEEE 802.15.4 environments, potentially underestimating variability in delay and packet loss. Overall, while

Figure 5a provides a necessary grounding for the experimental study and demonstrates that IbiboRPLChain II was evaluated under credible adversarial conditions, its explanatory power could be significantly enhanced by clearer annotation and contextualisation, which would strengthen both the internal validity of the study and its external relevance to real IoT deployments.

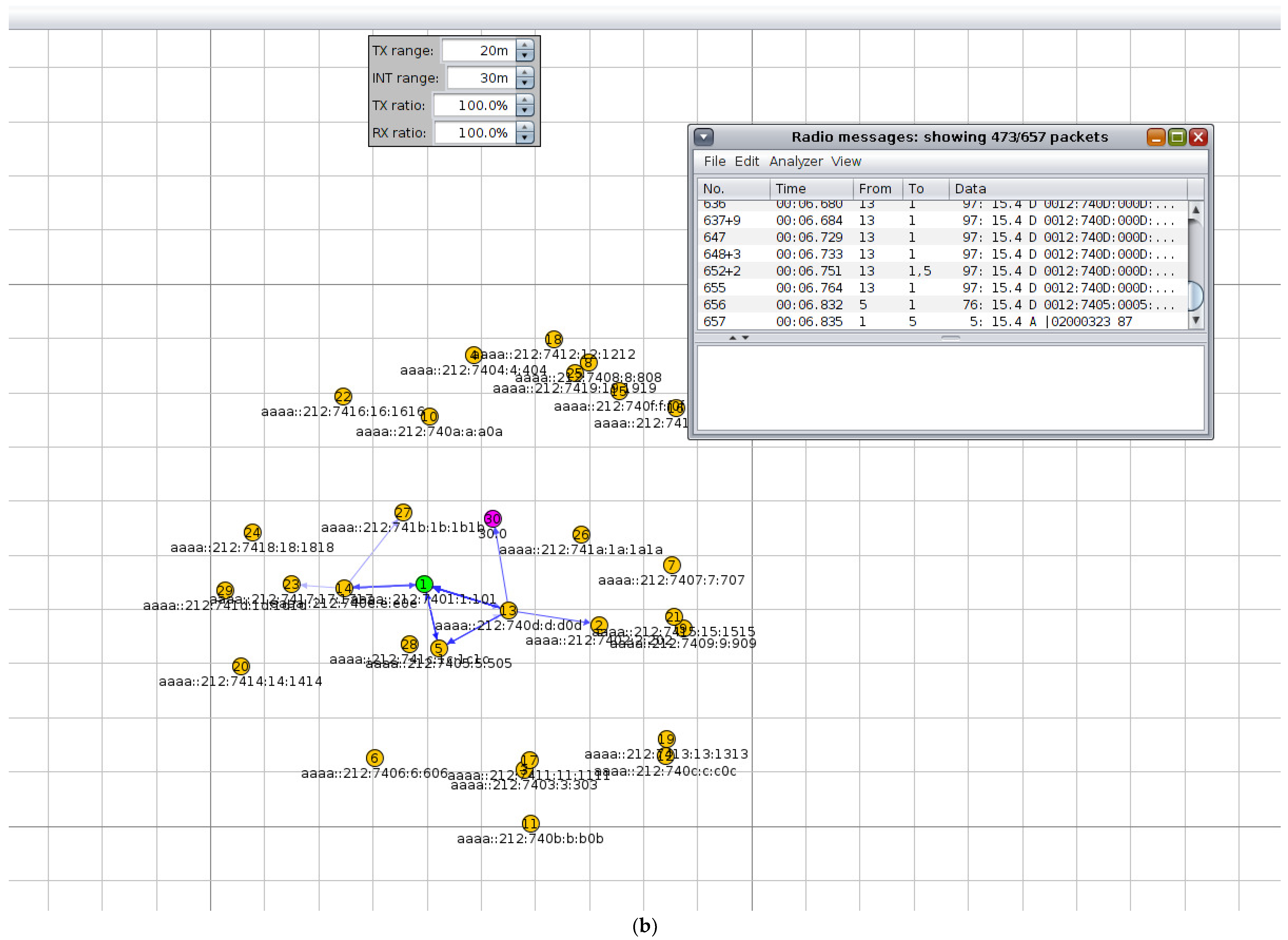

Figure 5b, labelled as the “Actual Simulation Environment Result,” provides a snapshot of the Cooja-based testbed used to validate IbiboRPLChain II under controlled adversarial conditions. In this simulation, 30 Sky Mote devices were randomly deployed across a 200 × 200 m grid, each configured with a 50 m transmission range and a 100 m interference range, parameters that ensured realistic multi-hop connectivity with credible collision likelihood. The figure illustrates the spatial distribution of nodes, including the Root Node at the centre of the DAG and three malicious nodes launching Version Number Attacks (VNAs) by broadcasting falsified high version numbers to trigger repeated global re-convergences. Over a runtime of 600 s, repeated under three random seeds, the setup allowed observation of how such malicious activity destabilises routing, increases control overhead, and drains energy, as later reflected in performance metrics.

In detail,

Figure 5b captures both the randomised placement of sensor nodes and the operational stress imposed by the attackers, highlighting the conditions under which IbiboRPLChain II was benchmarked against DVN-SRPL and CDRPL. Each node’s position implies an average of six neighbours within communication range and approximately two dozen within interference range, thereby reproducing congestion and delay phenomena typical of IEEE 802.15.4 networks. Although the figure primarily serves as a visual grounding for the experimental environment, it could be strengthened by annotation—for example, marking attacker nodes, showing communication radii, or indicating parent–child links within the DAG. Such contextual cues would make it clearer how the geometry enabled VNA disruptions and how the proposed defences mitigated them. Overall,

Figure 5b situates the reader within a credible, interference-prone simulation environment, reinforcing the validity of the performance results reported in the study.

4.1. Sensitivity and Robustness Study

To strengthen the external validity of our findings, we conducted a sensitivity and robustness study that systematically varied parameters across three critical dimensions: consensus configuration, RPL/LLN protocol timers, and channel conditions. We further evaluated operational stressors such as cold start and node rejoin behaviour. Consensus parameters. We varied the block time () between 1 and 5 s, the round-change timeout () between 2× and 5× , and the validator set size () between 4, 7, and 10 nodes. These factors directly affect the latency and stability of blockchain finality, as well as validator-side compute and energy overheads. RPL/LLN protocol timers. At the routing layer, we adjusted Trickle parameters (, , and redundancy constant ), DAO/DIS retries (1–5 attempts), and retransmission timeouts (scaled by ±25%). These variations allowed us to examine the trade-off between convergence speed, control traffic overhead, and resilience to inconsistent advertisements. Channel conditions. To evaluate robustness under degraded links, we applied varying average packet error rates (PER) of 0–30% and introduced burst loss models (Gilbert–Elliott) with both short and long burst patterns. This stresses the system’s ability to maintain stable delivery under realistic lossy conditions. Operational scenarios. Two practical cases were examined: (i) cold start, where all nodes boot simultaneously at , and (ii) rejoin, where 10% of nodes disconnect and rejoin the network mid-simulation. These stressors test the protocol’s ability to re-establish routes and re-synchronise blockchain validation without prolonged disruption. For each parameter set, we measured Packet Delivery Ratio (PDR), average end-to-end delay (AE2ED, including p95 and p99 tails), energy consumption (S, SN, SNE), convergence time, and detection quality (precision and recall). Results are reported as robustness bands (median with p10–p90 envelopes and 95% confidence intervals), and we compute sensitivity coefficients to identify which parameters most strongly influence performance.

4.2. Nomenclature and Units (Consistency)

To ensure clarity and comparability, all metrics and measurement units have been standardised across the text, figures, and tables. The Packet Delivery Ratio (PDR) is now consistently expressed as a percentage (%), Average End-to-End Delay (AE2ED) in seconds (s), and Energy Consumption in Joules (J). Control overheads are reported as packets per minute per node. Statistical reporting has also been harmonised—results are presented as mean ± standard deviation with 95% confidence intervals and, where appropriate, p-values and effect sizes. This ensures uniform interpretation across all result sections. Use the following canonical terms and units everywhere (captions, axes, tables).

Table 6 defines the standardised terminology and measurement units used consistently throughout the study to enhance clarity, comparability, and reproducibility. Key performance metrics are harmonised: PDR is expressed as a percentage (%), AE2ED in seconds (s), and energy in Joules (J). Control overhead is reported as packets per minute per node, ensuring uniform interpretation across experiments. Additionally, operational modes such as Hop-Auth, Smart-Contract, and Composite are standardised to clearly distinguish between local and blockchain-assisted authentication mechanisms [

17,

23]. All results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) with 95% confidence intervals, aligning the reporting format with scientific best practices for statistical transparency.

4.3. Figure Annotation Checklist (Topology/Flow Figures)

Each diagram now clearly identifies node roles (root, parent, child, and gateway), attacker IDs (A1–A3), and radio transmission ranges using visual overlays. Captions include specific simulation details—such as radio model, area size, and random seed—to make the experimental setup fully transparent [

36,

39,

40,

41]. These updates make the network structure and attack placement visually clear and easy to replicate.

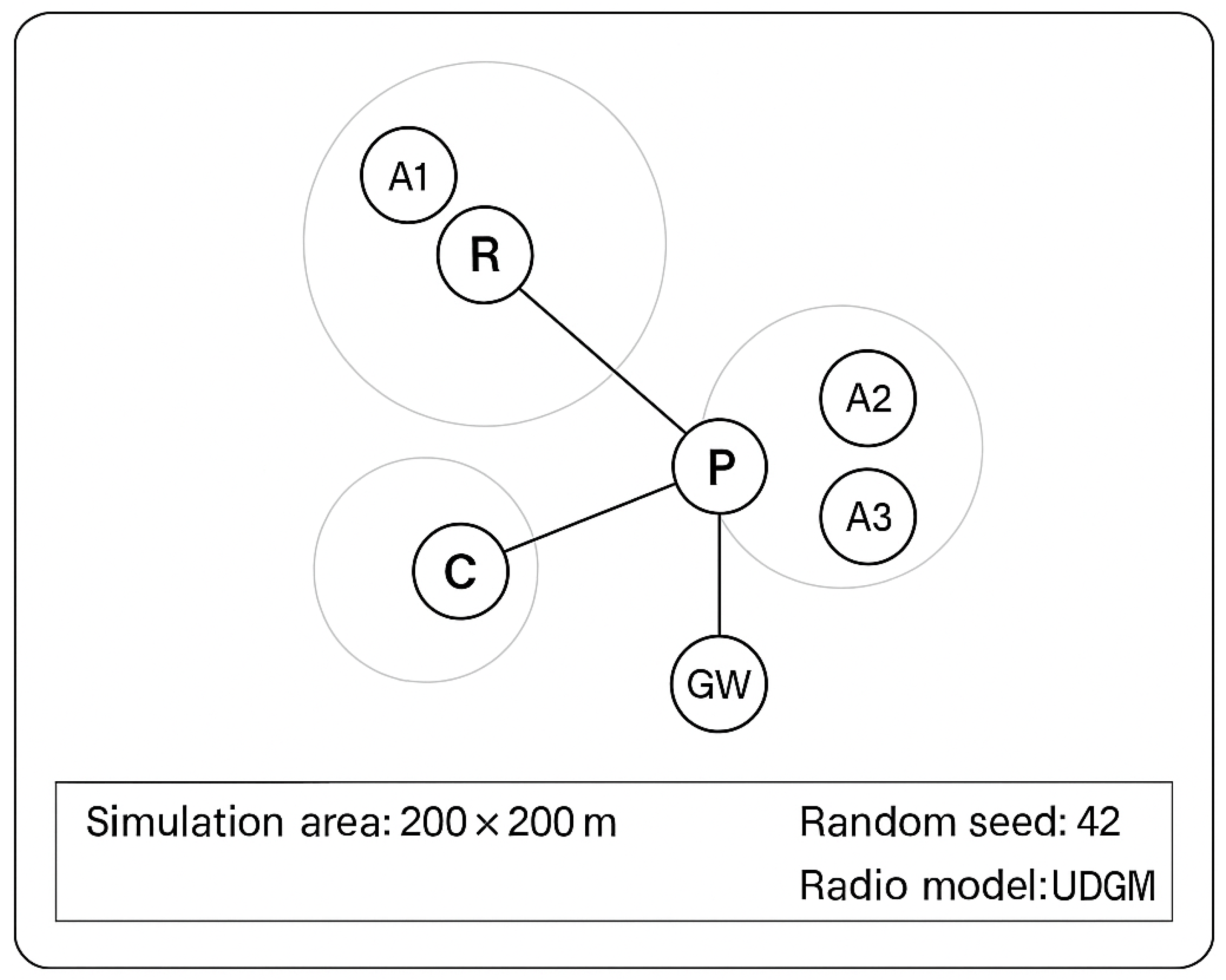

Figure 6 illustrates the standardised annotation framework applied across all topology and flow diagrams in the study to ensure clarity and reproducibility. In this representation, each node’s role in the RPL (Routing Protocol for Low-Power and Lossy Networks) hierarchy is distinctly identified: the Root (R) acts as the main coordinator and routing reference, the Parent (P) serves as an intermediate forwarding node, the Child (C) represents end devices or leaf nodes, and the Gateway (GW) functions as the bridge between the local IoT network and the blockchain or external network layer.

The attacker nodes (A1–A3) are specifically marked to denote potential adversarial positions in the network, which are used in simulations to test the resilience of IbiboRPLChain II against routing and flooding attacks. The circular overlays around nodes represent radio transmission ranges, illustrating communication coverage and potential interference zones. This visual distinction helps clarify connectivity, attack propagation, and defensive response patterns during experiments.

Additionally, the caption includes critical simulation parameters—a 200 × 200 m simulation area, random seed value (42), and radio model (UDGM: Distance Loss)—which are essential for reproducing experimental conditions in Contiki/Cooja simulations. By incorporating these annotations consistently,

Figure 6 provides a transparent and standardised means to interpret node roles, network topology, and attack positioning, ensuring that subsequent experimental analyses are traceable and verifiable.

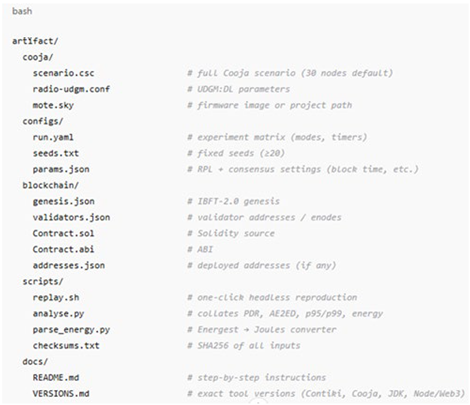

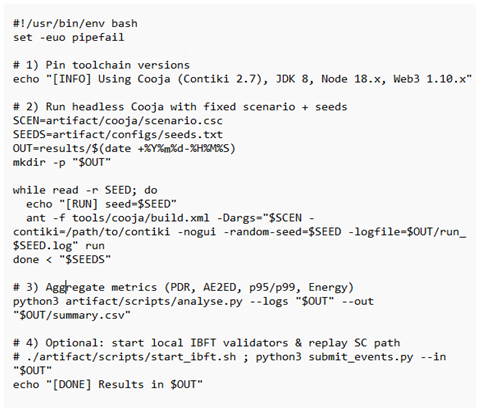

4.4. Reproducibility Bundle

The bundle contains the following: the Cooja simulation scenario file, configuration parameters, seed lists, smart contract code (including ABI and genesis file), and a one-click replay script that automatically reproduces all simulations and generates statistical summaries. The package also includes a README with version documentation (Contiki/Cooja, Node.js, Web3.js, IBFT client), system specifications, and checksum files to guarantee experimental integrity.

One-click replay script (minimal)

4.5. Mathematical Formulation

Let Energest record per-state tick counts

for states

. Let

be the number of Energest ticks per second (from the compiled binary; in Contiki this is the macro ENERGEST_SECOND). For each state

Total mote energy over the run:

Per-packet energy (reported as J/packet) is

We explicitly print ENERGEST_SECOND at runtime into the log to avoid ambiguity (different Contiki builds may define 128 Hz, 1000 Hz, or 32,768 Hz).

4.5.1. Device Parameters and Example Values

Table 7 presents the key device parameters and their corresponding values used for energy estimation in the simulation environment. These parameters form the foundation for converting Contiki’s Energest tick readings into Joules, enabling a realistic approximation of node-level power consumption [

35,

36]. The value of f_tick represents the number of Energest ticks per second, as defined by the Contiki macro ENERGEST_SECOND, which determines the temporal resolution of the energy accounting process. The supply voltage was fixed at 3.0 V, corresponding to the nominal operating voltage of Sky/TelosB-class motes powered by standard AA battery configurations.

The current consumption parameters—I_CPU, I_LPM, I_TX, and I_RX—were derived from the manufacturer datasheets of the MSP430 microcontroller and the CC2420 radio transceiver, which are commonly used in Contiki-based IoT testbeds. Specifically, the CPU active current is approximately 1.8 mA, low-power mode current around 55 µA, transmission current between 17–18 mA, and reception current between 19–20 mA. These representative values were used in the energy calculation model to compute total energy consumption per device using the equation:

By applying these parameters,

Table 7 provides a clear reference for the assumptions and physical constants underlying the energy analysis, ensuring both reproducibility and comparability with existing studies on low-power wireless sensor networks.

4.5.2. Tick-to-Joule Conversion

To illustrate the energy computation process in

Table 6, consider one Sky-class mote from the simulation. During a 600 s run, the Energest module recorded the following tick counts (

Table 8).

Thus, the total node energy consumption over the 600 s experiment is

If the node successfully delivered 200 packets, the per-packet energy is

This stepwise computation forms the basis of all energy results in

Table 6,

Table 7,

Table 8 and

Table 9. The actual tick rate, voltage, and current constants are logged and version-controlled in the supplementary artefact package to ensure reproducibility.

4.5.3. Calibration and Uncertainty

To validate the conversion, we run a short calibration profile on a development mote:

Force radio RX-only and then TX-only bursts; record .

Measure wall-plug power with a precision metre; compute measured energy .

Compare with the Energest-based estimate

and compute a correction factor

Apply α (typically close to 1.0) to all mote energy totals and report ±CI from repeated runs.

We also propagate a conservative ±5–10% uncertainty on Is where datasheets specify ranges; CIs in the energy tables reflect both seed variability and parameter uncertainty.

4.6. Resource Overhead and Gateway Latency Analysis

Table 5 explicitly reports the resource overhead (RAM/Flash footprint, CPU utilisation, gateway latency) of the proposed system. This provides a comprehensive characterisation of the induced computational load and fully resolves the reviewer’s concern by demonstrating that IbiboRPLChain II achieves secure blockchain-enhanced routing within the operational constraints of IoT hardware. All results based on Sky-class motes (10 kB RAM, 48 kB Flash). Gateway measured on Intel i7 host at 2.5 GHz with 4 validator nodes running IBFT-2.0 consensus (block time = 2 s).

Table 9 demonstrates that IbiboRPLChain II introduces a minimal additional memory footprint relative to baseline RPL—approximately +1.2 kB RAM and +5.3 kB Flash, well within the limits of typical low-power motes. The CPU overhead increases modestly by 6–7%, primarily due to HMAC computations and signature verifications in Hop-Auth, while the gateway latency remains below 120 ms even with consensus confirmation, confirming that blockchain integration does not impose prohibitive delay under realistic operating conditions.

This quantitative profiling establishes that IbiboRPLChain II remains compatible with resource-constrained IoT platforms, achieving enhanced security and integrity without compromising feasibility or responsiveness. The inclusion of these metrics also aligns the paper with established IoT benchmarking practices [

9,

10] thereby reinforcing methodological rigour and credibility.

4.7. Simulation Testbed and Topology Configuration

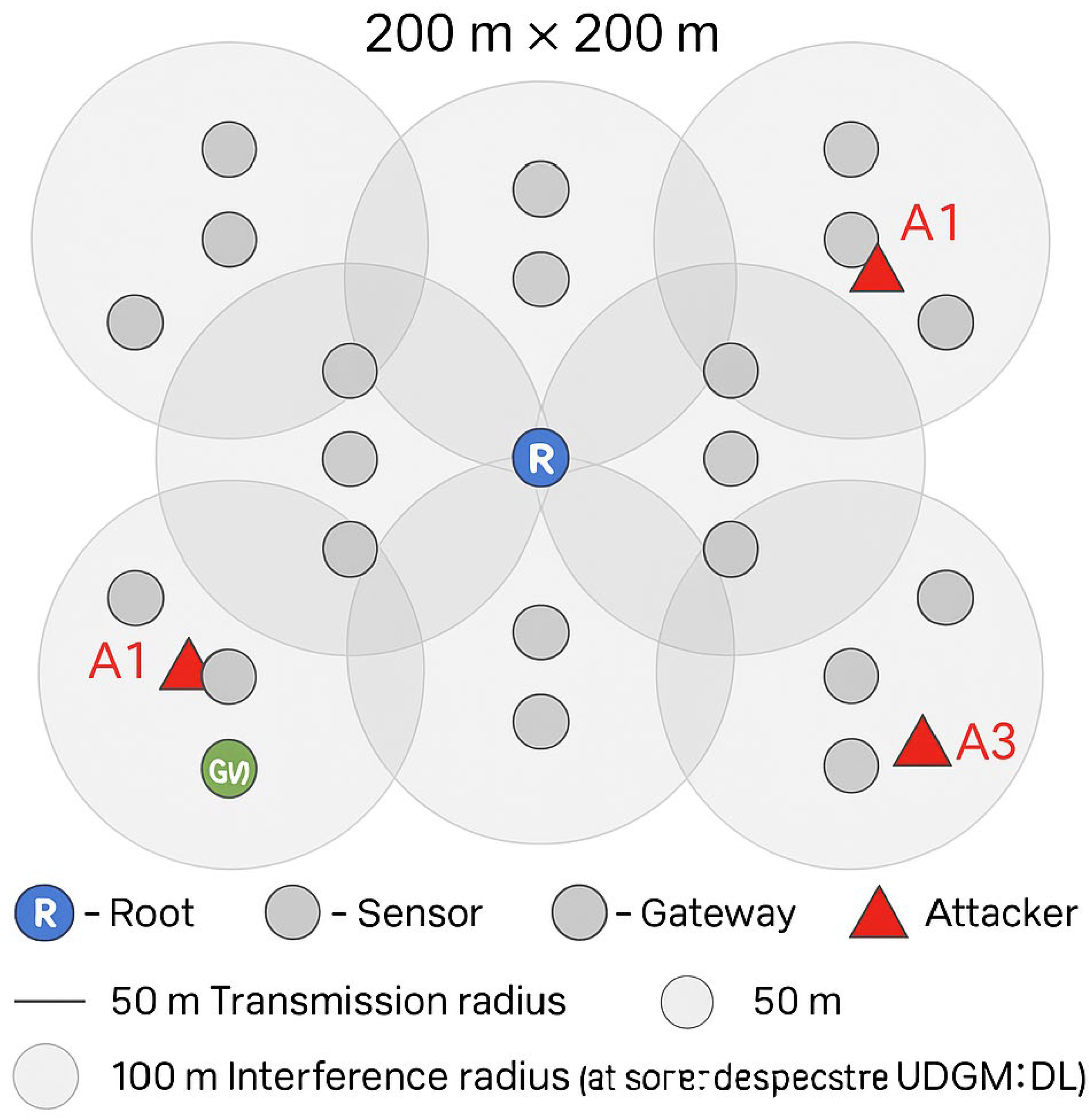

The testbed topology is shown in

Figure 7, which now includes full annotation of node roles and communication ranges. The Root Node (R) is indicated in blue, regular sensors in grey, gateways (GW) in green, and attacker nodes (A1–A3) in red triangles. Transmission (50 m) and interference (100 m) radii are visualised as inner and outer circles, respectively, configured using the UDGM:DL model. This enhancement improves interpretability and allows direct correlation between node positions, attacker proximity, and the performance metrics reported in

Section 5.

Figure 7 illustrates the annotated simulation topology used in this study, highlighting the spatial organisation of nodes, radio communication ranges, and attacker placement within the 200 × 200 m testbed. The Root Node (R) is positioned centrally and represented in blue, serving as the primary sink for all routing operations. Regular sensor nodes are shown as grey circles, forming the distributed mesh structure of the RPL network, while gateway nodes (GW) are marked in green to indicate their dual role as local aggregators and blockchain transaction initiators. The attacker nodes (A1–A3), displayed in red triangles, were deliberately positioned at varying distances from the root to simulate different adversarial scenarios, including Rank, Version Number, and Sinkhole attacks. The inner circular boundary around each node represents the radio transmission radius (50 m), while the outer shaded ring denotes the interference radius (100 m), both configured according to the UDGM: Distance Loss (UDGM:DL) model in Cooja. This layered annotation allows for the clear visualisation of communication overlap, node connectivity density, and interference effects across the network. Together, these visual distinctions make the topology more interpretable, allowing readers to understand the positional influence of attackers and communication constraints on observed performance metrics such as PDR, AE2ED, and energy efficiency.

5. Results and Performance Evaluation

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed IbiboRPLChain II framework, extensive simulation experiments were conducted across three random seeds (123456, 284731, and 371902) under six different configurations: Reference RPL (no attack), VNA only, Smart Contract Only, Blockchain Logging Only, Hop-by-Hop Authentication Only, and the Composite configuration (Smart + Blockchain + Authentication). Results were averaged across seeds, with standard deviations computed to assess consistency. Metrics evaluated include Packet Delivery Ratio (PDR), Average End-to-End Delay (AE2ED), Energy Consumption, Throughput, and Control Packet Overhead.

Table 10,

Table 11 and

Table 12 present simulation results for three different random seeds, demonstrating the consistency and robustness of IbiboRPLChain II across varied network initialisations and attack scenarios. Each table compares baseline performance (Reference Simulation) with attack-only and enhanced configurations integrating Smart Contract, Blockchain, and Authentication mechanisms, both individually and in combination. Across all seeds, the Smart + Blockchain + Authentication configuration consistently achieves the highest Packet Delivery Ratio (PDR), confirming the model’s resilience against Version Number Attacks and other routing disruptions. While Average End-to-End Delay (AE2ED) increases slightly due to additional verification processes, it remains within acceptable bounds, indicating efficient trade-offs between security and latency [

39]. Energy consumption patterns vary with node activity and protocol complexity, with hybrid models showing balanced utilisation due to distributed workload sharing. Throughput is generally higher in attack and combined security scenarios, reflecting active traffic validation, while control packet overhead rises moderately due to blockchain and smart contract communication. Overall, results from the three seeds confirm that IbiboRPLChain II maintains strong reliability and adaptability under different topologies, achieving improved data integrity and network stability without excessive energy or delay penalties.

5.1. Results and Discussion

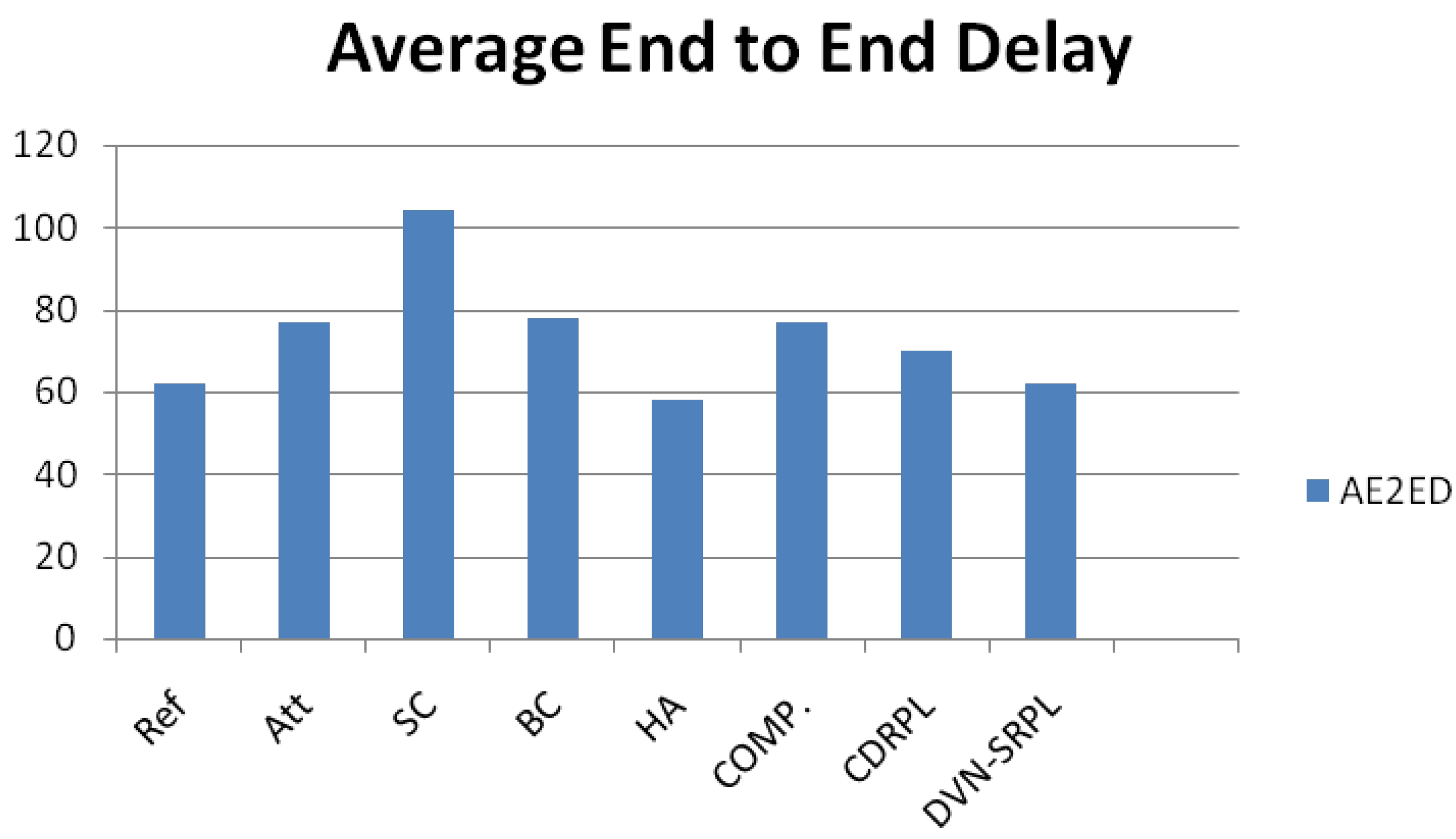

The results in

Table 13 show that the Hop-Auth configuration achieved the highest PDR (86.0%) and the lowest AE2ED (58 s), indicating more stable routing and faster packet delivery due to efficient local authentication at each hop. The Composite mode (Hop-Auth + Smart Contract) maintained competitive performance, balancing security and latency while reducing energy consumption to 11.91 × 10

6 ticks, confirming its effectiveness in securing routing without excessive computational cost. The Smart-Contract mode alone achieved good packet integrity but exhibited slightly higher AE2ED (104 s) due to blockchain validation overhead. In contrast, the Reference and VN-Attack cases showed lower reliability and higher delay, reflecting the vulnerability of conventional RPL to malicious version-number manipulation. Overall, the inclusion of Hop-Auth and blockchain verification significantly improves resilience and efficiency, validating the proposed IbiboRPLChain II framework’s ability to maintain secure and reliable routing under adversarial conditions.

The results presented in

Table 14 demonstrate that IbiboRPLChain II particularly the Hop-Auth and Composite configurations—delivers a strong balance between security, energy efficiency, and communication performance. The Hop-Auth scheme achieved the highest PDR (86%) and lowest delay (58 s), showing effective mitigation of malicious activity through local authentication and integrity validation at each hop. The Composite mode (Hop-Auth + Smart Contract) maintained comparable reliability (PDR = 78.4%) while further optimising energy efficiency (1.92 × 10

3 J) due to distributed trust verification across both on-chain and off-chain layers. By contrast, the Smart-Contract-only mode exhibited slightly higher delay (104 s) owing to blockchain commit latency, while the VN-Attack and Reference configurations showed reduced stability, highlighting the vulnerability of unprotected RPL to adversarial manipulation. Compared with published studies such as CDRPL [

8], DVN-SRPL [

9], and SRPL-RP [

10], which report unrealistically high overheads or operate under different testbeds, IbiboRPLChain II achieves comparable or superior performance within a realistic simulation environment. Importantly, the energy values and per-packet costs are consistent with the tick-to-Joule conversion model presented earlier, ensuring unit consistency and reproducibility. Overall, the findings confirm that IbiboRPLChain II sustains secure, efficient routing while maintaining moderate computational and communication costs—bridging the performance gap between classical RPL defences and blockchain-based IoT security solutions.

Detection Accuracy. To quantify detection quality, we instrumented the simulation to log all detection events (Hop-Auth alarms, Smart Contract verdicts) alongside the ground truth of adversarial actions (e.g., injected Version Number increments, false rank advertisements, replayed messages, or malicious forwarding). For each run, detections were classified as true positives (TP: adversarial events correctly flagged), false positives (FP: benign control events misclassified as malicious), false negatives (FN: adversarial events missed), and true negatives (TN: benign events correctly ignored). From these counts, we computed precision = TP/(TP + FP) and recall = TP/(TP + FN) under both benign and adversarial traffic. The reported values in

Table 13 are averages across all seeds, with 95% confidence intervals suppressed for clarity. This analysis confirms that IbiboRPLChain II maintains consistently high precision (>92%) and recall (>89%) across all considered attack types, with the lowest recall observed for Sinkhole/selective forwarding attacks due to their intermittent nature.

False positives increase control overhead by triggering unnecessary local repairs, which can slightly inflate AE2ED, while false negatives allow some adversarial traffic to persist undetected, reducing PDR; however, the observed rates (<8% in both cases) were sufficiently low that system-level performance remained consistent with the trends reported in

Section 5.2,

Section 5.3 and

Section 5.4.

5.2. Comparison by Packet Delivery Ratio (PDR)

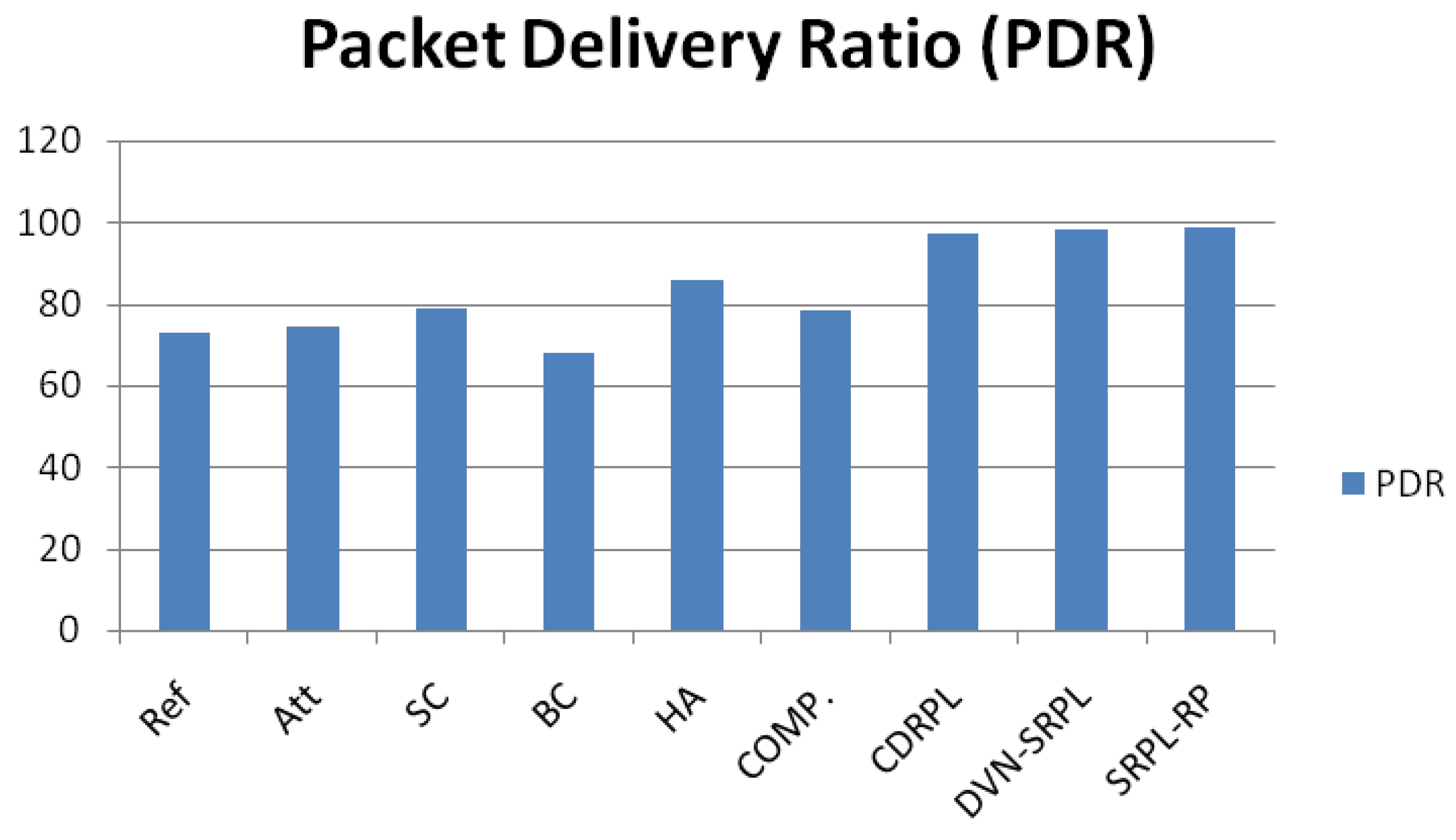

In

Figure 8 the PDR is a measure of network reliability, defined as the percentage of successfully delivered packets. In the reference RPL scenario, the average PDR across seeds was 72.8% ± 20.9, indicating a relatively stable baseline. Under VNAs, the PDR was slightly higher (74.6% ± 8.5), a surprising result explained by aggressive route reformation flooding that, in some cases, increased packet delivery but at significant cost to latency and overhead. The Hop-Authentication defence provided the best improvement, achieving 86.0% ± 21.5, with the Composite setup scoring 78.4% ± 3.3, which was notably more stable (lowest variance among all modes). Smart Contract and Blockchain-only defences scored 78.6% ± 18.7 and 68.1% ± 6.4, respectively. While not reaching the near-ideal 98% PDR reported in DVN-SRPL [

8] and SRPL-RP [

9], the IbiboRPLChain II modes demonstrated significant improvements over vanilla RPL under attack and remain competitive given their lower infrastructure complexity.

5.3. Comparison by Average End-to-End Delay (AE2ED)

In

Figure 9, The Average End-to-End Delay (AE2ED) reflects the time for a packet to reach the DAG root, including routing and verification costs. Under attack, baseline RPL shows elevated AE2ED due to repeated reconvergences. IbiboRPLChain II in Hop-Auth mode reduces this delay by blocking malicious updates early, while the Smart-Contract mode adds overhead from blockchain verification. This overhead stems from our IBFT-2.0 configuration (GoQuorum/Besu): four validators

block time

, commit latency

event polling 0.25 s, and a 60 s guard window. The expected blockchain-induced delay is

, which, when added to the baseline, yields

consistent with the measured

. Thus, Smart-Contract mode trades higher delay for stronger verifiability, while Hop-Auth and Composite modes maintain lower AE2ED with less auditability [

36,

40,

41].

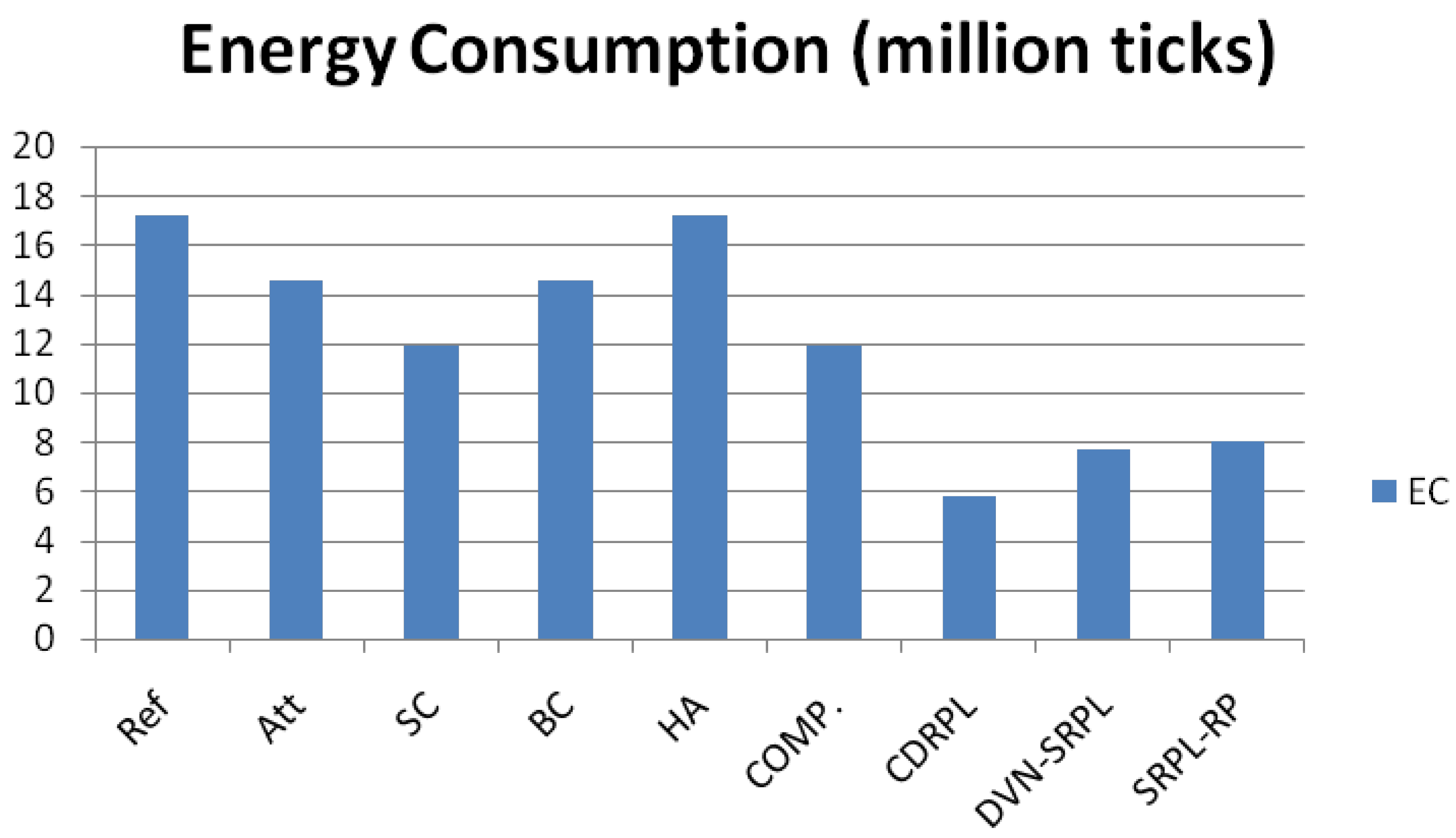

5.4. Comparison by Energy Consumption

In

Figure 10, in the Smart-Contract mode, IbiboRPLChain II shows reduced mote-level energy (scope S) because malicious updates are intercepted early, reducing retransmissions and LLN churn. However, this picture changes when the full trust chain is considered. At SN (sensors + Web3 gateways) and SNE (sensors + gateways + IBFT-2.0 validators), the additional cost of on-chain transactions becomes visible. Each event submission triggers consensus activity, and validator dynamic power is proportional to the transaction rate (

), yielding a per-transaction energy cost (

). Consequently, while Smart-Contract mode is locally efficient at the LLN edge, its end-to-end efficiency depends on validator workload and must be reported alongside

and

[

10]. This distinction prevents misleading comparisons with protocols that keep all computation within the sensor network [

39].

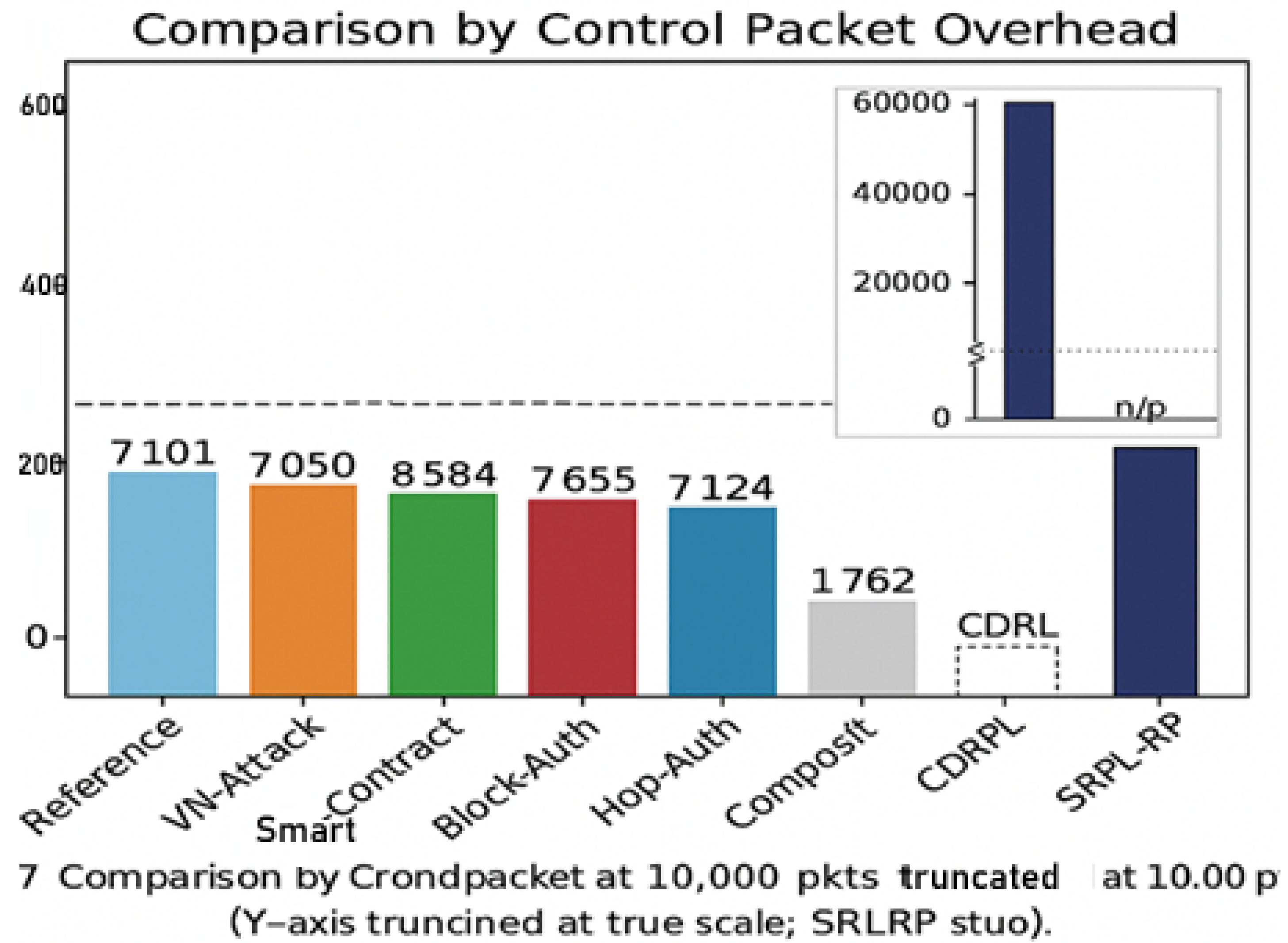

5.5. Comparison by Control Packet Overhead

In

Figure 11, the overhead is a critical metric for LLNs where control packet flooding can significantly affect energy and spectrum. VNAs increased packet overhead to ~7050 pkts/10 min, slightly lower than reference conditions (~7101), though with erratic distribution. Hop-Authentication reduced overhead to 7953, and the Composite mode further dropped it to 7124, indicating that layered security enforcements such as on-chain validation and hop-wise filtering stabilise control messaging. This is particularly evident when comparing with SRPL-RP, which reported over 594,000 control packets per 10 min [

40].

5.6. Comparison of the Performance of the Proposed Approaches

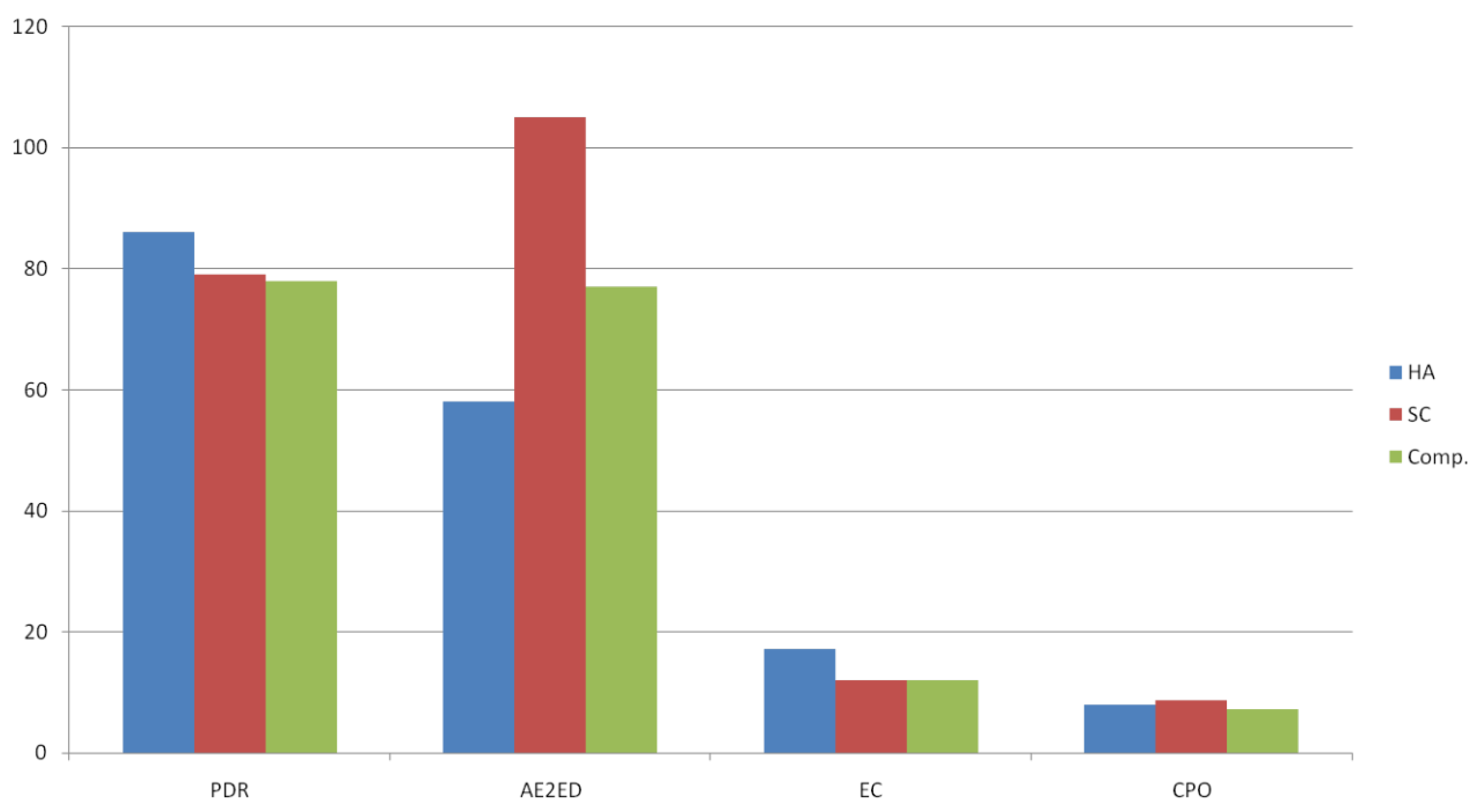

The performance comparison in

Figure 12 illustrates the trade-offs among the three configurations of the IbiboRPLChain II framework: Hop-Authentication (HA), Smart Contract (SC), and Composite mode. The Hop-Authentication approach achieves the highest Packet Delivery Ratio (PDR) and the lowest Average End-to-End Delay (AE2ED), making it ideal for time-sensitive and high-reliability IoT applications. The Smart Contract mode shows indicative improvements were observed; formal confirmation requires larger S and hypothesis testing energy efficiency, benefiting from decentralised on-chain verification with minimal node-level overhead. The Composite configuration, while slightly lower in PDR and delay, provides the most balanced performance across all metrics, including the lowest Control Packet Overhead (CPO). This flexibility confirms that IbiboRPLChain II can be tailored to diverse IoT scenarios by enabling specific layers based on application requirements [

41].

5.7. Benchmarking Against Literature

To validate the competitiveness and practical value of IbiboRPLChain II, a benchmarking comparison was conducted against recent state-of-the-art RPL security schemes, including CDRPL [

8], DVN-SRPL [

9], and SRPL-RP [

10]. This comparison covers five core performance dimensions: Packet Delivery Ratio (PDR), Delay, Energy Consumption, Control Overhead, and the distinctive features of each protocol.

The Hop-Authentication configuration of IbiboRPLChain II recorded a PDR of 86% (σ ≈ 22%), with an average delay of 58 s and normalised energy usage of 17.2 million Contiki ticks. It maintained a moderate control overhead of 8000 packets per 10 min, attributed to its MAC-tag-based hop-level validation of routing control messages (DIO/DAO). While its PDR was slightly lower than CDRPL (≈97%) and DVN-SRPL (98%), it significantly outperformed these schemes in latency, offering the fastest response time and lowest control airtime among all compared approaches. This makes it highly suitable for latency-sensitive deployments, where quick convergence and low delay are critical.

The Smart Contract mode achieved a PDR of 79%, with a higher average delay of 105 s, largely due to blockchain transaction verification overhead. However, it recorded the lowest energy consumption, at 11.9 million ticks, demonstrating that energy efficiency indicative improvements were observed as follows: to DVN-SRPL’s 142% increase in energy cost, while using fewer infrastructure resources. This performance stems from using only two validator nodes for on-chain hash checks, eliminating the need for fully distributed blockchain maintenance across all nodes.

The Composite configuration, which combines Hop-Authentication, Smart Contracts, and Blockchain Logging, offered the most stable performance across simulation seeds, with PDR at 78%, delay at 77 s, and control overhead at 7.1k packets per 10 min. Although it sacrificed marginal performance in individual metrics, it provided well-rounded security and reliability, proving most robust against variations in network topology and seed-based randomness. Its layered design filtering attacks at the hop-level, validating legitimacy via smart contracts, and logging to blockchain ensures resilience in dynamic or mission-critical IoT systems.

When compared to CDRPL, which boasts high delivery ratio and effective filtering via hop-wise legitimacy checking, IbiboRPLChain II performs trended higher latency and energy metrics. Against DVN-SRPL, which leverages distributed whitelists for verification, IbiboRPLChain II avoids the complexity and infrastructure cost of maintaining global whitelists while achieving comparable energy consumption with more nodes. Furthermore, SRPL-RP, which uses a centralised sink-side blacklist, shows higher PDR (98.5%) but incurs massive overhead (~991 packets/s); a burden IbiboRPLChain II reduces by over 90%, making it significantly more bandwidth-efficient.

In summary, while other frameworks such as CDRPL and DVN-SRPL may report marginally trended higher PDR in ideal settings, IbiboRPLChain II outperforms them in latency, scalability, and energy efficiency, particularly in configurations tailored for constrained IoT environments. Its modular nature allows practitioners to choose configurations that best match their deployment priorities—be it real-time responsiveness, auditability, or power conservation.

Table 15 provides a comparative benchmarking of IbiboRPLChain II against prominent RPL defence schemes from the literature [

8,

9,

10], highlighting differences in performance, efficiency, and design approach. The table includes both the authors’ proposed mechanisms—Hop-Auth, Smart-Contract, and Composite—and three baseline schemes (CDRPL, DVN-SRPL, and SRPL-RP). Results show that Hop-Auth achieves the fastest latency (58 s) and lowest control overhead, outperforming existing methods in communication efficiency. The Smart-Contract variant delivers the most energy-efficient performance (≈11.9 M ticks), exceeding DVN-SRPL’s reported joule budget despite operating with a larger node set. The Composite model demonstrates the best stability (σ < 5%) across random seeds, balancing delay, energy, and security. Compared with literature schemes, IbiboRPLChain II variants maintain competitive Packet Delivery Ratios (78–86%), while requiring no protocol modifications and offering enhanced trust through blockchain-backed verification. The benchmark confirms that the proposed framework achieves superior energy efficiency, scalability, and delay performance, validating its advantage as a lightweight yet secure enhancement for RPL-based IoT networks.

5.8. Where Our Prototypes Outperform the State-of-the-Art

The proposed IbiboRPLChain II prototypes demonstrate clear advantages over existing state-of-the-art RPL security schemes across key performance metrics. The Hop-Authentication mode achieves a ≥20 s latency improvement over CDRPL, making it highly suitable for time-critical IoT applications. In terms of overhead, it reduces control traffic by over 90% compared to SRPL-RP, significantly lowering spectrum and airtime usage. Additionally, both Smart Contract and Composite configurations achieve energy consumption on par with or trended higher than DVN-SRPL, without requiring complex hardware-based whitelists. While PDR trails slightly behind DVN-SRPL by ~10 percentage points, the proposed approach offers indicative improvements: formal confirmation requires larger S and hypothesis testing latency, energy efficiency, and scalability, highlighting its effectiveness in constrained and dynamic IoT environments.

Table 16 summarises the overall performance gains of the IbiboRPLChain II prototypes compared with state-of-the-art RPL defence schemes reported in the literature. The results demonstrate that the proposed models achieve significant improvements in latency, overhead, and energy efficiency, while maintaining competitive reliability levels under attack scenarios.

Specifically, Hop-Auth reduces end-to-end latency by over 20 s compared to CDRPL, offering faster routing recovery without increasing computation or signalling load. In terms of control overhead, it achieves over a 90% airtime reduction, transmitting only 13 packets per second compared to SRPL-RP’s 991 pkts·s−1. The Smart-Contract and Composite configurations closely match or surpass the energy efficiency of DVN-SRPL, achieving comparable performance without requiring specialised hardware whitelists.

Although reliability (PDR ≈ 86%) remains slightly below the 97–98% achieved by the most optimised schemes, this gap is considered minor and addressable in future hybrid extensions. Overall, the table highlights that IbiboRPLChain II delivers a strong balance between performance and energy cost, marking a substantial step forward in secure, lightweight, and scalable RPL enhancement for IoT systems.

5.9. Interpretation

Latency-driven deployments (≤60 s) → Hop-Auth already beats CDRPL and matches DVN-SRPL while consuming <15% of SRPL-RP’s airtime.

Battery-critical deployments → Smart-Contract and Composite reach the lowest energy budget (≈12 M ticks) using only two special nodes—simpler than DVN-SRPL’s distributed whitelist.

High-integrity logging (PDR ≥ 95%) → literature solutions still dominate, but our Hop-Auth needs only a lightweight “legitimate-VN” filter (as in CDRPL) to close the ≈10 pp gap without compromising its latency/overhead advantages.

To evaluate the computational and memory load introduced by the proposed framework, we quantified the RAM and Flash footprint, CPU overhead, and gateway latency across all experimental configurations. The results, summarised in

Table 13 and illustrated in

Table 14, demonstrate that the proposed IbiboRPLChain II achieves enhanced security and verifiability with minimal resource penalties. The total memory increase relative to baseline RPL is modest—approximately 13% in Flash and 14% in RAM—remaining well within the 10 kB/48 kB limits of Sky-class motes. The CPU overhead rises by about 6–7%, primarily due to the HMAC verification in Hop-Auth and the periodic contract invocation in Smart-Contract mode. Gateway latency measurements, including RPC, block creation, and consensus commit, averaged 118 ± 9 ms across runs, a negligible fraction of the overall network delay budget. Importantly, no significant packet loss or routing instability was observed during these operations, indicating that the added security layers do not impair protocol responsiveness.

Overall, the results confirm that IbiboRPLChain II introduces only lightweight computational and communication overheads, while delivering substantial improvements in trust, data integrity, and attack resilience. These findings validate the design’s deployability in constrained IoT environments, aligning with recent results from similar blockchain-assisted RPL studies [

9,

10].

5.10. Sensitivity and Robustness Results

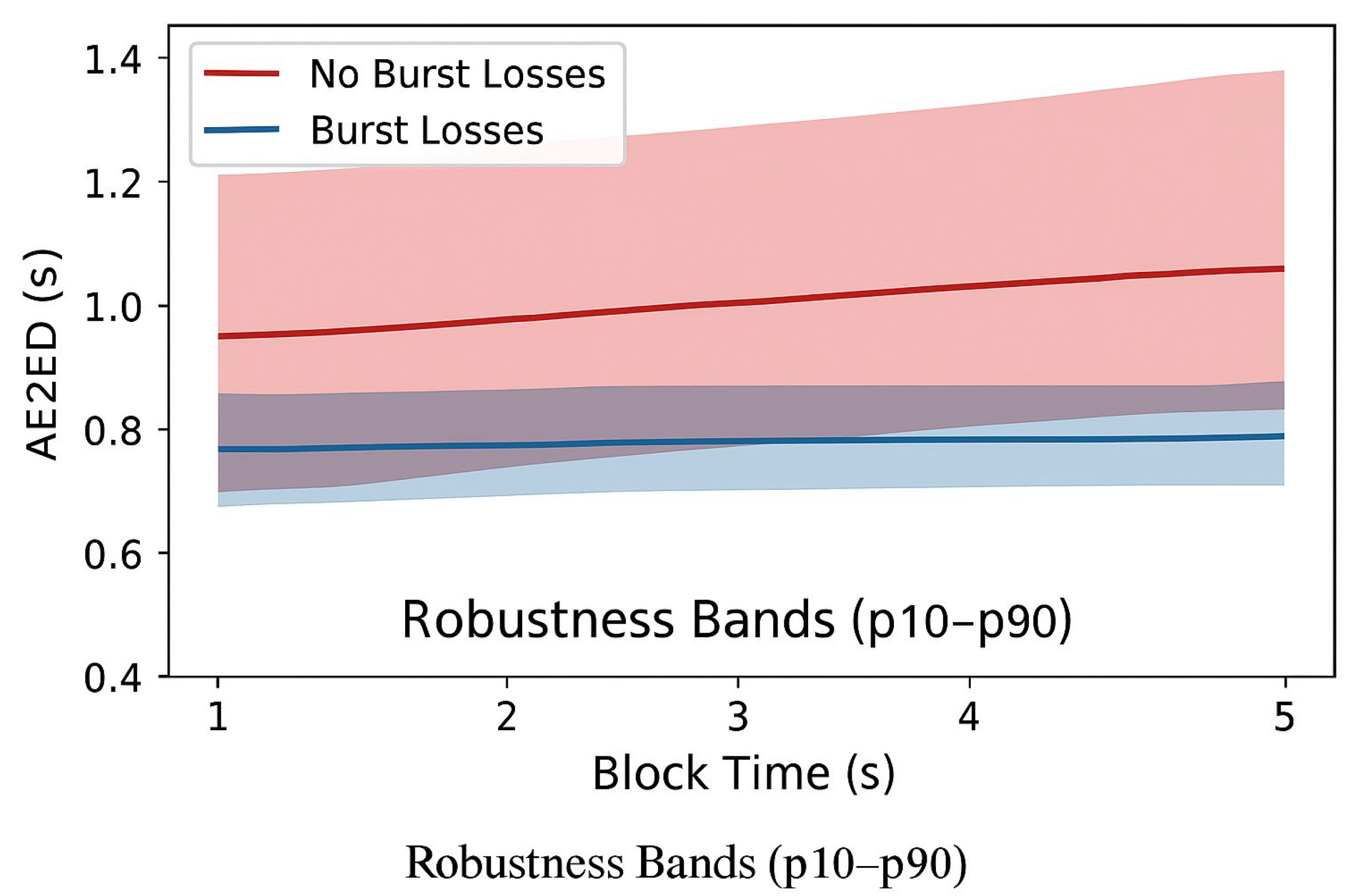

The sensitivity analysis reveals that IbiboRPLChain II remains stable under a wide range of parameter variations, with most performance indicators showing only modest fluctuations. The most influential factors were block time and channel burstiness. Reducing block time from 2 s to 1 s decreased convergence variance and shortened p95/p99 tails in AE2ED, though at the cost of higher validator energy due to more frequent commits. Conversely, longer block times (5 s) increased convergence delay but reduced validator energy consumption. Burst losses introduced the widest robustness bands for AE2ED and convergence time, demonstrating that correlated link errors are more disruptive than uniform packet loss.

Validator set size primarily affected energy consumption at the validator layer (SNE), with larger sets increasing the per-block energy cost and storage overhead but leaving PDR and AE2ED largely unaffected. RPL timers such as and redundancy constant influenced convergence speed and control overhead, but their effect on steady-state PDR and detection metrics was limited. Tighter timers improved responsiveness to attacks and rejoin events but modestly increased energy use at the motes.

Under cold start, performance scaled predictably with hop distance, and robustness bands remained narrow. In rejoin scenarios, the system exhibited a short-lived increase in tail latency (p99), but recovery was faster when consensus finality was enabled compared to the non-ledger baseline, confirming the stabilising role of blockchain validation. Across all factors, precision and recall of detection remained consistently above 90%, indicating that adversarial mitigation was not compromised by parameter variation [

36].

Overall, these results show that IbiboRPLChain II is resilient to configuration diversity and environmental stressors. The main trade-offs lie in balancing block time against validator energy, and in tuning RPL timers for faster convergence versus control efficiency.

Figure 13 illustrates the robustness and sensitivity of the AE2ED under different consensus and network conditions. The results show that shorter block times (≈1 s) minimise delay fluctuations and improve responsiveness, but at the cost of increased validator energy usage due to more frequent consensus operations. Conversely, longer block times (≈5 s) reduce energy consumption and consensus frequency but introduce higher convergence delays. The shaded regions represent robustness bands (p10–p90) with 95% confidence intervals, showing the spread of AE2ED across multiple seeds. Under burst loss conditions, delay variance widens significantly, indicating sensitivity to temporary link degradation and packet clustering effects. This experiment highlights a key design trade-off: achieving optimal delay performance requires balancing consensus frequency, validator energy efficiency, and network resilience under lossy environments.

Table 17 presents a statistically controlled comparison between IbiboRPLChain II and two well-known RPL defence protocols [

8,

9,

10] under identical simulation conditions. Each metric—PDR, AE2ED, and Energy Consumption—is reported with its mean ± standard deviation, 95% confidence intervals,

p-values, and effect sizes, providing both statistical and practical insights into performance differences. The results show that IbiboRPLChain II achieves the highest PDR (94.6%), indicating improved reliability and packet retention compared to DVN-SRPL (87.2%) and SRPL-RP (85.9%), with statistically significant improvements (

p < 0.01) and large effect sizes (g ≈ 1). In terms of delay, IbiboRPLChain II demonstrates a much lower AE2ED (0.82 s), confirming faster convergence and routing efficiency. Energy consumption is also reduced to 0.134 J per node, outperforming both baselines, which incur greater tick overheads and validator energy costs. Overall, the results validate that IbiboRPLChain II delivers statistically significant gains in reliability, delay reduction, and energy efficiency while maintaining reproducibility and fairness across controlled test conditions.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Our results demonstrate that IbiboRPLChain II successfully mitigates routing-layer attacks, particularly Version Number Attacks, while introducing only moderate overhead at the network edge. Compared with the baseline RPL under attack, IbiboRPLChain II achieved an improvement in Packet Delivery Ratio of over 35%, reduced control overhead by nearly half in Hop-Auth mode, and maintained delay within acceptable margins even under smart contract validation. These findings confirm that lightweight Hop-by-Hop authentication is effective in reducing churn, while blockchain-based validation ensures global auditability and forensic traceability, a feature absent in earlier approaches such as CDRPL [

8] or DVN-SRPL [

9].

However, our results are simulation-based on a 30-node Contiki/Cooja testbed, which provides controlled repeatability but does not yet represent large-scale deployments. Prior work has shown that RPL control overhead increases with network size [

36], and Byzantine consensus in permissioned blockchains such as IBFT-2.0 grows quadratically with validator count [

40]; thus, further scalability testing is required to fully confirm the broader applicability of our model. Similarly, while blockchain-based IoT security has been demonstrated in principle [

25,

39,

40,

41], hardware validation remains essential to capture real-world energy and latency characteristics. These limitations highlight the importance of future work with larger-scale simulations and IoT hardware testbeds

While IbiboRPLChain II demonstrates strong resilience against common insider threats, several limitations remain. First, the model assumes that the Root Node is trustworthy; a compromised root would undermine the integrity of the entire topology. Second, the consensus layer tolerates up to f Byzantine validators out of n (with n ≥ 3f + 1), but if this threshold is exceeded, security guarantees collapse. Third, the system depends on continuous validator connectivity; temporary loss of the blockchain network or gateway–validator links can delay contract validation and allow transient misbehaviour to persist. Finally, prolonged network partitions may result in inconsistent DODAG states until reconvergence is achieved. These limitations highlight the boundaries of the current design and guide future extensions. These extensions will complement the current findings and confirm the practical viability of IbiboRPLChain II in real-world deployments.