1. Introduction

The transition to a sustainable, resilient and decarbonised energy system has become a strategic priority for the European Union (EU). In this context, the European Climate Law enshrines the goal of achieving climate neutrality by 2050, relying on the development of clean technologies and the progressive decarbonisation of all economic sectors [

1]. One of the key elements of this transformation is green hydrogen, identified as the EU’s preferred energy vector for progressively replacing fossil fuels [

2,

3].

Hydrogen produced by electrolysis of water using renewable electricity represents a technically viable and environmentally sustainable alternative [

4,

5]. In addition to being a high-energy-density energy carrier, it does not generate greenhouse gas emissions during use [

6], and its versatility allows it to be integrated into diverse sectors such as transport, industry and construction [

7].

In the electricity sector, hydrogen is a strategic energy storage solution, as it allows energy from renewable sources to be harnessed in chemical form. This type of storage helps to provide flexibility to the electricity grid and improve the balance of the system [

8], facilitating the massive integration of non-manageable energies such as wind and solar.

In addition, hydrogen generated by electrolysis offers great operational flexibility and freedom from geographical or network constraints, which can alleviate pressure on transmission infrastructure and reinforce the stability of the electricity system [

9].

This storage capacity is particularly relevant in view of the challenges posed by the intermittent and non-dispatchable nature of wind and solar energy, whose production is highly dependent on weather conditions [

10,

11]. In this regard, combining it with hydroelectric power, which offers great regulation capacity and rapid response, improves the efficiency and stability of the electricity system by integrating renewable sources together [

12]. In fact, it has been pointed out that hydrogen production from renewable sources helps to reduce the energy surplus rate and optimises the effective use of available renewable resources [

13].

In Spain, 2024 marked a milestone in terms of the implementation of clean energy: 60% of installed capacity and more than 50% of electricity generation came from renewable sources, consolidating the government’s commitment to the objectives of the European Green Deal [

14]. At the same time, since 2020, the country has had an ambitious Hydrogen Roadmap [

15], which sets targets of up to 11 GW of installed electrolysis capacity and envisages an initial public investment of €1.5 billion, partly financed through the European Recovery and Resilience Facility [

16]. These measures reflect the strategic recognition of hydrogen as a key lever for green reindustrialisation and reducing external energy dependence.

However, despite the steady growth in installed renewable capacity, a significant part of its potential remains underutilised due to multiple factors: grid congestion [

17], lack of storage [

18], regulatory constraints [

19] and mismatches between supply and demand [

20]. In this context, various studies have pointed out that the use of surplus electricity for the production of green hydrogen not only reduces greenhouse gas emissions but also lowers the operating costs of electrolysis, given that up to 85% of the total cost of hydrogen is directly related to the price of electricity [

21,

22]. This approach therefore represents a doubly efficient strategy: both energetically and economically.

Within this framework, this paper aims to estimate the potential for green hydrogen production from untapped renewable energy sources in Spain in 2024. To this end, we analysed the theoretical electricity generation potential of the main renewable technologies (solar photovoltaic, wind and hydro), calculated on the basis of installed capacity and average capacity factors in Spain. Next, the difference between the energy that could have been generated and that actually produced has been determined, and this surplus has been quantified in terms of tonnes of green hydrogen produced by electrolysis, assuming optimal system operating conditions. The analysis also considers the technical limitations of the process, including the minimum operation of the electrolysers and the most efficient operating time windows.

This research aims to quantify a currently untapped energy opportunity, assessing its potential for conversion into a clean, versatile, and strategic energy vector. By providing insights into the amount of surplus energy that could be used for hydrogen production, the study aims to generate knowledge that may serve as a basis for further research, exploration of infrastructure needs, and broader discussions on renewable integration and the energy transition in Spain. Ultimately, the study highlights the role of green hydrogen as a solution to close the loop between renewable production, storage and sectoral decarbonisation.

2. Materials and Methods

The aim of this study is to quantify, from a theoretical perspective, the maximum untapped renewable electricity generation potential in Spain in 2024 and to estimate the amount of green hydrogen that could have been produced from this surplus through electrolysis. The analysis focuses on three key technologies: solar photovoltaic, wind and hydroelectric, and is carried out on a regional scale, taking into account the geographical diversity of renewable resources in Spain.

It is important to note that the results obtained represent a theoretical upper limit, conditioned by the availability and quality of public data. In practice, this potential is affected by numerous dynamic factors, such as climate variability [

23], technical limitations of the electricity system [

24], economic constraints [

25] and regulatory restrictions [

19]. Therefore, the methodological approach adopted is deliberately conservative in terms of operational assumptions, but seeks to reveal the realistic maximum ceiling using publicly available tools and verified historical data.

2.1. Data Sources and Tools Used

The analysis was based on data from multiple reliable sources:

The Global Solar Atlas was used to obtain the specific energy yield of photovoltaic systems (expressed in kWh/kWp/day) [

26].

The Global Wind Atlas provided information on wind conditions to validate regional wind potential [

27].

Historical data on installed capacity and actual electricity production by autonomous community for the period 2015–2024 were extracted from the Red Eléctrica de España (REE) databases [

28].

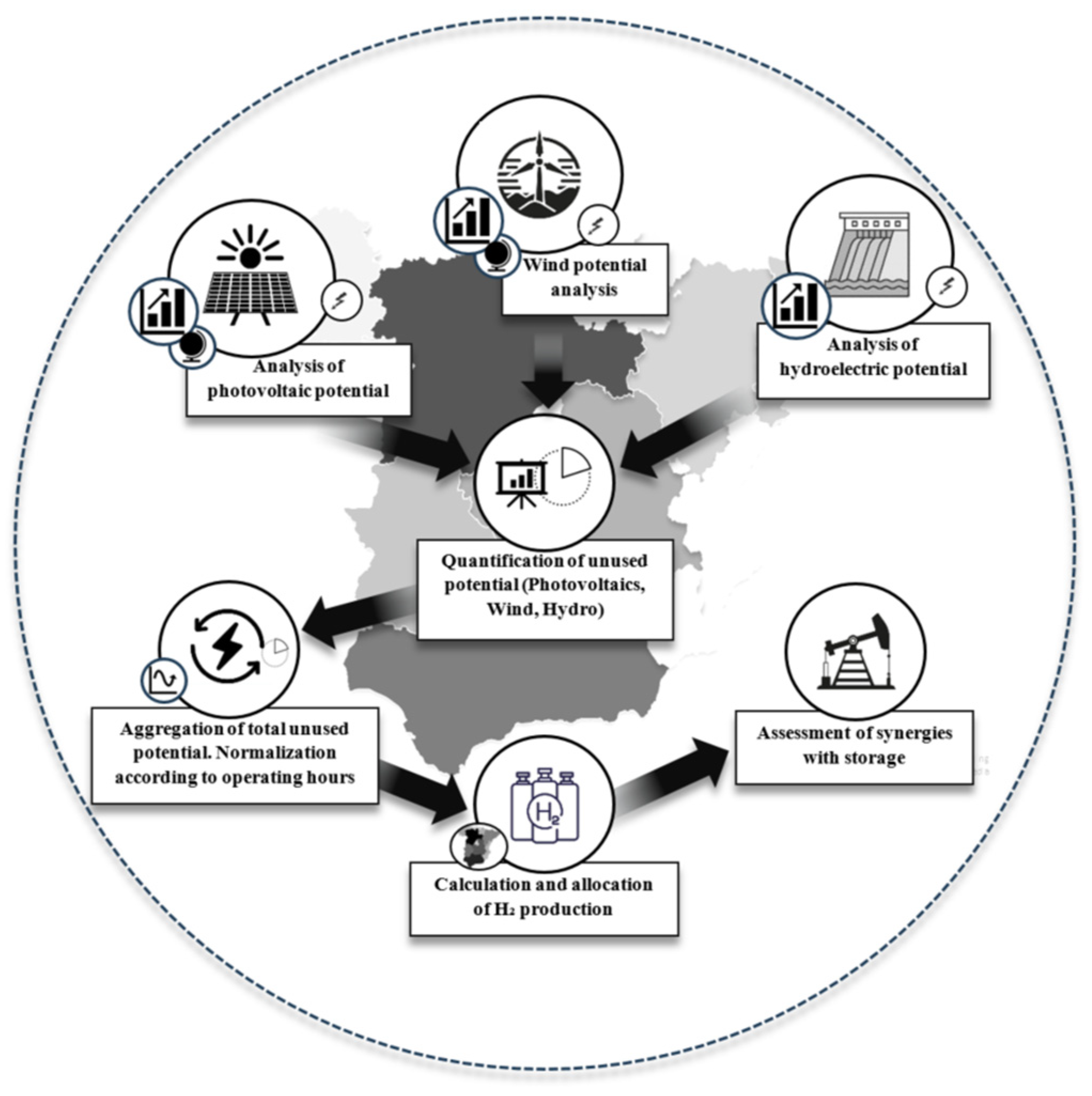

Figure 1 shows the general flow of the methodological process, from the estimation of untapped renewable potential to the conversion into theoretical green hydrogen and its regional distribution.

2.2. Calculation of Theoretical Electricity Generation Potential

The first step was to estimate the maximum theoretically possible annual electricity production (E

max) for each renewable energy source and each region. In the case of photovoltaic energy, the following formula was applied:

where P

inst is the installed capacity in the region [kWp] and Y

specific is the specific daily energy yield [kWh/kWp/day] in 2024. This value allows the annual production to be estimated assuming that each kilowatt peak operates under optimal conditions throughout the year.

For wind and hydro technologies, an approach based on the historical capacity factor (CF) was used, which expresses the ratio between the actual energy produced and the theoretical maximum if the plant operated continuously at full capacity. For each region and each type of resource, the annual capacity factor was first calculated for the entire ten-year period considered (2015–2024) according to the formula [

29]:

where E

real is the real annual generation [kWh], P

inst is the installed capacity [kW], and 8760 is the total number of hours in a year. From these ten values, the highest capacity factor achieved (CF

max) was selected for further calculations. This step is crucial because using the maximum historical value allows us to consider the most favourable climatic conditions experienced in the region and, therefore, to approach the absolute theoretical maximum. In the case of wind energy, this value was further corrected and validated using data from the Global Wind Atlas to avoid biases derived from anomalous conditions and ensure physical consistency with the site’s resource. For hydroelectric energy, due to the lower availability of specific hydrological data, the CF

max value was used directly as the best available approximation to the theoretical maximum. The theoretical maximum production for these two technologies was estimated using:

2.3. Estimation of Energy Surplus

Based on the E

max values, the unused energy potential (E

unutilized) was calculated as the difference between the theoretical maximum production and the actual generation in 2024:

To facilitate comparison between regions with different installed capacities, the untapped potential was also expressed as a percentage of theoretical maximum production.

2.4. Conversion to Green Hydrogen

The aggregate value of the untapped potential of the three renewable sources (Eunutilized) served as the basis for calculating the theoretical production of green hydrogen by electrolysis.

To avoid the use of a single constant conversion value, three technological scenarios were defined, corresponding to the main electrolysis technologies currently available. Alkaline Electrolysis (AEL) and Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) represent the most mature and commercially deployed options, while Anion Exchange Membrane (AEM) is still at a development stage but shows great potential for combining the efficiency of alkaline systems with the operational flexibility of PEM technology.

The baseline stack consumption values for each electrolysis technology were derived from [

30], which reported 51 MWh/t H

2 for AEL, 58.3 MWh/t H

2 for PEM, and 53.3 MWh/t H

2 for AEM under nominal operating conditions.

In addition to the stack power demand, the total system consumption also includes auxiliary processes such as power conversion (transformers and rectifiers), cooling and water circulation, lye recirculation, gas purification and drying, deoxidation and nitrogen purging, and control and safety systems. These auxiliary components typically account for 10–15% of the total electrical consumption of a hydrogen production plant, as reported for commercial-scale installations [

31].

This range already encompasses the average energy required for gas compression under normal operating conditions, which varies depending on the target storage pressure. As illustrated in [

32], compression from approximately 200 bar up to 450 bar entails an energy consumption between 4.4 and 9.3 MWh/t H

2, corresponding to high-pressure storage and refuelling applications. The figures adopted in this study are consistent with systems delivering hydrogen at intermediate pressures (30–60 bar) for on-site or direct industrial use, or at 70–200 bar for superficial and underground storage facilities, such as salt caverns and depleted gas fields [

33,

34,

35]. Therefore, the total specific consumption values used here already represent complete system operation, including both auxiliary services and typical medium-pressure compression.

Accordingly, the overall specific electricity consumption of the electrolysis system was calculated by applying the average auxiliary share to the baseline stack consumption values, resulting in total specific energy requirements of 57.40, 65.55, and 59.95 MWh/t H2 for AEL, PEM and AEM, respectively. These values correspond to complete on-site production systems, including auxiliary and compression demands representative of medium-pressure hydrogen delivery.

The total theoretical hydrogen mass (m

H2 theoretical) was then calculated for each technology according to Equation (5):

This formulation allows direct comparison of hydrogen yields among technologies while incorporating realistic operating requirements. The resulting hydrogen potentials obtained from the three scenarios were used to establish a range of national production capacity and to quantify regional variations, as presented in

Section 3.6.

This approach replaces the use of a single average conversion factor with a more differentiated and technically robust estimation, integrating technological performance variability and auxiliary system demands within the overall energy balance.

2.5. Time Adjustment and Realistic Estimation

Given that the continuous operation of electrolysers for 24 h is not economically viable [

36], the model was adjusted to include only the optimal time slots for renewable production, particularly between 9:00 and 19:00, when solar photovoltaic generation is highest. This specific time window serves as an economic proxy, representing the period with the highest concentration of photovoltaic surpluses and thus the lowest energy costs, which is critical for achieving a high utilisation factor and reducing the levelised cost of hydrogen. Based on the daily regional generation profiles of REE, production was normalised with respect to maximum potential and the fraction of the energy surplus concentrated in that interval was identified.

This fraction allowed for a more realistic estimate of hydrogen production, in line with the operating conditions expected in practice. Finally, the amount of hydrogen obtained was distributed regionally according to each community’s share of the total unused energy surplus. This criterion responds to the logic of locating electrolysers where renewable potential is highest and where existing infrastructure, such as underground storage in depleted gas fields, can be exploited.

The results were represented graphically using regional cartograms and bar charts that facilitate the interpretation of the relative and absolute potential in each region.

3. Results

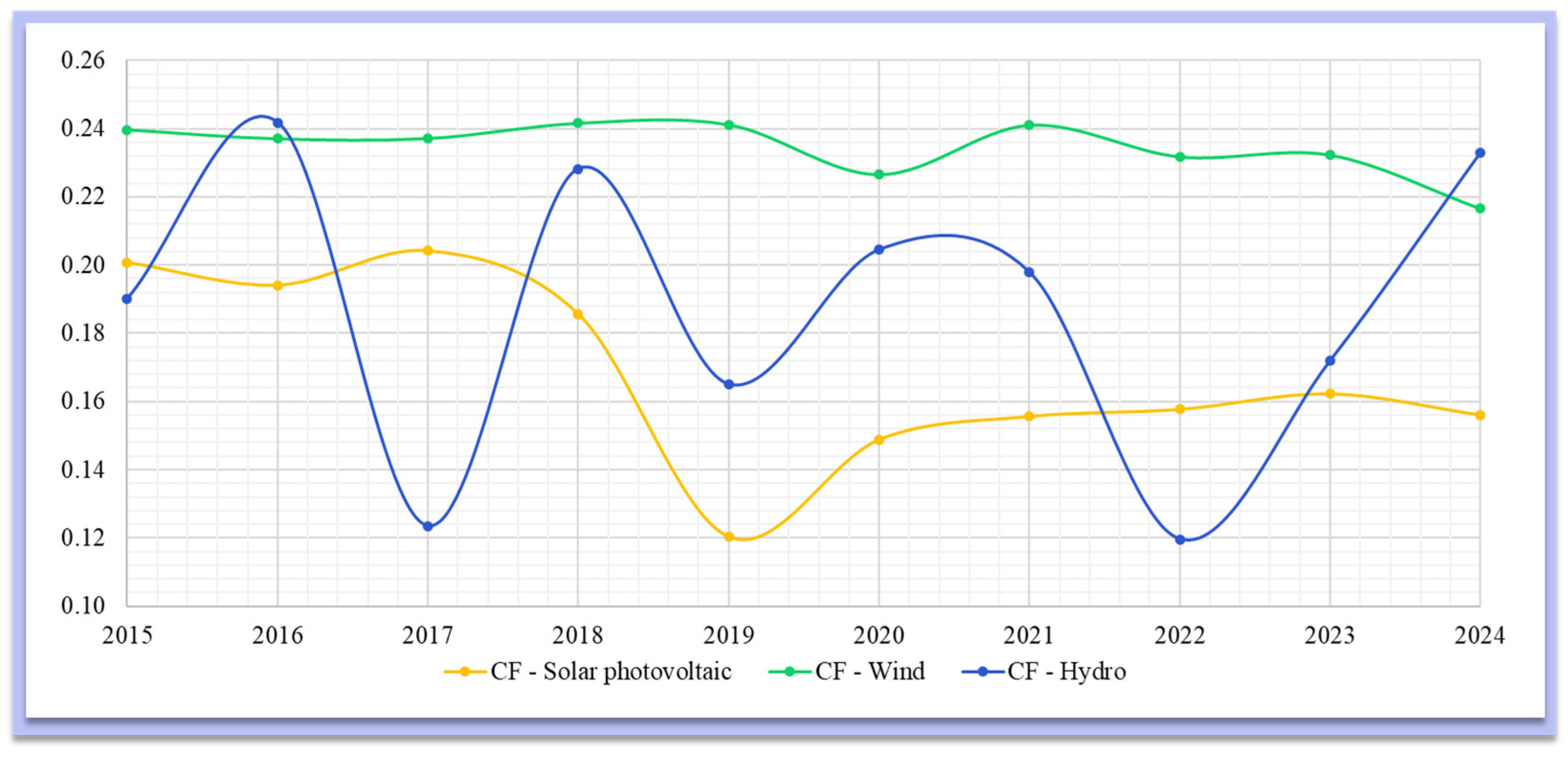

Analysis of the temporal evolution of the average annual capacity factors (CF) of photovoltaic, wind and hydroelectric energy in Spain during the decade 2015–2024 allows us to identify relevant patterns regarding the operational efficiency and interannual stability of each technology (

Figure 2). In general terms, wind energy shows remarkable stability, with values ranging between 0.22 and 0.24, reflecting high predictability at the national level. In contrast, hydroelectric energy shows the greatest variability, with CF values between 0.12 and 0.24, closely linked to fluctuations in the hydrological cycle. This variability is also accentuated by the strategic use of hydroelectric power as a backup technology in the Spanish electricity system, as it allows energy to be injected into the grid quickly and intermittently at specific times of imbalance between supply and demand, rather than operating continuously like other renewable sources.

However, the true operational potential must be analysed at the regional level. The data reveal significant geographical disparities, especially in the case of hydroelectric power, where regions such as Galicia and La Rioja achieve CFs above 0.31, while other areas have much lower values. For this reason, the analysis focuses on the regional level, using specific data from the Global Solar Atlas (for photovoltaics) and the maximum CF values for the decade for wind (validated with the Wind Atlas) and hydro technologies.

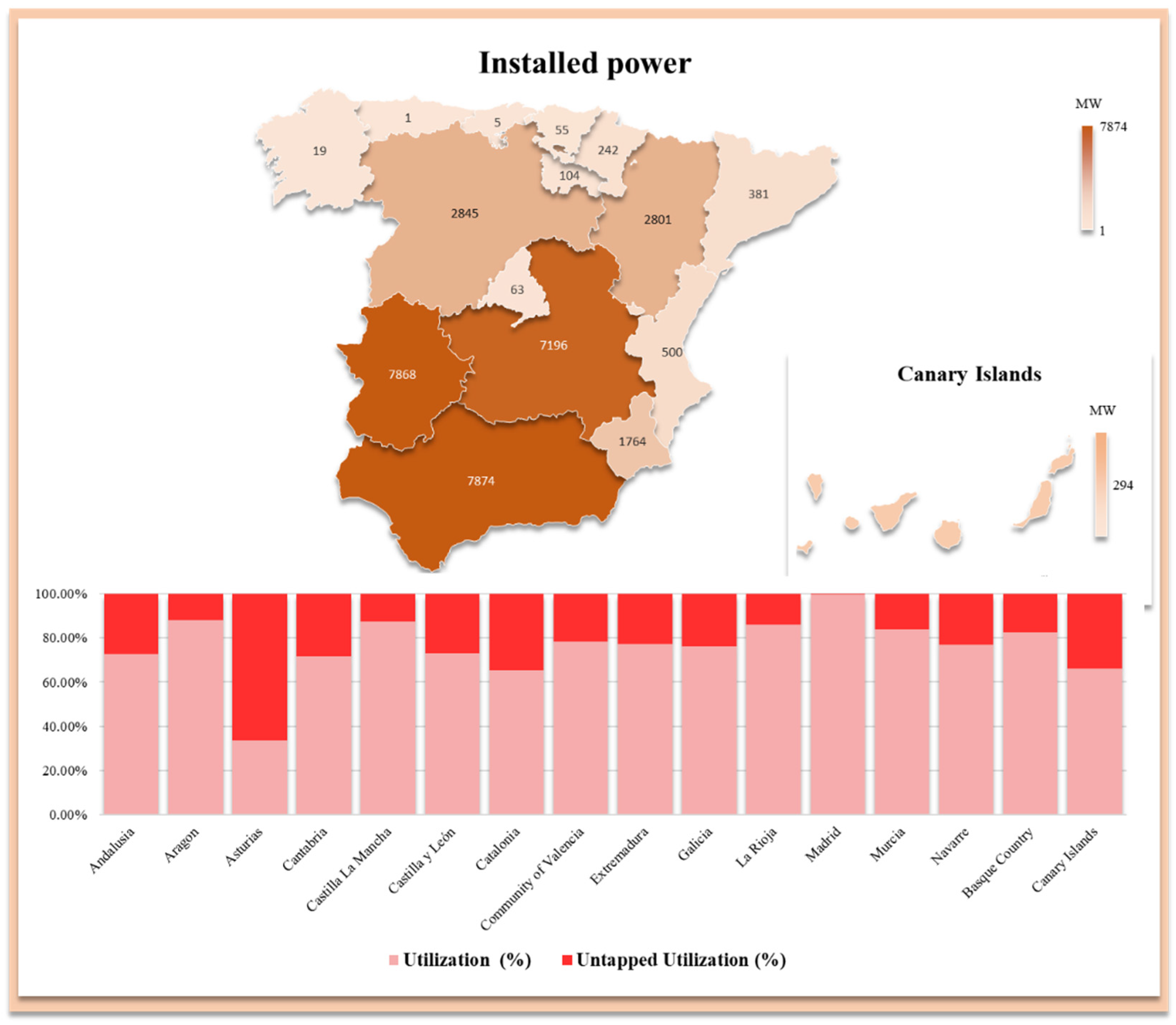

3.1. Photovoltaic Energy Potential

The installed photovoltaic (PV) energy capacity in Spain in 2024 is concentrated mainly in Andalusia (7874 MW), Extremadura (7868 MW) and Castile-La Mancha (7196 MW), which together represent about 72% of the national total. This distribution clearly reflects the levels of solar radiation [

37] and land availability [

38] (

Figure 3).

Despite the high installed capacity, the analysis reveals that a significant portion of the theoretical potential remains unused. In 2024, the unused surplus reached 11,615 GWh, equivalent to 20.88% of the national photovoltaic potential. Regional differences are notable: Madrid makes almost full use of its potential (only 0.28% unused), while Asturias wastes 66.3%. Other regions with high room for improvement are the Canary Islands and Catalonia (~34% of potential unused). Even leading regions like Andalusia and Extremadura see 12–28% untapped potential, a significant reserve for uses like green hydrogen production. These variations might be related to the producer-consumer profile of each region: Madrid, for example, acts mainly as a consumption hub with limited local generation, which reduces the probability of curtailments, whereas Asturias or Catalonia combine relevant industrial demand with substantial renewable deployment capacity, making temporary mismatches between supply and demand more likely. Climatic variability and seasonality could also play a role, since peaks of solar generation may not always coincide with local consumption patterns.

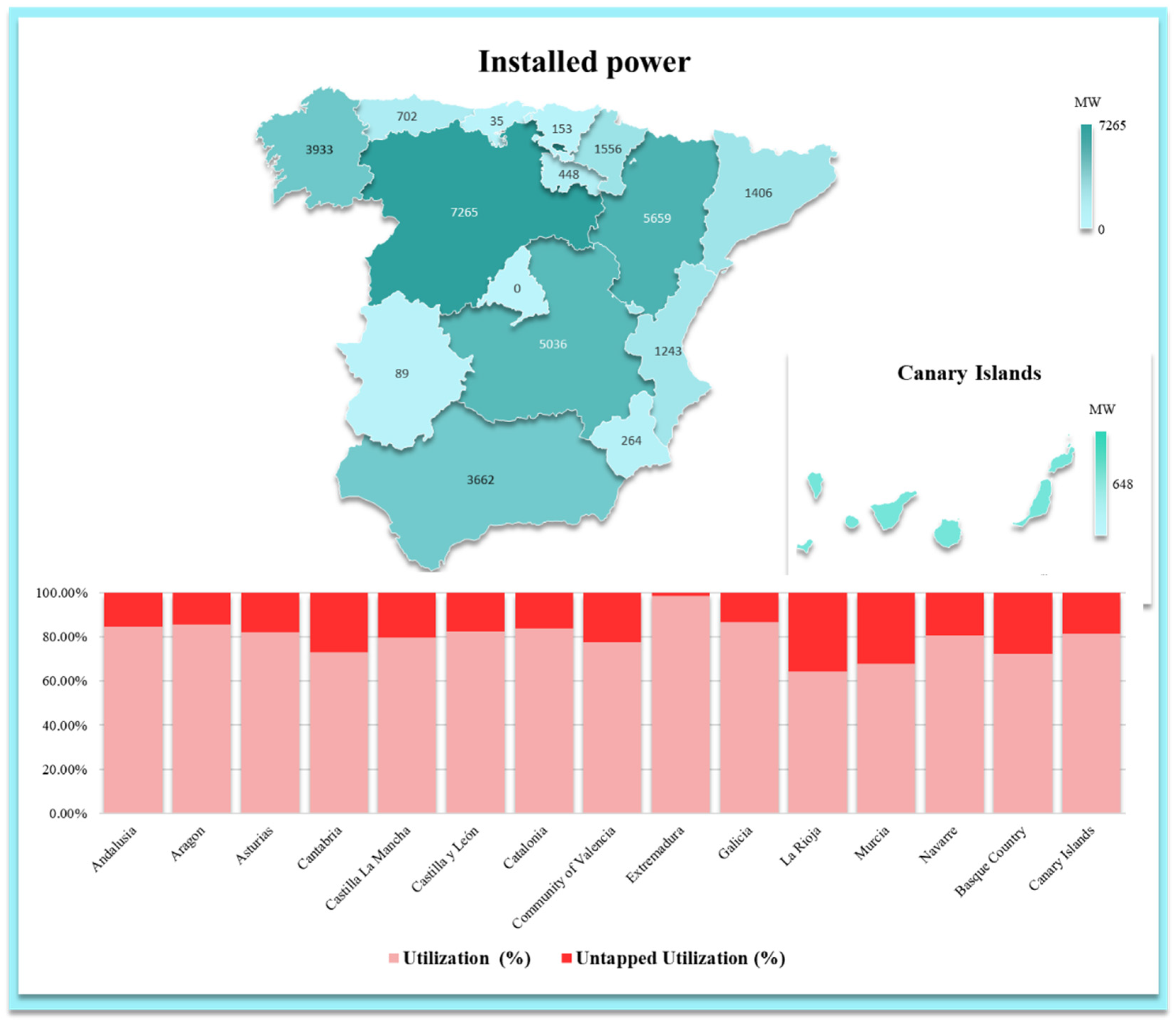

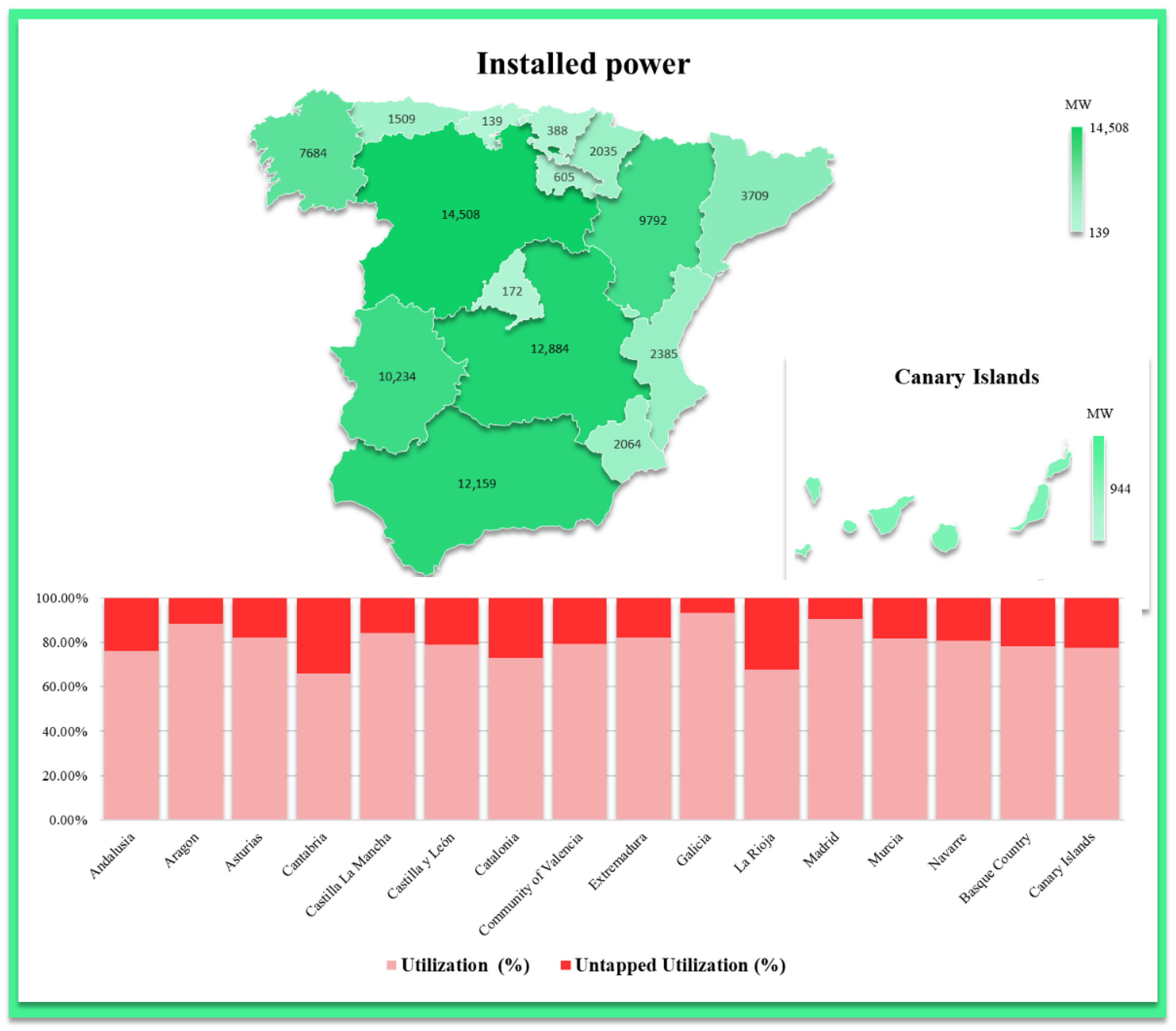

3.2. Wind Energy Potential

The distribution of installed wind power capacity (

Figure 4) also reveals a marked geographical concentration, dominated by Castile and León (7265 MW), Aragon (5659 MW), Castile-La Mancha (5036 MW) and Galicia (3933 MW), which together account for more than 68% of the national total.

In 2024, untapped wind potential amounted to 12,569 GWh, representing 17.1% of the theoretical maximum. There are significant differences between regions: La Rioja and Murcia show untapped potential of more than 30%, while Cantabria and the Basque Country have margins of 20–30%. Extremadura has nearly 99% utilisation, while Castile and León and Aragon still have 14–20% untapped potential, a substantial energy volume.

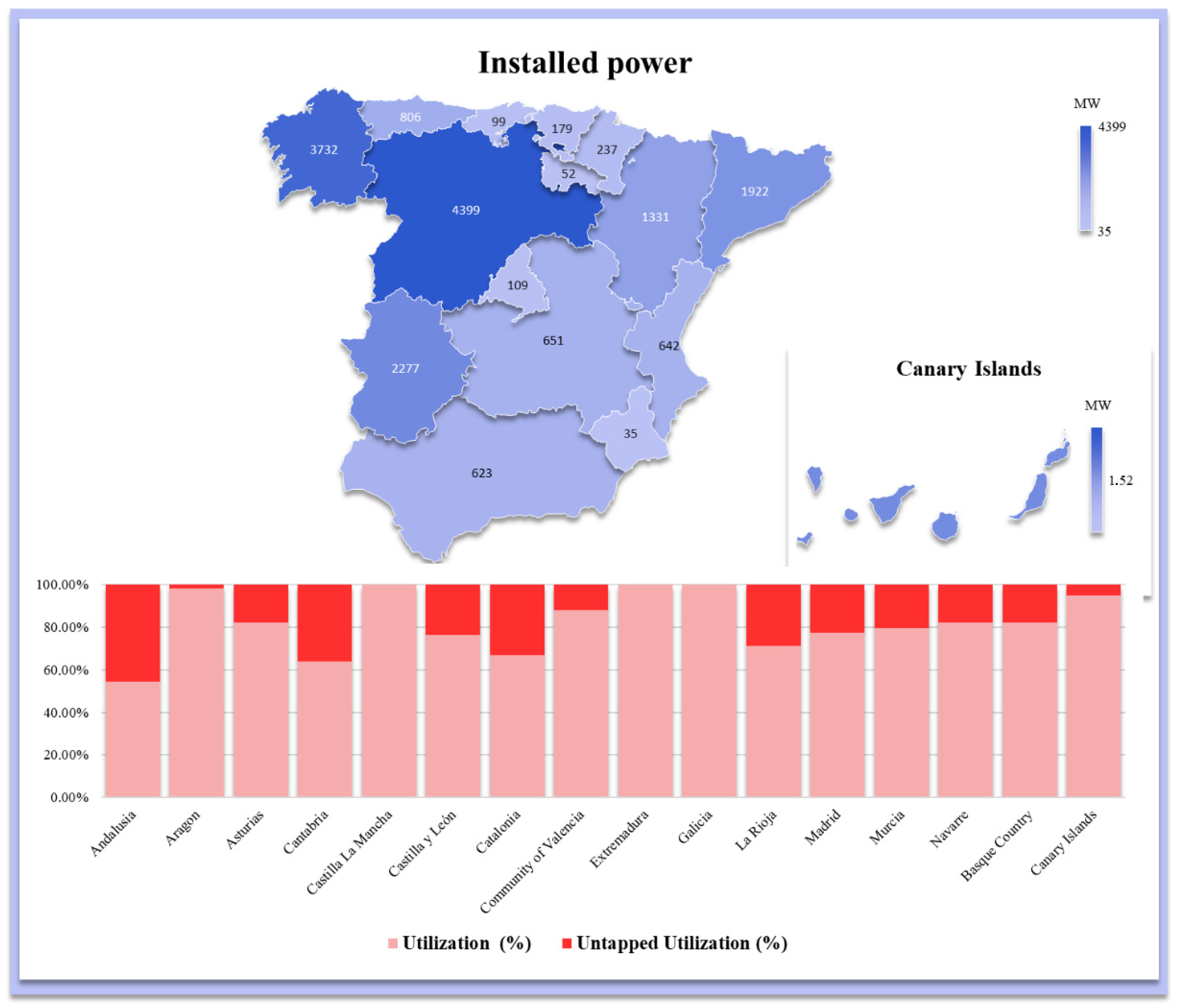

3.3. Hydroelectric Energy Potential

Installed hydroelectric capacity is concentrated in Castile and León (4399 MW), Galicia (3732 MW), Extremadura (2277 MW) and Catalonia (1922 MW), which together account for 72% of the national total (

Figure 5).

In 2024, the untapped hydroelectric potential was 5813 GWh, equivalent to 14.27% of the theoretical total. Galicia, Extremadura and Castile-La Mancha achieved 100% utilisation, while regions such as Andalusia (45.5%), Cantabria (36%), Catalonia (33.1%) and La Rioja (29%) showed significant room for improvement. Despite 76.4% utilisation, Castile and León has the highest unused hydroelectric volume (2719 GWh), followed by Catalonia (1781 GWh), highlighting its role as a flexible reserve.

3.4. Total Combined Unused Potential

Figure 6 summarises the installed capacity and overall utilisation rate of the three renewable sources in each region. Four regions: Castile and León, Castile-La Mancha, Andalusia and Extremadura account for more than 60% of the country’s total installed renewable generation capacity.

At the national level, the combined unused potential amounted to 29,997 GWh, representing about 18% of the theoretical maximum production. Regional disparities are notable: Cantabria and La Rioja have the largest relative margin (>30% unused), while Galicia, Madrid and Aragon lead in operational efficiency (<10% surplus). However, Castile and León and Andalusia, with 21–24% untapped potential, accumulate the largest energy volume for strategic applications. This geographical concentration is consistent with prior evidence of regional specialisation: dominance of photovoltaic in the south/centre and strong wind in Castile and León, reported by Santiago et al. and Sainz-García et al. [

39,

40].

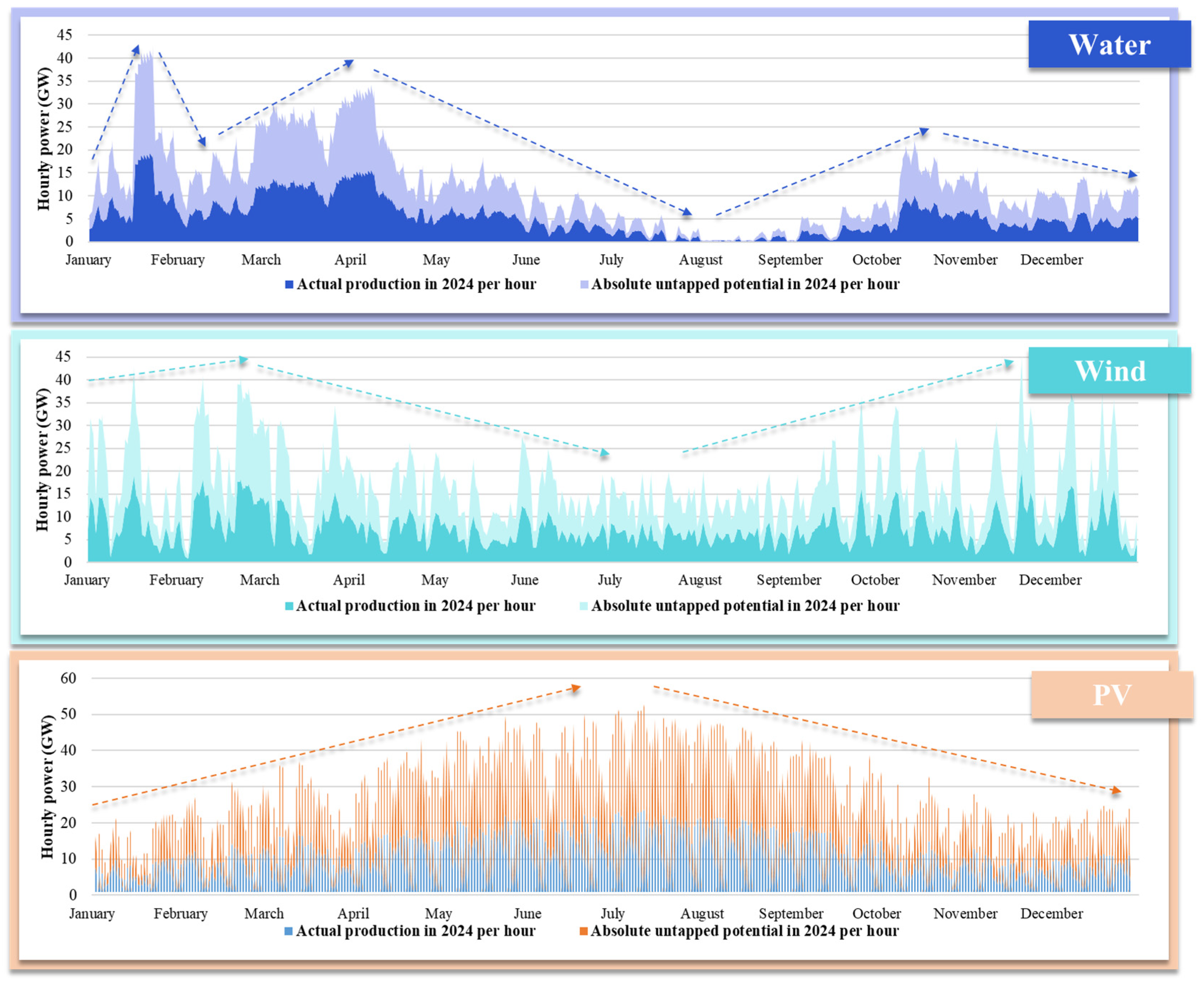

3.5. Temporal Distribution of Unused Potential

Although the total volume of unused renewable energy in 2024 amounts to nearly 30,000 GWh, not all of this energy is directly usable for high-investment industrial processes, such as the production of green hydrogen through electrolysis. This capital-intensive technology requires a high utilisation factor to be economically viable [

41]. It is therefore essential to analyse not only the quantity but also the temporal availability of surplus energy throughout the day and year.

Each renewable source has a distinctive temporal behaviour. Photovoltaic energy shows a highly predictable pattern, with generation concentrated exclusively during daylight hours and a clearly defined peak around midday. In contrast, wind energy is characterised by its stochastic nature, with episodes of high production distributed more randomly throughout both daytime and nighttime hours. As for hydroelectric energy, its profile responds mainly to the seasonality of the water resource, with greater potential during the winter and spring months, coinciding with periods of heavy rainfall and snowmelt. Our analysis of annual data inherently captures these crucial seasonal patterns, such as the clear dominance of photovoltaic surpluses in the summer months and the increased contribution from wind energy during the winter, as can be observed in

Figure 7.

These characteristics have been modelled using hourly capacity factors, based on data provided by Red Eléctrica de España [

42].

Figure 7 shows the combined hourly profile of actual production and absolute unused potential of the three sources analysed (photovoltaic, wind and hydro), highlighting the uneven temporal distribution of energy surplus and its concentration in certain periods.

Based on the analysis of the renewable generation profiles, an optimal operating window for electrolysis was established between 9:00 and 19:00. The decisive factor in this decision was the generation profile of the photovoltaic (PV) power plants, which produce massive energy surpluses exclusively during daylight hours, with a peak around noon. This 9:00–19:00 interval is an economic benchmark, aligning with peak photovoltaic surplus and lowest marginal electricity cost, increasing electrolyser utilisation and cost-effectiveness for competitive green hydrogen production. As the data reveals, this 10-h interval contains the highest concentration of the total untapped potential. Of the total annual untapped potential of nearly 30,000 GWh, a substantial 18,419 GWh, representing over 61%, is available within this timeframe. The chosen window, therefore, not only perfectly captures the peak of solar production but also effectively captures a significant portion of the surpluses from wind and hydro power. From a technical and economic standpoint, this interval is the most rational choice for operating the electrolysis, as it maximises the use of available, otherwise untapped, energy and ensures the most efficient operation. This operational window is also consistent with the typical daily utilisation ranges reported for current electrolyser technologies (around 14 h for AEL, 11 h for PEM, and 13 h for AEM systems), confirming the technical plausibility and industrial relevance of the selected scenario [

30].

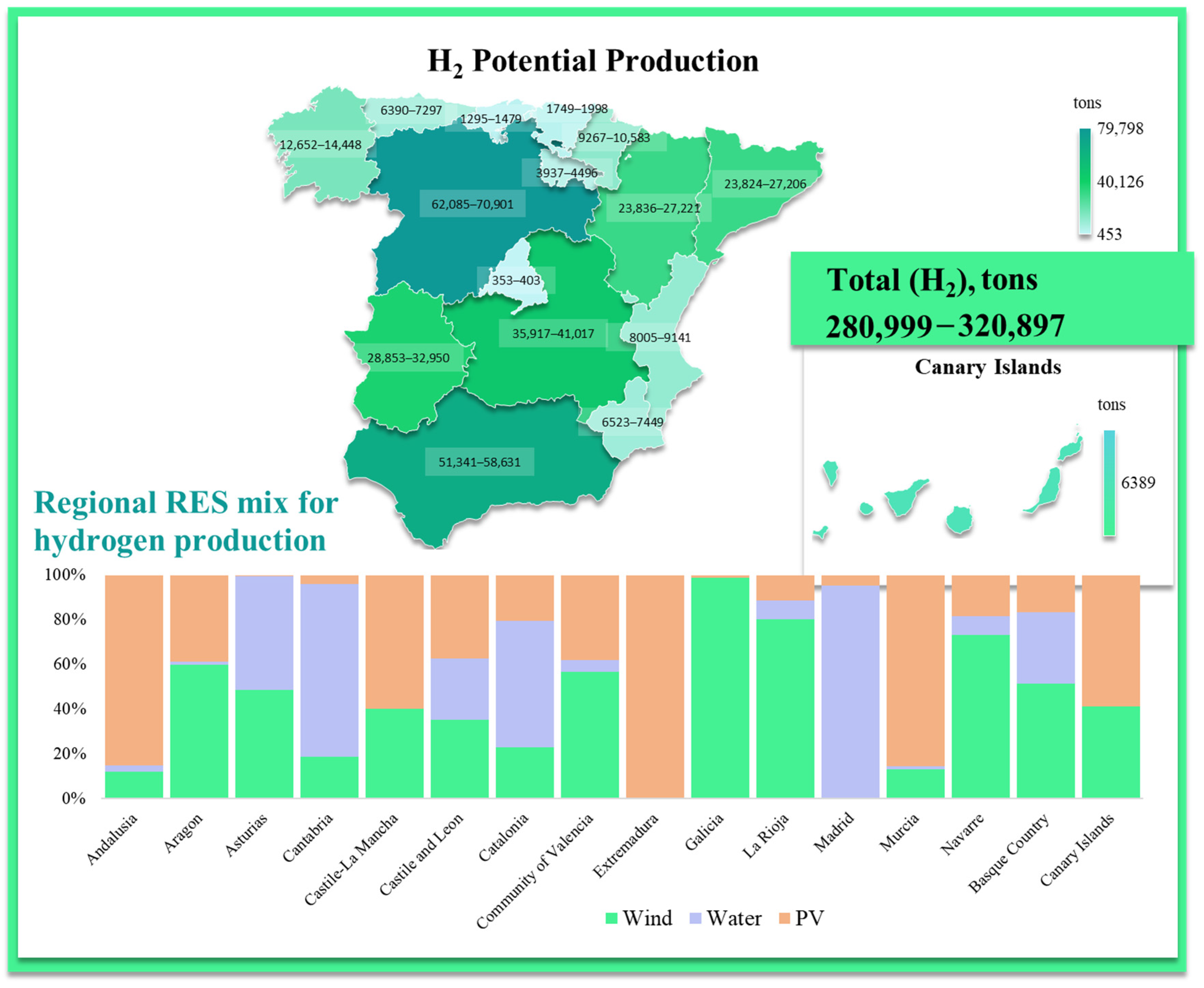

3.6. Green Hydrogen Production Potential

Based on the 18,419 GWh of unused renewable energy concentrated in the economically viable time slot, the potential for green hydrogen production through electrolysis was estimated under three technological scenarios corresponding to Alkaline Electrolysis (AEL), Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM), and Anion Exchange Membrane (AEM) systems. Considering the total energy consumption values defined in

Section 2.4 (57.40 MWh/t H

2 for AEL, 65.55 MWh/t H

2 for PEM, and 59.95 MWh/t H

2 for AEM), the theoretical national hydrogen production potential for 2024 ranges between 280,999 t (PEM) and 320,897 t (AEL), with AEM yielding an intermediate value of 307,247 t.

This theoretical production is unevenly distributed across the country. According to

Table 1, the autonomous communities with the highest installed capacity and largest volume of surpluses, such as Castile and León, Andalusia, Castile-La Mancha and Extremadura, also have the highest volumes of potentially producible hydrogen. Together, these four regions would account for more than 63% of the national total, with Castile and León in the lead (62,085–70,901 t), followed by Andalusia (51,341–58,631 t), Castile-La Mancha (35,917–41,017 t) and Extremadura (28,853–32,950 t). This pattern reflects both the concentration of renewable infrastructure and the geographical availability of the resource.

Figure 8 illustrates the regional potential for green hydrogen production in 2024, as well as the composition of the renewable energy mix that would feed this production in each autonomous community. This representation allows us to identify not only the estimated total volume, but also the predominant source of renewable energy used in each region.

As can be seen in the graph, southern Spain would depend mainly on photovoltaic energy, while regions such as Galicia would rely almost exclusively on wind power. In other areas, such as Asturias or Catalonia, hydropower would make a significant contribution. Castile and León stands out for its diversified energy mix, as solar, wind and hydro sources contribute in a balanced way to potential hydrogen production. This not only maximises total output but also enhances the stability and operational flexibility of the electricity supply for electrolysis.

Overall, the estimated production potential, ranging from 280,999 to 320,897 t depending on the electrolysis technology, represents a technical upper limit based on the most favourable climatic conditions of the past decade. Actual production will inevitably depend on interannual variability and on economic, regulatory and infrastructural factors. Even so, these figures provide a realistic benchmark for territorial planning of electrolysers and for defining national strategies to deploy green hydrogen as a key energy vector.

Finally, regional differences in hydrogen potential also reflect the availability of supporting infrastructure. Regions such as Castile and León, Andalusia, Castile-La Mancha and Extremadura combine high renewable capacity with favourable conditions for large-scale hydrogen projects, including proximity to existing gas networks [

43,

44] and potential underground storage in depleted gas fields and salt formations [

45,

46]. This convergence between resource availability and infrastructure readiness positions them as strategic hubs for hydrogen production and storage in Spain.

4. Discussion

4.1. Validation and Limitations of the Methodological Approach

This study adopts a theoretical approach aimed at identifying the upper limit of green hydrogen production potential from untapped renewable sources in Spain during 2024. To this end, historical data on installed capacity and actual production by region have been used, together with maximum capacity factor (CF) values observed over the last decade, validated with geospatial models such as the Global Wind and Solar Atlas. This methodology allows us to approximate the optimal performance achievable by each technology under favourable climatic conditions, avoiding both overestimation (due to the use of average CF) and distortion due to outliers.

While we acknowledge our deterministic model’s limitations, our primary objective was to demonstrate the conceptual viability of harnessing surpluses for hydrogen production—a conclusion unaffected by minor variations in the final output figure. For future work, methods like Monte Carlo simulation would be ideal to systematically assess how the potential is impacted by uncertainties such as climatic variability and policy changes, building upon the baseline established here.

However, this approach also has limitations inherent to its static and theoretical nature. Firstly, the choice of the maximum CF value does not guarantee that this performance can be maintained consistently in the future, given the interannual variability of renewable resources. Furthermore, operational constraints such as facility maintenance, technical failures, evacuation losses or regulatory constraints have not been considered. On the other hand, the application of a 10-h daily operating window is a reasonable simplification to represent an economically viable scenario, but it does not accurately reflect the actual operating profile of an electrolyser coupled to a hybrid system or one that responds dynamically to hourly market prices.

Despite these limitations, the approach adopted provides a solid and conservative methodological basis, valid for dimensioning strategic planning scenarios and realistically assessing the potential for valorising renewable surpluses through green hydrogen.

4.2. Integrated Interpretation and Technological Relevance

Our results indicate that in 2024, nearly 18% of Spain’s theoretical renewable potential (≈30,000 GWh) remained unutilized, with around 18,419 GWh concentrated within the optimal 9:00–19:00 operating window. The conversion of this surplus into green hydrogen depends on the selected technology, yielding between 280,999 t (PEM) and 320,897 t (AEL), with AEM in an intermediate position (

Section 3.6). This output represents a significant energy opportunity, capable of supplying approximately 5.8–6.7% of the projected European industrial hydrogen demand for 2030 [

47].

These figures are consistent with strategies proposed in the literature that position hydrogen as a means of grid stabilisation and long-term storage of surplus renewable energy [

44,

48]. Studies by Brey and Back et al., in particular, highlight hydrogen’s strategic role in managing seasonal surpluses and balancing renewable variability, confirming the systemic value of converting curtailed electricity into a storable and tradable energy vector. The concentration of over 60% of the annual surplus within a predictable daytime window further supports this concept, defining a clear operational niche for electrolysis under economically favourable conditions [

49,

50].

Moreover, operating within this interval aligns with the daily utilisation ranges reported for AEL, PEM and AEM systems and promotes stable operation with limited cycling [

30]. The total energy figures adopted (

Section 2.4) include all auxiliary processes (cooling, gas purification, compression, water treatment, etc.), thereby providing a realistic whole-plant representation. From a technological standpoint, AEL and PEM are consolidated commercial technologies, while AEM is emerging as a promising option combining efficiency and operational flexibility. Consequently, technology selection can be tailored to regional renewable profiles, infrastructure conditions and project scale, consistent with the spatial patterns identified in the Results section.

4.3. Regional Inequality, Infrastructure Constraints and Resource Considerations

The regional concentration of potential (over 63% located in Castile and León, Andalusia, Castile-La Mancha and Extremadura) reflects both natural resource endowment and infrastructural readiness, as already discussed in

Section 3.4. Yet the feasible potential is conditioned by a range of territorial, environmental and technical factors.

Large-scale renewable deployment can generate spatial tensions, as projects often compete with agricultural activities, conservation priorities and urban expansion. Hydropower potential, in particular, remains constrained by river-basin morphology, competing water uses and strict environmental regulation [

51]. At the same time, renewable installations can alter landscapes, fragment habitats, or reduce ecosystem services if not guided by robust spatial planning, and they sometimes face social resistance related to land rights and local consent [

52,

53].

Technical and infrastructural barriers also shape the realisable potential. The best solar and wind resources are frequently located far from demand centres and existing transmission capacity, creating bottlenecks and increasing the cost of grid reinforcement or energy storage [

54]. Variability in wind and solar generation further accentuates the need for overcapacity, storage or long-distance transmission, while hydropower facilities rely on ageing assets and are increasingly exposed to hydrological uncertainty [

55,

56].

Water use for electrolysis (≈11–18 L/kg H

2 [

30]; ≈3.3–5.9 million m

3/yr at national scale) is modest overall—less than 0.25% of Spain’s total freshwater use [

57]—but may become locally critical in arid regions such as Andalusia or Castile-La Mancha. In these areas, desalination and wastewater reuse offer viable alternatives at marginal additional energy cost. Logistics for other auxiliary supplies (nitrogen for purging, compressed air for instrumentation) depend on the maturity of local industrial ecosystems.

Although not explicitly modelled, the spatial results highlight where distributed electrolyser deployment, underground storage development and targeted grid reinforcement could unlock the most practical potential for large-scale hydrogen production in Spain.

4.4. Policy and Investment Outlook and 2030 Perspective

Realising the technical potential identified in this study requires a coherent mix of policy, infrastructure and investment instruments capable of translating renewable surpluses into bankable hydrogen capacity. Water security remains a critical factor in arid regions and must be integrated into project design and permitting processes [

58]. Achieving competitive production costs below €4/kg will depend on maximising electrolyser utilisation, exploiting economies of scale and fostering integration with existing industrial clusters [

59].

At the European and national levels, several complementary initiatives are already shaping this enabling framework. In Spain, the H

2 Pioneros and H

2 Valles programmes, coordinated by IDAE and MITERD under the national Hydrogen Roadmap, are financing pioneering and ecosystem-scale projects that demonstrate regional hydrogen value chains [

60,

61]. At the EU level, the Hydrogen Bank auctions, Innovation Fund Contracts for Difference (CfDs), and the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) collectively improve the risk-return profile of renewable hydrogen projects by ensuring predictable revenue streams and enhancing competitiveness against fossil-based alternatives [

62,

63,

64]. Together with the ongoing regulatory harmonisation under the EU Delegated Acts on renewable fuels, these instruments are progressively consolidating a supportive market architecture for large-scale electrolysis deployment.

When positioning hydrogen within the broader storage landscape, it is important to consider the performance and limitations of alternative technologies. Battery storage, while highly flexible and increasingly cost-competitive, continues to face significant economic and regulatory barriers in Spain due to limited market remuneration and high cycle costs [

65]. Pumped hydro storage remains the most mature large-scale storage option, yet its expansion is geographically constrained and often subject to environmental permitting challenges [

66]. By contrast, hydrogen storage offers unique advantages in long-duration and seasonal balancing, with recent analyses showing competitive Levelised Cost of Storage (LCOS) values when integrated with underground facilities and existing gas infrastructure [

67]. This complementarity reinforces hydrogen’s systemic role as a bridge between short-term flexibility (batteries, pumped hydro) and long-term energy security.

Looking ahead to 2030, Spain’s National Energy and Climate Plan (PNIEC) projects a near doubling of installed renewable capacity compared to 2024. Applying the same methodological approach, this would yield approximately 31.47 TWh of untapped renewable energy (≈11.12% of the theoretical maximum), of which around 6.95% would coincide with the economically viable operating window identified in this study. This corresponds to a green hydrogen production potential of 300,155–342,772 tonnes per year, depending on the electrolyser technology adopted, figures consistent with long-term European projections for surplus valorisation and hydrogen-based storage [

48]. These estimates highlight Spain’s potential to become a leading hydrogen hub in southern Europe, leveraging its renewable abundance and strategic location.

Ultimately, the materialisation of this scenario will depend on the capacity of public institutions, network operators and private investors to align regulation, infrastructure and technological innovation. Strengthening cross-sectoral coordination, accelerating permitting, and prioritising integrated projects that link renewable generation, storage, and industrial consumption will be decisive for transforming Spain’s technical potential into a globally competitive hydrogen economy.

5. Conclusions

This study has made it possible to estimate, based on historical data and validated theoretical models, the maximum potential for green hydrogen production from untapped renewable energies in Spain during 2024. By analysing the difference between the theoretical and actual production of solar photovoltaic, wind and hydraulic technologies, a national energy surplus of 29,997 GWh has been identified, of which 18,419 GWh are concentrated within an economically viable operating window for electrolysis (9:00–19:00).

Depending on the specific electrolysis technology considered, this surplus could have resulted in a theoretical hydrogen production ranging from 280,999 tonnes (PEM) to 320,897 tonnes (AEL), with AEM yielding an intermediate value of 307,247 tonnes. This range represents a significant contribution to the decarbonisation of the energy system, particularly in sectors that are difficult to electrify. Although these values correspond to a theoretical upper limit, conditioned by the simultaneous occurrence of optimal renewable generation, they provide a strategic reference for assessing Spain’s capacity to transform its electricity system through the integration of hydrogen technologies.

The research reveals a clear geographical concentration of untapped potential, with more than 63% located in four regions (Castile and León, Andalusia, Castile-La Mancha and Extremadura). This finding suggests that territorial planning for the deployment of electrolysers and storage systems should consider criteria of geographical efficiency, existing infrastructure and availability of renewable resources in order to maximise technical and economic performance.

Likewise, the results obtained reinforce hypotheses previously formulated in the literature on the role of green hydrogen as a solution for storing renewable surpluses, particularly photovoltaic, and as a vector of flexibility and balance for the electricity system. The analysis also confirms that the effective implementation of this potential will depend on overcoming key barriers such as water availability, economic profitability, sectoral integration and investment in transport and storage infrastructure, including underground solutions such as salt caverns or adapted gas networks.

In short, this study shows that Spain has significant technical potential for the production of green hydrogen from unused renewable energy. Realising this potential will require coordinated action between administrations, the private sector and scientific institutions, with the aim of consolidating a robust and efficient hydrogen ecosystem that is aligned with European climate neutrality and energy sovereignty objectives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P.C. and M.M.; methodology, D.P.; software, M.M. and M.T.; validation, J.P.C., I.A. and P.T.; formal analysis, J.P.C. and D.P.; investigation, J.P.C. and M.M.; resources, D.P. and I.A.; data curation, M.T.; writing—original draft preparation, J.P.C.; writing—review and editing, M.M.; visualisation, D.P.; supervision, M.T. and P.T.; project administration, I.A.; funding acquisition, J.P.C. and M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RES | Renewable Energy Sources |

| CF | Capacity Factor |

| REE | Red Eléctrica de España |

References

- European Commission. Regulation (EU) 2021/1119 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 June 2021 Establishing the Framework for Achieving Climate Neutrality and Amending Regulations (EC) no 401/2009 and (EU) 2018/1999 (‘European Climate Law’). 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2021/1119/oj/eng (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Vivanco-Martín, B.; Iranzo, A. Analysis of the European Strategy for Hydrogen: A Comprehensive Review. Energies 2023, 16, 3866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, J.; McLellan, B. A Historical Analysis of Hydrogen Economy Research, Development, and Expectations, 1972 to 2020. Environments 2023, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.; Mehrpooya, M. A comprehensive review on coupling different types of electrolyzer to renewable energy sources. Energy 2018, 158, 632–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.E.; Wahid, M.A. Hydrogen production from renewable and sustainable energy resources: Promising green energy carrier for clean development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 57, 850–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento da Silva, G.; Rochedo, P.R.R.; Szklo, A. Renewable hydrogen production to deal with wind power surpluses and mitigate carbon dioxide emissions from oil refineries. Appl. Energy 2022, 311, 118631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Maaroufi, A.; Daoudi, M.; Laamara, R.A. Hydrogen production for SDG 13 using hybrid renewables energies in southern Morocco. Energy 2025, 319, 134986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, G.; Lindorfer, J. Evaluating CO2 sources for power-to-gas applications—A case study for Austria. J. CO2 Util. 2015, 10, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenhumberg, N.; Büker, K. Ecological and Economic Evaluation of Hydrogen Production by Different Water Electrolysis Technologies. Chem. Ing. Tech. 2020, 92, 1586–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auguadra, M.; Ribó-Pérez, D.; Gómez-Navarro, T. Planning the deployment of energy storage systems to integrate high shares of renewables: The Spain case study. Energy 2023, 264, 126275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Calvet, R.; Martínez-Duart, J.M.; Gómez-Calvet, A.R. The 2030 power sector transition in Spain: Too little storage for so many planned solar photovoltaics? Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 174, 113094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, B.; Lee, K.-T.; Lee, C.S.; Song, C.-K.; Maskey, R.K.; Ahn, S.-H. A novel off-grid hybrid power system comprised of solar photovoltaic, wind, and hydro energy sources. Appl. Energy 2014, 133, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Tan, Q.; Fang, G.; Wen, X. Hydrogen production to combat power surpluses in hybrid hydro–wind–photovoltaic power systems. Appl. Energy 2024, 371, 123627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Red Eléctrica. Estructura de la Generación por Tecnologías. 2024. Available online: https://www.ree.es/es/datos/generacion/estructura-generacion?start_date=2025-07-25T00:00&end_date=2025-08-01T23:59&time_trunc=day&systemElectric=nacional (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico. Hydrogen Roadmap: A Commitment to Renewable Hydrogen. Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/ministerio/planes-estrategias/hidrogeno.html (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Borge-Diez, D.; Rosales-Asensio, E.; Icaza, D.; Açıkkalp, E. The green hydrogen-water-food nexus: Analysis for Spain. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 77, 1026–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.-T.-H.; Riva Sanseverino, E.; Nguyen, Q.-N.; di Silvestre, M.L.; Favuzza, S.; Nguyen, D.Q.; Musca, R. Solving congestions with pumped hydro storage under high penetration of renewable energy in Vietnam: The case of Ninh Thuan HV grid. Renew. Energy Focus 2024, 51, 100638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. Renewable-storage sizing approaches for centralized and distributed renewable energy—A state-of-the-art review. J. Energy Storage 2024, 100, 113688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, I.; Ullah, S.; Sohail, S.; Sohail, M.T. How do digital government, circular economy, and environmental regulatory stringency affect renewable energy production? Energy Policy 2025, 203, 114634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Guan, B.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, T.; Liu, X.; Wang, X. Application potential of rooftop photovoltaics (PV) in elevated metro station for a low-carbon future: Characteristic analysis and strategies for supply-demand mismatch. Renew. Energy 2025, 238, 121983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, K.; Fan, X.; Zheng, L. Cost analysis on hydrogen production via water electrolysis. Mod. Chem. Ind. 2021, 41, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Ramos, J.A.; Arias, I.; Escobar, R.A.; Pérez-García, M. Assessing green hydrogen production potential using photovoltaic solar energy in industrial buildings of southeastern Spain. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 112, 418–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoes, S.G.; Amorim, F.; Siggini, G.; Sessa, V.; Saint-Drenan, Y.-M.; Carvalho, S.; Mraihi, H.; Assoumou, E. Climate proofing the renewable electricity deployment in Europe—Introducing climate variability in large energy systems models. Energy Strategy Rev. 2021, 35, 100657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, M.; Khan, M.A.; Aurangzeb, K.; Alhussein, M.; Jamal, M.A. Comprehensive techno-economic analysis of a standalone renewable energy system for simultaneous electrical load management and hydrogen generation for Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 6255–6274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, M.; Megahed, T.F.; Ookawara, S.; Hassan, H. Techno-economic assessment of clean hydrogen production and storage using hybrid renewable energy system of PV/Wind under different climatic conditions. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 52, 102195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Solar Atlas. Global Solar Atlas. Available online: https://globalsolaratlas.info/map (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Global Wind Atlas. Global Wind Atlas. Available online: https://globalwindatlas.info/en/ (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Red Eléctrica de España (REE). National Electrical Balance. Available online: https://www.ree.es/es/datos/balance/balance-electrico?start_date=2024-01-01T00:00&end_date=2024-12-31T23:59&time_trunc=year&systemElectric=nacional (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- WeMake Consultores. Capacity Factor in Renewables. Available online: https://wemakeconsultores.com/en/capacity-factor-in-renewables/ (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Devrim, Y.; Öztürk, R.A. The design and techno-economic evaluation of wind energy integrated on-site hydrogen fueling stations for different electrolyzer technologies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 159, 150597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Lang, J.; Yuan, W.; An, G.; Lei, T.; Junhao, Y. A comprehensive review of advances and challenges of hydrogen production, purification, compression, transportation, storage and utilization technology. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2026, 226, 116196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietra, A.; Gianni, M.; Zuliani, N.; Malabotti, S.; Taccani, R. Experimental Characterization of an Alkaline Electrolyser and a Compression System for Hydrogen Production and Storage. Energies 2021, 14, 5347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelghany, M.B.; Shafiqurrahman, A.; Al-Durra, A.; Mohamed, M.; Hu, J.; Vaccaro, A.; Gao, F.; el Moursi, M.S. Hydrogen energy systems for decarbonizing smart cities and industrial applications: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2026, 226, 116370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, C.; Wang, Z.; Deng, H.; Li, S.; Pan, S.; Li, Z. Coordinated hydrogen storage Strategy: Integrating underground salt caverns and surface tanks for stable and scalable hydrogen supply. Fuel 2026, 406, 137010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, J.; Li, Y.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, X.; Chen, Z. Techno-economic-environmental assessment of cushion gas and injection strategy for optimizing hydrogen storage efficiency in underground aquifers. J. Energy Storage 2025, 138, 118633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cai, S.; Chen, R.; Tu, Z.; Li, S. Operation strategy optimization of an integrated proton exchange membrane water electrolyzer and batch reverse osmosis desalination system powered by offgrid wind energy. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 22, 100607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Tan, C.L.; Lu, Y.; Qu, Y.; Liu, J. Solar radiation and daily light integral characteristics of photovoltaic-green roof system in tropical area: A case study in Singapore. Sol. Energy 2024, 279, 112807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanda, M.G.; Emam, M.; Hassan, H. Evaluation of dual use land for wind turbine and solar photovoltaic hybrid system using new shading technique: Egypt maps as case study. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 344, 120289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, I.; Palacios-Garcia, E.J.; Gonzalez-Redondo, M.; Arenas-Ramos, V.; Simon, B.; Hayes, B.P.; Moreno-Munoz, A. Assessment of generation capacity and economic viability of photovoltaic systems on urban buildings in southern Spain: A socioeconomic, technological, and regulatory analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 203, 114741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainz-Garcia, A.; Abarca, E.; Rubi, V.; Grandia, F. Assessment of feasible strategies for seasonal underground hydrogen storage in a saline aquifer. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 16657–16666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, V.; Desmet, J.; Knockaert, J.; Develder, C. Improving the utilization factor of a PEM electrolyzer powered by a 15 MW PV park by combining wind power and battery storage—Feasibility study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 16468–16478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Red Eléctrica de España (REE). 2024 Report—Renewables in the Spanish Electricity System. Available online: https://www.sistemaelectrico-ree.es/es/informe-de-energias-renovables (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Abánades, A.; de Gracia, M.D.S.; Martínez Fondón, P.; Saborit, E. Design of a flexible, modular, scalable infrastructure to inland intake of offshore hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 142, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brey, J.J. Use of hydrogen as a seasonal energy storage system to manage renewable power deployment in Spain by 2030. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 17447–17457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pous de la Flor, J.; Martínez-Hernando, M.-P.; Paredes, R.; Garcia-Franco, E.; Cabello Pous, J.; Ortega, M.F. Waste as a Source of Fuel and Developments in Hydrogen Storage: Applied Cases in Spain and Their Future Potential. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle-Falcones, L.M.; Grima-Olmedo, C.; Mazadiego-Martínez, L.F.; Hurtado-Bezos, A.; Eguilior-Díaz, S.; Rodríguez-Pons, R. Green Hydrogen Storage in an Underground Cavern: A Case Study in Salt Diapir of Spain. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serna, S.; Cossent, R. El hidrógeno como vector de descarbonización: Situación actual en España y retos a futuro. Papeles Energ. 2024, 25, 2445–2726. Available online: https://www.funcas.es/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Papeles-de-energia_25_2.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Back, C.; González-Morán, L.; Iranzo, A. Green hydrogen from renewable surplus: Production and storage potential in Spain’s 2040 energy horizon. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 140, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aso Aguarta, I.; Correas Usón, L. Wind energy and hydrogen, a previous symbiosis, have been announced. DYNA 2008, 83, 127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, N.; Tanneberger, M.A.; Höck, M. Levelized cost of hydrogen production in Northern Africa and Europe in 2050: A Monte Carlo simulation for Germany, Norway, Spain, Algeria, Morocco, and Egypt. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 69, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonelli, D.; Rosa, L.; Gabrielli, P.; Caldeira, K.; Parente, A.; Contino, F. Global land and water limits to electrolytic hydrogen production using wind and solar resources. Nat Commun. 2023, 14, 5532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salak, B.; Hunziker, M.; Grêt-Regamey, A.; Spielhofer, R.; Hayek, W.; Kienast, F. Shifting from techno-economic to socio-ecological priorities: Incorporating landscape preferences and ecosystem services into the siting of renewable energy infrastructure. PLoS ONE 2025, 19, e0298430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picchi, P.; Van Lierop, M.; Geneletti, D.; Stremke, S. Advancing the relationship between renewable energy and ecosystem services for landscape planning and design: A literature review. Ecosyst. Serv. 2019, 35, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabtree, G.; Misewich, J.; Ambrosio, R.; Clay, K.; Demartini, P.; James, R.; Lauby, M.; Mohta, V.; Moura, J.; Sauer, P.; et al. Integrating Renewable Electricity on the Grid. AIP Conf. Proc. 2011, 1401, 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttler, A.; Dinkel, F.; Franz, S.; Spliethoff, H. Variability of wind and solar power—An assessment of the current situation in the European Union based on the year 2014. Energy 2016, 106, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaner, M.; Davis, S.; Lewis, N.; Caldeira, K. Geophysical constraints on the reliability of solar and wind power in the United States. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 914–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). Volumen de Agua Registrado y Distribuido a Los Usuarios. 2022. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736176834&menu=ultiDatos&idp=1254735976602 (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Borba, P.C.S.; Gonçalves, A.R.; Costa, R.S.; Cumplido, M.A.; Martins, F.R. Integrating renewable energy for power security under water stress scenarios due to climate change: Strategies and opportunities. Energy 2025, 326, 136169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Martín, G.; Judez, X.; Aguado, M.; Garbayo, I. Techno-economic assessment of MW-scale solid oxide electrolysis hydrogen production plant: Integrating possibilities in Spain. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 142, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto para la Diversificación y Ahorro de la Energía (IDAE); Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico. Programa H2 Pioneros. Ayudas para Proyectos Pioneros y Singulares de Hidrógeno Renovable. Available online: https://www.idae.es/ayudas-y-financiacion/programa-h2-pioneros-ayudas-para-proyectos-pioneros-y-singulares-de-hidrogeno (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Instituto para la Diversificación y Ahorro de la Energía (IDAE); Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico. Programa VALLES DE H2. Ayudas para Proyectos de Producción y Consumo de Hidrógeno Renovable (Clústeres o Valles). Available online: https://www.idae.es/ayudas-y-financiacion/programa-valles-de-h2 (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- European Climate, Infrastructure and Environment Executive Agency (CINEA). Primera Convocatoria para la Concesión Directa de Ayudas a Proyectos Españoles por su Participación en el Esquema «Subasta Como Servicio» del Banco Europeo del Hidrógeno. Available online: https://www.prtr.miteco.gob.es/es/ayudas/catalogo-de-ayudas/primera-convocatoria-para-la-concesion-directa-de-ayudas-a-proye.html (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- European Commission. Innovation Fund IF25 Hydrogen Auction. Available online: https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/eu-funding-climate-action/innovation-fund/competitive-bidding_en (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- European Commission. EU Emissions Trading System. Available online: https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/carbon-markets/eu-emissions-trading-system-eu-ets_en (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Hu, Y.; Soler Soneira, D.; Sánchez, M.J. Barriers to grid-connected battery systems: Evidence from the Spanish electricity market. J. Energy Storage 2021, 35, 102262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naval, N.; Yusta, J.M. Assessment of the impact of electricity market prices on pumped hydro storage operation with renewable generation. Energy 2025, 336, 138426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez de León, C.; Ríos, C.; Molina, P.; Brey, J.J. Levelized Cost of Storage (LCOS) for a hydrogen system. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 52, 1274–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).