Acoustic Emission Characteristic Parameters and Damage Model of Cement-Modified Aeolian Sand Compression Failure

Abstract

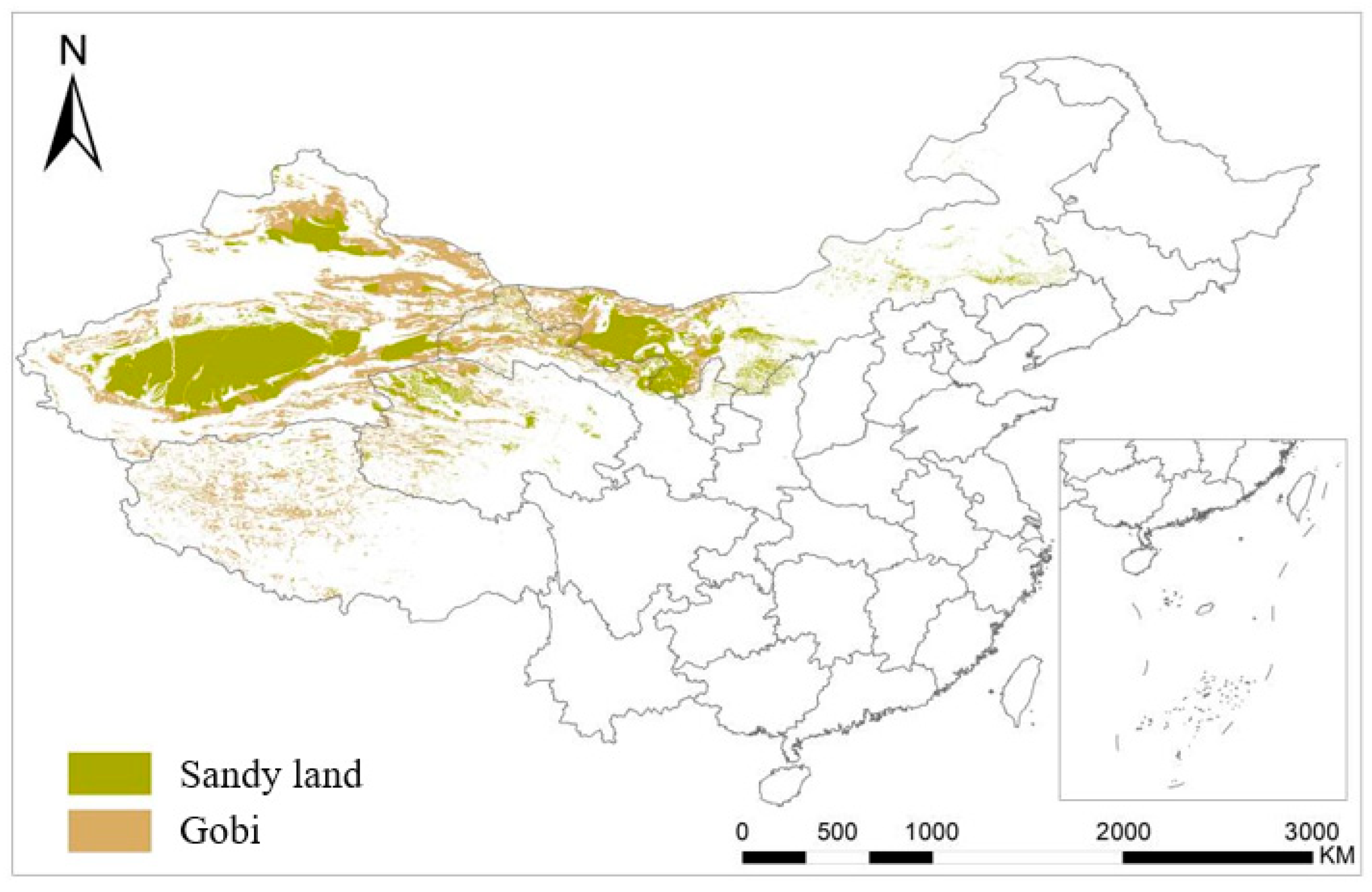

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Equipment and Scheme

2.1. Experimental Materials

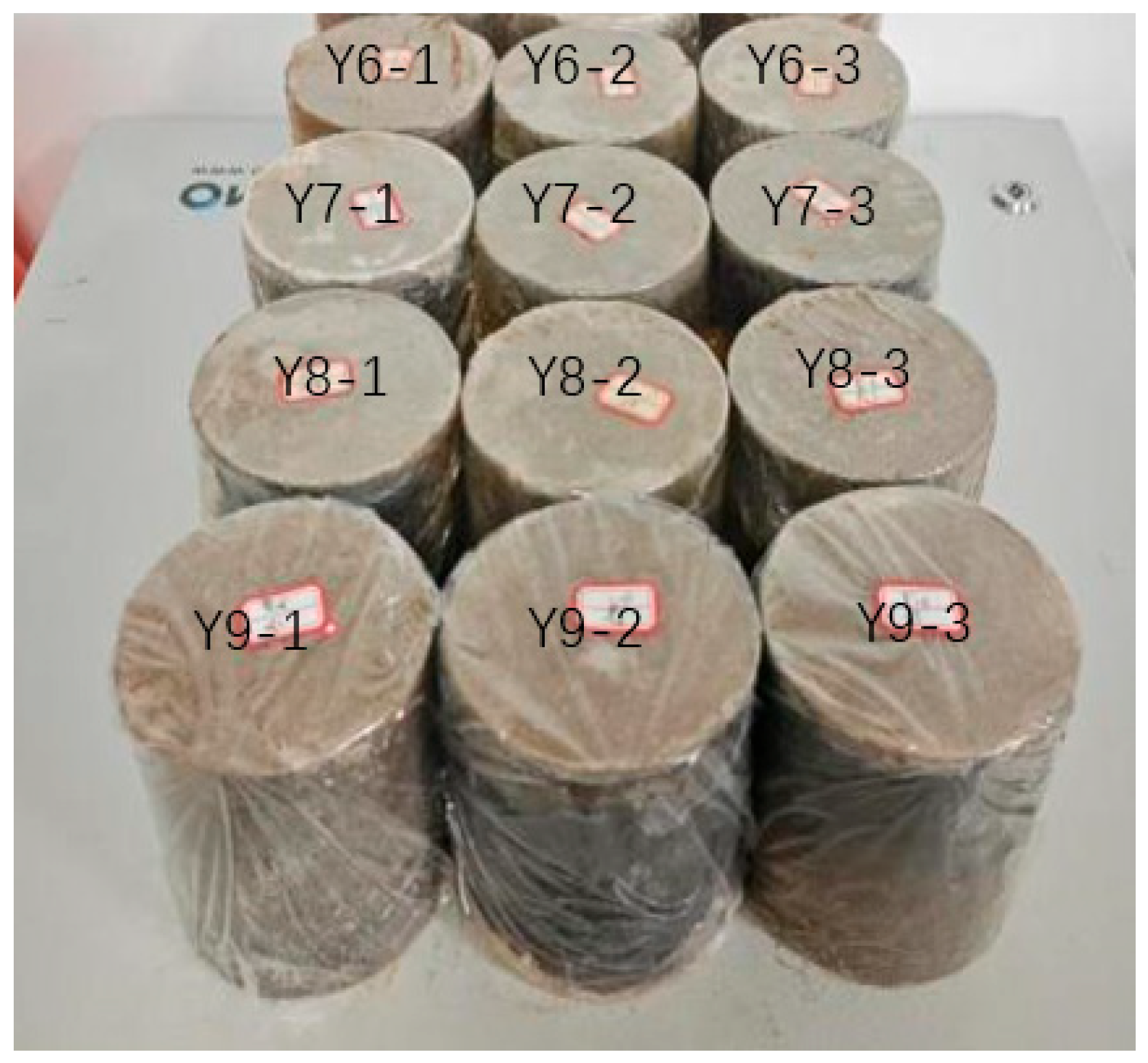

2.2. Sample Preparation

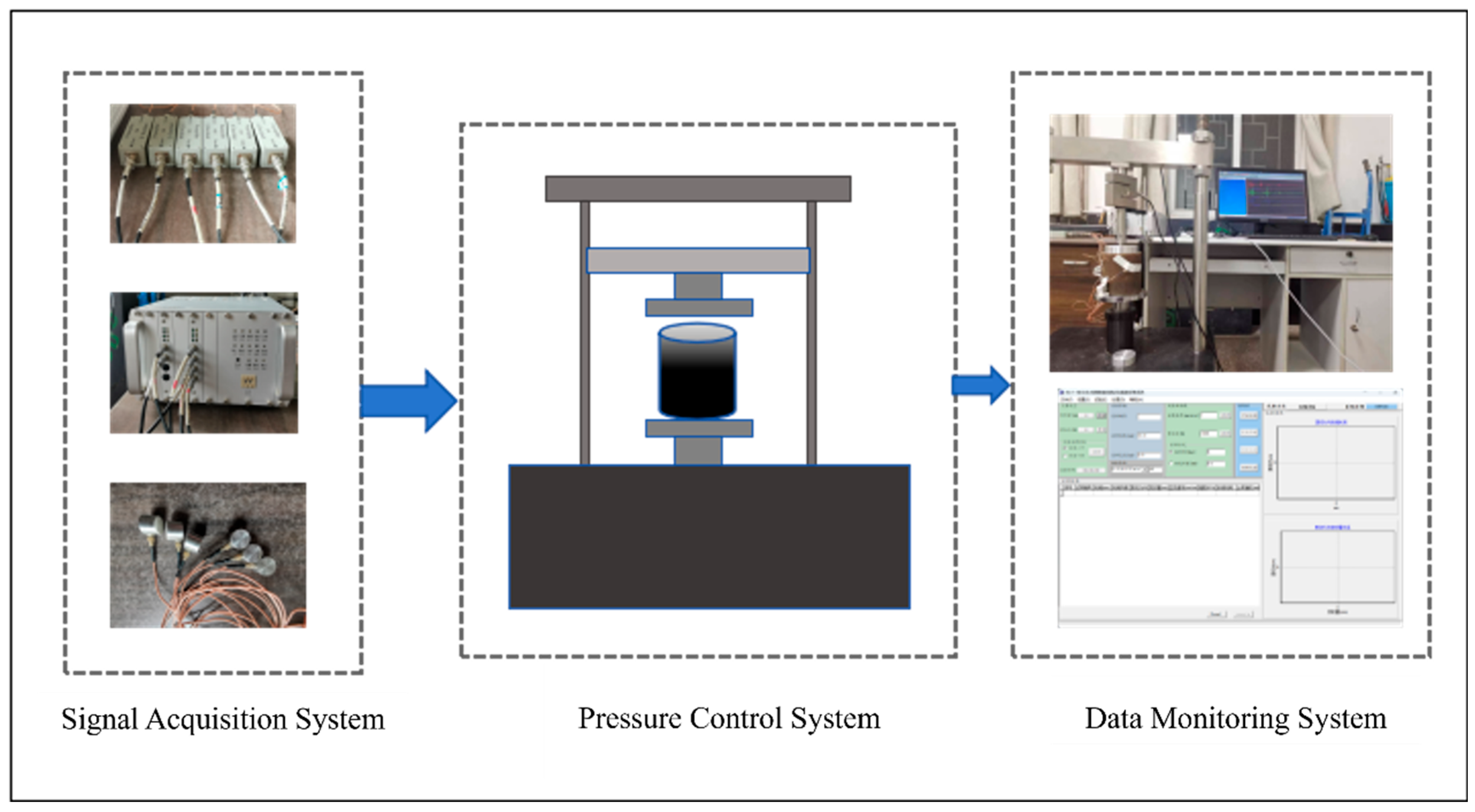

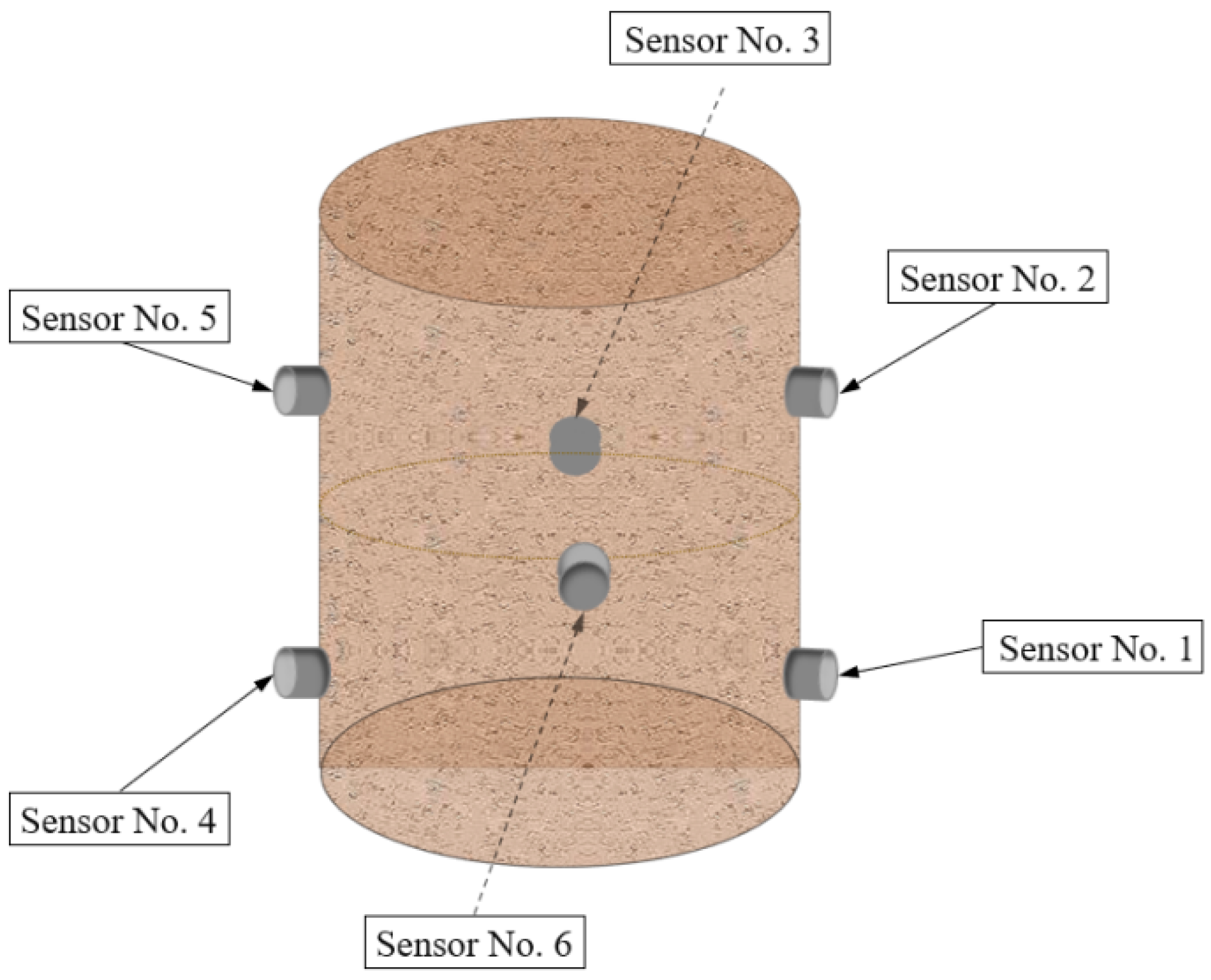

2.3. Experimental System

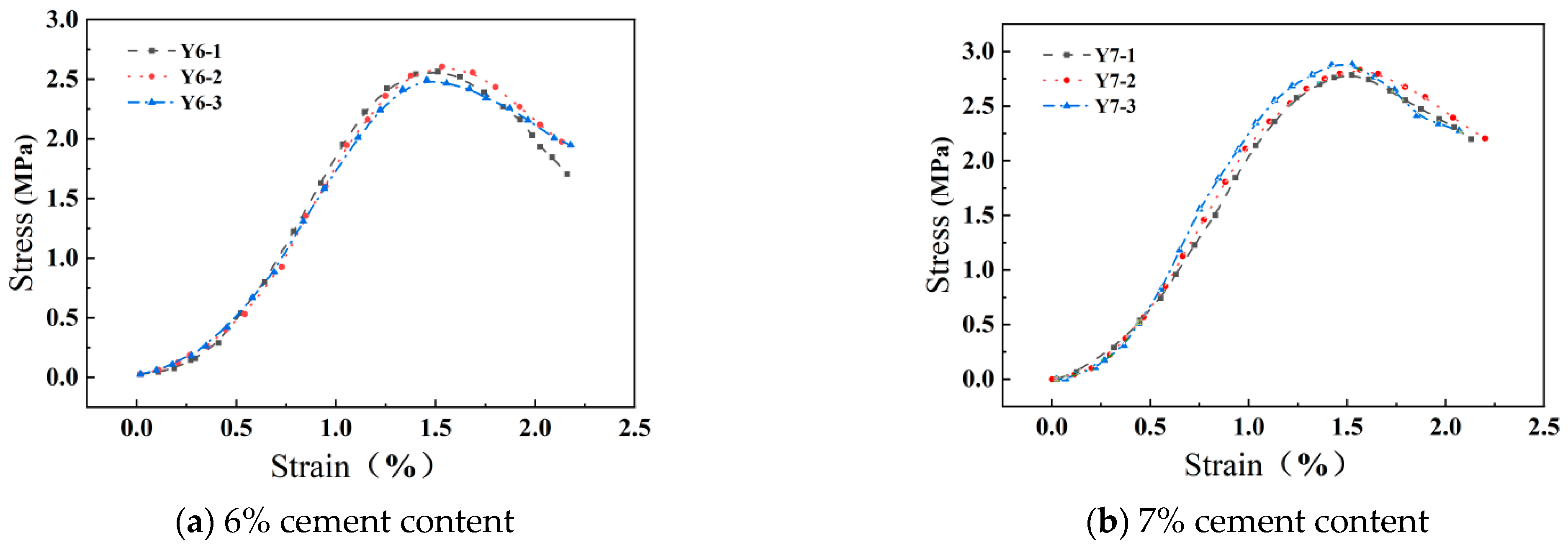

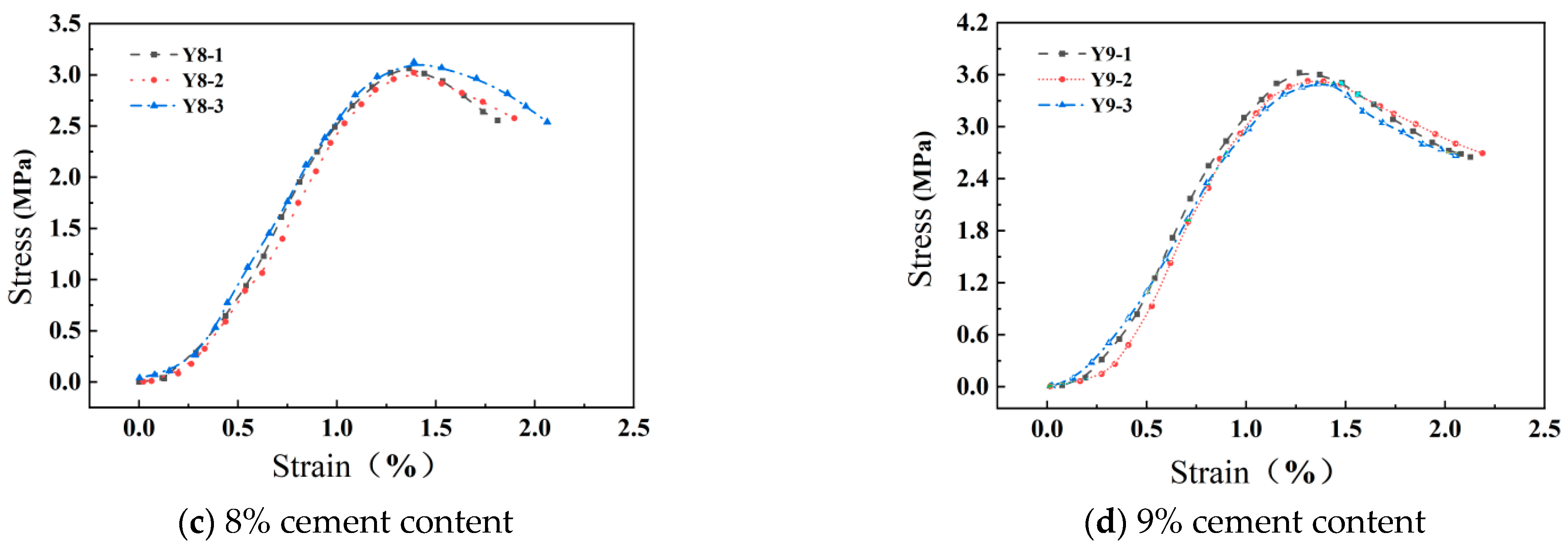

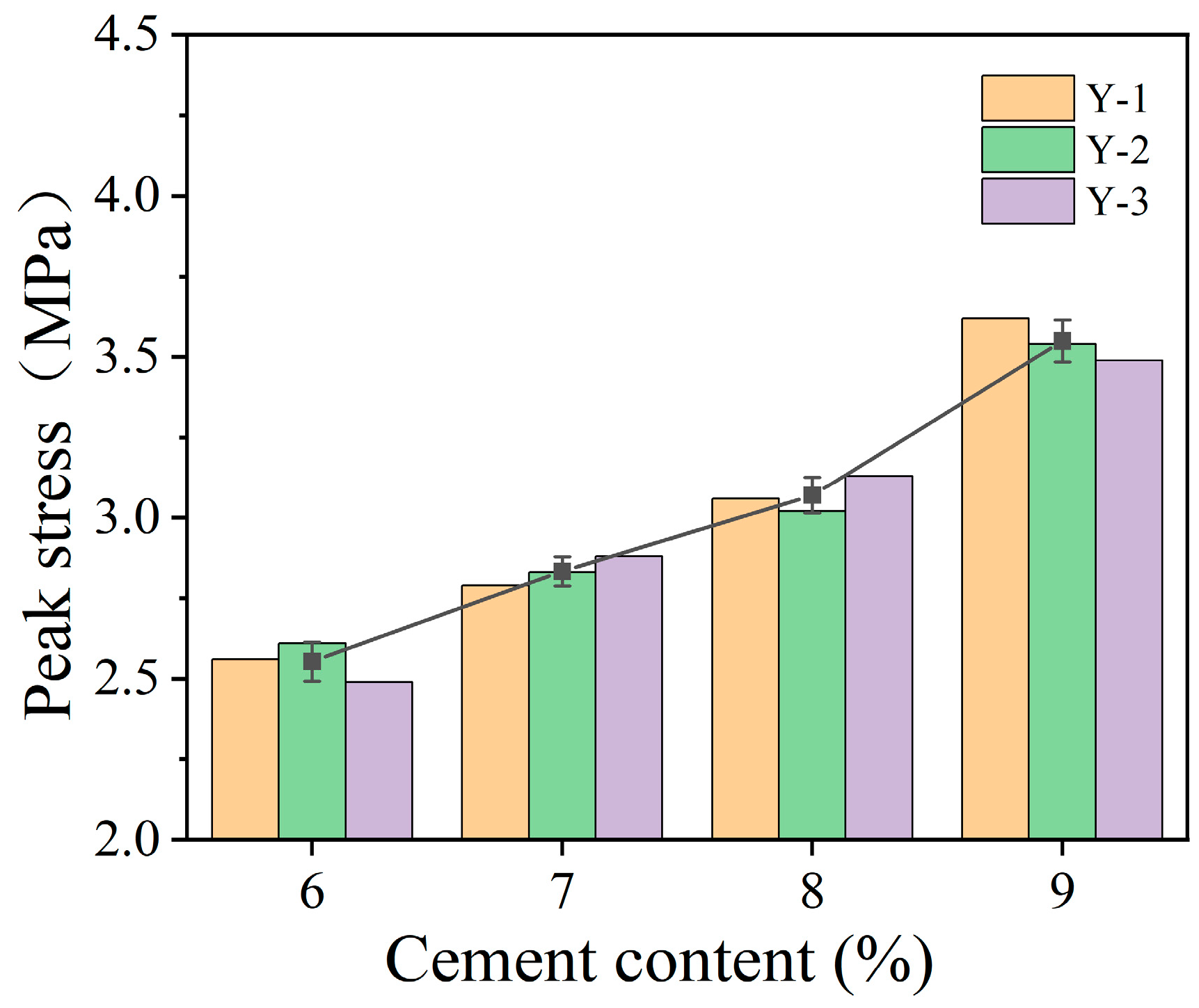

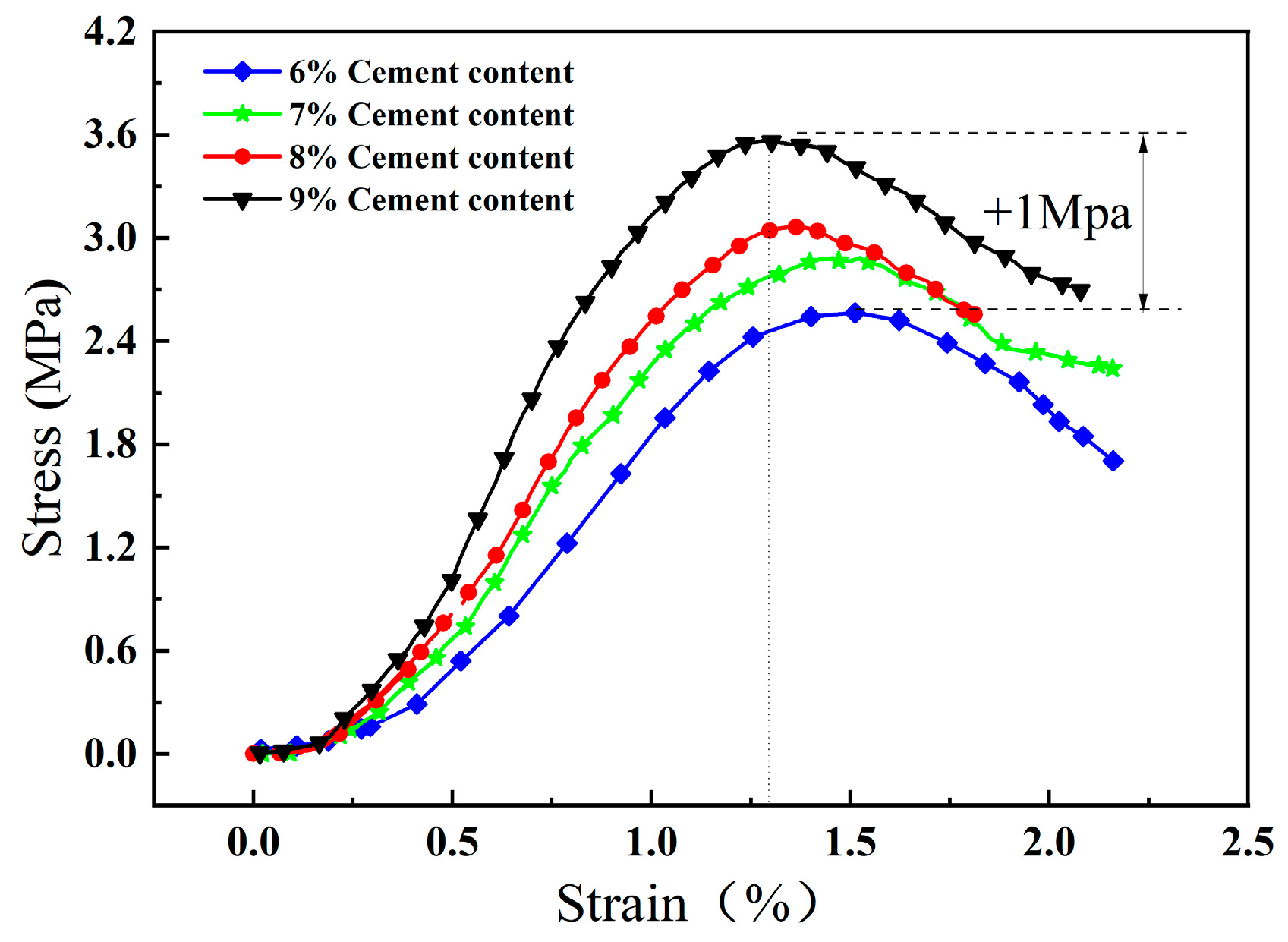

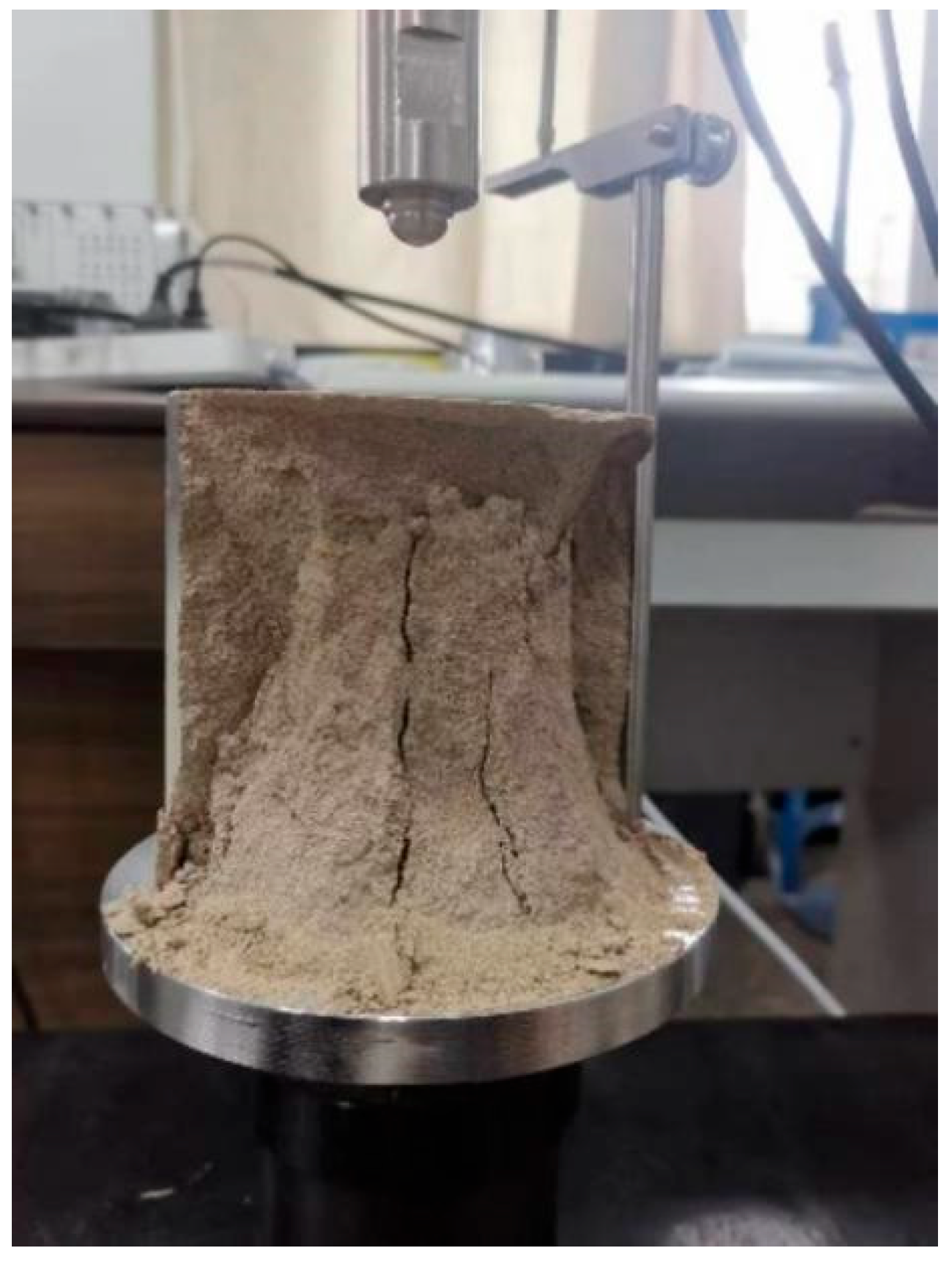

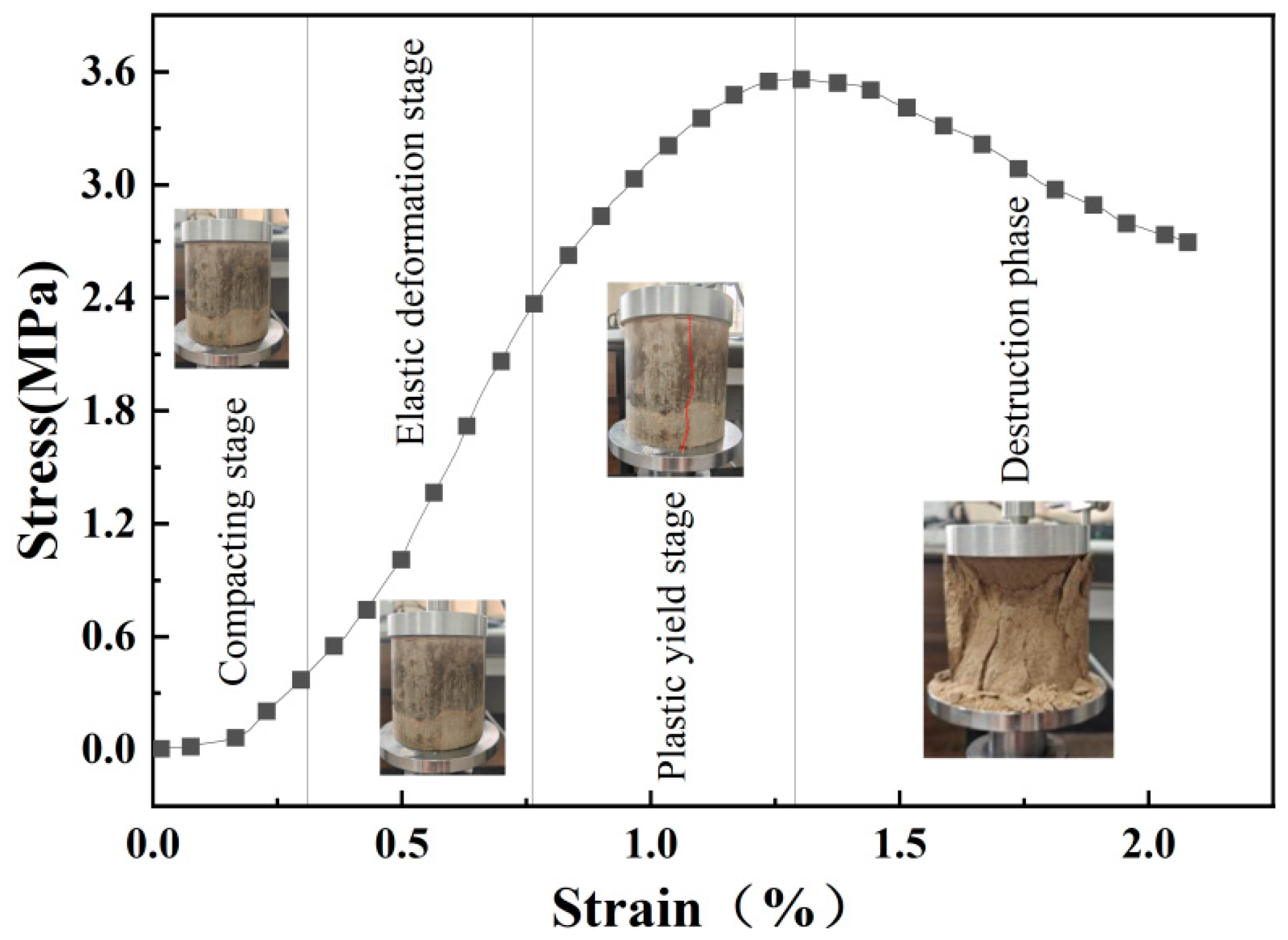

3. Mechanical Characterization

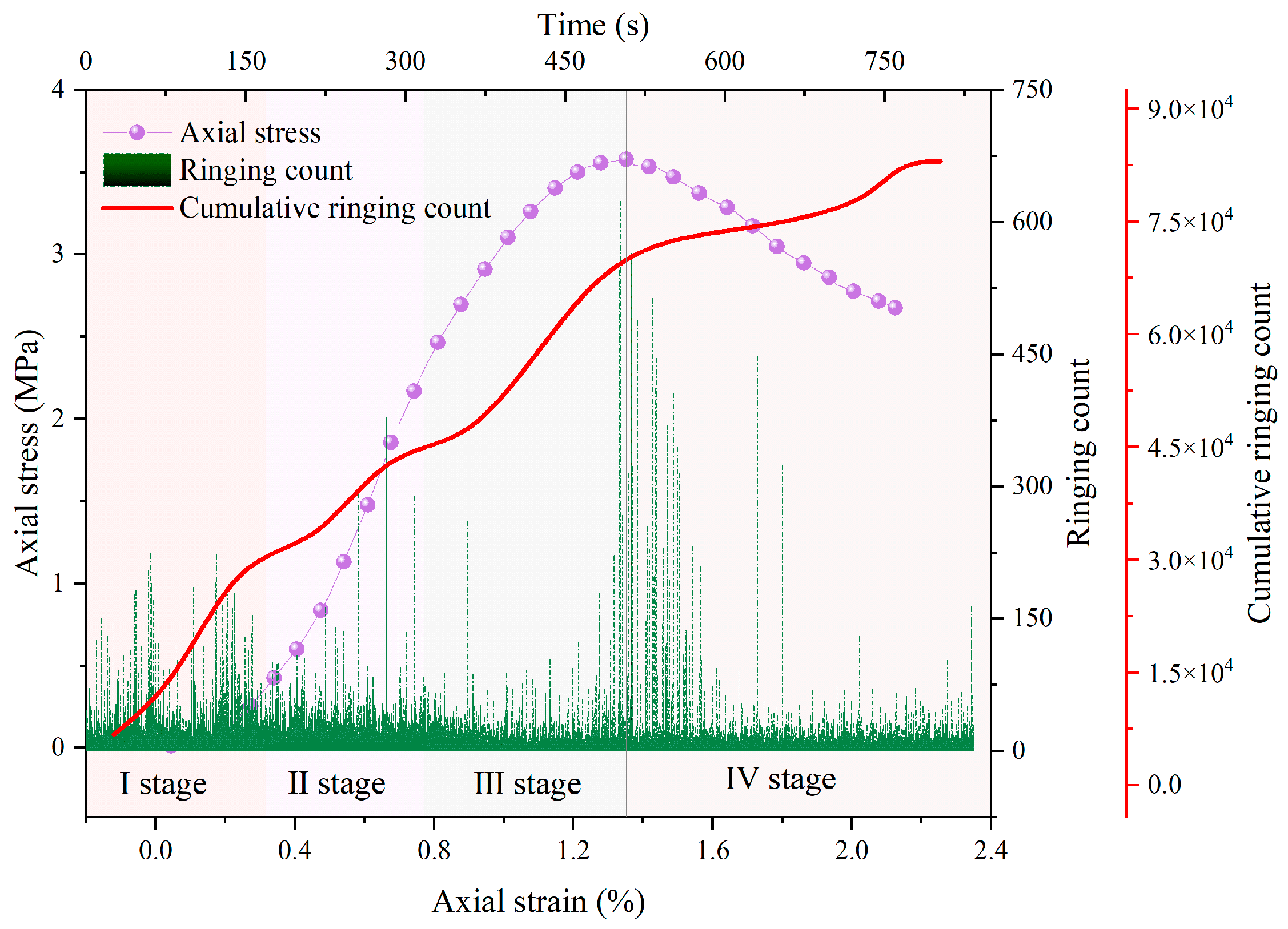

4. Characteristics of AE Signals During Deformation and Failure Process

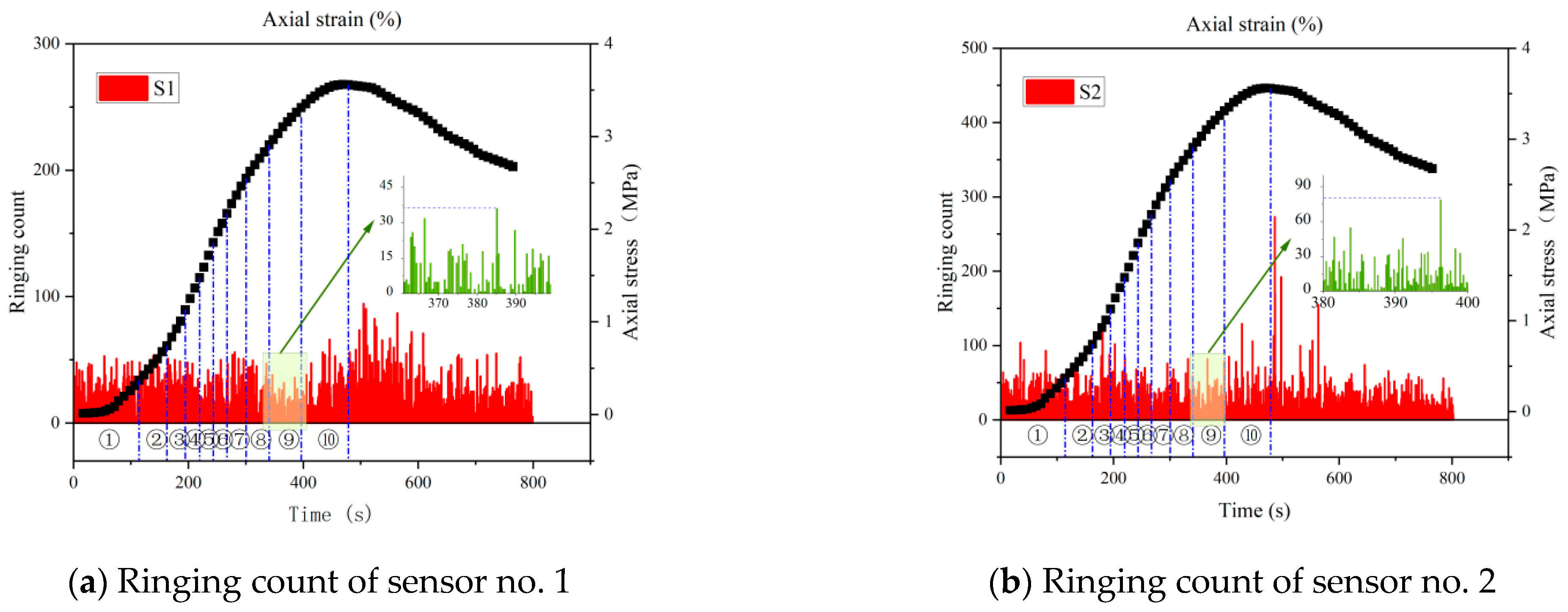

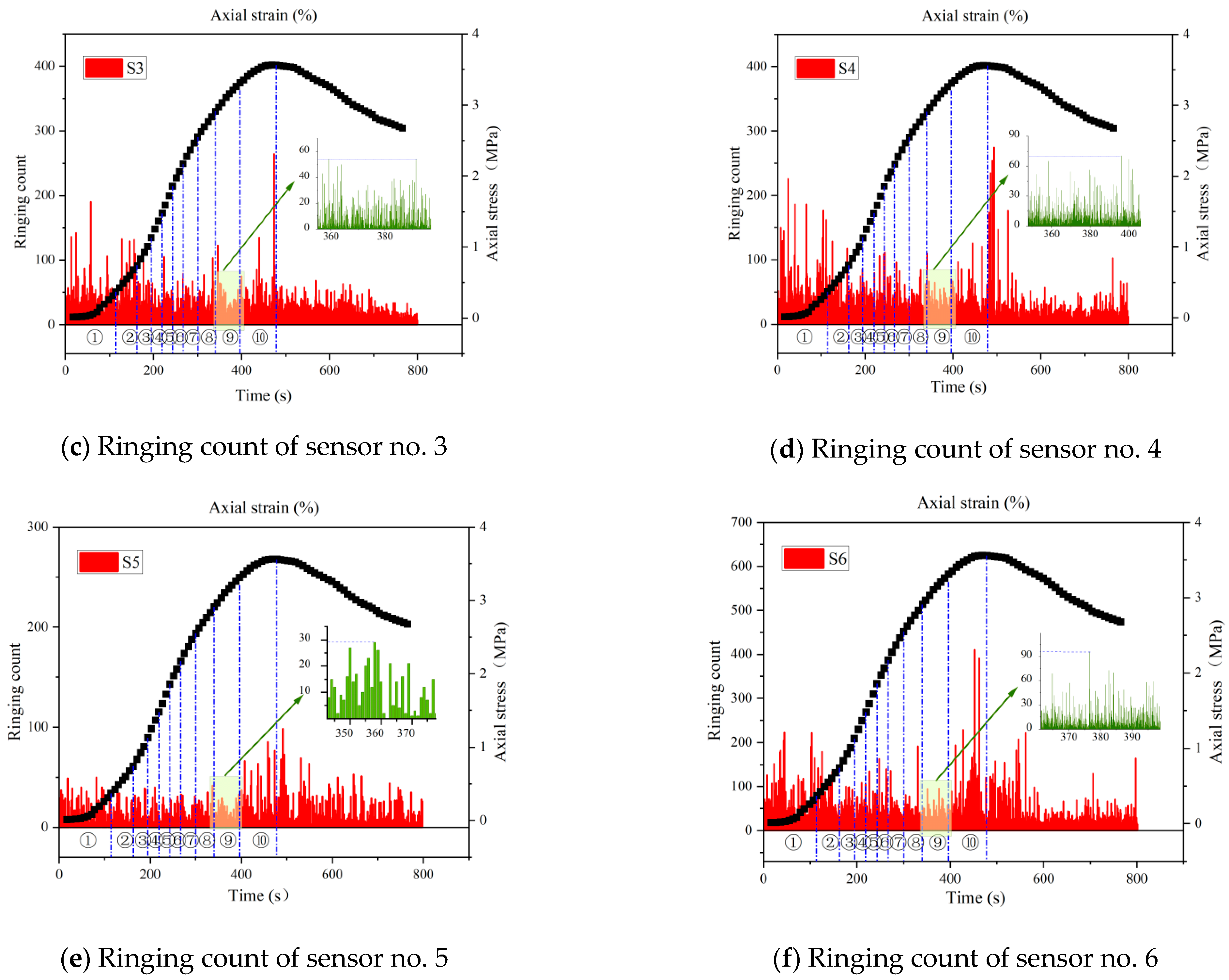

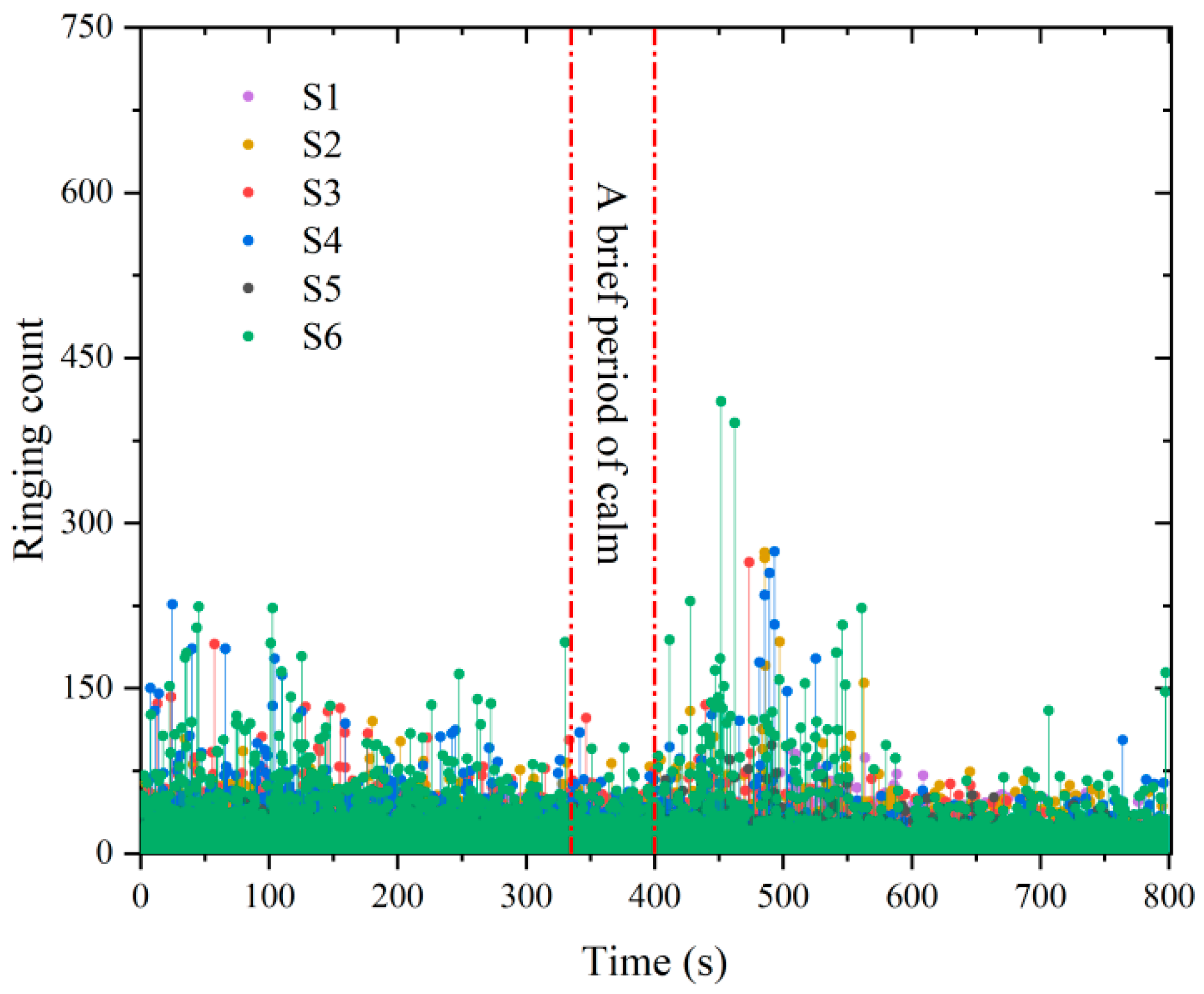

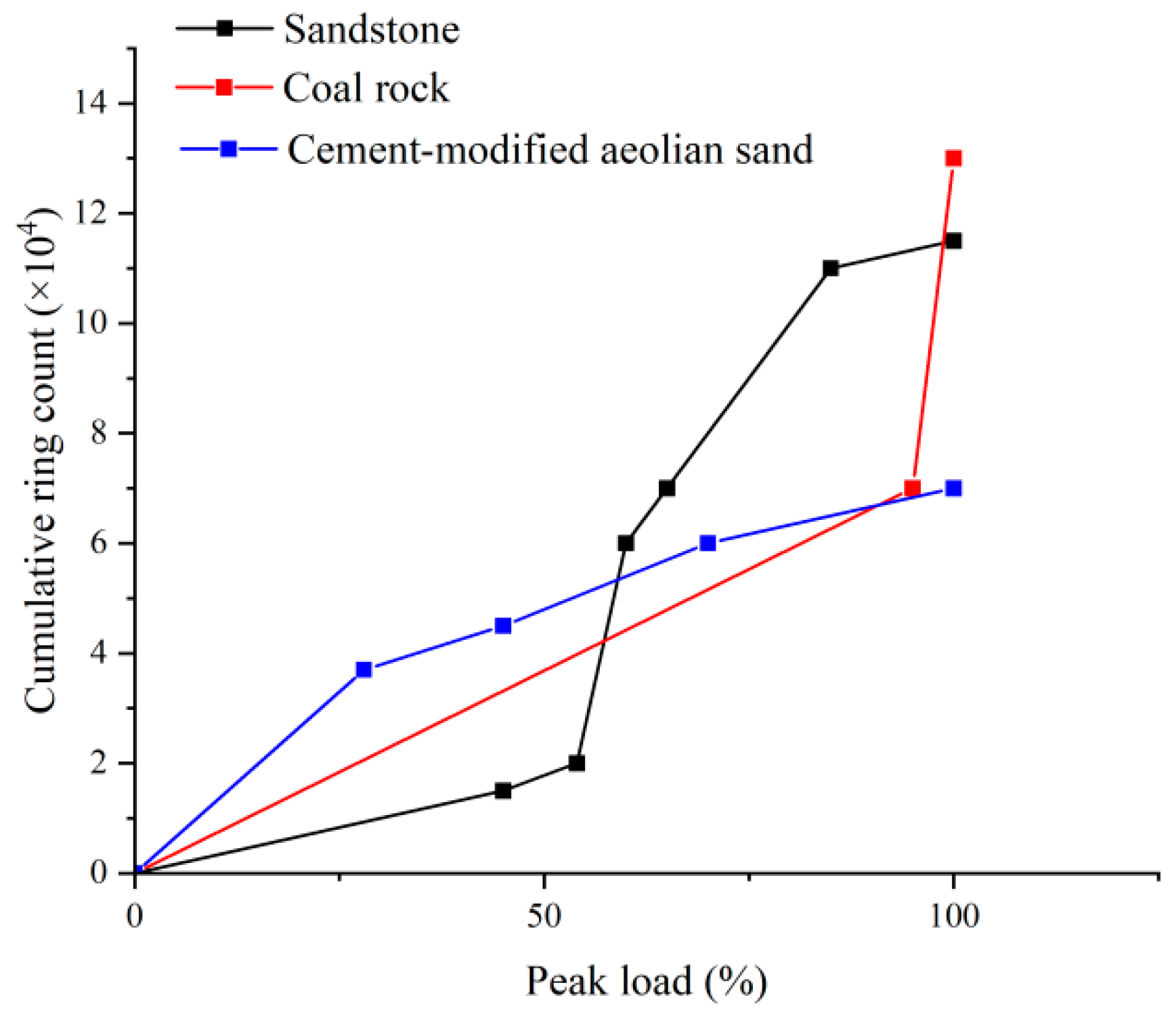

4.1. Ringing Count

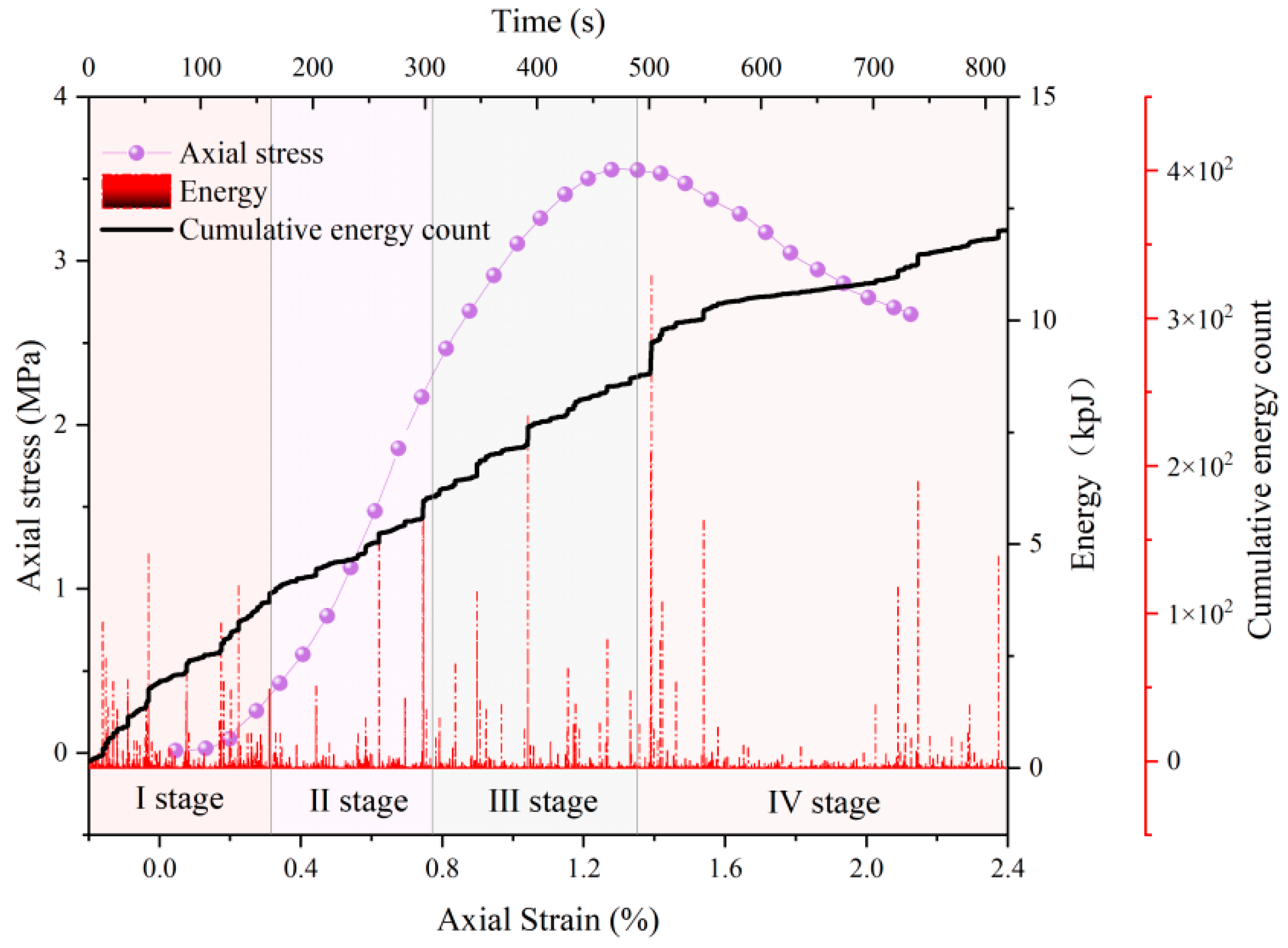

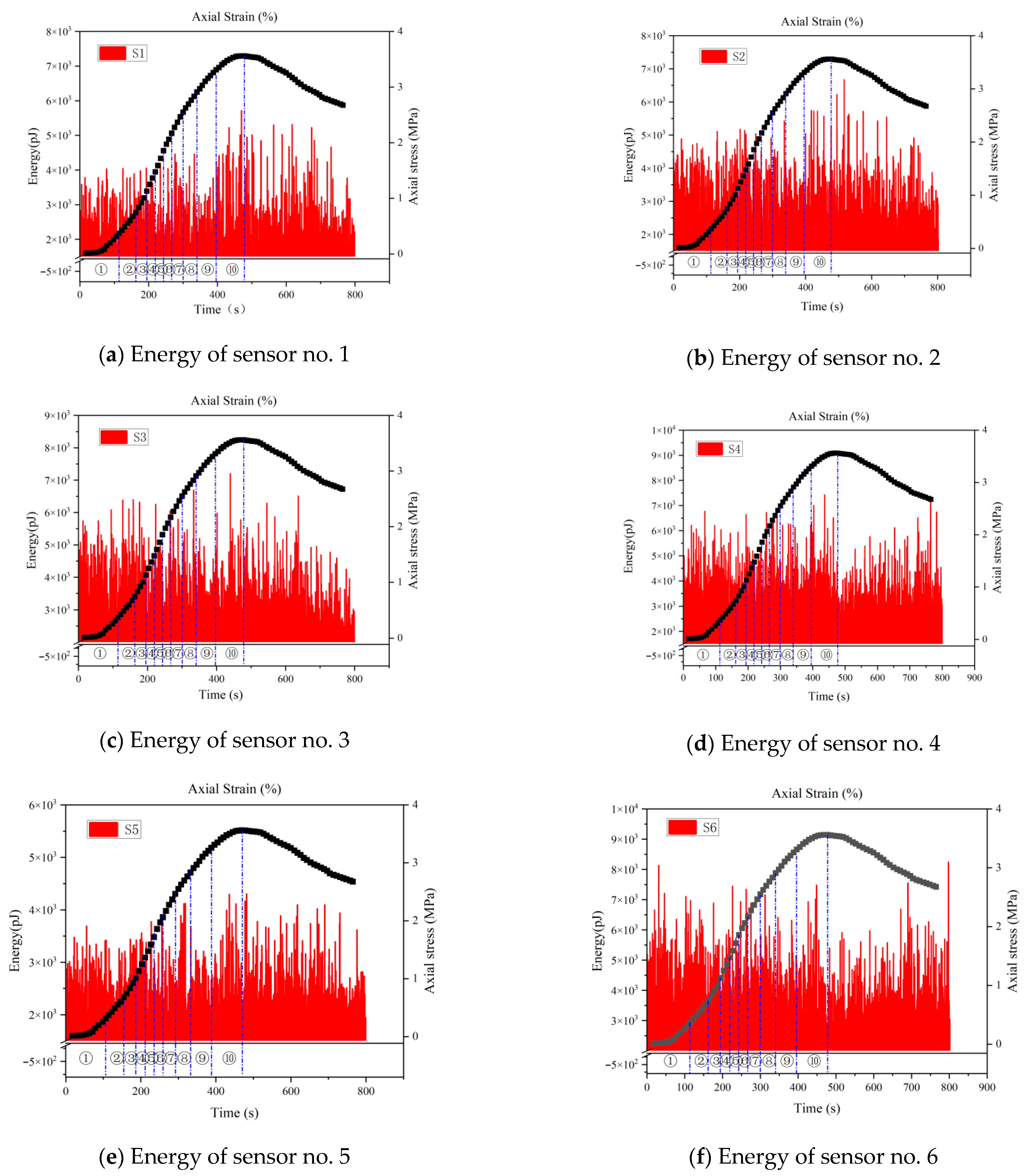

4.2. Energy

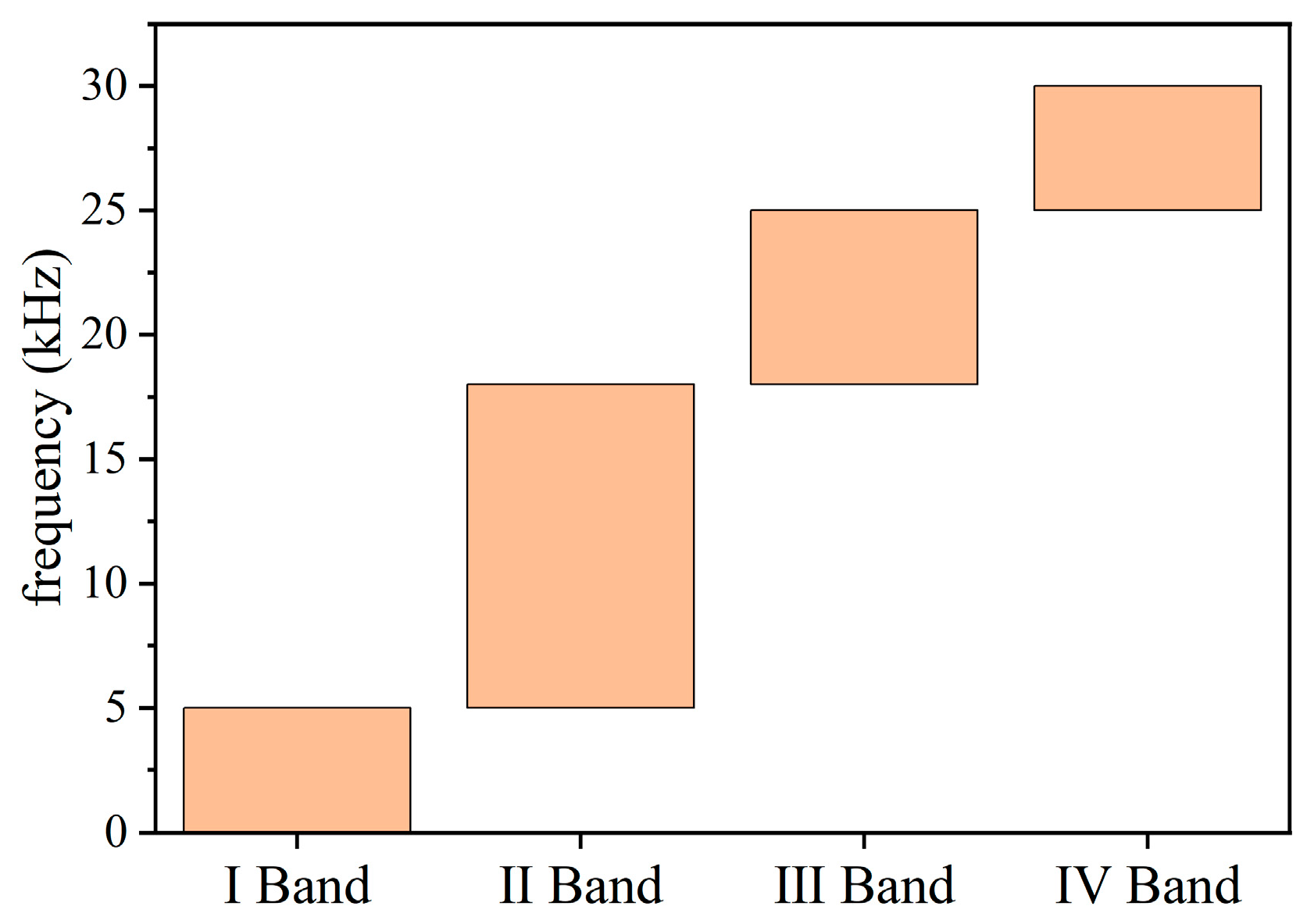

4.3. Frequency

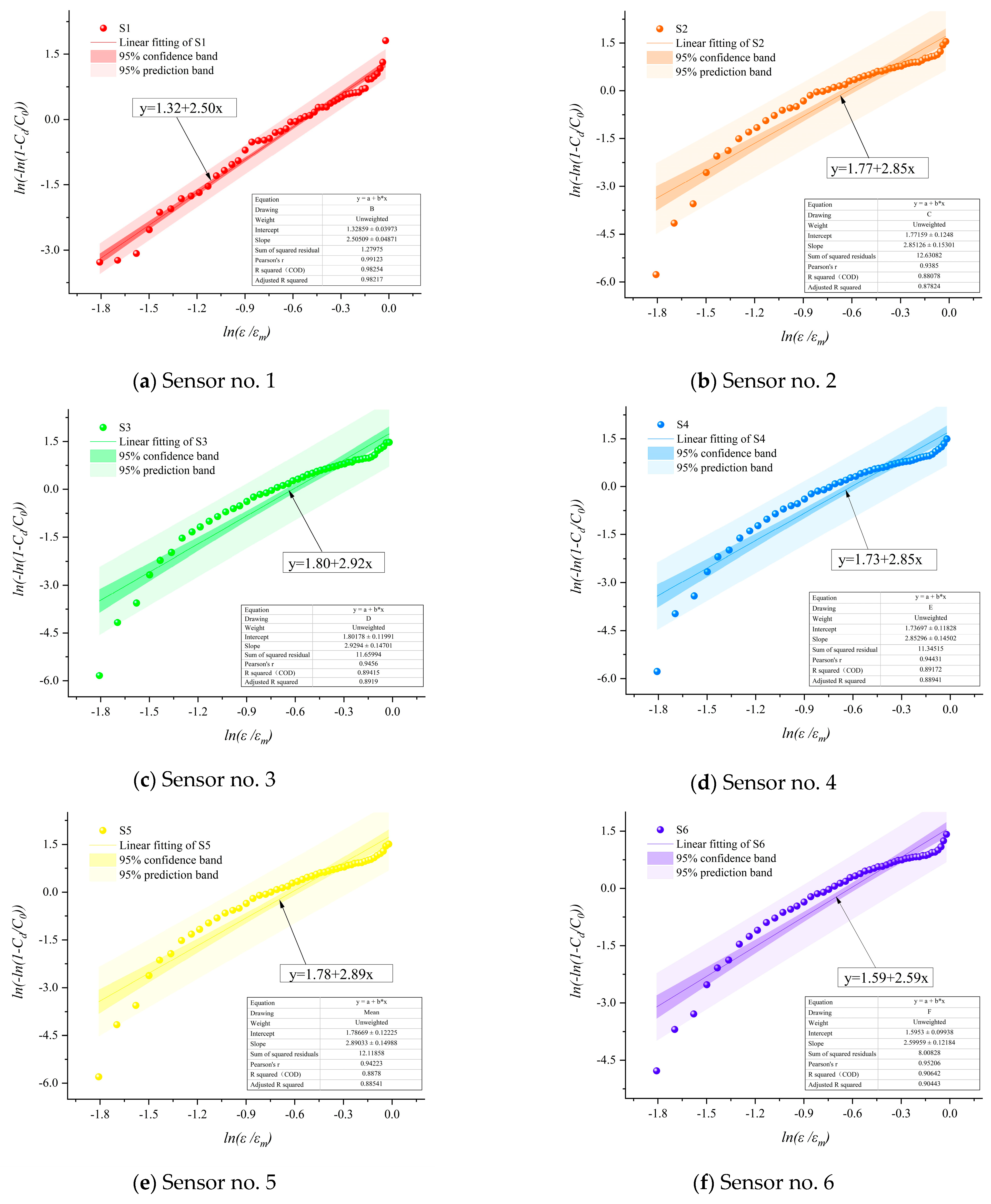

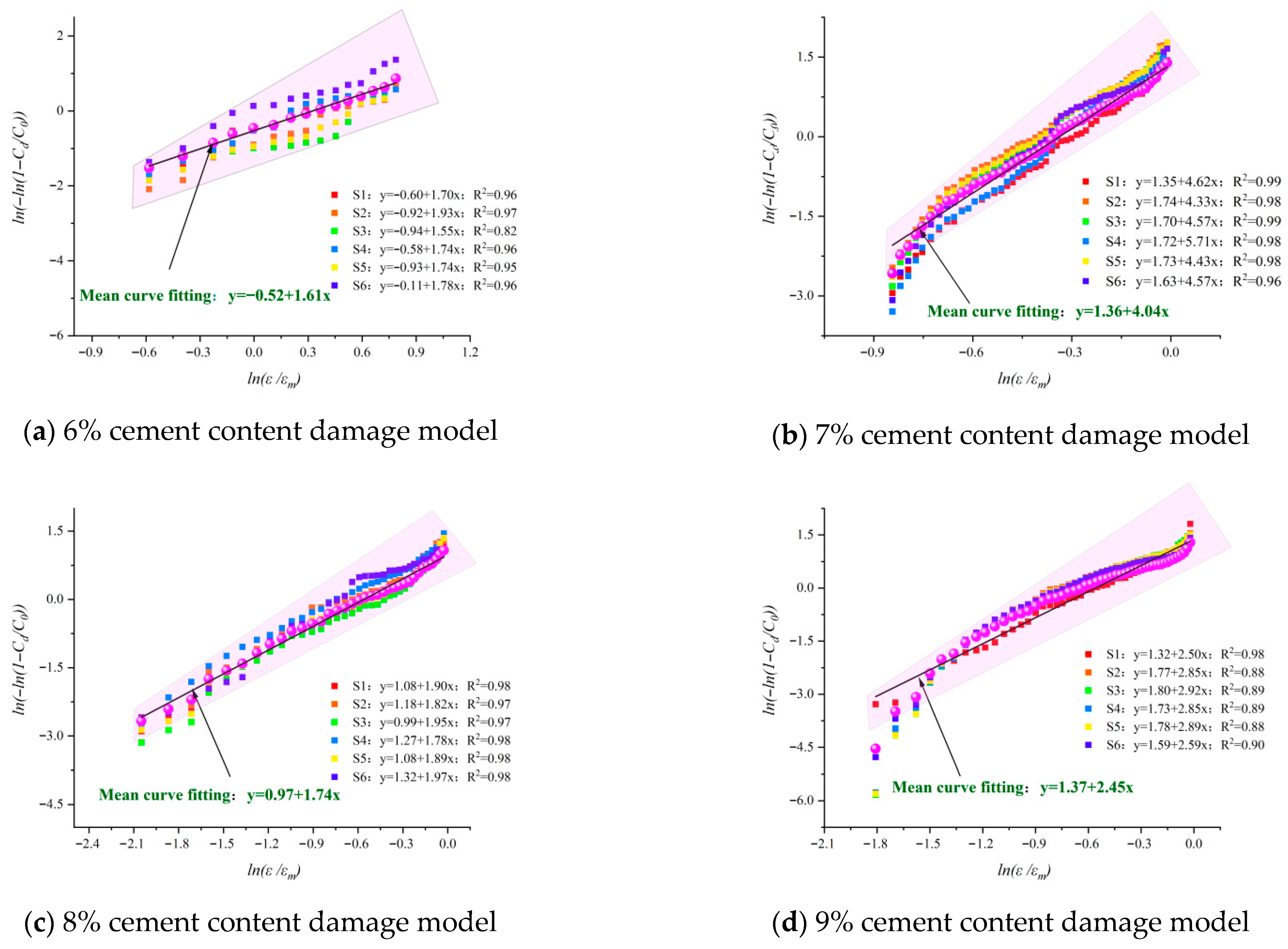

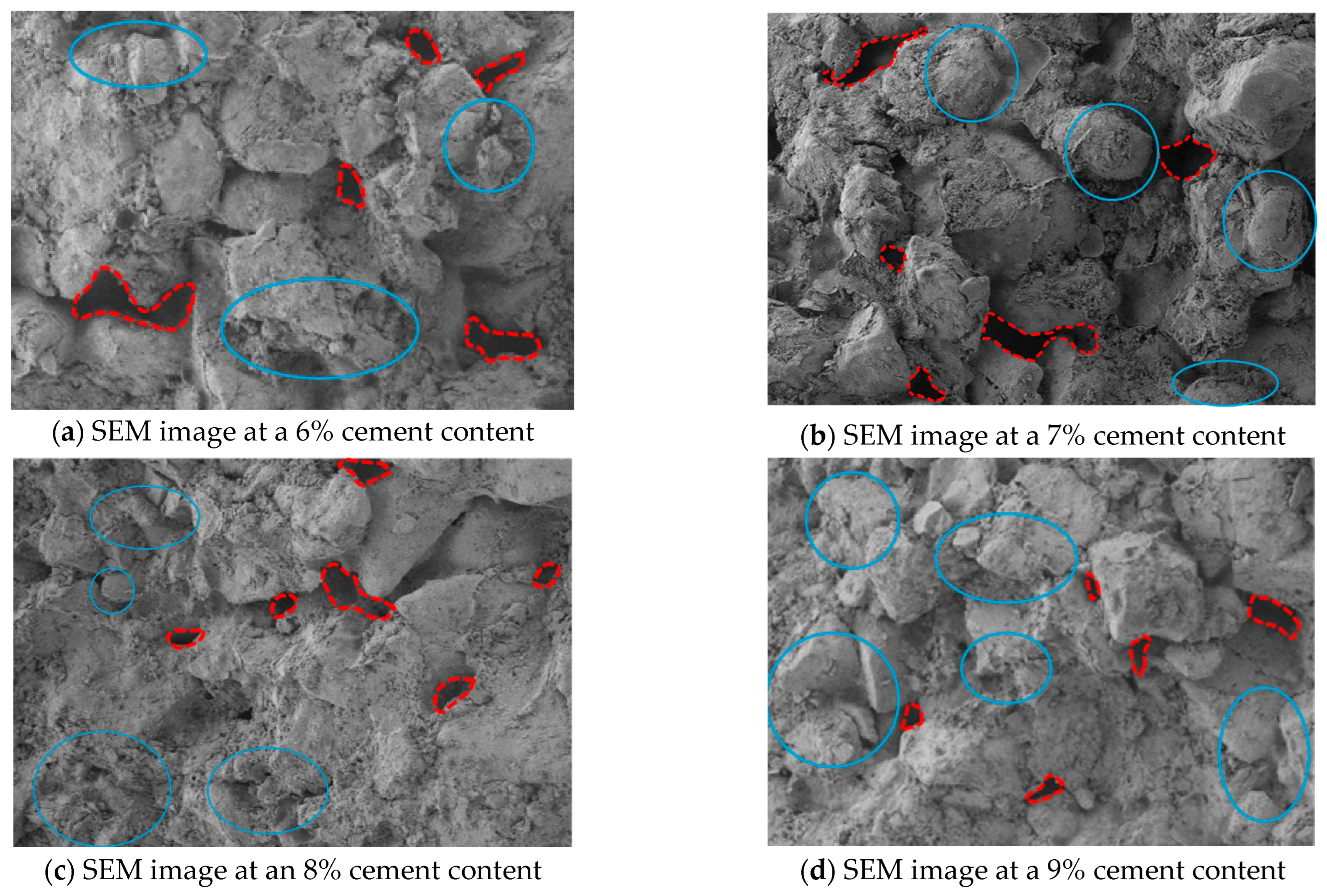

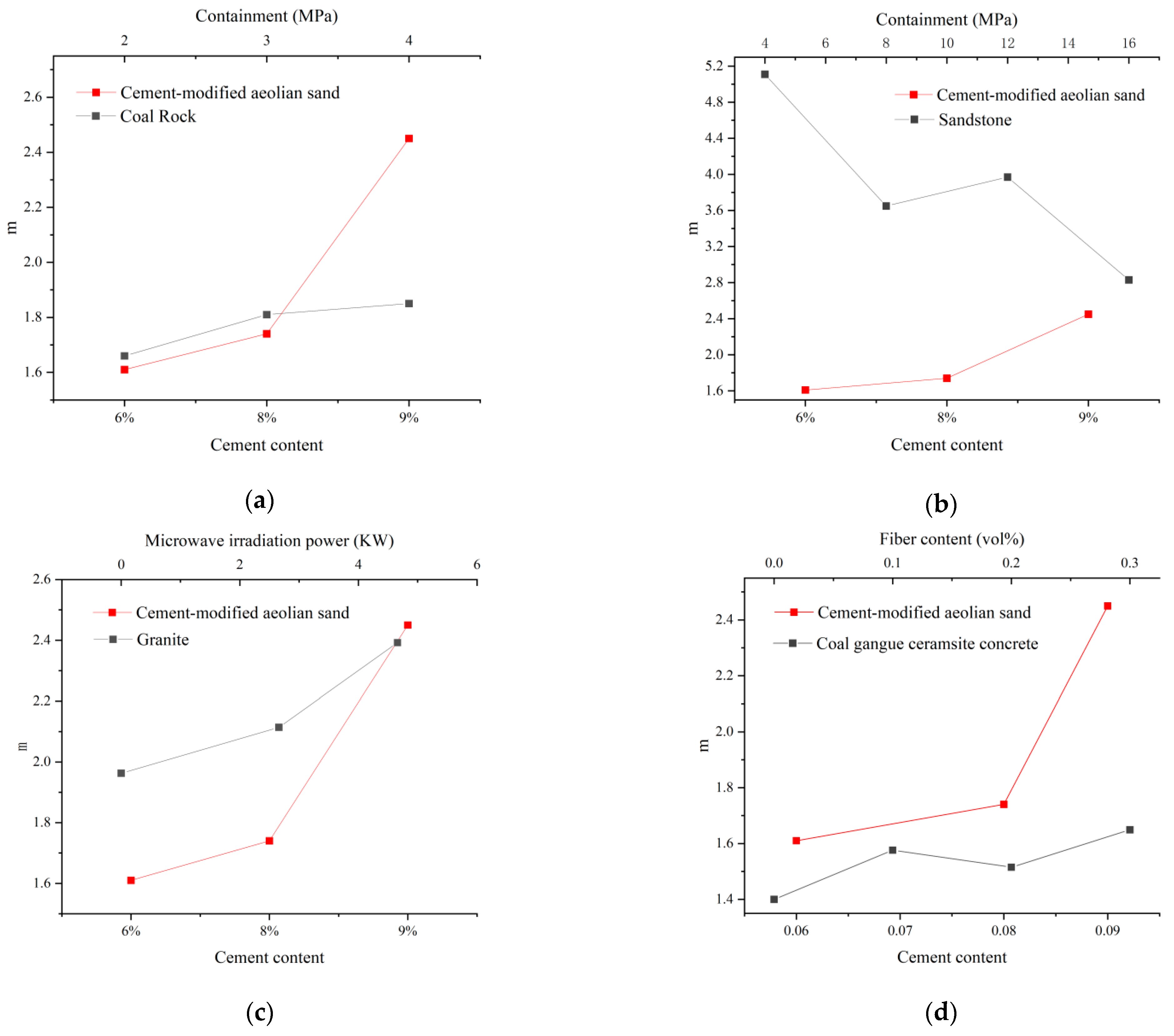

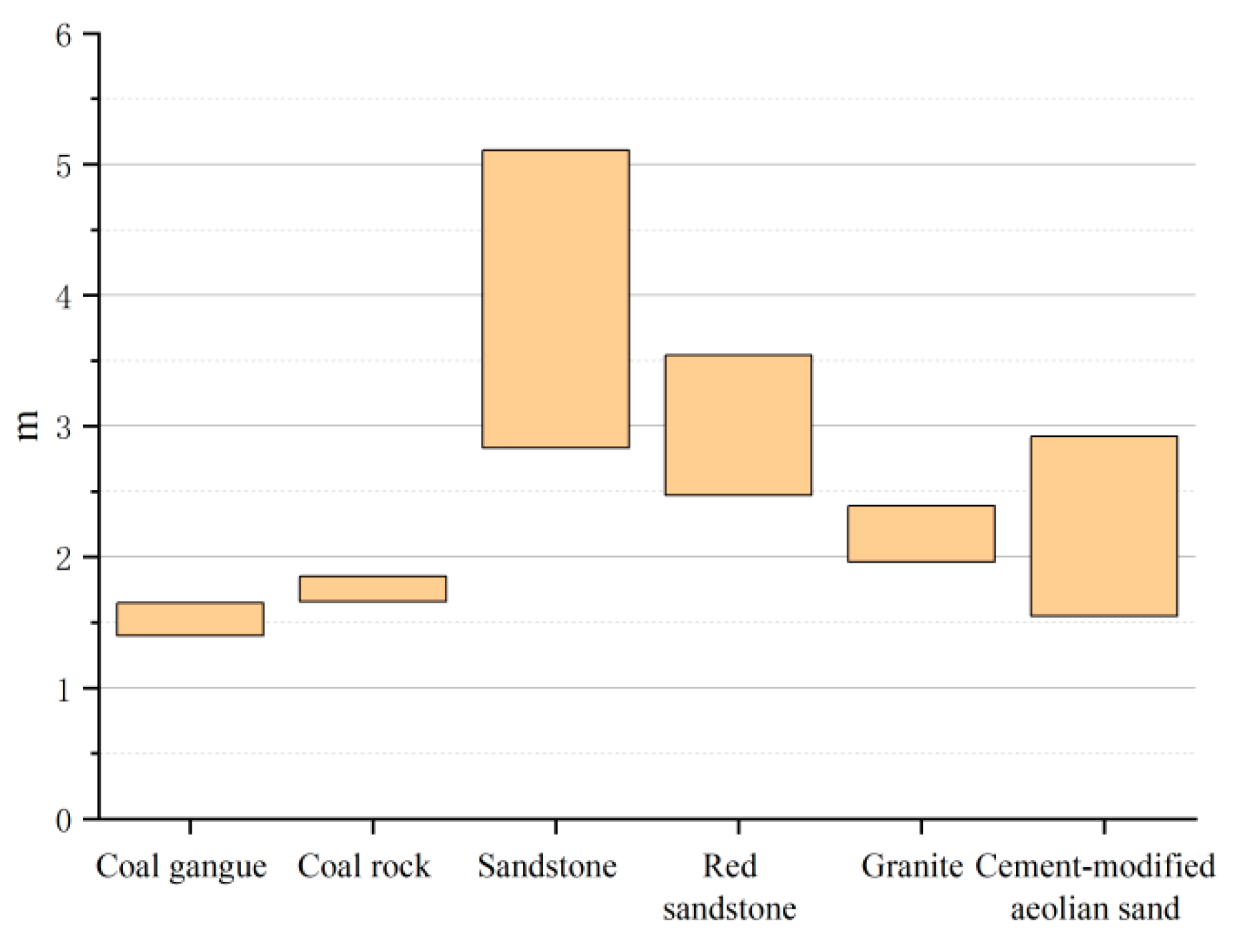

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- Cement-modified aeolian sand is a kind of granular material. However, both its stress–strain curve and acoustic emission characteristic parameters exhibit a deformation and failure process analogous to that of rocks, which are in four stages of compaction, elasticity, plastic deformation, and destruction. However, the AE characteristic parameter signals in the compaction stage are quite different from those of other materials, considering that the larger gaps between the sand particles lead to denser signals in compaction, which shows a larger difference.

- The ringing counts and energies increase with time and correspond to the different stages of stress. The cumulative ringing counts of the AE signal change abruptly when the axial stress of the specimen reaches the peak. When the stress reaches 80% of the peak stress, the acoustic emission signal becomes relatively calm. This phase of the ringing counts, and energy is low and relatively stable; the parameter changes can be used as warning precursor information in the application of cement-modified aeolian sand.

- The results of the damage model show that the damage of the cement-modified aeolian sand materials with different cement dosages obeyed the Weibull distribution. The material’s homogeneity transitions from being comparable to coal rock at lower cement contents to resembling granite at higher contents.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xue, H.J.; Shen, X.D.; Zou, C.X.; Liu, Q. Freeze-Thaw Pore Evolution of Aeolian Sand Concrete Based on Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. J. Build. Mater. 2019, 22, 199–205. [Google Scholar]

- He, R.; Han, D.J.; Li, L.L.; Li, R.; Hu, Y.Y. Research Progress on the Application of Aeolian Sand in Road Engineering. China J. Highw. Transp. 2025, 38, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.T.; Gong, H.K.; Xie, Y.L.; Yang, X.H. The Engineering Property of Aeolian Sand in Inner Mongolia. J. Hebei Univ. Technol. 2006, 35, 112. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Z.H. Research on Engineering Characteristics of Aeolian Sand and Physical Improvement Subgrade of Heavy Load Railway. Master’s Thesis, Lanzhou Jiao Tong University, Lanzhou, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.Y. Subgrade Performance and Application of PAM and Cement Composite Modified Wind-Blown Sand in Qinghai. Master’s Thesis, Southeast University, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, W.J.; Li, C.; Wu, H.M.; Gao, Y. Extraction of Potato Urease and Improvement of Aeolian Sand Based on EICP Technology. J. Civ. Environ. Eng. 2023, 45, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.D.; Li, J.; Sun, Q. Study of Dynamic Performance Under Negative Temperature and Rheology Characteristic for Cement Improved Aeolian Sand. Rock Soil Mech. 2018, 39, 4395–4403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, B.; Zheng, S.L.; Ding, H. Experimental Study on Unconfined Compressive Strength of Cement-Stabilized Aeolian Sand Cured at Low Temperature. J. Railw. Sci. Eng. 2020, 17, 2540–2548. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, B.; Zheng, S.L.; Ding, H. Experimental Research on the Unconfined Compressive Strength of Cement Improved Aeolian Sand Under High Temperature Curing Condition. J. Railw. Eng. Soc. 2021, 38, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, B.; Yuan, Z.Z.; Zheng, S.L. Experiment on the Splitting Tensile Strength of Cemented Aeolian Sand Reinforced with Different Kinds of Fibers. J. Railw. Sci. Eng. 2022, 19, 2240–2248. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, W.; Ruan, B.; Zheng, S.L. Experimental Study on Unconfined Compressive Strength of Cement-Improved Aeolian Sand Under Different Curing Temperature. J. Railw. Sci. Eng. 2021, 18, 678–686. [Google Scholar]

- Santoni, R.L.; Tingle, J.S.; Webster, S.L. Engineering Properties of Sand-Fiber Mixtures for Road Construction. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2001, 127, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Qian, Z.Z.; Yue, B.; Xie, Z.L. Effects of Cement Dosage, Curing Time, and Water Dosage on the Strength of Cement-Stabilized Aeolian Sand Based on Macroscopic and Microscopic Tests. Materials 2024, 17, 3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.D.; Geng, J.; Pang, S.; Su, L.J.; Cai, G.J.; Zhou, Z.C. Microscopic Properties and Splitting Tensile Strength of Fiber-Modified Cement-Stabilized Aeolian Sand. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2023, 35, 04023128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; Liu, G.; Zhang, Z.H.; Fang, Y.Q.; Gu, X.D. Experimental Investigation on the Strength and Microscopic Properties of Cement-Stabilized Aeolian Sand. Buildings 2023, 13, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seif, E. Assessing the engineering properties of concrete made with fine dunesands: An experimental study. Arab. J. Geosci. 2013, 6, 857–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.A.; Zheng, H.F.; Li, X.X.; Ye, W.J. Test on the mortar mix ratio with Aeoliansand of Mu Us desert. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 152–153, 892–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damene, Z.; Goual, M.; Houessou, J.; Dheilly, R.M. Quéneudec The use of southern Algeria dune sand in cellular lightweight concrete manufacturing: Effect of lime and aluminium content on porosity, compressive strength and thermal conductivity of elaborated materials. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2018, 22, 1273–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, B.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X.J.; Yuan, Z.Z.; Che, Y.F. The effects of different fiber lengths on the unconfined compressive strength and microstructure of cemented aeolian sand reinforced with hybrid fiber. J. Railw. Sci. Eng. 2024, 21, 5242–5251. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Li, Q.P.; Li, J.D.; Wang, Z.Q.; Lu, S.Q. Experimental Investigation on Mechanical and Acoustic Emission Characteristics of Gassy Coal under Different Stress Paths. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, L.Z.; Yuan, H.Y.; Chen, J.G.; Sun, Z.H.; Fu, M.; Wang, F.; Yan, S.; Li, K.Y.; Yu, M.M.; Chen, T. Correlation between Acoustic Emission Behaviour and Dynamics Model during Three-Stage Deformation Process of Soil Landslide. Sensors 2021, 21, 2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderloo, M.; Moosavi, M.; Ahmadi, M. Using Acoustic Emission Technique to Monitor Damage Progress around Joints in Brittle Materials. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2019, 104, 102368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirdesai, N.N.; Gupta, T.; Singh, T.N.; Ranjith, P.G. Studying the Acoustic Emission Response of an Indian Monumental Sandstone under Varying Temperatures and Strains. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 168, 346–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrea, M.; Jordi, D.; Miguel, H.; José, A. Acoustic Emission Monitoring of Mode I Fracture Toughness Tests on Sandstone Rocks. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 205, 108906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Wen, F.L.; Chen, W.; Liu, Z.F. Effect of Loading Rate on Acoustic Emission Characteristics and Microscopic Formation Mechanism Analysis for Sandstone. Energy Technol. Manag. 2025, 50, 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Li, E.B.; Duan, J.L.; Pu, S.K.; Tan, Y.H. Study on Acoustic Emission Characteristics and Damage Evolution Law of Beishan Granite Under Triaxial Compression. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2018, 37 (Suppl. S2), 4234–4244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Huang, G.; Wang, W.Z. Experimental Study of Acoustic Emission Characteristics of Coal Samples with Different Moisture Contents in Process of Compression Deformation and Failure. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2012, 31, 1115–1120. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Y.; Ranjith, P.G.; Chen, Y.; Cai, C.Z.; Gao, F.; Liu, X.G. Nonlinear Mechanical Characteristics and Damage Constitutive Model of Coal Under CO2 Adsorption During Geological Sequestration. Fuel 2023, 331 Pt 1, 125690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.L.; Chen, S.J.; Liu, S.M.; Li, Z.H. AE Waveform Characteristics of Rock Mass Under Uniaxial Loading Based on Hilbert-Huang Transform. J. Cent. South Univ. 2021, 28, 1843–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 175-2023; Common Portland Cement. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2023.

- TB 10102-2004; Code for Soil Test of Railway Engineering. China Railway Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2004.

- He, S.Q.; Qin, M.L.; Qiu, L.M.; Song, D.Z.; Zhang, X.F. Early Warning of Coal Dynamic Disaster by Precursor of AE and EMR “Quiet Period”. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2022, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Peng, W.H.; Liu, F.Y.; Zhang, H.X.; Li, Z.J. Monitoring Rock Failure Processes Using the Hilbert–Huang Transform of Acoustic Emission Signals. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2016, 49, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.Z.; Liu, J.W.; Liu, X.X.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, Y.B. Study on the Coupled Relationship between AE Accumulative Ring-down Count and Damage Constitutive Model of Rock. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 2015, 32, 28–34+41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.M.; Xing, T.Z.; Zhao, T.B.; Zhao, X.Z.; Gao, P.B. Acoustic Emission Characteristics of Deformation Field Development of Rock under Uniaxial Loading. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2017, 36, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.Y.; Zhang, Y.Z. Analysis on Acoustic Emission Characteristics of Coal under Uniaxial Compression. Coal Technol. 2021, 40, 129–132. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Z.Y.; Li, Z.Y.; Liu, E.Q. Study on Failure Characteristics and Acoustic Emission Parameters of Coal Rock under Uniaxial Loading. Mod. Min. 2024, 40, 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.Y.; Sui, Q.R.; You, R.; Han, T.Y.; Liu, C.C. Analysis of AE Time-Frequency Characteristics of Granite and Fine-Grained Granite. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2025, 21, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.; Wong, H.R.; Chau, K.; Tang, C. Microcrack statistics, Weibull distribution and micromechanical modeling of compressive failure in rock. Mech. Mater. 2005, 38, 664–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiang, H.N.; Jiang, A.N.; Yang, X.R. Statistical damage constitutive model of high temperature rock based on Weibulldistribution and its verification. Rock Soil Mech. 2021, 42, 1894–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.T.; Gao, W.H.; Zhang, Z.M.; Tang, X.Y.; Wu, J. Evolution of particle disintegration of red sandstone using Weibull distribution. Rock Soil Mech. 2020, 41, 877–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Wu, H.; Yin, S.; Xu, X. Study of Rock Damage Constitutive Model Considering Temperature Effect Based on Weibull Distribution. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.R.; Qin, S.Q.; Xue, L.; Yang, B.C.; Zhang, K. Characterization of Brittle Failure of Rock and Limitation of Weibull Distribution. Prog. Geophys. 2017, 32, 2200–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.H. Strain Rate Related Constitutive Models for Polymer and Cement Mortar Materials. Master’s Thesis, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, L.H.; Chen, J.K. Experimental Study on Constitutive Relation of Cement Mortar. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2007, 38, 217–220. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, L.A.P.; Gerke, K.M.; Munkholm, L.J.; Keller, T.; Gerke, H.H. Discrete element modeling of aggregate shape and internal structure effects on Weibull distribution of tensile strength. Soil Tillage Res. 2022, 219, 105341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, C.; Zou, J.; Wang, B.; Song, F.; Yang, W. DEM exploration of the effect of particle shape on particle breakage in granular assemblies. Comput. Geotech. 2020, 122, 103542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhu, X.P.; Zhang, P.F.; Li, H.; Guo, Q. Investigation on Freeze-Thaw Damage of Basalt Fiber Reinforced Coal Gangue Ceramsite Lightweight Concrete. Building Sci. 2024, 40, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, B.; Li, J.H. Study on Rock Damage Characteristics and Model Based on Energy Dissipation. Coal Technol. 2025, 44, 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.D.; Cai, J.Q.; Tang, N.N.; Li, Q.W.; Sun, C. Experimental Study on Mechanical Properties of Deep Sandstone and Its Constitutive Model. J. China Coal Soc. 2019, 44, 2087–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.J.; Xu, Z.Y.; Ma, Q.Q.; Wang, J.H.; Wu, Y.T. Experimental Study on the Damage Characteristics of Sandstone Under Freeze-Thaw Loading Coupling via the AE Method. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Ren, Y.P.; Yang, F. Damage Evolution Law and Constitutive Model of Granite under Microwave Irradiation. J. Hebei Univ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 42, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Wei, Z.A.; Xu, J.; Tang, X.J.; Yang, H.W. Experimental Research on the Acoustic Emission Characteristics of Rock under Uniaxial Compression. J. China Coal Soc. 2011, 36 (Suppl. S2), 237–240. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Li, X.C.; Xu, R.; Li, C.W.; Wang, Y.Q.; Liu, Y.F. Experimental investigation on time-frequency evolution characteristics of electromagnetic radiation below ULF reflecting the damage performance of coal or rock materials. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2021, 29, e2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.L.; Yin, X.G.; Wang, Y.J.; Tang, H.Y. Studies on Acoustic Emission Characteristics of Uniaxial Compressive Rock Failure. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2004, 23, 2499–2503. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, R.X.; Kong, Y.H.; Feng, J.X. Research on Different Rock Fracture Characteristics and Instability Precursor Information Based on Acoustic Emission. Coal Technol. 2024, 43, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Liu, X.H.; Hao, Q.J. Acoustic Emission Characteristics and Damage Evolution of Coal-Rock Under Different Confining Pressures. Coal Geol. Explor. 2020, 48, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.G.; Li, S.L. Study on Acoustic Emission Quietude-Omen Characteristic of Failure of Compressed Rock. Met. Mine 2008, 7, 124–128. [Google Scholar]

- Baud, P.; Wong, T.; Wei, Z. Effects of porosity and crack density on the compressive strength of rocks. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2014, 67, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schild, M.; Siegesmund, S.; Vollbrecht, A.; Mazurek, M. Characterization of granite matrix porosity and pore-space geometry by in situ and laboratory methods. Geophys. J. Int. 2001, 146, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, L.M.O.; del Río, L.M.S.; Calleja, L.; Ruiz de Argandoña, V.G.; Rodríguez Rey, A. Influence of microfractures and porosity on the physico-mechanical properties and weathering of ornamental granites. Eng. Geol. 2004, 77, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Yao, Y.; Liu, D.; Cai, Y.; Liu, Y. Characterizations of full-scale pore size distribution, porosity and permeability of coals: A novel methodology by nuclear magnetic resonance and fractal analysis theory. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2018, 196, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Chen, Z.; Yue, L.; Zhang, Y.; He, J.J.; Li, Y. Three-dimensional modeling and porosity calculation of coal rock pore structure. Appl. Geophys. 2022, 19, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Tang, D.; Xu, H.; Yang, Z.; Guo, L. Porosity and Permeability Models for Coals Using Low-Field Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Energy Fuels 2012, 26, 5005–5014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Plasticity Index | Organic Matter Content | Sulfate Content | Chloride Content | Water Content | Particle Density | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aeolian sand | 6.4 | 0.14% | 0.07% | 0.003% | 1.1% | |

| Silt | 7.3 | 0.19% | 0.09% | 0.005% | 12.3% |

| Specimen Number | Silt–Aeolian Sand | Cement Content (%) | Compaction Factor | Maintenance Period | Specimen Size (mm × mm) | Specimen Weight (g) | Optimal Moisture Content (%) | Unconfined Compressive Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y6-1 | 2:8 | 6 | 0.95 | 7 d | 100 × 101 | 1588 | 12 | 2.56 |

| Y6-2 | 6 | 100 × 101 | 1594 | 2.60 | ||||

| Y6-3 | 6 | 100 × 101 | 1589 | 2.52 | ||||

| Y7-1 | 7 | 100 × 100 | 1612 | 12.5 | 2.78 | |||

| Y7-2 | 7 | 100 × 101 | 1621 | 2.83 | ||||

| Y7-3 | 7 | 100 × 101 | 1619 | 2.88 | ||||

| Y8-1 | 8 | 100 × 101 | 1598 | 13 | 3.26 | |||

| Y8-2 | 8 | 100 × 101 | 1594 | 3.22 | ||||

| Y8-3 | 8 | 100 × 101 | 1602 | 3.13 | ||||

| Y9-1 | 9 | 100 × 100 | 1613 | 13.5 | 3.66 | |||

| Y9-2 | 9 | 100 × 101 | 1607 | 3.53 | ||||

| Y9-3 | 9 | 100 × 101 | 1614 | 3.54 |

| Sampling Frequency | Sample Length | Waveform Threshold | Parameter Thresholds | Preamplifier Gain | Interval Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 769 kHZ | 2048 | 40 dB | 40 dB | 40 dB | 50 |

| Deformation Failure Stage | I Band | II Band | III Band | IV Band |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compaction Stage | 14.1% | 27.0% | 49.1% | 9.8% |

| Linear Elasticity Stage | 15.7% | 24% | 48.5% | 11.8% |

| Plastic Deformation Stage | 19.6% | 23.7% | 42.5% | 14.2% |

| Instability Failure Stage | 21.2% | 23.1% | 41.4% | 14.3% |

| Material | Test Method | Compressive Strength | Quiet Period | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Granite | Uniaxial compression test | 60 MPa | 75% | Research on Different Rock Fracture Characteristics and Instability Precursor Information Based on Acoustic Emission |

| Uniaxial compression test | 96 MPa | 85–90% | Studies on acoustic emission characteristics of uniaxial compressive rock failure | |

| Uniaxial compression test | 130 MPa | 71% | Study on the Acoustic Emission Characteristics of Granite in Relative Calm Period Based on GBM Model of Particle Flow Code | |

| Sandstone | Uniaxial compression test | 49 MPa | 76% | Research on Different Rock Fracture Characteristics and Instability Precursor Information Based on Acoustic Emission |

| Uniaxial compression test | 51 MPa | 74% | Deformation, failure, and crack propagation characteristics of fissured red sandstone under uniaxial compression condition | |

| Coal Rock | Circumference compression test | 64 MPa | 95–98% | Acoustic emission characteristics and damage evolution of coal-rock under different confining pressures |

| Uniaxial compression test | 20 MPa | 90.5% | Precursory characteristics of coal-rock failure using AE and computed tomography under uniaxial monotonic and cyclic compression |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, W.; Liu, M.; Yuan, G.; Zheng, S.; Wei, L.; Chang, P.; Yang, W. Acoustic Emission Characteristic Parameters and Damage Model of Cement-Modified Aeolian Sand Compression Failure. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11860. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211860

Zhang W, Liu M, Yuan G, Zheng S, Wei L, Chang P, Yang W. Acoustic Emission Characteristic Parameters and Damage Model of Cement-Modified Aeolian Sand Compression Failure. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(22):11860. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211860

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Wenge, Ming Liu, Guangying Yuan, Suya Zheng, Linhuan Wei, Panpan Chang, and Wei Yang. 2025. "Acoustic Emission Characteristic Parameters and Damage Model of Cement-Modified Aeolian Sand Compression Failure" Applied Sciences 15, no. 22: 11860. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211860

APA StyleZhang, W., Liu, M., Yuan, G., Zheng, S., Wei, L., Chang, P., & Yang, W. (2025). Acoustic Emission Characteristic Parameters and Damage Model of Cement-Modified Aeolian Sand Compression Failure. Applied Sciences, 15(22), 11860. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211860