1. Introduction

Fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas have long been the primary global energy source. The intensive consumption of these has contributed to the worldwide energy crisis and to serious environmental problems, including the emission of greenhouse gases and the destruction of the ecosystem [

1]. As economic and social development advances, the increasing demand for energy has made finding sustainable alternative energy sources increasingly necessary. Wind energy has increasingly drawn global interest as a clean, reliable alternative that can help satisfy the world’s rising energy requirements [

2,

3]. Wind turbines have been widely adopted in this transformation, and their use has become significantly widespread globally [

4].

The rapid expansion of the wind energy sector has underscored the importance of efficient operation and maintenance strategies to ensure the long-term reliability of turbine blades [

5]. Blade damage remains among the most common and costly causes of turbine downtime, often leading to significant power losses and maintenance expenses [

6,

7]. In severe cases, structural failures can even result in safety hazards for maintenance personnel and surrounding areas [

8]. Field reports indicate that repair or replacement of damaged blades may account for approximately 15–30% of total operational costs in a typical wind farm [

7,

9]. Since the blades are the primary components responsible for energy conversion efficiency [

10], their exposure to harsh environmental conditions, such as high winds, temperature fluctuations, and airborne particulates, gradually accelerates surface degradation, erosion, and cracking [

1,

11]. These effects cumulatively reduce aerodynamic performance and shorten the operational lifespan of wind turbines, emphasizing the necessity for reliable, non-destructive inspection (NDT) and monitoring techniques [

12].

Among the various degradation modes observed, wind turbine blades (WTBs) typically experience surface erosion, minor cracks, corrosion spots, or trailing edge splits [

7,

13]. Such defects can manifest at multiple locations across the blade, from the leading edge to the root section, and often compromise critical internal components including the spar cap and shear web [

13,

14]. Various NDT techniques have been employed for fault detection, including thermal imaging, X-ray inspection, vision-based systems, laser shearography, and microwave testing [

15]. While these methods demonstrate adequate performance for surface-visible damage, they frequently fail to detect subtle aerodynamic alterations that emerge prior to significant structural deterioration.

Out of the many NDT techniques available, thermography tends to draw more attention because it works well for spotting faults, and that strength comes from simple aerodynamic effects [

16,

17]. When the blade surface develops small flaws, such as areas of roughness, pitting, or hairline cracks, the smooth airflow over it gets slightly disturbed, creating pockets of turbulence [

18]. That disturbed air raises local stress on the surface and pushes more heat through by convection, so small but noticeable shifts in surface temperature start to appear [

19,

20]. These temperature patterns, often called thermal turbulence patterns (TTPs), show up in infrared scans as irregular warm streaks or faint contours that stretch in the same direction as the airflow [

21]. TTPs serve as early thermal indicators of structural deterioration, enabling the detection of defects that are unobservable by traditional inspection methods. By identifying these hidden anomalies early, preventive maintenance can be performed before serious damage to WTBs occurs. However, analyses based solely on the examination of TTPs may not always establish a definitive correlation with structural defects, as environmental conditions, surface emissivity variations, solar heating, convective cooling, and background thermal noise can distort or mask these thermal signatures [

18]. As a result, numerous studies have suggested enhancing thermographic analysis by combining it with advanced image processing techniques or with machine learning and deep learning (DL) models, enabling more reliable differentiation between genuine TTPs and false detections [

22,

23,

24].

Traditional fault detection in wind turbines primarily relied on manual inspection and sensor-based monitoring systems [

1,

4]. Although effective in limited scopes, these approaches were labor-intensive, weather-dependent, and often insufficient for detecting early-stage surface degradation, motivating the shift toward automated, vision-based inspection. In recent years, the shift toward DL-based automated inspection has mirrored broader developments in object detection research. The field is currently dominated by two principal architectural paradigms: convolutional neural network (CNN)-based detectors and transformer-based models. Each offers distinct advantages. CNN-based models, such as the YOLO series, are widely recognized for their computational efficiency and strong inductive biases, making them particularly suitable for real-time applications [

25]. In contrast, transformer-based models, exemplified by DETR and its real-time variant RT-DETR, employ self-attention mechanisms to capture long-range dependencies and global context, albeit often at the cost of increased computational demand [

26]. Within the specific context of WTB inspection, research has predominantly progressed along CNN-based architectures, particularly the YOLO family, with a clear emphasis on improving the detection of small-scale defects through advanced attention mechanisms and feature-fusion strategies. For instance, Zhang et al. (2022) enhanced feature representation by incorporating attention modules into a MobileNetv1–YOLOv4 framework [

5]. Similarly, subsequent works by Qingze et al. (2024) and Yu et al. (2024) investigated coordinate attention and CBAM mechanisms, respectively, to achieve higher detection precision [

3,

27]. Moreover, multi-scale feature fusion has been further refined through architectures such as Ma et al.’s SBiFPN [

1] and Yu et al.’s weighted BiFPN [

3], both designed to enhance robustness across varying defect sizes. Beyond these representative models, drone-assisted inspection frameworks have also advanced rapidly. Heo and Na [

28] provided a systematic evaluation of aerial inspection practices, identifying practical advantages and persistent challenges. Meanwhile, Hu et al. (2025) [

29] introduced RDSS-YOLO, a lightweight yet capable framework achieving real-time detection and segmentation performance in operational wind farms. Recently, transformer-based detectors have also been explored in the WTB inspection domain. For example, Yang et al. (2025) introduced FRE-DETR, a transformer-driven model that achieved improved detection accuracy while maintaining reduced computational complexity compared with earlier RT-DETR variants [

30]. These developments highlight the growing potential of transformer architectures as an alternative paradigm within the broader object detection landscape.

Despite these significant advancements, a critical gap persists in the literature. Most existing research—whether based on CNNs or transformers—has focused predominantly on detecting visible-spectrum defects in RGB imagery. However, the unique challenges posed by TTPs in infrared thermography remain largely unaddressed. These patterns, characterized by faint thermal gradients, low contrast, and small spatial extent, are easily overlooked by conventional object-detection models due to their limited spatial focus and insufficient multi-scale feature fusion capability. As a result, many true defects go undetected, whereas false alarms tend to increase under complex operating conditions. These difficulties underscore the necessity for a more resilient DL architecture capable of emphasizing subtle temperature cues while maintaining reliable feature aggregation across multiple scales. Components such as the convolutional block attention module (CBAM) and bidirectional feature pyramid network (BiFPN) have shown notable promise in addressing similar limitations within RGB-based applications [

1,

3]. Nevertheless, their synergistic integration and optimization for the distinct modality of infrared-based TTP detection remain unexplored, forming the central motivation of this study.

This work presents A-BiYOLOv9, a DL architecture designed to detect TTPs on WTBs using infrared imagery. A-BiYOLOv9 extends the YOLOv9 framework by refining both the backbone and neck components of the architecture. CBAMs were embedded at selected convolutional stages to strengthen spatial and channel-wise attention, thereby enhancing the extraction of discriminative features—an essential improvement for identifying subtle thermal anomalies. In the neck, the conventional path aggregation network (PAN) was replaced with a BiFPN, which enables bidirectional information flow and adaptive weighting across scales, facilitating more efficient multi-level feature fusion. In combination, the CBAM-enhanced backbone and BiFPN-based neck improve the model’s capability to capture fine spatial details and maintain robust feature representation. Consequently, the system achieves higher reliability in detecting small and low-contrast TTPs. The proposed A-BiYOLOv9 framework thus provides a promising foundation for real-time, non-contact fault monitoring in wind turbine maintenance applications.

The main contributions of this study can be summarized as follows:

A novel detection architecture, A-BiYOLOv9, was developed by integrating CBAM and BiFPN modules to enhance spatial attention, feature fusion, and detection robustness for small-scale and low-contrast thermal anomalies.

Extensive experiments demonstrated that A-BiYOLOv9 achieves higher detection accuracy and operational robustness compared with current state-of-the-art CNN- and transformer-based models.

Unlike previous studies focused primarily on RGB-domain defects, this work applied DL to infrared thermographic imagery, specifically targeting the detection of TTPs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset Description

In this work, the publicly available KI-VISIR dataset [

21] was utilized to study WTBs under real operating conditions. The dataset was collected from 30 onshore turbines across Germany while in operation, covering both the suction side (SS) and pressure side (PS) of the blades to provide a comprehensive view of their aerodynamic and structural behavior.

Altogether, the KI-VISIR dataset contains 1206 calibrated thermographic images and 2160 corresponding RGB images, representing 90 blades (three per turbine). The data are systematically categorized by blade side, clock orientation, and axial segmentation. Each blade is divided into seven consecutive sections from the hub toward the tip. The dataset provides expert-annotated bounding boxes identifying TTPs across all thermal images. These annotations serve as ground truth for supervised learning approaches to TTP detection. In this study, only the thermal imagery was used, as it captures distinctive wedge-shaped thermal patterns resulting from turbulence-altered heat convection, enabling reliable fault identification [

31,

32].

The infrared thermographic data were acquired using an Infratec IR8800 long-wave infrared camera (InfraTec GmbH, Dresden, Germany) equipped with a cooled HgCdTe (MCT) detector operating in the 7.7–10.4

m spectral range. The system featured a spatial resolution of 512 × 640 pixels, NETD < 30 mK, and a 200 mm focal-length lens. Mounted on a pan–tilt unit located approximately 100–120 m from the turbine base, the setup enabled stable imaging of rotating blades. Each image was stored as a 16-bit calibrated temperature matrix with an effective ground sampling distance of approximately 25–35 mm/px. Further details on the acquisition setup, calibration procedures, and environmental conditions are available in Ref. [

21].

In the original KI-VISIR dataset, annotations were provided in GeoJSON format, containing class labels and corresponding bounding-box coordinates for each identified TTP. To ensure labeling consistency, 104 unannotated thermographic images were excluded from the dataset, resulting in a final collection of 1102 images containing 5852 labeled TTP instances.

Table 1 summarizes the annotated bounding-box statistics of the KI-VISIR dataset, while

Figure 1 presents the corresponding statistical analysis in the form of a correlogram, illustrating the normalized spatial and scale distributions of the annotated TTP regions.

As shown in

Figure 1, the majority of bounding boxes represent small regions of interest, with both width and height values concentrated below 0.15 in normalized coordinates. Widths are mostly under 0.10, while heights primarily fall between 0.05 and 0.10. Horizontally, box centers are fairly uniform across the blade span, whereas vertically, they tend to cluster near the midsection of the blade. This strong bias toward small, mid-blade anomalies suggests that conventional object detectors may encounter difficulties in maintaining high precision and recall when identifying low-contrast, small-scale thermal features.

2.2. Data Preprocessing and Data Augmentation

Before training, all infrared thermograms from the KI-VISIR dataset, each containing expert-annotated bounding boxes identifying TTPs, were preprocessed to ensure uniformity in spatial resolution, temperature–intensity distribution, and visual clarity. The complete preprocessing workflow, illustrated in

Figure 2, follows four sequential stages: original normalized, contrast enhancement (CLAHE), and HSV color space conversion. The left column of

Figure 2a corresponds to the suction side (SS) of the WTB, whereas the right column (b) represents the pressure side (PS).

Initially, the original calibrated thermal images—acquired at a resolution of —were normalized to a consistent temperature–intensity range to minimize frame-to-frame variation and enhance local contrast across the blade surface. Subsequently, contrast-limited adaptive histogram equalization (CLAHE) was applied to further amplify subtle thermal gradients and highlight low-intensity turbulence traces that might otherwise be overlooked in raw imagery. Finally, the enhanced images were transformed into the HSV color space to improve feature separability by decoupling luminance (V) from chromatic components (H and S), facilitating better feature extraction during model training. Throughout each transformation, the bounding-box coordinates were preserved and reprojected when necessary to ensure perfect alignment between the processed images and their annotations. This preprocessing pipeline established a uniform and physically consistent foundation for the subsequent data augmentation and model training stages.

To improve the model’s generalization ability and prevent overfitting, a series of controlled data augmentation techniques was applied to preprocessed infrared thermograms. These operations were designed to simulate realistic changes in blade orientation, illumination, and camera positioning that may occur during field inspections or operational monitoring. The complete augmentation workflow, illustrated in

Figure 3, consists of four principal transformations: horizontal flip, translation, scaling, and HSV/brightness adjustment. The left column of

Figure 3a represents the suction side (SS) of the WTB, while the right column (b) shows the pressure side (PS).

Horizontal flipping was applied with a probability of 0.5 to generate mirrored blade perspectives, effectively simulating variations in camera orientation between consecutive inspections. A translation operation of 10% was used to emulate minor camera shifts and positional offsets, enhancing robustness against partial occlusions and irregular framing. Scaling transformations with a factor of 0.5 were employed to reproduce apparent size variations of the blades caused by different viewing distances or zoom levels, ensuring the model’s scale-invariance during detection. Finally, controlled HSV and brightness adjustments were incorporated to simulate realistic emissivity and illumination differences across thermal images, thereby increasing generalization under varying environmental and operational conditions.

In addition to these primary transformations, image-level transformations, implemented via the Albumentations library, included blurring, median filtering, grayscale conversion, and contrast-limited adaptive histogram equalization (CLAHE), each applied with a 1% probability. These additional augmentations introduced subtle appearance variations that improved generalization under diverse imaging conditions without compromising thermal feature integrity.

Following augmentation, the dataset underwent a substantial expansion in both sample count and annotation density, as summarized in

Table 1. The number of training and validation images increased from 688 to 2365, while the total annotated bounding boxes rose from 5852 to 12,988 across all subsets. The original dataset was partitioned with approximately 62% for training and validation and 38% for testing. After augmentation, this distribution shifted to 70% training, 15% validation, and 15% testing, reflecting standard practices in DL for maintaining adequate training data while preserving evaluation integrity. Notably, the validation and test subsets (414 images each) were kept fixed to ensure consistent benchmarking and unbiased performance evaluation. This threefold increase in the effective dataset size significantly enhanced the diversity of thermal patterns and spatial contexts available to the model, thereby improving its robustness and detection stability across different turbine blade sides (SS and PS).

2.3. The Proposed A-BiYOLOv9 Model

The proposed A-BiYOLOv9 architecture builds upon YOLOv9-c as a baseline framework, redesigned to address the challenges of small and low-contrast thermal anomaly detection in infrared turbine inspections. The model preserves the computational efficiency of YOLOv9 while introducing two complementary enhancements: the CBAM for refined feature calibration and the BiFPN for improved multi-scale information fusion. The overall structure of the proposed architecture is illustrated in

Figure 4.

The backbone employs convolutional layers, RepNCSP blocks, and an SPPELAN module to extract features at multiple depths. To better emphasize subtle thermal cues, CBAM blocks are integrated immediately after the backbone outputs corresponding to the

,

, and

feature maps (with spatial resolutions of

,

, and

, respectively). CBAM sequentially applies channel and spatial attention to adaptively highlight salient thermal patterns while suppressing irrelevant background noise [

33]. The resulting refined feature maps become more discriminative for the localization of low-contrast thermal turbulence patterns.

The neck component incorporates the BiFPN structure, which enables bidirectional feature fusion between the CBAM-refined maps

. Unlike conventional FPN or PANet designs, BiFPN allows both top-down and bottom-up information flow through learnable weights

assigned to each input feature, yielding a normalized fusion output [

34]:

where

refers to the feature maps that come together during each fusion step. The parameters

(

) are the learnable weights, and

is added as a small safeguard to keep the calculations stable. This weighting mechanism adaptively balances semantic and spatial information, enhancing feature consistency across scales while maintaining computational efficiency [

35,

36].

The combined design allows A-BiYOLOv9 to effectively exploit both fine-grained local textures and high-level contextual cues across multiple feature scales. Consequently, the model demonstrates enhanced robustness against background clutter and improved precision–recall performance when detecting thermographic turbulence patterns under real-world conditions.

2.4. Training Configuration

All experiments were conducted on Windows 11 Pro using Python 3.10.11, PyTorch 2.5.1 with CUDA 12.1, and the Ultralytics YOLO framework (v8.2.18). The hardware configuration comprised an AMD Ryzen 9 5900X CPU, 32 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2070 SUPER (8 GB VRAM).

The A-BiYOLOv9 network was trained from a pre-trained checkpoint using input images resized to

pixels. Based on preliminary trials, the models converged at 30 epochs; therefore, the total number of training epochs was set to 30. The main hyperparameter configurations used for training are summarized in

Table 2.

2.5. Evaluation Metrics

The performance of the model was assessed using a set of standard metrics often reported in object detection research. Together, these metrics give a clear picture of how accurately and efficiently the method performs.

Precision (

P) represents the share of correct detections among all positive predictions, as shown in Equation (

2):

where

denotes the number of true positives and

represents false positives.

In simple terms, the recall (

R) value tells how well the model manages to find every object that’s truly present, as given in Equation (

3):

where

stands for the count of false negatives. To reflect the balance between precision and recall, the

-score comes into play. It represents their harmonic mean and is written as:

Another measure used in this study is the intersection over union (

), which compares the predicted bounding box (

) with the ground-truth box (

) to determine how much they overlap:

Building on

, the average precision (

) is computed as the area under the precision–recall curve, defined in Equation (

6):

For a more comprehensive evaluation, three mean average precision (mAP) metrics are reported. The first, mAP@0.5, computes the average precision at a fixed

threshold of 0.5. The second, mAP@0.75, provides a stricter criterion for localization accuracy. Finally, mAP@0.5:0.95 follows the COCO evaluation protocol by averaging

values over multiple

IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95 with a step size of 0.05, as shown in Equation (

7):

where

T is the total number of

thresholds.

3. Experimental Results and Discussion

3.1. Ablation Experiments

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed architectural modifications, a series of ablation experiments was conducted using the YOLOv9 baseline. The evaluation progressively incorporated the CBAM and BiFPN modules to examine their individual and combined contributions to detection accuracy. The experimental results are summarized in

Table 3.

As summarized in

Table 3, each architectural modification yields a distinct contribution to detection performance under varying

IoU thresholds. The baseline YOLOv9 achieves an mAP@0.5 of 0.995 and an mAP@0.5:0.95 of 0.969, demonstrating strong overall precision (0.998) and recall (0.994). When the CBAM module is introduced, the mAP@0.5:0.95 decreases slightly to 0.879, a minor fluctuation that can be attributed to the stricter

IoU thresholds used in the COCO-style metric rather than a true degradation in detection quality. Replacing the PAN with the BiFPN structure reduces the mAP@0.5:0.95 from 0.969 to 0.882, yet provides more stable multi-scale feature fusion. Finally, when both modules are jointly integrated in the proposed A-BiYOLOv9, the mAP@0.5:0.95 returns to 0.969—the same as the baseline—while recall improves from 0.994 to 0.997 and precision remains high at 0.998. This balanced outcome confirms that CBAM and BiFPN act complementarily, enhancing the model’s ability to maintain consistent localization accuracy and precision–recall equilibrium across varying

IoU thresholds.

3.2. Comparison Experiments

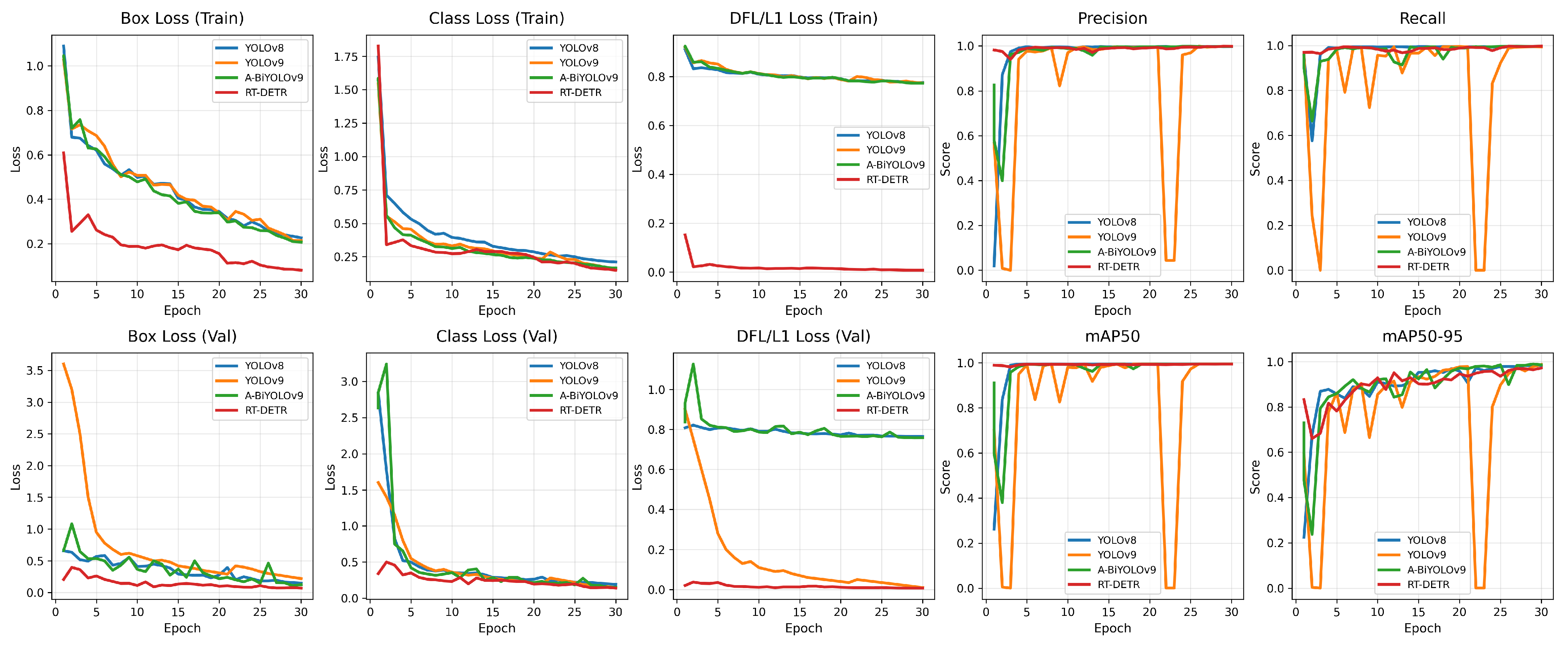

Figure 5 illustrates the comparative training and validation behaviors of the four models in terms of loss convergence and metric evolution over 30 epochs. Across all models, a consistent decline in box, class, and DFL/L1 losses indicates effective optimization. RT-DETR exhibited the fastest and most stable convergence in all loss components due to its transformer-based feature encoding, maintaining low and steady loss values throughout training. YOLOv8 and YOLOv9 showed similar convergence patterns, though YOLOv9 experienced greater fluctuations in the early epochs, suggesting less stable gradient dynamics during optimization. The proposed A-BiYOLOv9 achieved a smoother and more consistent reduction in both training and validation losses, converging without the abrupt oscillations observed in YOLOv9. Precision, recall, and mAP values increased steadily, reaching near-saturation within the first ten epochs and remaining stable thereafter. This behavior demonstrates that the integration of CBAM and BiFPN modules enhanced feature expressiveness and improved the model’s generalization capability, leading to balanced convergence and stable performance across all evaluation metrics.

Table 4 summarizes the comparative detection performance of the evaluated models, including the proposed A-BiYOLOv9. Overall, all models achieved near-identical precision and recall values above 0.99, confirming their high detection reliability for TTPs. Between the conventional YOLO variants, YOLOv9 slightly outperformed YOLOv8, showing a marginal improvement in mAP@75, which suggests enhanced localization accuracy for more stringent

IoU thresholds. RT-DETR also demonstrated competitive results, particularly in recall, benefiting from its transformer-based feature aggregation mechanism. The proposed A-BiYOLOv9 achieved the most balanced and consistent performance across all metrics, with an mAP@75 of 0.989 ± 0.001 and an overall mAP@50–95 of 0.969 ± 0.002. These results indicate that the integration of CBAM and BiFPN modules effectively strengthened multi-scale feature representation and attention to fine-grained thermal cues, yielding slightly higher detection stability and precision within narrow confidence intervals.

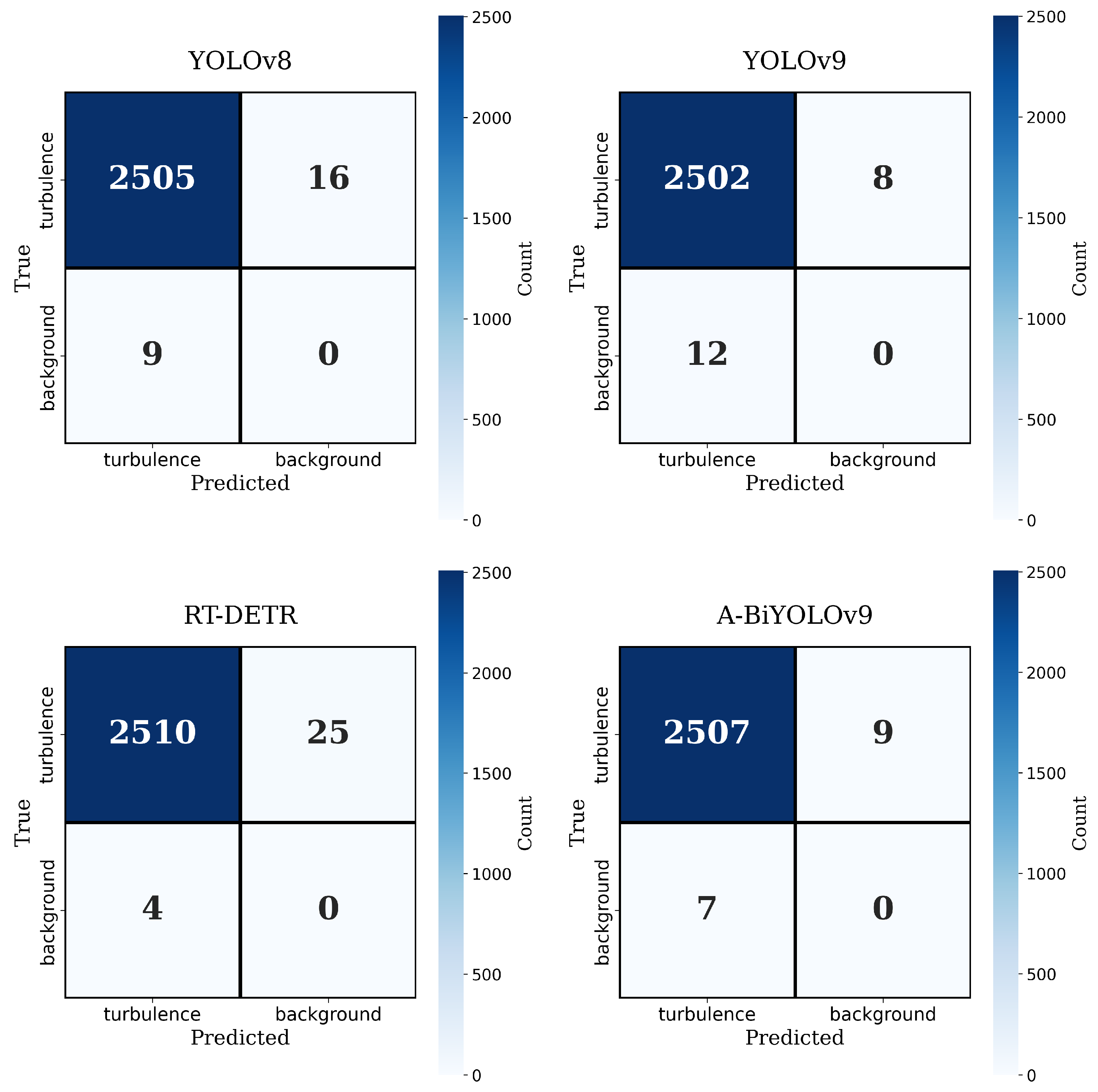

Figure 6 presents the confusion matrices comparing the detection accuracy of YOLOv8, YOLOv9, RT-DETR, and the proposed A-BiYOLOv9 models on the test set. Each matrix represents the model’s ability to correctly distinguish TTPs from background regions. In all models, the top-left cell corresponds to true positive (TP) detections, whereas the top-right and bottom-left cells denote false negatives (FN) and false positives (FP), respectively.

Across the evaluated architectures, all models achieved high TP counts, confirming reliable recognition of TTPs under varying thermal conditions. YOLOv8 correctly detected 2505 instances with 16 FNs and 9 FPs, resulting in a precision of 0.996 and a recall of 0.993. YOLOv9 achieved slightly higher recall at 0.997 but showed minor fluctuations in precision due to 12 FPs. RT-DETR achieved the highest precision (0.998) owing to its low FP count, but exhibited slightly reduced recall (0.990) as a result of 25 missed detections (FNs). The proposed A-BiYOLOv9 achieved the best overall balance between precision and recall, detecting 2507 TPs with only 9 FNs and 7 FPs. This corresponds to a precision of 0.997 and a recall of 0.996, indicating strong generalization across unseen samples. The improved balance is primarily due to the integration of BiFPN and CBAM modules, which enhanced multi-scale feature fusion and attention to subtle thermal gradients. Consequently, A-BiYOLOv9 maintained high detection reliability and robustness in distinguishing fine-grained turbulence features from background noise, consistent with the study’s objective of achieving stable and interpretable TTP detection under realistic operational conditions.

The final comparative evaluation of the model variants is presented in

Table 5. This analysis aims to statistically validate the performance differences among the evaluated architectures during the stable convergence phase. To this end, paired

t-tests and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were conducted over the last ten training epochs to quantify variability and assess the significance of observed performance gaps. The table summarizes the computed test statistics (

t-statistic and Wilcoxon

p-value), corresponding significance levels, and the mean performance differences between the compared models. These results provide a statistical basis for evaluating whether observed improvements in detection metrics are statistically meaningful rather than random fluctuations.

The findings indicate that the proposed A-BiYOLOv9 model achieves statistically significant improvements compared to all baseline models, including YOLOv8, YOLOv9, and the transformer-based RT-DETR, corresponding to approximately 1.3%, 0.7%, and 0.4% higher mean detection performance, respectively (p < 0.05). This outcome confirms that the integration of CBAM and BiFPN modules provides a statistically validated and practically meaningful performance gain. RT-DETR also outperforms YOLOv8 with an improvement of around 1.1% (p < 0.05), while the difference between YOLOv9 and RT-DETR remains below the statistical threshold (p > 0.05), indicating only about a 0.5% deviation in average performance. A-BiYOLOv9 further demonstrates a modest yet statistically significant advantage of roughly 0.4% over RT-DETR, suggesting that an enhanced CNN-based architecture can rival—and in certain cases surpass—transformer-based designs in detection accuracy. The smallest performance gap, approximately 0.6%, is observed between YOLOv9 and YOLOv8, where no statistically meaningful improvement is detected (p > 0.05), implying comparable stability and consistency between these two models. Overall, the statistical analyses confirm that A-BiYOLOv9 delivers not only measurable quantitative gains but also statistically validated improvements over competing models.

3.3. Visualization of Detection Results

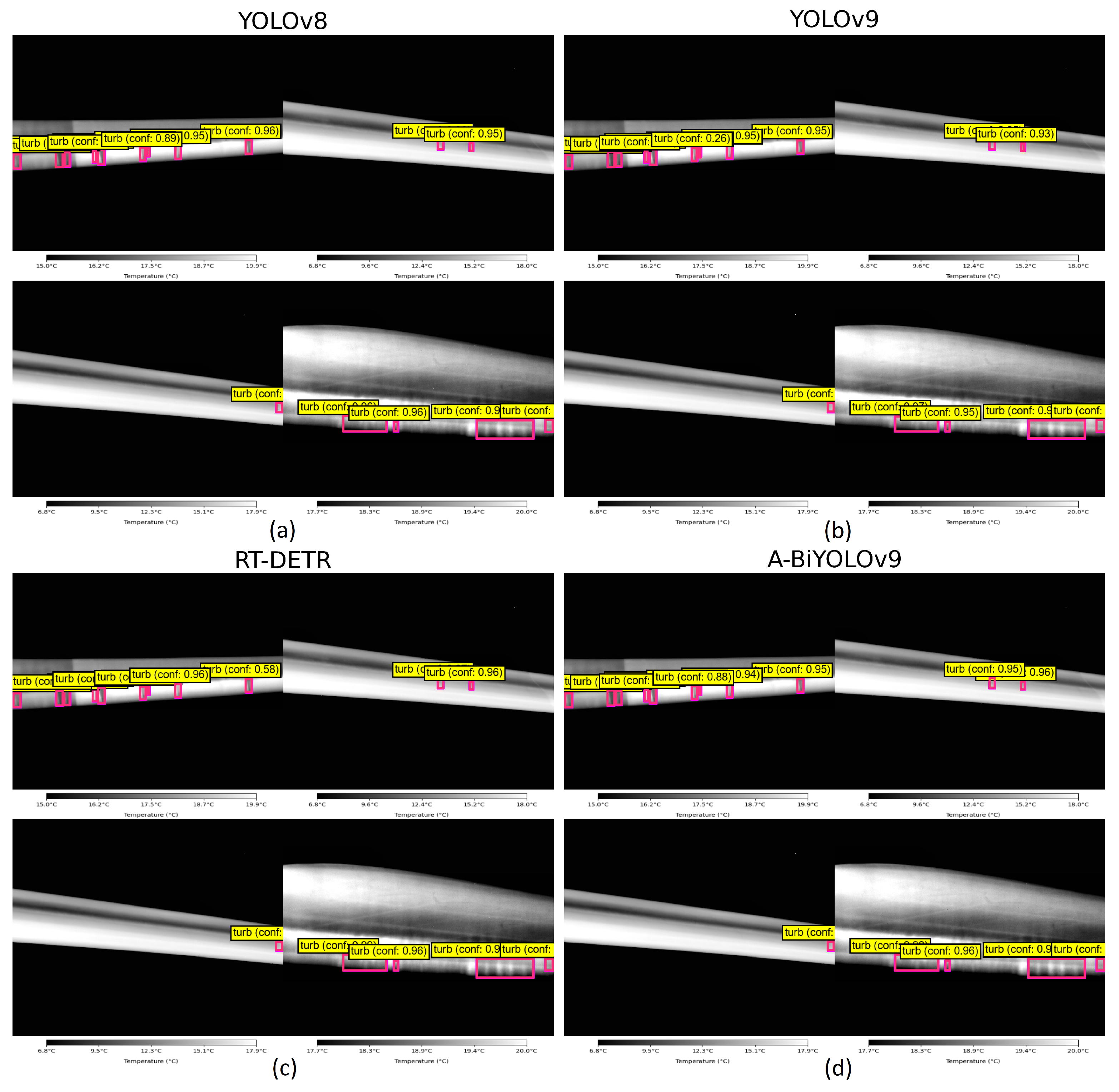

Figure 7 shows qualitative detection results obtained with YOLOv8, YOLOv9, RT-DETR, and the proposed A-BiYOLOv9, respectively. As shown in

Figure 7a, YOLOv8 can identify major turbulence regions with high confidence; however, several small-scale anomalies along the blade surface remain undetected, particularly in low-contrast thermal regions. In contrast, YOLOv9 in

Figure 7b demonstrates improved sensitivity, detecting a greater number of turbulence patterns. However, the model occasionally generates redundant or overlapping bounding boxes, which suggests limited robustness in differentiating fine-scale patterns from background noise.

The transformer-based RT-DETR, illustrated in

Figure 7c, provides smoother bounding-box alignments and successfully localizes multiple turbulence clusters. While its global attention mechanism enhances recall by capturing broader contextual cues, it sometimes yields less precise localization in complex or noisy regions, resulting in slightly less stable detections compared with the proposed method. Finally,

Figure 7d shows that A-BiYOLOv9 produces clear and steady detections. Compared with YOLOv8, YOLOv9, and RT-DETR, it handles both wide and fine turbulence areas effectively and maintains consistent confidence scores across different thermal settings. Thanks to the joint use of CBAM and BiFPN, the model can pick up small anomalies that the other versions either miss or detect with uncertainty. This effect is especially noticeable on blade sections with strong texture changes and uneven heat patterns.

The qualitative results agree with the data in

Table 4, confirming that A-BiYOLOv9 performs best overall and provides the most trustworthy localization of turbulence regions.

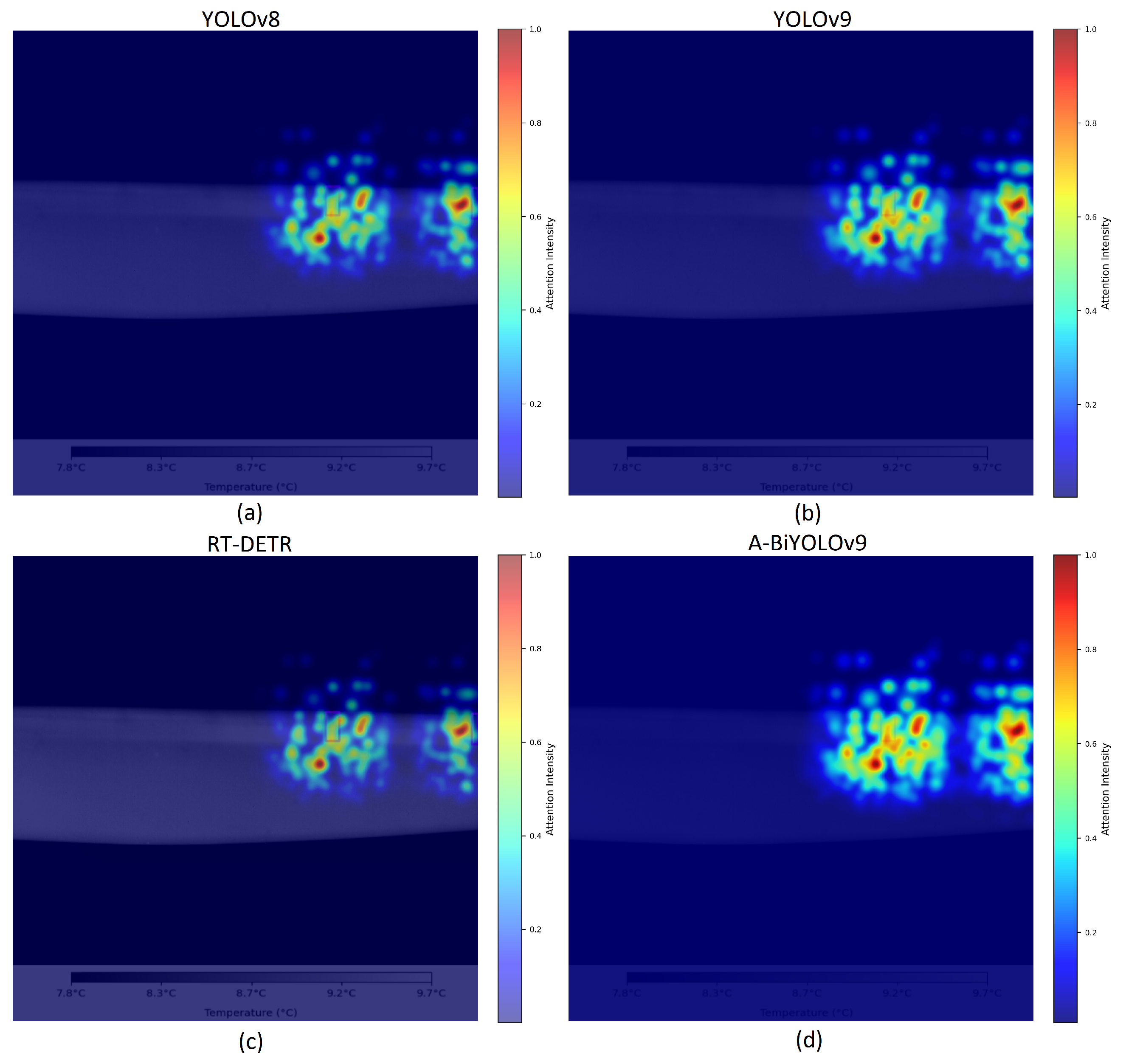

Clear differences can be observed in how the four models distribute their attention across the turbulence-affected regions, as illustrated in

Figure 8. In

Figure 8a, YOLOv8 exhibits a relatively uniform attention spread, although part of its activation extends into background areas that are thermally irrelevant. Compared with YOLOv8, YOLOv9 in

Figure 8b demonstrates a more compact focus on critical regions of the blade, with reduced spillover into the surrounding background. The transformer-based RT-DETR, shown in

Figure 8c, displays a distinct behavior—its attention appears broader and more diffused, capturing global context rather than concentrating on a few specific zones. While this global awareness supports improved recall, it also results in slightly softer localization boundaries. In contrast, the proposed A-BiYOLOv9 in

Figure 8d produces sharply concentrated attention over turbulence clusters.The heatmap reveals well-defined yellow–red activation regions that align closely with the actual turbulence patterns, while non-relevant blade areas remain minimally activated. This focused behavior reflects the synergistic effect of the CBAM and BiFPN modules, which together enhance spatial selectivity and cross-scale feature refinement. Overall, the heatmap comparison reinforces the quantitative findings, confirming that A-BiYOLOv9 achieves the most precise and thermally consistent feature localization among the evaluated models.

3.4. Discussion

The comparison among YOLOv8, YOLOv9, RT-DETR, and the proposed A-BiYOLOv9 offers several observations about how these detectors behave in thermographic wind turbine analysis. YOLOv8, with its compact design, converges quickly and performs reliably, which makes it appealing for setups where hardware resources are limited. At the same time, its smaller capacity restricts how well it can recognize fine or low-contrast details, a common challenge when detecting TTPs.

YOLOv9 provides a stronger baseline in terms of accuracy but exhibits less stable convergence during training and higher inference costs, indicating that its improvements come at the expense of computational efficiency.

The transformer-based RT-DETR delivers competitive performance and shows superior global context awareness through its attention mechanism, which helps capture large-scale turbulence regions. However, this same mechanism can slightly compromise spatial precision in fine-grained areas, leading to occasional misalignments compared with the proposed approach.

Among the tested models, A-BiYOLOv9 provides the best overall balance between accuracy and stability. The inclusion of CBAM and BiFPN helps the network cope with the dataset’s main difficulties—especially the large number of small bounding boxes and the presence of low-contrast regions. By learning to focus on informative channels and combining features across scales in both directions, A-BiYOLOv9 trains more smoothly and produces steadier validation results with stronger scores overall. These findings show that model designs adjusted to the statistical structure of a dataset can bring real gains in both precision and robustness.

Beyond the numbers, the results have clear practical meaning for wind turbine inspection. Being able to detect turbulence-induced defects accurately and consistently helps catch faults sooner, limits the chance of unnoticed damage spreading, and supports condition-based maintenance. The fast inference time of A-BiYOLOv9 proves that real-time monitoring can be done on modern GPUs, allowing it to fit easily into on-site or drone-based inspection systems. By spotting small and faint irregularities, the model can play a role in improving turbine safety and keeping equipment running efficiently with less downtime.

Overall, the discussion confirms that while generic YOLO architectures provide a solid baseline, targeted enhancements such as attention and adaptive feature fusion are necessary to meet the unique demands of thermographic anomaly detection in wind energy applications.