A 300 mV Josephson Arbitrary Waveform Synthesizer Chip at NIM †

Abstract

1. Introduction

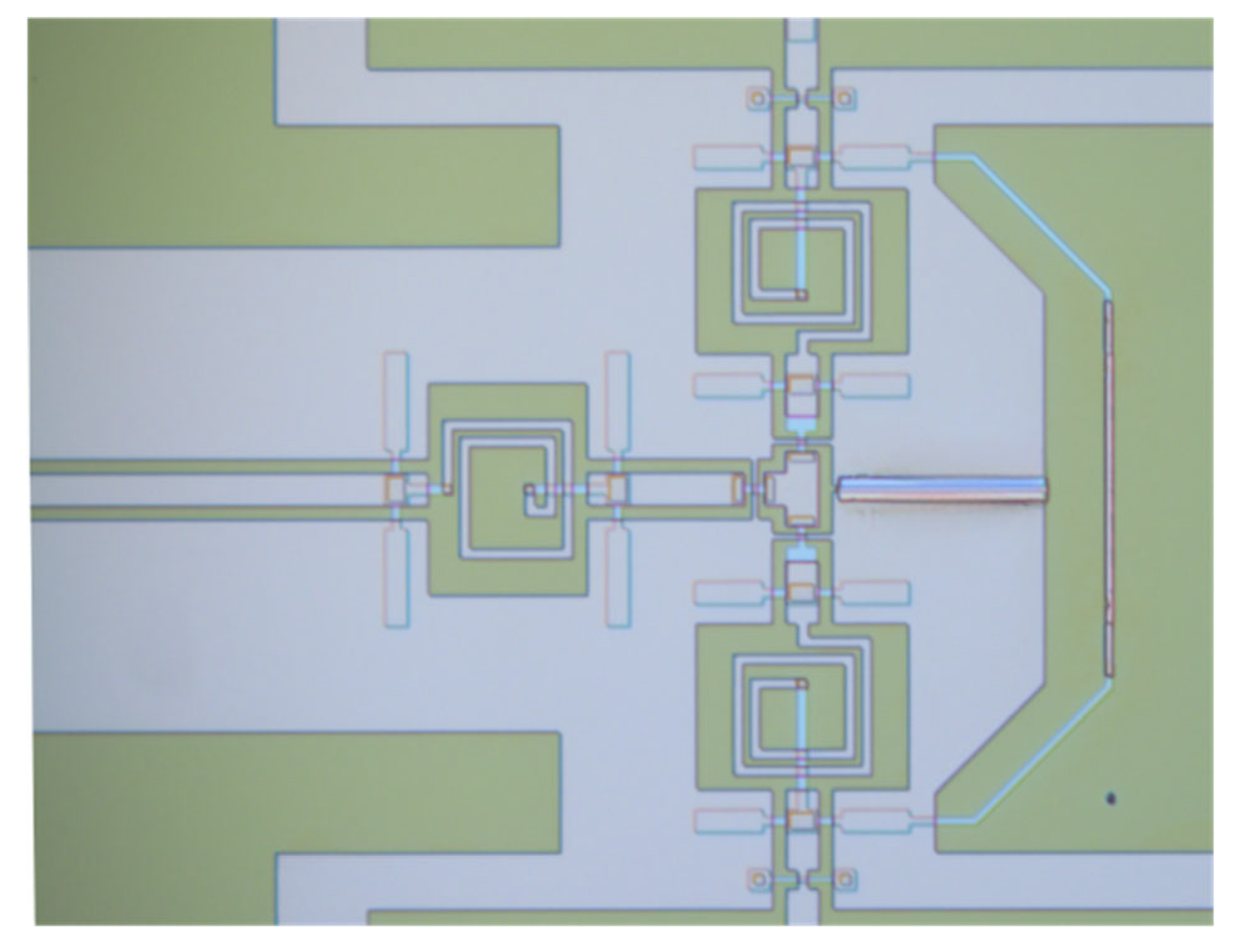

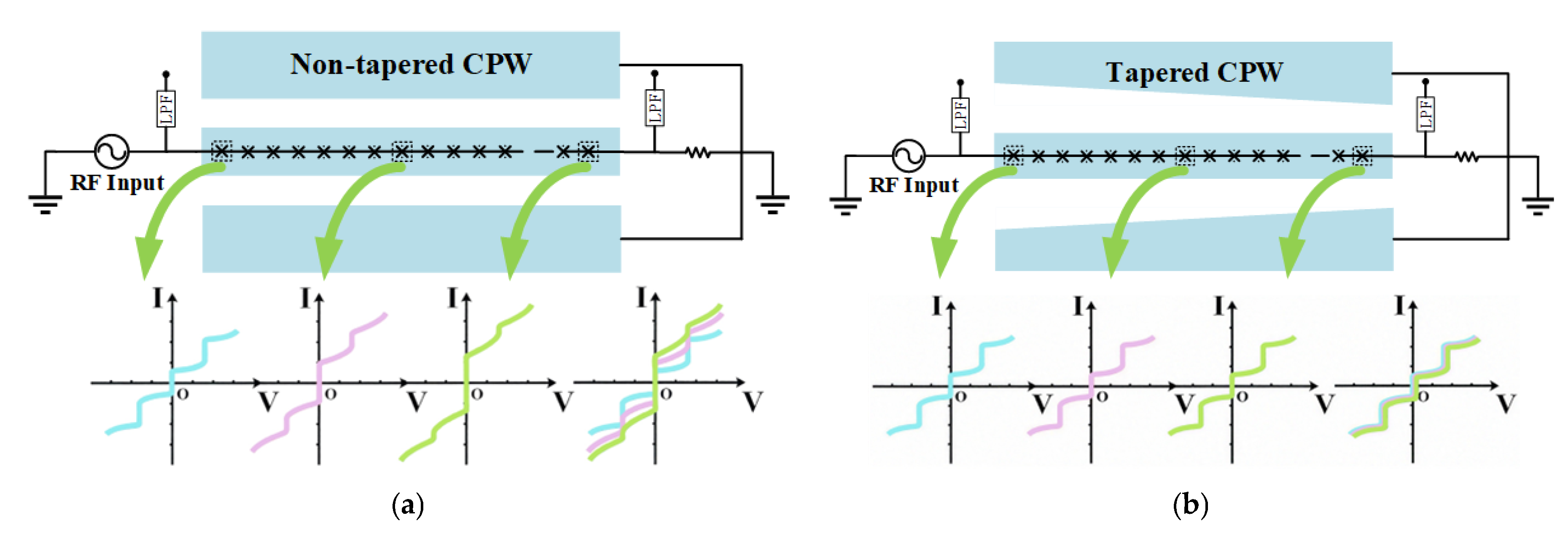

2. Chip Design

3. Device Fabrication

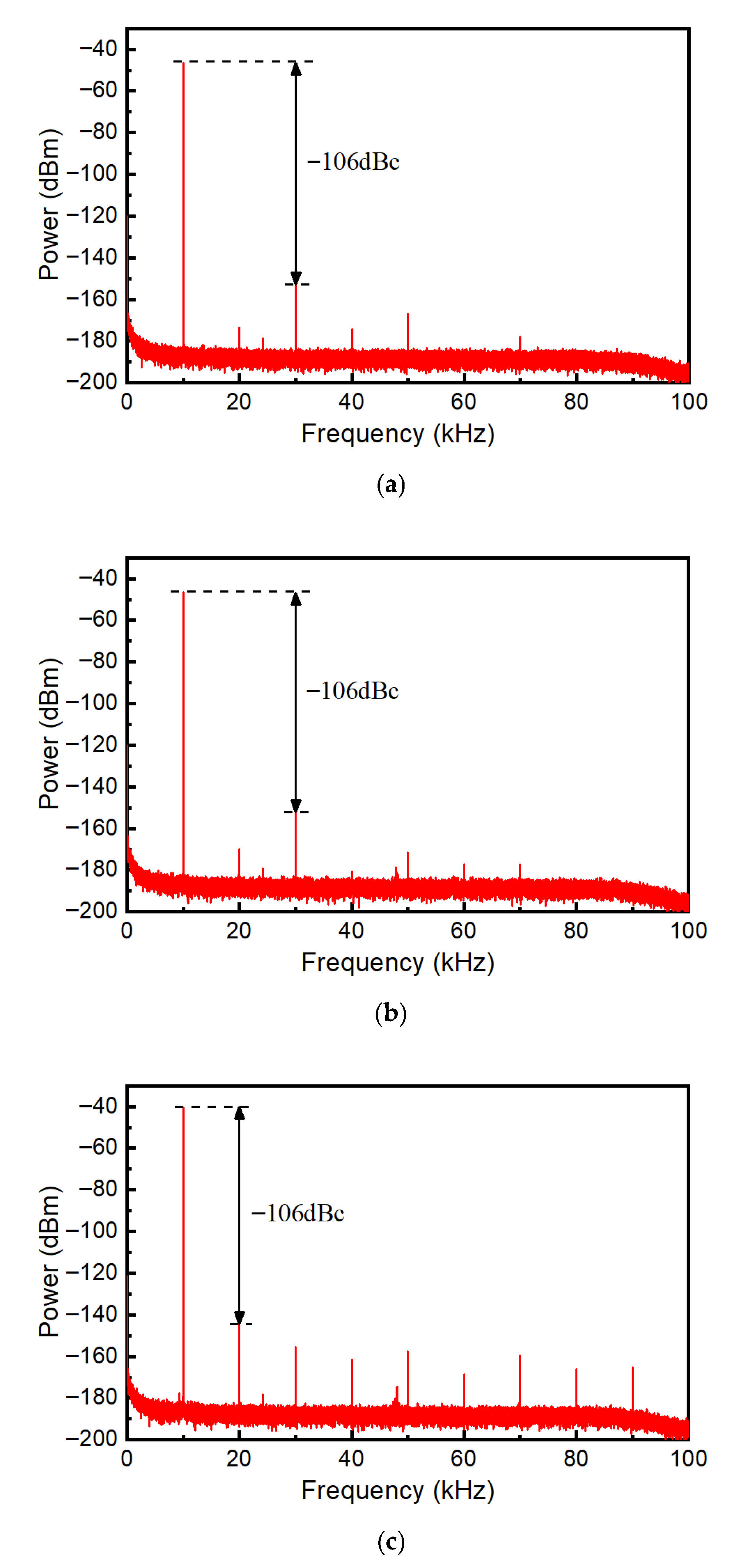

4. Measurement Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Josephson, B.D. Possible new effects in superconductive tunnelling. Phys. Lett. 1962, 1, 251–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djordjevic, S.; Séron, O.; Solve, S.; Chayramy, R. Direct comparison between a programmable and a conventional Josephson voltage standard at the level of 10 V. Metrologia 2008, 45, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Ojha, V.N.; Schlamminger, S.; Rüfenacht, A.; Burroughs, C.J.; Dresselhaus, P.D.; Benz, S.P. A 10 V programmable Josephson voltage standard and its applications for voltage metrology. Metrologia 2012, 49, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüfenacht, A.; Tang, Y.; Solve, S.; Fox, A.E.; Dresselhaus, P.D.; Burroughs, C.J.; Schwall, R.E.; Chayramy, R.; Benz, S.P. Automated direct comparison of two cryocooled 10 volt programmable Josephson voltage standards. Metrologia 2018, 55, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsbury, M.M.; Dresselhaus, P.D.; Bergren, N.F.; Burroughs, C.J.; Benz, S.P.; Popovic, Z. Broadband lumped-element integrated N-way power dividers for voltage standards. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2009, 57, 2055–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresselhaus, P.D.; Elsbury, M.M.; Olaya, D.; Burroughs, C.J.; Benz, S.P. 10 volt programmable Josephson voltage standard circuits using NbSi-barrier junctions. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2010, 21, 693–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burroughs, C.J.; Dresselhaus, P.D.; Rufenacht, A.; Olaya, D.; Elsbury, M.M.; Tang, Y.; Benz, S.P. NIST 10 V programmable Josephson voltage standard system. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2011, 60, 2482–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behr, R.; Kieler, O.; Kohlmann, J.; Müller, F.; Palafox, L. A Development and metrological applications of Josephson arrays at PTB. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2012, 23, 124002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, F.; Scheller, T.; Wendisch, R.; Behr, R.; Kieler, O.; Palafox, L.; Kohlmann, J. NbSi barrier junctions tuned for metrological applications up to 70 GHz: 20 V arrays for programmable Josephson voltage standards. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2012, 23, 1101005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamori, H.; Kohjiro, S. Fabrication of voltage standard circuits utilizing a serial–parallel power divider. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2016, 26, 1400404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, S.P.; Hamilton, C.A. A pulse-driven programmable Josephson voltage standard. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1996, 68, 3171–3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, S.P.; Burroughs, C.J.; Dresselhaus, P.D.; Bergren, N.F.; Lipe, T.E.; Kinard, J.R. An AC Josephson voltage standard for AC–DC transfer standard measurements. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2007, 56, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, S.P.; Burroughs, C.J.; Dresselhaus, P.D. Low harmonics distortion in Josephson arbitrary waveform synthesizer. Metrologia 2000, 77, 1014–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, S.; Behr, R.; Hagen, T.; Kieler, O.; Lee, J.; Palafox, L.; Schurr, J. A novel two-terminal-pair pulse-driven Josephson impedance bridge linking a 10 nF capacitance standard to the quantized hall resistance. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 54, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overnev, F.; Flowers-Jacobs, N.E.; Jeanneret, B.; Rüfenacht, A.; Fox, A.E.; Underwood, J.M.; Koffman, A.D.; Benz, S.P. Josephson-based full digital bridge for high-accuracy impedance comparisons. Metrologia 2016, 53, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flowers-Jacobs, N.E.; Rüfenacht, A.; Fox, A.E.; Waltman, S.B.; Schwall, R.E.; Brevik, J.A. Development and Applications of a Four-Volt Josephson Arbitrary Waveform Synthesizer. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Superconductive Electronics Conference, Riverside, CA, USA, 28 July–1 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kieler, O.; Behr, R.; Wendisch, R.; Kohlmann, J. Arrays of Stacked SNS Josephson Junctions for Pulse-Driven Josephson Voltage Standards. In Proceedings of the 13th European Conference on Applied Superconductivity, Geneva, Switzerland, 17–22 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ihlenfeld, W.G.K.; Landim, R.P. Investigations on Extending the Frequency Range of PJVS Based AC Voltage Calibrations by Coherent Subsampling. In Proceedings of the 2016 Conference on Precision Electromagnetic Measurements, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 10–15 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kieler, O.; Karlsen, B.; Ohlckers, P.A.; Bardalen, E.; Akram, M.N.; Behr, R.; Ireland, J.; Williams, J.M.; Malmbekk, H.; Palafox, L.; et al. Optical Pulse-Drive for the Pulse-Driven AC Josephson Voltage Standard. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2019, 29, 1200205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Zhong, Q.; Cao, W.H.; Li, J.J.; Zhou, K.L.; Qu, J.F. 300 mV Josephson Arbitrary Waveform Synthesizer Chip in NIM. In Proceedings of the Conference on Precision Electromagnetic Measurements, Denver, CO, USA, 6–12 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kieler, O.; Wendisch, R.; Gerdau, R.W.; Weimann, T.; Kohlmann, J.; Behr, R. Stacked Josephson Junction Arrays for the Pulse-Driven AC Josephson Voltage Standard. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2021, 31, 1100705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieler, O.; Behr, R.; Wendisch, R.; Bauer, S.; Palafox, L.; Kohlmann, J. Towards a 1 V Josephson arbitrary waveform synthesizer. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2014, 25, 1400305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behr, R.; Kieler, O.; Lee, J.; Bauer, S.; Palafox, L.; Kohlmann, J. Direct comparison of a 1 V Josephson arbitrary waveform synthesizer and an ac quantum voltmeter. Metrologia 2015, 52, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, S.P.; Waltman, S.B.; Fox, A.E.; Dresselhaus, P.D.; Rüfenacht, A.; Underwood, J.M.; Howe, L.A.; Schwall, R.E.; Burroughs, C.J. One-volt Josephson arbitrary waveform synthesizer. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2014, 25, 1300108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, S.P.; Waltman, S.B.; Fox, A.E.; Dresselhaus, P.D.; Howe, L.; Schwall, R.E.; Flowers-Jacobs, N.E. Performance Improvements for the NIST 1 V Josephson Arbitrary Waveform Synthesizer. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2015, 25, 1400105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, D.B.; Cabiati, F.; Fischer, J.; Fujii, K.; Karshenboim, S.J.; Margolis, H.S.; de Mirandés, E.; Mohr, P.J.; Nez, F.; Pachucki, K.; et al. The CODATA 2017 values of h, e, k, and NA for the revision of the SI. Metrologia 2018, 55, L13–L16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Kieler, O.; Behr, R.; Wendisch, R.; Gerdau, R.; Kuhlmann, K.; Kohlmann, J. Development of RF Power Dividers for the Josephson Arbitrary Waveform Synthesizer. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2020, 30, 1100105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Kieler, O.; Behr, R.; Gerdau, R.; Kuhlmann, K.; Kohlmann, J. Investigation of Broadband Wilkinson Power Dividers for Pulse-Driven Josephson Voltage Standards. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2021, 31, 1100305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H. Development of RF Power Dividers for High Integrated Circuits of AC Josephson Voltage Standards. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische University Braunschweig, Braunschweig, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Flowers-Jacobs, N.E.; Waltman, S.B.; Fox, A.E.; Dresselhaus, P.D.; Benz, S.P. Josephson Arbitrary Waveform Synthesizer with Two Layers of Wilkinson Dividers and an FIR Filter. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2016, 26, 1400307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xu, S.; Cheng, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Cao, W.; Li, J. Development of an on-chip Power Divider for the Quantum Voltage Chip. Acta Metrol. Sin. 2024, 45, 1855–1861. [Google Scholar]

- Khorshev, S.K.; Pashkovsky, A.I.; Rogozhkina, N.V.; Levichev, M.Y.; Pestov, E.E.; Katkov, A.S.; Behr, R.; Kohlmann, J.; Klushin, A.M. Accuracy of the New Voltage Standard Using Josephson Junctions Cooled to 77 K. In Proceedings of the 2016 Conference on Precision Electromagnetic Measurements, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 10–15 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Niemeyer, J.; Sakamoto, Y.; Vollmer, E.; Hinken, J.H.; Shoji, A.; Nakagawa, H.; Takada, S.; Kosaka, S. Nb/Al-oxide/Nb and NbN/MgO/NbN tunnel junctions in large series arrays for voltage standards. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1986, 25, L343–L345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behr, R.; Funck, T.; Schumacher, B.; Warnecke, P. Measuring resistance standards in terms of the quantized Hall resistance with a dual Josephson voltage standard using SINIS Josephson arrays. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2003, 52, 521–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlmann, J.; Müller, F.; Kieler, O.; Behr, R.; Palafox, L.; Kahmann, M.; Niemeyer, J. Josephson series arrays for programmable 10-V SINIS Josephson voltage standards and for Josephson arbitrary waveform synthesizers based on SNS junctions. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2007, 56, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, S.P.; Hamilton, C.A.; Burroughs, C.J.; Harvey, T.E.; Christian, L.A. Stable 1 volt programmable voltage standard. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1997, 71, 1866–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagedorn, D.; Kieler, O.; Dolata, R.; Behr, R.; Müller, F.; Kohlmann, J.; Niemeyer, J. Modified fabrication of planarsub-µm superconductor–normal metal–superconductor Josephson junctions for use in a Josephsonarbitrary waveform synthesizer. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2006, 19, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, Y.; Burroughs, C.J.; Dresselhaus, P.D.; Hadacek, N.; Yamamori, H.; Benz, S.P. Practical high-resolution programmable Josephson Voltage standards using double-and triple-stacked MoSi2-barrier junctions. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2005, 15, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, M.; Fritzsch, L.; Wende, G.; Meyer, H.G. SNS junction on Nb-Ti base for microwave circuits. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2002, 11, 1066–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamori, H.; Yamada, T.; Sasaki, H.; Shoji, A. A 10 V programmable Josephson voltage standard circuit with a maximum output voltage of 20 V. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2008, 21, 105007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, B.; Dresselhaus, P.D.; Benz, S.P. Co-sputtered amorphous NbxSi1-x barriers for Josephson-junction circuits. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2006, 16, 1966–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, S.P.; Dresselhaus, P.D.; Burroughs, C.J. Nanotechnology for next generation Josephson voltage standards. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2001, 50, 1513–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaya, D.; Baek, B.; Dresselhaus, P.D.; Benz, S.P. High-speed Nb/Nb–Si/Nb Josephson Junctions for Superconductive Digital Electronics. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2008, 18, 1797–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresselhaus, P.D.; Elsbury, M.M.; Benz, S.P. Tapered Transmission Lines with Dissipative Junctions. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2009, 19, 993–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AppCAD Design Assistant. Available online: https://www.broadcom.com/info/wireless/appcad (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Benz, S.P.; Dresselhaus, P.D.; Burroughs, C.J.; Bergren, N.F. Precision Measurements Using a 300 mV Josephson Arbitrary Waveform Synthesizer. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2007, 17, 864–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Centerline BE Width | Centerline WR Width | Gap Width | δ | Calculated Z0 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Designed | 15.00 μm | 15.00 μm | 10.00 μm | - | 51.4 Ω |

| Measured | 14.40 μm | 13.85 μm | 11.14 μm | 0.185 μm | 53.6 Ω |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jia, W.; Song, J.; Zhong, Y.; Zhou, K.; Han, Q.; Cao, W.; Li, J.; Cai, J.; Wan, J.; Zhao, Z. A 300 mV Josephson Arbitrary Waveform Synthesizer Chip at NIM. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11811. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111811

Jia W, Song J, Zhong Y, Zhou K, Han Q, Cao W, Li J, Cai J, Wan J, Zhao Z. A 300 mV Josephson Arbitrary Waveform Synthesizer Chip at NIM. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(21):11811. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111811

Chicago/Turabian StyleJia, Weiyuan, Jiuhui Song, Yuan Zhong, Kunli Zhou, Qina Han, Wenhui Cao, Jinjin Li, Jinhui Cai, Jun Wan, and Ziyi Zhao. 2025. "A 300 mV Josephson Arbitrary Waveform Synthesizer Chip at NIM" Applied Sciences 15, no. 21: 11811. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111811

APA StyleJia, W., Song, J., Zhong, Y., Zhou, K., Han, Q., Cao, W., Li, J., Cai, J., Wan, J., & Zhao, Z. (2025). A 300 mV Josephson Arbitrary Waveform Synthesizer Chip at NIM. Applied Sciences, 15(21), 11811. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111811