Software System for Thrust Prediction and Preliminary Engineering Design of Aircraft Using Visual Recognition and Flight Parameters

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Flight Parameter Data Processing

2.1. Preprocessing of Flight Parameter Data

2.2. Flight Maneuver Recognition

2.2.1. Review of the Previous Work

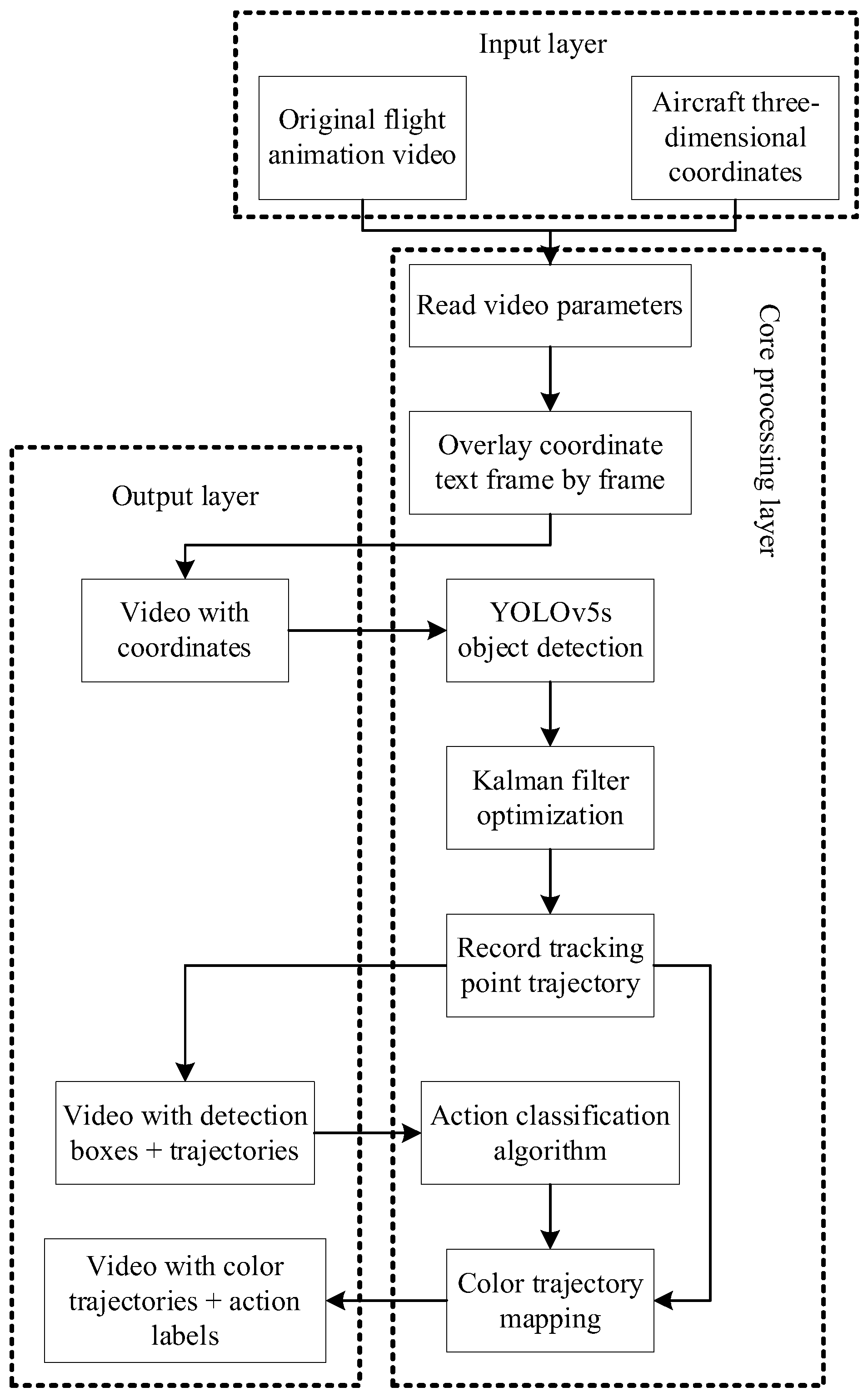

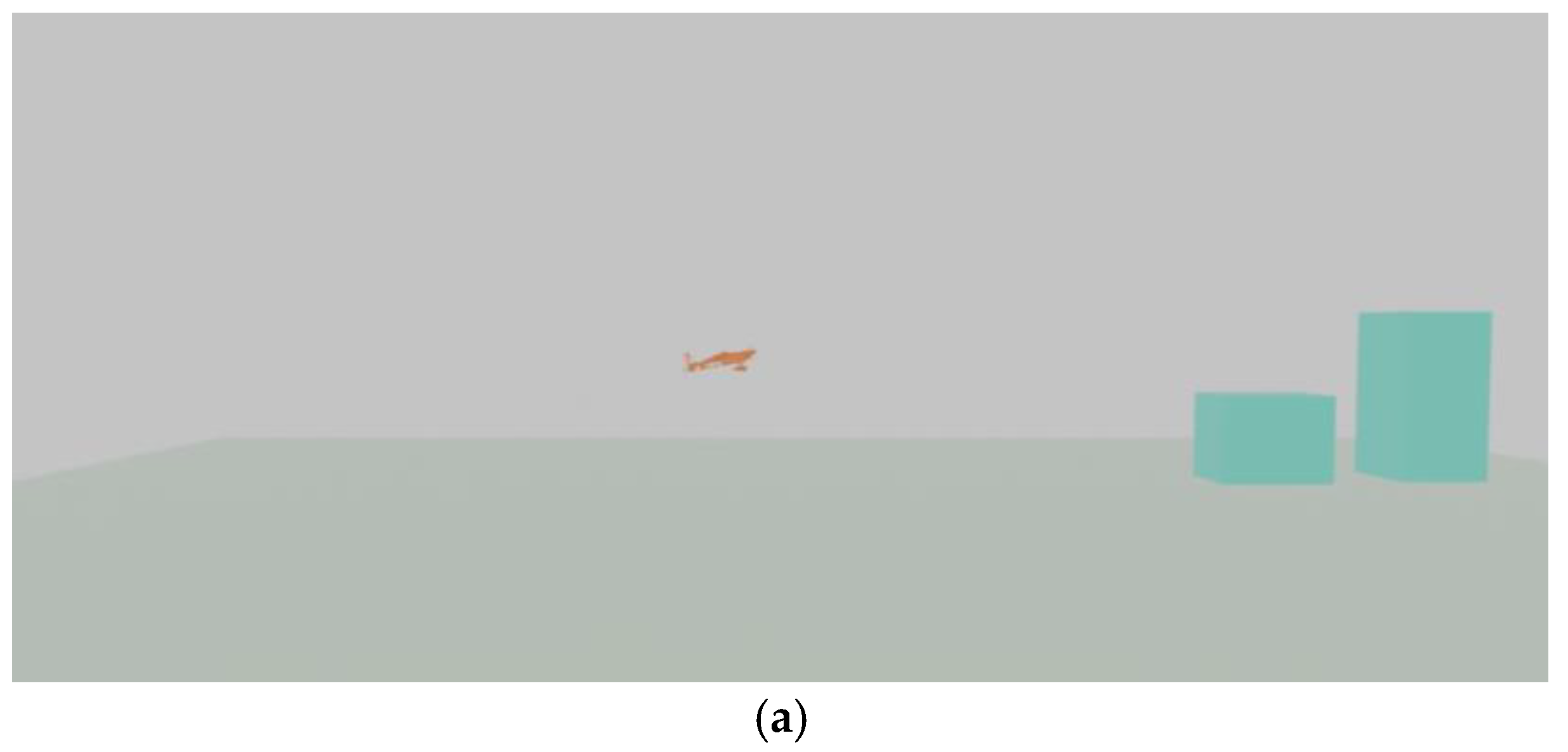

2.2.2. Vision-Based Recognition of Flight Maneuver

| Algorithm 1: Vision—based flight maneuver recognition program |

| 1. Function AircraftTracking() 2. input: video, csv 3. output: output video 4. Load YOLO model 5. Initialize Kalman filter 6. trajectory = [] 7. for each frame in video: 8. if YOLO.detect(frame): 9. Update Kalman filter 10. point = Kalman state 11. else 12. point = Kalman prediction 13. trajectory.append(point) 14. if frame index > 0: 15. dz = current z—previous z 16. angle = calculate angle() 17. maneuver = classify(dz, angle) 18. DrawTrajectory(trajectory, maneuver) 19. DisplayInfo(maneuver) 20. Write output frame 21. return output video 22. function classify(dz, angle) 23. if dz > 0: 24. return “turn climb” if angle > 45 else “straight climb” 25. else: 26. return “turn dive” if angle > 45 else “straight dive” |

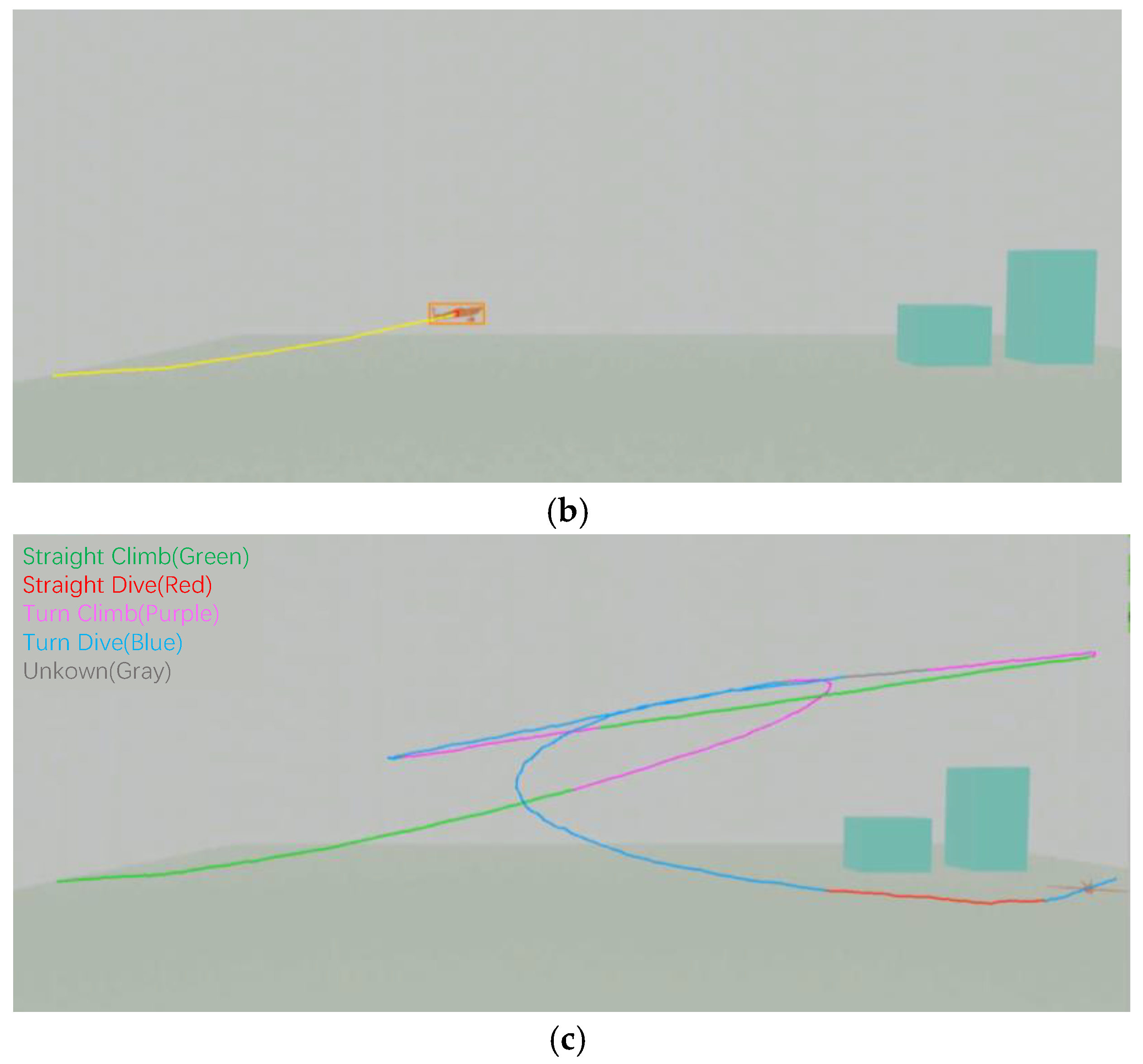

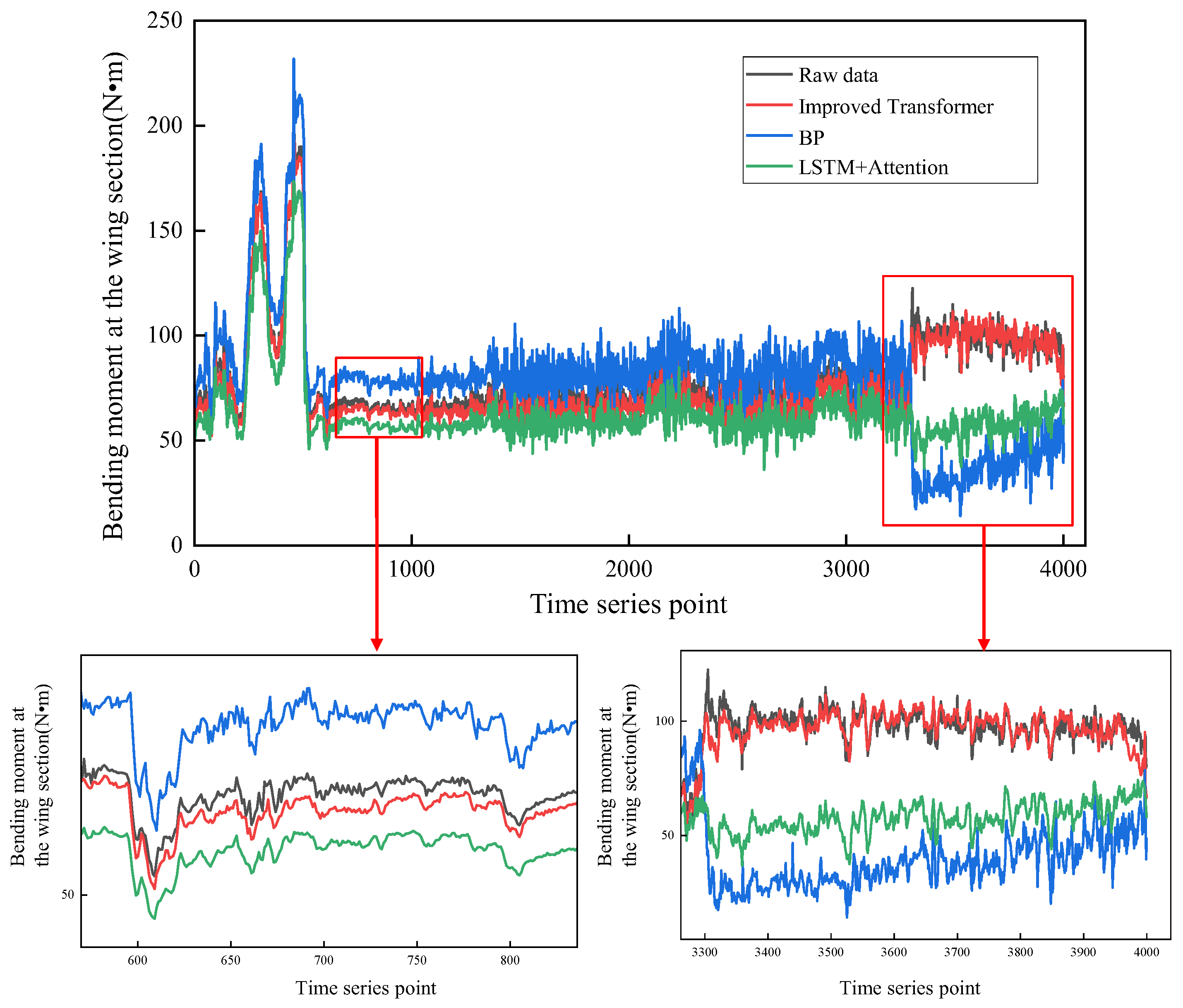

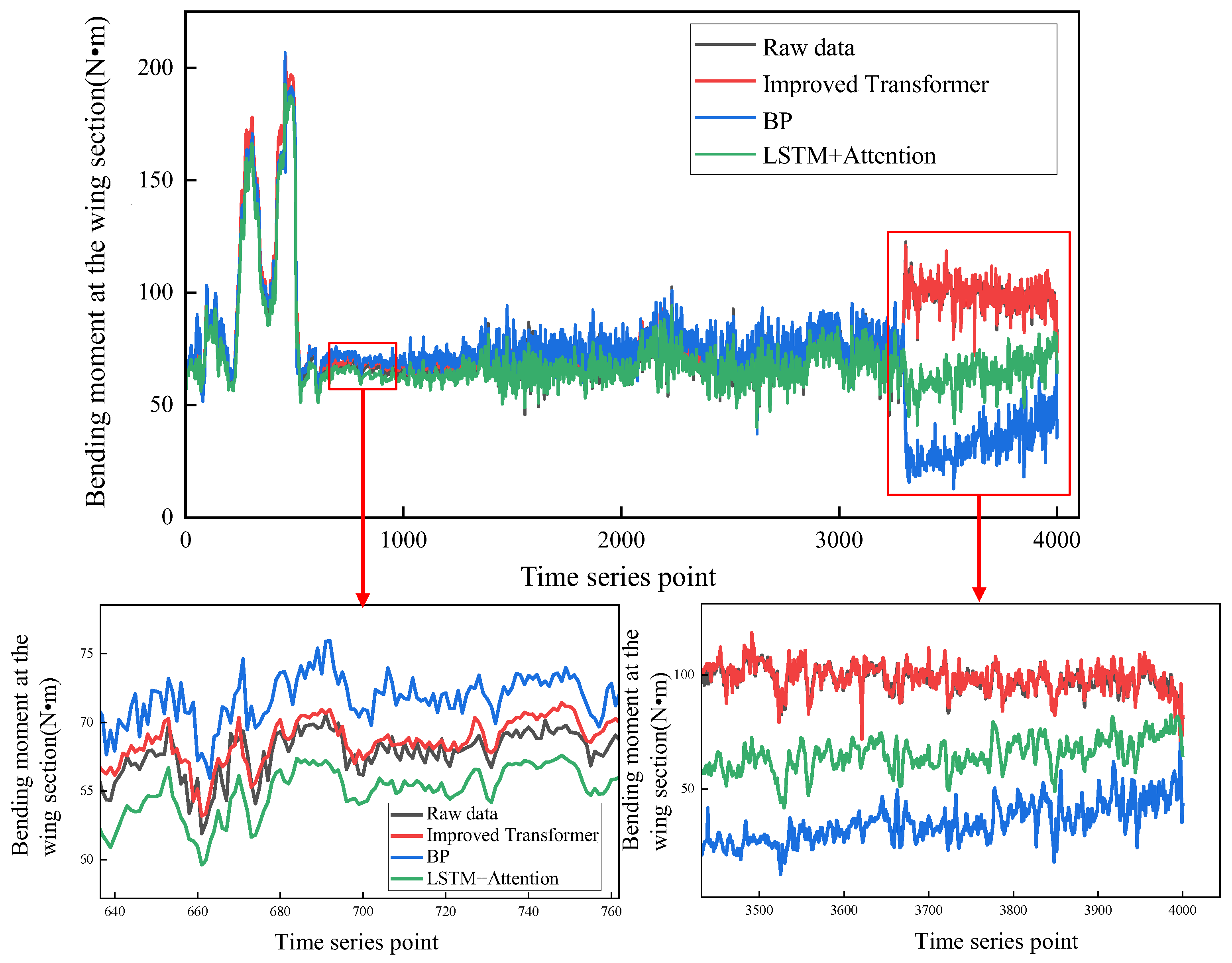

2.3. Aircraft Maneuver Data Prediction

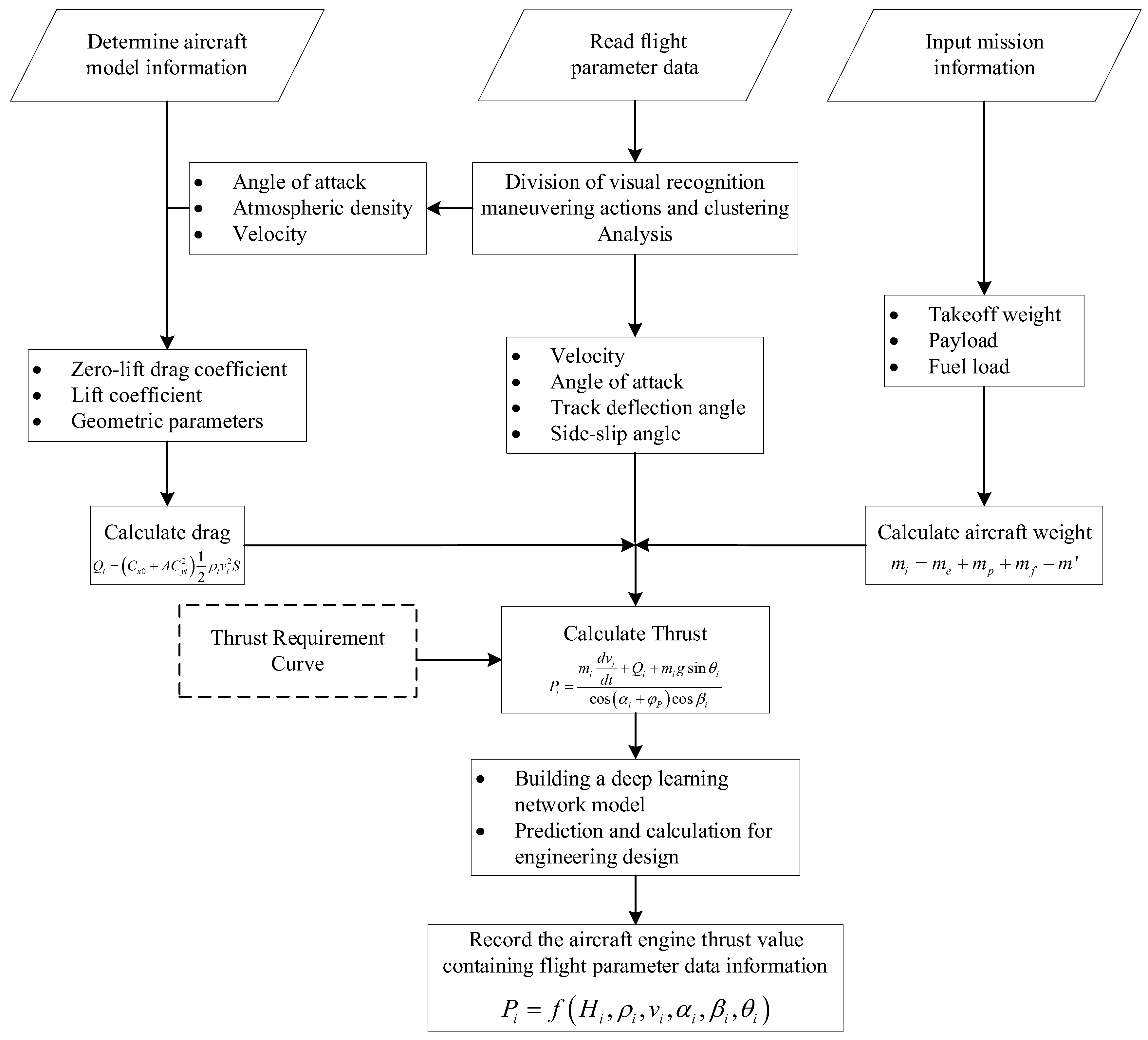

3. Aircraft Thrust Estimation Method

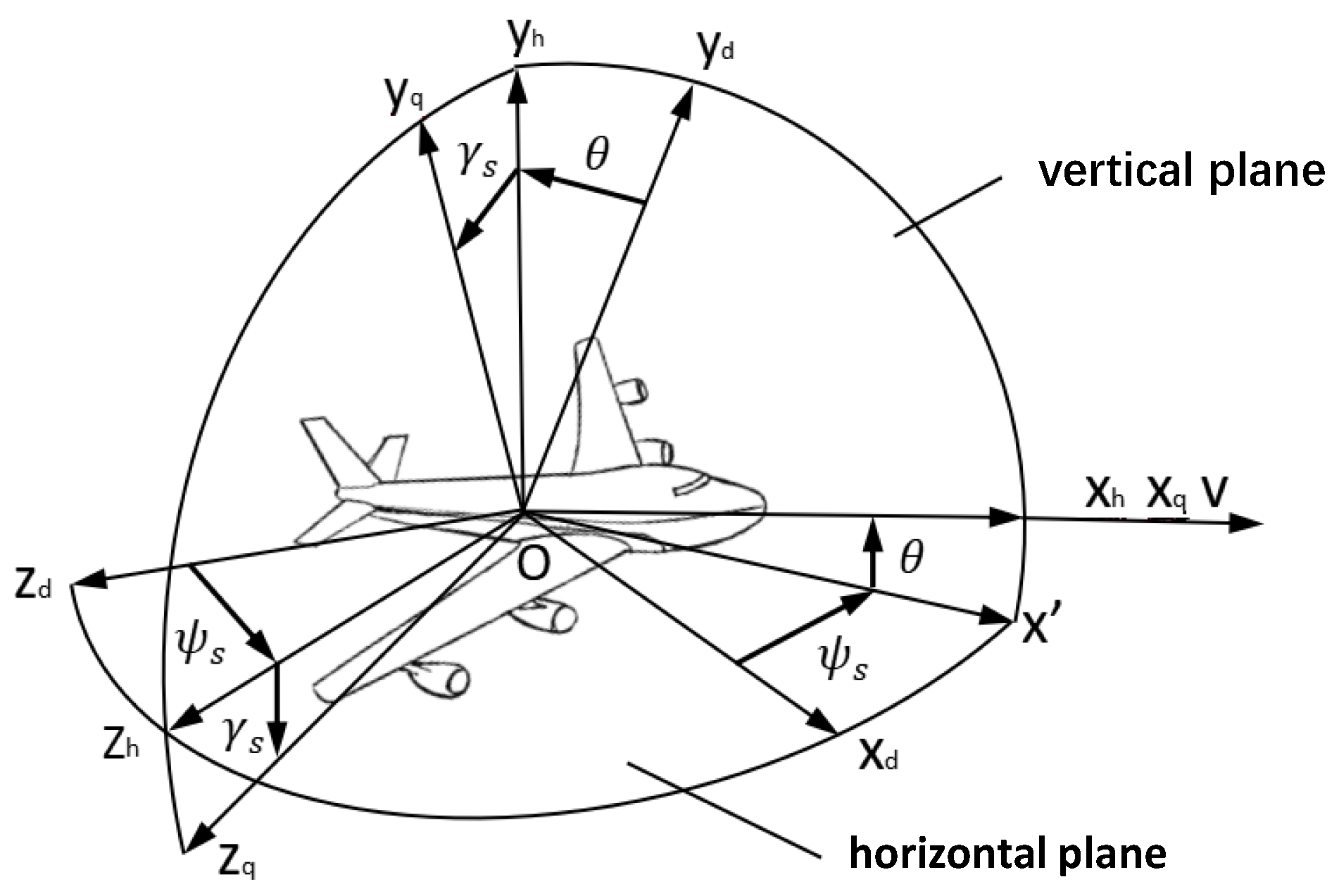

3.1. Aircraft Centroid Dynamic Differential Equations

3.2. Aircraft Requirement Inference and Calculation

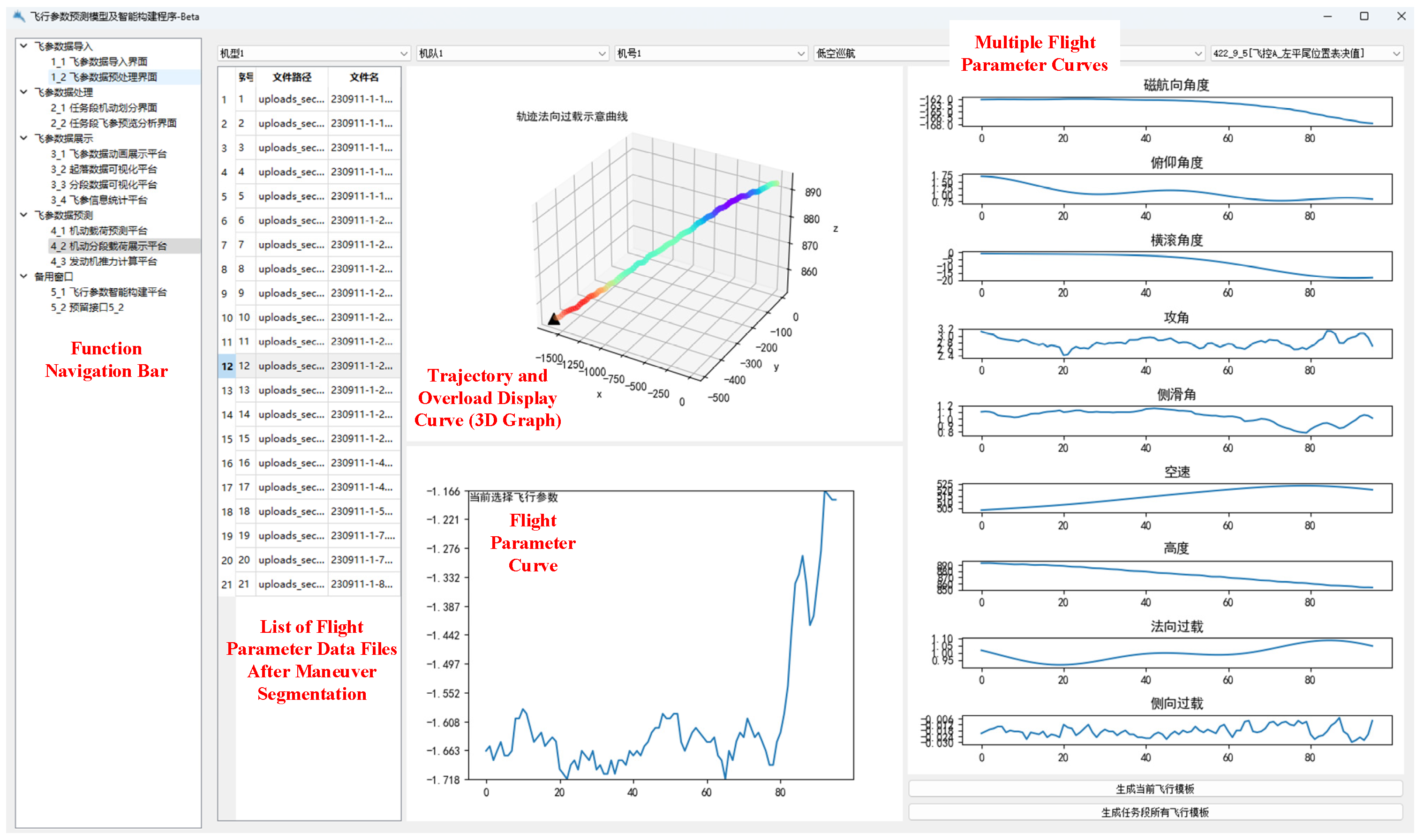

4. Aircraft Required Thrust Design Spectrum Prediction Software

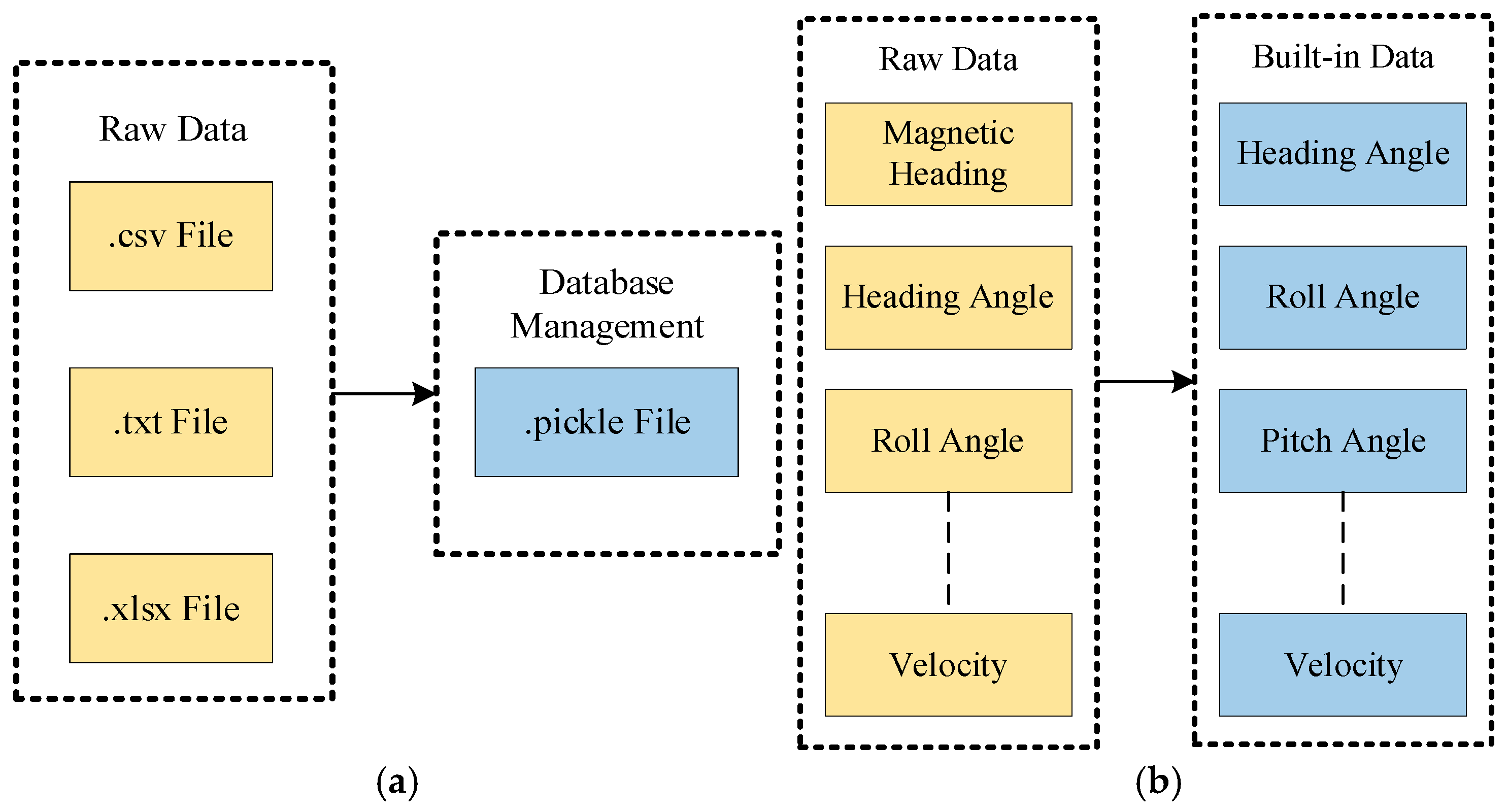

4.1. Flight Parameter Management

4.2. Software Database Management

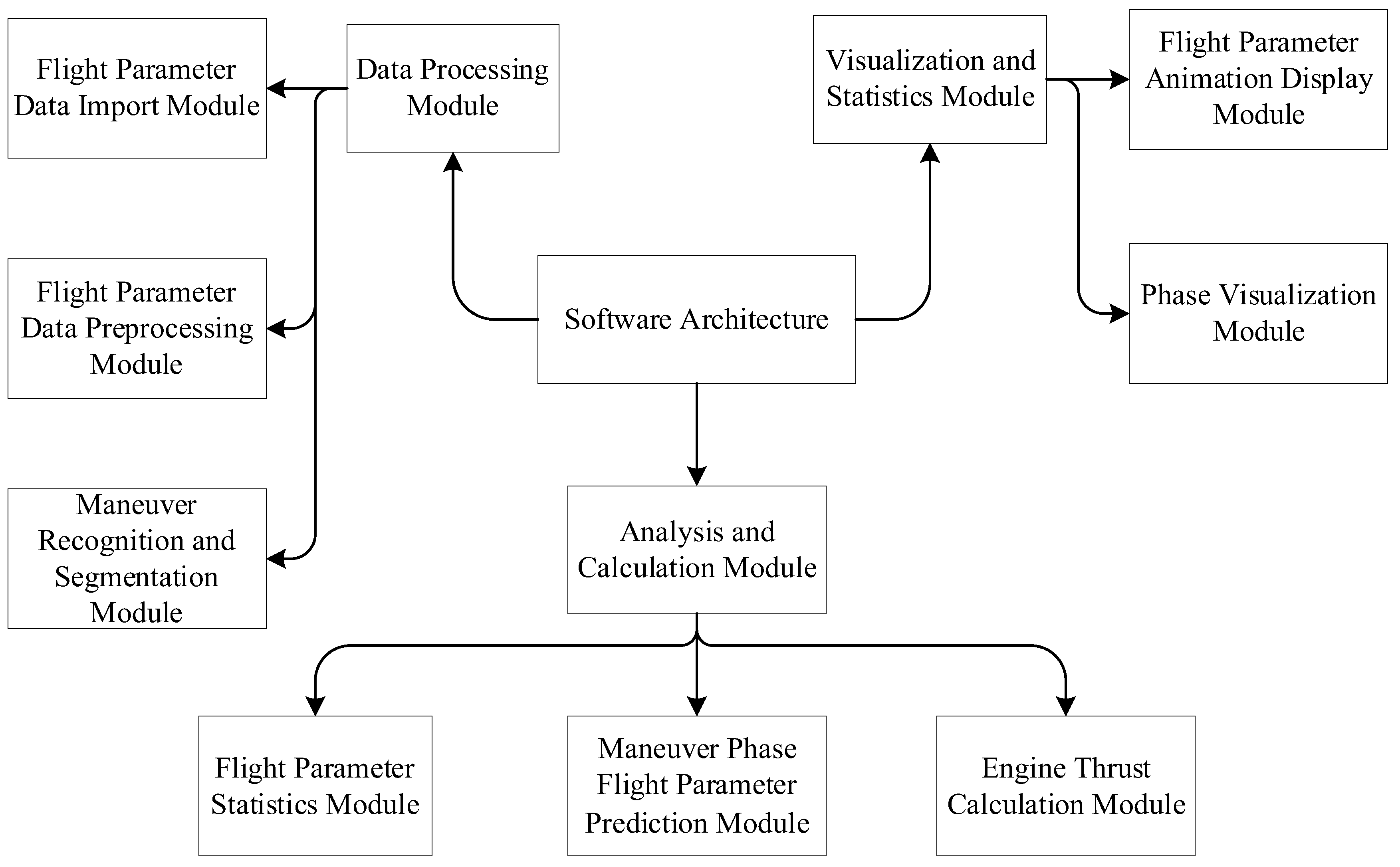

4.3. Software Functional Structure

5. Conclusions

- In terms of flight trajectory and maneuver analysis, trajectory reconstruction was conducted using flight parameters, and aircraft maneuver recognition was accomplished via visual technology, enabling the identification and segmentation of typical flight maneuvers. Compared with traditional algorithms such as PLR-PIP (with an average recognition accuracy of 79.25%), DTW (72.97%), PCA (76.63%), and CTW (56.73%), the vision-based maneuver recognition method proposed in this study achieved an average accuracy of 81.06%.

- By improving the attention mechanism, data input, and model architecture of the traditional Transformer model, the prediction accuracy of the model for flight parameter data has been enhanced. Flight parameter prediction results with low errors can effectively improve the accuracy of engine thrust estimation outcomes.

- A MySQL database and Python-based software system were developed for this framework, with functionalities for thrust/load prediction, trajectory analysis, and performance evaluation.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, W.; Xu, M.; Yang, H.; Wang, X.; Zheng, S.; Li, X. Data-driven deep learning approach for thrust prediction of solid rocket motors. Measurement 2024, 225, 114051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Ding, D.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, L.; Wang, L. A flight maneuver recognition method based on multi-strategy affine canonical time warping. Appl. Soft Comput. 2020, 95, 106527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohout, J. Three-parameter Weibull distribution with upper limit applicable in reliability studies and materials testing. Microelectron. Reliab. 2022, 137, 114769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Shen, X.; Xue, Y.; Liang, H.; Zhang, H. Initial research on impacts of maneuver loads on core engine tip clearance. J. Aerosp. Power 2018, 33, 2205–2218. [Google Scholar]

- Lomax, T.L. Structural Loads Analysis for Commercial Transport Aircraft: Theory and Practice; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Q.; Sun, Z.; Xu, C.; Zhao, S.; Song, Y. A new compilation method of general standard test load spectrum for aircraft engine. Int. J. Turbo Jet-Engines 2022, 39, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Gao, D. Aeroengine composite maneuver loading spectrum derivation. Hangkong Dongli Xuebao/J. Aerosp. Power 2002, 17, 212–216. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, A. Technique of aircraft loads spectrum statistics based on kernel density estimation. J. Beijing Univ. Aeronaut. Astronaut. 2011, 37, 654–657+664. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Xu, J.; Liu, X.; Zheng, Q. Thrust Estimation for Aero-engine Based on Deep Convolution Neural Network. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 752, 012009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazhenov, Y.; Bazhenov, M. Prediction of a residual operating life of engines. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 695, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borguet, S.; Léonard, O. Coupling principal component analysis and Kalman filtering algorithms for on-line aircraft engine diagnostics. Control. Eng. Pract. 2009, 17, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Liu, J.; Guo, H.; Lv, Y.; Tong, C. Sample adaptive aero-engine gas-path performance prognostic model modeling method. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 224, 107072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Jafari, S.; Miran Fashandi, S.A.; Nikolaidis, T. Compressor Degradation Management Strategies for Gas Turbine Aero-Engine Controller Design. Energies 2021, 14, 5711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, T.; Ji, M. Short-Term Prediction Research of Aero-Engine Thrust Deterioration Base on Combined Model. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2018, 8, 1744–1751. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Miao, K.; Sun, J.; Shen, Y.; Han, B. Data-driven modeling of aero-engine performance degradation models. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 150020–150031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Lin, B.; Chen, J.; Wu, X.; Lu, C.; Zheng, D.; Tian, L. Aero-Engine Surge Fault Diagnosis Using Deep Neural Network. Comput. Syst. Sci. Eng. 2022, 42, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hu, Z.; Wang, J. Aero-Engine Real-Time Models and Their Applications. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 9917523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xia, S.; Huang, Y.; Tian, J.; Yin, Z. Research on Engine Thrust and Load Factor Prediction by Novel Flight Maneuver Recognition Based on Flight Test Data. Aerospace 2023, 10, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliff, K.W. Parameter estimation for flight vehicles. J. Guid. Control. Dyn. 1989, 12, 609–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracewell, R.N. The fourier transform. Sci. Am. 1989, 260, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyprianidis, K.G. Future aero engine designs: An evolving vision. In Advances in Gas Turbine Technology; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2011; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sommerville, I. Software Engineering, 9th ed.; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 2011; p. 18. ISBN 0-13-703515-2. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, B.; Zaitsev, P.; Tkachenko, V. High Performance MySQL: Optimization, Backups, and Replication; O’Reilly Media, Inc.: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

| Maneuver | DTW | PCA | CTW | PLR-PIP | Visual Recognition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climb | 75.12 | 80.36 | 64.86 | 86.46 | 88.41 |

| Dive | 70.34 | 77.69 | 39.54 | 87.35 | 91.42 |

| Turn climb | 66.79 | 65.35 | 46.82 | 69.11 | 72.36 |

| Turn Dive | 72.52 | 77.67 | 68.51 | 70.62 | 71.58 |

| Level Flight and Level Turn | 76.36 | 79.34 | 60.33 | 80.97 | 81.56 |

| Average accuracy | 72.97 | 76.63 | 56.73 | 79.25 | 81.06 |

| Model | Whether to Perform Maneuver Recognition | MAE | MSE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP | NO | 15.79 | 361.4 | 0.41 |

| YES | 9.17 | 90.36 | 0.68 | |

| LSTM + Attention | NO | 7.71 | 61.23 | 0.71 |

| YES | 4.10 | 19.59 | 0.87 | |

| Improved Transformer | NO | 4.92 | 29.43 | 0.85 |

| YES | 1.86 | 6.27 | 0.97 |

| Name | Requirements |

|---|---|

| Operating System | Windows 10 |

| Integrated Development Environment (IDE) | Visual Studio Code 1.97 |

| Programming Language Environment | Python 3.9 |

| Database Management System | MySQL 8.0 |

| Desktop Application Development Tool | PyQt |

| Mainly Used Toolkits | PySide5, NumPy 1.25.2, Pandas 2.0.3 |

| Acceptable File Types | csv/.xlsx/.txt |

| Memory Requirements | Minimum 1 GB of RAM and 500 MB of hard disk space |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Du, J.; Mao, S.; Wang, R.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yin, Z. Software System for Thrust Prediction and Preliminary Engineering Design of Aircraft Using Visual Recognition and Flight Parameters. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11770. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111770

Du J, Mao S, Wang R, Ma Y, Zhang M, Yin Z. Software System for Thrust Prediction and Preliminary Engineering Design of Aircraft Using Visual Recognition and Flight Parameters. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(21):11770. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111770

Chicago/Turabian StyleDu, Juan, Senxin Mao, Rui Wang, Yue Ma, Mengchuang Zhang, and Zhiping Yin. 2025. "Software System for Thrust Prediction and Preliminary Engineering Design of Aircraft Using Visual Recognition and Flight Parameters" Applied Sciences 15, no. 21: 11770. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111770

APA StyleDu, J., Mao, S., Wang, R., Ma, Y., Zhang, M., & Yin, Z. (2025). Software System for Thrust Prediction and Preliminary Engineering Design of Aircraft Using Visual Recognition and Flight Parameters. Applied Sciences, 15(21), 11770. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111770