Comparative Study of Continuous Versus Discontinuous Numerical Models for Railway Vehicles Suspensions with Dry Friction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Dry Friction in Mechanical Systems

2.2. Static vs. Kinetic Friction, Stick–Slip Transitions

2.3. Continuous and Discontinuous Approaches

- Regularized models, which ensure continuity but lead to stiff differential equations and neglect true stick phases.

2.4. Event-Driven Algorithms

- Initialize the system, determine the next smooth mode, and update the equations.

- Integrate the smooth state vector with any ODE solver while constraints are not violated.

- Detect within imposed tolerance the moment of the next event.

2.4.1. Event Detection

2.4.2. Mode Selection and Integration of a Smooth Mode

3. Modelling Approaches

3.1. Suspension System Model

3.2. Continuous Model

3.3. Discontinuous Model

3.4. Comparative Methodology

- Physical representation: How well does the model capture stick–slip phases?

- Stability: Solver tolerance dependence, stiffness, and integration time.

- Computation time: Computational cost of simulating the system in execution time.

- Predictive power: Reproduce some stable and time-dependent oscillations with different parameters.

4. Numerical Simulation and Results

4.1. Simulation Setup

- Continuous model: friction represented by a tanh-based regularization.

- Discontinuous model: friction represented by a switch model with explicit stick–slip detection.

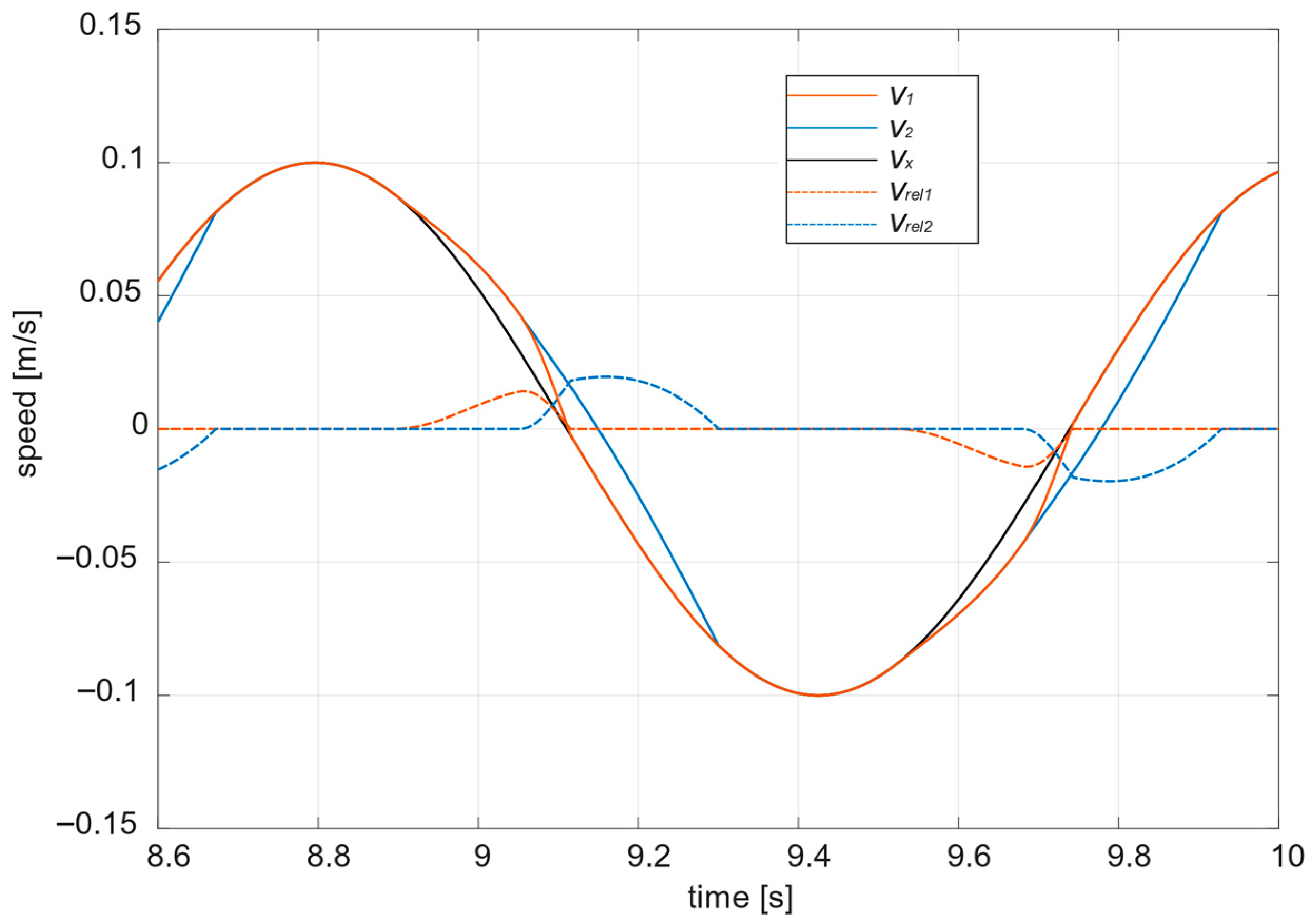

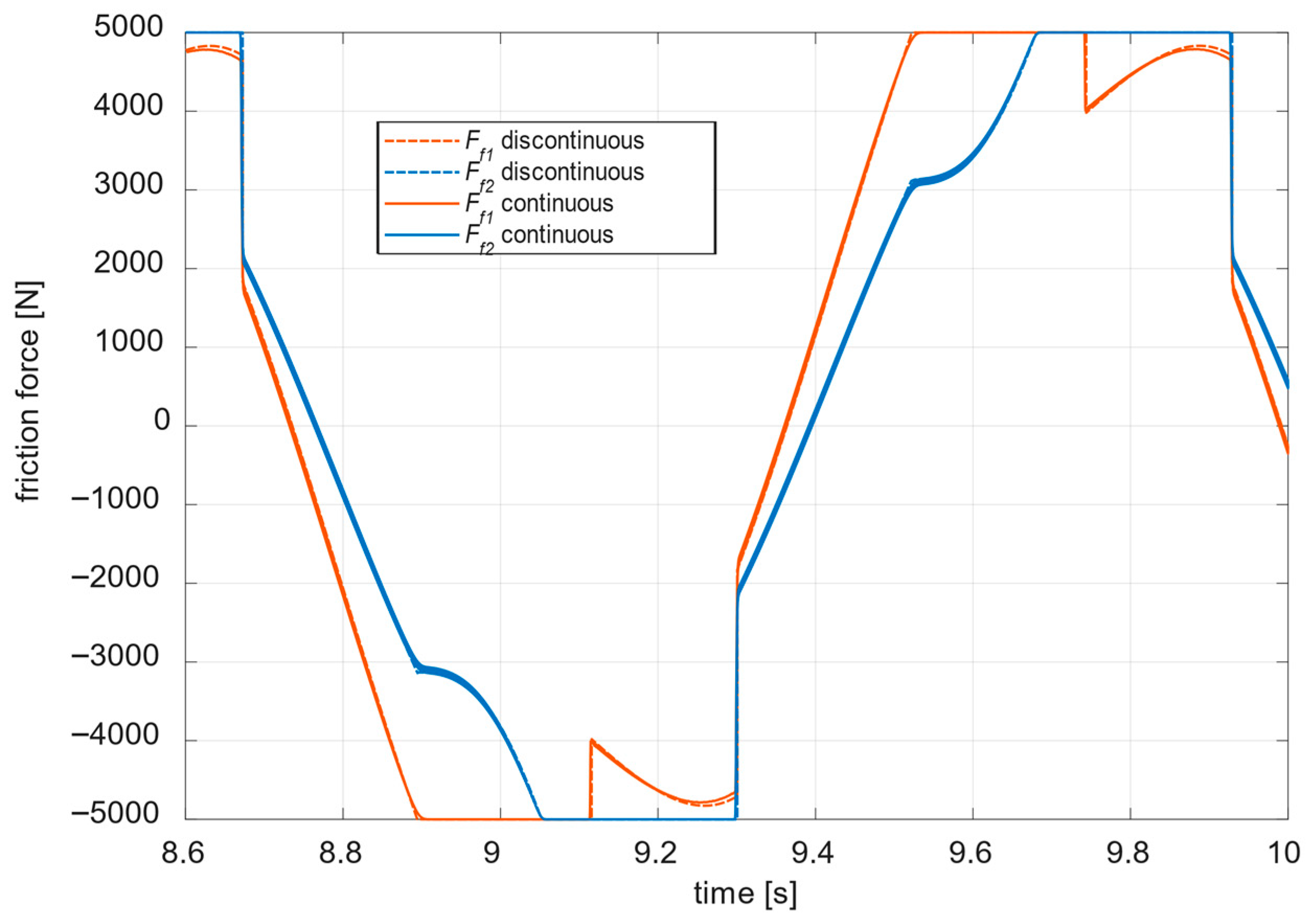

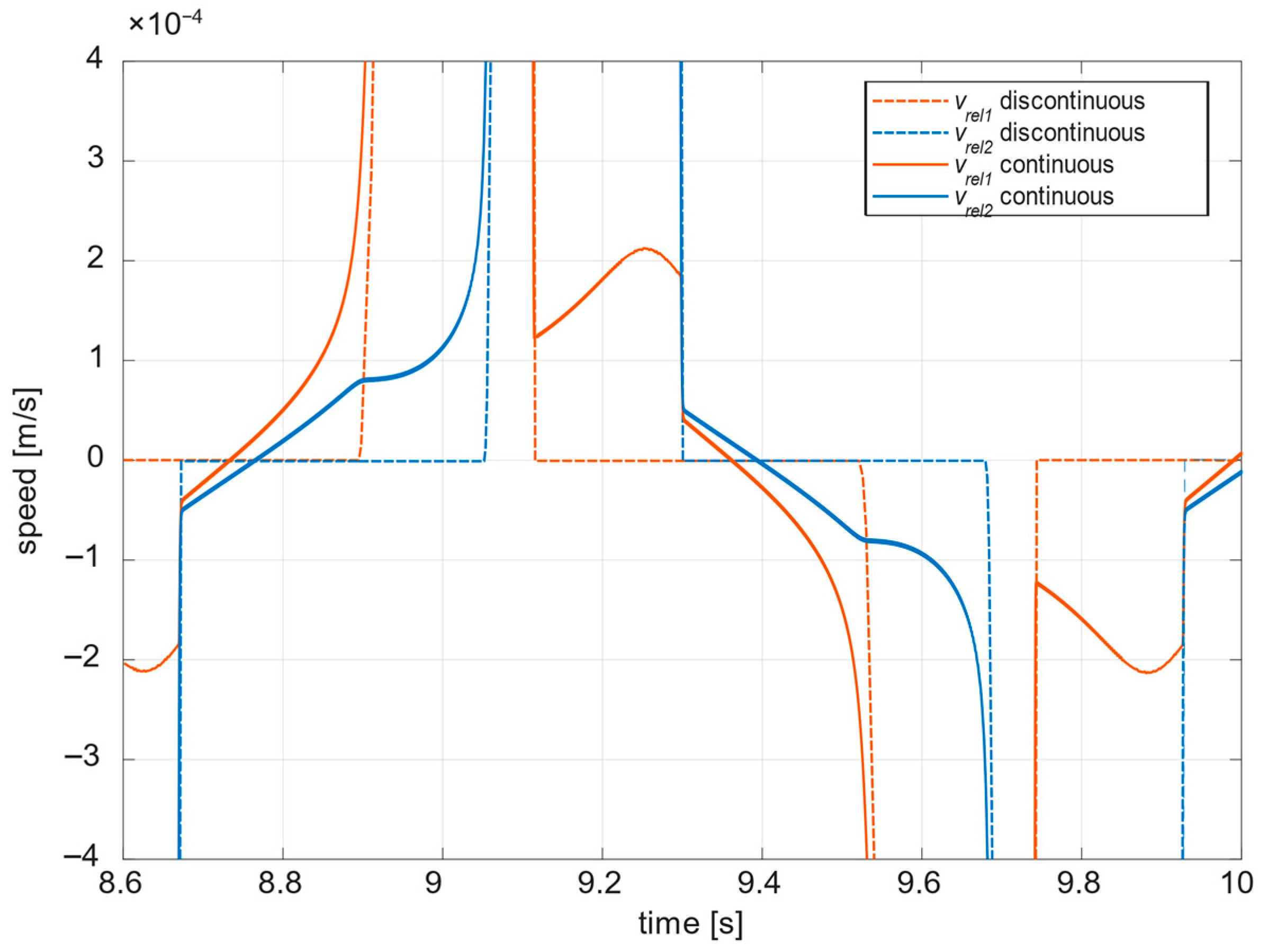

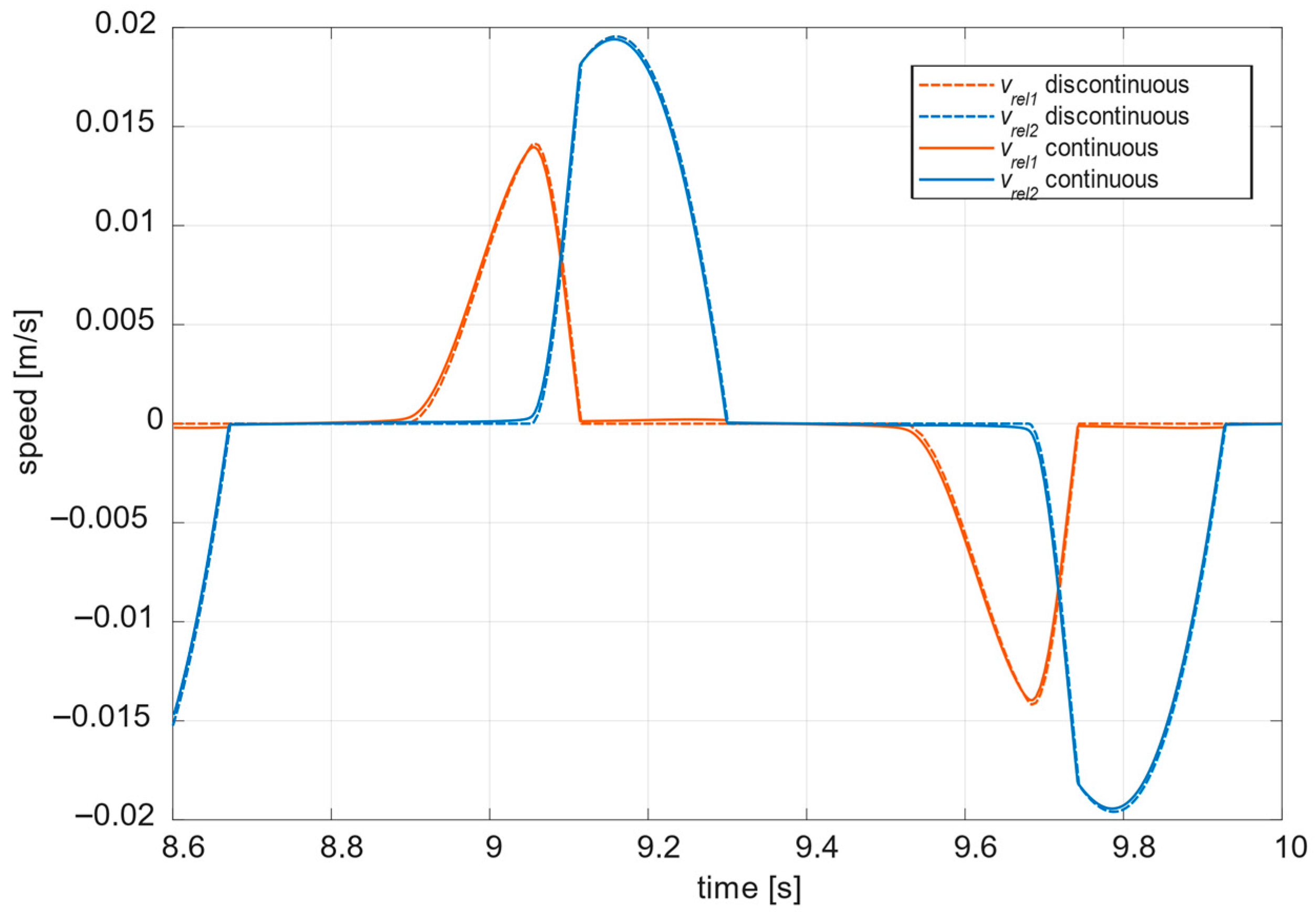

4.2. Results: Discontinuous Model

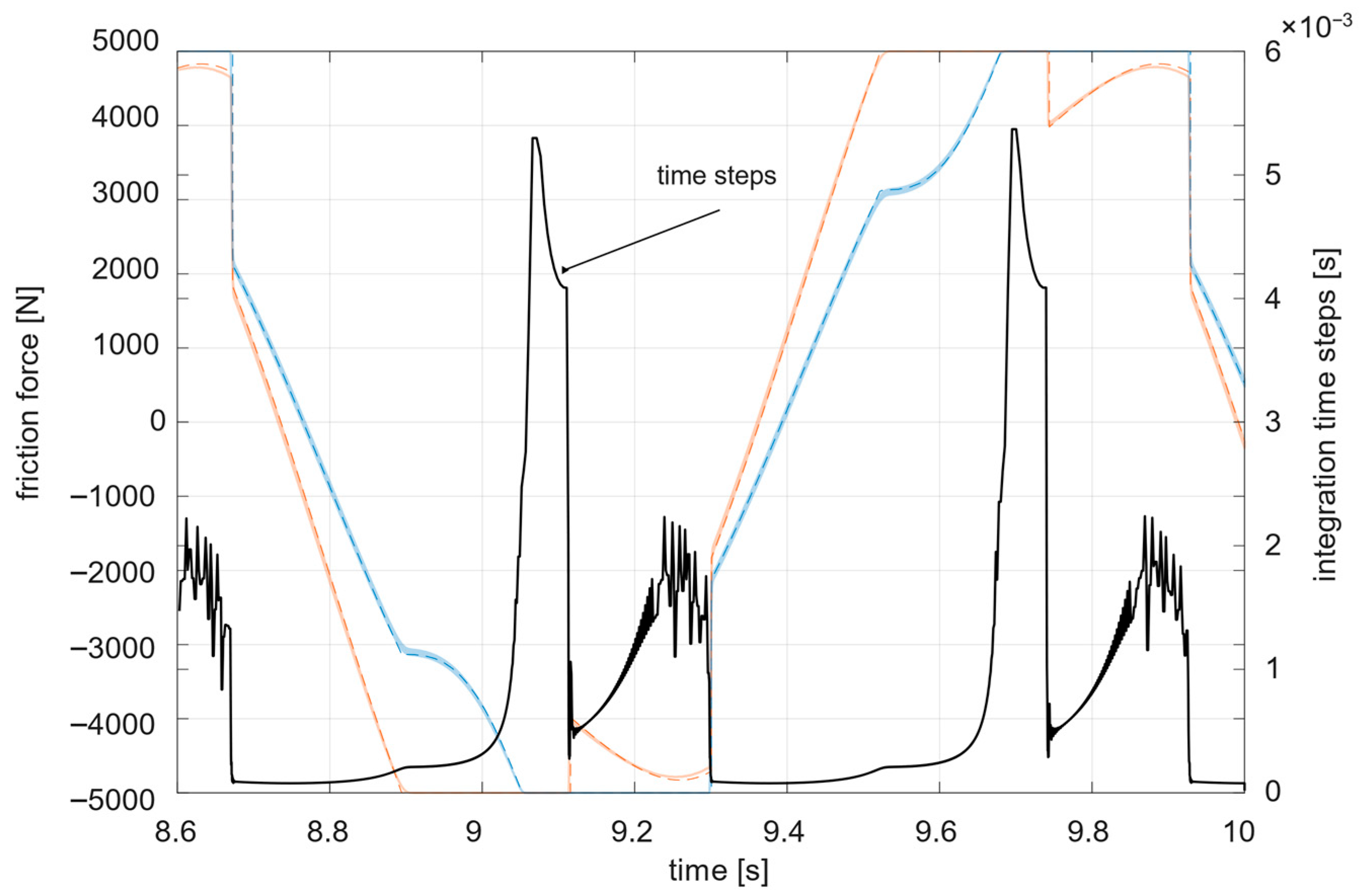

4.3. Results: Continuous Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Alternative Approaches

- The regularized approach, which smoothens the discontinuity at zero slip velocity.

- The non-smooth approach, which retains discontinuities and better captures stick–slip transitions.

5.2. Stick–Slip Oscillations and Mathematical Structure

- Set-valued/non-smooth models: these treat friction as a multivalued function at zero velocity (e.g., friction force in a range when velocity is zero), which is inherent in non-smooth mechanics.

- Switch models: models that switch laws depending on the regime (stick vs. slip), possibly also depending on additional state variables or thresholds. These are efficient in capturing realistic behaviour with reduced computational overhead when compared to finely regularized/hybrid continuous approximations.

- Karnopp model: introduces a finite “stick band” with threshold . For , the state is “stick”; outside, slip. This allows for handling stick–slip without infinitely sharp transitions.

5.3. Comparative Analysis

5.4. Potential Implementations of Hybrid Modelling Strategies

- Firstly, a hybrid complementarity regularization which couples a mathematical programming-based (complementarity) solver for the discontinuous regime with a regularized ODE solver for smooth phases based on the following approach:

- Express friction laws as inequalities.

- Use a Mixed Linear Complementarity Problem formulation when discontinuities are active.

- Otherwise, integrate with standard ODE solvers.

- Secondly, a machine learning-assisted hybrid model using data-driven algorithms to emulate parts of the friction law where analytical models fail or are computationally demanding. The implementation should include the following processes:

- Train a neural network or regression model to approximate the friction–velocity relationship in transition regions.

- Embed the learned model into a physics-based framework that governs overall system dynamics.

6. Conclusions

- Continuous models are simple to implement but require stiff solvers, exhibit numerical instability, and fail to capture true stick–slip dynamics.

- Discontinuous models accurately reproduce stick intervals and allow for distinguishing stick and slip periods even with a wide stick band while being computationally efficient.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Knothe, K.; Stichel, S. Railway Vehicle Dynamics: Fundamentals and Advanced Applications; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Melnik, R.; Koziak, S.; Seńko, J.; Dižo, J.; Caban, J. Evaluation of Dynamics of a Freight Wagon Model with Viscous Damping. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millan, P.; Pagaimo, J.; Magalhães, H.; Antunes, P.; Ambrósio, J. Influence of the friction modelling decisions on the acceptance of the running behaviour of a friction-damped locomotive. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2023, 62, 719–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Wang, L. Oblique impact dynamic analysis of wedge friction damper with Dankowicz dynamic friction. Electron. Res. Arch. 2024, 32, 962–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jia, M.; Zhang, G.; Luo, H.; Huang, Y. Improved design and performance analysis of vibration damping device for railway freight bogie. Int. J. Rail Transp. 2023, 12, 368–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solonenko, V.G.; Musayev, J.S.; Makhmetova, N.M.; Malik, A.A.; Yermoldina, G.T.; Akhatov, S.T.; Ivanovtseva, N.V. Dynamic Analysis of Railway Vehicle–Track Interaction: Modelling Elastic–Viscous Track Properties and Experimental Validation. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- True, H.; Thomsen, P.G. Non-Smooth Problems in Vehicle Systems Dynamics, Proceedings of the Euromech 500 Colloquium, EUROMECH 500; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Popa, G.; Andrei, M.; Tudor, E.; Vasile, I.; Ilie, G. Fast Detection of the Stick–Slip Phenomenon Associated with Wheel-to-Rail Sliding Using Acceleration Sensors: An Experimental Study. Technologies 2024, 12, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreaus, U.; Casini, P. Dynamics of Friction Oscillators Excited by a Moving Base and/or Driving Force. J. Sound Vib. 2001, 245, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oprea, R.A.; Tudorache, C.M.; Spiroiu, M.A. Efficient Wheel-Rail Stick-Slip Numerical Modelling for Railway Traction Vehicles. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Tian, Q.; Hu, H. Nonsmooth spatial frictional contact dynamics of multibody systems. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 2021, 53, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, P.; Li, D.; Yue, Y. Two-parameter dynamics and multistability of a non-smooth railway wheelset system with dry friction damping. Chaos 2024, 34, 113118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Jaafar, S.A.; Zhou, W.; Yan, H.; Chen, J.; Meng, X. Wheel-rail contact and friction models: A review of recent advances. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit. 2023, 237, 1245–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antali, M. Dynamics of Railway Wheelsets with a Nonsmooth Contact Force Model. In Proceedings of the Perspectives in Dynamical Systems II—Numerical and Analytical Approaches, DSTA 2021, Łódź, Poland, 6–9 December 2021; Awrejcewicz, J., Ed.; Springer Proceedings in Mathematics & Statistics. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, P.; Li, D.; Yin, S.; Xie, J.; Grebogi, C.; Yue, Y. Double grazing bifurcations of the non-smooth railway wheelset systems. Nonlinear Dyn. 2022, 111, 2093–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oprea, R.A.; Cruceanu, C.; Spiroiu, M.A. Alternative friction models for braking train dynamics. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2012, 51, 460–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuderer, M.; Rill, G.; Schaeffer, T.; Schulz, C. Friction modelling from a practical point of view. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 2025, 63, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millan, P.; Pagaimo, J.; Magalhães, H.; Ambrósio, J. Clearance joints and friction models for the modelling of friction damped railway freight vehicles. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 2023, 58, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollebregt, E.A.H.; van der Wekken, N. Advanced Modelling of Wheel-Rail Friction Phenomena; FRA Report; Department of Transportation, Federal Railroad Administration, Office of Railroad Policy and Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Coble, D.; Cao, L.; Downey, A.R.J.; Ricles, J.M. Physics-informed machine learning for dry friction and backlash modelling in structural control systems. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 218, 111522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deubel, C.; Schubert, B.; Prokop, G. Velocity and load dependent dynamic shock absorber friction at stationary conditions. Tribol. Int. 2024, 193, 109424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamato, G.; Solazzi, M.; Frisoli, A. Investigating the effect of dry friction on damage detection and dynamic response. J. Sound Vib. Struct. Dyn. 2024, 2024, 117949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinin, Y.; Koliesnik, I.; Demianyshyn, V.; Koliesnik, J. Evaluation of the Influence of a Dry Friction Damper on the Vibrations of a System with a Pendulum Suspension. In Proceedings of the Innovations in Mechanical Engineering IV, ICIENG 2025, Prague, Czech Republic, 18–20 June 2025; Machado, J., Trojanowska, J., Ottaviano, E., Xavior, M.A., Valášek, P., Basova, Y., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dănăilă, S.; Moraru, L. On the validity of the classical hydrodynamic lubrication theory applied to squeeze film dampers. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2010, 12, 012104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specker, T.; Buchholz, M.; Dietmayer, K. A New Approach of Dynamic Friction Modelling for Simulation and Observation. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2014, 47, 4523–4528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorge, F. Forced Stick-Slip Oscillations of Two-Degree-of-Freedom Systems with Dry-Viscous Dissipation and Time-Dependent Static Friction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Tribology, Parma, Italy, 20–22 September 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Karnopp, D. Computer simulation of slip-stick friction in mechanical dynamic systems. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control. 1985, 107, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogliato, B.; ten Dam, A.A.; Paoli, L.; Génot, F.; Abadie, M. Numerical simulation of finite dimensional multibody nonsmooth mechanical systems. ASME Appl. Mech. Rev. 2002, 55, 107–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leine, R.I.; Nijmeijer, H. Dynamics and Bifurcations of Non-Smooth Mechanical Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, S.; Soderberg, A.; Bjorklund, S. Friction models for sliding dry, boundary and mixed lubricated contacts. Tribol. Int. 2007, 40, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobre, A.; Andreescu, C.N.; Stan, C. The influence of the current intensity on the damping characteristics for a magneto-rheological damper of passenger cars. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 7th International Conference on Advanced Concepts in Mechanical Engineering, Iasi, Romania, 9–10 June 2016; Volume 147. [Google Scholar]

- Mihailescu, I.M.; Popa, G.; Oprea, R.A. Detection of Defects in The Railway Track That Can Influence Traffic Safety Using the Method of Vibration Analysis of Vehicle-Rail System. Acta Tech. Napoc. Appl. Math. Mech. Eng. 2022, 65, 1241–1248. [Google Scholar]

- Ilosvai, L.; Szucs, B. Random Vehicle Vibrations as Effected by Dry Friction in Wheel Suspensions. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 1972, 1, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csernak, G.; Stepan, G. On the periodic response of a harmonically excited dry friction oscillator. J. Sound Vib. 2006, 295, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- True, H.; Asmund, R. The Dynamics of a Railway Freight Wagon Wheelset with Dry Friction Damping. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2003, 38, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leine, R.; van Campen, D.; de Kraker, A.; van den Steen, L. Stick-Slip Vibrations Induced by Alternate Friction Models. Nonlinear Dyn. 1998, 16, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auersch, L. Vehicle Dynamics and Train-Induced Ground Vibration—Theoretical Analyses and Simultaneous Vehicle, Track, and Soil Measurements. Vehicles 2023, 5, 223–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Description | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bogie mass | m1 | 3000 | kg |

| Half carbody mass | m2 | 10,000 | kg |

| Primary suspension rigidity | k1 | 2.5 | kN/mm |

| Secondary suspension rigidity | k2 | 2.5 | kN/mm |

| Saturation creep limit | η | 10−4–10−6 | m/s |

| Maximum static friction, primary suspension | 5000 | N | |

| Maximum static friction, secondary suspension | 5000 | N | |

| Friction parameter | C | 9000 | s/m |

| Regularized slip force magnitude, primary suspension | 5000 | N | |

| Regularized slip force magnitude, secondary suspension | 5000 | N | |

| Track irregularities amplitude | A | 2/20 | mm |

| Track irregularities frequency | ω | 1–100 | rad/s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oprea, R.A.; Tudorache, C.M.; Spiroiu, M.A.; Arsene, S.; Craciun, C.I. Comparative Study of Continuous Versus Discontinuous Numerical Models for Railway Vehicles Suspensions with Dry Friction. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11769. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111769

Oprea RA, Tudorache CM, Spiroiu MA, Arsene S, Craciun CI. Comparative Study of Continuous Versus Discontinuous Numerical Models for Railway Vehicles Suspensions with Dry Friction. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(21):11769. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111769

Chicago/Turabian StyleOprea, Razvan Andrei, Cristina Mihaela Tudorache, Marius Adrian Spiroiu, Sorin Arsene, and Camil Ion Craciun. 2025. "Comparative Study of Continuous Versus Discontinuous Numerical Models for Railway Vehicles Suspensions with Dry Friction" Applied Sciences 15, no. 21: 11769. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111769

APA StyleOprea, R. A., Tudorache, C. M., Spiroiu, M. A., Arsene, S., & Craciun, C. I. (2025). Comparative Study of Continuous Versus Discontinuous Numerical Models for Railway Vehicles Suspensions with Dry Friction. Applied Sciences, 15(21), 11769. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111769