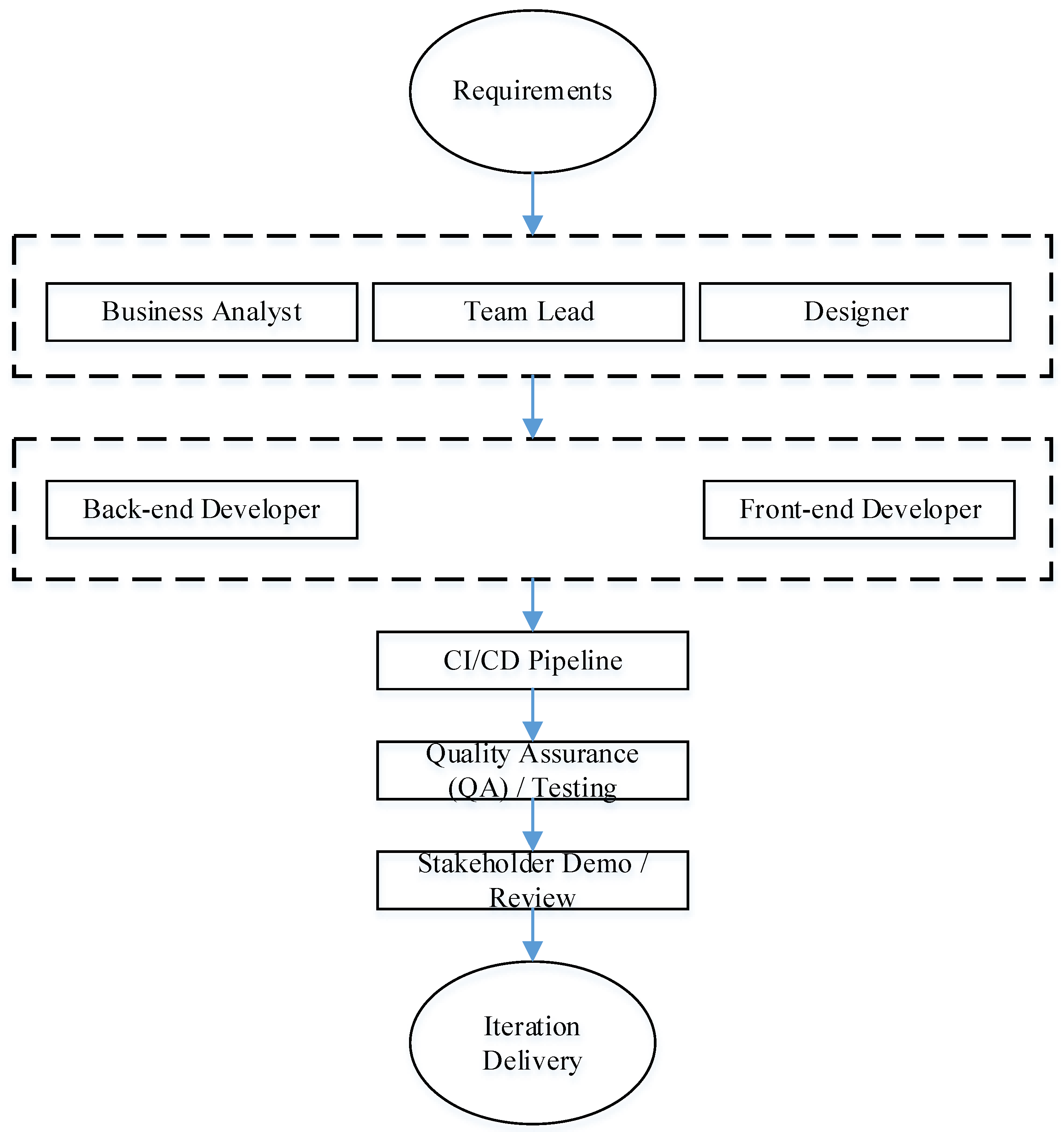

2.2. Hybrid Project Management Algorithm with AI Elements

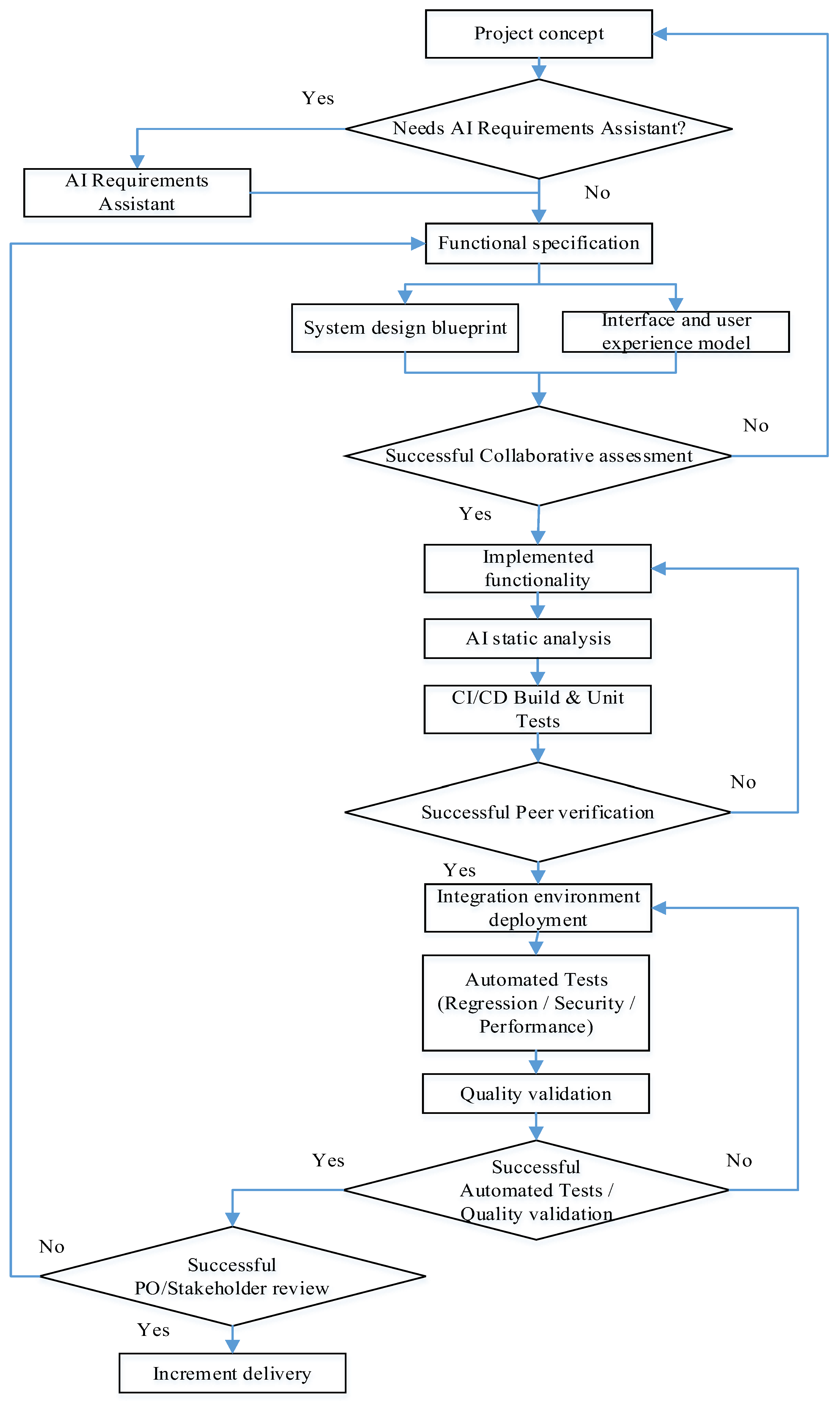

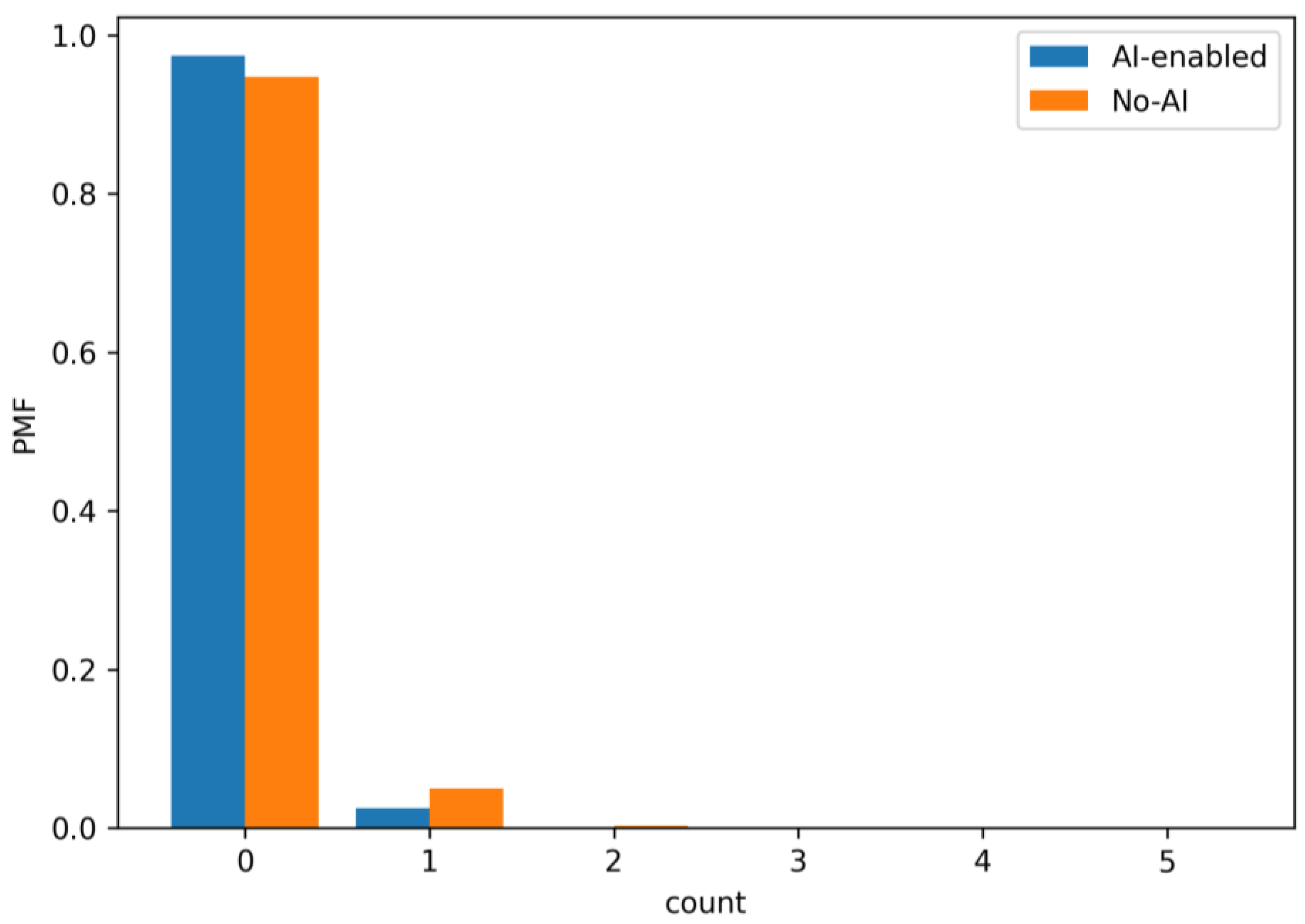

Having summarized the structure of the development team, it is advisable to move from the organizational description to the operational outline of the process, “from the concept of functionality to the delivery of the increment”. For further formalization in GERT terms, a representative process diagram is required, which clearly reflects the control conditions for decision-making, addressable feedback loops, as well as modern IT practices. First of all, a CI/CD pipeline, the separation of automated and manual quality checks, and the optional involvement of AI tools to reinforce individual steps. The updated functionality development life cycle diagram agreed upon by us (see

Figure 2) serves as a reference model for further mathematical description: its nodes and transitions are further interpreted as vertices and arcs of the GERT network with the corresponding probabilities of passage from node to node, as well as duration distributions.

Drawing on [

21,

22] and Agile/DevOps practices, we present a detailed description of the updated feature development flow consistent with the figure. The model reflects the iterative nature of development, combining the classic phases of analysis, design, implementation, and verification with modern automation tools (CI/CD) and decision-making checkpoints, and also supports addressable rework loops.

The life cycle begins with the conceptualization stage (Project concept), which articulates the business value and expected effects of the new functionality. Then, if necessary, the AI Requirements Assistant is involved as an auxiliary tool to clarify formulations, identify contradictions, and prepare initial usage scenarios. The use of AI is not a mandatory phase of the flow. It acts as an amplifier of the quality of requirements, not a separate mandatory step. The result of this block is the Functional specification. This is a formalized description of the requirements with acceptance criteria, non-functional constraints, and assumptions. It is the only source of truth for subsequent work.

Based on an agreed specification, two complementary design lines are deployed in parallel.

The first is the System design blueprint. It covers the choice of architectural solutions, component interaction contracts, security policies, and data management. The Team Lead is responsible for the integrity of the architecture.

The second is the Interface and user experience model. It creates the interface information architecture, screen layouts, and interaction rules that ensure ergonomics and predictability of the user experience. The consistency of these artifacts is recorded at the decision-making checkpoint Successful Collaborative assessment. In the case of a positive decision, the process moves to implementation. If gaps in requirements, UX risks, or architectural discrepancies are identified, targeted returns are initiated to the artifact where the problem occurred (specification, UX, or system design). Such targeted returns minimize the amount of rework and reduce cycle time.

The implementation phase begins with the creation of the Implemented functionality increment by the front-end and back-end developers (FE/BE) under the technical guidance of the Team Lead.

Immediately after writing the code, AI static analysis is performed. Static analysis tools (including AI-enhanced hints) perform linting, identify potential vulnerabilities (SAST), stylistic and anti-patterns. Early detection of defects in the code fundamentally reduces the cost of their removal and reduces the load on subsequent stages.

The increment then goes to CI/CD Build and Unit Tests. The continuous integration pipeline builds the project, runs unit tests, and basic artifact quality checks, ensuring reproducibility and traceability of builds.

After automated checks, the quality of the code is confirmed by “human” control Successful Peer verification (formalized code review). This assesses compliance with architectural rules, coding standards, and change requirements.

If the decision is positive, the increment is deployed to the Integration environment deployment, where the relevant infrastructure parameters are recreated (IaC approach). In case of failure, a managed rollback to the implemented functionality is performed for refinement while preserving all review artifacts, ensuring transparency of the reasons for the rollback.

A full suite of Automated Tests (Regression/Security/Performance) is launched in the integration environment, which includes regression, security (DAST/SCA), and load/performance tests. After this, Quality validation is performed—manual validation by testers of end-to-end scenarios, verification of negative cases, and non-functional requirements. The results of automated and manual tests are consolidated into decision-making checkpoints Successful Automated Tests/Quality validation. In case of failure, an addressed return is activated, usually to implement functionality (to correct defects), and when the source of the deviation is errors in the requirements or UX solutions, then to the Functional specification or Interface and user experience mode. Such a return policy ensures a cause-and-effect correspondence between the defect and the point of its elimination.

The final part of the flow is the Successful PO/Stakeholder review. The increment is demonstrated to stakeholders, and the Product Owner, compliance with business expectations is assessed, and readiness for delivery is determined. If the decision is positive, Increment delivery is performed, which records the completion of the iteration and forms the basis for the next cycle of continuous functionality enhancement. In the case of comments from stakeholders, the flow returns to the level of the requirements specification and/or UX model for prompt clarification and repeated passage of quality checkpoints.

2.3. Mathematical Model of the Software Development Process

We mathematically formalize the software development process. To do this, we will use the GERT modeling technology [

23,

24,

25,

26].

From the perspective of further formalization based on the GERT network, each transition between states is considered as an arc with a probability of successfully passing checkpoints and a duration distribution that reflects the complexity and involvement of roles. The intensity of team participation is naturally interpreted through the “weights” of the arcs: collective reviews (collaborative assessment, peer review) have a higher involvement coefficient than individual actions (for example, deployment or individual automated steps), and the effect of CI/CD and AI tools is manifested in a decrease in the duration parameters and/or the probability of return. Due to this, the updated scheme not only describes the process at the engineering level but also serves as a ready-made basis for quantitative analysis: assessing the expected iteration time, variability, probability of deadline insertion, and sensitivity to the level of automation and the quality of requirements and design artifacts.

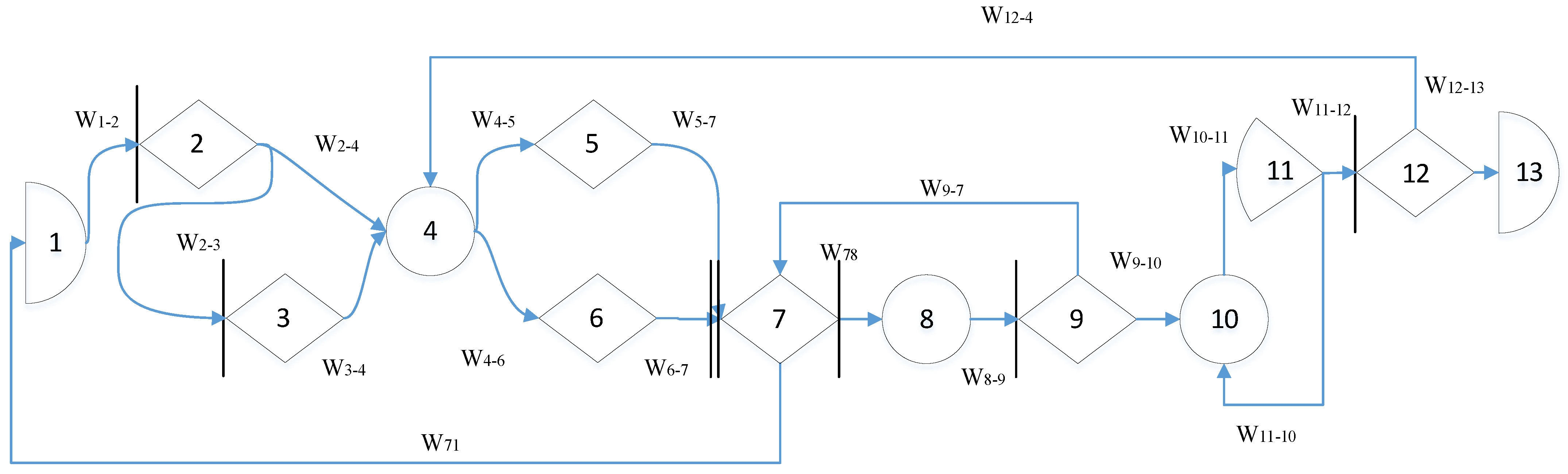

In

Figure 3 the GERT scheme of the software development process is presented.

The model is considered as a directed probabilistic graph G = (V,E) with a set of nodes V = {1,…,13} and a set of arcs E ⊆ V × V. Each arc Wij specifies the probability of passing pij and the duration (or cost) distribution Tij. For decision nodes, the sum of the probabilities of the output arcs is equal to one. Node 7 has input logic I-AND (triggered only after receiving results from nodes 5 and 6), and the output logic in all decision nodes is O-OR.

The process starts at node 1 (Project concept) and, with a mandatory transition, W12 moves to node 2, where a decision is made on the need for an AI requirements assistant. If the option “Yes” is selected, node 3 (AI Requirements Assistant) is executed with a transition W34 to the specification. In this step, the assistant structures the informal requirements of stakeholders into requirements artifacts (user stories, acceptance criteria, non-functional constraints), eliminates contradictions, and forms traceability traces.

It should be noted that this transition models a conscious choice to use the AI Requirements Assistant module as a preliminary stage of formalization. Semantically, this is the probabilistic output of the decision node 2. p2−3 is normalized together with p24 (p23 + p24 = 1) and calibrated by design factors (degree of unstructuredness of the elicitation input materials, novelty of the subject area, multilinguality of the sources, pronounced security restrictions, maturity of the team). The time costs of the transition itself are considered negligibly small (decision), and the main duration is taken into account at the next stage of processing (node 3). Selecting the W23 branch activates the AI assistance procedures, normalization and deduplication of stakeholder statements, detection and resolution of contradictions, extraction of entities and relationships (glossary, NFR classification), generation of user stories and acceptance criteria, and construction of the initial traceability matrix. The result is an agreed package of requirements artifacts, which is then transmitted by the W34 arc to node 4. Empirically, its application reduces the expected value of E[T3−4] and subsequent returns at later stages (in particular, p9−7 and p12−4, which affects the total cycle time and the probability of reaching the terminal node 13.

If the option is “No”, W2−4 is activated, and the process bypasses node 3, moving directly to node 4 (Functional specification). Node 4 consolidates the requirements into a single document that serves as the source of truth for the following stages.

From the specification, the branching occurs in parallel, arcs W45 and W46, respectively, trigger node 5 (System design blueprint), where the architecture, module interfaces, data model, and security aspects are processed, and node 6 (Interface and UX model), where interaction flows and user interface prototypes are designed. Both flows must be completed, after which their results converge in node 7 (Successful Collaborative assessment). This is a synchronous node with input logic I-AND; it is triggered only if artifacts 5 and 6 are present.

To make the implicit-AND (I-AND) join and feedback reduction concrete for readers unfamiliar with GERT, we include a short pseudocode recipe that reduces a minimal subnetwork with one feedback loop and a parallel I-AND join. The recipe works at the level of the first two moments (mean and variance) and is fully consistent with the semantics introduced above.

function GeometricLoopReduce(mu, var, p):

# total time until first success (geometric number of attempts)

mu_eq = mu/p

var_eq = var/p + (1 − p)/(p^2) * (mu^2)

return mu_eq, var_eq

# Main reduction: parallel I-AND with one feedback loop on A

# Inputs: mu_A, var_A, p_A, mu_B, var_B, rho # set rho = 0 if unknown

function IAND_Reduce(mu_A, var_A, p_A, mu_B, var_B, rho = 0):

(mu_A_eq, var_A_eq) = GeometricLoopReduce(mu_A, var_A, p_A)

# If branch B also has a loop, replace with:

# (mu_B_eq, var_B_eq) = GeometricLoopReduce(mu_B, var_B, p_B)

mu_B_eq = mu_B

var_B_eq = var_B

# Conservative I-AND (serialized upper-bound): sum of branch equivalents

mu_AND = mu_A_eq + mu_B_eq

sd_Aeq = sqrt(var_A_eq)

sd_Beq = sqrt(var_B_eq)

var_AND = var_A_eq + var_B_eq + 2 * rho * sd_Aeq * sd_Beq

Node 7 performs a joint (engineering-product) assessment of the architecture and UX alignment with the requirements. A typical output from this node is arc W7−8 to automated checks. Another possible output is arc W7−1, which models a strategic “pivot” (return to rethinking the concept in case of fundamental inconsistencies).

Next, node 8 (automated checks: AI static analysis + CI/CD build and unit tests) is executed. This is the operational stage where AI-supported static analysis (AI static analysis) complements classic checks; dependencies and security policies are analyzed, anti-patterns and potential defects are detected, a build is performed in the CI/CD pipeline, and unit tests are run.

Node 8 acts as a “quality filter” before human review at node 9. The input is code and configuration changes, dependency manifests, infrastructure as code descriptions, and build telemetry, and the output is a machine-readable package of test results with risk ranking, problem localization, and short fix suggestions, as well as assembled artifacts with unit test results. A key component is AI-supported static analysis, which complements classic SAST with semantic interpretation of call contexts (LLM/ML models), code graph analysis (code property graph, taint-propagation), dependency and SBOM checks for known vulnerabilities and license incompatibilities, search for secrets and configuration flaws, and revision of IaC manifests. The results are aggregated into a vector of quality indicators

SAI = (

Ssec, Srel, Sperf, Slic, Sconf), which is then combined with the assembly and unit test metrics to form a “quality gate”. Formally, the passage to node 9 can be written as the condition

where

—a set of build metrics (success, coverage, stability),

τ—threshold configurable by quality policies.

The influence of node 8 on the network parameters is manifested both in the time distributions and in the subsequent probabilistic choices. First, the expected duration of preparation and execution of checks decreases with increasing quality of static analysis, which is conveniently modeled by the dependence

where is

—component

SAI, which reflects the overall “cleanliness” of the code based on the results of AI analysis.

For dispersion, exponential reduction is natural.

where is

—weighted combination of quality components.

Second, improving security, reliability, and performance reduces the likelihood of rejection during review. Easily enter risk indicators

and describe the rollback as a logistic function

so that the reduction in risk components induced by node 8 monotonically reduces

p9−7 and shortens the local cycle 7 → 8 → 9 → 7.

The indirect effect is also observed in the integration loop, removing system defects before entering node 10 statistically reduces the probability of repeated deployments and retests p11−10, which can be modeled by a similar logistic relationship with a different set of coefficients.

From the point of view of parameter identification, it is advisable to store the telemetry of node 8 (types and severity of findings, confidence level, applied corrections, time costs) and use it to calibrate α, ν, β, and the shapes of the T78, T89 distributions on historical iterations. In practice, this is implemented as a logistic regression for p9−7 with stabilization (for example, isotonic calibration) and Bayesian update of the duration parameters. In this form, node 8 not only “fixes” defects, but also quantifies their impact on the network trajectories; it reduces E[T78] and Var(T78), corrects p9−7 and, indirectly, p11−10, increasing the chances of reaching the terminal node 13 within the given time budgets.

The results of this step are transmitted by arc W89 to node 9 (Peer verification), where one of the decisions is adopted based on the results of the expert review. In case of success, the transition from W9−10 to the integration deployment is approved. In case of problems, the return of W9−7 to the stage after merging the artifacts is approved (which forms a local cycle of “revision → auto-checks → review”).

Integration deployment is performed in node 10 (Integration environment deployment) with subsequent transition W10−11 to node 11 (Automated tests + Quality validation), where regression, load, and other automated tests are launched and a consolidated quality validation is performed. If the tests are passed, the arc W11−12 is activated for final acceptance. If discrepancies are detected, arc W11−10 is activated, forming an internal loop of retests and redeployments until a given quality level is achieved.

Final acceptance is implemented in node 12 (PO/Stakeholder review). If the decision is positive, the transition W12−13 to the terminal node 13 (Increment delivery) is performed, which corresponds to the delivery of the increment. If the scenario is negative, the arc W12−4 is activated, which starts the refinement macrocycle. The flow returns to specification refinement (node 4), then again passes through stages 5 and 6, their combination in 7, automatic checks in 8, review in 9, integration 10−11, and re-acceptance in 12. Thus, the network contains three characteristic feedback loops: local 7 → 8 → 9 → 7 (refinements based on the review results), integration 10↔11 (retest/redeployment), and macrocycle 12 → 4 → ⋯ → 12 refinement based on the acceptance results. The rare but costly W71 arc formalizes the “pivot” scenario.

The final interpretation is as follows. Two AI nodes are explicitly built into the process topology—node 3 (AI Requirements Assistant) as an optional branch of early requirements formalization (driven by the decision in node 2 and leading to W34, and node 8 (AI static analysis as part of automatic checks) as a mandatory operational stage before the review. The remaining nodes and arcs retain the basic semantics of the engineering circuit. The probabilities pij in the decision nodes are normalized to 1 (in particular, p23 + p24 = 1, p9−10 + p9−7 = 1, p11−12 + p11−10 = 1, p12−13 + p12−4 = 1), and the distributions Tij are set according to the practical data of the project. This description format makes the role of AI transparent. In this case, nodes 3 and 8 affect both the probability of reaching node 13 and the expected iteration duration.

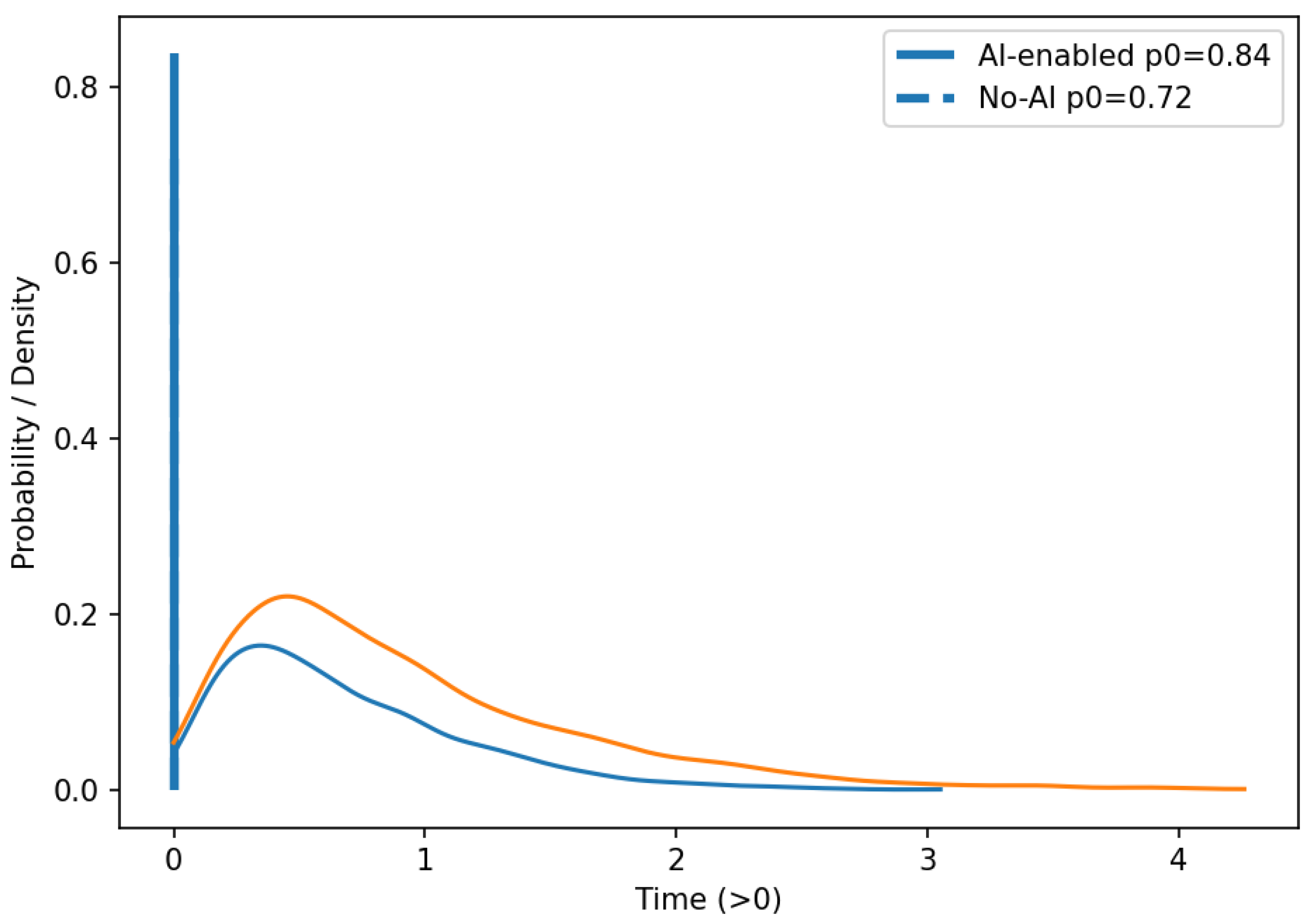

According to the GERT diagram shown in

Figure 3, the equivalent W-function of software development time can be represented as a composition of two interconnected process components. Due to the high analytical complexity of formalizing the full model, we will decompose the diagram into two components: (1) “Software Design” and (2) “Code Implementation and Testing”. The relationship between the components (feedback 7 → 1 and 12 → 4) is expedient to formalize by means of a fuzzy GERT model, where the fuzzy parameterization of probabilities and durations reflects epistemic uncertainty.

For each arc (

i, j), we define the

W-function as the product of the probability weight coefficient and the Laplace transform of the duration distribution:

where the durations are assumed to be gamma-distributed (k,) (positive random variables with wide variability, suitable for “times between events”). This choice agrees well with the “random walk” analogy for human communication and creative steps in design. The final duration is the sum of many stochastic steps, which is naturally approximated by the gamma law.

Consider the first component of the “Software Design” model (nodes 1–7). In our model, this stage includes: 1 → 2 (initial solution), an optional branch 2 → 3 → 4 with AI Requirements Assistant, a direct transition 2 → 4 (if AI is rejected), parallel design 4 → 5 and 4 → 6, and a synchronization node 7 (Successful Collaborative assessment) with I-AND logic at the input.

The main parameters of transitions at the “Software Design” stage are presented in

Table 2.

Let us denote the “direct” (without taking into account the cycle 7 → 1) transition 1 → 7 as

For AND-merge (4 → {5,6} → 7), we apply analytically closed serialized approximation (pessimistic estimate of synchronization time):

In the real process, the completion time of the parallel design branches is determined by the last finishing path. Formally, letting

and

, the synchronization time is

To retain a single closed-form

W-function for the whole network, we adopt a conservative serialized surrogate

which upper-bounds

and avoids optimistic bias in deadline-related metrics at the price of overestimation. This choice preserves the analytic tractability of Equations (7)–(19) and provides a safe planning estimate. Alternative treatments (moment-matching for max, hybrid analytic-simulation) are left for future extensions.

Then, taking into account the return loop “pivot” 7 → 1, the equivalent transfer function of the first component has the form of a geometric reduction:

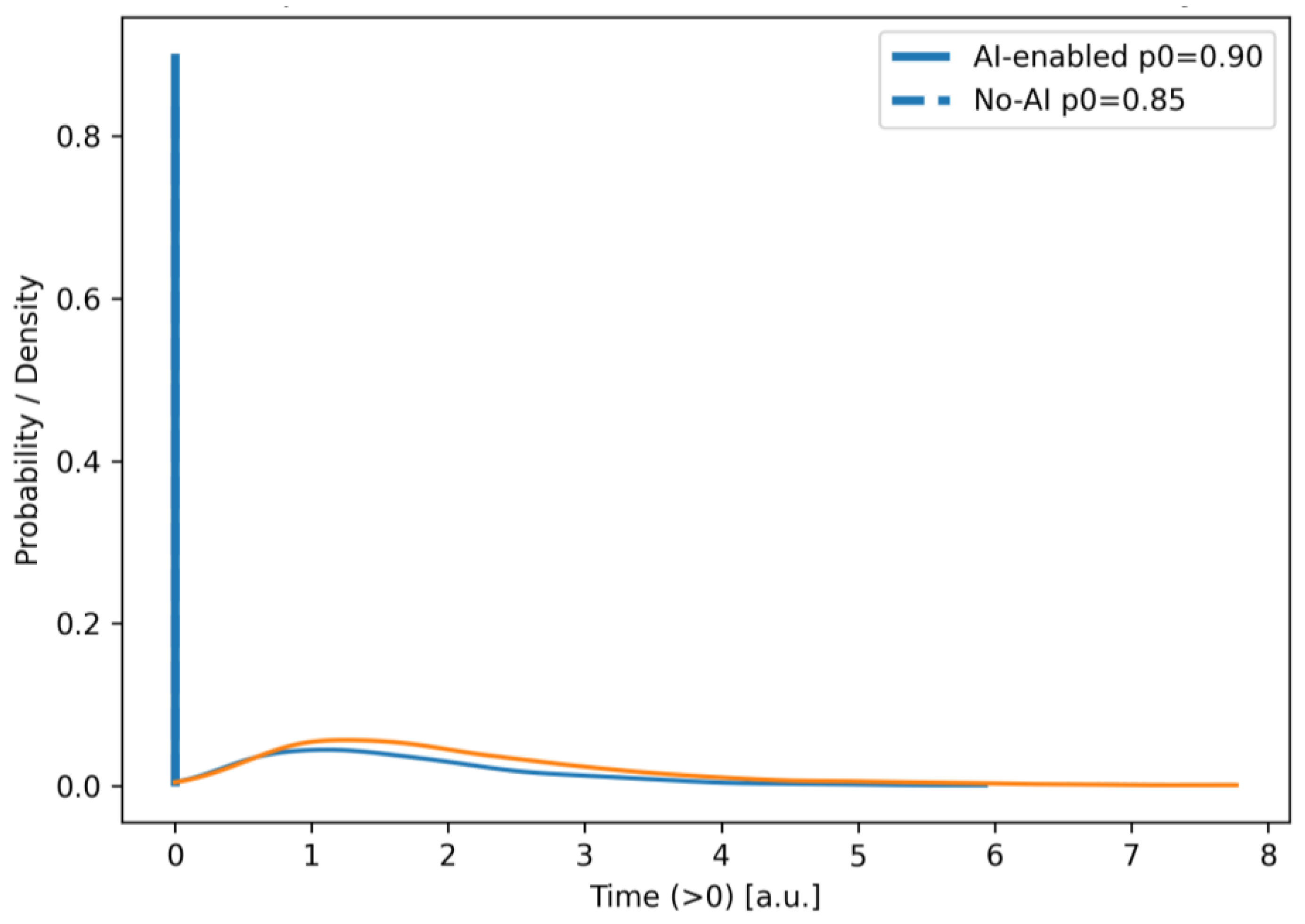

Let us consider the second component of the model, “Code Implementation and Testing” (nodes 7–13).

The stage includes automated checks with AI static analysis (7 → 8), peer-review (8 → 9), local refinement cycle 9↔7, integration deployment 10 and retest cycle 11↔10, as well as final acceptance 12 and release 13. The feedback 12 → 4 is inter-component and is further used to build a “reinforced” (fuzzy) model of the entire network.

The main parameters of the transitions at the stage “Code implementation and testing” are presented in

Table 3.

In this example, serial connection with local loop reduction gives:

The first part of expression (10) formalizes the reduction in the cycle 9↔7. The second part of expression (10) describes the reduction in the cycle 11↔10.

A complete system is formed by a series connection

and

with inter-component feedback 12 → 4. For 12 → 4 we apply fuzzy probabilities

and/or vague durations

(triangular or trapezoidal numbers), advancing them through (1)–(5) according to the Zade expansion principle [

27,

28,

29].

The numerical inversion of the Laplace transform provides an estimate of the system’s time metrics. As a result, the decomposition allows us to obtain interpreted partial equivalent W-functions (9) and (10), and the “enhanced” GERT model allows us to combine them into a holistic characteristic function of the iteration time, taking into account the uncertainties of the requirements, design, and acceptance procedures.

Let us expand the components of expressions (7)–(10) and reduce the model to a closed equivalent W-function of the entire network. To do this, we substitute these components into the aggregated transfer functions of the components.

Lets start with the first component, “Software Design”. We will explicitly rewrite the aggregate “initial” transition 1 → 4, taking into account the optional branch of the AI assistant (2 → 3 → 4).

According to the definition

P(

s) (11) we have

Therefore, taking into account (6),

where

p2−3 +

p2−4 = 1.

Next, for the parallel branches 4 → 5 → 7 and 4 → 6 → 7, we adopt a serialized approximation of AND-merge as (8):

The serialized form (13) is deliberately conservative. Using this expression, the product of Laplace transforms for two consecutive branches, the synchronization time is formalized. Thereby overestimating the duration relative to the approximate maximum of the two stochastic paths. This choice reduces the risk of optimistic planning errors. If necessary, formal accuracy can be easily improved by moment matching for Tmax and numerical inversion. However, for analytical transparency and further inferences, this is not required. Semantically (13) formalizes the achievement of the 7th checkpoint in the presence of both finished artifacts. And it is they who determine the time profile of the final design stage.

Taking into account the pivot loop 7 → 1, the effective transition 4 → 7 is reduced by a geometric factor, we rewrite (9) in expanded form:

The geometric reduction in the denominator of expression 14 has a transparent engineering meaning. multiplier is equal to the “amplification factor” of the large return to zero. While the convergence condition < 1 guarantees that the expected number of such returns is finite. Thus, even with rare strategic revisions to the concept, the process on average moves forward and does not turn into an endless wandering.

Lets examine the second component, “Code Implementation and Testing.” Here, according to expression (10), we have a sequence with two local loops. Their explicit reductions are given as follows:

where each

according to (6), and the probabilities at the decision nodes are normalized:

p9−10 +

p9−7 = 1,

p11−12 +

p11−10 = 1. The sequential transfer from 7 to 12 is equal to

B(s) = B1(s)B2(s).

Both reductions have the same structure. The numerator formalizes the “direct” sequential movement, while the denominator is a geometric correction for the expected number of repetitions. At zero, the convergence conditions simplify to , which in a real process is performed automatically since (otherwise the team would never achieve through the review and integration tests). Here you can see the direct path of influence of node 8 (AI static analysis). decrease by , partially, “compression” of arc lengths 7 → 8 and 8 → 9 lead to a decrease in the denominator in (14), i.e., they reduce the average number and “cost” of review cycle repetitions.

At the output 12 of the node, we have an alternative. Output 12 → 13 and intercomponent return 12 → 4.

Based on this, we can formalize the following.

Next, it is convenient to introduce an “open” transmission from 4 to 12 through 7, which already takes into account the pivot loop and both local reductions:

Closing the intercomponent feedback 12 → 4 with the “loop gain” Fss gives the final equivalent

W-function of the entire network (from 1 to 13):

Size

sets the importance of acceptance. The larger it is, the less often the command returns to specification, and the smaller the contribution of the second denominator in (19). At the same time, the parameters

fix the “price” of such a return. The more complex the requirements refinements and design redesign, the “heavier” the contribution of

F(s) to the overall transfer becomes [

30].

Since is the Laplace transform of the corresponding time measure, standard operations allow you to directly obtain key indicators.

The probability of completing the iteration (reaching node 13) is equal to the value at zero:

Value of equals the probability of completing an iteration. A useful indicator in cases where the model allows for absorbing failure modes (in particular, a potentially infinite cycle of strategic reversals is fundamentally possible). The derivatives at zero give the conditional expectation and variance of the calendar duration of the iteration, in this sense, the geometric multipliers in (13), (14), (15), and (19), formalize the increase in the mean values, which is proportional to the expected number of repetitions of the corresponding cycle. At a practical level, this means that if, say, p9−7 is reduced by 10%, then to first approximation the average number of review cycles falls by about the same amount, and the contribution of B1(s) in (19) proportionally reduces the expected iteration time.

Under the termination condition, the expectation and variance of the iteration time are expressed in terms of derivatives at zero:

From a practical point of view, all parameters (11)–(19) identified from process telemetry. For P(s) and A(s) identified from elicitation and design data (including the AI Requirements Assistant branch). For B1(s) calculated from AI static analysis and CI/CD metrics, as well as review results. For B2(s) identified from integration tests. For S(s) and F(s) generated from acceptance statistics.

If the intercomponent transition 12 → 4 carries significant epistemic uncertainty, the application of fuzzy parameterization , is consistent with the already adopted scheme. Relevant -functions are simply substituted into (17) and passed through expressions (18) and (19) according to the Zadeh expansion principle, after which the numerical inversion of the Laplace transform provides estimates of the time metrics with confidence intervals. Thus, expressions (11)–(21) complete the formalization of the model and are ready for the substitution of data for a specific project.

Given the practical conditions of project implementation, the full model should reflect not only the random (actually stochastic) variability of work durations, which is already taken into account through gamma distributions in the

W-functions of arcs, but also the epistemic uncertainty of parameters, caused by incomplete knowledge at the early stages, domain novelty, and variability of the organizational context. That is why it is advisable to specify some of the network parameters, for example, the transition probabilities

pi−j and the time parameters (

ki−j,

θi−j) of critical arcs (in particular 2 → 3, 7 → 1, 12 → 4, as well as those that determine the quality gate after node 8), as fuzzy numbers of type-1. In this case, the corresponding

W-functions take the form

The final transfer function of the network

preserves the fractional-rational structure (19), but with fuzzy parameters. The estimation is performed according to the principle of Zade expansion through α. For each

parameters

,

,

are replaced by interval estimates, and expression (19) is calculated intervalically, which generates a range of values

At the point

s = 0, this gives a fuzzy probability of the iteration ending. In particular,

Derivatives are used for time points and at zero (while preserving the monotonicity of the corresponding mappings), which provides interval estimates and . Thus, the model returns not point, but interval (or, in fuzzy mathematics terms, possibility-necessity) characteristics of key metrics, and the narrowing of α-intersections in the process of CI/CD telemetry accumulation, review, and acceptance reflects the gradual reduction in epistemic uncertainty without changing the structure of the GERT composition.

Thus, the mathematical model (11)–(19) not only specifies the equivalent W-function of the network but also makes transparent the mechanism of influence of local solutions and quality of artifacts on global time indicators. Together with (21) and (22), it forms a self-sufficient tool for forecasting terms and risks, where the parameters are directly related to the measured process quantities, and the two AI-insertions (nodes 3 and 8) have an explicit and reproducible effect on the structural elements of the transfer function.

A mathematical model of the software development process with elements of hybrid management has been developed. Unlike others, the model takes into account the topology of the real hybrid project management process and provides causal levers (loop/duration parameters). This allows for the return of interval metrics under uncertainty and is directly translated into planning indicators.