Mechanism and Simulation Analysis of Acoustic Wave Excitation by Partial Discharge

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Mechanism of Acoustic Waves Generated by Corona Discharge

3. Numerical Simulation of Positive DC Corona Discharge and Exciting Acoustic Waves

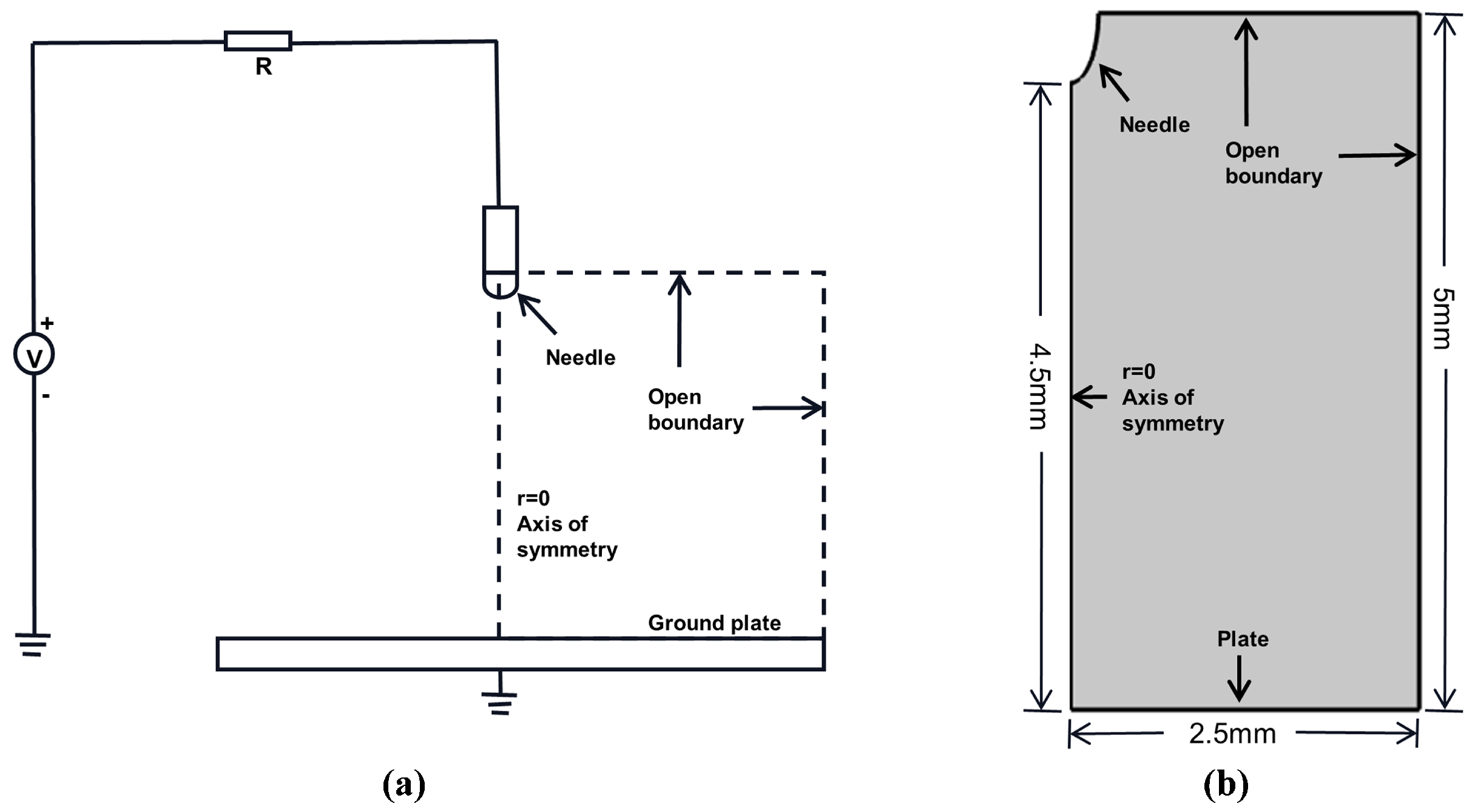

3.1. Simulation of Positive Needle Plate DC Corona Discharge Based on Fluid–Chemical Reaction Hybrid Model

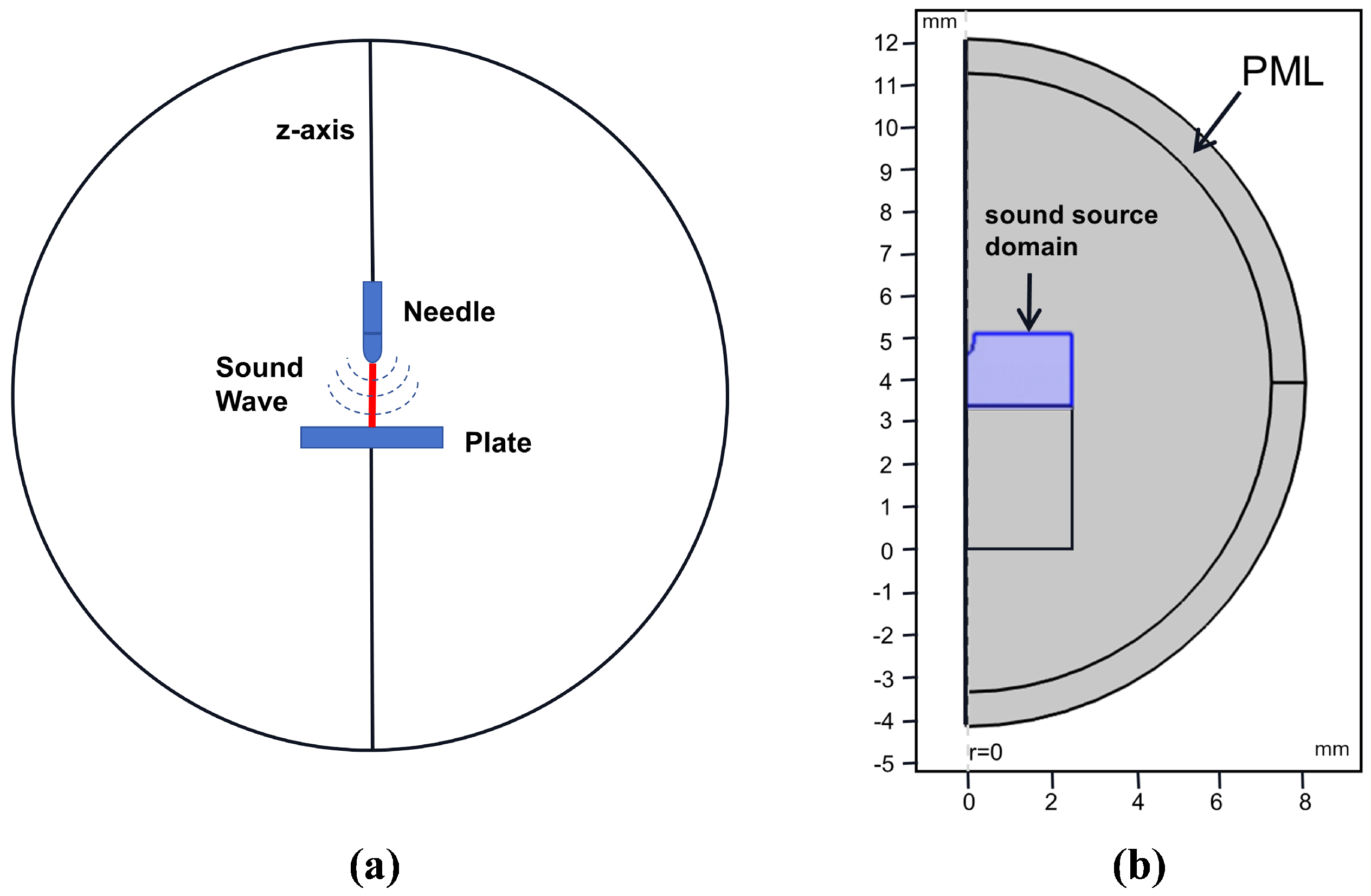

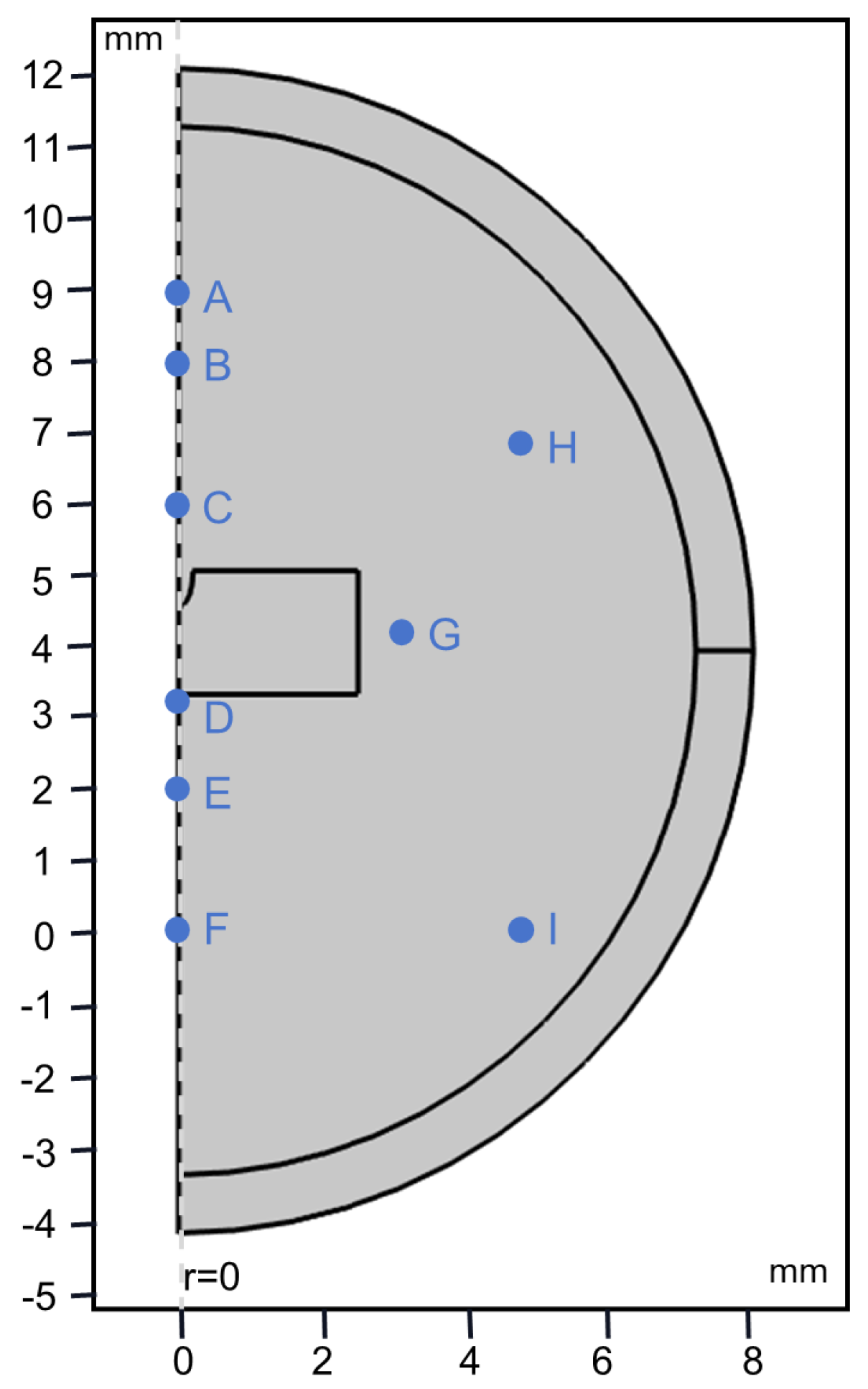

3.2. Finite Element Method for Solving Acoustic Field

4. Simulation Results and Discussion

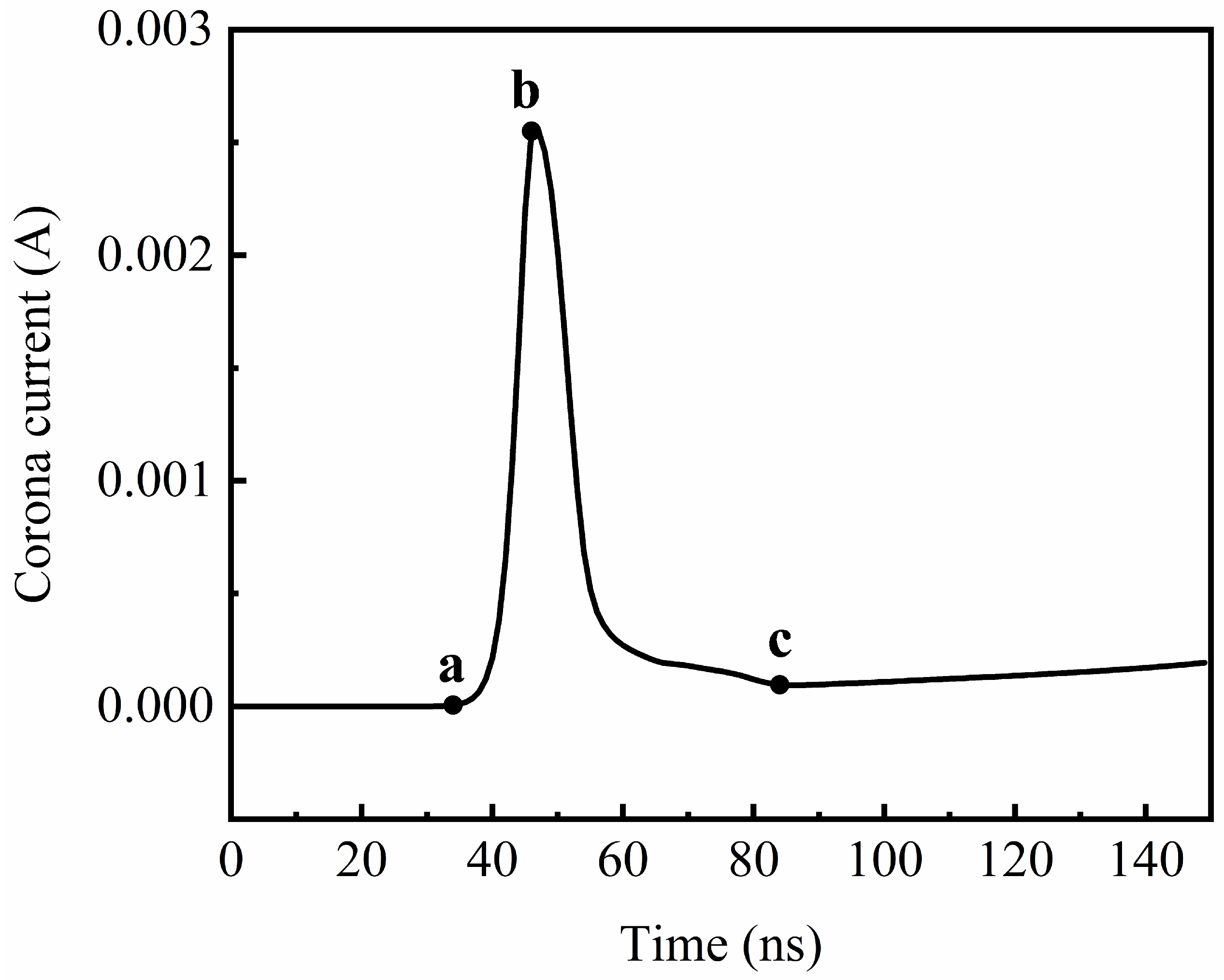

4.1. Numerical Simulation of Corona Discharge

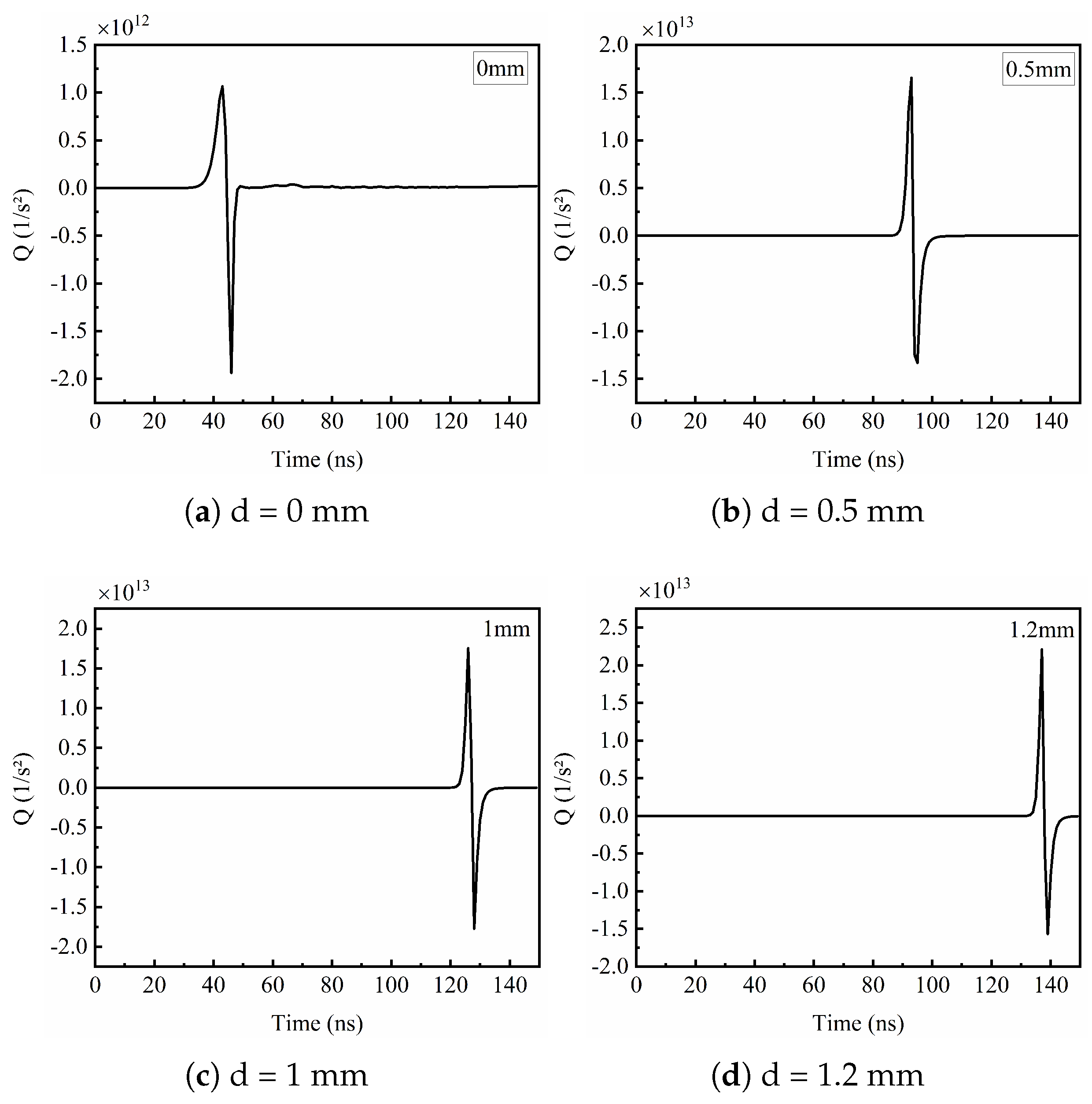

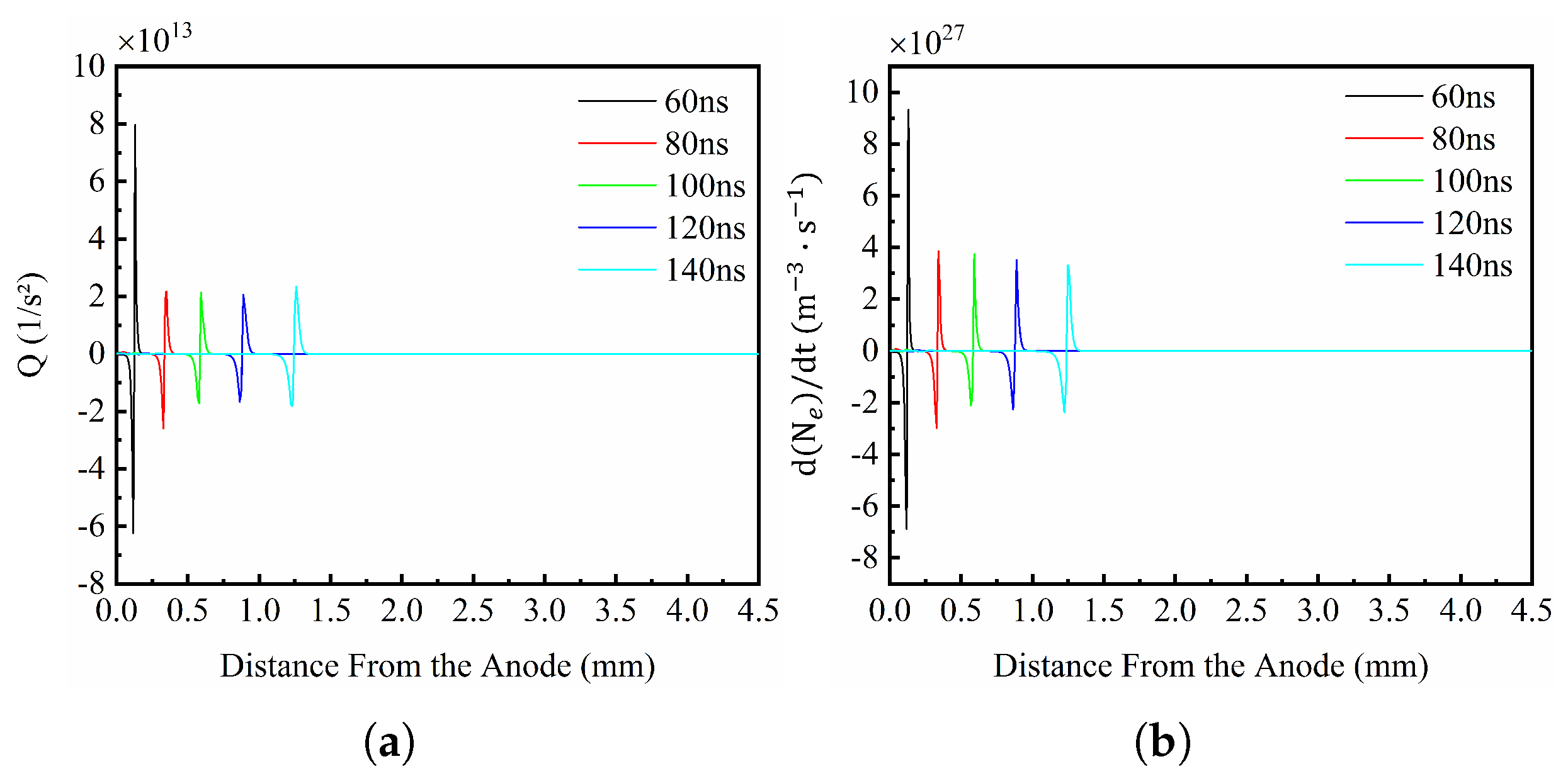

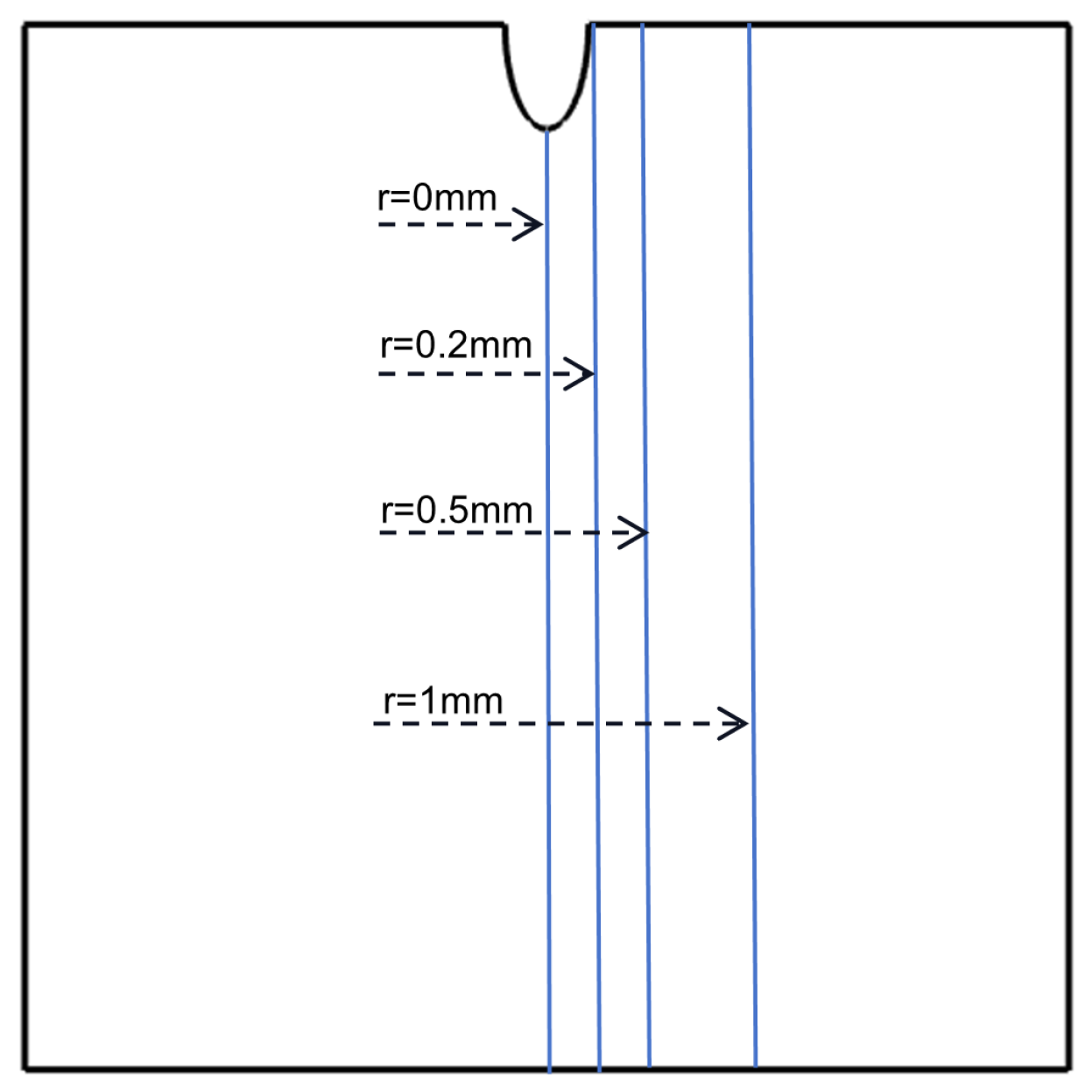

4.2. Numerical Simulation of Acoustic Source Distribution

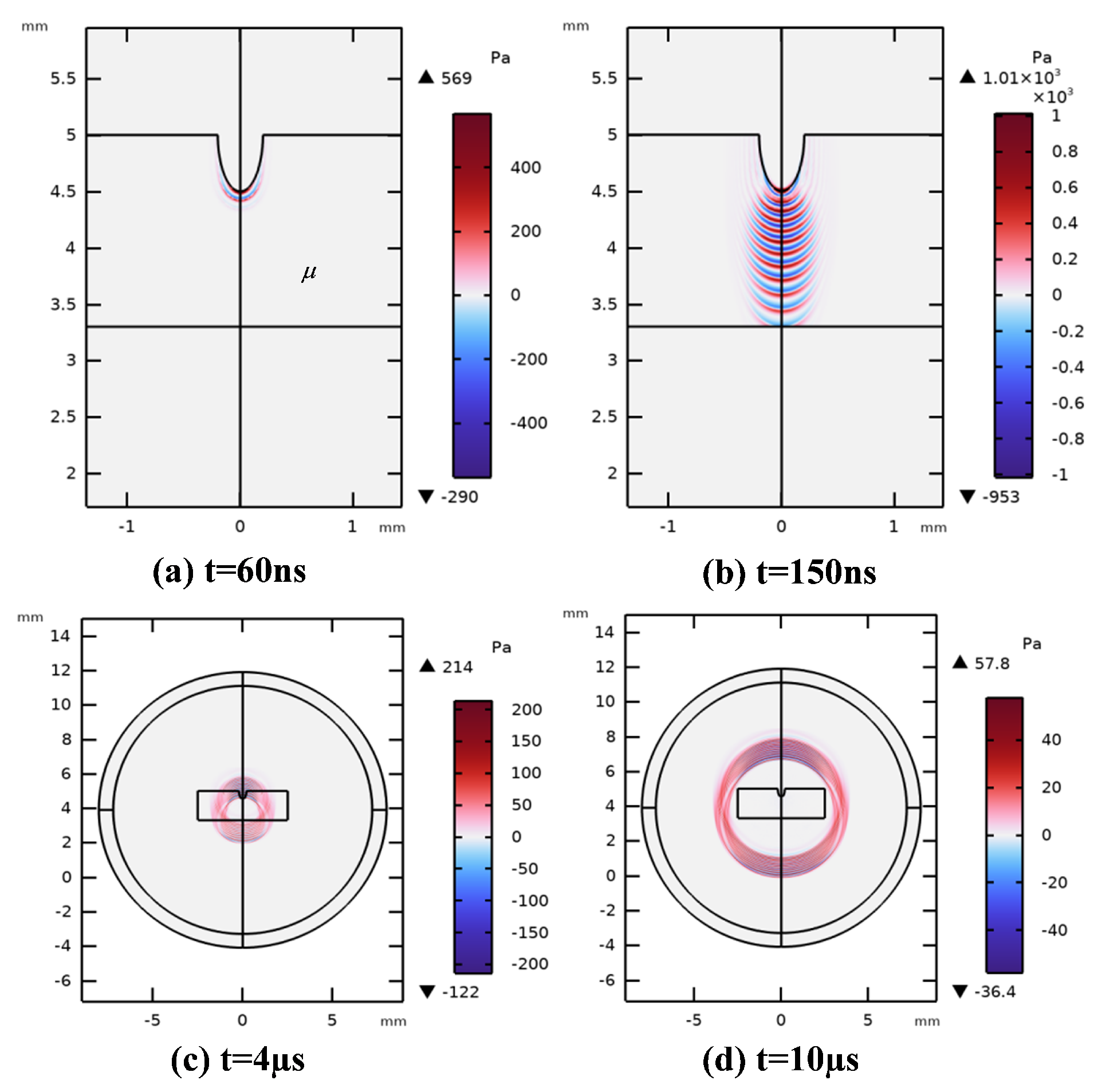

4.3. Numerical Simulation of Acoustic Field

4.4. Discussion

- (1)

- Generation Mechanism and Source Geometry

- (2)

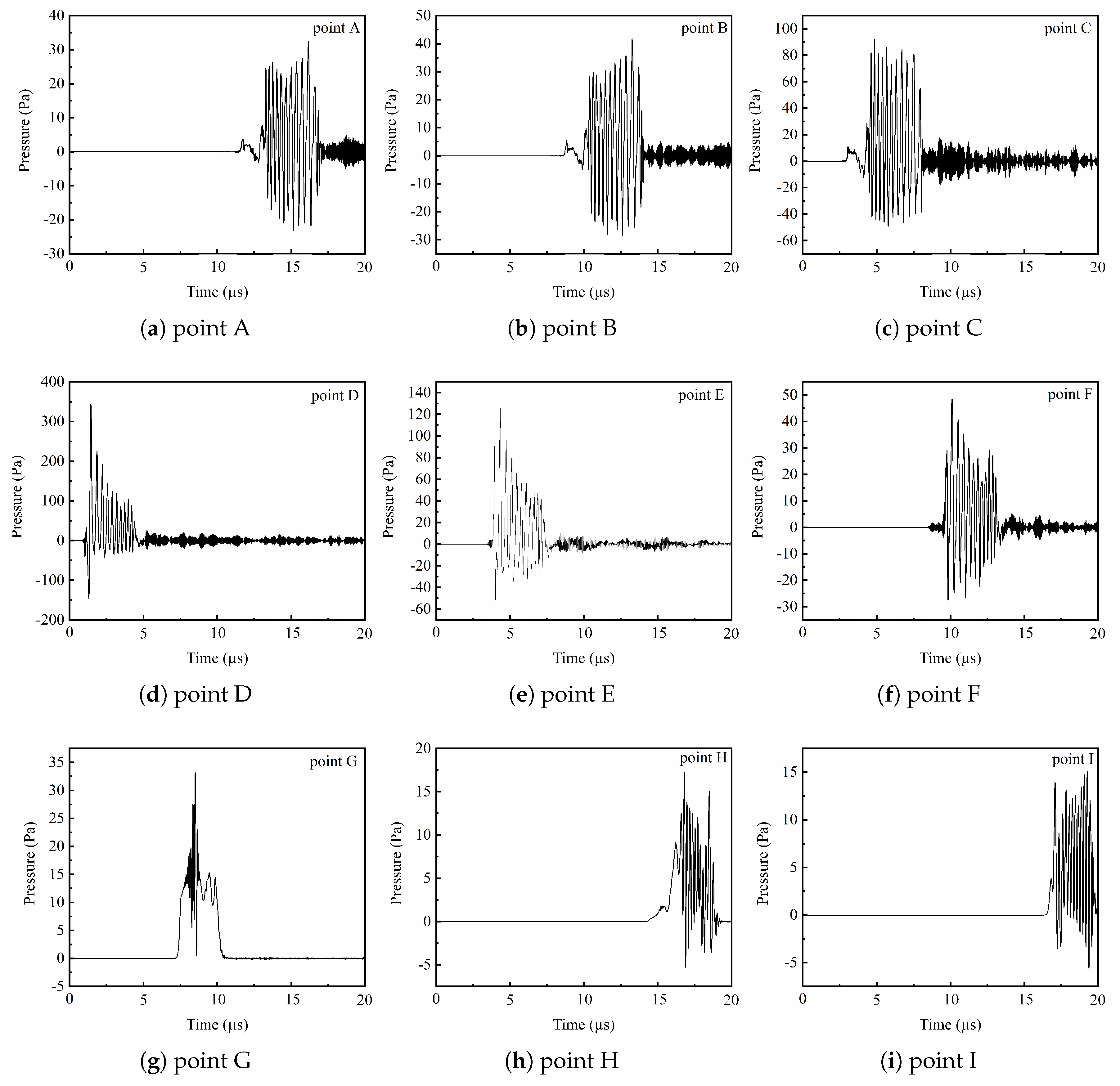

- Acoustic Waveform Structure

- (3)

- The Frequency Spectrum

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- During the positive DC corona discharge process, the variation in electron density over time and space plays a primary role in the generation of acoustic waves.

- (2)

- The generation of the acoustic source is related to the development of the discharge channel during the discharge process. The acoustic source can be considered as a linear source distributed along the axis of the needle electrode to the plate electrode.

- (3)

- The acoustic field generated by the discharge domain acoustic source is superimposed and expands over time in an approximately spherical wave form, but there is an amplitude enhancement phenomenon in specific directions.

- (4)

- The acoustic signals generated by discharge are composed of multiple acoustic pulses, and the envelope of the acoustic wave shows regularity in the direction of propagation from the needle tip to the electrode.

- (5)

- The acoustic waves generated by corona discharge are broadband signals, and the energy is mainly concentrated in the ultrasonic frequency range.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaziz, S.; Said, M.H.; Imburgia, A.; Maamer, B.; Flandre, D.; Romano, P.; Tounsi, F. Radiometric partial discharge detection: A review. Energies 2023, 16, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathod, V.B.; Kumbhar, G.B.; Bhalja, B.R. Partial discharge detection and localization in power transformers based on acoustic emission: Theory, methods, and recent trends. IETE Tech. Rev. 2022, 39, 540–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaacob, M.; Alsaedi, M.A.; Rashed, J.; Dakhil, A.; Atyah, S. Review on partial discharge detection techniques related to high voltage power equipment using different sensors. Photonic Sens. 2014, 4, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilkhechi, H.D.; Samimi, M.H. Applications of the acoustic method in partial discharge measurement: A review. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2021, 28, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, L.; Ren, X.; Wu, F.; Song, J.; Zhang, J. Partial discharge monitoring method for high voltage equipment based on ultrasound technology. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Electronic Information and Communication Technology (ICEICT), Harbin, China, 20–22 January 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 853–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Zhao, K.; Xie, C.; Li, X.; Chen, J.; Hu, L. Distributed online monitoring method and application of cable partial discharge based on φ-OTDR. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 144444–144450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Wu, K.; Wu., X.; Ma, G.; Zhang, C. Characteristics of the propagation of partial discharge ultrasonic signals on a transformer wall based on Sagnac interference. Plasma Sci. Technol. 2019, 22, 024002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastien, F. Acoustics and gas discharges: Applications to loudspeakers. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 1987, 20, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingard, U. Acoustic wave generation and amplification in a plasma. Phys. Rev. 1966, 145, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitaire, M.; Mantei, T. Acoustic wave generation by temperature modulation of a plasma. Phys. Lett. A 1969, 29, 84–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitaire, M.; Mantei, T. Some experimental results on acoustic wave propagation in a plasma. Phys. Fluids 1972, 15, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béquin, P.; Montembault, V.; Herzog, P. Modelling of negative point-to-plane corona loudspeaker. Eur. Phys. J.-Appl. Phys. 2001, 15, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Li, Z.; He, J. A numerical model of acoustic wave caused by a single positive corona source. Phys. Plasmas 2017, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cui, X.; Lu, T.; Wang, D. Propagation characteristics of audible noise generated by single corona source under positive DC voltage. AIP Adv. 2017, 7, 105005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweon, D.J.; Chin, S.B.; Kwak, H.R.; Kim, J.C.; Song, K.B. The analysis of ultrasonic signals by partial discharge and noise from the transformer. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2005, 20, 1976–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, L. Time-domain performance of audible noise for positive dc corona: Numerical simulations and measurements. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2017, 23, 3275–3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cui, X.; Lu, T.; Ma, W.; Bian, X.; Wang, D.; Hiziroglu, H. Statistical characteristic in time-domain of direct current corona-generated audible noise from conductor in corona cage. Phys. Plasmas 2016, 23, 033503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacem, S.; Ducasse, O.; Eichwald, O.; Yousfi, M.; Meziane, M.; Sarrette, J.P.; Charrada, K. Simulation of expansion of thermal shock and pressure waves inducaed by a streamer dynamics in positive dc corona discharges. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2013, 41, 942–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, R.-J.; Wu, F.-F.; Liu, X.-H.; Yang, F.; Yang, L.-J.; Zhou, Z.; Zhai, L. Numerical simulation of transient space charge distribution of DC positive corona discharge under atmospheric pressure air. Acta Phys. Sin. 2012, 61, 2665923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samara, V.; Sutton, Y.; Braithwaite, N.; Ptasinska, S. Acoustic characterization of atmospheric-pressure dielectric barrier discharge plasma jets. Eur. Phys. J. D 2020, 74, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zou, X.; Wang, P.; Luo, H. Investigation of the microsecond-pulse acoustic wave generated by a single nanosecond-pulse discharge. Phys. Plasmas 2022, 29, 053508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, R.; Oda, T. Visualization of Streamer Channels and Shock Waves Generated by Positive Pulsed Corona Discharge Using Laser Schlieren Method. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2004, 43, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutakamihigashi, T.; Tajiri, S.; Okada, S.; Ueno, H. Relationship between AE waveform frequency and the charges caused by partial discharge in mineral oil. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2021, 28, 1844–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wu, Z.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, C.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Q. Acoustic mode transition of creeping discharge from oil–paper interface to interior of insulating paper. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wu, Z.; Zhu, J.; Xu, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Q. Electroacoustic transition of partial discharge in insulating oil: From the correlation of acoustic wave and discharge energy. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2024, 31, 3092–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.W.; Choi, S.Y.; Kil, G.S. Measurement and analysis of acoustic signal generated by partial discharges in insulation oil. In Proceedings of the 7th WSEAS International Conference on Electric Power Systems, Venice, Italy, 23–23 November 2007; pp. 272–275. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237456539 (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Kurimskỳ, J.; Rajňák, M.; Šárpataky, M.; Čonka, Z.; Paulovičová, K. Electrical and acoustic investigation of partial discharges in two types of nanofluids. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 341, 117444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mesh Parameter | Statistical Results |

|---|---|

| Triangular elements | 108,559 |

| Edge elements | 825 |

| Minimum element quality | 0.1945 |

| Average element quality | 0.9241 |

| Element area ratio |

| Boundary Conditions | Applied Voltage | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axis | ||||

| Needle Electrode | ||||

| Open Boundary | ||||

| Plate Electrode |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Z.; Wu, X.; Leng, T.; An, B.; Dong, W. Mechanism and Simulation Analysis of Acoustic Wave Excitation by Partial Discharge. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11611. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111611

Li Z, Wu X, Leng T, An B, Dong W. Mechanism and Simulation Analysis of Acoustic Wave Excitation by Partial Discharge. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(21):11611. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111611

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Ziqi, Xianmei Wu, Tao Leng, Bingwen An, and Wei Dong. 2025. "Mechanism and Simulation Analysis of Acoustic Wave Excitation by Partial Discharge" Applied Sciences 15, no. 21: 11611. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111611

APA StyleLi, Z., Wu, X., Leng, T., An, B., & Dong, W. (2025). Mechanism and Simulation Analysis of Acoustic Wave Excitation by Partial Discharge. Applied Sciences, 15(21), 11611. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111611