Towards Improved Efficiency of Low-Grade Solar Thermal Cooling: An RSM-Based Multi-Objective Optimization Study

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

1.2. Importance of Absorption Chillers and Current Challenges

1.3. Literature Gaps and Related Work

1.4. Objective, Scope, and Contributions

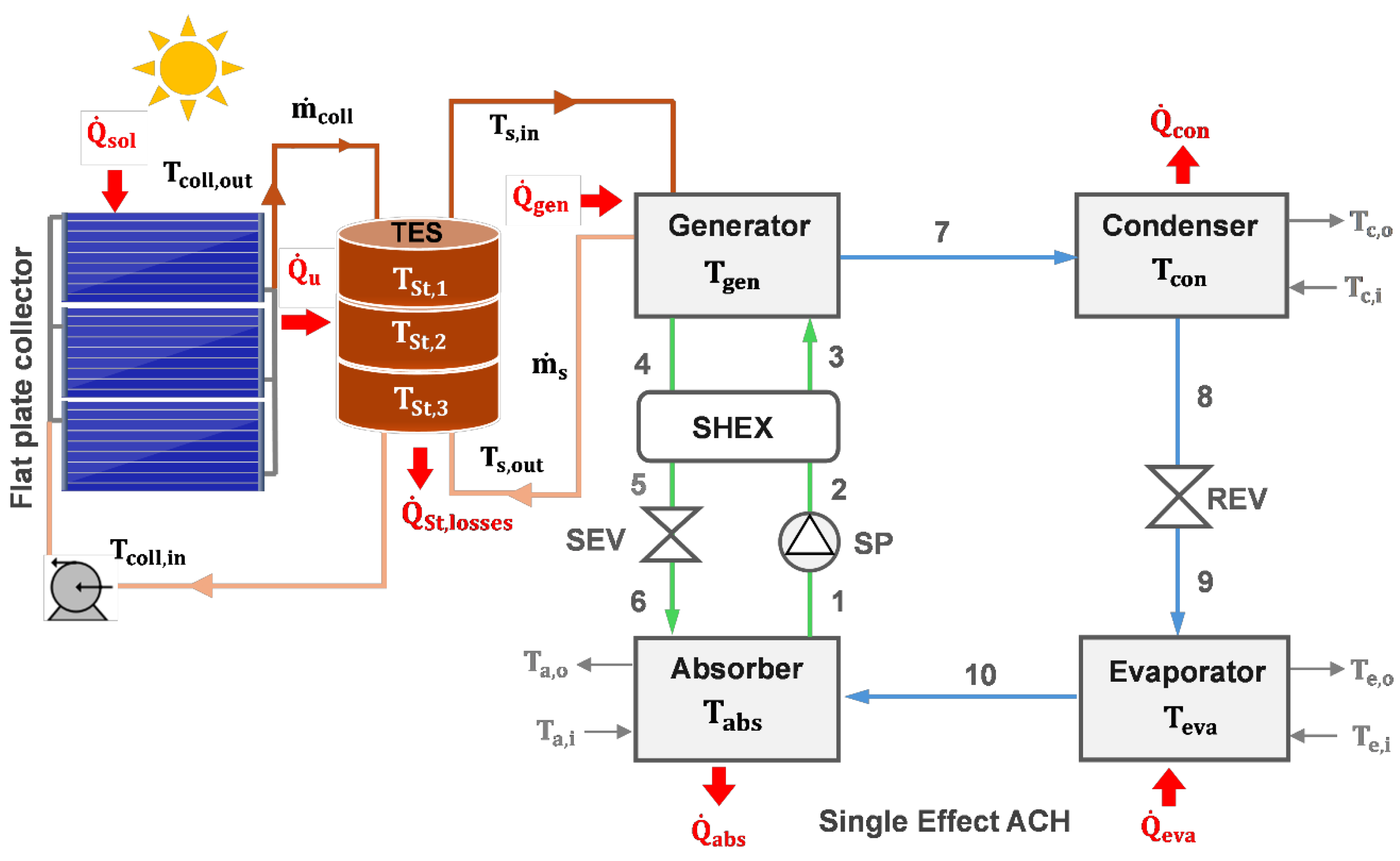

2. System Description

- Generation (GE)—Thermal energy (): The generator is powered by a heat source, such as solar energy or waste heat, which evaporates water from the LiBr solution (State 7). The produced high-pressure vapor is directed to the condenser, while the weak solution (State 4) is returned to the absorber.

- Condensation (CO)—Heat Rejection: occurs when high-pressure vapor (State 7) condenses into liquid (State 8) in a condenser, releasing heat () to the surroundings.

- Evaporation (EV)—Cooling Effect: The cooling effect occurs when the liquid refrigerant expands through a valve (State 9) and enters the evaporator, absorbing heat from the cooling load (.

- Absorption (AB)—Solution Regeneration: The LiBr solution (State 1) absorbs the low-pressure vapor (State 10) in the absorber, resulting in a strong solution (State 6) and heat release ( contributing to environmental sustainability. The strong solution (States 2–3) is fed back into the generator to complete the cycle.

3. Mathematical Modeling

- The system operates under steady-state conditions,

- Pressure drops and heat losses throughout all components are negligible,

- The refrigerant is saturated at the outlets of the condenser and evaporator,

- The absorber’s weak solution and the generator’s strong solution are both saturated and in thermal equilibrium at their respective temperatures,

- Chemical, kinetic, potential, and associated exergy factors are ignored due to their small significance.

- The reference specific enthalpy () and entropy () or exergy calculations are defined at 25 °C and 1 atm.

3.1. Energy Analysis

3.1.1. Solar Energy Collecting Model

3.1.2. Thermal Storage Tank Model

3.1.3. Absorption Cooling System Model

3.2. Exergy Analysis

3.3. Key Performance Indicators

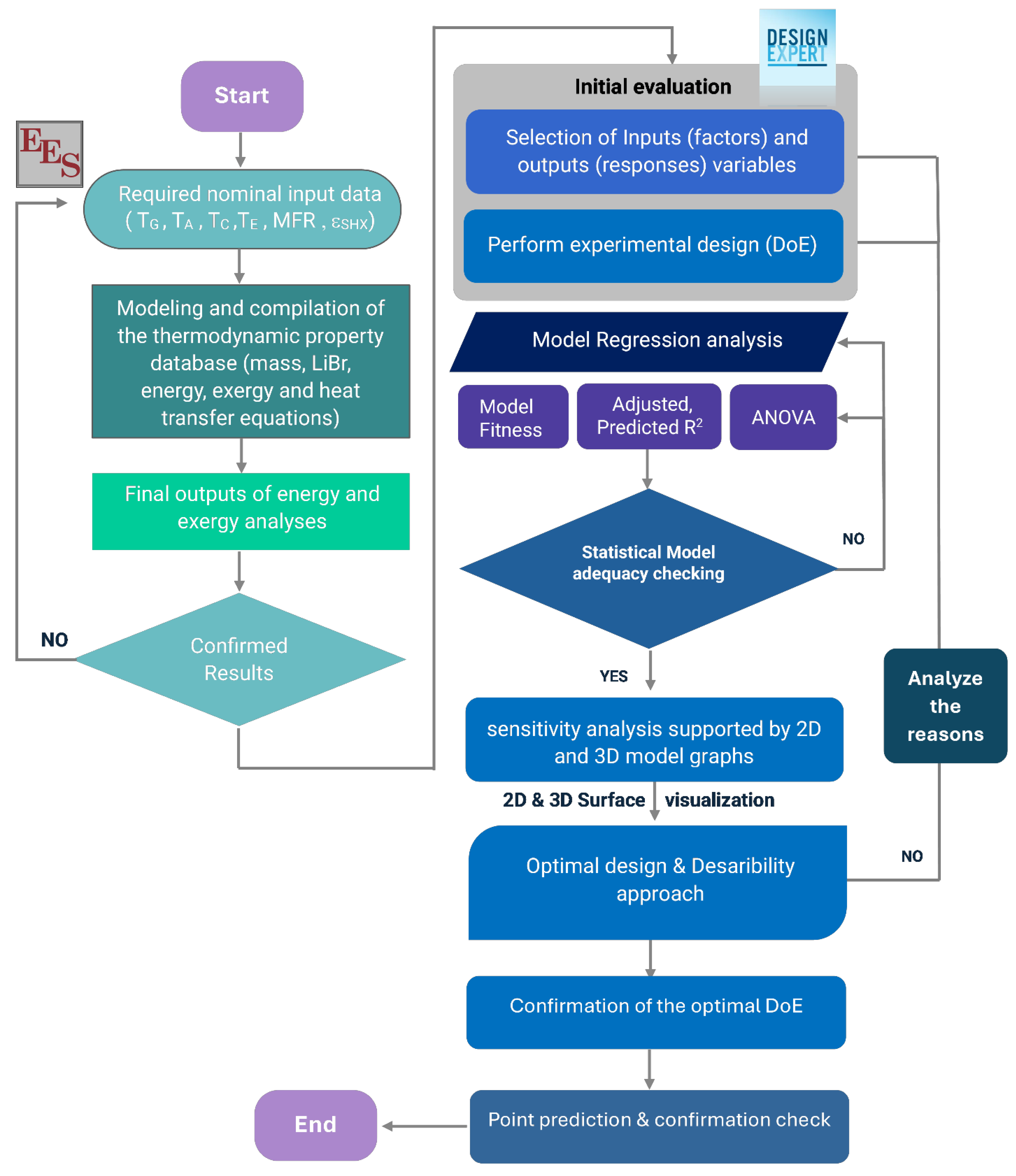

4. Process Simulation and Multi-Objective Optimization Approach

4.1. Followed Methodology

4.2. RSM-BBD Optimization

5. Model Validation

6. Results and Discussion

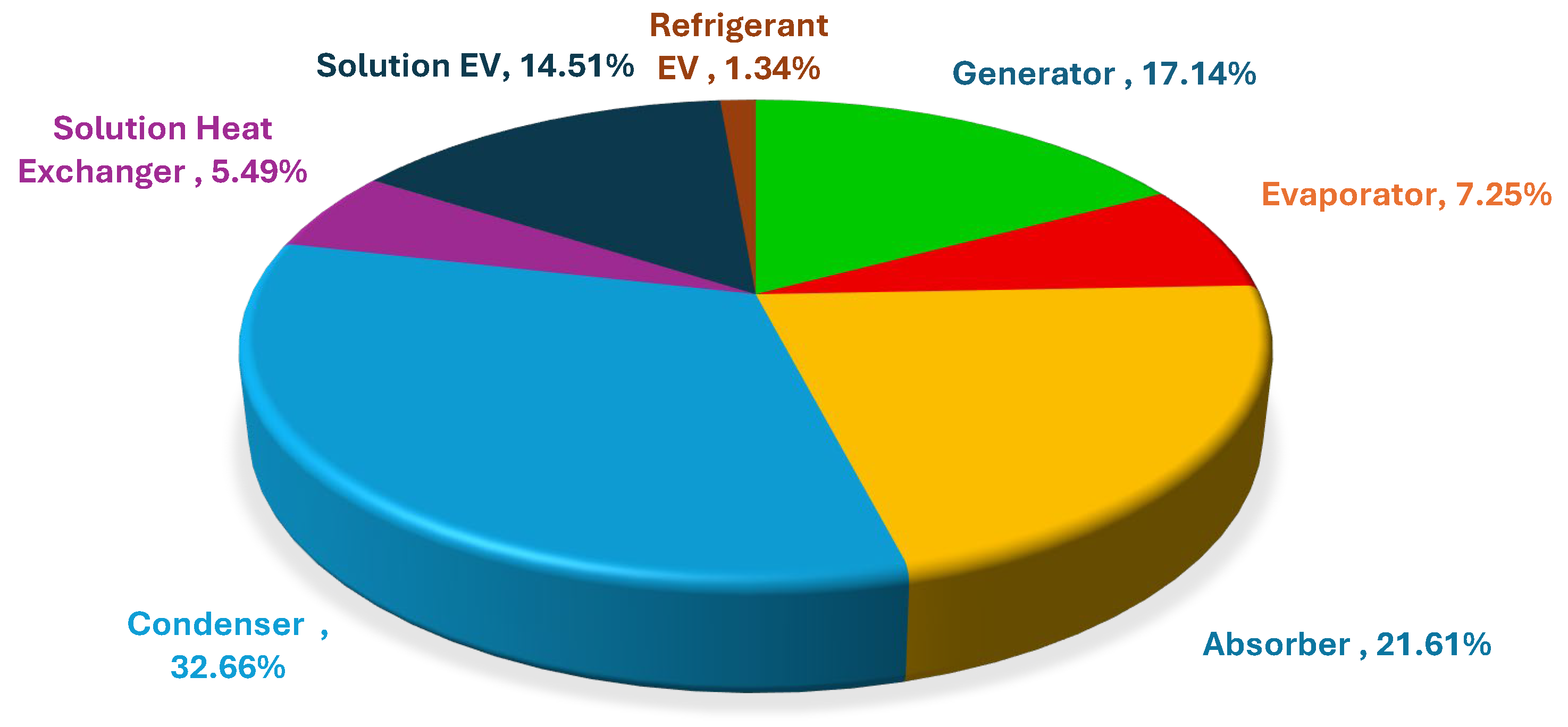

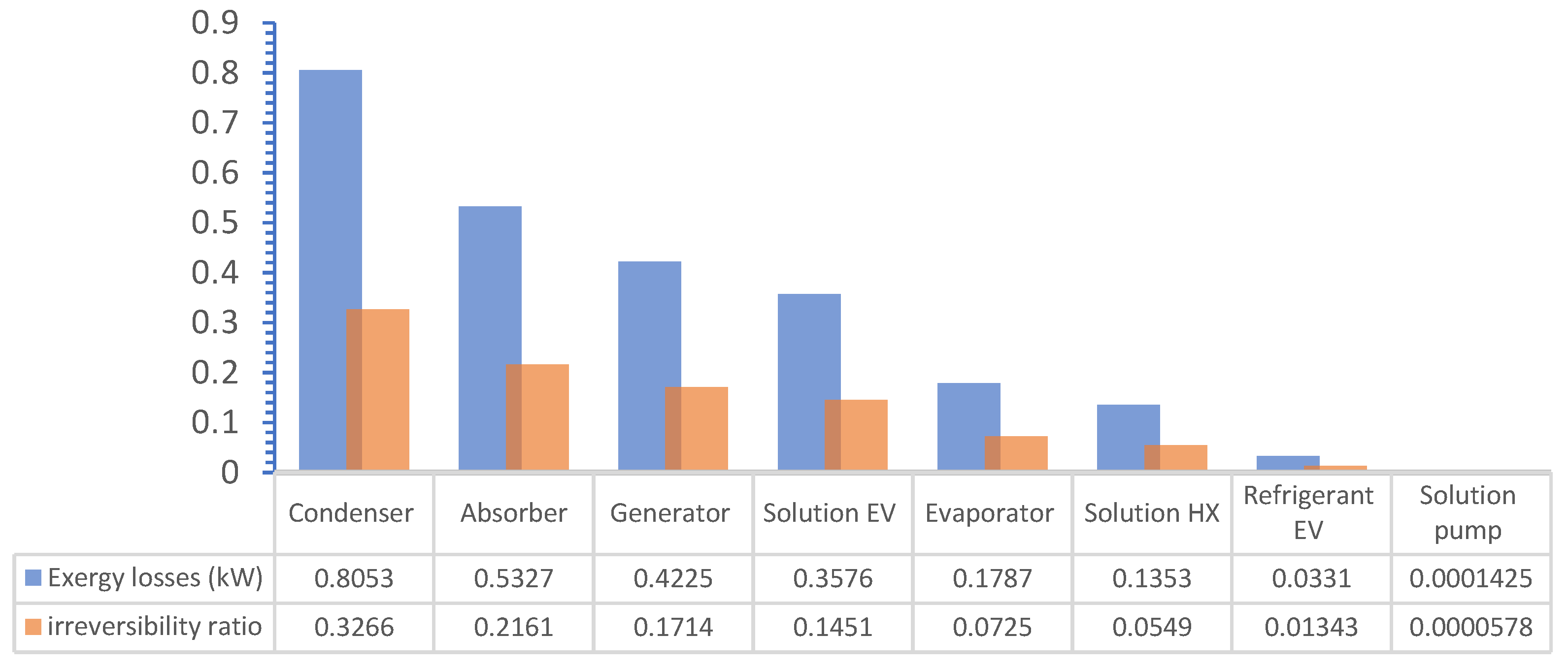

6.1. Pre-Optimization Results

6.2. RSM-Built Regression Model

6.3. ANOVA and Model Significance

6.4. Statistical Model Assessment

6.5. Parametric Analysis: Interaction Effects of Key Process Variables

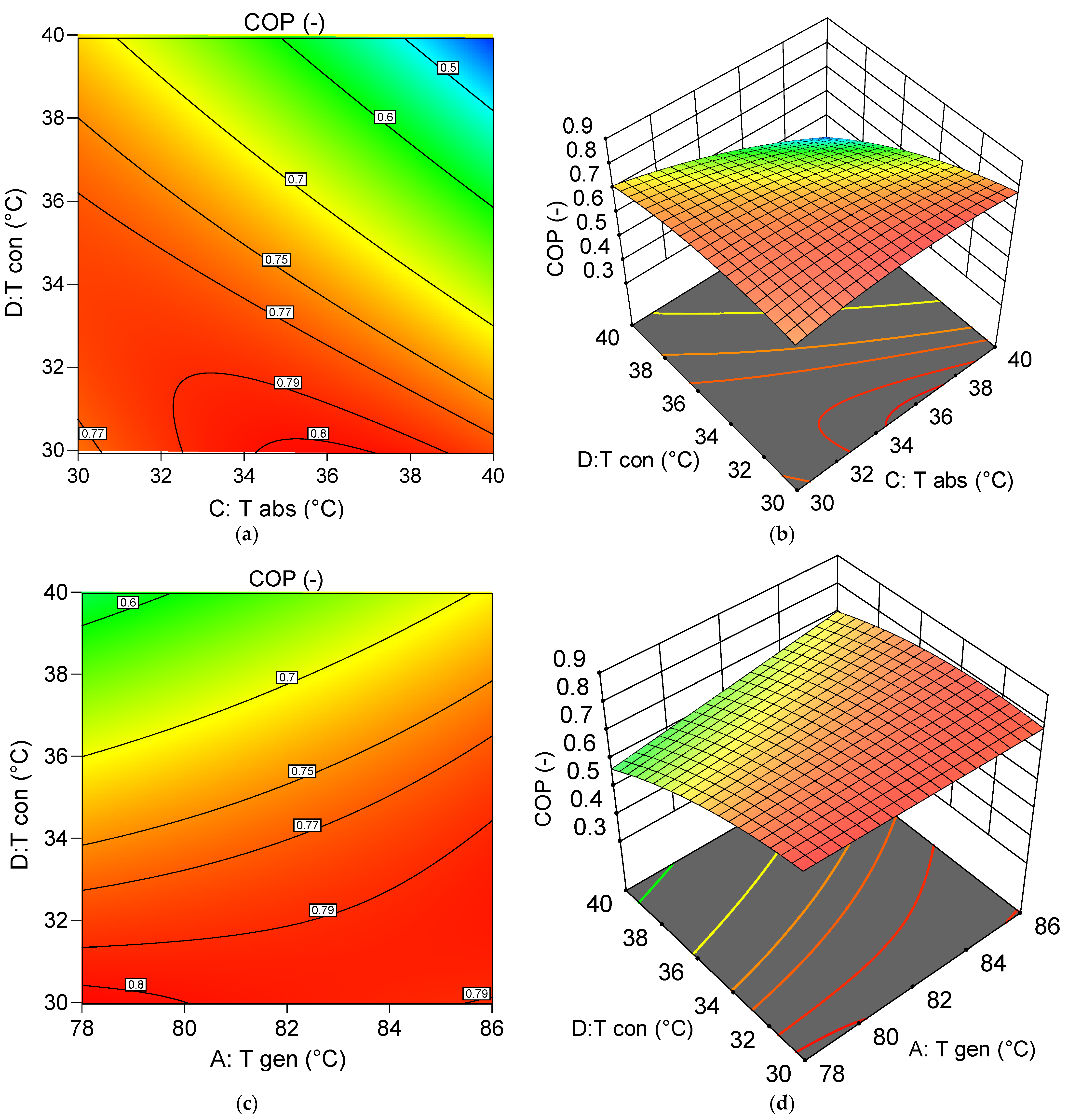

6.5.1. Assessment of the Effect of Decision Variables on the System COP

- A: Generator temperature () = 82 °C;

- B: Evaporator temperature () = 6.5 °C;

- C: Absorber temperature () = 30 °C;

- D: Condenser temperature () = 35 °C.

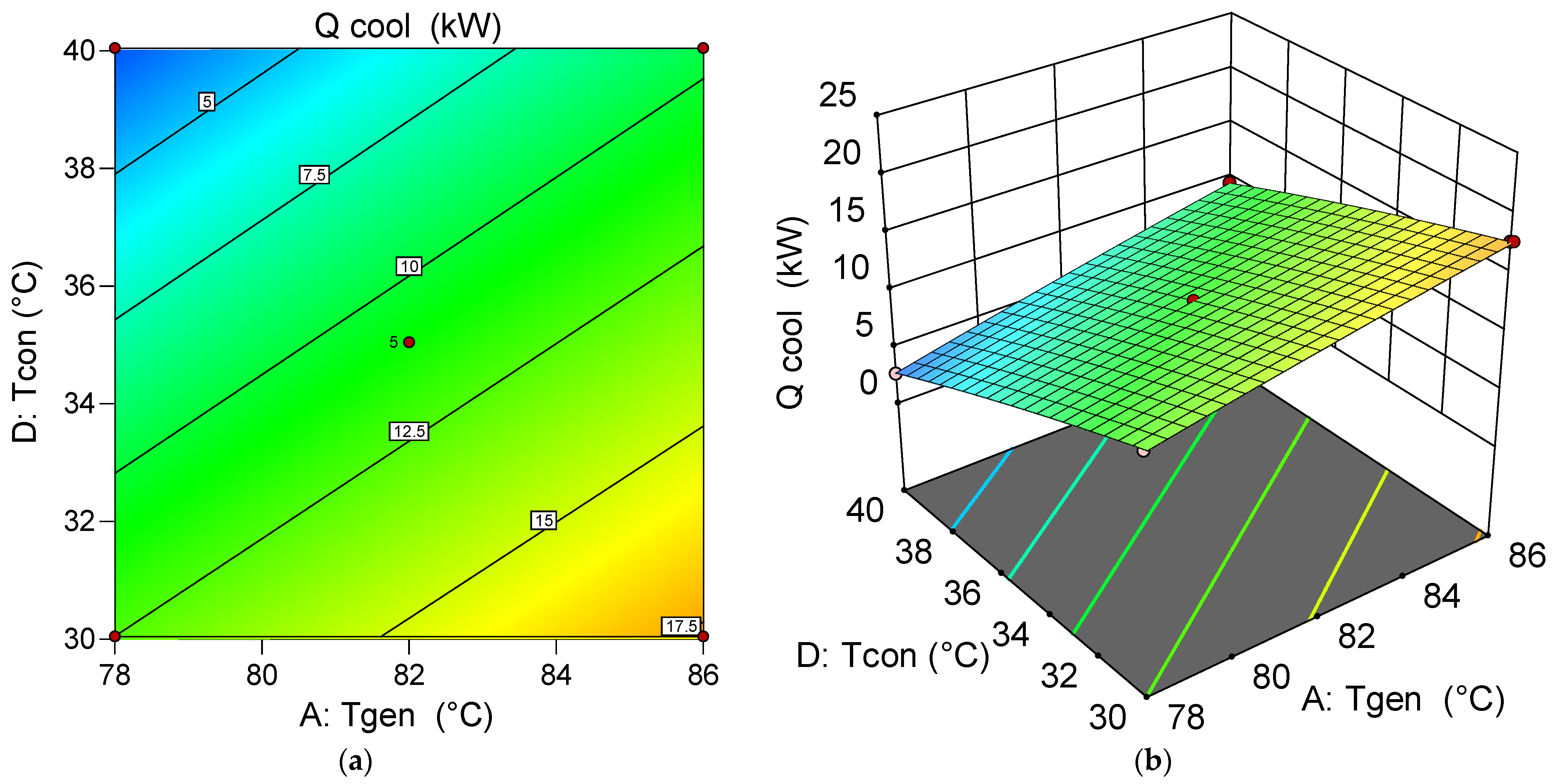

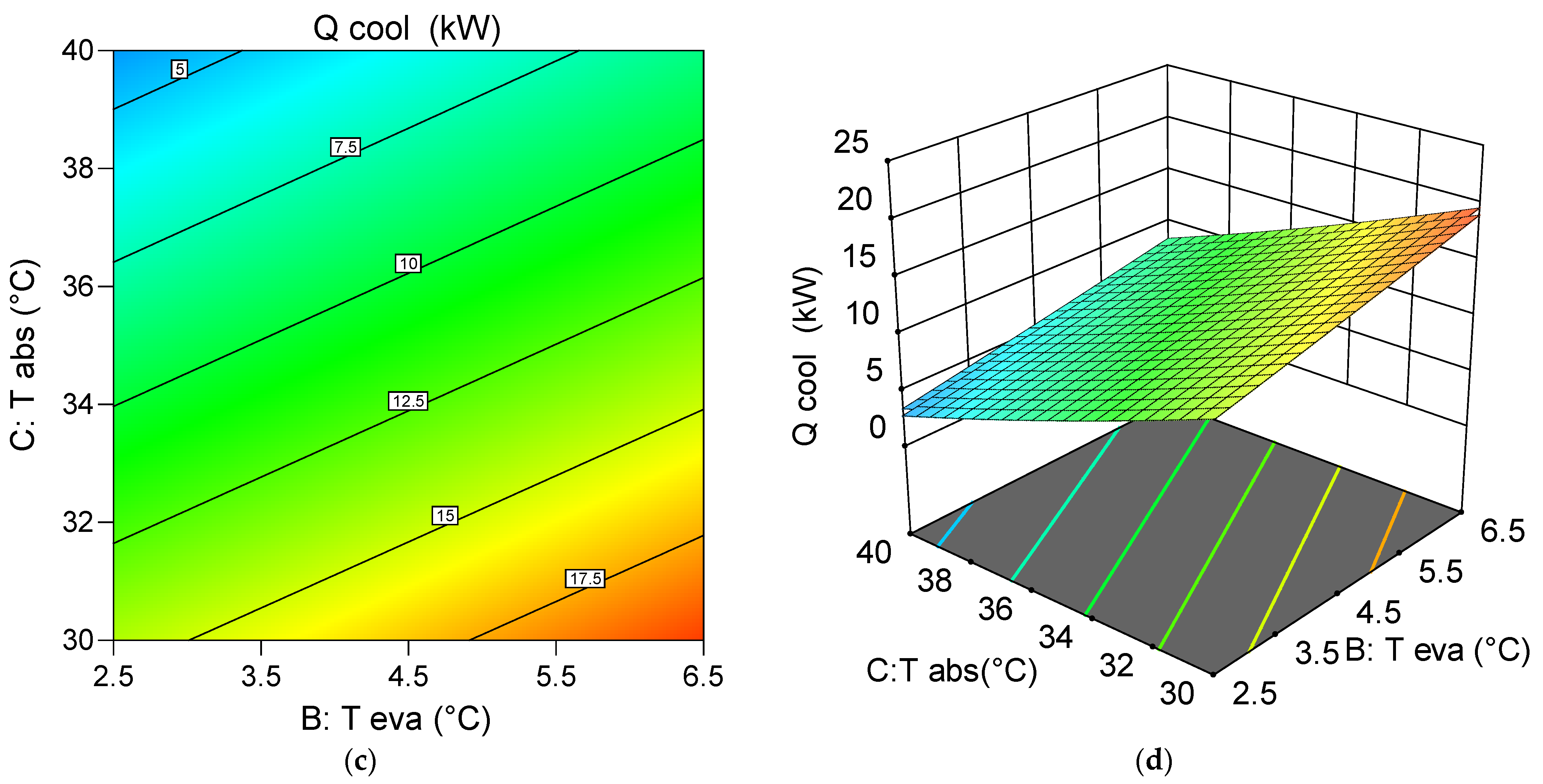

6.5.2. Assessment of the Effect of Decision Variables on the System Chiller Generation Capability

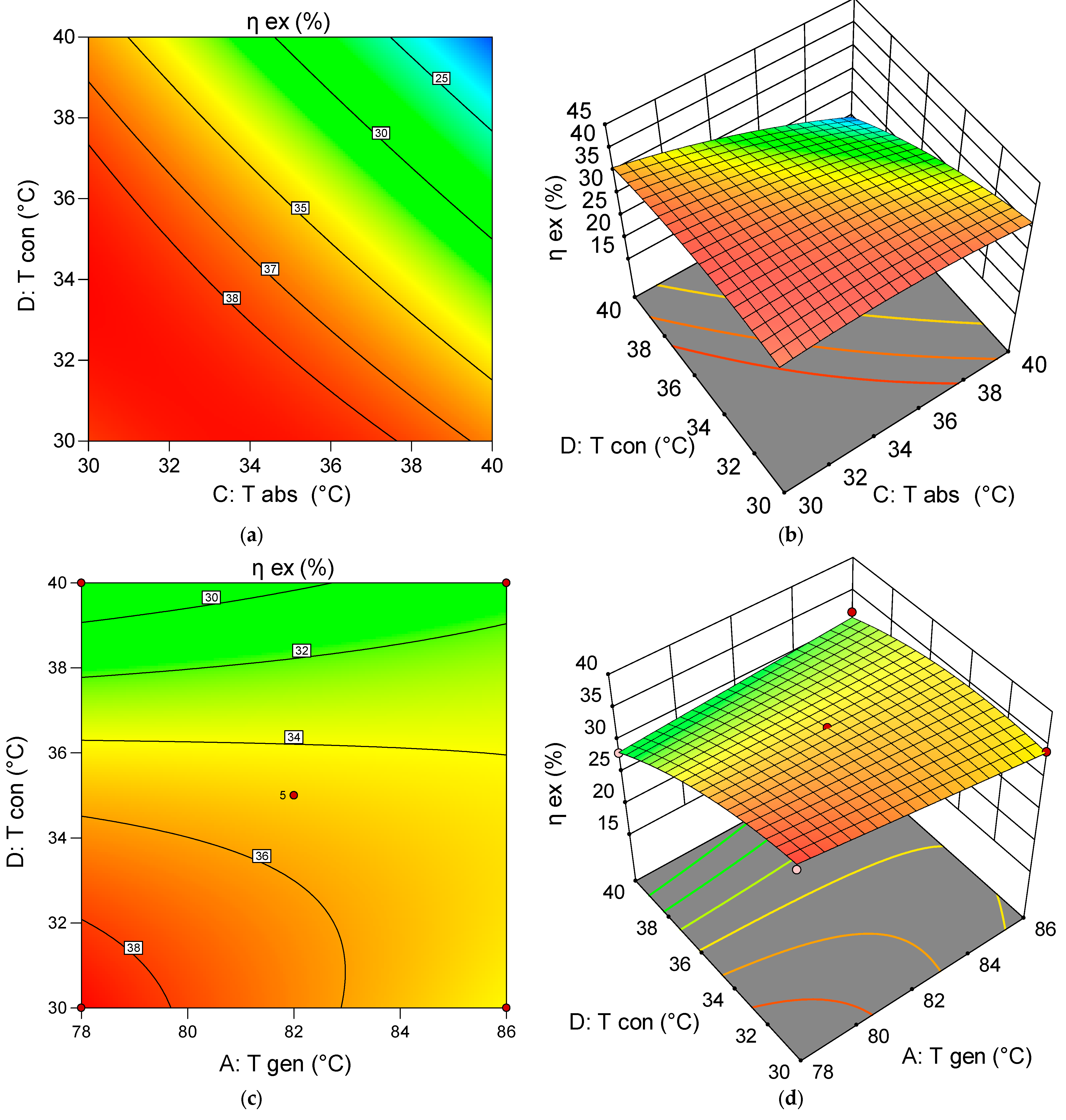

6.5.3. Interaction Results of Decision Parameters on the Exergy Efficiency of the System

- A: Generator temperature () = 82 °C;

- B: Evaporator temperature () = 2.5 °C;

- C: Absorber temperature () = 30 °C;

- D: Condenser temperature () = 35 °C.

6.6. Desirability-Based Multi-Objective Optimization of System Output

6.7. Post Analysis

7. Literature-Based Performance Benchmarking

8. Conclusions, Limitations, and Recommendations

- ANOVA analysis yielded regression models with good prediction accuracy for COP, , and Diagnostic plots, including predicted vs. actual and normal probability charts, confirmed the models’ accuracy and statistical reliability.

- and were identified as the most influential parameters across all responses. also showed a consistent and significant effect, while had a notable impact on and COP, but it was not statistically significant for .

- For COP evaluation, the interactions − and have significant p-values but low F-values, indicating limited relevance. Nonetheless, a low absorber and condenser temperature, combined with a high generator temperature, results in an optimal COP of 0.8065.

- Through single-objective optimization, the system is configured for maximum at low condensing and absorbing temperatures, and high generator and evaporator temperatures, yielding 20.72 kW under the conditions: = 82 °C, = 4.5 °C, = 30 °C, and = 30 °C.

- The single-objective optimization for exergy efficiency identifies the optimal conditions at: = 82 °C, = 2.5 °C, = 30 °C, and = 35 °C, yielding an exergy efficiency of 39.29%.

- In the multi-objective optimization, the RSM optimizer predicts optimal values of COP = 0.7969, = 20.68 kW, and = 36.93%, corresponding to = 78 °C, = 6.5 °C, = 30 °C, and = 30 °C.

- The composite desirability is relatively high (=0.953), indicating that the selected settings yield favorable outcomes across all responses.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Collecting Area, m2 | |

| b0, bi, bii, bij | Regression coefficients for the interception, linear, quadratic, and interaction terms |

| Specific heat capacity, kJ·kg−1·K−1 | |

| Solar collector mass flow rate, kg·s−1 | |

| Mass of water in storage tank, kg | |

| Solar energy input, kW | |

| Heat input to the ST, kW | |

| Physical exergy | |

| thermal heat rate, kW | |

| Coefficient of regression | |

| Adjusted coefficient of regression | |

| Predicted Coefficient of regression | |

| Inlet temperature of the cold side, °C | |

| Inlet temperature of the hot side, °C | |

| Outlet temperature of the hot side, °C | |

| Outlet temperature of the cold side, °C | |

| Heat transfer coefficient, W·m−2·K−1 | |

| Tank Length, m | |

| Tank Volume, m3 | |

| Independent input parameter | |

| Predicted value of the response | |

| h | Specific fluid enthalpy, kJ·kg−1 |

| Ncoll | Number of collectors |

| P | Pressure, kPa |

| s | Specific entropy, kJ·kg−1 |

| T | Temperature, °C |

| Tamb | Ambient Temperature, °C |

| Tf,moy | Mean temperature of the working fluid, °C |

| Tsun | Sun Temperature, K |

| UA | Area product, kW·°C−1 |

| X | Lithium Bromide concentration, - |

| X0 | Center point Value |

| Xᵢ | Actual (uncoded) value |

| xᵢ | Coded value of the i-th variable |

| Xᵢ, Xⱼ | Independent variables |

| Greek Symbol | |

| η0 | Optical efficiency (zero-order coefficient) of the collector, – |

| β0 | Offset term |

| ∈ | Statical error |

| Ė | Exergy |

| ΔX | Step change corresponding to one coded unit of the i-th variable |

| ε | SHX Effectiveness, % |

| η | Efficiency, % |

| ρ | Density, kg/m3 |

| n | Number of factors |

| β | Regression coefficient |

| Abbreviations | |

| abs | Absorber |

| AC | Absorption chiller |

| amb | Ambient |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| BBD | Box–Behnken Design |

| C.V. | Coefficient of variation |

| con | Condenser |

| Cool | Cooling output |

| COP | Coefficient of performance |

| COR | Coefficient of regression |

| Df | Degree of freedom |

| DoE | Design of Experiments |

| EES | Engineering Equation Solver |

| EFPC | Evacuated Flat Plate Collector |

| eva | Evaporator |

| ex | Exergy |

| f | Fluid |

| gen | Generator |

| H2O-LiBr | Water–Lithium bromide |

| HTF | Heat Transfer Fluid |

| in | Inlet, input |

| is | Isentropic |

| LMTD | Log mean temperature difference, °C |

| out, e | Outlet, output |

| ref | Refrigerant (H2O) |

| REV | Refrigerant Expansion Valve |

| RSM | Response Surface Methodology |

| SCR | Solution Circulation Ratio |

| SEV | Solution Expansion Valve |

| SHEX | Solution Heat Exchanger |

| sol | Solar |

| SP | Solution Pump |

| st | Storage tank |

| str | Strong solution (LiBr) |

| Subscripts and Superscripts | |

| tot | Total |

| wf | Working fluid |

| ws | Weak solution |

| dst | Destruction |

| th | Thermal |

References

- Jaiswal, K.K.; Chowdhury, C.R.; Yadav, D.; Verma, R.; Dutta, S.; Jaiswal, K.S.; Sangmesh, B.; Karuppasamy, K.S.K. Renewable and Sustainable Clean Energy Development and Impact on Social, Economic, and Environmental Health. Energy Nexus 2022, 7, 100118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saoud, A.; Bouckchana, Y.; Fellah, A. Design of Solar-Driven Combined Heat and Power System: Parametric Study and Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2025 15th International Renewable Energy Congress (IREC), Hammamet, Tunisia, 2–4 February 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maka, A.O.M.; Alabid, J.M. Solar Energy Technology and Its Roles in Sustainable Development. Clean Energy 2022, 6, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saoud, A.; Boukhchana, Y.; Fellah, A. Performance Investigation and Working Fluid Evaluation for Organic Rankine Cycle Power Plant. In Advances in Science, Technology & Innovation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; He, Y.L.; Li, P.; Du, B.C. A Comprehensive Model for Analysis of Real-Time Optical Performance of a Solar Power Tower with a Multi-Tube Cavity Receiver. Appl. Energy 2017, 185, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Torres, M.; Pérez-Lombard, L.; Coronel, J.F.; Maestre, I.R.; Yan, D. A Review on Buildings Energy Information: Trends, End-Uses, Fuels and Drivers. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of Energy. An Assessment of Energy Technologies and Research Opportunities. (Increasing Efficiency of Building Systems and Technologies). Quadrenn. Technol. Rev. 2015, 38, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bataineh, K.; Taamneh, Y. Review and Recent Improvements of Solar Sorption Cooling Systems. Energy Build. 2016, 128, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahoud, C.; El Brouche, M.; Lahoud, C.; Hmadi, M. A Review of Single-Effect Solar Absorption Chillers and Its Perspective on Lebanese Case. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, N.K. Metaheuristic Energy Efficiency Optimization of Solar-Powered Absorption Cooling Systems under Operating Climactic Conditions Integrated with Explainable AI. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 69, 106016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazrak, A.; Boudehenn, F.; Bonnot, S.; Fraisse, G.; Leconte, A.; Papillon, P.; Souyri, B. Development of a Dynamic Artificial Neural Network Model of an Absorption Chiller and Its Experimental Validation. Renew. Energy 2016, 86, 1009–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Seong, N.C.; Choi, W. Forecasting the Energy Consumption of an Actual Air Handling Unit and Absorption Chiller Using Ann Models. Energies 2020, 13, 4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. Optimization of Cascade Cooling System Based on Lithium Bromide Refrigeration in the Polysilicon Industry. Processes 2021, 9, 1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellos, E.; Tzivanidis, C. Optimum Design of a Solar Ejector Refrigeration System for Various Operating Scenarios. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 154, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saoud, A.; Bruno, J.C.; Boukhchanaa, Y.; Fellah, A. Performance Investigation and Numerical Evaluation of a Single-Effect Double-Lift Absorption Chiller. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 227, 120369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Inzunza, L.A.; Hernández-Magallanes, J.A.; Sandoval-Reyes, M.; Rivera, W. Comparison of the Performance of Single-Effect, Half-Effect, Double-Effect in Series and Inverse and Triple-Effect Absorption Cooling Systems Operating with the NH3–LiNO3 Mixture. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2014, 66, 612–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macriss, R.A.; Gutraj, J.M.; Zawacki, T.S. Absorption Fluids Data Survey: Final Report on Worldwide Data; Oak Ridge National Lab.: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik, S.C.; Kumar, R. Thermodynamic Study of a Two-Stage Vapour Absorption Refrigeration System Using NH3 Refrigerant with Liquid/Solid Absorbents. Energy Convers. Manag. 1985, 25, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Infante Ferreira, C.A. Absorption Heat Pump Cycles with NH3–Ionic Liquid Working Pairs. Appl. Energy 2017, 204, 819–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanel, A.; Seibold, T.; Gebhard, J.; Fendt, S.; Spliethoff, H. Evaluation of Influential Factors on Energy System Optimisation. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 322, 119156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbeke, J.; Runge-Metzger, A.; Slingenberg, Y.; Werksman, J. The Paris Agreement. In Towards a Climate-Neutral Europe; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 24–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EES: Engineering Equation Solver|F-Chart Software: Engineering Software. Available online: https://fchartsoftware.com/ees/ (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Avanessian, T.; Ameri, M. Energy, Exergy, and Economic Analysis of Single and Double Effect LiBr–H2O Absorption Chillers. Energy Build. 2014, 73, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saoud, A.; Boukhchana, Y.; Bruno, J.C.; Fellah, A. Thermodynamic Investigation of an Innovative Solar-Driven Trigeneration Plant Based on an Integrated ORC-Single Effect-Double Lift Absorption Chiller. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2024, 50, 102596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.; Kasaeian, A.; Pourfayaz, F.; Ahmadi, M.H. Thermodynamic Analysis of a Combined Gas Turbine, ORC Cycle and Absorption Refrigeration for a CCHP System. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 111, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellos, E.; Tzivanidis, C.; Antonopoulos, K.A. Exergetic, Energetic and Financial Evaluation of a Solar Driven Absorption Cooling System with Various Collector Types. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 102, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffie, J.A.; Beckman, W.A. Solar Engineering of Thermal Processes, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellos, E.; Tzivanidis, C. Parametric Analysis and Optimization of a Solar Driven Trigeneration System Based on ORC and Absorption Heat Pump. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 161, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellos, E.; Tzivanidis, C.; Antonopoulos, K.A. Exergetic and Energetic Comparison of LiCl-H2O and LiBr-H2O Working Pairs in a Solar Absorption Cooling System. Energy Convers. Manag. 2016, 123, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saoud, A.; Boukhchana, Y.; Fellah, A. Energetic Analysis and Assessment of a Single-Effect LiBr–H2O Absorption Refrigeration System. In Advances in Science, Technology & Innovation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saoud, A.; Boukhchana, Y.; Fellah, A. Thermal and Parametric Investigation of Solar-Powered Single-Effect Absorption Cooling System. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2024, 149, 7469–7484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pátek, J.; Klomfar, J. A Computationally Effective Formulation of the Thermodynamic Properties of LiBr–H2O Solutions from 273 to 500 K over Full Composition Range. Int. J. Refrig. 2006, 29, 566–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pátek, J.; Klomfar, J. A Simple Formulation for Thermodynamic Properties of Steam from 273 to 523 K, Explicit in Temperature and Pressure. Int. J. Refrig. 2009, 32, 1123–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari Kordlar, M.; Mahmoudi, S.M.S. Exergeoconomic Analysis and Optimization of a Novel Cogeneration System Producing Power and Refrigeration. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 134, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petela, R. Exergy of Undiluted Thermal Radiation. Sol. Energy 2003, 74, 469–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilic, M.; Kaynakli, O. Second Law-Based Thermodynamic Analysis of Water-Lithium Bromide Absorption Refrigeration System. Energy 2007, 32, 1505–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellos, E.; Tzivanidis, C.; Pavlovic, S.; Stefanovic, V. Thermodynamic Investigation of LiCl-H2O Working Pair in a Double Effect Absorption Chiller Driven by Parabolic Trough Collectors. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2017, 3, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, B. Total Solar Irradiance and Climate. Adv. Space Res. 2005, 35, 882–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borge, D.; Colmenar, A.; Castro, M.; Martín, S.; Sancristobal, E. Exergy Efficiency Analysis in Buildings Climatized with LiCl–H2O Solar Cooling Systems That Use Swimming Pools as Heat Sinks. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 3161–3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerme, E.D.; Chafidz, A.; Agboola, O.P.; Orfi, J.; Fakeeha, A.H.; Al-Fatesh, A.S. Energetic and Exergetic Analysis of Solar-Powered Lithium Bromide-Water Absorption Cooling System. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 151, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veza, I.; Spraggon, M.; Fattah, I.M.R.; Idris, M. Response Surface Methodology (RSM) for Optimizing Engine Performance and Emissions Fueled with Biofuel: Review of RSM for Sustainability Energy Transition. Results Eng. 2023, 18, 101213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susaimanickam, A.; Manickam, P.; Joseph, A.A. A Comprehensive Review on RSM-Coupled Optimization Techniques and Its Applications. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2023, 30, 4831–4853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Design-Expert|Stat-Ease. Available online: https://www.statease.com/software/design-expert/ (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Wang, J.; Wan, W. Experimental Design Methods for Fermentative Hydrogen Production: A Review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2009, 34, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanioti, S.; Tzia, C. Optimization of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Oil from Olive Pomace Using Response Surface Technology: Oil Recovery, Unsaponifiable Matter, Total Phenol Content and Antioxidant Activity. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 79, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.M.; Chaurasia, R.C.; Suresh, N.; Gajbhiye, P. Application of Artificial Neural Networks and Response Surface Methodology Approaches for the Prediction of Oil Agglomeration Process. Fuel 2018, 220, 826–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, S.C.; Arora, A. Energy and Exergy Analysis of Single Effect and Series Flow Double Effect Water–Lithium Bromide Absorption Refrigeration Systems. Int. J. Refrig. 2009, 32, 1247–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florides, G.A.; Kalogirou, S.A.; Tassou, S.A.; Wrobel, L.C. Design and Construction of a LiBr–Water Absorption Machine. Energy Convers. Manag. 2003, 44, 2483–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, S.; Khormali, A.; Meerovich Khoutoriansky, F. Optimization of the Demulsification of Water-in-Heavy Crude Oil Emulsions Using Response Surface Methodology. Fuel 2022, 323, 124270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emeji, I.C.; Patel, B. Box-Behnken Assisted RSM and ANN Modelling for Biodiesel Production over Titanium Supported Zinc-Oxide Catalyst. Energy 2024, 308, 132765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Ojha, K. Application of Response Surface Methodology for the Optimization of Viscosity of Foam Fracturing Fluids for the Unconventional Reservoir. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2021, 94, 104086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Wahab, M.S.; Abd Rahman, S.; Abu Samah, R. Flux Model Development and Synthesis Optimization for an Enhanced GO Embedded Nanocomposite Membrane through FFD and RSM Approach. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalilibal, Z.; Amiri, A.; Castagliola, P.; Khoo, M.B.C. Monitoring the Coefficient of Variation: A Literature Review. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 161, 107600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M.; Maheshwari, S.; Kundra, T.; Rathee, S. Multi-Response Optimization of Fused Deposition Modelling Process Parameters of ABS Using Response Surface Methodology (RSM)-Based Desirability Analysis. Mater. Today Proc. 2017, 4, 1972–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y.W. Application of Response Surface Methodology and Desirability Approach to Investigate and Optimize the Jet Pump in a Thermoacoustic Stirling Heat Engine. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 127, 1005–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parham, K.; Atikol, U.; Yari, M.; Agboola, O.P. Evaluation and Optimization of Single Stage Absorption Chiller Using (LiCl + H2O) as the Working Pair. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2013, 5, 683157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tahaineh, H.A. Exergetic-Energetic Effectiveness of a Simple H2O-LiBr Absorption Chiller Operated by Solar Energy Collected Using a Direct Flow Evacuated Tube Collector. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2023, 18, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Modi, A. Energy and Exergy Analysis of a Novel Ejector-Assisted Compression–Absorption–Resorption Refrigeration System. Energy 2023, 263, 125760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehadi, M. Optimizing Solar Cooling Systems. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2020, 21, 100663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Xu, H.; Jin, D.; An, W. Research on Geothermal-Driven Single-Effect Absorption Refrigeration Systems with Different Working Fluids: Energy and Exergy Analysis. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2024, 19, 1689–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawalbeh, M.; Salameh, T.; Albawab, M.; Al-Othman, A.; Assad, M.E.H.; Alami, A.H. Parametric Study of a Single Effect Lithium Bromide-Water Absorption Chiller Powered by a Renewable Heat Source. J. Sustain. Dev. Energy Water Environ. Syst. 2020, 8, 464–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| FPC collecting area, | 21 |

| MFR of the collector field, | 0.056 kg· |

| Collector aperture area, | 1.84 |

| Tank thermal loss coefficient, | 0.5 W m2 K−1 |

| Tank volume, | 3.5 |

| Sun temperature, | 5770 K |

| Solar irradiation, | 1000 W/m2 |

| Ambient temperature, | 298 K |

| Generator temperature, | 82 °C |

| Evaporator (cooling) temperature, | 4.5 °C |

| Condenser/absorber temperature, | 35 °C |

| Solution heat exchanger effectiveness, | 65% |

| Factor | Name | Symbol (Units) | Min | Max | Coded Low | Coded High | Mean | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Generator temperature | 78.00 | 86.00 | −1 ↔ 78.00 | +1 ↔ 86.00 | 82.00 | 2.62 | |

| B | Evaporator temperature | 2.50 | 6.50 | −1 ↔ 2.50 | +1 ↔ 6.50 | 4.50 | 1.31 | |

| C | Absorber temperature | 30.00 | 40.00 | −1 ↔ 30.00 | +1 ↔ 40.00 | 35.00 | 3.27 | |

| D | Condenser temperature | 30.00 | 40.00 | −1 ↔ 30.00 | +1 ↔ 40.00 | 35.00 | 3.27 |

| Inputs Parameters | Output Parameters | Kaushik and Aurora [47] | Present Model | Absolute Deviation (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (°C) | 87.8 | (kW) | 3095.70 | 3084 | 0.378 |

| (°C) | 37.8 | (kW) | 2945.27 | 2934 | 0.383 |

| (°C) | 37.8 | (kW) | 2505.91 | 2507 | 0.043 |

| (°C) | 7.2 | (kW) | 2355.45 | 2356 | 0.023 |

| (%) | 70 | (kW) | 518.72 | 525.8 | 1.365 |

| (kg·s−1) | 1 | COP | 0.7609 | 0.764 | 0.407 |

| Inputs Parameters | Output Parameters | Florides et al. [48] | Present Model | Absolute Deviation (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (°C) | 90.00 | (kW) | 14.20 | 3084 | 0.378 |

| (°C) | 34.90 | (kW) | 13.42 | 2934 | 0.383 |

| (°C) | 44.30 | (kW) | 10.78 | 2507 | 0.043 |

| (°C) | 6.00 | (kW) | 10.00 | 10.00 | __ |

| (kW) | 0.29 | 0.29 | __ | ||

| (kg·s−1) | 0.053 | COP | 0.704 | 0.764 | 0.407 |

| Components | Heat Transfer Rate (kW) | Heat Transfer Characteristics- Area Product (kW·C−1) |

|---|---|---|

| Generator | = 14.60 | = 1.400 |

| Condenser | 11.09 | = 3.503 |

| Evaporator | = 14.03 | = 3.455 |

| Absorber | = 11.66 | = 2.364 |

| Solution Heat Exchanger | = 2.63 | - |

| Performance Indicators | ||

| Coefficient of Performance (COP) | 0.7596 | |

| ) | 0.528 | |

| ) | 0.3495 | |

| 0.042 | ||

| Run N° | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) | COP (-) | (kW) | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 78 | 2.5 | 35 | 35 | 0.6934 | 5.472 | 37.5 |

| 2 | 86 | 4.5 | 35 | 40 | 0.7334 | 9.539 | 31.88 |

| 3 | 78 | 4.5 | 35 | 30 | 0.782 | 12.5 | 38.25 |

| 4 | 86 | 2.5 | 35 | 35 | 0.7479 | 11.55 | 35.94 |

| 5 | 78 | 4.5 | 35 | 40 | 0.5782 | 2.671 | 28.28 |

| 6 | 82 | 6.5 | 35 | 40 | 0.7416 | 8.844 | 30.57 |

| 7 | 82 | 2.5 | 35 | 40 | 0.625 | 3.872 | 31.79 |

| 8 | 82 | 2.5 | 40 | 35 | 0.6389 | 3.781 | 32.49 |

| 9 | 78 | 6.5 | 35 | 35 | 0.7711 | 10.43 | 33.8 |

| 10 | 86 | 4.5 | 35 | 30 | 0.7859 | 17.75 | 34.16 |

| 11 | 82 | 4.5 | 35 | 35 | 0.7597 | 11.03 | 34.95 |

| 12 | 78 | 4.5 | 30 | 35 | 0.7856 | 13.71 | 38.43 |

| 13 | 86 | 6.5 | 35 | 35 | 0.7846 | 16.25 | 30.56 |

| 14 | 82 | 6.5 | 30 | 35 | 0.8065 | 19.42 | 33.24 |

| 15 | 86 | 4.5 | 40 | 35 | 0.7329 | 8.912 | 31.86 |

| 16 | 82 | 4.5 | 40 | 30 | 0.7584 | 10.32 | 34.89 |

| 17 | 82 | 4.5 | 35 | 35 | 0.7597 | 11.03 | 34.95 |

| 18 | 82 | 2.5 | 35 | 30 | 0.7685 | 12.95 | 39.09 |

| 19 | 82 | 4.5 | 30 | 40 | 0.7632 | 12.14 | 35.11 |

| 20 | 86 | 4.5 | 30 | 35 | 0.7918 | 19.35 | 34.42 |

| 21 | 82 | 2.5 | 30 | 35 | 0.7725 | 14.06 | 39.29 |

| 22 | 82 | 4.5 | 30 | 30 | 0.8064 | 20.72 | 37.1 |

| 23 | 82 | 4.5 | 35 | 35 | 0.7597 | 11.03 | 34.95 |

| 24 | 82 | 6.5 | 35 | 30 | 0.8007 | 17.64 | 33 |

| 25 | 82 | 4.5 | 35 | 35 | 0.7597 | 11.03 | 34.95 |

| 26 | 82 | 6.5 | 40 | 35 | 0.742 | 8.204 | 30.58 |

| 27 | 82 | 4.5 | 35 | 35 | 0.7597 | 11.03 | 34.95 |

| 28 | 82 | 4.5 | 40 | 40 | 0.3936 | 1.058 | 18.11 |

| 29 | 78 | 4.5 | 40 | 35 | 0.6029 | 2.675 | 29.49 |

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F-Value | p-Value | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 0.1944 | 8 | 0.0243 | 21.21 | <0.0001 | Significant |

| A − | 0.0110 | 1 | 0.0110 | 9.60 | 0.0057 | |

| B − | 0.0134 | 1 | 0.0134 | 11.66 | 0.0028 | |

| C − | 0.0612 | 1 | 0.0612 | 53.46 | <0.0001 | |

| D − | 0.0626 | 1 | 0.0626 | 54.66 | <0.0001 | |

| AD | 0.0057 | 1 | 0.0057 | 5.00 | 0.0370 | |

| CD | 0.0259 | 1 | 0.0259 | 22.57 | 0.0001 | |

| C2 | 0.0066 | 1 | 0.0066 | 5.72 | 0.0267 | |

| D2 | 0.0100 | 1 | 0.0100 | 8.71 | 0.0079 | |

| Residual | 0.0229 | 20 | 0.0011 | |||

| Lack of Fit | 0.0229 | 16 | 0.0014 | |||

| Pure Error | 0.0000 | 4 | 0.0000 | |||

| Cor Total | 0.2173 | 28 |

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F-Value | p-Value | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 767.41 | 14 | 54.82 | 44,636.19 | <0.0001 | Significant |

| 107.36 | 1 | 107.36 | 87,422.89 | <0.0001 | ||

| 70.58 | 1 | 70.58 | 57,475.29 | <0.0001 | ||

| 346.15 | 1 | 346.15 | 2.819 × 105 | <0.0001 | ||

| 240.81 | 1 | 240.81 | 1.961 × 105 | <0.0001 | ||

| AB | 0.0166 | 1 | 0.0166 | 13.55 | 0.0025 | |

| AC | 0.0891 | 1 | 0.0891 | 72.56 | <0.0001 | |

| AD | 0.6545 | 1 | 0.6545 | 532.95 | <0.0001 | |

| BC | 0.2195 | 1 | 0.2195 | 178.73 | <0.0001 | |

| BD | 0.0199 | 1 | 0.0199 | 16.19 | 0.0013 | |

| CD | 0.1163 | 1 | 0.1163 | 94.69 | <0.0001 | |

| A2 | 0.1584 | 1 | 0.1584 | 129.02 | <0.0001 | |

| B2 | 0.0173 | 1 | 0.0173 | 14.12 | 0.0021 | |

| C2 | 0.5318 | 1 | 0.5318 | 433.05 | <0.0001 | |

| D2 | 0.4281 | 1 | 0.4281 | 348.64 | <0.0001 | |

| Residual | 0.0172 | 14 | 0.0012 | |||

| Lack of Fit | 0.0172 | 10 | 0.0017 | |||

| Pure Error | 0.0000 | 4 | 0.0000 | |||

| Cor Total | 767.43 | 28 |

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F-Value | p-Value | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 0.0437 | 9 | 0.0049 | 22.49 | <0.0001 | Significant |

| A − | 0.0004 | 1 | 0.0004 | 1.85 | 0.1894 | |

| B − | 0.0049 | 1 | 0.0049 | 22.88 | 0.0001 | |

| C − | 0.0134 | 1 | 0.0134 | 62.26 | <0.0001 | |

| D − | 0.0138 | 1 | 0.0138 | 64.07 | <0.0001 | |

| AC | 0.0010 | 1 | 0.0010 | 4.71 | 0.0428 | |

| AD | 0.0015 | 1 | 0.0015 | 6.84 | 0.0170 | |

| CD | 0.0055 | 1 | 0.0055 | 25.32 | <0.0001 | |

| C2 | 0.0014 | 1 | 0.0014 | 6.42 | 0.0203 | |

| D2 | 0.0021 | 1 | 0.0021 | 9.95 | 0.0052 | |

| Residual | 0.0041 | 19 | 0.0002 | |||

| Lack of Fit | 0.0041 | 15 | 0.0003 | |||

| Pure Error | 0.0000 | 4 | 0.0000 | |||

| Cor Total | 0.0478 | 28 |

| System Outputs | COP | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ) | 0.8946 | 1.0000 | 0.9142 |

| 0.8524 | 1.0000 | 0.8735 | |

| 0.6667 | 0.9999 | 0.7155 | |

| ) | 0.1857 | 0.00001 | 0.158 |

| Adequate Precision | 19.4586 | 781.6910 | 20.5716 |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 4.63 | 0.3186 | 4.37 |

| Mean | 0.7312 | 11 | 0.3361 |

| Std. Dev. | 0.0338 | 0.0350 | 0.0147 |

| Output Parameter | Predicted Value | Std. Error | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | Within CI? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COP | 0.7971 | 0.0468 | 0.6995 | 0.8948 | Yes |

| Cooling Capacity (kW) | 20.6593 | 0.0617 | 20.5269 | 20.7916 | Yes |

| Exergy Efficiency (%) | 36.9371 | 2.1610 | 32.4140 | 41.4602 | Yes |

| Study | (°C) | (°C) | / (°C) | COP (-) | (kW) | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parham et al. [56] | 46.2 | 15 | 30/30 | 0.90 | N.A. 1 | 32.99 |

| Al-Tahaineh [57] | 90 | 5–10 | N.A. 1 | 0.75–0.81 | 10 kW | ~35–36 |

| Shehadi [59] | 70–85 | 10 | 30 | 0.776 | N.A. 1 | N.A. 1 |

| Kilic & Kaynakli [36] | 80–95 | 5–10 | 30–40 | 0.75–0.80 | N.A. 1 | 25–35 |

| Kumar et al. [58]. | 95 | 7 | 25/40 | 0.947 | N.A. 1 | 21.80 |

| Saoud et al. [31]. | 82 | 4.5 | 35 | 0.749 | 11.03 | 62.2 |

| Zaho et al. [60] | ~90 | N.A. 1 | N.A. 1 | 0.795 | N.A. 1 | N.A. 1 |

| Tawalbeh et al. [61]. | ~80–100 | N.A. 1 | N.A. 1 | ~0.70 | ~16 | N.A. 1 |

| This study | 78 | 6.5 | 30 | 0.797 | 20.68 | 36.93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saoud, A.; Bruno, J.C. Towards Improved Efficiency of Low-Grade Solar Thermal Cooling: An RSM-Based Multi-Objective Optimization Study. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11518. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111518

Saoud A, Bruno JC. Towards Improved Efficiency of Low-Grade Solar Thermal Cooling: An RSM-Based Multi-Objective Optimization Study. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(21):11518. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111518

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaoud, Abdelmajid, and Joan Carles Bruno. 2025. "Towards Improved Efficiency of Low-Grade Solar Thermal Cooling: An RSM-Based Multi-Objective Optimization Study" Applied Sciences 15, no. 21: 11518. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111518

APA StyleSaoud, A., & Bruno, J. C. (2025). Towards Improved Efficiency of Low-Grade Solar Thermal Cooling: An RSM-Based Multi-Objective Optimization Study. Applied Sciences, 15(21), 11518. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111518