Abstract

The aim of this paper is to provide some concrete evidence, based on the literature review, about the reliability and validity of various Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) tools in the educational process aiming to cultivate speaking and writing skills of learners of English as a second/foreign language (EFL). For this purpose, the PRISMA methodology was employed to secure an academically accepted and valid overview of the literature on the relevant topic. After the exclusion process, 54 studies, within the years 2024–2025, were carefully analyzed. Our discussion centers around the most well-cited benefits and limitations of GenAI-induced tools in the EFL context. The most important findings highlight the significance of employing GenAI tools alongside human teachers in the learning process, as these tools provide learners with opportunities to practice the foreign language in a stress-free, authentic, and stimulating environment. The results were further discussed by reviewing the main benefits, limitations, and pedagogical implications of the proposed use of GenAI in the educational process. Several limitations were acknowledged so as to provide guidelines for future research in this area. This systematic review has been registered through PROSPERO (ID: 1126543).

1. Introduction

In today’s world, Artificial Intelligence and intelligent chatbot agents prevail in every aspect of humans’ lives. Artificial Intelligence (AI) can be found in the form of chatbots, which provide answers based on inserted text and voice commands, and which respond to a spoken stimuli set by the user. Additionally, in the two applications of Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR), users find themselves within a new environment where they have to respond to tasks, carry out duties, or even acquire new skills. No matter what the form of an AI tool is, it can be incorporated in various domains, i.e., healthcare, marketing, sales, entertainment, and foreign language teaching [1]. In this respect, this article is written with the aim of providing insights into the current trend of learning English as a second/foreign language with the aid of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) tools that provide students with relevant flexibility, without time or place constraints [2].

To be more precise, a distinction between Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools and Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) tools should be drawn. Firstly, AI has been utilized in language education for a long time, focusing merely on grammar corrections, based on predefined strict rules, or on automated corrections on inserted written texts. In contrast, GenAI technologies are more recent developments that merely focus on production that leads to a final result, either in written or spoken form. This product imitates authentic situations, resembling an answer that could be provided by a human. In these terms, and since the scope of this paper is EFL instruction through authentic communication, GenAI’s ability to generate and resemble authentic communication, thereby fostering practice, aligns with our research questions.

The present review has chosen to focus on the skills of writing and speaking, referred to as the productive skills, instead of the receptive skills of listening and reading. These skills pose a considerable challenge to learners to acquire, but at the same time they are central to communicative competence [3,4]. In other words, while the receptive skills of listening and reading are necessary for learners to receive and evaluate input, productive skills are essential for real communication and meaningful interactions to take place [5,6]. In these terms, recent research has emphasized GenAI exploitation to practice productive skills through chatbots that enhance drafting and dialogue exchanges, as well as timely personalized feedback [7].

In order to address these issues, a systematic analysis was chosen because the present paper aims to provide answers to a particular area of research in the form of a structured analysis. Furthermore, another reason that a systematic analysis was chosen is to present reliable conclusions that can be generalized without the risk of being biased against ethnicity, personal preferences, or even gender [8,9].

2. Theoretical Background

Recent second/foreign language (L2) acquisition theories highlight the importance of the cultivation of productive skills in the foreign language in order for the learner to become an active member of the universal world. Researchers have pointed out the benefits of the use of advanced technological systems in education that help to achieve higher levels of competency among students [10,11]. One such case is the theory of Machine Learning (ML) which is considered to be a sub-field of GenAI, in which algorithms enable specialized machines to perform tasks that were only possible for humans in the past. Combined with the idea of Personalized Language Learning (PLL) theories, educational designers promise to create an approach centered around the student and their needs. As a result, there will be a system that adapts to the learner and not the opposite [12]. In this optimum educational system, the learners themselves will be able to design, and responsible for the design of, their own experiences, with a focus on their personal interests, monitoring, and assessing their progress while gaining access to resources that suit their linguistic proficiency, capabilities, and preferences.

Based on these theoretical perspectives, the research questions of the present paper are directly linked to how ML and PLL principles intersect with the affordances of GenAI tools. In terms of ML, its adaptability enables real-time, individualized feedback, while in terms of the PLL approach, the learning process should optimally foster learner autonomy and engagement. When applied to an EFL context, these principles align closely with the focus of the present paper, which is to explore writing and speaking fluency through GenAI mediation. In these terms, GenAI-induced feedback supports drafting, idea generation, and revisions in the writing domain, whereas in the speaking domain, roleplay exchanges can promote spontaneous practice, leading to fluency in the foreign language. By explicitly connecting the theoretical approaches to our research scope, we propose GenAI as a complementary tool, and not as a replacement for human contribution, that can promote enhanced learning outcomes in authentic and supporting environments.

In other words, the combination of ML and GenAI into language acquisition has attracted scientific interest recently. This is because the combination of these two theories in the learning process can offer customized foreign language programs to address specific challenges in acquiring newly inserted information, with a focus on the cultivation of the productive skills of writing and speaking. Interactive competence, as the ultimate result of productive skills enhancement, enables students to engage in interactions by transforming them into active speakers and learners, a skill necessary in real-world situations. Communicative and interactive competencies are the goal of all communicative approaches to foreign language teaching. The use of GenAI dialog systems in this particular learning process has been proven helpful in creating interactive activities that can strengthen learners’ competence [13,14,15]. Through these activities, learners are given the chance to exercise language production in realistic contexts via using all the resources they have available [16]. Thus, interaction and communication needs are satisfied with the use of chatbots at the same time, without as much effort on the behalf of the educators.

Furthermore, GenAI technologies can be widely employed in various learning environments with an emphasis on foreign language ones, as they boost experiential learning approaches. Deeply rooted in the communicative learning theories of Canale and Swain’s (1980) model of communicative competence [3], Long’s (1996) Interaction Hypothesis [17] and Swain’s (1985) Output Hypothesis [4] posit that exposure to experiential target language scenarios, based on real-life situations, can offer the learners valuable experiences that can help them to become active speakers. In this sense, the development of GenAI-based software applications that can conduct conversations, via spoken messages or written messages, will enable learners to further enhance their experiences with the foreign language. Relevant research on the benefits of using chatbots in the learning process has been in the spotlight because of the capacity of those systems to provide immediate feedback as a response to an inserted message (either spoken or written), in this way boosting comprehension and the production of foreign language skills [1,18,19,20]. The results of equivalent studies pinpoint the importance of chatbots both as a learning aid but also as an autonomous learning tool that can be used outside of structured environments. Moreover, evidence indicates that foreign language learners show remarkable interest in using chatbots, since they are accessible anytime and anywhere, and learners feel more confident using chatbots for language learning [18,21].

Among the recent relevant studies that examine the use of chatbots in EFL contexts, a substantial number of them rely specifically on ChatGPT(3.5 and/or 4). Such a study is the systematic review of Chung Kwan Lo et al., (2024) [22], who report on multiple comparative studies that have utilized ChatGPT for writing instruction, and so too is the study of Hoang Mai Tram et al. (2024) [23], who also center their analysis around the use of the same tool. The use of ChatGPT, as a dominant tool, is regarded as a language processing software, which not only answers user queries and completes user-assigned tasks, but also optimizes its performance continuously. Specifically, ChatGPT is a facilitator of language learning and can be a transformative force in the role of foreign language instructors, who become guides rather than knowledge providers to their students [24]. The instructors can improve their roles in accordance with the communicative and constructivist theories only if they become familiar and fully informed of the new technological characteristics. Traditional foreign language instruction lacks the ability to facilitate individualized educational needs in terms of materials, cultural components, and constructive assessments. GenAI generated lessons and activities can effectively address problems, like the lack of adequate instructional time, physical space constraints, the lack of resources that assimilate real-life situations, and non-conversational assessment methods.

In these terms, the ultimate purpose of the present research is to investigate the use of GenAI-supported tools in foreign language teaching in order to foster English as a second/foreign language, and to foster the acquisition of the productive skills of writing and speaking. In this sense, we aim to provide a clear overview of the studies that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria, based on the reported benefits and limitations of the tools when utilized in practice. This analysis will prove beneficial in drawing conclusions about the effectiveness of these tools that are generated with GenAI assistance, along with instructional guidelines for educators and policy designers. For these reasons, the research questions (RQ) that guide the present paper are the following:

- In what areas is the use of GenAI technology effective in the acquisition of EFL writing skills?

- In what areas is the use of GenAI technology effective in the acquisition of EFL speaking skills?

- What limitations and challenges are reported in the selected studies regarding the use of GenAI technology in EFL?

3. Methods

In order for the present paper to include a valid and reliable analysis, the PRISMA methodology was employed. Since the ultimate purpose was to discuss the effects of GenAI, we had to include all the different terms that could appear in the expected results. Following that, and since the aim our aim was an analysis of EFL acquisition, we further chose some appropriate keywords. Finally, based on communicative approaches of language teaching and EFL acquisition, we wanted to focus on the productive skills of speaking and writing, highlighting the beneficial effect of technology on them.

To this end, and after carefully researching the relevant domain, taking into account the research scope, the following keywords were inserted into Scopus and Web of Science databases, since they include a broad coverage of peer-reviewed international publications.

(“Artificial Intelligence” OR “AI”) AND (“language learning” OR “language acquisition” OR “foreign language” OR “language education”) AND (“speaking” OR “writing”)

Subsequently, the extraction method included some predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria that were consistently implemented in both databases. The inclusion criteria set for this study were as follows:

- Time span of 2024–2025, in order to report the most current trends of GenAI on EFL.

- Linguistics and educational subject area categories of articles were selected since this search is implemented from an educational standpoint.

- Journal articles written in English.

- Research that focused on the acquisition of EFL.

- Research that used quantitative means of measurements, quasi-experimental, or mixed methodology.

- Studies that utilize GenAI tools. At this point, it should be mentioned that we included tools that had some elements of GenAI technologies and were not exclusively constructed on the idea of producing human-like products.

On the other hand, the exclusion criteria set for this study were as follows:

- Any articles published before the set date of 2024.

- Mechanics or computer technologies subject area categories of articles.

- Studies that did not make a direct reference to a GenAI tool or tools.

- Studies written in languages other than English.

- Literature overviews and systematic or scoping reviews.

- Studies that made reference to L2 acquisition which was other than the English language.

- Studies that included qualitative means of measurements, in order to ensure empirical focus on skill development.

- Studies that examined relevant topics in accordance with students’ or teachers’ views and perceptions. We deliberately excluded studies that based their results solely on students’ or teachers’ perceptions, as we primarily wanted to focus on empirical outcomes. Thus, we intended to focus on the measured effects on writing and speaking skills, as well as documented challenges and limitations, within empirical contexts.

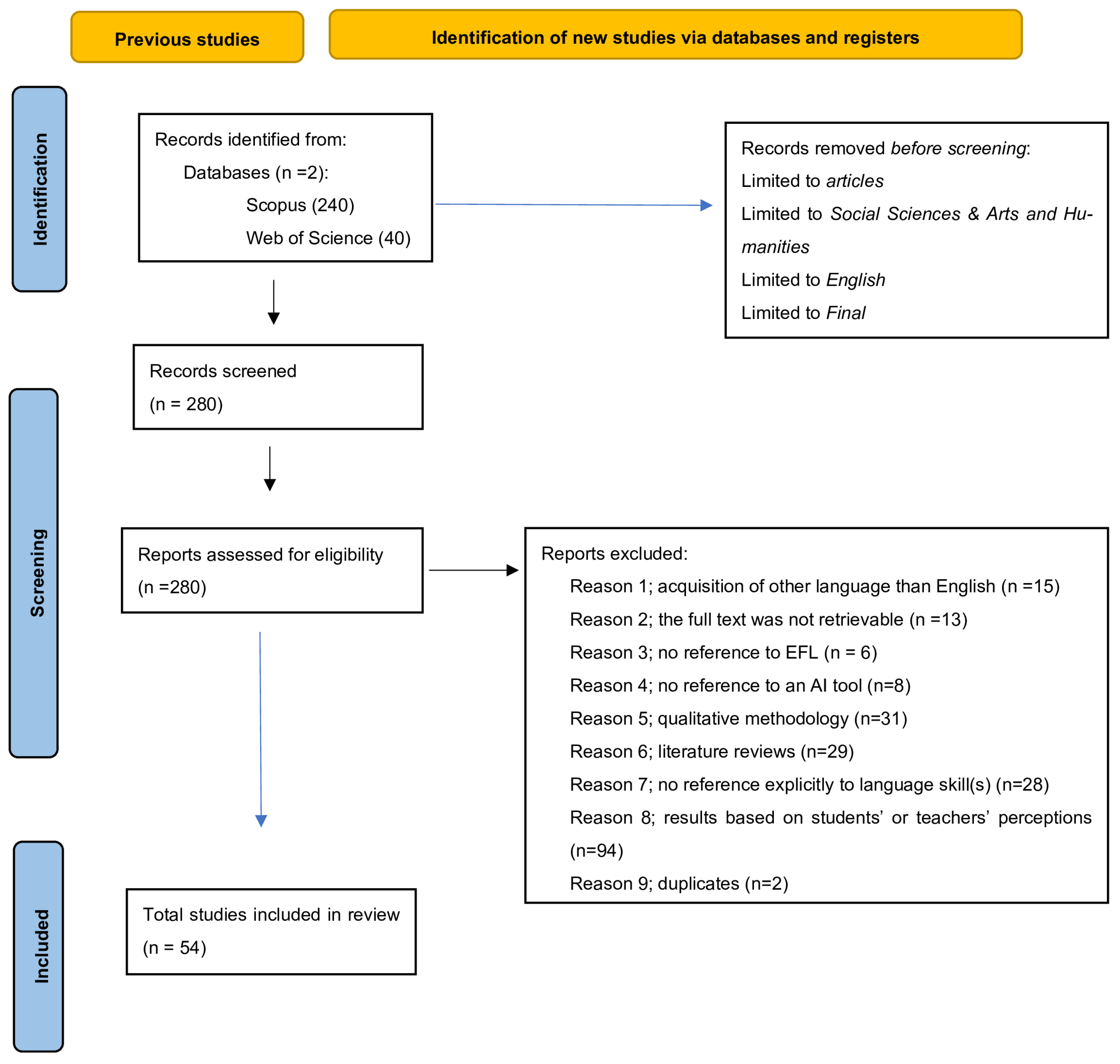

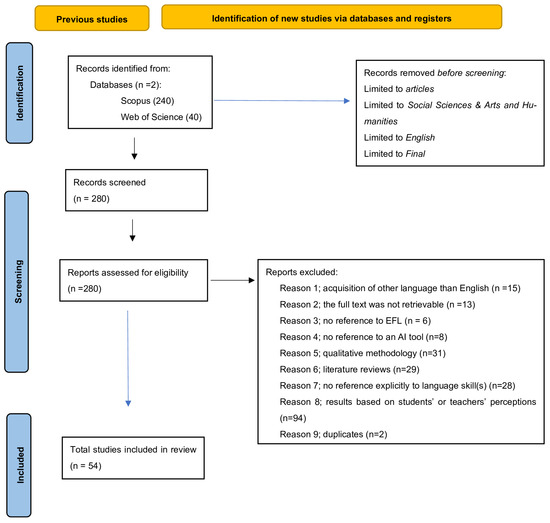

The total number of results of the search, conducted in May 2025, was 280. This was obtained from the total number of Web of science (40) and Scopus (240) results. During the screening process, all the titles, abstracts, keywords, and methodology sections of the articles were read through carefully and discussed in order to guarantee the validity of the present study.

Carefully excluding data that did not meet our research scope led to a total of 56 articles, eliminating 2 duplicate entries. By the end of the screening step, a total of 54 articles were finally selected for analysis and discussion, as is apparent from the following PRISMA diagram (see Figure 1), adopted from Page et al. (2021) [25].

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart [25].

Each researcher worked independently. Firstly, we conducted a pilot data extraction scheme, with five studies per researcher. Any conflicts were resolved through conversation or the intervention of a third independent researcher. At the data extraction stage, we focused our study on the extraction of specific elements. Generally, we focused our research on study characteristics (i.e., authors, year of publication, and country the study took place), participants (i.e., age, number of participants, and level of English), intervention (i.e., type of GenAI tool, length of the intervention, and time span from the pre- to the post-testing), main results (accuracy, reliability of the results, scores in writing or speaking, and basic limitations), methodological features (i.e., study design, methods, and types of tests to lead the analyses). If any of this information was missing or misleading, we discussed the options carefully and reached a consensus after pre-defining some criteria. In the case of a complete lack of information, we did not use the equivalent data in our analyses. One assumption that was made before data extraction took place was in the case that an age span was reported, for example, 10–12; then, the mean would be calculated in the final analyses.

In order to enhance the transparency and credibility of the results, as well as to ensure that there are no duplicates of a similar study conducted, this systematic review is formally registered through PROSPERO, an international database for the prospective registration of systematic reviews. In the registration process, all the necessary details were mentioned in order to ensure the validity and effectiveness of this review as a systematic review. The PROSPERO ID under which the present study has been credited is 1126543.

4. Results

After the PRISMA method was implemented, the final dataset was inserted into Canvas in order to prepare a table with all the necessary information for this publication (Table 1). In the first column is the name of the author or authors, whereas the second contains the title of the published article. The next rows contains information about the year of the publication, the GenAI tool or tools used in the study, the type of methodology employed, the country the study took place in, and the number of participants. The information is presented in accordance with the details that were available in the screening process. In some specific cases, there was no direct reference to the details and as a result no information was inserted in the corresponding row.

Table 1.

Summary of results.

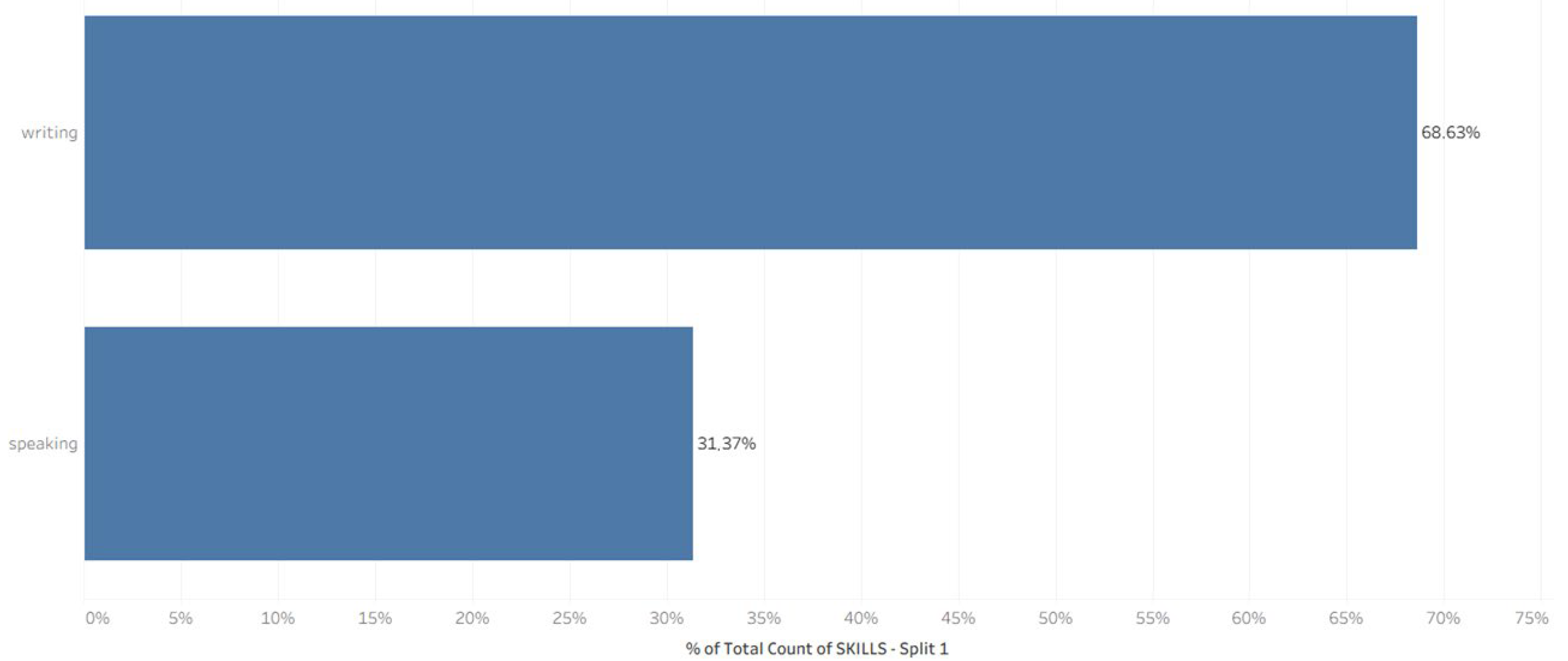

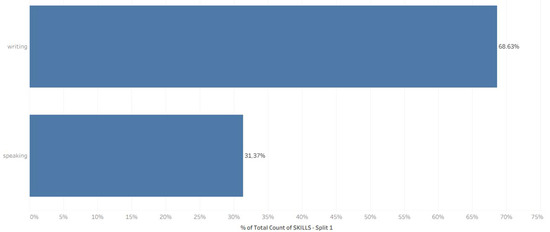

In the next analysis, the tool of Tableau, a software platform for interactive data analytics and visualization, was utilized. Multiple analyses were run using the original dataset that was inserted. Figure 2 shows the number of studies that have been conducted which focus on writing or speaking skills. In this particular scheme, there is a clear precedence of the writing skills (68.63%) compared to the speaking skills (31.37%).

Figure 2.

Number of studies on EFL writing and speaking skills.

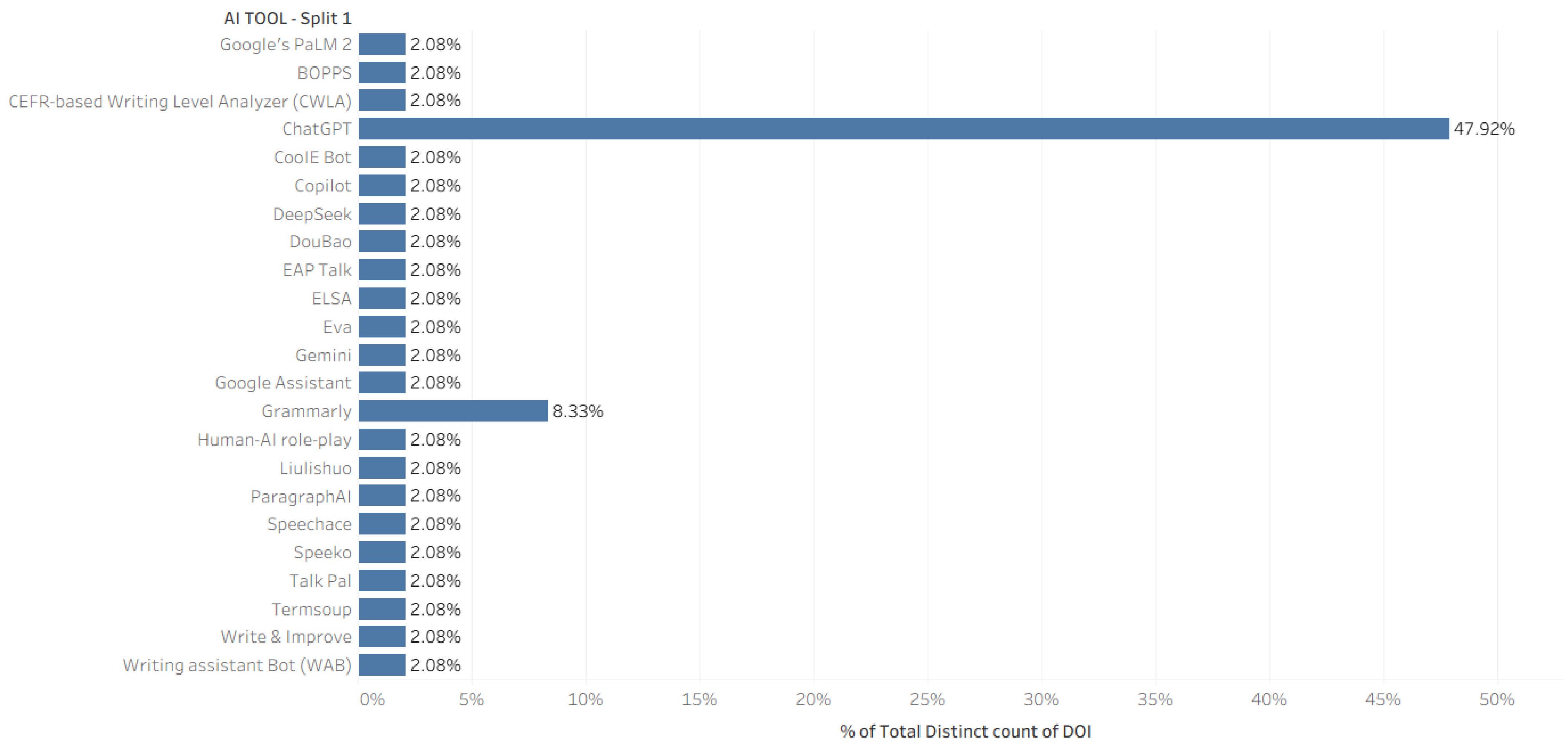

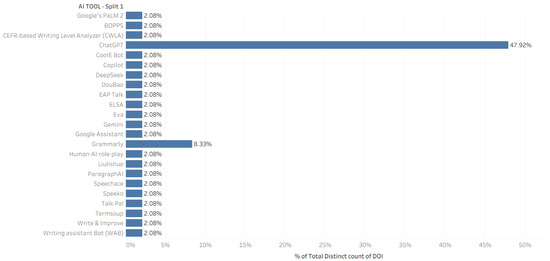

Figure 3 was created in order to visualize the results of the tools used in the dataset and their frequency of use. Most of the apps referred to only one study, with the exception of ChatGPT (47.92%), and Grammarly (8.33%).

Figure 3.

GenAI Tools and their frequencies.

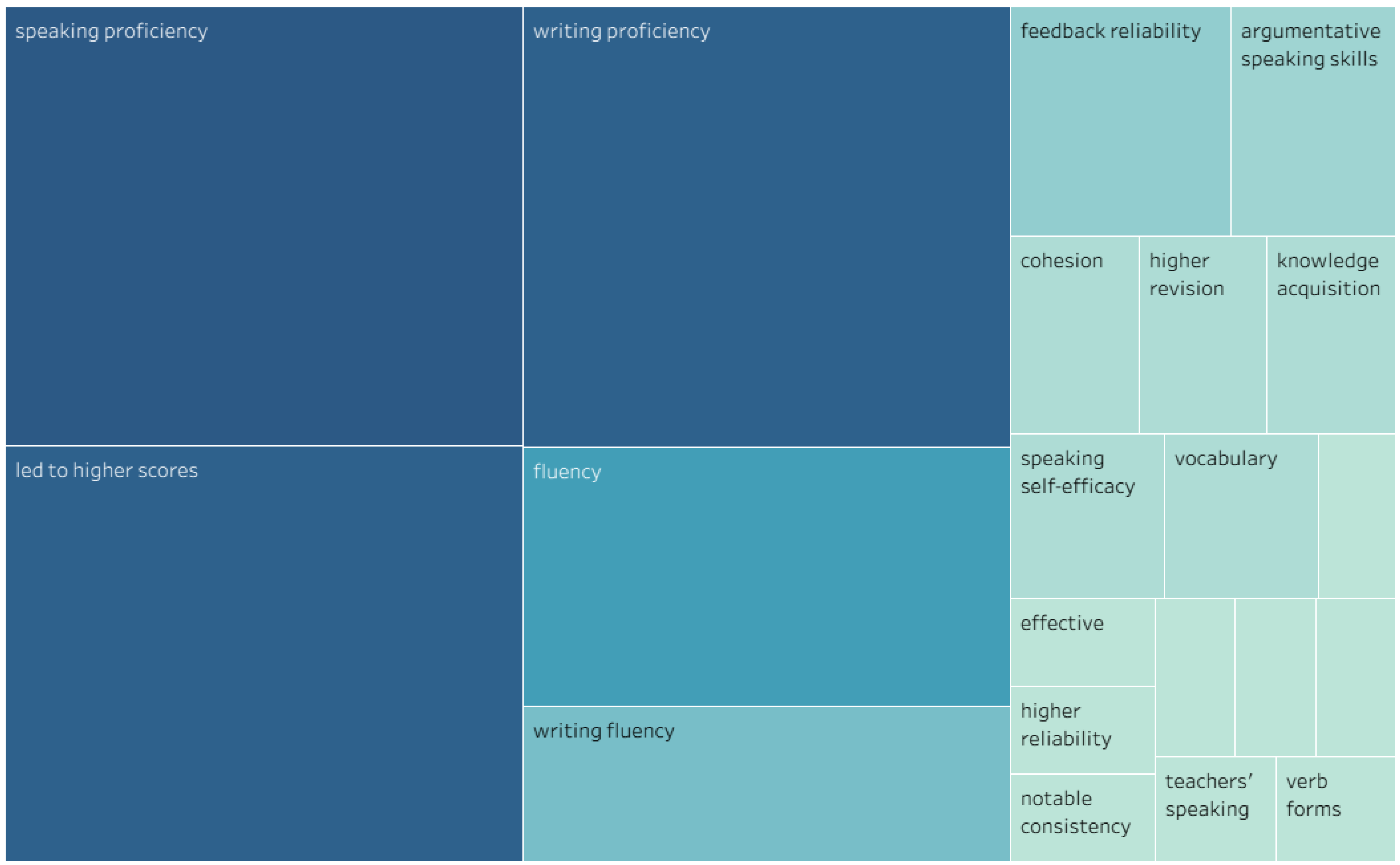

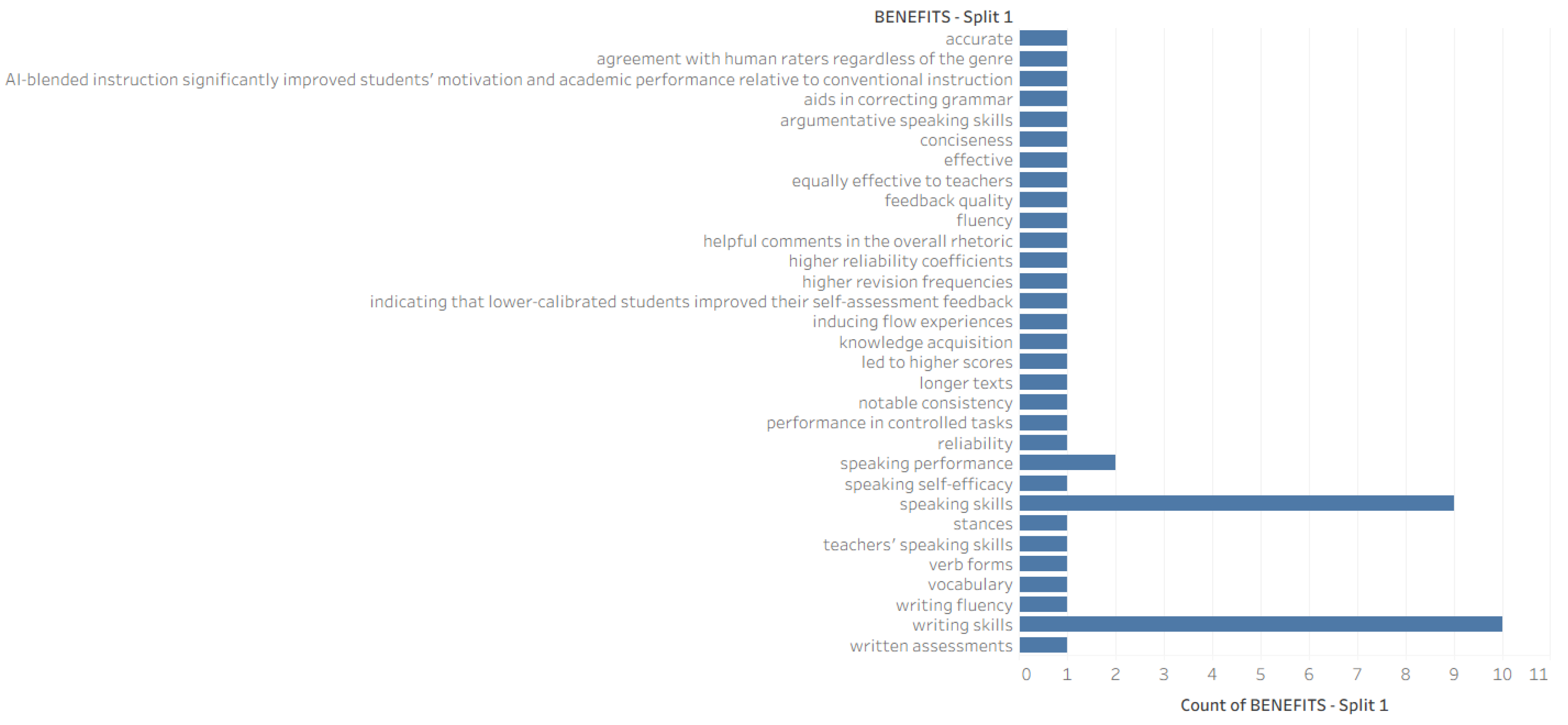

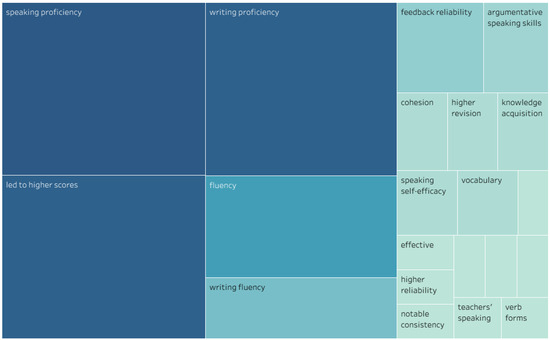

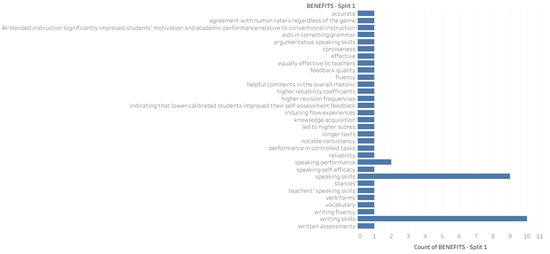

Figure 4 gives a coherent depiction of the benefits reported by researchers in their studies. The size and the color intensity of the rectangle is representative of their frequency in the studies. Enhancement of speaking and writing skills are the most frequently referred to advantages when using GenAI in the EFL classrooms. Since some labels were not able to be imprinted because of their increased length, Figure 5 gives a more precise picture of the results based on the benefits of GenAI use.

Figure 4.

Visualization of the frequency of Generative AI tools used in reviewed EFL studies.

Figure 5.

Reported benefits of GenAI tools used.

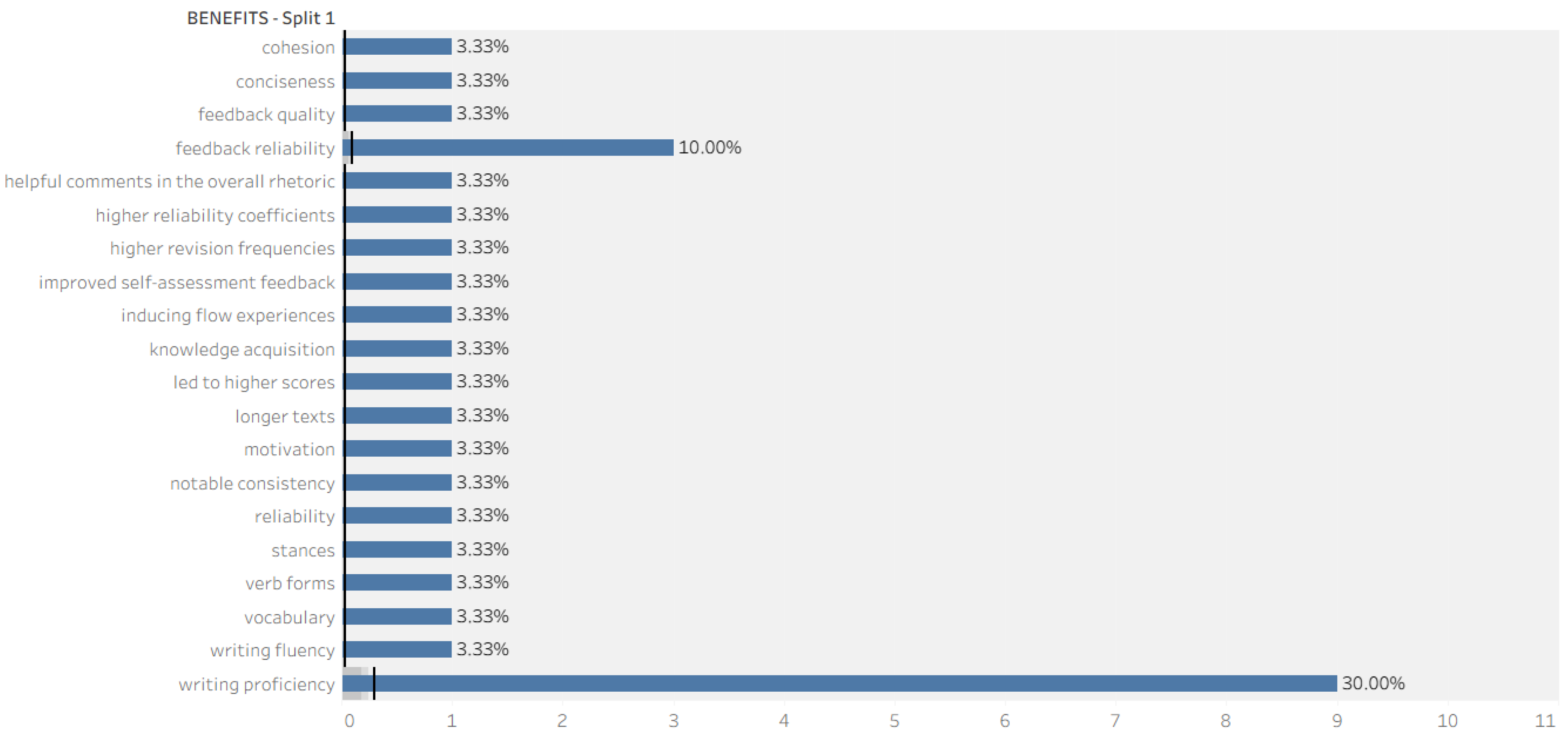

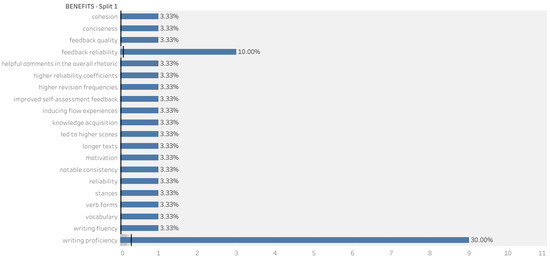

4.1. RQ1: Benefits on Writing Skills

In order to focus our results and answer the first research question regarding the reported main benefits of using of GenAI to boost the written skills of learners, Figure 6 was created. In this figure, the basic areas of improvement with relevance to written skills are documented in the labels, in accordance with their percentages on the second axis. The element of writing proficiency in written texts produced by learners themselves has the highest score, appearing more frequently in relevant studies (30%), whereas the feedback reliability of the GenAI in writing skills is the second most common reported advantage (10%).

Figure 6.

Benefits on writing skills acquisition.

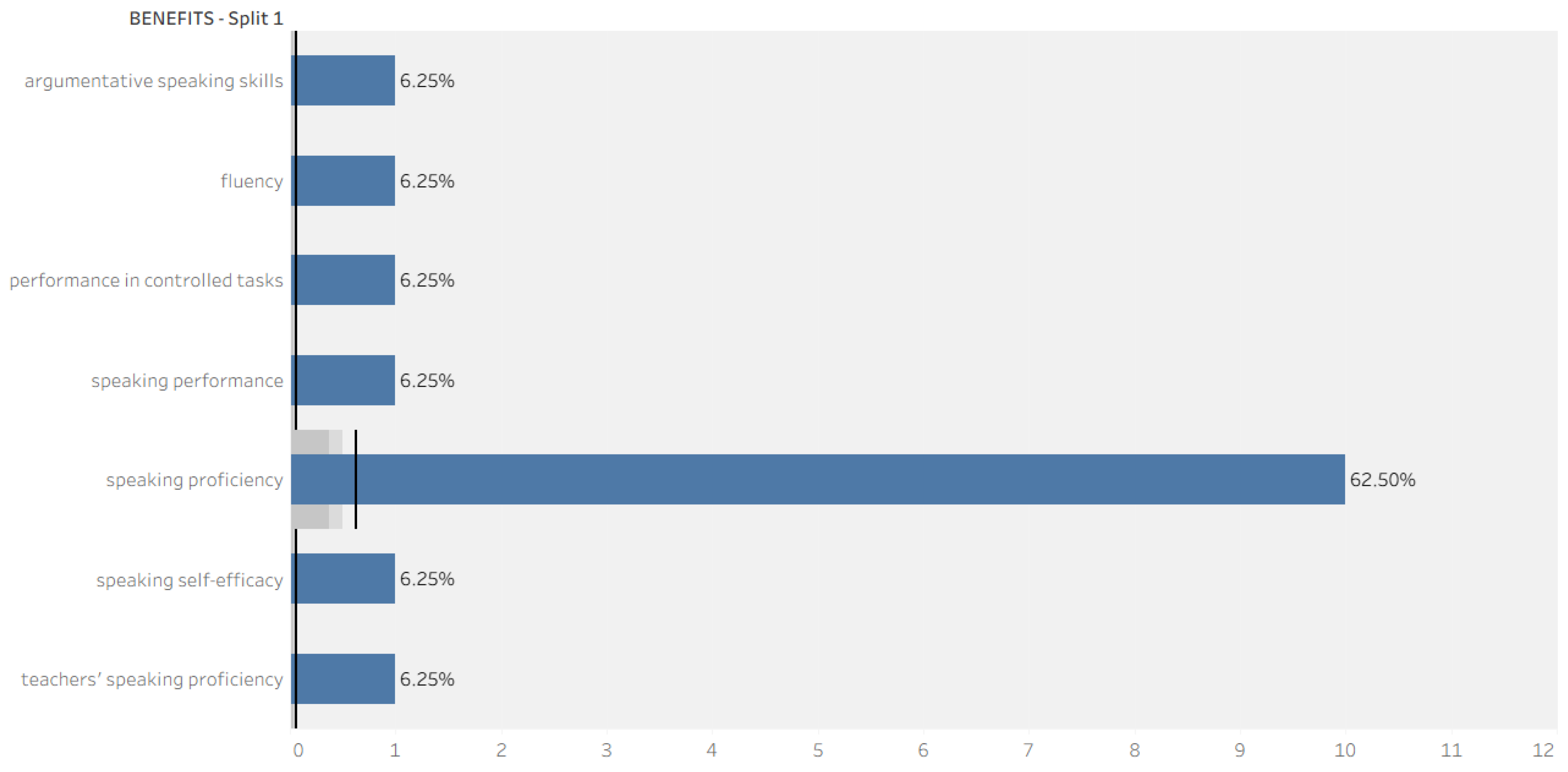

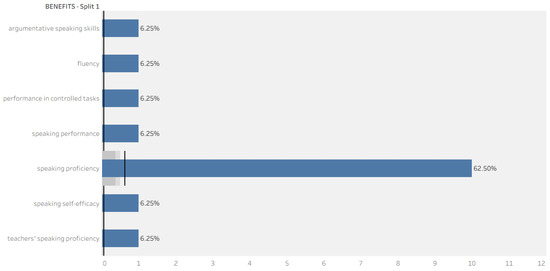

4.2. RQ2: Benefits on Speaking Skills

In relevance to the reported benefits in terms of speaking skills, Figure 7 was created through the use of the same tool, Tableau. In this figure, information regarding the enhancement of speaking skills is imprinted. Specifically, the benefit of proficiency in spoken language appears more frequently in the literature (62.5%).

Figure 7.

Benefits on speaking skills acquisition.

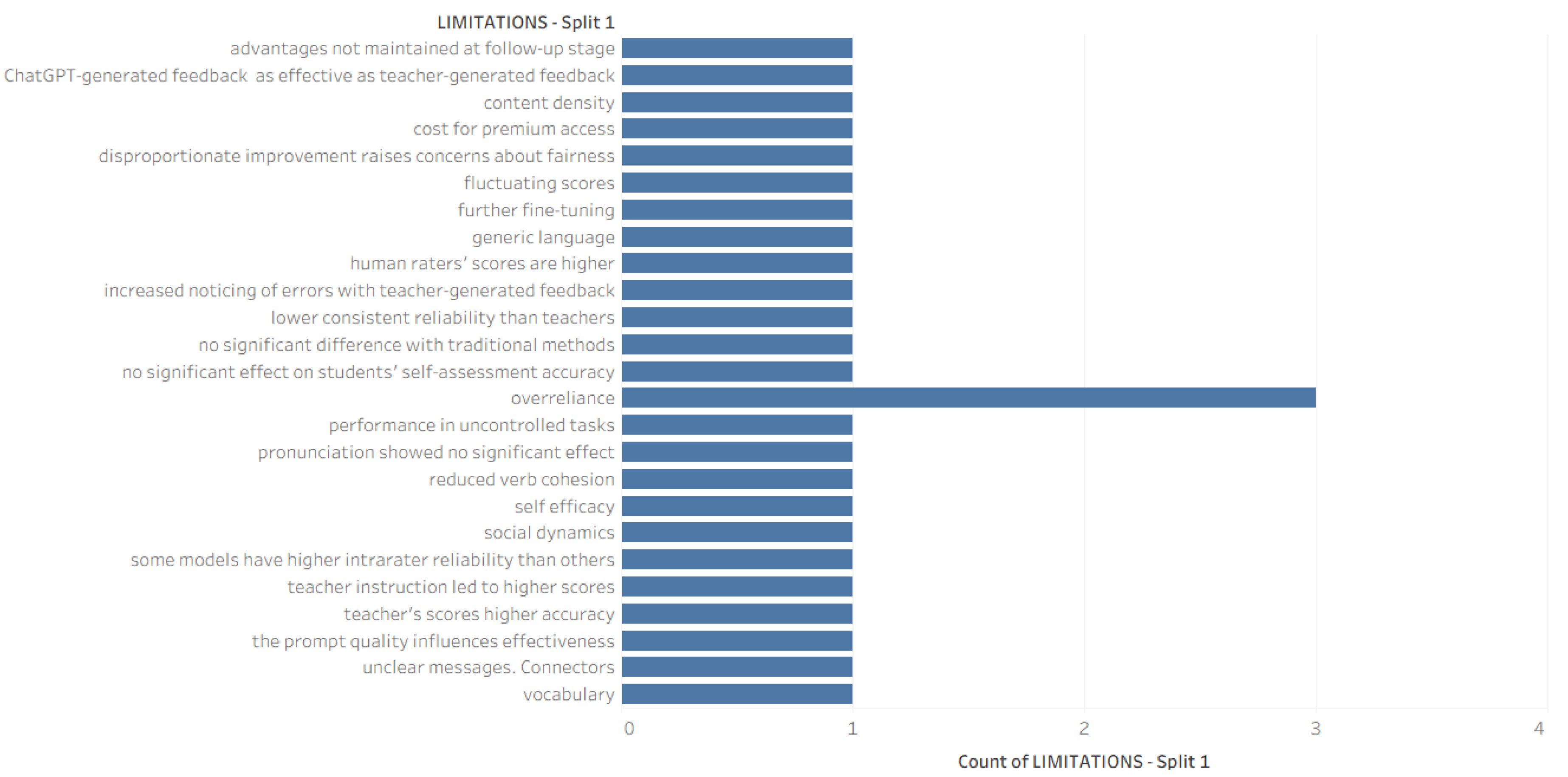

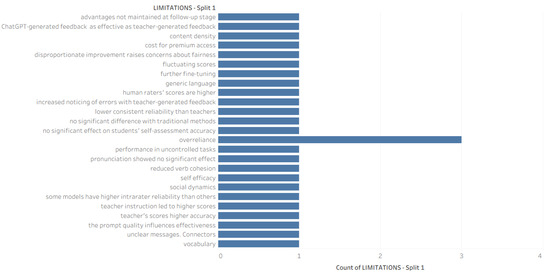

4.3. RQ3: Limitations and Concerns

Table 2 and Figure 8, conversely, give a detailed report of reported limitations or concerns as they were documented by authors. Both tables show that “overreliance” is the term most used when referring to GenAI tools’ limitations. Specifically, researchers and participants in the studies were really concerned about the growing reliance on tools that GenAI technologies entail within the EFL classrooms, and the potential effects on students’ critical thinking and independence in both writing and speaking skills.

Table 2.

Limitations and concerns regarding GenAI use.

Figure 8.

Limitations and concerns of GenAI use.

5. Discussion

5.1. GenAI in EFL Writing

The majority of research investigating the incorporation of GenAI tools in EFL classrooms has been centered around the use of tools in order to enhance the writing skills of students. There are a number of applications and chatbots utilized for this purpose; however, ChatGPT holds a prominent position and seems to be preferred by both students and teachers. The benefits of the use of such systems are reported to be in learners’ autonomy, personalized feedback, increased proficiency levels, and increased levels of motivation. The basic areas that students seem to benefit from GenAI tools are reported by scientists to be grammar, and structure and coherence among sentences and paragraphs. One such example is the study of Alwasidi and Al-Khalifah (2025) [31] who observed significant improvements in students’ writing quality—including content, form, linguistic range, and grammar—when using ChatGPT. Liu et al. (2025) [20,21] have also observed improvements in terms of grammatical fluency in the participants’ text writing. Spelling, along with grammatical improvements, were observed by Abuhussein and Badah (2025) [26] and Mekheimer (2025) [51]. Students in these studies expressed a preference towards the use of ChatGPT and Grammarly for grammar and spelling corrections. Overall, researchers have shown that the greatest improvements in the domains of vocabulary and grammar are documented among lower-proficiency students [68].

In the same vein of language structure improvement, Chen (2025) [37] has observed that students, because of the use of Termsoup (an application that utilizes GenAI technology), have adopted a wider variety of sentences, becoming more aware of the genre requested by the task. In addition, because of the better comprehension of the text register, there was observed a clear tone, with shifts between passive and active voice structures when needed, as well as a wide variety of vocabulary items used in the tourism domain. The results are further supported by the works of Duong and Chen (2025) [40], Rahmi et al. (2024) [57], and Tsai et al. (2024) [68], who showed that chatbots provided clear content and organization of the participants’ writing. Vocabulary and complex sentences have also been boosted by the feedback provided by Writing Assistant Bot (WAB) (another example of GenAI tool) [40], through student engagement and a self-learning environment. ParagraphAI is one more example of a GenAI tool that has been successfully incorporated into EFL classrooms, improving paraphrasing skills and grammatical accuracy, respectively [57].

Critical thinking is another area of writing that can be affected by the implementation of GenAI technology in a language classroom. Idea generation, argumentation, and complex thinking are some of the critical thinking skills that teachers target with their instruction. GenAI tools seem to offer advantages in this area, as chatbots offer new insights into improving students’ arguments and the provision of coherent ideas [43]. At the same time, the participants showed enhanced abilities to personalize the feedback they received by their applications. Yasmin et al. (2025) [71] agree with the beneficial nature of chatbots in improving argumentative writing text production. They have concluded that the chatbot-assisted platforms can support higher order skills, like argument and counterargument generation, in order to foster critical thinking in a writing classroom. Idea generation and argumentation have not only been improved in higher-proficiency students, but also in lower-proficiency ones, proving the generalizability of GenAI tools in these areas [38].

One of the most well-researched domains of the implementation of GenAI technologies in writing instruction is the area of providing feedback. Due to its conversational nature, ChatGPT can offer prompt feedback based on the inserted text or texts. Explicit timely feedback seems to be a preferred method of correction by students, although some of them have expressed the need to receive delayed feedback in order to generate more complex ideas and to better proceed with the given topics. Overall, writing performance can be increased because of GenAI’s timely feedback, as opposed to the traditional feedback that is provided by teachers [67]. GenAI-generated feedback also has the potential to be explicit and direct, especially in terms of grammatical mistakes. As Guo et al. (2024) [43] observed, students prefer to receive explicit feedback targeted to their specific mistakes, rather than receiving teachers’ general comments.

Based on users’ comments, some of the reported advantages of the applications that incorporate GenAI technologies within writing instruction is the friendly environment to users that it hosts, and its user design. Its ease of use and its attractive application environment are elements that increase the motivation of the students. Thus, learners are more likely to use these applications and engage with the feedback they provide. Reportedly, this process can trigger learners’ satisfaction [46]. Increased engagement with GenAI-generated tools, along with the motivation students receive, can also lead to an increased level of autonomy for the learners, as they are able to use these apps in and outside of structured learning environments, with or even without the guidance of their teachers [35]. One of the applications that can facilitate learners’ autonomy is Microsoft Copilot, as, according to the study of Asadi et al. (2025) [34], this application can give users the chance to adapt the learning and practice to their own needs and capacities. The personalized comments and feedback that are provided through these platforms allow students to create and adopt further autonomy and self-regulated habits in EFL learning.

There are a number of benefits that the use of GenAI can provide to students in EFL instruction. However, there is still a question that needs to be answered, which regards the effectiveness of these tools in boosting learners’ skills and providing reliable results. The reliability and validity of the feedback that GenAI tools provide have attracted significant interest. In order to evaluate its reliability, ChatGPT was compared to human raters based on the feedback it provides of written material created by learners. Generally, ChatGPT seems to be in agreement with teachers, but there are some reported discrepancies in some particular areas. These discrepancies are more persistent in argumentative essays, that require more complex and creative structures to be employed [70]. Human raters provide more reliable results based on writings that require deeper analysis, fluency in linguistic structures, and a high level of creativity [30]. On the other hand, Automated Written Corrective Feedback (AWCF) applications can perform similarly to human raters in writings that involve constructive types of essays that are mostly descriptive or analytic. Yavuz et al. (2025) [73] examined the reliability of two applications, ChatGPT and Bard. They inserted specific rubrics in order for these GenAI tools to provide their feedback, and the analysis showed the high reliability of teacher raters, and a slight lenience of ChatGPT towards intermediate level essays.

However, studies on writing skills acquisition have observed some challenges. The prevailing challenge is the ethical consideration of GenAI incorporation. Several researchers have pointed to the fact that the extensive use of GenAI can promote plagiarism among students [34], or even the cultivation of an uncritical mode of learning by passively accepting GenAI’s feedback without actively engaging with it [59]. Ethical awareness and teachers’ guidance are the solutions proposed by scholars [44,59]. Since the era of GenAI is here and is easily accessible by everyone, curriculum creators should balance the potential advantages and concerns by carefully designing and implementing teaching plans. The issue of pragmatic skills within learners’ texts is another issue that has attracted researchers’ attention. Schenck (2024) [61] observed the weakness of Large Language Models, such as ChatGPT, to incorporate cultural discourse features, such as power distance elements within the produced texts. Thus, the researchers highlight the need for educators to critically incorporate GenAI in the teaching of language skills to various cultural backgrounds.

5.2. GenAI in EFL Speaking

The basic problem of traditional speaking classrooms is that they lack opportunities for authentic speaking practice. Thus, learners cannot be exposed to real-life situations where they can practice speaking in a meaningful original EFL context [50,65,78]. GenAI-generated tools can solve this problem and chatbots can provide chances for communication in realistic contexts adapted to the learners’ needs and proficiency level. Such applications are ChatGPT, Elsa and BOPPs. Also, human-like avatars, like EAP Talk 2, Speeko, Talk Pal Bard, Dou Bao, have shown capacities to positively increase learners’ speaking proficiency levels as well as their willingness to communicate [20,21,63].

In terms of speaking, elements that can be improved because of interaction with GenAI agents are mainly pronunciation, vocabulary, and fluency. Especially, fluency gains tend to be important to intermediate level learners, but learners at all levels can show improvement through this interaction [66]. Intonation, stress patterns, and pragmatic aspects of the language can also be enhanced because of GenAI integration in an EFL environment [64].

One of the problems that learners face in communicating their ideas to others in EFL is the stress and anxiety that they will not be understood or will not be able to express the proper meanings they have in mind. GenAI tools offer improvements in this area, as they do not judge, and do not make inappropriate comments or uncomfortable pauses. The use of GenAI agents can reduce deterrents like anxiety, unwillingness, or a sense of failure [20,35,46,49,78]. The feedback of GenAI agents is timely, personalized, and targeted to the specific mistakes made during conversation, enhancing precision in expression. Learners can use these applications without time or place limitations, and with or without a teacher’s supervision, further enhancing their autonomy and self-regulation strategies.

All of these benefits can become a reality through teachers’ incorporation of these tools in their classes. Teachers’ instruction and the implementation of appropriate strategies can ensure that these apps are utilized appropriately and to the maximum benefit of the learners, tailored to their levels and needs. Teachers’ contribution is an essential aspect in cases where learners’ proficiency levels are low, and their pronunciation is unrecognizable by the GenAI agents. In this case, GenAI can cause stress to the users, confusing them and leading to increasing affective filters like anxiety and decreased motivation. Another instance in which the human contribution proves helpful concerns the regulation of the context in which practice takes place, based on the proficiency level of the class. Teachers can balance the irregularities that may occur, and can secure a constructivist-based environment where speaking acquisition will take place.

5.3. Concerns and Limitations

A number of studies have identified some warnings against the extensive use of GenAI technologies. These concerns can be categorized broadly into technical, pedagogical, ethical, and accessibility-related categories. Firstly, there are concerns about technical limitations, which primarily refer to the reliability and accuracy of the feedback provided. Overall, Automated Writing Feedback Systems (AWFS), when compared to human teachers, struggle in writings that require deeper levels of argumentation and synthesis as compared to descriptive ones. That is why Shabara et al. (2024) [62] highlight the importance of constantly improving GenAI algorithms and hybrid assessment methods. Since GenAI-generated feedback is not as effective as teachers in certain aspects of writing, there is a constant need for the explanation of the comments provided by these machines, which need to be supported by specific comments and guidelines. Linguistic areas where GenAI tools struggle the most include persistent errors of verb tenses, preposition use, pronoun mistakes, and other grammatical structures [48]. Kim and Chon (2025) [48] agree on the fact that ChatGPT and relative GenAI applications can lead to partially reliable feedback because they struggle with repetitive language and the coherence of the discourse. Pedagogical concerns relate to overreliance on GenAI tools, which can impede learners’ creative thinking and independent writing skills [26,31]. Students usually show preference for these applications because of the easily available and coherent content they provide, since both teachers and students are not well-informed of how and when to use these tools effectively. Despite students’ favoring of chatbots due to their fluency and the coherency of their generated output, their utilization can foster passive behavior patterns in EFL classrooms or learning in general.

Ethical issues are also present. GenAI output has been widely judged because it provides feedback embedded with cultural and other biases, making human contribution more necessary than ever in navigating through these results [48]. In addition, most of the time, students are not aware that they are required to cite the use of GenAI assistance, and so have a tendency to plagiarize [34]. Another reported problem of students’ close interaction with GenAI systems is the confusion that can be created regarding how to use the feedback they receive. This confusion, with the students being unaware of GenAI potential, can lead to limited effectiveness and overload in terms of cognition. Finally, accessibility barriers can impede learning performance. According to this, another issue that a prospect educator can encounter is that not all students are privileged enough to have access to these technologies. This can happen due to limited financial resources, cultural restraints, or even geographical constraints [26,60]. This inequality in terms of accessibility can widen existing educational differences.

In summary, although learners themselves are optimistic about GenAI tools, they seem quite skeptical when they are asked about their confidence in using them. This is because, despite their popularity, they are not utilized properly in higher education in certain countries because of the ethical concerns that have been raised and the total ignorance of official and institutional guidelines regarding how to use them. These concerns might be culture-specific as they do not seem to be adopted on a global level.

5.4. Pedagogical Implications

The majority of research points out the necessity of the adoption of a “GenAI+teacher” model in EFL classrooms. Communicative competence, which is the priority in communicative learning theories, can be enriched by GenAI-induced practice, where learners engage in dialogic practice with chatbots and at the same time rely on teachers’ mediation. While recognizing the benefits and improvements GenAI-induced tools can offer to foreign language learners, researchers undoubtedly agree on the irreplaceable role of a human contribution in those environments. Although GenAI agents are effective in providing immediate and precise feedback, this feedback is focused on surface-level mistakes, like grammar, vocabulary, and pronunciation [26,28,39]. Furthermore, they have been proven ineffective in generating deeper understanding regarding the nature of students’ needs [54]. Another area in which GenAI-generated tools fail to assist learners is in their critical thinking skills. Even though GenAI chatbots can provide idea generation and can propose more complex thinking, they fail to cultivate deeper thinking skills, such as interpretation, synthesis, or even rhetorical structure [48].

From this standpoint, human teachers can take on the responsibility of preparing the learners to adopt strategies that will provide them with the maximum benefits of technology without limiting the cultivation of their critical skills. Preparing students to enter a digital and technology-prone world is among the life skills that learners are supposed to acquire. Continuous preparation and the inclusion of technological means enhance learners’ autonomy and self-directed learning, preparing students for their life outside classrooms. This is particularly true in EFL teaching, in which proficiency achievement is an ongoing process that should continue even after instruction is completed. In this way, students will be guided on how to choose the appropriate materials and tools to interact effectively, taking the chance to communicate in the target language.

The overall gains of GenAI tools that are reported within writing classes seem to be short-term. Pedagogical contributions and human guidance can transform the short-term benefits into long-term and long-lasting gains [76]. Researchers reach the consensus that technology can complement the learning process and not replace it. Teachers can make use of GenAI tools’ timely and immediate feedback to ease their workload by carefully planning how to respond to individual learners’ needs and higher-rated skills. In particular, the educator’s role can be modified to suit new learners’ needs in the new GenAI era. Such roles may include guiding learners on how to interpret automated written feedback provided by chatbots, making the greatest advantage out of their use. Additionally, ChatGPT can be integrated into various writing levels, showing students the correct input, in order to receive accurate contexts that distinctively respond to every level of the writing process. Finally, teachers themselves can guide students to avoid plagiarism, through projecting the acceptable use terms of every GenAI tool and acknowledging this use in the reference sections of their work.

In order for this to be a reality, teachers themselves need detailed information and training in this domain. Teachers should learn how to carefully utilize GenAI-induced applications by taking advantage of their improved characteristics, and at the same time securing the benefits for the students without jeopardizing their critical reflection. Institutions, on the other hand, should provide detailed and careful guidelines of how GenAI tools will be incorporated into this process, by securing against instances of plagiarism, misuse, or even biases inherent in GenAI output [34,48]. Institutions should provide structured training for teachers on how to effectively, and in an ethical way, use GenAI technologies with their students, particularly to ensure responsible adoption, equal access for every learner, and data protection.

5.5. Limitations and Future Research

Despite the contributions of this study to the overall body of literature in the relevant field of study, there are some limitations that should be acknowledged to future scientists. Firstly, this study focused solely on the productive skills of speaking and writing, which is a fragmentation of the four basic skills that are cultivated in the EFL classroom. Following this, only two databases, Web of Science and Scopus, were researched. Another limitation of the present study refers to the fact that not only were GenAI tools utilized, but also AI tools with GenAI elements. Next, all the qualitative studies or the studies based on students’ perceptions and viewpoints were eliminated from the final dataset. Lastly, the time constraint of 2024–2025 was strict, excluding trustworthy studies that may have taken place earlier.

In order to address these limitations, scientists with interest in the relevant area of study might consider conducting an analysis of all four basic skills, both productive and receptive ones. Moreover, more trustworthy databases could be utilized to provide more concrete research on the relevant topic. Furthermore, qualitative studies and studies exploiting students’ ideas and proposals would give a more precise picture of the topic examined. Finally, the time span could be extended to lead to more reliable conclusions.

6. Conclusions

To conclude, GenAI tools and chatbots seem to offer a number of advantages to educators around the world in their instruction of the productive skills of writing and speaking to non-native speakers of English. Users of such platforms show increased motivation and preference for these tools, which interact with and provide feedback on their work. They regard the GenAI-generated feedback to be non-judgmental and less frustrating than teachers’ or peers’ feedback. Overall, there is a tendency for automated feedback to be more precise in terms of surface linguistic elements like spelling, grammar, and vocabulary. However, there is growing interest in how GenAI chatbots can facilitate complex ideas, critical thinking analysis, or provide insights into shaping independent learning styles. This is an area in which there is a heated debate regarding whether ChatGPT and similar GenAI tools can cultivate critical thinking or argumentative ideas to learners of English as a second/foreign language. The basic limitation that is expressed in the majority of research within the present study is the overreliance issue. Researchers and educators, as well as students themselves, are concerned about what effects the total dependence on GenAI tools can have. Among other issues that are discussed in the present paper, data privacy and restricted access to premium features, as well as inaccuracies, hold prominent positions in the research of the relevant field. In order to balance the benefits and limitations of GenAI tools, we propose the model of GenAI plus teacher. Through careful implementation of new policies and through raising awareness of the issues that need a careful approach, educators and institutional councils will be able to secure a beneficial learning environment for learners, in which they will utilize GenAI by taking the necessary precautions to prevent its overuse.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.A. and P.C.; methodology, P.C.; software, P.C.; validation, G.A., P.C.; formal analysis, P.C.; investigation, P.C.; resources, P.C.; data curation, P.C.; writing—original draft preparation, P.C.; writing—review and editing, G.A., P.C.; visualization, P.C.; supervision, G.A.; project administration, G.A.; funding acquisition, G.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this review. This systematic review has been registered under PROSPERO (ID: 1126543).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript

| GenAI | Generative Artificial Intelligence |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| EFL | English as a second/foreign language |

| AR | Augmented Reality |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| L2 | Second language |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| PLL | Personalized Language Learning |

References

- Hsu, M.; Chen, P.; Yu, C. Proposing a task-oriented chatbot system for EFL learners speaking practice. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2021, 31, 4297–4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Gao, H. Determinants affecting teachers’ adoption of AI-based applications in EFL context: An analysis of analytic hierarchy process. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 9357–9384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bygate, M. Speaking; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Swain, M. Communicative competence: Some roles of comprehensible input and comprehensible output in its development. In Input in Second Language Acquisition; Gass, S., Madden, C., Eds.; Newbury House: Rowley, MA, USA, 1985; pp. 235–253. [Google Scholar]

- Canale, M.; Swain, M. Theoretical Bases of Communicative Approaches to Second Language Teaching and Testing. Appl. Linguist. 1980, 1, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, M. Three functions of output in second language learning. In Principle and Practice in Applied Linguistics: Studies in Honour; Widdowson, H.G., Cook, G., Seidlhofer, B., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995; pp. 125–144. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, M.; Long, S.; Martin, F.; Castellanos-Reyes, D. The affordances of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and ethical considerations across the instruction cycle: A systematic review of AI in online higher education. Internet High. Educ. 2025, 67, 101039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 6.3; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022. Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Scoping Reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: St. Miami, FL, USA, 2020; Chapter 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divekar, R.; Drozdal, J.; Chabot, S.; Zhou, Y. Foreign language acquisition via Artificial Intelligence and Extended Reality: Design and evaluation. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2021, 35, 2332–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, X. The impact of chatbots based on large language models on second language vocabulary acquisition. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.C.; Wong, B.T.M. How learning has been personalized: A review of literature from 2009 to 2018. In Blended Learning: Educational Innovation for Personalized Learning, Proceedings of the ICBL 2019, Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic, 2–4 July 2019; Cheung, S., Lee, L.K., Simonova, I., Kozel, T., Kwok, L.F., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 11546, pp. 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastura, T. Assessing learners’ communicative competence in different testing system. Online J. Sustain. Leadersh. Res. 2021, 1, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timpe-Laughlin, V.; Sydorenko, T.; Daurio, P. Using spoken dialogue technology for L2 speaking practice: What do teachers think? Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2020, 35, 1194–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R. Interactional competence in learning, teaching, and testing. In Handbook of Research in Second Language Teaching and Learning; Routledge, E.H., Ed.; Taylor Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2011; pp. 426–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reem, A. Chatting with AI Bot: Vocabulary Learning Assistant for Saudi EFL Learners. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2021, 14, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.H. The role of the linguistic environment in second language acquisition. In Handbook of Second Language Acquisition; Ritchie, W.C., Bhatia, T.K., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 413–468. [Google Scholar]

- Karataş, F.; Gunyel, F.; Abedi, F.; Karadeniz, D. Incorporating AI in foreign language education: An investigation into ChatGPT’s effect on foreign language learners. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 3, 3195–3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koraishi, O. Teaching English in the age of AI: Embracing ChatGPT to optimize EFL materials and assessment. LET Linguist. Lit. Engl. Teach. J. 2023, 3, 55–72. Available online: https://langedutech.com/letjournal/index.php/let/article/view/48 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Liu, J.; Hamid, H.A.; Bao, X. Motivation and achievement in EFL: The power of instructional approach. Front. Educ. 2025, 10, 1614388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.J.; Wang, J.; Zou, B. Evaluating an AI speaking assessment tool: Score accuracy, perceived validity, and oral peer feedback as feedback enhancement. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 2025, 75, 101505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.K.; Yu, P.L.H.; Xu, S.; Ng, D.T.K.; Jong, M.S.Y. Exploring the application of ChatGPT in ESL/EFL education and related research issues: A systematic review of empirical studies. Smart Learn. Environ. 2024, 11, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang Mai Tram, N.; Trung Nguyen, T.; Duc Tran, C. ChatGPT as a tool for self-learning English among EFL learners: A multi-methods study. System 2024, 127, 103528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Li, S. Opportunities and challenges in the application of ChatGpt in foreign language teaching. Int. J. Educ. Soc. Sci. Res. 2023, 6, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuhussein, H.F.; Badah, A. The Role of AI-based Writing Tools on L2 Writing Competency: Evidence from Palestinian EFL Learners. Dirasat Hum. Soc. Sci. 2025, 52, 6566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afandi, I. Assessing text comprehension proficiency: Indonesian higher education students vs. ChatGPT. XLinguae 2024, 17, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Husban, N.A. The impact of AI-assisted language learning tools on augmenting university EFL students’ speaking skills in Jordan. J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 2025, 8, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaweed, W.; Aljebreen, S. Investigating the Accuracy of ChatGPT as a Writing Error Correction Tool. Int. J. Comput.-Assist. Lang. Learn. Teach. 2024, 14, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsofyani, A.H.; Barzanji, A.M. The Effects of ChatGPT-Generated Feedback on Saudi EFL Learners’ Writing Skills and Perception at the Tertiary Level: A Mixed-Methods Study. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2025, 63, 431–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwasidi, M.A.; Al-Khalifah, K.S. Assessing the Impact of ChatGPT on EFL Students’ Writing Productivity and Proficiency. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 2025, 16, 986–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, M.; Ebadi, S.; Mohammadi, L. The impact of integrating ChatGPT with teachers’ feedback on EFL writing skills. Think. Ski. Creat. 2025, 56, 101766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, M.; Ebadi, S.; Salman, A.R.; Taheri, R.; Mohammadi, L. Investigating the effects of AI-assisted teacher instruction on online IELTS writing. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2025, 12, 101747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodaubekov, A.; Agaidarova, S.; Zhussipbek, T.; Gaipov, D.; Balta, N. Leveraging AI to enhance writing skills of senior TFL students in Kazakhstan: A case study using “Write Improve”. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 2025, 17, 15687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Jia, J.; Li, Y.; Fu, L. Investigating the Effect of Role-Play Activity With GenAI Agent on EFL Students’ Speaking Performance. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2025, 63, 99–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Gong, Y. The Role of AI-Assisted Learning in Academic Writing: A Mixed-Methods Study on Chinese as a Second Language Students. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-Y.R. Enhancing ESP Writing Skills Through the Use of Termsoup: An Exploratory Study. Technol. Lang. Teach. Learn. 2025, 7, 102355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmawansah, D.; Rachman, D.; Febiyani, F.; Hwang, G.-J. ChatGPT-supported collaborative argumentation: Integrating collaboration script and argument mapping to enhance EFL students’ argumentation skills. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30, 3803–3827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, T.; Suppasetseree, S. The Effects of an Artificial Intelligence Voice Chatbot on Improving Vietnamese Undergraduate Students’ English Speaking Skills. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2024, 23, 293–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, T.-N.-A.; Chen, H.-L. An AI Chatbot for EFL Writing: Students’ Usage Tendencies, Writing Performance, and Perceptions. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2025, 63, 406–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElEbyary, K.; Shabara, R.; Boraie, D. The differential role of AI-operated WCF in L2 students’ noticing of errors and its impact on writing scores. Lang. Test. Asia 2024, 14, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Hashim, H.; Md Yunus, M. Assessing the reliability and relevance of DeepSeek in EFL writing evaluation: A generalizability theory approach. Lang. Test. Asia 2025, 15, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Pan, M.; Li, Y.; Lai, C. Effects of an AI-supported approach to peer feedback on university EFL students’ feedback quality and writing ability. Internet High. Educ. 2024, 63, 100962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J. Exploring ChatGPT-supported teacher feedback in the EFL context. System 2024, 126, 103502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jmaiel, H.A.; Abukhait, R.O.; Mohamed, A.M.; Shaaban, T.S.; Al-khresheh, M.H.; AL-Qadri, A.H. The role of ChatGPT in enhancing EFL students’ ESP writing skills: An experimental study of gender and major differences. Discov. Educ. 2025, 4, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanoksilapatham, B.; Takrudkaew, T. Integrating ChatGPT to Enhance University Students‘Communication Skills: Pedagogical Considerations. World J. Engl. Lang. 2025, 15, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemelbekova, Z.; Degtyareva, X.; Yessenaman, S.; Ismailova, D.; Seidaliyeva, G. AI in teaching English as a foreign language: Effectiveness and prospects in Kazakh higher education. XLinguae 2024, 17, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Chon, Y.V. The impact of self-revision, machine translation, and ChatGPT on L2 writing: Raters’ assessments, linguistic complexity, and error correction. Assess. Writ. 2025, 65, 100950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Z.C.-C. Enhancing EFL Oral Proficiency Through a ChatGPT-Integrated BOPPPS Learning Framework. Int. J. Online Pedagog. Course Des. 2025, 15, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebenow, L.W.; Schmidt, F.T.C.; Meyer, J.; Fleckenstein, J. Self-assessment accuracy in the age of artificial Intelligence: Differential effects of LLM-generated feedback. Comput. Educ. 2025, 237, 105385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekheimer, M. Generative AI-assisted feedback and EFL writing: A study on proficiency, revision frequency and writing quality. Discov. Educ. 2025, 4, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingyan, M.; Noordin, N.; Razali, A.B. Improving EFL speaking performance among undergraduate students with an AI-powered mobile app in after-class assignments: An empirical investigation. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzoyeva, L.; Makhanova, Z.; Ibrahim, M.K.; Snezhko, Z. Formation of auditory and speech competences in learning English based on neural network technologies: Psycholinguistic aspect. Cogent Educ. 2024, 11, 2404264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdere, M. AI in Academic Writing: Assessing the Effectiveness, Grading Consistency, and Student Perspectives of ChatGPT and You.com for EFL Students. Int. J. Technol. Educ. 2025, 8, 123–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pack, A.; Barrett, A.; Escalante, J. Large language models and automated essay scoring of English language learner writing: Insights into validity and reliability. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2024, 6, 100234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polakova, P.; Ivenz, P. The impact of ChatGPT feedback on the development of EFL students’ writing skills. Cogent Educ. 2024, 11, 2410101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmi, R.; Amalina, Z.; Rodgers, A. Does It Really Help? Exploring the Impact of Al-Generated Writing Assistant on the Students’ English Writing. Stud. Engl. Lang. Educ. 2024, 11, 998–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawangwan, S. ChatGPT vs. Teacher Roles in Developing EFL Writing. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. Teach. 2024, 14, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, B.T.; Bani Younes, Z.B.; Alkhayyat, A.; Adhamova, I.; Teferi, H. To be with artificial intelligence in oral test or not to be: A probe into the traces of success in speaking skill, psychological well-being, autonomy, and academic buoyancy. Lang. Test. Asia 2024, 14, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenck, A. ChatGPT Is Powerful, but Does It Have Power Distance? Int. J. Adult Educ. Technol. 2024, 15, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaalan, I.E.-N.A.W. The Impact of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning on Linguistic Accuracy, Fluency, and Self-Direction Among Advanced EFL Students. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 2025, 15, 1987–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabara, R.; ElEbyary, K.; Boraie, D. TEACHERS or CHATGPT: The ISSUE of ACCURACY and CONSISTENCY in L2 ASSESSMENT. Teach. Engl. Technol. 2024, 24, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiee Rad, H. Revolutionizing L2 speaking proficiency, willingness to communicate, and perceptions through artificial intelligence: A case of Speeko application. Innov. Lang. Learn. Teach. 2024, 18, 364–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikun, S.; Grigoryan, G.; Ning, H.; Harutyunyan, H. AI Chatbots: Developing English Language Proficiency in EFL Classroom. Arab. World Engl. J. 2024, 1, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, T.-Y. Exploring the effects of intelligent personal assistants on bilingual education teachers’ L2 speaking proficiency. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2025, 33, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, T.-Y.; Chen, H.H.-J. Navigating elementary EFL speaking skills with generative AI chatbots: Exploring individual and paired interactions. Comput. Educ. 2024, 220, 105112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.T.T. Enhancing EFL Writing Revision Practices: The Impact of AI- and Teacher-Generated Feedback and Their Sequences. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-Y.; Lin, Y.-T.; Brown, I.K. Impacts of ChatGPT-assisted writing for EFL English majors: Feasibility and challenges. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 22427–22445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, S.; Negishi, M. Assigning CEFR-J levels to English learners’ writing: An approach using lexical metrics and generative AI. Res. Methods Appl. Linguist. 2025, 4, 100199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyar, A.; Büyükahıska, D. Artificial intelligence as an automated essay scoring tool: A focus on ChatGPT. Int. J. Assess. Tools Educ. 2025, 12, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasmin, M.; Fatima, W.; Irshad, I. Evaluating ChatGPT’s effectiveness in enhancing argumentative writing: A quasi-experimental study of EFL learners in Pakistan. Sustain. Futures 2025, 10, 100809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, F.; Çelik, Ö.; Yavaş Çelik, G. Utilizing large language models for EFL essay grading: An examination of reliability and validity in rubric-based assessments. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2025, 56, 150–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, C. ChatGPT Integration in EFL Education: A Path to Enhanced Speaking Self-Efficacy. Novitas-ROYAL 2024, 18, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zou, D.; Cheng, G.; Xie, H. Flow in ChatGPT-based logic learning and its influences on logic and self-efficacy in English argumentative writing. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2025, 162, 108457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D. The impact of AI-enhanced natural language processing tools on writing proficiency: An analysis of language precision, content summarization, and creative writing facilitation. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30, 8055–8086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheldibayeva, R. GenAI as a Learning Buddy for Non-English Majors: Effects on Listening and Writing Performance. Educ. Process Int. J. 2025, 14, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Hashim, H.; Sulaiman, N.A. Supporting english speaking practice in higher education: The impact of AI chatbot-integrated mobile-assisted blended learning framework. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30, 14629–14660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Z.C.-C. The Impact of AI-Assisted Blended Learning on Writing Efficacy and Resilience. Int. J. Comput.-Assist. Lang. Learn. Teach. 2025, 15, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).