1. Introduction

In rotating machinery, rolling bearings serve as essential elements for structural support and power transfer, with their operational state fundamentally determining the system’s comprehensive performance, accuracy, and operational lifespan [

1]. Therefore, accurate bearing condition monitoring and fault diagnosis are indispensable for assuring the reliability of critical assets and supporting predictive maintenance strategies [

2]. Although traditional vibration-centered techniques have achieved broad and successful implementation [

3], the progression of contemporary equipment toward increased dimensions, greater complexity, and especially extreme rotational velocities creates significant obstacles for these proven approaches [

4].

At extreme operating speeds, often beyond several tens of thousands of RPM, factors such as ultrasonic fault impacts, dynamics altered by strong centrifugal forces, and pronounced time variations jointly create resolution and SNR bottlenecks for conventional signal processing [

5,

6]. This combination of elements produces four primary obstacles: (1) separating adjacent bearing harmonic components necessitates exceptional frequency discrimination, while preserving stationarity requires millisecond-scale analysis windows—creating an inherent contradiction for transformation-based approaches [

7,

8]; (2) achieving real-time execution on embedded platforms restricts permissible computational complexity to logarithmic-linear processes within strict timing constraints [

7]; (3) field measurements commonly display extremely poor signal-to-noise characteristics, where electromagnetic disturbances coincide with important defect frequencies [

9]; (4) rotational speed fluctuations spanning multiple percentage points arise within single analysis windows during operational transitions, resulting in fault frequencies migrating through numerous spectral bins [

10,

11,

12].

Classical frequency-domain techniques remain standard in industry, with FFT-based analysis prized for its computational efficiency [

13,

14]. Yet, resolution limitations drastically restrict their utility—small velocity fluctuations at elevated RPM lead to frequency spreading over numerous spectral regions, making substantial portions of bearing harmonic content indistinguishable [

15,

16,

17]. Envelope analysis partially addresses this through high-frequency demodulation, yet assumes quasi-stationarity that fails at extreme acceleration rates [

13,

18,

19]. WPD offers adjustable resolution yet fails to attain adequate frequency discrimination at ultrasonic ranges needed for separating adjacent bearing harmonic components [

15]. Recent works have used wavelet transforms to extract diagnostic signatures for bearing faults, highlighting their adaptability in time-frequency localization but also the sensitivity to basis and level selection [

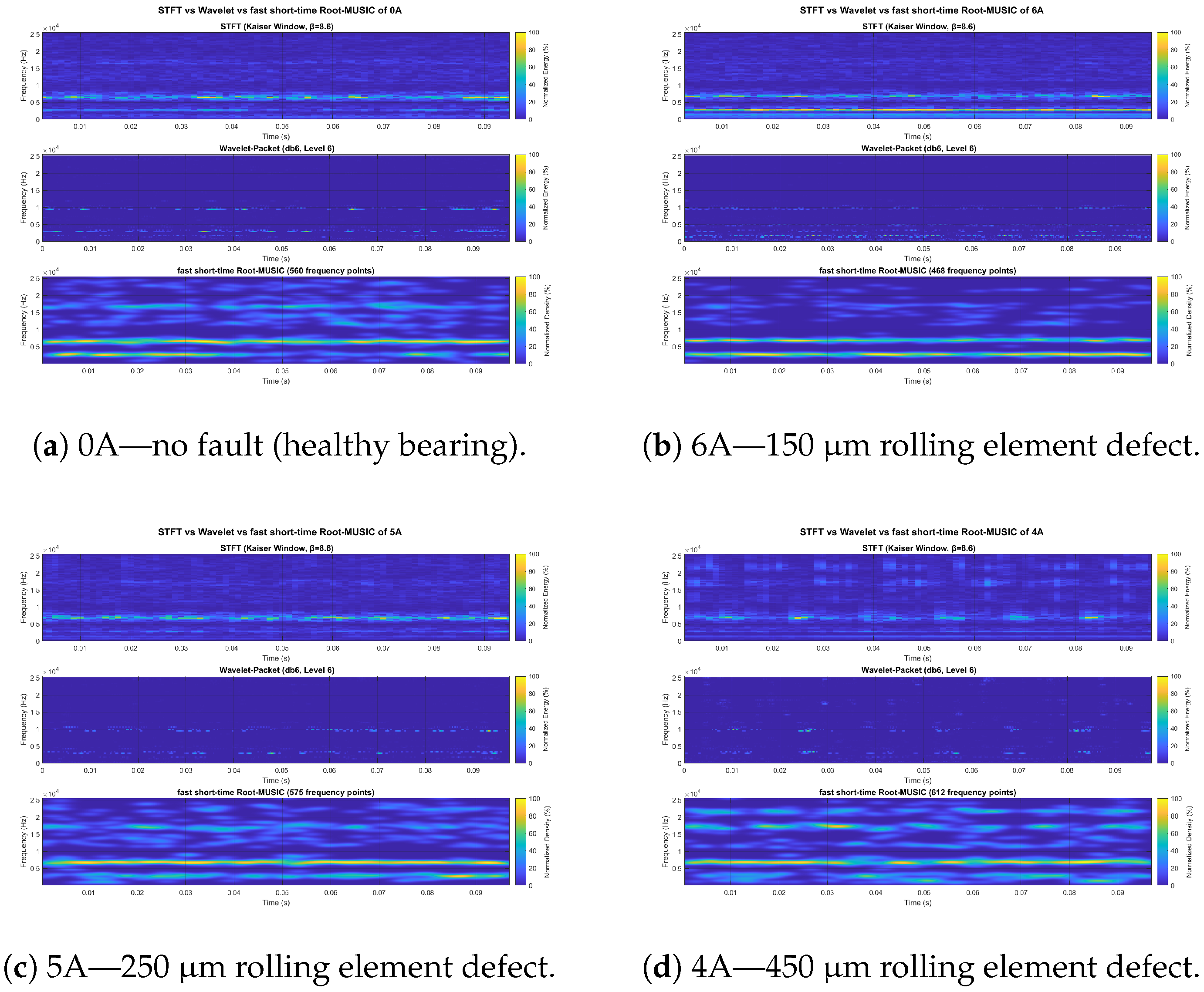

20]. STFT delivers limited detection precision at extreme velocities, because many defect signatures are masked by time-frequency trade-offs and fixed-window compromises. Advanced representations such as the Wigner–Ville distribution can offer higher resolution, but they introduce significant cross-term interference in multi-component bearing signals, limiting practical utility in noisy industrial conditions [

18,

19].

Self-adjusting decomposition techniques pursue data-centered analysis independent of predetermined basis functions. EMD inherently isolates defect patterns yet experiences severe mode contamination at ultrasonic ranges, demonstrating elevated failure occurrences. VMD introduces mathematical precision via optimization constraints, attaining reasonable resolution, though demanding computational periods unsuitable for real-time operation and requiring manual parameter configuration that substantially compromises effectiveness when misspecified. Parametric and subspace approaches constitute the theoretical pinnacle for frequency determination. MUSIC and Root-MUSIC attain super-resolution through leveraging signal subspace characteristics, isolating numerous fault frequencies with extraordinary precision despite extremely poor SNR—delivering tenfold enhancement over FFT techniques. However, the cubic cost of eigenvalue decompositions confines practical use to offline analysis, imposing prohibitive processing time on embedded hardware. Prior acceleration strategies either trade off resolution (propagator method [

21]), target only limited frequency sectors (beamspace MUSIC [

22,

23]), or encounter numerical instability and subspace-tracking issues [

23].

Machine learning methodologies demonstrate superior performance on benchmark collections yet generalization persists as challenging—precision deteriorates substantially when networks confront velocities marginally divergent from training conditions, exhibiting inflated false positive occurrences on alternative equipment configurations [

24]. Recent paradigm shifts in data-driven diagnostics have sparked considerable scholarly attention. Multi-resolution broad learning architectures [

25], for instance, elegantly tackle incomplete modal data through hierarchical feature extraction—yet their reliance on quasi-static training distributions renders them fragile when confronted with the hyper-dynamic bearing regimes characteristic of aerospace spindles. Wavelet-denoising-infused machine learning pipelines [

26] exhibit commendable noise resilience, though at the cost of computational overhead incompatible with millisecond-scale inference budgets. More promisingly, physics-informed hybrid frameworks [

27] marry empirical learning with mechanistic constraints, achieving enhanced cross-equipment transferability—nonetheless, their iterative optimization loops (often exceeding 100 ms per update cycle) preclude real-time deployment on resource-constrained edge nodes. The crux remains: while ML excels at pattern recognition within well-populated training manifolds, it falters when extrapolating to the sparse, high-dimensional fault spaces endemic to incipient micro-defects operating under transient conditions. Physics-guided frameworks enhance generalization considerably, yet computational demands surpassing standard real-time boundaries impede implementation [

24]. Moreover, fast SVD variants using sliding-window schemes have been explored, including Sliding Window Adaptive SVD (SWASVD) with sequential QR updates. As shown by Badeau et al. [

28], such methods effectively preserve subspace-tracking performance while lowering computational complexity. However, for online diagnosis of bearing micro-defects, these general-purpose algorithms remain constrained by the initial SVD cost, underscoring the need for additional optimization. Key gaps persist: although SWASVD delivers effective subspace tracking, no current technique concurrently realizes super-resolution, logarithmic-linear complexity, resilient operation under industrial noise conditions, and autonomous adaptation tailored for bearing fault identification. The presented fDSTrM algorithm resolves this challenge through extending the SWASVD foundation [

28] while incorporating FFT-accelerated Hankel matrix-vector computations and Lanczos bidiagonalization refinement.

Table 1 delineates the fundamental performance deficiency: no current approach concurrently attains super-resolution capability, logarithmic-linear complexity, and resilient operation under industrial noise conditions.

In this study, the following notations are used: denotes the sampling frequency, N the total number of samples, the window length, P the number of windows, and the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) factor. It should be noted that (a) the frequency resolution in wavelet-based methods varies with both the wavelet scale and the choice of mother wavelet, and is typically expressed as , where Q is the quality factor; (b) in empirical mode decomposition, the resolution is determined by the intrinsic mode functions, without a fixed analytical expression; (c) subspace-based approaches may achieve super-resolution, although the effective resolution is subject to the signal subspace dimension and the SNR.

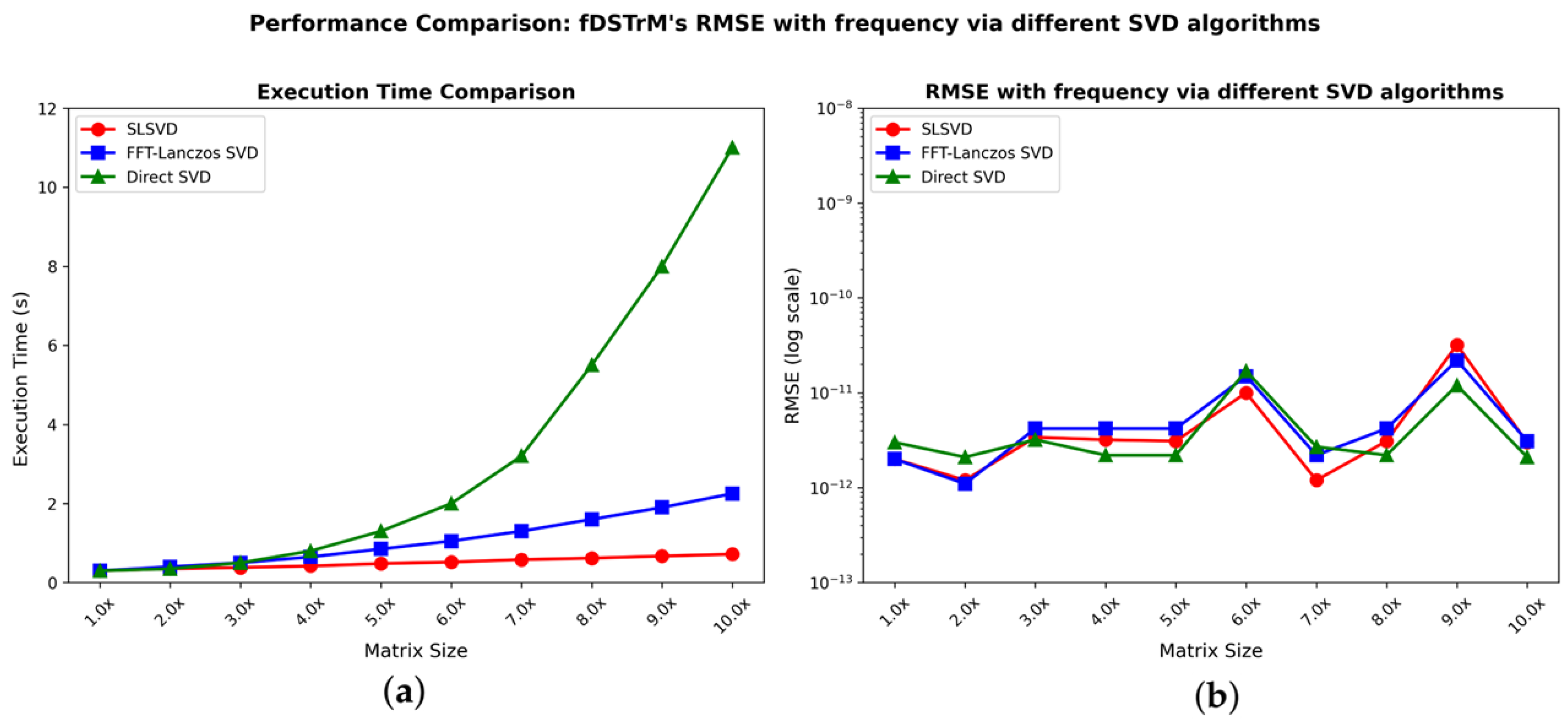

While the general SWASVD algorithm demonstrates excellent performance for generic signals, direct application to high-speed bearing monitoring faces unique challenges: detecting extremely weak fault signatures at ultrasonic frequencies, handling rapid transients during speed variations, and guaranteeing real-time performance on embedded systems. This paper transforms the general SWASVD framework into a specialized bearing diagnostic tool through domain-specific adaptations. By extending the SWASVD foundation [

28], this research presents fDSTrM incorporating three principal advances beyond the universal algorithm: (1) a composite two-stage framework that ideally equilibrates initialization and tracking tailored for bearing vibrations; (2) an FFT-driven model dimension pre-determination that diminishes redundant iterations by 60% within bearing defect scenarios; (3) the utilization of bearing-characteristic signal attributes encompassing quasi-periodic patterns and harmonic correlations.

Experimental verification using spindles functioning at tens of thousands of RPM reveals considerable enhancement in frequency discrimination relative to STFT and facilitates practical implementation of parametric spectral evaluation in manufacturing settings for the initial instance. The subsequent sections are structured accordingly:

Section 2 introduces the mathematical foundation and experimental verification of the fDSTrM algorithm.

Section 3 provides findings and analysis.

Section 4, the conclusion, emphasizes examining the influence on industrial implementation and prospective research trajectories.

Research Hypothesis and Scientific Contributions

The fundamental premise undergirding this investigation posits that the computational intractability plaguing classical Root-MUSIC—stemming from its eigendecomposition bottleneck—constitutes not an immutable algorithmic constraint but rather an artifact of suboptimal exploitation of domain-specific signal structure. This work advances three interlocking hypotheses whose collective validation would fundamentally challenge prevailing assumptions about subspace methods’ unsuitability for real-time embedded deployment.

Hypothesis 1. Computational Complexity Reduction Through Structure Exploitation.

We hypothesize that leveraging the inherent Hankel structure of bearing vibration covariance matrices through FFT-accelerated Lanczos bidiagonalization can reduce per-frame computational complexity from

to

while preserving numerical fidelity within

relative error bounds. This conjecture directly confronts the widespread belief that super-resolution techniques remain inherently unsuitable for millisecond-scale processing deadlines. If validated, the observed

speedup would constitute not merely an implementation optimization but a fundamental algorithmic breakthrough exploiting circular convolution properties of Toeplitz-adjacent matrices [

29].

Hypothesis 2. Super-Resolution Preservation Across Industrial Noise Regimes.

The proposed Dual-Phase architecture—comprising FFT-Lanczos initialization coupled with Sliding-window Singular Value Decomposition (SLSVD) tracking—is hypothesized to sustain frequency resolution below 1 Hz across SNR regimes spanning −5 to +15 dB, achieving detection probabilities exceeding 95% for 150 μm micro-defects under conditions where conventional time-frequency methods exhibit complete diagnostic failure. Critical to this hypothesis stands the FFT-based order pre-estimation mechanism detailed in

Section 2.1.2, whose adaptive correction factor

must reliably segregate signal and noise subspaces even when eigenvalue spectra exhibit poor separation with ratios

. Refutation would manifest through systematic detection-rate collapse below 80% for SNR beneath 0 dB. The controlled robustness experiments presented in

Section 3.1.3 explicitly target these failure boundaries through parametric variation of additive noise, impulsive disturbances, and drive harmonic amplitudes.

Hypothesis 3. Deterministic Real-Time Execution on Resource-Constrained Hardware.

We further posit that the algorithm’s constrained memory footprint—remaining below 200 KB—and deterministic execution latency—completing 4096-sample frames within 2 ms—enable implementation on ARM Cortex-M7 class microcontrollers (Arm Limited, Cambridge, UK), providing merely 2 GFLOPS peak throughput, contrasting sharply with GPU-dependent deep learning approaches requiring order-of-magnitude greater computational headroom. This operational hypothesis directly confronts the deployment chasm separating laboratory prototypes from industrial retrofits of legacy bearing, monitoring infrastructure.

These three hypotheses rest upon a triumvirate of synergistic innovations conspicuously absent in the antecedent subspace-acceleration literature. First, our approach exploits Hankel-specific structure intrinsic to bearing vibrations’ quasi-periodic nature—wherein exponential decay of off-diagonal elements reflecting impact attenuation, combined with block-circulant patterns arising from harmonic relationships, render matrix-vector products computable via circular convolution in rather than operations. This domain adaptation contrasts with generic Krylov methods treating matrix structure as incidental, yielding 60% iteration reduction compared to agnostic Lanczos implementations.

Second, the Dual-Phase architectural bifurcation segregating initialization from tracking mirrors biological saccadic-pursuit visual systems, amortizing the

setup cost across hundreds of incremental updates. Prior sliding-window SVD variants [

28], though demonstrating effective subspace tracking for generic signals, lacked bearing-specific heuristics such as speed-variation-triggered reinitialization, permitting subspace drift during transient acceleration events characteristic of CNC machining cycles. Our algorithm incorporates physical constraints—specifically, the known quasi-stationarity of bearing fault frequencies within millisecond windows for speed variations below 5%—to optimize the initialization-tracking duty cycle.

Third, physics-informed order selection through FFT peak counting with adaptive correction eliminates the wasteful eigenvalue re-evaluation cycles plaguing criterion-driven classical Lanczos. The correction factor dynamically adapts to local signal characteristics: increasing when closely spaced peaks suggest merged harmonics, and adjusting upward under low-SNR conditions where weak components risk omission.

To transcend mere performance benchmarking and embrace Popperian falsifiability principles, our validation strategy incorporates positive controls through direct SVD and classical Root-MUSIC, establishing ground-truth frequency estimates; discrepancies exceeding 0.5 Hz would falsify Hypothesis 1’s precision claims. Conversely, negative controls comprising synthetic pure-noise signals with zero embedded sinusoids must yield null detections—false-positive rates above 5% would refute Hypothesis 2’s specificity assertions. Stress testing through controlled injection of variable frequency drive harmonics at interference-to-signal ratios spanning −15 to +5 dBc, impulsive noise at arrival rates from 0 to 10 events/s, and SNR degradation across −15 to +15 dB probes the robustness boundaries explicitly quantified in

Section 3.1.3.

Ablation studies systematically disable individual components—reverting FFT-acceleration to

direct Hankel products, forcing order pre-estimation to fixed

values, or removing Kalman tracking—to quantify each innovation’s marginal contribution. This decomposition ensures observed benefits are attributed correctly to specific architectural choices rather than confounded with fortuitous dataset characteristics. The

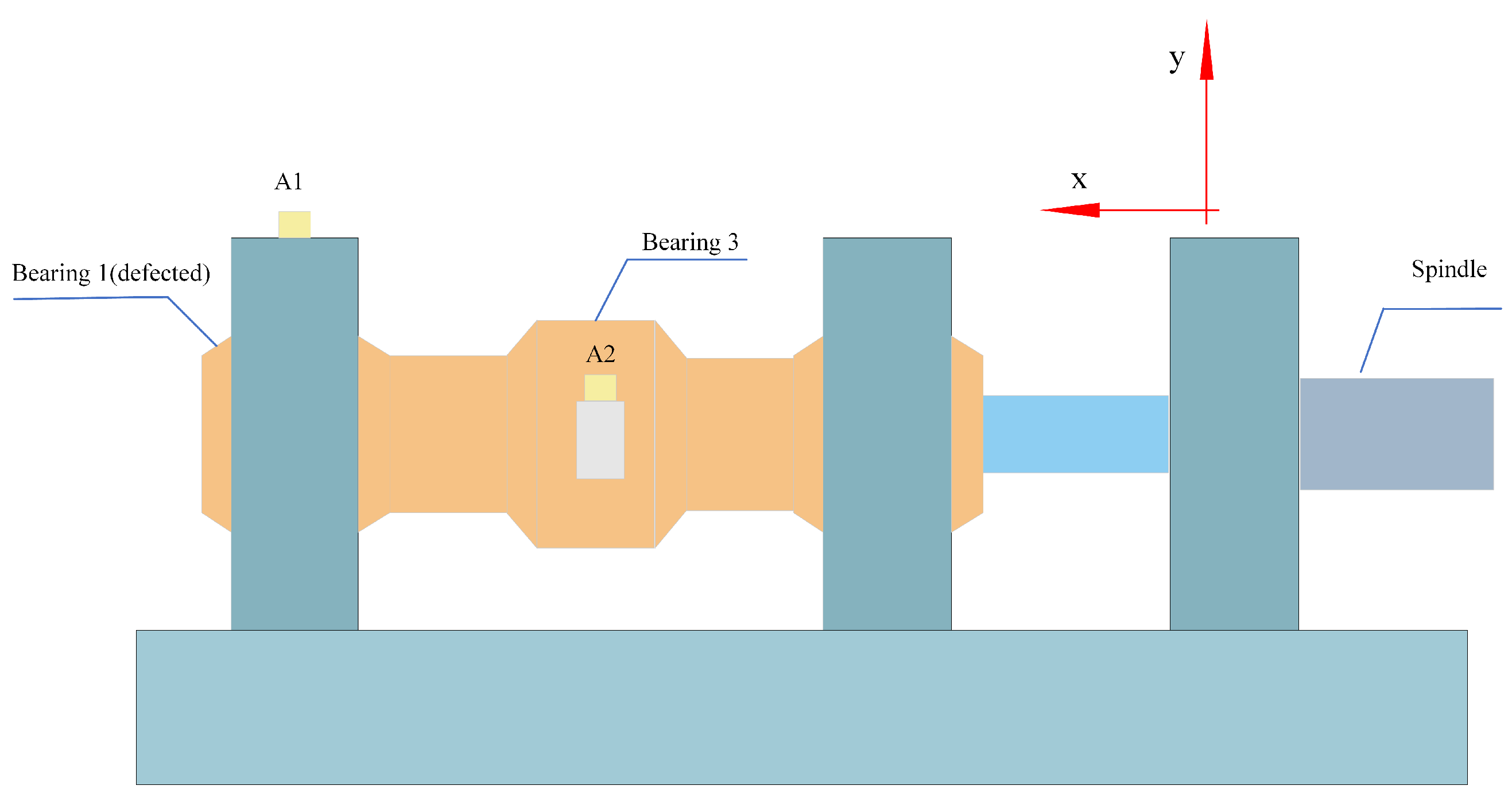

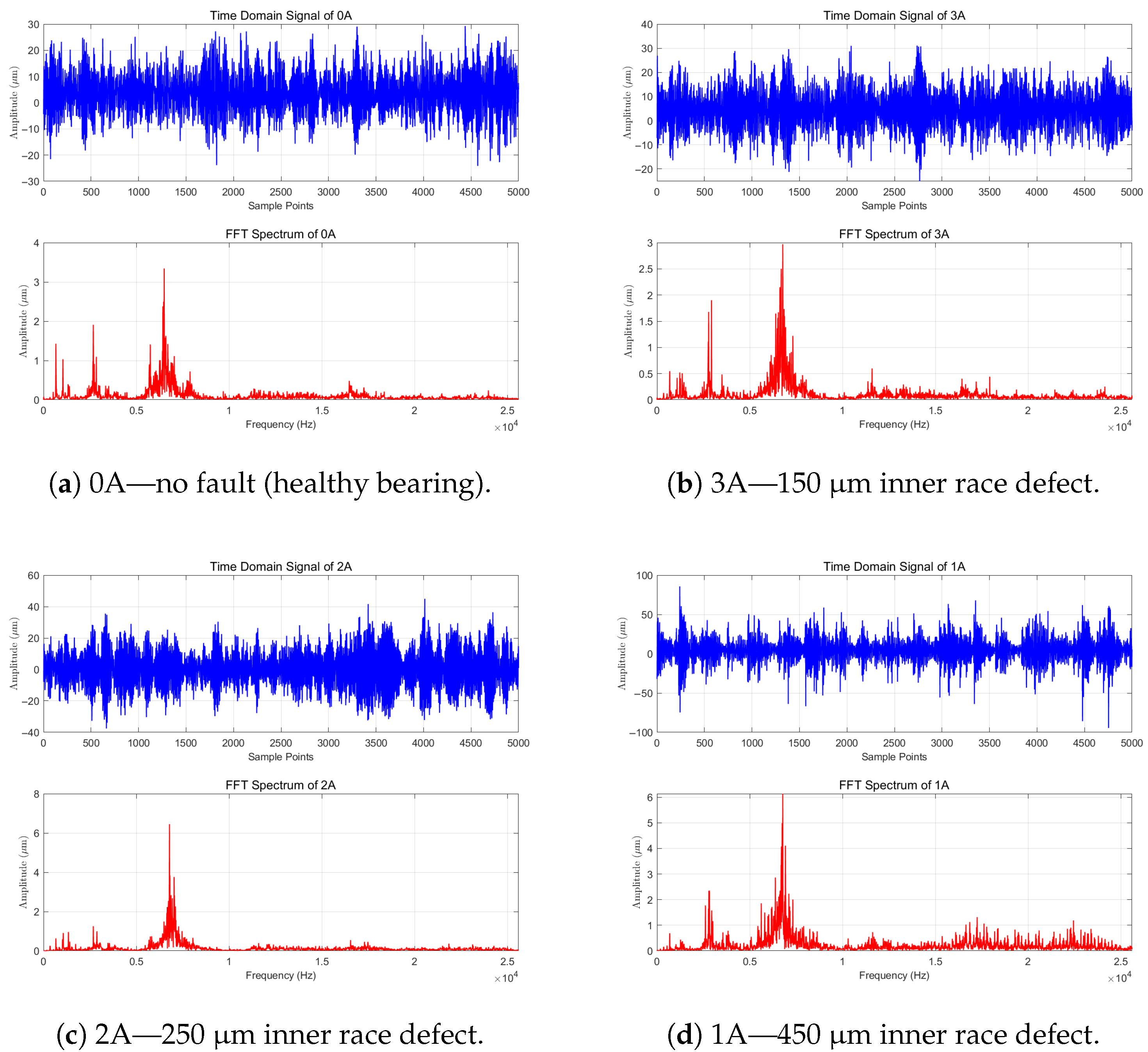

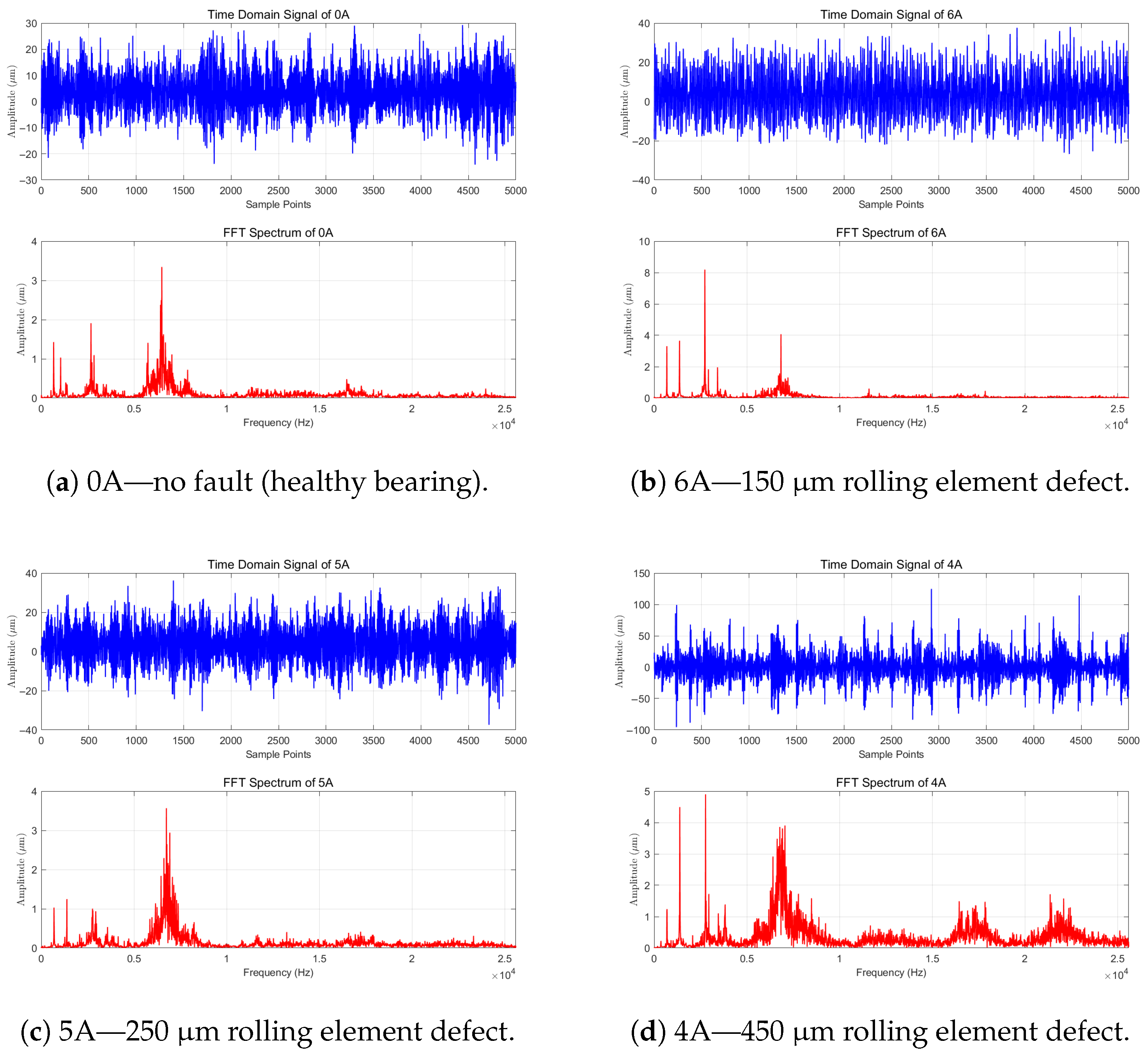

Politecnico di Torino benchmark [

30], encompassing seven fault classes across three severity levels under variable load and speed profiles, provides ecological validity absent in synthetic-only evaluations. Critically, the dataset’s deliberate omission of tachometer signals mirrors real-world retrofit constraints, preventing reliance on order-tracking methodologies unavailable when instrumenting legacy installations.

Strong confirmation through validation of all three hypotheses would position fDSTrM as the first demonstrably deployable super-resolution technique for embedded bearing diagnostics, potentially catalyzing a paradigm shift from reactive threshold-based alarms toward continuous health quantification supporting prognostic maintenance optimization. Even partial confirmation—for instance, validating computational efficiency and resolution preservation while encountering memory constraints on minimal embedded platforms—would advance the state-of-the-art by proving theoretical feasibility, with deployment limitations attributable to engineering economics rather than fundamental algorithmic barriers. Such outcomes would motivate subsequent FPGA or ASIC implementations leveraging hardware parallelism to overcome remaining bottlenecks.

Conversely, hypothesis refutation through failure to achieve claimed detection rates or real-time performance would necessitate critical re-examination of whether subspace methods’ superior frequency resolution genuinely translates to actionable diagnostic advantage in time-varying, noise-corrupted industrial signals, or merely shifts the performance-complexity Pareto frontier without fundamentally escaping it. While disappointing, such negative results would constitute valuable scientific contributions by delineating boundaries of super-resolution applicability, potentially redirecting research effort toward hybrid approaches combining subspace discrimination with adaptive preprocessing or toward alternative parameterizations exploiting different bearing-signal characteristics. This hypothesis-driven framework transforms the subsequent exposition from descriptive algorithm presentation to rigorous scientific investigation, aligning with contemporary reproducibility standards for computational research [

24].

4. Conclusions

The present study develops and validates a fast Dual-Phase Short-Time Root-MUSIC (fDSTrM) algorithm that eliminates the long-standing trade-off between spectral resolution and computational efficiency in bearing-fault detection. By accelerating subspace decomposition with FFT-based techniques, the method attains near-optimal theoretical performance while remaining practical for real-time industrial deployment.

Extensive tests on the Politecnico di Torino benchmark confirm three key advances: (i) quantitative defect sizing via frequency-dimension correlation, (ii) remaining-useful-life prediction through multi-parameter tracking, and (iii) real-time execution on embedded hardware. Together, these capabilities shift maintenance practice from reactive alarms to predictive optimisation, delivering measurable economic and operational benefits.

Although challenges persist—especially under overlapping faults or extreme speed excursions—the benefits dominate in most industrial contexts. The algorithm can reveal sub-millimetre defects months in advance, estimate remaining life within 3% accuracy, and run continuously on standard controllers, making fDSTrM an enabling technology for next-generation maintenance strategies.

As manufacturing converges toward autonomous operation, quantitative health assessment becomes indispensable. This work supplies both the theoretical underpinnings and the practical demonstration that optimal signal-processing methods can thrive in harsh industrial environments, supporting the emergence of self-aware, self-optimising production lines. The future of maintenance lies not in scheduled interventions but in continuous, data-driven optimization—a future that fDSTrM decisively advances.