Prediction of Sandstone-Type Uranium Deposits Based on Data from Oilfield Drilling and Its Mineralization Regularity: A Case Study of Jingchuan Uranium Deposit, SW Ordos Basin

Abstract

1. Introduction

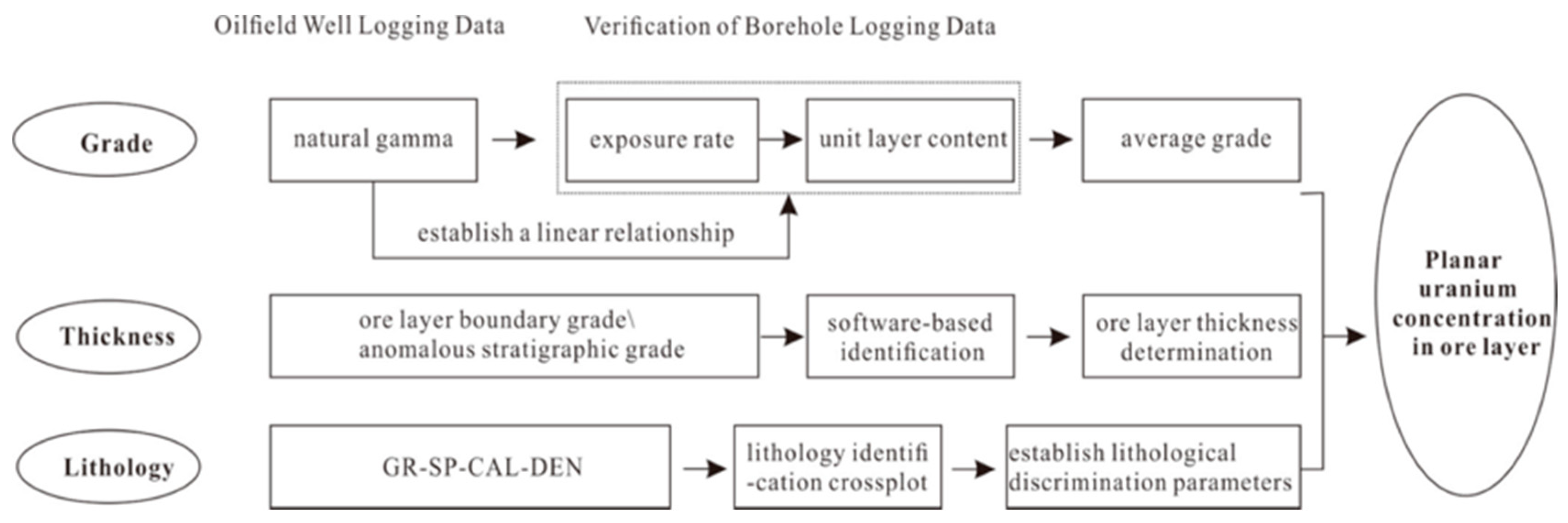

2. A Method for Predicting Sandstone-Type Uranium Deposits Using Borehole and Seismic Data from Oil and Gas Fields

2.1. Feasibility and Technical Route

2.2. Estimating Uranium Accumulation (Ua) Using Natural Gamma Ray (GR) Logs

- Establishing a correlation between GR response and uranium content to determine ore grade;

- Automated detection of mineralized intervals exceeding the cut-off grade and calculation of their cumulative thickness using the Ua screening software;

- Defining lithology discrimination parameters through the analysis of conventional log cross-plots.

2.3. Determination of Key Technical Indicators

2.4. Application Results

3. Sampling and Methods

3.1. Petrographic Analysis

3.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy

3.3. Short-Wave Infrared (SWIR) Drill Core Scanning

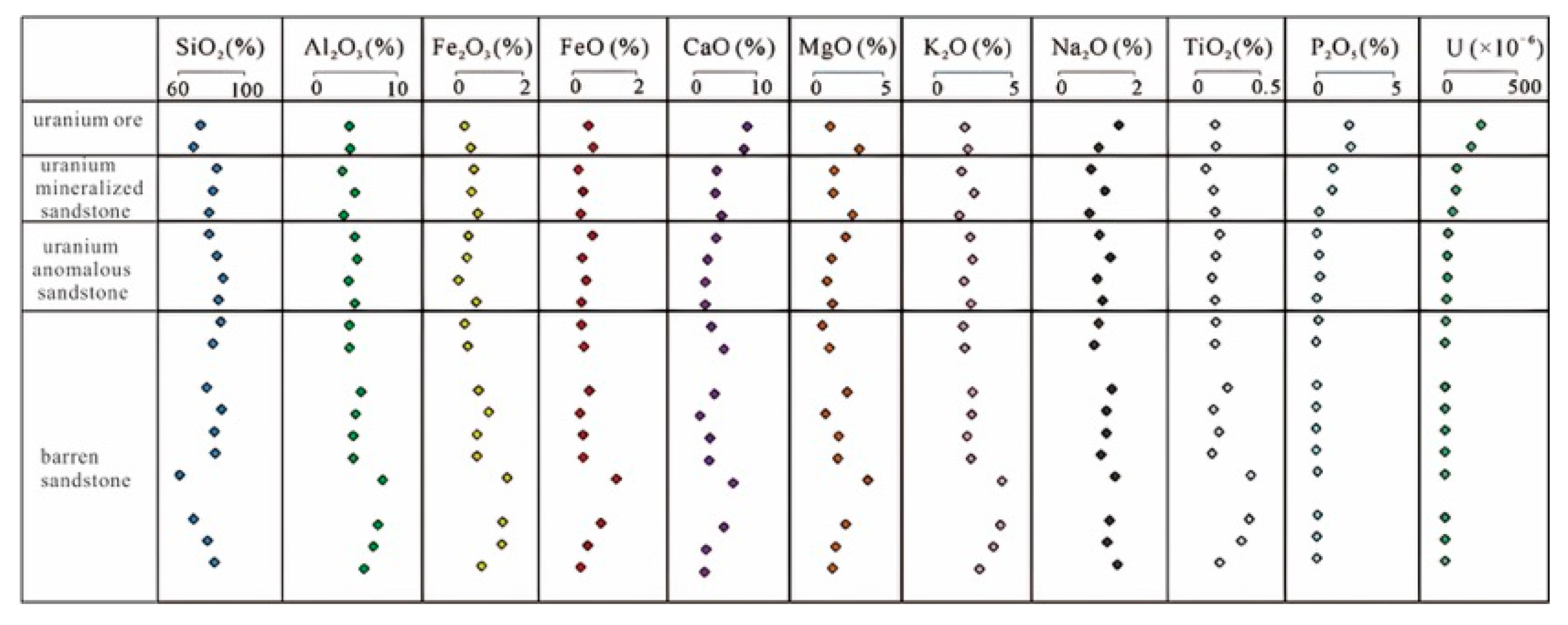

3.4. Major Element Analysis

4. Geological Characteristics and Main Mineralization Regularities of the Jingchuan Uranium Deposit

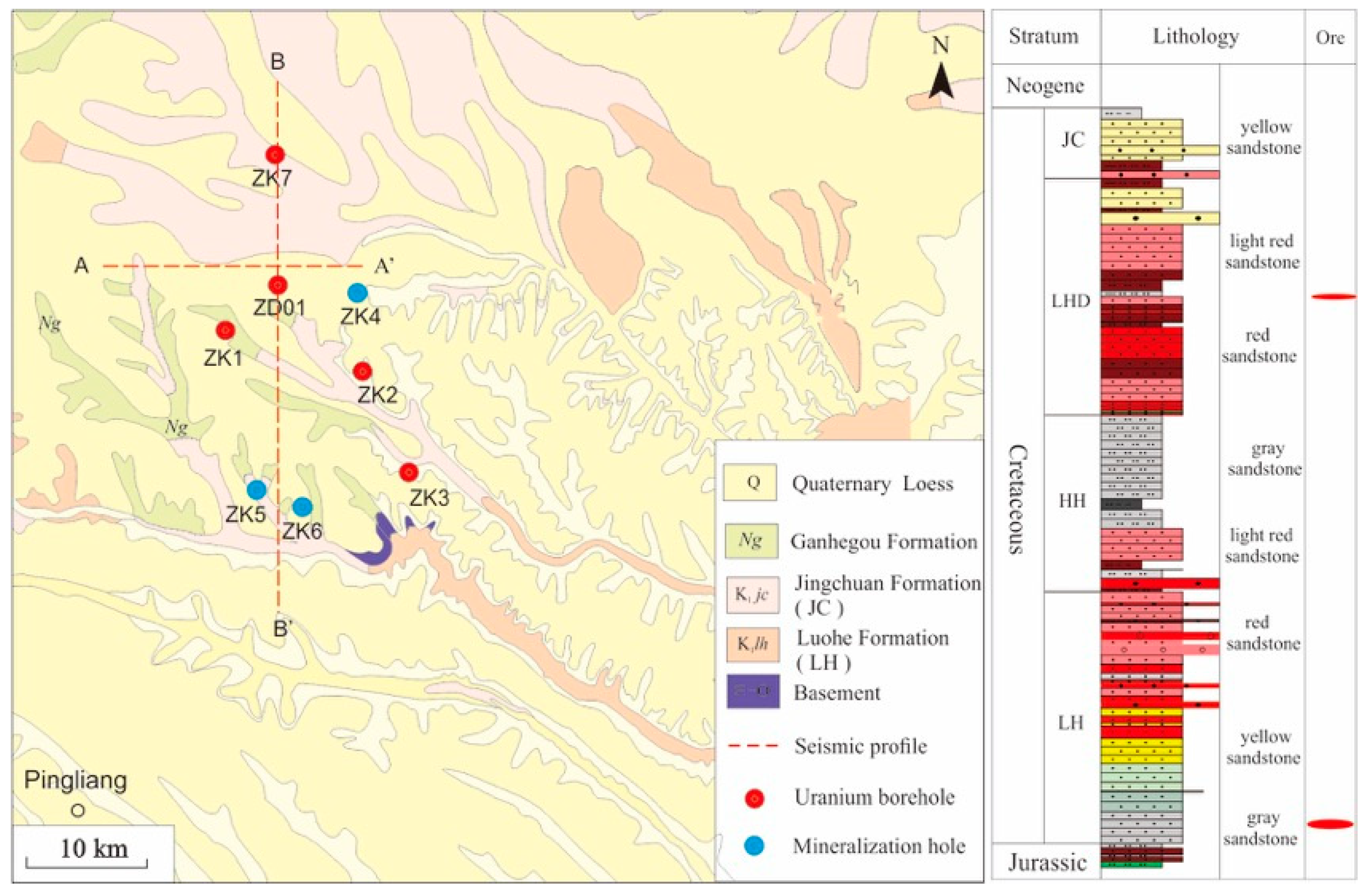

4.1. Regional Geological Characteristics

4.2. Geological Characteristics of the Jingchuan Uranium Deposit

4.2.1. Geological Structural Features

4.2.2. Stratum

4.2.3. Ore Body Characteristics

- Upper unit: Reddish to light red and yellow oxidation zones.

- Middle unit: Gray-dark gray reduction zones hosting uranium mineralization, overlain by oxidation–reduction transition facies.

- Lower unit: Mottled red-gray mixed zones.

4.3. Mineralization Patterns

4.3.1. Source of Ore-Forming Materials

4.3.2. The Occurrence of Uranium Minerals

- Uraninite + rutile;

- Uraninite + pyrite;

- Uraninite/pitchblende + apatite;

- Uraninite + calcite;

- Uraninite + clay minerals.

4.3.3. Mineralization Age

4.3.4. Mineral Composition

4.3.5. Mineralization Model

5. Relationship Between Oil-Gas Systems and Uranium Mineralization

5.1. Spatial Co-Distribution of Hydrocarbons and Uranium

5.2. Roles of Hydrocarbons in Uranium Mineralization: Adsorption and Reduction

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- This study proposes an integrated exploration methodology for discovering sandstone-type uranium deposits within hydrocarbon fields by leveraging existing petroleum infrastructure data. Our approach systematically reevaluates oilfield borehole records and seismic datasets to identify uranium anomalies through comprehensive gamma-ray log screening. This enables precise target delineation for confirmatory drilling, establishing a data-driven pathway for uranium discovery in mature petroleum provinces.

- (2)

- Through a multivariate analysis of critical mineralization controls, including the uranium sources, host stratigraphy, structural frameworks, sedimentary architecture, facies distributions, redox interfaces, hydrocarbon reduction effects, and hydrogeological regimes, we established the first comprehensive metallogenic model for the Jingchuan uranium deposit. This model integrates regional geological characteristics with mineralization mechanisms to provide a predictive framework for uranium exploration in the southwestern Ordos Basin and analogous sedimentary basins globally.

- (3)

- Through systematic synthesis and the analysis of key ore-forming factors of the Jingchuan uranium deposit, including the uranium source, occurrence state of uranium mineralization, associated minerals, mineralization age, and alteration mineral assemblages, this study integrated comprehensive geological characteristics and mineralization regularities. These integrated analyses collectively enabled the establishment of a genetic metallogenic model specific to the Jingchuan uranium deposit, clarifying the processes of uranium source supply, transport, and precipitation.

- (4)

- The Jingchuan uranium deposit represents a paradigm-shifting case study where the comprehensive reevaluation of the petroleum exploration data revealed a major uranium accumulation. Our successful methodology demonstrates the strategic value of data repurposing in hydrocarbon provinces. Furthermore, this research advances our fundamental understanding of uranium mineralization processes by rigorously documenting hydrocarbon-mediated reduction mechanisms—a significant contribution to metallogenic theory.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cuney, M.; Mercadier, J.; Bonnetti, C. Classification of sandstone-related uranium deposits. Earth Sci. 2022, 33, 236–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, R.S.; Teng, X.M. Large scale sandstone-type uranium mineralization in northern China. North China Geol. 2022, 45, 42–57, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- IAEA. Uranium 2024: Resources, Production and Demand; International Atomic Energy Agency: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.H.; Wang, S.Y.; Jin, R.S.; Li, J.G.; Ao, C.; Teng, X.M. Global miocene tectonics and regional sandstone-style uranium mineralization. Ore Geol. Rev. 2019, 106, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.S.; Zhao, X.Q.; Shi, Q.P.; Zhang, Z.N. Research on relationship of oil-gas and sandstone-type uranium mineralization of northern China. China Geol. 2017, 44, 279–287, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wu, B.L.; Liu, C.Y.; Yang, S.L.; Wang, M.; Li, Q.; Lin, Z.Y.; Zhang, X.R.; Li, Y.Q.; Zhang, W.Y.; Liu, M.Y.; et al. Mechanistic and progress of uranium mineralization by organic minerals (oil, gas and coal) in sedimentary basins. J. Northwest Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 52, 1044–1065, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, Y.Q.; Wu, L.Q.; Rong, H.; Zhang, F.; Yue, L.; Song, H.; Tao, Z.P.; Peng, H.; Sun, Y.H.; Xiang, Y. Sedimentation, diagenesis and uranium mineralization: Innovative discoveries and cognitive challenges in study of sandstone-type uranium deposits in China. J. Earth Sci.-China 2022, 47, 3580–3602, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.X.; Ou, G.X.; Han, X.Z.; Cai, Y.Q.; Zheng, E.J.; Li, X.G. Study on the relationship between oil-gas and ore-formation of the in-situ leachable sandstone-type uranium deposit in Yili basin. Acta Geol. Sin. 2006, 80, 112–118, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Quan, J.P.; Fan, T.L.; Xu, G.Z.; Li, W.H.; Chen, H.B. Effects of hydrocarbon migration on sandstone-type uranium mineralization in basins of northern China. China Geol. 2007, 34, 470–477, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.F.; Liu, C.Y.; Qiu, X.W.; Guo, P.; Zhang, S.H.; Cheng, X.H. Characteristics and distribution of world’s identified sandstone-type uranium resources. Acta Geol. Sin. 2017, 91, 2021–2046, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Hall, S.M.; Van Gosen, B.S.; Zielinski, R.A. Sandstone-hosted uranium deposits of the Colorado Plateau, USA. Ore Geol. Rev. 2023, 155, 105353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirkhodjaev, B.; Turesebekov, A.; Ahadov, K.; Askar, R.; Shukhrat, S. Geology and mineralogical-geochemical features of uranium ores of the deposit of Central Kyzylkum. AIP Conf. Proc. 2025, 3268, 030036. [Google Scholar]

- Si, Q.H.; Teng, X.M.; Zhu, Q.; Li, J.G.; Zhao, H.L.; Wang, G.M.; Tong, H.K.; Dang, H.L. The origin and migration laws of hydrocarbons in uranium-bearing Luohe formation, Pengyang area, SW Ordos Basin. Geol. J. 2024, 59, 2703–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.Y.; Ling, M.X.; Lai, X.D.; Sun, W.; Liu, C.Y. Uranium mineral occurrence of sandstone-type uranium deposits in the Dongsheng-Huanglong region, Ordos Basin. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2009, 83, 1167–1177, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.D.; Li, Y.L.; Jian, X.F. Situation and development prospect of uranium resources exploration in China. Eng. Sci. 2008, 10, 54–60, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Jin, R.S.; Miao, P.S.; Sima, X.Z.; Yu, R.A.; Cheng, Y.H.; Tang, C.; Zhang, T.F.; Ao, C.; Teng, X.M. New prospecting progress using information and big data of coal and oil exploration holes on sandstone-type uranium deposit in North China. China Geol. 2018, 1, 167–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Y. Record of the Discovery of the Ordos-Style Large Uranium Deposit. China Mining News. Available online: https://epaper.zgkyb.com/#/detail (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Wu, Z.J.; Han, X.Z. A new uranium exploring technical system for secondary development of coalfield data and its prospecting significance: A case study of the ZS coalfield, Erlian Basin. China Geol. 2016, 43, 617–628, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Z.B.; Nie, B.F.; Nie, F.J.; Li, J.; Xia, F.; Li, M.; Yan, Z.; He, J.; Cheng, R. Application progress of geophysical methods in exploration of sandstone-type uranium deposit. Geophys. Geochem. Explor. 2021, 45, 1179–1188, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Gao, W.L.; Kong, G.S.; Pan, H.P.; Lin, Z.Z.; Qiu, L.Q.; Feng, J.; Fang, S.N.; Deng, C.X.; Li, Y.; Liu, D.M. Geophysical logging in scientific drilling borehole and find of deep Uranium anomaly in Luzong basin. Chin. J. Geophys. 2015, 58, 4522–4533, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.H.; Cha, M.; Jin, Q. Application of natural gamma ray logging and natural gamma spectrometry logging to recovering paleoenvironment of sedimentary basin. Chin. J. Geophys. 2004, 47, 1145–1150, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. The application of natural gamma spectrum logging in Chunguang oilfield. Chin. J. Eng. Geophys. 2018, 15, 299–308, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Yu, R.A.; Sun, D.P.; Zhou, X.X.; Deng, F.; Si, Q.H.; Hu, Y.X. Preliminary investigation of uranium resource evaluation method based on natural gamma logging data: A case study of the Pengyang uranium deposit in Ordos Basin. Coal Geol. Explor. 2022, 50, 144–152, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.H.; Yu, R.A.; Tang, C.; Wang, J.Y.; Zhu, Q.; Xu, Z.L.; Zhao, H.L.; Si, Q.H.; Zeng, W.; Chen, L.L.; et al. New round strategic prospecting, Tianjin Center, China Geological Survey in action: Major breakthroughs in uranium prospecting achieved in multiple northern basins. China Geol. 2024, 51, 1–2. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Wang, Q.F.; Gao, B.F.; Huang, D.H.; Yang, L.Q. Evolution of ordos basin and its distribution of various energy resources. Geoscience 2005, 19, 538–545, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.Y.; Zhao, H.G.; Wang, F.; Chen, H. Attributes of the mesozoic structure on the west margin of the Ordos basin. Acta Geol. Sin. 2005, 79, 738–747, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Xue, C.J.; Xue, W.; Kang, M.; Tu, Q.J.; Yang, Y.Y. The Fluid Dynamic Processes and its uranium mineralization of sandstone-type in the Ordos basin, China. Geoscience 2008, 22, 1–8, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.L.; Li, J.G.; Miao, P.S.; Chen, L.L.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, Q.; Si, Q.H.; Chen, Y.; Hu, Y.X.; Guo, H. Mineralogical study of pengyang uranium deposit and its significance of regional mineral exploration in southwestern Ordos basin. Geotect. Metallog. 2020, 44, 607–618, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Ren, J.F.; Shi, P.P.; Zhang, T.; Wei, L.B.; Bao, H.P.; Wang, Q.P. Characteristics and exploration potential of ordovician subsalt gas-bearing system in the Ordos basin. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2024, 35, 435–448. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Li, J.G.; Miao, P.S.; Chen, L.L.; Zhao, H.L.; Wang, C.; Yang, J. Relationship between the tectono-thermal events and sandstone-type uranium mineralization in the southwestern Ordos basin, northern China: Insights from apatite and zircon fission track analyses. Ore Geol. Rev. 2022, 143, 104792. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, S.J.; Yu, C.Q.; Nie, F.J.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, C.; Li, W.Q.; Fan, P.X. Exploring the relationship between shallow sandstone-type uranium deposits and deep oil and gas in the Pengyang area of the Ordos basin based on seismic data. Prog. Geophys. 2025, 40, 524–540, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Jin, R.S.; Zhu, Q. Supernormal enrichment mechanism and metallogenic process of sandstone type uranium deposit in the eolian sedimentary system in Jingchuan area, Ordos basin. Acta Geol. Sin. 2023, 97, 725–737, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.B.; Chen, G.; Zhang, H.R.; Bai, G.J.; Li, X.D.; Li, X.P. Peak ages and sedimentary responses of the mesozoic-cenozoic tectonic events in Ordos basin. Northwest. Geol. 2006, 39, 91–96, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.H.; Gao, R.; Wang, H.Y.; Li, Y.K.; Li, H.Q.; Hou, H.S.; Xiong, X.S.; Guo, X.Y.; Xu, X.; Zou, C.Q.; et al. Crustal structure beneath the Liupanshan fault zone and adjacent regions. Chin. J. Geophys. 2017, 60, 2265–2278, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, D.W.; Kuang, H.W.; Liu, Y.Q.; Peng, N.; Liu, Y.X.; Xu, H.; Cui, L.W.; Li, Z.Q. Identification of eolian sandstone in cretaceous uraniferous sandstone in Ordos basin, China. Geotect. Metallog. 2017, 44, 648–666, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.S.; Yang, X.Y.; Miao, P.S.; Hu, X.; Chen, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhao, H. Mineralogical and geochemical research on Pengyang deposit: A peculiar eolian sandstone-hosted uranium deposit in the southwest of Ordos basin. Ore Geol. Rev. 2022, 141, 104571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Miao, P.S.; Xiao, K.Y.; Li, J.G.; Zhao, H.L.; Chen, Y.; Tang, C.; Si, Q.H.; Zhu, Q. Quantitative Gold Resources Prediction in Xiahe–Hezuo Area Based on Convolutional Auto-Encode Network. Acta Geosci. Sin. 2023, 44, 897–908, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Li, J.G.; Miao, P.S.; Chen, L.L.; Zhao, H.L.; Wang, C. U-Pb ages and Hf isotopes of detrital zircons from the Cretaceous succession in the southwestern Ordos basin, northern China: Implications for provenance and tectonic evolution. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2021, 219, 104896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.R.; Liu, L.; Jia, S.J.; Li, R.Q.; Gong, Y.D. Geochemical and provenance characteristics of eolian sandstone of Cretaceous Luohe Formation in Ordos basins: An example from outcrop in Longzhou, Jingbia. Glob. Geol. 2018, 37, 702–711, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Li, J.G.; Miao, P.S.; Zhao, L.; Si, Q.H.; Li, H.L.; Cao, M.Q.; Zhu, Q.; Wei, J.L. The occurrence state and origin of uranium in Qianjiadian uranium deposit, Kailu Basin. North China Geol. 2021, 44, 40–48, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wen, S.B.; Zhu, Q.; Cheng, Y.H. Metallogenic epoch of sandstone type uranium deposits in the Ordos Basin and the temporal and spatial regularity of uranium enrichment. North China Geol. 2023, 46, 1–11, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.F.; Liu, C.Y.; Niu, H.Q.; Zhou, N.C.; Li, X.H.; Luo, W.; Zhang, D.D.; Zhao, Y. In-situ chemical age of the sandstone-hosted uranium deposit in Ningdong area on the western margin of the Ordos Basin, North China. Acta Geol. Sin. 2018, 92, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Li, J.G.; Miao, P.S.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, H.L.; Si, Q.H.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, P. Characteristics of clay minerals in the Luohe formation in Zhenyuan area, Ordos basin, and its uranium prospecting significance. Geotect. Metallog. 2020, 44, 619–632, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C.; Sima, X.Z.; Zhu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, P.; Liu, X.X.; Zhao, L.J. Research on the relationship between oil gas and sandstone-type uranium mineralization in sedimentary basin. Contr. Geol. Miner. Resour. Res. 2017, 32, 286–294, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.H.; Jin, R.S.; Cuney, M.; Petrov, V.A.; Miao, P.S. The strata constraint on large scale sandstone-type uranium mineralization in Meso-Cenozoic basins, northern China. Acta Geol. Sin. 2024, 98, 1953–1976, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.H.; Jin, R.S.; Miao, P.S.; Wang, S.Y.; Teng, X.M. Two metallogenic models of sedimentary-hosted uranium deposit: Jingchuan and Tale types. J. Earth Sci. 2025, 50, 46–57, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, Y.Q.; Wu, L.Q.; Yang, Q. Uranium reservoir: A new concept in geology of sandstone-type uranium deposits. Geol. Sci. Technol. Inf. 2007, 26, 1–7, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Tuo, C.R.; Huang, Z.X. The Symbiotic mechanism of uranium and hydrocarbon in sedimentary basin. Contr. Geol. Miner. Resour. Res. 2016, 31, 529–537, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.M. Dynamics of sedimentary basins and basin-fluid related ore-forming. Bull. Mineral. Petrol. Geochem. 2000, 19, 76–84, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Lecomte, A.; Michels, R.; Cathelineau, M.; Morlot, C.; Brouand, M.; Flotté, N. Uranium deposits of Franceville basin (Gabon): Role of organic matter and oil cracking on uranium mineralization. Ore Geol. Rev. 2020, 123, 103579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, W.; Wu, K.; Li, S.; Peng, P.; Qin, Y. Uranium enrichment in lacustrine oil source rocks of the Chang 7 member of the Yanchang formation, Ordos basin, China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2010, 39, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; He, Z.B.; He, M.Y. Research on relationship of oil-gas and sandstone-type uranium mineralization. J. Southwest Univ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 28, 39–43, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.B.; Xu, G.Z. Direct evidences for reduction of pitchblende by pitch in the Sawapuqi uranium deposit, Xinjiang. Bull. Mineral. Petrol. Geochem. 2007, 26, 245–248, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Akhter, S.; Yang, X.Y.; Pirajno, F. Sandstone type uranium deposits in the Ordos basin, Northwest China: A case study and an overview. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2017, 146, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.G.; Zhang, B.; Jin, R.S.; Si, Q.H.; Miao, P.S.; Li, H.L.; Cao, M.Q.; Wei, J.L.; Chen, Y. Uranium mineralization of coupled supergene oxygen-uranium bearing fluids and deep acidic hydrocarbon bearing fluids in the Qianjiadian uranium deposit, Kailu basin. Geotecton. Metallog. 2020, 44, 576–589, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Wu, B.L.; Li, Y.Q.; Liu, C.Y.; Hao, X.; Liu, M.Y.; Zhang, W.Y.; Li, Q.; Yao, L.H.; Zhang, X.R. Experimental study on possibility of deep uranium-rich source rocks providing uranium source in Ordos basin. Earth Sci. 2022, 47, 224–239, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Fu, X.F.; Li, Y.C.; Wang, H.X.; Sun, B.; Hao, Y.; Hu, H.T.; Yang, Z.C.; Li, Y.L.; Gu, S.F.; et al. Can hydrocarbon source rock be uranium source rock?—A review and prospectives. Earth Sci. Front. 2024, 31, 284–298, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, B.; Cheng, Y.; Xiao, K.; Yu, R.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Wen, S. Prediction of Sandstone-Type Uranium Deposits Based on Data from Oilfield Drilling and Its Mineralization Regularity: A Case Study of Jingchuan Uranium Deposit, SW Ordos Basin. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11268. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011268

Zhang B, Cheng Y, Xiao K, Yu R, Chen Y, Zhu Q, Wen S. Prediction of Sandstone-Type Uranium Deposits Based on Data from Oilfield Drilling and Its Mineralization Regularity: A Case Study of Jingchuan Uranium Deposit, SW Ordos Basin. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(20):11268. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011268

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Bo, Yinhang Cheng, Keyan Xiao, Rengan Yu, Yin Chen, Qiang Zhu, and Sibo Wen. 2025. "Prediction of Sandstone-Type Uranium Deposits Based on Data from Oilfield Drilling and Its Mineralization Regularity: A Case Study of Jingchuan Uranium Deposit, SW Ordos Basin" Applied Sciences 15, no. 20: 11268. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011268

APA StyleZhang, B., Cheng, Y., Xiao, K., Yu, R., Chen, Y., Zhu, Q., & Wen, S. (2025). Prediction of Sandstone-Type Uranium Deposits Based on Data from Oilfield Drilling and Its Mineralization Regularity: A Case Study of Jingchuan Uranium Deposit, SW Ordos Basin. Applied Sciences, 15(20), 11268. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011268