Seismic Facies Recognition Based on Multimodal Network with Knowledge Graph

Abstract

1. Introduction

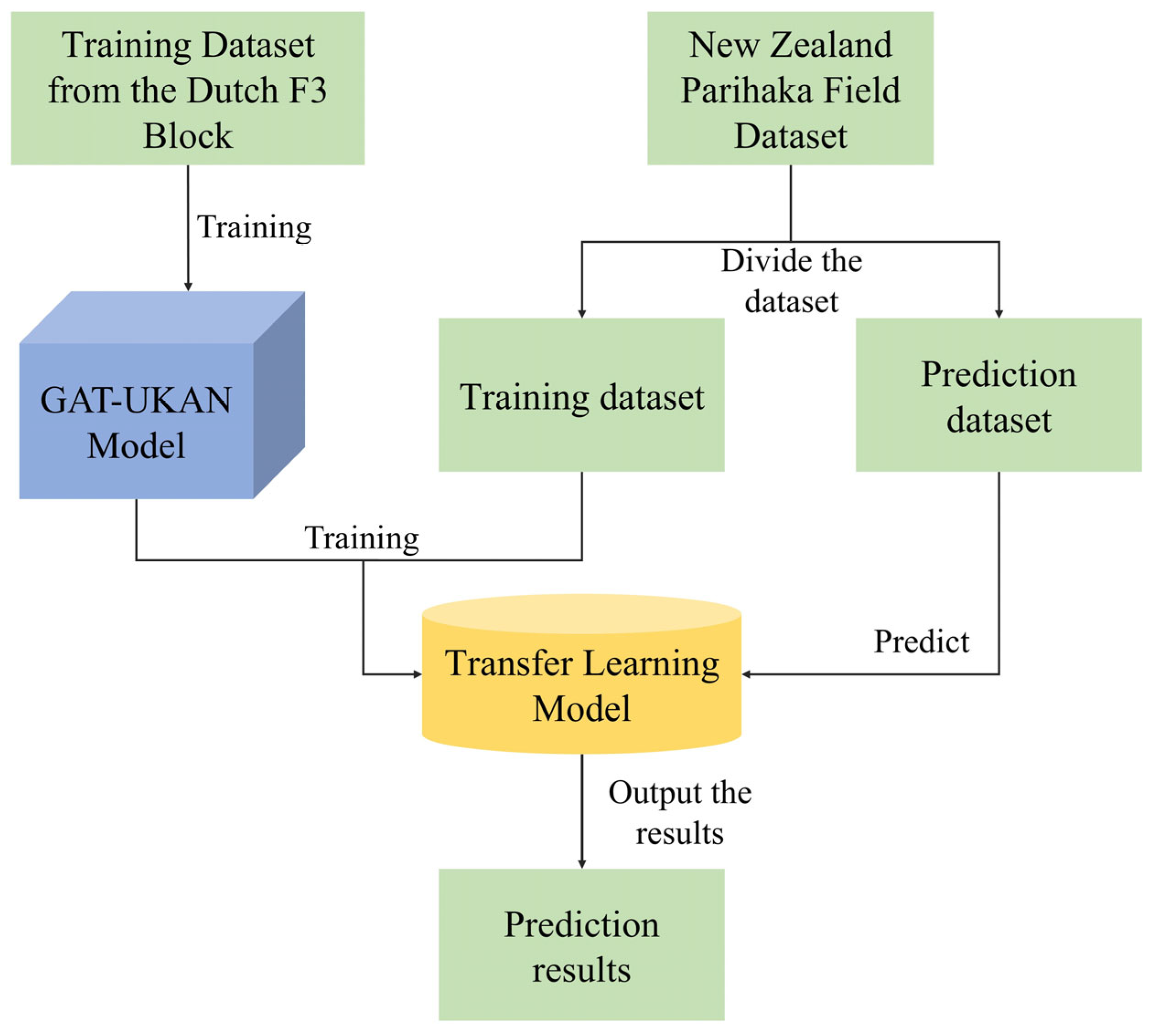

2. Materials and Methods

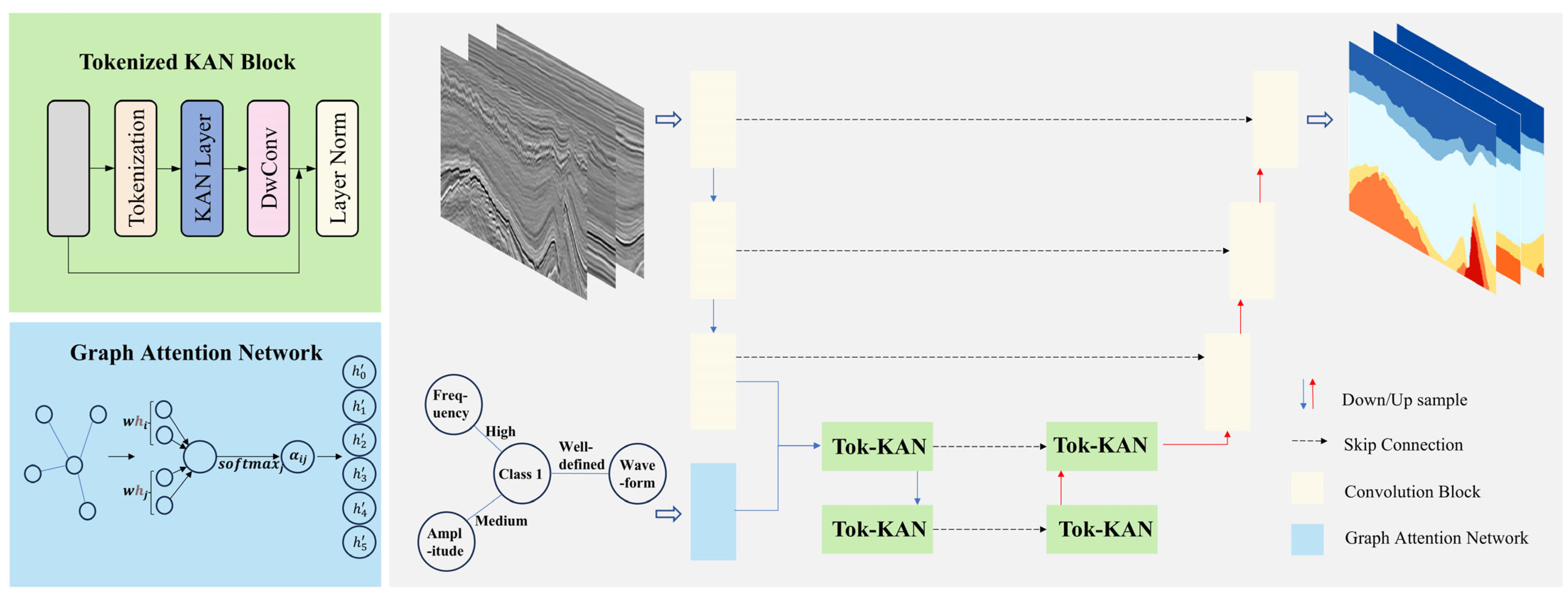

2.1. Architecture Overview

2.2. Convolutional Block

2.3. GAT

2.4. Tokenized KAN Module

2.5. Decoder

3. Results

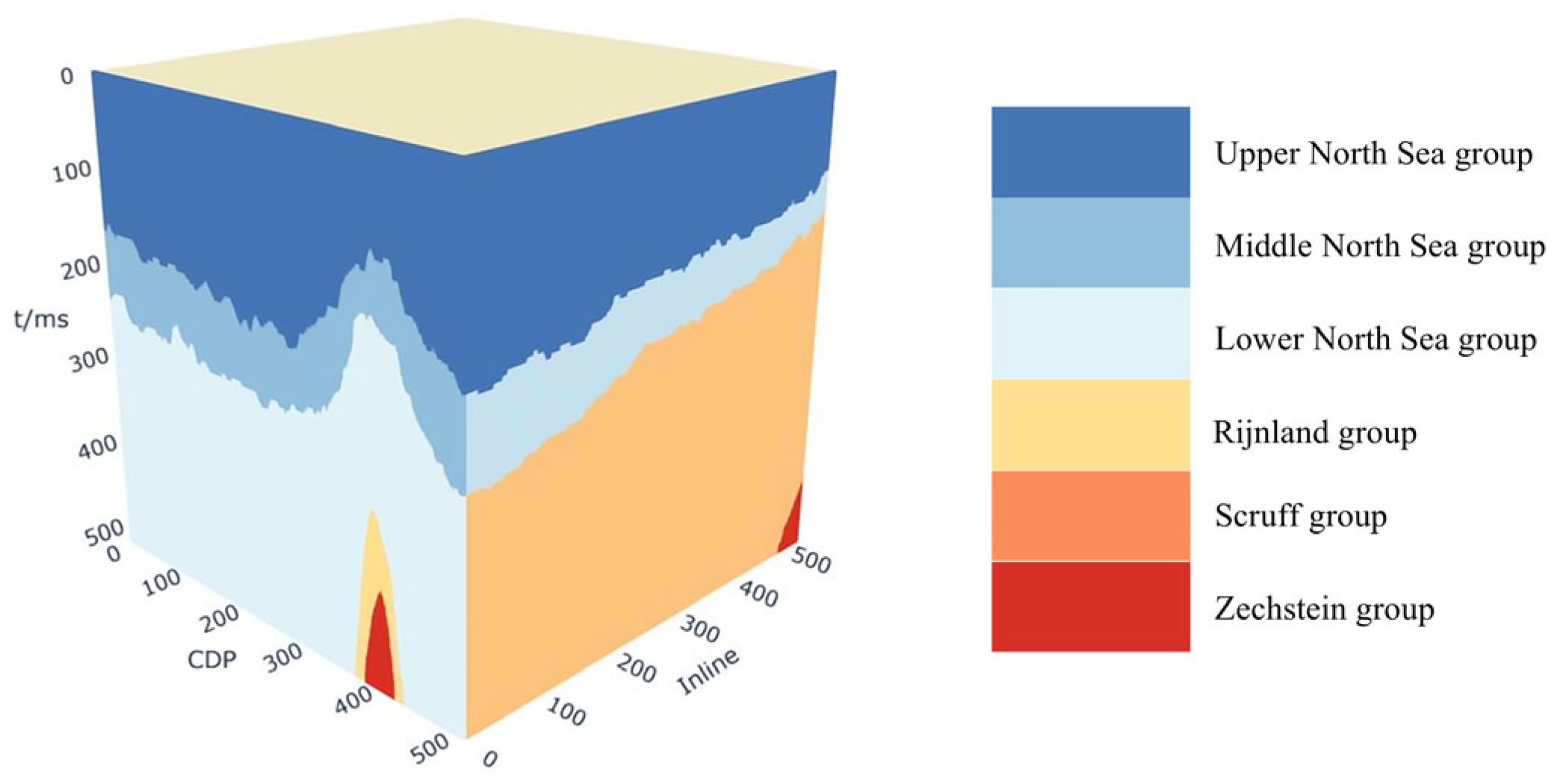

3.1. Experimental Setup and Evaluation Matrices

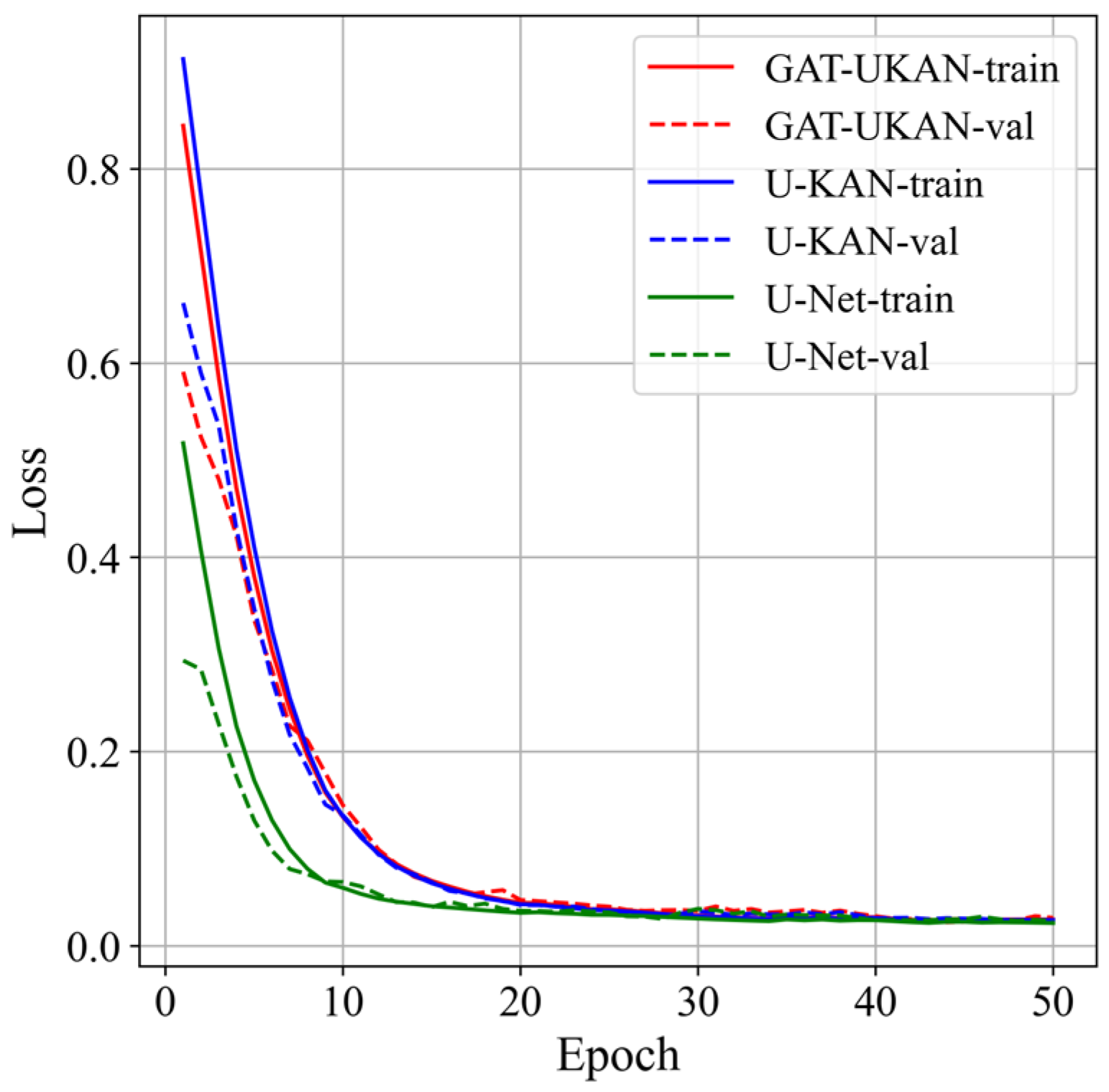

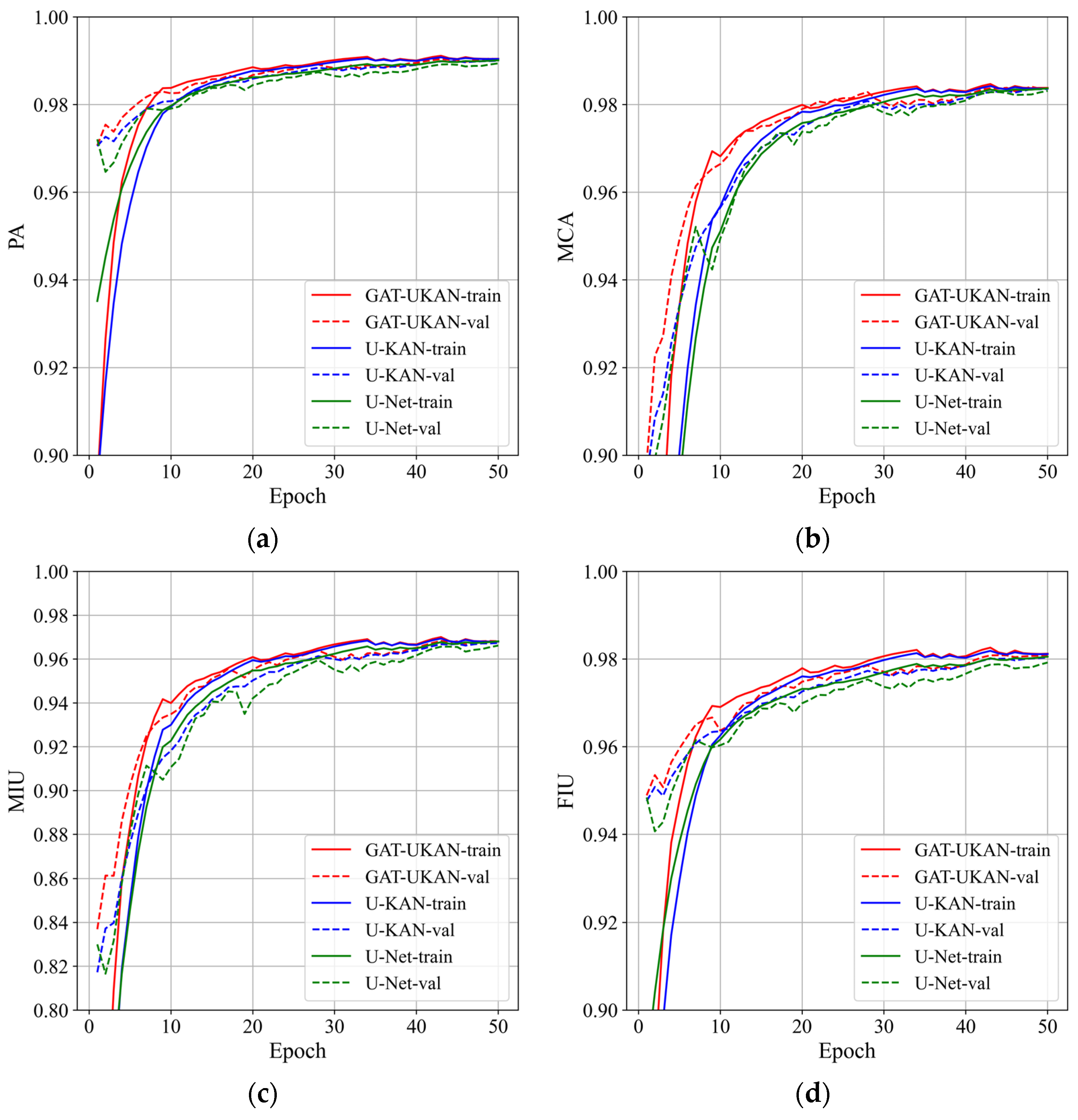

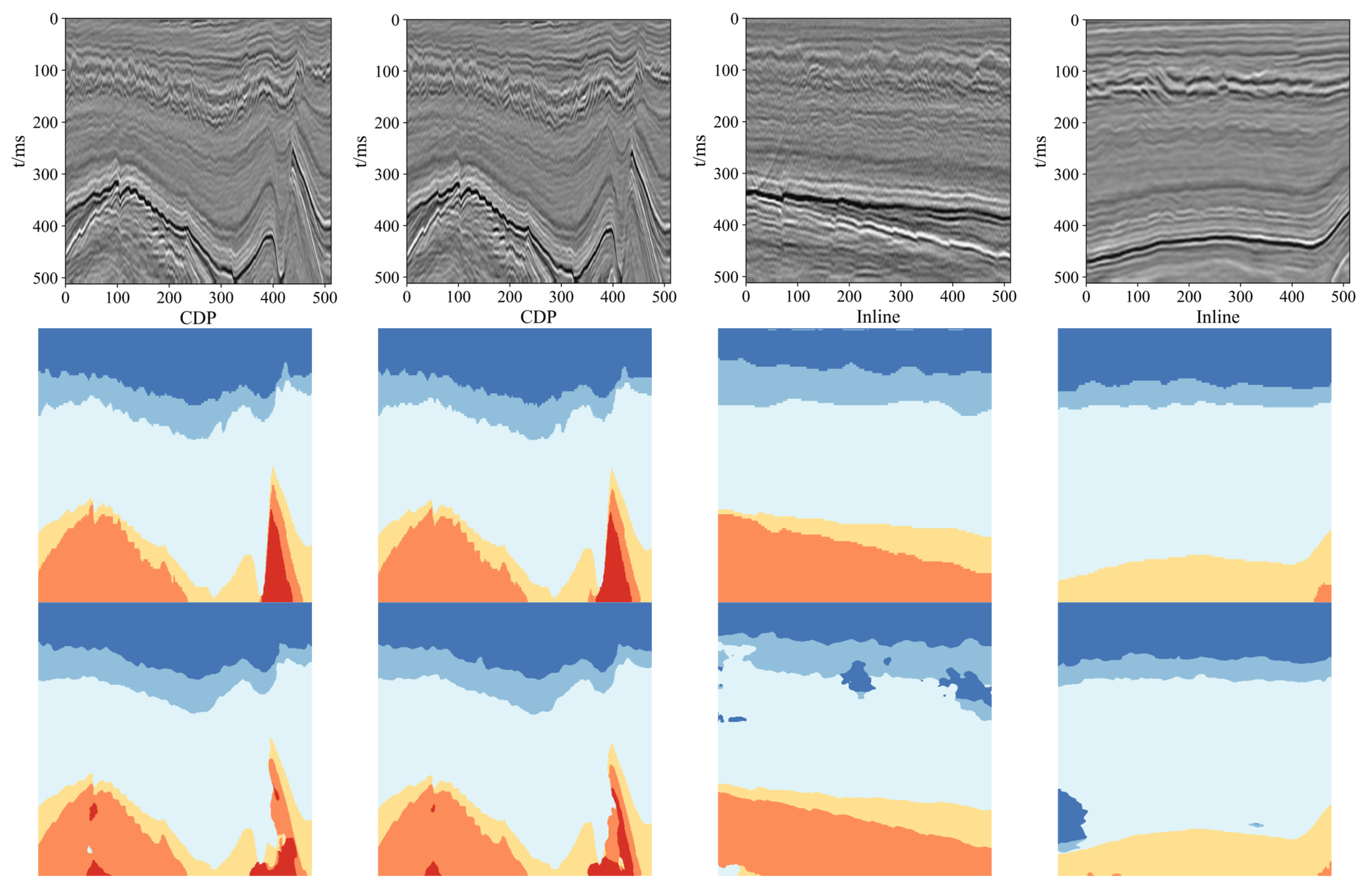

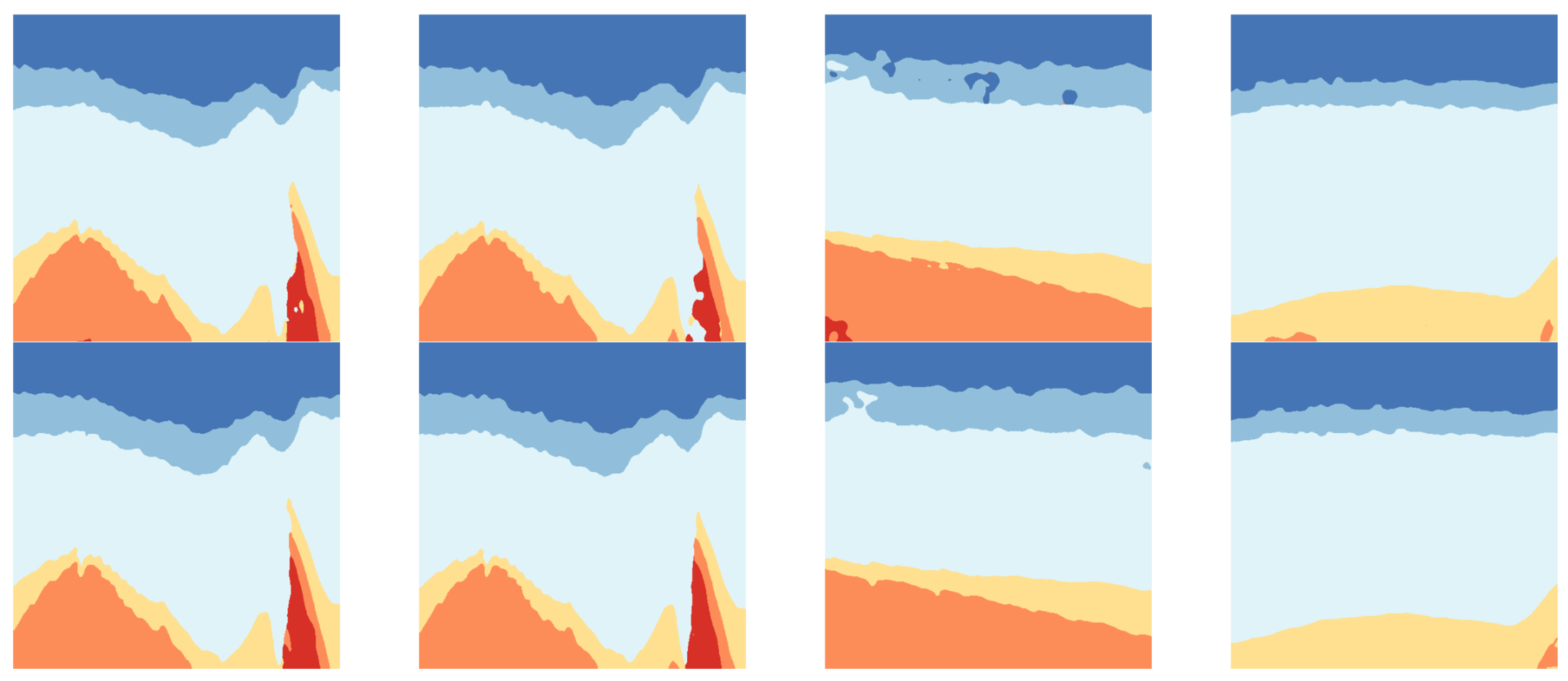

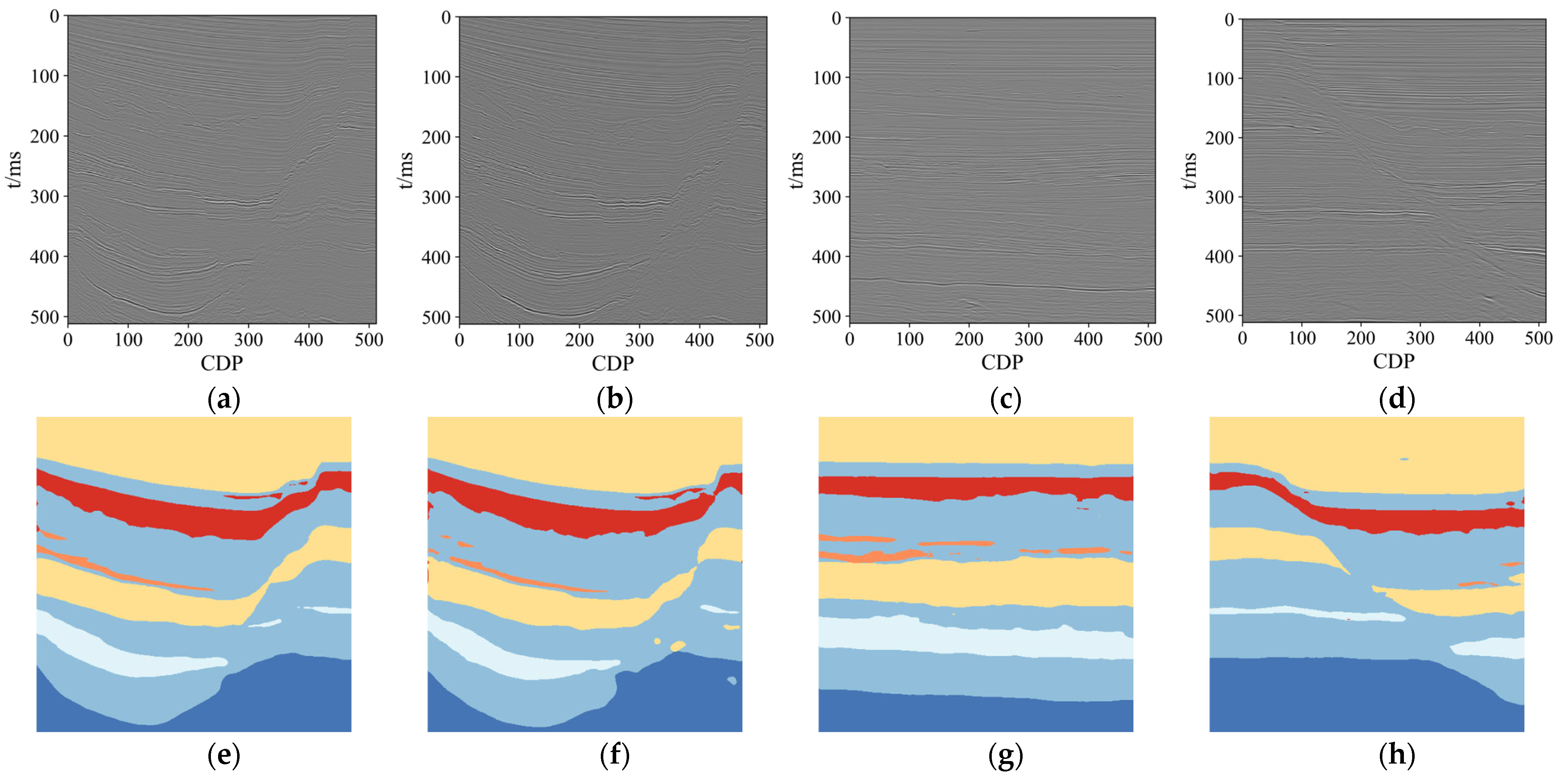

3.2. Experimental Results

3.3. Transfer Learning

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nasim, M.Q.; Maiti, T.; Srivastava, A.; Singh, T.; Mei, J. Seismic Facies Analysis: A Deep Domain Adaptation Approach. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 4508116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Haq, B.U. Seismic Facies Analysis: Past, Present and Future. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2022, 224, 103876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roksandić, M.M. Seismic Facies Analysis Concepts. Geophys. Prospect. 1978, 26, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrona, T.; Pan, I.; Gawthorpe, R.L.; Fossen, H. Seismic Facies Analysis Using Machine Learning. Geophysics 2018, 83, O83–O95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu, B.A.; Boateng, C.D.; Asare, V.-D.S.; Danuor, S.K.; Adenutsi, C.D.; Quaye, J.A. Seismic Facies Analysis Using Machine Learning Techniques: A Review and Case Study. Earth Sci. Inf. 2024, 17, 3899–3924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Hu, G. Multi-Waveform Classification for Seismic Facies Analysis. Comput. Geosci. 2017, 101, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Chen, X.; Wang, B.; Li, J.; Dai, H. An Improved Method for Lithology Identification Based on a Hidden Markov Model and Random Forests. Geophysics 2020, 85, IM27–IM36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Cui, Y.-A.; Zhou, L.; Li, J.-Y.; Pan, X.-P.; Sun, Y.; Liu, J.-X. Multi-Task Learning for Seismic Elastic Parameter Inversion with the Lateral Constraint of Angle-Gather Difference. Pet. Sci. 2024, 21, 4001–4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zou, Q.; Xu, X.; Wang, N. A Stronger Baseline for Seismic Facies Classification With Less Data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5914910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J. Automatic Seismic Facies Interpretation Using Supervised Deep Learning. Geophysics 2021, 86, IM15–IM33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Zhao, J.; Huang, X.; Zhang, G.; Chen, A.; Hou, M.; Cao, J. Explainable Convolutional Neural Networks Driven Knowledge Mining for Seismic Facies Classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5911118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Pham, N.; Fomel, S.; Geng, Z.; Decker, L.; Gremillion, B.; Jervis, M.; Abma, R.; Gao, S. A Deep Learning Framework for Seismic Facies Classification. Interpretation 2023, 11, T107–T116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, B.; Khan, B.M.; Memon, R.A. Seismic Facies Segmentation Using Ensemble of Convolutional Neural Networks. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2022, 2022, 7762543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Liu, N.; Chen, Y.; Gao, J. Seismic Facies Segmentation via a Segformer-Based Specific Encoder–Decoder–Hypercolumns Scheme. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5903411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su-Mei, H.; Zhao-Hui, S.; Meng-Ke, Z.; San-Yi, Y.; Shang-Xu, W. Incremental Semi-Supervised Learning for Intelligent Seismic Facies Identification. Appl. Geophys. 2022, 19, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldeland, A.U.; Jensen, A.C.; Gelius, L.-J.; Solberg, A.H.S. Convolutional Neural Networks for Automated Seismic Interpretation. Lead. Edge 2018, 37, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Zhou, H.; Liu, X.; Liu, C. Seismic facies identification based on Res-UNet and transfer learning. Processes 2024, 39, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlSalmi, H.; Elsheikh, A.H. Automated Seismic Semantic Segmentation Using Attention U-Net. Geophysics 2024, 89, WA247–WA263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Routray, A.; Dharavath, S.B.; Dam, T. OrthoSeisnet: Seismic Inversion through Orthogonal Multi-Scale Frequency Domain U-Net for Geophysical Exploration. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.04393.2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Gao, J.; Chen, H. Seismic Facies Classification Based on Multilevel Wavelet Transform and Multiresolution Transformer. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5903412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, S.; Sharma, M. U-Net Based Image Segmentation Drawbacks in Medical Images: A Review. In Innovations in Sustainable Technologies and Computing; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 361–372. ISBN 978-981-97-1110-9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, F.; Zhang, C.; Geng, B. Deep Multimodal Data Fusion. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, J.N.; Falcone, G.J.; Rajpurkar, P.; Topol, E.J. Multimodal Biomedical AI. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1773–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, P.P.; Zadeh, A.; Morency, L.-P. Foundations & Trends in Multimodal Machine Learning: Principles, Challenges, and Open Questions. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, M. Multimodal Reasoning with Multimodal Knowledge Graph. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.02030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amendola, A.; Gabbriellini, G.; Dell’Aversana, P.; Marini, A.J. Seismic Facies Analysis through Musical Attributes. Geophys. Prospect. 2017, 65, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, X.; Li, J.; Ma, K.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y. Sedimentary Facies Identification Technique Based on Multimodal Data Fusion. Processes 2024, 12, 1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veličković, P.; Cucurull, G.; Casanova, A.; Romero, A.; Liò, P.; Bengio, Y. Graph Attention Networks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1710.10903.2018. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Liu, X.; Li, W.; Wang, C.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yuan, Y. U-KAN Makes Strong Backbone for Medical Image Segmentation and Generation. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2025, 39, 4652–4660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarrasi, V.; Aksu, F.; Caruso, C.M.; Di Feola, F.; Rofena, A.; Ruffini, F.; Soda, P. A Systematic Review of Intermediate Fusion in Multimodal Deep Learning for Biomedical Applications. Image Vis. Comput. 2025, 158, 105509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Meng, B.; Chen, H.; Meng, Y.; Lv, K.; Zhu, W. TIVA-KG: A Multimodal Knowledge Graph with Text, Image, Video and Audio. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 26 October 2023; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 2391–2399. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Song, Z.; Tang, C. Multi-Scale Spatial Pyramid Attention Mechanism for Image Recognition: An Effective Approach. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 133, 108261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Zhao, J.; Peng, K.; Qian, L.; Li, M.; Pan, R. 3D Karst Cave Recognition Using TransUnet with Dual Attention Mechanisms in Seismic Images. Geophysics 2025, 90, IM133–IM143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Baruch, E.; Ridnik, T.; Zamir, N.; Noy, A.; Friedman, I.; Protter, M.; Zelnik-Manor, L. Asymmetric Loss For Multi-Label Classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference On Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Model | PA | MCA | MIU | FIU |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U-Net | 0.868 | 0.799 | 0.659 | 0.773 |

| U-KAN | 0.880 | 0.808 | 0.664 | 0.806 |

| GAT-UKAN | 0.897 | 0.824 | 0.706 | 0.826 |

| Model | Class 1 | Class 2 | Class 3 | Class 4 | Class 5 | Class 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U-Net | 0.980 | 0.877 | 0.950 | 0.885 | 0.546 | 0.556 |

| U-KAN | 0.986 | 0.884 | 0.973 | 0.886 | 0.549 | 0.577 |

| GAT-UKAN | 0.988 | 0.899 | 0.976 | 0.889 | 0.643 | 0.578 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, B.; Li, M.; Pan, R.; Zhao, J. Seismic Facies Recognition Based on Multimodal Network with Knowledge Graph. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11087. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011087

Yan B, Li M, Pan R, Zhao J. Seismic Facies Recognition Based on Multimodal Network with Knowledge Graph. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(20):11087. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011087

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Binpeng, Mutian Li, Rui Pan, and Jiaqi Zhao. 2025. "Seismic Facies Recognition Based on Multimodal Network with Knowledge Graph" Applied Sciences 15, no. 20: 11087. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011087

APA StyleYan, B., Li, M., Pan, R., & Zhao, J. (2025). Seismic Facies Recognition Based on Multimodal Network with Knowledge Graph. Applied Sciences, 15(20), 11087. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011087