VR-Based Teleoperation of UAV–Manipulator Systems: From Single-UAV Control to Dual-UAV Cooperative Manipulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1

- Proposed an intuitive VR-based teleoperation framework for aerial manipulation, enabling simultaneous control of a UAV and its onboard manipulator through natural hand motions captured by VR controllers, without relying on dense button mappings or predefined gestures.

- 2

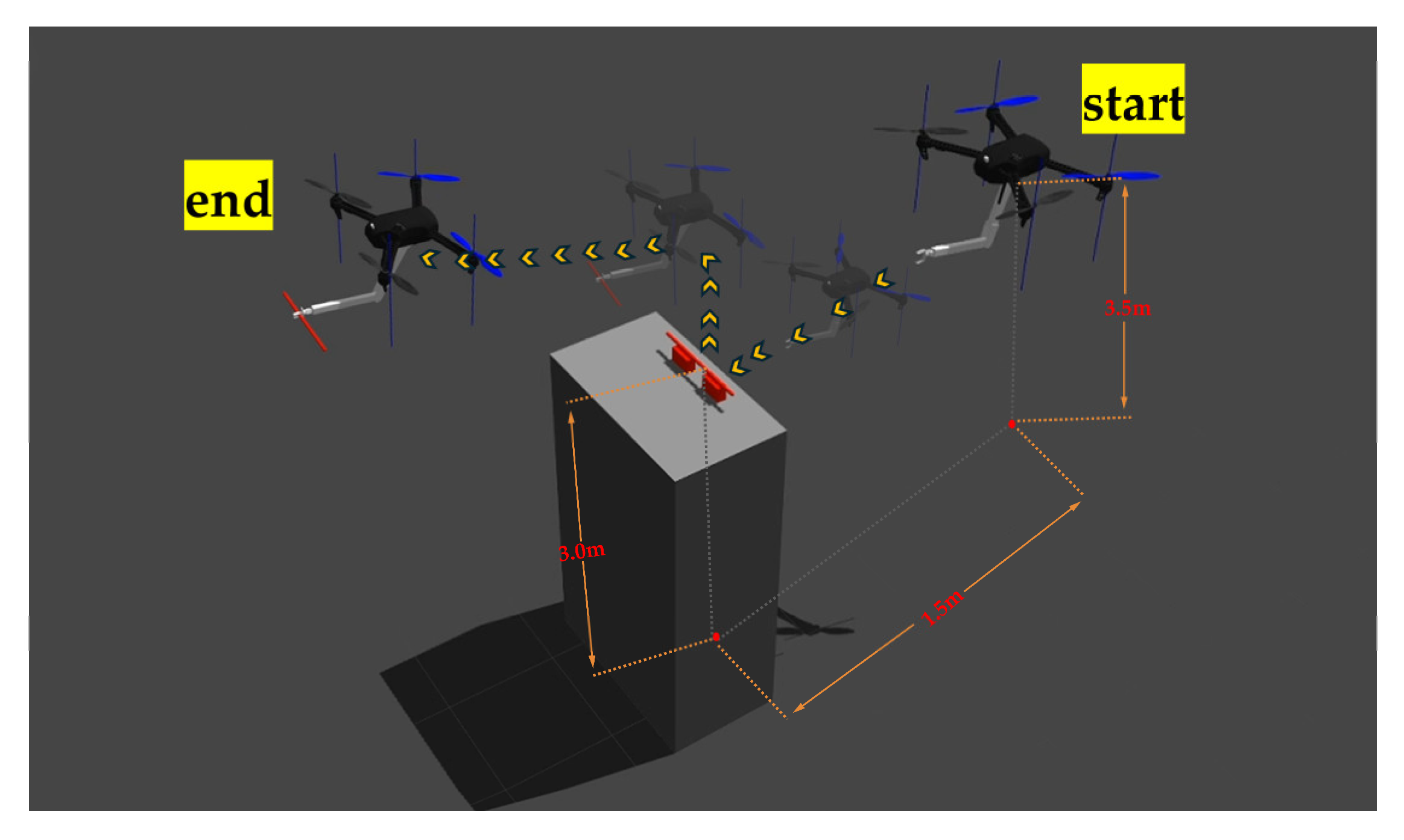

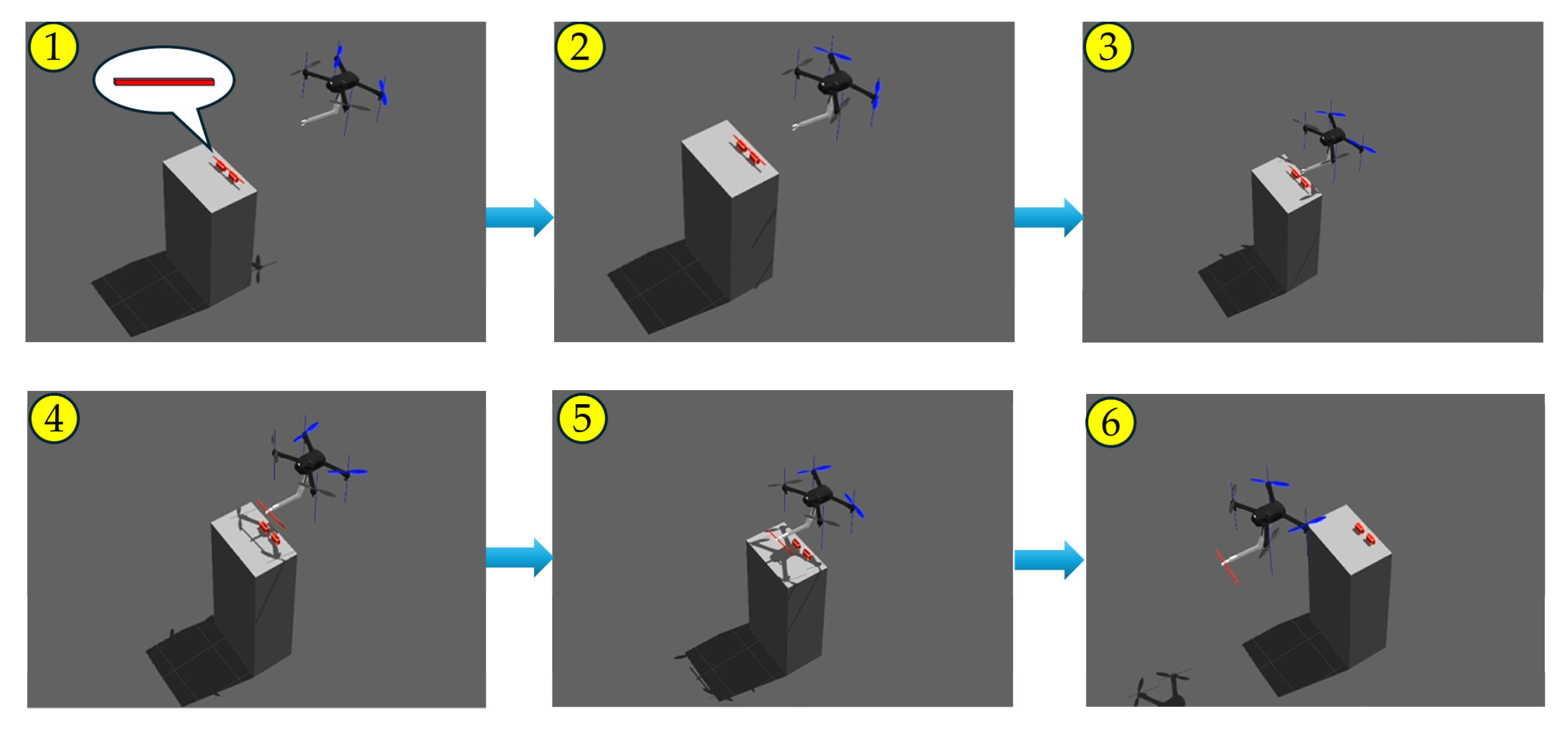

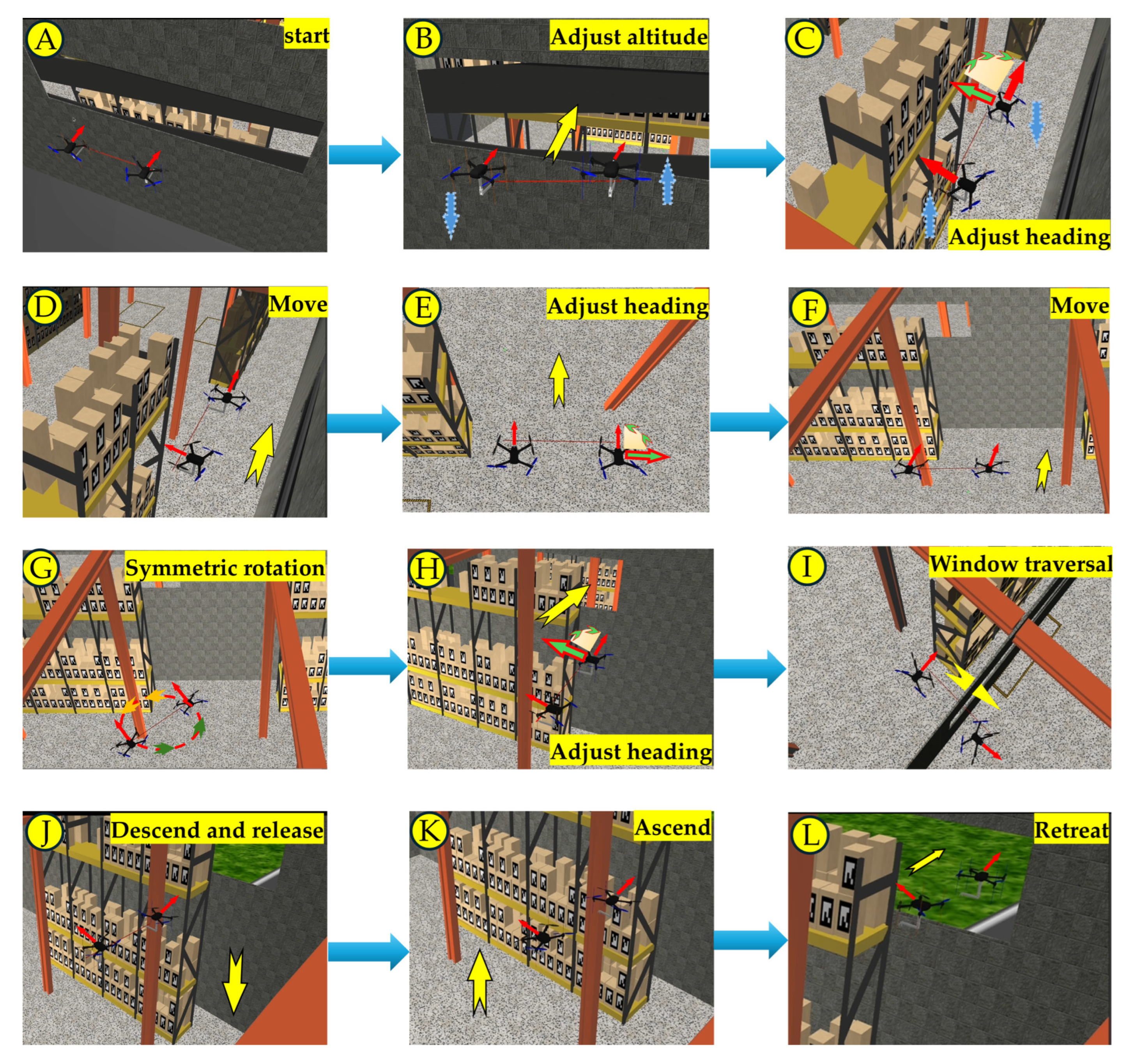

- Demonstrated the framework in single-UAV scenarios, where the operator controlled both the UAV flight and the manipulator joints using VR controllers to approach, align with, and grasp a target object in simulation.

- 3

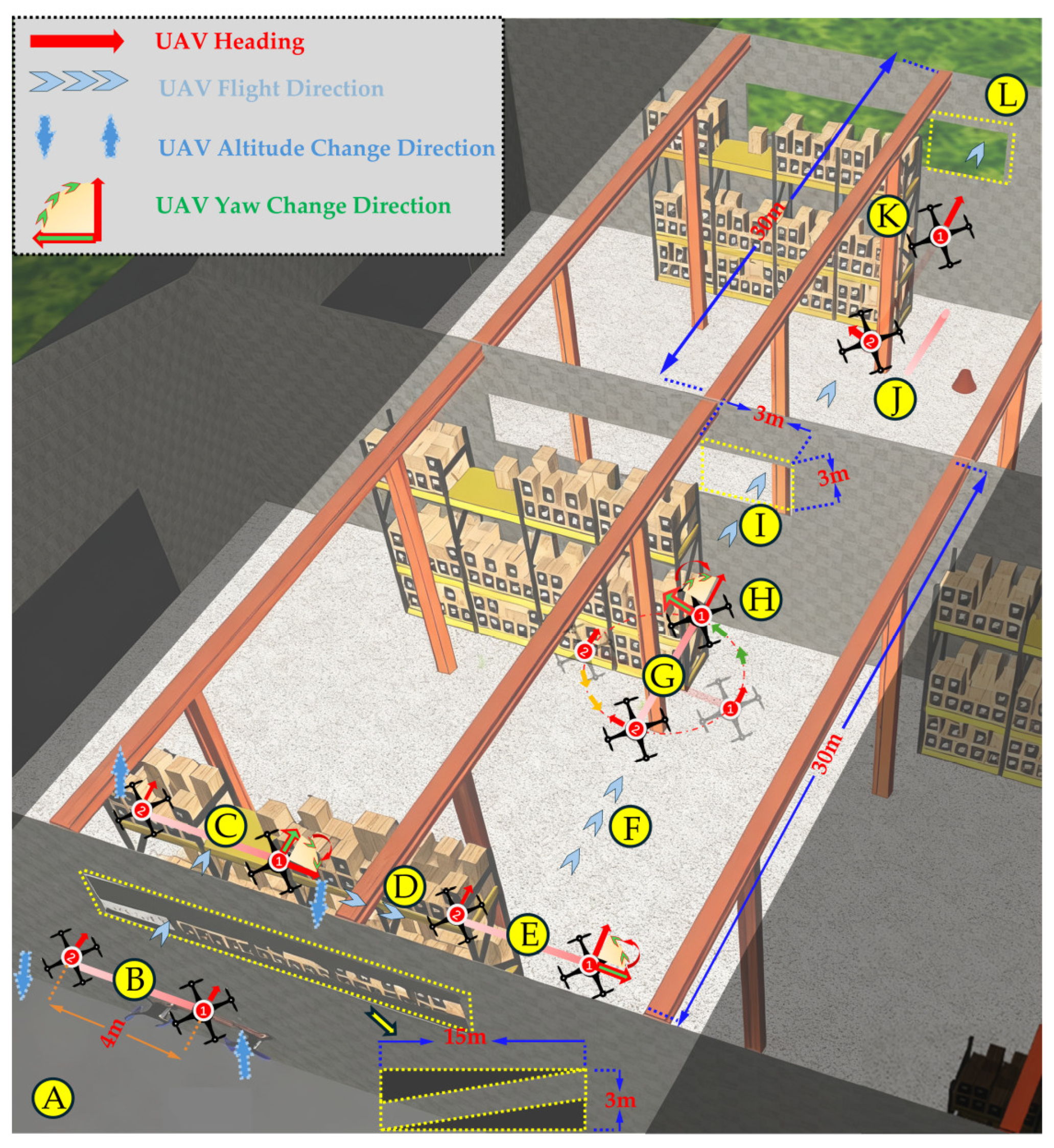

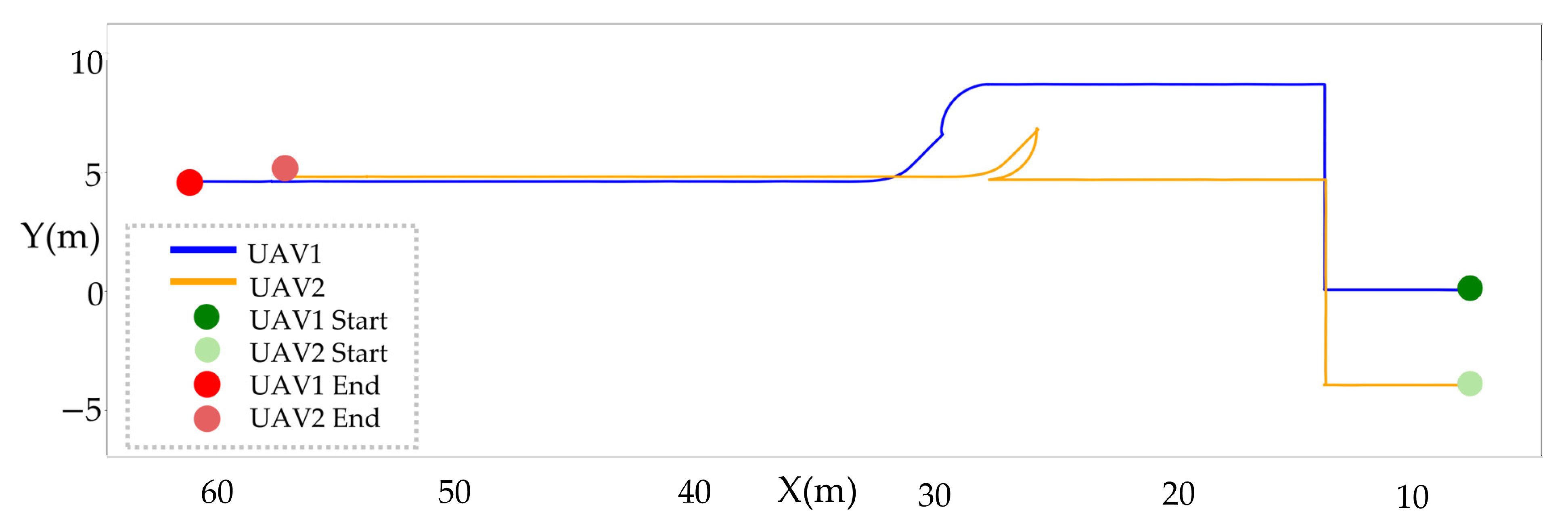

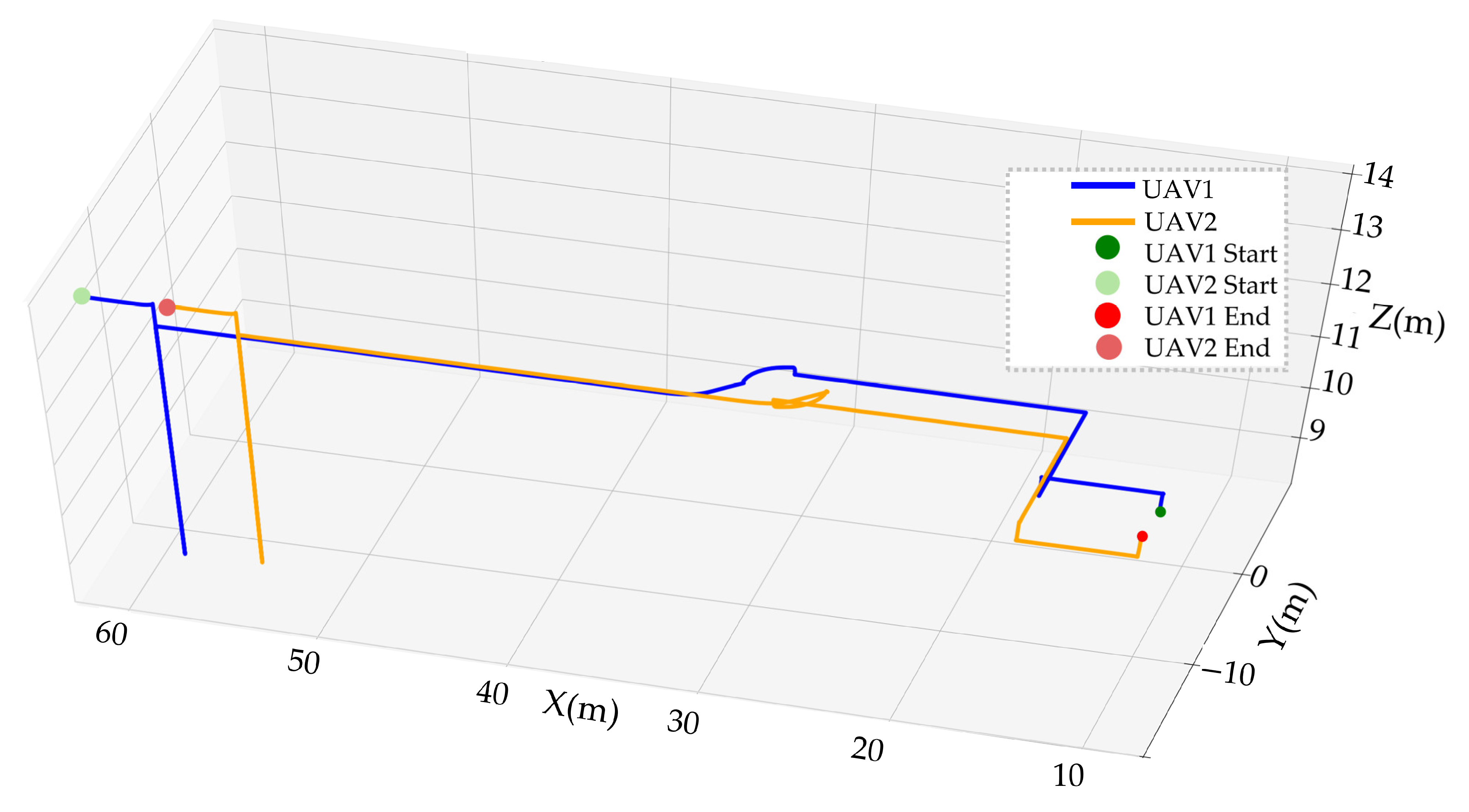

- Extended the framework to dual-UAV cooperative manipulation, leveraging the operator’s two-hand poses to directly map onto two UAV–manipulator units, thereby achieving coordinated payload transportation and obstacle traversal in simulation.

- 4

- Integrated the above components into a unified teleoperation architecture that connects human motion input, UAV dynamics, and manipulator control within the same framework. This system-level integration demonstrates how existing technologies can be cohesively combined to enable intuitive, synchronized, and scalable human–robot collaboration for aerial manipulation.

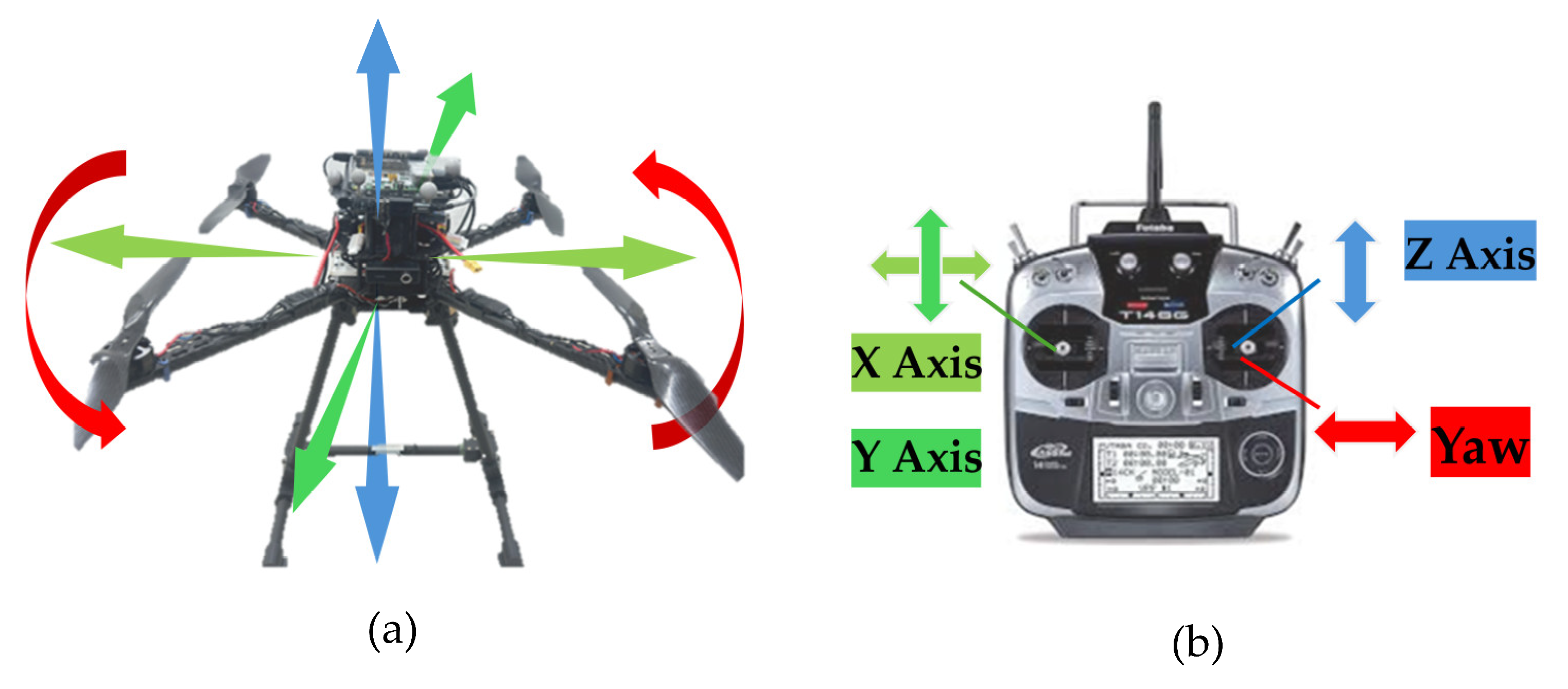

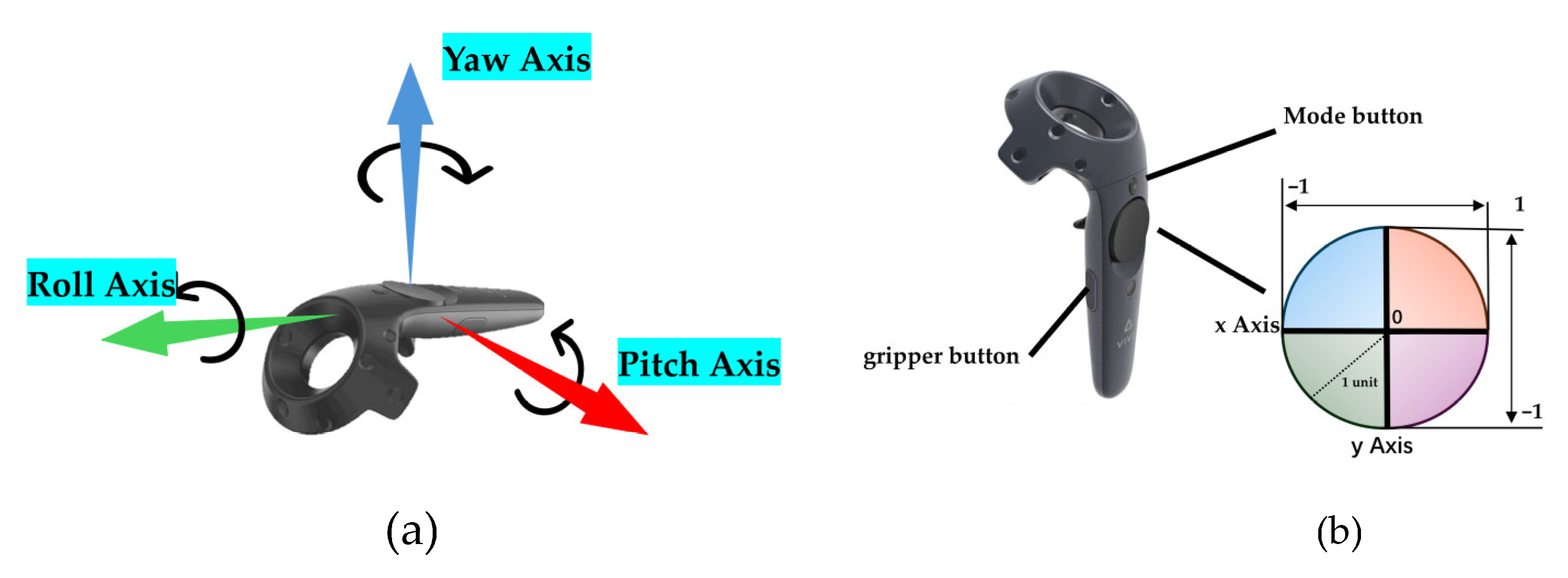

2. Control Methods Design

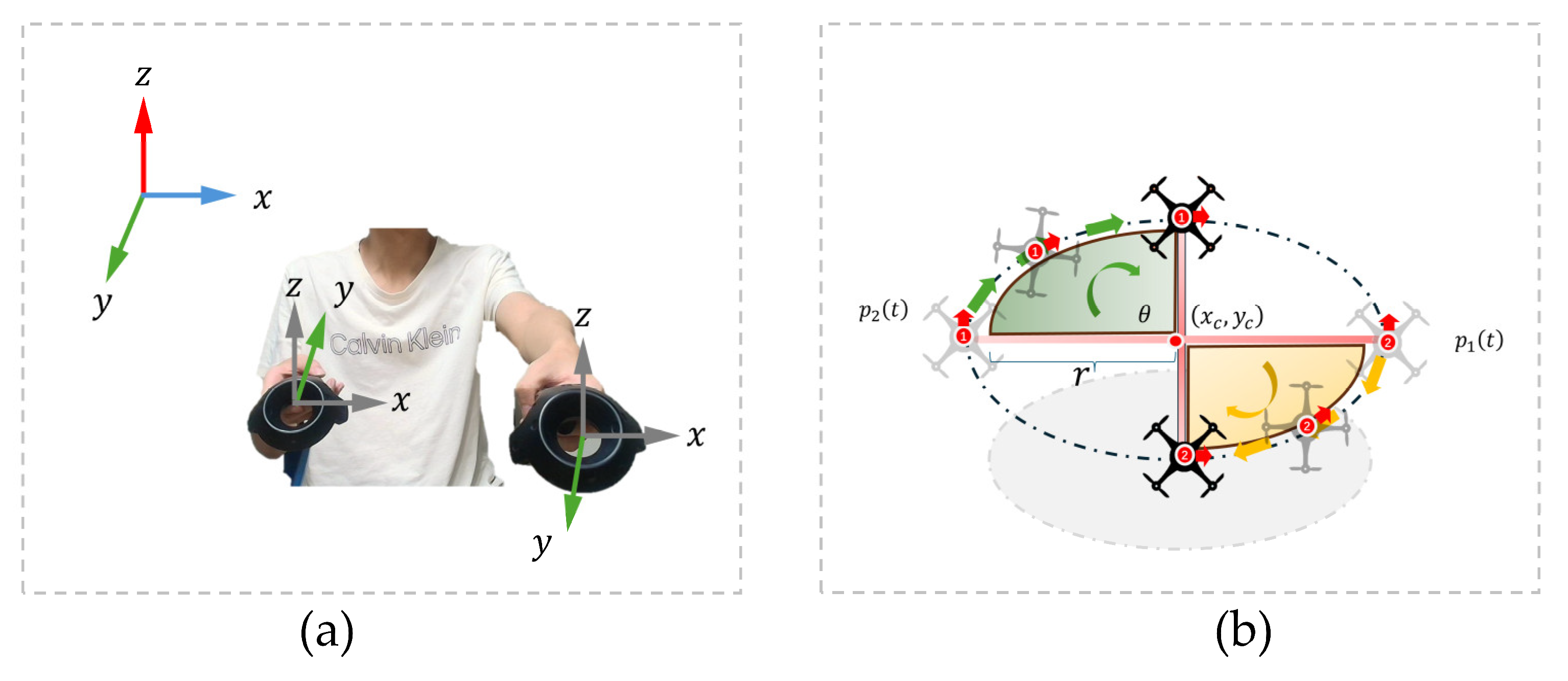

2.1. Single-UAV and Manipulator Control

| Algorithm 1 Tilt-Triggered UAV Altitude Control (Ascent/Descent) | |

Output: UAV motion command trigger 1: while system is running do 2: Read controller orientation via ROS topic then 5: Send ascending command to UAV then 7: Send descending command to UAV 8: else 9: Maintain UAVs in hover state 10: end while |

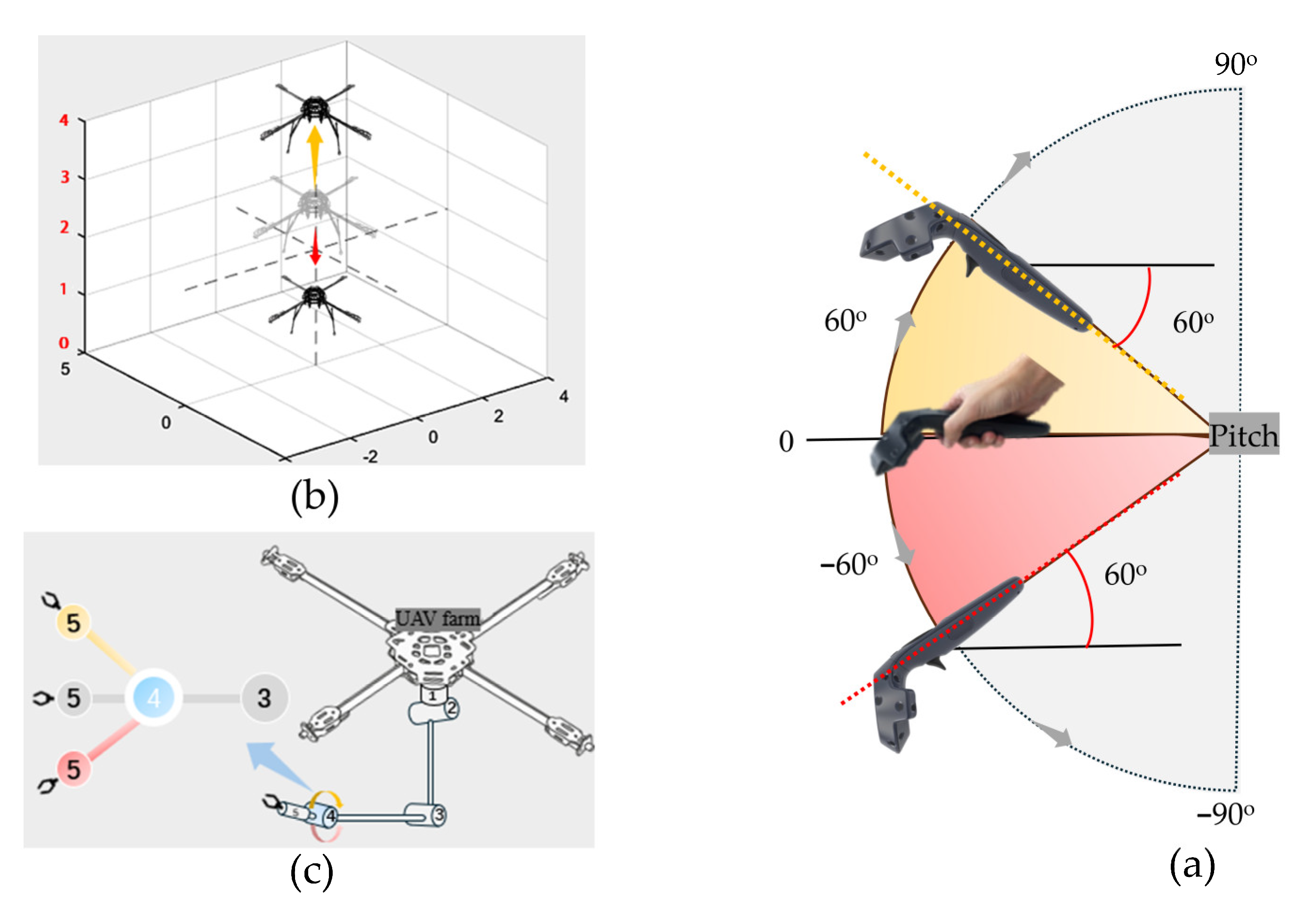

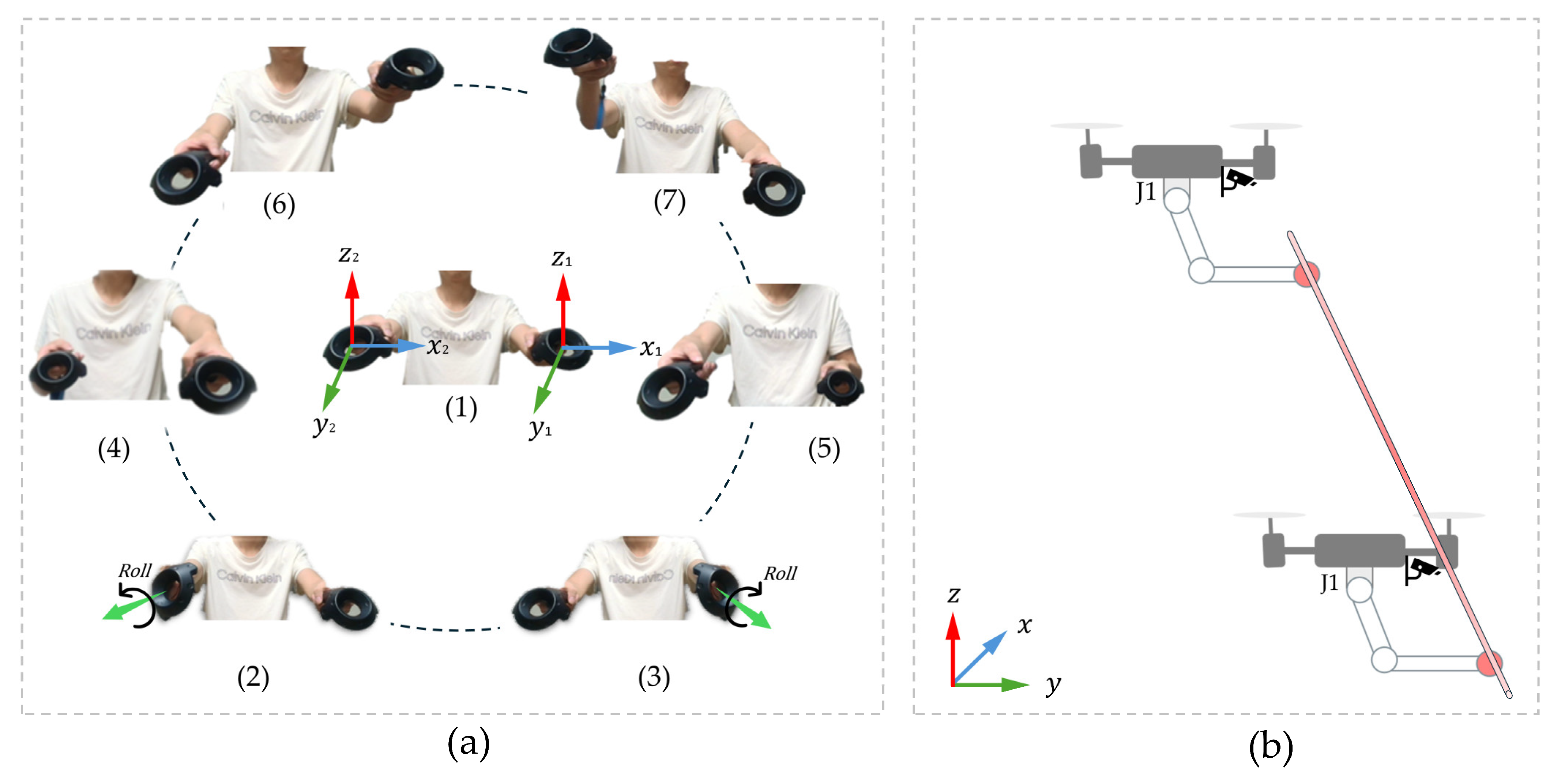

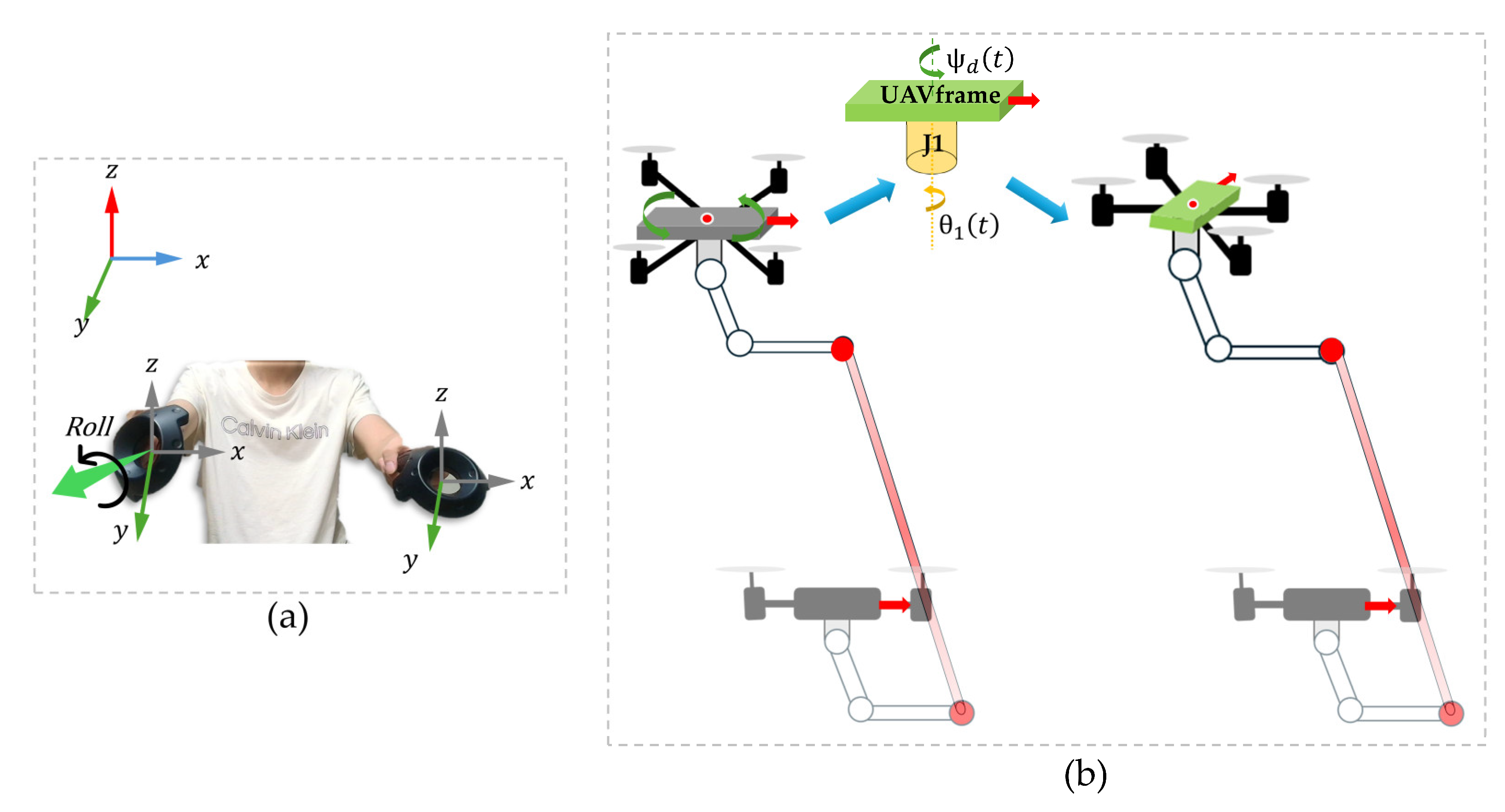

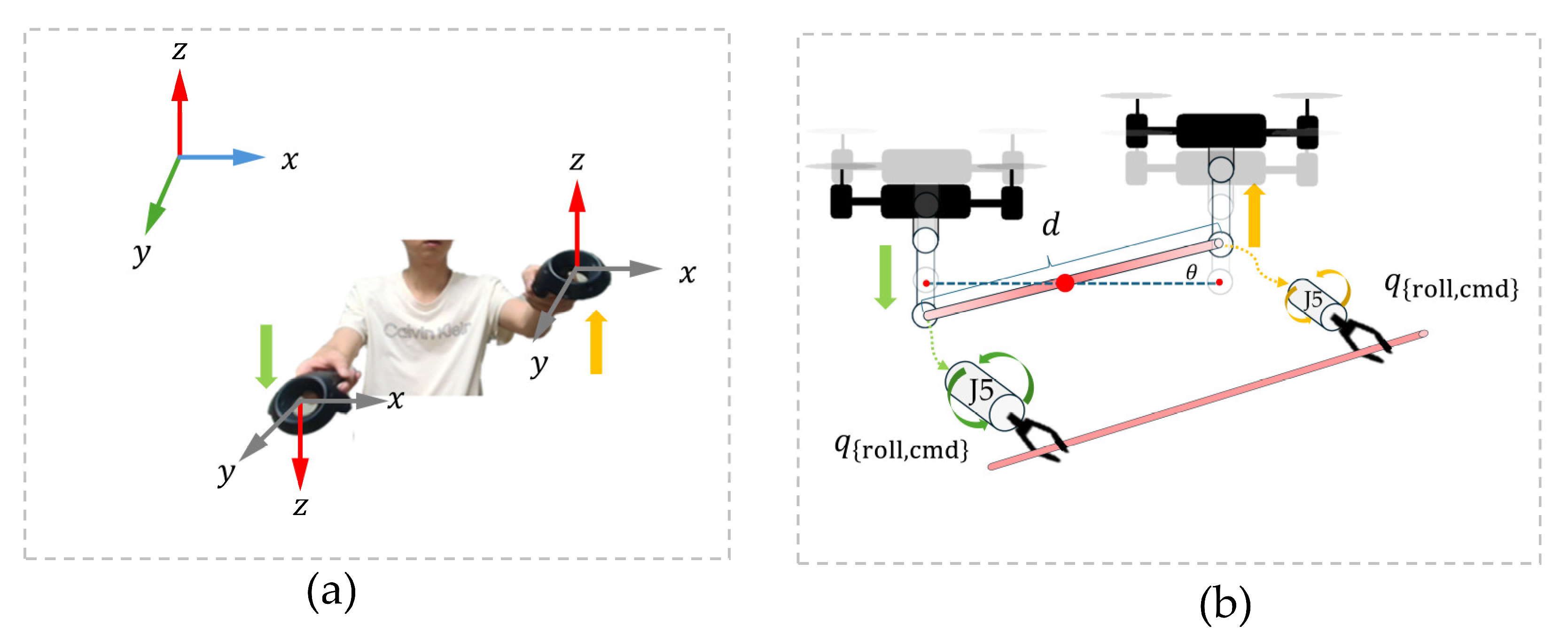

2.2. Dual-UAV Cooperative Control

| Algorithm 2 Dual-UAV Rotation Control via VR Input |

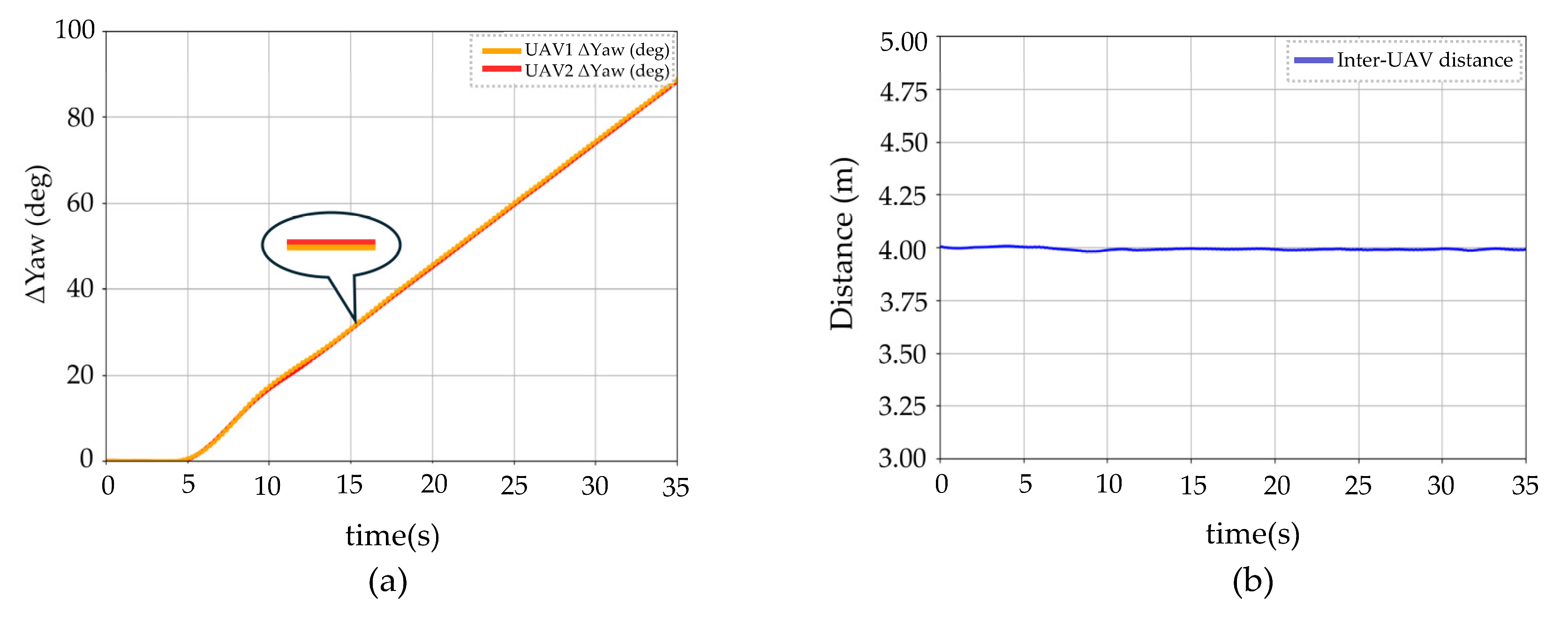

| Input: Positions of left and right VR controllers Output: Direction of circular maneuver (CW/CCW) 1: while system is running do 2: Read controller positions via ROS topic > 0.30 m then 5: Trigger counter-clockwise (CCW), set ω > 0 < −0.30 m then 7: Trigger clockwise (CW), set ω < 0 8: else 9: Maintain UAVs in hover state 10: end while |

| Algorithm 3 Yaw Compensation for UAV–Manipulator System via VR Input |

| Input: Rotations of left and right VR controllers Output: Yaw rotation of the UAV and inverse compensation of joint J1 1: while system is running do 2: Read controller rotations via ROS topic and left controller remains level then 7: else 8: Maintain UAVs in hover state 9: end while |

| Algorithm 4 Cooperative UAV Motion and Wrist Compensation via VR Input |

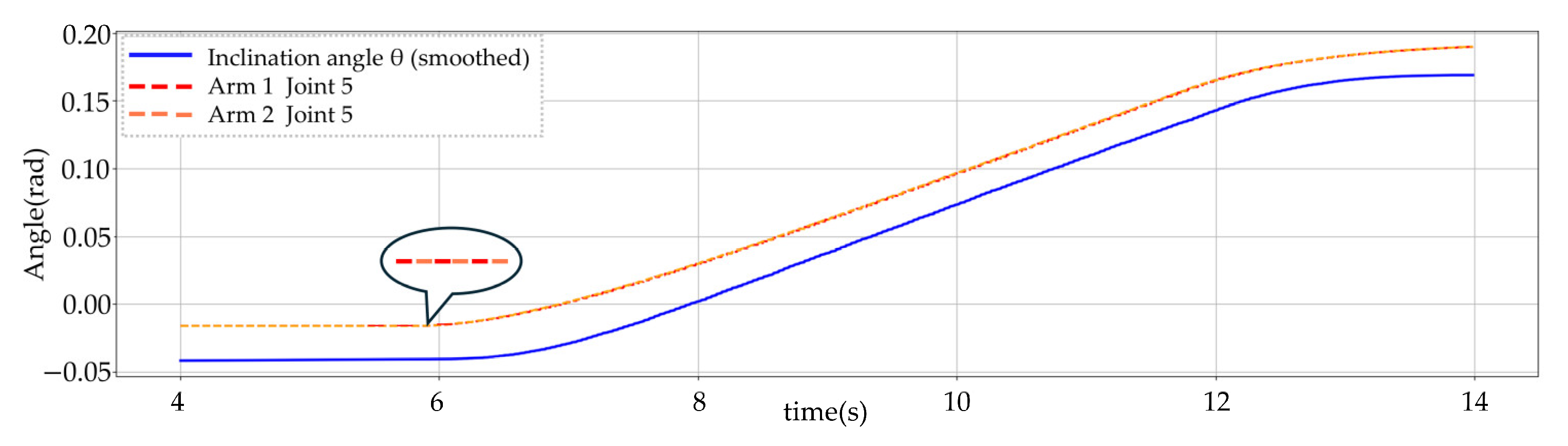

| Input: Positions of left and right VR controllers Output: Vertical motion of UAVs and J5 compensation angles 1: while system is running do 2: Read controller positions via ROS topic then then 6: Left UAV ascends; Right UAV descends. 7: else 8: Right UAV ascends; Left UAV descends. 9: Compute inclination angle 11: Set commanded wrist roll angles: 13: else 14: Maintain UAVs and manipulators in hover state. 15: end while |

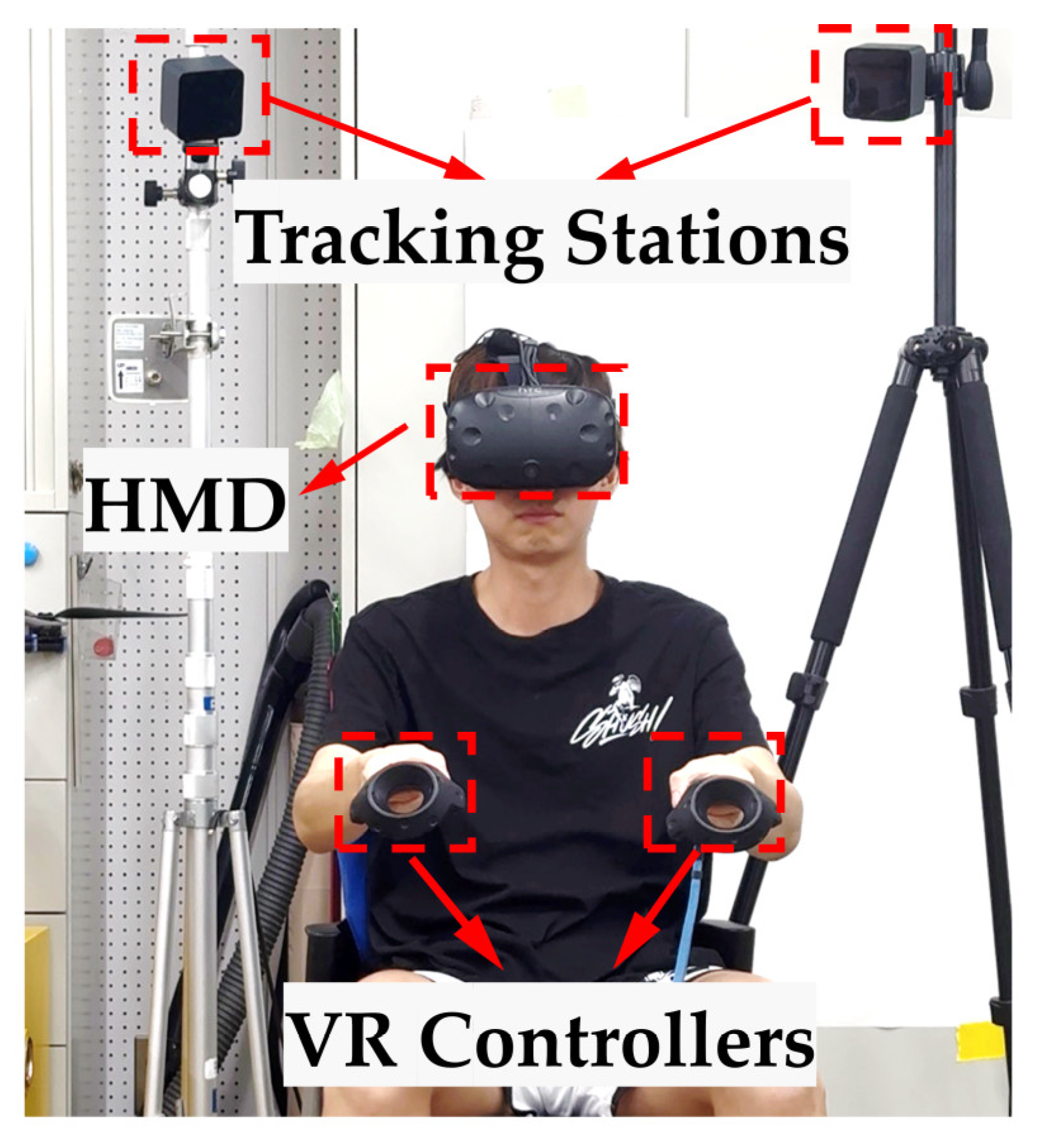

3. Experiments Using VR System

3.1. Experimental Setup

3.2. Experimental Tasks

3.3. Experimental Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DOF | Degrees of Freedom |

| ESC | Electronic Speed Controller |

| FCU | Flight Control Unit |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| HMD | Head-Mounted Display |

| ROS | Robot Operating System |

References

- Hassanalian, M.; Abdelkefi, A. Classifications, applications, and design challenges of drones: A review. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2017, 91, 99–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollero, A.; Tognon, M.; Suarez, A.; Lee, D.; Franchi, A. Past Present and Future of Aerial Robotic Manipulators. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2022, 38, 626–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael Gassner, T.C.; Scaramuzza, D. Dynamic Collaboration Without Communication: Vision-Based Cable-Suspended Load Transport with Two Quadrotors. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Singapore, 29 May–3 June 2017; pp. 5196–5202. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7989609 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Tanriverdi, V.; Jacob, R.J.K. Interacting with eye movements in virtual environments. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New York, NY, USA, 1–6 April 2000; pp. 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibert, L.E.; Jacob, R.J.K. Evaluation of eye gaze interaction. In Proceedings of the CHI00: Human Factors in Computing Systems, The Hague, The Netherlands, 1–6 April 2000; pp. 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Lu, X.; Shi, R.; Liang, H.N.; Dingler, T.; Velloso, E.; Goncalves, J. Gaze-Supported 3D Object Manipulation in Virtual Reality. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Yokohama, Japan, 8–13 May 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseer, F.; Ullah, G.; Siddiqui, M.A.; Khan, M.J.; Hong, K.-S.; Naseer, N. Deep learning-based unmanned aerial vehicle control with hand gesture and computer vision. In Proceedings of the 2022 13th Asian Control Conference (ASCC), Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 4–7 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- De Fazio, R.; Mastronardi, V.M.; Petruzzi, M.; De Vittorio, M.; Visconti, P. Human–Machine Interaction through Advanced Haptic Sensors: A Piezoelectric Sensory Glove with Edge Machine Learning for Gesture and Object Recognition. Future Internet 2023, 15, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, G.; Kwak, H.; Kim, D.H. Single-Handed Gesture Recognition with RGB Camera for Drone Motion Control. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Kim, K.-J.; Yu, K.-H. Implementation of a User-Friendly Drone Control Interface Using Hand Gestures and Vibrotactile Feedback. J. Inst. Control Robot. Syst. 2022, 28, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, D.; Sousa, M.; Raposo, A.; Jorge, J. Magic Carpet: Interaction Fidelity for Flying in VR. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2020, 26, 2793–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, S.-Y.; Kang, Y.-W.; Kim, Y.-G. Hand Gesture-based Wearable Human-Drone Interface for Intuitive Movement Control. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics (ICCE), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 11–13 January 2019; pp. 1–6. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8662106 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Lee, J.-W.; Yu, K.-H. Wearable Drone Controller: Machine Learning-Based Hand Gesture Recognition and Vibrotactile Feedback. Sensors 2023, 23, 2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, I.D.; Pavitra, A.R.R. Voice-controlled drones for smart city applications. In Sustainable Innovation for Industry 6.0; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 162–177. [Google Scholar]

- Darvish, K.; Penco, L.; Ramos, J.; Cisneros, R.; Pratt, J.; Yoshida, E.; Ivaldi, S.; Pucci, D. Teleoperation of Humanoid Robots: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2023, 39, 1706–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezza, D.; Andujar, M. The State-of-the-Art of Human–Drone Interaction: A Survey. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 167438–167454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Connor, A.M.; Marks, S. Mixed Interaction: Evaluating User Interactions for Object Manipulations in Virtual Space. J. Multimodal User Interfaces 2024, 18, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, J.; Aldabbagh, A. Gesture-controlled robotic arm utilizing opencv. In Proceedings of the 2021 3rd International Congress on Human-Computer Interaction, Optimization and Robotic Applications (HORA), Ankara, Turkey, 11–13 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, C.; Woeppel, A.B.; Clepper, G.M.; Gao, S.; Xu, S.; Rueschen, J.F.; Kruse, D.; Wu, W.; Tan, H.Z.; Low, T.; et al. Tactile and chemical sensing with haptic feedback for a telepresence explosive ordnance disposal robot. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2023, 39, 3368–3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafarra, S.; Pattacini, U.; Romualdi, G.; Rapetti, L.; Grieco, R.; Darvish, K.; Milani, G.; Valli, E.; Sorrentino, I.; Viceconte, P.M.; et al. icub3 Avatar System: Enabling Remote Fully Immersive Embodiment of Humanoid Robots. Sci. Robot. 2024, 9, eadh3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Kim, J.; Lee, H.; Jo, M.; Gong, D.; Ju, D.; Won, D.; Kim, S.; Oh, J.; Jang, H.; et al. A Whole-Body Integrated AVATAR System: Implementation of Telepresence with Intuitive Control and Immersive Feedback. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2023, 32, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Tecco, A.; Camardella, C.; Leonardis, D.; Loconsole, C.; Frisoli, A. Virtual Dashboard Design for Grasping Operations in Teleoperation Systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Metrology for eXtended Reality, Artificial Intelligence and Neural Engineering (MetroXRAINE), London, UK, 21–23 October 2024; pp. 994–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, M.; Lenz, C.; Rochow, A.; Schreiber, M.; Behnke, S. Nimbro Avatar: Interactive Immersive Telepresence with ForceFeedback Telemanipulation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Prague, Czech Republic, 27 September–1 October 2021; pp. 5312–5319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galarza, B.R.; Ayala, P.; Manzano, S.; Garcia, M.V. Virtual reality teleoperation system for mobile robot manipulation. Robotics 2023, 12, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjup, G.; Dwivedi, A.; Elangovan, N.; Liarokapis, M. An Intuitive, Affordances Oriented Telemanipulation Framework for a Dual Robot Arm Hand System: On the Execution of Bimanual Tasks. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Macau, China, 3–8 November 2019; pp. 3611–3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; McCarthy, Z.; Jowl, O.; Lee, D.; Chen, X.; Goldberg, K.; Abbeel, P. Deep imitation learning for complex manipulation tasks from virtual reality teleoperation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Brisbane, Australia, 21–25 May 2018; pp. 5628–5635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.J. Planning and Control for Collision-Free Cooperative Aerial Transportation. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2016, 15, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Shan, J.; Liu, H.H.T. Cooperative Transportation of a Flexible Payload Using Two Quadrotors. J. Guid. Control. Dyn. 2021, 44, 2099–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loianno, G.; Kumar, V. Cooperative Transportation using Small Quadrotors using Monocular Vision and Inertial Sensing. IEEE Robot. Autom. 2017, 3, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turco, E.; Castellani, C.; Bo, V.; Pacchierotti, C.; Prattichizzo, D.; Lisini Baldi, T. Reducing Cognitive Load in Teleoperating Swarms of Robots through a Data-Driven Shared Control Approach. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 14–18 October 2024; pp. 4731–4738. [Google Scholar]

- Phung, A.; Billings, G.; Daniele, A.F.; Walter, M.R.; Camilli, R. Enhancing Scientific Exploration of the Deep Sea through Shared Autonomy in Remote Manipulation. Sci. Robot. 2023, 8, eadi5227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Mass (kg) | 4.0 |

| Moment of Inertia (kg·m2) | diag (0.072, 0.135, 0.153) |

| Wheelbase (m) | 1.3 |

| Thrust Coefficient (N/rpm2) | 3.0 × 10−7 |

| Moment Coefficient (Nm/rpm2) | 4.0 × 10−8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Z.; Tomita, K.; Kamimura, A. VR-Based Teleoperation of UAV–Manipulator Systems: From Single-UAV Control to Dual-UAV Cooperative Manipulation. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11086. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011086

Yang Z, Tomita K, Kamimura A. VR-Based Teleoperation of UAV–Manipulator Systems: From Single-UAV Control to Dual-UAV Cooperative Manipulation. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(20):11086. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011086

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Zhaotong, Kohji Tomita, and Akiya Kamimura. 2025. "VR-Based Teleoperation of UAV–Manipulator Systems: From Single-UAV Control to Dual-UAV Cooperative Manipulation" Applied Sciences 15, no. 20: 11086. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011086

APA StyleYang, Z., Tomita, K., & Kamimura, A. (2025). VR-Based Teleoperation of UAV–Manipulator Systems: From Single-UAV Control to Dual-UAV Cooperative Manipulation. Applied Sciences, 15(20), 11086. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011086