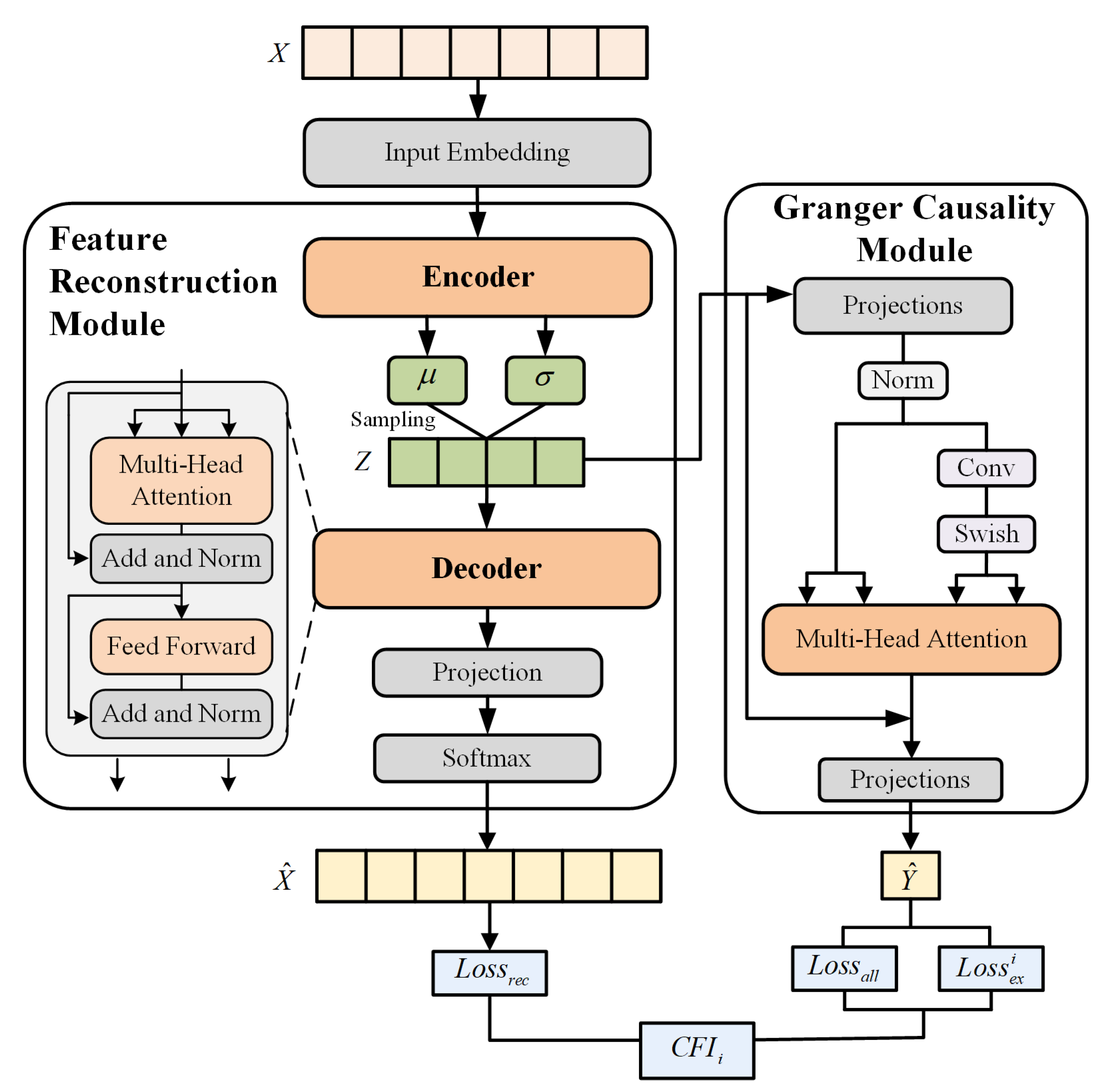

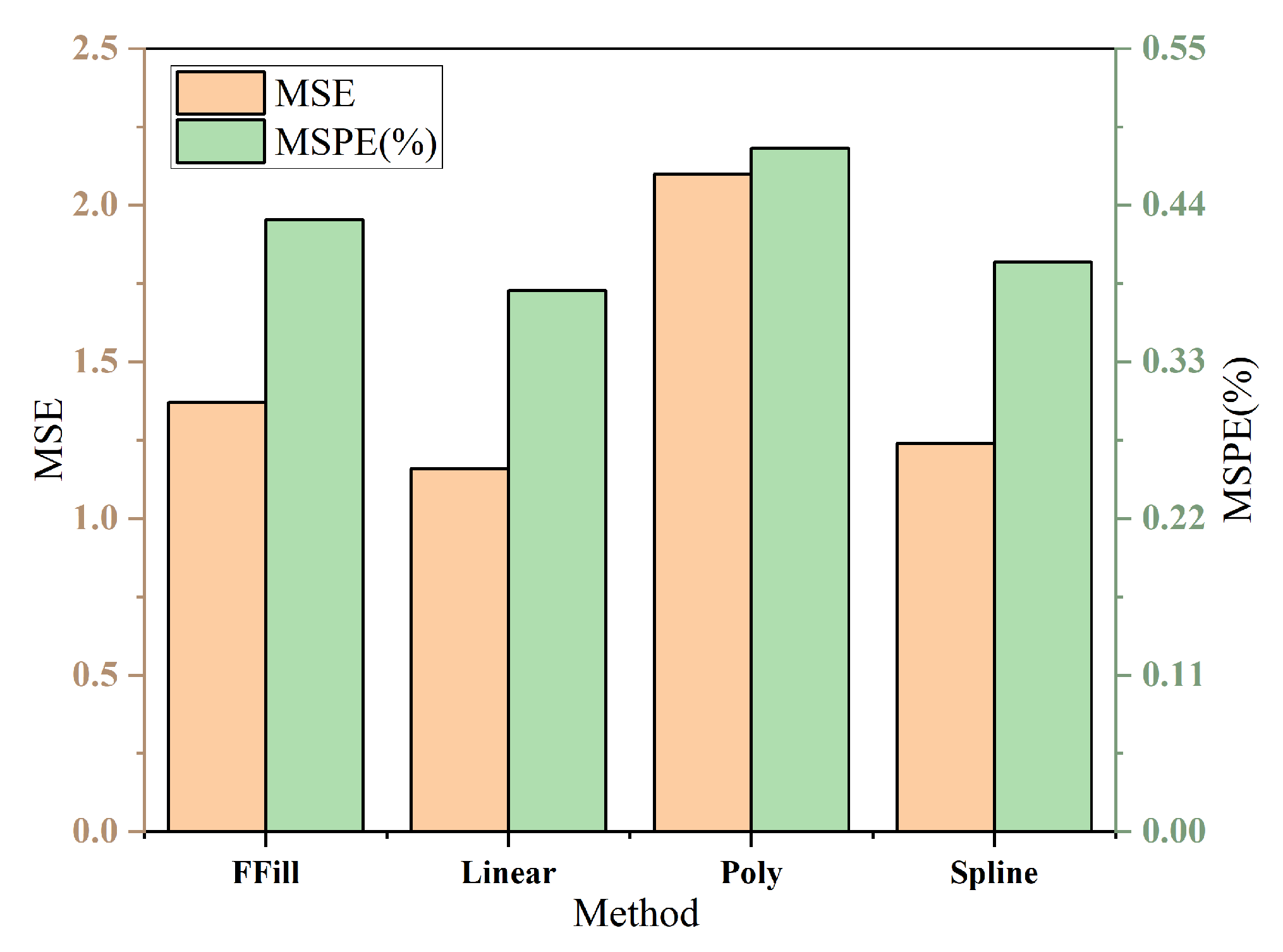

4.2. Experimental Design

4.2.1. Baselines

To rigorously evaluate the performance of the proposed DGCI model, we compare it against seven established baseline methods, which cover both traditional statistical approaches and recent deep learning-based temporal causal discovery models.

First, we include the following classical feature selection and statistical causality methods:

RreliefF [

50]: A correlation-based feature selection algorithm that estimates feature importance by measuring how well feature values distinguish between instances that are near each other.

Conditional Mutual Information (CMI) [

51]: Evaluates the conditional dependency between variables, ranking features based on their information contribution to the target.

Random Forests (RFs) [

52]: An ensemble-based feature selection method.

Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) [

53]: An L1-regularized regression-based feature selection approach.

Granger Causality Inference (Granger) [

20]: A classical linear test for temporal causality, serving as a direct conceptual predecessor to our nonlinear deep causal inference framework.

Second, to enrich the baselines with recent advances in temporal causal discovery, we further incorporate the following:

TCDF (Temporal Causal Discovery Framework) [

54]: An attention-based Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model designed for causal graph discovery from multivariate time series.

NGC (Neural Granger Causality) [

55]: A neural extension of Granger causality that captures nonlinear causal dependencies.

These baselines span from correlation-based feature ranking to modern deep learning approaches for causal discovery, providing a challenging and comprehensive benchmark to evaluate DGCI.

Direct evaluation of inferred Granger causal relationships is constrained by the lack of ground-truth causal graphs for real-world time series. To address this limitation, we adopt a task-oriented downstream forecasting paradigm. Specifically, each baseline method and our proposed model are used to identify feature subsets deemed most relevant or causal for the target time series. These subsets are then employed as inputs to train standard downstream prediction models, with accuracy on a hold-out test set serving as the primary performance metric. To further assess robustness and ensure that the proposed model’s effectiveness is not tied to a particular architecture, we evaluate the selected features using six benchmark multivariate time-series forecasting models. To assess the downstream utility of selected features, all methods are tested under a unified forecasting setting. Specifically, the selected top-5 features are used as inputs to train 6 standard multivariate, The time-series predictors can be categorized into RNN-based models, CNN-based models, and Transformer-based models, including the following models:

LSTM [

56]: A representative recurrent model that captures long-term temporal dependencies via gated mechanisms.

TCN [

57]: A CNN-based model designed to efficiently capture local and hierarchical temporal patterns.

Autoformer [

58]: A Transformer-based model that incorporates time-series decomposition to enhance trend and seasonality modeling.

ETSformer [

59]: A Transformer variant that integrates exponential smoothing and decomposition for improved temporal representation.

iTransformer [

60]: A Transformer-based model reformulated for efficient long-sequence forecasting through input embedding inversion.

CARD [

61]: A compact and efficient Transformer framework optimized for robust representation learning in long-horizon forecasting tasks.

This design ensures that DGCI’s effectiveness is evaluated not only in causal discovery but also in terms of generalization across diverse forecasting architectures.

4.2.2. Metrics

In the predictive modeling framework, this study employs Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Mean Squared Percentage Error (MSPE) [

62] as primary loss functions to quantify absolute and relative prediction errors between observed values

and predicted values

. The MSE metric evaluates absolute error magnitude by computing the average squared deviation,

where

N represents the number of samples. A smaller MSE value indicates higher predictive accuracy and lower overall deviation.

To mitigate sensitivity to price volatility and enhance robustness against outliers, MSPE measures relative error through normalized squared deviations,

where the multiplication by 100 converts the result to percentage terms for improved interpretability. MSPE is particularly valuable in time series forecasting as it provides scale-invariant performance assessment, allowing for meaningful comparisons across different price levels and time periods. The percentage-based nature of MSPE enables direct interpretation of model performance regardless of the underlying price magnitude, making it an essential complement to MSE for comprehensive model evaluation. Together, MSE captures absolute accuracy while MSPE assesses relative performance, providing a balanced evaluation framework that addresses both the precision and proportional accuracy of our forecasting model.

To provide a comprehensive comparison, we report the Average Improvement Rate (AVG IR) of DGCI over each baseline method. AVG IR is introduced to provide a quantitative assessment of the relative advantage of the proposed DGCI method over each baseline feature selection approach. Specifically, IR measures the percentage reduction in error achieved by DGCI with respect to a given baseline, thereby indicating the degree of performance enhancement. For a given performance metric (e.g., MSE or MSPE), let

and

denote the metric values obtained by the baseline and DGCI, respectively, on forecasting model (

k)

. We first compute the mean performance of each method across the (

K) forecasting architectures

The average IR (AVG IR) for that metric is then defined as the percentage reduction in the metric achieved by DGCI relative to the baseline

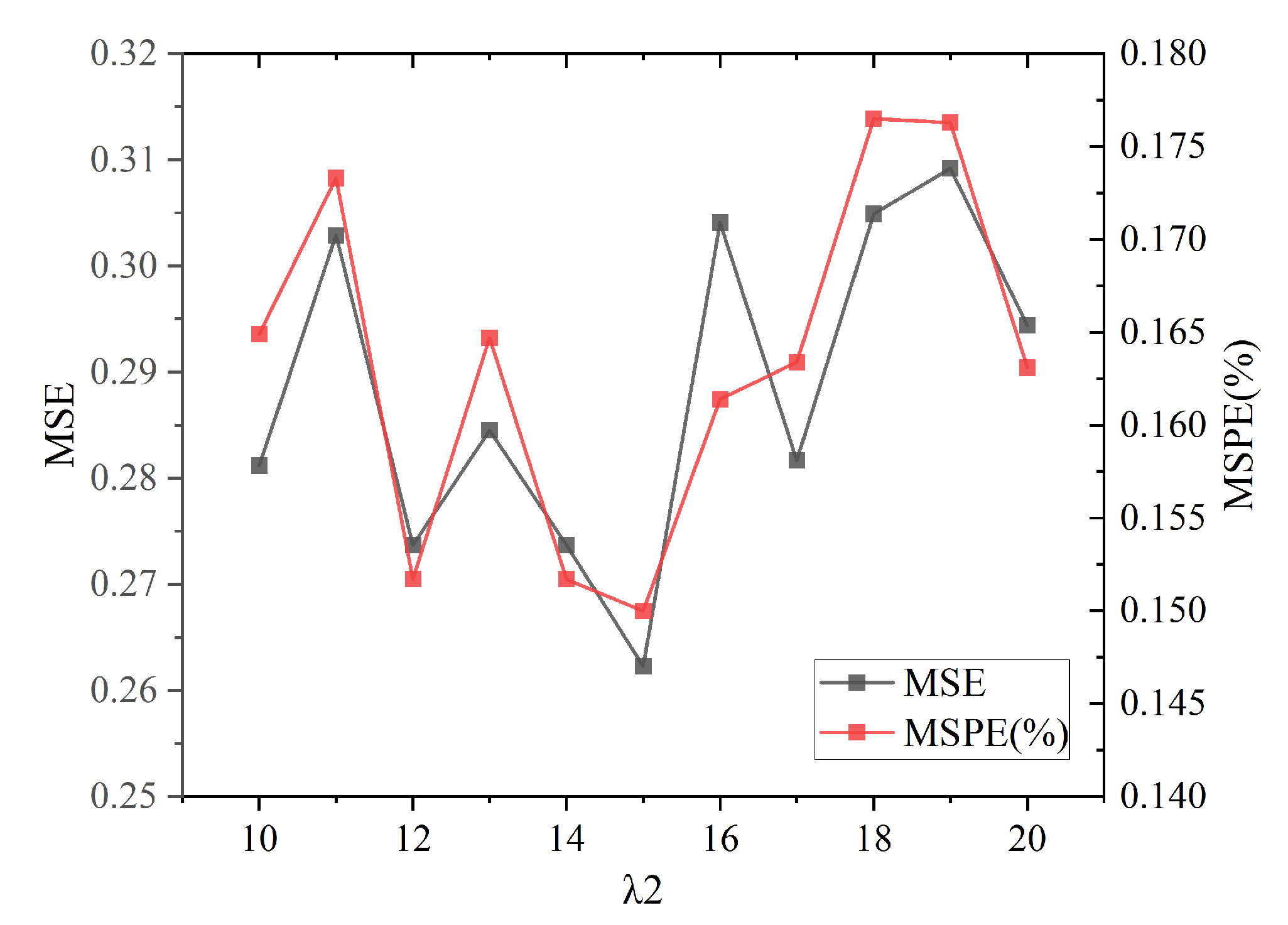

4.2.3. Parameters Setting

To ensure fair comparisons, we choose a fixed data split ratio for each dataset chronologically, i.e., 7:1:2, for training, validation and testing. Model training utilizes the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001, conducted over a maximum of 20 epochs. An early stopping mechanism halts training if validation loss fails to improve for 10 consecutive epochs. A fixed look-back window length of time steps is adopted across all models to balance historical context sufficiency with pattern capture efficiency. The prediction horizon is initially set to one step. During testing, model outputs are rescaled to the original data distribution prior to metric computation. To ensure statistical reliability, all experiments are executed for 10 independent runs, with reported results representing the average metric values.

The architectural hyperparameters for our Transformer-based models were systematically determined through random search optimization within theoretically justified ranges. Specifically, the embedding dimension was selected from the range [32, 64, 128, 256, 512] through random search, with 128 ultimately chosen based on optimal validation performance. This range encompasses the commonly used embedding dimensions in time series forecasting literature, balancing model expressiveness with computational efficiency. The number of attention heads was constrained to values [4, 8, 12, 16] that ensure is divisible by the number of heads (a requirement for multi-head attention), with eight heads selected through random search optimization. The feed-forward network hidden dimension was searched within the range [128, 256, 512, 1024], with 512 ultimately selected for optimal performance. This systematic hyperparameter optimization approach ensures that our architectural choices are data-driven rather than arbitrary, providing a robust foundation for model comparison and evaluation. To rigorously assess robustness across varying forecast horizons, comparative evaluations between the DGCI model and baseline models iTransformer are extended to prediction horizons of steps, while maintaining the look-back window.

4.3. Experimental Results and Analysis

To comprehensively evaluate the robustness and generalization ability of the proposed DGCI model, we conduct experiments comparing DGCI with seven baseline feature selection and causal discovery methods (RreliefF, CMI, RFs, LASSO, Granger, TCDF, and NGC) across six representative time-series predictors: LSTM, TCN, Autoformer, iTransformer, CARD, and ETSformer. Each feature selection method identifies the top five predictive features, which are then used as inputs for all forecasting models under a one-step prediction horizon. The quantitative results for MSE and MSPE are summarized in

Table 2 and

Table 3, respectively, with the best results in bold. The choice of five features is based on a sensitivity analysis conducted with the best-performing predictor, iTransformer. We compared different feature set sizes (

) and found that using five features yields the lowest prediction errors (

Table 4). This configuration provides the best trade-off between model complexity and accuracy, avoiding overfitting or noise introduced by excessive features.

The DGCI model consistently achieved the lowest MSE and MSPE values across nearly all predictors, which demonstrates both its strong absolute accuracy and stable relative performance. DGCI recorded the best overall MSE of 0.8673 (LSTM), 0.6001 (TCN), 0.6332 (Autoformer), 0.2623 (iTransformer), 0.5075 (CARD), and 0.7142 (ETSformer). The corresponding MSPE values, 0.30, 0.18, 0.19, 0.15, 0.17, and 0.21, further confirm its superior predictive accuracy and proportional consistency.

The recently developed neural causal discovery baselines, TCDF and NGC, demonstrate considerable improvement over traditional correlation-based and linear causality approaches. For instance, NGC achieves competitive MSE values under TCN (0.5830) and Autoformer (0.6121), which outperform all classical baselines and closely approach the DGCI performance. Similarly, TCDF produces competitive results with MSEs of 0.6403 under TCN and 0.6712 under Autoformer, reflecting the benefit of attention-based temporal causality modeling. Nevertheless, DGCI consistently surpasses both TCDF and NGC across all forecasting architectures, which validates its enhanced capacity to capture nonlinear and dynamic causal dependencies in multivariate temporal data.

The AVG IR quantifies DGCI’s relative performance gain over the baselines. For MSE, DGCI achieves an average reduction ranging from 17.59% (compared with RreliefF) to 39.22% (compared with LASSO). When compared with the neural causal baselines, DGCI still achieves an additional 5.03% improvement over NGC and 11.28% over TCDF. These results indicate that the causal structure learning component of DGCI complements rather than overlaps with neural Granger-type frameworks. For MSPE, DGCI attains relative improvements from 19.51% (over TCDF) to 54.90% (over Granger). Even when compared with NGC, which already exhibits strong performance, DGCI achieves a further 9.82% gain. This consistent improvement confirms that DGCI maintains high proportional accuracy even under varying scales of temporal fluctuations.

DGCI also exhibits strong generalization ability across different forecasting architectures, including RNN (LSTM), CNN (TCN), and Transformer-based models (Autoformer, iTransformer, CARD, and ETSformer). For LSTM and TCN, DGCI achieves the lowest MSE (0.8673 and 0.6001) and MSPE (0.30 and 0.18), confirming its adaptability to models that focus on local temporal dependencies. For Transformer-based predictors, DGCI maintains robust and stable performance, with best-in-class results under iTransformer (MSE 0.2623, MSPE 0.15), CARD (MSE 0.5075, MSPE 0.17), and ETSformer (MSE 0.7142, MSPE 0.21). These findings indicate that the causal representations learned by DGCI are model-agnostic and generalize effectively across diverse forecasting architectures. In addition, DGCI achieves balanced performance between MSE and MSPE, while several baselines, such as LASSO and RFs, exhibit asymmetric behavior across metrics. This observation implies that DGCI not only improves predictive accuracy but also enhances proportional consistency by extracting causal features that remain robust across varying magnitudes of temporal variation.

Further comparison across baseline categories provides additional insights. Correlation-based methods such as RreliefF and CMI exhibit moderate yet stable performance, although they are limited in modeling higher-order temporal dependencies. Regularization-based feature selection methods such as LASSO provide strong sparsity control but lack adaptability to nonlinear and dynamic data patterns. Ensemble-based approaches, exemplified by RFs, offer acceptable accuracy but remain restricted by static feature interaction modeling. Statistical causality methods such as Granger provide interpretable linear causality insights but are inadequate for nonlinear temporal systems. Neural causal discovery models, including TCDF and NGC, represent a significant improvement by learning nonlinear temporal dependencies; however, DGCI further extends this capability by introducing dynamic graph-based causal structure refinement and adaptive information propagation mechanisms, resulting in consistently superior predictive performance.

In summary, the experimental results establish DGCI as a robust and generalizable causal feature selection framework. It consistently achieves the best MSE and MSPE performance across all predictors and outperforms both classical statistical and advanced deep learning baselines. The consistent improvement over TCDF and NGC highlights the effectiveness of integrating graph-based causal structure modeling with spatiotemporal representation learning. The superior AVG IR values confirm that DGCI achieves not only absolute error minimization but also proportional stability across diverse forecasting models, demonstrating its theoretical soundness and practical applicability for real-world time series forecasting tasks.

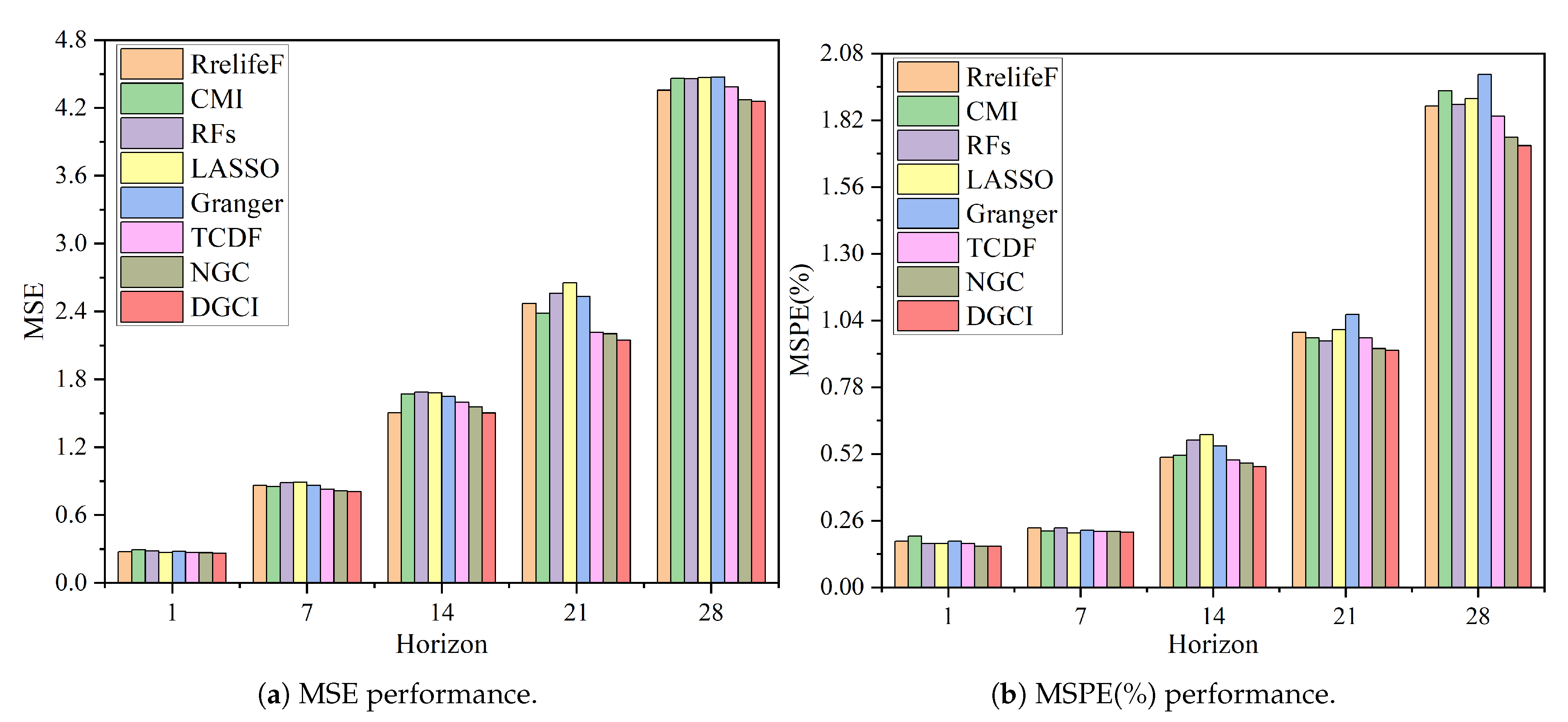

4.4. Multi-Horizon Forecasting Stability

Figure 3 illustrates the performance comparison of all models under varying forecasting horizons, evaluated by MSE and MSPE. Overall, the proposed DGCI model consistently achieves the lowest prediction errors across nearly all horizons, confirming its robustness and adaptability in multi-horizon forecasting. The error growth of DGCI with increasing horizon length is significantly slower than that of the baseline methods, demonstrating its enhanced capacity to capture both short-term and long-term dependencies through dynamic causal interaction learning.

In short-term forecasting (one- and seven-step horizons), DGCI exhibits highly competitive accuracy, performing comparably to or better than other causal discovery models such as NGC and TCDF. The differences among models are relatively minor in this range, as short-term predictions mainly rely on recent temporal information where traditional and deep causal models still retain comparable expressiveness. Nevertheless, DGCI maintains the lowest overall loss, indicating that even in simple temporal regimes, its graph-based causal feature selection contributes to more stable predictions.

As the forecasting horizon extends to medium- and long-term ranges (14-, 21-, and 28-step), the advantages of DGCI become more pronounced. Competing methods show a clear degradation trend due to accumulated temporal uncertainty and weakened feature relevance, whereas DGCI exhibits smoother performance deterioration and retains superior forecasting accuracy. This sustained stability highlights DGCI’s ability to capture persistent causal structures and adaptively refine feature dependencies across time.

Overall, these observations confirm that DGCI not only enhances predictive accuracy but also ensures long-horizon stability through causal inference, demonstrating clear advantages over both conventional feature selection methods and recent deep temporal causality models such as TCDF and NGC.

4.6. Key Feature Interpretation Analysis

The proposed DGCI model calculates the CFI values for 16 features, ranking them to identify core features.

Table 7 presents the CFI values to validate each feature’s information complexity and causal effects.

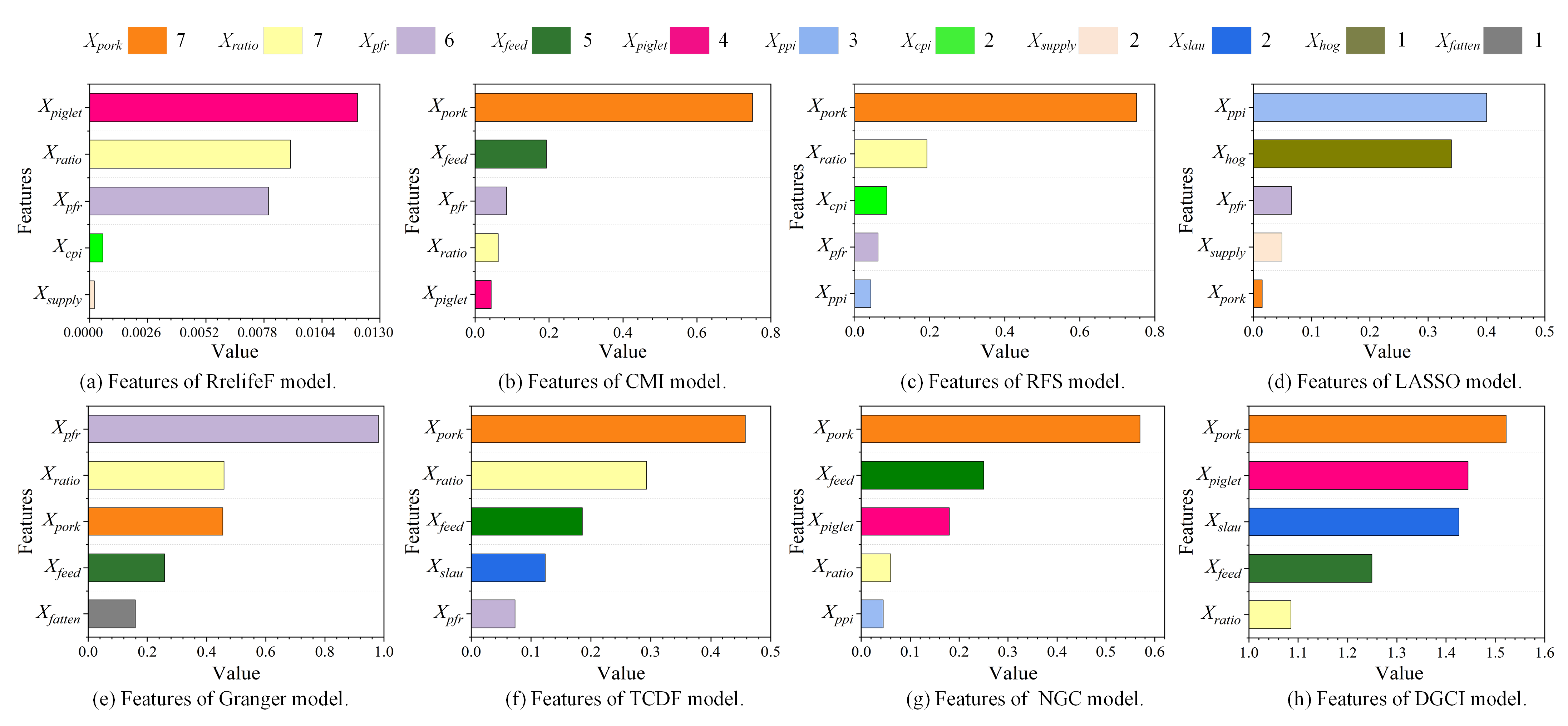

Figure 5 visually compares the top five features selected by the proposed DGCI model and the other five baseline models, intuitively revealing the feature selection reliability of DGCI model.

In

Table 7, the DGCI computes CFI values, along with reconstruction loss (

) and Granger loss (

), which are presented for all 16 features. CFI is a weighted sum of

and

, with weights

and

from prior sensitivity analysis. High

features (e.g., feed price

of 8.2986, hog inventory

of 6.9089) show significant information loss in compressed representation, implying complex nonlinear patterns between multivariate. High

features (e.g., pork price

of 0.6636 and piglet price

of 0.5552) have a strong causal impact on hog price forecasting, working through supply-demand, cost transmission, and market linkages. The CFI metric synthetically integrates these informational and causal dimensions, with the highest values identifying pork price (

), piglet price (

), slaughter volume (

), feed price (

), and national pig-feed ratio (

) as paramount features.

functions as a terminal price signal directly driving hog pricing,

serves as a leading cost indicator presaging price trends,

dictates immediate supply-demand balance,

underpins cost structure fundamentals, while

reflects breeder profitability thresholds that govern production cycles.

Figure 5 illustrates the top five features selected by all models, providing an overall view of the feature importance distribution. As shown, several features are consistently selected across different models, indicating their strong relevance to hog price dynamics. Specifically,

(pork price) and

(national pig-feed ratio) are the most frequently chosen features, each identified by seven models. Other highly ranked features include

(pork-feed ratio, selected by six models),

(feed price, selected by five models), and

(piglet price, selected by four models). Notably, the DGCI model identifies

,

,

(hog slaughter volume),

, and

as its top five features (

Figure 5h). These features largely overlap with those frequently selected by other models, suggesting that the DGCI framework captures both domain-consistent and model-robust predictors. This consistency further validates the effectiveness and interpretability of the proposed feature selection mechanism.

The DGCI model identifies pork price as the most critical determinant, with the highest CFI value (1.5216), underscoring its central role as a causal signal in price transmission. Although hog price and pork price are highly correlated, they capture different positions in the supply chain. Hog price reflects the upstream production market, while pork price represents the terminal consumer market. Pork price directly responds to shifts in consumer demand and retail dynamics, which in turn feed back to influence slaughter decisions and production adjustments in the hog sector. The fluctuations in pork price not only guide consumer purchasing behavior but also shape the production side by affecting slaughter plans and farming scale. The pork price can serve as a key monitoring indicator for government interventions, including the release of pork reserves and the implementation of price stabilization measures. Fluctuations in pork prices convey essential signals throughout the distribution and retail chains, facilitating coordinated adjustments across the entire industry value chain.

Piglet cost is a critical input in the farming process, directly affecting production costs and profit margins. When piglet costs rise, farming expenses increase, potentially leading to reduced hog supply and higher hog prices. The relatively high CFI value highlights the significant influence of piglet cost on the supply side and its importance in shaping market price formation. Piglet costs directly determine the input-output relationship in the breeding process and are closely related to feed utilization efficiency and farming profitability, which affects the sustainable use of agricultural resources. The piglet cost can indirectly influence supply elasticity through targeted policy instruments such as production subsidies for hog farming, feed price adjustments, and financial support for breeding expenditures.

Slaughter volume reflects the actual scale of market supply and serves as a key indicator of supply-demand balance in the hog market. Changes in slaughter volume are driven by factors such as farming output, market demand, and policy interventions. A reduction in slaughter volume may lead to insufficient supply and higher hog prices, while an increase in slaughter volume could suppress prices. Its CFI value underscores the sensitivity and importance of slaughter volume in hog price fluctuations. Slaughter volume is crucial for preventing overproduction or supply shortages through rational regulation, thereby maintaining market sustainability. The slaughter volume functions as an important metric for evaluating supply–demand imbalances and guiding the timing of slaughtering operations and market releases.

These three factors collectively form the core driving mechanism of hog price dynamics, encompassing demand-side (pork price), cost-side (piglet cost), and supply-side (slaughter volume) influences. From a practical perspective, uncovering these determinants provides actionable implications for both policymakers and farmers. For the government, real-time monitoring of pork prices, piglet costs, and slaughter volume can serve as early warning indicators for market volatility. By tracking these factors, authorities can better time the release of pork reserves, adjust subsidies, and guide breeding and slaughtering cycles, thereby smoothing sharp price fluctuations and protecting consumer welfare. For pig farmers, the identified features offer a scientific basis for production and investment decisions. Stabilizing piglet procurement costs and optimizing slaughter timing according to market signals can reduce operational risks and improve profitability. In this way, the DGCI model not only advances the understanding of causal price drivers but also supports the design of more effective policy tools and adaptive farming strategies to enhance the resilience and sustainability of the swine industry.

While the DGCI model identifies these factors as the most influential determinants of market dynamics, it is noteworthy that several external factors also exert significant yet more indirect effects. The comparatively low CFI values of these external variables indicate that, during the observation period, their causal influences on live pig prices were largely mediated or overshadowed by more immediate production- and cost-related mechanisms. For instance, while the volume and value of pork imports can theoretically alter the domestic supply-demand equilibrium, China’s pork import volume constitutes only a minor fraction of total national consumption under normal conditions, thereby exerting a limited effect on domestic price formation. Similarly, domestic pork consumption has remained relatively stable in relation to production levels, and the country’s modest macroeconomic fluctuations have had negligible influence on household pork demand. Consequently, the external economic environment, as proxied by the CPI, demonstrates only a marginal contribution to short-term pork price volatility. Moreover, China’s industrial policies are primarily designed to regulate the prospective production capacity of the pig industry, ensuring output stability over future months. As such, their regulatory effects tend to exhibit a substantial temporal lag—often six months or longer—rendering their short-run impact on pork prices considerably weaker than that of more immediate market indicators.