Digital Transformation Drivers, Technologies, and Pathways in Agricultural Product Supply Chains: A Comprehensive Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

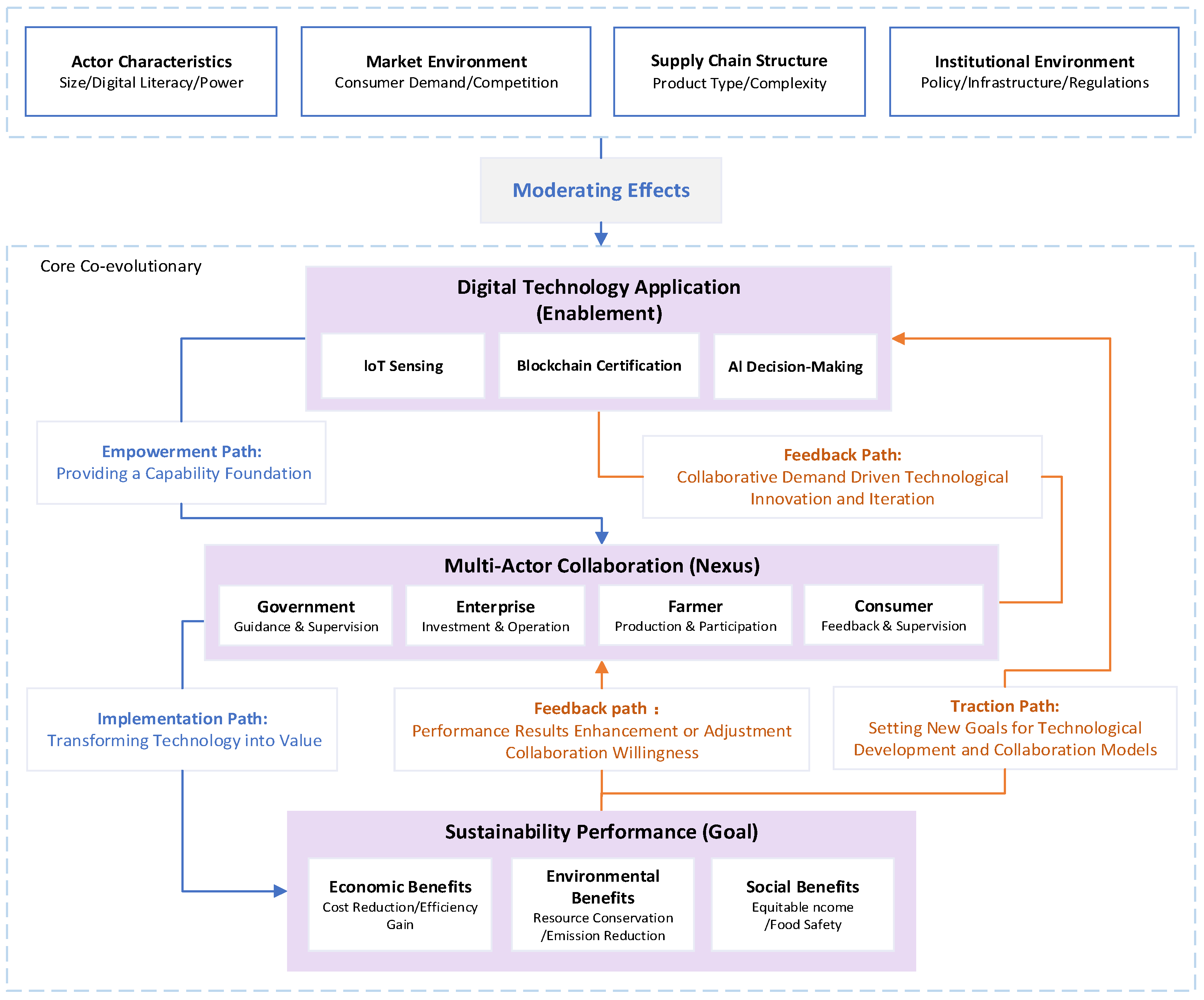

- (1)

- (2)

- Multi-agent collaboration as the value nexus. Digital tools generate value only when embedded in institutional arrangements that coordinate governments, firms, farmers and civil society. Ineffective governance produces data silos and entrenches power imbalances, preventing chain-wide value creation.

- (3)

- Sustainability as the ultimate metric. Success is judged not merely by productivity gains but by the simultaneous delivery of environmental integrity and social inclusivity.

- (1)

- Cross-theoretical Integration and the Construction of Mediating Mechanisms

- (2)

- Socio-Technical Systems Perspective

- (3)

- Dynamic and Feedback Perspective

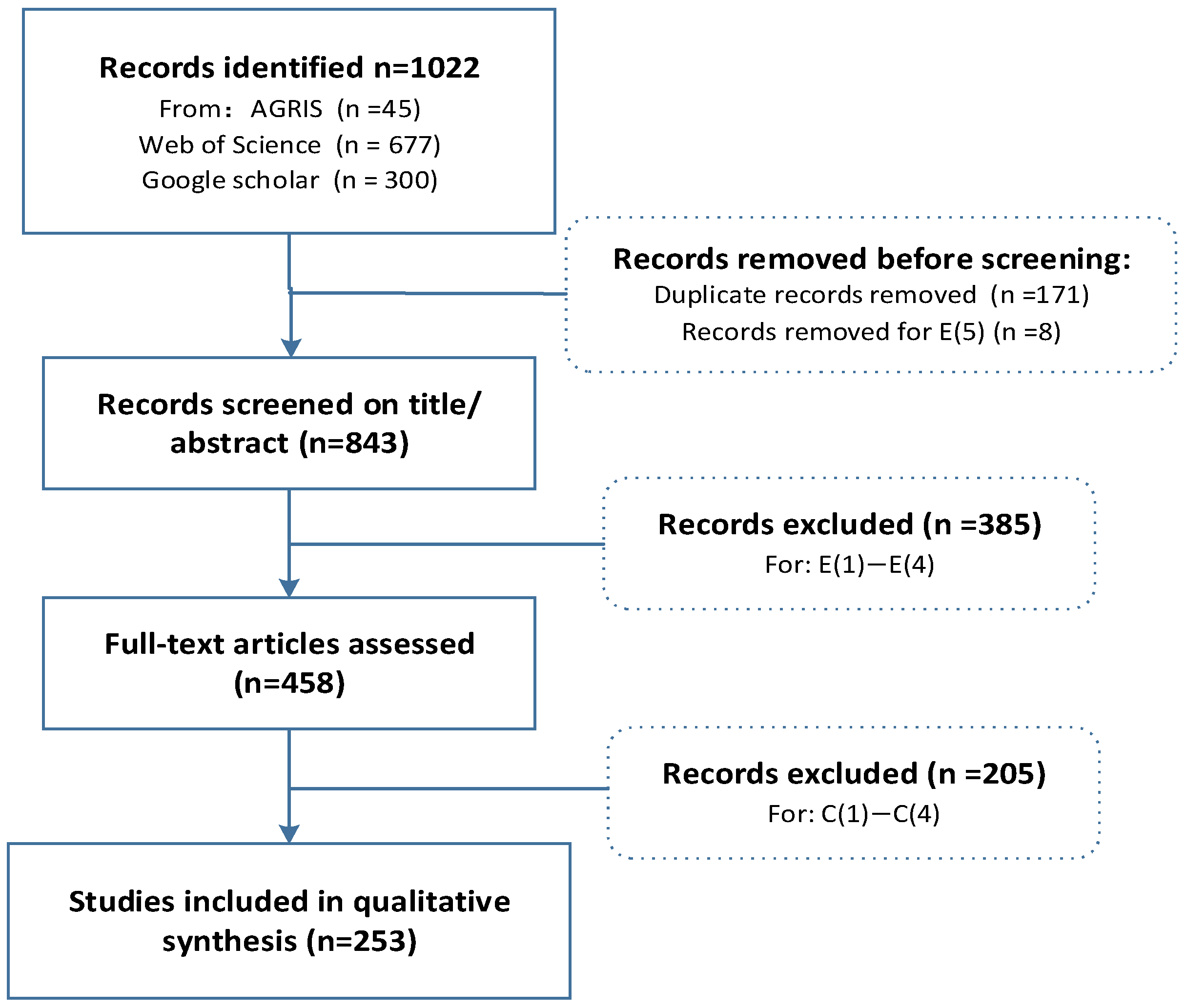

2. Literature Collection, Screening, and Organized Analysis

2.1. Preliminary Screening

- (1)

- Interdisciplinary breadth: The field spans technology adoption, governance mechanisms, sustainability performance, and multi-stakeholder collaboration. A purely systematic approach would risk overlooking nuanced, context-specific insights that are critical for understanding socio-technical transitions.

- (2)

- Conceptual integration: Our aim is to develop and propose a conceptual framework (TCS) that organizes fragmented knowledge and identifies emerging research gaps, rather than to test a narrowly defined hypothesis or intervention effect.

- (3)

- Inclusion of practice-based evidence: We deliberately incorporate the gray literature, policy reports, and seminal case studies that would typically be excluded by rigid systematic review protocols, yet are essential for understanding real-world implementation barriers and contextual complexities.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection and Quality Assessment

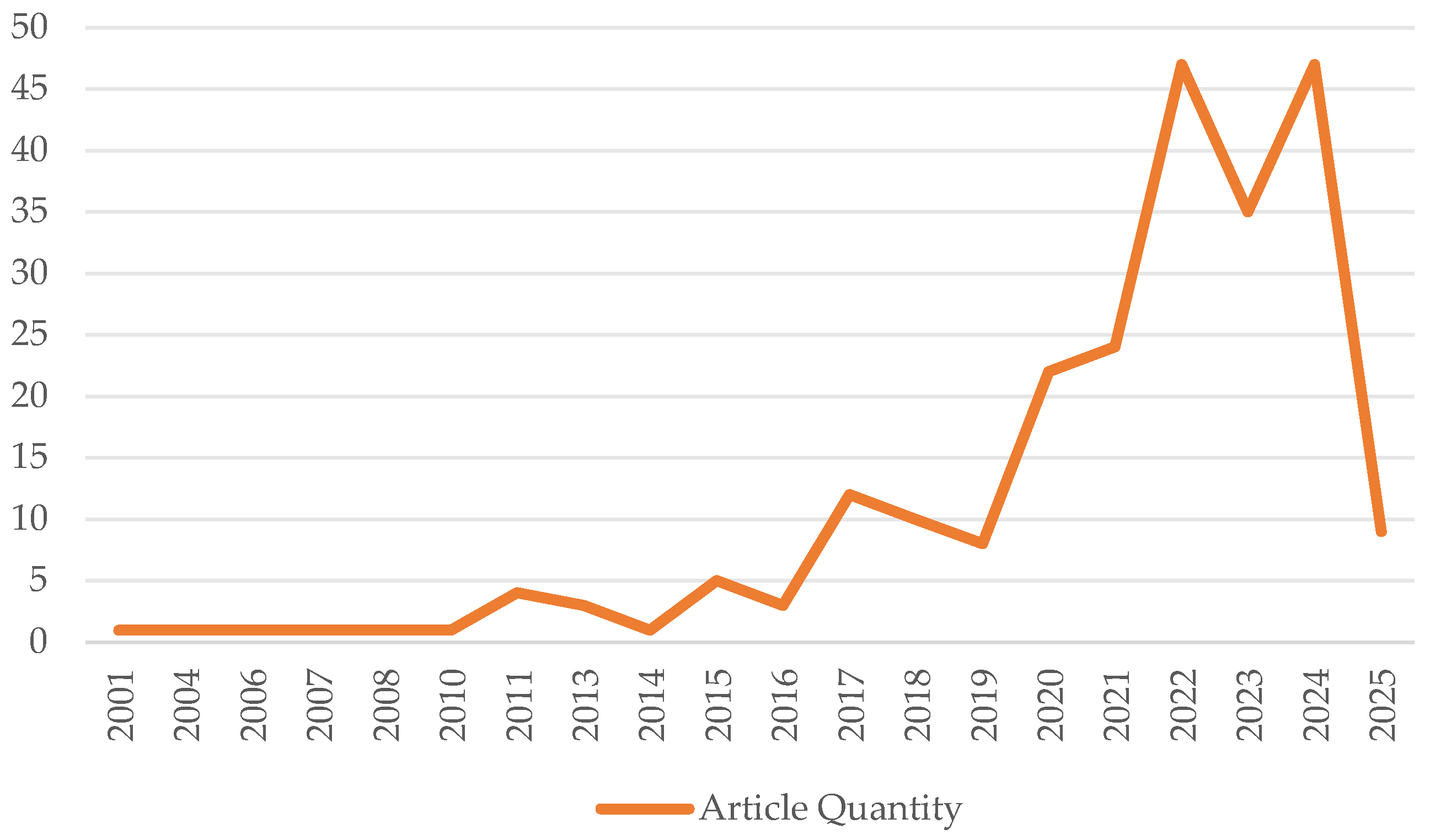

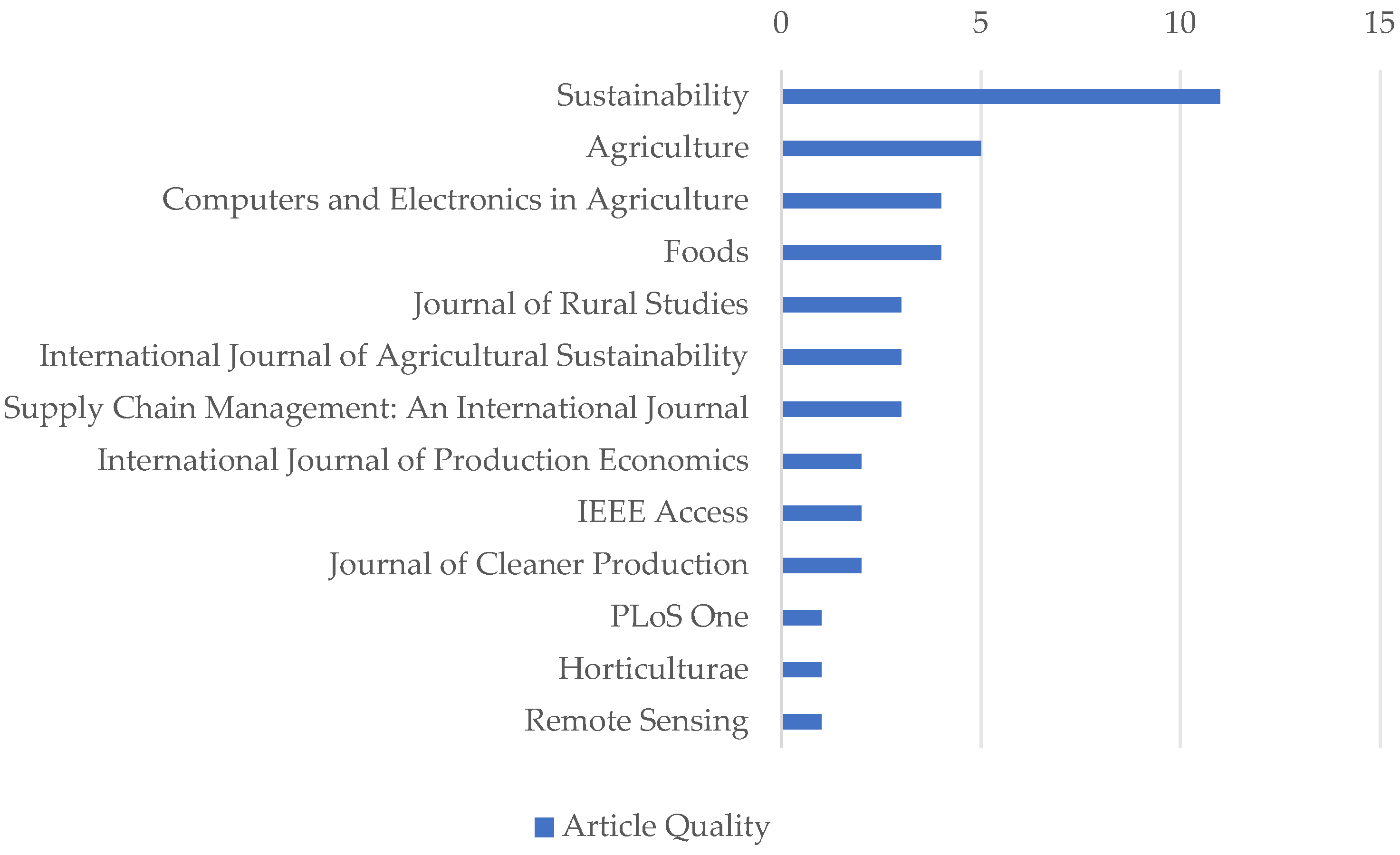

2.4. Descriptive Statistics

3. Literature Review

3.1. Drivers of the Digital Transformation in Agricultural Supply Chains

3.1.1. External Environmental Drivers

3.1.2. Internal Demand Drivers

3.2. Technological Applications in the Digital Transformation of the Agricultural Product Supply Chain

3.2.1. Internet of Things Technology

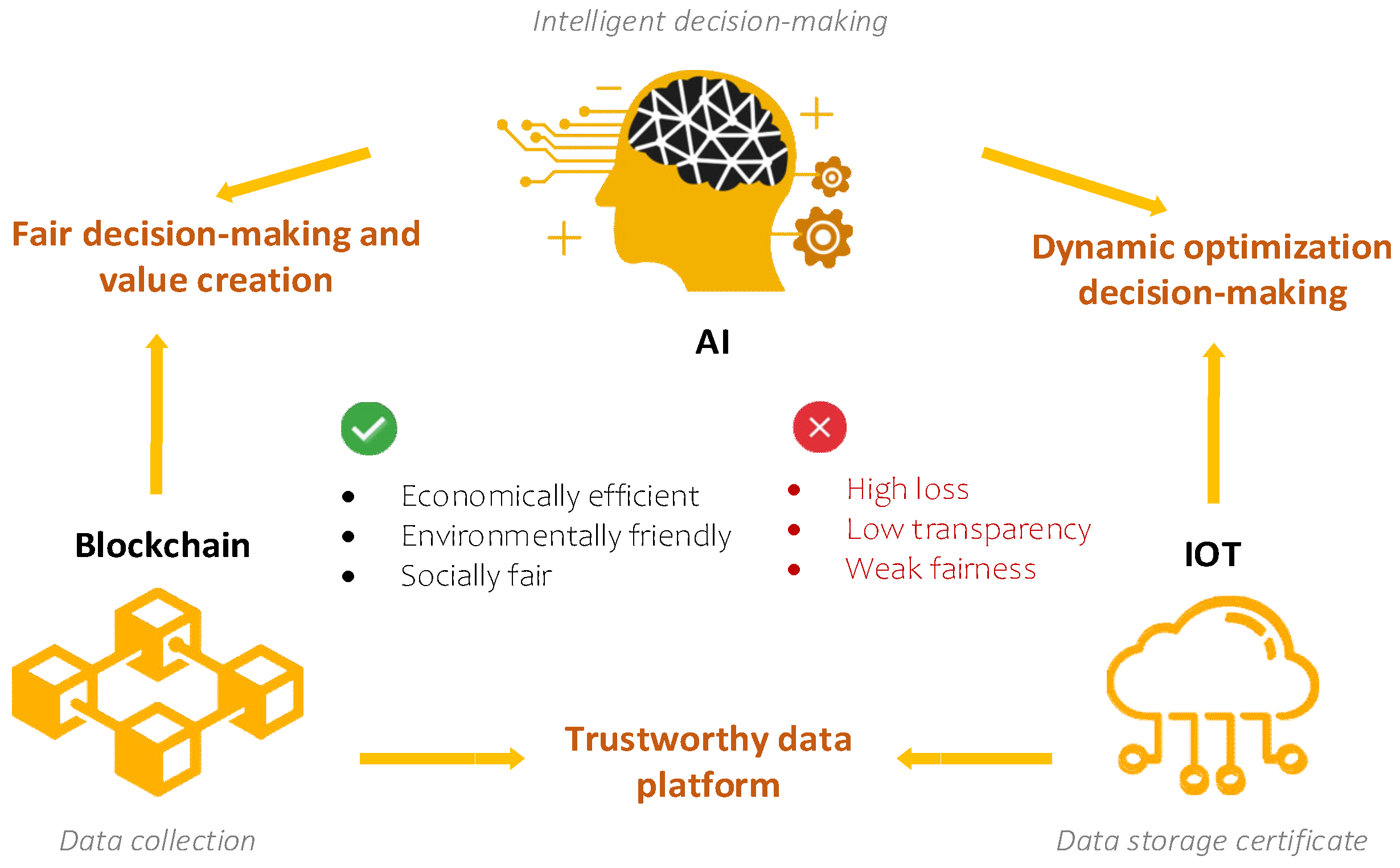

3.2.2. Blockchain Technology

3.2.3. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Technologies

3.2.4. Heterogeneous Application of Digital Technology in the Agricultural Products Supply Chain of Different Types

3.2.5. Synthesis and Comparative Analysis: Towards an Integrated Technological Ecosystem

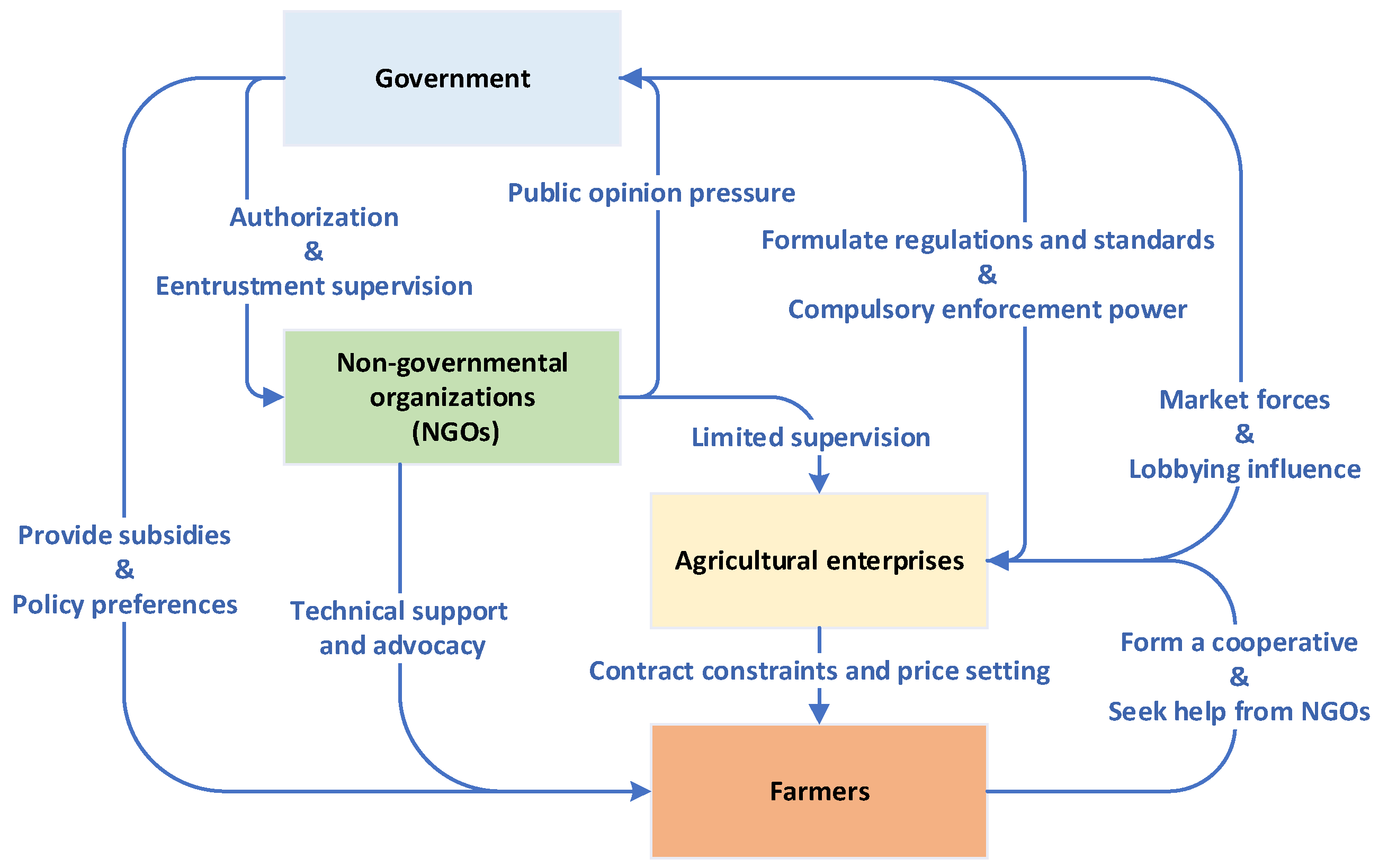

3.3. Multi-Agent Collaborative Mechanisms in the Digital Transformation of Agricultural Product Supply Chains

3.3.1. Motivations for Multi-Agent Collaboration

3.3.2. Main Actors and Collaboration Patterns

3.3.3. Factors Influencing Multistakeholder Collaborative Willingness

3.4. Digital-Driven Sustainable Development Path for Agricultural Supply Chains

3.4.1. Strengthening Technological Applications to Build a Solid Development Foundation

3.4.2. Integrating Supply Chain Resources and Optimizing Resource Allocation

3.4.3. Enhancing Data Analysis Capabilities to Strengthen Supply Chain Resilience

3.4.4. Enhancing Information Exchange and Improving Supply Chain Visibility and Collaboration

3.4.5. Establishing a Circular Economy Concept and Optimizing Industrial Processes

4. Discussion

4.1. Digital-Enabled Shortening of Agri-Food Supply Chains

4.1.1. Environmental and Economic Dividends

4.1.2. Implementation Challenges

4.2. Key Challenges and Adoption Barriers

4.2.1. Economic and Financial Barriers

4.2.2. Technical and Infrastructural Barriers

4.2.3. Social and Human Capital Barriers

4.2.4. Governance and Collaboration Barriers

- Local food platform cases in Australia during the COVID-19 period [132]

- 2.

- Italian smart greenhouse IoT pilot [53]

- 3.

- The UK’s fresh fruit and vegetable system addresses water risks [109]

4.3. Feasible Hypotheses of the TCS Framework

4.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

4.4.1. Limitations

4.4.2. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

5.1. Multidimensionality of Driving Forces Analysis

5.2. Integration Characteristics of the Technology System

5.3. Mutually Beneficial Synergy Through Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Luo, J.; Chen, J.; Qiu, C.; Jia, F. Agri-food supply chain management: Bibliometric and content analyses. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Acquah, S.J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, G.; Zhang, C.; Darko, R.O. Overview of modelling techniques for greenhouse microclimate environment and evapotranspiration. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2021, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, S.J.; Campbell, B.M.; Ingram, J.S.I. Climate change and food systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2012, 37, 195–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhdary, J.N.; Li, H.; Pan, X.; Zaman, M.; Anjum, S.A.; Yang, F.; Akbar, N.; Azamat, U. Modeling effects of climate change on crop phenology and yield of wheat-maize cropping system and exploring sustainable solutions. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2025, 105, 3679–3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyagi, S.; Bag, S.; Oberoi, S.S.; Banerjee, S.; Benabdellah, A.C. Transforming food systems: A comprehensive review and research agenda for digital technologies in circular and sustainable SC. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2024, 32, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borjas, C.J.C.; Pacheco, N.M.; Gálvez, S.B.T.; Mendivil, A.M.M.; Huarachi, D.M.C.; Cuaresma, J.R.M.; Ricardo, J. Digital transformation as a contributor of efficiency and resilience in the agri-food supply chain: A literature review. In Proceedings of the 3rd LACCEI International Multiconference on Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Regional Development—LEIRD 2023, Virtual, 4–6 December 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sermuksnyte-Alesiuniene, K.; Simanaviciene, Z.; Bickauske, D.; Mosiiuk, S.; Belova, I. Increasing the effectiveness of food supply chain logistics through digital transformation. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2021, 12, 789–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Miranda, C.; Dries, L. The role of coordination mechanisms and transaction costs promoting sustainability performance in agri-food supply chains: Evidence from Ecuador. Agribusiness, 2024; Early View. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayambe, J.; Heredia, R.M.; Torres, E.; Puhl, L.; Torres, B.; Barreto, D.; Heredia, B.N.; Vaca-Lucero, A.; Diaz-Ambrona, C.G.H. Evaluation of sustainability in strawberry crops production under greenhouse and open-field systems in the Andes. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2023, 21, 2255449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaud, J.-P.; Prioux, N.; Vialle, C.; Sablayrolles, C. Big Data for Agri-Food 4.0: Application to Sustainability Management for by-products supply chain. Comput. Ind. 2019, 111, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reina-Usuga, L.; Parra-López, C.; Sánchez-Zamora, P.; Carmona-Torres, C. Towards socio-digital rural territories to drive Digital Transformation: General Conceptualisation and application to the olive areas of Andalusia, Spain. Geoforum 2023, 145, 103827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulding, K.E. The Image: Knowledge in Life and Society; The University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Aubert, B.A.; Schroeder, A. Driving forces behind the digitalization of agriculture: A push-pull perspective. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 82, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2018. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/files/report/2018/TheSustainableDevelopmentGoalsReport2018-EN.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The Future of Food and Agriculture: Trends and Challenges; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2017; Available online: https://www.fao.org/global-perspectives-studies/fofa/en/ (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- United Nations World Water Assessment Programme. The United Nations World Water Development Report 2016: Water Jobs; U.N.E.S.C.O.: Paris, France, 2015; Available online: https://www.unwater.org/publications/un-world-water-development-report-2016 (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Bonah, E.; Huang, X.; Aheto, J.H.; Osae, R. Application of electronic nose as a non-invasive technique for odor fingerprinting and detection of bacterial foodborne pathogens: A Review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 57, 1977–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afraz, M.T.; Khan, M.R.; Roobab, U.; Noranizan, M.A.; Tiwari, B.K.; Rashid, M.T.; Inam–Ur–Raheem, M.; Hashemi, S.M.B.; Aadil, R.M. Impact of novel processing techniques on the functional properties of egg products and derivatives: A review. J. Food Process Eng. 2020, 43, e13564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Luthra, S.; Kumar, A.; Agrawal, R.; Frederico, G.F. Exploring the relationship between digitalization, resilient agri-food supply chain management practices and firm performance. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2024, 37, 511–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, M.I.; Barrett, C.B.; Raney, T.; Pinstrup-Andersen, P.; Meerman, J.; Croppenstedt, A.; Carisma, B.; Thompson, B. Post-green revolution food systems and the triple burden of malnutrition. Food Policy 2013, 42, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiquy, M.; JiaoJiao, Y.; Rahman, M.H.; Iqbal, M.W.; Al-Maqtari, Q.A.; Easdani; Yiasmin, M.N.; Ashraf, W.; Hussain, A.; Zhang, L. Advances of protein functionalities through conjugation of protein and polysaccharide. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2023, 17, 2077–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group. Enabling the Business of Agriculture 2016: Comparing Regulatory Good Practices; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/cbb93de6-0b27-58e1-b475-e1a1eeda2b56 (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Shukla, M.; Jharkharia, S. Agri-fresh produce supply chain management: A state-of-the-art literature review. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2013, 33, 114–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsson, J.; Cederberg, C.; Sonesson, U.; Otterdijk, R.V.; Meybeck, A. Global Food Losses and Food Waste: Extent, Causes and Prevention; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2011; Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/global-food-losses-and-food-waste-extent-causes-and-prevention (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Borrello, M.; Caracciolo, F.; Lombardi, A.; Pascucci, S.; Cembalo, L. Consumers’ perspective on circular economy strategy for reducing food waste. Sustainability 2017, 9, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, R.; Urioste, S.; Rivera, T.; Schiek, B.; Nyakundi, F.; Vergara, J.; Mwanzia, L.; Loaiza, K.; Gonzalez, C. Where is my crop? Data-driven initiatives to support integrated multi-stakeholder agricultural decisions. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 737528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basel, A.M.; Nguyen, K.T.; Arnaud, E.; Craparo, A.C. The foundations of big data sharing: A CGIAR international research organization perspective. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1107393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, S.S.; Gunasekaran, A.; Gawankar, S.A. Achieving sustainable performance in a data-driven agriculture supply chain: A review for research and applications. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 219, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivelli, L.; Apicella, A.; Chiarello, F.; Rana, R.; Fantoni, G.; Tarabella, A. From precision agriculture to industry 4.0: Unveiling technological connections in the agrifood sector. BFJ 2019, 121, 1730–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Yi, Y.; Li, C.; Shin, C. Sustainability in global agri-food supply chains: Insights from a comprehensive literature review and the ABCDE framework. Foods 2024, 13, 2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, S.; Yi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shin, C. Digital technology increases the sustainability of cross-border agro-food supply chains: A review. Agriculture 2024, 14, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, X.; Shu, L.; Hancke, G.P.; Abu-Mahfouz, A.M. From Industry 4.0 to Agriculture 4.0: Current Status, Enabling Technologies, and Research Challenges. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021, 17, 4322–4334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakku, E.; Fielke, S.; Fleming, A.; Stitzlein, C. Reflecting on opportunities and challenges regarding implementation of responsible digital agri-technology innovation. Sociol. Rural. 2022, 62, 363–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, R.; Noy, I. The global costs of extreme weather that are attributable to climate change. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyeaka, H.; Nwauzoma, U.M.; Akinsemolu, A.A.; Tamasiga, P.; Duan, K.R.; Al-Sharify, Z.T.; Siyanbola, K.F. The ripple effects of climate change on agricultural sustainability and food security in Africa. Food Energy Secur. 2024, 13, e567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Li, X.; Lu, H.; Tong, L.; Kang, S. Crop acreage planning for economy-resource-efficiency coordination: Grey information entropy based uncertain model. Agric. Syst. 2023, 215, 103852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Saber, K.; Hu, Y.; Ray, R.L.; Kaya, Y.Z.; Dehghanisanij, H.; Kisi, O.; Elbeltagi, A. Modelling reference evapotranspiration using principal component analysis and machine learning methods under different climatic environments. Irrig. Drain. 2023, 72, 945–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, M.R.; Almuflih, A.S.; Sharma, J.; Tyagi, M.; Singh, S.; Almakayeel, N. Assessment of the climate-smart agriculture interventions towards the avenues of sustainable production-consumption. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K. Sustainable consumption and production in the food supply chain: A conceptual framework. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 195, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.S.; Singh, A.R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Raut, R.D.; Narkhede, B.E. A systematic literature review of the agro-food supply chain: Challenges, network design, and performance measurement perspectives. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 29, 685–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolidakis, S.A.; Kandris, D.; Vergados, D.D.; Douligeris, C. Energy efficient automated control of irrigation in agriculture by using wireless sensor networks. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2015, 113, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrustek, L. Sustainability driven by agriculture through digital transformation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Bilali, H.; Strassner, C.; Ben Hassen, T. Sustainable Agri-Food Systems: Environment, Economy, Society, and policy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, A. Digital from farm to fork: Infrastructures of quality and control in food supply chains. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 91, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. To recover faster from covid-19, open up: Managerial implications from an open innovation perspective. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 88, 410–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, D. Predicting the impacts of epidemic outbreaks on global supply chains: A simulation-based analysis on the coronavirus outbreak (COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2) case. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2020, 136, 101922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciano, M.P.; Ardolino, M.; Müller, J.M. Digital Supply Chain: Conceptualisation of the Research Domain. J. Bus. Logist. 2022, 43, 271–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazrati, M.; Dara, R.; Kaur, J. On-farm data security: Practical recommendations for securing farm data. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 198, 107036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiadis, F.; Poole, N. Emergent supply chains in the agrifood sector: Insights from a whole chain approach. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2015, 20, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alojail, M.; Khan, S.B. Impact of digital transformation toward sustainable development. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.J.; Guzmán, C.; Ahumada, P. Assessing the digital transformation in agri-food cooperatives and its determinants. J. Rural Stud. 2024, 105, 103168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, A.; Balabantaray, S.; Arora, M. A digital ecosystem for sustainable fruit supply chain in uttarakhand: A comprehensive review. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 13217–13252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersani, C.; Ruggiero, C.; Sacile, R.; Soussi, A.; Zero, E. Internet of Things approaches for monitoring and control of smart greenhouses in Industry 4.0. Energies 2022, 15, 3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Lopez, J.J.; Castillo-Atoche, A.A.; Vazquez-Castillo, J.; Sanchez-Sinencio, E. Smart soil parameters estimation system using an autonomous wireless sensor network with dynamic power management strategy. IEEE Sens. J. 2018, 18, 8913–8923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Salaam, G.; Hanan Abdullah, A.; Hossein Anisi, M. Energy-efficient data reporting for navigation in position-free hybrid wireless sensor networks. IEEE Sens. J. 2017, 17, 2289–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, N.N.; Dixit, Y.; Al-Mallahi, A.; Bhullar, M.S.; Upadhyay, R.; Martynenko, A. IoT, big data, and artificial intelligence in agriculture and food industry. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 6305–6324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuran, M.C.; Salam, A.; Wong, R.; Irmak, S. Internet of underground things in precision agriculture: Architecture and technology aspects. Ad Hoc Networks 2018, 81, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazi, S.; Khawaja, B.A.; Farooq, Q.U. IoT-equipped and AI-enabled next generation smart agriculture: A critical review, current challenges and future trends. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 21219–21235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Chikangaise, P.; Shi, W.; Chen, W.-H.; Yuan, S. Review of intelligent sprinkler irrigation technologies for Remote Autonomous System. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2018, 11, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbasi, E.; Zaki, C.; Topcu, A.E.; Abdelbaki, W.; Zreikat, A.I.; Cina, E.; Shdefat, A.; Saker, L. Crop prediction model using machine learning algorithms. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, T.C.; Yang, H.; Chung, Y.C.; Hsu, C.H. A creative IoT agriculture platform for cloud fog computing. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2020, 28, 100285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Analysis of the Critical Role of a Smart Agricultural Internet of Things System in Industrial Benefit Evaluation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 195, 106822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranto, T.H.; Noman, A.A.; Mahmud, A.; Haque, A.B. Blockchain and smart contract for IoT enabled smart agriculture. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2021, 7, e407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozari, H.; Fallah, M.; Kazemipoor, H.; Najafi, S.E. Big data analysis of IoT-based supply chain management considering FMCG industries. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2021, 32, 767–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, G.; Liu, L.; Lai, X.; Xu, G. IoT-based tracking and tracing platform for prepackaged food supply chain. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 1906–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Liu, L. Risk assessment of agricultural supermarket supply chain in big data environment. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2020, 28, 100420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Pan, X.; Zhang, X. Big data-driven risk decision-making and safety management in agricultural supply chains. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crops Foods 2024, 16, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Garg, D.; Luthra, S. Development of IoT based data-driven agriculture supply chain performance measurement framework. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2020, 34, 292–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendros, A.; Drosatos, G.; Efraimidis, P.S.; Tsirliganis, N.C. Blockchain applications in agriculture: A scoping review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, S.; Gunasekaran, A.; Arha, H. Understanding the blockchain technology adoption in supply chains—Indian context. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 2009–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, K.; Nizamuddin, N.; Jayaraman, R.; Omar, M.A. Blockchain-Based Soybean Traceability in Agricultural Supply Chain. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 73285–73300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, H.; Yu, P.; Chen, Z. Optimizing decisions for post-harvest ripening agricultural produce supply chain management: A dynamic quality-based model. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2023, 30, 3625–3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Huang, X.; Fang, H.; Wang, V.; Hua, Y.; Wang, J.; Yin, H.; Yi, D.; Yau, L. Blockchain technology in current Agric Syst: From techniques to applications. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 143920–143937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogerson, M.; Parry, G.C. Blockchain: Case studies in food supply chain visibility. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2020, 25, 601–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yu, J. Blockchain’s impact on platform supply chains: Transaction cost and information transparency perspectives. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 61, 3703–3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, H.R.; Musamih, A.; Salah, K.; Jayaraman, R.; Omar, M.; Arshad, J.; Boscovic, D. Smart Agriculture Assurance: IOT and Blockchain for trusted sustainable produce. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 224, 109184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez, C.C.; Gonzales, G.R.; Corrales, J.C. Blockchain and agricultural sustainability in south America: A systematic review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1347116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsan, I.; Khalid, M.I.; Ricci, L.; Iqbal, J.; Alabrah, A.; Ullah, S.S.; Alfakih, T.M. A Conceptual Model for Blockchain-Based Agriculture Food Supply Chain System. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 198, 107035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Cao, Y. Dynamic evolutionary game approach for blockchain-driven incentive and restraint mechanism in supply chain financing. Systems 2023, 11, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi Maniam, P.S.; Acharya, N.; Sassenberg, A.-M.; Soar, J. Determinants of blockchain technology adoption in the Australian Agricultural Supply Chain: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glikson, E.; Woolley, A.W. Human trust in artificial intelligence: Review of empirical research. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2020, 14, 627–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.; Muduli, K.; Raut, R.; Narkhede, B.E.; Shee, H.; Jana, S.K. Challenges facing artificial intelligence adoption during COVID-19 pandemic: An investigation into the Agriculture and Agri-Food Supply Chain in India. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamilaris, A.; Prenafeta-Boldú, F.X. Deep learning in agriculture: A survey. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 147, 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aylak, B.L. Artificial intelligence and machine learning applications in agricultural supply chain: A critical commentary. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2021, 30, 8905–8916. [Google Scholar]

- Drury, B.; Valverde-Rebaza, J.; Moura, M.-F.; de Andrade Lopes, A. A survey of the applications of Bayesian networks in Agriculture. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2017, 65, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croci, M.; Impollonia, G.; Meroni, M.; Amaducci, S. Dynamic maize yield predictions using machine learning on multi-source data. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Jin, D.; Gu, Y.H.; Park, C.J.; Han, S.K.; Yoo, S.J. STL-ATTLSTM: Vegetable Price Forecasting Using STL and Attention Mechanism-Based LSTM. Agriculture 2020, 10, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.; Marjan, M.A.; Uddin, M.P.; Afjal, M.I.; Kardy, S.; Ma, S.; Nam, Y. Ensemble machine learning-based recommendation system for effective prediction of suitable agricultural crop cultivation. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1234555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Lu, X.; Mao, H.; Wu, X.; Gao, H. Quantitative determination of rice moisture based on hyperspectral imaging technology and BCC-LS-SVR algorithm. J. Food Process. Eng. 2016, 40, e12446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, A.; Agrawal, S.; Chatterjee, J.M. Wheat Seed Classification: Utilizing Ensemble Machine Learning Approach. Sci. Program. 2022, 2022, 2626868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudha, P.; Kumaran, P. Early detection and control of anthracnose disease in cashew leaves to improve crop yield using image processing and machine learning techniques. Signal, Image Video Process. 2023, 17, 3323–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Sun, J.; Mao, H.; Wu, X.; Zhang, X.; Yang, N. Visualization research of moisture content in leaf lettuce leaves based on WT-PLSR and hyperspectral imaging technology. J. Food Process. Eng. 2017, 41, e12647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, T.; Bonnell, R.B.; Prasher, S.O.; Paulet, E. Measuring performance in precision agriculture: CART—A decision tree approach. Agric. Water Manag. 2006, 84, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Sun, J.; Mao, H.; Wu, X.; Gao, H. Quantitative determination of rice starch based on hyperspectral imaging technology. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017, 20 (Suppl. 1), S1037–S1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Huang, X.; Wang, L.; Chang, X.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y. Qualitative and quantitative assessment of flavor quality of Chinese soybean paste using multiple sensor technologies combined with chemometrics and a data fusion strategy. Food Chem. 2023, 405, 134859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, K.; Sun, J.; Zhou, X.; Nirere, A.; Tian, Y.; Wu, X. Nondestructive detection for egg freshness grade based on hyperspectral imaging technology. J. Food Process. Eng. 2020, 43, e13422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Sun, J.; Lu, B.; Chen, Q.; Xun, W.; Jin, Y. Classification of oolong tea varieties based on hyperspectral imaging technology and BOSS-LightGBM model. J. Food Process. Eng. 2019, 42, e13289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Xu, J.; Shi, G.; Huang, X. Evaluation and countermeasures for the secure supply of fruit and vegetable products in jiangyin, China. Agro Food Ind. Hi-Tech 2016, 27, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Olawale, R.A.; Olawumi, M.A.; Oladapo, B.I. Sustainable farming with machine learning solutions for minimizing food waste. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2025, 112, 102611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Zhang, M.; Xu, B.; Guo, Z. Intelligent quality control of gelatinous polysaccharide-based fresh products during cold chain logistics: A review. Food Biosci. 2024, 62, 105081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Lai, K.K.; Leung, S.C.H.; Liang, L. Modelling and analysis of inventory replenishment for perishable agricultural products with buyer-seller collaboration. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2011, 42, 1207–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boshkoska, B.M.; Liu, S.; Zhao, G.; Fernandez, A.; Gamboa, S.; del Pino, M.; Zarate, P.; Hernandez, J.; Chen, H. A decision support system for evaluation of the knowledge sharing crossing boundaries in agri-food value chains. Comput. Ind. 2019, 110, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowersox, D.J.; Closs, D.J.; Stank, T.P. How to master cross-enterprise collaboration. Supply Chain Manag. Rev. 2003, 7, 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, Y.J.; Wang, J.L.; Guo, X.Y.; Xu, Y. The Collaboration Mechanism of Agricultural Product Supply Chain Dominated by Farmer Cooperatives. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zi, W.; Zhou, J.; Xu, H.; Li, G.; Lin, G. Preserving relational contract stability of fresh agricultural product supply chains. J. Ind. Manag. Optim. 2021, 17, 2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frohlich, M.T.; Westbrook, R. Arcs of integration: An International Study of Supply Chain Strategies. J. Oper. Manag. 2001, 19, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.M.; Quaddus, M. Supply Chain Readiness, response and recovery for resilience. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2016, 21, 709–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jüttner, U.; Maklan, S. Supply Chain Resilience in the global financial crisis: An empirical study. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2011, 16, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurek, M.; Garbutt, G.; Lieb, T.; Hess, T.; Ingram, J. Increasing resilience of the UK fresh fruit and vegetable system to water-related risks. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Xu, Y. Evolutionary game analysis of the quality of agricultural products in Supply Chain. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matopoulos, A.; Vlachopoulou, M.; Manthou, V.; Manos, B. A conceptual framework for supply chain collaboration: Empirical evidence from the agri-food industry. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2007, 12, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo-Oshima, S. International actions in spurring innovation in agriculture water management. Irrig. Drain. 2023, 72, 1241–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, R.; Ravi, V. Modeling enablers of supply chain risk mitigation in electronic supply chains: A grey-DEMATEL approach. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2015, 87, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nha Trang, N.T.; Nguyen, T.-T.; Pham, H.V.; Anh Cao, T.T.; Trinh Thi, T.H.; Shahreki, J. Impacts of collaborative partnership on the performance of Cold Supply Chains of agriculture and foods: Literature review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Du, H.; Sun, Y. Collaboration among governments, pesticide operators, and farmers in regulating pesticide operations for Agricultural Product Safety. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami, K.; Salehi, L. Rural Cooperatives Social Responsibility in promoting sustainability-oriented activities in the agricultural sector: Nexus of community, Enterprise, and government. Sustain. Futures 2024, 7, 100150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.-P.; Lei, H.-Y. Simulation study on the evolutionary game mechanism of collaborative innovation in Supply Chain Enterprises and its influencing elements. J. Math. 2021, 2021, 8038672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resende, R.T.; Hickey, L.; Amaral, C.H.; Peixoto, L.L.; Marcatti, G.E.; Xu, Y. Satellite-enabled enviromics to enhance crop improvement. Mol. Plant 2024, 17, 848–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Qiang, C. Evolutionary game theoretic analysis on low-carbon strategy for Supply Chain Enterprises. J. Cleaner Prod. 2019, 230, 981–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Pham, M.H.; Yang, B.; Sun, J.W.; Tran, P.N. Improving vegetable supply chain collaboration: A case study in Vietnam. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2021, 27, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidoğlu, A.; Weber, G.-W. A novel Nash-based low-carbon implementation in Agricultural Supply Chain Management. J. Cleaner Prod. 2024, 449, 141846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, S. The evolutionary game analysis of multiple stakeholders in the low-carbon agricultural innovation diffusion. Complexity 2020, 2020, 6309545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholez, C.; Pauly, O.; Mahdad, M.; Mehrabi, S.; Giagnocavo, C.; Bijman, J. Heterogeneity of inter-organizational collaborations in agrifood chain sustainability-oriented innovations. Agric. Syst. 2023, 212, 103774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Tao, X. A study on the evolutionary game of the four-party agricultural product supply chain based on collaborative governance and Sustainability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Zhang, L.; Song, Y. The impact of environmental regulatory instruments on agribusiness technology innovation—A study of configuration effects based on fsQCA. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0294662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C. Game theory-based analysis of local governments’ behavioral dissimilation in the third-party soil pollution control under Chinese-style fiscal decentralization. Land 2021, 10, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouvière, E.; Royer, A. Public Private Partnerships in Food Industries: A road to success? Food Policy 2017, 69, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Jia, F.; Doherty, B. The role of ngos in Sustainable Supply Chain Management: A Social Movement Perspective. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2021, 27, 383–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, Y.P.; Park, C.; Petersen, B. The effect of local stakeholder pressures on responsive and strategic CSR activities. Bus. Soc. 2021, 60, 582–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralston, R.; Townsend, B.; Arnanz, L.; Baum, F.; Cullerton, K.; Holmes, R.; Martin, J.; Collin, J.; Friel, S. NGOs and global business regulation of transnational alcohol and ultra-processed food industries. Policy Soc. 2024, 43, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerni, P.; Nichterlein, K.; Rudgard, S.; Sonnino, A. Making Agricultural Innovation Systems (AIS) work for development in tropical countries. Sustainability 2015, 7, 831–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godrich, S.L.; Macau, F.; Kent, K.; Lo, J.; Devine, A. Food supply impacts and solutions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic: A regional australian case study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, M.; Zhang, Q. Supply Chain Collaboration: Impact on Collaborative Advantage and Firm Performance. J. Oper. Manag. 2010, 29, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Song, W.; Lu, Y.; Bao, X. Merkel government’s refugee policy: Under Bounded rationality. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, D.M.; Emmelhainz, M.A.; Gardner, J.T. Developing and implementing supply chain partnerships. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 1996, 7, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barratt, M. Understanding the meaning of collaboration in the supply chain. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2004, 9, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zheng, J. Intelligent Management of Supply Chain Logistics based on 5G lot. Cluster Comput. 2022, 25, 2271–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lezoche, M.; Hernandez, J.E.; Alemany Díaz, M.; del Panetto, H.; Kacprzyk, J. Agri-Food 4.0: A survey of the supply chains and technologies for the Future Agriculture. Comput. Ind. 2020, 117, 103187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zong, Y. Benefit-sharing mechanism in cross-regional agricultural product supply chain: A grounded theory approach. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Yao, J. Supply chain scheduling optimization in an agricultural socialized service platform based on the coordination degree. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcão, R.N.; Vrana, M.; Hudek, C.; Pittarello, M.; Zavattaro, L.; Moretti, B.; Strauss, P.; Liebhard, G.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; et al. Farmers’ perception of Soil Health: The use of quality data and its implication for farm management. Soil Use Manag. 2024, 40, e13023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settle, W.; Garba, M.H. Sustainable crop production intensification in the Senegal and Niger River basins of francophone West Africa. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2011, 9, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinseu, E.L.; Dougill, A.J.; Stringer, L.C. Strengthening Conservation Agriculture Innovation Systems in sub-Saharan africa: Lessons from a stakeholder analysis. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2021, 20, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catarino, R.; Therond, O.; Berthomier, J.; Miara, M.; Mérot, E.; Misslin, R.; Vanhove, P.; Villerd, J.; Angevin, F. Fostering local crop-livestock integration via legume exchanges using an innovative integrated assessment and modelling approach based on the Maelia Platform. Agric. Syst. 2021, 189, 103066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.-H. Leveraging image analysis for high-throughput phenotyping of legume plants. Legum. Res.-Int. J. 2024, 47, 1715–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Wang, H.; Rahman, A.; Abdul Azim, J.; Hussain Memon, W.; Qian, L. Structural equation model of young farmers’ intention to adopt sustainable agriculture: A case study in Bangladesh. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2021, 37, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Z.; Yang, Y.; Yang, X.; Ma, W.; Jiang, W.; Li, Y.; Chen, G.; Zhang, W.; Zhuang, M.; Wang, C.; et al. Promoting sustainable smallholder farming via multistakeholder collaboration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2319519121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyekumhene, C.; de Vries, J.R.; van Paassen, A.; Schut, M.; MacNaghten, P. Making Smallholder Value chain partnerships inclusive: Exploring Digital Farm monitoring through farmer friendly smartphone platforms. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J. Tam-based study of farmers’ live streaming e-commerce adoption intentions. Agriculture 2024, 14, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, G.E., Jr.; Antunes, J.A., Jr.; Wegner, D.; Adami, V.S. Creating a digital platform for the agricultural cooperative system through Interorganizational collaboration. J. Rural Stud. 2024, 110, 103388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaioannou, G.; Mohammed, A.M.; Despoudi, S.; Saridakis, G.; Papadopoulos, T. The role of adverse economic environment and human capital on collaboration within agri-food supply chains. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 52, 102077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez i Molist, A.; Kallas, Z.; Guadarrama Fuentes, O.V. Assessing the downstream and upstream preferences of stakeholders for sustainability attributes in the tomato value chain. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biró, S.; Hamza, E.; Rácz, K. Economic and social importance of vertical and horizontal forms of agricultural cooperation in Hungary. Stud. Agric. Econ. 2016, 118, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widadie, F.; Bijman, J.; Trienekens, J. Alignment between vertical and horizontal coordination for food quality and safety in Indonesian vegetable chains. Agric. Food Econ. 2022, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fynes, B.; Voss, C.; de Búrca, S. The impact of supply chain relationship quality on quality performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2005, 96, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezeshki, Y.; Baboli, A.; Cheikhrouhou, N.; Modarres, M.; Jokar, M.R. A rewarding-punishing coordination mechanism based on Trust in a divergent supply chain. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2013, 230, 527–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jraisat, L.; Jreissat, M.; Upadhyay, A.; Sajjad, F.; Balodi, K.C. Paradox of strategic partnerships for sustainable value chains: Perspectives of not-for-profit actors. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 3491–3508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, I.-L.; Chiu, M.-L. Examining supply chain collaboration with determinants and performance impact: Social capital, justice, and technology use perspectives. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 39, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, L.W.; Roesch-McNally, G.; Wilke, A.K. Upper Midwest farmer perceptions: Too much uncertainty about impacts of climate change to justify changing current agricultural practices. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 054004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot-Kormelinck, A.; Trienekens, J.; Bijman, J. Coordinating Food Quality: How Do Quality Standards Influence Contract Arrangements? A study on Uruguayan food supply chains. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2021, 26, 449–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Yang, J. Evolutionary game analysis of stakeholders’ decision-making behavior in agricultural data supply chain. Front. Phys. 2024, 11, 1321973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Xiong, L.; Li, Y.; Chen, Q.; Yu, Y.; Wang, J. Contract coordination of fresh agri-product supply chain under O2O model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.J.; Zhang, J.M. An evolutionary game analysis of benefit sharing among members of rural professional economic associations. Stat. Decis. 2014, 19, 71–72. [Google Scholar]

- Panda, S.; Modak, N.M.; Basu, M.; Goyal, S.K. Channel coordination and profit distribution in a social responsible three-layer supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 168, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quayson, M.; Bai, C.; Osei, V. Digital inclusion for resilient post-COVID-19 supply chains: Smallholder farmer perspectives. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2020, 48, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; He, Y.; Wu, Z. Design of a blockchain-enabled traceability system framework for food supply chains. Foods 2022, 11, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Shetty, S.; Tosh, D.; Kamhoua, C.; Kwiat, K.; Njilla, L. Provchain: A blockchain-based data provenance architecture in cloud environment with enhanced privacy and availability. In Proceedings of the 2017 17th IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Cluster, Cloud and Grid Computing (CCGRID), Madrid, Spain, 14–17 May 2017; pp. 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, S.; Kaur, P.; Fosso Wamba, S.; Dhir, A. Big Data in operations and Supply Chain Management: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 59, 3509–3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Yi, J. Analysis of the impact of Big Data and Artificial Intelligence Technology on Supply Chain Management. Symmetry 2023, 15, 1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutaib, M.; Ahajjam, T.; Fattah, M.; Farhaoui, Y.; Aghoutane, B.; El Bekkali, M. Optimization of the energy consumption of connected objects. Int. J. Interact. Mobile Technol. 2021, 15, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, F. SCOR template—A simulation based dynamic supply chain analysis tool. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 131, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, M.; Tiwari, M.K. Big-data analytics framework for incorporating smallholders in sustainable palm oil production. Prod. Plan. Control 2017, 28, 1365–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelsma, I.; Slingerland, M.; Giller, K.E.; Bijman, J. Collective action in a smallholder oil palm production system in Indonesia: The key to sustainable and inclusive smallholder palm oil? J. Rural Stud. 2017, 54, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitis, K.G.; Symeonaki, E.G. Agriculture 4.0: The role of innovative smart technologies towards sustainable farm management. Open Agric. J. 2020, 14, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, F.T.; Garrett, B. Technology for sustainable urban food ecosystems in the developing world: Strengthening the nexus of food-water-energy-nutrition. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 2, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucci, G.; Bentivoglio, D.; Finco, A.; Belletti, M. Exploring the impact of innovation adoption in agriculture: How and where Precision Agriculture Technologies can be suitable for the Italian farm system? IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 275, 012004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenthaler, R. Creating real-time supply chain visibility. Electron. Bus. 2003, 29, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Ahoa, E.; Kassahun, A.; Tekinerdogan, B. Configuring supply chain business processes using the SCOR Reference Model. In International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 319, pp. 338–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Perez, P.; Xiao, J.; Munekata, P.E.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Barba, F.J.; Rajoka, M.S.; Barros, L.; Mascoloti Sprea, R.; Amaral, J.S.; Prieto, M.A.; et al. Revalorization of almond by-products for the design of Novel Functional Foods: An updated review. Foods 2021, 10, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsoulfas, G.T.; Mouzakitis, Y. Framing the transition towards sustainable agri-food supply chains. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 899, 012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, T.; Li, Z.; Naseeb, J.; Sarwar, A.; Zhao, L.; Lin, L.; Al Asmari, F. Role of bacterial exopolysaccharides in edible films for food safety and sustainability. Current trends and future perspectives. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2024, 36, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Zabed, H.M.; Wei, Y.; Qi, X. Technoeconomic and environmental perspectives of biofuel production from sugarcane bagasse: Current status, challenges and future outlook. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 188, 115684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandemir, K.; Piskin, E.; Xiao, J.; Tomas, M.; Capanoglu, E. Fruit Juice industry wastes as a source of bioactives. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 6805–6832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donald, B. Food systems planning and sustainable cities and regions: The role of the firm in sustainable food capitalism. Reg. Stud. 2008, 42, 1251–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfray, H.C.; Beddington, J.R.; Crute, I.R.; Haddad, L.; Lawrence, D.; Muir, J.F.; Pretty, J.; Robinson, S.; Thomas, S.M.; Toulmin, C. Food security: The challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science 2010, 327, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago, E.; Campardelli, R.; Pettinato, M.; Perego, P. Innovations in smart packaging concepts for food: An extensive review. Foods 2020, 9, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualandris, J.; Branzei, O.; Wilhelm, M.; Lazzarini, S.; Linnenluecke, M.; Hamann, R.; Dooley, K.J.; Barnett, M.L.; Chen, C. Unchaining supply chains: Transformative leaps toward regenerating social–ecological systems. J. Suppl. Chain Manag. 2023, 60, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| High-Value, Highly Traceable Products (e.g., Premium Beef, Fine Wine) | Bulk, Storable Commodities (e.g., Wheat, Maize) | Fresh, Perishable Produce (e.g., Strawberries, Leafy Greens) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Technologies | IoT | Application focus: End-to-end precision monitoring. RFID ear-tags or collars track activity, body temperature, transport shocks and tilt to safeguard animal welfare and meat quality [64]. | Application focus: Storage-environment surveillance. Dense networks of temperature-, humidity-, pest- and gas-sensors in granaries prevent mold and quality loss [43,59]. | Application focus: Cold-chain monitoring from field to shelf [61]; real-time temperature, humidity and location data; UAV remote sensing of crop health. |

| Value: Enhances brand narrative and credibility, enabling targeted price premiums [62]. | Value: Reduces post-harvest storage losses and underpins national food security [44]. | Value: Core objective is “freshness preservation” [23,24,25]; markedly lowers spoilage rates and extends shelf-life. | ||

| Blockchain | Application focus: Anti-counterfeiting and full provenance [71,72]. Each item receives a unique digital identity; immutable, time-stamped records cover breed, ranch, abattoir, processing, inspection and logistics. | Application focus: Trade-finance and process automation [44]. Digitizes and automates letters of credit, bills of lading and quality certificates through smart contracts, shortening transaction cycles for bulk agri-trade [42]. | Application focus: Rapid traceability and liability assignment. When food-safety incidents occur, problematic batches are located within minutes, enabling swift recall and limiting losses and panic [74,77]. | |

| Value: Eliminates information asymmetry [80], builds ultimate trust and anchors brand equity. | Value: Raises trade efficiency, cuts transaction costs and mitigates fraud risk [71]. | Value: Protects consumer safety, safeguards brand reputation and satisfies regulatory mandates [51]. | ||

| AI | Application focus: Quality grading and outcome prediction. Computer vision automatically grades marbling, color and carcass weight; AI predicts optimal fattening periods and market-ready dates. | Application focus: Yield and price forecasting. Integrates satellite imagery, meteorological and soil data to predict global output [89,90]; mines massive market datasets to forecast price trends [31,86]. | Application focus: Demand forecasting and intelligent scheduling. Analyses retail data, weather and holiday effects to predict daily demand; optimizes planting plans and logistics routes to curb waste. | |

| Value: Standardizes production and maximizes profit [85]. | Value: Guides governmental and corporate macro-level stocking and policy decisions [83]. | Value: Core aim is “loss reduction”; achieves supply–demand matching and mitigates “produce-dies-at-farm-gate” phenomena [84,87]. | ||

| Main cost drivers | Tag + middleware + certification | Sensor network; platform subscription | Logger hardware; data analytics; cold-chain retrofit. | |

| Key enabling; risk factors | Premium price readily offsets tag cost; needs brand power | Savings from mold/weight-loss cover fee; benefit grows with volume. | Shelf-life extend/waste reduce; smallholders need group-buying to reach MOQ. | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, W.; Li, Z.; Meng, Q. Digital Transformation Drivers, Technologies, and Pathways in Agricultural Product Supply Chains: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10487. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910487

Wang W, Li Z, Meng Q. Digital Transformation Drivers, Technologies, and Pathways in Agricultural Product Supply Chains: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(19):10487. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910487

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Wenhui, Zhen Li, and Qingfeng Meng. 2025. "Digital Transformation Drivers, Technologies, and Pathways in Agricultural Product Supply Chains: A Comprehensive Literature Review" Applied Sciences 15, no. 19: 10487. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910487

APA StyleWang, W., Li, Z., & Meng, Q. (2025). Digital Transformation Drivers, Technologies, and Pathways in Agricultural Product Supply Chains: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Applied Sciences, 15(19), 10487. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910487