A Systematic Literature Review of Building Information Modelling (BIM) and Offsite Construction (OSC) Integration: Emerging Technologies and Future Trends

Abstract

1. Introduction

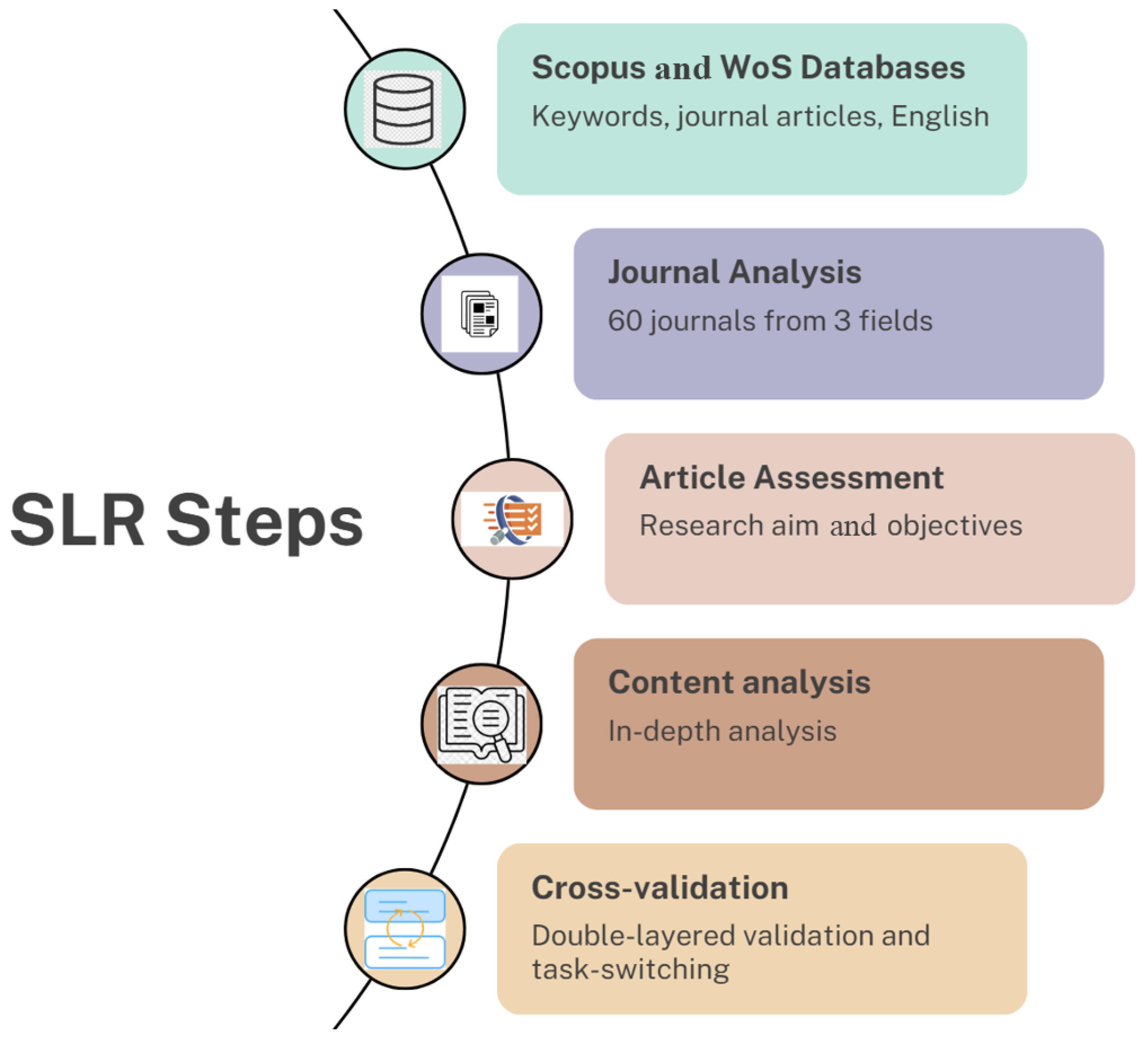

2. Research Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Annual Publications

3.2. Analysis of Methodological Approaches

3.3. Breakdown of Construction Stages

3.4. Analysis of Stakeholders

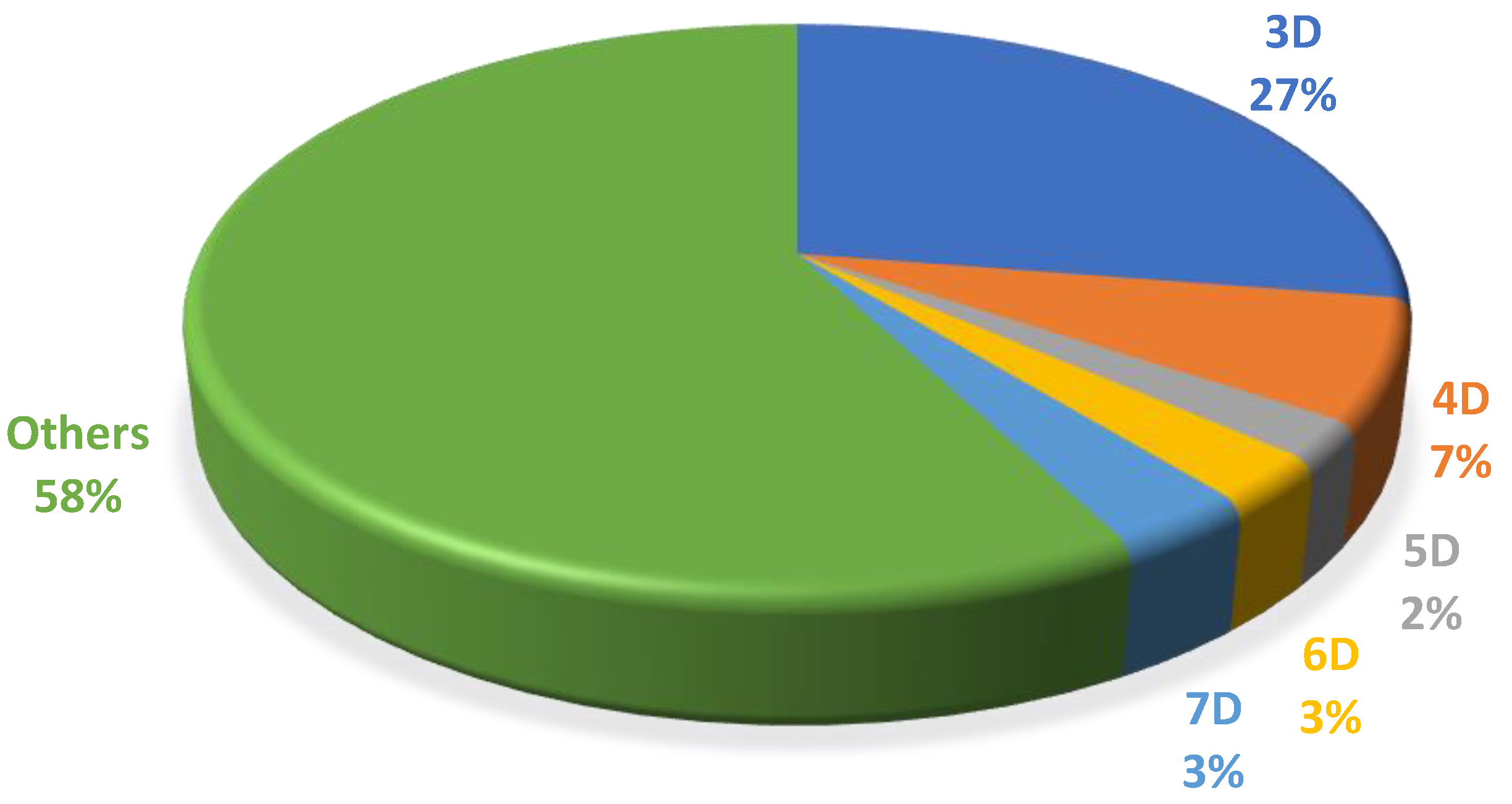

3.5. BIM Dimensions

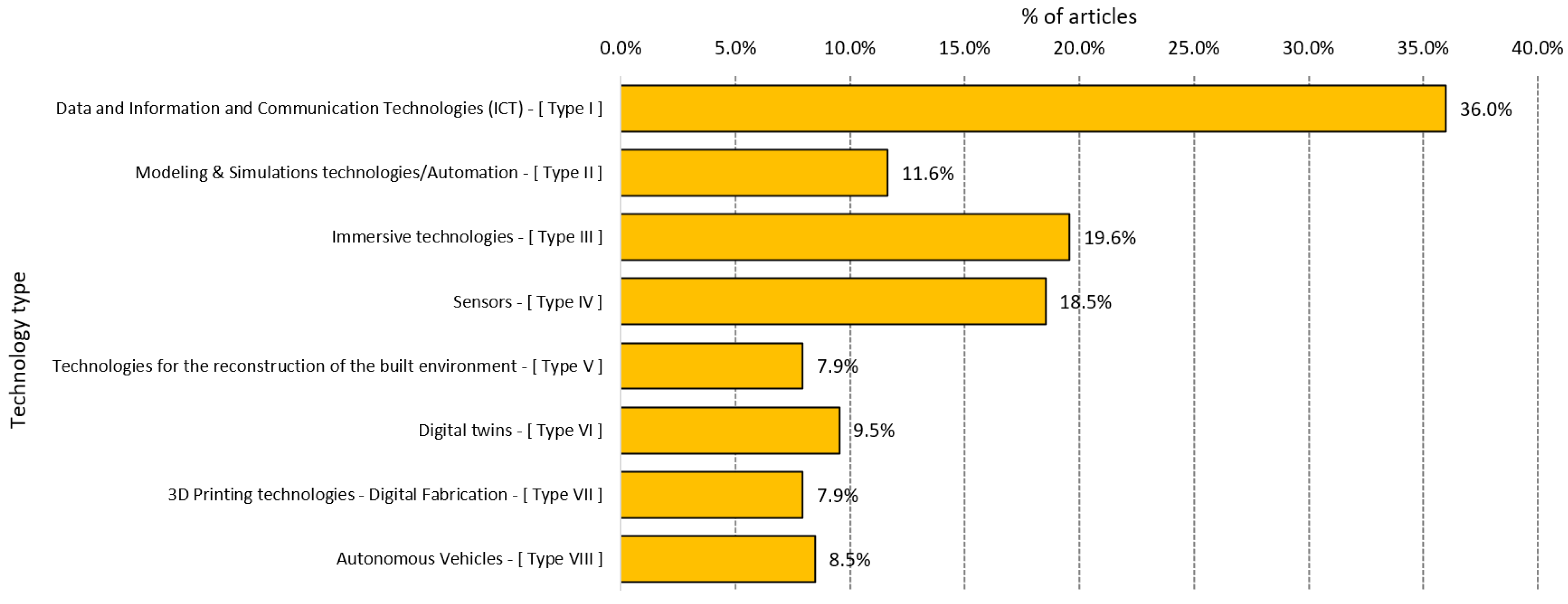

3.6. Advanced Technologies

3.7. Later Lifecycle Stages: Operation, Maintenance, Renovation, and Deconstruction

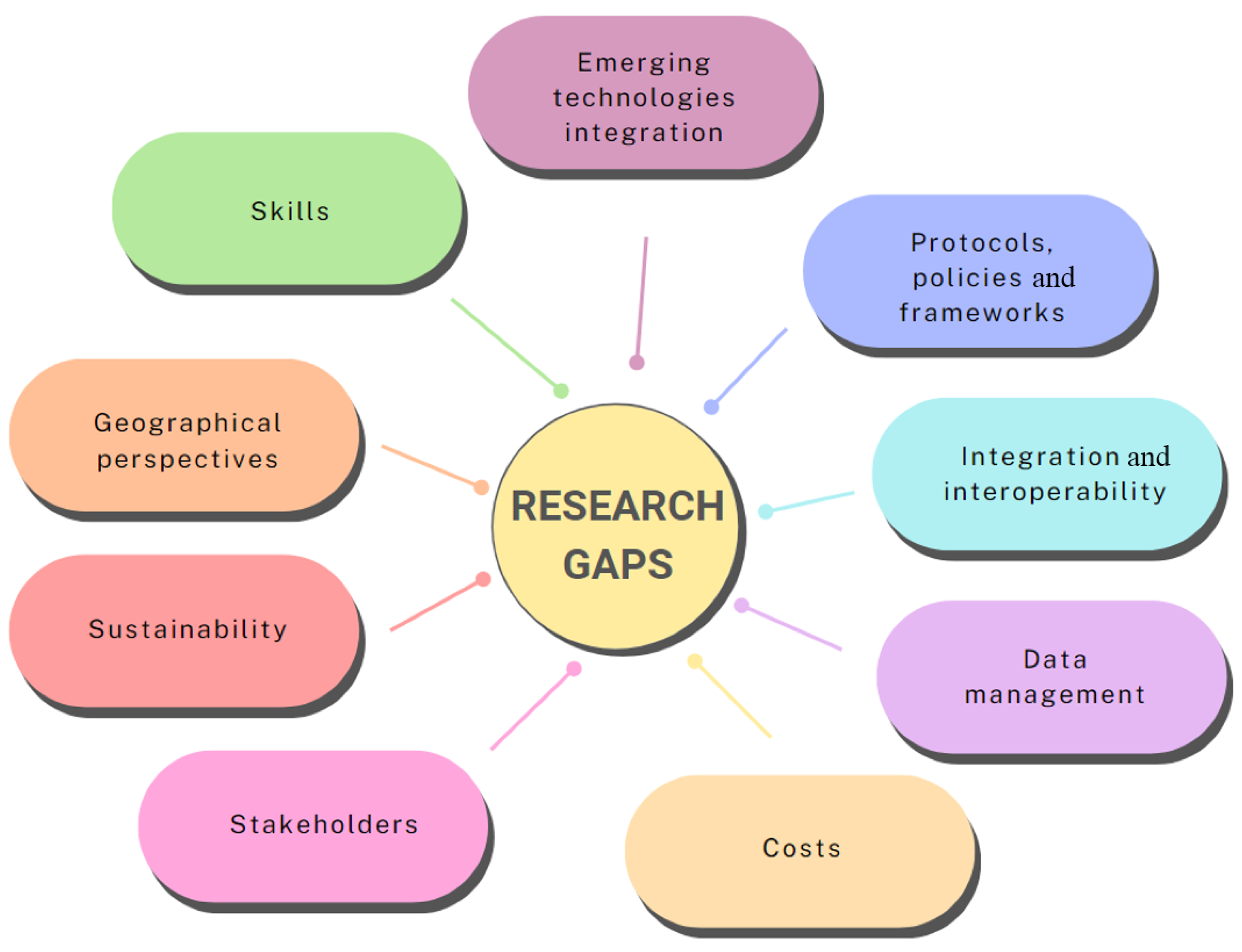

3.8. Challenges and Future Directions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. PRISMA 2020 Checklist

| PRISMA 2020 Checklist Item | Location in Manuscript |

| Title page and Abstract |

| Section 1 (Introduction) |

| Section 1, (Introduction) |

| Section 2: Research Methodology |

| Section 2 |

| Section 2 |

| Section 2 |

| Section 2 |

| Section 3 |

| Section 3 |

| Section 2 (PRISMA Flow), Figure 2 |

| Section 3 |

| Section 4 |

| Section 4 |

References

- Zhu, Z.; Ning, S. Corporate digital transformation and strategic investments of construction industry in China. Heliyon 2023, 9, 17879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abioye, S.O. Artificial intelligence in the construction industry: A review of present status, opportunities and future challenges. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 44, 103299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshi, S. Integrated BIM and DfMA parametric and algorithmic design based collaboration for supporting client engagement within offsite construction. Autom. Constr. 2022, 133, 104015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Tang, S.; Liu, H.; Lei, Z. Digital Technologies in Offsite and Prefabricated Construction: Theories and Applications. Buildings 2023, 13, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginigaddara, B.; Gajendran, T.; Beard, C. A critical review of quantity surveying education in an offsite construction perspective: Strategies for up-skilling. Constr. Innov. 2023, 25, 1058–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofori-Kuragu, J.K.; Osei-Kyei, R. Mainstreaming pre-manufactured offsite processes in construction—Are we nearly there? Constr. Innov. 2021, 21, 743–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuni, I.Y.; Shen, G.Q.P. Holistic Review and Conceptual Framework for the Drivers of Offsite Construction: A Total Interpretive Structural Modelling Approach. Buildings 2019, 9, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vite, C.; Morbiducci, R. Optimizing the Sustainable Aspects of the Design Process through Building Information Modeling. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadehsalehi, S.; Hadavi, A.; Huang, J.C. From BIM to extended reality in AEC industry. Autom. Constr. 2020, 116, 103254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hattab, M. The dynamic evolution of synergies between BIM and sustainability: A text mining and network theory approach. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 37, 102159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiadou, M.C. An overview of benefits and challenges of building information modelling (BIM) adoption in UK residential projects. Constr. Innov. 2019, 19, 298–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obi, L.I. Establishing interrelationships and dependencies of critical success factors for implementing offsite construction in the UK. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2023, 14, 810–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginigaddara, B. Industry 4.0 driven emerging skills of offsite construction: A multi-case study-based analysis. Constr. Innov. 2022, 24, 747–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X. Building information modelling for off-site construction: Review and future directions. Autom. Constr. 2019, 101, 72–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, R.; Lim, J.B.P.; González, V.A. Performance of the supply chains for New Zealand prefabricated house-building. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 64, 102537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, J.; Mesa, H.A.; Alarcón, L.F. The interrelationship between barriers impeding the adoption of off-site construction in developing countries: The case of Chile. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 73, 106824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, L.; Bueno, C. City Information Modelling as a support decision tool for planning and management of cities: A systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis. Build. Environ. 2022, 207, 108403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, K. A systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis based on pricing related decisions in remanufacturing. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 310, 127265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. Impacts of green roofs on water, temperature, and air quality: A bibliometric review. Build. Environ. 2021, 196, 107794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.J.; Broyd, T.; Ma, L. Exploratory literature review of blockchain in the construction industry. Autom. Constr. 2021, 132, 103914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusenbauer, M. Search where you will find most: Comparing the disciplinary coverage of 56 bibliographic databases. Scientometrics 2022, 127, 2683–2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongeon, P.; Paul-Hus, A. The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics 2016, 106, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akomea-Frimpong, I. Green finance for green buildings: A systematic review and conceptual foundation. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 356, 131869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aigwi, I.E.; Duberia, A.; Nwadike, A.N. Adaptive reuse of existing buildings as a sustainable tool for climate change mitigation within the built environment. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 56, 102945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newaz, M.T. A systematic review of contemporary safety management research: A multi-level approach to identifying trending domains in the construction industry. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2023, 41, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, J. Practical implications and future research agenda of lean manufacturing: A systematic literature review. Prod. Plan. Control. 2021, 32, 889–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagwat, K.; Delhi, V.S.K. A systematic review of construction safety research: Quantitative and qualitative content analysis approach. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2022, 12, 243–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Mahmoud, B.; Lehoux, N.; Blanchet, P. Integration mechanisms for material suppliers in the construction supply chain: A systematic literature review. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2023, 42, 70–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Oreiro, I. Standardized Questionnaires for User Experience Evaluation: A Systematic Literature Review. Proceedings 2019, 31, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Bygballe, L.E.; Endresen, M.; Fålun, S. The role of formal and informal mechanisms in implementing lean principles in construction projects. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2018, 25, 1322–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birchall, S.J.; MacDonald, S.; Baran, N.N. An assessment of systems, agents, and institutions in building community resilience to climate change: A case study of Charlottetown, Canada. Urban Clim. 2022, 41, 101062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehwi, R.J. Offsite Manufacturing Research: A Systematic Review of Methodologies Used. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2022, 40, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, P.; Liu, X.; Morrison, G.M. Agent-based modelling and socio-technical energy transitions: A systematic literature review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 49, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Watson, M. Guidance on Conducting a Systematic Literature Review. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2019, 39, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abanda, F.H.; Tah, J.H.M.; Cheung, F.K.T. BIM in off-site manufacturing for buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2017, 14, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, A.; Yong, W.Y.; Maxwell, D.; Fang, Y. Construction planning through 4D BIM-based virtual reality for light steel framing building projects. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2023, 12, 1153–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C. Factors impacting BIM application in prefabricated buildings in China with DEMATEL-ISM. Constr. Innov. 2023, 23, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzeddine, A.; Soto, B.G. Connecting teams in modular construction projects using game engine technology. Autom. Constr. 2021, 132, 103887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El. Reifi, M.H.; Emmitt, S. Perceptions of lean design management. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2013, 9, 195–208. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, B.; Costin, A. BIM and Ontology-Based DfMA Framework for Prefabricated Component. Buildings 2023, 13, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z. Automatic Classification and Coding of Prefabricated Components Using IFC and the Random Forest Algorithm. Buildings 2022, 12, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, S.; Hu, J.; Shi, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, A.; Xie, W. Intelligent Modeling of Edge Components of Prefabricated Shear Wall Structures Based on BIM. Buildings 2023, 13, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marnewick, C.; Labuschagne, L. A conceptual model for enterprise resource planning (ERP). Inf. Manag. Comput. Secur. 2005, 13, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, R.; Chong, H.-Y.; Pereira, C. Obstacles Preventing the Off-Site Prefabrication of Timber and MEP Services: Qualitative Analyses from Builders and Suppliers in Australia. Buildings 2022, 12, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.X. Customization of on-site assembly services by integrating the internet of things and BIM technologies in modular integrated construction. Autom. Constr. 2021, 126, 103663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S. BIM-based decision support system for automated manufacturability check of wood frame assemblies. Autom. Constr. 2020, 111, 103065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, P.; Ahmad, R.; Al-Hussein, M. A vision-based system for pre-inspection of steel frame manufacturing. Autom. Constr. 2019, 97, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Razak, M.I. DfMA for a Better Industrialised Building System. Buildings 2022, 12, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Xiong, F.; Hu, Q.; Liu, R.; Li, S. Incentive Mechanism of BIM Application in Prefabricated Buildings Based on Evolutionary Game Analysis. Buildings 2023, 13, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, Q.; Pons, O. Improving the design and production data flow of a complex curvilinear geometric Glass Reinforced Concrete façade. Autom. Constr. 2014, 38, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, V.J.L.; Liu, T.; Li, K. Integrated BIM and VR for Interactive Aerodynamic Design and Wind Comfort Analysis of Modular Buildings. Buildings 2022, 12, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, V.J.L. BIM-based graph data model for automatic generative design of modular buildings. Autom. Constr. 2022, 134, 104062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tak, A.N. BIM-based 4D mobile crane simulation and onsite operation management. Autom. Constr. 2021, 128, 103766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L. BIM4D-based scheduling for assembling and lifting in precast-enabled construction. Autom. Constr. 2022, 133, 103999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S. Automated verification of 3D manufacturability for steel frame assemblies. Autom. Constr. 2020, 118, 103287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Dong, W.; Huang, Y. A Bim-Based Automatic Design Optimization Method for Modular Steel Structures: Rectangular Modules as an Example. Buildings 2023, 13, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noghabaei, M.; Liu, Y.; Han, K. Automated compatibility checking of prefabricated components using 3D as-built models and BIM. Autom. Constr. 2022, 143, 104566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y. Safety Risk Management of Prefabricated Building Construction Based on Ontology Technology in the BIM Environment. Buildings 2022, 12, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q. Labor crew workspace analysis for prefabricated assemblies’ installation. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2018, 25, 374–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, T.; Salah, A.; Moselhi, O. Integrating critical chain project management with last planner system for linear scheduling of modular construction. Constr. Innov. 2021, 21, 525–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbadamosi, A.-Q. Big data for Design Options Repository: Towards a DFMA approach for offsite construction. Autom. Constr. 2020, 120, 103388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Lee, G. Process, productivity, and economic analyses of BIM–based multi-trade prefabrication—A case study. Autom. Constr. 2018, 89, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Liu, Z.; Mbachu, J. Optimization of the Supplier Selection Process in Prefabrication Using BIM. Buildings 2019, 9, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, V.; Freire, F. Life cycle assessment of a prefabricated house for seven locations in different climates. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 53, 104504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.J.; Xie, W.J.; Xu, L.; Li, L.L.; Jim, C.Y.; Wei, T.B. Holistic life-cycle accounting of carbon emissions of prefabricated buildings using LCA and BIM. Energy Build. 2022, 266, 112136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniotti, B. The Development of a BIM-Based Interoperable Toolkit for Efficient Renovation in Buildings: From BIM to Digital Twin. Buildings 2022, 12, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-La Rivera, F. Methodological-Technological Framework for Construction 4.0. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2021, 28, 689–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L. Intelligent data-driven approach for enhancing preliminary resource planning in industrial construction. Autom. Constr. 2021, 130, 103846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feist, S. Semi-Supervised Clustering for Architectural Modularisation. Buildings 2022, 12, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wusu, G.E. A machine learning approach for predicting critical factors determining adoption of offsite construction in Nigeria. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2022, 13, 1408–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkokebas, B.; Martinez, P.; Bouferguene, A.; Hamzeh, F.; Al-Hussein, M. Digitalization-based process improvement and decision-making in offsite construction. Autom. Constr. 2023, 155, 105052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, B.; Lin, Y. Fine-grained progress tracking of prefabricated construction based on component segmentation. Autom. Constr. 2024, 160, 105329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikudayisi, A.E.; Chan, A.P.C.; Darko, A.; Adedeji, Y.M.D. Integrated practices in the Architecture, Engineering, and Construction industry: Current scope and pathway towards Industry 5.0. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 73, 106788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Hua, Y.; Wang, H. Mapping the digital transformation of AEC industry: Content analysis of digital public policy in China. Dev. Built Environ. 2025, 21, 100621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J.; Li, K.; Li, X.; Mok, E.; Ho, P.; Law, J.; Lau, J.; Kwok, R.; Yau, R. Parametric BIM-Based Lifecycle Performance Prediction and Optimisation for Residential Buildings Using Alternative Materials and Designs. Buildings 2023, 13, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Gao, S. Construction 4.0 technology and lean construction ambidexterity capability in China’s construction industry: A sociotechnical systems perspective. Constr. Innov. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ametepey, S.O.; Aigbavboa, C.; Addy, H.; Thwala, W.D. A Bibliometric Review of the Trends of Construction Digitalization Research in the Past Ten Years. Buildings 2024, 14, 2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghansah, F.; Edwards, D. Digital Technologies for Quality Assurance in the Construction Industry: Current Trend and Future Research Directions towards Industry 4.0. Buildings 2024, 14, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, L.; Liu, P.; Cheng, G.; Chen, Y. Intelligent floor plan design of modular high-rise residential building based on graph-constrained generative adversarial networks. Autom. Constr. 2024, 159, 105264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Yang, B.; Liu, B. Precast components on-site construction planning and scheduling method based on a novel deep learning integrated multi-agent system. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 102, 111907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yi Man Li, R.; Deeprasert, J. The Impact of BIM Technology on the Lifecycle Cost Control of Prefabricated Buildings: Evidence from China. Buildings 2024, 14, 3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, B.P.Y.; Wong, R.W.M. Towards a Conceptual Framework of Using Technology to Support Smart Construction: The Case of Modular Integrated Construction (MiC). Buildings 2023, 13, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Shu, J.; Ye, J.; Zhao, W. Virtual trail assembly of prefabricated structures based on point cloud and BIM. Autom. Constr. 2023, 155, 105049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Cao, X. An intelligent framework for rework risk identification in prefabricated construction processes based on compliance checking. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Chen, L.; Wei, G.; Zhang, J.; Guo, P.; Wang, H.; Zhao, J.; Huang, W. Technology Gap Analysis on the BIM-Enabled Design Process of Prefabricated Buildings: An Autoethnographic Study. Buildings 2024, 14, 3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widanage, C.; Kim, K.P. Integrating Design for Manufacture and Assembly (DfMA) with BIM for infrastructure. Autom. Constr. 2024, 167, 105705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangasamy, V.; Yang, J.-B. The convergence of BIM, AI and IoT: Reshaping the future of prefabricated construction. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 84, 108606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.-E.; Kim, I.; Kim, J.I.; Cha, S.H. Client-engaged collaborative pre-design framework for modular housing. Autom. Constr. 2023, 156, 105123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, T.W.; Chang, S. Comprehensive evaluation of digital technology’s effects on the supply chain of prefabricated construction. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K. Enhancing healthcare facility resilience: Utilizing machine learning model for airborne disease infection prediction. J. Build. Perform. Simul. 2024, 17, 679–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solihin, W.; Liu, Z.; Lu, Y.; Wei, L. BIM-based automated rule-checking in the AECO industry: Learning from semiconductor manufacturing. Autom. Constr. 2024, 162, 105406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Teng, Y.; Pan, W. Integrating IoT and BIM for tracking and visualising embodied carbon of prefabricated buildings. Build. Environ. 2023, 242, 110492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshref, A.N.; Ibrahim, A. A dynamic approach for investigating design approaches to reducing construction waste in healthcare projects. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 95, 110092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordestani, N.; Babaeian Jelodar, M.; Paes, D.; Sutrisna, M.; Rahmani, D. A comprehensive evaluation of factors influencing offsite construction and BIM integration in the construction industry. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandín, R.; Abrishami, S. IoT-BIM and blockchain integration for enhanced data traceability in offsite manufacturing. Autom. Constr. 2024, 159, 105266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, K.E. Surveying and digital workflow in energy performance retrofit projects using prefabricated elements. Autom. Constr. 2011, 20, 999–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandín, R.; Abrishami, S. Information traceability platforms for asset data lifecycle: Blockchain-based technologies. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2021, 10, 364–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D. Integrated digital twin and blockchain framework to support accountable information sharing in construction projects. Autom. Constr. 2021, 127, 103688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.-C.; Jeon, C.-H.; Roh, G.; Shim, C. BIM-based preassembly analysis for design for manufacturing and assembly of prefabricated bridges. Autom. Constr. 2024, 160, 105338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tao, X.; Das, M.; Gong, X.; Liu, H.; Xu, Y.; Xie, A.; Cheng, J.C.P. Blockchain-enabled platform-as-a-service for production management in off-site construction design using openBIM standards. Autom. Constr. 2024, 164, 105447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, S.; Cai, J.; Han, Z. BIM-blockchain integrated automatic asset tracking and delay propagation analysis for prefabricated construction projects. Autom. Constr. 2024, 168, 105854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.Y. Prefabricated construction enabled by the Internet-of-Things. Autom. Constr. 2017, 76, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piroozfar, P. Configuration platform for customisation of design, manufacturing and assembly processes of building façade systems: A building information modelling perspective. Autom. Constr. 2019, 106, 102914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minunno, R. Strategies for Applying the Circular Economy to Prefabricated Buildings. Buildings 2018, 8, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhu, A.; Xu, G.; Shao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H. FEM-based real-time task planning for robotic construction simulation. Autom. Constr. 2025, 170, 105935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anane, W.; Iordanova, I.; Ouellet-Plamondon, C. BIM-driven computational design for robotic manufacturing in off-site construction: An integrated Design-to-Manufacturing (DtM) approach. Autom. Constr. 2023, 150, 104782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, N.; Ahmad, R.; Al-Hussein, M. Generation of safe tool-paths for automatic manufacturing of light gauge steel panels in residential construction. Autom. Constr. 2019, 98, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong Chong, O.; Zhang, J. Logic representation and reasoning for automated BIM analysis to support automation in offsite construction. Autom. Constr. 2021, 129, 103756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitterhofer, M. An FMI-enabled methodology for modular building performance simulation based on Semantic Web Technologies. Build. Environ. 2017, 125, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, Q.; Park, J.-H. Geometric quality inspection of prefabricated MEP modules with 3D laser scanning. Autom. Constr. 2020, 111, 103053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q. Using look-ahead plans to improve material flow processes on construction projects when using BIM and RFID technologies. Constr. Innov. 2020, 20, 471–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, A.; Pauwels, P.; Vries, B. Smart component-oriented method of construction robot coordination for prefabricated housing. Autom. Constr. 2021, 129, 103778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, J.L. An IFC Interoperability Framework for Self-Inspection Process in Buildings. Buildings 2018, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Building information modeling-based integration of MEP layout designs and constructability. Autom. Constr. 2016, 61, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. A Systematic Review of Digital Technology Adoption in Off-Site Construction: Current Status and Future Direction towards Industry 4.0. Buildings 2020, 10, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A. Integration of BIM and Immersive Technologies for AEC: A Scientometric-SWOT Analysis and Critical Content Review. Buildings 2021, 11, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Cao, C.; Liu, Z. A Framework for Prefabricated Component Hoisting Management Systems Based on Digital Twin Technology. Buildings 2022, 12, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Integrating Building Information Modeling and Prefabrication Housing Production. Autom. Constr. 2019, 100, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhuang, J. Research on the green development path of prefabricated building industry based on intelligent technology. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Ding, Z.; Niu, J.; Zhang, L.; Liao, L. A Digital Project Management Framework for Transnational Prefabricated Housing Projects. Buildings 2024, 14, 2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Gan, V.J.L.; Li, M.; Gao, M.Y.; Tiong, R.L.K.; Yang, Y. Automated generative design and prefabrication of precast buildings using integrated BIM and graph convolutional neural network. Dev. Built Environ. 2024, 18, 100418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; Chen, S.; Zhao, X.; Sun, Z.; Fan, X.; Zhang, M.; Huang, L.; et al. A Review of Life Cycle Construction Process and Cutting-Edge Technology in Prefabricated MEP Installation Engineering. Buildings 2024, 14, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordestani Ghalenoei, N.; Babaeian Jelodar, M.; Paes, D.; Sutrisna, M. Challenges of offsite construction and BIM implementation: Providing a framework for integration in New Zealand. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2024, 13, 780–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ergan, S.; Zhang, Q. An AprilTags-Based Approach for Progress Monitoring and Quality Control in Modular Construction. Buildings 2024, 14, 2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosbar, M.M.; Elbeltagi, E.; Mahdi, I.; Kassem, M.; Ehab, A. Off-Site Manufacturing: Determining Decision-Making Factors. Buildings 2023, 13, 2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D. Automatic modeling of prefabricated components with laser-scanned data for virtual trial assembly. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2021, 36, 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, M.M.; Haas, C.; Walbridge, S. Using termination points and 3D visualization for dimensional control in prefabrication. Autom. Constr. 2022, 133, 103998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-K. Automated dimensional quality assurance of full-scale precast concrete elements using laser scanning and BIM. Autom. Constr. 2016, 72, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, D.-H.; Roh, G.-T.; Jeon, C.-H.; Shim, C.-S. Simulation-Based Optimization of Crane Lifting Position and Capacity Using a Construction Digital Twin for Prefabricated Bridge Deck Assembly. Buildings 2025, 15, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.Q.; Chen, X.L.; Ninić, J.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, Q.B. A framework for integrating embodied carbon assessment and construction feasibility in prefabricated stations. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 132, 104920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Aridah, D.; Henn, R.L. Construction 4.0 in Refugee Camps: Facilitating Socio-Spatial Adaptation Patterns in Jordan’s Zaatari Camp. Buildings 2024, 14, 2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Placzek, G.; Schwerdtner, P. A Global Snapshot of 3D-Printed Buildings: Uncovering Robotic-Oriented Fabrication Strategies. Buildings 2024, 14, 3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, P.; Dahanayake, K.C.; Sumanarathna, N. Exploring UAE’s transition towards circular economy through construction and demolition waste management in the pre-construction stage–A case study approach. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2024, 13, 246–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Dani, A.A.; Lim, J.B.P.; Roy, K. Appraising the Feasibility of 3D Printing Construction in New Zealand Housing. Buildings 2024, 14, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, N.M.; Alashwal, A. Developing a model for the implementation of designing out waste in construction. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2025, 21, 154–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, S.; Bock, T.; Stoliar, Y. A methodology for the optimal modularization of building design. Autom. Constr. 2016, 65, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paskoff, C.; Boton, C.; Blanchet, P. BIM-Based Checking Method for the Mass Timber Industry. Buildings 2023, 13, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montazeri, S.; Odo, N.; Naqvi, S.A.W.; Lei, Z. Integrating Design for Manufacturing and Assembly Principles in Modular Home Construction: A Comprehensive Framework for Enhanced Efficiency and Sustainability. Buildings 2024, 15, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusmao Brissi, S. A review on the interactions of robotic systems and lean principles in offsite construction. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2022, 29, 383–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, A.; Pauwels, P.; De Vries, B. Component-based robot prefabricated construction simulation using IFC-based building information models. Autom. Constr. 2023, 152, 104899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Gu, Y.; Xie, L.; Huang, Z. Automatic assembly of prefabricated components based on vision-guided robot. Autom. Constr. 2024, 162, 105385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, H.; Zhang, H.; Huang, B.; Gong, Y. BIM-Based Digital Construction Strategies to Evaluate Carbon Emissions in Green Prefabricated Buildings. Buildings 2024, 14, 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, Y.; Udawatta, N.; Liu, C.; Tokede, O. Circular Economy-Related Strategies to Minimise Construction and Demolition Waste Generation in Australian Construction Projects. Buildings 2024, 14, 2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Fomin, N.I.; Li, S.; Hu, W.; Xiao, S.; Huang, Y.; Liu, C. Life Cycle Carbon Emission Analysis of Buildings with Different Exterior Wall Types Based on BIM Technology. Buildings 2025, 15, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xie, W.; Yang, T.; Lin, C.; Jim, C.Y. Carbon emission evaluation of prefabricated concrete composite plates during the building materialization stage. Build. Environ. 2023, 232, 110045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.; Quintana-Gallardo, A.; Martí Audí, N.; Guillén Guillamón, I. The impact of lifespan assumptions in LCA: Comparing the replacement of building parts versus building layers—A housing case study. Energy Build. 2025, 326, 115050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, S.; Vilgertshofer, S.; Borrmann, A. Version control for asynchronous BIM collaboration: Model merging through graph analysis and transformation. Autom. Constr. 2023, 155, 105063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhu, H. A Semantic-Based Methodology to Deliver Model Views of Forward Design for Prefabricated Buildings. Buildings 2022, 12, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Shi, Y.; Hu, J.; Li, S.; Li, H.; Chen, A.; Xie, W. Application of BIM to Rebar Modeling of a Variable Section Column. Buildings 2023, 13, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, L.; Blanchet, P.; Bégin-Drolet, A. On-site handling: Automated connecting device for modular construction used as lifting apparatus. Structures 2024, 63, 106318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Gao, X.; Chen, S.; Li, Q.; Bai, S. A 3D Parameterized BIM-Modeling Method for Complex Engineering Structures in Building Construction Projects. Buildings 2024, 14, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Zheng, X.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, C. Automated Prefabricated Slab Splitting Design Using a Multipopulation Coevolutionary Algorithm and BIM. Buildings 2024, 14, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliu, L.O.; Monko, R.; Zulu, S.; Maro, G. Barriers to the Integration of Building Information Modeling (BIM) in Modular Construction in Sub-Saharan Africa. Buildings 2024, 14, 2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wang, X.; Chen, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, J. Research on Integrated Design of Prefabricated Steel Frame Structures Based on BIM Technology with a Focus on Structural Safety. Buildings 2024, 14, 2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, E.M.; Martinez, P.; Ahmad, R. Target-path planning and manufacturability check for robotic CLT machining operations from BIM information. Autom. Constr. 2024, 158, 105191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, Q. Development of a Cloud-Based Building Information Modeling Design Configurator to Auto-Link Material Catalogs with Code-Compliant Designs of Residential Buildings. Buildings 2024, 14, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Mahmoud, B. Barriers, Strategies, and Best Practices for BIM Adoption in Quebec Prefabrication Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs. Buildings 2022, 12, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q. Exploiting digitalization for the coordination of required changes to improve engineer-to-order materials flow management. Constr. Innov. 2021, 22, 76–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Pan, M. Rethinking lean synergistically in practice for construction industry improvements. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2022, 30, 2669–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensalah, M.; Elouadi, A.; Mharzi, H. Overview: The opportunity of BIM in railway. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2019, 8, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babič, N.Č.; Podbreznik, P.; Rebolj, D. Integrating resource production and construction using BIM. Autom. Constr. 2010, 19, 539–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-C.; Eastman, C.M.; Lee, J.-K. Validations for ensuring the interoperability of data exchange of a building information model. Autom. Constr. 2015, 58, 176–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, R. Project-based pedagogy in interdisciplinary building design adopting BIM. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2018, 25, 1376–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolini, R.; Formoso, C.T.; Viana, D.D. Site logistics planning and control for engineer-to-order prefabricated building systems using BIM 4D modeling. Autom. Constr. 2019, 98, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B. A novel construction scheduling framework for a mixed construction process of precast components and cast-in-place parts in prefabricated buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 43, 103181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Sun, C.; Wang, Y. Design for Manufacture and Assembly-oriented parametric design of prefabricated buildings. Autom. Constr. 2018, 88, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkokebas, B. A BIM-lean framework for digitalisation of premanufacturing phases in offsite construction. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2021, 28, 2155–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Li, X.; Chen, S.; Chen, D.; Lin, J. Review and prediction: Carbon emissions from the materialization of residential buildings in China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 121, 106211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, X. Automated component delivery management under uncertainty for prefabricated buildings to minimize cost and harmful emissions. Autom. Constr. 2024, 162, 105388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Chen, L.; Huang, M.; Li, J.; Zhang, G. Automated geometric quality inspection for modular boxes using BIM and LiDAR. Autom. Constr. 2024, 164, 105474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Lv, J.; Li, H.X.; Liu, Y.; Yao, F.; Liu, X.; Wang, S. Improving the performance of prefabricated houses through multi-objective optimization design. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 84, 108579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoori, S.; Harkonen, J.; Haapasalo, H. Productization and product structure enabling BIM implementation in construction. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2023, 30, 2155–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Roh, S.; Kim, J. Embodied carbon of BIM bridge models according to the application of off-site prefabrication: Precast concrete applied to superstructure and substructure. Dev. Built Environ. 2024, 20, 100550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Zhang, H.; Hei, S.; Huang, B.; He, R.; Chai, X.; Shao, Z. A Component-Design-Based Carbon Emission Calculation Method in the Life Cycle of a Prefabricated Building Structural Member System. Buildings 2024, 14, 3994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. BIM-BVBS integration with openBIM standards for automatic prefabrication of steel reinforcement. Autom. Constr. 2021, 125, 103654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Q.; Dong, S.; Cao, Y.; Wang, L. Facilitating Circular Transition in the Construction Industry: Optimizing a Prefabricated Construction Site Layout Using a Novel BIM-Integrated SLP-GA Model. Buildings 2024, 14, 2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yang, Q.; Yan, G.; Fan, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, S. Length Optimization of MEP Pipeline Integrated Modular Based on Genetic Algorithm. Buildings 2024, 14, 3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovic, D.; Elgh, F.; Heikkinen, T. Configuration of flexible volumetric elements using product platforms: Information modeling method and a case study. Autom. Constr. 2021, 126, 103661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atta, I.; Bakhoum, E.S.; Marzouk, M.M. Digitizing material passport for sustainable construction projects using BIM. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 43, 103233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krantz, J. Assessing Embodied Energy and Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Infrastructure Projects. Buildings 2015, 5, 1156–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceranic, B.; Beardmore, J.; Cox, A. Rapid deployment modular building solutions and climatic adaptability: Case based study of a novel approach to “thermal capacity on demand”. Energy Build. 2018, 167, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekouvaght Tak, A. Evaluating industrial modularization strategies: Local vs. overseas fabrication. Autom. Constr. 2020, 114, 103175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalhoub, J.; Ayer, S.K. Using Mixed Reality for electrical construction design communication. Autom. Constr. 2018, 86, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili-Araghi, S.; Kolarevic, B. Variability and validity: Flexibility of a dimensional customization system. Autom. Constr. 2020, 109, 102970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, B.N.; London, K.; Zhang, P. Stakeholder relationships in off-site construction: A systematic literature review. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2022, 11, 765–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamoozian, M.; Zhang, H. Pushing the boundaries of prefabricated shell building design with building information modeling (BIM) and ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC). Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, C.; Kim, J.-I.; Kim, I.; Yu, J. Comparison of OSC (Off-Site Construction) Level Measurement Methods. Buildings 2024, 14, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.; Mills, G.; Ma, X.; Papadonikolaki, E. Adoption Challenges of Building Information Modelling (BIM) and Off-Site Construction (OSC) in Healthcare Construction: Are They Fellow Sufferers? Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024, 31, 390–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfieri, E. A BIM-based approach for DfMA in building construction: Framework and first results on an Italian case study. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2020, 16, 247–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y. BIM-based life-cycle environmental assessment of prefabricated buildings. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2020, 27, 1703–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarasinghe, T. Dependency Structure Matrix and Hierarchical Clustering based algorithm for optimum module identification in MEP systems. Autom. Constr. 2019, 104, 153–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginigaddara, B. Offsite construction skills evolution: An Australian case study. Constr. Innov. 2021, 22, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Technology Types | Technologies | Descriptions | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type I—Data and ICT | AI and ML | Optimizes resource planning, decision-making, and automation. | [4,41,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90] |

| Data exchange/(CDE) | Ensures consistent, up-to-date project data across stakeholders and integrates diverse formats, enhancing collaboration and interoperability. | [4,73,74,76,82,91,92,93,94,95] | |

| Cloud computing | Enables scalable, real-time data sharing and collaboration, ensuring stakeholders access the latest prefabrication and construction information. | [4,73,74,76,82,91,92,93,94,95,96] | |

| Blockchain | Secures, tracks, and manages project data across its lifecycle, ensuring transparency and trust in OSC supply chains. | [73,74,77,78,82,95,97,98,99,100,101] | |

| Big data | Handles large datasets generated by IoT-enabled OSC projects to support predictive analysis and improve decision-making. | [74,78,96,102,103] | |

| ICT | Customises design, manufacturing, and assembly through integrated digital configuration platforms. | [103,104] | |

| Type II—Modelling and simulation | 3D/4D/5D BIM Modelling | Enhances visualisation, cost control, and project planning. | [42,49,51,54,56,62,90,105,106,107,108] |

| HPC | Accelerates design simulations and prefabrication modelling. | [109,110,111,112] | |

| Type III—Immersive technologies | VR/AR/MR | Supports constructability verification, inspection, and design reviews. | [4,14,62,73,74,78,86,87,106,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120] |

| Type IV—Sensing and monitoring | IoT Sensors | Enables real-time tracking of prefabrication and onsite assembly. | [9,73,74,76,77,78,82,86,87,89,92,97,98,102,117,118,119,120,121] |

| RFID | Improves material monitoring and component tracking. | [14,49,71,81,82,92,115,119,121,122,123,124] | |

| Type V—Reconstruction tools | Laser scanning | Provides accurate 3D measurements for geometry verification. | [14,78,83,86,89,96,99,110,113,115,122,124,125,126,127,128] |

| Photogrammetry | Generates precise models from images for quality checks. | [125] | |

| Type VI—Digital twins | Digital twins | Integrates real-time data with BIM for dynamic lifecycle monitoring. | [66,73,74,76,77,78,86,98,117,120,123,129,130,131] |

| Type VII—3D Printing and fabrication | 3D Printing | Produces prefabricated components with higher precision. | [14,82,87,131,132,133,134,135,136] |

| CNC | Automates precision manufacturing of modular components, reducing human error and enabling seamless assembly. | [137,138] | |

| Type VIII—Autonomous vehicles | UAVs (drones) | Assists in site inspections, prefabricated element placement, and installation logistics with aerial monitoring. | [129,139] |

| Robots | Automates repetitive prefabrication tasks to enhance consistency, speed, and accuracy of modular manufacturing. | [4,73,76,77,82,87,105,106,107,122,136,140,141] | |

| Automatic guided vehicles (AGVs) | Transports modular components between production, storage, and installation points, improving onsite efficiency and safety. | [137] |

| Challenge Area | Focus in Reviewed Studies | Future Research Directions |

|---|---|---|

| i. Emerging Technologies | Integration of generative design, blockchain, AR/VR, IoT, and other Industry 4.0 tools. | Develop holistic frameworks combining these technologies and test their real-world applications. |

| ii. Protocols and Frameworks | Lack of standardised protocols, coding systems, and regulatory policies for OSC-BIM. | Establish international standards, shared ontologies, and common data formats for seamless implementation. |

| iii. Integration and Interoperability | Difficulties integrating proposed solutions and emerging technologies with traditional workflows. | Enhance cross-platform interoperability, adopt lean-driven approaches, and optimize assembly sequencing. |

| iv. Data Management | Challenges in big data collection, compatibility checks, and secure data sharing. | Explore blockchain, cloud computing, and big data analytics to automate and improve data precision. |

| v. Costs | High costs and limited cost–benefit analyses for OSC-BIM solutions. | Conduct lifecycle cost studies, assess macroeconomic impacts, and evaluate carbon trading policies. |

| vi. Stakeholders | Limited collaboration between contractors, designers, manufacturers, and regulators. | Develop collaborative platforms, virtual environments, and real-time shared ecosystems. |

| vii. Sustainability | Limited exploration of environmental and social impacts of BIM-OSC integration; focus is mostly on design, manufacturing, and construction phases, with limited research on operation, maintenance, and deconstruction. | Expand comparative LCAs, assess carbon trading impacts, and explore BIM-OSC integration for facility management, predictive maintenance, adaptive reuse, and sustainable deconstruction to support whole-lifecycle sustainability. |

| viii. Geographical Aspects | Uneven adoption of OSC-BIM integration across regions. | Investigate localized barriers, regional best practices, and develop scalable solutions. |

| ix. Skills Development | Lack of training and digital competencies among professionals managing OSC-BIM projects. | Create training programs, industry–academia collaborations, and digital upskilling frameworks. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Doan, D.T.; Atencio, E.; Muñoz La Rivera, F.; Alnajjar, O. A Systematic Literature Review of Building Information Modelling (BIM) and Offsite Construction (OSC) Integration: Emerging Technologies and Future Trends. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9981. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15189981

Doan DT, Atencio E, Muñoz La Rivera F, Alnajjar O. A Systematic Literature Review of Building Information Modelling (BIM) and Offsite Construction (OSC) Integration: Emerging Technologies and Future Trends. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(18):9981. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15189981

Chicago/Turabian StyleDoan, Dat Tien, Edison Atencio, Felipe Muñoz La Rivera, and Omar Alnajjar. 2025. "A Systematic Literature Review of Building Information Modelling (BIM) and Offsite Construction (OSC) Integration: Emerging Technologies and Future Trends" Applied Sciences 15, no. 18: 9981. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15189981

APA StyleDoan, D. T., Atencio, E., Muñoz La Rivera, F., & Alnajjar, O. (2025). A Systematic Literature Review of Building Information Modelling (BIM) and Offsite Construction (OSC) Integration: Emerging Technologies and Future Trends. Applied Sciences, 15(18), 9981. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15189981