Oral Involvement and Pain Among Pemphigus Vulgaris Patients as a Clinical Indicator for Management—An Epidemiological and Clinical Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Data Recorded

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Diagnostic Delay

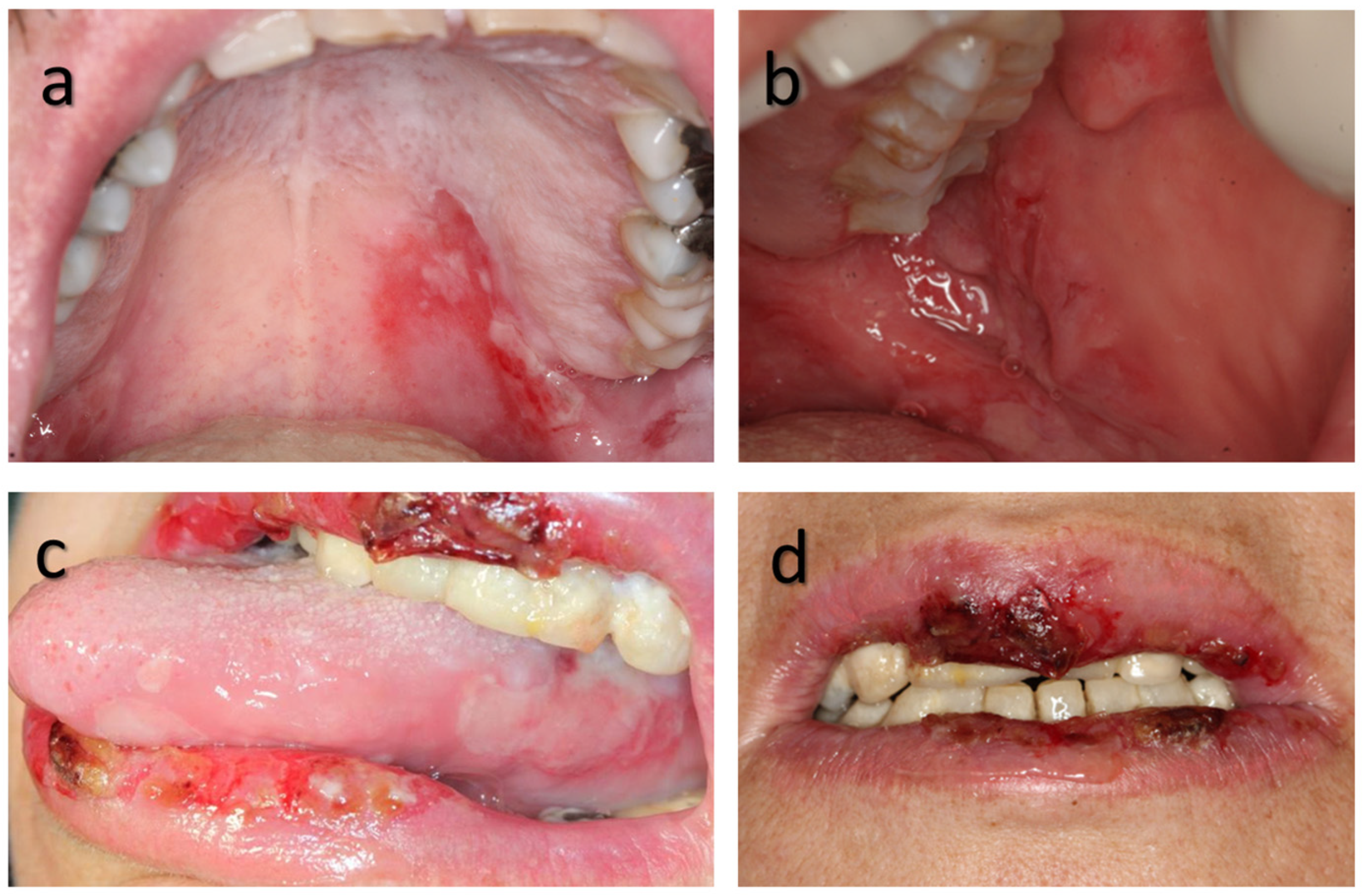

3.3. Clinical Characteristics and Pain at First Visit

3.4. Treatment/Hospitalization

3.5. Oral Involvement and Disease Outcome/Severity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PV | Pemphigus Vulgaris |

| VAS | Verbal Analogue Scale |

| FOM | Floor of Mouth |

References

- Joly, P.; Litrowski, N. Pemphigus group (vulgaris, vegetans, foliaceus, herpetiformis, brasiliensis). Clin. Dermatol. 2011, 29, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellebrecht, C.T.; Maseda, D.; Payne, A.S. Pemphigus and Pemphigoid: From Disease Mechanisms to Druggable Pathways. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 142, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kridin, K. Pemphigus group: Overview, epidemiology, mortality, and comorbidities. Immunol. Res. 2018, 66, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirois, D.A.; Fatahzadeh, M.; Roth, R.; Ettlin, D. Diagnostic patterns and delays in pemphigus vulgaris: Experience with 99 patients. Arch. Dermatol. 2000, 136, 1569–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arduino, P.G.; Broccoletti, R.; Carbone, M.; Gambino, A.; Sciannameo, V.; Conrotto, D.; Cabras, M.; Sciascia, S.; Ricceri, F.; Baldovino, S.; et al. Long-term evaluation of pemphigus vulgaris: A retrospective consideration of 98 patients treated in an oral medicine unit in north-west Italy. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2019, 48, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murrell, D.F.; Peña, S.; Joly, P.; Marinovic, B.; Hashimoto, T.; Diaz, L.A.; Sinha, A.A.; Payne, A.S.; Daneshpazhooh, M.; Eming, R.; et al. Diagnosis and management of pemphigus: Recommendations of an international panel of experts. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 82, 575–585.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.I.; Kim, J.W.; Lim, J.S.; Chung, J.H. Mucosal involvement is a risk factor for poor clinical outcomes and relapse in patients with pemphigus treated with rituximab. Dermatol. Ther. 2019, 32, e12814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hietanen, J.; Salo, O. Pemphigus: An epidemiological study of patients treated in Finnish hospitals between 1969 and 1978. Acta Derm.-Venereol. 1982, 62, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kridin, K.; Zelber-Sagi, S.; Bergman, R. Pemphigus Vulgaris and Pemphigus Foliaceus: Differences in Epidemiology and Mortality. Acta Derm.-Venereol. 2017, 97, 1095–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, B.D.; Damm, D.D.; Allen, C.M.; Chi, A.C. Pemphigus vulgaris in:Dermatologic Diseases. In Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, 5th ed.; Elsevier: Maryland Heights, MO, USA, 2024; pp. 747–819. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, E.; Kasperkiewicz, M.; Joly, P. Pemphigus. Lancet 2019, 394, 882–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, K.; Chatterjee, D.; Mahajan, R.; Handa, S.; De, D. Direct immunofluorescence on plucked hair outer root sheath can predict relapse in pemphigus vulgaris. Int. J. Dermatol. 2024, 64, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kridin, K.; Schmidt, E. Epidemiology of Pemphigus. JID Innov. 2021, 1, 100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daltaban, Ö.; Özçentik, A.; Karakaş, A.A.; Üstün, K.; Hatipoğlu, M.; Uzun, S. Clinical presentation and diagnostic delay in pemphigus vulgaris: A prospective study from Turkey. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2020, 49, 681–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel Center for Disease Control (ICDC)-INHIS-4 Israel National Health Interview Survey INHIS-4 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/reports/inhis-4-2019/he/files_publications_units_ICDC_INHIS-4-2019.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Israel Diabetes Registry Report. Available online: https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/generalpage/diabetes-2012-2022/he/files_publications_units_ICDC_diabetes-2012-2022.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Pankakoski, A.; Kluger, N.; Sintonen, H.; Panelius, J. Clinical manifestations and comorbidities of pemphigus: A retrospective case-control study in southern Finland. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2022, 32, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, S.; Astman, N.; Berco, E.; Solomon, M.; Trau, H.; Barzilai, A. Epidemiological data of 290 pemphigus vulgaris patients: A 29-year retrospective study. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2016, 26, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassona, Y.; Cirillo, N.; Taimeh, D.; Al Khawaldeh, H.; Sawair, F. Diagnostic patterns and delays in autoimmune blistering diseases of the mouth: A cross-sectional study. Oral Dis. 2018, 24, 802–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzzi, M.; della Vella, F.; Squicciarini, N.; Lilli, D.; Campus, G.; Piazzolla, G.; Lucchese, A.; van der Waal, I. Diagnostic delay in autoimmune oral diseases. Oral Dis. 2023, 29, 2614–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, N.; Yeo, J.; Lee, Y.; Aw, D. Oral Pemphigus Vulgaris: A Case Report and Literature Update. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2004, 33 (Suppl. 4), 63S–68S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljubojević, S.; Lipozenčić, J.; Brenner, S.; Budimčić, D. Pemphigus vulgaris: A review of treatment over a 19-year period. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2002, 16, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; De, D.; Handa, S.; Ratho, R.; Bhandari, S.; Pal, A.; Kamboj, P.; Sarkar, S. Identification of factors associated with treatment refractoriness of oral lesions in pemphigus vulgaris. Br. J. Dermatol. 2017, 177, 1583–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishii, N.; Maeyama, Y.; Karashima, T.; Nakama, T.; Kusuhara, M.; Yasumoto, S.; Hashimoto, T. A clinical study of patients with pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceous: An 11-year retrospective study (1996–2006). Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2008, 33, 641–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamim, T.; Varghese, V.I.; Shameena, P.M.; Sudha, S. Pemphigus vulgaris in oral cavity: Clinical analysis of 71 cases. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2008, 13, E622–E626. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abdalla-Aslan, R.; Benoliel, R.; Sharav, Y.; Czerninski, R. Characterization of pain originating from oral mucosal lesions. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2015, 121, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardazzi, F.; Rucci, P.; Rosa, S.; Loi, C.; Iommi, M.; Di Altobrando, A. Comorbid diseases associated with pemphigus: A case-control study. J. Der Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2021, 19, 1613–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimouni, D.; Anhalt, G.J. Pemphigus. Dermatol. Ther. 2002, 15, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, B.S.; Hertl, M.; Werth, V.P.; Eming, R.; Murrell, D.F. Severity score indexes for blistering diseases. Clin. Dermatol. 2012, 30, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| N | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 39 (61.9) |

| Male | 24 (38.1) | |

| Origin | Jewish | 53 (84.2) |

| Arab | 10 (15.8) | |

| Age | 44 and younger | 22 (34.9) |

| 45–64 | 32 (50.7) | |

| 65 and up | 9 (14.4) | |

| Medical history * | Cardiovascular/hypertension | 15 (23.8) |

| Diabetes | 10 (15.8) | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 10 (15.8) | |

| Hypothyroidism | 4 (17.4) | |

| Psychological disorders | 4 (17.4) | |

| Other dermatologic disorders | 3 (4.7) | |

| S/P malignancy | 3 (4.7) | |

| GERD, Fibromyalgia | 2, 1 (8.7, 1.6) |

| At Onset *^ | After Treatment ^ | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral lesion site * N = 63 | N (% **); | N (% **); | |

| Buccal mucosa | 48 (80) | 28 (55) | |

| Soft Palate | 45 (75) | 26 (50) | |

| Tongue | 34 (57) | 14 (27) | |

| Labial mucosa | 32 (53) | 12 (24) | |

| Gingiva | 29 (48) | 10 (20) | |

| Lips | 22 (37) | 7 (14) | |

| Floor of mouth | 21 (35) | 7 (14) | |

| Hard palate | 14 (23) | 2 (4) | |

| Mean total number of | lesion sites (SD) | 4.71 ± 1.86 | 2.57 ± 1.34 |

| Symptoms discomfort/ | pain (mean VAS) (SD) | 7.64 ± 2.24 | 3.21 ± 3.2 |

| Oral Lesion Sites at Onset, Pain, Post-Treatment Sites and Hospitalization Period | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral site involvement at onset | Pain at onset— Mean VAS (SD) | Pain after treatment— Mean VAS (SD) | Sites after treatment— Mean (SD) | Hospitalization days— Mean (SD) |

| Lip—positive | 8.10 (2.1) (labial) * | 3.38 (3.25) | 2.74 (1.6) | 40.68 (21.44) |

| Lip—negative | 5.29 (3.9) (labial) * | 1.13 (2.0) | 1.53 (1.2) | 25.84 (19.44) |

| p value | 0.021 | 0.029 | 0.005 | 0.008 |

| Tongue—positive | 8.26 (2.21) | - | - | - |

| Tongue—negative | 5.56 (3.32) | - | - | |

| p value | 0.016 | - | ||

| FOM—positive | - | - | 42.81 (25.70) | |

| FOM—negative | - | - | 25.08 (11.56) | |

| p value | 0.001 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Czerninski, R.; Abu Elhawa, M.; Cleiman, M.; Keshet, N.; Haviv, Y.; Armoni-Weiss, G. Oral Involvement and Pain Among Pemphigus Vulgaris Patients as a Clinical Indicator for Management—An Epidemiological and Clinical Study. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10145. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151810145

Czerninski R, Abu Elhawa M, Cleiman M, Keshet N, Haviv Y, Armoni-Weiss G. Oral Involvement and Pain Among Pemphigus Vulgaris Patients as a Clinical Indicator for Management—An Epidemiological and Clinical Study. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(18):10145. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151810145

Chicago/Turabian StyleCzerninski, Rakefet, Manal Abu Elhawa, Michael Cleiman, Naama Keshet, Yaron Haviv, and Gil Armoni-Weiss. 2025. "Oral Involvement and Pain Among Pemphigus Vulgaris Patients as a Clinical Indicator for Management—An Epidemiological and Clinical Study" Applied Sciences 15, no. 18: 10145. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151810145

APA StyleCzerninski, R., Abu Elhawa, M., Cleiman, M., Keshet, N., Haviv, Y., & Armoni-Weiss, G. (2025). Oral Involvement and Pain Among Pemphigus Vulgaris Patients as a Clinical Indicator for Management—An Epidemiological and Clinical Study. Applied Sciences, 15(18), 10145. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151810145