Abstract

Selection to a national team is a prestigious milestone, and the World Padel Championships showcase elite talent on a global stage. This study explored the relationship between national team quality—measured via individual FIP (Federacioón Internacional de Paádel, International Padel Federation) rankings and points—and final team placements at the 2024 World Padel Championships in Qatar. Data from 16 men’s and 16 women’s teams included final standings, average and median FIP rankings, and total and average FIP points. Pearson correlation and ANOVA were applied to average FIP rankings; due to non-normality, Spearman correlation and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used for total FIP points. Results indicated that top-ranked teams, such as Argentina, Spain, and Italy, had more players above the competition-wide ranking threshold, whereas teams like Uruguay and the USA had none. Balanced ranking distributions were observed in male teams such as Belgium and The Netherlands and in female teams such as Portugal and Argentina. A moderate positive correlation emerged between average team rankings and final placements for men, and a strong correlation for women. Total FIP points showed a very strong negative correlation with final rankings for both genders. In conclusion, individual player quality, as indicated by rankings and points, strongly correlates with team performance in the 2024 World Padel Championships.

1. Introduction

Padel is a racquet sport that originated in Mexico in 1969 and experienced its first major expansion in Argentina in the early 1990s, followed by a second surge in Spain in the late 1990s [1]. More recently, particularly after the COVID-19 pandemic, the sport has experienced remarkable global growth, now boasting over 30 million players across 140 countries [2]. Played in doubles on a 20 × 10 m rectangular court divided by a net, padel features unique side enclosures of metal mesh, alternating with side and back enclosures of glass or walls, allowing for continuous play off rebounds [3].

As the sport has grown, so too has research on padel [4,5,6,7], with a focus primarily on technical–tactical performance analyses [8,9,10]. However, studies examining the determinants of team performance in international competitions remain scarce, leaving a gap in understanding how the quality of individual players influences team success on a global stage.

Major international events are of paramount interest to stakeholders and fans alike [11,12,13], and national governments invest heavily in the pursuit of medals and global sporting success [14,15]. Typically, medal count at these events serves as measures of country performance [16,17,18,19], though counts or proportions of athletes in top-finishing positions in world-ranking lists are also used as indicators of national success [20,21]. Among such international competitions, the World Championships by nations represent the pinnacle of sporting contests for athletes in many sports, including padel, where only the most elite players are selected to represent their nations.

Beyond sporting prestige, national team selections carry significant economic implications [22]. Federations often invest substantial financial resources to recruit and support players based on rankings and perceived individual quality, aiming to improve their chances in international competitions [23]. These decisions impact not only sporting success but also institutional funding, sponsorship agreements, and athlete contracts. Similar dynamics can be observed in professional club competitions, where player rankings influence recruitment [24]. Therefore, understanding whether individual player metrics—such as rankings and points—predict collective performance has not only scientific value but also direct practical relevance for stakeholders in high-level padel.

Every two years, the World Padel Championships bring together top players from around the globe to compete at the highest level, transforming individual talent into a collective display of national pride. For most athletes, selection to a national team is a prestigious milestone, often regarded as career-defining [25]. With only eight players selected per national team, in accordance with the official competition regulations, the competition is fierce, and each athlete’s performance contributes to the overall team outcome. Unlike the professional tour—where players typically choose their own partners—national team competitions often involve pairings made strategically by national coaches. Additionally, players compete not only for personal success, but for their team and country, facing unique psychological and social pressures [26]. In each tie, three doubles pairs from one team (i.e., country) face three pairs from the opposing team, with the nation that wins at least two matches claiming victory in the tie.

Yet, it remains unclear how much individual rankings and points—widely regarded as indicators of player quality—translate to team success in such a setting. While individual rankings offer a quantifiable view of player ability, pair and team performance is a multifaceted phenomenon. Theoretical models in sport psychology and performance science emphasize that collective outcomes emerge from interactions, coordination, and complementary roles within teams [27,28].

According to the Shared Mental Models framework, successful teams develop a common understanding of tactical strategies, player roles, and situational responses, which enhances decision-making under pressure [29]. Likewise, Collective Efficacy Theory highlights the importance of a team’s shared belief in its ability to succeed, particularly in high-stakes environments [30,31]. These perspectives are further supported by systems-based approaches such as ecological dynamics, which view team performance as an emergent property shaped by real-time interaction constraints, rather than isolated attributes [32]. Together, these theoretical foundations suggest that although national padel teams composed of highly ranked players may have a performance advantage, that advantage is modulated by internal cohesion, role distribution, and interaction fluency—factors not captured by rankings alone.

The aim of this study was to examine the relationship between the quality of national padel teams—quantified by the individual rankings and points of their players—and their final team placements in the 2024 World Padel Championships held in Qatar in both men’s and women’s competitions. Specifically, this study seeks to determine whether teams with higher-ranked players achieve better outcomes in this international competition, thereby offering insights into how individual player metrics might serve as predictors of collective team success.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Data Collection

The sample consisted of all 16 men’s and 16 women’s national teams that participated in the final stage of the 2024 World Padel Championships. Each national team included eight players, in accordance with competition regulations. All ranking and points data were retrieved from the FIP database as of 28 October 2024. This date was selected to ensure that rankings and points reflected the most up-to-date player performances leading into the tournament. Final team standings were obtained from the official competition results published by the FIP.

2.2. Study Variables

The study analysed key performance indicators, including the final team position, the average and median FIP rankings of all selected players, and the total and average FIP points accumulated by each team’s players. Previous research in sports have employed similar proxies (e.g., ATP/WTA rankings and ratings in tennis, FIFA rankings in football, medal counts or placements in Olympic studies) as performance indicators [33,34,35]. The final team position represented the ranking achieved by the national team at the conclusion of the tournament, while the average and median rankings provided a measure of the overall quality of selected players. Total team FIP points reflected the combined competitive success of the players leading up to the tournament, whereas average FIP points captured the individual strength of each team’s members. To determine whether team performance levels differed significantly in terms of player ranking and FIP points, teams were divided into three performance categories: top-ranked teams (1st–4th place), mid-ranked teams (5th–12th place), and bottom-ranked teams (13th–16th place).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics (mean, SD (Standard Deviation), median, and IQR (Interquartile Range)) were computed for all ranking and point variables. Preliminary normality tests (Shapiro–Wilk) indicated that FIP Ranking Average was normally distributed for both men’s (W = 0.939, p = 0.233) and women’s teams (W = 0.969, p = 0.485). In contrast, FIP Points Total significantly deviated from normality for both genders (men: W = 0.567, p < 0.001; women: W = 0.528, p < 0.001). Therefore, parametric tests were applied to ranking variables, and non-parametric tests to FIP points. Based on these findings, Pearson correlation and one-way ANOVA were applied to FIP Ranking Average, whereas Spearman correlation and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used for FIP Points Total. Correlation analyses were conducted separately for men’s and women’s teams to examine the relationship between individual player metrics and final team standings. ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis tests assessed differences across these categories, with post hoc Tukey’s HSD and Dunn’s tests identifying specific group differences.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 and Table 2 summarize the rankings and FIP points for men’s and women’s teams. Spain dominated both categories, with the highest number of FIP points and lowest average ranking.

Table 1.

Team performance summary in men’s padel.

Table 2.

Team performance summary in women’s padel.

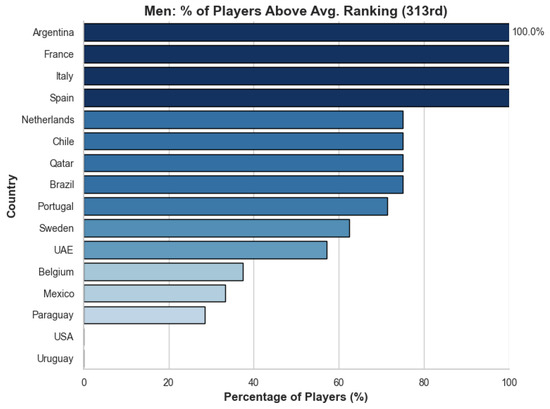

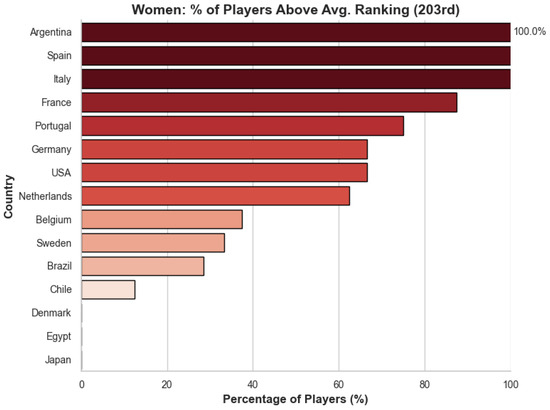

Figure 1 and Figure 2 illustrate the proportion of players per country who were ranked above the competition-wide average ranking for men (313rd) and women (203rd) in the 2024 World Padel Championships (excluding players with no FIP points). These figures provide an overall perspective on how many highly ranked players each national team fielded, offering insight into the depth of competitive talent within each squad.

Figure 1.

Number of Male Players Ranked Above the Competition-Wide Average (313rd) per Country.

Figure 2.

Number of Female Players Ranked Above the Competition-Wide Average (203rd) per Country.

For men’s teams (Figure 1), Argentina, Spain, Italy, and France had the highest number of players ranked better than 313rd with the full team in the top 313, indicating strong roster depth and overall team strength. Brazil, Chile, Qatar and The Netherlands also featured a good number of above-average players, suggesting that they had competitively balanced squads. In contrast, Uruguay and the USA had no players above this threshold, implying a greater reliance on lower-ranked competitors.

For women’s teams (Figure 2), Argentina, Italy, and Spain led in the number of players ranked above 203rd, reinforcing their status as top-performing nations in the competition. France and Portugal also demonstrated strong depth, while Uruguay, Japan, Egypt and Denmark had no players ranked in the top 203.

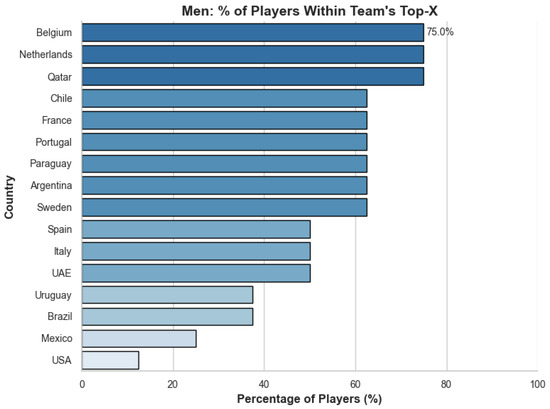

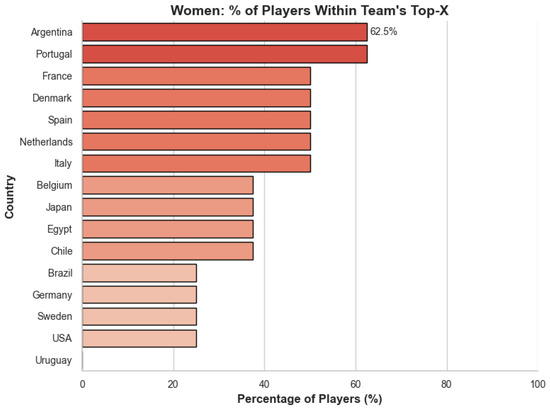

Figure 3 and Figure 4 present the proportion of players within each country’s Top-X ranking threshold, where Top-X represents the average ranking of all selected players per team, excluding those with no FIP points. This measure differs from the previous figures by focusing on internal team balance, showing the percentage of players in each squad who were within their own national ranking range rather than comparing them directly to the entire competition.

Figure 3.

Distribution of Top-X Ranked Male Players Across Countries in the 2024 Padel World Championship.

Figure 4.

Distribution of Top-X Ranked Female Players Across Countries in the 2024 Padel World Championship.

For men’s teams (Figure 3), countries such as Belgium, The Netherlands, and Qatar had a high proportion of players within their Top-X ranking, suggesting that their teams were internally well-balanced in terms of ranking distribution. However, these teams had fewer players ranked above the competition-wide average, indicating that, while balanced, they may have lacked truly elite players capable of outperforming the top nations.

For women’s teams (Figure 4), Portugal and Argentina had the highest proportion of players within their respective Top-X threshold, indicating a structured and balanced selection approach. However, the USA, Sweden, Germany and Brazil had a lower proportion of players within their Top-X, which could imply a wider range of ranking levels within their squads or a selection strategy focusing on a few highly ranked individuals.

3.2. Correlation Analysis

Table 3 summarizes correlation analyses between individual player metrics and final team standings. For FIP Ranking Average, a moderate positive correlation was observed for men (r = 0.63, p = 0.010) while a strong positive correlation was found for women (r = 0.81, p < 0.001). These results indicate that teams with better-ranked players tend to achieve better final standings, with this effect being stronger in women’s teams. For FIP Points Total, Spearman correlation demonstrated a very strong negative correlation for both men (ρ = −0.90, p < 0.001) and women (ρ = −0.85, p < 0.001). These findings suggest that teams accumulating more FIP points are significantly more likely to perform better in the final standings.

Table 3.

Statistical Analysis of FIP Rankings, FIP Points, and Team Performance in the 2024 World Padel Championships.

3.3. Group Comparisons: ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis Tests

To investigate whether team ranking significantly differed across performance groups, teams were categorized into top-ranked (1st–4th place), mid-ranked (5th–12th place), and bottom-ranked (13th–16th place) (Table 3). For FIP Ranking Average, a one-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of ranking category on player rankings for both men (F = 5.61, p = 0.018) and women (F = 5.66, p = 0.017). Post hoc comparisons using Tukey’s HSD for FIP ranking average test indicated that, for men, top-ranked teams had significantly better-ranked players than bottom-ranked teams (p = 0.01), but no significant differences were found when comparing top ranked and mid-ranked teams (p = 0.30) nor when comparing mid-ranked and bottom-ranked teams (p = 0.09). For women, top-ranked teams had significantly better-ranked players compared with both bottom-ranked teams (p = 0.02) and mid-ranked teams (p = 0.03), while no differences were found between mid- and bottom-ranked teams (p = 0.78). For FIP points total, a Kruskal–Wallis test found significant differences in FIP Points across performance groups for both men (H = 9.28, p = 0.010) and women (H = 8.75, p = 0.013). Post hoc Dunn tests confirmed that, for men, top-ranked teams accumulated significantly higher FIP points than bottom-ranked teams (p = 0.01), with no significant differences found for top-ranked compared to bottom-ranked teams (p = 0.28) nor for mid-ranked teams compared to bottom-ranked teams (p = 0.20). For women’s teams, there was no significant difference in FIP points between mid and bottom teams (p = 0.99), However, top-ranked teams accumulated significantly more FIP points compared to both bottom-ranked (p = 0.02) and mid-ranked (p = 0.03) teams.

4. Discussion

This study explored the association between the overall quality of national padel teams—measured through the individual rankings and points of their players—and their final standings in the 2024 World Padel Championships in Qatar. Specifically, it aimed to assess whether teams composed of higher-ranked players tend to achieve superior results in this international competition, providing valuable insights into the extent to which individual performance metrics can predict collective team success. The novelty of this study lies in its examination of how the quality of individual players influences team performance on a global stage, offering a unique perspective on the dynamics of elite-level padel competition.

The results of this study provide evidence that individual player rankings and accumulated FIP points are significant predictors of national team performance in the World Padel Championships. The findings revealed strong positive correlations between average player ranking and final team position, particularly among women’s teams, and a similarly strong negative correlation between total team FIP points and final team position. These results indicate that teams composed of better-ranked players, and those with higher cumulative FIP points, tend to achieve better outcomes in international team competition. One of the key contributions of this study lies in the differentiation between the absolute quality of players relative to the entire competition field and the internal ranking structure within each national team. The number of players ranked above the competition-wide average (Figure 1 and Figure 2) provided a measure of elite talent depth, whereas the proportion of players within each team’s Top-X threshold (Figure 3 and Figure 4) illustrated the internal balance of player rankings. The former approach highlighted the dominance of Spain, Argentina, and Italy, whose teams included a high number of players ranked well above the competition’s average. Conversely, the latter approach showed that teams such as Belgium and Qatar, despite having internally balanced teams, lacked a sufficient number of high-ranked players to compete with the top nations. In team sports, such as football and basketball, team success has been linked to the presence of top-tier athletes and strong developmental structures [36,37]. These findings support the view that individual excellence translates into collective success, particularly when selection processes favour high-performing athletes. Memmert et al. [38] suggest that in team sports, being able to make smart tactical decisions and adjust to different situations during matches is often what separates successful teams from less successful ones. This may partly explain why two national teams with players who have similar FIP rankings might still finish at different positions. Future studies could explore whether tactical adaptability during match play contributes to such differences in team performance. Interestingly, the statistical comparisons between performance groups showed that while top-ranked teams significantly differed from bottom-ranked teams in terms of FIP points and rankings, the difference between mid-ranked and bottom-ranked teams was less pronounced, particularly among women’s teams. One plausible explanation for this pattern lies in the relatively young status of padel as an international sport [1,39]. While a few nations—particularly Spain and Argentina—have developed deep talent pools and robust competitive structures, many others are still in the early stages of athlete development. This disparity is especially evident in the women’s competition, where the sport remains underdeveloped in several countries, limiting the availability of high-ranking athletes and leading to more homogeneous levels of performance among mid- and lower-tier teams.

While the current findings confirm that individual ranking and FIP points are significant predictors of national team success, they must be interpreted in the context of the unique structural demands of national team competition. Unlike the professional circuit, where players select partners with whom they share tactical affinities, national team pairings are often imposed by coaching staff and may lack prior shared experience. This distinction introduces variability not captured by individual metrics. Theoretical frameworks such as Shared Mental Models and Collective Efficacy [27,29] are particularly relevant in this context. Teams with well-established coordination and mutual understanding may outperform higher-ranked but less cohesive pairs, especially under pressure. Performance in team settings is often an emergent property of interaction quality, not simply a sum of individual abilities [40]. Additionally, evidence from broader team sport literature [41] shows that prior shared success significantly enhances team performance, indicating that relational continuity may be as critical as individual skill. In line with these perspectives, our findings support the idea that while individual excellence is a prerequisite, it is the ability to co-adapt and operate as a functional unit—especially under the strategic and emotional load of representing a nation—that ultimately distinguishes the most successful teams.

By differentiating between competition-wide ranking comparisons and intra-team ranking balance, the study provides valuable insights into how player selection strategies influence national team outcomes. Also, from an applied perspective, these findings may help guide team selection and recruitment strategies in federations and private clubs, where decisions are often based on individual rankings. Studies across European football show that team sporting rankings are significantly associated with financial returns, implying that clubs’ investments in high-ranked players often yield measurable economic outcomes [42,43,44]. Given that many clubs allocate considerable budgets to sign high-ranked players for team competitions, confirming a statistical association between individual rankings and collective outcomes offers valuable evidence to support or refine such investment decisions. In this regard, our results contribute not only to the academic understanding of team performance but also to its economic implications in professional padel.

Limitations and Future Studies

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the study focuses solely on ranking and FIP points as indicators of player quality, without considering other factors such as match statistics, tactical adaptability, or psychological resilience, which may also contribute to team success [36] and regarding the results of only one competition (2024 World Championships). Future research should incorporate performance metrics beyond rankings and points, such as win–loss ratios, shot accuracy, and movement efficiency, to provide a more holistic understanding of what drives team performance. Future studies should also check if in padel, prior shared success between team members significantly improves the odds of the team winning beyond the talents of individuals, as it happens in other sports [41]. Additionally, this study does not account for the role of coaching strategies, team cohesion, or adaptability to match conditions, which can all be critical factors in high-level team competitions. In particular, tactical adaptability—i.e., the ability to adjust strategies dynamically during matches—was not measured, although it may help explain differences in performance among teams with similarly ranked players.

Future studies could employ qualitative analyses or match video analysis to explore how in-game decision-making and strategic adaptations influence team success beyond individual player metrics [45]. Finally, while the study examined correlations and group differences, further research using predictive modelling techniques, such as machine learning or regression analysis, could enhance the predictive power of individual player metrics on team performance. This could help national federations optimize their selection strategies for future international competitions. In addition, while this study highlights potential economic implications related to player recruitment and team composition at the national level as seen in previous studies in football [42,43,44], these aspects were not directly measured. Future research could explore the financial impact of selection strategies—such as investment in high-ranked players or team-building policies—on national federation budgets, sponsorships, and long-term performance outcomes.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the strong relationship between individual player quality, as measured by FIP rankings and points, and team performance in the 2024 World Padel Championships. The results confirm that teams with better-ranked players and higher cumulative FIP points tend to achieve superior outcomes. However, the findings also suggest that while depth of talent is important, having a concentrated number of elite players is more predictive of success. Additionally, as padel continues to grow globally, disparities in development—particularly in the women’s game—should be monitored, as they likely contribute to the performance gaps observed between top teams and the rest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.J. and R.C.-R.; methodology, A.J. and Á.B.-S.; software, A.J.; validation, Á.B.-S., R.C.-R. and J.R.-L.; formal analysis, A.J.; investigation, R.C.-R. and J.R.-L.; resources, R.C.-R.; data curation, R.C.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.J. and R.C.-R.; writing—review and editing, J.R.-L.; visualization, A.J. and Á.B.-S.; supervision, R.C.-R.; project administration, R.C.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare financial support was received for the research of this article. This study has been financed by the Universidad Europea de Madrid, through an internal competitive project with code CIPI/22.303.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as it did not involve any intervention with human participants or collection of personal data. The analysis was conducted using publicly available data; therefore, ethical approval was not required according to institutional and national guidelines.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived as this study did not involve any intervention with human participants or collection of personal data. The analysis was conducted using publicly available data; therefore, ethical approval was not required according to institutional and national guidelines.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J. Historia del pádel. Mater. Para Hist. Deporte 2013, 57–60. Available online: https://polired.upm.es/index.php/materiales_historia_deporte/article/view/4140 (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- International Padel Federation. World Padel Report; International Padel Federation: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- International Padel Federation. Rules of Padel. Available online: https://www.padelfip.com/documents/ (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- García-Giménez, A.; Pradas de la Fuente, F.; Castellar Otín, C.; Carrasco Páez, L. Performance Outcome Measures in Padel: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guijarro-Herencia, J.; Mainer-Pardos, E.; Gadea-Uribarri, H.; Roso-Moliner, A.; Lozano, D. Conditional Performance Factors in Padel Players: A Mini Review. Front. Sports Act. Living 2023, 5, 1284063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Miguel, I.; Escudero-Tena, A.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Courel-Ibáñez, J.; Muñoz, D. Physiological, Physical and Anthropometric Parameters in Padel: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2024, 20, 17479541241287439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellado-Arbelo, O.; Baiget, E. Activity Profile and Physiological Demand of Padel Match Play: A Systematic Review. Kinesiology 2022, 54, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde-Ripoll, R.; Martín-Miguel, I.; Muñoz, D.; Escudero-Tena, A. Performance Dynamics in Professional Padel: Winners, Forced Errors, and Unforced Errors among Men and Women Players. Int. J. Perf. Anal. Sport. 2024, 25, 190–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Miguel, I.; Escudero-Tena, A.; Muñoz, D.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J. Performance Analysis in Padel: A Systematic Review. J. Hum. Kinet. 2023, 89, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungureanu, A.N.; Lupo, C.; Contardo, M.; Brustio, P.R. Decoding the Decade: Analyzing the Evolution of Technical and Tactical Performance in Elite Padel Tennis (2011–2021). Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2024, 19, 1306–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntosh, E.; Parent, M. Athlete Satisfaction with a Major Multi-Sport Event: The Importance of Social and Cultural Aspects. Int. J. Event. Festiv. Manag. 2017, 8, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M. What Makes an Event a Mega-Event? Definitions and Sizes. In Leveraging Mega-Event Legacies; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1-315-43984-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sterken, E. Growth Impact of Major Sporting Events. In The Impact and Evaluation of Major Sporting Events; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-1-315-87819-5. [Google Scholar]

- Houlihan, B.; Green, M. Comparative Elite Sport Development: Systems, Structures and Policy; Elsevier Publishing House: Burlington, VT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vaeyens, R.; Güllich, A.; Warr, C.R.; Philippaerts, R. Talent Identification and Promotion Programmes of Olympic Athletes. J. Sports Sci. 2009, 27, 1367–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevill, A.M.; Balmer, N.J.; Winter, E.M. Why Great Britain’s Success in Beijing Could Have Been Anticipated and Why It Should Continue beyond 2012. Br. J. Sports Med. 2009, 43, 1108–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Nevill, A.M.; Balmer, N.J.; Winter, E.M. Congratulations to Team GB, but Why Should We Be so Surprised? Olympic Medal Count Can Be Predicted Using Logit Regression Models That Include “Home Advantage”. Br. J. Sports Med. 2012, 46, 958–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiler, S. Who Won the Olympics? Sportscience 2010, 14, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- UK Sport. Annual Report and Accounts 2011/2012; UK Sport: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Colwell, J. Quantity or Quality: Non-Linear Relationshops between Extent of Involvement and International Sporting Success. In Studies in the Sociology of Sport; Christian University Press: Abilene, TX, USA, 1982; pp. 101–118. [Google Scholar]

- De Bosscher, V.; Du Bois, C.; Heyndels, B. Internationalization, Competitiveness and Performance in Athletics (1984–2006). Sport. Soc. 2012, 15, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguí-Urbaneja, J.; Cabello-Manrique, D.; Guevara-Pérez, J.C.; Puga-González, E. Understanding the Predictors of Economic Politics on Elite Sport: A Case Study from Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 12401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goranova, D.; Byers, T. Funding, Performance and Participation in British Olympic Sports. Choregia 2015, 11, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankin, J.A.; Rivas, J.; Jewell, J.J. The Effectiveness of College Football Recruiting Ratings in Predicting Team Success: A Longitudinal Study. Res. Bus. Econ. J. 2021, 14, 4–22. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, A. Deciding Who Is the Best. Validity Issues in Selections and Judgements in Sport. Ph.D. Thesis, Umea University, Umea, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dugdale, J.R.; Eklund, R.C.; Gordon, S. Expected and Unexpected Stressors in Major International Competition: Appraisal, Coping, and Performance. Sport Psychol. 2002, 16, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, E.; Gershgoren, L.; Basevitch, I.; Schinke, R.; Tenenbaum, G. Peer Leadership and Shared Mental Models in a College Volleyball Team: A Season Long Case Study. J. Clin. Sport Psychol. 2014, 8, 184–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, D.; Davids, K. Team Synergies in Sport: Theory and Measures. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, J.E.; Heffner, T.S.; Goodwin, G.F.; Salas, E.; Cannon-Bowers, J.A. The Influence of Shared Mental Models on Team Process and Performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gajardo, M.A.; García-Calvo, T.; González-Ponce, I.; Díaz-García, J.; Leo, F.M. Cohesion and Collective Efficacy as Antecedents and Team Performance as an Outcome of Team Resilience in Team Sports. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2023, 18, 2239–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W H Freeman/Times Books/Henry Holt & Co: New York, NY, USA, 1997; p. ix, 604. ISBN 978-0-7167-2626-5. [Google Scholar]

- Travassos, B.; Davids, K.; Araújo, D.; Esteves, T.P. Performance Analysis in Team Sports: Advances from an Ecological Dynamics Approach. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2013, 13, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A.B.; Busse, M.R. Who Wins the Olympic Games: Economic Resources and Medal Totals. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2004, 86, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knottenbelt, W.J.; Spanias, D.; Madurska, A.M. A Common-Opponent Stochastic Model for Predicting the Outcome of Professional Tennis Matches. Comput. Math. Appl. 2012, 64, 3820–3827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalchik, S.A. Searching for the GOAT of Tennis Win Prediction. J. Quant. Anal. Sports 2016, 12, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strudwick, A.J.; Williams, A. Science and Soccer: Developing Elite Performers, 3rd ed.; Williams, A.M., Ford, P., Drust, B., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-0-203-13186-2. [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio, J.; Lago, C.; Drinkwater, E.J. Explanations for the United States of America’s Dominance in Basketball at the Beijing Olympic Games (2008). J. Sports Sci. 2010, 28, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memmert, D.; Lemmink, K.A.P.M.; Sampaio, J. Current Approaches to Tactical Performance Analyses in Soccer Using Position Data. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Padel Federation History. Padel FIP 2025. Available online: https://www.padelfip.com/history/ (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Thonhauser, G. Being a Team Player: Approaching Team Coordination in Sports in Dialog with Ecological and Praxeo-logical Approaches. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1026859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Huang, Y.; Neidhardt, J.; Uzzi, B.; Contractor, N. Prior Shared Success Predicts Victory in Team Competitions. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2019, 3, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Simone, L.; Zanardi, D. On the Relationship between Sport and Financial Performances: An Empirical Investigation. Manag. Financ. 2020, 47, 812–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galariotis, E.; Germain, C.; Zopounidis, C. A Combined Methodology for the Concurrent Evaluation of the Business, Financial and Sports Performance of Football Clubs: The Case of France. Ann. Oper. Res. 2018, 266, 589–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, F.; McHale, I.; Thomas, D. Maintaining Market Position: Team Performance, Revenue and Wage Expenditure in the English Premier League. B Econ. Res. 2011, 63, 464–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lames, M.; McGarry, T. On the Search for Reliable Performance Indicators in Game Sports. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2007, 7, 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).