Regional Perspectives on Service Learning and Implementation Barriers: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Review Protocol Design

2.1.1. Determining the Review’s Purpose

2.1.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.1.3. Information Sources

2.1.4. Search Strategy

2.2. Literature Search and Study Selection

2.2.1. Identification

2.2.2. Screening

2.2.3. Eligibility

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Qualitative Analysis

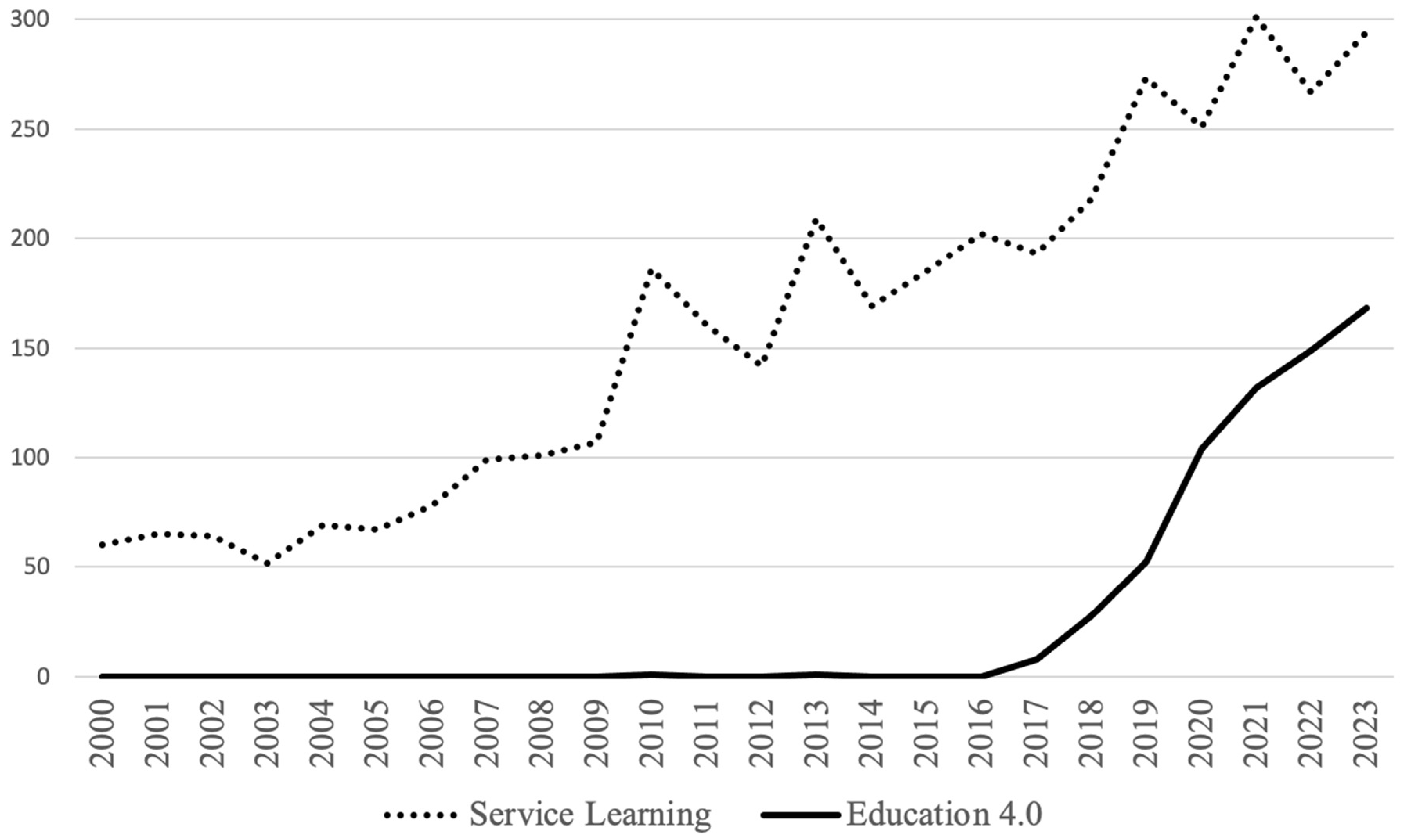

2.4.2. Quantitative Analysis

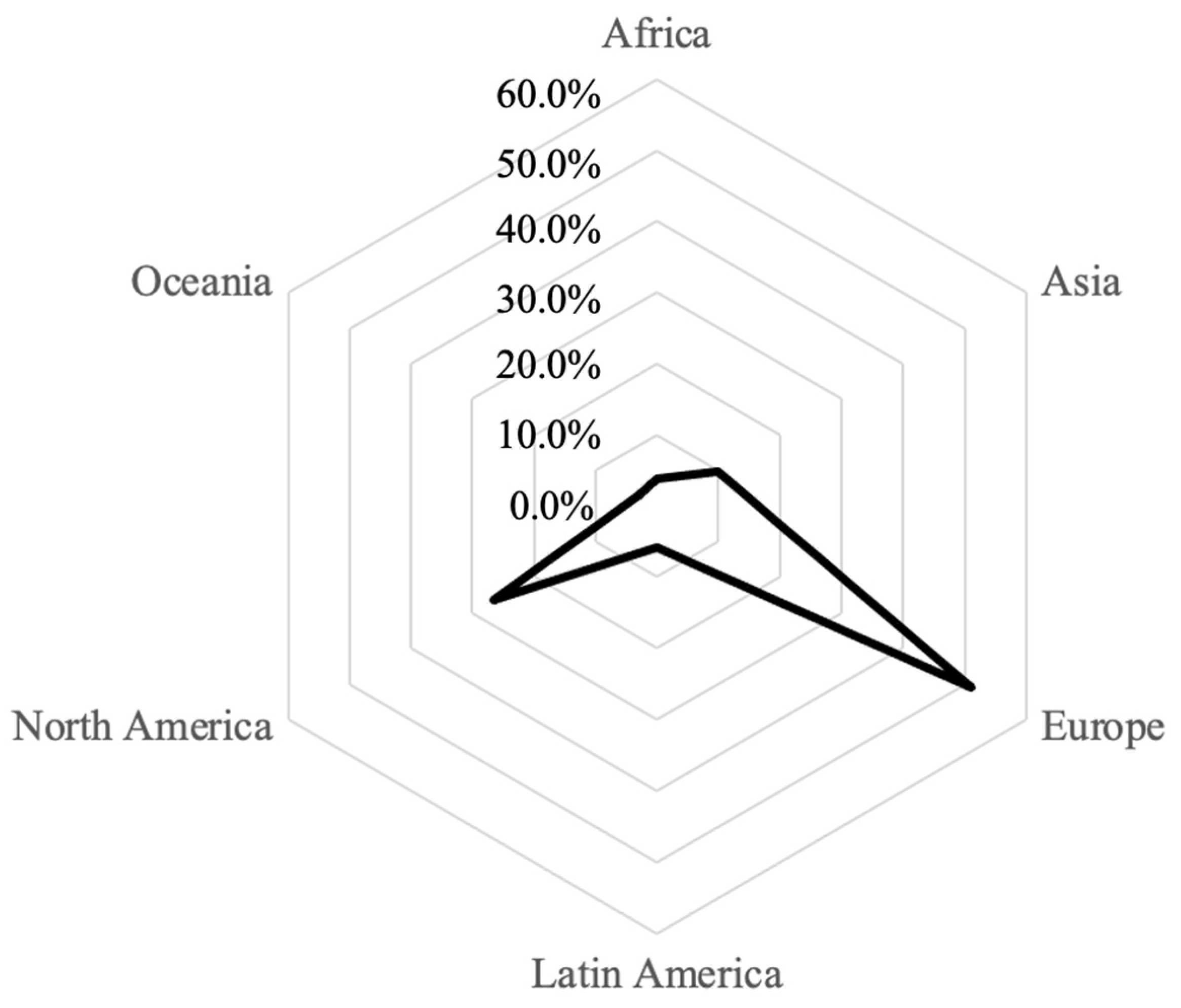

3. Results

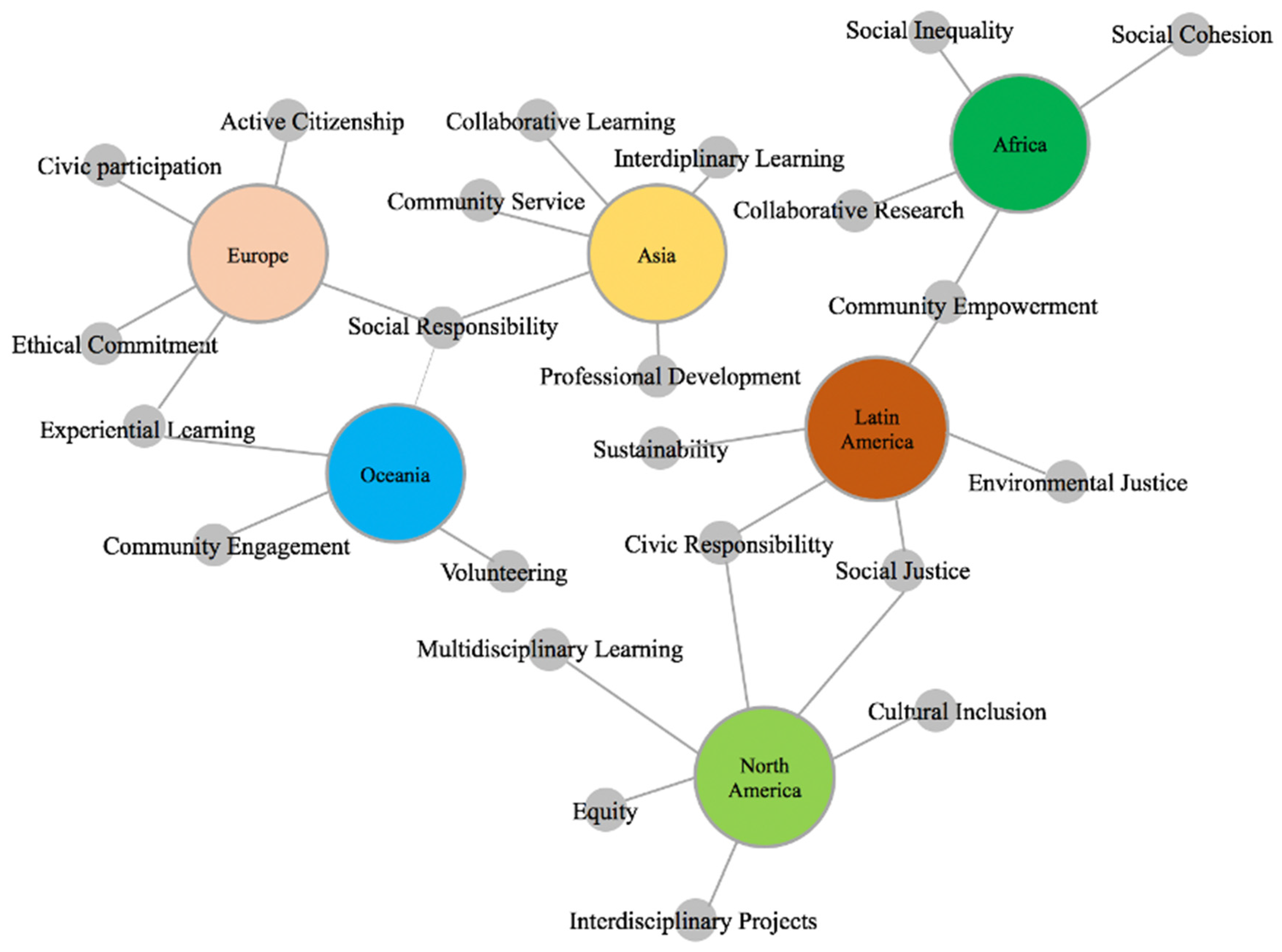

3.1. Service-Learning Conceptions: A Mosaic of Regional Perspectives

3.1.1. Latin America: Service Learning as a Vehicle for Transformation and Social Justice

3.1.2. North America: Inclusion, Multidisciplinary Learning, and Civic Responsibility in Multicultural Contexts

3.1.3. Europe: Service Learning as a Tool for Active Citizenship and Ethical Commitment

3.1.4. Asia: SL as a Strategy for Professional and Social Development and Community Cohesion

3.1.5. Oceania: Volunteering, Experiential Learning, and Community Engagement

3.1.6. Africa: Contextual Misunderstandings, Poor Communication, and Distrust

3.2. Barriers and Challenges in the Implementation of Service Learning

3.2.1. Latin America: Lack of Resources and Institutional Support

3.2.2. North America: Cultural Adaptation Challenges and Resource Limitations

3.2.3. Europe: Resistance to Change and Funding Shortages

3.2.4. Asia: Cultural Challenges and Coordination Issues

3.2.5. Oceania: Research and Institutional Support Limitations

3.2.6. Africa: Need for Community Empowerment and Social Cohesion

4. Discussion

4.1. Core Contribution: Conceptions and Barriers to SL from a Comparative Perspective

4.2. Projecting AI Integration: Opportunities and Constraints

4.3. Ethical Considerations and the Human-Centered Nature of SL

4.4. Methodological Contributions and Study Limitations

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNESCO. Reimagining Our Futures Together: A New Social Contract for Education; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, P.; Yue, X. Talent Leadership Strategies Enhance Teacher’s Professional Competencies in 21st Century Education for Sustainable Development. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 373, 012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodlad, S. (Ed.) Education and Social Action: Community Service and the Curriculum in Higher Education, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-0-429-43855-4. [Google Scholar]

- Smuts, H.; Jordaan, M.; Smuts, C. Towards a Knowledge Operationalisation Model for Service-learning in Community Projects in Higher Education. In Knowledge Management in Organizations; Uden, L., Ting, I.-H., Wang, K., Eds.; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 1438, pp. 41–53. ISBN 978-3-030-81634-6. [Google Scholar]

- Waghid, Y. Knowledge Production and Higher Education Transformation in South Africa: Towards Reflexivity in University Teaching, Research and Community Service. High. Educ. 2002, 43, 457–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelou, I.; Ng, J. A Look Back: Assessment of the Learning Outcomes of the Community-Based Research Experiences of the Senior High School Students of a Higher Education Institution in Batangas. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2022, 21, 342–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tijsma, G.; Hilverda, F.; Scheffelaar, A.; Alders, S.; Schoonmade, L.; Blignaut, N.; Zweekhorst, M. Becoming Productive 21st Century Citizens: A Systematic Review Uncovering Design Principles for Integrating Community Service-learning into Higher Education Courses. Educ. Res. 2020, 62, 390–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokhmani, T.; Sujanto, B.; Luddin, M.R. The Implementation of Academic Responsibility in Higher Education: A Case Study. Integr. Educ. 2019, 23, 336–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Heredia, N.; Corral-Robles, S.; González-Gijón, G.; Sánchez-Martín, M. Exploring Inequality Through Service-learning in Higher Education: A Bibliometric Review Study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 826341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gutiérrez, J.; Corrales Gaitero, C. Las Políticas Supranacionales de Educación Superior Ante La «tercera Misión» de La Universidad: El Caso Del Aprendizaje-Servicio. Span. J. Comp. Educ. 2020, 256–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udagama, P.; Wijayanama, C.; Vithanapathirana, M. An Innovation in Career Guidance in Higher Education: Effectiveness and Sustainability of Institutionalization of Service-Learning in the University of Colombo. In Proceedings of the 2019 from Innovation to Impact (FITI), Colombo, Sri Lanka, 22 November 2019; IEEE: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Truong, V.; Phu, H.B.; Tu, L.T.T. Integrating Community Service-Learning into University Curriculum: Perspectives from EFL Teachers and Students. Lang. Relat. Res. 2020, 11, 201–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, N.; Ibrahim, D.H.A.; Abdullah, J.; Saee, S.; Ramli, F.; Mat, A.R.; Khiri, M.J.A. A Methodology for Implementation of Service-learning in Higher Education Institution: A Case Study from Faculty of Computer Science and Information Technology, UNIMAS. J. Telecommun. Electron. Comput. Eng. 2017, 9, 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Tijsma, G.; Urias, E.; Zweekhorst, M. Embedding Engaged Education through Community Service-learning in HEI: A Review. Educ. Res. 2023, 65, 143–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainuri, A.; Huda, M. Empowering Cooperative Teamwork for Community Service Sustainability: Insights from Service-learning. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotelino-Losada, A.; Arbués-Radigales, E.; García-Docampo, L.; González-Geraldo, J.L. Service-Learning in Europe. Dimensions and Understanding From Academic Publication. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 604825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.G.; Bringle, R.G.; Hatcher, J.A. International Service-Learning: Conceptual Frameworks and Research, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023; ISBN 978-1-003-44537-1. [Google Scholar]

- Tapia, M.N.; Giorgetti, D.; Furco, A.; Maas Weigert, K.; Vinciguerra, A.; González, A.; Luna González, E.; Ma Hok-Ka, C.; Bouwman, B. Hacia Una Historia Mundial del Aprendizaje-Servicio; CLAYSS: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pusppanathan, J.; Zulkapri, I.; Nawi, N.D.; Phang, F.A.; Zulkiflli, N.A.; Khang, A.W.Y.; Alsayaydeh, J.A.J.; Sek, T.K.; Harun, F.K.C. Service-learning Implementation: Empowering Engineering Students via Drone Tech for EDU-4IR Program. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings, Johor Bahru, Malaysia, 29–30 September 2020; p. 030014. [Google Scholar]

- Phang, F.A.; Pusppanathan, J.; Nawi, N.D.; Zulkifli, N.A.; Zulkapri, I.; Che Harun, F.K.; Wong, A.Y.K.; Alsayaydeh, J.A.; Sek, T.K. Integrating Drone Technology in Service-learning for Engineering Students. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2021, 16, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chituc, C.-M. A Framework for Education 4.0 in Digital Education Ecosystems. In Smart and Sustainable Collaborative Networks 4.0; Camarinha-Matos, L.M., Boucher, X., Afsarmanesh, H., Eds.; IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 629, pp. 702–709. ISBN 978-3-030-85968-8. [Google Scholar]

- Caijun, W.; Xi, J.; Zhenzhou, Z. Analysis of Systematic Reform of Future Teaching in the Age of Artificial Intelligence. In Proceedings of the 2021 2nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Education (ICAIE), Dali, China, 18–20 June 2021; IEEE: Dali, China, 2021; pp. 704–707. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, T.; Xu, X.; Zhu, N.; Zhang, J.; Ma, Z.; Xie, H. A Service-Learning Project Based on a Community-Oriented Intelligent Health Promotion System for Postgraduate Nursing Students: Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Med. Educ. 2023, 9, e52279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharbat, F.F.; Alshawabkeh, A.; Woolsey, M.L. Identifying Gaps in Using Artificial Intelligence to Support Students with Intellectual Disabilities from Education and Health Perspectives. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 73, 101–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaparro-Martínez, E.I.; Álvarez-Muñoz, P.; D Armas-Regnault, M. Gestión de la información: Uso de las bases de datos scopus y web of science con fines académicos. Univ. Cienc. Tecnol. 2016, 20, 166–175. [Google Scholar]

- Lesser, L.M. Critical Values and Transforming Data: Teaching Statistics with Social Justice. J. Stat. Educ. 2007, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa-Cervantes, A.; Solís Galán, M.G.; Mayor Paredes, D. Participación Del Estudiantado En Las Prácticas de Aprendizaje-Servicio, Percepciones de Docentes Universitarios Españoles y Mexicanos. Rev. Investig. Educ. 2024, 42, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condeza, R.; Montenegro Armijo, C.; Gálvez Johnson, M. Una Experiencia de Formación Universitaria Para Comunicar Sobre Desigualdad y Pobreza. Cuadernos. Info 2015, 37, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, M.; Tilly, C. Field Education and Community-Based Planning in a Worst-Case Scenario. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2022, 42, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otten, R.; Faughnan, M.; Flattley, M.; Fleurinor, S. Integrating Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion into Social Innovation Education: A Case Study of Critical Service-Learning. Soc. Enterp. J. 2022, 18, 182–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustin, F.; Freshman, B. The Effects of Service-Learning on College Students’ Attitudes Toward Older Adults. Gerontol. Geriatr. Educ. 2016, 37, 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bringle, R.G.; Clayton, P.H. Integrating Service-learning and Digital Technologies: Examining the Challenge and the Promise. Rev. Iberoam. Educ. Distancia 2020, 23, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, J. What Happens When the University Meets the Community? Service-learning, Boundary Work and Boundary Workers. Teach. High. Educ. 2011, 16, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passino, K.M. Educating the Humanitarian Engineer. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2009, 15, 577–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Izquierdo, R.M. Service-learning and Academic Commitment in Higher Education. Rev. Psicodidáctica (Engl. Ed.) 2020, 25, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compare, C.; Albanesi, C. Stand Together by Staying Apart: Extreme Online Service-Learning during the Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Romero, D.; Lalueza, J.L. Procesos de Aprendizaje En Aprendizaje-Servicio Universitario: Una Revisión Teórica. Educ. XX1 2019, 22, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais, S.C.; Dias, T.S.; Benício, D. Connecting Higher Education to the Labour Market: The Experience of Service-learning in a Portuguese University. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-S.; Liu, P.-C.; Lin, Y.K.; Lin, C.-D.; Chen, D.-Y.; Lin, B.Y.-J. Medical Students’ Preclinical Service-Learning Experience and Its Effects on Empathy in Clinical Training. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Belando Montoro, M.R. Investigación Sobre Aprendizaje-Servicio En La Literatura Académica China: Una Revisión Sistemática. Rev. Investig. Educ. 2024, 22, 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, H.-M.; Lee, C.-W.; Cho, T.-L. The Incorporation of Service-Learning into a Management Course: A Case Study of a Charity Thrift Store. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sin, D.; Chew, T.; Chia, T.K.; Ser, J.S.; Sayampanathan, A.; Koh, G. Evaluation of Constructing Care Collaboration—Nurturing Empathy and Peer-to-Peer Learning in Medical Students Who Participate in Voluntary Structured Service-learning Programmes for Migrant Workers. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birzer, C.H.; Hamilton, J. Humanitarian Engineering Education Fieldwork and the Risk of Doing More Harm than Good. Australas. J. Eng. Educ. 2019, 24, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, N.; Andersen, L. Creating Shared Value Through Service-Learning in Management Education. J. Manag. Educ. 2017, 41, 750–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matambanadzo, A.; Manyard, M.; Matambanadzo, T. Implementing a Replicable Model for K-12 Health Literacy to Promote Positive Youth Development. J. Consum. Health Internet 2018, 22, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbugua, T. Fostering Culturally Relevant/Responsive Pedagogy and Global Awareness through the Integration of International Service-Learning in Courses. J. Pedagog. 2010, 1, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhele, M.; Pinfold, N. Exploring the Nexus between Transdisciplinarity, Internationalisation and Community Service-Learning at a University of Technology in Cape Town. Transform. High. Educ. 2021, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cate, R.; Russ-Eft, D. Expanding Circles of Solidarity: A Comparative Analysis of Latin American Community Social Justice Project Narratives. Power Educ. 2020, 12, 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras Vásquez, P.; Azuaje Pirela, M.; Díaz Fuenzalida, J.P.; Bedecarratz Scholz, F.; Bozzo Hauri, S.; Finol González, D. Enseñanzas y Aprendizaje de La Inteligencia Artificial y Derecho En Chile. Rev. Pedagog. Univ. Didact. Derecho 2021, 8, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildenbrand, S.M.; Schultz, S.M. Implementing Service-learning in Pre-Service Teacher Coursework. J. Exp. Educ. 2015, 38, 262–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farber, K.; Bishop, P. Service-learning in the Middle Grades: Learning by Doing and Caring. RMLE Online 2018, 41, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janich, N.; Mendoza, N.; Mackey, C.; Hernandez, N.; Henderson, A.; Reily, T.; Lundwall, R. Supporting Independent Living Through Interdisciplinary Service-learning: The Community Collaborative Model. Adv. Soc. Work 2021, 21, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Gutiérrez, J.; Ruiz Corbella, M. La Idea de Universidad Desde Un Enfoque Humanista: La Contribución Del Aprendizaje-Servicio Como Filosofía de La Educación Superior. Teoría Educ. 2022, 34, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortari, L.; Ubbiali, M. Service-learning: A Philosophy and Practice to Reframe Higher Education. Athens J. Educ. 2021, 8, 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramburuzabala, P.; Culcasi, I.; Cerrillo, R. Service-Learning and Digital Empowerment: The Potential for the Digital Education Transition in Higher Education. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hok-ka, C.; Mui-Fong MAK, F.; Cheng LIU, A. Service-Learning and the Aims of Chinese Higher Education. In Service-Learning as a New Paradigm in Higher Education of China; Michigan State University Press: East Lansing, MI, USA, 2018; pp. 17–44. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Du, M.; Zhou, X. E-Service-Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Experiences of Mainland Chinese Students Enrolled at a University in Hong Kong. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longman, J.; Barraclough, F.; Swain, L. The Benefits and Challenges of a Rural Community-Based Work-Ready Placement Program for Allied Health Students; James Cook University: Townsville, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Petray, T.; Halbert, K. Teaching Engagement: Reflections on Sociological Praxis. J. Sociol. 2013, 49, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMarais, S.C.; Mumford, S.W.; Ryan, T.F. The Transformative Potential of Service-Learning in an African Religious Context. Int. J. Res. Serv. Learn. Community Engagem. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eeden, E.; Eloff, I.; Dippenaar, H. On Responses of Higher Education and Training With(in) Society Through Research, Teaching, and Community Engagement. Educ. Res. Soc. Change 2021, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Articles presenting research findings. | Other document types, such as reviews, letters to the editor, editorials, reflective texts, books, and book chapters. |

| Articles that explicitly or implicitly mention the review topic in the title or abstract. | Articles that do not mention the review topic in the title or abstract, or for which relevance cannot be inferred. |

| Approach taken from an educational perspective. | Approach taken from perspectives other than educational. |

| Articles published in English or Spanish. | Articles published in other languages. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lavaux, S.; Salas, J.I.; Chiappe, A.; Ramírez-Montoya, M.S. Regional Perspectives on Service Learning and Implementation Barriers: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9058. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15169058

Lavaux S, Salas JI, Chiappe A, Ramírez-Montoya MS. Regional Perspectives on Service Learning and Implementation Barriers: A Systematic Review. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(16):9058. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15169058

Chicago/Turabian StyleLavaux, Stephanie, José Isaias Salas, Andrés Chiappe, and Maria Soledad Ramírez-Montoya. 2025. "Regional Perspectives on Service Learning and Implementation Barriers: A Systematic Review" Applied Sciences 15, no. 16: 9058. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15169058

APA StyleLavaux, S., Salas, J. I., Chiappe, A., & Ramírez-Montoya, M. S. (2025). Regional Perspectives on Service Learning and Implementation Barriers: A Systematic Review. Applied Sciences, 15(16), 9058. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15169058