1. Introduction

Controlling objects with two inputs and two outputs, where each input affects each output, requires careful controller design [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. An example of such an object is the simultaneous stabilization of the power and frequency of a semiconductor laser by controlling its current and temperature, the temperature being controlled by a Peltier-based micro cooler. Another example is the automatic mixing of several substances, when it is necessary to simultaneously control both the increase in the volume of the mixture and the concentration of each substance. A third example is the well-known problem of filling a swimming pool, with the need to separately control the flow rate and temperature of the water. Similar problems arise in controlling the movement of a vehicle in air or water. There are many examples of such problems in robotics, chemistry, metallurgy, and scientific research.

Let us consider the problem of controlling linear objects. The proposed approach can also be applied to nonlinear objects, but the result obtained should be more carefully checked for the case of test signals of different amplitudes. In general, the problem of controlling nonlinear objects is much more complex. It is practically impossible to consider it in sufficient depth within the framework of one article, except for such types of nonlinearities as a limit or a relatively small deviation of the characteristic from the linear one (no more than 10%). The discussed method is unsuitable for controlling objects with nonlinearity of the “dead zone” type, as well as “dry friction”, “hysteresis”, or other ambiguous nonlinearities. The proposed method is insufficient for controlling nonstationary objects. Adaptive control systems are needed for such objects.

The mathematical model of a linear two-channel object is defined in the form of a matrix transfer function [

11,

12].

There are many papers that consider objects of size n × n, but no articles have been found with reliable information about successful control in such a formulation of the problem, i.e., with multichannel negative feedback and a multichannel sequential controller, even for objects of a size of only 3 × 3. Therefore, the term “multichannel objects” should be recommended to be used more carefully than is currently accepted in the literature. Most often, “two-channel” objects are described even in such articles where “three-channel” objects are mentioned. In this article, we prove the validity of our thesis (established by induction) on the example of an object of size 3 × 3. If necessary, we are ready to go further, to objects of size 4 × 4, but we do not know such problems from practice, so we are in no hurry with these studies.

This approach should not be confused with multiparameter optimization problems or multicriteria optimization problems.

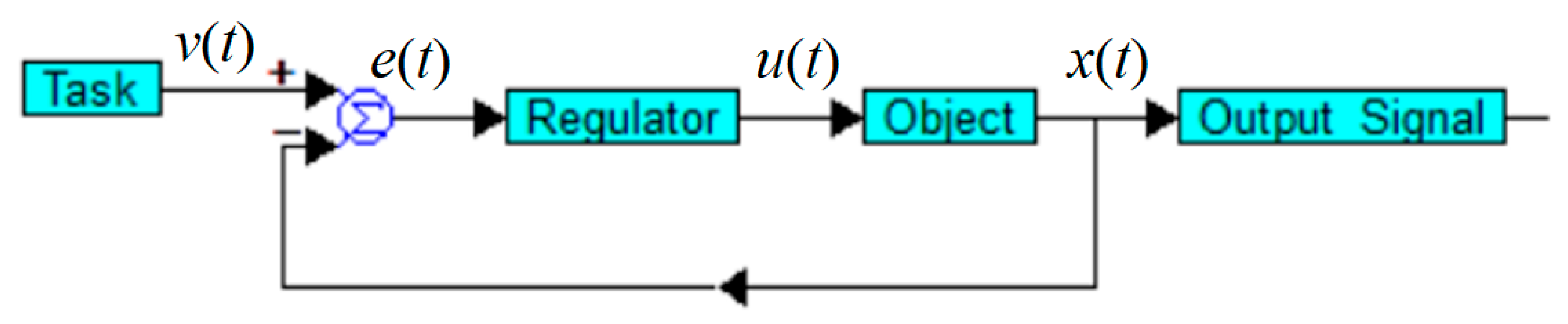

Control in a negative feedback loop is carried out according to the structure shown in

Figure 1.

This structure best satisfies the requirement that the output signal

corresponds to its set value

(“task” or “target” value). It is necessary to ensure the equality

as accurately as possible. This is ensured by a feedback loop that acts in such a way as to ensure the relationship

. Here, the element marked with a circle with a sign

inside is an adder, but if there is a minus sign before the input, this input is subtractive. This and the following illustrations are made in the VisSim 5.0e software, which has some features for displaying various mathematical symbols, numerical values, and other elements. In particular, the minus sign looks like a dash, blue rectangles indicate composite blocks that have a complex structure inside, and their name is set by the user. The arrows indicate the direction of the signals. When using the structure according to

Figure 1, the task of controlling an object is reduced to calculating a mathematical model of the regulator (controller) based on a known mathematical model of the object.

The paper [

13] considers the problem of adaptive control of multichannel objects using neural networks in the class of fractional nonlinear feedback. The paper considers three examples with sizes 2 × 2, 3 × 3, and 2 × 2, respectively.

In the paper [

14] the problem of quantized control of a heavy launch vehicle with failures of the propulsion mechanism and gyroscope is analyzed. For monitoring the unmeasured derivative, a predetermined-time observer is proposed. The parameter setting in this case is simpler than for fixed-time observers.

In [

15] two low-gain controllers for two types of systems are proposed. The same authors in [

16] propose an observer based on a partial differential equation. In these papers, as in many similar ones, the matrix representation of the object equations is not a consequence of the multichannel nature but a way to simplify the description of a high-order object, while the controlled object remains single-channel.

In [

17], an optimal preliminary iterative control problem based on the Padé approximation with equivalent input disturbance is proposed for a class of continuous-time indefinite systems.

In [

18], an adaptive nonlinear current controller with active noise suppression is proposed for a distributed system to solve the large ripple problem. In addition, an adaptive internal model controller is built into the current controller to suppress periodic noise.

In [

19], a time-synchronized controller is proposed. Such a design leads to an increase in control efficiency compared to traditional sliding modes. This efficiency is probably associated with the elimination of the self-oscillating mode when switching between different modes at a certain threshold level in noise conditions. Here, it would obviously be more efficient to introduce hysteresis so that the hysteresis value exceeds the noise from determining this threshold. If the sliding mode switches to a strong oscillation mode due to an unaccounted delay, then synchronization of the controller will not be able to eliminate this problem. For example, such a method was used in the article [

20], where microwave heating is needed to combat ice on the contact wires of railway tracks. For the microwave generator to not operate continuously, but only when necessary, a tracking system is used. This system uses a PID controller in which a constraint is introduced.

The paper [

21] has many external signs of connection with the topic of this article: it contains the term MIMO, uses a functional matrix to describe the connections between elements, and talks about the control of unmanned aerial vehicles. However, the topic of this article is different. It talks about ensuring optimal stable communication between individual aerial vehicles.

In [

22], an adaptive event-driven PI control method is proposed for a class of nonlinear multiple-input multiple-output (MIMO) systems with indefinite input delay. For this purpose, a new variable is developed based on the Padé approximation and the Laplace transform. Then, a nonlinear controller with a PI structure is developed and an event-driven control strategy for dynamic communication resource allocation based on the nonlinear PI controller is established. With the proposed method, nonlinear MIMO systems are able to dynamically handle input delays of varying lengths while maintaining sufficient tracking performance.

In [

23], the issue of adaptive finite-delay memory-driven lane control for autonomous heavy-duty trucks with rollover avoidance under nonlinear corner stiffness is addressed. A lane delay with a defined characteristic is used to achieve the expected convergence properties. In addition, problem-specific technical solutions are applied.

In [

24], an adaptive pseudo-inverse control scheme based on a fuzzy logic system and a Lyapunov barrier function is proposed for a class of hysteretic nonlinear systems where all states are always strictly constrained in each set of constraints. In this paper, the hysteretic nonlinearity in actuators is considered and mitigated by the proposed pseudo-inverse control algorithms, which means that a direct inverse hysteresis model is not needed, but instead a mechanism is used to find the actual control signal from the temporal control signal. Also, the constraint management problem for all states of the hysteresis model is solved when the control signal is coupled into double integral functions using the mentioned methods and the proposed pseudo-hysteresis inverse algorithms.

In [

25], an integrated framework including a distributed controller is proposed to systematically solve combined problems related to the control of the movement of a group of automated vehicles. A two-stage curvilinear coordinate scheme is proposed. In addition, constraints on both longitudinal and transverse acceleration are taken into account. The constrained longitudinal acceleration is included in the design of a nonlinear saturated controller, the convergence of which is proven. Adaptive fusion is implemented using a constrained transverse controller. A condition for limiting the initial states is formulated to ensure safe maintenance of the distance between vehicles.

In [

26], a performance-specific adaptive robust control (PPARC) scheme for uncertain robotic arms is introduced. First, a state transformation is introduced to embed predefined output constraints into the constraints of the trajectory tracking servo. Second, PPARC is designed to perform reference trajectory tracking and ensure that the tracking errors are within the predefined output constraints regardless of the uncertainty and deviation of the initial conditions. Then, Lyapunov stability analysis is carried out to prove the uniform boundedness and uniform finite boundedness of the tracking error. Moreover, the control parameter optimization is transformed into an optimal design problem, and a fuzzy cost function is proposed for the optimal design problem. The existence and uniqueness of the solution of the optimal design problem are theoretically proved. Finally, the effectiveness and superiority of the proposed control scheme are demonstrated based on simulation modeling.

The article [

27] studies the problem of formation-circle flight switching control for several heterogeneous omnidirectional intelligent navigation systems in an intermittent communication network. For each system, a distributed hybrid finite-time observer is proposed to evaluate target state information. The article does not propose fundamentally new control methods from the standpoint of automatic control theory.

In the article [

28] a method of control with provision of stability in finite time is used and developed. The developed modified theory is applied for the example of control of a pendulum, that is, a scalar stable object, since the pendulum is not inverted.

The paper [

29] presents a new predictive control scheme based on a learning economic model for uncertain nonlinear systems subject to input and output constraints and unknown dynamics. The paper develops a Lipschitz regression method that combines clustering and kernel regression to study the unknown dynamics. Sufficient conditions are derived to ensure recursive feasibility and stability of the closed-loop system from input to state.

In the paper [

30], a modified control algorithm with active disturbance suppression based on feedforward compensation is proposed, aimed at the problem of train speed control under external disturbances, which reduces the dependence on the train model. In the mathematical model of the system studied in this paper, there are several output value sensors and several tasks, namely: two output values are estimated, as well as the derivative of one of them. However, this system cannot be considered multichannel, since all control signals are summed into a single scalar control signal received at the control input of the object.

In the paper [

31], a quantized controller is presented for solving the problem of fast finite-time synchronization of multilayer networks, where each layer represents a separate type of interaction in complex systems. Based on the stability theory, a new criterion for fast finite-time stability is derived, which allows setting a smaller upper limit on the settling time compared to the general finite-time stability. By converting continuous error signals into piecewise continuous forms, a quantized control scheme is used to implement fast finite-time synchronization in multilayer networks, which allows saving control resources and reducing communication overload. In this paper, the matrix description also appears due to the high order of the object and not due to the large number of channels.

The paper [

32] considers cooperative localization of multiautonomous underwater vehicles. This paper proposes a filtering algorithm for a slave underwater vehicle with a failed compass, based on the “two masters and one slave” cooperative localization model. The proposed algorithm allows for accurate estimation of the change in the unknown heading angle without expanding the state dimension under non-Gaussian measurement noise.

The articles reviewed solve similar or close problems, but the formulation of the problem in these articles is still significantly different and, in most cases, it is tied to the particular features of the problems being solved. The technical and theoretical solutions developed and proposed in these articles are not applicable to the class of problems considered in our article.

2. Statement of the Problem

In the early stages of the development of the theory of automatic control, the control task was posed and solved from the point of view of finding a control signal that should be fed to the input of the object so that its output values (called output signals) coincide with the “task” prescription. This approach is impractical. The task can change; therefore, the calculation of the control signal loses its relevance. In addition, the object is always affected by factors that cannot be measured and considered in such a statement of the task. Using the structure according to

Figure 1 is a different statement of the task. Instead of calculating the signal controlling the object, a mathematical model of the device is calculated, which only calculates the required control signal depending on the task and the actual output signal of the object. A characteristic property of systems with negative feedback is that, with the correct calculation of the regulator, the control task is successfully solved even in the presence of unknown and uncontrolled influences on the object, which change its output signal in an unpredictable way. In the frequency band, where the transfer function of the controller and the object connected in series with it is much greater than unity, the output signal matches the task quite accurately.

In this case, the difference between the output signal and the task , called the error , is inversely proportional to the product of the controller transfer function and the object transfer function . If , then . Here is all types of disturbing effects on the object, is the approximate value of the transfer function of the object in a given frequency range, is the argument of the Laplace transform, similar to the frequency, but having a small negative real value in addition to the complex component .

The problem with using this method is that each object has a transfer function , limited by some frequency band. With increasing frequency, the transfer function decreases , although in some local frequency ranges it can increase. However, starting from some frequencies, it decreases so sharply that no amplification of the input control signal can achieve a significant response at the object output. For this reason, the transfer function of the entire loop in a conditionally open form inevitably reaches a value close to unity and then decreases even more. In the frequency range where this value is much less than unity, the control loop no longer has a noticeable effect on the object, so its output signal in this frequency range is not controllable. We must put up with this. But in the intermediate frequency band between those where the transfer function of the circuit is much greater than unity, which allows control of the object, and those where the transfer function is much less than unity, which excludes the possibility of controlling the object, there is a frequency region where the transfer function of the circuit is in the range from 0.1 to 10, i.e., from to . In this frequency range, the behavior of the transfer function of the loop affects the stability of the system. If at these frequencies the signal delay exceeds (or which is the same value in other measure units) then the system will be unstable. Therefore, the art of the designer of locked dynamic systems consists in calculating such a controller that would ensure the stability of the locked system, as well as its sufficient accuracy in the frequency region where control is provided.

For multichannel systems, this is not enough. An additional property called “decoupling” or diagonal decoupling is needed. It consists in the fact that any change in the task signal at any input should not only provide a corresponding change in the output signal at the corresponding output but also should not affect the output signals of all other inputs. This requirement can be met only approximately. There was a scientific direction called “invariant control” which studies such control methods so that the control error is always strictly zero, but this area of automatic control theory has lost its relevance. The object is always affected by uncontrolled disturbing factors, which are usually described as an unknown interference, which is applied to the output of the object in the form of an additive unknown signal. Instead of the unrealistic task of completely eliminating the influence of disturbance, the modern section of control theory dealing with high-precision systems considers the problem of limiting the error to a certain value measured as a percentage of the task increment. An error of less than 5% of the task was considered acceptable at the early stage of automatic control theory. In modern high-precision systems, requirements are imposed to suppress the error to values of no more than 0.0001% and, in some cases, to an even smaller value. In problems of controlling multichannel objects, as a rule, the error is reduced to values of the order of 1–5%. In this case, we are talking about a dynamic error, since a static error, i.e., an error that is established after a sufficiently long time, provided that the task signals are step functions, can be reduced strictly to zero. This error does not include errors in measuring the output signal, which can never be reduced strictly to zero.

Thus, the problem of controlling an object, given the above, is reduced to the problem of designing a controller for an object with a known mathematical model, using the structure shown in

Figure 1. Other structures and other formulations of the control problem are also known, which we do not consider in this paper.

The controller for a linear object (1) can be represented as a matrix transfer function [

33,

34,

35,

36]. For example, for an object with two inputs and two outputs, such a transfer function has the following form:

In the simplest case, this matrix is diagonal, that is, only the diagonal elements are nonzero, and the remaining elements are equal to zero:

This means that there are only feedback connections from each output to the corresponding input and no other connections.

In more complex structures, additional loops may appear, for example, a loop that covers an object in addition to the device that subtracts the output signal from the task. There may also be a loop that covers the controller with feedback. The feedback may contain a transfer function that differs from unity. Ultimately, such modifications can be reduced by equivalent transformations to the structure shown in

Figure 1, with the difference that the controller’s transfer function will be different, more complex.

The choice of a controller containing parallel proportional, integrator, and derivative channels (which is therefore called a PID controller) is determined by the fact that for many practical tasks this choice is sufficient and also by the fact that simpler structures in which one or two of the specified paths are missing are a special case of such a controller. These simpler structures can be obtained in the same way as in the design of a PID controller, which does not change the approach to the problem of controlling an object of type (1).

The development of computer technology and software has simplified the task of designing controllers for complex systems to the maximum [

37,

38]. For this reason, it is not even necessary to think about whether the problem can be solved using only a diagonal matrix controller or whether a full-fledged multichannel controller with all nonzero elements of the matrix transfer function is needed [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48]. In many cases, it is enough to simply calculate a full PID controller, which in practice for objects of size 2 × 2 and 3 × 3 turns out to be slightly more difficult than calculating simplified diagonal controllers. This will be demonstrated below.

The most common examples in the literature of multichannel objects are objects with dimensions 2 × 2. In this case, the object model is a matrix transfer function of the same dimensions.

For control, a matrix PID controller of the same size is required [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. A more complex controller can also be considered, for example, containing additional channels for double differentiation, double integration, or some more complex structural solution. For a PID controller, its individual elements are described by the sum of the proportional, integrating, and derivative channels with the corresponding coefficients:

The structure of the control system is shown in

Figure 1.

3. Theory of Solving Problems of Multichannel Object Control

The theory of locked dynamic systems is well-developed: negative feedback ensures accuracy, provided that the entire system is stable. Structural design consists of choosing the structure of the controller. Parametric design consists of determining the parameters of the controller based on the chosen structure.

Structural design is not the subject of this article, since PID controllers are the most common, and the reason for this is their simplicity and efficiency. Simpler controllers, such as PI and PD, are not considered, since this simplification does not greatly simplify the method but limits its capabilities. Complication by introducing additional channels of double integration or (and) double derivation is also not considered, since the approach under consideration can easily be extended to these structures. Structures with a large number of additional loops, such as the Smith predictor, local and pseudo-local connections, etc., are not considered due to their excessive complexity and low efficiency, which has also already been confirmed by modeling and practice.

Parametric design in our case is the main content of the system design task. The methods for calculating the controller parameters can be grouped into the following broad categories: analytical, engineering, tabular, empirical, and numerical.

Analytical methods are based on the direct solution of matrix equations, which leads to the Riccati equation. If the matrix transfer function is not degenerate, it can be inverted. The inversion of this matrix is one of the important elements for the analytical solution of the problem under consideration. Even if the control problem is formulated in a different mathematical formulation, analytical methods cannot cope without inverting the matrix transfer function of the object.

The inverse matrix is a matrix that, when multiplied on the right or left by the original matrix, yields the identity matrix. If the matrix transfer function has at least one delay link, the inverse matrix transfer function yields a transfer function that cannot be implemented as a real device.

Let us look at an example.

Inverting this matrix gives the following result:

It is easy to verify that multiplication from the left or right by this matrix yields a unit matrix. But the resulting matrix

consists of functions that cannot be implemented in any physical device. The fact is that the function

describes in operator form (in the form of Laplace transforms) such a transformation of the input signal, which consists in delaying the input signal by time

. However, at the same time, the transfer function

describes such a transformation, which forms an input signal at the output of the element with a negative delay, that is,

seconds earlier than this signal arrived at the input of the element. Such a “signal prediction link” cannot physically exist, it is something like a hypothetical “time machine”. Thus, if there is a delay in the model of the object, then analytical methods cannot be applied to the calculation of the regulator for such an object, or it is necessary to invent methods for reducing the delay to some other mathematical description, for example, to the Padé approximation. But such an approximation makes all calculations excessively complex and yet unreliable, and the result of the calculation is unreliable. The main objection to this approach is based on the fact that any mathematical model of any real object that does not take into account the delay of this object is insufficiently detailed for its effective use. This thesis is substantiated in

Appendix A.

Tabular methods such as the Cohen–Kuhn, Ziegler–Nichols, Cohen–Coon, and Chien–Hrones–Reswick methods and similar ones [

29] are always unreliable, so they are hopelessly outdated. These methods assume that the mathematical model of the object is described accurately enough by a series connection of a first- or second-order filter and a delay element:

Tabular methods suggest obtaining the graph of the transition process as a response to a single jump, after which this graph is used to determine several basic parameters of this model. Using the table, the parameters of the PID or PI controller for such an object are determined. A modification of this method is another method in which the object is covered with proportional negative feedback, after which the coefficient of this feedback is selected so that undamped oscillations with constant amplitude are established in the system. Then, using the frequency and amplitude of these oscillations, the coefficients of the PID controller are also calculated from the table. All these methods rarely give an acceptable result and never give the best possible result. The problem with them is that they often lead to an unstable system.

Some authors report that, after using one of the tabular methods, they slightly adjusted the coefficients, which yielded satisfactory results. However, in this case, it must be acknowledged that the tabular method could not be used at all. It would be sufficient to set arbitrary coefficients for the controller and then adjust them. This empirical method of adjusting controllers is widely used. It is used much more often than is indicated in the articles, because the fact that the empirical method is used does not justify writing a scientific article. The controller coefficients are simply increased sequentially until the stability of the system is disrupted and then reduced to a value at which stability is restored.

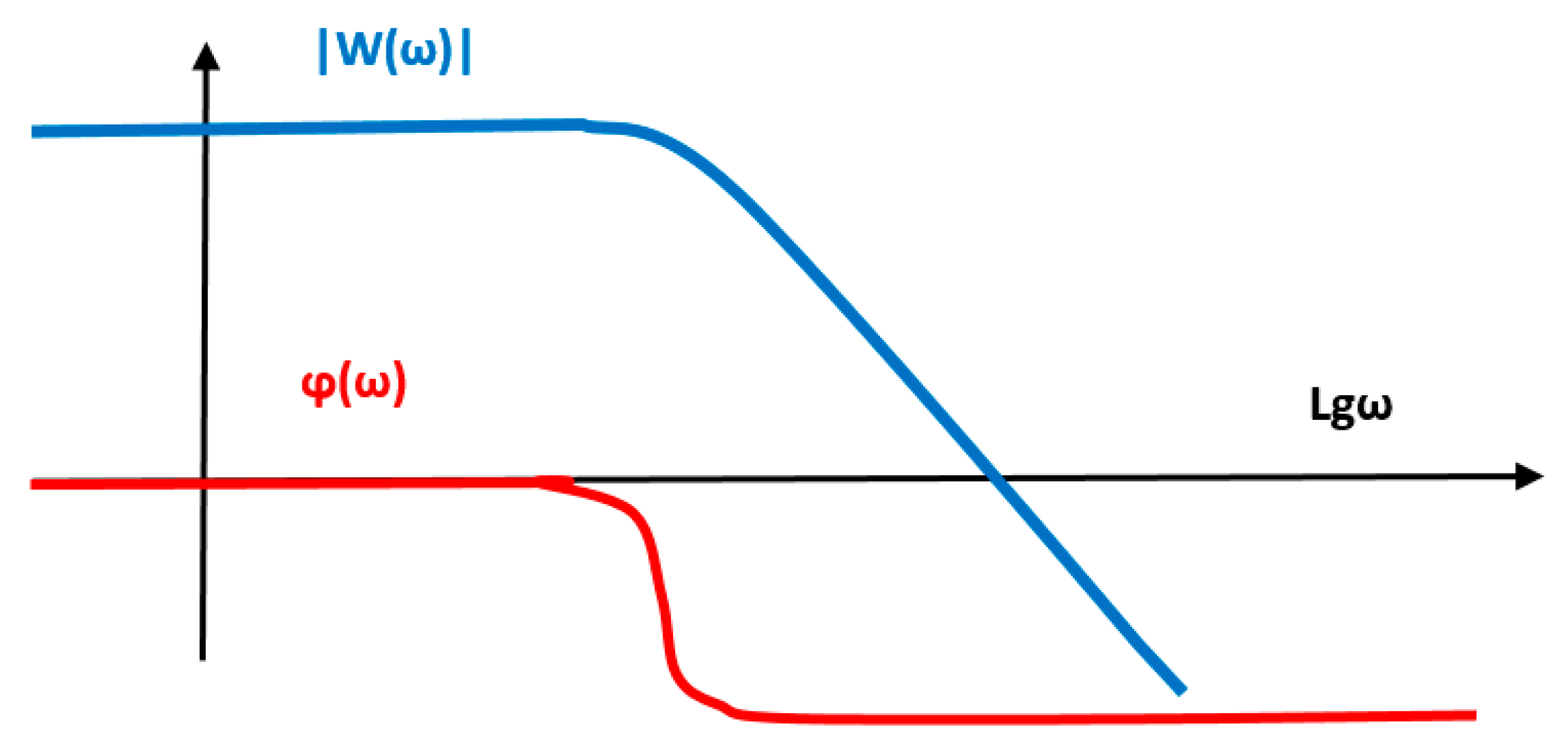

Engineering methods consist in constructing an asymptotic logarithmic amplitude–frequency characteristic, as well as a phase characteristic with the subsequent use of the logarithmic Nyquist–Mikhailov stability criterion. These methods work well for single-channel systems but have not been developed for multichannel systems and it is too late to develop them, since they are morally obsolete. Before the active use of computing technology, the construction of logarithmic graphs was much more efficient and simpler than the construction of graphs on a linear scale. An effective technique has been developed for constructing such graphs and their use for analyzing the stability of the system, as well as for ensuring stability by correcting the logarithmic amplitude–frequency characteristic. A method is also known for calculating a mathematical model of a correcting device based on the obtained logarithmic amplitude–frequency characteristic of this device. Currently, the construction of logarithmic graphs that approximately describe the control object is already a more complex technique than numerical optimization. Thus, for linear objects with delay, the best method is the numerical optimization method if the object has at least the simplest nonlinear component. Then the numerical optimization method is the only reliable method that allows obtaining adequate results with the least labor costs.

The most reasonable approach is to make a preliminary attempt to design a PID controller [

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73], since simplifying it does not significantly simplify the design procedure and complicating it may not be effective enough.

The claim that more complex structures are not efficient is based on the fact that many types of regulatory complexity lead to coarse systems. Systems in which a slight deviation in the values of at least one of all the coefficients of the mathematical model of an object or regulator causes significant and even fatal changes in the nature of the transient process, including a violation of the stability of the entire system, are called coarse. Such methods leading to the indicated undesirable results include the Smith prediction method, the high-order derivative method, the compensator method—an element connected in series with the controller so that in this element the numerator of the transfer function contains in whole or in part the problematic coefficients of the denominator of the transfer function of the controlled object.

The advantage of numerical optimization is the ability to automatically obtain results. All that is needed is a regular computer, standard software, and a mathematical model of the object, as well as knowledge that can be obtained from the relevant literature, taking into account the recommendations of this article. The disadvantage of the numerical optimization method is the inability to solve the problem. Each solution is relevant only for a mathematical model with specific numerical values of all parameters of this model. However, some deviations of the actual values of the model parameters from the values used for the calculation are still permissible. If the solution remains valid with a deviation of these parameters of 1–2%, the solution can be called rough. If the solution remains valid even with a deviation of 5–10% in the parameters, such a solution would be clearly sustainable. However, this is not always possible. If the model parameters can deviate from the calculated values, then an adaptive control system is needed, which is not considered in this article.

Before describing the solution to the problem, we will establish the requirements for the transfer function of the object (1) necessary for there to be a solution to the problem. First, the matrix transfer function of the object (1) should not be singular. Its rank should coincide with its dimensions; in this case, the rank should be equal to 2. In addition, it is highly desirable, although not necessary, that with

the matrix

should also be nonsingular. If this matrix is singular, then control in the static mode will have some features [

73]. They consist in the fact that, even in a static mode, the control signals cannot be static. That is, to ensure that the output signals of the object take the set value in a stationary mode, it is not enough that the control signals entering the input of the object have some necessary static value. These signals will have to change over time, even to ensure a stationary output state. This can be proven theoretically and experimentally [

57].

4. Method for Solving the Problem

The solution method consists of using the following input tools: (a) modeling and optimization software; (b) test signal; (c) modeling conditions (sampling step and modeling time); (d) objective function; (e) optimization method; (f) method for analyzing the results; and (g) method for improving the result if it is not good enough.

Naturally, the question arises: “If the result is optimal, then how can we raise the issue of its further improvement?”

However, the point is that the objective function is not the only option that follows from the management objectives. For a set of management objectives, a wide variety of objective functions can be justified, formed, and used. In addition, the result also depends on the modeling conditions and weighting coefficients in these objective functions, on which the method for further improving the result is based.

The optimization method deserves special comments. If the optimization is completed successfully, then it does not matter which optimization method was used. Any optimization method that gives a result should give the same result within the permissible error. If different optimization methods give different results, this indicates an error in solving the problem. Most likely, this can happen when the objective function has several local extrema. In this case, the designer can distinguish a local extremum from a global one by the value of the objective function at these points. If the minimum of the function is sought, then at the point of the global minimum the objective function takes the smallest value, and at the points of the local minimum its value is greater.

If one of the numerical optimization methods does not lead to the desired result, and another method does, then the system designer can simply use the results obtained by a more effective method, and there is no need to think about the reasons why the other method was unsuccessful. Therefore, if someone managed to purchase the necessary product in one store, he is not interested in the reasons for the absence of this product in other stores. In general, different optimization methods can be theoretically analyzed, and the different effectiveness of different methods can also be theoretically justified, although experimental justification is quite sufficient to move forward.

If none of the numerical optimization methods built into the software leads to the desired result, it is necessary to establish the reasons for this. The instability of the optimization procedure is most often a consequence of an insufficiently effective objective function. The objective functions proposed in this article and their modifications do not create problems, except in cases where the problem cannot be solved by numerical optimization methods due to the lack of a global minimum for the mathematical model of the object used. This issue is also discussed below in

Appendix A.

In VisSim 5.0e, as in other versions of this software, there are two types of optimizations. One of these types is the search for parameters that give the objective function a zero value. We do not use this type of optimization for the problem under discussion. The other type of optimization that we use is the search for parameters that give the minimum of the positive-definite objective function, which in this case is called the “cost function” or simply “cost”. We will use this name further.

The methods we developed were applied in many robotic systems; the most illustrative example of a device in which they were applied is given in

Appendix B.

VisSim has three built-in numerical optimization algorithms. The Powell method, the Polak–Ribière method, and the Fletcher–Reeves method. These methods are well-known enough to be described in this article. The possibility of using them is entirely due to the developers of this software. We have repeatedly established empirically that Powell’s method is the best for this class of problems. In many cases, when one of the other two methods fails, or even both, Powell’s method still succeeds, leading to a set of optimal parameters, i.e., parameters that give a minimum value of the cost function. If any of the other methods works, then it gives exactly the same result as Powell’s method. For this reason, there is no point in using the other two numerical optimization methods. And there is no point in describing the algorithm of Powell’s method. Some references to these methods are provided in

Appendix C.

Powell’s method is based on the calculation of tangents and the assumption that any line passing through an extremum intersects tangents to points with the same value of the objective function at the same angle. The other two methods are based on the calculation of the gradient of the objective function, which is likely to be unstable near the extremum. At these points, the gradient is small, and the influence of noise or random factors can lead to wandering around the extremum. However, if problems do not arise (discussed in

Appendix A), then all three built-in optimization methods can give the same result. We do not propose a new method for numerical optimization. We use a ready-made method that can also be used by any reader using any version of the VisSim 5.0e software.

The proposed method for calculating the controller parameters has been developed and described in detail in our publications [

11,

12,

37,

38]. To solve the problems of controlling multichannel objects, some modification of the cost function is required.

The cost function for this case is the sum of the cost sub-functions for each individual channel [

73]. For each channel, such a cost sub-function is the sum of the integral of the error modulus

multiplied by the time from the start of the transient process

during the process

and penalty additives

. One of the most effective penalty additives is the positive part of the product of the error and its derivative [

11,

12,

37,

38].

The first member of the cost function has the following form:

For the multichannel case, when several test jumps are fed to the system inputs, instead of the multiplier t in Equation (6), a sawtooth function should be used, which increases linearly over the intervals between jumps but is reset to zero with each new jump.

The second term is determined by the following relationship:

Thus, the cost function has the following form:

This cost function is justified by the fact that it implements the necessary principles imposed on it. Terms of the form (6) provide growth (10) in the event that the control error does not decay quickly enough. Thus, the optimization procedure will find such values of the controller coefficients at which the system will not only be stable but the control error will decay quickly enough, so that the integral of the absolute values of all errors will be small. Weighting coefficients will ensure that, the more time that has passed from the onset of the transient process, the greater the contribution of the residual error to Function (10). Terms of the form (7) provide an increase in Function (10) in the event that the error in the system grows. Indeed, in this case the error itself and its derivative will have the same sign. This term will be small if the error grows by a small amount, or if it grows very slowly. Therefore, such a term will form the growth of the cost function as penalties for the growth of the error in magnitude quickly and by a large value. Using this term allows eliminating overshoot, oscillations, and nonmonotonic movements in the resulting system. If the error and its derivative have different signs, their product will be negative and the limiter cutting off the negative part will form zero at its output and, in this case, this term will not affect the cost function (10). The result of optimization will be such a set of regulator coefficients, at which (10) takes a minimum value, that is, the contribution of the first term and the penalties from the second term will be minimal.

The following modifications of the cost function components can also be used:

The rationale for using the square of time in (11) is that the error decreases too slowly. This is because the contribution of the small error to the cost function is too small. The square of the function marking the time since the start of the transient process requires a faster reduction of the error. The more time that has passed since the start of the transient process, the more urgent the need to reduce the error modulus.

The rationale for using the square root in Relation (12) is very natural. It has never been noted or applied before. In fact, if the square root is not used, then the function acquires a quadratic dependence on the error and, therefore, on the test signal, while the main terms of the cost function defined by Relation (6) depend on the amplitude of the input signal not quadratically but only linearly. Therefore, the use of Relation (12) instead of Relation (7) is strongly recommended in all cases. The cubic root Variant (13) is derived by induction: since Variant (12) turned out to be better than Variant (7), it is advisable to try the fourth degree as well. This gives a dependence on the amplitude of the error in the form of a square root. In this case, the contribution of small errors increases compared to the contribution of large errors. There is no theoretical basis for such a solution, but practice sometimes shows the usefulness of such a solution. Note that the nonlinear dependence of the objective function on the amplitude is not fatal, since in the end we still get a linear controller. Then all the results obtained for a linear object remain linear, i.e., when the input signals increase or decrease, the system behaves in the same way, but the output signals increase or decrease accordingly (the superposition principle is valid), as in any linear system.

The examples below show for what purpose it is possible to use a fractional power of the values included in the objective function, in particular the square root of the signal or the fourth root. The rationale for using the square root is that the product of the error and its derivative is a quadratic form that is proportional to the square of the error amplitude. This is not desirable because we are optimizing a linear system. The result should be invariant with respect to the value of the test signal. Using the square root is a natural solution that has not yet been published. Modeling has shown that this improves the performance of the cost function.

The purpose of using the fourth root is based on two arguments. The first argument is that, if introducing a square root improves the result, it is useful to try to apply a higher-order root by induction. The second argument for this approach is that such a nonlinear function increases the contribution of small signals. This allows for the reduction of small deviations of the signal from the desired value, when large deviations are already sufficiently suppressed.

During modeling, it is necessary to feed a test signal to the system model, which represents a task for the system, that is, a vector of input signals describing the desired values of the vector of output variables of the control object.

Since independent control of each output is required, the individual components of this vector must be substantially different functions and there must be no linear relationship between them. Traditionally, when optimizing a scalar linear system, a signal in the form of a single step jump is used [

11,

12,

37,

38]:

Here

is the time discretization step. For this reason, the task vector is proposed as

in the form of stepwise jumps, shifted relative to each other by half the time of the transient process simulation [

74].

In this case, instead of a multiplier proportional to the time from the start of the transient process, a sawtooth signal should be used, linearly increasing from the moment to the moment , after which it resets to zero and again linearly increases from zero at the same rate.

A delay in the occurrence of a step jump by at least the value equal to the doubled time sampling step is a mandatory condition that we have not encountered anywhere in the literature but on which we have grounds to insist. If a jump at the input occurs without such a delay, then the simulation results may not coincide with the practical results, since in this case the system processes not the jump but the initial state of the object, and the results of the signal differentiation in the system in this case will differ. A reliable check of the quality of the system is based on its operation when feeding step jumps and not on the type of processing of the initial state error. In the practice of modeling and optimization, we have had cases when the modeling results in these two noncoincident modes were noticeably different.

VisSim 5.0e software (in any version) contains a mixture of functions in the time domain and functions presented as transfer functions, i.e., in the Laplace transform domain. There is no contradiction in this, since no error will arise. The mathematical notation of equations in such a mixed form would be erroneous, but the mnemonic designation of the blocks used in programming the project is quite understandable and for this reason acceptable. The VisSim 5.0e software, designed for modeling and optimizing automatic control systems with feedback, uses various mathematical models. It contains models of linear elements that are described by transfer functions in the Laplace transform domain, as well as models of nonlinear connections that are described in the time function domain and other elements. The software does not require uniformity of terminology, since it is not necessary to create a full mathematical model of the system in the form of the one-type equations in the standard form for all of the forms as correct mathematical descriptions. The model is created from individual elements, between which, when this model is graphically specified, the appropriate connections are established from the inputs to the outputs; different ways of describing individual elements are not a problem.

5. Results

5.1. Two-Channel Object with a Dominant Main Diagonal

Example 1. Let us consider an object whose transfer function has the following form: We consider such objects for the following reason. A set of simple hypothetical models most accurately reflects all aspects of the possible problems considered in this article. Since not the only favorable type of model was used, but the reverse variant was also studied, then the point of view on the selected part of the problem can be treated as studied. More complex objects of the class considered in this article are characterized by positive poles of some polynomials in the denominators of most specific elements of the transfer function. In this article we do not consider such problems. This is in our plans.

If the polynomial of the transfer function denominators has no positive roots, then any example of the same order (an object of dimension , polynomials in the denominator of dimension 2, polynomials of order zero in the numerator) will not be more difficult than the examples considered in the article. If the polynomial of the transfer functions has positive roots, then slightly different methods are necessary, including, for example, a nonlinear controller or some others.

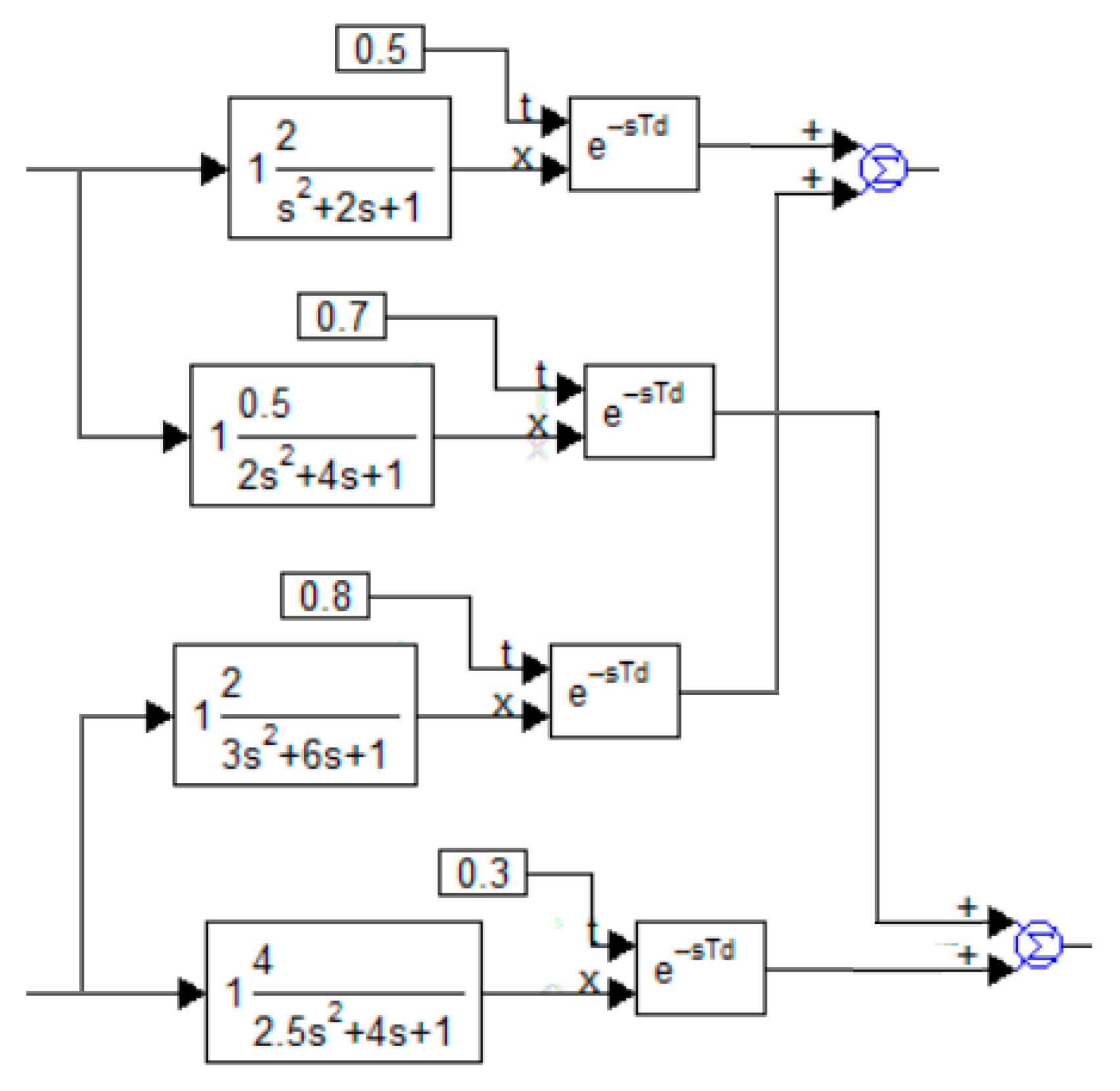

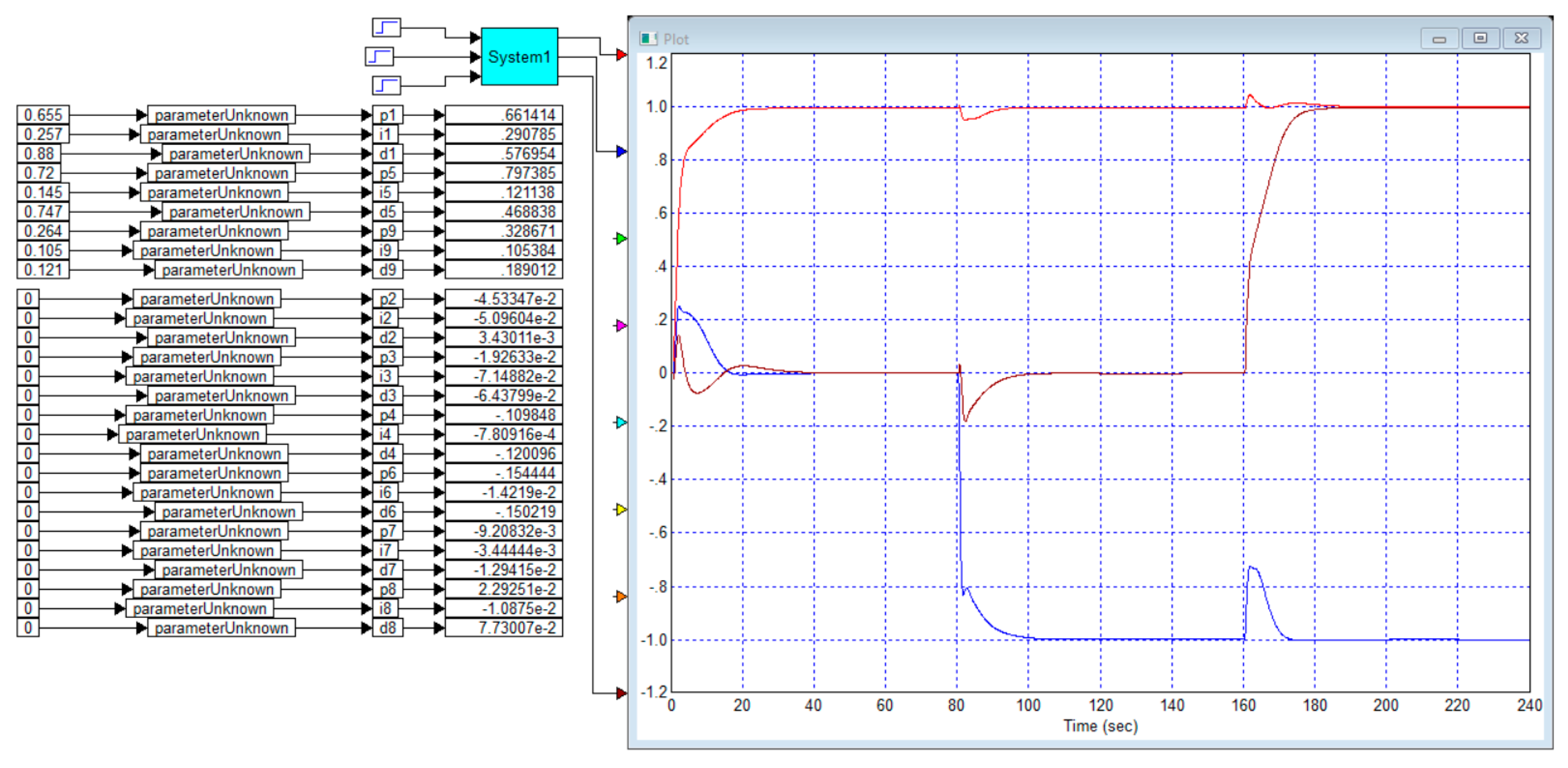

When modeling in the VisSim software, the object is formed from four models, sa in

Figure 2. It should not be surprising that the coefficients of the free terms in the denominators of all transfer functions are equal to unit. This is the canonical form of these functions, because if this were not the case, then the numerator and denominator of these transfer functions would be sufficient to be divided by these coefficients to bring them into canonical form. In this form, the transfer function at

becomes equal to the coefficient in the numerator.

Figure 3 shows the design for optimizing the controller for this case. In this figure, the individual PID controllers and the transfer function elements of the plant are combined into composite blocks called “PID” and “Compound”, respectively.

Figure 3, as well as the following figures, requires some preliminary comments. All these figures are obtained by screenshots from the VisSim 5.0e software, so they are not edited. The rectangles with an asterisk inside denote signal multiplication devices. The rectangles with the inscription “pow” denote devices for raising the power and, unless otherwise indicated in the text, this is the second power. The rectangles with the inscription “derivate” are calculators of derivatives of the input signal. The rectangles with the symbol “1/S” are integrators, a rectangle with the symbol "*" means a signal multiplier. A rectangle with a step or sawtooth waveform drawn inside is a signal generator of this type. A rectangle with the inscription “abs” is a calculator of the absolute value of the input signal, a rectangle with the inscription “cost” is the input of the optimization device, where the calculated value function is fed, which allows programming the formula for its calculation.

The remaining rectangles are bus labels. They give the name to the buses or the quantities used. For each identical mark, it is considered that they are all connected to each other, and only one such block can be supplied with a signal. The program does not allow supplying another signal to another such mark, which is a natural limitation. In addition, the signal value of each mark can be used as a gain factor in another place. The blocks that set the gain factor have the form of a pentagon. In order to set the value of the variable gain factor in this way, it is enough to enter the name of the corresponding bus in the field for recording its value. Also, instead of the bus name, an ordinary number can be written in this field. Decimal numbers in this program are shown in a special format: if the number is less than zero, then the zero before the decimal point is not written, and in negative numbers in this case there is a hyphen before the point, denoting a minus. The exponent is written after the number and separated by the letter “e”. Different colors of the lines correspond to the coloring of the input arrows. In particular, the output signal of the first channel is fed to the oscilloscope through the red arrow, so it is displayed as a red line. The output signal of the second channel is fed through the blue arrow and is displayed by a blue line. In all graphs here and below, the abscissa axis shows time in seconds, and the ordinate axis shows the output signal in conventional units.

The output values of each controlled object are physical quantities. These can be voltage, displacement, heating, rotation angle, etc. Each such value is measured by the corresponding sensor and then compared with the task. In modeling, it is not customary to record the physical units of these values, since control theory does not consider the absolute values of the output values but only their increments relative to the initial equilibrium state, and they are most often normalized. That is, they are divided by some standard value, so that only increments in relative units are displayed on the graphs. For linear systems, this is normal, since scaling the signal does not change the character of the graphs. In this article, we do not consider nonlinear systems.

The monitors in the center of

Figure 3 show the obtained values of the corresponding coefficients of the matrix PID controller.

All the above-mentioned approaches to optimization were applied here.

The software for modeling and optimization is VisSim in any version (VisSim 5.0e was used). This software is very good for such tasks. Unlike MATLAB Simulink (any version), this software simply does not allow modeling of objects that cannot be implemented in practice. This software takes up little disk space, and the files it creates also take up little space. The main advantage is the precise reproduction of the algorithms by which real digital controllers work.

The test signal, as indicated above, is single step jumps, shifted relative to each other by half the simulation time (15).

The simulation conditions are as follows: time discretization step and simulation time . The integration method is the simple Euler method.

The objective function (10) with its constituent functions (6)–(9) is used.

The optimization method is Powell’s method. The optimization method can be selected in the corresponding program dialog box.

The method of analyzing the result is a visual assessment of transient processes, an assessment of the roughness of the solution by rounding the obtained coefficients to 1%, and, if necessary, also changing the parameters of the object model by values or more.

The method to improve the result is to change the weighting coefficients in the cost function. To eliminate overshoot, nonmonotonicity and oscillations, it is necessary to increase the weighting function for the term that depends on the positive part of the product of the error and its derivative. To reduce the static error, it is necessary to reduce this coefficient or increase the modeling time. If this does not help to achieve the desired result, then the modeling time is also increased by modifying the cost function.

In this result, we do not see an overshoot in the transient process of each channel, but we see the response of each channel to a step of the task in the other channel, and this response is about 10% of the corresponding step.

Modeling and optimization showed that further changes in the cost function, including changes in the weighting coefficients of the terms dependent on the product of the error and its derivative, did not significantly improve the transient process. Any specific improvement in one of the parameters of the transient process is achieved only at the expense of worsening the other parameter. Namely, it is possible to completely suppress this reaction in the second channel by increasing such a reaction in the first channel and reducing the reaction speed of both channels. Or it is possible to increase the reaction speed of the second channel and almost completely suppress this reaction, but at the expense of increasing such a reaction in the first channel to 18%. It is also possible to significantly improve transient processes in the first channel, but at the expense of significantly worsening the reaction of which channel: in it, the jump reaction in the task of the first channel increases to 18%.

It should be noted that the relatively successful solution of the problem is achieved due to the fact that the transfer function has advantageous combinations of elements. This property lies in the following three facts. First, the diagonal elements contain transfer functions in which the transmission coefficients are significantly larger than similar coefficients in other elements of the object’s matrix transfer function. Second, these same elements have a smaller delay value. Third, the denominators of these same elements have smaller coefficients in the second- and third-order terms.

Let us show that the indicated dependencies simplify the solution of the problem. To do this, we will reset the elements in the controller matrix that are not on the main diagonal. To do this, it is enough to reset the corresponding coefficients (as shown in

Figure 3) and remove the additional “parameterUnknown” blocks from the design. As can be seen from the figure, the control remains successful and even the deterioration of the control quality is not too great.

However, this is so because in this case the simulation time had to be doubled and accordingly the transients doubled. If in

Figure 3 the processes when applying a jump to the first input last 10 s and when applying a jump to the second input they last 20 s, then in

Figure 4 the processes when applying a jump to the first input last 20 s and when applying a jump to the second channel they last 30 s.

5.2. Two-Channel Object with a Dominant Small Diagonal

Example 2. Let us consider an object whose transfer function has the following form: This example is derived from the object of Example 1, in which the first column is replaced by the second, and the second column is replaced by the first. As a result, the transfer function of the object has become maximally unfavorable according to the criterion discussed above. The elements of the main diagonal are characterized by a large delay, smaller coefficients of the transfer function, and large values of the coefficients in the denominator polynomials.

This example is one of the most unfavorable options for objects from this class.

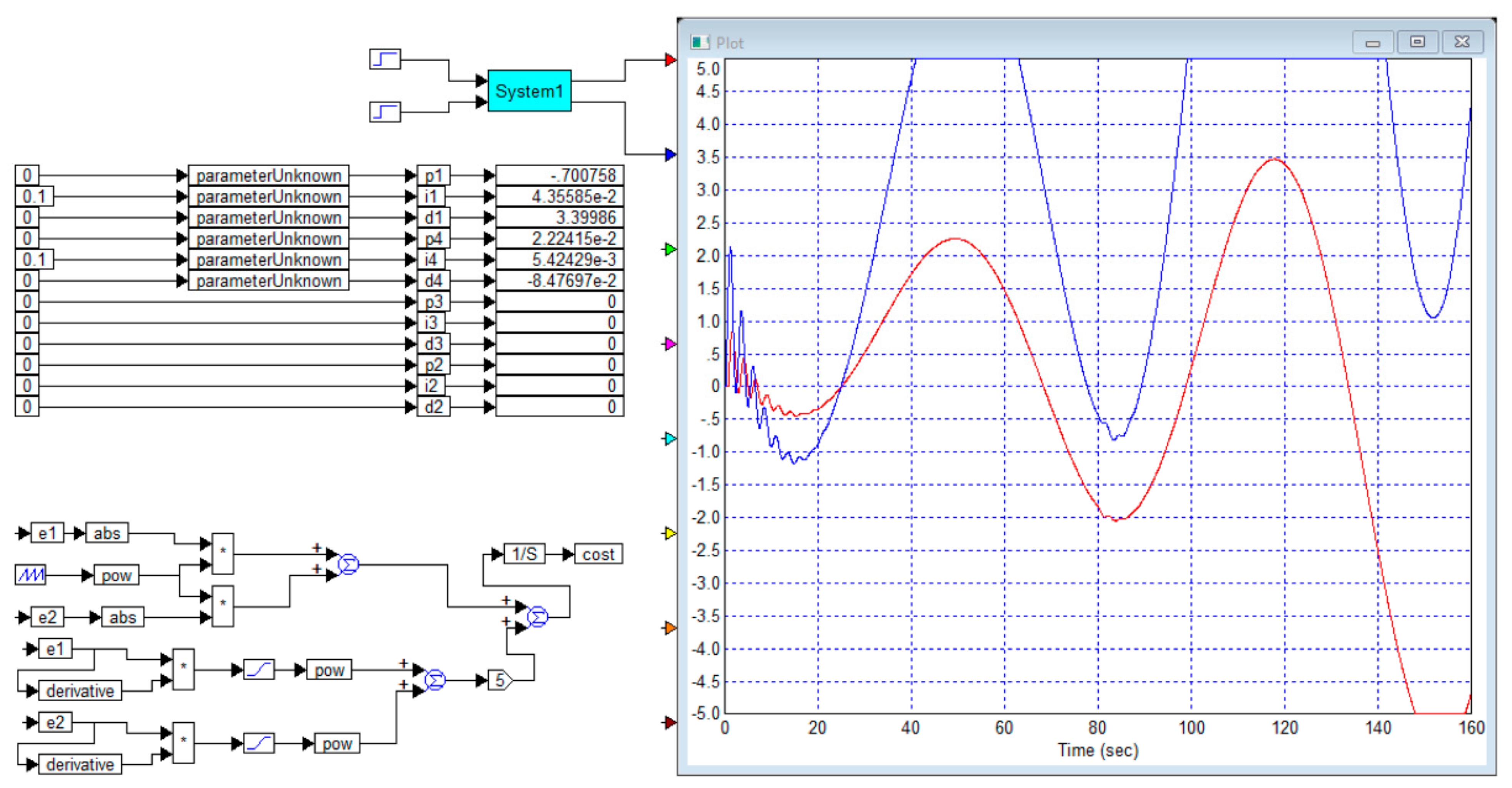

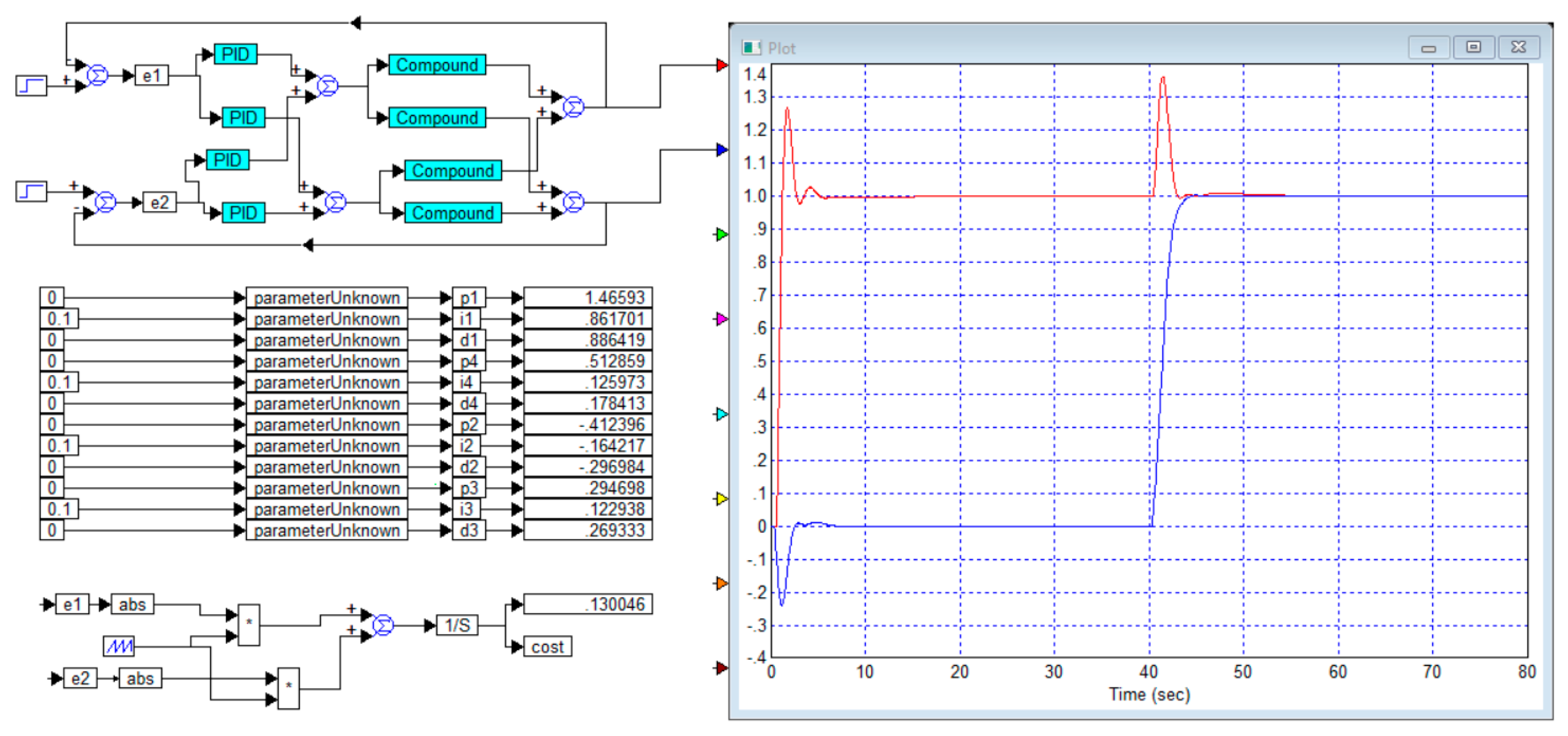

Figure 5 shows the result of an attempt to optimize the diagonal regulator controller for the object of Example 2. The attempt was unsuccessful, the system turned out to be unstable.

Figure 6 shows the project and the result of an attempt to calculate a full matrix PID controller for the same object from Example 2. A stable system is obtained. However, the quality of the obtained system is low. The overshoot in the first control channel reaches 98%. The overshoot in the second channel is 12%. The overshoot in the first channel with a jump in the second channel is 50%, the overshoot in the second channel with a jump in the first channel is 98%, and the reverse overshoot is about 50%.

In this case, the number of oscillations of all overshoots together with the first overshoot is at least four distinct oscillations. In addition, the duration of the process is very long, it is more than 60 s to the level of 5% and long residual relaxation processes of at least 40 s are also observed in the area of a small error. In addition, in the second channel, a second wave of response to a jump in the task of the first channel is observed, the peak of which is long and is between intervals of 20 s and 40 s.

From this example it should be concluded that, with an undesirable combination of all the parameters of the object model, multichannel control can be a rather complicated task. However, this case is clearly bad. In practice, such cases should not arise, since the designer should pay attention to the fact that in the secondary diagonal all elements of the matrix transfer function have a significantly larger value in the entire frequency range for the reasons indicated above. In this case, the designer should change the numbering of the outputs or the numbering of the inputs. To do this, the output of the first channel should feed the second input, and the output of the second channel should feed the first input. This will lead to the matrix transfer function of such an object, which will take the form given in Example 1, and this problem, as we have seen, is solved quite simply and successfully. This example shows that, along with formal methods for designing controllers, a preliminary analysis of the properties of the matrix transfer function of the object should be used to identify the strongest channels of influence. In this case, the first input has the greatest influence on the second output, and the second input has the greatest influence on the first output, which dictates the choice of the numbering rule for the outputs and inputs.

This approach is intuitive and should be used early in the design process, i.e., in advance. For example, we want to move a load from a tower crane in two directions and we have two settings, one for each arm. Let the left setting move the load strongly vertically but weakly horizontally and the right setting move strongly horizontally but have little effect on the vertical movement. When creating an automated system, we should choose the left setting to control the vertical movement and the right setting to control the horizontal movement. Complete separation will ensure that the left setting will only affect the vertical movement but will not affect the horizontal movement and the right setting will only control the horizontal movement but will not affect the vertical movement. If the designer takes the opposite approach and tries to make the left setting control the horizontal movement and the right setting control the vertical movement, then the problem will still be solvable, but it will be similar to the one considered in Example 2. That is, the least influential inputs are selected to control these quantities, which complicates the controller design and can negatively affect the control quality.

5.3. Two-Channel Object Without an Obvious Dominant Diagonal

Example 3. Let us consider an object whose transfer function has the following form: This transfer function is also obtained from the transfer function of Example 1 with appropriate permutations. In this case, in the first row, the most significant element is the element that is not on the main diagonal, and in the second row, the most significant element is on the main diagonal.

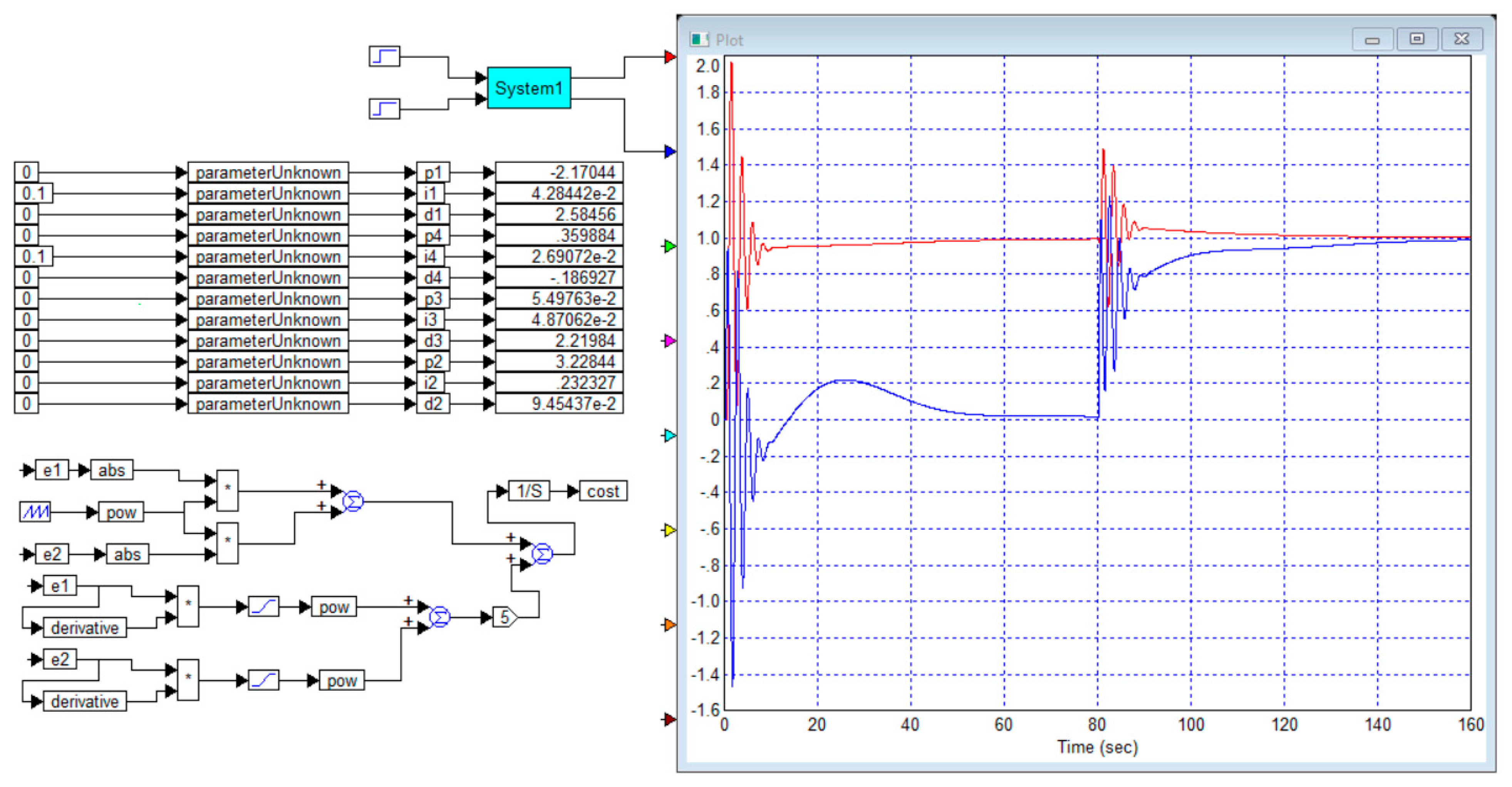

Figure 7 shows the structure project and the result of optimization of the full PID controller for such an object from Example 3. This system is stable, but the response of the second channel to the step jump of the first channel is too large. It reaches 75%, and its duration is 30 s. The response of the first channel to the jump in the second channel’s task is 14%, its duration to the level of 50% of the maximum value is less than 5 s, but the duration of its noticeable part is about 40 s. In this case, control for each channel is carried out without overshoot; the duration of the processes is from 40 s (for the second channel) to 60 s (for the first channel).

It is also advisable to try to control this object using a simplified diagonal controller.

Figure 8 shows the design and result of controlling the object of Example 3 using a diagonal controller.

In this case, the result is noticeably worse, but the resulting system is stable. The response of the second channel to the step jump of the first reaches 98%, and its duration is 50 s. The response of the first channel to the jump in the second channel task is 13%, its duration is about 40 s. In this case, control for each channel is carried out without overshoot; the duration of the processes is 50 s for each channel.

Example 4. Let us consider an object whose transfer function has the following form: This transfer function is derived from the transfer function of Example 3, with the difference that the elements in the minor diagonal are negative.

Figure 9 shows the design and optimization result of the diagonal controller for this case.

In terms of process quality indicators, there is no significant difference from the result presented in

Figure 8. Cross-reactions and emissions are comparable in size and duration.

Figure 10 shows the result of the design and optimization of the complete controller for the object of Example 4. Compared to the result shown in

Figure 7, it has a slight advantage, namely: in

Figure 6, the response of the output of the second channel to a jump in the setpoint at the input of the first channel is 75%, and in

Figure 10 the corresponding response is 61%. In terms of duration, these responses are comparable, both being about 50 s. The remaining indicators are also comparable.

5.4. Three-Channel Object with Slightly Dominant Main Diagonal

Note that in the literature we have not found reliable reports on solving control problems for three-channel objects that would provide mathematical models of the object with numerical values of the parameters and the result of the control. In this case, we could take these initial models and calculate regulators for them and compare the result with the result that would be presented in a similar article. A similar problem is solved in this article for the first time.

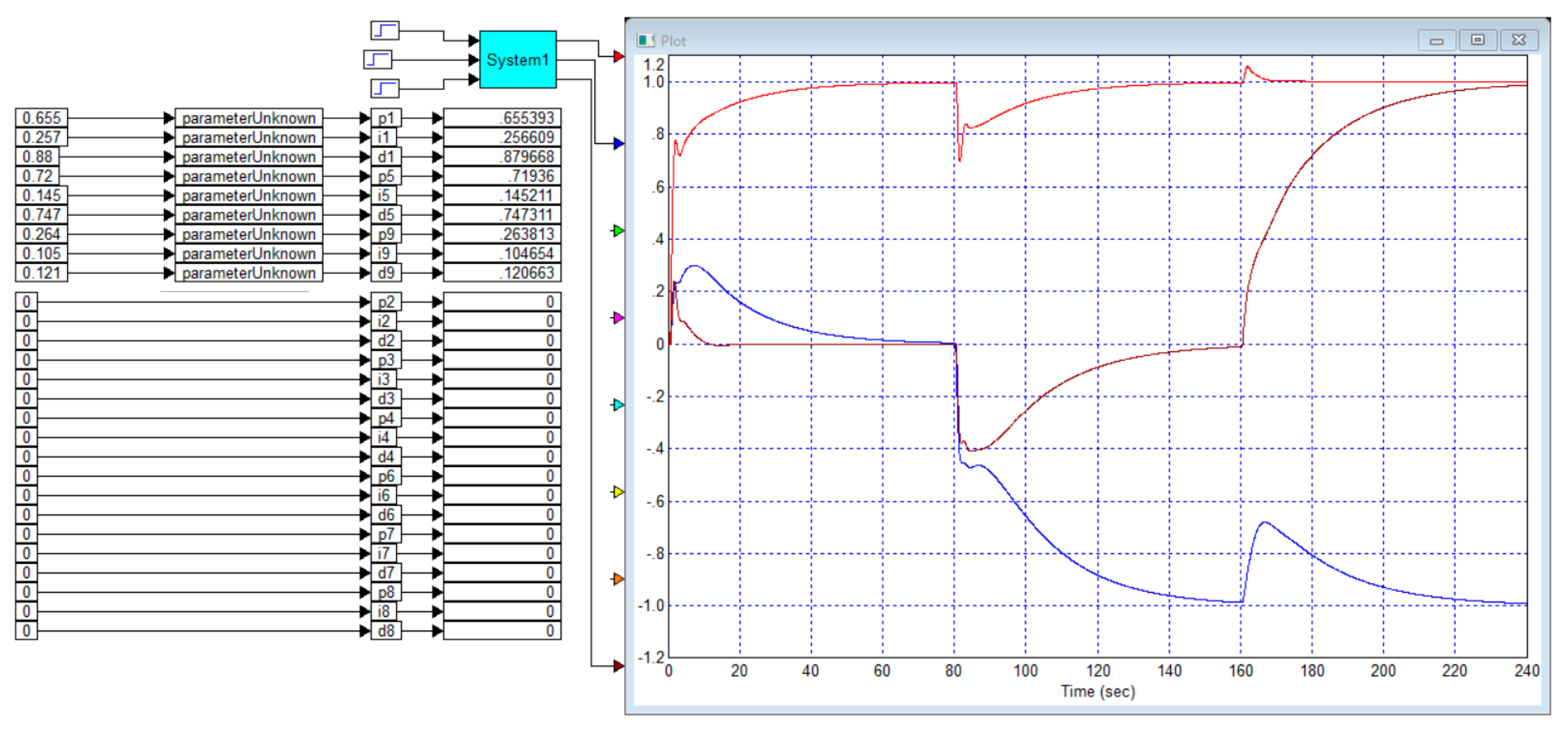

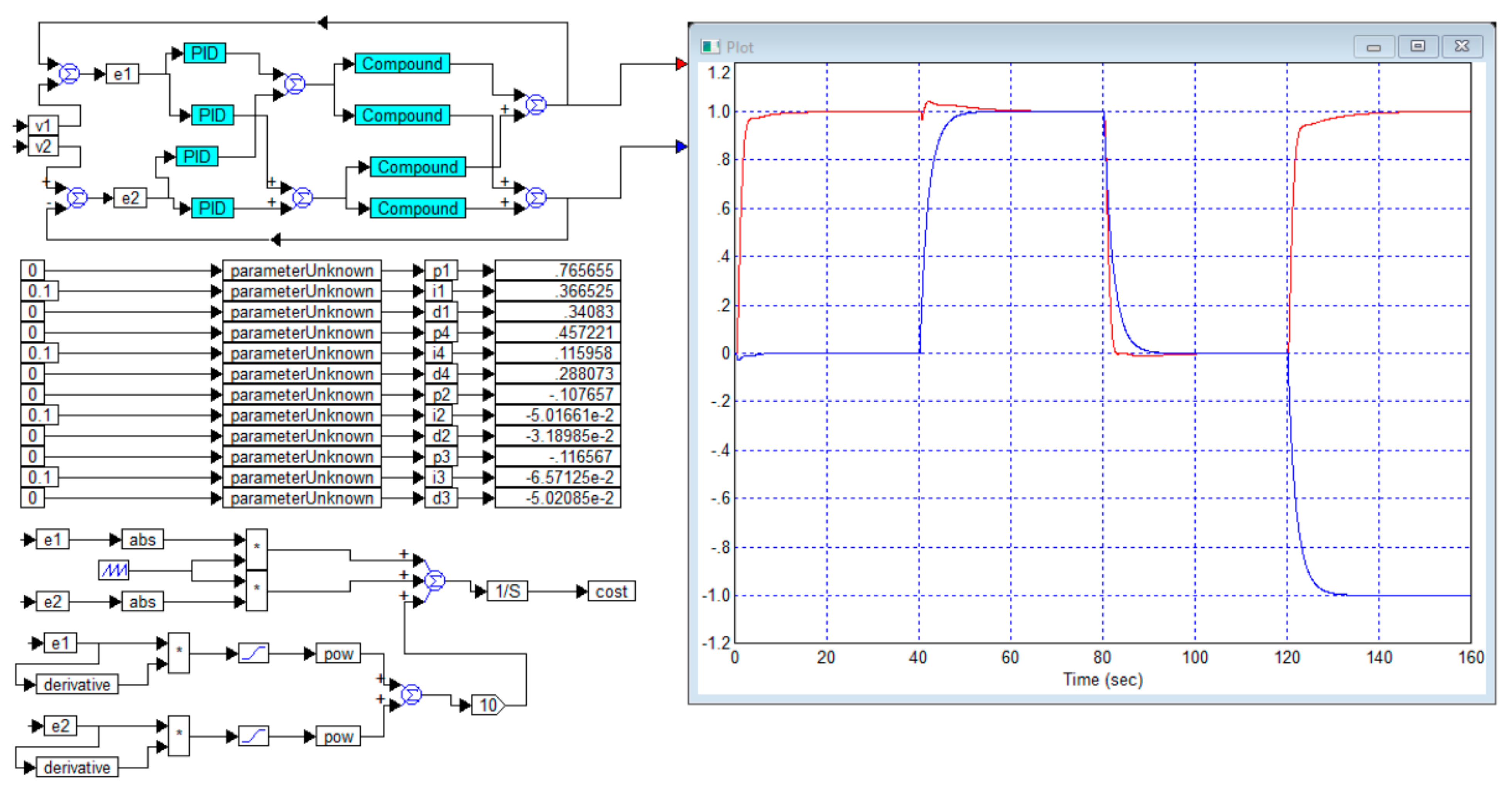

Example 5. Let us consider an object whose transfer function has the following form: As a test task, we will also use a vector consisting of time-shifted single jumps, but for a visual result, we will feed a jump with a negative value to the second channel:

Figure 11 shows the design and numerical optimization result of the controller for this example. The cost function calculator for this case is shown in

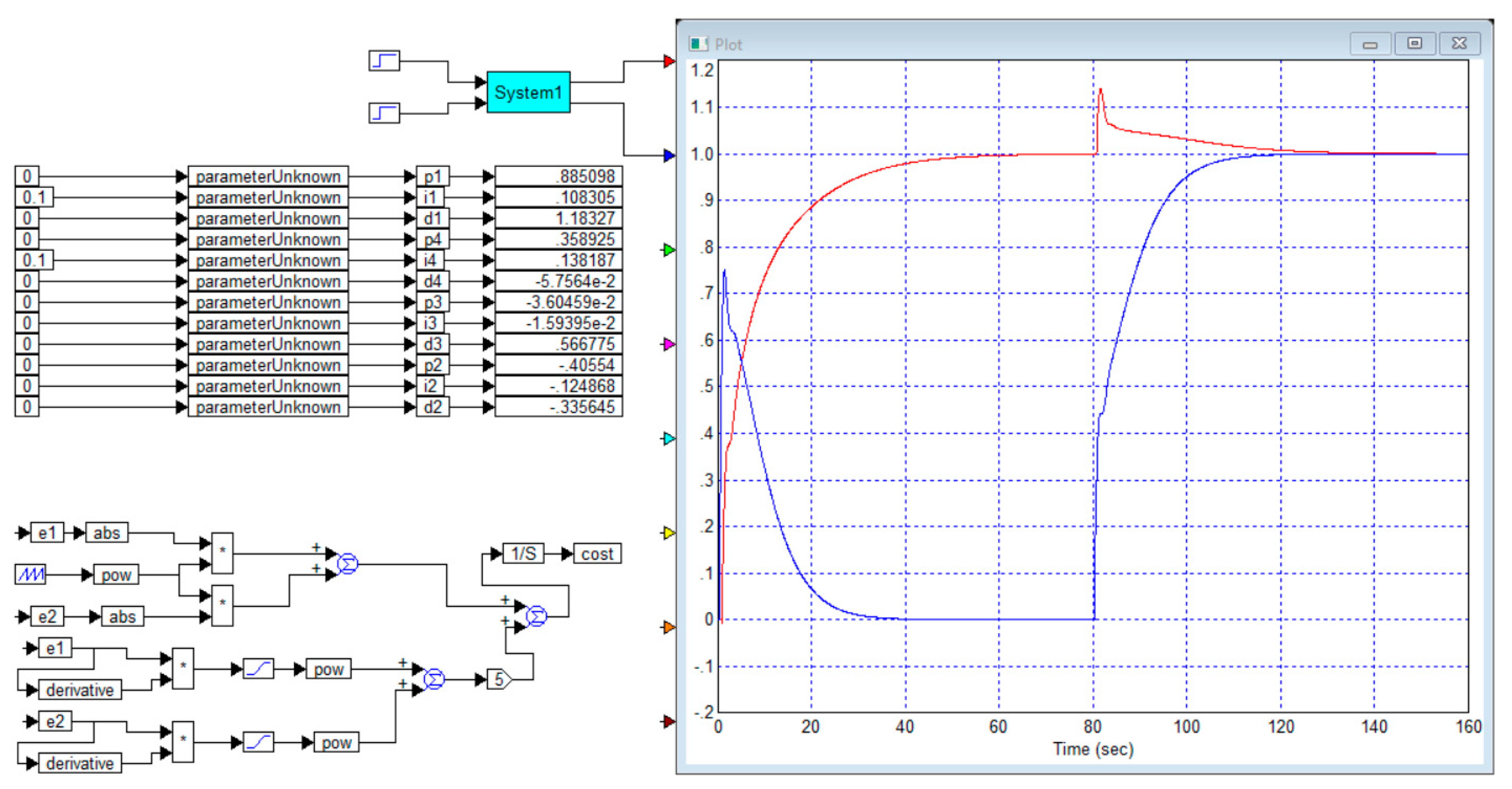

Figure 12. The parasitic response of the second channel reaches 45% with jumps in the first channel. The parasitic response in the first channel is 20% with jumps in the second channel. The parasitic response in the third channel with a jump in the second channel is about 36%, with jumps in the first channel of 40%. The overshoot in each channel is negligible.

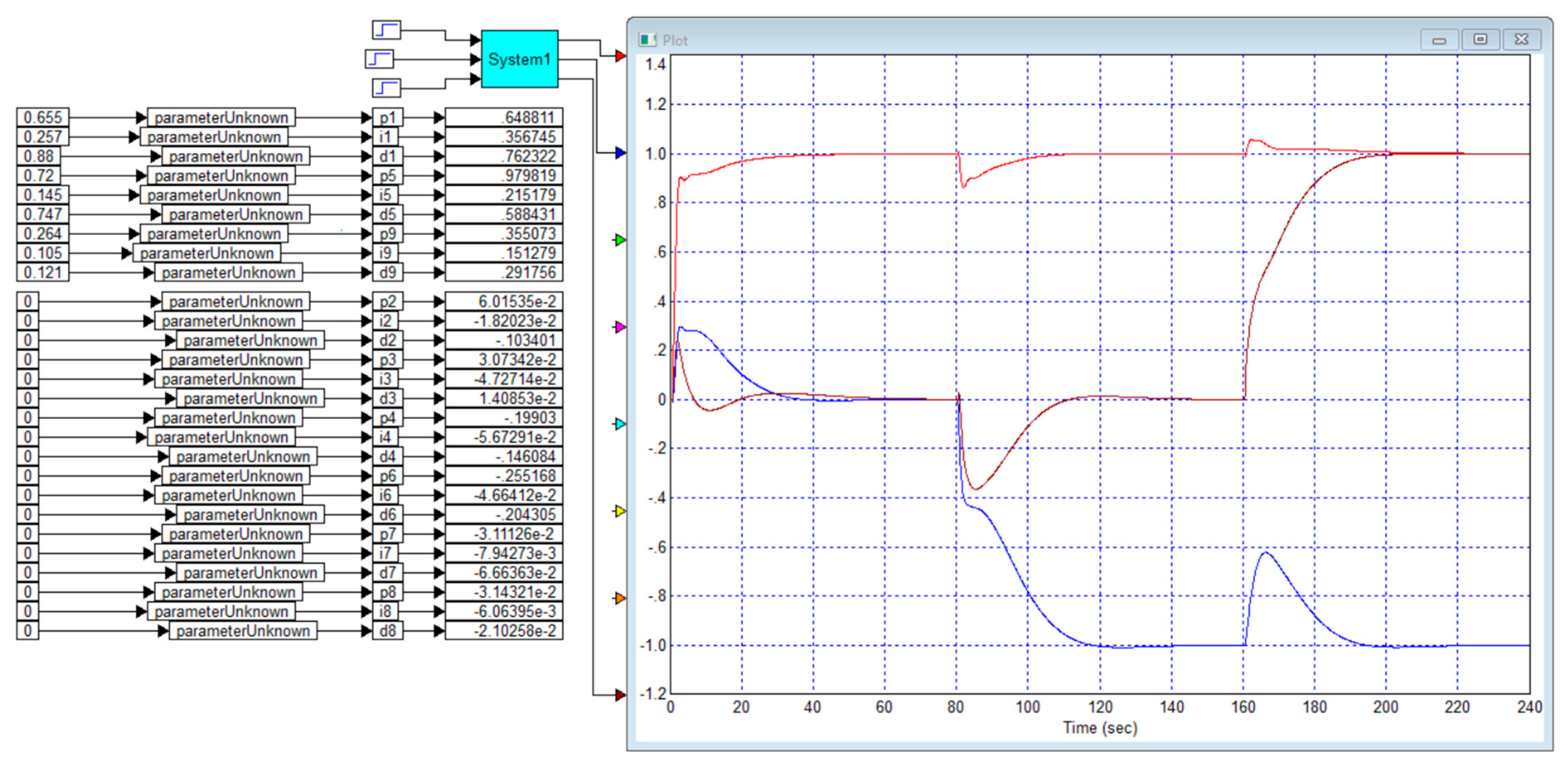

For comparison,

Figure 13 shows the design and optimization result of the diagonal regulator. It can be noted that the response in the first channel with a jump in the second channel increased by one and a half times, but the response in the same channel with a jump in the third channel decreased significantly. Also, the parasitic response in the third channel with a jump in the first channel decreased by two times. Thus, there is no reason to claim that in this case the diagonal regulator demonstrates a worse result than the full regulator.

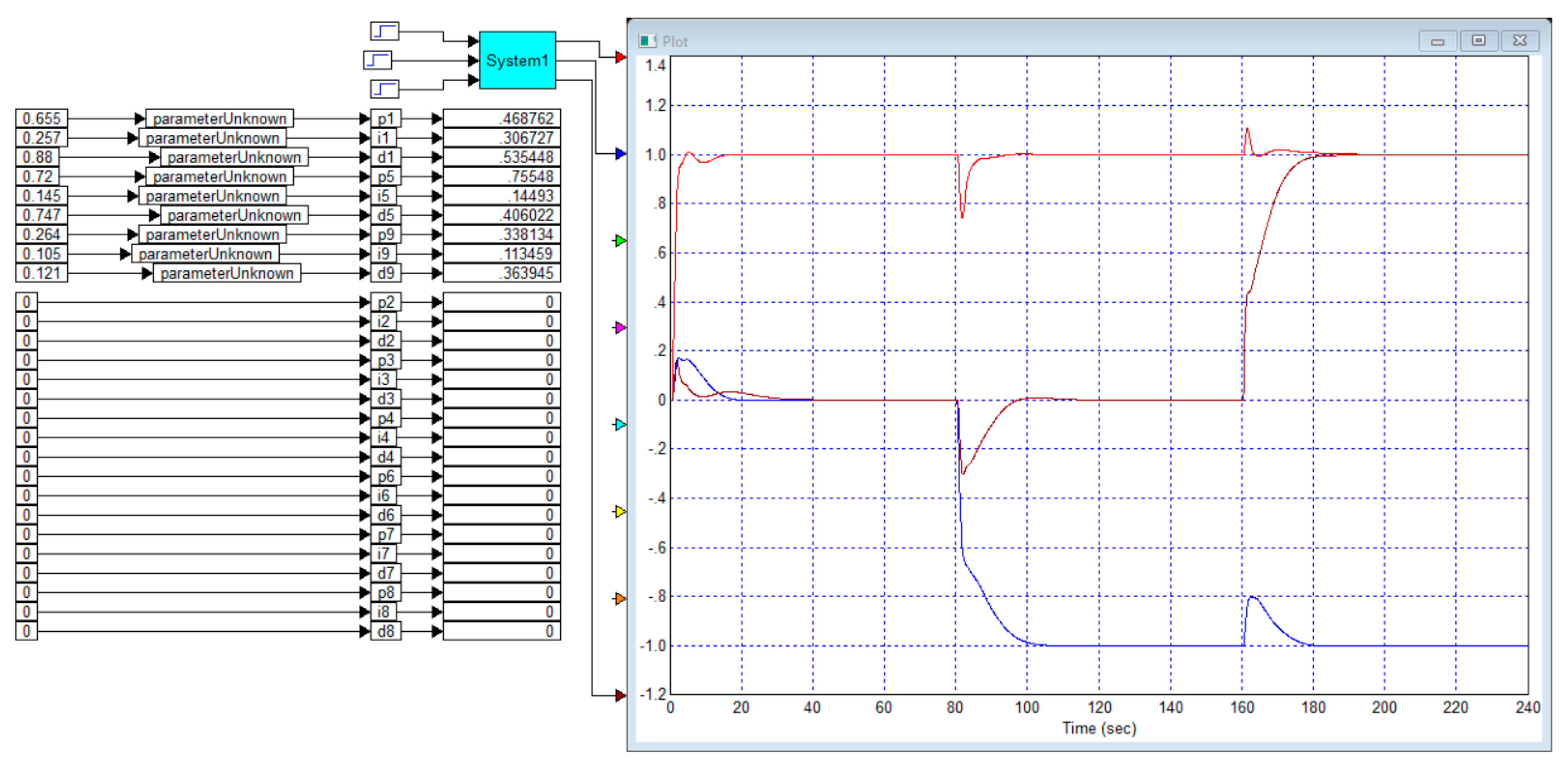

Figure 14 shows the project and the optimization result for the case where the weight coefficient of the second term in the cost function is reduced to an insignificant value

. In this case, the performance of each channel has increased more than twofold, parasitic responses have also increased by 1.5–2 times, and emissions of up to 10% have appeared in the first and third channels.

It is also possible to use the square root in the second term and the weighting factor, in this case

. The result for this case with a full controller is shown in

Figure 15, and

Figure 16 shows the result for this case with a diagonal controller. In terms of transient response quality, these two results differ only slightly from each other, and at the same time, they both differ quite significantly from the results obtained with the other cost function parameters shown in the previous figures.

This example shows that, in the case where the matrix transfer function of the control object is characterized by a slight predominance of diagonal elements in absolute value over the remaining elements, the result (expressed as transients for each channel separately) depends to a much greater extent on the parameters of the objective function during optimization than on whether a diagonal regulator or a full regulator is used. The use of nonzero elements in the matrix PID regulator does not allow a radical improvement in the quality of the transient process, which is determined mainly by a trade-off between speed and overshoot for all channels.

To obtain more complete information and substantiate the conclusions, we will calculate the regulator for a slightly modified object.

5.5. Three-Channel Object with a Clearly Dominant Main Diagonal

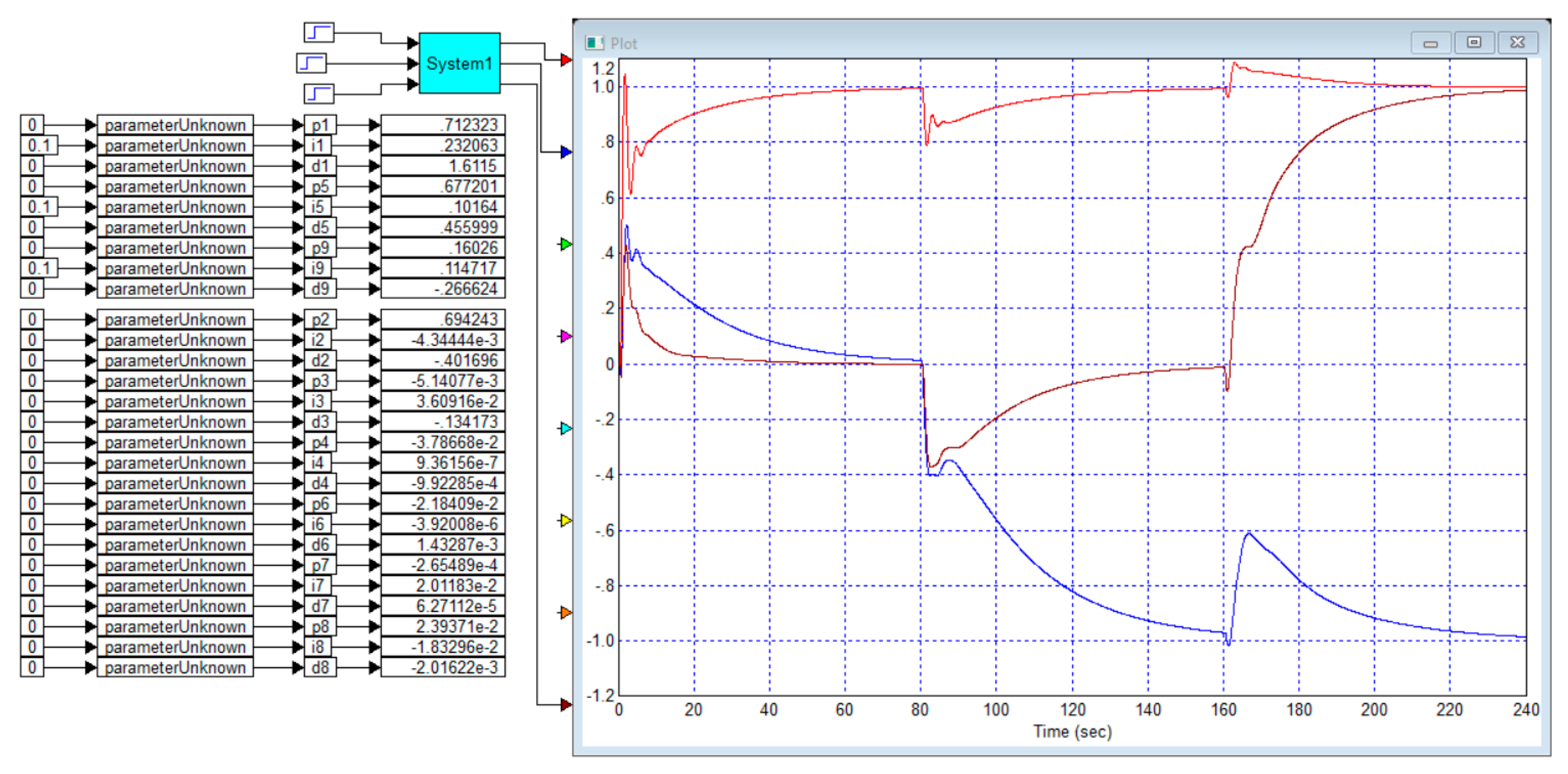

Example 6. We simply increase the coefficients at the main diagonal elements of the matrix transfer function of the object by approximately one and a half times. We obtain an object whose transfer function has the following form: The cost function and test signal in this case are the same as in Example 5.

Figure 17 shows the design and optimization result of the diagonal controller for Example 6. The quality of the resulting transient process in all three channels has improved significantly in this case. The parasitic response in the first channel varies from 10% to 13%, in the second channel it remains within 20%, in the third channel it varies from 18% to 30%. There is no overshoot in any channel.

Figure 18 shows the design and optimization result of the full controller for Example 6. The result is slightly better than in

Figure 17. All parasitic responses have become less than 10%, and the responses of the first and second channels to the task jump in the third channel are even less than 5%, and there is no overshoot in each channel either.

Based on this example, it can be argued that in the matrix transfer function of the control object there is a significant (two or more times) predominance of the values of the diagonal elements over the other elements. With a diagonal controller, acceptable control quality is achieved, and with a full controller this quality can be significantly (twice) improved.

This dominance can be called a majorizing property. It is expressed in the fact that each diagonal element is significantly larger in absolute value than the other elements in the same row of a given matrix.

5.6. Three-Channel Object Without Dominant Main Diagonal

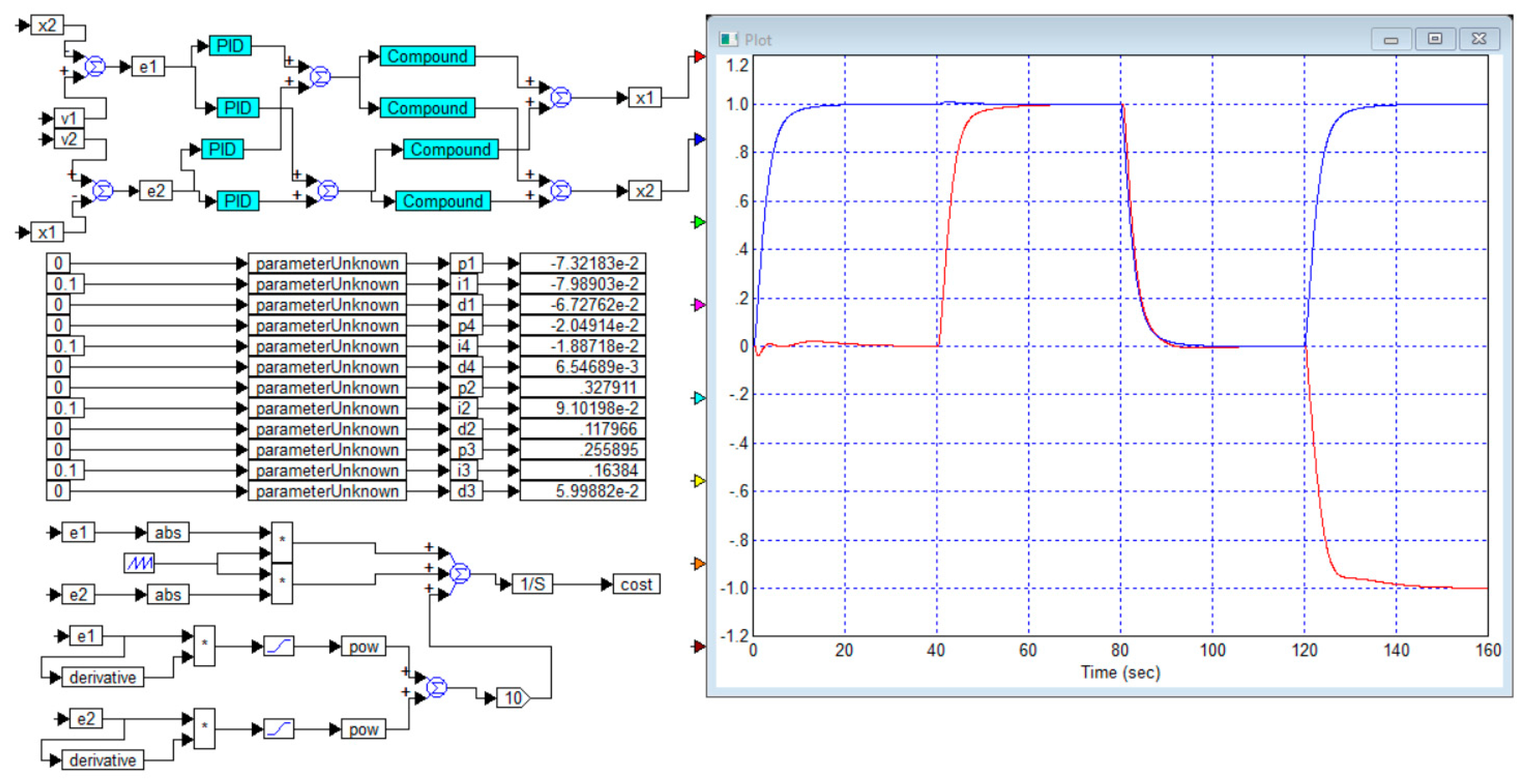

To make sure that dominance is important only in each row, consider another example based on the transfer function from Example 6, namely, we decrease the value of all coefficients in the first row by two times and increase the value of all coefficients in the second row by two times.

Example 7. We obtain an object whose transfer function has the following form: Figure 19 shows the design for optimization and the result for this case. The result is slightly worse in quality than the result shown in

Figure 17. This is probably due to the change in the relative influence of each channel on the other channels, as well as the effect of the result on the cost function.

If the designer is not satisfied with the quality of the transient process in a given channel, then an additional weighting factor can be introduced into the corresponding term of the cost function, depending on the error in that channel. For example, in this case, the quality of the response of the second channel is noticeably worse than the quality of the response of the other channels. The best response is in the first channel. The designer can introduce a factor of 3 in the second channel, a factor of 2 in the third channel, and leave a factor of 1 in the first channel.

Figure 20 illustrates the result. As we can see, we were able to reduce the parasitic responses in the third channel by increasing the parasitic responses in the first channel. This further demonstrates the dominant influence of the cost function during the optimization and its numerical coefficients on the result.

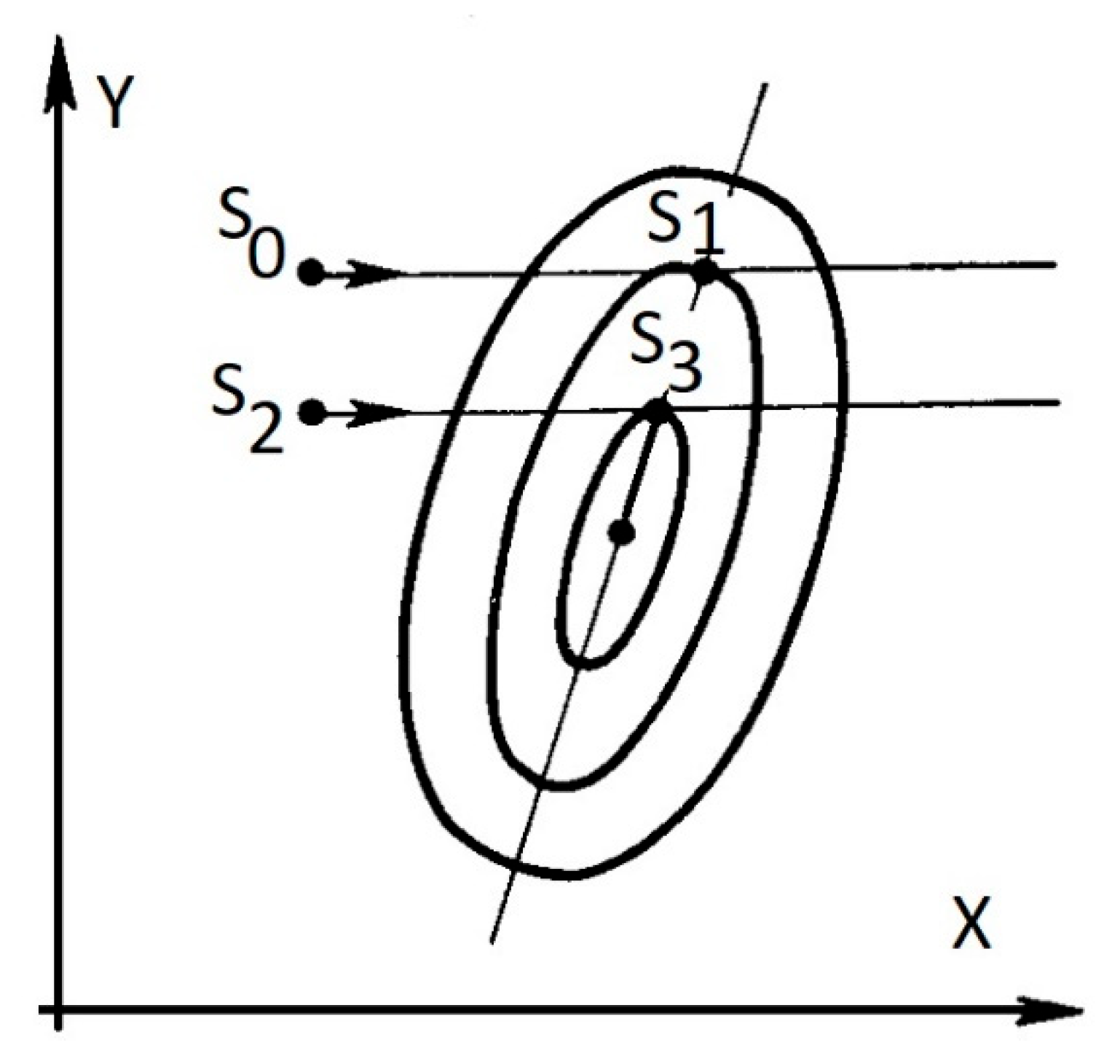

6. Method Modification: Ensuring the Requirements of Completeness of the Influence of Test Tasks

If we analyze the set of test signals used in the optimization, we can see that they are somewhat incomplete. Note that, with a step jump on one of the inputs, there is no jump on the other input. The optimization procedure provides better transients in these situations. However, the possibility of a simultaneous jump of the reference on both inputs, which can act together in such a way that an unacceptably large value is exceeded, is not considered. Such a situation can occur both when the signs of the reference jumps coincide and when they have opposite signs. To ensure completeness of all possible signal combinations, it is proposed to include in the set of test signals both the simultaneous application of in-phase jumps to all inputs and the simultaneous application of antiphase jumps to all inputs. For a 2 × 2 object, this gives two more jumps, and for a 3 × 3 object, this implies many more jumps in various combinations: in-phase and antiphase jumps on every two inputs in pairs, for a total of six jumps, for a total of nine jumps. The designer could also try adding in-phase jumps on all three inputs, and in-phase jumps on two inputs with an out-of-phase jump on the third input, for a total of four jumps. This gives a total of 13 different options, which seems overly complicated, so we recommend limiting it to nine jumps. We will demonstrate this method using the 2 × 2 object from Examples 1 and 2.

Example 8. Let us consider the object from Example 1 and apply the following set of test tasks to it: Figure 21 shows the design and optimization result for this case using the simplest cost function consisting of the integral of the sum of the squares of the product of the error modulus and the time since the start of the transient process.

At the same time, there are two large parasitic jumps in the second channel, namely, when there is a jump only in the first channel and when there is a jump unidirectionally in both channels simultaneously. However, other components of the complex transient process have improved. Importantly, in this case there is no overshoot in the second channel, and the parasitic jump during jumps in the first channel is also small, only 10%. For comparison, we present the result using only one jump on each channel. This result is shown in

Figure 22. In this case, a similar jump in the second channel is 25%. From this we can conclude that considering the set of all four types of jumps is more representative and, in this case, formally, the same cost function works differently.

It is noteworthy that for

in

Figure 21 the overshoot in the first channel is 60%, from which it follows that the simultaneous synchronous jump in the task on both channels is a strong exciting factor for the first channel. For

the response at the outputs of both channels is insignificant, which indicates that the antiphase jumps of the steps are not an exciting factor for both channels.

Finally, it is important to use both methods to improve the transient process simultaneously, namely, the test signal is as in Example 8, and the cost function is complete, as shown in

Figure 9.

Example 9. Figure 23 shows the design and optimization result using four jumps in each channel and a complex cost function that helps reduce overshoot. The result can be called ideal: there is no overshoot in all cases for all channels, the parasitic response in both channels is negligible. Thus, the full accounting of all variations of the system input signals significantly increases the efficiency of the optimization design of the controller. It is enough to compare this result with the result shown for the same case in Figure 3 and Figure 4—there the parasitic jumps in each channel were 10% with a duration of about 10 s. For this reason, it is worth considering how the optimization of the controller for the object obtained from Example 1 would be implemented. In this case, this is carried out by replacing the first output with the second and the second with the first. The case considered in Example 2 (the result is shown in

Figure 5) is extremely unsatisfactory: there is a large overshoot and a lot of flickers in each channel.

Example 10. Consider the object of Example 2 with test signals as in Example 8.

Figure 24 shows the design for this case and the result of the numerical optimization. The result exceeded all expectations. Despite the fact that in this case the elements of the main diagonal in the entire frequency range are smaller in absolute value than the elements of the nonmain diagonal, the result of the optimization shows excellent quality of the transients: there are no peaks, and the parasitic responses in each channel with jumps in the other channel are also negligibly small in value, no more than 1–2%.

This example particularly clearly shows that, when presenting requirements for completeness in the quality of transient processes (including the requirement that not only transient processes for each channel separately in the absence of jumps in the task for other channels have a sufficiently high quality but also of processes with simultaneous in-phase and simultaneous antiphase jumps at all inputs of the system), transient processes would also be characterized by high quality: little overshoot or its complete absence.

To evaluate the efficiency of the proposed method, it is sufficient to compare the graphs shown in

Figure 24 with the graphs shown in

Figure 3. In the first case, we solved the problem using the method that we previously published in articles [

37,

38]. In this case, there was no overshoot in the system for both channels, but the duration of the process in the first channel was 10 s, and the duration of the process in the second channel was 20 s. In addition, parasitic responses to a jump in the other channel arose in each channel. Such a response in the first channel was 8% with a duration of 20 s, and in the second channel it was more than 10% with a duration of 10 s. In the system that is optimized using the proposed method, the transient processes shown in

Figure 24 are distinguished by better quality. The duration of the transient process of the first channel is 10 s, the duration of the process of the second channel is 20 s, and there is no overshoot in both channels, but the response of each channel to a jump in the other channel is also practically absent. In the second channel, it is less than 1% and in the first channel less than 0.5%.

7. Discussion

As a result of the modeling and numerical optimization of two-channel complete and incomplete PID controllers, the following conclusions were made:

Particular attention should be paid to the ratio of the values of the elements of the main diagonal of the matrix of the transfer function of the object to the remaining elements of this transfer function. Signs of a larger value are: (a) a larger value of the gain coefficient; (b) a smaller value of the delay; (c) a smaller value of the time constant of the polynomial in the denominator. If these requirements are not met at least partially, it is advisable to check whether they will be met to a greater extent by replacing the numbering of the outputs with another correspondence of the outputs and inputs.