Featured Application

This study offers a practical model for integrating Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools into writing instructions for English as a Second Language (ESL) learners in secondary education. By blending the Writing Workshop Instructional Model (WWIM) with AI-powered platforms such as Grammarly and ChatGPT, the research presents a scalable, classroom-tested approach to enhancing students’ academic writing skills. The findings can be directly applied in bilingual and multilingual educational contexts where students struggle with coherence, organization, and writing confidence. Specifically, schools implementing project-based learning and following international curricula (e.g., Cambridge Assessment) can adopt this hybrid model to foster independent, ethical, and critical writing practices among learners. The approach is especially valuable for educators seeking to integrate AI in formative assessment, real-time feedback, and iterative revision cycles within structured pedagogy.

Abstract

Despite reaching intermediate English proficiency, many bilingual secondary students in Colombia struggle with academic writing due to difficulties in organizing ideas and expressing arguments coherently. To address this issue, this study explores the integration of AI-powered tools—Grammarly and ChatGPT—within the Writing Workshop Instructional Model (WWIM) to enhance students’ writing skills. Conducted at a bilingual secondary school, the intervention targeted 10th grade ESL learners and focused on improving grammar accuracy, textual coherence, and organizational structure. Drawing on Galbraith’s model of writing as content generation, the study adopted a design-based research methodology, incorporating iterations of implementation, feedback, and refinement. The results indicate that combining WWIM with AI feedback significantly improved students’ academic writing performance. Learners reported greater confidence and engagement when revising drafts using automated suggestions. These findings highlight the pedagogical potential of integrating AI tools into writing instructions and offer practical implications for enhancing academic writing curricula in secondary ESL contexts.

1. Introduction

The Writing Workshop Instructional Model (WWIM), developed by Graves in the early 1980s, is a process-oriented approach that emphasizes creativity, collaboration, and systematic learning. Although effective in its foundational design, traditional methods like WWIM encounter challenges in meeting the evolving academic needs of ESL learners. To address these limitations, Artificial Intelligence (AI)-powered tools such as Grammarly and ChatGPT have emerged as valuable supplements, gaining prominence for their ability to automate repetitive tasks, provide real-time feedback, and improve writing quality [1]. These tools align seamlessly with the core features of WWIM, including direct and concise instruction, student autonomy in topic selection, frequent writing opportunities, and a collaborative environment, fostering a hybrid approach that blends human oversight with technological assistance [2].

In addition, advanced AI tools like ChatGPT and Grammarly offer distinct advantages in enhancing writing skills. ChatGPT aids users in generating ideas, structuring text, and refining writing style, while Grammarly excels in improving grammar, punctuation, and clarity through context-aware recommendations [3,4]. For 10th grade students, these tools provide critical support by fostering a deeper understanding of language mechanics and encouraging iterative improvement. Moreover, the immediate feedback they provide empowers students to address errors and enhance coherence, ultimately leading to improved academic writing skills [5]. Therefore, the integration of these tools into educational practices has significantly influenced academic writing, reshaping how students approach composition and revision.

Furthermore, academic writing encompasses a wide range of styles, including narrative, descriptive, persuasive, expository, and creative compositions, all of which are essential across educational levels. These writing tasks not only aim to refine technical skills, but also foster the ability to craft clear and coherent texts. While WWIM, with its emphasis on iterative writing and peer feedback, has proven effective in supporting writing skill development [6], its application in improving academic writing among high school students in Colombia remains underexplored. This research gap highlights the need for further investigation into how such pedagogical approaches can be adapted to specific educational contexts.

However, the challenges associated with writing instruction persist due to its divergence from broader school objectives. Writing tasks often focus on isolated assignments rather than holistic skill-building, leaving teachers struggling to address writing as a multifaceted skill set that integrates cognitive and linguistic processes [7,8]. Furthermore, writing creatively in a second language adds another layer of complexity, as it requires high-level thinking and implicit linguistic proficiency. Nonetheless, students who approach writing with confidence and perseverance tend to achieve superior outcomes, underscoring the importance of cultivating these traits in the classroom [9].

Thus, the integration of AI tools with WWIM offers a promising solution to these challenges, bridging the gap between traditional pedagogies and modern technological advancements. By fostering a supportive environment that encourages both creativity and precision, this approach has the potential to enhance the academic writing proficiency of ESL learners, paving the way for more effective and inclusive writing instruction.

2. Literature Review

Writing is widely recognized as one of the most challenging language skills to acquire and teach due to its multifaceted nature, requiring high levels of linguistic, cognitive, and organizational proficiency [10]. This complexity is compounded by the necessity of learning new strategies while mastering language mechanics. The Writing Workshop Instructional Model (WWIM) addresses these challenges by fostering a supportive, student-centered environment that encourages skill development. Research highlights that structured workshops under this model lead to significant improvements in students’ confidence and coherence, although persistent challenges such as low self-efficacy and limited organizational abilities persist [9,11].

Moreover, writing workshops hold the advantage of cultivating positive attitudes toward writing, particularly among L1 learners [12,13]. Thus, Starfield and Hafner [11] demonstrated that WWIM enhances engagement and motivation by focusing on socioculturally relevant topics. Additionally, the model offers a structured approach where students draft, revise, and edit their work individually or collaboratively, benefiting from a systematic and iterative writing process [14]. The integration of AI tools such as Grammarly and ChatGPT further complements these efforts by addressing specific challenges like grammar, coherence, and vocabulary, ultimately helping students overcome writer’s block and refine clarity [15].

Furthermore, teaching writing requires addressing multiple skills simultaneously, including sequencing, spelling, re-reading, and argumentation [16]. WWIM provides an environment conducive to acquiring these skills while promoting self-confidence and fluency. However, the ethical challenges and potential over-reliance on AI tools necessitate careful integration, ensuring that human instruction remains central [5]. For English as a Foreign or Second Language (EFL/ESL) learners, WWIM presents numerous opportunities. Melgarejo’s [17] findings demonstrate its effectiveness in improving EFL writing skills by empowering students through topic selection, increasing their engagement and motivation. A systematic review of the literature confirmed the effectiveness of learner-centered learning methods in improving EFL learning and that they respond to the pressing need to adapt educational practices to meet the diverse learning needs of contemporary learners, as well as the positive impact on student motivation, and the development of essential skills for lifelong language learning. Finally, the authors also acknowledge the challenges specific to EFL contexts, and suggest areas that require further research, e.g., new proposals that offer practical insights into the design and implementation of new approaches to teaching English to non-native speakers [18]. Nevertheless, further emphasis on workshop structures and higher-order thinking development could strengthen these outcomes.

The structured stages of WWIM—mini lessons, independent writing, and sharing—further reinforce skill acquisition. During mini lessons, new strategies and procedures are introduced, while independent writing allows students to apply these techniques and utilize tools like ChatGPT and Grammarly. Sharing sessions build community, provide feedback, and boost confidence [19]. This collaborative approach enables students to explore personal interests while improving their sense of audience, thereby fostering stronger writing capabilities [20]. Ultimately, the implementation of WWIM within a supportive and engaging environment significantly enhances students’ performance, enabling them to become confident and effective communicators.

To better situate the present study within the evolving field of AI-assisted writing instructions, Table 1 summarizes a selection of recent and representative empirical works. The table outlines each study’s educational context, methodological approach, and key findings, while highlighting how they relate to or differ from our research focus. This synthesis underscores the novelty of combining AI-based feedback tools with structured instructional models such as WWIM in secondary ESL settings, a dimension still underrepresented in the literature.

Table 1.

Selected relevant studies.

Balancing Opportunities and Ethical Concerns in AI Integration

While AI-powered tools such as Grammarly and ChatGPT offer significant pedagogical potential in enhancing writing fluency, accuracy, and metacognitive reflection, their integration into ESL instruction also prompts critical ethical and methodological considerations. Studies—such as Tsai et al. [25]—report significant improvements in grammar accuracy, vocabulary retention, and learner engagement when AI is utilized within structured frameworks. Concurrently, systematic reviews [26] underscore concerns including algorithmic bias, data privacy, over-reliance on automated feedback, and diminished critical thinking if AI tools are adopted without appropriate pedagogical mediation.

Recognizing these dual dimensions, this study positions AI as a supplementary scaffold rather than a replacement for teacher-led instruction. Our hybrid model emphasizes pedagogical guidance, embedding AI-driven feedback within a Writing Workshop Instructional Model (WWIM) that includes classroom dialogues, iterative revision cycles, and critical reflection tasks. In doing so, we aimed to harness AI’s immediate corrective benefits while mitigating risks related to authorship, academic integrity, and learner autonomy.

3. Research Gap, Questions, and Aims of This Study

Although the Writing Workshop Instructional Model (WWIM) has been widely implemented and studied across international educational contexts [27,28], its application within Colombian secondary education—particularly in English as a Second Language (ESL) settings—remains notably underexplored. Most research conducted in Colombia and other similar contexts has concentrated on lower-order writing skills [29], such as spelling [30], vocabulary use [31], and sentence-level grammar [32], often neglecting more complex aspects of academic writing like content development, organizational structure, textual cohesion, and coherence [17]. This limited focus poses a significant gap in the literature, as it fails to address the holistic set of competencies required for academic success in bilingual environments. The lack of emphasis on advanced writing conventions leaves both students and teachers without structured, evidence-based models for developing higher-level writing proficiency in English.

At the same time, while recent studies have highlighted the potential of AI-powered tools to enhance writing performance—particularly in relation to grammar, coherence, and stylistic refinement [1,5]—their integration into formal instructional frameworks in secondary ESL contexts remains insufficiently documented. Most of the existing research has centered on higher education or adult learners in autonomous or exploratory settings, offering limited insights into how these tools can be effectively incorporated into established pedagogical models like WWIM. For instance, although students increasingly rely on AI feedback mechanisms such as Grammarly and ChatGPT to support revision processes, there is a lack of empirical evidence on how adolescent learners interpret, apply, and reflect on this feedback within structured, teacher-guided writing workshops. This gap is particularly salient given the cognitive and linguistic demands associated with academic writing in a second language, and the need for scaffolding strategies adapted to learners’ developmental stages and linguistic profiles [15,33,34].

To address this dual gap—both pedagogical and technological—this study investigates the combined use of WWIM and AI-powered writing tools in a bilingual secondary school in Colombia. The research aims are threefold:

- -

- To assess the extent to which AI-powered tools (Grammarly and ChatGPT) enhance ESL learners’ academic writing skills, particularly in terms of grammar accuracy, coherence, and organization;

- -

- To examine how students interact with and incorporate automated feedback into successive writing drafts when working within the WWIM framework;

- -

- To identify pedagogical affordances and limitations that emerge from the integration of AI-driven formative assessment with structured writing instruction in secondary ESL education.

Research Question

The central research question guiding this study is as follows: To what extent does the integration of AI-powered tools within the Writing Workshop Instructional Model (WWIM) support the development of academic writing skills—specifically grammar accuracy, textual coherence, and organization—among 10th grade ESL students in a bilingual secondary school setting?

4. Method

This study builds on the action research framework of WWIM, incorporating AI tools to evaluate their combined effectiveness. Key instruments included pre- and post-tests, scoring rubrics, and writing evaluation forms, adapted to assess both traditional and AI-assisted writing skills. Workshops integrated AI functionalities like grammar checks and citation management to enhance the learning experience. Initial observations identified a lack of confidence and low academic writing skills in English as key areas for intervention [35]. The iterative action research plan utilized WWIM to promote best writing practices among participants.

Participants were asked to write 250-word argumentative essays at the beginning and end of the academic year. Over the course of the year, the 10th grade class participated in six writing workshops, each lasting 50 min, during their weekly English sessions. The effectiveness of WWIM was evaluated by comparing the pre-test and post-test essay scores.

4.1. Participant Demographics and Context

This study employed a mixed-methods classroom-based action research design, conducted collaboratively in a bilingual private secondary school located in Colombia. The research was carried out during the second academic semester of 2023 and focused on a single 10th grade group enrolled in an ESL academic writing course.

The sample consisted of 26 male students, aged between 15 and 16 years. Participation in the study was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained from students and their parents or legal guardians prior to data collection. Ethical approval was granted by the school’s internal review board. Anonymity and data confidentiality were ensured by assigning coded identifiers to participants and storing the data in a secured, encrypted digital archive accessible only to the research team.

One of the researchers served as the teacher for the Global Perspectives course, which the students attended twice a week in 50 min English sessions. This course is part of the Cambridge Assessment International Education (CAIE) curriculum and incorporates Project-Based Learning.

At the school where the study was conducted, students in the senior grades (10th and 11th) were required to submit an annual Individual Report, while using Grammarly and ChatGPT platforms [1], and which was assessed according to Cambridge’s guidelines as part of the international testing system, ultimately checked by the Turnitin program.

The data collection process for this study relied on multiple instruments, including pre-tests, post-tests, Scoring Rubrics, and Writing Evaluation Forms. These tools were implemented to ensure reliable and validated data for both analysis and comparison within the action research project. At the beginning of the intervention, students completed a pre-test essay based on the prompt “Do you agree or disagree that having different lives depends on the kind of family support they received during their childhood?” At the conclusion of the sixth workshop (WS#6), students undertook a post-test to evaluate their writing skills after the intervention, using the prompt “These days, many people have their own computer and telephone, so it is quite easy for them to do their job at home. Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of working at home.” The data gathered from these tests provided a foundation for assessing progress.

The Scoring Rubrics Form, adapted from Oshima and Hogue [36], offered a comprehensive evaluation framework to assess writing proficiency across multiple dimensions, from basic mechanics to more advanced composition skills [37]. Students were categorized into four proficiency levels—below level, average, intermediate, and advanced—based on their performance. Below-level writers produced simple sentences with frequent errors, while average-level students demonstrated basic control over mechanics and layout. Intermediate writers showed greater detail and some planning, whereas advanced writers excelled in coherence, grammar, and detailed descriptions [16].

Each rubric category was assigned a specific weight, contributing to a grand total score of 70 points, which was converted into the school’s scoring range of 1.0 to 7.0. The evaluation criteria included layout (maximum 5 points), mechanics (6 points), content (15 points), organization (15 points), cohesion (12 points), coherence (12 points), and grammar and vocabulary (5 points). For instance, layout required correct margins, spacing, and formatting, while mechanics assessed proper punctuation and capitalization. Content and organization evaluated the ability to construct meaningful and structured paragraphs, supported by evidence and logical flow. Cohesion and coherence ensured connections between ideas and adherence to the prompt, while grammar and vocabulary measured linguistic accuracy and complexity.

The Scoring Rubrics Form played a pivotal role in identifying students’ strengths and areas for growth. Developing a robust assessment plan was essential for understanding the effectiveness of the WWIM intervention. As Graves and Xu [38] observed, continuous assessment during writing workshops provides valuable insights into learners’ progress, and supports targeted instructional strategies, making it an indispensable part of this study.

4.2. Action Planning and Implementation

These reflections emerged collaboratively during the sharing phase of the workshops, as students engaged in group discussions guided by teacher prompts. Following the principles of action research, the study involved a cyclical implementation of six writing workshops designed to integrate AI-powered tools into the Writing Workshop Instructional Model (WWIM). The researchers collaboratively planned, enacted, and reflected on each cycle to document both the learning process and the pedagogical adjustments required to support ESL students in improving their academic writing through AI-mediated feedback.

Eventually, students were explained that all household tasks, written assignments, checking Grammarly platform, ensuing editing essays, and collaborative activities will be scored at the end of each workshop. These 50 min workshops followed a predictable pattern divided in four stages: 1. mini lesson (5–10 min), 2. independent writing (20–30 min), 3. conferring (during independent writing and comprises: partner work, strategy group lesson and conferences); and finally, 4. sharing (5–10 min).

To operationalize the integration of AI into the writing workshops, students were trained to use Grammarly and ChatGPT as formative feedback tools at different stages of their writing process. Grammarly was primarily used after the first full draft, offering feedback on spelling, punctuation, grammar accuracy, word choice, and sentence clarity. Students received color-coded suggestions and were instructed to review each recommendation critically, accepting or rejecting it based on classroom discussions about accuracy and style. ChatGPT was introduced earlier in the process, mainly during the pre-writing and initial drafting phases. Students were guided in generating prompts to obtain feedback on structure, paragraph transitions, idea development, and tone consistency. For example, learners used ChatGPT to request alternative phrasings or to inquire about ways to improve the clarity of their topic sentences. Teachers reviewed the AI outputs with students to foster critical thinking and raise awareness about the reliability and contextual appropriateness of suggestions.

Each workshop concluded with a peer editing session where students reflected on the feedback received from AI tools and revised their drafts accordingly. These revisions were tracked using version comparison tools and later evaluated with rubrics focusing on organization, coherence, grammar accuracy, and style improvements.

The timetable of the writing workshop sequence is depicted in Table 2, and shows the six workshops aimed to teach participants how to write a paragraph (WS#1), write an introduction (WS#2), and write a conclusion (WS#3). Then, students learned how to include citations and quotations (WS#4). Finally, in WS#5 and WS#6, learners wrote entire essays individually and collaboratively, using CMC/ICT tools (Computer-Mediated Communication and Information Communication Technology), also checking Grammarly and ChatGPT platforms [1] and applying what they had learned before.

Table 2.

Writing workshops’ sequence timetable.

4.3. Collecting Data and Procedure

At the beginning of this pedagogical intervention, the researchers were concerned about the length of the data collection instrument for scoring and its complexity after implementing the 6 workshops. Regardless of these uncertainties about how data were collected, the original data collection instrument called Writing Evaluation Form was a handy and accurate tool to collect, analyze, interpret, and assess all scores and grades collected throughout the 6 workshops.

This original-designed tool aims to connect categories that emerged during the diagnostic stage:

- Participants were identified with a code/number (in this case, there is a row-hidden name to preserve student’s identities);

- The categories, topics and subordinate topics were derived from the ones obtained during the diagnostic stage;

- Results per categories, topics and subordinate topics were included within the Scoring Rubrics Form;

- Final scores (in the bottom line) were the grades that each student got in the Global Perspective subject at school that ranges from 1.0 to 7.0 based on their academic performance.

Finally, the purpose of the Scoring Rubrics Form was to assess students’ academic written skills, their ability to practice all techniques taught in the six workshops to improve their overall writing competencies, and finally to be focused on a wide range of writing scales from mechanics to more complex written composition [37].

5. Results

5.1. Pre-Test Results

For this research study, data were collected from participants through a pre-test research design table to establish a baseline measurement and compare it to post-test measurements to compare all frequency scores acquired by the essays written by participants.

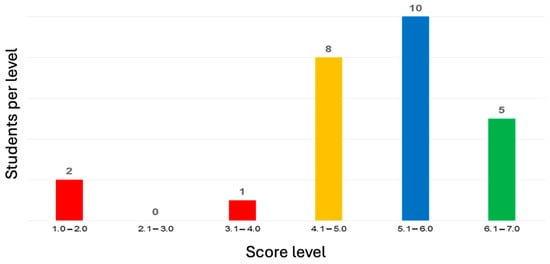

Figure 1 shows that during the pre-test, only 5 students scored between 6.1 and 7.0; 10 learners got scores between 5.1 and 6.0; then, 11 students failed the writing activity, since 8 students scored between 4.1 and 5.0, 1 student got between 3.1 and 4.0, and 2 scored between 1.0 and 2.0, which means several deficiencies about writing abilities among those students in the five rating categories assessed.

Figure 1.

Frequency scores of the pre-test.

As researchers, we scored independently the pre- and post-test writing activities of each 26 students adapted from the ESL Composition Profile. The rubric has five different rating categories of writing quality with a 70-point scale. These rating categories were content and organization (30 points), cohesion and coherence (24 points), grammar and vocabulary (5 points), layout (5 points), and mechanics (6 points).

The inter-rater reliability was calculated for scores on each component, with average agreement being 89%, ranging between 77% and 99%. The scores of the five rating categories are labeled and numbered from poor (1), fair (2), good (3), very good (4), and excellent (5), then summed and averaged to give each student’s final scores.

5.2. Post-Test Results

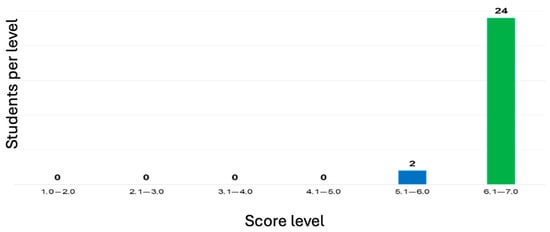

The writing abilities among 10th grade students in the five rating categories were assessed by comparing the initial state (pre-test) to their state after writing their essays (post-test). Figure 2 shows the scores in the post-test applied when implementing the final workshop.

Figure 2.

Frequency scores of the post-test.

After applying WWIM, it was evident that 10th graders improved their writing skills significantly, since 24 students scored between 6.1 and 7.0, and only 2 students got scores between 5.1 and 6.0.

5.3. Overall Results

Descriptive statistics for each of the five rating category scores from the pre-test and post-test research design were calculated for the whole group. As observed, the improvement and benefits provided to the 26 students while applying the writing strategy through WWIM and using AI’ tools were remarkable, rendering the results we got at the end.

Table 3 shows the mean, mean difference, and paired SD scores for the five rating categories, and the overall total for the students’ pre-test and post-test. Using paired-sample t-tests, the six paired scores were compared to determine improvement in students’ writing ability between pre- and post-test. For all five paired component scores, there were significant differences between the pre- and post-tests at the p < 0.01 level. By conventional criteria, for the students’ pre-test and post-test, this difference is an extreme statistically significant improvement in total scores [t (25) −3.6613, p < 0.01].

Table 3.

Pre-test and post-test comparisons for the categories and total score.

This study considered the effects of WWIM on students’ English academic writing. It was expected that there would be significant improvements in students’ writing, since the six workshops were designed to help students’ writing development through a collaborative learning setting. The pre-test and post-test score comparisons for the five rating categories and total score in Table 3 indicated that WWIM had a positive impact on the 26 participants.

There were significant improvements in average scores between pre-test and post-test on all five rating categories, as well as the total scores (pre-test = 17.0 and post-test = 24.4). These results are consistent with the scaffolded teaching–learning environment provided through writing workshops which support improvement in students’ academic writing skills [39,40].

In addition, it was also intended to determine the impact of WWIM in content and organization in argumentative essays. The biggest significant mean difference was between pre-test and post-test for the content and organization rating category.

This improvement may be attributed to students being better prepared cognitively, enabling them to manage the self-regulatory demands of writing and organize their ideas more effectively. As they increased ownership of their writing through the workshop process; students became better writers because they developed control of the mechanics and layout components, and could dedicate their attention to content and organization [41].

Regarding over-expanding the use of cohesive and coherent argumentative essays after applying the WWIM, results in Table 2 indicated that there were significant mean differences in the mean scores between the pre-test and post-test for the cohesion/coherence category on all five rating categories, the third best difference being pre-test = 3.8 and post-test = 5.2. This difference in impact could be explained because students wrote coherent paragraphs and coherent essays, adding enough vocabulary and connected ideas, and developing complex sentences with few writing errors.

Consequently, confidence increased significantly according to the significant improvements in students’ writing; as researchers can infer that students successfully found positions to express their ideas sequentially while dealing with the mechanics (grammar, punctuation, and spelling).

After attending the WWIM implementation, learners revealed being active writers because they currently have the necessary writing strategies, academic knowledge, and skills to write more confidently and independently. These strategies encompass understanding prompt questions, engaging with complex ideas, utilizing validated data, crediting authors, paraphrasing, and summarizing, which are integral components of the cognitive processes involved in writing [42].

5.4. Interpretation and Analysis of the Results

5.4.1. Reliability and Validity

The reliability of the data displayed in Table 2 for the quantitative data in this study relied on to establish the later findings was calculated based on the Pearson’s correlation coefficient (R); the value of R was 0.0613. Therefore, among 10th graders who participated in this study, the scores on the five writing components and the overall total for the students’ pre-test and post-test writing activities were positively correlated: r (26) = 0.0613, p < 0.001.

The validity of the data in Table 2 for the quantitative data in this study relied on the Spearman correlation coefficient (RS); the value of RS was 0.24827. By normal standards, the association between the two variables (pre-test and post-test results) confirmed a positive relationship as values of one variable increase, values of the other variable also increase. Hence, scores by participants on the five writing components and the overall total during the pre-test and post-test writing activities were positively correlated: RS = 0.24827, p (two-tailed) = 0.43653.

5.4.2. Qualitative-Based Results

This study showed the positive effects of WWIM on 10th grade students’ content, organization, writing confidence, and awareness of cohesion and coherence. AI tools enhance efficiency, provide real-time feedback, and improve overall writing quality. Students appreciate AI tools for their role in grammar checks, plagiarism prevention, and deadline management. These improvements were evident in their writing outcomes throughout the six-workshop sequence.

Combining AI with personalized learning through WWIM enables students to refine writing skills while addressing diverse educational needs. The final post-test scores also indicated significant advancements in academic writing abilities, as evidenced by improved writing techniques, a questioning attitude, and a critical mindset in their papers. The following discussion highlights the key findings of this study. However, over-reliance on AI tools risks diminishing critical thinking skills. Schools should integrate structured AI training, ensure equitable tool access, and promote ethical usage. AI tools should supplement, not replace, human critical thinking and creativity in research [43].

5.4.3. Content and Organization of Essays

The study aimed to enhance content and organization in the essays of 10th grade students. Initially, students struggled to formulate ideas, provide supported arguments, and adhere to proper theoretical layout. WWIM significantly improved students’ ability to structure coherent essays, an area further reinforced by AI tools. Students reported better organization and confidence, with one noting, “AI tools helped me understand how to create logical transitions and develop my essay”.

Students successfully applied the writing fundamentals learned in school and demonstrated significant improvements in their ability to generate original ideas and connect them coherently from introduction to conclusion. One student commented on the importance of organization: “I learned to summarize my ideas in my conclusion and how each idea has to be a paragraph in the essay too. It helped me learn how to keep everything well organized rather than mixed or messy and hard to read.”

Another student emphasized the value of paragraph structure: “The sentences and their types, as well as the authors’ quotations and the paragraph’s structure, were the ones I feel I learned the most and find the most useful when making a brief essay or text.” These findings align with Hyland’s [44] research, which suggests that English for Specific Purposes (ESP) emphasizes content and organization more than polished writing style.

5.4.4. Logical, Consistent, and Coherent Essays

The study also aimed to improve students’ logical, consistent, and coherent writing. The student-centered approach of WWIM fostered a collaborative learning environment that supported these improvements. AI tools like ChatGPT provided valuable suggestions for improving essay coherence, enabling students to focus on content while receiving automated feedback on mechanical errors. This aligns with findings that AI tools enhance coherence and reduce grammatical inaccuracies [1].

Participants recognized the strong connection between logical sequence and coherent messaging. By shifting their focus from writing for themselves to writing for an audience, students demonstrated positive effects on their vocabulary, mechanics, layout, and style. For example, in WS#2-Writing an Introduction, students wrote clear and factual thesis statements that were relevant and connected meaningfully within the entire essay. One student reflected on the importance of introductions: “Learning what an introduction is and the parts it should have helped me to understand how to organize an introduction to facilitate comprehension for the readers.”

Similarly, students developed explicit connections between all parts of their essays. Another student highlighted the significance of the thesis statement: “Some sentences that you should include in your introduction to increase understanding, such as the thesis statement, because it organizes introductions better and presents the essay’s main idea you want to develop.” These results demonstrate that students could achieve beyond their initial capabilities with the support of assistance, imitation, and collaboration, which fostered a questioning attitude and critical mindset.

5.4.5. Confidence in Writing Essays

The study sought to increase students’ confidence in writing academic papers. Lack of confidence was a prevalent issue among participants. However, the study showed a significant increase in confidence levels among the 10th graders, as evidenced by comments like “The examples that Teacher John Jaramillo brought into class so I could identify things and write them down better by getting an idea improving my own confidence in writing.”

The collaborative environment and open framework of WWIM created an optimal teaching–learning environment for participants to build confidence. Confidence levels rose significantly as students engaged with both WWIM and AI tools. Collaborative peer reviews and AI-generated feedback helped demystify complex writing tasks, making them more accessible. Students appreciated this dual approach for fostering a supportive learning environment.

Another student noted: “I learned to summarize my ideas in my conclusion during the collaborative stage at the end and how each idea has to be a paragraph in the essay too. It helped me learn how to keep everything well organized rather than mixed or messy and hard to read.”

5.4.6. Challenges in Mastering Some Writing Processes

While WWIM is a demanding and innovative pedagogical methodology, it is not widely applied in the Colombian learning context. Some students exhibited significant cognitive deficiencies in reviewing, drafting/editing, and revision (metacognitive processes), despite their high grade level. Despite their advantages, over-reliance on AI tools risks diminishing critical thinking. Ethical concerns like authorship disputes and plagiarism detection must be addressed to ensure balanced use. Effective training on AI capabilities and limitations is essential.

However, after participating in the intervention, students adapted to and enjoyed the workshop model, engaging in activities and practices that helped them become skilled writers. Many students commented that sharing their writing outcomes made them feel like “real writers” [45].

Students also found that attending a writing class was highly productive and meaningful. Haas [45] describes that such a learning environment aims to empower students to take charge of their writing. Some students expressed their opinions on taking charge of their writing: “I believe that all these writing workshops are very important to learn since when we write a letter or essay, we must take into account the edition part, then the revision and finally, adding citations and with this avoid plagiarism. The work that we made, let me understand better about the writing.”

Additionally, students demonstrated improvements in layout, indenting, and mechanics. These results align with the evaluation data, which showed an average score of 5.8, a standard deviation of 0.27, and successful completion of the subject by all participants. The effective use of mini lessons and planning/editing/revising stage sessions during the independent writing stage likely contributed to the increased confidence levels. Students appreciated the teacher’s feedback and monitoring of group progress.

5.4.7. Addressing Deficiencies in Cognitive Writing Skills

Prior to the intervention of this study, several cognitive deficiencies were observed related to their abilities to offer suggestions, predictions, or recommendations. These initial difficulties were identified in articulating personal viewpoints and constructing well-founded arguments based on prompts. After the workshop, students learned how to apply higher-thinking skills such as making predictions, suggesting results or consequences, proposing solutions, and quoting authorities, making a shift toward more advanced cognitive engagement.

Some students reflected on the significance of providing an opinion or creating a solid argument: “I think I learned the way of how to write a conclusion, the parts and the importance of writing a good personal opinion. How is the perfect way to structure a conclusion”. As such, students perceived the importance of structure and the utility of formulaic expressions such as “in my opinion” and “this essay discussed”, and finally “I consider it’s really similar to the introduction and very useful”. According to their views, students appreciated the useful tips for improving their writing and acknowledged the similarities between the introduction and the conclusion.

Despite these initial cognitive writing deficiencies, students adapted well to the innovative pedagogical approach. The most prominent outcome of the study was that students demonstrated significant improvements in their academic writing skills. These improvements were seen in several areas such as content, organization, confidence, and awareness of cohesion and coherence. Similarly, these results underline how well the teaching approach fosters crucial academic writing abilities.

6. Discussion

This study demonstrates the positive impact of integrating AI-powered tools such as Grammarly, ChatGPT, and Turnitin within the Writing Workshop Instructional Model (WWIM) on the academic writing proficiency of 10th grade ESL students. The hybrid approach of blending WWIM’s structured, collaborative pedagogy with the real-time feedback and automation capabilities of AI tools resulted in notable improvements in students’ fluency, confidence, and ability to refine their writing through iterative processes. Peer discussion activities, combined with AI-generated feedback, enhanced the depth and coherence of students’ written work, fostering a more engaging and effective learning environment.

The findings are consistent with recent research on the formative use of AI tools in ESL/EFL academic writing. Mahapatra [21] demonstrated that ChatGPT, when integrated into instructional routines with feedback cycles, significantly improved learners’ grammar, organization, and coherence in argumentative essays. Similarly, Woo et al. [24] found that secondary EFL students developed recursive editing behaviors when guided to use AI-generated suggestions as part of a structured revision process. Our study aligns with these results by showing how Grammarly and ChatGPT—used within the WWIM framework—enabled students to engage in self-regulated writing, iteratively refining their texts across multiple drafts.

In addition, Yoon et al. [23] caution that while ChatGPT feedback can enhance surface-level cohesion, it often lacks the depth needed to foster critical reflection, unless mediated by teachers. This insight reinforces our approach: rather than allowing students to rely solely on AI output, we embedded peer-sharing and teacher-led metacognitive prompts into each workshop. As a result, students moved beyond mere corrections toward deeper awareness of rhetorical structure and writing purpose, key competencies in ESL academic literacy.

6.1. Enhanced Feedback Mechanisms

The integration of AI tools significantly amplified the feedback mechanisms within WWIM by addressing both mechanical and conceptual aspects of writing. Students benefited from immediate corrections on spelling, grammar, and punctuation, which, coupled with peer reviews, enhanced their ability to produce cohesive and coherent essays. The workshops also demonstrated marked improvements in content organization and reduced mechanical errors, underlining the potential of AI to complement traditional feedback methods.

6.2. Improved Accessibility

AI democratized writing support, particularly for ESL learners facing linguistic barriers. Tools like Grammarly and ChatGPT provided consistent, equitable feedback that scaffolded learning effectively, especially during mini-lessons and revision stages. By working on self-selected topics, students were motivated to engage more deeply with the writing process, reflecting significant growth in their ability to edit and refine their work.

6.3. Ethical Writing Practices

The structured integration of AI into the workshops promoted ethical writing practices, addressing potential risks like over-reliance and plagiarism. Turnitin’s advanced detection capabilities and guided use of AI tools ensured integrity while fostering originality. This dual role of AI as both a facilitator and a safeguard underscores the need for balanced strategies that integrate ethical guidelines with technological advancements. In addition, the inclusion of AI as a tool for assisted writing further empowers students and critically engages them with AI-assisted writing tools, mitigates inappropriate academic behavior, and fosters metacognitive awareness and student authorship. Ultimately, AI-assisted writing is becoming a space in which the ethical use of technology becomes an essential component of teaching in this area, in line with both academic integrity standards and 21st century competencies.

6.4. Scaffolded Learning

The combination of WWIM and AI effectively scaffolded high-order skills such as critical thinking and argumentation. By introducing students to iterative writing and fostering self-regulated learning, the model prepared them for academic and professional writing demands. Hyland’s [46] assertion that writing is central to modern academic and corporate life is evident in the applicability of these skills across contexts.

7. Conclusions

This study presented that integrating AI-powered tools—specifically Grammarly and ChatGPT—into the Writing Workshop Instructional Model (WWIM) can significantly enhance the academic writing skills of 10th grade ESL learners in a bilingual secondary education context. The intervention led to notable improvements in grammar accuracy, textual coherence, and organizational clarity. Additionally, students showed increased engagement with the revision process, as they actively incorporated automated feedback into successive drafts. These findings suggest that the pedagogical synergy between structured writing instruction and real-time AI support not only improves writing performance but also fosters greater writing confidence and autonomy. The results underscore the value of ethically guided AI integration within established instructional models and offer promising avenues for advancing academic writing instruction in secondary ESL education.

7.1. Practical Implications for ESL Instructions

The results of this study suggest several important implications for ESL instructors, curriculum developers, and educational institutions seeking to integrate AI-powered tools into writing instruction. First, the use of tools such as ChatGPT and Grammarly should be framed within structured instructional models that promote recursive writing, peer interaction, and teacher-guided reflection. Our findings show that when AI-generated feedback is coupled with pedagogical mediation, students are more likely to develop metacognitive awareness and a clearer understanding of academic writing conventions.

Second, the integration of AI tools should not replace teacher feedback but rather complement it. Educators play a crucial role in helping students critically evaluate the relevance and reliability of automated suggestions. This demands that teachers receive adequate training on the affordances and limitations of AI technologies, particularly in relation to language accuracy, content coherence, and ethical use.

Third, curriculum designers should consider incorporating AI literacy as a component of writing instruction, especially in ESL contexts. Familiarity with the use and critique of AI-generated feedback can empower learners to become more autonomous and strategic in their writing processes. For policymakers, these findings underscore the need for updated guidelines that support the responsible inclusion of generative AI in language curricula while protecting student data and promoting equitable access.

7.2. Limitations and Future Directions

While this study highlights the pedagogical benefits of integrating AI tools with WWIM, certain limitations necessitate further exploration. The short-term scope of the intervention limits the ability to assess the sustained impact of this hybrid approach. Longitudinal studies are essential to evaluate how the model influences writing proficiency over extended periods and across different educational settings.

Additionally, the study relied heavily on AI tools for feedback, raising concerns about over-reliance, which could inhibit the development of students’ independent critical thinking skills. Future research should focus on strategies to balance AI assistance with teacher-led instruction, ensuring that students remain active participants in their learning process rather than passive recipients of automated corrections.

Cultural and linguistic considerations also merit further investigation. Writing conventions and expectations differ across educational contexts and adapting WWIM and AI tools to align with diverse cultural and linguistic norms is critical. For instance, tools like Grammarly may not fully accommodate the nuanced needs of ESL learners in non-English-speaking countries.

Finally, ethical challenges associated with AI use must be addressed systematically. The potential for misuse, coupled with issues like false positives in plagiarism detection and privacy concerns, calls for the development of robust ethical guidelines. Schools should implement structured training programs to ensure that students and educators understand the capabilities and limitations of AI, promoting responsible and informed usage. By addressing these limitations and exploring new dimensions of the WWIM-AI integration, future research can help refine this hybrid model, maximizing its effectiveness in diverse learning environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.J.J. and A.C.; Methodology, J.J.J.; Supervision, A.C.; Writing—original draft, J.J.J., A.C. and F.S.D.; Writing—review and editing, J.J.J., A.C. and F.S.D. All authors will be updated at each stage of manuscript processing, including submission, revision, and revision reminder, via emails from our system or the assigned Assistant Editor. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available on request from authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Universidad de La Sabana (Technologies for Academia-Proventus Research Group (EDUPHD-20-2022 Project)), for the support received for the preparation of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Khan, A.; Ghani, M. Impact of Artificial Intelligence Writing Tools on the Academic Writing Skills of ESL Learners: A Study Conducted at Graduate Level in Pakistan. Pak. J. Soc. Educ. Lang. (PJSEL) 2024, 10, 228–233. [Google Scholar]

- Fleck, L.J. Growing Writers: How Use of the Writing Workshop Model Strengthens Students’ Perceptions of Themselves as Writers. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.-W.; Li, Z.; Taylor, L. The Effectiveness of Using Grammarly to Improve Students’ Writing Skills. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Distance Education and Learning, Beijing, China, 22–25 May 2020; ACM: Beijing, China, 2020; pp. 122–127. [Google Scholar]

- Shakeel, A. The Role of ChatGPT in Academic Writing: An Exploratory Study. Master’s Thesis, Oslo Metropolitan University, Oslo, Norway, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Subedi, R.; Nyamasvisva, T.E. A Review of the Influence of Artificial Intelligence in Academic Writing. J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Technol. 2024, 2, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountas, I.C.; Pinnell, G.S. Guiding Readers and Writers, Grades 3-6: Teaching Comprehension, Genre, and Content Literacy; Heinemann: Hamburg, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Uccelli, P. The Language Demands of Analytical Reading and Writing at School. Writ. Commun. 2023, 40, 518–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Yu, S.; Liu, C.; Jiang, L. Mapping Research on Second Language Writing Teachers: A Review on Teacher Cognition, Practices, and Expertise. System 2022, 109, 102870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Peze, A.; Janssen, T.; Rijlaarsdam, G.; Van Weijen, D. Writing Creative and Argumentative Texts: What’s the Difference? Exploring How Task Type Affects Students’ Writing Behaviour and Performance. L1 Educ. Stud. Lang. Lit. 2021, 21, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimova, B.F. Constraints and Difficulties in the Process of Writing Acquisition. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 122, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starfield, S.; Hafner, C.A. The Handbook of English for Specific Purposes; John Wiley & Sons: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Escalante, J.; Pack, A.; Barrett, A. AI-Generated Feedback on Writing: Insights into Efficacy and ENL Student Preference. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High Educ. 2023, 20, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzuki; Widiati, U.; Rusdin, D.; Darwin; Indrawati, I. The Impact of AI Writing Tools on the Content and Organization of Students’ Writing: EFL Teachers’ Perspective. Cogent Educ. 2023, 10, 2236469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strassman, B.K. Differentiated Instruction in the English Classroom: Content, Process, Product and Assessment. J. Adolesc. Adult Lit. 2004, 48, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, A.S.M. The Transformative Impact of AI-Powered Tools on Academic Writing: Perspectives of EFL University Students. Int. J. Engl. Linguist. 2024, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.R.; Graham, S.; Aitken, A.A.; Barkel, A.; Houston, J.; Ray, A. Teaching Spelling, Writing, and Reading for Writing: Powerful Evidence-Based Practices. Teach. Except. Child. 2017, 49, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgarejo, D.A. Assessing Children’s Perceptions of Writing in EFL Based on the Process Approach. Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J. 2010, 12, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pastini, N.W.; Lilasari, L.N.T. Empowering EFL Students: A Review of Student-Centred Learning Effectiveness and Impact. J. Appl. Stud. Lang. 2023, 7, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troia, G.A.; Lin, S.C.; Monroe, B.W.; Cohen, S. The Effects of Writing Workshop Instruction on the Performance and Motivation of Good and Poor Writers. Instr. Assess. Struggl. Writ. Evid.-Based Pract. 2009, 18, 77–112. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hroub, A.; Shami, G.; Evans, M. The Impact of the ‘Writers’ Workshop’ Approach on the L2 English Writing of Upper-Primary Students in Lebanon. Lang. Learn. J. 2019, 47, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, S. Impact of ChatGPT on ESL Students’ Academic Writing Skills: A Mixed Methods Intervention Study. Smart Learn. Environ. 2024, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abduljawad, S.A. Investigating the Impact of ChatGPT as an AI Tool on ESL Writing: Prospects and Challenges in Saudi Arabian Higher Education. Int. J. Comput.-Assist. Lang. Learn. Teach. 2025, 14, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.-Y.; Miszoglad, E.; Pierce, L.R. Evaluation of ChatGPT Feedback on ELL Writers’ Coherence and Cohesion. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.06505. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, D.J.; Yu, Y.; Guo, K. Exploring EFL Secondary Students’ AI-Generated Text Editing While Composition Writing. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.17041. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, C.-Y.; Lin, Y.-T.; Brown, I.K. Impacts of ChatGPT-Assisted Writing for EFL English Majors: Feasibility and Challenges. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 22427–22445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagini, G. Towards an AI-Literate Future: A Systematic Literature Review Exploring Education, Ethics, and Applications. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, L. A Review of Creative Writing Workshop Pedagogy in Educational Research: Methodological Challenges and Affordances. J. Poet. Ther. 2016, 29, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarbrough, B.; Allen, A.-R. Writing Workshop Revisited: Confronting Communicative Dilemmas Through Spoken Word Poetry in a High School English Classroom. J. Lit. Res. 2014, 46, 475–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.; Ong, E.T.; Muhamad, M.M.; Massa Singh, T.S.; Zaini, F.A.; Gopal, R.; Maniam, M. Teachers’ Self-Assessment of and Perceptions on Higher-Order Thinking Skills Practices for Teaching Writing. Pegegog 2023, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez Vivar, J.A.; Betancourt Sevilla, G.J.; Montaño Salazar, I.K.; Zapata, S.N. La Enseñanza de La Gramática y La Ortografía En La Educación Secundaria: Un Análisis de Las Prácticas Docentes: The Teaching of Grammar and Spelling in Secondary Education: An Analysis of Teaching Practices. Rev. Cient. Multi. G-Nerando 2025, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Language Education in Multilingual Colombia: Critical Perspectives and Voices from the Field; Miranda, N., de Mejía, A.-M., Valencia Giraldo, S., Eds.; Routledge critical studies in multilingualism; Routledge:: New York, NY, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-0-367-72549-5. [Google Scholar]

- Banegas, D.L.; Arellano, R. Teacher Language Awareness in CLIL Teacher Education in Argentina, Colombia, and Ecuador: A Multiple Case Study. Lang. Aware. 2024, 33, 707–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robayo Luna, A.M.; Hernandez Ortiz, L.S. Collaborative Writing to Enhance Academic Writing Development through Project Work. HOW 2013, 20, 130–148. [Google Scholar]

- Bitchener, J.; Young, S.; Cameron, D. The Effect of Different Types of Corrective Feedback on ESL Student Writing. J. Second Lang. Writ. 2005, 14, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickens, L.; Watkins, K. Action Research: Rethinking Lewin. Manag. Learn. 1999, 30, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshima, A.; Hogue, A. Writing Academic English; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Fan, J. Assessing Business English Writing: The Development and Validation of a Proficiency Scale. Assess. Writ. 2020, 46, 100490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, K.; Xu, S. Designing Language Courses: A Guide for Teachers. Electron. J. Engl. A Second Lang. 2000, 4, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, E.C. Writing and Reading in a First-Grade Writers’ Workshop: A Parent’s Perspective. Read. Teach. 1994, 47, 372–377. [Google Scholar]

- Honeycutt, R.L. Good Readers/Poor Writers: An Investigation of the Strategies, Understanding, and Meaning That Good Readers Who Are Poor Writers Ascribe to Writing Narrative Text on-Demand; North Carolina State University: Raleigh, NC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dorn, L.; Soffos, C. Scaffolding Young Writers: A Writer’s Workshop Approach, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023; ISBN 978-1-032-68233-4. [Google Scholar]

- Cer, E. The Instruction of Writing Strategies: The Effect of the Metacognitive Strategy on the Writing Skills of Pupils in Secondary Education. Sage Open 2019, 9, 2158244019842681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dergaa, I.; Chamari, K.; Zmijewski, P.; Ben Saad, H. From Human Writing to Artificial Intelligence Generated Text: Examining the Prospects and Potential Threats of ChatGPT in Academic Writing. Biol. Sport 2023, 40, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, K. English for Professional Academic Purposes: Writing for Scholarly Publication. In Teaching Language Purposefully: English for Specific Purposes in Theory and Practice; Belcher, D., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Haas, S.S. Some Kind of Writer: The Writer Spectrum, and a (Not-Magic) Formula for Skill Development. In Palgrave Studies in Gender and Education; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 67–96. ISBN 978-3-031-44976-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hyland, K. ESP and Writing. In The Handbook of English for Specific Purposes; Starfield, S., Hafner, C.A., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 89–106. ISBN 978-1-119-98500-6. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).