Featured Application

The fuzzy logic-based tool proposed in this paper can support supply chain managers in evaluating the implementation level of Lean, Agile, Resilient, and Green practices across different operational areas. Thanks to its software-based design, the tool is easily applicable in real-world industrial contexts to identify targeted improvement opportunities.

Abstract

This study proposes a fuzzy logic-based approach to better manage supply chain uncertainty and improve decision-making flexibility. The developed framework categorizes supply chain activities into procurement, production, distribution and reverse logistics and integrates Lean, Agile, Resilient, and Green (LARG) KPIs within a hierarchical structure. The tool was implemented using Microsoft ExcelTM to enhance usability for practitioners. To test its applicability, the model was applied to a real case study. The results show that lean and resilient practices are consistently well-established across all supply chain phases, while agility and green practices vary significantly depending on the operational area—particularly between internal function (i.e., production and reverse logistics) and external ones (i.e., procurement and distribution). These findings help to better understand how the LARG capabilities are distributed across the different operational areas of the supply chain and offer practical guidance for managers seeking targeted performance improvement. Although the numerical results are context-specific, the framework’s adaptability makes it suitable for diverse supply chain environments.

1. Introduction

Today’s competitive environment is characterized by constantly increasing variability and unpredictability. In addition to the typical phenomena that have influenced markets in recent decades, such as globalization, price volatility, competitiveness, network complexity, and demand customization [1], recent disruptive events have further challenged supply chains (SCs) worldwide. The unpredictability of such disruptions, as demonstrated by the COVID-19 pandemic, can lead to poor decision-making, potentially resulting in severe economic shocks [2]. In this context, good supply chain management (SCM) is of paramount importance and becomes a strategic factor in achieving efficiency and effectiveness in all processes.

To combine the different characteristics of SCs associated with the need to be increasingly efficient, Azevedo et al. [3] have introduced the LARG (lean, agile, resilient, and green) paradigm, which effectively merges various SC perspectives. The lean paradigm, originally developed by [4] as part of the Toyota Production System (TPS), grounds on two main principles: autonomy and just-in-time (JIT) production. Its primary focus lies in waste reduction to increase actual value added, meeting customer needs while maintaining profitability [5]. Lean principles have been extended beyond manufacturing to encompass the entire supply chain, including distribution, where minimizing waste means delivering the right product to the right place at the right time [6]. Key lean supply chain practices involve eliminating non-value-adding activities, integrating upstream and downstream processes, and enhancing production flexibility and efficiency [7]. However, challenges arise in balancing production smoothing techniques, such as kanban, with the need to respond to variable market demand [6]. Lean also emphasizes respect for people, quality management, pull production, and mistake-proofing, employing operational techniques like 5S, takt-time, and SMED to systematically reduce waste and optimize processes [8].

The agile supply chain paradigm focuses on delivering the right product, in the right quantity and condition, at the right place and time, and at the right cost, while being highly adaptable to continuously changing customer’s requirements. Agile supply chains are designed to respond rapidly and cost-effectively to unpredictable market changes and increasing environmental turbulence, both in terms of volume and variety [9,10]. According to [11], “an agile SC is an integration of business partners to enable new competencies in order to respond to rapidly changing, continually fragmenting markets”. Key variables influencing the deployment of the agile paradigm include market sensitivity, customer satisfaction, quality improvement, delivery speed, collaborative planning, process integration, use of IT tools, lead-time reduction, cost minimization, and trust development [9]. Agile practices encompass frequent new product introductions, improved customer service responsiveness, centralized and collaborative planning, IT-enabled coordination of manufacturing activities, and flexible production and delivery schedules [9,12,13].

Resilience refers to the ability of a SC to cope with unexpected disturbances, aiming to prevent shifts to undesirable states where failure modes may occur. The resilient paradigm has two main goals: (i) to recover a desired system state after a disturbance within acceptable time and cost; and (ii) to reduce the impact of disturbances by mitigating potential threats [14]. Recovery capabilities rely on responsiveness, flexibility, and redundancy [15]. Ref. [16] consider robustness a subset of resilience, emphasizing a system’s return to its original state post-disturbance. Ref. [17] proposes robust SC practices to efficiently deploy contingency plans, including postponement, strategic stock, flexible supply base, make-or-buy trade-offs, flexible transportation, and dynamic assortment planning. Ref. [18] suggest resilience design principles such as maintaining multiple strategic options, balancing efficiency and redundancy, fostering collaboration across SC partners, enhancing visibility into inventories and demand, and improving SC velocity through streamlined processes. Key resilience practices in SCs include strategic stockpiling, lead time reduction, maintaining dedicated transit fleets, flexible sourcing, and demand-based management [15,17,18,19].

The green supply chain improves the environment, economic performance, and competitiveness [20] and provides opportunities to reduce waste and consume resources effectively and efficiently [21,22]. In this context, the goal is therefore to minimize the ecological impact and the environmental risks of resources within the supply chain [23]. Activities that can typically be adapted to a green SC range from green purchasing to mapping the sustainable value stream, as well as eliminating packaging and implementing recycling initiatives [24,25].

For proper implementation of the LARG concept, it is essential to measure the SC capabilities and performance along these four dimensions. This can be accomplished through the development of appropriate measurement systems, allowing decision makers to effectively monitor all key performance indicators (KPIs) relevant to SCM over a given period of time, providing an overall assessment of performance according to LARG principles [26].

However, evaluating the performance of a supply chain according to the perspectives of the LARG paradigm can be complex due to the multiplicity of factors involved, which are often heterogeneous, interdependent and difficult to quantify [27]. In this context, Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) models prove to be particularly effective tools for managing the uncertainty and complexity inherent in supply chain-related strategic decision-making processes [28]. Techniques such as the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), fuzzy logic, the Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS), and the Decision-Making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory (DEMATEL) [29], allow complex problems to be structured in a hierarchical manner, integrating both quantitative and qualitative data and taking into account the subjective judgement of experts.

In particular, the AHP distinguishes because of its ability to decompose a problem into a hierarchical structure that facilitates the comparison of criteria and alternatives through pairwise evaluations, yielding a scale of priorities useful for guiding choices [30]. When such judgements are affected by uncertainty or ambiguity, the fuzzy extension of AHP allows for a more realistic representation of decision preferences, using fuzzy numbers to model uncertainty in the comparisons made by experts [31]. Indeed, fuzzy systems allow for a more nuanced assessment of variables that are difficult to measure precisely or may fluctuate over time. These include uncertainties such as demand volatility, supply disruptions, variable lead times, resource availability, inventory fluctuations and imprecise supplier performance metrics. These approaches are thus well suited to SC performance evaluation according to LARG principles, supporting the identification of strategic priorities and critical areas for improvement.

Several studies have employed MCDM approaches to structure and support decision-making in LARG environments. For instance, [32] used AHP to examine the influence of LARG practices on supply chain performance, providing a structural interpretation of the interrelations among criteria. Similarly, [33] introduced the LARG index as a benchmarking tool to assess supply chain maturity levels in terms of leanness, agility, resilience and greenness. Their work relied on AHP to determine weights and prioritize indicators, showing how MCDM methods can support strategic supply chain assessment. Other studies, such as those by [34] have applied the AHP to compare LARG strategies in specific industrial sectors (e.g., cement manufacturing) revealing how context-specific criteria can influence priority setting. Likewise, [35] proposed a hybrid AHP-based decision-making model for LARG supplier selection, integrating tools like the house of quality and the Taguchi loss function to reinforce supplier evaluation frameworks. The ambiguity and subjectivity of SC evaluation has brought to the adoption of alternative MCDM approaches, such as fuzzy logic, which can better accommodate linguistic assessments and uncertainty.

In line with this shift, a growing number of studies have employed fuzzy logic to evaluate LARG supply chain performance. Ref. [36] introduced a SCOR-based fuzzy MCDM framework to assess SC performance under LARG principles. Their model, applied to the automotive sector, demonstrated how a fuzzy evaluation could better capture the dynamic interplay between lean, agility, resilient and green criteria, especially when data uncertainty or subjectivity is present. Similarly, Refs. [37,38] have proposed a hybrid decision-making model combining fuzzy logic with MCDM tool for supplier selection. By integrating lean, agile, resilience and green factors into a fuzzy evaluation structure, the study showcased the method’s flexibility in supporting complex procurement decisions under uncertainty. Ref. [39] focused on assessing interoperability in LARG chains through a fuzzy-based model. Their contribution emphasized the role of fuzzy tools in evaluating collaborative capacity and structural integration across the different LARG paradigms. Ref. [40] explored the implementation of LARG strategies in line with Industry 4.0 principles, using fuzzy logic to assess operational improvements. Recently, ref. [29] proposed a fuzzy hybrid approach to identify the most relevant LARG criteria for supplier selection and evaluate the relationships between them in a decision-making process.

From these contributions it can be argued that the application of AHP in the context of LARG supply chains remains largely confined to initial conceptual models or narrowly focused sector-specific studies. On the other hand, while existing studies based on fuzzy logic consistently support its suitability for LARG-oriented evaluations, they often lack a unified structure that simultaneously integrates all four LARG dimensions across the entire supply chain, encompassing procurement, production, distribution, and reverse logistics. Furthermore, many of these contributions are conceptual in nature or focus on isolated decision-making problems, such as supplier selection or process interoperability, failing to offer a comprehensive and operational framework.

In recent years, the evolution of digital technologies has significantly reshaped the way SCs are designed, managed, and evaluated. Technological tools have enhanced the capabilities of SC managers, enabling real-time monitoring, predictive insights, and faster responses to disruptions. These advancements are particularly relevant within the LARG paradigm, as they provide valuable support for achieving lean operations, improving agility, fostering resilience, and ensuring environmental sustainability [41].

The integration of digital solutions also facilitates the implementation of decision-support systems based on MCDM techniques, allowing companies to move from theoretical frameworks to practical, user-friendly tools. In this context, the digitalization of evaluation methods, through platforms such as ExcelTM or customized applications, emerges as a key enabler of effective decision-making in real-world business environments.

Against this backdrop, there is a growing consensus that SC performance evaluation must evolve to accommodate the complexity, dynamism, and multidimensional nature of modern systems. This calls for integrated, flexible, and data-informed frameworks that can guide organizations toward more balanced and robust decision-making processes.

This study moves from previous research activities (i.e., [42]), in which a preliminary framework based on the AHP was delineated for the evaluation of the SC through the LARG perspectives. In that paper, the authors have highlighted the need for implementing alternative decision models, in addition to the AHP one, and analyzing the different results returned. That study also introduced a hierarchical structure dividing supply chain processes into four operational categories: procurement, production, distribution, and reverse logistics. In addition, the same study has suggested that computerization of the tool by app or technological instruments could enhance the applicability of the methods by companies.

The present study aims to fill these gaps by:

- Developing an alternative framework, based on fuzzy logic, for the evaluation of LARG chains focusing on the four operational categories: procurement, production, distribution and reverse logistics.

- Implementing the fuzzy logic-based tool in ExcelTM software, to automate the computational procedure.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 outlines the research methodology. Section 3 presents the results, followed by a discussion in Section 4. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper, summarizing key findings, discussing implications and suggesting future research directions.

2. Methodology

The aim of this study is to develop a fuzzy logic-based framework, describing all the necessary steps, and an integrated and quantitative tool for the evaluation of SCs through the usage and integration of LARG paradigm, implemented with ExcelTM software package.

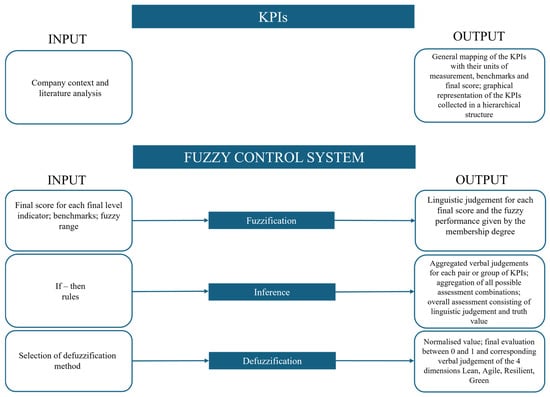

Figure 1 summarizes the main steps to be followed to develop the fuzzy logic-based framework and implement the tool in ExcelTM.

Figure 1.

Methodological framework.

To facilitate its practical implementation, the following step-by-step process summarizes how the framework is implemented in Excel™, in alignment with the phases illustrated in Figure 1 and described in the following paragraphs:

- Data collection: Gather company-specific values for all selected KPIs, as listed in Table 1, and define the corresponding benchmark values.

Table 1. List of KPIs from the LARG-related studies.

Table 1. List of KPIs from the LARG-related studies. - KPI scoring: Calculate the normalized score for each KPI, based on the company value and benchmark.

- Fuzzification: Convert the normalized KPI scores into linguistic terms (Very Low, Low, High, Very High) using trapezoidal membership functions.

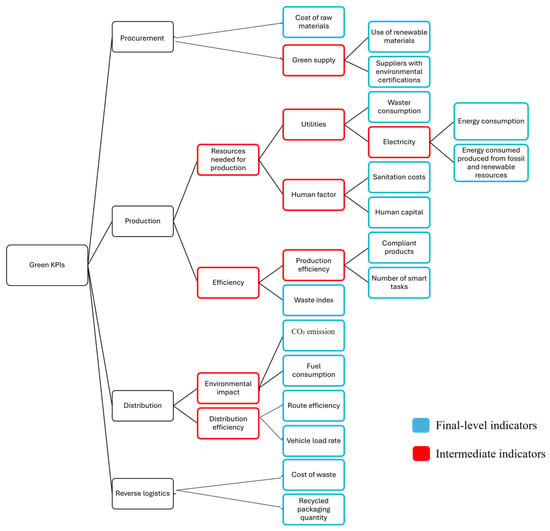

- Hierarchical aggregation: Combine KPIs progressively according to the structure in Figure 2, using fuzzy if–then inference rules to obtain intermediate and final evaluations.

Figure 2. Example of a hierarchical aggregation structure for KPIs within the green dimension, used in the fuzzy logic framework.

Figure 2. Example of a hierarchical aggregation structure for KPIs within the green dimension, used in the fuzzy logic framework. - Truth value calculation: Determine the degree of truth for each rule-based output, reflecting the contribution of each KPI.

- Defuzzification and normalization: Aggregate the fuzzy outputs into a crisp score using the fuzzy mean method and normalization.

- Performance interpretation: Use the final values to interpret performance across the LARG dimensions and SC areas, identifying areas requiring improvement.

2.1. KPIs Definition

The first step in developing the fuzzy logic-based framework is the identification and definition of the relevant KPIs. These latter are carefully selected from the literature, focusing on the LARG paradigm, which serves as the basis for evaluating the supply chain. A total of 21 relevant studies were systematically reviewed to ensure a robust and comprehensive selection of indicators. The full list of references is provided in the additional material, available on the Mendeley Data repository at DOI: 10.17632/typfbkk3m8.1 [43]. Table 1 shows the KPIs with their description.

To ensure relevance and applicability in practice, the selected KPIs are to be aligned with the company’s specific performance metrics, which will be used to calculate the company’s values for each indicator.

The first output of this step is a general mapping of the KPIs along with their units of measurement and benchmark values, which helps compare the company’s performance against industry standards, best practices, or general (e.g., regulatory) benchmarks. In addition, the final score for each KPI is calculated in accordance with (1):

The second output of the first step is a graphical representation of the KPIs within a hierarchical structure, reflecting the relationships between individual indicators and their respective categories (procurement, production, distribution and reverse logistics) and subcategories.

2.2. Fuzzy Control System

The objective of fuzzy logic control (FLC) system is to control complex processes by means of human experience [44]. Indeed, it plays an important role when applied to complex phenomena that are not easily described by traditional mathematics [45]. In fuzzy set theory, trapezoidal fuzzy numbers are characterized by membership functions that increase monotonically from zero to one, remain constant, and then decrease monotonically back to zero, thus effectively modeling uncertainty with a clear structure. This monotonic behavior in the membership function is particularly useful in various engineering and decision-making applications, as it allows for a structured representation of uncertainty [46].

2.2.1. Fuzzification

In this phase, the input consists of the final scores calculated for each KPI, while the output includes both the corresponding linguistic evaluations and their fuzzy membership degrees.

To get a linguistic evaluation, each final score is mapped onto a four-point linguistic scale based on the model proposed by [47]. The linguistic terms used are: Very Low, Low, High, and Very High.

In this study, as in many other studies [48,49], trapezoidal functions are adopted to model the fuzzy numbers. The mathematical definition of a trapezoidal fuzzy number is expressed through membership function (2):

where:

- x represents the numerical value of the variable (i.e., the final score against the selected KPI);

- µ(x) is the corresponding membership degree;

- a, b, c, and d are the parameters that define the shape of the trapezoidal fuzzy number, based on decision-makers’ judgment or benchmark tables.

As a result, this phase provides two outputs: the linguistic evaluation and the corresponding membership degree for each KPI.

2.2.2. Inference

The inference process is applied when indicators need to be aggregated, based on the hierarchical diagram previously described. This process relies on if-then rules to evaluate and combine the fuzzy sets of two or more indicators. In this case, aggregation is carried out between two indicators, as the hierarchical structure was designed to simplify calculations, although the method can be extended to more indicators if necessary.

The if-then rules used in the inference process are derived from semantic aggregation matrix based on linguistic combinations of input variables. They reflect expert knowledge since both the linguistic input values and the aggregation logic were developed in consultation with domain experts. This ensures that the inference process aligns with practical and contextual understanding.

The inference is based on a fuzzy rule matrix, such as the one shown in Table 2, where the fuzzy linguistic variables (e.g., Very low, Low, Average, High, Very high) are combined according to pre-defined rules. Each combination of input values from the two indicators results in an aggregated fuzzy value, which corresponds to the output linguistic value.

Table 2.

Fuzzy inference rule matrix used to determine the output linguistic values.

In this matrix, the rows and columns represent the linguistic values of the two indicators being aggregated, and the intersection of each row and column gives the resulting output linguistic value.

In certain cases, it is appropriate to introduce a middle or neutral judgment (labeled as “Average”) during the aggregation process. This judgment is particularly useful in situations where the performance of the company with respect to two indicators is conflicting or shows intermediate levels of performance. The “Average” judgment helps better represent situations in which neither indicator significantly dominates the other, allowing for a more balanced assessment. This neutral value will be especially important for subsequent aggregations, where the results from multiple indicators are combined and evaluated.

The final output of the inference is the “truth value” of each indicator (Equation (3)).

In the formula above:

i: total number of KPIs considered

μj(xj): membership degree of the j-th KPI

2.2.3. Defuzzification

The final step of the fuzzy control system involves defuzzification, a process in which the fuzzy output, known as the fuzzy set, is transformed into a crisp value. This step is essential in fuzzy logic systems to convert the qualitative results derived from inference rules into a usable, quantitative output. Therefore, the values obtained through defuzzification represent numerical equivalents of linguistic expressions that contain the system’s final assessment.

In general, this phase involves two key steps:

- (i)

- selecting the defuzzification method;

- (ii)

- normalizing the final score.

With respect to the first step, several defuzzification methods exist in the literature. Among them, the fuzzy mean (FM) method, highlighted by [50], is one of the most applied due to its simplicity and effectiveness. The FM method makes use of the following formula (Equation (4)):

where:

- n is the number of fuzzy conclusions;

- ak is the truth value (i.e., degree of membership) of the k-th conclusion obtained from the inference phase;

- Xk is the numeric value associated with the k-th conclusion. For trapezoidal fuzzy numbers, this is typically the average of the two values where the membership function reaches its maximum. Table 3 shows the fuzzy interval used to determine the Xk value.

Table 3. Fuzzy ranges.

Table 3. Fuzzy ranges.

However, it is important to note that the crisp value and its range depend on the type of fuzzy numbers and linguistic scales adopted. Therefore, as a second step, a final normalization is required to express the output within a standardized range (typically between 0 and 1, with higher values indicating better performance). This is done using the following normalization formula (Equation (5)):

where:

- x is the crisp sustainability index before normalization;

- min and max are the minimum and maximum values in the possible range of variation, which correspond to the extreme cases where the company achieves the lowest or highest scores across all indicators.

3. Tool Implementation and Results

To demonstrate the applicability and effectiveness of the proposed fuzzy-based framework, a case study is presented. The tool is applied to a real company scenario in order to evaluate its supply chain performance across LARG perspective. This approach is consistent with other works in literature that have adopted case studies to test MCDM models in LARG context (e.g., [51,52,53]).

3.1. KPIs Definition

This step includes the “input interface” of the tool, including company’s value, unit of measurement, benchmark and final score, as described in the methodology section. For the sake of brevity, only the green dimension will be presented in this study (Table 4); even if the same methodology is applied for all the four dimensions (Appendix A, Table A1, Table A2 and Table A3).

Table 4.

Company’s value, unit of measurement, benchmark and final score for green KPIs.

Figure 2 and Table 5 show a possible aggregation of the KPIs listed in Table 1 for the green dimension. The hierarchical structure of the remaining three perspectives is shown in Appendix A (Table A4, Table A5 and Table A6). Starting from the outermost part of the diagram, two final-level indicators are aggregated at a time, proceeding progressively inward until reaching the green category. This category represents the overall evaluation, which is derived from the indicators at the preceding levels. The diagram includes two types of indicators: those highlighted in blue represent the final-level indicators used for the assessment, while those highlighted in red are intermediate indicators required for the correct functioning of the tool according to the proposed logic. Although the graph represents the aggregation of two inputs at a time for simplicity, the proposed fuzzy approach is generalizable and can be extended to the aggregation of a larger number of inputs, depending on user requirements. The hierarchical structure used represents a methodological choice to ensure clarity, manageability, and scalability of the system without compromising the multi-criteria validity of the model. Again, this design is consistent with previous studies on fuzzy inference systems, which recommend hierarchical structures for reducing rule explosion and enhancing model interpretability in complex decision-making scenarios (e.g., [56,57]).

Table 5.

Aggregation of green KPIs.

3.2. Fuzzy Control System

3.2.1. Fuzzification

The first step, as described in the methodology, is the identification of linguistic judgment of each KPIs on the basis of their final score value. The fuzzy range of each green KPIs is defined and shown in Table 6. The fuzzy range of the remaining dimensions (lean, agile, resilient) are shown in Appendix B (Table A7, Table A8 and Table A9).

Table 6.

Fuzzy range of green KPIs.

On the basis of the fuzzy range and the final score, the linguistic judgment and the membership degree are defined, as shown in Table 7 and Appendix C (Table A10, Table A11 and Table A12).

Table 7.

Linguistic judgment and membership degree of green KPIs.

3.2.2. Inference

The KPIs are aggregated (see Table A13 in the Appendix D) to derive the final indicators, which include both the red values shown (subcategories) and the four main categories (Procurement, Production, Distribution, and Reverse Logistics), illustrated in Figure 2. Table 8 and Table A14, Table A15 and Table A16 in Appendix D report the inference results, providing the final truth values associated with each of these indicators, for green KPIs and other three dimensions, respectively.

Table 8.

Inference results of green KPIs.

3.2.3. Defuzzification

The goal of the tool is the achievement of a final assessment, broken down by process part, that encompasses the indicators initially selected in the final assessment. For each group of indicators Lean, Agile, Resilient and Green, the final evaluation formed by “linguistic judgment”, “truth value”, “fuzzy mean” and “final linguistic judgment” for Procurement, Production, Distribution and Reverse logistic is obtained (Table 9).

Table 9.

Final evaluation by process part for each indicator group, expressed through linguistic judgment and truth value.

4. Discussion

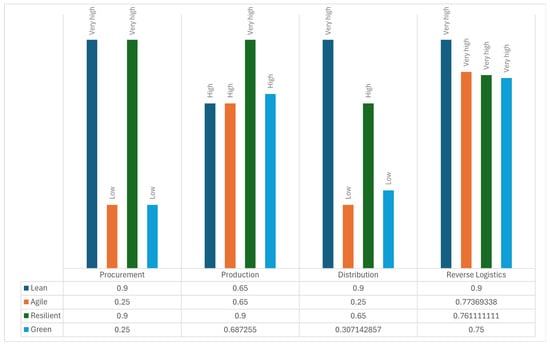

Figure 3 shows the fuzzy mean and the final linguistic judgments for each dimension (lean, agile, resilient and green), divided by indicator (procurement, production, distribution and reverse logistic).

Figure 3.

Final results—fuzzy mean and linguistic judgments of each dimension.

KPIs in the lean dimension show very high performance in any activity: procurement, distribution and reverse logistics have fuzzy mean equal to 0.9, with a linguistic judgment equal to “very high”; while production has a fuzzy mean equal to 0.65 and a linguistic judgment equal to “high”.

The agile perspective shows a very heterogeneous distribution: procurement and distribution show low values (FM = 0.25, ratings “low” linguistic judgment), while Production reaches a FM of 0.65 (“high”) and reverse logistics stands out with a FM of 0.77 (“very high”). As for Resilience, the results are more homogeneous: Procurement and Production reach FM values equal to 0.90 (“very high”), distribution has FM equal to 0.65 (“high”), while Reverse Logistics stands at 0.76 (“very high”).

Finally, the Green dimension highlights high values for production (around 0.68) and reverse logistics (0.75); while procurement and distribution have “low” values, around 0.25 and 0.31 respectively.

4.1. Theoretical Implications

From a theoretical perspective, the model evaluated by the fuzzy approach contributes to the literature on LARG supply chain.

The results highlight several theoretical insights:

- Lean activities emerge as a consolidated operational foundation across all supply chain phases. Consistent with their historical role in ensuring efficiency and standardization.

- Agility, despite being traditionally conceptualized as a transversal capability, appears to be strongly localized in specific operational areas.

- Resilience, recognized as a strategy to optimize and maintain the efficiency of the supply chain activities during disruptions events, proves to be a structural requirement.

- Finally, the data related to the green dimension support the theoretical hypothesis according to which sustainability practices are more easily implemented within business processes, confirming that internal management represents a key factor in the adoption of such practices [58]. On the contrary, the integration of sustainability in supplier relations and in downstream distribution is more complex and presents greater critical issues.

4.2. Managerial Considerations

This study not only signal vulnerabilities but also provides insights that can support managerial decisions in different areas of the supply chain. The LARG framework, assessed through the implementation of the tool, highlights how each dimension (lean, agile, resilient and green) is perceived and implemented in practice, offering indications on where to strengthen and/or improve strategic efforts.

Given the consistently high performance, lean practices appear to be well integrated and standardized. In production, however, where performance is relatively lower, there may be the necessity to strengthen lean initiatives through increased standardization, reduced variability and continuous improvement practices.

The heterogeneous performance of the agile dimension suggests that agility is not uniformly embedded across the supply chain. While agility in reverse logistics and production is strong, its limited presence in procurement and distribution means that the company may not be able to adapt in time when the market changes suddenly or when supply issues arise. Managers should consider investing in digital tools (e.g., real-time monitoring, demand forecasting) and flexible sourcing strategies to improve agility, especially in procurement and distribution.

High performance in procurement and manufacturing highlights that upstream resilience has become a structural priority, likely in response to recent global crises. Managers should maintain this focus by developing strong supplier relationships; at the same time, efforts should be made to extend resilience downstream, particularly in distribution, where the capacity to handle disruptions appears relatively weaker.

The green dimension shows a clear distinction between internal (i.e., production and reverse logistics) and external (i.e., procurement and distribution) operations. Managers should leverage positive results in production and reverse logistics, using these successes as a basis for spreading more sustainable practices through the company. However, low scores in procurement and distribution signal a need for greater involvement of green suppliers and more sustainable solutions, such as sustainability criteria in supplier selection [29] and partnerships with green logistics providers.

Based on these findings, the following managerial considerations can be drawn:

- Maintain lean practices as standardized routines and extend them to production activities, for which the current performance is lower.

- Invest in standardization, value stream mapping and continuous improvement to strengthen lean performance in production.

- Invest in flexible transport options or demand forecasting technologies to enhance agile distribution performance.

- Enhance supply chain responsiveness by adopting flexible procurement policies, improving demand sensing and integrating real-time monitoring tools.

- Develop downstream resilience through improved distribution flexibility, last-mile risk mitigation and crisis response planning.

- Promote green supplier development, introduce sustainability criteria in procurement and partner with green logistics providers to close the internal-external performance gap.

4.3. Practical Implications

This study provides insights for supply chain managers by showing how lean, agile, resilient and green dimensions are perceived and implemented across different operational areas, namely procurement, production, distribution and reverse logistics. The breakdown of results by process allows for a more precise understanding of where strengths and weaknesses lie, support targeted interventions rather than generalized strategies. By relying on objective data rather than assumptions, managers can make more informed decisions, identify strengths and weaknesses, and implement targeted corrective actions. The proposed tool is also highly adaptable and can be applied to any type of company or supply chain context. To ensure its effectiveness, it is essential that the decision-makers or user customizes the assessment by developing specific reference tables for each indicator. These must be based on the user’s knowledge and experience of the company being analyzed, ensuring that the assessment reflects the unique characteristics and strategic priorities of the organization. Moreover, the ExcelTM implementation offers accessibility, transparency and ease use.

5. Conclusions

Moving from a previous study [42] which developed a preliminary AHP-based framework for evaluating supply chains through LARG perspectives and highlighted the need to explore additional decision-making approaches alongside AHP, as well as suggesting that computerizing the tool via apps or technological solutions could enhance its applicability for companies, this study aims to create a fuzzy logic-based framework for LARG supply chain evaluation and implement the tool using ExcelTM.

The developed framework allows to accurately analyze the supply chain performance along its internal (i.e., production and reverse logistics) and external (i.e., procurement and distribution) activities and along the four LARG dimensions, offering a concrete basis for continuous improvement strategies. It provides a solid foundation for identifying inefficiencies, addressing critical issues through targeted interventions, and ultimately enhancing competitiveness, sustainability, and adaptability.

Additionally, the fuzzy logic framework developed in this study is particularly suited for addressing various types of uncertainty commonly encountered in supply chain decision-making. By structuring the evaluation across four operational areas (procurement, production, distribution, and reverse logistics), the model captures specific uncertainty factors tied to each domain. In procurement, it accounts for supplier lead time variability, reliability, and flexibility, which are often unpredictable. In production, the model handles variability in equipment effectiveness, process times, and defect rates, helping mitigate risks tied to capacity constraints or operational disruptions. In distribution, uncertainties in delivery accuracy, load efficiency, and fuel consumption are integrated into the analysis, supporting better logistics planning under fluctuating demand conditions. Finally, in reverse logistics, the model incorporates uncertainties linked to return flow timing, volume, and processing efficiency, which are typically hard to forecast. By translating qualitative and variable data into fuzzy linguistic terms, the model enables a more flexible and realistic evaluation under incomplete or ambiguous information, aligning with the complex and dynamic nature of real-world supply chains.

However, some limitations must be acknowledged. The list of indicators considered in this study is intended to represent a flexible starting point for company-level assessments, but it does not constitute an exhaustive or universally valid framework. It must be adapted and updated according to the specific context in which the tool is applied. Similarly, although the hierarchical structure (Figure 2) illustrates the aggregation of two KPIs for simplicity, the model is fully scalable and can handle a higher number of inputs as needed. Due to the high variability among companies, in terms of industry, market and organizational structure, it is not possible to define general fuzzification scales. These scales must be customized each time the tool is applied to a new company or each time new KPIs are introduced into the evaluation framework. Based on the above, the numerical results pointed out in this study are related to this specific context and can’t be considered as universally valid; but the full potential of this model lies in its adaptability.

The implementation of the framework in ExcelTM offers some advantages, as the software package is user-friendly (especially for practitioners unfamiliar with advanced programming tools), accessible in almost any company and generally suitable for small to medium instances of decision-making problems [59,60]. Nonetheless, from a technical point of view, it could present some limits in terms of computational power, scalability and integration with enterprise information systems. Future applications may benefit from shifting the tool to more robust platforms (e.g., MATLAB, Phyton-based framework or cloud-based solutions), which would allow for enhanced data processing, automation and real-time integration with other decision support systems.

To further validate the proposed framework and verify the robustness of the applied approach, future research could also incorporate comparative analyses. These may include benchmarking the tool against alternative MCDM techniques, as well as testing the effectiveness of the approach in a different organizational setting.

Finally, although the current study relies on a single case application, similarly to other contributions in LARG-MCDM literature, future research should expand the testing of the model across multiple industries and compare its performance with alternative tools and frameworks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M., E.B. and G.C.; methodology, L.M.; software, L.M., E.B. and G.C.; investigation, L.M. and E.B.; writing—original draft preparation, L.M.; writing—review and editing, E.B., L.M. and G.C.; visualization, L.M. and E.B.; supervision, E.B.; funding acquisition, E.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR), Mission 04 Component 2 Investment 1.5 “Creation and strengthening of Ecosystems of innovation, construction of territorial leaders of R&D”—Next Generation EU, call for tender n. 3277 of 30 December 2021; MUR Project Code: ECS_00000033; research programme title: Ecosystem for Sustainable Transition in Emilia-Romagna (project acronym: ECOSISTER), awarded to the University of Parma and to the University of Bologna.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in Mendeley Data at 10.17632/typfbkk3m8.1 [43].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Company’s value, unit of measurement, benchmark and final score for lean KPIs.

Table A1.

Company’s value, unit of measurement, benchmark and final score for lean KPIs.

| KPI Indicator | Company’s Value | Unit of Measure | Benchmark Type | Benchmark Value | Final Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantity of non-compliant supplies | 3 | % | Lower is better | — | 3% |

| Inventory level (raw materials) | 30,000.00 | units | Best competitor | 50,000.00 | 60% |

| Inventory cost | 300,000.00 | euro | Lower is better | — | 300,000.00 |

| Productivity | 200 | pcs/hour | Best competitor | 250 | 80% |

| Production capacity utilization | 87 | % | Higher is better | — | 87% |

| Overall equipment effectiveness (OEE) | 80 | % | Higher is better | — | 80% |

| Set-up change impact on total production hours | 15 | % | Lower is better | — | 15% |

| Operating production time | 2.5 | hours | Lower is better | — | 2.50 |

| Cycle time | 4 | hours | Best competitor | 3 | 133.33% |

| Design time | 5 | months | Best competitor | 3.5 | 142.86% |

| Development costs | 250,000.00 | euro | Lower is better | — | 250,000.00 |

| Inventory level (consumables and semi-finished goods) | 20,000.00 | units | Best competitor | 25,000.00 | 80% |

| Rework and defect cost | 15,000.00 | euro | Lower is better | — | 15,000.00 |

| Material loss due to operations (e.g., transfer to other containers) | 1 | % | Lower is better | — | 1% |

| Full truckload (FTL) deliveries vs. less-than-truckload (LTT) | 85 | % | Higher is better | — | 85% |

| Total order fulfillment time | 4 | days | Lower is better | — | 4.00 |

| Marketing cost | 50,000.00 | euro | Lower is better | — | 50,000.00 |

| Average monthly sales | 250 | absolute number | Higher is better | — | 250 |

| Sales effectiveness | 92 | % | Higher is better | — | 92% |

| Profit margin on sales | 25 | % | Higher is better | — | 25% |

| Inventory level (finished products) | 15,000.00 | units | Best competitor | 15,000.00 | 100% |

| Customer satisfaction | 86 | % | Higher is better | — | 86% |

| Annual training hours per employee | 40 | hours | Average training hours in Italy | 40 | 100% |

| Employee perception of work environment | 87 | % | Higher is better | — | 87% |

Table A2.

Company’s value, unit of measurement, benchmark and final score for agile KPIs.

Table A2.

Company’s value, unit of measurement, benchmark and final score for agile KPIs.

| KPI Indicator | Company’s Value | Unit of Measure | Benchmark Type | Benchmark Value | Final Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proximity to suppliers | 30 | Km | Best competitor | 15 | 200% |

| Number of nodes in the supply chain | 15 | absolute number | Best competitor | 20 | 75% |

| Supplier flexibility | 75 | % | Higher is better | — | 75% |

| Supplier response time (supplier lead time) | 2 | Hours | Lower is better | — | 2.00 |

| Supplier involvement in product development | 40 | % | Best competitor | 45 | 88.89% |

| Production mix flexibility | 77 | % | Best competitor | 85 | 90.59% |

| Total production time | 4 | Hours | Best competitor | 2.5 | 160% |

| Overtime hours | 2 | Hours | Best competitor | 1 | 200% |

| Quantity of defective products | 2 | % | Lower is better | — | 2% |

| Number of bottlenecks | 1 | absolute number | Lower is better | — | 1.00 |

| Delivery error rate | 5 | % | Lower is better | — | 5% |

| Delivery frequency (No. of actual deliveries/No. of scheduled deliveries) | 95 | % | Best competitor | 97 | 97.94% |

| Delivery punctuality | 90 | % | Higher is better | — | 90% |

| Delivery flexibility | 80 | % | Higher is better | — | 80% |

| Timeliness | 87 | % | Higher is better | — | 87% |

| Speed of inventory turnover to sales | 23 | Days | Best competitor | 10 | 230% |

| Inventory turnover ratio | 4 | absolute number | Best competitor | 6 | 66.67% |

| Problem resolution time after service request | 1.5 | Days | Lower is better | — | 1.50 |

| Customer service rating | 8.5 | absolute number | Best competitor | 9 | 94.44% |

| Flexibility defined as the ability to process and recover parts/products from various sources (Return flexibility) | 75 | % | Best competitor | 82 | 91.46% |

| Response time to return request | 3 | Hours | Lower is better | — | 3.00 |

Table A3.

Company’s value, unit of measurement, benchmark and final score for resilient KPIs.

Table A3.

Company’s value, unit of measurement, benchmark and final score for resilient KPIs.

| KPI Indicator | Company’s Value | Unit of Measure | Benchmark Type | Benchmark Value | Final Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supplier lead time | 15 | Days | Best competitor | 10 | 150% |

| Supplier flexibility | 83 | % | Higher is better | — | 83% |

| Availability of alternative supplies | 85 | % | Higher is better | — | 85% |

| Inventory adjustment time | 13 | Days | Best competitor | 8 | 162.50% |

| Average time for preventive maintenance | 4 | Hours | Lower is better | — | 4.00 |

| Mean time between failures (MTBF) | 2 | Months | Lower is better | — | 2.00 |

| Mean time to repair (MTTR) | 2.5 | Hours | Lower is better | — | 2.50 |

| Average downtime | 2.7 | Hours | Lower is better | — | 2.70 |

| Percentage of reworked or modified products | 2 | % | Lower is better | — | 2% |

| Component standardization percentage | 70 | % | Best competitor | 55 | 127.27% |

| Product customization | 30 | % | Best competitor | 45 | 66.67% |

| Product range breadth | 100 | absolute number | Best competitor | 150 | 66.67% |

| Distribution channel resilience | 93 | % | Higher is better | — | 93% |

| Demand satisfaction | 97 | % | Higher is better | — | 97% |

Table A4.

Hierachical structure of lean KPIs.

Table A4.

Hierachical structure of lean KPIs.

| Level | KPI1 | KPI2 | Final Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Design time | Development costs | Design and Development |

| 2 | Set-up change impact on total production hours | Operating production time | Operational Timing |

| 2 | Cycle time | Design and Development | Design Timing |

| 2 | Average monthly sales | Sales effectiveness | Sales |

| 2 | Profit margin on sales | Inventory level (finished products) | Finished Product |

| 3 | Production capacity utilization | Overall equipment effectiveness (OEE) | Production Line Efficiency |

| 3 | Operational Timing | Design Timing | Production Time |

| 3 | Rework and defect cost | Inventory level (consumables and semi-finished goods) | Work-In-Progress Product |

| 3 | Sales | Finished Product | Sales Quality |

| 3 | Material loss due to operations (e.g., transfer to other containers) | Full truckload (FTL) deliveries vs. less-than-truckload (LTT) | Shipping Efficiency |

| 4 | Inventory cost | Inventory level (raw materials) | Inventory |

| 4 | Production Line Efficiency | Productivity | Production Line Utilization |

| 4 | Production Time | Work-In-Progress Product | Production Efficiency |

| 4 | Sales Effectiveness | Marketing cost | Sales Service |

| 4 | Shipping Efficiency | Total order fulfillment time | Shipping Quality |

| 4 | Annual training hours per employee | Employee perception of work environment | Work Environment Quality |

| 5 | Inventory | Quantity of non-compliant supplies | Procurement |

| 5 | Production Line Utilization | Production Efficiency | Production |

| 5 | Sales Service | Shipping Quality | Distribution |

| 5 | Customer satisfaction | Work Environment Quality | Reverse Logistics |

Table A5.

Hierarchical structure of agile KPIs.

Table A5.

Hierarchical structure of agile KPIs.

| Level | KPI1 | KPI2 | Final Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Delivery error rate (%) | Delivery frequency (No. of actual deliveries/No. of scheduled deliveries) | Successful deliveries |

| 1 | Delivery punctuality | Timeliness | Delivery accuracy |

| 2 | Successful deliveries | Delivery accuracy | Delivery accuracy |

| 3 | Supplier flexibility | Supplier response time (supplier lead time) | Supplier efficiency |

| 3 | Quantity of defective products | Number of bottlenecks | Production inefficiencies |

| 3 | Total production time | Overtime hours | Production timing |

| 3 | Speed of inventory turnover to sales | Inventory turnover ratio | Inventory management |

| 3 | Delivery accuracy | Delivery flexibility | Delivery efficiency |

| 4 | Supplier efficiency | Proximity to suppliers | Supplier evaluation |

| 4 | Production inefficiencies | Production timing | Production operational efficiency |

| 4 | Production mix flexibility | Supplier involvement in product development | Product development |

| 4 | Customer service rating | Problem resolution time after service request | After-sales service |

| 4 | Inventory management | Delivery efficiency | Shipping |

| 5 | Number of nodes in the supply chain | Supplier evaluation | Procurement |

| 5 | Production operational efficiency | Product development | Production |

| 5 | After-sales service | Shipping | Distribution |

| 5 | Flexibility defined as the ability to process and recover parts/products even from different origins (Return flexibility) | Response time to return request | Reverse logistics |

Table A6.

Hierarchical structure of resilient KPIs.

Table A6.

Hierarchical structure of resilient KPIs.

| Level | KPI1 | KPI2 | Final Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Product range breadth | Product customization | Production flexibility |

| 2 | Average downtime | Average time for preventive maintenance | Scheduled downtime |

| 2 | Mean time between failures | Mean time to repair failures | Failure management |

| 2 | Production flexibility | Percentage of component standardization | Product range |

| 2 | Demand satisfaction | Percentage of lost sales | Sales effectiveness |

| 3 | Availability of alternative supplies | Inventory adjustment time | Inventory management |

| 3 | Supplier lead time | Supplier flexibility | Supplier timing and flexibility |

| 3 | Scheduled downtime | Failure management | Downtime |

| 3 | Product range | Percentage of reworked or modified products | Product quality |

| 3 | Safety stock quantity | Inventory coverage time | Inventory management |

| 3 | Sales effectiveness | Distribution channel resilience | Sales service |

| 3 | Average customer tenure | Customer retention (CRR) | Customer base |

| 4 | Inventory management | Supplier timing and flexibility | Procurement |

| 4 | Downtime | Product quality | Production |

| 4 | Inventory management | Sales service | Distribution |

| 4 | Customer satisfaction and loyalty | Customer base | Reverse Logistics |

Appendix B

Table A7.

Fuzzy range of lean KPIs.

Table A7.

Fuzzy range of lean KPIs.

| KPI | Linguistic Judgment | a | b | c | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantity of non-compliant supplies | Very high | 0% | 0% | 2% | 3% |

| high | 2% | 3% | 4% | 5% | |

| low | 4% | 5% | 6% | 7% | |

| Very low | 6% | 7% | 10% | 10% | |

| Inventory level (raw materials) | Very low | 0% | 0% | 10% | 20% |

| low | 10% | 20% | 30% | 50% | |

| high | 30% | 50% | 70% | 100% | |

| Very high | 70% | 100% | 150% | 150% | |

| Inventory cost | Very low | 0 | 0 | 30,000 | 40,000 |

| low | 40,000 | 60,000 | 80,000 | 100,000 | |

| high | 80,000 | 100,000 | 120,000 | 150,000 | |

| Very high | 200,000 | 300,000 | 500,000 | 500,000 | |

| Productivity | Very high | 0% | 0% | 10% | 20% |

| high | 20% | 30% | 40% | 50% | |

| low | 50% | 70% | 90% | 100% | |

| Very low | 90% | 100% | 150% | 150% | |

| Production capacity utilization/Overall equipment effectiveness (OEE)/Set-up change impact on total production hours | Very high | 0% | 0% | 50% | 55% |

| high | 50% | 55% | 70% | 75% | |

| low | 70% | 75% | 88% | 95% | |

| Very low | 88% | 95% | 100% | 100% | |

| Operating production time | Very high | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| high | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| low | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Very low | 6 | 7 | 12 | 12 | |

| Cycle time/Design time/Inventory level (finished products)/Annual training hours per employee | Very low | 0% | 0% | 60% | 70% |

| low | 60% | 70% | 80% | 90% | |

| high | 80% | 90% | 95% | 100% | |

| Very high | 95% | 100% | 200% | 200% | |

| Development costs | Very low | 0 | 0 | 200,000 | 250,000 |

| low | 200,000 | 250,000 | 300,000 | 350,000 | |

| high | 300,000 | 350,000 | 375,000 | 400,000 | |

| Very high | 375,000 | 400,000 | 450,000 | 450,000 | |

| Inventory level (consumables and semi-finished goods) | Very low | 0% | 0% | 10% | 20% |

| low | 20% | 30% | 40% | 50% | |

| high | 50% | 70% | 90% | 100% | |

| Very high | 90% | 100% | 150% | 150% | |

| Rework and defect cost | Very high | 0 | 0 | 10,000 | 15,000 |

| high | 10,000 | 15,000 | 20,000 | 25,000 | |

| low | 20000 | 25,000 | 30,000 | 35,000 | |

| Very low | 30,000 | 35,000 | 50,000 | 50,000 | |

| Material loss due to operations (e.g., transfer to other containers) | Very high | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.0% | 1.5% |

| high | 1.0% | 1.5% | 1.7% | 2.0% | |

| low | 1.7% | 2.0% | 2.5% | 2.7% | |

| Very low | 2.5% | 2.7% | 5.0% | 5.0% | |

| Full truckload (FTL) deliveries vs. less-than-truckload (LTT)/Sales effectiveness/Customer satisfaction/Employee perception of work environment | Very low | 0% | 0% | 50% | 55% |

| low | 50% | 55% | 70% | 75% | |

| high | 70% | 75% | 88% | 95% | |

| Very high | 88% | 95% | 100% | 100% | |

| Total order fulfillment time | Very high | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| high | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| low | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Very low | 6 | 7 | 10 | 10 | |

| Inventory cost | Very high | 0 | 0 | 30,000 | 35,000 |

| high | 30,000 | 35,000 | 45,000 | 50,000 | |

| low | 45,000 | 50,000 | 55,000 | 60,000 | |

| Very low | 55,000 | 60,000 | 100,000 | 100,000 | |

| Marketing cost | Very low | 0 | 0 | 30,000 | 35,000 |

| low | 30,000 | 35,000 | 45,000 | 50,000 | |

| high | 45,000 | 50,000 | 55,000 | 60,000 | |

| Very high | 55,000 | 60,000 | 100,000 | 100,000 | |

| Average monthly sale | Very low | 0 | 0 | 100 | 150 |

| low | 100 | 150 | 200 | 250 | |

| high | 200 | 250 | 300 | 350 | |

| Very high | 300 | 350 | 500 | 500 | |

| Profit margin on sales | Very low | 0% | 0% | 5% | 10% |

| low | 5% | 10% | 15% | 20% | |

| high | 15% | 20% | 25% | 30% | |

| Very high | 25% | 30% | 40% | 40% |

Table A8.

Fuzzy range of agile KPIs.

Table A8.

Fuzzy range of agile KPIs.

| KPI | Linguistic Judgment | a | b | c | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supplier proximity | Very low | 0 | 0 | 15 | 20 |

| Low | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | |

| High | 25 | 30 | 40 | 50 | |

| Very High | 40 | 50 | 100 | 100 | |

| Number of supply chain nodes | Very low | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| Low | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| High | 5 | 6 | 8 | 10 | |

| Very High | 8 | 10 | 15 | 15 | |

| Supplier flexibility/Supplier involvement in product development/Production mix flexibility/Delivery frequency (actual/planned)/Delivery punctuality/Timeliness/Support service evaluation/Returns flexibility (handling from multiple sources) | Very low | 0% | 0% | 50% | 55% |

| Low | 50% | 55% | 70% | 75% | |

| High | 70% | 75% | 88% | 95% | |

| Very High | 88% | 95% | 100% | 100% | |

| Supplier response time (lead time) | Very High | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| High | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Low | 4 | 5 | 8 | 10 | |

| Very low | 8 | 10 | 20 | 20 | |

| Total production time | Very High | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| High | 3 | 4 | 5 | 7 | |

| Low | 5 | 7 | 10 | 15 | |

| Very low | 10 | 15 | 30 | 30 | |

| Overtime hours | Very High | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| High | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Low | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Very low | 7 | 8 | 10 | 10 | |

| Defective products percentage | Very low | 0.00% | 0.00% | 2.00% | 3.00% |

| Low | 2.00% | 3.00% | 4.00% | 5.00% | |

| High | 4.00% | 5.00% | 6.00% | 7.00% | |

| Very High | 6.00% | 7.00% | 10.00% | 10.00% | |

| Number of bottlenecks/Inventory turnover index/Issue resolution time (support requests)/Return request response time | Very low | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Low | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| High | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Very High | 6 | 7 | 10 | 10 | |

| Delivery error percentage | Very low | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| Low | 3 | 4 | 7 | 9 | |

| High | 7 | 9 | 11 | 15 | |

| Very High | 11 | 15 | 30 | 30 | |

| Delivery flexibility | Very High | 0% | 0% | 50% | 55% |

| High | 50% | 55% | 70% | 75% | |

| Low | 70% | 75% | 88% | 95% | |

| Very low | 88% | 95% | 100% | 100% | |

| Inventory-to-sales transformation speed | Very low | 0 | 0 | 15 | 20 |

| Low | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | |

| High | 25 | 30 | 35 | 40 | |

| Very High | 35 | 40 | 50 | 50 |

Table A9.

Fuzzy range of resilient KPIs.

Table A9.

Fuzzy range of resilient KPIs.

| KPI | Linguistic Judgment | a | b | c | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supplier lead time | Very high | 0 | 0 | 5 | 10 |

| High | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | |

| Low | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | |

| Very low | 25 | 30 | 40 | 40 | |

| Supplier flexibility/Availability of alternative supplies/Customer satisfaction and loyalty/Distribution channel resilience | Very low | 0% | 0% | 50% | 55% |

| Low | 50% | 55% | 70% | 75% | |

| High | 70% | 75% | 88% | 95% | |

| Very high | 88% | 95% | 100% | 100% | |

| Inventory adjustment time/Mean time to repair failures | Very high | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| High | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Low | 6 | 7 | 10 | 12 | |

| Very low | 10 | 12 | 20 | 20 | |

| Preventive maintenance time/Mean time between failures/Mean downtime | Very high | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| High | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Low | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Very low | 6 | 7 | 10 | 10 | |

| % of reworked or modified products/Demand satisfaction | Very high | 0% | 0% | 50% | 55% |

| High | 50% | 55% | 70% | 75% | |

| Low | 70% | 75% | 88% | 95% | |

| Very low | 88% | 95% | 100% | 100% | |

| % component standardization/Product customization | Very low | 0% | 0% | 60% | 70% |

| Low | 60% | 70% | 80% | 90% | |

| High | 80% | 90% | 95% | 100% | |

| Very high | 95% | 100% | 200% | 200% | |

| Product range breadth/Inventory coverage time/Customer average tenure | Very low | 0% | 0% | 10% | 20% |

| Low | 10% | 20% | 40% | 50% | |

| High | 40% | 50% | 90% | 100% | |

| Very high | 90% | 100% | 150% | 150% | |

| % lost sales | Very high | 0% | 0% | 2% | 3% |

| High | 2% | 3% | 5% | 8% | |

| Low | 5% | 8% | 10% | 12% | |

| Very low | 10% | 12% | 15% | 15% | |

| Safety stock quantity/Customer Retention Rate (CRR) | Very low | 0% | 0% | 10% | 20% |

| Low | 20% | 30% | 40% | 50% | |

| High | 50% | 70% | 90% | 100% | |

| Very high | 90% | 100% | 150% | 150% |

Appendix C

Table A10.

Linguistic judgment and membership degree of lean KPIs.

Table A10.

Linguistic judgment and membership degree of lean KPIs.

| KPI | Linguistic Judgment | Degree of Membership |

|---|---|---|

| Quantity of non-compliant supplies | Very High | 0 |

| High | 1 | |

| Inventory level (raw materials) | High | 1 |

| Inventory cost | Very High | 1 |

| Productivity | Low | 1 |

| Production capacity utilization | Low | 1 |

| Overall equipment effectiveness | Low | 1 |

| Impact of setup change on total production hours | Very High | 1 |

| Operational production time | Very High | 0.5 |

| High | 0.5 | |

| Cycle time | Very High | 1 |

| Design time | Very High | 1 |

| Development costs | Very Low | 0 |

| Low | 1 | |

| Stock level (consumables and semi-finished materials) | High | 1 |

| Rework and defect costs | Very High | 0 |

| High | 1 | |

| Material loss due to operations (transfer to other containers) | Very High | 1 |

| High | 0 | |

| Full truckload (ftl) deliveries vs. Less-than-truckload (ltl) | High | 1 |

| Total order fulfillment time | High | 1 |

| Low | 0 | |

| Marketing cost | Low | 0 |

| High | 1 | |

| Average monthly sales | Low | 0 |

| High | 1 | |

| Sales effectiveness | High | 0.43 |

| Very High | 0.57 | |

| Profit margin on sales | High | 1 |

| Very High | 0 | |

| Stock level (finished goods) | High | 0 |

| Very High | 1 | |

| Customer satisfaction | High | 1 |

| Annual training hours per employee | High | 0 |

| Very High | 1 | |

| Employee perception of the work environment | High | 1 |

Table A11.

Linguistic judgment and membership degree of agile KPIs.

Table A11.

Linguistic judgment and membership degree of agile KPIs.

| KPI | Linguistic Judgment | Degree of Membership |

|---|---|---|

| Proximity to suppliers | Very Low | 1 |

| Number of nodes in the supply chain | Very Low | 1 |

| Supplier flexibility | Low | 0 |

| High | 1 | |

| Supplier response time (lead time) | Very High | 1 |

| High | 0 | |

| Supplier involvement in product development | High | 0.87 |

| Very High | 0.13 | |

| Production mix flexibility | High | 0.63 |

| Very High | 0.37 | |

| Total production time | Very High | 1 |

| Overtime hours | Very High | 1 |

| High | 0 | |

| Quantity of defective products | Very Low | 1 |

| Low | 0 | |

| Number of bottlenecks | Very Low | 1 |

| % Delivery errors | Very Low | 1 |

| Delivery frequency (actual deliveries/scheduled deliveries) | Very High | 1 |

| Delivery punctuality | High | 0.71 |

| Very High | 0.29 | |

| Delivery flexibility | Low | 1 |

| Promptness | High | 1 |

| Speed of inventory turnover | Very Low | 1 |

| Inventory turnover index | Very Low | 1 |

| Time to resolve service request | Very Low | 1 |

| Service evaluation | High | 0.08 |

| Very High | 0.92 | |

| Flexibility understood as the ability to handle and recover parts/products even from different origins (return flexibility) | High | 0.51 |

| Very High | 0.49 | |

| Response time to return request | Very High | 0 |

| High | 1 |

Table A12.

Linguistic judgment and membership degree of resilient KPIs.

Table A12.

Linguistic judgment and membership degree of resilient KPIs.

| KPI | Linguistic Judgment | Degree of Membership |

|---|---|---|

| Supplier lead time | Very High | 1 |

| Supplier flexibility | High | 1 |

| Availability of alternative supplies | High | 1 |

| Inventory adjustment time | Very High | 1 |

| Average time for preventive maintenance | High | 1 |

| Average time for preventive maintenance | Low | 0 |

| Mean time between failures | Very High | 1 |

| High | 0 | |

| Average repair time for failures | Very High | 1 |

| Average downtime | Very High | 0.3 |

| High | 0.7 | |

| Percentage of reworked or modified products | Very High | 1 |

| Percentage of component standardization | Very High | 1 |

| Product customization | Very Low | 0.33 |

| Low | 0.67 | |

| Product range breadth | High | 1 |

| Resilience of distribution channels | High | 0.29 |

| Very High | 0.71 | |

| Demand satisfaction | Very Low | 1 |

| Average customer tenure | High | 1 |

| Percentage of lost sales | Very High | 1 |

| High | 0 | |

| Inventory coverage time | Low | 0 |

| High | 1 | |

| Quantity of safety stock | High | 0.83 |

| Customer retention (CRR) | High | 0.56 |

| Very High | 0.44 | |

| Customer satisfaction and loyalty | High | 1 |

Appendix D

Table A13.

Aggregation of green KPIs for inference process.

Table A13.

Aggregation of green KPIs for inference process.

| KPI1 | KPI2 | Final KPI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KPI1 | Linguistic Judgment | Membership Degree | KPI2 | Linguistic Judgment | Membership Degree | Final KPI | Linguistic Judgment | Membership Degree |

| Energy consumed produced from fossil And renewable sources | High | 1 | Energy Consumption | Low | 0.6 | Electricity | Average | 0.6 |

| Energy consumed produced from fossil And renewable sources | High | 1 | Energy Consumption | High | 0.4 | Electricity | High | 0.4 |

| Water Consumed | Low | 0.83 | Electricity | Average | 0.6 | Utilities | Low | 0.5 |

| Water Consumed | Low | 0.83 | Electricity | High | 0.4 | Utilities | Average | 0.33 |

| Water Consumed | Very Low | 0.167 | Electricity | Average | 0.6 | Utilities | Low | 0.1 |

| Water Consumed | Very Low | 0.167 | Electricity | High | 0.4 | Utilities | Low | 0.06 |

| Suppliers with environmental certifications | Very High | 1 | Use of renewable materials | Low | 1 | Green supply | High | 1 |

| Suppliers with environmental certifications | Very High | 1 | Use of renewable materials | High | 0 | Green supply | Very High | 0 |

| Sanitation costs | Low | 0.6 | Human capital | High | 0.97 | Human Factor | Average | 0.58 |

| Sanitation costs | Low | 0.6 | Human capital | Very High | 0.03 | Human Factor | High | 0.02 |

| Sanitation sosts | High | 0.4 | Human capital | High | 0.97 | Human Factor | High | 0.39 |

| Sanitation costs | High | 0.4 | Human Capital | Very High | 0.03 | Human Factor | Very High | 0.01 |

| Compliant products | High | 0 | Number of smart tasks | High | 1 | Production Efficiency | High | 0 |

| Compliant products | Very High | 1 | Number of smart tasks | High | 1 | Production Efficiency | Very High | 1 |

| Cost of raw materials | Very Low | 1 | Green Supply | High | 1 | Procurement | Low | 1 |

| Cost of raw materials | Very Low | 1 | Green supply | Very High | 0 | Procurement | Average | 0 |

| Utilities | Low | 0.67 | Human factor | Average | 0.58 | Resources needed for production | Low | 0.39 |

| Utilities | Low | 0.67 | Human factor | High | 0.41 | Resources needed for production | Average | 0.27 |

| Utilities | Low | 0.67 | Human factor | Very High | 0.01 | Resources needed for production | High | 0.01 |

| Utilities | Average | 0.33 | Human factor | Average | 0.58 | Resources needed for production | Average | 0.19 |

| Utilities | Average | 0.33 | Human factor | High | 0.41 | Resources needed for production | High | 0.14 |

| Utilities | Average | 0.33 | Human factor | Very High | 0.01 | Resources needed for production | High | 0.01 |

| Waste index | Very High | 1 | Production efficiency | High | 0 | Efficiency | Very High | 0 |

| Waste index | Very High | 1 | Production Efficiency | Very High | 1 | Efficiency | Very High | 1 |

| CO2 emissions | Low | 1 | Fuel Consumption | Very Low | 1 | Environmental Impact | Very Low | 1 |

| Route Efficiency | High | 0.71 | Vehicle Load Rate | Low | 0 | Distribution Efficiency | Average | 0 |

| Route Efficiency | High | 0.71 | Vehicle Load Rate | High | 1 | Distribution Efficiency | High | 0.71 |

| Route Efficiency | Very High | 0.29 | Vehicle Load Rate | Low | 0 | Distribution Efficiency | High | 0 |

| Route Efficiency | Very High | 0.29 | Vehicle Load Rate | High | 1 | Distribution Efficiency | Very High | 0.29 |

| Cost of waste | Low | 0.6 | Recycled packaging quantity | Very High | 1 | Reverse Logistics | High | 0.6 |

| Cost of waste | High | 0.4 | Recycled packaging quantity | Very High | 1 | Reverse Logistics | Very High | 0.4 |

| Resources needed for production | Low | 0.39 | Efficiency | Very High | 1 | Production | High | 0.386554622 |

| Resources needed for production | Average | 0.46 | Efficiency | Very High | 1 | Production | High | 0.46 |

| Resources needed for production | High | 0.15 | Efficiency | Very High | 1 | Production | Very High | 0.15 |

| Environmental impact | Very Low | 1 | Distribution Efficiency | Average | 0 | Distribution | Low | 0 |

| Environmental impact | Very Low | 1 | Distribution Efficiency | High | 0.714285714 | Distribution | Low | 0.71 |

| Environmental impact | Very Low | 1 | Distribution Efficiency | Very High | 0.285714286 | Distribution | Average | 0.29 |

Table A14.

Inference results of lean KPIs.

Table A14.

Inference results of lean KPIs.

| Indicator | Linguistic Judgment | Final Truth Value |

|---|---|---|

| Design and development | Average | 0 |

| High | 1 | |

| Operational timing | Very High | 1 |

| Design timing | High | 0 |

| Very High | 1 | |

| Sales | Average | 0 |

| High | 0.43 | |

| Very High | 0.57 | |

| Finished product | High | 0 |

| Very High | 1 | |

| Production line efficiency | Low | 1 |

| Production time | Very High | 1 |

| Work-in-progress product | Very High | 0 |

| High | 1 | |

| Sales quality | High | 0 |

| Very High | 1 | |

| Shipping efficiency | Very High | 1 |

| High | 0 | |

| Inventory | Very High | 1 |

| Production line utilization | Low | 1 |

| Production efficiency | Very High | 1 |

| Sales service | Average | 0 |

| High | 0.43 | |

| Very High | 0.57 | |

| Shipping quality | Very High | 1 |

| High | 0 | |

| Average | 0 | |

| Work environment quality | High | 0 |

| Very High | 1 | |

| Procurement | Very High | 1 |

| Production | High | 1 |

| Distribution | High | 0 |

| Average | 0 | |

| Very High | 1 | |

| Reverse logistics | High | 0 |

| Very High | 1 |

Table A15.

Inference results of agile KPIs.

Table A15.

Inference results of agile KPIs.

| Indicator | Linguistic Judgment | Final Truth Value |

|---|---|---|

| Deliveries Successfully Completed | Average | 1 |

| Delivery Precision | High | 0.71 |

| Very High | 0.29 | |

| Delivery Accuracy | High | 1 |

| Supplier Efficiency | High | 0 |

| Average | 0 | |

| Very High | 1 | |

| Production Inefficiencies | Very Low | 1 |

| Production Timing | Very High | 1 |

| Inventory Management | Very Low | 1 |

| Delivery Efficiency | Average | 1 |

| Supplier Evaluation | Low | 0 |

| Average | 1 | |

| Operational Production Efficiency | Average | 1 |

| Product Development | High | 0.55 |

| Very High | 0.45 | |

| After-Sales Service | Low | 0.08 |

| Average | 0.92 | |

| Shipping | Low | 1 |

| Procurement | Very Low | 0 |

| Low | 1 | |

| Production | High | 1 |

| Distribution | Low | 1 |

| Reverse Logistics | Very High | 0.49 |

| High | 0.51 |

Table A16.

Inference results of resilient KPIs.

Table A16.

Inference results of resilient KPIs.

| Indicator | Linguistic Judgment | Final Truth Value |

|---|---|---|

| Production Flexibility | Low | 0.33 |

| Average | 0.67 | |

| Scheduled Downtimes | Very High | 0.3 |

| High | 0.7 | |

| Average | 0 | |

| Breakdown Management | Very High | 1 |

| Product Range | High | 1 |

| Sales Effectiveness | Average | 1 |

| Low | 0 | |

| Inventory Management | Very High | 1 |

| Supplier Timing And Flexibility | Very High | 1 |

| Downtimes | Very High | 1 |

| High | 0 | |

| Production Quality | Very High | 1 |

| Stock Management | Average | 0 |

| High | 0.83 | |

| Sales Service | High | 1 |

| Average | 0 | |

| Customer Base | High | 0.56 |

| Very High | 0.44 | |

| Procurement | Very High | 1 |

| Production | Very High | 1 |

| Distribution | High | 0.83 |

| Average | 0 | |

| Reverse Logistics | High | 0.56 |

| Very High | 0.44 |

References

- Lotfi, M.; Saghiri, S. Disentangling resilience, agility and leanness: Conceptual development and empirical analysis. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2018, 29, 168–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, P.; Ghorai, S.; Jha, R.; Datt, R.; Sulapu, G.; Singh, S. Forecasting the impact of epidemic outbreaks on the supply chain: Modelling asymptomatic cases of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 61, 2670–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, S.; Carvalho, H.; Cruz-Machado, V. A proposal of LARG supply chain management practices and a performance measurement system. Int. J. e-Educ. e-Bus. e-Manag. e-Learn. 2011, 1, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, T. The Toyota Production System; Productivity Press: Portland, OR, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Womack, J.; Jones, D.; Roos, D. The Machine That Change the World; HarperCollins Publisher: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Reichhart, A.; Holweg, M. Lean distribution: Concepts, contributions, conflicts. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2007, 45, 3699–3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, M.; Rao, T. An integrated approach to design and analysis of lean manufacturing system: A perspective of lean supply chain. Int. J. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2009, 5, 175–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melton, T. The benefits of lean manufacturing: What lean thinking has to offer the process industries. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2005, 83, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Shankar, R.; Tiwari, M.K. Modeling agility of supply chain. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2007, 36, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M. The agile supply chain: Competing in volatile markets. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2000, 29, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baramichai, M.; Zimmers, E.W., Jr.; Marangos, C.A. Agile supply chain transformation matrix: An integrated tool for creating an agile enterprise. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2007, 12, 334–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swafford, P.M.; Ghosh, S.; Murthy, N. Achieving supply chain agility through IT integration and flexibility. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 116, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsby, T.J.; Griffis, S.E.; Roath, A.S. Modeling lean, agile, and leagile supply chain strategies. J. Bus. Logist. 2006, 27, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haimes, Y.Y. On the definition of vulnerabilities in measuring risks to infrastructures. Risk Anal. Int. J. 2006, 26, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, J.B.; Caniato, F. Building a secure and resilient supply network. Supply Chain. Manag. Rev. 2003, 7, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hansson, S.O.; Helgesson, G. What is stability? Synthese 2003, 136, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S. Robust strategies for mitigating supply chain disruptions. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2006, 9, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M.; Peck, H. Building the resilient supply chain. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2004, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iakovou, E.; Vlachos, D.; Xanthopoulos, A. An analytical methodological framework for the optimal design of resilient supply chains. Int. J. Logist. Econ. Glob. 2007, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.; Holt, D. Do green supply chains lead to competitiveness and economic performance? Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2005, 25, 898–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, H.; Govindan, K.; Azevedo, S.G.; Cruz-Machado, V. Modelling green and lean supply chains: An eco-efficiency perspective. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 120, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiyazhagan, K.; NoorulHaq, A.; Geng, Y. An ISM approach for the barrier analysis in implementing green supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 47, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Raut, R.D.; Mangla, S.K.; Narkhede, B.E.; Luthra, S.; Gokhale, R. A systematic literature review to integrate lean, agile, resilient, green and sustainable paradigms in the supply chain management. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 1191–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Chen, X.; Sun, H.; Yan, W.; Fang, H. Hierarchical structure of a green supply chain. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 157, 107303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]