Comparison of Motivation Types, Self-Assessment of Sport Skills, and Fitness Among Young Adolescents Regarding Additional Physical Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Is there any difference in types of motivation between adolescent boys and girls with respect to participation in additional after-school sports activities?

- Is there any difference in self-assessment of tactical and technical sports skills between adolescent boys and girls with respect to participation in after-school sports activities?

- Is there any difference in self-assessed overall physical fitness between adolescent boys and girls with respect to participation in additional after-school sports activities?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Research Design

2.3. Motivation

2.4. Sport Skills Competency

2.5. The International Fitness Scale (IFIS)

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PA | Physical Activity |

References

- Hoare, E.; Staverski, B.; Jennings, G.; Kingwell, B.A. Exploring Motivation and Barriers to Physical Activity among Active and Inactive Australian Adults. Sports 2017, 5, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blonska, K. Impact of Physical Activity on Students’ Happiness in the Context of Positive and Negative Motivation. Phys. Educ. Stud. 2022, 26, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, S.; Dickerhoof, R.; Boehm, J.; Sheldon, K.M. Becoming Happier Takes Both a Will and a Proper Way: An Experimental Longitudinal Intervention to Boost Well-Being. Emotion 2011, 11, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K.; Lyubomirsky, S. Revisiting the Sustainable Happiness Model and Pie Chart: Can Happiness Be Successfully Pursued? J. Posit. Psychol. 2019, 16, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Organization. WHO Highlights High Cost of Physical Inactivity in First-Ever Global Report. Available online: www.who.int/news/item/19-10-2022-who-highlights-high-cost-of-physical-inactivity-in-first-ever-global-report (accessed on 19 October 2024).

- Mehmeti, I.; Halilaj, B. How to Increase Motivation for Physical Activity among Youth. Sport Mont 2018, 16, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Sluijs, E.; Ekelund, U.; Crochemore-Silva, I.; Guthold, R.; Ha, A.; Lubans, D.; Oyeyemi, A.L.; Ding, D.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. Physical Activity Behaviours in Adolescence: Current Evidence and Opportunities for Intervention. Lancet 2021, 398, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.; Riley, L.; Bull, F.C. Global Trends in Insufficient Physical Activity among Adolescents: A Pooled Analysis of 298 Population-Based Surveys with 1·6 Million Participants. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zembura, P.; Korcz, A.; Cieśla, E.; Nałęcz, H. Raport o Stanie Aktywności Fizycznej Dzieci i Młodzieży w Polsce w Ramach Projektu Global Matrix 4.0; Fundacja V4Sport: Wrocław, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Makaruk, H.; Kipling Webester, E.; Porter, J.; Makaruk, B.; Bodasińska, A.; Zieliński, J.; Tomaszewski, P.; Nogal, M.; Szyszka, P.; Starzak, M.; et al. The Fundamental Motor Skill Proficiency among Polish Primary School-Aged Children: A Nationally Representative Surveillance Study. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2023, 27, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zablotsky, B.; Arockiaraj, B.; Haile, G.; Ng, A.E. Daily Screen Time among Teenagers: United States, July 2021–December 2023. NCHS Data Brief 2024, 513, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, L.; Behme, N.; Breuer, C. Physical Activity of Children and Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic—A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leksy, K. Physical Activity of Children and Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Review of Research and Recommendations for Pedagogical Practice Probl. Opiekuńczo-Wychowawcze 2022, 606, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronikowska, M.; Krzysztoszek, J.; Łopatka, M.; Ludwiczak, M.; Pluta, B. Comparison of Physical Activity Levels in Youths before and during a Pandemic Lockdown. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longfield, A. Young Lives, Big Ambitions; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Portela-Pino, I.; Lopez-Castedo, A.; Martinez-Patino, M.; Valverde-Esteve, T.; Domínguez-Alonso, J. Gender Differences in Motivation and Barriers for the Practice of Physical Exercise in Adolescence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 17, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peykari, N.; Baradaran Eftekhari, M.; Ramezani Tehrani, F.; Afzali, H.M.; Hejazi, F.; Atoofi, M.K.; Qorbani, M.; Asayesh, H. Promoting Physical Activity Participation among Adolescents: The Barriers and the Suggestions. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popovych, I.; Hrys, A.; Hoian, I.; Mamchur, I.; Babenko, A.; Fedyk, O. Successfulness in teenagers’ sporting activities: Comparative analysis of individual and team sports. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2022, 22, 2886–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajewski, M. Psychologiczne i pedagogiczne aspekty motywacji do działania/aktywności młodzieży. W M. Gajewski (red.). In Współczesne Przestrzenie Aktywności Młodzieży (s. 45–71); Uniwersytet Papieski Jana Pawła II w Krakowie: Kraków, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.; Ryan, R. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Springer Science Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Espínola, C.; Tamayo-Fajardo, J.; Almagro, B.; Tamayo-Fajardo, J.A.; Sáenz-López, P. Complementing the Self-Determination Theory with the Need for Novelty: Motivation and Intention to Be Physically Active in Physical Education Students. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battistelli, A.; Montani, F.; Guicciardi, M.; Bertinato, L. Regulation of Exercise Behaviour and Motives for Physical Activities: The Italian Validation of BREQ and MPAM-R Questionnaires. Psychol. Française 2016, 61, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtowicz, A.; Bryg, A. Motivation to participate in physical education classes among the pupils of 4th–6th grades of Polish primary school and the pupils’ perception of teacher’s didactic style. Stud. Sport Humanit. 2015, 17, 18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, M.; Rees, T.; Coffee, P.; Steffens, N.K.; Haslam, S.A.; Polman, R. A Social Identity Approach to Understanding and Promoting Physical Activity. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 1911–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, C.; Ryan, R. Self-determination in sport: A review using cognitive evaluation theory. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 1995, 26, 5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, B.; Barber, B. Differences in Functional and Aesthetic Body Image between Sedentary Girls and Girls Involved in Sports and Physical Activity: Does Sport Type Make a Difference? Psychol. Sport 2011, 12, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, J.; Hearn, J. Student Self-Assessment: The Key to Stronger Student Motivation and Higher Achievement. Educ. Horiz. 2008, 87, 40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, B.; Schunk, D. Self-Regulated Learning and Academic Achievement. Springer Series in Cognitive Development; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Quatman, T.; Watson, C. Gender Differences in Adolescent Self-Esteem: An Exploration of Domains. J. Genet. Psychol. 2001, 162, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Frederick, C.M.; Lepes, D.; Rubio, N.; Sheldon, K.M. Intrinsic motivation and exercise adherence. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 1997, 28, 335–354. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, F.; Ruiz, J.; Espana-Romero, V.; Vicente-Rodriguez, G.; Martínez-Gómez, D.; Manios, Y.; Béghin, L.; Molnar, D.; Widhalm, K.; A Moreno, L.; et al. The International Fitness Scale (IFIS): Usefulness of Self-Reported Fitness in Youth. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 40, 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, D.L. Gender differences in competitive orientation and sport participation. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 1988, 19, 145–159. [Google Scholar]

- Finkenberg, M.; Teper, L. Self-Concept Profiles of Competitive Bodybuilders. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1991, 72, 1039–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivula, N. Sport participation: Differences in motivation and actual participation due to gender typing. J. Sport Behav. 1999, 22, 360–380. [Google Scholar]

- Crissey, S.; Honea, J. The Relationship between Athletic Participation and Perceptions of Body Size and Weight Control in Adolescent Girls: The Role of Sport Type. Sociol. Sport J. 2006, 23, 248–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenleaf, C.; Petrie, T.; Carter, J.; Reel, J.J. Female Collegiate Athletes: Prevalence of Eating Disorders and Disordered Eating Behaviors. J. Am. Coll. Health 2009, 57, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, P.; Harris, L. The Sporting Body: Body Image and Eating Disorder Symptomatology Among Female Athletes from Leanness Focused and Nonleanness Focused Sports. J. Psychol. 2015, 149, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krane, V.; Waldron, J.; Michalenok, J.; Stiles-Shipley, J. Body Image Concerns in Female Exercisers and Athletes: A Feminist Cultural Studies Perspective. Women Sport Phys. Act. J. 2001, 10, 17–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, M. Making Sense of Muscle: The Body Experiences of Collegiate Women Athletes. Sociol. Inq. 2005, 75, 317–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J. What Is Language Development? Rationalist, Empiricist, and Pragmatist Approaches to the Acquisition of Syntax Oxford University Press. J. Child Lang. 2007, 34, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homan, K. Athletic-Ideal and Thin-Ideal Internalization as Prospective Predictors of Body Dissatisfaction, Dieting, and Compulsive Exercise. Body Image 2010, 7, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allender, S.; Cowburn, G.; Foster, C. Understanding Participation in Sport and Physical Activity among Children and Adults: A Review of Qualitative Studies. Health Educ. Res. 2006, 21, 826–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, R.; Koulanova, A.; Sabiston, C. Understanding Girls’ Motivation to Participate in Sport: The Effects of Social Identity and Physical Self-Concept. Front. Sports Act. Living 2022, 11, 787334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, M.; Gray-Donald, K.; O’Loughlin, J.; Paradis, G.; Hanley, J. When Adolescents Drop the Ball. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 31, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, J.; Antunnes, H.; van den Tillaar, R. A Comparison between Boys and Girls about the Motives for the Participation in School Sport. J. Phys. Educ. Sport ® (JPES) 2013, 13, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilhjalmsson, R.; Kristjansdottir, G. Gender Differences in Physical Activity in Older Children and Adolescents: The Central Role of Organized Sport. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 56, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicki, Z.; Görner, K. The importance of the health motive in undertaking sports and recreational activities by Austrian school students compared to other motives. Zesz. Nauk. Coll. Witelona 2024, 50, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, Z.; Silva, J.; Ferreira, M. Knowledge and Practices of Teenagers about Health: Implications for the Lifestyle and Self Care. Esc. Anna Nery 2014, 18, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, M.; Dinh, A. Body Image: A Study Concerning Teenage Social Media Involvement and Body Satisfaction. J. Stud. Res. 2023, 11, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Dong Xie, H.; Yang, S.-Y. The Relationship between Physical Exercise and Subjective Well-Being in College Students: The Mediating Effect of Body Image and Self-Esteem. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 658935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubowska, H.; Byczkowska-Owczarek, D. Girls in Football, Boys in Dance. Stereotypization Processes in Socialization of Young Sportsmen and Sportswomen. Qual. Sociol. Rev. 2018, 14, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszewski, B. El Cuerpo Del Baile: The Kinetic and Social Fundaments of Tango. Body Soc. 2008, 14, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madejski, E.; Jaros, A.; Madejski, R. Attitudes of Secondary School Students towards Physical Culture, Physical Education Lessons and Exercises. Health Promot. Phys. Act. 2019, 7, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippot, A.; Dubois, V.; Grogna, D.; Robert, A.; Jonckheer, U.; Chakib, W.; Beine, A.; Bleyenheuft, Y.; De Volder, A.G. Impact of Physical Exercise on Depression and Anxiety in Adolescent Inpatients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 301, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sa-nguanmoo, P.; Chuatrakoon, B.; Parameyong, A.; Jaisamer, K.; Panyakum, M.; Suriyawong, W. Comparing the 6-minute Walk Test Performance and Estimated Maximal Oxygen Consumption Between Physically Active and Inactive Obese Young Adults. Phys. Act. Health 2024, 8, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

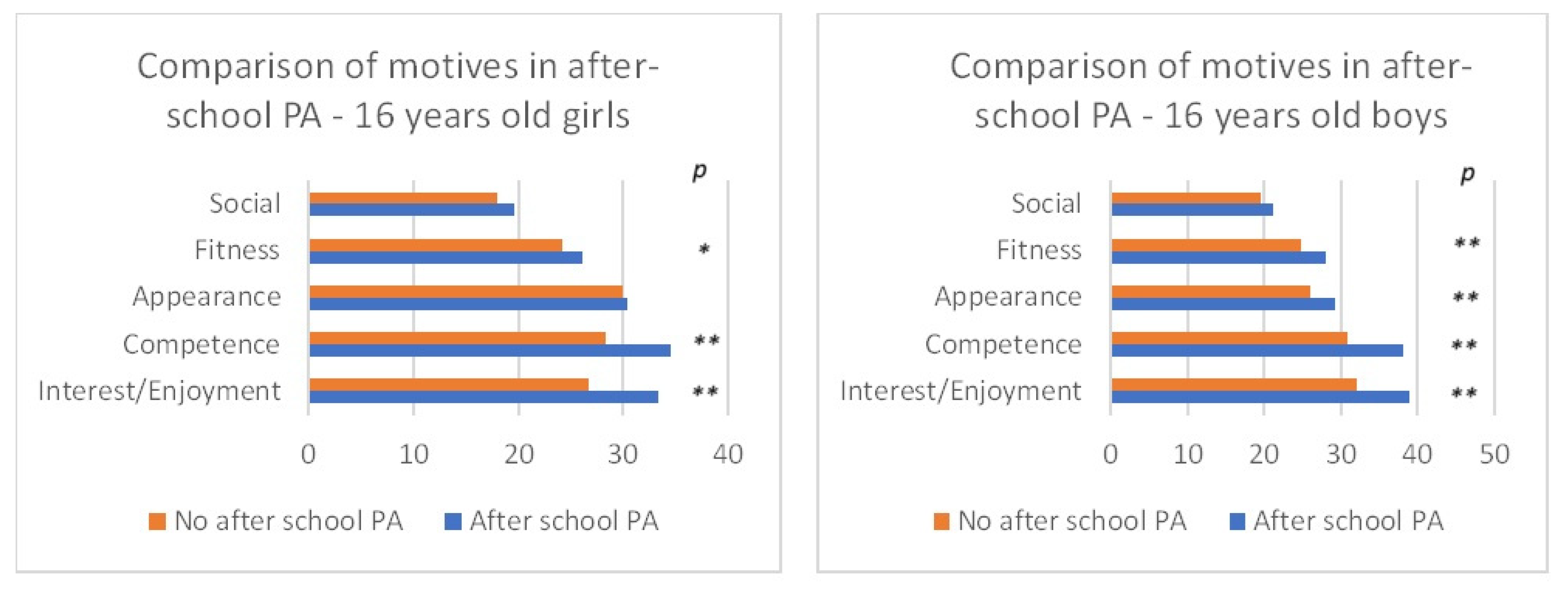

| Motives | Girls (n = 185) M ± SD | Boys (n = 170) M ± SD | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interest/Enjoyment | 30.6 ± 10.48 | 35.4 ± 9.21 | 0.01 |

| Competence | 30.9 ± 10.08 | 34.4 ± 8.82 | 0.02 |

| Appearance | 29.8 ± 8.85 | 27.5 ± 9.38 | 0.01 |

| Fitness | 25.3 ± 6.31 | 26.3 ± 5.43 | 0.21 |

| Social | 18.9 ± 7.38 | 20.3 ± 7.31 | 0.06 |

| Girls (n = 185) M ± SD | Boys (n =1 70) M ± SD | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TECHNICAL SKILLS | |||

| volleyball | 4.3 ± 1.44 | 4.3 ± 1.29 | 0.90 |

| basketball | 3.8 ± 1.36 | 4.0 ± 1.47 | 0.30 |

| football | 2.6 ± 1.69 | 4.2 ± 1.85 | 0.01 |

| handball | 3.1 ± 1.69 | 3.4 ± 1.52 | 0.07 |

| athletics | 3.7 ± 1.83 | 3.7 ± 1.71 | 0.91 |

| gymnastics | 3.7 ± 1.97 | 2.8 ± 1.56 | 0.01 |

| swimming | 4.8 ± 1.78 | 4.5 ± 1.78 | 0.06 |

| TACTICAL SKILLS | |||

| volleyball | 4.2 ± 1.72 | 4.3 ± 1.55 | 0.41 |

| basketball | 3.5 ± 1.50 | 3.9 ± 1.69 | 0.06 |

| football | 2.6 ± 1.70 | 4.4 ± 1.97 | 0.01 |

| handball | 3.1 ± 1.72 | 3.2 ± 1.79 | 0.58 |

| Girls | Boys | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additional After-School Sports Activity (n = 109) M ± SD | No Sport Activity After School (n = 76) M ± SD | p | Additional After-School Sports Activity (n = 82) M ± SD | No Sport Activity After School (n = 88) M ± SD | p | |

| Technical skills | 3.9 ± 0.97 | 3.4 ± 1.04 | 0.02 | 4.1 ± 0.98 | 3.6 ± 1.06 | 0.01 |

| Tactical skills | 3.4 ± 1.19 | 3.3 ± 1.11 | 0.51 | 4.2 ± 1.25 | 3.7 ± 1.27 | 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adamczak, D.; Bronikowski, M. Comparison of Motivation Types, Self-Assessment of Sport Skills, and Fitness Among Young Adolescents Regarding Additional Physical Activity. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7043. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15137043

Adamczak D, Bronikowski M. Comparison of Motivation Types, Self-Assessment of Sport Skills, and Fitness Among Young Adolescents Regarding Additional Physical Activity. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(13):7043. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15137043

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdamczak, Dagny, and Michał Bronikowski. 2025. "Comparison of Motivation Types, Self-Assessment of Sport Skills, and Fitness Among Young Adolescents Regarding Additional Physical Activity" Applied Sciences 15, no. 13: 7043. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15137043

APA StyleAdamczak, D., & Bronikowski, M. (2025). Comparison of Motivation Types, Self-Assessment of Sport Skills, and Fitness Among Young Adolescents Regarding Additional Physical Activity. Applied Sciences, 15(13), 7043. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15137043