Oral Health and Cognitive Decline: A Systematic Review of the Periodontitis–Alzheimer’s Connection

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Epidemiological Evidence Linking Periodontal Disease and Alzheimer’s Disease

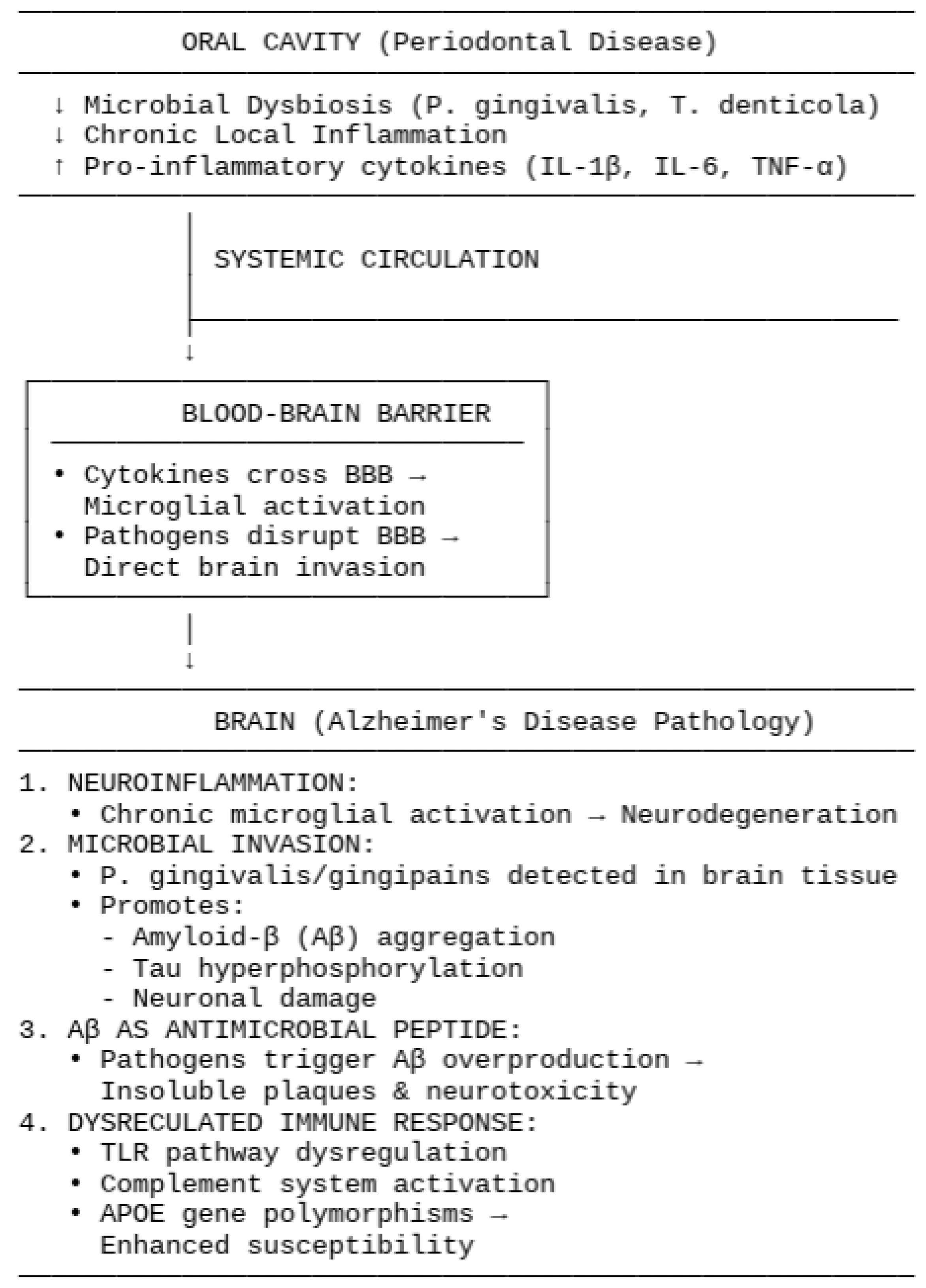

1.2. Pathophysiological Mechanisms Connecting Periodontal Disease to Alzheimer’s Disease

1.2.1. Systemic Inflammation and Neuroinflammation

1.2.2. Microbial Invasion and Direct Effects

1.2.3. Aβ as an Antimicrobial Peptide

1.2.4. Dysregulated Immune Responses

1.3. Enviromental Factors

1.4. Clinical Implications and Future Directions

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Search Processing

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

- Criteria: application in the present study;

- Population: human subjects;

- Intervention: evaluation of salivary biomarkers, blood biomarkers, periodontal therapy;

- Comparison: control group;

- Outcome: evaluation of the connection between periodontitis and the onset of Alzheimer’s disease;

- Study design: randomized controlled trial, observational study, cohort study, retrospective study.

2.4. Exclusion Criteria

2.5. Data Processing

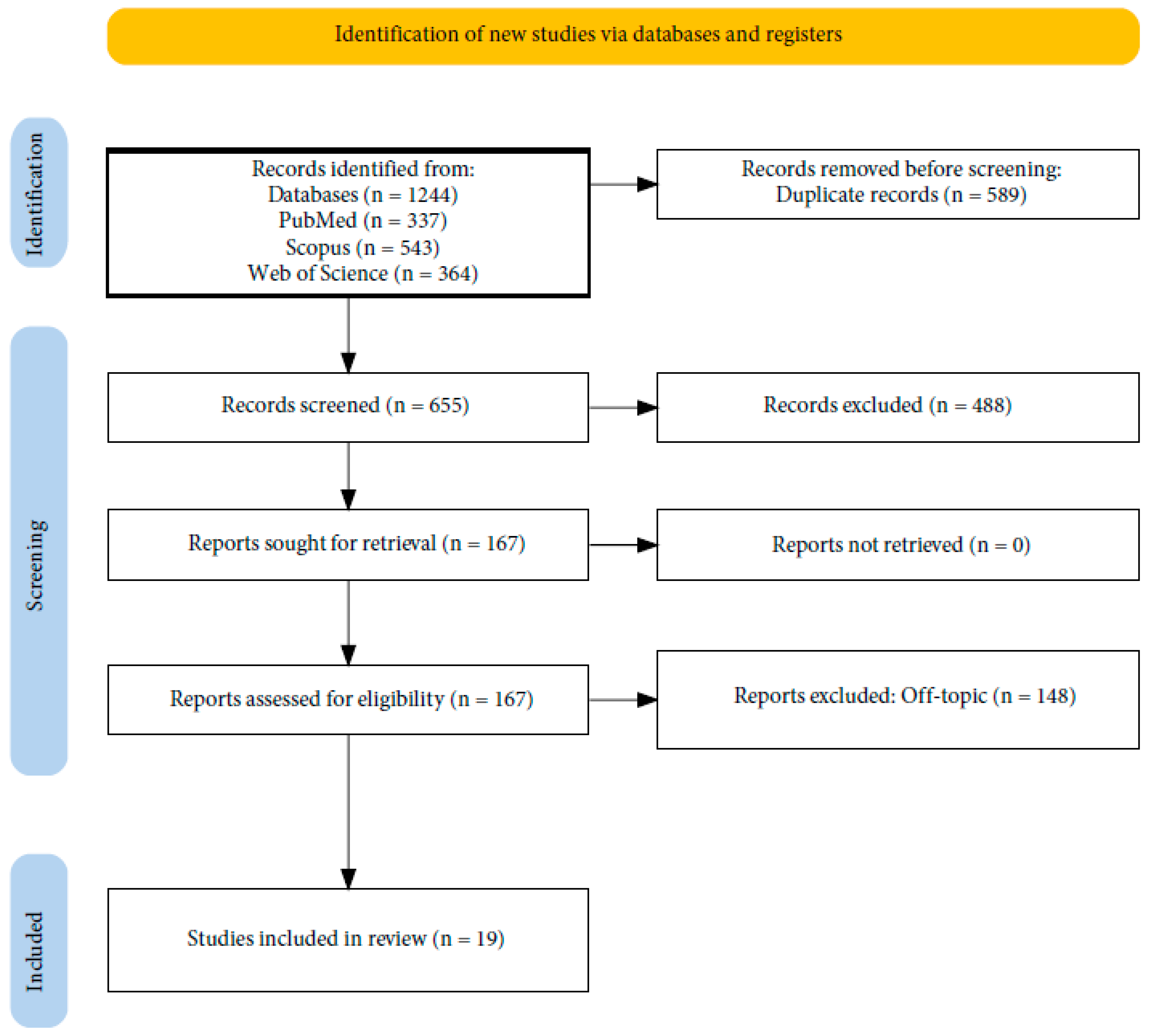

2.6. Article Identification Procedure

2.7. Study Evaluation

2.8. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Reviewed Studies

3.2. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias of Included Articles

4. Discussion

4.1. Diagnosis: Microbial and Systemic Markers of Cognitive Impairment

The Role of the Oral Microbiome as a Diagnostic Tool

4.2. Therapy: Periodontal Interventions and Cognitive Protection

4.3. Challenges and Future Directions

4.4. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Aβ | Amyloid-β |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| APOE | Apolipoprotein E |

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| CAL | Clinical Attachment Loss |

| CERAD | Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| DII | Dietary Inflammatory Index |

| DSST | Digit Symbol Substitution Test |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| GCF | Gingival crevicular fluid |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1β |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry/Mass Spectrometry |

| MMSE | Mini-Mental State Examination |

| MOCA | Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| NHANES | National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey |

| NHIRD | National Health Insurance Research Database |

| PD | Periodontal disease |

| PDT | Probing depth |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| PICO | Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RAVLT | Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test |

| TLR | Toll-like Receptor |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-α |

| VD | Vascular dementia |

References

- Genco, R.J.; Sanz, M. Clinical and Public Health Implications of Periodontal and Systemic Diseases: An Overview. Periodontology 2000 2020, 83, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eke, P.I.; Thornton-Evans, G.O.; Wei, L.; Borgnakke, W.S.; Dye, B.A.; Genco, R.J. Periodontitis in US Adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009–2014. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1939 2018, 149, 576–588.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, T.; Lim, S.S.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi, M.; Abbasifard, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; et al. Global Burden of 369 Diseases and Injuries in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990–2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frencken, J.E.; Sharma, P.; Stenhouse, L.; Green, D.; Laverty, D.; Dietrich, T. Global Epidemiology of Dental Caries and Severe Periodontitis—A Comprehensive Review. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2017, 44 (Suppl. S18), S94–S105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer’s Disease International. World Alzheimer Report 2023: Reducing Dementia Risk: Never Too Early, Never Too Late. 2023. Available online: https://www.alzint.org/resource/world-alzheimer-report-2023/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Global Status Report on the Public Health Response to Dementia. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240033245 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Alam, M.Z.; Alam, Q.; Kamal, M.A.; Abuzenadah, A.M.; Haque, A. A Possible Link of Gut Microbiota Alteration in Type 2 Diabetes and Alzheimer’s Disease Pathogenicity: An Update. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2014, 13, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tettevi, E.J.; Maina, M.; Simpong, D.L.; Osei-Atweneboana, M.Y.; Ocloo, A. A Review of African Medicinal Plants and Functional Foods for the Management of Alzheimer’s Disease-Related Phenotypes, Treatment of HSV-1 Infection and/or Improvement of Gut Microbiota. J. Evid.-Based Integr. Med. 2022, 27, 2515690X221114657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Ma, K.; Wen, J.; Wang, G.; Zhang, C.; Li, Q.; Bao, X.; Wang, H. A Review of the Brain-Gut-Microbiome Axis and the Potential Role of Microbiota in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2020, 73, 849–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salminen, A. Activation of Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR) in Alzheimer’s Disease: Role of Tryptophan Metabolites Generated by Gut Host-Microbiota. J. Mol. Med. Berl. Ger. 2023, 101, 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Jiang, Q.; McDermott, J.; Han, J.-D.J. Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease: Comparison and Associations from Molecular to System Level. Aging Cell 2018, 17, e12802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedr, E.M.; Omeran, N.; Karam-Allah Ramadan, H.; Ahmed, G.K.; Abdelwarith, A.M. Alteration of Gut Microbiota in Alzheimer’s Disease and Their Relation to the Cognitive Impairment. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2022, 88, 1103–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Li, D.; Shi, J. Alterations of Spatial Memory and Gut Microbiota Composition in Alzheimer’s Disease Triple-Transgenic Mice at 3, 6, and 9 Months of Age. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen. 2023, 38, 15333175231174193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MahmoudianDehkordi, S.; Arnold, M.; Nho, K.; Ahmad, S.; Jia, W.; Xie, G.; Louie, G.; Kueider-Paisley, A.; Moseley, M.A.; Thompson, J.W.; et al. Altered Bile Acid Profile Associates with Cognitive Impairment in Alzheimer’s Disease-An Emerging Role for Gut Microbiome. Alzheimers Dement. J. Alzheimers Assoc. 2019, 15, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Ma, X.; Wu, J.; Xiao, Z.; Wu, W.; Ding, S.; Zheng, L.; Liang, X.; Luo, J.; Ding, D.; et al. Altered Gut Microbiota and Its Clinical Relevance in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease: Shanghai Aging Study and Shanghai Memory Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wu, L.; Peng, G.; Han, Y.; Tang, R.; Ge, J.; Zhang, L.; Jia, L.; Yue, S.; Zhou, K.; et al. Altered Microbiomes Distinguish Alzheimer’s Disease from Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment and Health in a Chinese Cohort. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2019, 80, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzolla, A.P.; Campisi, G.; Lacaita, G.M.; Cuccia, M.A.; Ripa, A.; Testa, N.F.; Ciavarella, D.; Lo Muzio, L. Changes in Pharyngeal Aerobic Microflora in Oral Breathers after Palatal Rapid Expansion. BMC Oral Health 2006, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tepedino, M.; Iancu-Potrubacz, M.; Ciavarella, D.; Masedu, F.; Marchione, L.; Chimenti, C. Expansion of Permanent First Molars with Rapid Maxillary Expansion Appliance Anchored on Primary Second Molars. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2018, 10, e241–e247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troiano, G.; Dioguardi, M.; Cocco, A.; Laino, L.; Cervino, G.; Cicciu, M.; Ciavarella, D.; Lo Muzio, L. Conservative vs Radical Approach for the Treatment of Solid/Multicystic Ameloblastoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Last Decade. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2017, 15, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassano, M.; Russo, G.; Granieri, C.; Ciavarella, D. Modification of Growth, Immunologic and Feeding Parameters in Children with OSAS after Adenotonsillectomy. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2018, 38, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troiano, G.; Dioguardi, M.; Cocco, A.; Zhurakivska, K.; Ciavarella, D.; Muzio, L.L. Increase in [Corrected] the Glyde Path Diameter Improves the Centering Ability of F6 Skytaper. Eur. J. Dent. 2018, 12, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatucci, A.; Raffaeli, F.; Mastrovincenzo, M.; Luchetta, A.; Giannone, A.; Ciavarella, D. Breathing Pattern and Head Posture: Changes in Craniocervical Angles. Minerva Stomatol. 2015, 64, 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ciavarella, D.; Monsurrò, A.; Padricelli, G.; Battista, G.; Laino, L.; Perillo, L. Unilateral Posterior Crossbite in Adolescents: Surface Electromyographic Evaluation. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2012, 13, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cazzolla, A.P.; Zhurakivska, K.; Ciavarella, D.; Lacaita, M.G.; Favia, G.; Testa, N.F.; Marzo, G.; La Carbonara, V.; Troiano, G.; Lo Muzio, L. Primary Hyperoxaluria: Orthodontic Management in a Pediatric Patient: A Case Report. Spec. Care Dent. 2018, 38, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciavarella, D.; Mastrovincenzo, M.; D’Onofrio, V.; Chimenti, C.; Parziale, V.; Barbato, E.; Lo Muzio, L. Saliva Analysis by Surface-Enhanced Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (SELDI-TOF-MS) in Orthodontic Treatment: First Pilot Study. Prog. Orthod. 2011, 12, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballini, A.; Cantore, S.; Signorini, L.; Saini, R.; Scacco, S.; Gnoni, A.; Inchingolo, A.D.; De Vito, D.; Santacroce, L.; Inchingolo, F.; et al. Efficacy of Sea Salt-Based Mouthwash and Xylitol in Improving Oral Hygiene among Adolescent Population: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 18, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carranza-Naval, M.J.; Vargas-Soria, M.; Hierro-Bujalance, C.; Baena-Nieto, G.; Garcia-Alloza, M.; Infante-Garcia, C.; Del Marco, A. Alzheimer’s Disease and Diabetes: Role of Diet, Microbiota and Inflammation in Preclinical Models. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doulberis, M.; Kotronis, G.; Gialamprinou, D.; Polyzos, S.A.; Papaefthymiou, A.; Katsinelos, P.; Kountouras, J. Alzheimer’s Disease and Gastrointestinal Microbiota; Impact of Helicobacter Pylori Infection Involvement. Int. J. Neurosci. 2021, 131, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wang, T.; Jin, F. Alzheimer’s Disease and Gut Microbiota. Sci. China Life Sci. 2016, 59, 1006–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, C.; Santangelo, R. Alzheimer’s Disease and Gut Microbiota Modifications: The Long Way between Preclinical Studies and Clinical Evidence. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 129, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrona Cardoza, P.; Spillane, M.B.; Morales Marroquin, E. Alzheimer’s Disease and Gut Microbiota: Does Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO) Play a Role? Nutr. Rev. 2022, 80, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulin, T.d.E.S.; Estadella, D. Alzheimer’s Disease And Its Relationship with The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Arq. Gastroenterol. 2023, 60, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, M.; Knorr, D.A.; Haptonstall, K.M. Alzheimer’s Disease and Symbiotic Microbiota: An Evolutionary Medicine Perspective. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2019, 1449, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roe, K. An Alternative Explanation for Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease Initiation from Specific Antibiotics, Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis and Neurotoxins. Neurochem. Res. 2022, 47, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Huang, J.; Zhao, D.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, L.; Wu, B.; et al. Anti-Alzheimers Molecular Mechanism of Icariin: Insights from Gut Microbiota, Metabolomics, and Network Pharmacology. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelucci, F.; Cechova, K.; Amlerova, J.; Hort, J. Antibiotics, Gut Microbiota, and Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Neuroinflammation 2019, 16, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Termine, N.; Panzarella, V.; Ciavarella, D.; Lo Muzio, L.; D’Angelo, M.; Sardella, A.; Compilato, D.; Campisi, G. Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Dentistry and Oral Surgery: Use and Misuse. Int. Dent. J. 2009, 59, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Compilato, D.; Cirillo, N.; Termine, N.; Kerr, A.R.; Paderni, C.; Ciavarella, D.; Campisi, G. Long-Standing Oral Ulcers: Proposal for a New “S-C-D Classification System”. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2009, 38, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo Russo, L.; Ciavarella, D.; Salamini, A.; Guida, L. Alignment of Intraoral Scans and Registration of Maxillo-Mandibular Relationships for the Edentulous Maxillary Arch. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2019, 121, 737–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciavarella, D.; Parziale, V.; Mastrovincenzo, M.; Palazzo, A.; Sabatucci, A.; Suriano, M.M.; Bossù, M.; Cazzolla, A.P.; Lo Muzio, L.; Chimenti, C. Condylar Position Indicator and T-Scan System II in Clinical Evaluation of Temporomandibular Intracapsular Disease. J. Cranio-Maxillo-fac. Surg. 2012, 40, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dioguardi, M.; Di Gioia, G.; Illuzzi, G.; Ciavarella, D.; Laneve, E.; Troiano, G.; Lo Muzio, L. Passive Ultrasonic Irrigation Efficacy in the Vapor Lock Removal: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. World J. 2019, 2019, 6765349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianci, C.; Pappalettera, G.; Renna, G.; Casavola, C.; Laurenziello, M.; Battista, G.; Pappalettere, C.; Ciavarella, D. Mechanical Behavior of PET-G Tooth Aligners Under Cyclic Loading. Front. Mater. 2020, 7, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciavarella, D.; Tepedino, M.; Gallo, C.; Montaruli, G.; Zhurakivska, K.; Coppola, L.; Troiano, G.; Chimenti, C.; Laurenziello, M.; Lo Russo, L. Post-Orthodontic Position of Lower Incisors and Gingival Recession: A Retrospective Study. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2017, 9, e1425–e1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo Muzio, L.; Lo Russo, L.; Falaschini, S.; Ciavarella, D.; Pentenero, M.; Arduino, P.; Favia, G.; Maiorano, E.; Rubini, C.; Pieramici, T.; et al. Beta- and Gamma-Catenin Expression in Oral Dysplasia. Oral Oncol. 2009, 45, 501–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo Muzio, L.; Santarelli, A.; Panzarella, V.; Campisi, G.; Carella, M.; Ciavarella, D.; Di Cosola, M.; Giannone, N.; Bascones, A. Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Biological Markers: An Update on the Molecules Mainly Involved in Oral Carcinogenesis. Minerva Stomatol. 2007, 56, 341–347. [Google Scholar]

- Laino, L.; Troiano, G.; Giannatempo, G.; Graziani, U.; Ciavarella, D.; Dioguardi, M.; Lo Muzio, L.; Lauritano, F.; Cicciù, M. Sinus Lift Augmentation by Using Calcium Sulphate. A Retrospective 12 Months Radiographic Evaluation Over 25 Treated Italian Patients. Open Dent. J. 2015, 9, 414–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipalma, G.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Inchingolo, A.M.; Piras, F.; Carpentiere, V.; Garofoli, G.; Azzollini, D.; Campanelli, M.; Paduanelli, G.; Palermo, A.; et al. Artificial Intelligence and Its Clinical Applications in Orthodontics: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcangi, G.; Patano, A.; Palmieri, G.; Riccaldo, L.; Pezzolla, C.; Mancini, A.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Di Venere, D.; Piras, F.; Inchingolo, F.; et al. Oral Piercing: A Pretty Risk—A Scoping Review of Local and Systemic Complications of This Current Widespread Fashion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laforgia, A.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Piras, F.; Colonna, V.; Giorgio, R.V.; Carone, C.; Rapone, B.; Malcangi, G.; Inchingolo, A.M.; Inchingolo, F.; et al. Therapeutic Strategies and Genetic Implications for Periodontal Disease Management: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceci, S.; Berate, P.; Candrea, S.; Babtan, A.-M.; Azzollini, D.; Piras, F.; Curatoli, L.; Corriero, A.; Patano, A.; Valente, F.; et al. The Oral and Gut Microbiota: Beyond a Short Communication. Balneo PRM Res. J. 2021, 12, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguayo, S.; Schuh, C.M.A.P.; Vicente, B.; Aguayo, L.G. Association between Alzheimer’s Disease and Oral and Gut Microbiota: Are Pore Forming Proteins the Missing Link? J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018, 65, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanapaisan, P.; Chuansangeam, M.; Nopnipa, S.; Mathuranyanon, R.; Nonthabenjawan, N.; Ngamsombat, C.; Thientunyakit, T.; Muangpaisan, W. Association between Gut Microbiota with Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease in a Thai Population. Neurodegener. Dis. 2022, 22, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Dashper, S.G.; Zhao, R. Association Between Oral Bacteria and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2023, 91, 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cattaneo, A.; Cattane, N.; Galluzzi, S.; Provasi, S.; Lopizzo, N.; Festari, C.; Ferrari, C.; Guerra, U.P.; Paghera, B.; Muscio, C.; et al. Association of Brain Amyloidosis with Pro-Inflammatory Gut Bacterial Taxa and Peripheral Inflammation Markers in Cognitively Impaired Elderly. Neurobiol. Aging 2017, 49, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, Z.; Yang, R.; Wang, W.; Qi, L.; Huang, T. Associations between Gut Microbiota and Alzheimer’s Disease, Major Depressive Disorder, and Schizophrenia. J. Neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, L.; Ji, H.-F. Associations Between Gut Microbiota and Alzheimer’s Disease: Current Evidences and Future Therapeutic and Diagnostic Perspectives. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2019, 68, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, Z.-H.; Liu, X.; Alam, A.M.; Haran, J.P.; McCormick, B.A.; Shu, X.; Wang, X.; Ye, K. Bacteroides Fragilis in the Gut Microbiomes of Alzheimer’s Disease Activates Microglia and Triggers Pathogenesis in Neuronal C/EBPβ Transgenic Mice. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasén, C.; Beauchamp, L.C.; Vincentini, J.; Li, S.; LeServe, D.S.; Gauthier, C.; Lopes, J.R.; Moreira, T.G.; Ekwudo, M.N.; Yin, Z.; et al. Bacteroidota Inhibit Microglia Clearance of Amyloid-Beta and Promote Plaque Deposition in Alzheimer’s Disease Mouse Models. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.-Z.; Li, X.-Y.; Wang, S.; Shen, L.; Ji, H.-F. Bidirectional Interactions between Curcumin and Gut Microbiota in Transgenic Mice with Alzheimer’s Disease. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 3507–3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Cao, Z.; Du, Y.; Xu, G.; Wang, J.; Zheng, J.; Lu, Y. Bidirectional Two-Sample, Two-Step Mendelian Randomisation Study Reveals Mediating Role of Gut Microbiota Between Vitamin B Supplementation and Alzheimer’s Disease. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Guo, M.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, G.; Chen, W. Bifidobacterium Breve Intervention Combined with Environmental Enrichment Alleviates Cognitive Impairment by Regulating the Gut Microbiota and Microbial Metabolites in Alzheimer’s Disease Mice. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1013664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Wu, X.; Mei, J.; Zheng, G. Brain Targeted Peptide-Functionalized Chitosan Nanoparticles for Resveratrol Delivery: Impact on Insulin Resistance and Gut Microbiota in Obesity-Related Alzheimer’s Disease. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 310, 120714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momen, Y.S.; Mishra, J.; Kumar, N. Brain-Gut and Microbiota-Gut-Brain Communication in Type-2 Diabetes Linked Alzheimer’s Disease. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayan, E.; DeMirci, H.; Serdar, M.A.; Palermo, F.; Baykal, A.T. Bridging the Gap between Gut Microbiota and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Metaproteomic Approach for Biomarker Discovery in Transgenic Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, M.; An, L.; Dong, L.; Zhu, R.; Hao, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y. Causal Associations Between Gut Microbiota, Gut Microbiota-Derived Metabolites, and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Multivariable Mendelian Randomization Study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2024, 100, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Sun, M.; Xu, J.; Xu, C.; Kuang, H.; Xu, L. Chiral Nanoparticle-Remodeled Gut Microbiota Alleviates Neurodegeneration via the Gut-Brain Axis. Nat. Aging 2023, 3, 1415–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, C.; Yang, K.; He, B.; Du, W.; Cai, Y.; Han, Y. Combination of Gut Microbiota and Plasma Amyloid-β as a Potential Index for Identifying Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease: A Cross-Sectional Analysis from the SILCODE Study. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2022, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Zhu, H.; Li, X.; Shi, W.; Guo, Y.; Du, X.; Zhang, L.; Su, L.; Qin, C. Comparative Metagenomics and Metabolomes Reveals Abnormal Metabolism Activity Is Associated with Gut Microbiota in Alzheimer’s Disease Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostancıklıoğlu, M. Connectivity Between Gut Microbiota and Terminal Awakenings in Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2023, 20, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stasio, D.; Romano, A.; Paparella, R.S.; Gentile, C.; Serpico, R.; Minervini, G.; Candotto, V.; Laino, L. How Social Media Meet Patients Questions: YouTube Review for Mouth Sores in Children. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2018, 32, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Di Stasio, D.; Lauritano, D.; Romano, A.; Salerno, C.; Minervini, G.; Minervini, G.; Gentile, E.; Serpico, R.; Lucchese, A. In vivo characterization of oral pemphigus vulgaris by optical coherence tomography. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2015, 29, 39–41. [Google Scholar]

- Di Stasio, D.; Lauritano, D.; Gritti, P.; Migliozzi, R.; Maio, C.; Minervini, G.; Petruzzi, M.; Serpico, R.; Candotto, V.; Lucchese, A. Psychiatric Disorders in Oral Lichen Planus: A Preliminary Case Control Study. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2018, 32, 97–100. [Google Scholar]

- Minervini, G.; Nucci, L.; Lanza, A.; Femiano, F.; Contaldo, M.; Grassia, V. Temporomandibular Disc Displacement with Reduction Treated with Anterior Repositioning Splint: A 2-Year Clinical and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) Follow-Up. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2020, 34, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Minervini, G.; Romano, A.; Petruzzi, M.; Maio, C.; Serpico, R.; Di Stasio, D.; Lucchese, A. Oral-Facial-Digital Syndrome (OFD): 31-Year Follow-up Management and Monitoring. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2018, 32, 127–130. [Google Scholar]

- Minervini, G.; Romano, A.; Petruzzi, M.; Maio, C.; Serpico, R.; Lucchese, A.; Candotto, V.; Di Stasio, D. Telescopic Overdenture on Natural Teeth: Prosthetic Rehabilitation on (OFD) Syndromic Patient and a Review on Available Literature. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2018, 32, 131–134. [Google Scholar]

- Lucchese, A.; Dolci, A.; Minervini, G.; Salerno, C.; DI Stasio, D.; Minervini, G.; Laino, L.; Silvestre, F.; Serpico, R. Vulvovaginal Gingival Lichen Planus: Report of Two Cases and Review of Literature. ORAL Implantol. 2016, 9, 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Di Stasio, D.; Romano, A.; Gentile, C.; Maio, C.; Lucchese, A.; Serpico, R.; Paparella, R.; Minervini, G.; Candotto, V.; Laino, L. Systemic and Topical Photodynamic Therapy (PDT) on Oral Mucosa Lesions: An Overview. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2018, 32, 123–126. [Google Scholar]

- Di Stasio, D.; Lauritano, D.; Minervini, G.; Paparella, R.S.; Petruzzi, M.; Romano, A.; Candotto, V.; Lucchese, A. Management of Denture Stomatitis: A Narrative Review. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2018, 32, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- van Olst, L.; Roks, S.J.M.; Kamermans, A.; Verhaar, B.J.H.; van der Geest, A.M.; Muller, M.; van der Flier, W.M.; de Vries, H.E. Contribution of Gut Microbiota to Immunological Changes in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 683068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuźniar, J.; Kozubek, P.; Czaja, M.; Leszek, J. Correlation Between Alzheimer’s Disease and Gastrointestinal Tract Disorders. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-X.; Zeng, M.-X.; Cai, D.; Zhou, H.-H.; Wang, Y.-J.; Liu, Z. Correlation Between APOE4 Gene and Gut Microbiota in Alzheimer’s Disease. Benef. Microbes 2023, 14, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, U.; Arshad, M.S.; Sameen, A.; Oh, D.-H. Crosstalk Between Gut and Brain in Alzheimer’s Disease: The Role of Gut Microbiota Modulation Strategies. Nutrients 2021, 13, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junges, V.M.; Closs, V.E.; Nogueira, G.M.; Gottlieb, M.G.V. Crosstalk Between Gut Microbiota and Central Nervous System: A Focus on Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2018, 15, 1179–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, D.-O.; Holtzman, D.M. Current Understanding of the Alzheimer’s Disease-Associated Microbiome and Therapeutic Strategies. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.-H.; Lin, C.-H.; Lane, H.-Y. D-Glutamate and Gut Microbiota in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, B.; Dong, X.; Cai, W.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, H. Deciphering the Intricate Linkage Between the Gut Microbiota and Alzheimer’s Disease: Elucidating Mechanistic Pathways Promising Therapeutic Strategies. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2024, 30, e14704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairley, A.; Stewart, C.J.; Cassidy, A.; Woodside, J.V.; McEvoy, C.T. Diet Patterns, the Gut Microbiome, and Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2022, 88, 933–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kincaid, H.J.; Nagpal, R.; Yadav, H. Diet-Microbiota-Brain Axis in Alzheimer’s Disease. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2021, 77 (Suppl. S2), 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambini, F.; Memè, L.; Pellecchia, M.; Sabatucci, A.; Selvaggio, R. Comparative Analysis of Deformation of Two Implant/Abutment Connection Systems During Implant Insertion. An in Vitro Study. Minerva Stomatol. 2005, 54, 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgini, E.; Sabbatini, S.; Conti, C.; Rubini, C.; Rocchetti, R.; Fioroni, M.; Memè, L.; Orilisi, G. Fourier Transform Infrared Imaging Analysis of Dental Pulp Inflammatory Diseases. Oral Dis. 2017, 23, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambini, F.; Giannetti, L.; Memè, L.; Pellecchia, M.; Selvaggio, R. Comparative Analysis of Direct and Indirect Implant Impression Techniques an in Vitro Study. An in Vitro Study. Minerva Stomatol. 2005, 54, 395–402. [Google Scholar]

- Bambini, F.; Santarelli, A.; Putignano, A.; Procaccini, M.; Orsini, G.; Memè, L.; Sartini, D.; Emanuelli, M.; Lo Muzio, L. Use of Supercharged Cover Screw as Static Magnetic Field Generator for Bone Healing, 1st Part: In Vitro Enhancement of Osteoblast-like Cell Differentiation. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2017, 31, 215–220. [Google Scholar]

- Memè, L.; Notarstefano, V.; Sampalmieri, F.; Orilisi, G.; Quinzi, V. ATR-FTIR Analysis of Orthodontic Invisalign® Aligners Subjected to Various In Vitro Aging Treatments. Materials 2021, 14, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bambini, F.; Pellecchia, M.; Memè, L.; Santarelli, A.; Emanuelli, M.; Procaccini, M.; Muzio, L.L. Anti-Inflammatory Cytokines in Peri-Implant Soft Tissues: A Preliminary Study on Humans Using CDNA Microarray Technology. Eur. J. Inflamm. 2007, 5, 121–127. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1721727X0700500302 (accessed on 24 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Bambini, F.; Greci, L.; Memè, L.; Santarelli, A.; Carinci, F.; Pezzetti, F.; Procaccini, M.; Lo Muzio, L. Raloxifene Covalently Bonded to Titanium Implants by Interfacing with (3-Aminopropyl)-Triethoxysilane Affects Osteoblast-like Cell Gene Expression. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2006, 19, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambini, F.; De Stefano, C.A.; Giannetti, L.; Memè, L.; Pellecchia, M. Influence of biphosphonates on the integration process of endosseous implants evaluated using single photon emission computerized tomography (SPECT). Minerva Stomatol. 2003, 52, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tosco, V.; Monterubbianesi, R.; Aranguren, J.; Memè, L.; Putignano, A.; Orsini, G. Evaluation of the Efficacy of Different Irrigation Systems on the Removal of Root Canal Smear Layer: A Scanning Electron Microscopic Study. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, A.; Memè, L.; Strappa, E.M.; Martini, E.; Bambini, F. Modified Periosteal Inhibition (MPI) Technique for Extraction Sockets: A Case Series Report. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, R.; Memè, L.; Strappa, E.M.; Bambini, F. Restoration of Severe Bone and Soft Tissue Atrophy by Means of a Xenogenic Bone Sheet (Flex Cortical Sheet): A Case Report. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 692. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/13/2/692 (accessed on 24 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Meme’, L.; Gallusi, G.; Coli, G.; Strappa, E.; Bambini, F.; Sampalmieri, F. Photobiomodulation to Reduce Orthodontic Treatment Time in Adults: A Historical Prospective Study. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11532. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/12/22/11532 (accessed on 24 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Xie, L.; Schröder, J.; Schuster, I.S.; Nakai, M.; Sun, G.; Sun, Y.B.Y.; Mariño, E.; Degli-Esposti, M.A.; Marques, F.Z.; et al. Dietary Fiber and Microbiota Metabolite Receptors Enhance Cognition and Alleviate Disease in the 5xFAD Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Neurosci. 2023, 43, 6460–6475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Yang, S.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Gu, Z.; Jiang, Z. Dietary Neoagarotetraose Extends Lifespan and Impedes Brain Aging in Mice via Regulation of Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. J. Adv. Res. 2023, 52, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhao, D.; Zhou, G.; Li, C. Dietary Pattern, Gut Microbiota, and Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 12800–12809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Lim, Y.-Y.; He, Z.; Wong, W.-T.; Lai, W.-F. Dietary Phytochemicals That Influence Gut Microbiota: Roles and Actions as Anti-Alzheimer Agents. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 5140–5166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, J.; Ding, D.; Zhu, H.; Wang, R.; Su, F.; Wu, W.; Xiao, Z.; Liang, X.; Zhao, Q.; Hong, Z.; et al. Disturbed Microbial Ecology in Alzheimer’s Disease: Evidence from the Gut Microbiota and Fecal Metabolome. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.K.; Singh, T.G.; Garg, N.; Dhiman, S.; Gupta, S.; Rahman, M.H.; Najda, A.; Walasek-Janusz, M.; Kamel, M.; Albadrani, G.M.; et al. Dysbiosis and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Role for Chronic Stress? Biomolecules 2021, 11, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janeiro, M.H.; Ramírez, M.J.; Solas, M. Dysbiosis and Alzheimer’s Disease: Cause or Treatment Opportunity? Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2022, 42, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilmore, A.H.; Martino, C.; Neth, B.J.; West, K.A.; Zemlin, J.; Rahman, G.; Panitchpakdi, M.; Meehan, M.J.; Weldon, K.C.; Blach, C.; et al. Effects of a Ketogenic and Low-Fat Diet on the Human Metabolome, Microbiome, and Foodome in Adults at Risk for Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Dement. J. Alzheimers Assoc. 2023, 19, 4805–4816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, Z.; Tian, H.; Wang, S.; Yang, J.; Ren, J. Electroacupuncture Could Balance the Gut Microbiota and Improve the Learning and Memory Abilities of Alzheimer’s Disease Animal Model. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0259530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, D.; Ali, S.A.; Singh, R.K. Emerging Role of Gut Microbiota in Modulation of Neuroinflammation and Neurodegeneration with Emphasis on Alzheimer’s Disease. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 106, 110112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santacroce, L.; Di Cosola, M.; Bottalico, L.; Topi, S.; Charitos, I.A.; Ballini, A.; Inchingolo, F.; Cazzolla, A.P.; Dipalma, G. Focus on HPV Infection and the Molecular Mechanisms of Oral Carcinogenesis. Viruses 2021, 13, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekchand Dasriya, V.; Samtiya, M.; Dhewa, T.; Puniya, M.; Kumar, S.; Ranveer, S.; Chaudhary, V.; Vij, S.; Behare, P.; Singh, N.; et al. Etiology and Management of Alzheimer’s Disease: Potential Role of Gut Microbiota Modulation with Probiotics Supplementation. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menden, A.; Hall, D.; Hahn-Townsend, C.; Broedlow, C.A.; Joshi, U.; Pearson, A.; Crawford, F.; Evans, J.E.; Klatt, N.; Crynen, S.; et al. Exogenous Lipase Administration Alters Gut Microbiota Composition and Ameliorates Alzheimer’s Disease-like Pathology in APP/PS1 Mice. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakashima, M.; Suga, N.; Fukumoto, A.; Yoshikawa, S.; Matsuda, S. Exosomes, Endosomes, and Caveolae as Encouraging Targets with Favorable Gut Microbiota for the Innovative Treatment of Alzheimer’s Diseases. Discov. Med. 2024, 36, 2132–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubeda, C.; Vázquez-Carretero, M.D.; Luque-Tirado, A.; Ríos-Reina, R.; Rubio-Sánchez, R.; Franco-Macías, E.; García-Miranda, P.; Calonge, M.L.; Peral, M.J. Fecal Volatile Organic Compounds and Microbiota Associated with the Progression of Cognitive Impairment in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Kim, T.; Kang, H. Forced Treadmill Running Modifies Gut Microbiota with Alleviations of Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology in 3xTg-AD Mice. Physiol. Behav. 2023, 264, 114145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashiro, K.; Takabayashi, K.; Kamagata, K.; Nishimoto, Y.; Togashi, Y.; Yamauchi, Y.; Ogaki, K.; Li, Y.; Hatano, T.; Motoi, Y.; et al. Free Water in Gray Matter Linked to Gut Microbiota Changes with Decreased Butyrate Producers in Alzheimer’s Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment. Neurobiol. Dis. 2024, 193, 106464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.; Mook-Jung, I. Functional Effects of Gut Microbiota-Derived Metabolites in Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2023, 81, 102730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cammann, D.; Lu, Y.; Cummings, M.J.; Zhang, M.L.; Cue, J.M.; Do, J.; Ebersole, J.; Chen, X.; Oh, E.C.; Cummings, J.L.; et al. Genetic Correlations between Alzheimer’s Disease and Gut Microbiome Genera. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, Q.; Zhu, J.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, T.; Song, J. GPR40 Agonist Ameliorate Pathological Neuroinflammation of Alzheimer’s Disease via the Modulation of Gut Microbiota and Immune System, a Mini-Review. Neurotox. Res. 2021, 39, 2175–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peddinti, V.; Avaghade, M.M.; Suthar, S.U.; Rout, B.; Gomte, S.S.; Agnihotri, T.G.; Jain, A. Gut Instincts: Unveiling the Connection between Gut Microbiota and Alzheimer’s Disease. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2024, 60, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritas, S.K.; Saggini, A.; Varvara, G.; Murmura, G.; Caraffa, A.; Antinolfi, P.; Toniato, E.; Pantalone, A.; Neri, G.; Frydas, S.; et al. Mast Cell Involvement in Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2013, 27, 655–660. [Google Scholar]

- Frydas, S.; Varvara, G.; Murmura, G.; Saggini, A.; Caraffa, A.; Antinolfi, P.; Tetè, S.; Tripodi, D.; Conti, F.; Cianchetti, E.; et al. Impact of Capsaicin on Mast Cell Inflammation. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2013, 26, 597–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traini, T.; Pettinicchio, M.; Murmura, G.; Varvara, G.; Di Lullo, N.; Sinjari, B.; Caputi, S. Esthetic Outcome of an Immediately Placed Maxillary Anterior Single-Tooth Implant Restored with a Custom-Made Zirconia-Ceramic Abutment and Crown: A Staged Treatment. Quintessence Int. Berl. Ger. 1985 2011, 42, 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Conti, P.; Varvara, G.; Murmura, G.; Tete, S.; Sabatino, G.; Saggini, A.; Rosati, M.; Toniato, E.; Caraffa, A.; Antinolfi, P.; et al. Comparison of Beneficial Actions of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs to Flavonoids. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost Agents 2013, 27, 1–7. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23489682/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Perinetti, G.; Caputi, S.; Varvara, G. Risk/Prevention Indicators for the Prevalence of Dental Caries in Schoolchildren: Results from the Italian OHSAR Survey. Caries Res. 2005, 39, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoletti, M.; Neri, G.; Maccauro, G.; Tripodi, D.; Varvara, G.; Saggini, A.; Potalivo, G.; Castellani, M.L.; Fulcheri, M.; Rosati, M.; et al. Impact of Neuropeptide Substance P an Inflammatory Compound on Arachidonic Acid Compound Generation. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2012, 25, 849–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, S.; Mancini, L.; Torge, D.; Cristiano, L.; Mattei, A.; Varvara, G.; Macchiarelli, G.; Marchetti, E.; Bernardi, S. Bio-Morphological Reaction of Human Periodontal Ligament Fibroblasts to Different Types of Dentinal Derivates: In Vitro Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, Y.; Sabatino, G.; Maccauro, G.; Varvara, G.; Murmura, G.; Saggini, A.; Rosati, M.; Conti, F.; Cianchetti, E.; Caraffa, A.; et al. IL-36 Receptor Antagonist with Special Emphasis on IL-38. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2013, 26, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varvara, G.; Sinjari, B.; Caputi, S.; Scarano, A.; Piattelli, M. The Relationship Between Time of Retightening and Preload Loss of Abutment Screws for Two Different Implant Designs: An In Vitro Study. J. Oral Implantol. 2020, 46, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizzicannella, J.; Pierdomenico, S.D.; Piattelli, A.; Varvara, G.; Fonticoli, L.; Trubiani, O.; Diomede, F. 3D Human Periodontal Stem Cells and Endothelial Cells Promote Bone Development in Bovine Pericardium-Based Tissue Biomaterial. Materials 2019, 12, 2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, B.; Biswas, P.; Gulati, M.; Rani, P.; Gupta, R. Gut Microbiome and Alzheimer’s Disease: What We Know and What Remains to Be Explored. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 102, 102570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreiro, A.L.; Choi, J.; Ryou, J.; Newcomer, E.P.; Thompson, R.; Bollinger, R.M.; Hall-Moore, C.; Ndao, I.M.; Sax, L.; Benzinger, T.L.S.; et al. Gut Microbiome Composition May Be an Indicator of Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 2023, 15, eabo2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jemimah, S.; Chabib, C.M.M.; Hadjileontiadis, L.; AlShehhi, A. Gut Microbiome Dysbiosis in Alzheimer’s Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0285346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Gao, G.; Kwok, L.-Y.; Sun, Z. Gut Microbiome-Targeted Therapies for Alzheimer’s Disease. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2271613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuervo-Zanatta, D.; Garcia-Mena, J.; Perez-Cruz, C. Gut Microbiota Alterations and Cognitive Impairment Are Sexually Dissociated in a Transgenic Mice Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2021, 82, S195–S214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Singh, S.; Prasad, S.; Mittal, A.; Sharma, A.K.; Chakrabarti, S. Gut Microbiota and Alzheimer’s Disease: Experimental Evidence and Clinical Reality. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2021, 18, 787–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasupalak, J.K.; Rajput, P.; Gupta, G.L. Gut Microbiota and Alzheimer’s Disease: Exploring Natural Product Intervention and the Gut-Brain Axis for Therapeutic Strategies. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 984, 177022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.M.; Cho, J.; Lee, C. Gut Microbiota and Alzheimer’s Disease: How to Study and Apply Their Relationship. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, R.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.-J.; Guo, J. Gut Microbiota and Alzheimer’s Disease: Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Perspectives. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2021, 83, 963–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Gao, J.; Zhu, M.; Liu, K.; Zhang, H.-L. Gut Microbiota and Dysbiosis in Alzheimer’s Disease: Implications for Pathogenesis and Treatment. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020, 57, 5026–5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piombino, P.; Marenzi, G.; Dell’Aversana Orabona, G.; Califano, L.; Sammartino, G. Autologous Fat Grafting in Facial Volumetric Restoration. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2015, 26, 756–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortellaro, C.; Dall’Oca, S.; Lucchina, A.G.; Castiglia, A.; Farronato, G.; Fenini, E.; Marenzi, G.; Trosino, O.; Cafiero, C.; Sammartino, G. Sublingual Ranula: A Closer Look to Its Surgical Management. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2008, 19, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sammartino, G.; Marenzi, G.; Tammaro, L.; Bolognese, A.; Calignano, A.; Costantino, U.; Califano, L.; Mastrangelo, F.; Tetè, S.; Vittoria, V. Anti-Inflammatory Drug Incorporation into Polymeric Nano-Hybrids for Local Controlled Release. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2005, 18, 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Sammartino, G.; Marenzi, G.; Howard, C.M.; Minimo, C.; Trosino, O.; Califano, L.; Claudio, P.P. Chondrosarcoma of the Jaw: A Closer Look at Its Management. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2008, 66, 2349–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammartino, G.; Marenzi, G.; Colella, G.; Califano, L.; Grivetto, F.; Mortellaro, C. Autogenous Calvarial Bone Graft Harvest: Intraoperational Complications. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2005, 16, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sammartino, G.; Gasparro, R.; Marenzi, G.; Trosino, O.; Mariniello, M.; Riccitiello, F. Extraction of Mandibular Third Molars: Proposal of a New Scale of Difficulty. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 55, 952–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandurra, C.; Gasparro, R.; Dolce, P.; Bochicchio, V.; Muzii, B.; Sammartino, G.; Marenzi, G.; Maldonato, N.M. The Role of Cognitive and Non-Cognitive Factors in Dental Anxiety: A Mediation Model. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2021, 129, e12793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marenzi, G.; Spagnuolo, G.; Sammartino, J.C.; Gasparro, R.; Rebaudi, A.; Salerno, M. Micro-Scale Surface Patterning of Titanium Dental Implants by Anodization in the Presence of Modifying Salts. Materials 2019, 12, 1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kustrimovic, N.; Balkhi, S.; Bilato, G.; Mortara, L. Gut Microbiota and Immune System Dynamics in Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, C.-L.; Liu, F.; Iqbal, K.; Gong, C.-X. Gut Microbiota and Immunotherapy for Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Zou, G.; Zou, X.; Wang, K.; Chen, Z. Gut Microbiota and Its Metabolites in Alzheimer’s Disease: From Pathogenesis to Treatment. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, G.; Chen, W. Gut Microbiota and Its Metabolites: Bridge of Dietary Nutrients and Alzheimer’s Disease. Adv. Nutr. Bethesda Md 2023, 14, 819–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pluta, R.; Ułamek-Kozioł, M.; Januszewski, S.; Czuczwar, S.J. Gut Microbiota and pro/Prebiotics in Alzheimer’s Disease. Aging 2020, 12, 5539–5550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giau, V.V.; Wu, S.Y.; Jamerlan, A.; An, S.S.A.; Kim, S.Y.; Hulme, J. Gut Microbiota and Their Neuroinflammatory Implications in Alzheimer’s Disease. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dykes, G. Gut Microbiota as a Link Between Modern Lifestyle and Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr. Aging Sci. 2021, 14, 164–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Quan, M.; Zhao, H.; Jia, J. Gut Microbiota Changes and Their Correlation with Cognitive and Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2021, 81, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagu, P.; Parashar, A.; Behl, T.; Mehta, V. Gut Microbiota Composition and Epigenetic Molecular Changes Connected to the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 71, 1436–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heravi, F.S.; Naseri, K.; Hu, H. Gut Microbiota Composition in Patients with Neurodegenerative Disorders (Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s) and Healthy Controls: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparro, R.; Adamo, D.; Masucci, M.; Sammartino, G.; Mignogna, M.D. Use of Injectable Platelet-Rich Fibrin in the Treatment of Plasma Cell Mucositis of the Oral Cavity Refractory to Corticosteroid Therapy: A Case Report. Dermatol. Ther. 2019, 32, e13062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inchingolo, A.M.; Ceci, S.; Coloccia, G.; Azzollini, D.; Malcangi, G.; Mancini, A.; Inchingolo, F.; Trerotoli, P.; Dipalma, G.; Patano, A. Predictability and Effectiveness of Nuvola® Aligners in Dentoalveolar Transverse Changes: A Retrospective Study. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorusso, F.; Tartaglia, G.; Inchingolo, F.; Scarano, A. Peri-Implant Mucositis Treatment with a Chlorexidine Gel with A.D.S. 0.5%, PVP-VA and Sodium DNA vs a Placebo Gel: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Clinical Trial. Front. Biosci. Elite Ed. 2022, 14, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inchingolo, F.; Ballini, A.; Georgakopoulos, P.G.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Tsantis, S.; Vito, D.D.; Cantore, S.; Georgakopoulos, I.P.; Dipalma, G. Immediate implant placement by using bone-albumin allograft and concentrated growth factors (CGFS): Preliminary results of a pilot study. Oral Implantol. 2018, 11, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Inchingolo, F.; Tatullo, M.; Abenavoli, F.M.; Marrelli, M.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Corelli, R.; Inchingolo, A.M.; Dipalma, G. Eyelid Bags. Head Face Med. 2010, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dipalma, G.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Mancini, A.; Tartaglia, G.M.; Malcangi, G.; Semjonova, A.; Ferrara, E.; Lorusso, F.; Scarano, A.; Ferati, K.; et al. High-Grade Glioma and Oral Microbiome: Association or Causality? What We Know so Far. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2022, 36, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorusso, F.; Mastrangelo, F.; Inchingolo, F.; Mortellaro, C.; Scarano, A. In Vitro Interface Changes of Two vs Three Narrow-Diameter Dental Implants for Screw-Retained Bar under Fatigue Loading Test. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2019, 33, 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Yifat, M.; Hila, E.; Avraham, H.; Inchingolo, F.; Mortellaro, C.; Peleg, O.; Mijiritsky, E. Histologic and Radiographic Characteristics of Bone Filler Under Bisphosphonates. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2019, 30, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maspero, C.; Cenzato, N.; Inchingolo, F.; Cagetti, M.G.; Isola, G.; Sozzi, D.; Del Fabbro, M.; Tartaglia, G.M. The Maxilla-Mandibular Discrepancies Through Soft-Tissue References: Reliability and Validation of the Anteroposterior Measurement. Children 2023, 10, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inchingolo, A.D.; Malcangi, G.; Ceci, S.; Patano, A.; Corriero, A.; Azzollini, D.; Marinelli, G.; Coloccia, G.; Piras, F.; Barile, G.; et al. Antispike Immunoglobulin-G (IgG) Titer Response of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-Vaccine (BNT162b2): A Monitoring Study on Healthcare Workers. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapone, B.; Ferrara, E.; Qorri, E.; Quadri, M.F.A.; Dipalma, G.; Mancini, A.; Del Fabbro, M.; Scarano, A.; Tartaglia, G.; Inchingolo, F. Intensive Periodontal Treatment Does Not Affect the Lipid Profile and Endothelial Function of Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inchingolo, A.D.; Dipalma, G.; Palmieri, G.; Di Pede, C.; Semjonova, A.; Patano, A.; Ceci, S.; Cardarelli, F.; Montenegro, V.; Garibaldi, M.; et al. Functional Breastfeeding: From Nutritive Sucking to Oral Health. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2022, 36, 121–137. [Google Scholar]

- Inchingolo, A.M.; Malcangi, G.; Ferrara, I.; Patano, A.; Viapiano, F.; Netti, A.; Azzollini, D.; Ciocia, A.M.; de Ruvo, E.; Campanelli, M.; et al. MRONJ Treatment Strategies: A Systematic Review and Two Case Reports. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirulli, N.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Patano, A.; Ceci, S.; Marinelli, G.; Malcangi, G.; Coloccia, G.; Montenegro, V.; Di Pede, C.; Ciocia, A.M.; et al. Innovative Application of Diathermy in Orthodontics: A Case Report. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 7448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhaar, B.J.H.; Hendriksen, H.M.A.; de Leeuw, F.A.; Doorduijn, A.S.; van Leeuwenstijn, M.; Teunissen, C.E.; Barkhof, F.; Scheltens, P.; Kraaij, R.; van Duijn, C.M.; et al. Gut Microbiota Composition Is Related to AD Pathology. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 794519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohesara, S.; Abdolmaleky, H.M.; Thiagalingam, S.; Zhou, J.-R. Gut Microbiota Defined Epigenomes of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases Reveal Novel Targets for Therapy. Epigenomics 2024, 16, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manfredi, J.N.; Gupta, S.K.; Vyavahare, S.; Deak, F.; Lu, X.; Buddha, L.; Wankhade, U.; Lohakare, J.; Isales, C.; Fulzele, S. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in Alzheimer’s Disease (AD): Insights from Human Clinical Studies and the Mouse AD Models. Physiol. Behav. 2025, 290, 114778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Chen, T.; Cao, M.; Yuan, C.; Reiter, R.J.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, L.; Fan, W.; Wang, X.; et al. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis Induced by Decreasing Endogenous Melatonin Mediates the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease and Obesity. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 900132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luca, M.; Di Mauro, M.; Di Mauro, M.; Luca, A. Gut Microbiota in Alzheimer’s Disease, Depression, and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: The Role of Oxidative Stress. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 4730539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, C.-C.; Chang, C.-C.; Huang, C.-W.; Nouchi, R.; Cheng, C.-H. Gut Microbiota in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease Spectrum: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Aging 2022, 14, 477–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, Y.; Du, Y.; Zhou, L.; Yue, J.; Hu, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; Lin, X.; Zhang, G.; Xiao, H.; et al. Gut Microbiota Interact with the Brain Through Systemic Chronic Inflammation: Implications on Neuroinflammation, Neurodegeneration, and Aging. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 796288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Z.-Q.; Shen, L.-L.; Li, W.-W.; Fu, X.; Zeng, F.; Gui, L.; Lü, Y.; Cai, M.; Zhu, C.; Tan, Y.-L.; et al. Gut Microbiota Is Altered in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018, 63, 1337–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, B.; Dong, X.; Cai, W.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, H. Gut Microbiota Mediates Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s Disease: Unraveling Key Factors and Mechanistic Insights. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 62, 3746–3763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfili, L.; Cuccioloni, M.; Gong, C.; Cecarini, V.; Spina, M.; Zheng, Y.; Angeletti, M.; Eleuteri, A.M. Gut Microbiota Modulation in Alzheimer’s Disease: Focus on Lipid Metabolism. Clin. Nutr. Edinb. Scotl. 2022, 41, 698–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caggiano, M.; Gasparro, R.; D’Ambrosio, F.; Pisano, M.; Di Palo, M.P.; Contaldo, M. Smoking Cessation on Periodontal and Peri-Implant Health Status: A Systematic Review. Dent. J. 2022, 10, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Esposito, V.; Lecce, M.; Marenzi, G.; Cabaro, S.; Ambrosio, M.R.; Sammartino, G.; Misso, S.; Migliaccio, T.; Liguoro, P.; Oriente, F.; et al. Platelet-Rich Plasma Counteracts Detrimental Effect of High-Glucose Concentrations on Mesenchymal Stem Cells from Bichat Fat Pad. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2020, 14, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasparro, R.; Qorri, E.; Valletta, A.; Masucci, M.; Sammartino, P.; Amato, A.; Marenzi, G. Non-Transfusional Hemocomponents: From Biology to the Clinic-A Literature Review. Bioengineering 2018, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfora, F.; Calabria, E.; Cuocolo, R.; Ugga, L.; Buono, G.; Marenzi, G.; Gasparro, R.; Pecoraro, G.; Aria, M.; D’Aniello, L.; et al. Burning Fog: Cognitive Impairment in Burning Mouth Syndrome. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 727417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Amo, F.S.L.; Yu, S.-H.; Sammartino, G.; Sculean, A.; Zucchelli, G.; Rasperini, G.; Felice, P.; Pagni, G.; Iorio-Siciliano, V.; Grusovin, M.G.; et al. Peri-Implant Soft Tissue Management: Cairo Opinion Consensus Conference. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparro, R.; Sammartino, G.; Mariniello, M.; di Lauro, A.E.; Spagnuolo, G.; Marenzi, G. Treatment of Periodontal Pockets at the Distal Aspect of Mandibular Second Molar after Surgical Removal of Impacted Third Molar and Application of L-PRF: A Split-Mouth Randomized Clinical Trial. Quintessence Int. Berl. Ger. 1985 2020, 51, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammartino, G.; Cerone, V.; Gasparro, R.; Riccitiello, F.; Trosino, O. Multidisciplinary Approach to Fused Maxillary Central Incisors: A Case Report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2014, 8, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamo, D.; Gasparro, R.; Marenzi, G.; Mascolo, M.; Cervasio, M.; Cerciello, G.; De Novellis, D.; Mignogna, M.D. Amyloidoma of the Tongue: Case Report, Surgical Management, and Review of the Literature. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 78, 1572–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rullo, R.; Festa, V.M.; Rullo, F.; Trosino, O.; Cerone, V.; Gasparro, R.; Laino, L.; Sammartino, G. The Use of Piezosurgery in Genioplasty. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2016, 27, 414–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Liao, J.; Xia, Y.; Liu, X.; Jones, R.; Haran, J.; McCormick, B.; Sampson, T.R.; Alam, A.; Ye, K. Gut Microbiota Regulate Alzheimer’s Disease Pathologies and Cognitive Disorders via PUFA-Associated Neuroinflammation. Gut 2022, 71, 2233–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, H.; Guo, Y.; Du, X.; Qin, C. Gut Microbiota Regulate Cognitive Deficits and Amyloid Deposition in a Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Neurochem. 2020, 155, 448–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Bruggeman, A.; De Nolf, C.; Vandendriessche, C.; Van Imschoot, G.; Van Wonterghem, E.; Vereecke, L.; Vandenbroucke, R.E. Gut Microbiota Regulates Blood-Cerebrospinal Fluid Barrier Function and Aβ Pathology. EMBO J. 2023, 42, e111515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Fan, Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, L.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y. Gut Microbiota-Driven Metabolic Alterations Reveal Gut-Brain Communication in Alzheimer’s Disease Model Mice. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2302310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.-X.; Yang, L.-L.; Yao, X.-Q. Gut Microbiota-Host Lipid Crosstalk in Alzheimer’s Disease: Implications for Disease Progression and Therapeutics. Mol. Neurodegener. 2024, 19, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinero, N.; Antón-Fernández, A.; Hernández, F.; Ávila, J.; Bartolomé, B.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V. Gut Microbiota, an Additional Hallmark of Human Aging and Neurodegeneration. Neuroscience 2023, 518, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.S.; Ikram, M.; Park, J.S.; Park, T.J.; Kim, M.O. Gut Microbiota, Its Role in Induction of Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology, and Possible Therapeutic Interventions: Special Focus on Anthocyanins. Cells 2020, 9, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishaa, L.; Ng, T.K.S.; Wee, H.N.; Ching, J. Gut-Brain Axis through the Lens of Gut Microbiota and Their Relationships with Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology: Review and Recommendations. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2023, 211, 111787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hao, J.; Liu, R.; Wu, T.; Liu, R.; Sui, W.; Zhang, M. Hawthorn Flavonoid Ameliorates Cognitive Deficit in Mice with Alzheimer’s Disease by Increasing the Levels of Bifidobacteriales in Gut Microbiota and Docosapentaenoic Acid in Serum Metabolites. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 12371–12382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Shi, D.; Wang, S.; Sun, Y.; Song, W.; Liu, S.; Wang, C. Hericium Coralloides Ameliorates Alzheimer’s Disease Pathologies and Cognitive Disorders by Activating Nrf2 Signaling and Regulating Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carapeto, A.P.; Marcuello, C.; Faísca, P.F.N.; Rodrigues, M.S. Morphological and Biophysical Study of S100A9 Protein Fibrils by Atomic Force Microscopy Imaging and Nanomechanical Analysis. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikalauskaite, K.; Ziaunys, M.; Sneideris, T.; Smirnovas, V. Effect of Ionic Strength on Thioflavin-T Affinity to Amyloid Fibrils and Its Fluorescence Intensity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comuzzi, L.; Ceddia, M.; Di Pietro, N.; Inchingolo, F.; Inchingolo, A.M.; Romasco, T.; Tumedei, M.; Specchiulli, A.; Piattelli, A.; Trentadue, B. Crestal and Subcrestal Placement of Morse Cone Implant-Abutment Connection Implants: An In Vitro Finite Element Analysis (FEA) Study. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szablewski, L. Human Gut Microbiota in Health and Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018, 62, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minetti, E.; Palermo, A.; Savadori, P.; Patano, A.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Rapone, B.; Malcangi, G.; Inchingolo, F.; Dipalma, G.; Tartaglia, F.C.; et al. Socket Preservation Using Dentin Mixed with Xenograft Materials: A Pilot Study. Materials 2023, 16, 4945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callea, C.; Ceddia, M.; Piattelli, A.; Specchiulli, A.; Trentadue, B. Finite Element Analysis (FEA) for a Different Type of Cono-in Dental Implant. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceddia, M.; Trentadue, B. Evaluation of Rotational Stability and Stress Shielding of a Stem Optimized for Hip Replacements—A Finite Element Study. Prosthesis 2023, 5, 678–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, T.K.; Ganesh, B.P. Interlink between the Gut Microbiota and Inflammation in the Context of Oxidative Stress in Alzheimer’s Disease Progression. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2206504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minetti, E.; Palermo, A.; Malcangi, G.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Mancini, A.; Dipalma, G.; Inchingolo, F.; Patano, A.; Inchingolo, A.M. Dentin, Dentin Graft, and Bone Graft: Microscopic and Spectroscopic Analysis. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshadidi, A.A.F.; Alshahrani, A.A.; Aldosari, L.I.N.; Chaturvedi, S.; Saini, R.S.; Hassan, S.A.B.; Cicciù, M.; Minervini, G. Investigation on the Application of Artificial Intelligence in Prosthodontics. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzunçıbuk, H.; Marrapodi, M.M.; Meto, A.; Ronsivalle, V.; Cicciù, M.; Minervini, G. Prevalence of Temporomandibular Disorders in Clear Aligner Patients Using Orthodontic Intermaxillary Elastics Assessed with Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) Axis II Evaluation: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Oral Rehabil. 2024, 51, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minervini, G.; Marrapodi, M.M.; Cicciù, M. Online Bruxism-Related Information: Can People Understand What They Read? A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Oral Rehabil. 2023, 50, 1211–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, L.E.; Cicciù, M.; Doetzer, A.; Beck, M.L.; Cervino, G.; Minervini, G. Mandibular Condylar Hyperplasia and Its Correlation with Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor. J. Oral Rehabil. 2023, 50, 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langaliya, A.; Alam, M.K.; Hegde, U.; Panakaje, M.S.; Cervino, G.; Minervini, G. Occurrence of Temporomandibular Disorders among Patients Undergoing Treatment for Obstructive Sleep Apnoea Syndrome (OSAS) Using Mandibular Advancement Device (MAD): A Systematic Review Conducted According to PRISMA Guidelines and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. J. Oral Rehabil. 2023, 50, 1554–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ağagündüz, D.; Kocaadam-Bozkurt, B.; Bozkurt, O.; Sharma, H.; Esposito, R.; Özoğul, F.; Capasso, R. Microbiota Alteration and Modulation in Alzheimer’s Disease by Gerobiotics: The Gut-Health Axis for a Good Mind. Biomed. Pharmacother. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 153, 113430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patano, A.; Inchingolo, A.M.; Cardarelli, F.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Viapiano, F.; Giotta, M.; Bartolomeo, N.; Di Venere, D.; Malcangi, G.; Minetti, E.; et al. Effects of Elastodontic Appliance on the Pharyngeal Airway Space in Class II Malocclusion. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. PLOS Med. 2021, 18, e1003583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerajewska, T.L.; Davies, M.; Allen-Birt, S.J.; Swirski, M.; Coulthard, E.J.; West, N.X. A Feasibility Study to Recruit, Retain and Treat Periodontitis in Volunteers with Mild Dementia, Whilst Monitoring Their Cognition. J. Dent. 2024, 150, 105355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hategan, S.I.; Kamer, S.A.; Craig, R.G.; Sinescu, C.; de Leon, M.J.; Jianu, D.C.; Marian, C.; Bora, B.I.; Dan, T.-F.; Birdac, C.D.; et al. Cognitive Dysfunction in Young Subjects with Periodontal Disease. Neurol. Sci. 2021, 42, 4511–4519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-K.; Wu, Y.-T.; Chang, Y.-C. Association between Chronic Periodontitis and the Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Retrospective, Population-Based, Matched-Cohort Study. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2017, 9, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; Zhou, W.; Shen, H.; Wang, J.; Tang, R.; Wang, T.; Xie, X.; Hong, B.; Ren, R.; Wang, G.; et al. Profiles of Subgingival Microbiomes and Gingival Crevicular Metabolic Signatures in Patients with Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2024, 16, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubinstein, T.; Brickman, A.M.; Cheng, B.; Burkett, S.; Park, H.; Annavajhala, M.K.; Uhlemann, A.-C.; Andrews, H.; Gutierrez, J.; Paster, B.J.; et al. Periodontitis and Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging Markers of Alzheimer’s Disease and Cognitive Aging. Alzheimers Dement. J. Alzheimers Assoc. 2024, 20, 2191–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beydoun, M.A.; Beydoun, H.A.; Hedges, D.W.; Erickson, L.D.; Gale, S.D.; Weiss, J.; El-Hajj, Z.W.; Evans, M.K.; Zonderman, A.B. Infection Burden, Periodontal Pathogens, and Their Interactive Association with Incident All-Cause and Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia in a Large National Survey. Alzheimers Dement. J. Alzheimers Assoc. 2024, 20, 6468–6485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwahn, C.; Frenzel, S.; Holtfreter, B.; Van der Auwera, S.; Pink, C.; Bülow, R.; Friedrich, N.; Völzke, H.; Biffar, R.; Kocher, T.; et al. Effect of Periodontal Treatment on Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease-Results of a Trial Emulation Approach. Alzheimers Dement. J. Alzheimers Assoc. 2022, 18, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franciotti, R.; Pignatelli, P.; Carrarini, C.; Romei, F.M.; Mastrippolito, M.; Gentile, A.; Mancinelli, R.; Fulle, S.; Piattelli, A.; Onofrj, M.; et al. Exploring the Connection between Porphyromonas gingivalis and Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Pilot Quantitative Study on the Bacterium Abundance in Oral Cavity and the Amount of Antibodies in Serum. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Kim, K.; Chang, J.; Kim, S.M.; Kim, S.J.; Cho, H.-J.; Park, S.M. Association of Chronic Periodontitis on Alzheimer’s Disease or Vascular Dementia. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 1234–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo, Á.; López-Dequidt, I.; Custodia, A.; Botelho, J.; Aramburu-Núñez, M.; Machado, V.; Pías-Peleteiro, J.M.; Ouro, A.; Romaus-Sanjurjo, D.; Vázquez-Vázquez, L.; et al. Association of Periodontitis with Cognitive Decline and Its Progression: Contribution of Blood-Based Biomarkers of Alzheimer’s Disease to This Relationship. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2023, 50, 1444–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, H.S.; Jung, N.-Y.; Song, Y.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, H.-J.; Lee, J.Y.; Chung, J. A Distinctive Subgingival Microbiome in Patients with Periodontitis and Alzheimer’s Disease Compared with Cognitively Unimpaired Periodontitis Patients. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2024, 51, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Tao, Y.; Li, H.; Huang, Z.; Li, Y.; Gao, Z.; Zhu, W.; Li, X.; Yu, Y. Periodontitis Is Associated with Altered Brain Structure and Function in Normal Cognition Middle-Aged and Elderly Individuals. J. Periodontal Res. 2024, 59, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taati Moghadam, M.; Amirmozafari, N.; Mojtahedi, A.; Bakhshayesh, B.; Shariati, A.; Masjedian Jazi, F. Association of Perturbation of Oral Bacterial with Incident of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Pilot Study. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2022, 36, e24483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Du, M.; Chen, Y.; Marks, L.A.M.; Visser, A.; Xu, S.; Tjakkes, G.E. Periodontitis and Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults: The Mediating Role of Mitochondrial Dysfunction. J. Periodontol. 2022, 93, 1302–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamer, A.R.; Pirraglia, E.; Tsui, W.; Rusinek, H.; Vallabhajosula, S.; Mosconi, L.; Yi, L.; McHugh, P.; Craig, R.G.; Svetcov, S.; et al. Periodontal Disease Associates with Higher Brain Amyloid Load in Normal Elderly. Neurobiol. Aging 2015, 36, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.-H.; Jeong, S.-N.; Lee, J.-H. Severe Periodontitis with Tooth Loss as a Modifiable Risk Factor for the Development of Alzheimer, Vascular, and Mixed Dementia: National Health Insurance Service-National Health Screening Retrospective Cohort 2002–2015. J. Periodontal Implant Sci. 2020, 50, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botelho, J.; Leira, Y.; Viana, J.; Machado, V.; Lyra, P.; Aldrey, J.M.; Pías-Peleteiro, J.M.; Blanco, J.; Sobrino, T.; Mendes, J.J. The Role of Inflammatory Diet and Vitamin D on the Link between Periodontitis and Cognitive Function: A Mediation Analysis in Older Adults. Nutrients 2021, 13, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issilbayeva, A.; Kaiyrlykyzy, A.; Vinogradova, E.; Jarmukhanov, Z.; Kozhakhmetov, S.; Kassenova, A.; Nurgaziyev, M.; Mukhanbetzhanov, N.; Alzhanova, D.; Zholdasbekova, G.; et al. Oral Microbiome Stamp in Alzheimer’s Disease. Pathogens 2024, 13, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominy, S.S.; Lynch, C.; Ermini, F.; Benedyk, M.; Marczyk, A.; Konradi, A.; Nguyen, M.; Haditsch, U.; Raha, D.; Griffin, C.; et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malcangi, G.; Patano, A.; Palmieri, G.; Pede, C.D.; Latini, G.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Hazballa, D.; de Ruvo, E.; Garofoli, G.; Inchingolo, F.; et al. Maxillary Sinus Augmentation Using Autologous Platelet Concentrates (Platelet-Rich Plasma, Platelet-Rich Fibrin, and Concentrated Growth Factor) Combined with Bone Graft: A Systematic Review. Cells 2023, 12, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagpal, R.; Neth, B.J.; Wang, S.; Craft, S.; Yadav, H. Modified Mediterranean-Ketogenic Diet Modulates Gut Microbiome and Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Association with Alzheimer’s Disease Markers in Subjects with Mild Cognitive Impairment. EBioMedicine 2019, 47, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, E.J.; Bernath, A.K.; Klegeris, A. Modifying the Diet and Gut Microbiota to Prevent and Manage Neurodegenerative Diseases. Rev. Neurosci. 2022, 33, 767–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayten, Ş.; Bilici, S. Modulation of Gut Microbiota Through Dietary Intervention in Neuroinflammation and Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2024, 13, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Wu, X. Modulation of the Gut Microbiota in Memory Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease via the Inhibition of the Parasympathetic Nervous System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsinelos, T.; Doulberis, M.; Polyzos, S.A.; Papaefthymiou, A.; Katsinelos, P.; Kountouras, J. Molecular Links Between Alzheimer’s Disease and Gastrointestinal Microbiota: Emphasis on Helicobacter Pylori Infection Involvement. Curr. Mol. Med. 2019, 20, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, R.; Han, W.; Jiang, H.; Bi, C.; Zhang, Z.; Ye, M.; Lin, X.; Liu, Z. Molecular Mechanism and Therapeutic Strategy of Bile Acids in Alzheimer’s Disease from the Emerging Perspective of the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Biomed. Pharmacother. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 178, 117228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, X.; Zhao, X.; Liu, K.; Yang, X.; He, Q.; Gao, Y.; Li, W.; Han, W. Mulberry Leaf Compounds and Gut Microbiota in Alzheimer’s Disease and Diabetes: A Study Using Network Pharmacology, Molecular Dynamics Simulation, and Cellular Assays. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, C.; Li, Q.-P.; Su, Z.-R.; Ip, S.-P.; Yuan, Q.-J.; Xie, Y.-L.; Xu, Q.-Q.; Yang, W.; Huang, Y.-F.; Xian, Y.-F.; et al. Nano-Honokiol Ameliorates the Cognitive Deficits in TgCRND8 Mice of Alzheimer’s Disease via Inhibiting Neuropathology and Modulating Gut Microbiota. J. Adv. Res. 2022, 35, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; He, K.; Wu, D.; Zhou, L.; Li, G.; Lin, Z.; Yang, X.; Liu, J.; Pui Man Hoi, M. Natural Dietary Compound Xanthohumol Regulates the Gut Microbiota and Its Metabolic Profile in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Molecules 2022, 27, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Zheng, L.J.; Zhang, L.J. Neuroinflammation, Gut Microbiome, and Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 8243–8250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargiulo Isacco, C.; Ballini, A.; Paduanelli, G.; Nguyen, K.C.D.; Schiffman, M.; Aityan, S.K.; Tapparo, O.; Khoa, N.; Dipalma, G.; Inchingolo, F.; et al. A Systematic Review on Persistent Trigeminal Artery, in Searching for a Therapeutic Solution to Idiopathic and Unresponsive Trigeminal Nerve Inflammations and Migraines. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2019, 33, 155–169. [Google Scholar]

- Mancini, A.; Laforgia, A.; Dipalma, G.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Fiore, A.; Balestriere, L.; Tartaglia, F.C.; Corsalini, M.; Paduanelli, G.; Palermo, A.; et al. Recurrence of Relapse After Orthognathic Surgery Treatment: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2024, 13, S94–S102. [Google Scholar]

- Memè, L.; Bambini, F.; Sampalmieri, F.; Dipalma, G.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Lauria, P.; Carone, C.; Sabatelli, F.; Corsalini, M.; Paduanelli, G.; et al. Exploring the Positive Impact of Probiotics on Oral Health: A Comprehensive Systematic Review. Eur. J. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2024, 13, S164–S174. [Google Scholar]

- Memè, L.; Bambini, F.; Dipalma, G.; Sampalmieri, F.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Pennacchio, B.F.P.; Giorgio, R.V.; Sabatelli, F.; Paduanelli, G.; Tartaglia, F.C.; et al. Impact of Endodontic Treatment on Systemic Oxidative Stress in Chronic Apical Periodontitis: A Prospective Study. Eur. J. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2024, 13, S144–S150. [Google Scholar]

- Memè, L.; Bambini, F.; Sampalmieri, F.; Dipalma, G.; Inchingolo, A.M.; Pennacchio, B.F.P.; Giorgio, R.V.; Corsalini, M.; Paduanelli, G.; Tartaglia, F.C.; et al. The Therapeutic Potential of CBD In Dentistry: Applications, Mechanisms, And Future Prospects. Eur. J. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2024, 13, S183–S189. [Google Scholar]

- Memè, L.; Bambini, F.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Sampalmieri, F.; Dipalma, G.; Nardelli, P.; Casamassima, L.; Corsalini, F.M.; Sabatelli, F.; Paduanelli, G.; et al. Orthodontic bracket placement: Direct and indirect bonding techniques. A systematic review. Eur. J. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2024, 13, S134–S143. [Google Scholar]

- Mancini, A.; Laforgia, A.; Viapiano, F.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Cardarelli, F.; Paduanelli, G.; Ruvo, E.; Tari, S.R.; Malcangi, G.; Inchingolo, F.; et al. Amcop® Elastodontic Devices in Orthodontics: A Literature Review. Eur. J. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2024, 13, S52–S59. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, C.; Munteanu, C.; Anghelescu, A.; Ciobanu, V.; Spînu, A.; Andone, I.; Mandu, M.; Bistriceanu, R.; Băilă, M.; Postoiu, R.-L.; et al. Novelties on Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s Disease-Focus on Gut and Oral Microbiota Involvement. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, J.; Chen, Y. Regulation of Neurotransmitters by the Gut Microbiota and Effects on Cognition in Neurological Disorders. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerkezi, S.; Nakova, M.; Gorgoski, I.; Ferati, K.; Bexheti-Ferati, A.; Palermo, A.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Ferrante, L.; Inchingolo, A.M.; Inchingolo, F.; et al. The Role of Sulfhydryl (Thiols) Groups in Oral and Periodontal Diseases. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolci, C.; Cenzato, N.; Maspero, C.; Giannini, L.; Khijmatgar, S.; Dipalma, G.; Tartaglia, G.M.; Inchingolo, F. Skull Biomechanics and Simplified Cephalometric Lines for the Estimation of Muscular Lines of Action. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipalma, G.; Inchingolo, A.M.; Malcangi, G.; Ferrara, I.; Viapiano, F.; Netti, A.; Patano, A.; Isacco, C.G.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Inchingolo, F. Sixty-Month Follow Up of Clinical MRONJ Cases Treated with CGF and Piezosurgery. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunert, M.; Piwonski, I.; Hardan, L.; Bourgi, R.; Sauro, S.; Inchingolo, F.; Lukomska-Szymanska, M. Dentine Remineralisation Induced by “Bioactive” Materials through Mineral Deposition: An In Vitro Study. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marizzoni, M.; Cattaneo, A.; Mirabelli, P.; Festari, C.; Lopizzo, N.; Nicolosi, V.; Mombelli, E.; Mazzelli, M.; Luongo, D.; Naviglio, D.; et al. Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Lipopolysaccharide as Mediators Between Gut Dysbiosis and Amyloid Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2020, 78, 683–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doifode, T.; Giridharan, V.V.; Generoso, J.S.; Bhatti, G.; Collodel, A.; Schulz, P.E.; Forlenza, O.V.; Barichello, T. The Impact of the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis on Alzheimer’s Disease Pathophysiology. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 164, 105314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, J.-T.; Xu, X.-W.; Jin, C.-Y.; Yuan, X.-Y.; Wang, X.-G. The Influence of the Gut Microbiota on Alzheimer’s Disease: A Narrative Review. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2023, 22, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasmi, M.; Silvia Hardiany, N.; van der Merwe, M.; Martins, I.J.; Sharma, A.; Williams-Hooker, R. The Influence of Time-Restricted Eating/Feeding on Alzheimer’s Biomarkers and Gut Microbiota. Nutr. Neurosci. 2025, 28, 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, W.; Zhang, L.; Wang, M.; Chang, W. The Interaction of Polyphenols and the Gut Microbiota in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megur, A.; Baltriukienė, D.; Bukelskienė, V.; Burokas, A. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis and Alzheimer’s Disease: Neuroinflammation Is to Blame? Nutrients 2020, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, E.R.; Kemp, M.; Nguyen, T.T. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Review of Taxonomic Alterations and Potential Avenues for Interventions. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2022, 37, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirstea, M.S.; Kliger, D.; MacLellan, A.D.; Yu, A.C.; Langlois, J.; Fan, M.; Boroomand, S.; Kharazyan, F.; Hsiung, R.G.Y.; MacVicar, B.A.; et al. The Oral and Fecal Microbiota in a Canadian Cohort of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2022, 87, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varesi, A.; Pierella, E.; Romeo, M.; Piccini, G.B.; Alfano, C.; Bjørklund, G.; Oppong, A.; Ricevuti, G.; Esposito, C.; Chirumbolo, S.; et al. The Potential Role of Gut Microbiota in Alzheimer’s Disease: From Diagnosis to Treatment. Nutrients 2022, 14, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.H.; Chae, C.W.; Han, H.J. The Potential Role of Gut Microbiota-Derived Metabolites as Regulators of Metabolic Syndrome-Associated Mitochondrial and Endolysosomal Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 1691–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tursumetova, D.R.; Khan, Y.; Tkacheva, L.V.; Rayevskii, K.P. The role and features of the gut microbiota in Alzheimer’s disease. Adv. Gerontol. Uspekhi Gerontol. 2024, 37, 442–452. [Google Scholar]

- Dissanayaka, D.M.S.; Jayasena, V.; Rainey-Smith, S.R.; Martins, R.N.; Fernando, W.M.A.D.B. The Role of Diet and Gut Microbiota in Alzheimer’s Disease. Nutrients 2024, 16, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Article screening strategy | KEYWORDS: “A”: Alzheimer; “B”: parodont*; |

| Boolean indicators: “A” AND “B” | |

| Timespan: 1–15 January 2025 | |

| Electronic databases: Pubmed; Scopus; Web of Science |

| Authors | Type of Study | Aim of Study | Matherials and Methods | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerajewska et al. (2024) [220] | Feasibility interventional study | Determine the feasibility of recruiting, retaining, and treating individuals with mild dementia and periodontitis; assess cognition during dental visits. | Non-randomized clinical study, cognitive and periodontal assessments over 24 months, involving professional and personalized care. | In total, 18 participants enrolled, 15 completed 12 months, 8 completed 24 months. Significant improvement in periodontal health indicators (e.g., reduced bleeding and plaque levels). Cognition declined initially but stabilized later. |

| Hategan et al. (2021) [221] | Cross-sectional neuropsychological study | Investigate whether young healthy subjects with periodontal disease have lower cognition compared to those without periodontal disease, and assess salivary cytokine levels in relation to cognition. | Monocenter, cross-sectional study with 40 subjects divided into three groups based on periodontal condition: aggressive periodontitis, mild/moderate periodontitis, and no periodontitis. Neuropsychological tests (RAVLT, MOCA, MMSE) and ELISA for cytokine levels. | Subjects with aggressive periodontitis had impaired cognition and learning rates. Salivary IL-1β correlated with immediate memory but not delayed recall. |