Harnessing AI for Sustainable Shipping and Green Ports: Challenges and Opportunities

Abstract

1. Introduction

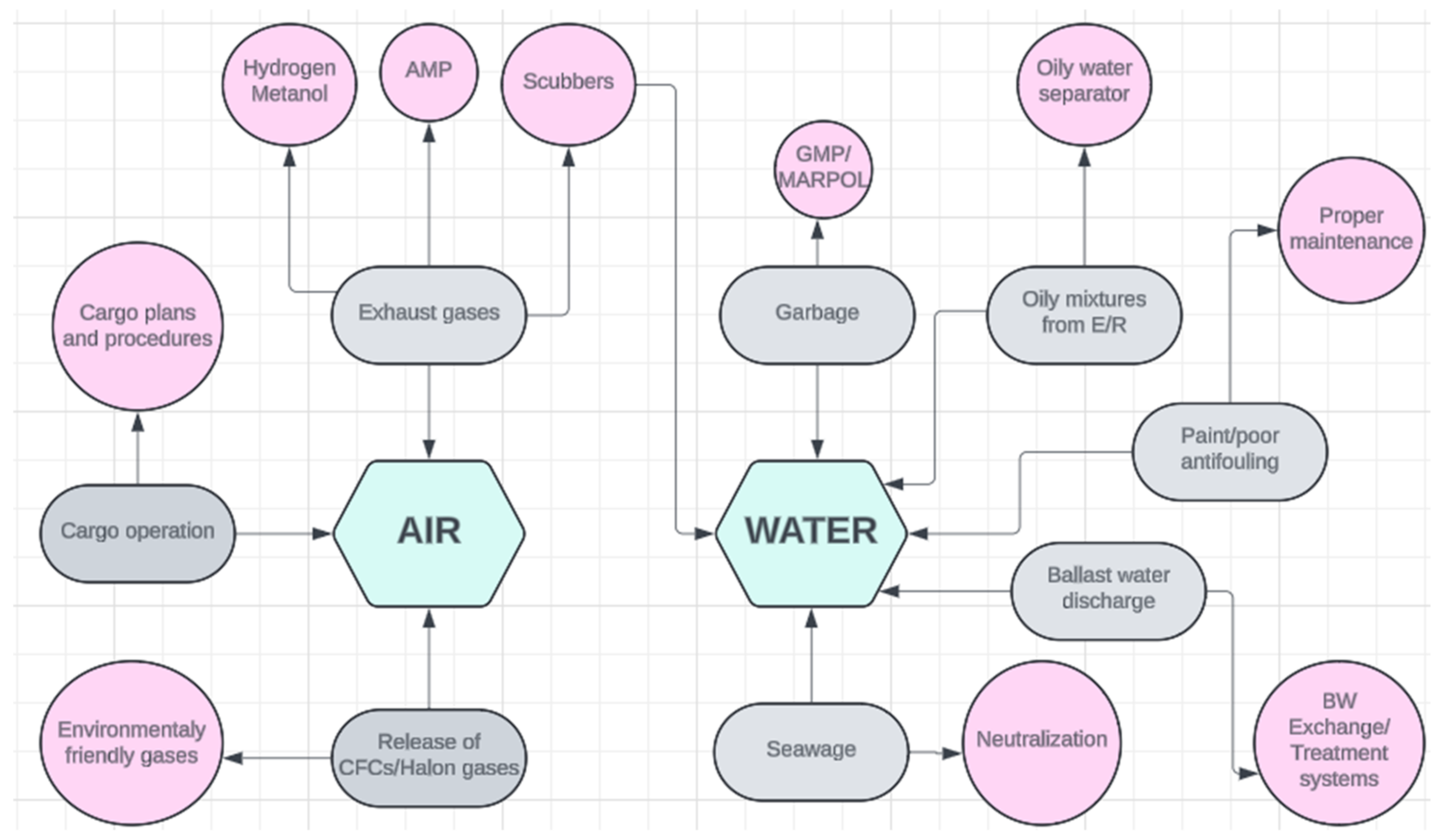

- Exhaust gases from main and auxiliary engines and incinerator—energy production can release to the atmosphere material like CO2, SO2, NOx, and hydrocarbons.

- 3.

- 4.

- Oily mixtures from the engine room (ER), which can pollute the ocean if pumped overboard. The only time when a vessel is allowed to pump engine room bilge water overboard is when pumping it through an oily water separator, which separates the oil from the water and measures the oil contents in the overboard water. If the oil content is more than 15 ppm (parts per million) it is not allowed to pump it overboard, and this water must retain onboard in dedicated tanks for delivery to an appropriate shore facility [22,23,24];

- 5.

- Paint, tin, and poor condition of the antifouling system, which is used to prevent the accumulation of marine organisms on the ship’s hull. These organisms, such as algae, crustaceans, and mollusks, can attach to the ship’s hull, leading to increased hydrodynamic resistance, fuel consumption, and operational costs as well as an increased risk of transferring invasive species between different ecosystems [25,26,27,28];

- 6.

- Discharge of ballast water and bilges, which can pose a threat to coastlines by introducing alien species into the local ecosystem and causing irreversible changes. Therefore, the Ballast Water Management Convention of 2004 obliges ships to apply one of the two ballast water control standards presented in the Section D Standards for Ballast Water Management. Ships carrying ballast water and using the D-1 method, i.e., ballast water exchange, in order to meet the requirements described in Regulation B-4 of the BWM Convention, should exchange ballast water at a distance of no less than 200 nautical miles from the nearest land and in water depths of no less than 200 m. If these requirements cannot be met, ballast water should be exchanged as far from land as possible, at a distance of no less than 50 nautical miles, maintaining a sea depth of 200 m. Ships performing ballast water exchange shall do so with an efficiency of 95 per cent volumetric exchange of ballast water (i.e., 95% of the volume of the tank must be exchanged).

- Electric pulse/pulse plasma systems;

- Filtration systems (physical);

- Chemical disinfection (oxidizing and non-oxidizing biocides), including ozone generators;

- Ultraviolet treatment;

- Deoxygenation treatment;

- Heat (thermal) treatment;

- Acoustic (cavitation) treatment;

- 7.

- Sewage and garbage—sewage should be collected in a dedicated tank and neutral-ized before being disposed of in the sea. Garbage should only be disposed of when permitted by the MARPOL convention and the implemented garbage management plan (GMP). Regarding garbage disposal, there are eight special areas defined in the Convention: the Baltic Sea area, the Mediterranean Sea, the Black Sea, the Red Sea, the North Sea, the Antarctic, the Gulfs, and the Wider Caribbean. Inside a special area, a vessel must be at least 12 nautical miles from land and en route, and only food waste ground to less than 25 mm can be discharged. Outside the special areas and while en route, food waste can be disposed at greater than 12 nautical miles from the nearest land. Between a distance of 3 and 12 nautical miles, only food waste that has been ground to less than 25 mm can be discharged from a vessel. The discharge overboard of all other garbage is strictly prohibited [32,33,34,35].

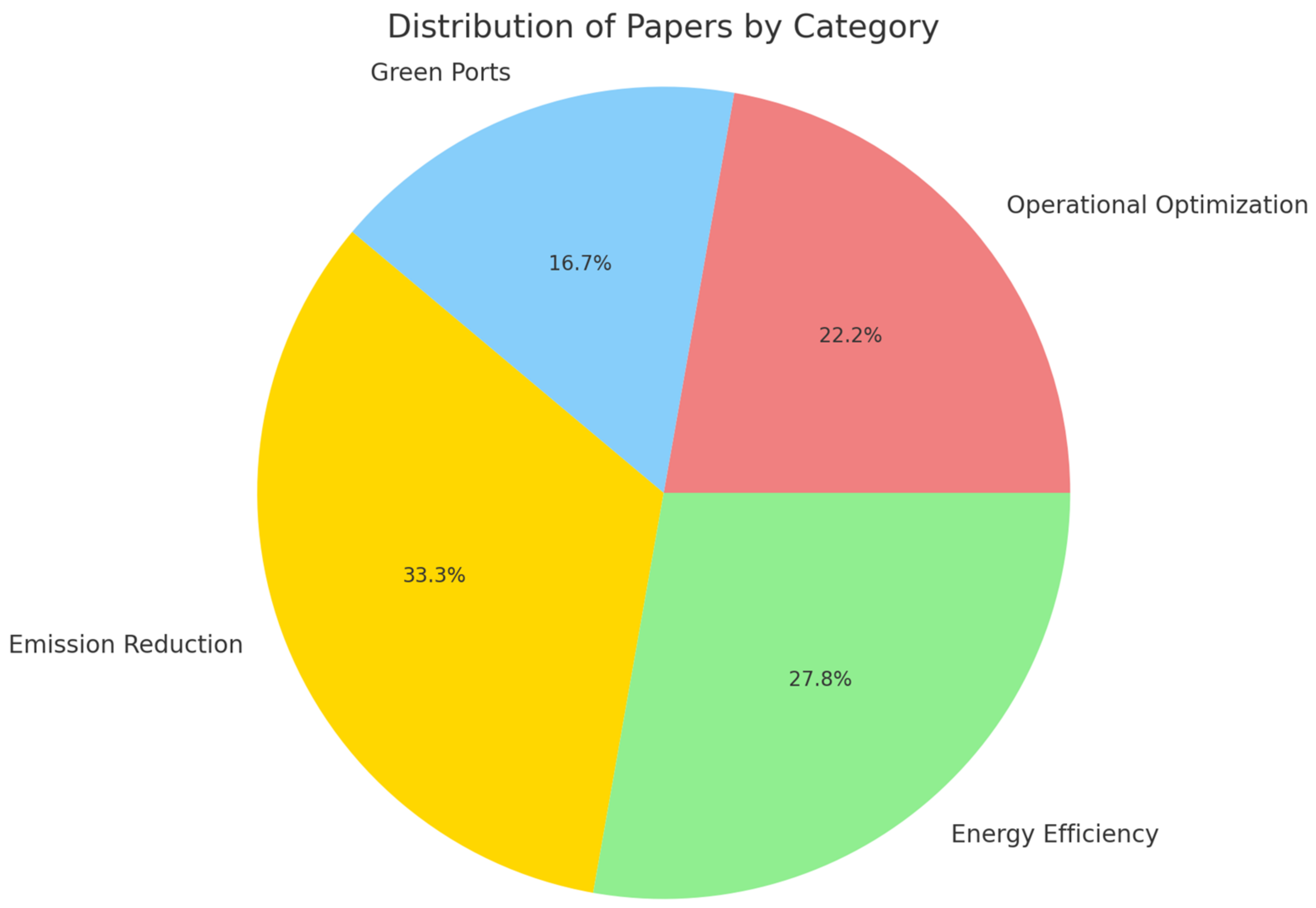

- Emission reduction: analyzing AI algorithms and predictive models that optimize fuel consumption and minimize emissions;

- Energy efficiency: investigating AI-driven solutions for route optimization and smart energy management on vessels;

- Operational optimization: evaluating the role of AI in autonomous shipping, navigation systems, and logistics management;

- Green ports: assessing AI applications in port operations, environmental monitoring, and smart port infrastructure.

2. Methodology

- Identification of Sources

- 2.

- Selection Criteria

- 3.

- Data Extraction

- 4.

- Synthesis

- 1.

- Thematic Analysis

- 2.

- Comparative Analysis

- 3.

- Gap Analysis

- 4.

- Evaluation of Impact

3. The Role of AI in Sustainable Shipping

3.1. Emission Reduction

3.2. Energy Efficiency

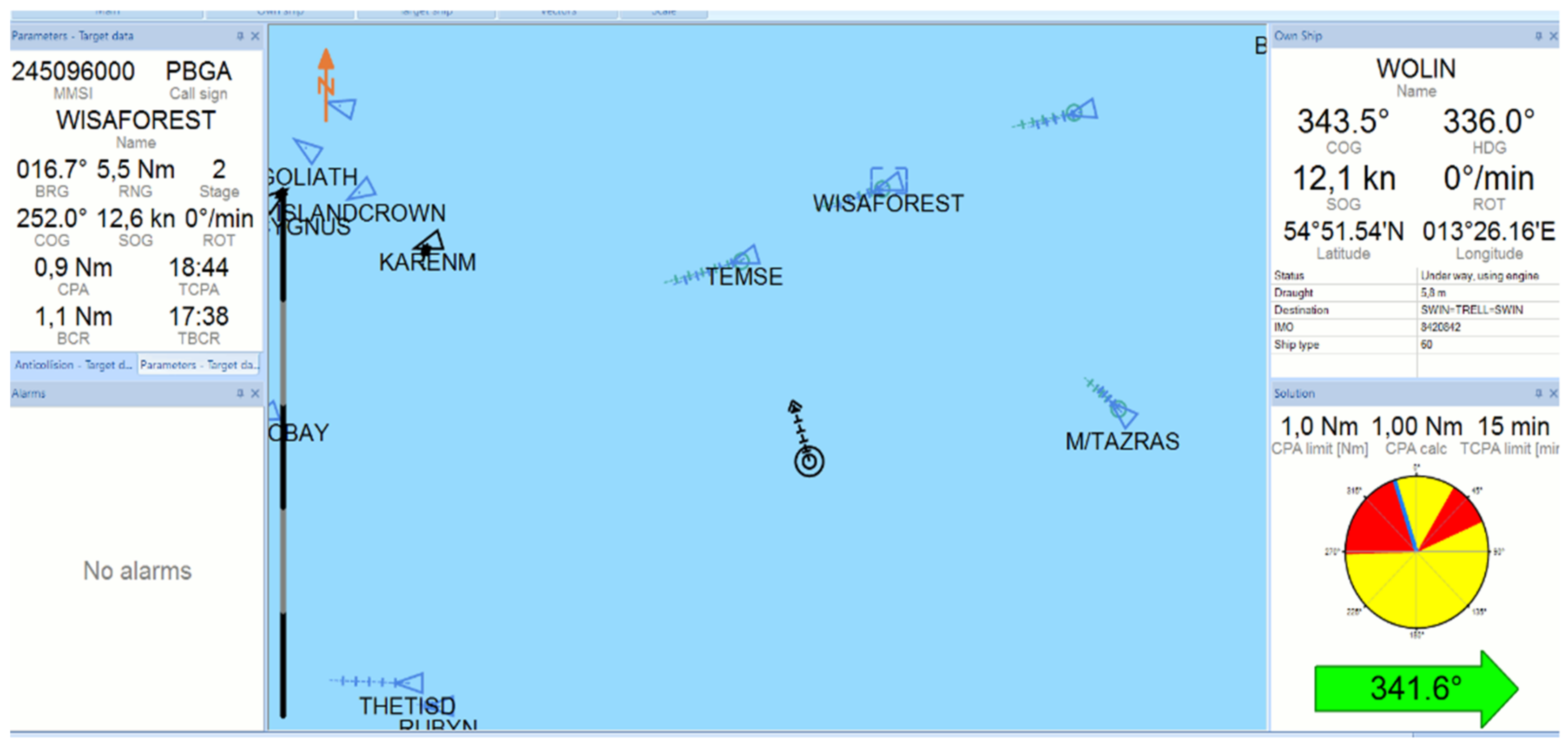

3.3. Operational Optimization

4. AI in Green Ports

4.1. Port Operations

4.2. Environmental Monitoring

4.3. Smart Port Infrastructure

5. Case Studies

5.1. Case Study 1: Successful AI Implementation in Shipping

5.1.1. Company Overview: Maersk Line

5.1.2. AI Implementation: Fuel Optimization and Predictive Maintenance

Fuel Optimization

Predictive Maintenance

Outcomes

- A substantial reduction in fuel consumption and CO2 emissions;

- Enhanced route planning, leading to more efficient and timely deliveries;

- Improved maintenance practices, resulting in reduced operational disruptions and costs;

- Overall, Maersk’s adoption of AI technologies positioned the company as a leader in sustainable shipping practices.

5.2. Case Study 2: AI in Maritime Environmental Monitoring

5.2.1. Project Overview: Port of Rotterdam

5.2.2. AI Implementation: Comprehensive Environmental Monitoring System

Air Quality Monitoring

Water Quality Monitoring

Outcomes

- Enhanced real-time monitoring and management of air and water quality;

- Rapid identification and response to pollution events, minimizing environmental damage;

- Improved compliance with environmental regulations and standards;

- Increased transparency and communication with the public regarding environmental performance.

6. Challenges and Opportunities

6.1. Challenges

6.2. Opportunities

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, X.; Yuen, K.F.; Wong, Y.D.; Li, K.X. How Can the Maritime Industry Meet Sustainable Development Goals? An Analysis of Sustainability Reports from the Social Entrepreneurship Perspective. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2020, 78, 102173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, T.; Adams, M.; Walker, T.R. Role of Sustainability in Global Seaports. Ocean. Coast Manag. 2021, 202, 105435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saether, E.A.; Eide, A.E.; Bjørgum, Ø. Sustainability among Norwegian Maritime Firms: Green Strategy and Innovation as Mediators of Long-term Orientation and Emission Reduction. Bus Strategy c 2021, 30, 2382–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawson, A.; Brito, M.; Sabeur, Z. Spatial Modeling of Maritime Risk Using Machine Learning. Risk Anal. 2022, 42, 2291–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, J.; Wan, Z.; Yu, M.; Shu, Y.; Tan, Z.; Liu, J. Challenges and Countermeasures for International Ship Waste Management: IMO, China, United States, and EU. Ocean. Coast Manag. 2021, 213, 105836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, V.J.; Kim, H.; Munim, Z.H. A Review of Ship Energy Efficiency Research and Directions towards Emission Reduction in the Maritime Industry. J. Clean Prod. 2022, 366, 132888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ytreberg, E.; Åström, S.; Fridell, E. Valuating Environmental Impacts from Ship Emissions—The Marine Perspective. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 282, 111958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Meyer-Habighorst, C.; Humpe, A. A Global Review of Marine Air Pollution Policies, Their Scope and Effectiveness. Ocean. Coast Manag. 2021, 212, 105824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitsky, M. Climate Change Series Black Carbon and Climate Change Considerations for International Development Agencies. Environ. Dep. Pap. 2011, 112, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Smaradhana, D.F.; Prabowo, A.R.; Ganda, A.N.F. Exploring the Potential of Graphene Materials in Marine and Shipping Industries—A Technical Review for Prospective Application on Ship Operation and Material-Structure Aspects. J. Ocean. Eng. Sci. 2021, 6, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deja, A.; Ulewicz, R.; Kyrychenko, Y. Analysis and Assessment of Environmental Threats in Maritime Transport. Transp. Res. Procedia 2021, 55, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, B.O.; Akyar, D.A.; Celik, M.S. A Novel FMEA Approach for Risk Assessment of Air Pollution from Ships. Mar. Policy 2023, 150, 105536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Zhu, Y.; Feng, Y.; Yang, J.; Xia, C. A Prompt Decarbonization Pathway for Shipping: Green Hydrogen, Ammonia, and Methanol Production and Utilization in Marine Engines. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, M.; Ilinca, A.; Martini, F. Ship Energy Efficiency and Maritime Sector Initiatives to Reduce Carbon Emissions. Energies 2022, 15, 7910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodorowyświat.pl. Available online: https://wodorowyswiat.pl/rosnie-popularnosc-statkow-na-wodor/ (accessed on 4 July 2024).

- Yang, J.; Tang, T.; Jiang, Y.; Karavalakis, G.; Durbin, T.D.; Wayne Miller, J.; Cocker, D.R.; Johnson, K.C. Controlling Emissions from an Ocean-Going Container Vessel with a Wet Scrubber System. Fuel 2021, 304, 121323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picone, M.; Russo, M.; Distefano, G.G.; Baccichet, M.; Marchetto, D.; Volpi Ghirardini, A.; Lunde Hermansson, A.; Petrovic, M.; Gros, M.; Garcia, E.; et al. Impacts of Exhaust Gas Cleaning Systems (EGCS) Discharge Waters on Planktonic Biological Indicators. Mar. Pollut. Bull 2023, 190, 114846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winnes, H.; Fridell, E.; Moldanová, J. Effects of Marine Exhaust Gas Scrubbers on Gas and Particle Emissions. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Pu, J.; Xu, X.; Mei, X. Research on Safety Risks Analysis and Protective Measures of Ammonia as Marine Fuel. In Proceedings of the 2022 7th International Conference on Power and Renewable Energy (ICPRE), Shanghai, China, 23 September 2022; pp. 766–771. [Google Scholar]

- Martinho, G.; Castro, P.J.; Santos, P.; Alves, A.; Araújo, J.M.M.; Pereiro, A.B. A Social Study of the Technicians Dealing with Refrigerant Gases: Diagnosis of the Behaviours, Knowledge and Importance Attributed to the F-Gases. Int. J. Refrig. 2023, 146, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, W.J.; Kidder, M.K.; Bare, S.R.; Delferro, M.; Morris, J.R.; Toma, F.M.; Senanayake, S.D.; Autrey, T.; Biddinger, E.J.; Boettcher, S.; et al. A US Perspective on Closing the Carbon Cycle to Defossilize Difficult-to-Electrify Segments of Our Economy. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2024, 8, 376–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusuf, A.A.; Yusuf, D.A.; Jie, Z.; Bello, T.Y.; Tambaya, M.; Abdullahi, B.; Muhammed-Dabo, I.A.; Yahuza, I.; Dandakouta, H. Influence of Waste Oil-Biodiesel on Toxic Pollutants from Marine Engine Coupled with Emission Reduction Measures at Various Loads. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2022, 13, 101258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaffery, C.; Zhu, H.; Karavalakis, G.; Durbin, T.D.; Miller, J.W.; Johnson, K.C. Sources of Air Pollutants from a Tier 2 Ocean-Going Container Vessel: Main Engine, Auxiliary Engine, and Auxiliary Boiler. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 245, 118023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarney, J. Evolution in the Engine Room: A Review of Technologies to Deliver Decarbonised, Sustainable Shipping. Johns. Matthey Technol. Rev. 2020, 64, 374–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, F.G.; De-la-Torre, G.E. Environmental Pollution with Antifouling Paint Particles: Distribution, Ecotoxicology, and Sustainable Alternatives. Mar. Pollut. Bull 2021, 169, 112529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayomi, O.S.I.; Agboola, O.; Akande, I.G.; Emmanuel, A.O. Challenges of Coatings in Aerospace, Automobile and Marine Industries. AIP Conf. Proc. 2020, 2307, 020038. [Google Scholar]

- Kyei, S.K.; Darko, G.; Akaranta, O. Chemistry and Application of Emerging Ecofriendly Antifouling Paints: A Review. J. Coat Technol. Res. 2020, 17, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadan, N.E.; Akash, P.S.; Kumar, P.G.S. Biofouling Impacts and Toxicity of Antifouling Agents on Marine Environment: A Qualitative Study. Sustain. Agri. Food Environ. Res. 2021, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, T.A.; Meidiana, C.; Dzarfan Othman, M.H.; Goh, H.H.; Chew, K.W. Strengthening Waste Recycling Industry in Malang (Indonesia): Lessons from Waste Management in the Era of Industry 4.0. J. Clean Prod. 2023, 382, 135296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanspahić, N.; Pećarević, M.; Hrdalo, N.; Čampara, L. Analysis of Ballast Water Discharged in Port—A Case Study of the Port of Ploče (Croatia). J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Convention for the Control and Management of Ships’ Ballast Water and Sediments (BWM). Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/About/Conventions/Pages/International-Convention-for-the-Control-and-Management-of-Ships%27-Ballast-Water-and-Sediments-(BWM).aspx (accessed on 4 July 2024).

- Siddiqua, A.; Hahladakis, J.N.; Al-Attiya, W.A.K.A. An Overview of the Environmental Pollution and Health Effects Associated with Waste Landfilling and Open Dumping. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 58514–58536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukaogo, P.O.; Ewuzie, U.; Onwuka, C.V. Environmental Pollution: Causes, Effects, and the Remedies. In Microorganisms for Sustainable Environment and Health; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 419–429. [Google Scholar]

- Dąbrowska, J.; Sobota, M.; Świąder, M.; Borowski, P.; Moryl, A.; Stodolak, R.; Kucharczak, E.; Zięba, Z.; Kazak, J.K. Marine Waste—Sources, Fate, Risks, Challenges and Research Needs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wear, S.L.; Acuña, V.; McDonald, R.; Font, C. Sewage Pollution, Declining Ecosystem Health, and Cross-Sector Collaboration. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 255, 109010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.I.; Mehta, N.; Elgarahy, A.M.; Hefny, M.; Al-Hinai, A.; Al-Muhtaseb, A.H.; Rooney, D.W. Hydrogen Production, Storage, Utilisation and Environmental Impacts: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 153–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.E.; Burrows, M.T.; Hobday, A.J.; Sen Gupta, A.; Moore, P.J.; Thomsen, M.; Wernberg, T.; Smale, D.A. Socioeconomic Impacts of Marine Heatwaves: Global Issues and Opportunities. Science 2021, 374, eabj3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen Gupta, A.; Thomsen, M.; Benthuysen, J.A.; Hobday, A.J.; Oliver, E.; Alexander, L.V.; Burrows, M.T.; Donat, M.G.; Feng, M.; Holbrook, N.J.; et al. Drivers and Impacts of the Most Extreme Marine Heatwave Events. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asif, Z.; Chen, Z.; An, C.; Dong, J. Environmental Impacts and Challenges Associated with Oil Spills on Shorelines. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baley, C.; Davies, P.; Troalen, W.; Chamley, A.; Dinham-Price, I.; Marchandise, A.; Keryvin, V. Sustainable Polymer Composite Marine Structures: Developments and Challenges. Prog. Mater Sci. 2024, 145, 101307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, A.; Das, J.; Agrawal, N.R.; Kushwaha, G.S.; Ghosh, M.; Son, Y.-O. Marine Antimicrobial Peptides-Based Strategies for Tackling Bacterial Biofilm and Biofouling Challenges. Molecules 2022, 27, 7546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, F.A. Chioma Ann Udeh Review of Crew Resilience and Mental Health Practices in the Marine Industry: Pathways to Improvement. Magna Sci. Adv. Biol. Pharm. 2024, 11, 033–049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inal, O.B.; Charpentier, J.-F.; Deniz, C. Hybrid Power and Propulsion Systems for Ships: Current Status and Future Challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 156, 111965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munim, Z.H.; Dushenko, M.; Jimenez, V.J.; Shakil, M.H.; Imset, M. Big Data and Artificial Intelligence in the Maritime Industry: A Bibliometric Review and Future Research Directions. Marit. Policy Manag. 2020, 47, 577–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battineni, G.; Chintalapudi, N.; Ricci, G.; Ruocco, C.; Amenta, F. Exploring the Integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Augmented Reality (AR) in Maritime Medicine. Artif. Intell Rev. 2024, 57, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexiou, K.; Pariotis, E.G.; Zannis, T.C.; Leligou, H.C. Prediction of a Ship’s Operational Parameters Using Artificial Intelligence Techniques. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlik, I.; Miller, T.; Cembrowska-Lech, D.; Krzemińska, A.; Złoczowska, E.; Nowak, A. Navigating the Sea of Data: A Comprehensive Review on Data Analysis in Maritime IoT Applications. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makridis, G.; Kyriazis, D.; Plitsos, S. Predictive Maintenance Leveraging Machine Learning for Time-Series Forecasting in the Maritime Industry. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Rhodes, Greece, 20 September 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kretschmann, L. Leading Indicators and Maritime Safety: Predicting Future Risk with a Machine Learning Approach. J. Shipp. Trade 2020, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, C.; Jiang, L.; An, L.; Yang, R. Collision-Avoidance Navigation Systems for Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships: A State of the Art Survey. Ocean. Eng. 2021, 235, 109380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.; Sun, Y.; Yuan, C.; Yan, X.; Tang, X. Research Progress on Ship Power Systems Integrated with New Energy Sources: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 144, 111048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soori, M.; Arezoo, B.; Dastres, R. Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning and Deep Learning in Advanced Robotics, a Review. Cogn. Robot. 2023, 3, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grønsund, T.; Aanestad, M. Augmenting the Algorithm: Emerging Human-in-the-Loop Work Configurations. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2020, 29, 101614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, D.; Ferreira, L. Application of Predictive Maintenance Concepts Using Artificial Intelligence Tools. Appl. Sci. 2020, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keleko, A.T.; Kamsu-Foguem, B.; Ngouna, R.H.; Tongne, A. Artificial Intelligence and Real-Time Predictive Maintenance in Industry 4.0: A Bibliometric Analysis. AI Ethics 2022, 2, 553–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, W.; Han, J.; Rhee, W. AI-Assistance for Predictive Maintenance of Renewable Energy Systems. Energy 2021, 221, 119775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çınar, Z.M.; Abdussalam Nuhu, A.; Zeeshan, Q.; Korhan, O.; Asmael, M.; Safaei, B. Machine Learning in Predictive Maintenance towards Sustainable Smart Manufacturing in Industry 4.0. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Ruiz, M.Á.; de Almeida, I.M.; Pérez Fernández, R. Application of Machine Learning Techniques to the Maritime Industry. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munim, Z.H.; Sørli, M.A.; Kim, H.; Alon, I. Predicting Maritime Accident Risk Using Automated Machine Learning. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 248, 110148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, N.; Wang, J.-B.; Zeng, C.; Zhang, H.; Lin, M.; Li, G.Y. Unmanned-Surface-Vehicle-Aided Maritime Data Collection Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 19773–19786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Perera, L.P.; Sollid, M.-P.; Batalden, B.-M.; Sydnes, A.K. Safety Challenges Related to Autonomous Ships in Mixed Navigational Environments. WMU J. Marit. Aff. 2022, 21, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y. Harnessing the Power of Machine Learning for AIS Data-Driven Maritime Research: A Comprehensive Review. Transp. Res. E Logist Transp. Rev. 2024, 183, 103426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaganos, G.; Nikitakos, N.; Dalaklis, D.; Ölcer, A.I.; Papachristos, D. Machine Learning Algorithms in Shipping: Improving Engine Fault Detection and Diagnosis via Ensemble Methods. WMU J. Marit. Aff. 2020, 19, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maray, M.; Alghamdi, M.; Alrayes, F.S.; Alotaibi, S.S.; Alazwari, S.; Alabdan, R.; Al Duhayyim, M. Intelligent Metaheuristics with Optimal Machine Learning Approach for Malware Detection on IoT-enabled Maritime Transportation Systems. Expert Syst. 2022, 39, e13155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algarni, A.; Acarer, T.; Ahmad, Z. An Edge Computing-Based Preventive Framework With Machine Learning- Integration for Anomaly Detection and Risk Management in Maritime Wireless Communications. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 53646–53663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, D.; Bhati, B.S.; Nagpal, B.; Sankhwar, S.; Al-Turjman, F. An Enhanced Intelligent Model: To Protect Marine IoT Sensor Environment Using Ensemble Machine Learning Approach. Ocean. Eng. 2021, 242, 110180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, O.; Bayraktar, M.; Sokukcu, M. Comparative Study of Machine Learning Techniques to Predict Fuel Consumption of a Marine Diesel Engine. Ocean. Eng. 2023, 286, 115505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.; Yeung, J.-K.-W.; Lau, Y.-Y.; So, J. Technical Sustainability of Cloud-Based Blockchain Integrated with Machine Learning for Supply Chain Management. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Huang, C. Quantitative Mapping of the Evolution of AI Policy Distribution, Targets and Focuses over Three Decades in China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 174, 121188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, Z.Y.; Hadi, J.; Chow, F.; Loh, D.J.; Konovessis, D. Big Data Analytics and Machine Learning of Harbour Craft Vessels to Achieve Fuel Efficiency: A Review. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, M.; Mompó Alepuz, A.; Thompson, F.; Mariani, P.; Galeazzi, R.; Krag, L.A. A Deep Learning Approach to Assist Sustainability of Demersal Trawling Operations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergasheva, A.; Akhmedov, F.; Abdusalomov, A.; Kim, W. Advancing Maritime Safety: Early Detection of Ship Fires through Computer Vision, Deep Learning Approaches, and Histogram Equalization Techniques. Fire 2024, 7, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Khalaf, O.I.; Ji, J.; Ouyang, Q. Ship Feature Recognition Methods for Deep Learning in Complex Marine Environments. Complex Intell. Syst. 2022, 8, 3881–3897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoropoulos, P.; Spandonidis, C.C.; Giannopoulos, F.; Fassois, S. A Deep Learning-Based Fault Detection Model for Optimization of Shipping Operations and Enhancement of Maritime Safety. Sensors 2021, 21, 5658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saafi, S.; Vikhrova, O.; Fodor, G.; Hosek, J.; Andreev, S. AI-Aided Integrated Terrestrial and Non-Terrestrial 6G Solutions for Sustainable Maritime Networking. IEEE Netw. 2022, 36, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Chen, L.; Shu, Y.; Zhu, W. Evaluation Model and Management Strategy for Reducing Pollution Caused by Ship Collision in Coastal Waters. Ocean. Coast Manag. 2021, 203, 105446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaei, S.R.; Ghahfarrokhi, M.A. Using Artificial Intelligence for Advanced Health Monitoring of Marine Vessels. In Proceedings of the 2th International Conference on Creative Achievements of Architecture, Urban Planning, Civil Engineering and Environment in the Sustainable Development of the Middle East, Mashhad, Iran, 1 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Durlik, I.; Miller, T.; Dorobczyński, L.; Kozlovska, P.; Kostecki, T. Revolutionizing Marine Traffic Management: A Comprehensive Review of Machine Learning Applications in Complex Maritime Systems. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, S.; Michaelides, M.P.; Herodotou, H. Internet of Ships: A Survey on Architectures, Emerging Applications, and Challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 9714–9727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catana, E.; Basaras, P.; Willenbrock, R. Enabling Innovation in Maritime Ports and the Need of the 6G Candidate Technologies: 5G-LOGINNOV Showcase. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 9th World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT), Aveiro, Portugal, 12 October 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, T.; Feng, W.; Chen, Y.; Wang, C.-X.; Ge, N.; Lu, J. Hybrid Satellite-Terrestrial Communication Networks for the Maritime Internet of Things: Key Technologies, Opportunities, and Challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 8910–8934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charpentier, V.; Slamnik-Kriještorac, N.; Landi, G.; Caenepeel, M.; Vasseur, O.; Marquez-Barja, J.M. Paving the Way towards Safer and More Efficient Maritime Industry with 5G and Beyond Edge Computing Systems. Comput. Netw. 2024, 250, 110499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Feng, H.; Gao, S.; Jiang, Z.; Qin, M.; Cheng, N.; Bai, L. Two-Stage Offloading Optimization for Energy–Latency Tradeoff With Mobile Edge Computing in Maritime Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 5954–5963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garro, E.; Lacalle, I.; Blanquer, F.; Ramos, A.; Martinez, A.; Sowiński, P.; Llorente, M.A.; Palau, C. Maritime Terminals’ Cargo Handling Equipment Cooperation Leveraging IoT and Edge Computing: The ASSIST-IoT Approach. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 2864–2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaklis, D.; Varlamis, I.; Giannakopoulos, G.; Varelas, T.J.; Spyropoulos, C.D. Enabling Digital Twins in the Maritime Sector through the Lens of AI and Industry 4.0. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2023, 3, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paternina-Arboleda, C.; Nestler, A.; Kascak, N.; Pour, M.S. Cybersecurity Considerations for the Design of an AI-Driven Distributed Optimization of Container Carbon Emissions Reduction for Freight Operations. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Logistics, Cham, Switzerland, 6 September 2023; pp. 56–84. [Google Scholar]

- Mahat, D.; Niranjan, K.; Naidu, C.S.K.V.R.; Babu, S.B.G.T.; Kumar, M.S.; Natrayan, L. AI-Driven Optimization of Supply Chain and Logistics in Mechanical Engineering. In Proceedings of the 2023 10th IEEE Uttar Pradesh Section International Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Computer Engineering (UPCON), Gautam Buddha Nagar, India, 1 December 2023; pp. 1611–1616. [Google Scholar]

- Katterbauer, K. Shipping of the Future-Cybersecurity Aspects for Autonomous AI-Driven Ships. Aust. N. Z. Marit. Law J. 2022, 36, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Dhaliwal, A. Towards AI-Driven Transport and Logistics. In Workshop on e-Business; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 119–131. [Google Scholar]

- Marineinsight.com. Available online: https://www.marineinsight.com/tech/how-ballast-water-treatment-system-works/#:~:text=Ozonation%20%E2%80%93%20Ozone%20gas%20is%20bubbled%20into%20the,used%20to%20kill%20organisms%20in%20the%20ballast%20water (accessed on 4 July 2024).

- Brandsæter, A.; Knutsen, K.E. Towards a Framework for Assurance of Autonomous Navigation Systems in the Maritime Industry. In Safety and Reliability–Safe Societies in a Changing World; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 449–457. [Google Scholar]

- Chondrodima, E.; Mandalis, P.; Pelekis, N.; Theodoridis, Y. Machine Learning Models for Vessel Route Forecasting: An Experimental Comparison. In Proceedings of the 2022 23rd IEEE International Conference on Mobile Data Management (MDM), Paphos, Cyprus, 6–9 June 2022; pp. 262–269. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, S.; Yang, Z. Towards Objective Human Performance Measurement for Maritime Safety: A New Psychophysiological Data-Driven Machine Learning Method. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 233, 109103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouzakitis, S.; Kontzinos, C.; Tsapelas, J.; Kanellou, I.; Kormpakis, G.; Kapsalis, P.; Askounis, D. Enabling Maritime Digitalization by Extreme-Scale Analytics, AI and Digital Twins: The Vesselai Architecture. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of SAI Intelligent Systems Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 7–8 September 2023; pp. 246–256. [Google Scholar]

- Tsolakis, N.; Zissis, D.; Papaefthimiou, S.; Korfiatis, N. Towards AI Driven Environmental Sustainability: An Application of Automated Logistics in Container Port Terminals. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 60, 4508–4528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iris, Ç.; Lam, J.S.L. A Review of Energy Efficiency in Ports: Operational Strategies, Technologies and Energy Management Systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 112, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiğit, K.; Acarkan, B. A New Ship Energy Management Algorithm to the Smart Electricity Grid System. Int. J. Energy Res. 2018, 42, 2741–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwala, P.; Chhabra, S.; Agarwala, N. Using Digitalisation to Achieve Decarbonisation in the Shipping Industry. J. Int. Marit. Saf. Environ. Aff. Shipp. 2021, 5, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalishin, P.; Nikitakos, N.; Svilicic, B.; Zhang, J.; Nikishin, A.; Dalaklis, D.; Kharitonov, M.; Stefanakou, A.-A. Using Artificial Intelligence (AI) Methods for Effectively Responding to Climate Change at Marine Ports. J. Int. Marit. Saf. Environ. Aff. Shipp. 2023, 7, 2186589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, J.P. The Long Shore: Archaeologies and Social Histories of California’s Maritime Cultural Landscapes; Meniketti, M., Ed.; Berghan Books: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. Xv + 219; ISBN 9781800738652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuge, D.; Dulebenets, M.A.; Fagerholt, K.; Wang, S. Editorial: Special Issue on “Green Port and Maritime Shipping”. Marit. Policy Manag. 2023, 50, 1027–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.S.; Davis, C.; Sandha, S.S.; Park, J.; Geronimo, J.; Garcia, L.A.; Srivastava, M.B. LocoMote: AI-Driven Sensor Tags for Fine-Grained Undersea Localization and Sensing. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 16999–17018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Roman, D.; Dickie, R.; Robu, V.; Flynn, D. Prognostics and Health Management for the Optimization of Marine Hybrid Energy Systems. Energies 2020, 13, 4676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Vanem, E.; Xue, Y.; Alnes, Ø.; Zhang, H.; Lam, J.; Bruvik, K. Data-Driven State of Health Monitoring for Maritime Battery Systems—A Case Study on Sensor Data from Ships in Operation. Ships Offshore Struct. 2023, 2023, 2211241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshua, S.R.; Yeon, A.N.; Park, S.; Kwon, K. Solar–Hydrogen Storage System: Architecture and Integration Design of University Energy Management Systems. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yuen, K.F. Blockchain Implementation in the Maritime Industry: Critical Success Factors and Strategy Formulation. Marit. Policy Manag. 2024, 51, 304–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, S.B.; Pambudi, D.S.A.; Ahmad, M.M.; Alfanda, B.D.; Imron, M.F.; Abdullah, S.R.S. Ecological Impacts of Ballast Water Loading and Discharge: Insight into the Toxicity and Accumulation of Disinfection by-Products. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, C.P.; Ravi Kumar, V.V.; Khurana, A. Artificial Intelligence Integration with the Supply Chain, Making It Green and Sustainable. In Proceedings of the 2023 7th International Conference on Electronics, Materials Engineering & Nano-Technology (IEMENTech), Kolkata, India, 18 December 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, L.; Liu, K.; He, J.; Han, C.; Liu, P. Carbon Emission Reduction Behavior Strategies in the Shipping Industry under Government Regulation: A Tripartite Evolutionary Game Analysis. J. Clean Prod. 2022, 378, 134556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsalhy, M.J.; Sharif, H.; Haroon, N.H.; Kadhim Mohsin, S.; Khalid, R.; Ali, A. Integrating AI-Based Smart-Driven Marketing to Promote Sustainable and Green Systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Emerging Research in Computational Science (ICERCS), Coimbatore, India, 7 December 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hossin, M.A.; Alemzero, D.; Wang, R.; Kamruzzaman, M.M.; Mhlanga, M.N. Examining Artificial Intelligence and Energy Efficiency in the MENA Region: The Dual Approach of DEA and SFA. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 4984–4994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Dong, B.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Liu, H.; Han, F. Analysis and Evaluation of Fuel Cell Technologies for Sustainable Ship Power: Energy Efficiency and Environmental Impact. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2024, 21, 100482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rout, S.; Samantaray, S. Smart Technologies for a Sustainable Future: IoT and AI in Renewable Energy. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Applied Electromagnetics, Signal Processing, & Communication (AESPC), Bhubaneswar, India, 24 November 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Farzadmehr, M.; Carlan, V.; Vanelslander, T. Designing a Survey Framework to Collect Port Stakeholders’ Insight Regarding AI Implementation: Results from the Flemish Context. J. Shipp. Trade 2023, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boute, R.N.; Udenio, M. AI in Logistics and Supply Chain Management. In Global Logistics and Supply Chain Strategies for the 2020s; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Farzadmehr, M.; Carlan, V.; Vanelslander, T. How AI Can Influence Efficiency of Port Operation Specifically Ship Arrival Process: Developing a Cost–Benefit Framework. WMU J. Marit. Aff. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewan, M.H.; Godina, R. Sailing Towards Sustainability: How Seafarers Embrace New Work Cultures for Energy Efficient Ship Operations in Maritime Industry. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 232, 1930–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allioui, H.; Allioui, A.; Mourdi, Y. Navigating Transformation: Unveiling the Synergy of IoT, Multimedia Trends, and AI for Sustainable Financial Growth in African Context. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xu, J.; Chen, Z. Research on Sustainability Evaluation of Green Building Engineering Based on Artificial Intelligence and Energy Consumption. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 11378–11391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjödin, D.; Parida, V.; Kohtamäki, M. Artificial Intelligence Enabling Circular Business Model Innovation in Digital Servitization: Conceptualizing Dynamic Capabilities, AI Capacities, Business Models and Effects. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 197, 122903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pribyl, S. Autonomous Vessels in the Era of Global Environmental Change. In Autonomous Vessels in Maritime Affairs: Law and Governance Implications; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 163–184. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Lee, C.; Park, S.; Lim, S. Potential Liability Issues of AI-Based Embedded Software in Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships for Maritime Safety in the Korean Maritime Industry. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autsadee, Y.; Jeevan, J.; Mohd Salleh, N.H.B.; Othman, M.R. Bin Digital Tools and Challenges in Human Resource Development and Its Potential within the Maritime Sector through Bibliometric Analysis. J. Int. Marit. Saf. Environ. Aff. Shipp. 2023, 7, 2286409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, I.; Perčić, M.; BahooToroody, A.; Fan, A.; Vladimir, N. Review of Research Progress of Autonomous and Unmanned Shipping and Identification of Future Research Directions. J. Mar. Eng. Technol. 2024, 23, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martelli, M.; Geertsma, R.D. Naval Engineering and Ship Control Special Edition III. J. Mar. Eng. Technol. 2024, 23, 155–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.-L.; Choi, T.-M. Logistics Management for the Future: The IJLRA Framework. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2023, 2023, 2286352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitch, E.; Andreas Alsos, O. A Systematic Review of Human-AI Interaction in Autonomous Ship Systems. Saf. Sci. 2022, 152, 105778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, T.A.; Glomsrud, J.A.; Ruud, E.-L.; Simonsen, A.; Sandrib, J.; Eriksen, B.-O.H. Towards Simulation-Based Verification of Autonomous Navigation Systems. Saf. Sci. 2020, 129, 104799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felski, A.; Zwolak, K. The Ocean-Going Autonomous Ship—Challenges and Threats. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijjahalli, S.; Sabatini, R.; Gardi, A. Advances in Intelligent and Autonomous Navigation Systems for Small UAS. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2020, 115, 100617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Lim, S. Development of an Interpretable Maritime Accident Prediction System Using Machine Learning Techniques. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 41313–41329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Joung, T.-H.; Jeong, B.; Park, H.-S. Autonomous Shipping and Its Impact on Regulations, Technologies, and Industries. J. Int. Marit. Saf. Environ. Aff. Shipp. 2020, 4, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Chu, X.; Wu, W.; Li, S.; He, Z.; Zheng, M.; Zhou, H.; Li, Z. Human–Machine Cooperation Research for Navigation of Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships: A Review and Consideration. Ocean. Eng. 2022, 246, 110555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojković, G.; Milenković, M. Autonomous Ships and Legal Authorities of the Ship Master. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2020, 8, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, Ü.; Akdağ, M.; Ayabakan, T. A Review of Path Planning Algorithms in Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships: Navigation Safety Perspective. Ocean. Eng. 2022, 251, 111010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichimura, Y.; Dalaklis, D.; Kitada, M.; Christodoulou, A. Shipping in the Era of Digitalization: Mapping the Future Strategic Plans of Major Maritime Commercial Actors. Digit. Bus. 2022, 2, 100022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallam, S.C.; Nazir, S.; Sharma, A. The Human Element in Future Maritime Operations—Perceived Impact of Autonomous Shipping. Ergonomics 2020, 63, 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NAVDEC—The first in the World Decision Making Tool for Navigation. navdec.com. Available online: https://navdec.com/en/ (accessed on 4 July 2024).

- Gu, Y.; Goez, J.C.; Guajardo, M.; Wallace, S.W. Autonomous Vessels: State of the Art and Potential Opportunities in Logistics. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2021, 28, 1706–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Logistics Technology Based on AI--New Direction of Logistics Development. In Proceedings of the Cyber Security Intelligence and Analytics: 2021 International Conference on Cyber Security Intelligence and Analytics (CSIA2021), Shenyang, China, 19–20 March 2021; pp. 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Richey, R.G.; Chowdhury, S.; Davis-Sramek, B.; Giannakis, M.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Artificial Intelligence in Logistics and Supply Chain Management: A Primer and Roadmap for Research. J. Bus. Logist. 2023, 44, 532–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, A.; Bhargava, D.; Kumar, P.N.; Sajja, G.S.; Ray, S. Industrial IoT and AI Implementation in Vehicular Logistics and Supply Chain Management for Vehicle Mediated Transportation Systems. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2022, 13, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toorajipour, R.; Sohrabpour, V.; Nazarpour, A.; Oghazi, P.; Fischl, M. Artificial Intelligence in Supply Chain Management: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Bus Res. 2021, 122, 502–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosso Wamba, S.; Queiroz, M.M.; Guthrie, C.; Braganza, A. Industry Experiences of Artificial Intelligence (AI): Benefits and Challenges in Operations and Supply Chain Management. Prod. Plan. Control. 2022, 33, 1493–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helo, P.; Hao, Y. Artificial Intelligence in Operations Management and Supply Chain Management: An Exploratory Case Study. Prod. Plan. Control. 2022, 33, 1573–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Shishodia, A.; Gunasekaran, A.; Min, H.; Munim, Z.H. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Supply Chain Management: Mapping the Territory. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 60, 7527–7550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, N.; Abd Elghany, M.; Abd Elghany, M. Exploratory Research on Digitalization Transformation Practices within Supply Chain Management Context in Developing Countries Specifically Egypt in the MENA Region. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1965459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugurusi, G.; Oluka, P.N. Towards Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) in Supply Chain Management: A Typology and Research Agenda. In Proceedings of the IFIP International Conference on Advances in Production Management Systems, Nantes, France, 5–9 September 2021; pp. 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kovač, M. Autonomous AI, Smart Seaports, and Supply Chain Management: Challenges and Risks. In Regulating Artificial Intelligence in Industry; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 127–137. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, M.K.; Bidanda, B.; Geunes, J.; Fernandes, K.; Dolgui, A. Supply Chain Digitisation and Management. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 2918–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Banna, A.; Rana, Z.A.; Yaqot, M.; Menezes, B. Interconnectedness between Supply Chain Resilience, Industry 4.0, and Investment. Logistics 2023, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrou, S.E.; Panayides, P.M.; Tsouknidis, D.A.; Alexandrou, A.E. Green Supply Chain Management Strategy and Financial Performance in the Shipping Industry. Marit. Policy Manag. 2022, 49, 376–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeniyurt, S.; Carnovale, S. Digitization in Supply Chain Management; World Scientific: Singapore, 2024; Volume 2, ISBN 978-981-12-8662-9. [Google Scholar]

- Khaoua, Y.; Mouzouna, Y.; Arif, J.; Jawab, F.; Azari, M. The Contribution of Blockchain Technology in the Supply Chain Management: The Shipping Industry as an Example. In Proceedings of the 2022 14th International Colloquium of Logistics and Supply Chain Management (LOGISTIQUA), El Jadida, Morocco, 25 May 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ceyhun, G.Ç. Recent Developments of Artificial Intelligence in Business Logistics: A Maritime Industry Case. In Digital Business Strategies in Blockchain Ecosystems: Transformational Design and Future of Global Business; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 343–353. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, J.; Zhou, F.; He, Y. Digital Technique-Enabled Container Logistics Supply Chain Sustainability Achievement. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, M.; Grøtli, E.I.; Mørkrid, O.E.; Tangstad, E.; Fossøy, S.; Nordahl, H. A Gap Analysis for Automated Cargo Handling Operations with Geared Vessels Frequenting Small Sized Ports. Marit. Transp. Res. 2023, 5, 100098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inutsuka, H.; Ichimura, K.; Sugimura, Y.; Yoshie, M.; Shinoda, T. Study on the Relationship between Port Governance and Terminal Operation System for Smart Port: Japan Case. Logistics 2024, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Chatterjee, I.; Cho, G. Enhancing Parking Facility of Container Drayage in Seaports: A Study on Integrating Computer Vision and AI. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 6th International Conference on Knowledge Innovation and Invention (ICKII), Sapporo, Japan, 11 August 2023; pp. 384–387. [Google Scholar]

- Nath, S.P.; Upadhyay, R.K. Reformation and Optimization of Cargo Handling Operation at Indian Air Cargo Terminals. J. Air Transp. Res. Soc. 2024, 2, 100022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Chatterjee, I.; Cho, G. A Systematic Review of Computer Vision and AI in Parking Space Allocation in a Seaport. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, S.; Herodotou, H.; Garro, E.; MartÎnez-Romero, Á.; Burgos, M.A.; Cassera, A.; Papas, G.; Dias, P.; Michaelides, M.P. Emerging IoT Applications and Architectures for Smart Maritime Container Terminals. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 9th World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT), Aveiro, Portugal, 12 October 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Aslam, S.; Herodotou, H.; Garro, E.; Romero, A.M.; Burgos, M.A.; Cassera, A.; Papas, G.; Dias, P.; Michaelides, M. IoT for the Maritime Industry: Challenges and Emerging Applications. In Proceedings of the 2023 18th Conference on Computer Science and Intelligence Systems (FedCSIS), Warsaw, Poland, 26 September 2023; pp. 855–858. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, G.; Xiong, K.; Zhong, Z.; Ai, B. Internet of Things for High-Speed Railways. Intell. Converg. Netw. 2021, 2, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gostomski, E.; Nowosielski, T.; Miler, R.K. Containerization in Maritime Transport; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; ISBN 9781003330127. [Google Scholar]

- Vinh, N.Q.; Kim, H.-S.; Long, L.N.B.; You, S.-S. Robust Lane Detection Algorithm for Autonomous Trucks in Container Terminals. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Hu, Q.; Zhou, M.; Zun, Z.; Qian, X. Multi-Aspect Applications and Development Challenges of Digital Twin-Driven Management in Global Smart Ports. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2021, 9, 1298–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, E.; Watanabe, D.; Lambrou, M.; Banyai, T.; Banyai, A.; Kaczmar, I. Shipping Digitalization and Automation for the Smart Port. In Supply Chain-Recent Advances and New Perspectives in the Industry 4.0 Era; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, T.; Zhang, D.; Huang, C.; Zhang, H.; Dai, N.; Song, Y.; Chen, H. Artificial Intelligence in Sustainable Energy Industry: Status Quo, Challenges and Opportunities. J. Clean Prod. 2021, 289, 125834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braidotti, L.; Mazzarino, M.; Cociancich, M.; Bucci, V. On the Automation of Ports and Logistics Chains in the Adriatic Region. In Proceedings of the Computational Science and Its Applications–ICCSA 2020: 20th International Conference, Cagliari, Italy, 1–4 July 2020; pp. 96–111. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, K.; Song, D.-W. Maritime Logistics for the Next Decade: Challenges, Opportunities and Required Skills. In Global Logistics and Supply Chain Strategies for the 2020s; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 151–174. [Google Scholar]

- Bottalico, A. The Logistics Labor Market in the Context of Digitalization: Trends, Issues and Perspectives. In Digital Supply Chains and the Human Factor; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo González, A.; González-Cancelas, N.; Molina Serrano, B.; Orive, A. Preparation of a Smart Port Indicator and Calculation of a Ranking for the Spanish Port System. Logistics 2020, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senarak, C.; Mokkhavas, O. 4.0 Technology for Port Digitalization and Automation. In Handbook of Smart Materials, Technologies, and Devices; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1307–1320. [Google Scholar]

- Camarero Orive, A.; Santiago, J.I.P.; Corral, M.M.E.-I.; González-Cancelas, N. Strategic Analysis of the Automation of Container Port Terminals through BOT (Business Observation Tool). Logistics 2020, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Zhang, X.; Lu, J.; Liu, F.; Fan, Y. Research on Ecological Evaluation of Shanghai Port Logistics Based on Emergy Ecological Footprint Models. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 139, 108916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Li, H. Silicon Energy Bulk Material Cargo Ship Detection and Tracking Method Combining YOLOv5 and DeepSort. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K.; Rani, A.; Bakhariya, H.; Kumar, R.; Tomar, D.; Ghosh, S. The Role of IoT in Optimizing Operations in the Oil and Gas Sector: A Review. Trans. Indian Natl. Acad. Eng. 2024, 9, 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, N.; Wu, S.; Wang, X.; Yin, Z.; Li, C.; Chen, W.; Chen, F. AI for UAV-Assisted IoT Applications: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 14438–14461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Jaglan, P.; Kakde, Y. Aerial Imaging Rescue and Integrated System for Road Monitoring Based on AI/ML. In Advances in Aerial Sensing and Imaging; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 47–67. [Google Scholar]

- Balfaqih, M.; Balfagih, Z.; Lytras, M.D.; Alfawaz, K.M.; Alshdadi, A.A.; Alsolami, E. A Blockchain-Enabled IoT Logistics System for Efficient Tracking and Management of High-Price Shipments: A Resilient, Scalable and Sustainable Approach to Smart Cities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lun, Y.H.V.; Lai, K.; Cheng, T.C.E.; Yang, D. New Technology Development in the Shipping Industry. In Shipping and Logistics Management; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 257–279. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Driscol, J.; Sarigai, S.; Wu, Q.; Lippitt, C.D.; Morgan, M. Towards Synoptic Water Monitoring Systems: A Review of AI Methods for Automating Water Body Detection and Water Quality Monitoring Using Remote Sensing. Sensors 2022, 22, 2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asha, P.; Natrayan, L.; Geetha, B.T.; Beulah, J.R.; Sumathy, R.; Varalakshmi, G.; Neelakandan, S. IoT Enabled Environmental Toxicology for Air Pollution Monitoring Using AI Techniques. Environ. Res. 2022, 205, 112574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaginalkar, A.; Kumar, S.; Gargava, P.; Niyogi, D. Review of Urban Computing in Air Quality Management as Smart City Service: An Integrated IoT, AI, and Cloud Technology Perspective. Urban Clim. 2021, 39, 100972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakholia, R.; Le, Q.; Vu, K.; Ho, B.Q.; Carbajo, R.S. AI-Based Air Quality PM2.5 Forecasting Models for Developing Countries: A Case Study of Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Urban Clim. 2022, 46, 101315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Dahiya, M.; Kumar, R.; Nanda, C. Sensors and Systems for Air Quality Assessment Monitoring and Management: A Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 289, 112510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-H.; Chen, W.-T.; Chang, Y.-C.; Wu, K.-T.; Wang, R.-H. ETAUS: An Edge and Trustworthy AI UAV System with Self-Adaptivity for Air Quality Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Detroit, MI, USA, 1 October 2023; pp. 6253–6260. [Google Scholar]

- Bainomugisha, E.; Adrine Warigo, P.; Busigu Daka, F.; Nshimye, A.; Birungi, M.; Okure, D. AI-Driven Environmental Sensor Networks and Digital Platforms for Urban Air Pollution Monitoring and Modelling. Soc. Impacts 2024, 3, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William, P.; Ramu, G.; Kansal, L.; Patil, P.P.; Alkhayyat, A.; Rao, A.K. Artificial Intelligence Based Air Quality Monitoring System with Modernized Environmental Safety of Sustainable Development. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Social Networking (ICPCSN), Salem, India, 19–20 June 2023; pp. 756–761. [Google Scholar]

- Felici-Castell, S.; Segura-Garcia, J.; Perez-Solano, J.J.; Fayos-Jordan, R.; Soriano-Asensi, A.; Alcaraz-Calero, J.M. AI-IoT Low-Cost Pollution-Monitoring Sensor Network to Assist Citizens with Respiratory Problems. Sensors 2023, 23, 9585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, V.; Ashraf, N.; Khalid, M.; Walvekar, R.; Yang, Y.; Kaushik, A.; Mishra, Y.K. Emergence of MXene–Polymer Hybrid Nanocomposites as High-Performance Next-Generation Chemiresistors for Efficient Air Quality Monitoring. Adv. Funct. Mater 2022, 32, 2112913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ighalo, J.O.; Adeniyi, A.G.; Marques, G. Internet of Things for Water Quality Monitoring and Assessment: A Comprehensive Review. In Artificial Intelligence for Sustainable Development: Theory, Practice and Future Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 245–259. [Google Scholar]

- Mandal, A.; Ghosh, A.R. Role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Fish Growth and Health Status Monitoring: A Review on Sustainable Aquaculture. Aquac. Int. 2024, 32, 2791–2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saboe, D.; Ghasemi, H.; Gao, M.M.; Samardzic, M.; Hristovski, K.D.; Boscovic, D.; Burge, S.R.; Burge, R.G.; Hoffman, D.A. Real-Time Monitoring and Prediction of Water Quality Parameters and Algae Concentrations Using Microbial Potentiometric Sensor Signals and Machine Learning Tools. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 764, 142876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ighalo, J.O.; Adeniyi, A.G.; Marques, G. Artificial Intelligence for Surface Water Quality Monitoring and Assessment: A Systematic Literature Analysis. Model Earth Syst. Environ. 2021, 7, 669–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geetha, M.; Bonthula, S.; Al-Maadeed, S.; Al-Lohedan, H.; Rajabathar, J.R.; Arokiyaraj, S.; Sadasivuni, K.K. Research Trends in Smart Cost-Effective Water Quality Monitoring and Modeling: Special Focus on Artificial Intelligence. Water 2023, 15, 3293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valavi, R.; Guillera-Arroita, G.; Lahoz-Monfort, J.J.; Elith, J. Predictive Performance of Presence-only Species Distribution Models: A Benchmark Study with Reproducible Code. Ecol. Monogr. 2022, 92, e01486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Farah, M.A.; Ukwandu, E.; Hindy, H.; Brosset, D.; Bures, M.; Andonovic, I.; Bellekens, X. Cyber Security in the Maritime Industry: A Systematic Survey of Recent Advances and Future Trends. Information 2022, 13, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Jiang, X.; Yu, J.; Tam, V.W.Y.; Skitmore, M. Integration of Life Cycle Assessment and Life Cycle Cost Using Building Information Modeling: A Critical Review. J. Clean Prod. 2021, 285, 125438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasani, A.A.; Esmaeili, A.; Golzary, A. Software Tools for Microalgae Biorefineries: Cultivation, Separation, Conversion Process Integration, Modeling, and Optimization. Algal. Res. 2022, 61, 102597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Anand, A.; Shukla, A.; Kumar, A.; Buddhi, D.; Sharma, A. A Comprehensive Overview on Solar Grapes Drying: Modeling, Energy, Environmental and Economic Analysis. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2021, 47, 101513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Guest, J.S. BioSTEAM-LCA: An Integrated Modeling Framework for Agile Life Cycle Assessment of Biorefineries under Uncertainty. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 18903–18914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doukas, H.; Nikas, A. Decision Support Models in Climate Policy. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 280, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.T.; Pincock, D.; Baumgart, D.C.; Sadowski, D.C.; Fedorak, R.N.; Kroeker, K.I. An Overview of Clinical Decision Support Systems: Benefits, Risks, and Strategies for Success. NPJ Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, D.; Tran Tuan, V.; Quoc Tran, D.; Park, M.; Park, S. Conceptual Framework of an Intelligent Decision Support System for Smart City Disaster Management. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadi, A.M.; Du, Y.; Guendouz, Y.; Wei, L.; Mazo, C.; Becker, B.A.; Mooney, C. Current Challenges and Future Opportunities for XAI in Machine Learning-Based Clinical Decision Support Systems: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Mina, H.; Alavi, B. A Decision Support System for Demand Management in Healthcare Supply Chains Considering the Epidemic Outbreaks: A Case Study of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Transp. Res. E Logist Transp. Rev. 2020, 138, 101967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.; Anderson, K.; Miller, B.; Boyer, K.; Warren, A. Microgrid Resilience: A Holistic Approach for Assessing Threats, Identifying Vulnerabilities, and Designing Corresponding Mitigation Strategies. Appl. Energy 2020, 264, 114726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Elmi, Z.; Lau, Y.; Borowska-Stefańska, M.; Wiśniewski, S.; Dulebenets, M.A. Blockchain and AI Technology Convergence: Applications in Transportation Systems. Veh. Commun. 2022, 38, 100521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.-Y.; Chhetri, P.; Ye, G.; Lee, P.T.-W. Green Maritime Logistics Coalition by Green Shipping Corridors: A New Paradigm for the Decarbonisation of the Maritime Industry. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2023, 2023, 2256243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaucha, J.; Kreiner, A. Engagement of Stakeholders in the Marine/Maritime Spatial Planning Process. Mar. Policy 2021, 132, 103394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmay, F.K.; Salah, K.; Jayaraman, R.; Omar, I.A. Using NFTs and Blockchain for Traceability and Auctioning of Shipping Containers and Cargo in Maritime Industry. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 124507–124522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, I.; Abido, M.A.; Khalid, M.; Savkin, A.V. A Comprehensive Review of Recent Advances in Smart Grids: A Sustainable Future with Renewable Energy Resources. Energies 2020, 13, 6269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, N.; Ramadan, H.S.M.; Elfarouk, O. Renewable Energy Management in Smart Grids by Using Big Data Analytics and Machine Learning. Mach. Learn. Appl. 2022, 9, 100363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.I.; Jhanjhi, N.Z.; Humayun, M.; Sivanesan, S.; Masud, M.; Hossain, M.S. Hybrid Smart Grid with Sustainable Energy Efficient Resources for Smart Cities. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2021, 46, 101211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ourahou, M.; Ayrir, W.; EL Hassouni, B.; Haddi, A. Review on Smart Grid Control and Reliability in Presence of Renewable Energies: Challenges and Prospects. Math Comput. Simul. 2020, 167, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Shahid, Z.; Alam, M.M.; Bakar Sajak, A.A.; Mazliham, M.S.; Khan, T.A.; Ali Rizvi, S.S. Energy Management Systems Using Smart Grids: An Exhaustive Parametric Comprehensive Analysis of Existing Trends, Significance, Opportunities, and Challenges. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 2022, 2022, 3358795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.U.; Wadud, Z.; Elavarasan, R.M.; Hafeez, G.; Khan, I.; Shafiq, Z.; Alhelou, H.H. An Optimal Power Usage Scheduling in Smart Grid Integrated With Renewable Energy Sources for Energy Management. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 84619–84638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamnatou, C.; Chemisana, D.; Cristofari, C. Smart Grids and Smart Technologies in Relation to Photovoltaics, Storage Systems, Buildings and the Environment. Renew Energy 2022, 185, 1376–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herazo, J.C.M.; Castillo, A.P.P.; Eras, J.J.C.; Fierro, T.E.S.; Araújo, J.F.C.; Gatica, G. Bibliometric Analysis of Energy Management and Efficiency in the Maritime Industry and Port Terminals: Trends. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 231, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimica, M.; Perčić, M.; Vladimir, N.; Krajačić, G. Cross-Sectoral Integration for Increased Penetration of Renewable Energy Sources in the Energy System—Unlocking the Flexibility Potential of Maritime Transport Electrification. Smart Energy 2022, 8, 100089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacek, C.G.; Gimbel, D.J.; Longo, S.J.; Mendel, B.I.; Sampaio, G.N.; Polmateer, T.L.; Manasco, M.C.; Hendrickson, D.C.; Eddy, T.L.; Lambert, J.H. Managing Operational and Environmental Risks in the Strategic Plan of a Maritime Container Port. In Proceedings of the 2021 Systems and Information Engineering Design Symposium (SIEDS), Charlottesville, VA, USA, 30 April 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Si Mohammed, K.; Nassani, A.A.; Sarkodie, S.A. Assessing the Effect of the Aquaculture Industry, Renewable Energy, Blue R&D, and Maritime Transport on GHG Emissions in Ireland and Norway. Aquaculture 2024, 586, 740769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mızrak, F.; Akkartal, G.R. An Analysis of Alternative Energy Sources and Applications in Maritime Transportation with a Strategic Management Approach; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Kołakowski, P.; Gil, M.; Wróbel, K.; Ho, Y.-S. State of Play in Technology and Legal Framework of Alternative Marine Fuels and Renewable Energy Systems: A Bibliometric Analysis. Marit. Policy Manag. 2022, 49, 236–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andeobu, L.; Wibowo, S.; Grandhi, S. Artificial Intelligence Applications for Sustainable Solid Waste Management Practices in Australia: A Systematic Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 834, 155389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olawade, D.B.; Fapohunda, O.; Wada, O.Z.; Usman, S.O.; Ige, A.O.; Ajisafe, O.; Oladapo, B.I. Smart Waste Management: A Paradigm Shift Enabled by Artificial Intelligence. Waste Manag. Bull. 2024, 2, 244–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihsanullah, I.; Alam, G.; Jamal, A.; Shaik, F. Recent Advances in Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Solid Waste Management: A Review. Chemosphere 2022, 309, 136631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernat, K. Post-Consumer Plastic Waste Management: From Collection and Sortation to Mechanical Recycling. Energies 2023, 16, 3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, T.A.; Meidiana, C.; Goh, H.H.; Zhang, D.; Othman, M.H.D.; Aziz, F.; Anouzla, A.; Sarangi, P.K.; Pasaribu, B.; Ali, I. Unlocking Synergies between Waste Management and Climate Change Mitigation to Accelerate Decarbonization through Circular-Economy Digitalization in Indonesia. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 46, 522–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, I.; Haque, A.K.M.M.; Ullah, S.M.A. Assessing Sustainable Waste Management Practices in Rajshahi City Corporation: An Analysis for Local Government Enhancement Using IoT, AI, and Android Technology. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiurova, A.; Kurniawan, T.A.; Kustikova, M.; Bykovskaia, E.; Othman, M.H.D.; Singh, D.; Goh, H.H. Promoting Digital Transformation in Waste Collection Service and Waste Recycling in Moscow (Russia): Applying a Circular Economy Paradigm to Mitigate Climate Change Impacts on the Environment. J. Clean Prod. 2022, 354, 131604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkinay Ozdemir, M.; Ali, Z.; Subeshan, B.; Asmatulu, E. Applying Machine Learning Approach in Recycling. J. Mater Cycles Waste Manag. 2021, 23, 855–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H. Developing a Smart Port Architecture and Essential Elements in the Era of Industry 4.0. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2022, 24, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campisi, T.; Marinello, S.; Costantini, G.; Laghi, L.; Mascia, S.; Matteucci, F.; Serrau, D. Locally Integrated Partnership as a Tool to Implement a Smart Port Management Strategy: The Case of the Port of Ravenna (Italy). Ocean. Coast Manag. 2022, 224, 106179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmoukari, B.; Audy, J.-F.; Forget, P. Smart Port: A Systematic Literature Review. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2023, 15, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, A.; El-gazzar, S.; Knez, M. A Framework for Adopting a Sustainable Smart Sea Port Index. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behdani, B. Port 4.0: A Conceptual Model for Smart Port Digitalization. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 74, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, T.; Williams, I.; Preston, J.; Clarke, N.; Odum, M.; O’Gorman, S. A Virtuous Circle? Increasing Local Benefits from Ports by Adopting Circular Economy Principles. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faut, L.; Soyeur, F.; Haezendonck, E.; Dooms, M.; de Langen, P.W. Ensuring Circular Strategy Implementation: The Development of Circular Economy Indicators for Ports. Marit. Transp. Res. 2023, 4, 100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haezendonck, E.; Van den Berghe, K. Patterns of Circular Transition: What Is the Circular Economy Maturity of Belgian Ports? Sustainability 2020, 12, 9269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimpour, R.; Ballini, F.; Ölcer, A.I. Port-City Redevelopment and the Circular Economy Agenda in Europe. In European Port Cities in Transition: Moving Towards More Sustainable Sea Transport Hubs; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Brouer, B.D.; Karsten, C.V.; Pisinger, D. Big Data Optimization in Maritime Logistics. In Big data optimization: Recent developments and challenges; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 319–344. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, X.; Li, W.; Xu, Y. Port Planning and Sustainable Development Based on Prediction Modelling of Port Throughput: A Case Study of the Deep-Water Dongjiakou Port. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellsolà Olba, X.; Daamen, W.; Vellinga, T.; Hoogendoorn, S.P. Multi-Criteria Evaluation of Vessel Traffic for Port Assessment: A Case Study of the Port of Rotterdam. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2019, 7, 871–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paridaens, H.; Notteboom, T. Logistics Integration Strategies in Container Shipping: A Multiple Case-Study on Maersk Line, MSC and CMA CGM. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2022, 45, 100868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.-G.; Kim, T.; Kim, B.-R.; Lee, M.-K. A Study on the Development Priority of Smart Shipping Items—Focusing on the Expert Survey. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.; Yeung, J.K.-W.; Lau, Y.-Y.; Kawasaki, T. A Case Study of How Maersk Adopts Cloud-Based Blockchain Integrated with Machine Learning for Sustainable Practices. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, R.; Kiwelekar, A.W.; Netak, L.D. AI-Based Techniques for Smart Ships. In Smart Ships; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, F.; Liu, J.; Zhu, H.; Yang, X.; Fan, Y. A Real-Time Measurement-Modeling System for Ship Air Pollution Emission Factors. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Roy, W.; Scheldeman, K.; Van Nieuwenhove, A.; Merveille, J.-B.; Schallier, R.; Maes, F. Current Progress in Developing a MARPOL Annex VI Enforcement Strategy in the Bonn Agreement through Remote Measurements. Mar. Policy 2023, 158, 105882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramowicz-Gerigk, T.; Burciu, Z.; Gerigk, M.K.; Jachowski, J. Monitoring of Ship Operations in Seaport Areas in the Sustainable Development of Ocean–Land Connections. Sustainability 2024, 16, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Peña Zarzuelo, I.; Freire Soeane, M.J.; López Bermúdez, B. Industry 4.0 in the Port and Maritime Industry: A Literature Review. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2020, 20, 100173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Chatterjee, I.; Cho, G. AI-Powered Intelligent Seaport Mobility: Enhancing Container Drayage Efficiency through Computer Vision and Deep Learning. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negenborn, R.R.; Goerlandt, F.; Johansen, T.A.; Slaets, P.; Valdez Banda, O.A.; Vanelslander, T.; Ventikos, N.P. Autonomous Ships Are on the Horizon: Here’s What We Need to Know. Nature 2023, 615, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B. Case Analysis of Environmental Coordinated Development of Domestic and Foreign Port Clusters. In The Sustainable Development of Port Group; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2024; pp. 257–279. [Google Scholar]

- Alamoush, A.S.; Ballini, F.; Ölçer, A.I. Revisiting Port Sustainability as a Foundation for the Implementation of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs). J. Shipp. Trade 2021, 6, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, G.; Szopik-Depczyńska, K.; Dembińska, I.; Ioppolo, G. Smart and Sustainable Logistics of Port Cities: A Framework for Comprehending Enabling Factors, Domains and Goals. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 69, 102801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugler, M.; Brandenburg, M.; Limant, S. Automizing the Manual Link in Maritime Supply Chains? An Analysis of Twistlock Handling Automation in Container Terminals. Marit. Transp. Res. 2021, 2, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunila, O.-P.; Kunnaala-Hyrkki, V.; Inkinen, T. Hindrances in Port Digitalization? Identifying Problems in Adoption and Implementation. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2021, 13, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D.; Blanche, J.; Harper, S.; Lim, T.; Gupta, R.; Zaki, O.; Tang, W.; Robu, V.; Watson, S.; Flynn, D. A Review: Challenges and Opportunities for Artificial Intelligence and Robotics in the Offshore Wind Sector. Energy AI 2022, 8, 100146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, S.; Lam, J.S.L. Blockchain Adoptions in the Maritime Industry: A Conceptual Framework. Marit. Policy Manag. 2021, 48, 777–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balci, G.; Surucu-Balci, E. Blockchain Adoption in the Maritime Supply Chain: Examining Barriers and Salient Stakeholders in Containerized International Trade. Transp. Res. E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2021, 156, 102539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jović, M.; Tijan, E.; Brčić, D.; Pucihar, A. Digitalization in Maritime Transport and Seaports: Bibliometric, Content and Thematic Analysis. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, T.; Lagdami, K.; Schröder-Hinrichs, J.-U. Assessing Innovation in Transport: An Application of the Technology Adoption (TechAdo) Model to Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships (MASS). Transp. Policy 2021, 114, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga-Lamas, P.; Lopes, S.I.; Fernández-Caramés, T.M. Green IoT and Edge AI as Key Technological Enablers for a Sustainable Digital Transition towards a Smart Circular Economy: An Industry 5.0 Use Case. Sensors 2021, 21, 5745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukaki, T.; Tei, A. Innovation and Maritime Transport: A Systematic Review. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2020, 8, 700–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza-Hernández, M.; Gil-González, A.B.; Rodríguez-González, S.; Prieto-Tejedor, J.; Corchado-Rodríguez, J.M. Integration of IoT Technologies in the Maritime Industry. In Proceedings of the Distributed Computing and Artificial Intelligence, Special Sessions, 17th International Conference, L’Aquila, Italy, 19 June 2021; pp. 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Bavassano, G.; Ferrari, C.; Tei, A. Blockchain: How Shipping Industry Is Dealing with the Ultimate Technological Leap. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2020, 34, 100428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Soh, Y.S.; Loh, H.S.; Yuen, K.F. The Key Challenges and Critical Success Factors of Blockchain Implementation: Policy Implications for Singapore’s Maritime Industry. Mar. Policy 2020, 122, 104265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishant, R.; Kennedy, M.; Corbett, J. Artificial Intelligence for Sustainability: Challenges, Opportunities, and a Research Agenda. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 53, 102104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-J.; Raghavendra, R.; Gupta, U.; Acun, B.; Ardalani, N.; Maeng, K.; Chang, G.; Aga, F.; Huang, J.; Bai, C. Sustainable Ai: Environmental Implications, Challenges and Opportunities. Proc. Mach. Learn. Syst. 2022, 4, 795–813. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, R.W.; Hasan, H.; Jayaraman, R.; Salah, K.; Omar, M. Blockchain Applications and Architectures for Port Operations and Logistics Management. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2021, 41, 100620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goralski, M.A.; Tan, T.K. Artificial Intelligence and Sustainable Development. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2020, 18, 100330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, F.; Ahmed, W.; Akbar, A.; Aslam, F.; Alyousef, R. Predictive Modeling for Sustainable High-Performance Concrete from Industrial Wastes: A Comparison and Optimization of Models Using Ensemble Learners. J. Clean Prod. 2021, 292, 126032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomares, I.; Martínez-Cámara, E.; Montes, R.; García-Moral, P.; Chiachio, M.; Chiachio, J.; Alonso, S.; Melero, F.J.; Molina, D.; Fernández, B.; et al. A Panoramic View and Swot Analysis of Artificial Intelligence for Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030: Progress and Prospects. Appl. Intell. 2021, 51, 6497–6527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Mehmood, R.; Corchado, J.M. Green Artificial Intelligence: Towards an Efficient, Sustainable and Equitable Technology for Smart Cities and Futures. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oloruntobi, O.; Mokhtar, K.; Gohari, A.; Asif, S.; Chuah, L.F. Sustainable Transition towards Greener and Cleaner Seaborne Shipping Industry: Challenges and Opportunities. Clean Eng. Technol. 2023, 13, 100628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; Yang, D.; Xu, L.; Li, J.; Jiang, Z. The Application of Artificial Intelligence Technology in Shipping: A Bibliometric Review. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallouppas, G.; Yfantis, E.A. Decarbonization in Shipping Industry: A Review of Research, Technology Development, and Innovation Proposals. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, M.; Ward, R.; Jensen, H.H.; Chua, C.P.; Simha, A.; Karlsson, J.; Göthberg, L.; Penttinen, T.; Theodosiou, D.P. The Future of Shipping: Collaboration Through Digital Data Sharing. In Maritime Informatics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 137–149. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, H.-T.; Lo, T.-M.; Pan, C.-L. Knowledge Mapping Analysis of Intelligent Ports: Research Facing Global Value Chain Challenges. Systems 2023, 11, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkilä, M.; Saarni, J.; Saurama, A. Innovation in Smart Ports: Future Directions of Digitalization in Container Ports. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| AI Technology | Description | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning | Algorithms that learn from data to make predictions or decisions [68,69]. | Fuel optimization [70], predictive maintenance [57] |

| Deep Learning | A subset of machine learning involving neural networks with many layers [71,72]. | Image recognition for cargo inspection [73], navigation systems [74]. |

| Reinforcement Learning | Learning method where an agent learns by interacting with its environment [75,76]. | Autonomous shipping [77], route optimization [78]. |

| Internet of Things (IoT) | Network of physical devices that collect and exchange data [79]. | Real-time monitoring, environmental sensors [80,81]. |

| Edge Computing | Processing data near the source of data generation rather than in a centralized data-processing warehouse [82]. | Real-time data processing on ships, ports [83,84]. |

| Predictive Analytics | Analyzing current and historical facts to make predictions about future events [44,85]. | Predictive maintenance, demand forecasting [78]. |

| Benefit | Description | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Emission Reduction | AI optimizes fuel usage and reduces unnecessary emissions [107,108]. | Lower greenhouse gas emissions [109]. |

| Energy Efficiency | AI-driven route optimization and smart energy management systems improve efficiency [110,111]. | Reduced fuel consumption and operational costs [112,113] |

| Operational Efficiency | AI enhances logistics and supply chain management through automation and predictive analytics [114]. | Faster, more reliable deliveries; reduced downtime [115,116]. |

| Maintenance Savings | Predictive maintenance reduces unexpected failures and extends equipment lifespan [117,118]. | Lower maintenance costs, increased reliability [119,120]. |

| Regulatory Compliance | AI helps monitor and ensure compliance with environmental regulations [121,122]. | Avoidance of fines, improved regulatory relations [123]. |

| Case Study | Company/Project | AI Technology Used | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case Study 1: AI in Shipping [47,70,244] | Maersk Line | Fuel optimization, predictive maintenance | Reduced fuel consumption, lowered CO2 emissions, improved maintenance practices |

| Case Study 2: AI in Environmental Monitoring [245,246] | Port of Rotterdam | Air and water quality monitoring, predictive models | Enhanced environmental monitoring, showed rapid response to pollution events, complied with regulations |

| Challenge | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| High Implementation Costs | Significant investment required for AI infrastructure and skilled personnel [261] | Cost of sensors, data storage, computing power |

| Data Privacy and Security | Ensuring the protection of sensitive data and compliance with data regulations [199] | Handling of operational and proprietary data |

| Shortage of Skilled Personnel | Lack of professionals with expertise in AI, data science, and machine learning [262] | Difficulty in hiring and retaining talent |

| Technical Barriers | Integration with legacy systems and ensuring data quality and availability (Munim I in 2020). | Compatibility issues, fragmented data |

| Connectivity Issues | Limited connectivity in remote maritime operations affecting real-time data transmission [45]. | Challenges in data transmission and system functionality |

| Regulatory and Standardization | Variability in international regulations and lack of standardization in AI technologies [263] | Compliance with safety, security, and environmental regulations |

| Opportunity | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Advanced Machine Learning Algorithms | Enhanced prediction and decision-making capabilities with advanced AI methods | Deep learning, reinforcement learning, neural networks for optimizing maritime operations |

| IoT Integration | Development of sophisticated and interconnected systems | Real-time data from ships, ports, and cargo containers; optimization of operations and maintenance |

| Edge Computing | Local data processing to address connectivity issues | Reduced latency, real-time decision making, enhanced reliability in remote maritime environments |

| Green Technologies | Development and implementation of sustainable practices | Alternative fuels (hydrogen and ammonia), hybrid propulsion systems, optimization of fuel consumption |

| Circular Economy Initiatives | Optimization of resource use and waste management | Enhanced recycling, reuse of materials, turning waste into valuable resources |

| Long-term Cost Savings | Significant reduction in operational expenses | Improved fuel efficiency, reduced maintenance costs, optimized operations |

| Competitive Advantage | Early adoption leading to market leadership | Offering more efficient, reliable, and sustainable services; increased market share and profitability |

| Industry Collaboration | Shared knowledge and best practices to drive AI adoption | Public–private partnerships, joint research and development, standardization of AI technologies |