Sleep Disorder Prevalence among Brazilian Children and Adolescents with Down Syndrome: An Observational Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

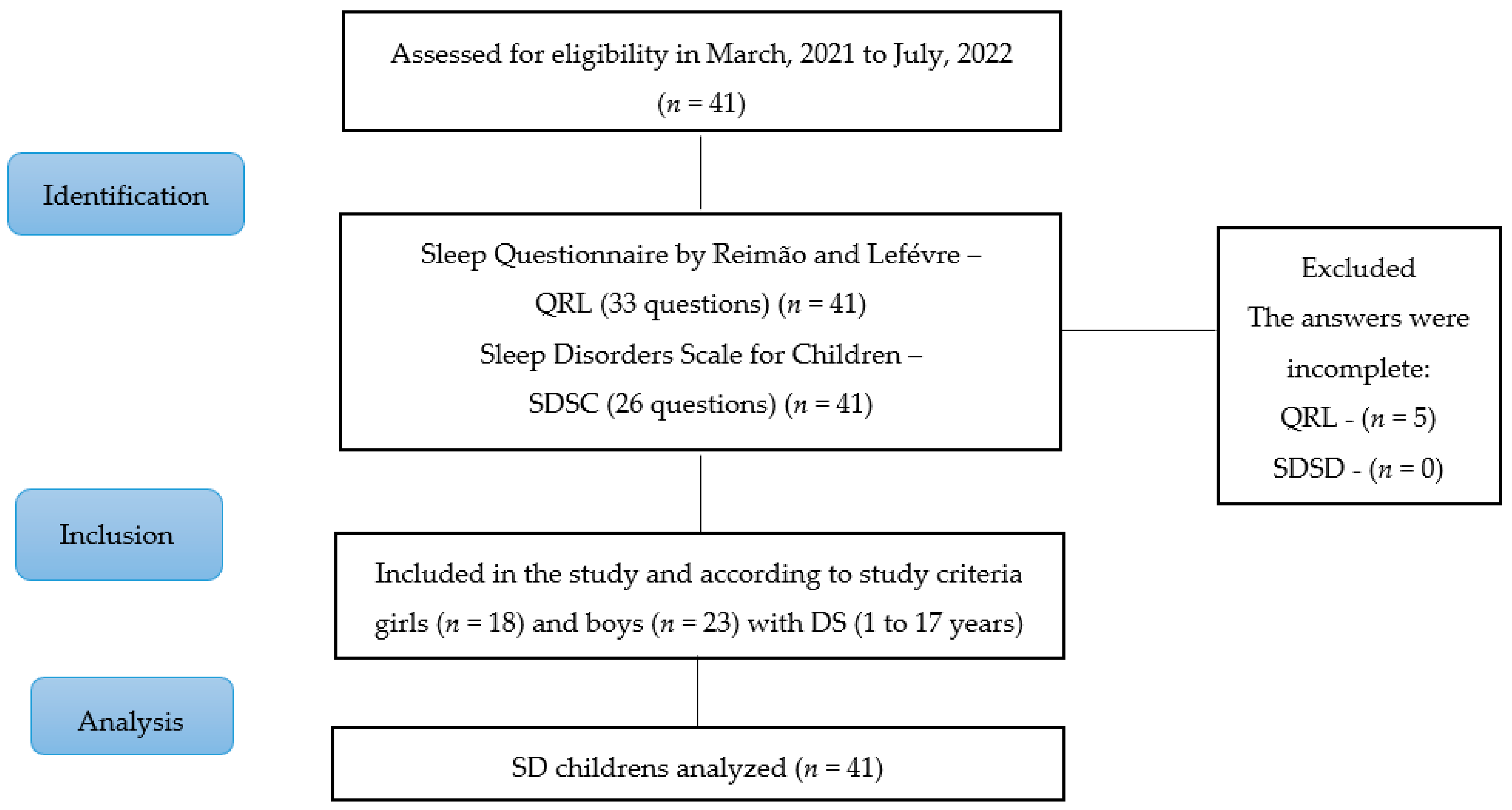

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics of Questions and Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Technical Information about the Sleep Disturbance Assessment Tools

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

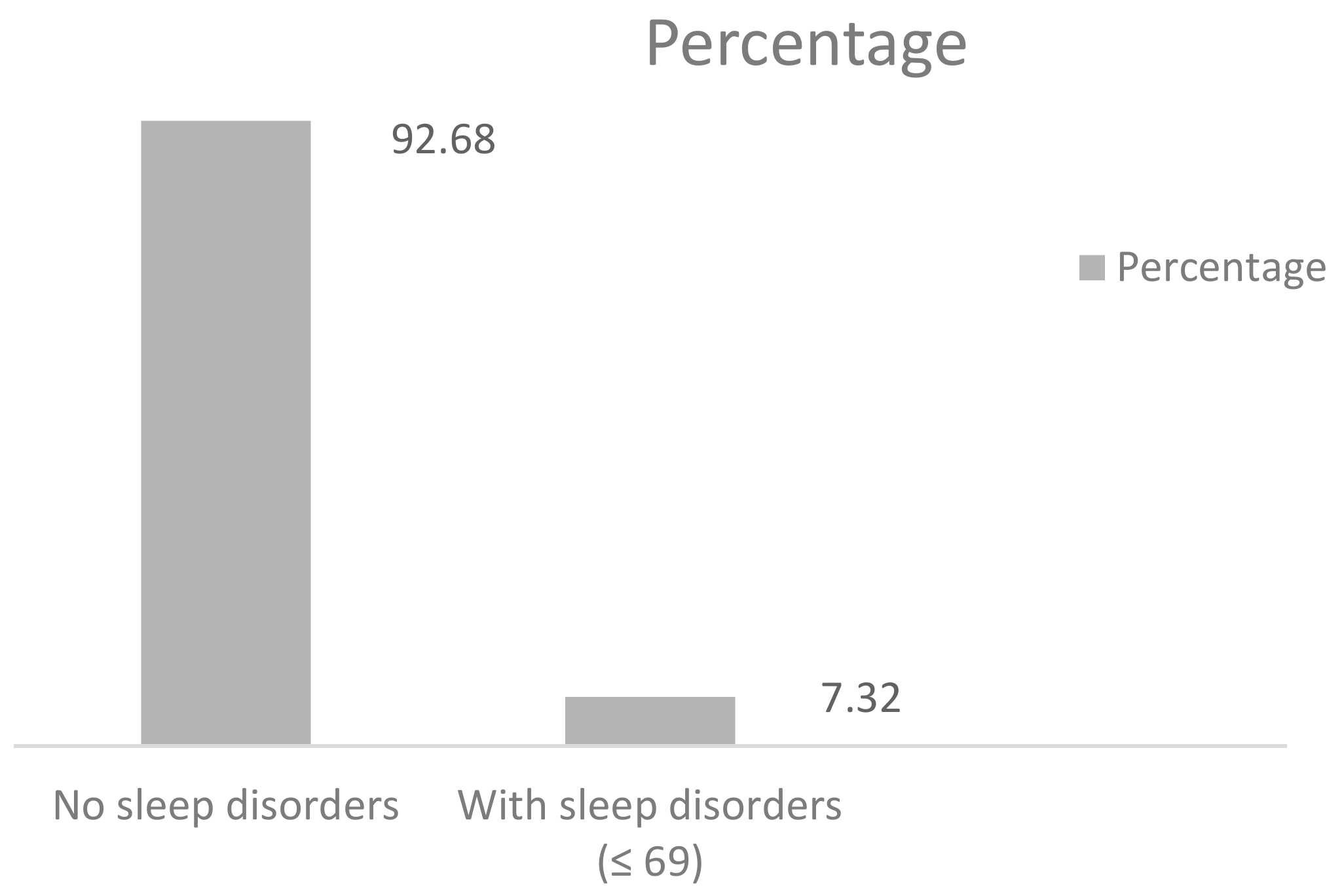

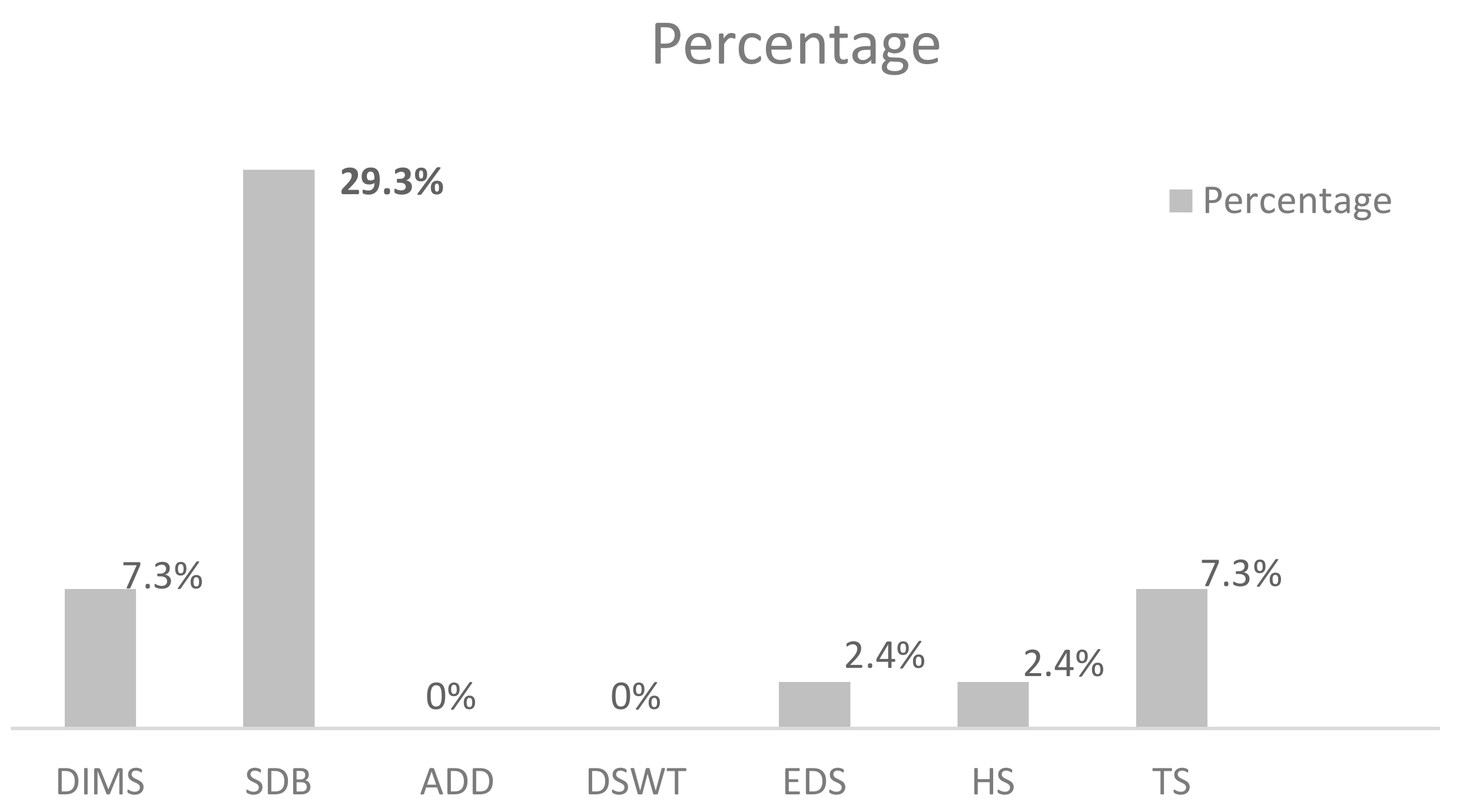

SDSC

4. Discussion

4.1. QRL Outcomes

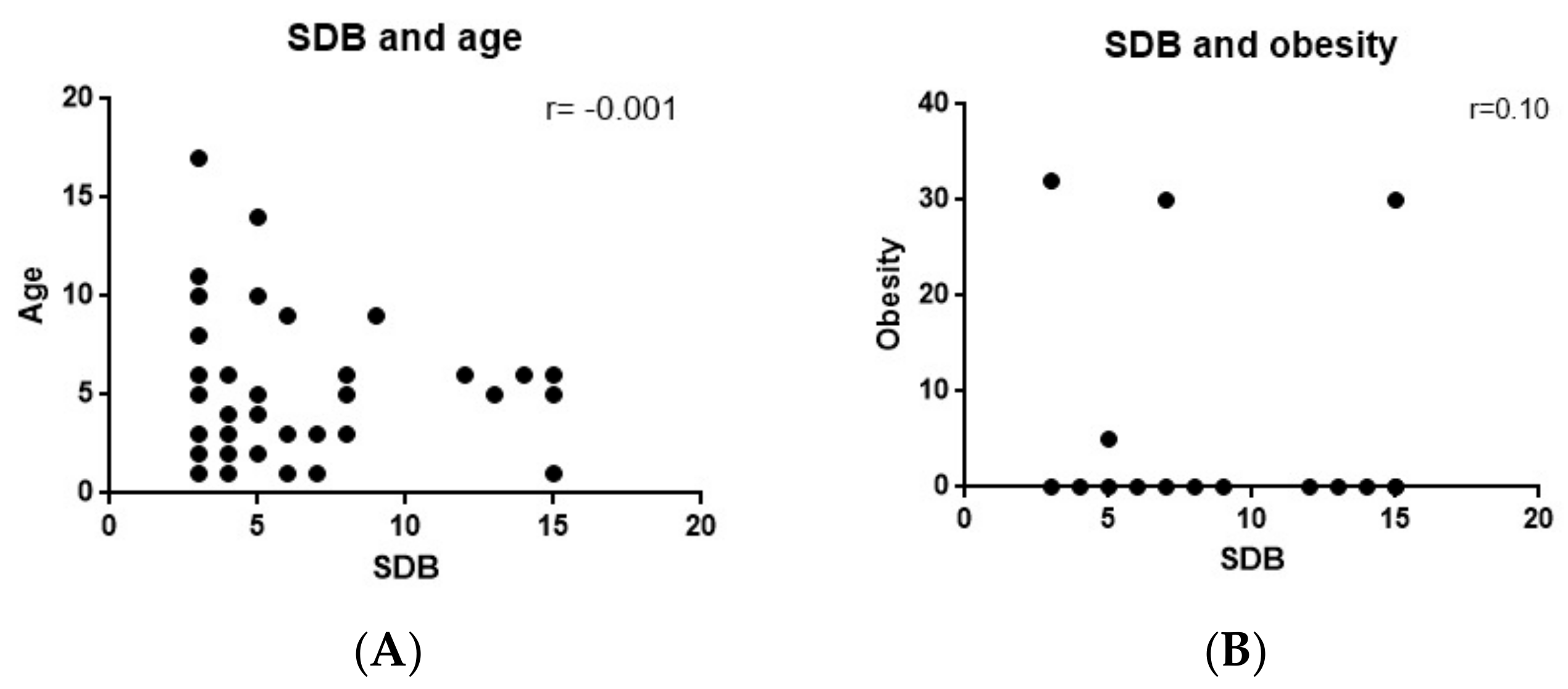

4.2. Sleep Disorders Most Prevalence

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rafii, M.S.; Kleschevnikov, A.M.; Sawa, M.; Mobley, W.C. Down syndrome. Rev. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2019, 167, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, R.S.; Wijayaratne, P.; Nixon, G.M.; Walter, L.M. Sleep and sleep disordered breathing in children with down syndrome: Effects on behaviour, neurocognition and the cardiovascular system. Sleep Med. Rev. 2019, 44, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Espinosa, R.M.; Vila, M.D.M.; García-Galbis, M.G. Evidences from clinical trials in Down syndrome: Diet, exercise and body composition. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stores, R.J. Sleep problems in adults with Down syndrome and their family carers. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2019, 32, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esbensen, A.J.; Schworer, E.K.; Hoffman, E.K.; Wiley, S. Child sleep linked to child and family functioning in children with Down syndrome. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chawla, J.K.; Howard, A.; Burgess, S.; Heussler, H. Sleep problems in Australian children with Down syndrome: The need for greater awareness. Sleep Med. 2021, 78, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lausnay, M.; Verhulst, S.; Van Hoorenbeeck, K.; Boudewyns, A. Obstructive sleep disorders in Down syndrom’s children with and without lower airway anomalies. Children 2021, 8, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.-F.; Lee, C.-H.; Hsueh, W.-Y.; Lin, M.-T.; Kang, K.-T. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in children with Down syndrome: A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2018, 14, 867–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, J.K.; Bernard, A.; Heussler, H.; Burgess, S. Sleep, function, behaviour and cognition in a cohort of children with Down syndrome. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriwardhana, L.S.; Nixon, G.M.; Davey, M.J.; Mann, D.L.; Landry, S.A.; Edwards, B.A.; Horne, R.S.C. Children with down syndrome and sleep disordered breathing display impairments in ventilatory control. Sleep Med. 2021, 77, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonza, A.; Sá-Caputo, D.C.; Sartório, A.; Seixas, S.T.A.; Sanudo, B.; Süßenbach, J.; Provenza, M.M.; Xavier, V.L.; Taiar, R.; Bernardo-Filho, M. COVID-19 Lockdown and the Behavior Change on Physical Exercise, Pain and Psychological Well-Being: An International Multicentric Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trabelsi, K.; Ammar, A.; Masmoudi, L.; Boukhris, O.; Chtourou, H.; Bouaziz, B.; Brach, M.; Bentlage, E.; How, D.; Ahmed, M.; et al. Sleep Quality and Physical Activity as Predictors of Mental Wellbeing Variance in Older Adults during COVID-19 Lockdown: ECLB COVID-19 International Online Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonza, A.; de Sá-Caputo, D.C.; Bachur, J.A.; de Araújo, M.G.R.; Trippo, K.V.; da Gama, D.R.N.; Borges, D.L.; Mendonça, V.A.; Bernardo-Filho, M. Brazil before and during COVID-19 pandemic: Impact on the practice and habits of physical exercise. Acta Biomed. 2020, 92, e2021027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Aymes, G.; Valadez, M.D.; Rodríguez-Naveiras, E.; Castellanos-Simons, D.; Aguirre, T.; Borges, B. A Mixed Methods Research Study of Parental Perception of Physical Activity and Quality of Life of Children Under Home Lock Down in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 649481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento-Ferreira, M.V.; Rosa, A.C.A.; Azevedo, J.C.; Santos, A.R.A.; Araujo-Moura, K.; Ferreira, K.A. Psychometric Properties of the Online International Physical Activity Questionnaire in College Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varkey, I.M.; Ghule, K.D.; Mathew, R.; Desai, J.; Gomes, S.; Mudaliar, A.; Bhori, M.; Tungare, K.; Gharat, A. Assessment of attitudes and practices regarding oral healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic among the parents of children aged 4–7 years. Dent. Med. Probl. 2022, 59, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachón-Zagalaz, J.; Zagalaz-Sánchez, M.L.; Arufe-Giráldez, V.; Sanmiguel-Rodríguez, A.; González-Valero, G. Physical Activity and Daily Routine among Children Aged 0-12 during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabelo, S.M.F.M.; Brandão, M.G.S.A.; Araújo, M.F.M.; Freitas, R.W.J.F.; Vasconcelos, E.C.A.; Veras, V.S. Association between sleep disorders on children, sociodemographic factors and the sleep of caregivers. Enfermería Actual. Costa Rica 2021, 41, 47075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, D.; Lombardo, A.; Skotko, B.; Davidson, E.J. Parental perceptions of sleep disturbances and sleep-disordered breathing in children with Down syndrome. Clin. Pediatr. 2011, 50, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, P.D.P. Validação do Questionário do Sono Infantil de Reimão Lefèvre (QRL). Tese de Doutorado, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bruni, O.; Ottaviano, S.; Guidetti, V.; Romoli, M.; Innocenzi, M. The Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC) Construction and validation of an instrument to evaluate sleep disturbances in childhood and adolescence. J. Sleep Res. 1996, 5, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalheiro, M.G.; Corrêa, C.C.; Maximino, L.P.; Weber, S.A.T. Sleep quality in children: Questionnaires available in Brazil. Sleep Sci. 2017, 10, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miot, H.A. Tamanho da amostra em estudos clínicos e experimentais. J. Vasc. Bras. 2011, 10, 275–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.K.; Jung, E.; Van Riper, M. Sleep problems in Korean children with Down syndrome and parental quality of life. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2019, 63, 1346–1358. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007, 147, W163–W194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattos-Bernardo, R.; Sá-Caputo, D.C.; Bernardo-Filho, M.; Paineiras-Domingos, L.L. Autism spectrum disorder and sleep problems: A critical review of literature. Int. J. Med. All Body Health Res. 2021, 1, 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Billings, M.E.; Hale, L.; Johnson, D.A. Physical and social environment relationship with sleep health and disorders. Chest 2020, 157, 1304–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Section on Pediatric Pulmonology, Subcommittee on Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical practice guideline: Diagnosis and management of childhood obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Pediatrics 2002, 109, 704–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, J.K.; Cooke, E.; Miguel, M.C.; Burgess, S.; Staton, S. Parents experiences of having a child with Down syndrome and sleep difficulties. Behav. Sleep Med. 2022, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fucà, E.; Costanzo, F.; Ursumando, L.; Celestini, L.; Scoppola, V. Sleep and behavioral problems in preschool-age children with Down syndrome. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 943516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gios, T.S.; Mecca, T.P.; Kataoka, L.E.; Rezende, T.C.B.; Lowenthal, R. Sleep Problems Before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder, Down Syndrome, and Typical Development. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2022, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, S.S.; Kieckhefer, G.M.; Bjornson, K.F.; Herting, J.R. Relationship between sleep disturbance and functional outcomes in daily life habits of children with Down syndrome. Sleep 2015, 38, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skotko, B.G.; Garza Flores, A.; Elsharkawi, I.; Patsiogiannis, V.; McDonough, M.E.; Verda, D.; Muselli, M.; Hornero, R.; Gozal, D.; Macklin, E.A. Validation of a predictive model for obstructive sleep apnea in people with Down syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2023, 191, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, W.; Sarber, K.M.; Howard, J.J.M.; Huang, G.; Hossain, M.M.; Heubi, C.H.; Lu, X.; Simakajornboon, N. Children with Down syndrome and mild OSA: Treatment with medication versus observation. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2020, 16, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, C.M.; Evans, H.J.; Elphick, H.; Farquhar, M.; Pickering, R.M. Prevalence and predictors of obstructive sleep apnoea in young children with Down syndrome. Sleep Med. 2016, 27–28, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maris, M.; Verhulst, S.; Wojciechowski, M.; Van de Heyning, P.; Boudewyns, A. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in children with Down syndrome. Sleep 2016, 39, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stores, S.; Stores, R. Sleep disorders and their clinical significance in children with Down syndrome. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2013, 55, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Nunes, L.; Costa-Borges, P.P.; Paineiras-Domingos, L.L.; Bachur, J.A.; Coelho-Oliveira, A.C.; Sá-Caputo, D.C.; Bernardo-Filho, M. Effects of the whole-body vibration exercise on sleep disorders, body temperature, body composition, tone, and clinical parameters in a child with Down syndrome who underwent total atrioventricular septal defect surgery: A case-report. Children 2023, 10, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gender | Girls (18) 43.90%, age range 1–14 years Boys (23) 56.09%, age range 1–17 years |

| Age (years) | 1–3 (17) 41.46% |

| 4–6 (16) 39.02% | |

| 7–9 (3) 7.31% | |

| 10–12 (3) 7.31% | |

| 14–17(2) 4.87% | |

| Relation of respondent to child or adolescent | Mother (40) 97.56% Father (1) 2.43% |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30) | (3) 7.31% |

| Daytime sleepiness | (23) 56.09% |

| OSA diagnostic | Yes (9) 21.95% Unaware of the diagnosis (12) 29.26% |

| Sleep during the day? | Yes | No | ||||

| (23) 56% | (18) 44% | |||||

| How many hours does the child sleep during the day? | 40 min | 1 h up to 1 h and 40 min | 2 h or 2 h and 30 min | 3 h | ||

| (1) 2.44% | (10) 4.1% | (9) 21.95% | (1) 2.44% | |||

| How often does the child get up during the night? | does not wake up during the night | wakes up once during the night | wakes up twice during the night | wakes up three times a night | wakes up five times during the night | wakes up more than five times during the night |

| (11) 26.82% | (15) 36.58% | (8) 19.51% | (3) 7.31% | (1) 2.44% | (1) 2.44% | |

| Total hours of sleep during the night? | 6 h and 30 min | 8 h/ 8 h and 30 min | 9 h/ 9 h and 30 min | 10 h/ 10 h and 30 min | 11 h | 12 h |

| (1) 2.44% | (5) 12.19% | (4) 9.75% | (17) 41.46% | (7) 17.07% | (4) 9.75% | |

| How long does it take the child to fall asleep? | 5 min or less | between 5 and 15 min | between 15 and 30 min | more than 30 min | ||

| (4) 9.75% | (12) 29.26% | (15) 36.58% | (10) 24.39% | |||

| When waking up during the night, how long does it take for the child to fall asleep again? | does not wake up during the night | 5 min or less to sleep | between 5 and 15 min to sleep | between 15 and 30 min to sleep | more than 30 min to sleep | |

| (7) 17.07% | (17) 41.46% | (7) 17.07% | (5) 12.19% | (5) 12.19% | ||

| What usually arouses the child? | wakes up alone | desire to go to the bathroom | noises | family | pet | |

| (33) 80.48% | (2) 4.87% | (2) 4.87% | (3) 7.31% | (1) 2.43% | ||

| During the day, does the child presents drowsiness that interferes? | does not present | school activities | sports practice | watch television | ||

| (34) 82.92% | (5) 12.19% | (1) 2,43% | (1) 2.43% |

| Everyday | One Time per Week | One Time per Month | Less than 1 Time per Month | Never Happens | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urinates while sleeping at night | (22) 53.65% | (3) 7.31% | (2) 4.87% | (2) 4.87% | (12) 29.26% |

| Urinates while sleeping during the day | (17) 41.46% | (2) 4.87% | (2) 4.87% | (2) 4.87% | (18) 43.90% |

| Talks while sleeping | (1) 2.43% | (10) 24.39% | (2) 4.87% | (5) 12.209% | (23) 56.10% |

| Grinds teeth while sleeping | (3) 7.31% | (8) 19.51% | (3) 7.31% | (2) 4.87% | (25) 60.97% |

| Moves a lot in bed while sleeping | (32) 78.04% | (3) 7.31% | (0) | (0) | (6) 14.63% |

| Screams for no reason while sleeping | (0) | (3) 7.31% | (4) 9.75% | (5) 12.19% | (29) 70.73% |

| Says that they had bad dreams and that they are afraid | (1) 2.43% | (0) | (3) 7.31% | (6) 14.63% | (31) 75.60% |

| Snoring at night | (11) 26.82% | (4) 9.75% | (5) 12.19% | (2) 4.87% | (19) 46.34% |

| Snoring during the day | (3) 7.31% | (1) 2.43% | (5) 12.19% | (2) 4.87% | (30) 73.17% |

| Taps and shakes head with equal movements many times in a row in bed | (2) 4.87% | (3) 7.31% | (4) 9.75% | (1) 2.43% | (31) 75.60% |

| Has difficulty staying awake during morning activities | (0) | (2) 4.87% | (3) 7.31% | (4) 9.75% | (32) 78.04% |

| Has difficulty staying awake during afternoon activities | (2) 4.87% | (3) 7.31% | (2) 4.87% | (4) 9.75% | (30) 73.17% |

| Yes | No | |

|---|---|---|

| Sleeps with pet | 0 | 41 (18 girls, 23 boys) |

| Sleeps with a doll, toy or stuffed animal | 9 (7 girls, 2 boys) | 32 (11 girls, 21 boys) |

| Prefers light on to sleep | 6 (5 girls, 1 boy) | 35 (13 girls, 22 boys) |

| Only sleeps if the bedroom light is on | 4 (2 girls, 2 boys) | 37 (16 girls, 21 boys) |

| If they did not have to wake up, would sleep longer every day | 9 (6 girls, 3 boys) | 32 (12 girls, 20 boys) |

| Have been to the doctor for having problems sleeping Sleeps at school Why does the child sleep at school? | 5 (2 girls, 3 boys) 3 (3 boys) was not informed | 36 (16 girls, 20 boys) 38 (18 girls, 20 boys) --------------------------- |

| Participant Code | DIMS | SDB | ADD | DSWT | EDS | HS | TS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P01 | 9 | 3 | 7 | 12 | 7 | 3 | 41 |

| P02 | 20 | 4 | 4 | 16 | 7 | 3 | 54 |

| P03 | 19 | 6 | 9 | 10 | 23 | 6 | 73 |

| P04 | 14 | 6 | 4 | 11 | 8 | 6 | 49 |

| P05 | 21 | 15 | 7 | 19 | 5 | 4 | 71 |

| P06 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 32 |

| P07 | 20 | 7 | 3 | 16 | 7 | 6 | 59 |

| P08 | 17 | 15 | 5 | 11 | 10 | 5 | 63 |

| P09 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 29 |

| P10 | 16 | 8 | 7 | 17 | 6 | 6 | 60 |

| P11 | 14 | 6 | 7 | 16 | 9 | 10 | 2 |

| P12 | 18 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 41 |

| P13 | 9 | 3 | 5 | 12 | 10 | 2 | 41 |

| P14 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 31 |

| P15 | 11 | 4 | 4 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 36 |

| P16 | 18 | 3 | 4 | 9 | 8 | 4 | 46 |

| P17 | 16 | 14 | 6 | 14 | 6 | 6 | 62 |

| P18 | 11 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 6 | 2 | 35 |

| P19 | 27 | 8 | 6 | 9 | 6 | 2 | 58 |

| P20 | 12 | 4 | 5 | 13 | 7 | 4 | 45 |

| P21 | 11 | 5 | 5 | 13 | 5 | 5 | 44 |

| P22 | 32 | 3 | 4 | 10 | 17 | 2 | 68 |

| P23 | 20 | 7 | 6 | 21 | 9 | 2 | 65 |

| P24 | 23 | 8 | 7 | 11 | 7 | 5 | 61 |

| P25 | 14 | 4 | 5 | 11 | 5 | 4 | 43 |

| P26 | 13 | 3 | 6 | 13 | 5 | 2 | 42 |

| P27 | 9 | 13 | 6 | 16 | 9 | 3 | 56 |

| P28 | 8 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 28 |

| P29 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 30 |

| P30 | 17 | 12 | 3 | 14 | 10 | 2 | 58 |

| P31 | 19 | 5 | 7 | 17 | 6 | 2 | 56 |

| P32 | 11 | 4 | 4 | 10 | 6 | 4 | 39 |

| P33 | 8 | 9 | 4 | 12 | 7 | 2 | 42 |

| P34 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 29 |

| P35 | 9 | 5 | 3 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 35 |

| P36 | 11 | 5 | 4 | 10 | 6 | 2 | 38 |

| P37 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 15 | 5 | 2 | 41 |

| P38 | 16 | 5 | 5 | 13 | 6 | 5 | 50 |

| P39 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 26 |

| P40 | 8 | 3 | 7 | 15 | 5 | 2 | 40 |

| P41 | 21 | 15 | 7 | 11 | 14 | 2 | 70 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Torres-Nunes, L.; da Costa-Borges, P.P.; Paineiras-Domingos, L.L.; Bachur, J.A.; de Sá-Caputo, D.d.C.; Bernardo-Filho, M. Sleep Disorder Prevalence among Brazilian Children and Adolescents with Down Syndrome: An Observational Study. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4014. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13064014

Torres-Nunes L, da Costa-Borges PP, Paineiras-Domingos LL, Bachur JA, de Sá-Caputo DdC, Bernardo-Filho M. Sleep Disorder Prevalence among Brazilian Children and Adolescents with Down Syndrome: An Observational Study. Applied Sciences. 2023; 13(6):4014. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13064014

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorres-Nunes, Luiza, Patrícia Prado da Costa-Borges, Laisa Liane Paineiras-Domingos, José Alexandre Bachur, Danúbia da Cunha de Sá-Caputo, and Mario Bernardo-Filho. 2023. "Sleep Disorder Prevalence among Brazilian Children and Adolescents with Down Syndrome: An Observational Study" Applied Sciences 13, no. 6: 4014. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13064014

APA StyleTorres-Nunes, L., da Costa-Borges, P. P., Paineiras-Domingos, L. L., Bachur, J. A., de Sá-Caputo, D. d. C., & Bernardo-Filho, M. (2023). Sleep Disorder Prevalence among Brazilian Children and Adolescents with Down Syndrome: An Observational Study. Applied Sciences, 13(6), 4014. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13064014