1. Introduction

With the technological developments made since the Fourth Industrial Revolution, devices such as smartphones and personal computers (PCs) have rapidly grown in number [

1]. Kiosks, which are unmanned terminals that allow users to obtain information through information services or task automation without any human assistance [

1,

2,

3], are natural and intuitive information systems that have become an important element of the information age. Each kiosk supports multimedia (audio, video, photos, and animation) functionalities, allowing users to interact with them in different ways [

4]. Public kiosk systems are used for various purposes, including taking pictures, connecting devices to the Internet, purchasing tickets, obtaining financial and administrative services, and learning directions. The service industry has been surging with the introduction of kiosks, and developments in touch screen technology have enabled their easy accessibility in daily life [

5]. These devices have become common in various public places such as restaurants, subways, museums, shopping malls, hospitals, movie theaters, libraries, and airports, and they are gradually growing in number [

1,

4,

6,

7,

8].

Recently, artificial intelligence (AI) concierges with technologies such as facial and voice recognition and thermal imaging cameras have been introduced to solve the accessibility and usability problems that elderly persons face when using kiosks. Such concierges welcome and guide customers and deliver basic information regarding topics such as exchange rates and the weather. AI concierges in the financial sector use a large screen attached to the kiosk and guide users by a simulated natural conversation. Regarding the advantages on the provider side, kiosks can continually provide a high quality of service and reduce labor costs as they are operable 24 h a day; on the consumer side, customers can benefit from the services quickly and not have to wait in line for a long time [

9]. However, even such generally used kiosks still pose problems regarding accessibility and usability for people with disabilities and for the elderly [

10,

11]. When using a kiosk, not only are difficulties experienced in operating procedures such as menu selection, but also in accessing the kiosk space itself. If such accessibility issues are not considered when designing and using a kiosk, there will be severe restrictions on the daily use of kiosks by such people [

10,

12].

Usability is generally defined as an individual’s ability to perform a task [

13,

14,

15]. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 9241-11 defines usability as “the extent to which a specific user can use a product to achieve a specific goal with effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction in a specific use environment” [

16]. Usability is an important element of the existing user experience (UX) and includes items such as simplicity, directness, efficiency, informativeness, flexibility, learnability, and user support, which measures how easily and conveniently a product/service can be used [

17,

18]. According to the ISO, accessibility is defined as the ease of use of a product, service, environment, or facility, regardless of individuals’ capabilities [

19]. Products/systems with accessible designs are ones that users with disabilities can use [

20]; such a design is referred to as inclusive design [

21] and universal design [

22]. Although accessibility and usability are different concepts, they are sometimes used interchangeably without clear differences in existing studies [

23]. Their ISO definitions make them seem similar, and they seem to only differ with respect to how users with disabilities perceive them. Accessibility mainly refers to the capability of an individual to access a specific device, and its definition has been covered in many legislations [

5,

24,

25]. Regarding kiosk devices, there are various existing legislations, and new ones are also being enacted [

5]. In the United States, kiosk-related legislations exist in Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act, US Air Carrier Access Act, Americans with Disabilities Act Standards for Accessible Design, and kiosk-related legislation has also been recently added to the European Accessibility Act. In Korea, the Guidelines for Public Access Terminal Accessibility Standard Document exists; this documentation was included in the Digital Divide Reduction Act in 2021. In contrast, usability has been considered in the development of design interface guidelines along with UX concepts [

26]. Despite usability being already somewhat established in the field of technology, some of its characteristics have been vaguely defined; it has sometimes been used interchangeably with terms such as “dummy proofing” and “user-friendliness”, which reduces the importance of its meaning in interaction design and negatively affects how user performance is viewed in terms of productivity. Furthermore, visual design, which is an essential element of usability that is commonly misunderstood with visual appeal, is not the only part of interaction design [

27]. There have been studies on kiosk usability that have included evaluations of the usability of kiosk systems specialized for wayfinding [

4,

6] as well as studies on the user interface (UI) design guidelines of kiosks [

28,

29]. However, there is insufficient research on the design of new kiosk UIs with a focus on user needs [

30].

The purpose of this study is to systematically analyze the concepts of accessibility and usability with a focus on kiosk devices. Even if a specific product satisfies the required accessibility requirements, it does not mean that users with disabilities have a satisfactory UX when using it [

24]. Accessibility needs to be considered in the development stage of the product/device and during the enactment of the relevant laws; using certain measures, the compliance of a specific/product service with laws can be confirmed [

10]. Regarding usability, its inclusion in legislation needs to be carefully considered because there are many changes with the related laws conflicting with the freedom and creativity of a company’s product/device design. Particularly regarding legal regulations, many cases trail behind technological developments [

10]; therefore, when applying or creating new technology, it is necessary to focus on accessibility separately from usability. As mentioned earlier, there are many studies that individually define accessibility and usability but few that systematically compare and analyze them. Furthermore, the studies that have compared and analyzed these concepts mainly involved websites and smartphones. In addition to kiosks being used for obtaining information, there are other situations wherein they are used, including in facilitating a payment service using a credit card/smartphone or a discount service on a welfare card for people with disabilities. Therefore, it is necessary to redefine the accessibility and usability of kiosks while considering these circumstances. To this end, the concepts and characteristics of accessibility and usability were comprehensively investigated through a literature review, and focus group interviews (FGIs) were conducted, targeting individuals with visual, hearing, or physical impairments. Through these interviews, a clear concept regarding the accessibility and usability of a kiosk could be defined. Based on our assessments, we have presented a diagram defining the concepts of accessibility and usability, which is expected to be useful when designing kiosk features while considering accessibility and usability in the future or when creating legal and practical design guidelines for kiosks.

4. Results

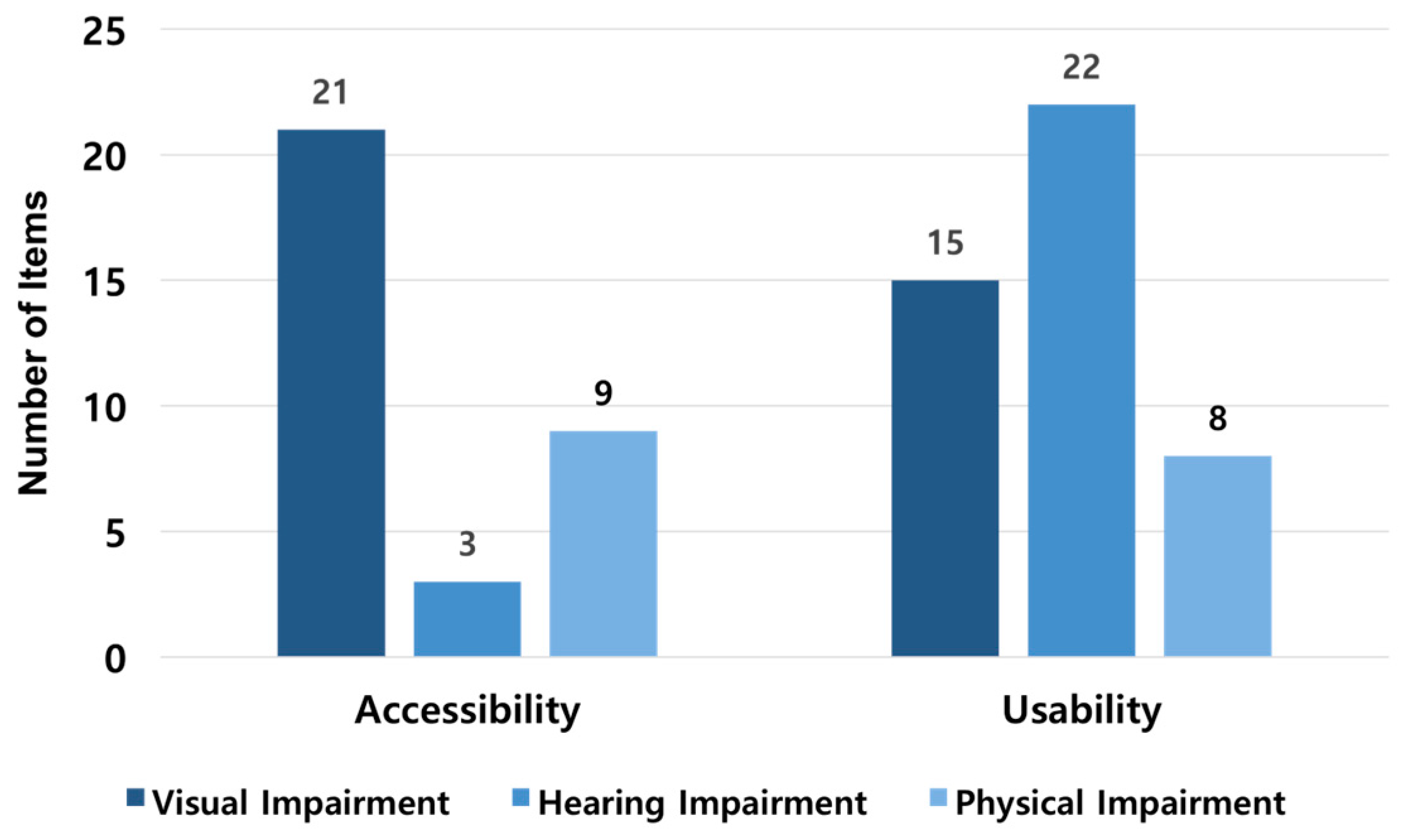

Overall, 94 usability opinions were derived through FGIs; these opinions comprised 28, 54, and 12 opinions from individuals with visual, hearing, and physical impairments, respectively. Similar or overlapping opinions from participants with each type of disability were grouped, resulting in 45 items being derived. These items included 15, 22, and 8 types of opinions from participants with visual, hearing, and physical impairments, respectively.

Regarding accessibility, 180 opinions were obtained; these comprised 89, 36, and 55 opinions from individuals with visual, hearing, and physical impairments, respectively. Similar or overlapping opinions from participants with each type of disability were grouped, resulting in 33 items being derived. These items included 21, 3, and 9 types of opinions from participants with visual, hearing, and physical impairments, respectively.

When calculating the number of opinions, duplicate opinions were also obtained. Among the derived opinions, those judged to be ambiguous or inconsistent with the concept of accessibility and usability were excluded. For example, the opinion “BF should be considered first” was excluded because it was considered too comprehensive. Overall, six opinions, including duplicates, were excluded.

4.1. Number of Accessibility and Usability Items by Type of Impairment

All of the opinions collected through the FGIs were grouped according to their similarities, organized, and classified overall into 78 items; we classified 33 and 45 items as related to accessibility and usability, respectively. Overall, the items that were related to visual and physical impairments were derived the most and least, respectively (

Figure 2). Accessibility was derived in the order of visual, physical, and hearing impairments, and usability was derived in the order of hearing, visual, and physical impairments.

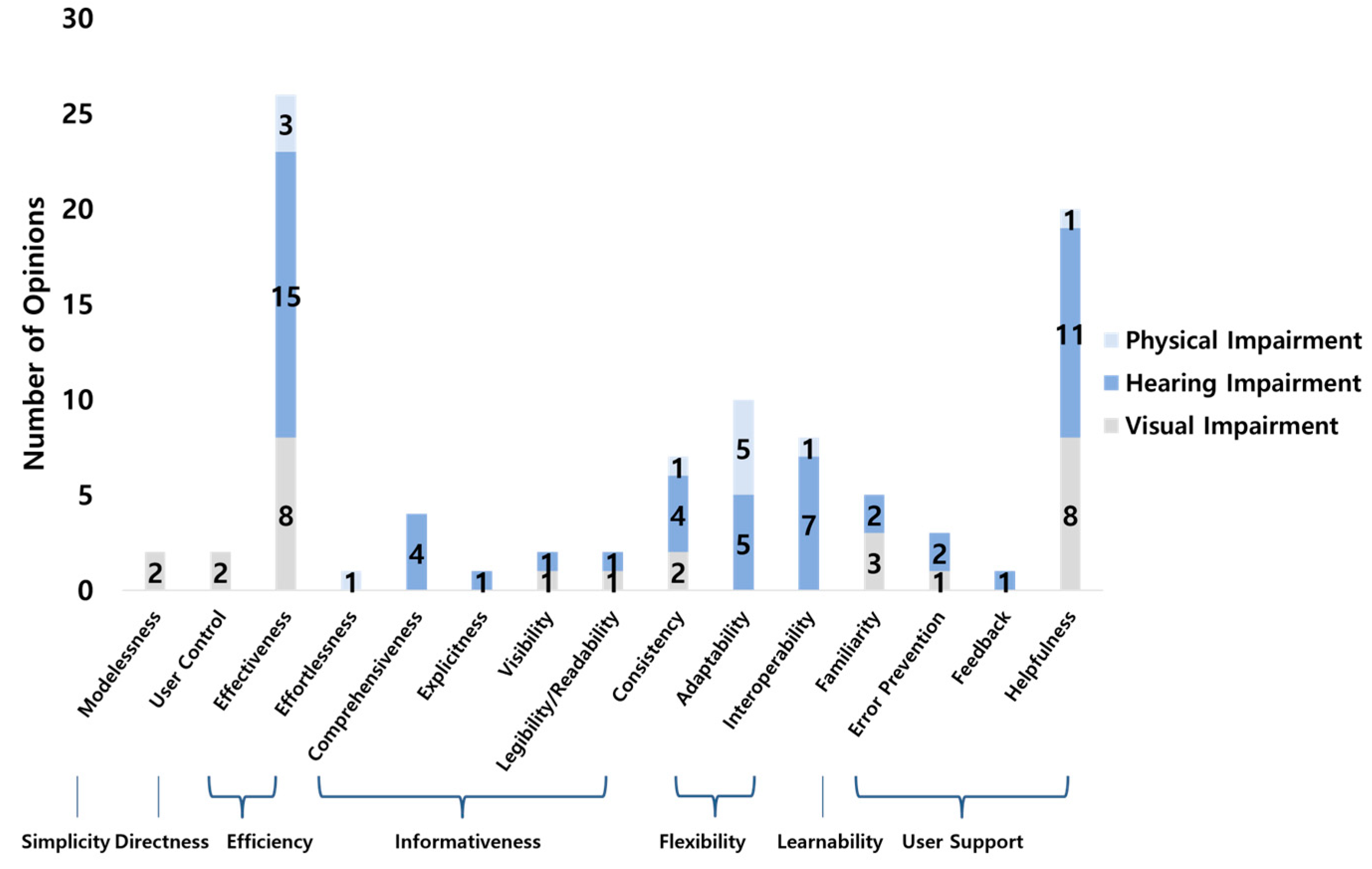

In the subcategories, the opinions related to accessibility were derived in the order of physical accessibility, multimodal information, and user control; those related to usability were derived in the order of effectiveness, helpfulness, and adaptability (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

4.2. Analysis of Accessibility Items by Type of Impairment

Participants with different impairments provided many comments on their experience regarding the accessibility of kiosks: participants with visual impairments provided comments such as “providing voice support”, “including a high-contrast function”, “adjusting kiosk height”, and “maintaining consistency in the design of the card slot” (

Table 3); those with hearing impairments provided opinions such as “including non-vocal feedback” and “providing sign language interpreters when help button is pressed” (

Table 4); and those with physical disabilities provided comments such as “equipping kiosks with wheelchair accessibility”, “adjusting kiosk height”, and “adjusting kiosk UI” (

Table 5).

4.3. Analysis of Usability Items by Impairment Type

Participants with different impairments provided opinions regarding usability when using kiosks. The participants with visual impairments provided many opinions such as “enabling linkage between a smartphone and the kiosk” and “including use of smartphone” (

Table 6); those with hearing impairments provided many opinions such as “enabling linkage between a smartphone and the kiosk”, “including sign language interpretation service”, and “incorporating automated discount for people with disabilities when using the parking lot” (

Table 7); and those with physical impairments provided many opinions such as “Making payment system for parking within an arm’s reach”, “Diversifying card payment methods”, and “Incorporating a tablet-ordering-system to improve convenience in ordering”(

Table 8).

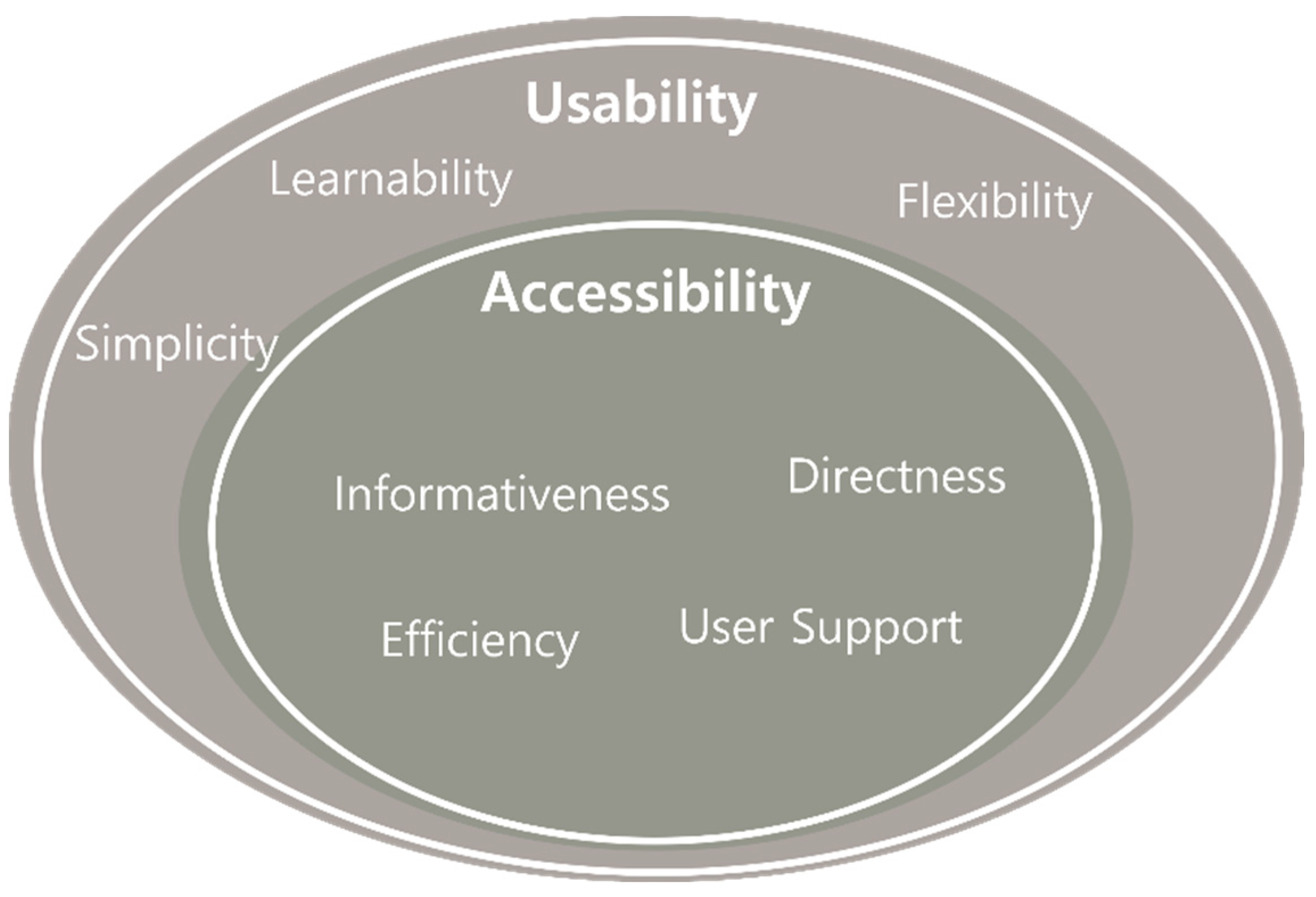

5. Accessibility and Usability Characteristics of Kiosks

This study analyzed the accessibility and usability characteristics of kiosks based on the definitions of accessibility and usability as derived through a literature analysis. Based on the categories in

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8, the concept of accessibility for kiosk devices was divided into the major categories of directness, informativeness, user support, and efficiency, while the concept of usability was divided into the major categories of simplicity, directness, efficiency, informativeness, learnability, user support, and flexibility (

Figure 5). Therefore, when only viewing the major categories analyzed in

Table 1 and

Table 2, accessibility can be seen as a subset of usability, as described in previous studies [

50].

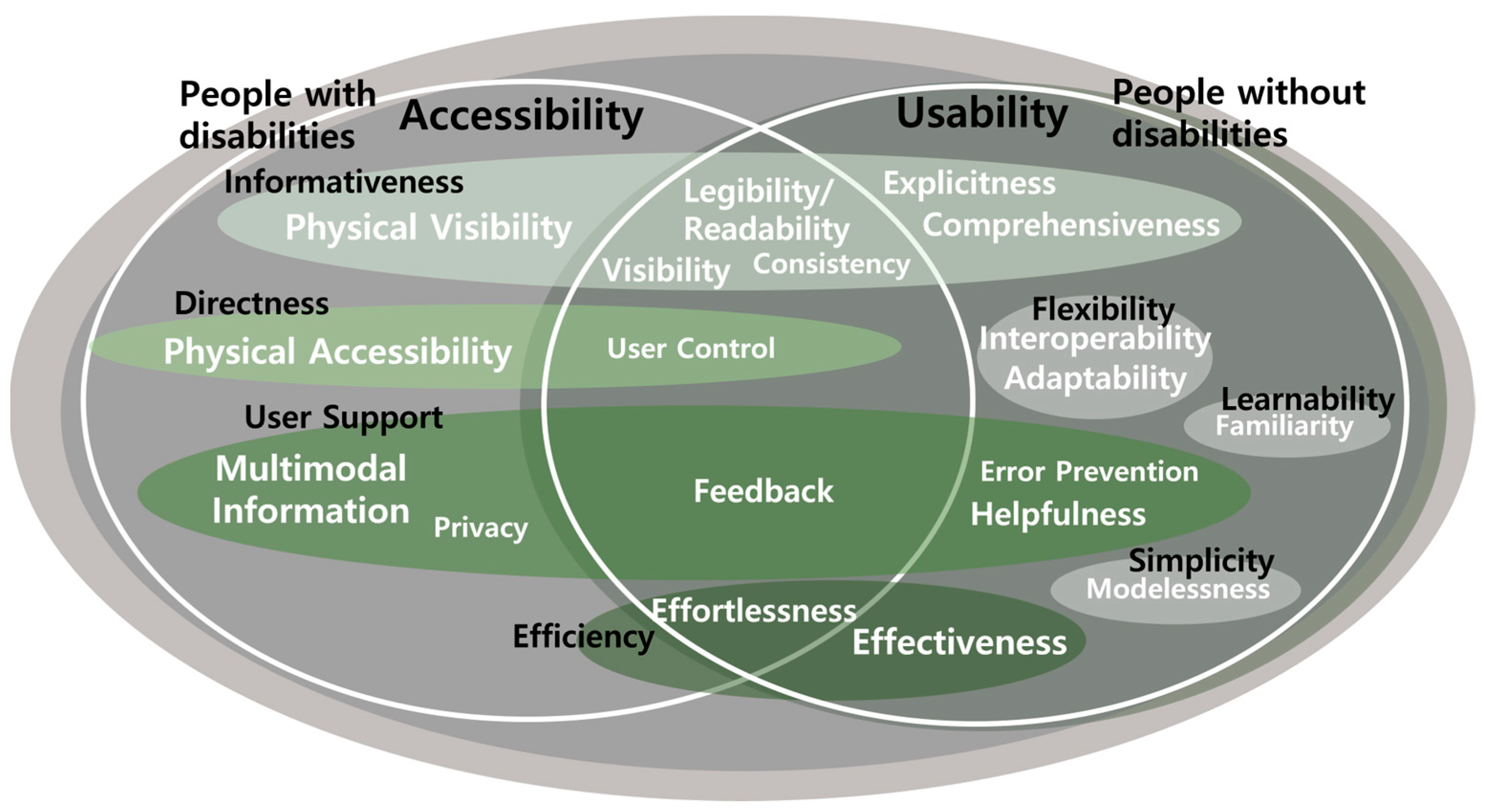

However, expanding each concept to small categories and examining them thoroughly revealed that despite having certain intersections, accessibility and usability were different concepts. Regarding directness within accessibility, opinions related to the physical accessibility of a kiosk (

Table 3 and

Table 5) and the voice expansion function for using its main functions were derived as representative scenarios (

Table 4). In the case of directness within usability, opinions were collected to provide various interface modes for improving the legibility/readability of the text of kiosks (

Table 6). Informativeness, physical visibility, visibility, legibility/readability, and consistency were derived for accessibility; visibility, legibility/readability, consistency, comprehensiveness, and explicitness were derived for usability. Informativeness (within usability) had more concepts related to preferred information types (e.g., vertical arrangement information structure and a preference for text over pictures) and content that required more specific and abundant information than the concept of availability/unavailability of information access from a kiosk. User support within accessibility was derived into privacy, multimodal information, feedback, and forgiveness, while user support within usability was derived into feedback, error prevention, and helpfulness; the groups were very clearly different. Finally, efficiency under accessibility was derived to effortlessness related to solving the difficulty of card insertion, whereas the efficiency under usability mostly involved comments related to effectiveness.

We drew a diagram based on the subcategory results of

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8 related to accessibility and usability (

Figure 6). The major category items common to accessibility and usability were expressed by grouping the smaller category items in a circle, while the smaller category items common to both were organized in areas where accessibility and usability overlapped. For example, informativeness is a primary category common to accessibility and usability, and legibility/readability, visibility, and consistency are the small categories common to them. In the case of flexibility, the primary categories of the items were organized in the usability area because they only existed there. Although accessibility and usability had common denominators in legibility/readability, visibility, consistency, and user control, the analysis of the subcategories confirmed that they were very different concepts. Additionally, many opinions on accessibility involved essential functions, while many on usability involved additional functions and services; psychological factors such as personal preference were also involved.

7. Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to define the concepts of accessibility and usability for kiosks and identify the characteristics of these concepts for people with different types of disabilities. First, the concepts of accessibility and usability were investigated through a literature review. Then, FGIs were conducted to collect comprehensive experiences on the accessibility and usability of kiosks for some participants and organize the characteristics of these concepts accordingly. Based on the collected data, we have presented a diagram that analyzes the relationship between accessibility and usability.

The opinions collected through the FGIs were classified into 78 items, 33 of which were classified as accessibility and 45 of which were classified as usability. The derived items were mapped according to previously organized criteria for accessibility and usability, and the number of opinions for each item was derived. The items for accessibility were derived in the order of visual impairment, physical disability, and hearing impairment, while those for usability were derived in the order of hearing impairment, visual impairment, and physical disability. The concepts of accessibility and usability were defined based on the opinions derived through the FGIs. Accessibility mainly had characteristics related to essential functions, and usability mainly had characteristics related to additional functions. The detailed definitions of accessibility and usability for kiosks in this study are expected to be useful in developing guidelines and laws for using kiosks in the future.